Abstract

There is a growing trend in robotics for implementing behavioural mechanisms based on human psychology, such as the processes associated with thinking. Semantic knowledge has opened new paths in robot navigation, allowing a higher level of abstraction in the representation of information. In contrast with the early years, when navigation relied on geometric navigators that interpreted the environment as a series of accessible areas or later developments that led to the use of graph theory, semantic information has moved robot navigation one step further. This work presents a survey on the concepts, methodologies and techniques that allow including semantic information in robot navigation systems. The techniques involved have to deal with a range of tasks from modelling the environment and building a semantic map, to including methods to learn new concepts and the representation of the knowledge acquired, in many cases through interaction with users. As understanding the environment is essential to achieve high-level navigation, this paper reviews techniques for acquisition of semantic information, paying attention to the two main groups: human-assisted and autonomous techniques. Some state-of-the-art semantic knowledge representations are also studied, including ontologies, cognitive maps and semantic maps. All of this leads to a recent concept, semantic navigation, which integrates the previous topics to generate high-level navigation systems able to deal with real-world complex situations.

1. Introduction

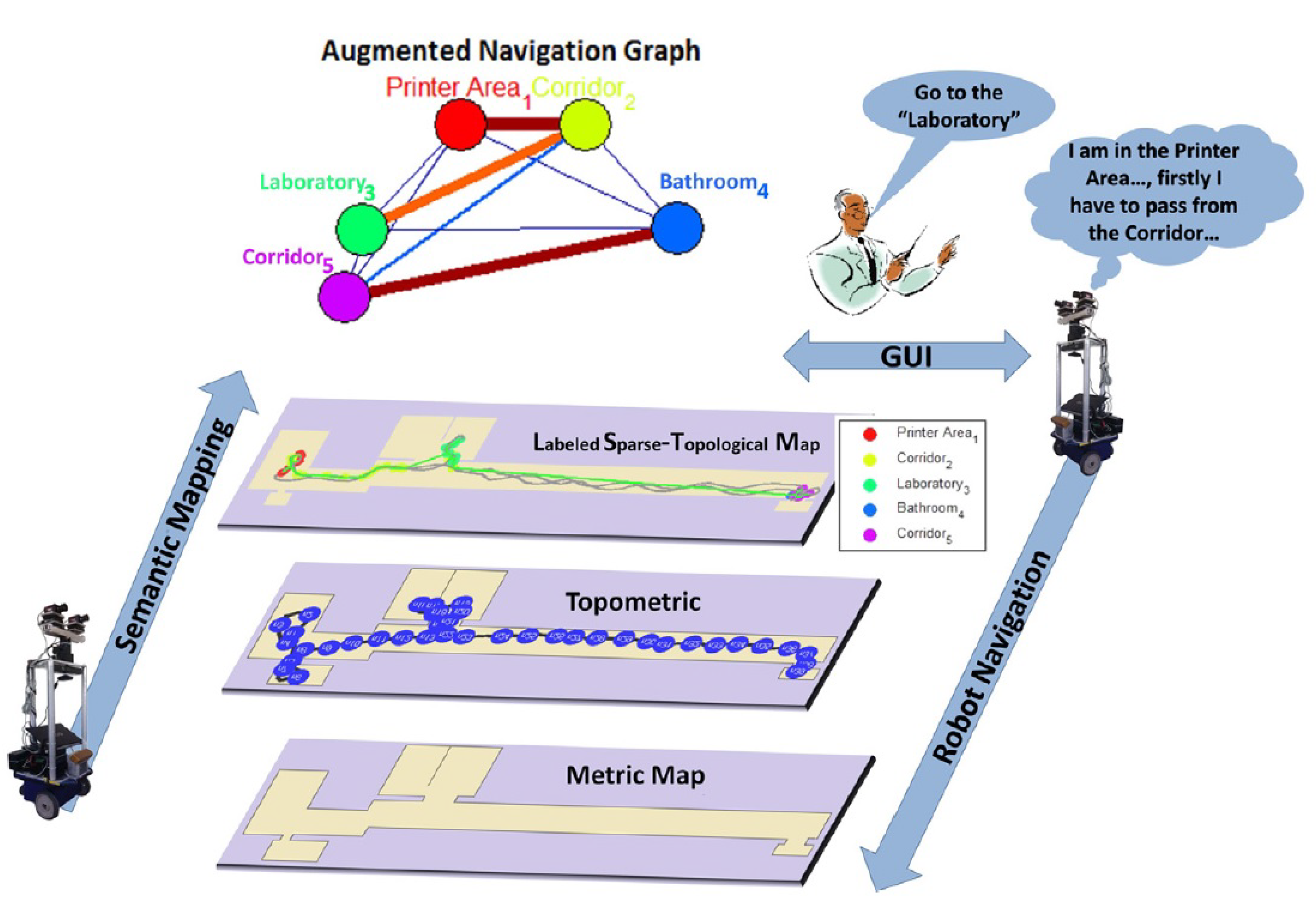

In recent years, there is a growing interest in adding high-level information to several robotics applications to achieve more capable robots, even able to react to unforeseen events. Following this trend, the mobile robotics field is starting to include semantic information to navigation tasks, leading to a new concept: semantic navigation. This type of navigation brings closer the human way of understanding the environment with how the robots understand it, providing the meanings to represent the explored environment in a human-friendly way [1].

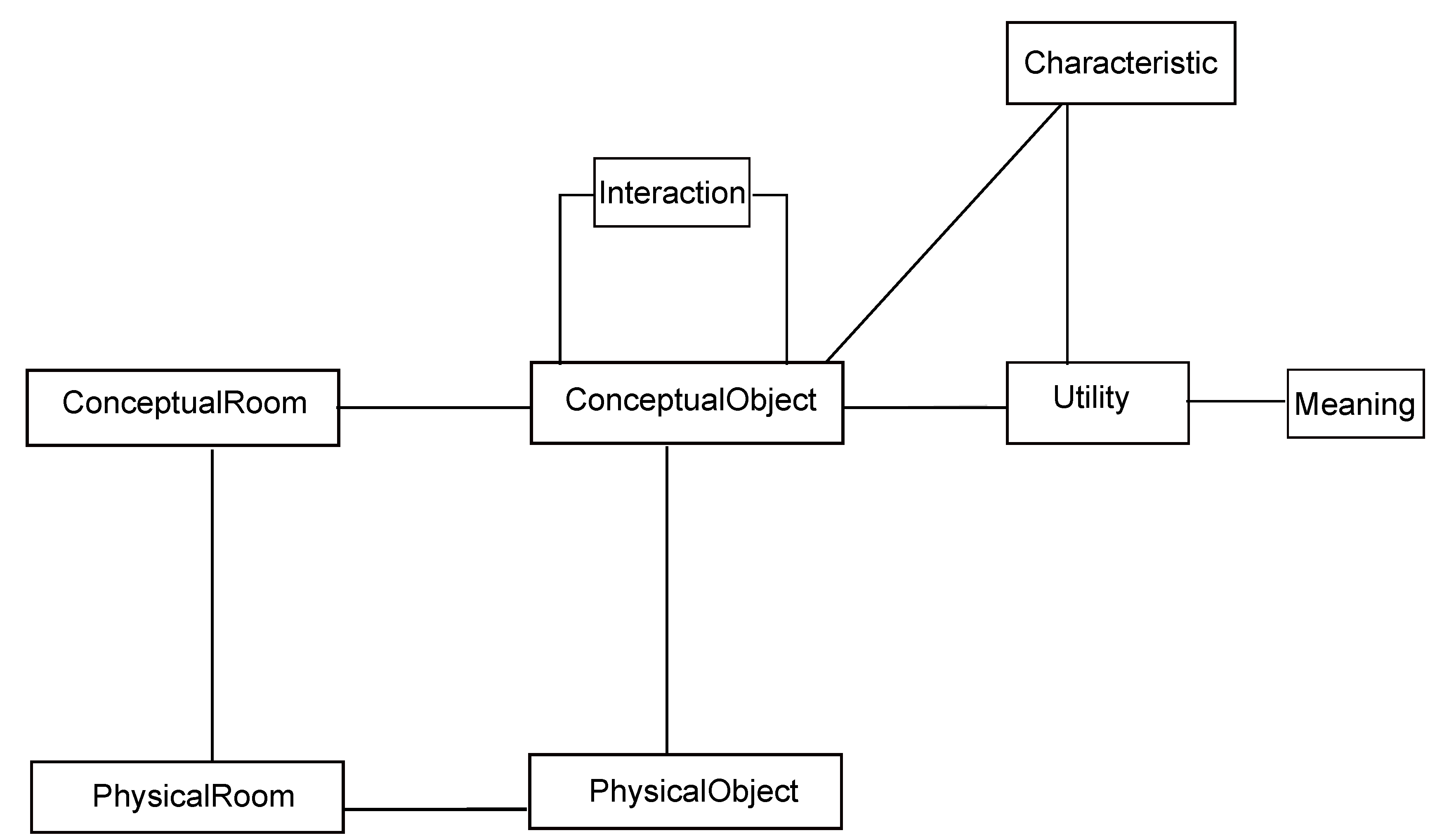

People identify the place where they are both spatially and conceptually. If a person moving through an indoor environment is asked about the trajectory of their displacement, they will not answer in terms of nodes or coordinates. Instead, people tend to provide concepts such as “I was in the living room and I went to the kitchen to drink a glass of water”. In this regard, there are efforts towards including semantic concepts of the environment in robot navigation. This can be achieved by implementing cognitive maps, an approach able to encode information about the relationships between concepts in the environment. Concepts are high-level (abstract) entities that group objects (e.g., chair, table, bed) and places (e.g., bedroom, office, kitchen), utilities (e.g., used for sitting) and the relationships between them. Objects and places detected in the environment are translated into physical entities. These entities can also be related to concepts, such as the utility of an entity. This kind of representation allows robots to build maps that can be understood by humans, thus reducing the gap between geometric interpretation and high-level concepts.

Semantic maps provide a representation of the environment considering elements with high-level of abstraction [2]. These possess different meanings for humans including the relationships with spatial elements used in low-level navigation systems. Semantic navigation requires connecting the high-level attributes with the geometric information of the low-level metric map. This high-level information can be extracted from data coming from a range of sensors, allowing the identification of places or objects. Adding semantic meaning to the elements in the scene and their relations also facilitates human-robot interaction (HRI) since the robot will be able to understand high-level orders associated with human concepts. For instance, Kollar and Roy applied these concepts to understanding natural language interactions when a person requests a robot to find a new object and the robot must look for that object in the environment [3]. Therefore, adding semantic knowledge in mobile robots navigation tasks poses an important advance with respect to traditional navigation techniques that generally use metric [4,5,6], topological [7,8,9], or hybrid maps (a combination of the previous two ones) [10,11].

