Abstract

As the number of Internet of Things (IoT) devices connected to the network rapidly increases, network attacks such as flooding and Denial of Service (DoS) are also increasing. These attacks cause network disruption and denial of service to IoT devices. However, a large number of heterogenous devices deployed in the IoT environment make it difficult to detect IoT attacks using traditional rule-based security solutions. It is challenging to develop optimal security models for each type of the device. Machine learning (ML) is an alternative technique that allows one to develop optimal security models based on empirical data from each device. We employ the ML technique for IoT attack detection. We focus on botnet attacks targeting various IoT devices and develop ML-based models for each type of device. We use the N-BaIoT dataset generated by injecting botnet attacks (Bashlite and Mirai) into various types of IoT devices, including a Doorbell, Baby Monitor, Security Camera, and Webcam. We develop a botnet detection model for each device using numerous ML models, including deep learning (DL) models. We then analyze the effective models with a high detection F1-score by carrying out multiclass classification, as well as binary classification, for each model.

1. Introduction

At the 2016 World Economic Forum (WEF, also known as the Davos Forum), The Fourth Industrial Revolution by Klaus Schwab became a turning point in transforming our society from an information society into an intelligent information society. The Fourth Industrial Revolution represents a fundamental change in the way we live, work, and relate to one another [1]. Key technologies leading the fourth industrial revolution include the Internet of Things (IoT), the cloud, big data, mobile technology, and artificial intelligence (AI). These intelligent information technologies are creating new industries and revolutionizing the ecosystem of existing manufacturing industries. The term “Internet of Things” was coined in 1999 by Kevin Ashton to describe how data collection through sensor technology has unlimited potential [2]. With the inclusion of the IoT in the Gartner Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends in 2020, it was shown that the IoT will develop into more than 20 times more smart devices than existing IT roles in 2023 [3]. According to Gartner, the overall usage of IoT in various areas, such as utilities, healthcare, the government, physical security, and vehicles, is expected to increase [4].

As the IoT develops, cyber threats targeting IoT devices are also increasing. Most IoT devices are connected to the internet, which facilitates abuse and a lack of security control. The fact that IoT manufacturers failed to implement proper security controls to protect these types of devices from remote attacks allowed the number of IoT attacks to increase during last year by 217.5%, up from the 10.3 million attacks logged by SonicWall in 2017, according to its 2019 Cyber Threat Report [5].

There are many security threats targeting the IoT, which has many vulnerabilities. Because the IoT is subject to many threats, it is important to classify the relevant vulnerabilities and attacks in order to study the IoT. Some studies classify such attacks based on the IoT layer [6,7], the attacks themselves [8,9,10], and the vulnerabilities that can lead to the attack [11,12,13]. Through these studies, we found that jamming, DoS, man in the middle, routing, sinkhole, wormhole, flooding, virus, and worm attacks are the most likely to occur in an IoT environment. In particular, flooding and DoS attacks occur in production IoT environments through botnets.

Botnet attacks [14,15,16], according to Owari, Mirai, and Bashlite, are especially surging in popularity. A botnet runs a bot on several devices connected to the internet to form a botnet controlled by the command and control (C&C) [17]. The botnet causes various types of damage, such as resource depletion and service disruption. AI is now widely used to detect these IoT attacks [18,19,20,21].

Currently, the IoT is attacked through various channels and methods. However, it is difficult to introduce security solutions and determine instances of hacking on the IoT through an analysis of security threats using network information. There are many recent security issues related to the IoT, which have increased awareness of such problems. Currently, research on IoT security threats is focused on analyzing and responding to networks [22,23], but there are limitations that preclude detecting direct changes in hardware. Thus, unlike previous studies, we focused on attacks targeting IoT devices. In particular, we used deep learning and machine learning algorithms to detect such attacks efficiently.

The remainder of this paper is organized as it follows. We briefly review the trends of IoT security threats and deep learning studies used in IoT security in Section 2. We design an IoT attack detection model based on five ML algorithms and three DL algorithms in Section 3 and Section 4. Finally, the conclusions are presented in Section 5.

2. Related Works

2.1. IoT Security Threats

As the IoT evolves, attacks on the IoT and using IoT are becoming more diverse. This section describes IoT security threats. First, we look at studies that categorized IoT security threats. Next, we explore the types of IoT security attacks and the papers that studied those attacks.

2.1.1. Classification of Attacks

The classification that categorizes attacks can be largely divided into three groups. One is divided based on the layers of the IoT. Another includes independently suggested classifications based on attacks, while the other is based on the attacks themselves. In this section, the classification presented in each study is divided into these three groups.