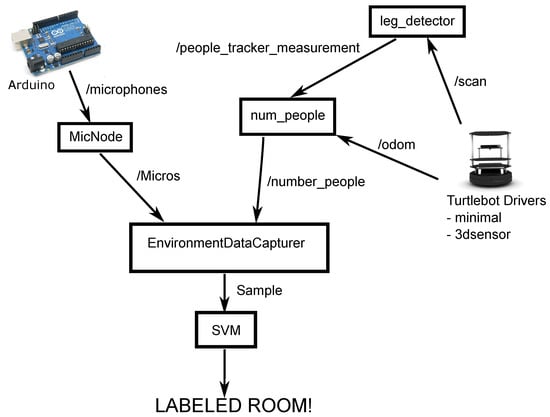

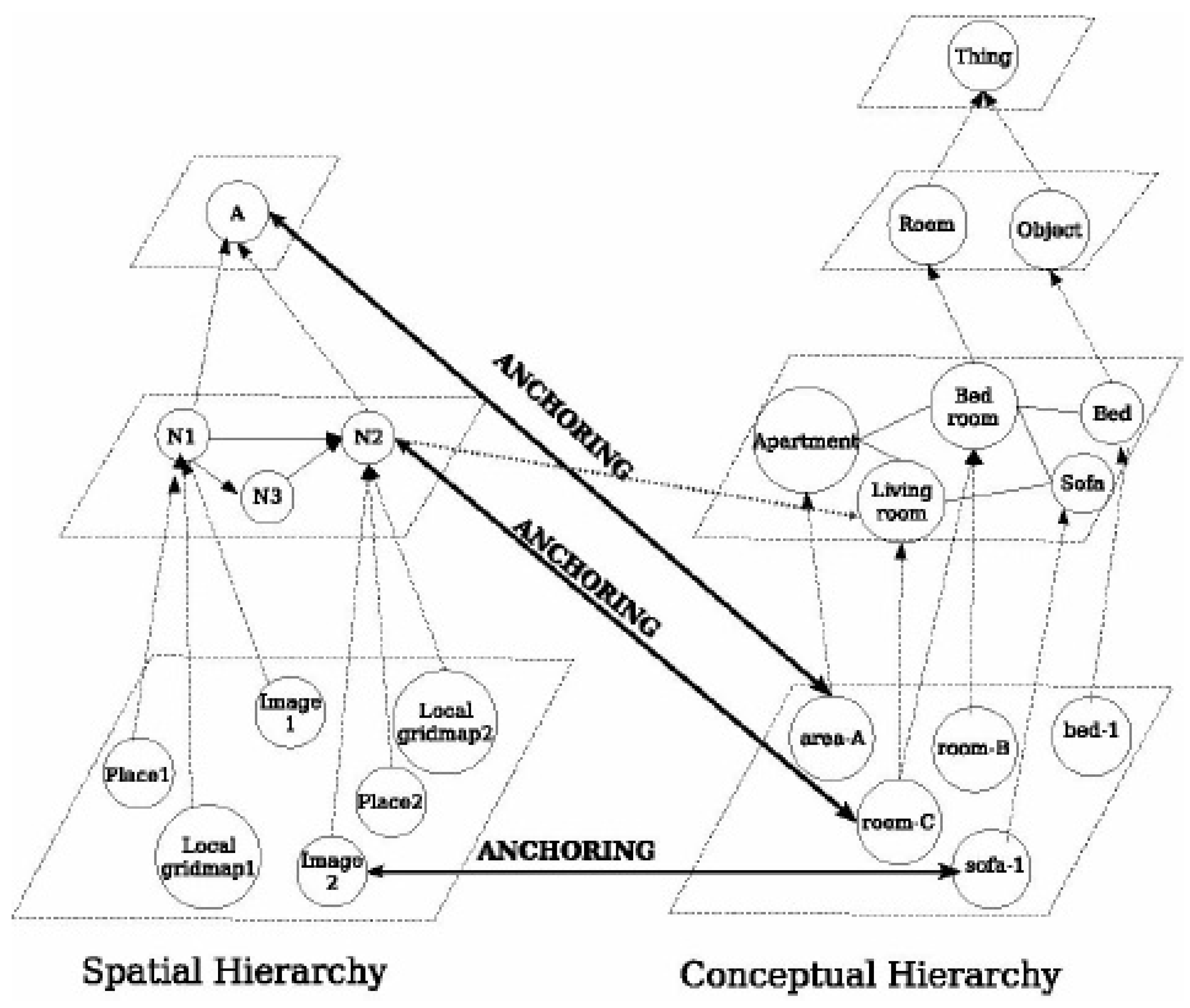

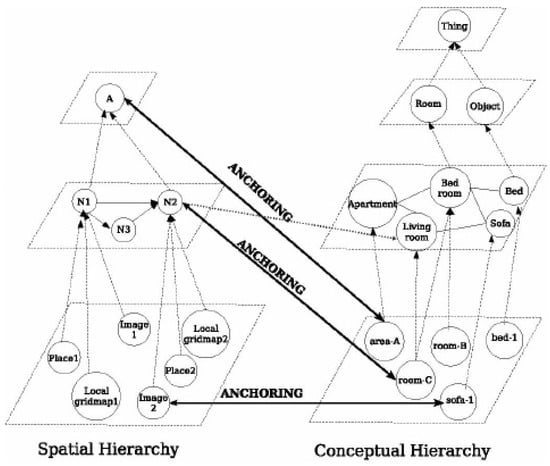

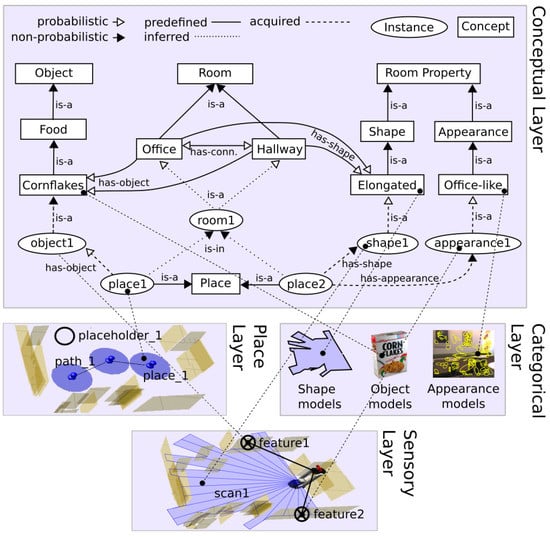

When adding this high-level information to navigation systems, the first issue to address is how to represent knowledge. In this regard, Ontologies are one of the best ways of obtaining high-level representations of knowledge through hierarchies of concepts [12]. Since commonly concepts of entities, such as objects, tend to be separated from physical and real objects in the environment, spatial and conceptual hierarchies arise. Galindo et al., propose to make two categories of hierarchies [13]. The spatial hierarchy contains metric information of the environment, and its nodes represent open areas such as rooms or corridors. The arcs represent the possibility of navigating from one node to another. The conceptual hierarchy models semantic knowledge from environment information. In this approach, all concepts derive from the Thing entity. This is the highest-level concept from which the rest of concepts in this architecture derives. The hierarchy has three levels, with Thing in the first one. On the second level, there are the entities Room and Object, and the next level contains specifications of those concepts (kitchen, bedroom, bed). Figure 1 depicts the content of the three levels in the conceptual hierarchy and how this is related to the spatial one. The spatial hierarchy includes the abstract node that encodes all knowledge at the top level, the environment topology is placed at the middle level and the sensory information, such as images or gridmaps, is located at the bottom level. This knowledge is considered when creating semantic map. These maps are representations of the environments enhanced with information associated with objects, known places, actions that could take place, etc. Also, notice that semantic navigation requires that the robot integrates several skills. In this type of navigation, the communication between the robot and the human user acquires greater relevance since high-level commands issued by the user can be understood directly by the robot. For this reason, a dialogue capability for the human-robot interaction is recommendable. Another skill the robot must have is the ability to detect elements of the environment, allowing the robot to make a classification of rooms.

Figure 1.

The spatial and semantic information hierarchies [13].

Summarising, semantic navigation is a paradigm that integrates high-level concepts from the environment (objects or places) in a navigation stack. Relationships between concepts are also exploited such as the most likely places that contain certain kinds of objects, or the actions that can be performed with determined objects. With the knowledge generated from these concepts and relationships, a robot can perform inferences about the environment that can be integrated into navigation tasks, allowing a better localization or planning to decide where not detected objects could be located. In this regard, semantic navigation brings significant benefits to mobile robot navigation.

- Human-friendly models. The robot models the environment with the same concepts that humans understand.

- Autonomy. The robot is able to draw its own conclusions about the place to which it has to go.

- Robustness. The robot is able to complete missing information, such as failures by detecting objects.

- Improves the location: The robot constantly perceives elements congruent with the knowledge about its location. For example, if it perceives a sofa, it confirms that it is in a living room.

- Efficiency: When calculating a route, you do not need to explore the entire environment. It is possible to focus on a specific area for partial exploration.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents different mechanisms for semantic information acquisition in robot navigation applications, focusing on whether the acquisition is fully autonomous or assisted by a human. After acquiring the information, it is important to study formalisms to represent and handle that knowledge. Section 3 reviews the main trends in knowledge representation. The high-level (semantic) knowledge allows for richer navigation. In this regard, Section 4 explores the principles of semantic navigation, describing the main elements that constitute a semantic navigator. The current study raised a series of open issues that are reviewed in Section 5 and, finally, Section 6 reviews the main contributions of this work.

3. Representation of Semantic Knowledge

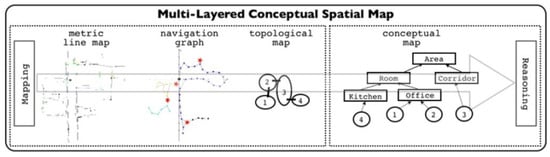

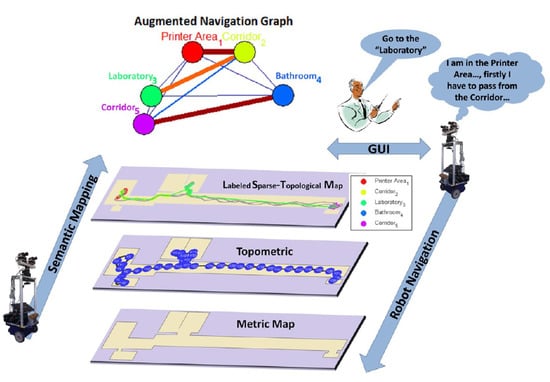

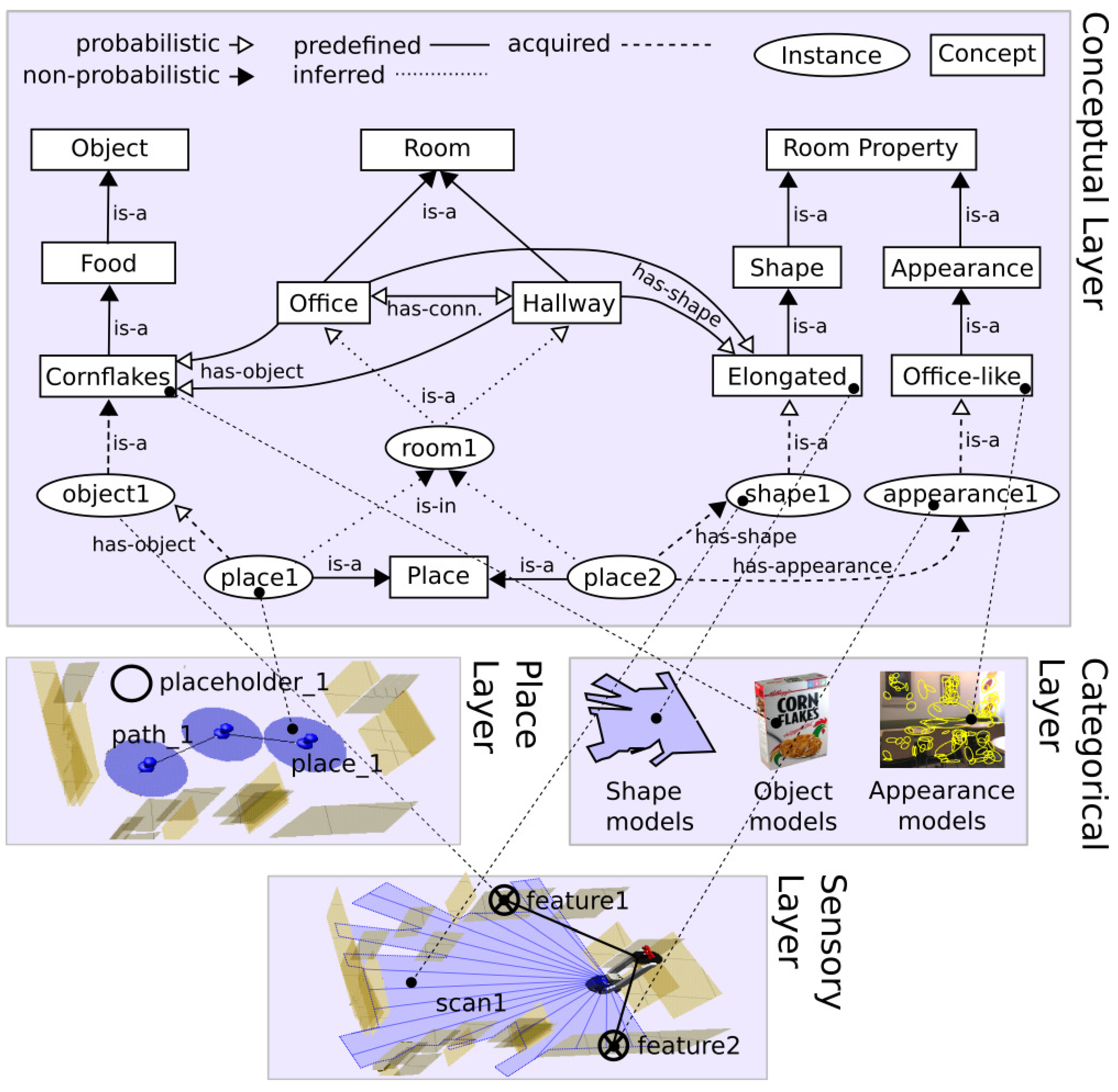

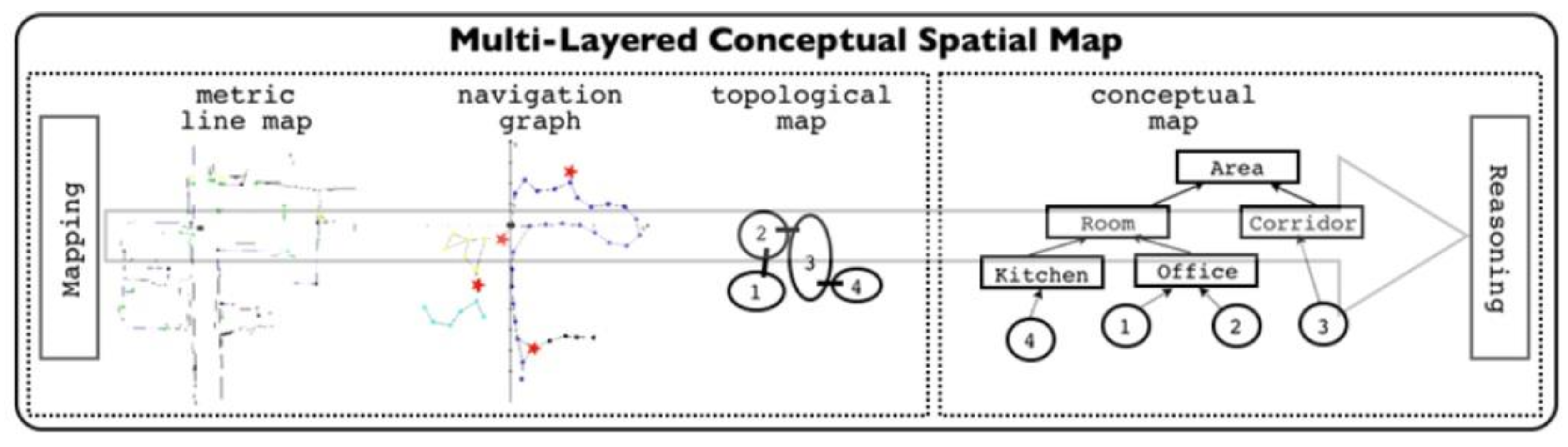

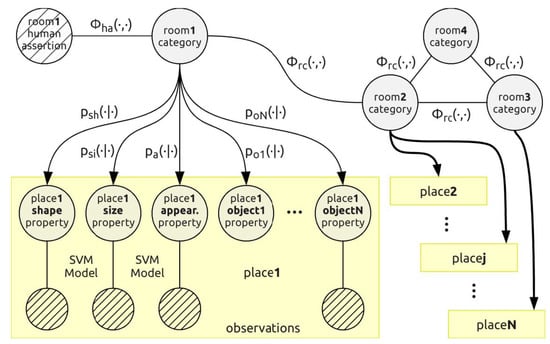

The literature offers different ways of representing high-level knowledge in navigation tasks. Semantic navigation approaches builds upon some of these knowledge representation paradigms. This is the case of Pronobis and Jensfelt that propose a spatial representation in a layered structure [17] as shown in Figure 3. This representation can describe usual knowledge as relationships between concepts (e.g., a kitchen contains-the-object cereals). Additionally, instances of knowledge are described as relations between instances of concepts (object-1 is-an-instance-of cereals), or relations between instances and other instances (place X has–the-object object Y). Relationships in the conceptual map can be predefined, acquired or inferred. These relations can also be deterministic or probabilistic (modelling uncertainty). This semantic navigation system bases inference on deductions on the unexplored space, such as predicting the presence of objects in a location with a known category. Additionally, this system is able to predict the presence of a room in unexplored space. Adding features to objects can also provide useful information since they can modify the functionalities of the objects [19]. For instance, a broken chair may not be used for sitting and be located in a workshop instead of in a living room.

Figure 3.

Spatial representation in a layered structure [17]. The conceptual layer contains concepts knowledge, relationships between concepts and spatial entities instances.

Galindo et al., presented one of the first works in the semantic navigation field, introducing multi-hierarchical models of representation [13]. This work proposed NeoClassic as a tool for representing knowledge and Descriptive Logics (DL) as inference mechanism [77]. The inputs to the classification system are outlines and, therefore, simple volumes, such as boxes or cylinders, represent furniture.

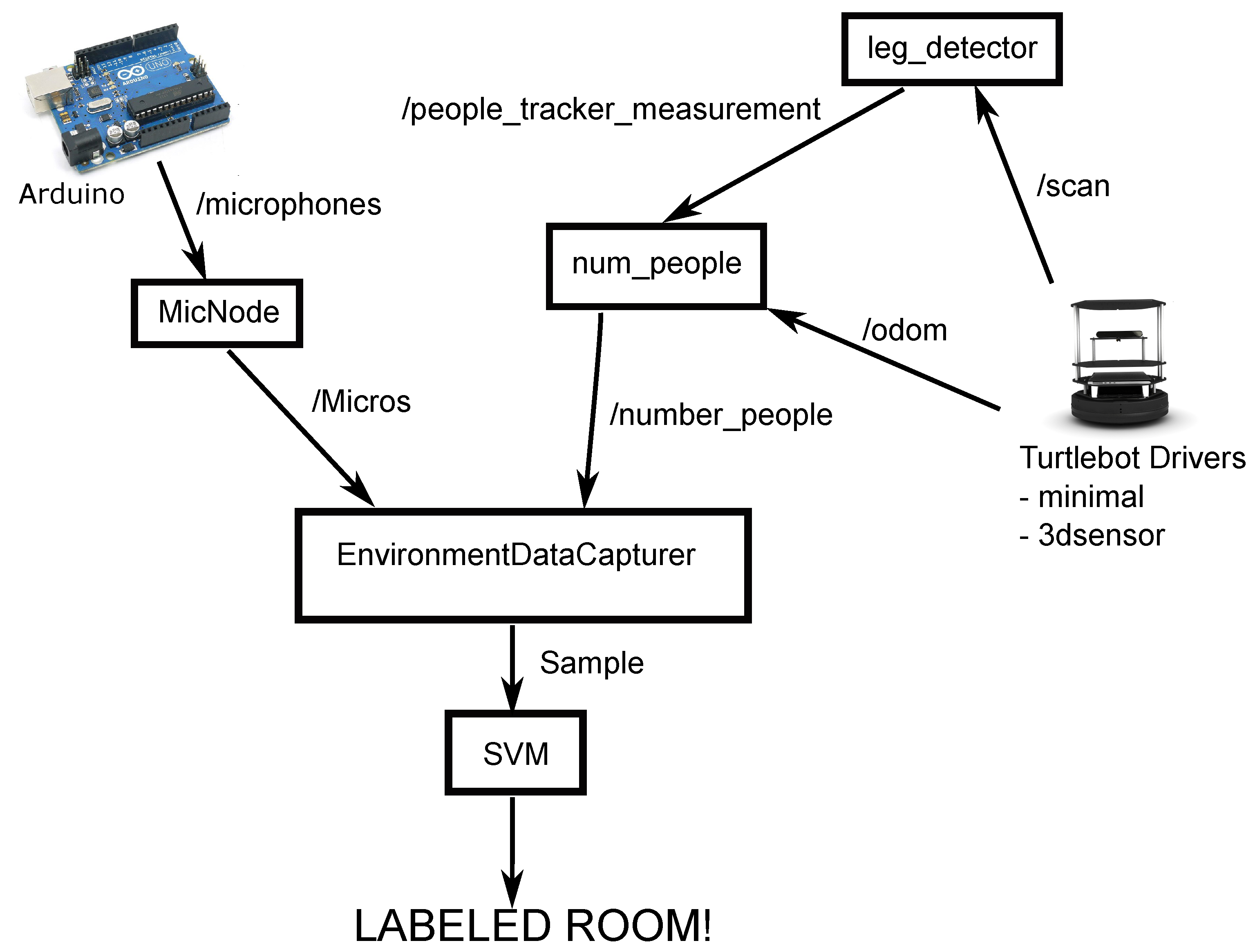

Some authors include features of the environment such as the sound level or the number of people in each room [78]. Gaps authors left in their conclusions haven been covered, such as the problem of autonomously learning new properties and categories of rooms by the robot, heading to an auto extensible semantic mapping. Ruiz-Sarmiento et al., introduce a novel representation of a semantic map called Multiversal Semantic Map [79]. The authors provide measures of uncertainty when they categorize an object into degrees of belief. An object can be labelled as a microwave with a certainty of 0.6 and as a bedside table with 0.4, for example. This type of semantic map contains all the categories considering all the possibilities. The work of Galindo et al. [13] was extended and different combinations of possible bases or universes were considered, such as instances of ontologies [80] with annotations of belief (certainty) about the concepts and relationships that are useful fundamentals.

The potential of this representation was extended in subsequent works that implemented semantic navigation schemes. For example, the planner was improved in Galindo et al. [81] and a more recent work includes autonomous generation of objectives [82]. The work of Zender et al., follows a similar line but, in this case, the multi-hierarquical representation is replaced by a simple hierarchy [15]. This is achieved by moving the map data from sensors to conceptual abstractions. The tool selected to code this information was Ontology Web Language-Description Logic (OWL-DL), resulting in an ontology that defined an office domain.

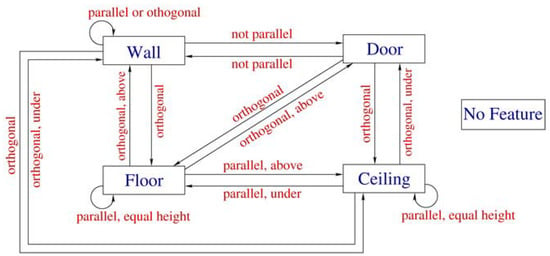

Other authors, such as Nüchter and Hertzberg, use Prolog to implement networks of constraints that code properties and relations between the different flat surfaces of a building (walls, floor, ceiling and doors) [83]. The classification is based on two techniques: contour detection and a cascade of classifiers that use distance and reflectivity data.

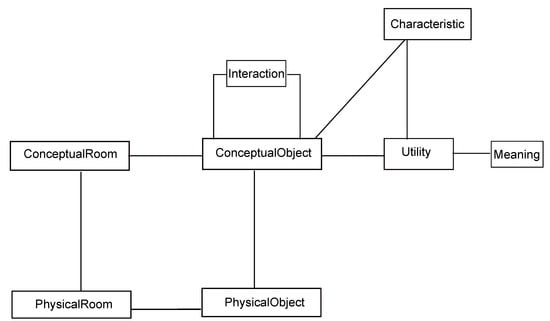

Other acquisition systems, representation systems and use of semantic maps can also be found. One example is KnowRob-Map by Tenorth et al., where Bayesian logics networks are used to predict the location of objects according to their relationships [84]. All of this is implemented in SWI-Prolog and using an OWL-DL ontology. They use networks with Bayesian logic to predict where an object can be (within the semantic environment) based on their relationships. For example, if a knife is used to cut meat, meat is cut for cooking and the kitchen is the place to cook, the knife can be in the kitchen. In contrast, The ontology of concepts that represents semantic knowledge can be seen as lists implemented using a database scheme [19] as shown in Figure 4. The reasoning can be performed as queries to the database. Alternatively, the ontology can be translated into lists of facts and rules and inferences can be made through a reasoning engine such as NeoClassic [13].

Figure 4.

Knowledge representation on concept lists linked each other [19].

From these works, ontologies can be considered as the tool to formalize semantic knowledge.