- IoT layer:

The IoT can be divided into three layers: the perception layer, the network layer, and the application layer. The perception layer is the bottom layer of the IoT, which connects physical devices to the network. The network layer is the layer in the middle of the IoT that determines the route based on information received from the perception layer. The application layer is the top layer of the IoT. It receives data from the network layer and sends it to the appropriate service. The potential attacks on each layer can be explained according to this taxonomy based on IoT layers. Lin et al. [6] classified the security challenges that can occur on each layer of the IoT. Sonar et al. [7] focused on DDoS attacks that can occur in the IoT. They categorized the DDoS scenarios that can occur in each layer of the IoT.

- Attacks:

Abomhara et al. [8] classifies attacks into eight common attack types: physical attacks, reconnaissance attacks, DoS, access attacks, attacks on privacy, cyber-crimes, destructive attacks, and supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) attacks. Physical attacks are attacks related to hardware components. Reconnaissance attacks involve the mapping of unauthorized systems or services using packet sniffers or scanning network ports. DoS is an attack that disables network resources or devices. Access attacks are attacks that allow unauthorized users to gain access to a network or device. Attacks on privacy involve privacy protection. Cyber-crimes involve using Internet or smart devices to take user data to commit a crime. Destructive attacks are attacks that harms assets and lives (e.g., terrorism). SCADA systems are vulnerable to many cyber-attacks; such a system can be attacked using DoS, a Trojan, or a virus. Andrea et al. [9] divided attacks into four categories based on the type of attack: physical attacks, network attacks, software attacks, and encryption attacks. Deogirikar et al. [10] used this taxonomy.

- Vulnerabilities:

Neshenko et al. [11] categorized the many IoT-related studies from 2005 to 2018 into five classes: layers, security impacts, attacks, countermeasures, and situational awareness capability (SAC). Layers is a class that determines how IoT components affect IoT vulnerabilities. Security impact is a class that represents vulnerabilities based on security elements such as confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Attacks describes IoT vulnerabilities that can be exploited. Countermeasures is a class for countermeasures that can improve IoT weaknesses. SAC is a class of technology used for malicious activities using the IoT. Ronen et al. [12] presented a new classification standard divided into four different categories depending on how the attackers deviated from the specific functions of the IoT. The four categories are ignoring functionality, reducing functionality, misusing functionality, and extending functionality. Ignoring functionality is an attack that ignores the intended physical function of the IoT and considers the IoT device as a normal computer device that is connected to the internet. Reducing functionality involves limiting or eliminating the original functions of the IoT. Misusing functionality entails using a function in an incorrect or unauthenticated way without destruction. Extending functionality means expanding a given function to produce different or unexpected physical effects. Alaba et al. [13] presented four groups of classification: application, architecture, communication, and data. Table 1 provides a summary of classification research presented in Section 2.1.1.

Table 1.

Summary of classification works.

2.1.2. Attack Works

By reviewing the various classifications used in each study in Section 2.1.1, we decided to use IoT layer classification to categorize the possible attacks on the IoT. Based on the aforementioned IoT layers, the most frequently mentioned attacks can be divided into nine types of attacks. We organize these nine types of attacks into the proposed taxonomy and see if they violate the three elements of information protection: confidentiality, integrity, and availability. We also look at studies related to each attack.

- Perception:

The Perception class includes attacks that usually deplete the resource of the devices.

Jamming: A jamming attack is an attack that interferes with the radio frequency of the sensor node. Integrity is violated here because the device’s frequency is changed. When someone cannot obtain service due to a jamming attack, availability is also violated. Namvar et al. [24] presented a mechanism that can solve a Jamming probe in an IoT system. Dou et al. [25] proposed an ACA model that provides adequate resources for anti-jamming on the IoT. Through simulation, they showed that the model is suitable for low-power, band-limited IoT networks.

DoS: A DoS attack is an attack that consumes all available resources and causes the IoT system to function abnormally. Here, availability is violated. DDoS is an attack in which many attackers from many points attack one target using a very large network. When carrying out a DDoS attack, the malicious code that allows an attacker to carry out an attack is called a bot. A botnet that carries out a DDoS attack consists of these bots. Angrishi et al. [26] referred the structures of IoT botnets and introduced DDoS events using IoT botnets. The authors also presented improved measurements that can alleviate the risks related to the IoT. Kolias et al. [27] described botnets that can trigger DDoS attacks. They focused on the Mirai botnet and also mentioned other botnets, such as Hajime and BrickerBot.