In robots navigation tasks, the way of mapping the environment is an essential stage. The type of map for the navigator depends on the abstraction level, resulting in different kinds of navigation. In a geometric navigator, the required mapping information corresponds to distances from the robot sensors [85]. The map in these approaches aims to distinguish those zones in the space corresponding to obstacles from the accessible areas. In contrast, topological navigators use the connectivity between different areas to model the environment [86]. This allows building a tree-like space representation to calculate routes. Pronobis and Jensfelt added one extra level of abstraction, performing what they call semantic mapping [17]. This work considers applications where the robot moves in domestic or office environments, created by and for humans. Concepts such as rooms, objects and properties (such as the size and shape of the rooms) are important in the tasks of representing knowledge and generate efficient behaviours in the robot.

3.1. Ontologies

Ontologies are formal tools to describe objects, properties, and relationships in a knowledge domain. According to Prestes et al., two definitions capture the essence of the purpose and scope of ontologies [87]: On the one hand, Studer et al., building on the initial works of Gruber et al. [12], stated that an ontology is “an explicit formal specification of a shared conceptualization” [88]. On the other hand, the work of Guarino considered an ontology as a series of “logical theories that explain what a vocabulary tries to transmit” [89]. Therefore, we can establish that an ontology is constituted by a set of terms and their definitions as shared by a given community, formally specified in a language readable by a machine, such as first-order logic. More specifically, in the field of robotics, ontologies for representing knowledge are useful as they allow building models of the environment in which relevant concepts are hierarchically related to each other. In general terms, ontologies are composed by classes, which represent concepts at all levels, relations, which represent associations between concepts, and formal axioms, which are restrictions or rules that provide consistency to the relationships [90].

Even though ontologies have in common these elements, there are different ways to classify and differentiate them. Prestes et al., group ontologies by their level of generality, separating them in four kinds [87]. (i) Top-level ontologies describe general concepts such as space, time, objects, events, actions, etc. This generality makes them suitable for different domains. (ii) Domain ontologies describe concepts oriented to solve different problems if they are in a specific domain. Concepts relative to a domain ontology for a home environment could be a living room, a kitchen, a couch, sitting, etc. (iii)Task ontologies describe tasks or generic activities (e.g., grab something). And, finally, (iv) application ontologies are associated with one particular domain and to one task. task (e.g., fry an egg).

3.2. Cognitive Maps

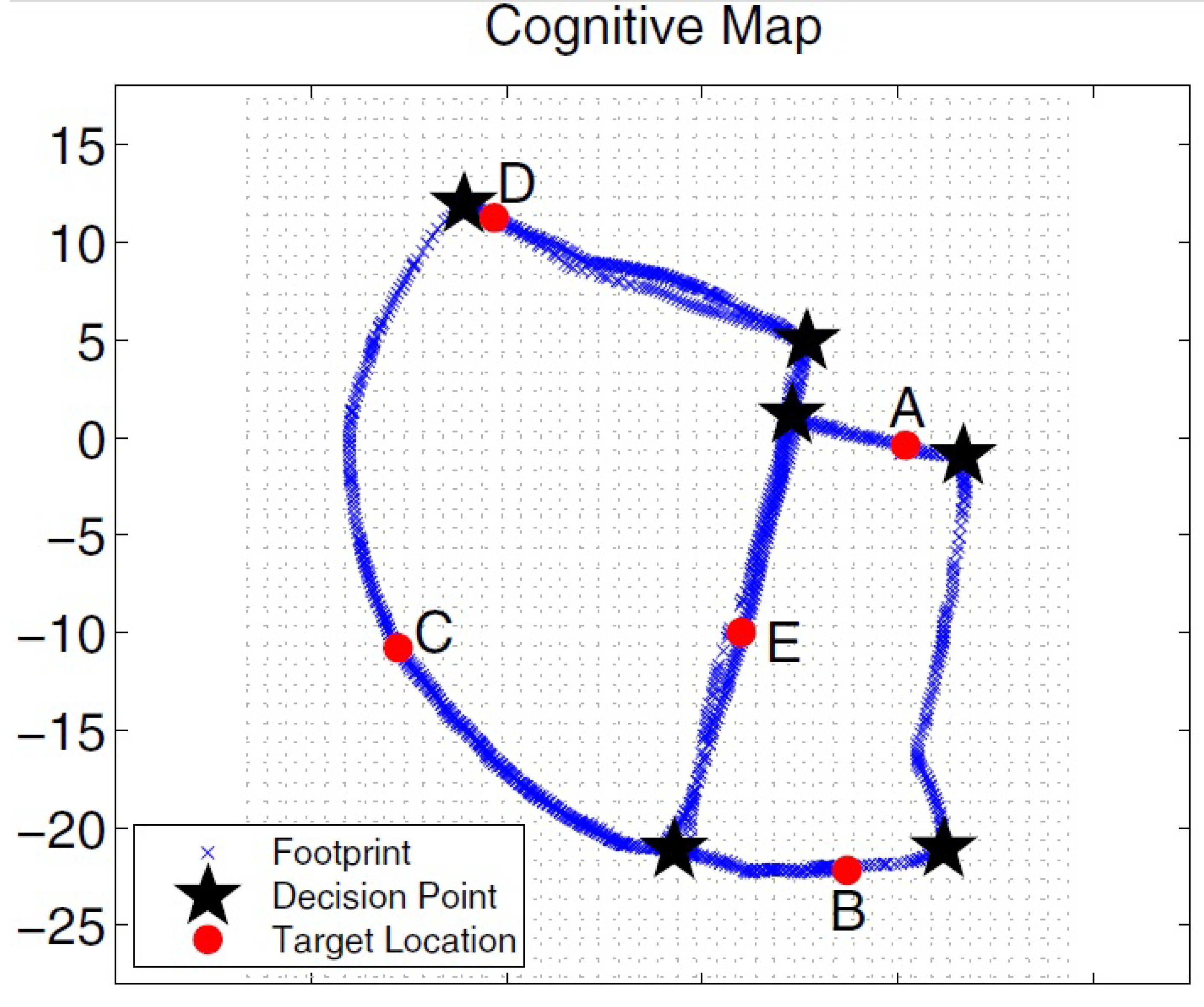

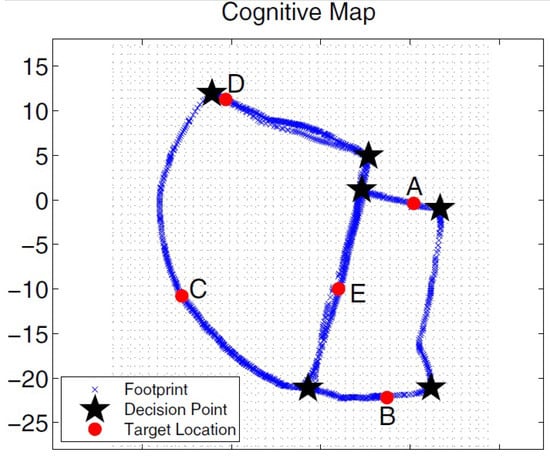

When building cognitive maps, knowledge is extracted from present and historical information (previous knowledge), imitating the mechanisms of the human brain to solve complex cognitive problems in a flexible way [91]. This study concluded that, when asking people to describe concepts related to places (living room, kitchen, etc.), the definitions were usually built using the objects these places contain. Following these ideas, Milford et al., presented RatSLAM, a computational model of the hippocampus of rodents developed with Continuous Attractor Networks (CAN) of three dimensions that translate the robot position of the robot in the position of cells [92]. Shim et al., presented a mobile robot that uses a cognitive map for navigation tasks [93]. The map is built using a RatSLAM approach with an RGB-D sensor [28] which added depth information, invariable to lighting conditions. The cognitive map generated by its version of the RGB-D-based cognitive mapping algorithm is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Cognitive map generated with a version of the cognitive map construction algorithm based on RGB-D [93].

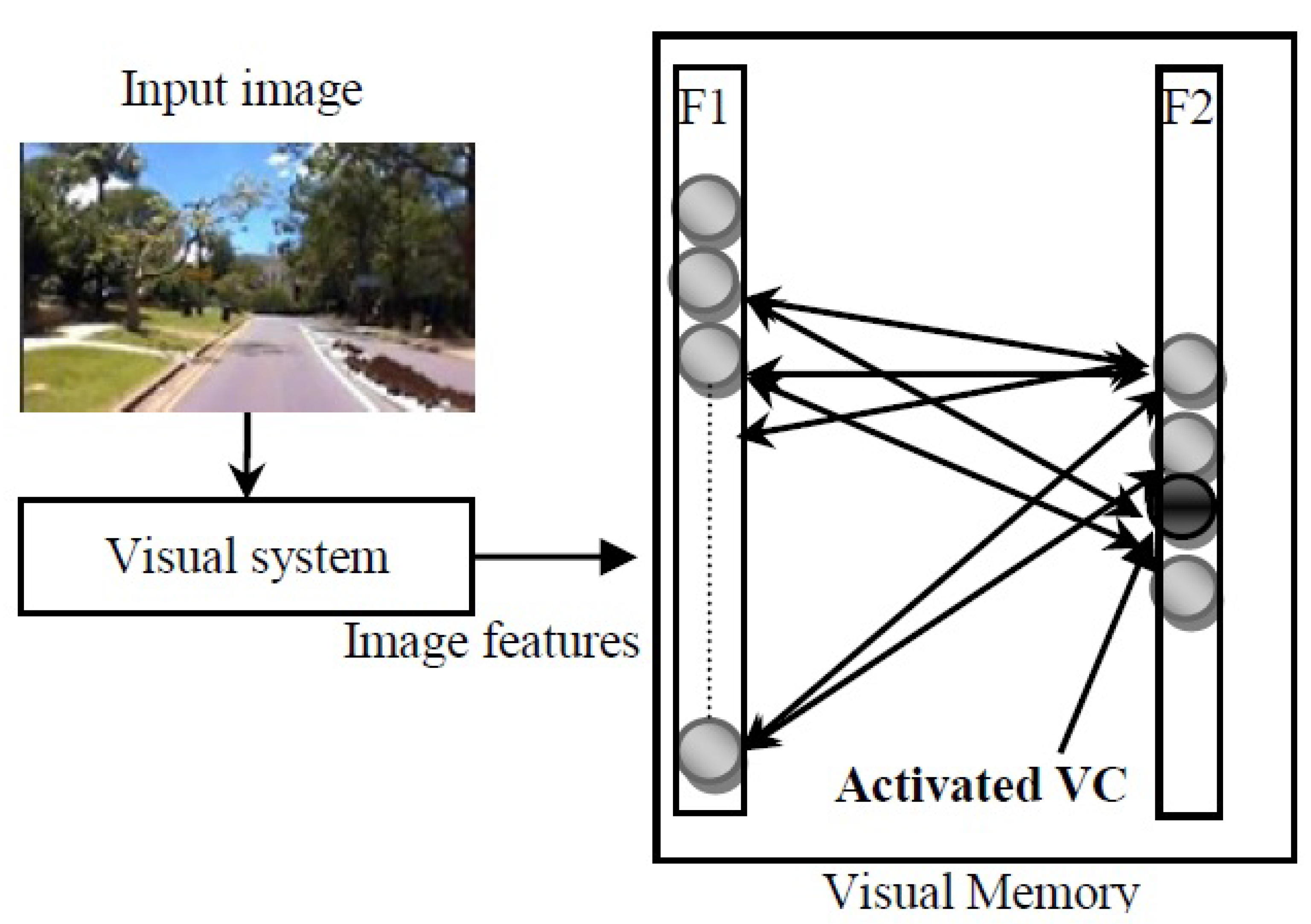

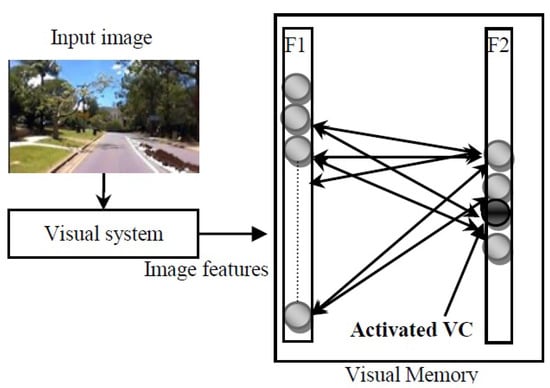

Cognitive maps have been applied in scene recognition. For example, Rebai et al., presented an approach for indoor navigation that builds a visual memory that allows spatial recognition without storing visual information [94]. This approach builds the visual memory using Fuzzy ART, a model capable of rapid stable leaning of recognition categories in response to arbitrary sequences [95]. Authors propose this idea as a way of imitating the biological processes that encode spatial knowledge, mimicking how animals recognize previously visited places through cognitive maps. To achieve this, data association mechanisms are implemented to describe the robot environment that allows recognizing places already visited [96]. The system consists of constructing an incremental visual memory using Fuzzy ART and the visual features are used as input signals to create a visual cell representing the perceived scene (see Figure 6). In addition to this a bio-inspired process of Visual attention (VATT) is obtained, consisting of processing a certain part of the scene with more emphasis, while the rest is dismissed or suppressed.

Figure 6.

Cognitive map modules based on visual memory [94].

The authors also indicate that this idea is exploited in the construction of cognitive maps and recognition of places using visual localization [97], besides being applied in navigation of mobile robots. At these points is where it makes sense to study it for this paper.

3.3. Semantic Maps

Semantic mapping is the map that takes into account complex semantic concepts of the environment, such as objects and their usefulness, different types of rooms and their uses, subjective sensations transmitted by a place in a user, etc. These concepts are related to each other offering valuable information about the environment that is reflected in the semantic map.

Being aware of the implications of the choice of technology and the level of abstraction to be used in the mapping, Wu et al., considered of great importance the application that has the mapping in service robots and present a hybrid model of the semantic map [98]. Classifying the navigation maps into two categories: the metric maps and the topological maps. To reach a map with the advantages of both categories and reducing the limitations, the hybrid maps [99] outstand. All belong to traditional maps and focus on representing the geometric structure of space, describing the quantitative coordinates and connectivity between locations. However, the functionality of the locations and the complexity of the partial space are not considered. Nor are high-level semantic concepts used to interact with people. This situation where the robot planner, location and navigation based on these types of maps do not meet the needs of the robot’s service tasks, motivated the definition of semantic maps [98], as a more suitable option than cognitive maps.

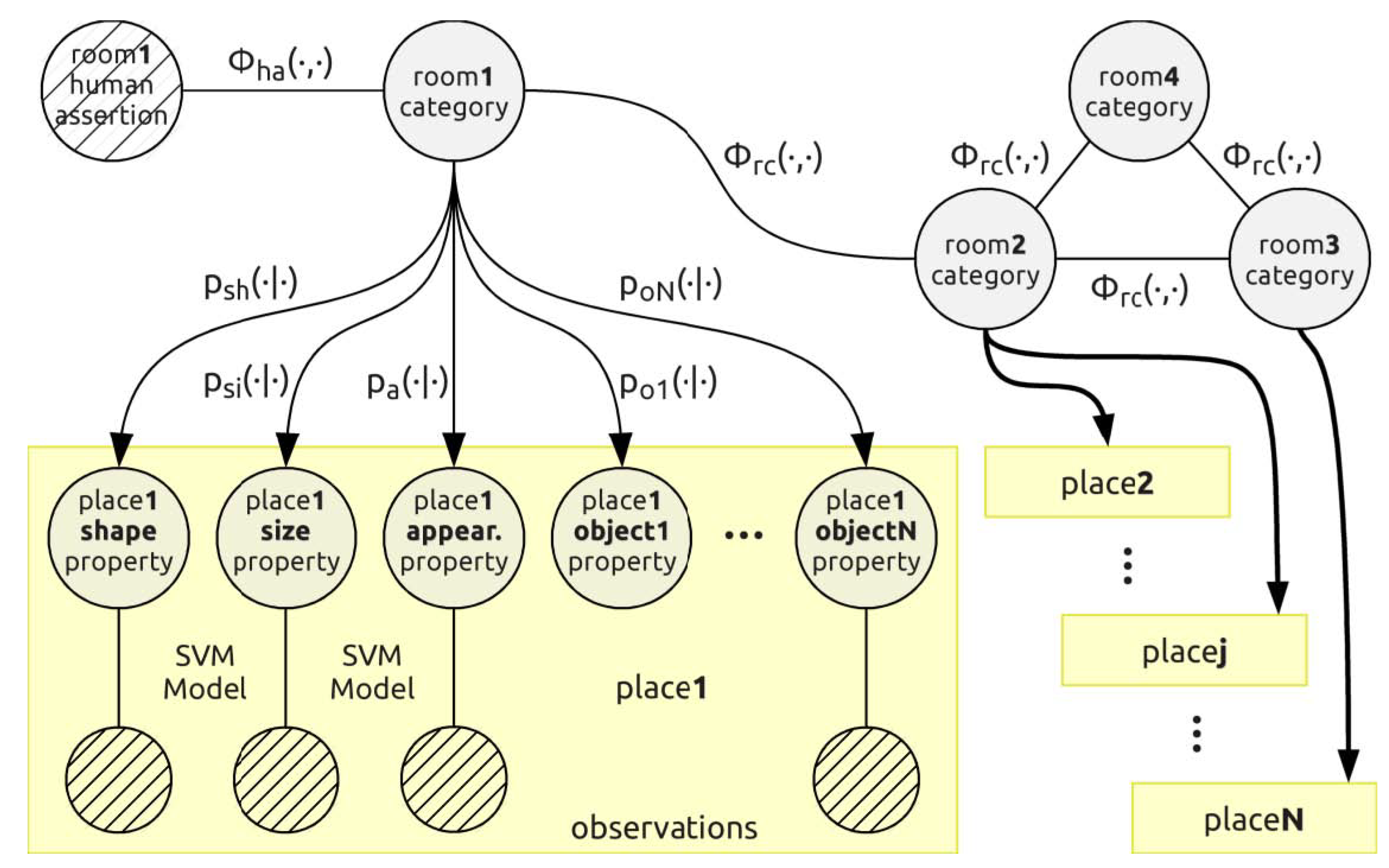

The paradigm of the development of semantic maps used by Pronobis and Jensfelt is based on space properties [17]. These properties can be described as attributes that characterize discrete space entities identified by the robot, such as places, rooms, or locations. Additionally, the properties make them correspond with human concepts and provide another layer of spatial semantics shared between the user and the robot. Each property is connected to a sensory information model. High-level concepts, such as room types, are defined by properties.

- Objects. Each object class corresponds to a property associated with the place. A particular location is expected to display a certain number of a particular type of object, and a certain amount of them is observed.

- Door. Determines whether a location is determined by a door.

- Shape. The geometric form of the room extracted from the information of laser sensors.

- Size. The relative size of the room extracted from the sensory information of the laser.

- Appearance. The visual appearance of a place.

- Associated space. The amount of free space visible around a placeholder not assigned to any place.

Conceptual map is shown in Figure 7. Every specific instance of the room is represented by a set of random variables, one for each property associated with that place.

Figure 7.

Structure of conceptual map graph model [17].

Entering into concepts of creation of semantic maps (without being the same as a cognitive map), some works explore this concept and its application in mobile robotics. Nuechter and Hertzberg proved that semantic knowledge can help a robot in its task of reaching a destination [83]. And part of this knowledge has to be due to objects, utilities, events or relationships in the robot environment. The data structure that supports space-related information about this environment is the map. A semantic map increases the typical geometric and/or topological maps with information about entities (objects, functionalities, etc.) that are located in the space. This implies the need to add some mechanism of reasoning with some previous knowledge. In this way, a semantic map definition is reached:

A semantic map in a mobile robot is a map that contains, in addition to spatial information about the environment, assignments of mapped features of known class entities. In addition to the knowledge of these entities, regardless of the content of the map, some kind of knowledge base must be available with an associated reasoning engine for inferences [83].