- Network:

The Network class mainly categorizes attacks that send or receive incorrect information or deplete network resources so that the user cannot obtain normal service.

Man in the middle attack (MitM): A MitM attack is made by a malicious device inserted by an attacker between two normal devices that are communicating in an IoT network environment. Data can be stolen or stored on the malicious device. Integrity is violated in this case because the data can be changed. Because the unauthorized person is in the middle, it can also be said that confidence is violated. Li et al. [28] demonstrated the weakness of the OpenFlow control channel by conducting an experiment based on an MitM attack. The authors also suggested a countermeasure called Bloom filters and indicated the efficiency of the Bloom filter monitoring system. Cekerevac et al. [29] showed a variety of attacks using MitM, including MIT-Cloud (MITC), MIT-Browser (MITB), and MIT-mobile (MITMO). They showed that MitM is not uncommon and can damage the IoT, even though it is an old attack.

Routing attack: A routing attack is an attack based on the routing protocol of the IoT system. It causes a delay in the IoT network by creating a routing loop that manipulates routing. Integrity is violated because information can be manipulated. Wallgren et al. [30] presented several well-known routing attacks and emphasized the importance of security in routing protocol low power and lossy networks (RPL)-based IoT. Yavuz et al. [31] presented a deep learning-based machine learning method that can detect IoT routing attacks with high accuracy by determining the attack detection method based on deep learning.

Sinkhole: A sinkhole attack occurs when an abnormal device makes an exceptional request that is forwarded to another abnormal device. By requiring two abnormal devices continuously, confidentiality is compromised. Shiranzaei et al. [32] proposed an intrusion detection system (IDS) that can defend a 6LowPAN network from a sinkhole or forwarding attack. Soni et al. [33] explored the trends in the countermeasure technology against sinkhole attacks.

Wormhole: A wormhole is an attack that can occur when two malicious devices exchange routing information over a private link so that other devices think that there is only one hop between the two. When someone is present in the middle, it can be said that confidentiality is violated. Integrity can also be violated when other devices have the wrong information due to a wormhole attack. Palacharla et al. [34] examined various mechanisms for detecting wormholes and suggested new methods. The proposed method uses cryptography to detect a wormhole attack. Because the path is dynamically checked, the transfer between the two can be detected without looking at all the nodes. Lee et al. [35] studied the effects of wormhole attacks on network flow and proposed a passivity-based control-theoretical framework to model a wormhole attack.

Flooding: Flooding is a type of DoS attack. DoS can exhaust not only perception resources but also network resources in the IoT environment. Flooding depletes bandwidth by sending massive or abnormal traffic and results in service disruption at the network layer. Availability is violated because users cannot obtain a connection when desired. Rizal et al. [36] conducted network forensic research that can detect IoT flooding attacks. The authors proposed a network forensics model and successfully detected attacks. Campus et al. [37] described how flooding attacks affect routing on the IoT.

- Application:

The application class classifies attacks that can occur on the application side.

Virus: A virus is cloned and infected but is not propagated by itself. Confidentiality, integrity, and availability are all violated by a virus. Because information can be given to an unauthorized user, data can be changed and made unavailable to an authorized user. Azmoodeh et al. [38] proposed a machine learning-based approach to detect ransomware attacks, which are a type of virus. Dash et al. [39] used network traffic flow analysis to access ransomware. They showed that machine learning is a very efficient approach to detect ransomware.

Worm: Unlike a virus, a worm can spread itself. When someone destroys their victim with a worm, integrity is violated. When service is denied due to a worm, availability is violated. Wang et al. [40] proposed a new worm detection method based on mining dynamic program execution. The authors showed that the proposed method has high detection and low detection rates. Yu et al. [41] studied a new type of worm called a self-disciplinary worm. This worm changes its breeding patterns to become less detectable and allow more computers to become infected. The authors used a game-theoretic formulation to propose the corresponding countermeasures. Table 2 shows a summary of these attacks and their relevant research.

Table 2.

Summary of attacks.

2.2. Existing AI-Based IoT Studies

Next, we briefly review the trends of IoT studies based on deep learning and machine learning.