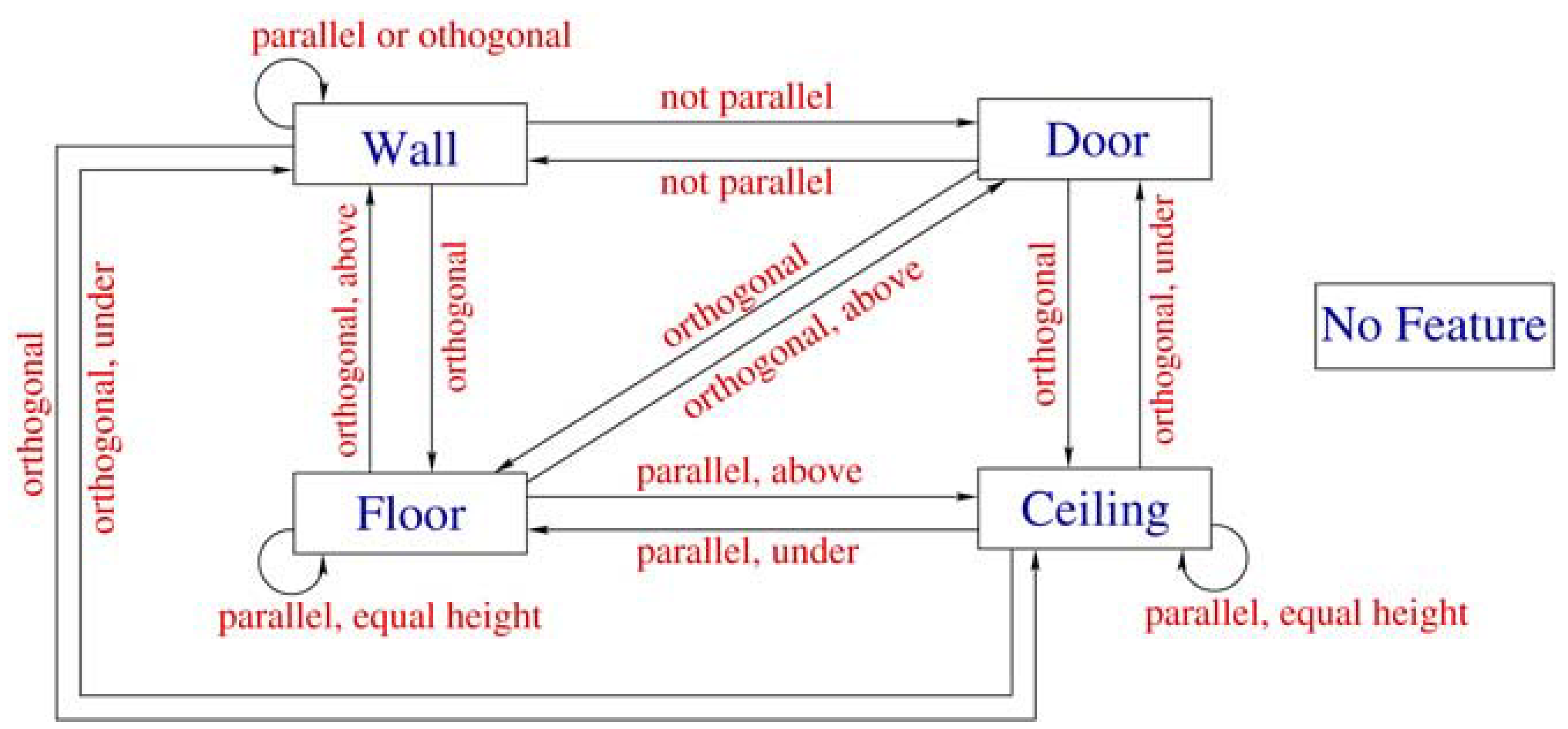

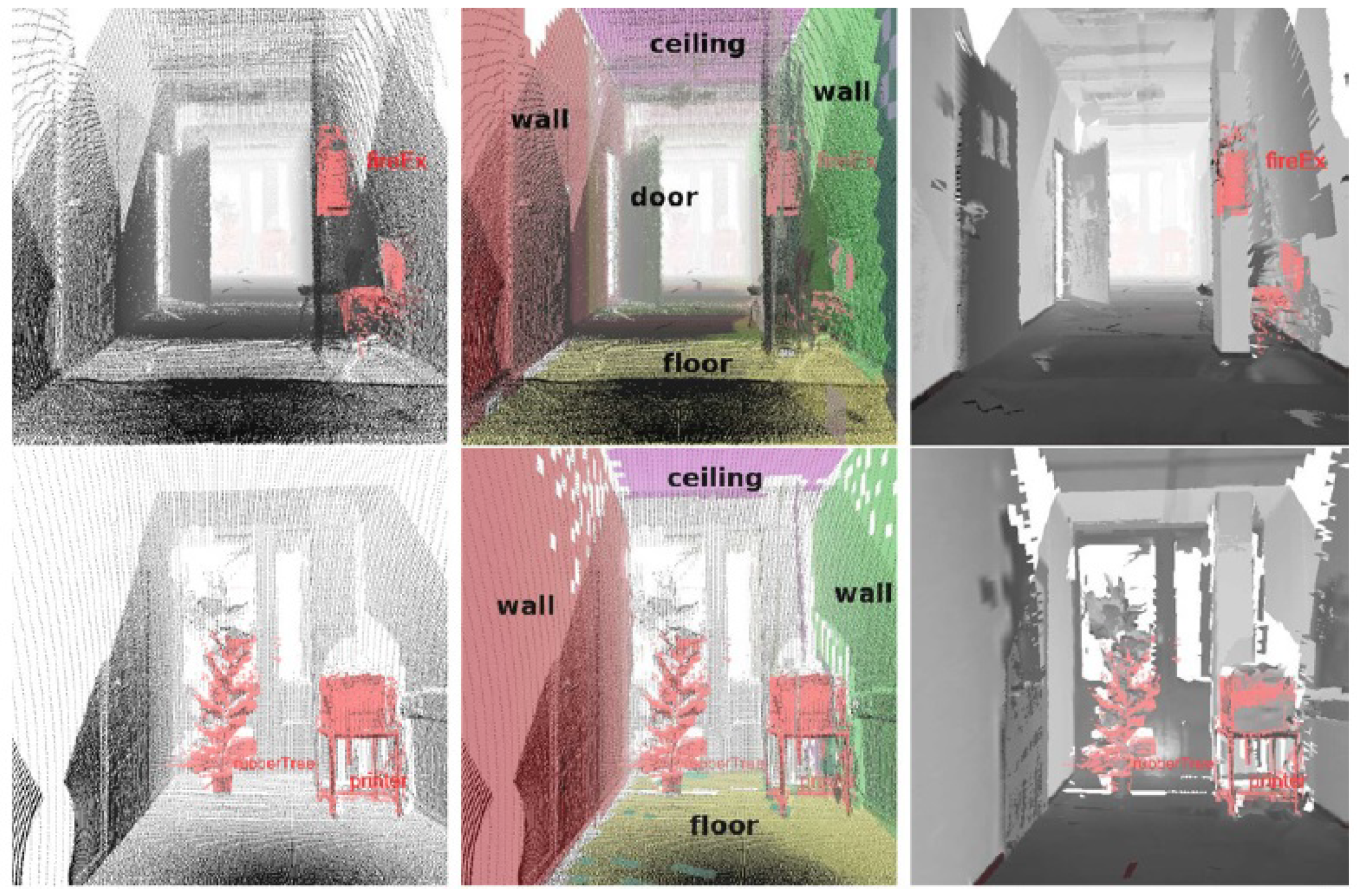

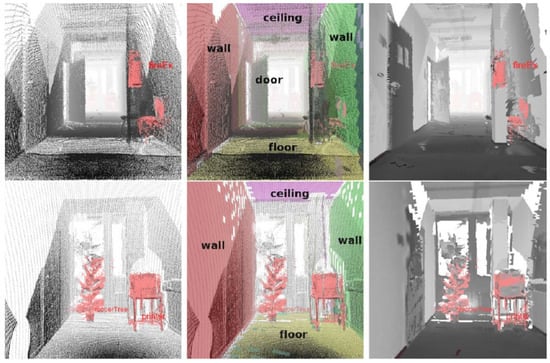

The differentiation of elements of the environment is called as semantic mapping by many authors, also in outdoor navigation works. Li et al., they differentiate in the image that perceived from the environment what is road, sidewalk, wall, terrain, vegetation, traffic sign, pole and car [100]. Returning to indoor navigation, in the case of work that has already been mentioned [83], the authors focused on differentiating the following elements from the environment: wall, door, floor and ceiling. Rules were created using Prolog to implement the restrictions of the characteristics that differentiate the classes, being these purely visual. In Figure 8 the network of restrictions that defined these elements is shown, while Figure 9 shows the result of the object detection such as the fire extinguisher, a printer and an indoor tree in a flowerpot. The low-level mapping was a 3D SLAM.

Figure 8.

Contrains for a scene interpretation [83].

Figure 9.

Rendered image for an office 3D semantic map [83].

Once the image was rendered, a classification was carried out considering the outline of the objects apart from the depth and camera images. Then, the points corresponding to the 2D projection of the object (ray tracing) were chosen. Then it was paired with a 3D model at those points, followed by an evaluation step.

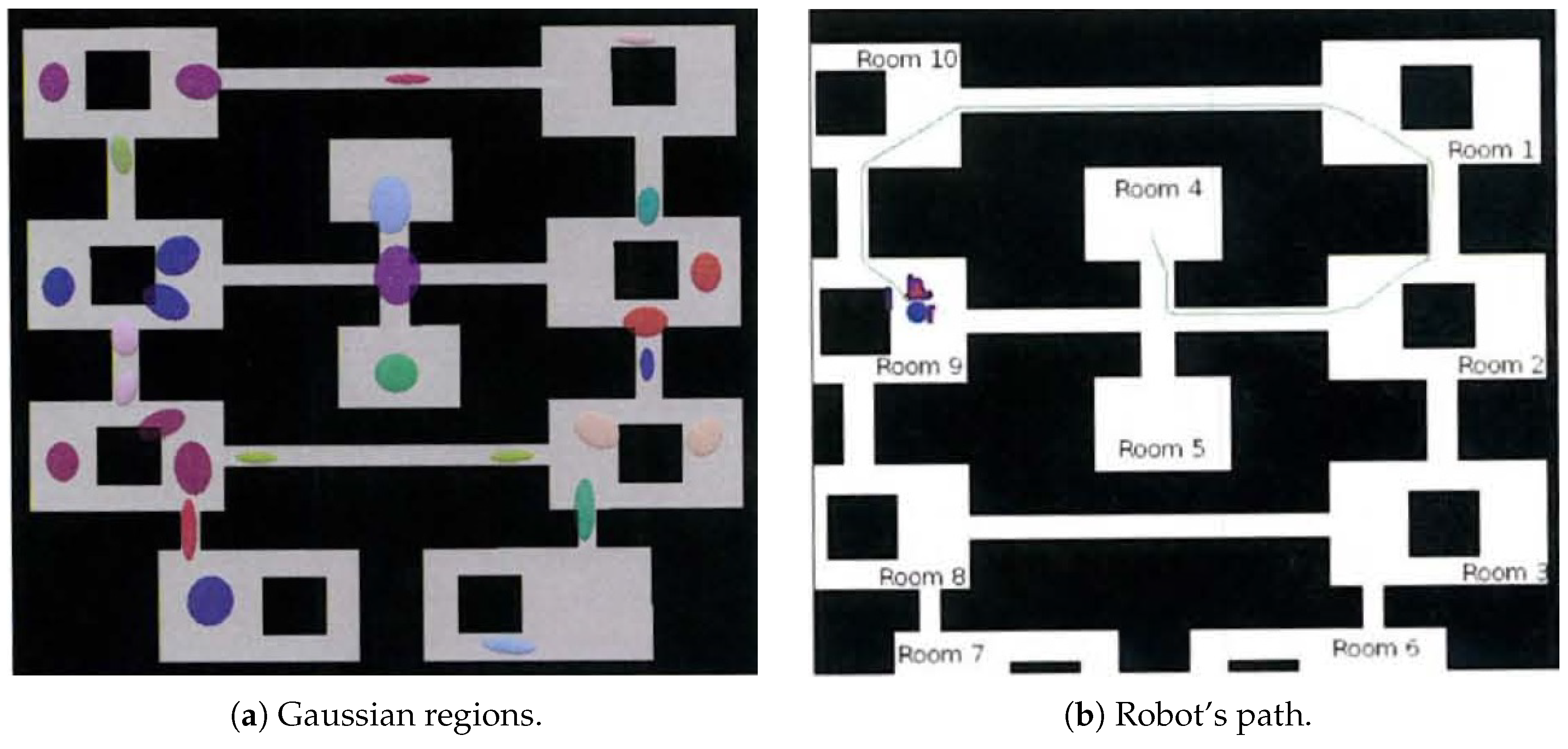

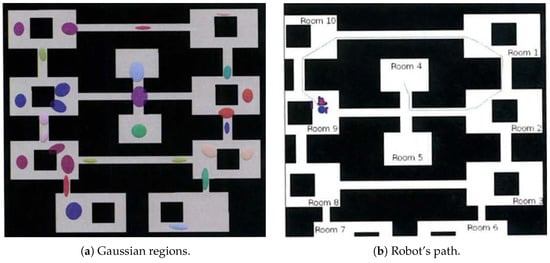

Nieto-Granda et al., also implemented a semantic map, responding to the need to classify regions of space [16]. Methods for automatically recognizing and classifying spaces are presented. Separating semantic regions and using that information to generate a topological map of an environment. The construction of the semantic map is done with a human guide. The partition of this map provides a probabilistic classification of the metric map, assigning labels, leaving for a future work the automatic assignment of these labels (a topic later solved in other works such as the proposal of Crespo et al. [19]). The symbolic treatment of the map and a path taken by the planner is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Rooms and dooways represented by Gaussian regions and the robot’s path to room 4 from room 9 [16].

For these authors, the literature of semantic mapping has focused on developing mapping techniques that work by supporting human interactions, so that the representation of space is shared. One of the strategies used is to represent the relationship between a place and the knowledge associated with it (including the functionality of the place and the location of the objectives). Unlike works like Mozos et al. [57], which construct a topological map on a geometrical map, provide a continuous classification of the geometric map in regions labelled semantically. This multi-variable distribution is modelled as a Gaussian model. Each spatial region is represented using one or more Gaussian in its geometric map coordinate framework.

Naik et al., recently proposed a graph-based semantic mapping approach for indoor robotic applications that builds on OpenStreetMap [101]. This work introduces models for basic indoor structures such as walls, doors, corridors, elevators, etc. The models allows querying for specific features, which allows discovering task-relevant features in the surrounding environment to improve the robot planner.

Kuipers proposed a quantitative and qualitative model of space knowledge on a large scale [102], based on multiple representations of interaction and serves as the basis for previous authors in the representation of relations of objects, actions and dependencies of the environment. On a smaller scale of space, the work of Beeson et al., providing a representation of the more specific working environment [103].

5. Open Issues and Questions

An extensive review of literature in semantic information for robot navigation raises some interesting questions that practitioners should take into consideration.

Is a knowledge representation model better than another? When comparing between knowledge representation models it is important to establish comparison criteria. This is still an open problem since abstract representations of information are not easy to evaluate. Experts in psychology have not reached a consensus about the knowledge representation that our brain uses to process information. In fact, multiple analogies have been used to try to understand our internal representation.

How essential is an object recognition mechanism in navigation? In general, proposals for semantic navigation include a object detection mechanisms. Most of the semantic navigators need information about the objects in the scene to provide high-level classification of places. Therefore, an object recognition mechanism is a key feature to integrate into such systems and it is desirable having a system as generic as possible, that is, without the need to be trained to detect all specific objects in the environment. For instance, a system should be able to recognize a new instance of an object (e.g., a chair) in any environment without specific training for that chair. New machine learning techniques are leading the way to achieve a high level of generalization, but at the cost of great amounts of data for training [121,122].

Are there environments more suitable for semantic navigation than others? This question has been discussed by many researchers. Despite its advantages, it is not clear yet how robots that use current semantic-based techniques for navigation will coexist with humans. One of the concerns regards the number of people in the environment as robots using high-level semantic navigation rely on object detection. A crowded environment is more prone to multiple occlusions, thus reducing the chances for information acquisition. Some authors propose solutions to this problem, but still extensive experiments are necessary to define the kind of environments more suitable for this type of navigation techniques.

Indoor semantic navigation methods are reusable in outdoor environments? This issue is usually arises when a new semantic navigation system emerges. In the state of the art, there are semantic navigators for indoor and also for outdoor environments, but are they so different? It is reasonable to consider whether the progress in either application is usable on the another. The question that remains open is whether a navigator will emerge that serves both for indoors and outdoors, having defined ontologies wide enough to consider the two levels of relationships and the functional sensory ability for both situations.

What is still lacking to see robots in everyday environments such as homes, hospitals, etc.? Semantic navigation involves several disciplines of robotics. For this reason, aspects such as object recognition and human-robot interaction must be integrated with a robust low-level navigation system.

What applications, other than navigation, can benefit from the same semantic map scheme? The management of semantic knowledge and the management of ontologies can be applied to other tasks apart from navigation. The RoboEarth project includes a knowledge system implemented with Prolog that allows a robot to accomplish tasks like cooking a pizza. Therefore, it is reasonable to think that the inclusion of semantic maps can be useful to develop other tasks. It can also be applied to user interaction to obtain information of any kind, not only relative to the navigation. Besides, object detection can be improved with the inclusion of the semantic map. This means that many applications can be improved by integrating techniques described in this work.

6. Conclusions

This contribution reviews the state of the art in mobile robot navigation paying special attention to the role of semantic information. From this idea, a high-level navigation category arises, that is, semantic navigation that can be defined as the ability of a robot to plan the path to its destination taking advantage of the high-level information provided by the elements of the environment. Exploiting this information in the real world allows more optimal navigation.

To achieve high-level navigation, some previous steps must be considered. First, information acquisition allows identifying the main components in the environment following two procedures. This process can be eased by interacting with humans, who will provide the information pieces required or, conversely, the robot can autonomously detect people, objects and other elements in the environment.

This ability to acquire information is an open problem that has been addressed in the contributions mentioned in the present work. In the case of autonomous detection, the elements found in the environment will be limited by the sensors the robot includes. There is a difference, therefore, between acquiring information directly from the environment and acquiring knowledge from interaction with humans since this last option allows more abstract relationships. The first case deals with the idea of recognizing objects, shapes, corners, or any item suitable for obtaining information from the environment. In this case, multiple techniques for object detection, segmentation and frame analysis have been included. In the second case, it deals with the idea of the system being able to learn new concepts, such as relationships. The most widespread technique among the authors facing this problem is the robot’s dialogue with a human user. Through this dialogue or interaction with the user, the robot learns new concepts. Interaction with humans is, therefore, a useful ability from two points of view. On the one hand, through the interaction the system recognizes the objective of the navigation. On the other hand, using interaction, the system can learn some concepts. From the works presented in this paper, it can be stated that interaction by voice and dialogue predominates. However, some authors choose a display or keyboard interface.

In this paper, different types of maps have also been reviewed. These maps can be used in semantic navigation. Two types of maps can be distinguished according to what different authors have been discussing, that is, semantic and cognitive maps. All authors agree that the way of mapping the environment define the navigation to be carried out. As more general conclusions, it is observed that the bio-inspired models are important. An attractive feature for semantic navigation is that it works with abstractions similar to those performed by humans to plan their path and classify their environment according to their usefulness.

The ability to reason is one of the main capabilities of a high-level navigator. The more concepts it can manage, the more knowledge it can extract. This allows that even when there is very little information, non-specific information or very abstract information, the robot reaches its destination. The works that have included concepts of high-level of abstraction have used ontologies that allow them to manage conceptual hierarchies. In this case, some reasoning system is added. These systems extract information and make inferences about the defined ontologies. The systems reviewed include a series of reasoning techniques, such as behaviour trees, finite state machines, reasoners based on descriptive logics and reasoners that access relational databases. These reasoners are identified as flexible and powerful, while those that access relational databases are faster and can work with a larger volume of concepts.

Regarding the components that a semantic navigation approach has to implement, different authors identified some common grounds. These are the low-level navigator, a high-level navigator and an interface that links both. The high-level navigator must allow working with a level of abstraction enough to represent semantic concepts of the environment to recognize and classify places. These minimum components are complex enough to generate different research directions within the semantic navigation. In this paper, works focused on one or more of the capabilities of the high-level navigator have been gathered.

From a technical point of view, it has been discussed that, although many works deal with some issue related to semantic navigation, there are not so many complete semantic navigators. However, some works provide interesting solutions to many of the problems separately. It can be expected that in the short or medium term, systems will emerge from the idea of integrating the different partial solutions.

For all this, it is foreseen that semantic navigation will improve in the next years, incorporating better systems for objects detection, as well as more general systems of reasoning and interacting with the user.

This survey required thorough bibliographical research in well-known databases. We used mainly Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), and Google Scholar. About the topics surveyed, we tried to cover the main aspects relative to semantic navigation, such as mapping, information acquisition, human-robot interaction, inference and reasoning, etc. Therefore, these were the main keywords derived from these topics. For the papers gathered in this survey, we considered those contributions that addressed one or more aspects related to a semantic navigation system. Additionally, some papers were included to explain concepts related to those fields (e.g., computer vision algorithms that were later integrated into a semantic navigation system).

Author Contributions

J.C. collected literature resources and wrote the original draft, J.C.C. updated literature resources and re-wrote (review and editing), O.M.M. validated and reviewed the manuscript. R.B. supervised and coordinated all activities. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from HEROITEA: Heterogeneous 480 Intelligent Multi-Robot Team for Assistance of Elderly People (RTI2018-095599-B-C21), funded by Spanish 481 Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad. The research leading to this work was also supported project “Robots sociales para estimulacón física, cognitiva y afectiva de mayores” funded by the Spanish State Research Agency under grant 2019/00428/001. It is also funded by WASP-AI Sweden; and by Spanish project Robotic-Based Well-Being Monitoring and Coaching for Elderly People during Daily Life Activities (RTI2018-095599-A-C22).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kostavelis, I.; Gasteratos, A. Semantic maps from multiple visual cues. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 68, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostavelis, I.; Gasteratos, A. Semantic mapping for mobile robotics tasks: A survey. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2015, 66, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollar, T.; Roy, N. Utilizing object-object and object-scene context when planning to find things. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arras, K. Featur-Based Robot Navigation in Know and Unknow Environments. Ph.D. Thesis, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chatila, R.; Laumond, J. Position referencing and consistent world modeling for mobile robots. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, St. Louis, MO, USA, 25–28 March 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G.; Yin, L.; Jin, S.; Tian, C.; Ma, X.; Ou, Y. A Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) Framework for 2.5D Map Building Based on Low-Cost LiDAR and Vision Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choset, H.; Nagatani, K. Topological Simultaneous Localization And Mapping (SLAM): Toward exact localization without explicit localization. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 2001, 17, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapus, A. Topological SLAM-Simultaneous Localization And Mapping with Fingerprints of Places. Ph.D. Thesis, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, L.; Wu, C.; Chu, H. Topological Map Construction Based on Region Dynamic Growing and Map Representation Method. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrun, S. Learning metric-topological maps for indoor mobile robot navigation. Artif. Intell. 1998, 99, 21–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomatis, N.; Nourbakhsh, I.; Siegwart, R. Hybrid simultaneous localization and map building: A natural integration of topological and metric, Robotics and Autonomous Systems. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2003, 44, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.R. Toward Principles for the Design of Ontologies Used for Knowledge Sharing. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 1995, 43, 907–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, C.; Saffiotti, A.; Coradeschi, S.; Buschka, P.; Fernández-Madrigal, J.A.; González, J. Multi-hierarchical semantic maps for mobile robotics. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Edmonton, AL, Canada, 2–6 August 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Rodicio, E.; Castro-González, Á.; Castillo, J.C.; Alonso-Martin, F.; Salichs, M.A. Composable Multimodal Dialogues Based on Communicative Acts. In Social Robotics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zender, H.; Mozos, O.M.; Jensfelt, P.; Kruijff, G.J.M.; Burgard, W. Conceptual spatial representations for indoor mobile robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. (RAS) 2008, 56, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Granda, C.; Rogers, J.G.; Trevor, A.J.B.; Christensen., H.I. Semantic Map Partitioning in Indoor Environments using Regional Analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEEl/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pronobis, A.; Jensfelt., P. Large-scale semantic mapping and reasoning with heterogeneous modalities. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA’12), St. Paul, MN, USA, 14–18 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Peltason, J.; Siepmann, F.H.K.; Spexard, T.P.; Wrede, B.; Hanheide, M.; Topp, E.A. Mixed-initiative in human augmented mapping. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, J.; Barber, R.; Mozos, O. Relational Model for Robotic Semantic Navigation in Indoor Environments. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2017, 86, 617–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, R.; Crespo, J.; Gomez, C.; Hernandez, A.C.; Galli, M. Mobile Robot Navigation in Indoor Environments: Geometric, Topological, and Semantic Navigation. In Applications of Mobile Robots; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruijff, G.J.M.; Zender, H.; Jensfelt, P.; Christensen, H.I. Clarification Dialogues in Human-augmented Mapping. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCHI/SIGART Conference on Human-robot Interaction, HRI ’06, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2–3 March 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hemachandra, S.; Kollar, T.; Roy, N.; Teller, S.J. Following and interpreting narrated guided tours. In Proceedings of the Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gemignani, G.; Capobianco, R.; Bastianelli, E.; Bloisi, D.D.; Iocchi, L.; Nardi, D. Living with robots: Interactive environmental knowledge acquisition. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2016, 78, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerke, N.; Braun, S. Building Semantic Annotated Maps by Mobile Robots. In Proceedings of the Towards Autonomous Robotic Systems, Londonderry, UK, 15 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brunskill, E.; Kollar, T.; Roy, N. Topological mapping using spectral clustering and classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ Conference on Robots and Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 29 October–2 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, S.; Pasula, H.; Fox, D. Voronoi random fields: Extracting the topological structure of indoor environments via place labeling. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Hyderabad, India, 6–12 January 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Christensen, H.I.; Rehg, J.M. Visual place categorization: Problem, dataset, and algorithm. In Proceedings of the IROS’09, St. Louis, MO, USA, 10–15 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, B.; Shim, V.A.; Yuan, M.; Srinivasan, C.; Tang, H.; Li, H. RGB-D based cognitive map building and navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, J.; Gómez, C.; Hernández, A.; Barber, R. A Semantic Labeling of the Environment Based on What People Do. Sensors 2017, 17, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, D. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekvall, S.; Kragic, D.; Jensfelt, P. Object detection and mapping for service robot tasks. Robotica 2007, 25, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekvall, S.; Kragic, D. Receptive field cooccurrence histograms for object detection. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Edmonton, AL, Canada, 2–6 August 2005; pp. 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- López, D. Combining Object Recognition and Metric Mapping for Spatial Modeling with Mobile Robots. Master’s Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aydemir, A.; Göbelbecker, M.; Pronobis, A.; Sjöö, K.; Jensfelt., P. Plan-based object search and exploration using semantic spatial knowledge in the real world. In Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR11), Örebro, Sweden, 7–9 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Garvey, T.D. Perceptual Strategies for Purposive Vision; SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Mozos, O.M.; Marton, Z.C.; Beetz, M. Furniture models learned from the WWW—Using web catalogs to locate and categorize unknown furniture pieces in 3D laser scans. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2011, 18, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joho, D.; Burgard, W. Searching for Objects: Combining Multiple Cues to Object Locations Using a Maximum Entropy Model. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Astua, C.; Barber, R.; Crespo, J.; Jardon, A. Object Detection Techniques Applied on Mobile Robot Semantic Navigation. Sensors 2014, 14, 6734–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blodow, N.; Goron, L.C.; Marton, Z.C. Autonomous semantic mapping for robots performing everyday manipulation tasks in kitchen environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–30 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan, S.; Siegwart, R. A Bayesian approach to Conceptualization and Place Classification: Incorporating Spatial Relationships (distances) between Objects towards inferring concepts. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), San Diego, CA, USA, 29 October–2 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan, S.; Harati, A.; Siegwart, R. A Bayesian Conceptualization of Space for Mobile Robots: Using the Number of Occurrences of Objects to Infer Concepts. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Mobile Robotics (ECMR), Freiburg, Germany, 19–21 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, R.; Adachi, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Ishida, H.; Kobayashi, S. Accuracy improvement of semantic segmentation using appropriate datasets for robot navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Paris, France, 23–26 April 2019; pp. 1610–1615. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2881–2890. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavian, A.; Toshev, A.; Fišer, M.; Košecká, J.; Wahid, A.; Davidson, J. Visual representations for semantic target driven navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 8846–8852. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Lu, H. Real-time people counting for indoor scenes. Signal Process. 2016, 124, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, E.; Garcia-Silvente, M.; Plata, J. Leg Detection and Tracking for a Mobile Robot and Based on a Laser Device, Supervised Learning and Particle Filtering. In ROBOT2013: First Iberian Robotics Conference; Armada, M.A., Sanfeliu, A., Ferre, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 252, pp. 433–440. [Google Scholar]

- Monroy, J.; Ruiz-Sarmiento, J.; Moreno, F.; Galindo, C.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, J. Olfaction, Vision, and Semantics for Mobile Robots. Results of the IRO Project. Sensors 2019, 19, 3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostavelis, I.; Gasteratos, A. Learning spatially semantic representations for cognitive robot navigation. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1460–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouilly, R.; Rives, P.; Morisset, B. Semantic Representation For Navigation In Large-Scale Environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, ICRA’15, Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, J.; Thakur, D.; Dames, P.; Phillips, C.; Kientz, T.; Daniilidis, K.; Bergstrom, J.; Kumar, V. An automated system for semantic object labeling with soft object recognition and dynamic programming segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Gothenburg, Sweden, 24–28 August 2015; pp. 683–690. [Google Scholar]

- Rituerto, J.; Murillo, A.C.; Košecka, J. Label propagation in videos indoors with an incremental non-parametric model update. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–30 September 2011; pp. 2383–2389. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Kodagoda, S.; Dissanayake, G. Multi-class classification for semantic labeling of places. In Proceedings of the 2010 11th International Conference on Control Automation Robotics & Vision (ICARCV), Singapore, 7–10 December 2010; pp. 2307–2312. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, G. SIFT—The scale invariant feature transform. Int. J. 2004, 2, 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Polastro, R.; Corrêa, F.; Cozman, F.; Okamoto, J., Jr. Semantic mapping with a probabilistic description logic. In Advances in Artificial Intelligence—SBIA 2010; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, A.C.; Gomez, C.; Barber, R. MiNERVA: Toposemantic Navigation Model based on Visual Information for Indoor Enviroments. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Huo, G.; Li, R.; Hou, Z.; Luo, P.; Sun, Z.; Wang, K.; Yang, C. Visual semantic navigation based on deep learning for indoor mobile robots. Complexity 2018, 2018, 1627185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozos, O.M.; Triebel, R.; Jensfelt, P.; Rottmann, A.; Burgard, W. Supervised semantic labeling of places using information extracted from sensor data. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2007, 55, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, P.; Araujo, R.; Nunes, U. Real-time labeling of places using support vector machines. In Proceedings of the ISIE 2007—IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics, Vigo, Spain, 4–7 June 2007; pp. 2022–2027. [Google Scholar]

- Pronobis, A.; Martinez Mozos, O.; Caputo, B.; Jensfelt, P. Multi-modal Semantic Place Classification. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2010, 29, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozos, O.M.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. Supervised learning of places from range data using adaboost. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation—ICRA 2005, Barcelona, Spain, 18–22 April 2005; pp. 1730–1735. [Google Scholar]

- Rottmann, A.; Mozos, O.M.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. Semantic Place Classification of Indoor Environments With Mobile Robots using Boosting. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 9–13 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Charalampous, K.; Kostavelis, I.; Gasteratos, A. Recent trends in social aware robot navigation: A survey. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2017, 93, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.C.; Behnke, S. Learning depth-sensitive conditional random fields for semantic segmentation of RGB-D images. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 6232–6237. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, D.; Prankl, J.; Vincze, M. Fast semantic segmentation of 3D point clouds using a dense CRF with learned parameters. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 4867–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Gómez, D.; Mayol-Cuevas, W.; Guerrero, J.J. What should I landmark? Entropy of normals in depth juts for place recognition in changing environments using RGB-D data. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 5468–5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, A.; Floros, G.; Leibe, B. Dense 3D semantic mapping of indoor scenes from RGB-D images. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 2631–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, A. PLISS: Labeling places using online changepoint detection. Auton. Robot. 2012, 32, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez-López, D.; Tardos, J.D. Bags of Binary Words for Fast Place Recognition in Image Sequences. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2012, 28, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffra, F.; Chen, Z.; Chli, M. Tolerant place recognition combining 2D and 3D information for UAV navigation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 2542–2549. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.V.; Hershberger, D.; Smart, W.D. Layered costmaps for context-sensitive navigation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014; pp. 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.L.; Kaelbling, L.P.; Lozano-Perez, T. Not Seeing is Also Believing: Combining Object and Metric Spatial Information. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, X. Semantic Mapping for Object Category and Structural Class. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Deeken, H.; Wiemann, T.; Lingemann, K.; Hertzberg, J. SEMAP—A semantic environment mapping framework. In Proceedings of the 2015 European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR), Lincoln, UK, 2–4 September 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.R.; Hemachandra, S.; Homberg, B.; Tellex, S.; Teller, S. Learning Semantic Maps from Natural Language Descriptions. In Proceedings of the 2013 Robotics: Science and Systems IX Conference, Berlin, Germany, 24–28 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hemachandra, S.; Walter, M.R. Information-theoretic dialog to improve spatial-semantic representations. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015; pp. 5115–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.W.; Yi, C.; Suh, I.H. Semantic mapping and navigation: A Bayesian approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Patel-Schneider, P.; Abrtahams, M.; Alperin, L.; McGuinness, D.; Borgida, A. NeoClassic Reference Manual: Version 1.0; Technical Report; AT&T Labs Research, Artificial Intelligence Principles Research Department: Florham Park, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, J. Arquitectura y Diseno de un Sistema Completo de Navegacion Semantica. Descripcion de su Ontologia y Gestion de Conocimiento. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Sarmiento, J.R.; Galindo, C.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, J. Building Multiversal Semantic Maps for Mobile Robot Operation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2017, 119, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uschold, M.; Gruninger, M. Ontologies: Principles, methods and applications. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 1996, 11, 93–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, C.; Fernández-Madrigal, J.A.; González, J.; Saffiotti, A. Robot task planning using semantic Maps. Robot. Auton. Sist. 2008, 56, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, C.; Saffiotti, A. Inferring robot goals from violations of semantic knowledge. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nüchter, A.; Hertzberg, J. Towards semantic maps for mobile robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2008, 56, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorth, M.; Kunze, L.; Jain, D.; Beetz, M. KNOWROB-MAP—Knowledge-Linked Semantic Object Maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots, Nashville, TN, USA, 6–8 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grisetti, G.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. Improved techniques for grid mapping with Rao-Blackwellized particle filters. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2007, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeson, P.; Jong, N.K.; Kuipers, B. Towards autonomous topological place detection using the extended voronoi graph. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Barcelona, Spain, 18–22 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Prestes, E.; Carbonera, J.L.; Fiorini, S.R.; Jorge, V.A.; Abel, M.; Madhavan, R.; Locoro, A.; Goncalves, P.E.; Barreto, M.; Habib, M.; et al. Towards a Core Ontology for Robotics and Automation. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, R.; Benjamins, V.; Fensel, D. Knowledge engineering: Principles and methods. Data Knowl. Eng. 1998, 25, 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, N. Formal Ontology and Information Systems. In Proceedings of the First International Conference On Formal Ontology In Information Systems, Trento, Italy, 6–8 June 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Pérez, A.; Fernández-López, M.; Corcho, O. Ontological Engineering: With Examples from the Areas of Knowledge Management, e-Commerce and the Semantic Web. (Advanced Information and Knowledge Processing); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan, S.; Gächter, S.; Nguyen, V.; Siegwart, R. Cognitive maps for mobile robots—An object based approach. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2007, 55, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milford, M.; Wyeth, G. Mapping a suburb with a single camera using a biologically inspired slam system. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2008, 24, 1038–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, V.A.; Tian, B.; Yuan, M.; Tang, H.; Li, H. Direction-driven navigation using cognitive map for mobile robots. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014; pp. 2639–2646. [Google Scholar]

- Rebai, K.; Azouaoui, O.; Achour, N. Bio-inspired visual memory for robot cognitive map building and scene recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 2985–2990. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, G.A.; Grossberg, S.; Rosen, D.B. Fuzzy ART: Fast Stable Learning and Categorization of Analog Patterns by an Adaptive Resonance System. Neural Netw. 1991, 4, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, I.; Nourbakhsh, I. Appearance-Based Place Recognition for Topological Localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–28 April 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Siagian, C.; Itti, L. Biologically inspired mobile robot vision localization. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2009, 25, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Tian, G.H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, F.y.; Duan, P. Spatial semantic hybrid map building and application of mobile service robot. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2014, 62, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.; González, J.; Fernández-Madrigal, J.A. Subjective local maps for hybrid metric-topological SLAM. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2009, 57, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, D.; Ao, H.; Belaroussi, R.; Gruyer, D. Fast 3D Semantic Mapping in Road Scenes. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, L.; Blumenthal, S.; Huebel, N.; Bruyninckx, H.; Prassler, E. Semantic mapping extension for OpenStreetMap applied to indoor robot navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 3839–3845. [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers, B. The Spatial Semantic Hierarchy. Artif. Intell. 2000, 119, 191–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeson, P.; MacMahon, M.; Modayil, J.; Murarka, A.; Kuipers, B.; Stankiewicz, B. Integrating Multiple Representations of Spatial Knowledge for Mapping, Navigation, and Communication; Interaction Challenges for Intelligent Assistants: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, A.; Coupe, P. Distorsions in Judged Spatial Relations. Cogn. Psychol. 1978, 10, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNamara, T. Mental Representations of Spatial Relations. Cogn. Psychol. 1986, 18, 87–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. How shall a thing be called? Psychol. Rev. 1958, 65, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosch, E. Cognition and Categorization; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, J.; Barber, R.; Mozos, O.M. An Inferring Semantic System Based on Relational Models for Mobile Robotics. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Autonomous Robot Systems and Competitions (ICARSC), Vila Real, Portugal, 8–10 April 2015; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N.; Yang, E.; Corney, J. Semantic path planning for indoor navigation and household tasks. In Proceedings of the 20th Towards Autonomous Robotic Systems Conference (TAROS 2019), London, UK, 3–5 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moravec, H. Sensor fusion in certainty grids for mobile robots. AI Mag. 1988, 9, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kostavelis, I.; Charalampous, K.; Gasteratos, A.; Tsotsos, J.K. Robot navigation via spatial and temporal coherent semantic maps. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2016, 48, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Farhadi, A.; Gupta, A.; Mottaghi, R. Visual Semantic Navigation using Scene Priors. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.06543. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR’2017), Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik, S. Robot Cognition and Navigation: An Experiment with Mobile Robots (Cognitive Technologies); Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- de Lucca Siqueira, F.; Plentz, P.D.M.; Pieri, E.R.D. Semantic trajectory applied to the navigation of autonomous mobile robots. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACS 13th International Conference of Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), Agadir, Morocco, 29 November–2 December 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.; Parker, L.; Antonelli, G.; Caccavale, F. Behavioral control for multi-robot perimeter patrol: A Finite State Automata approach. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; pp. 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, Q. Route natural language processing method for robot navigation. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Information and Automation (ICIA), Ningbo, China, 1–3 August 2016; pp. 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, B.; Lam, O.; Schulz, R.; Dayoub, F.; Upcroft, B.; Wyeth, G. Find my office: Navigating real space from semantic descriptions. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Stockholm, Sweden, 16–21 May 2016; pp. 5782–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aotani, Y.; Ienaga, T.; Machinaka, N.; Sadakuni, Y.; Yamazaki, R.; Hosoda, Y.; Sawahashi, R.; Kuroda, Y. Development of Autonomous Navigation System Using 3D Map with Geometric and Semantic Information. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2017, 29, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.; Guedea, F.; Karray, F.; Dai, Y.; El Khalil, I. Natural language interface for mobile robot navigation control. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Symposium on Intelligent Control, Taipei, Taiwan, 4 September 2004; pp. 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- Druzhkov, P.N.; Kustikova, V.D. A survey of deep learning methods and software tools for image classification and object detection. Pattern Recognit. Image Anal. 2016, 26, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, X.; Fieguth, P.W.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Pietikäinen, M. Deep Learning for Generic Object Detection: A Survey. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.02165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).