2.2.1. IoT Using AI

Mohammed et al. [42] suggested that basic deep learning could provide services like image recognition, voice recognition, localization, detection, and security. The authors summarized the areas in which the IoT is used and what studies have been done in each area. Xiaofeng et al. [43] showed how data are collected through smart cities, sensors, and humans. They suggested using anomaly detection model-based machine learning with annual power data, loops, and land sensor data. They used long short-term memory-neural network (LSTM-NN) and MLP models. Among the models, LSTM-G-NB has the highest accuracy. Furqan Alam et al. [44] suggested a classifier based on eight algorithms such as support vector machine (SVM), K-nearest neighbor (KNN), naïve Bayes (NB), latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) using IoT device data. NB and LDA offer better accuracy, while LDA provides quicker processing speed. The DLANN algorithm requires the longest time because it features a complex structure and requires many system resources. Mohammadi et al. [45] also applied deep learning and machine learning to the IoT. They introduced the concepts of security threats and artificial intelligence techniques in many fields. In particular, 60% of devices in healthcare are considered Internet of Medical Things (IoMT), which is expected to grow to 20 to 30 billion devices in 2020.

2.2.2. IoT Security Using AI

- Malware Classifier:

As IoT malware is widespread and a major source of DDoS traffic, IoT security has become increasingly more important. Since most IoT devices have no existing mechanism to automatically update themselves, malware detection in the network layer is necessary [46]. Hamed et al. [47] studied Advanced RISC Machine (ARM)-based IoT applications. The dataset used in their study includes 280 examples of 32-bit malicious code based on ARM and 271 examples of benign data. They used the object dump tool to decompile all samples and abstract the sequences of the opcodes. The final output vector consisted of 681 possible opcode indices. To test the LSTM classifier, the authors used 100 examples of malware data not used in model training. The proposed model offered 97% average accuracy.

- Network Anomaly Detection:

Network malware detection has also been studied. Mcdermott et al. [18] proposed a description of deep learning and a network botnet attack detection model based on deep learning. The Mirai botnet was used in this study. The authors proposed a detection model based on bidirectional long short-term memory (BLSTM) using a recurrent neural network (RNN) that consists of an Adam optimizer and a sigmoid function. With the dataset made by capturing packets, the model-based LSTM provided 99.571% accuracy, and the model–based BLSTM offered 99.998% accuracy. Olivier et al. [19] suggested an attack detection model based on Dense RNN. This model can detect UDP flooding, TCP SYN flooding, sleep deprivation attacks, barrage attacks, and broadcast attacks. Captured packets extract statistical sequence data. In the study, the gateway was connected to the Internet via 3G SIM cards. Several IoT devices and Wi-Fi connections were also connected to the gateway. The proposed model showed similar performance to the threshold method. Yair et al. [20] used packet-captured data with port mirroring in a network including IoT devices. The IoT devices used in the study were of nine types: a baby monitor, motion sensor, refrigerator, security camera, smoke detector, socket, thermostat, TV, and a watch. They introduced unauthorized IoT device classifier model-based random forest learning. On average, the model shows an accuracy of 94% and has higher accuracy than the white list method. This study shows the same result with network changes. Doshi et al. [21] suggested a DoS attack traffic detection model for IoT devices. They used KNN, Lagrangian support vector machine (LSVM), decision tree (DT), random forest (RF), and neural network (NN) for model training. The dataset was generated with captured packets and grouped by device and time zone. The extracted features were divided into stateless and stateful features. The stateless category includes packet size, the inter-packet interval, and the protocol features. The stateful category includes bandwidth and destination IP address cardinality and novelty features. As a result, using all features was more accurate than using only stateless features. Hodo et al. [48] described the characteristics of host-based IDS and network-based IDS. They suggested using a DDoS/DoS attack detection model using ANN. The proposed model provided 99.4% accuracy.

- Network Anomaly Detection using N-BaIoT:

Meidan et al. [49] used the N-BaIoT dataset, which is described in Section 3. The authors proposed an anomaly detection model based on a deep autoencoder. They separated the model for each IoT device and user datum during training. After training, the anomaly threshold was set. The Mirai and Bashlite botnet environments were built and used. The proposed model was compared to the local outlier factor (LOF), one-class SVM, and isolation forest. The proposed model provided the best performance of the four models. Shorman et al. [50] proposed an IoT botnet detection model. The authors used data pfreprocessing in four levels: data cleaning, data migration, and data rescaling and optimizing. With pre-processed N-BaIoT, the authors trained the intrusion detection model based on the Grey Wolf optimization one-class support vector machine (GWO-OCSVM) algorithm. Compared to OCSVM, isolation forest (IF), and LOF, the proposed model provides a faster detection time and higher accuracy. Table 3 shows a summary of Section 2.2 (i.e., which dataset(s) and algorithm(s) are used in each reference).

Table 3.

Dataset(s) and algorithm(s) used in each reference.

3. Methodology

We built a framework for developing an IoT botnet detection model. Our framework includes the entire process from defining the botnet dataset to detecting botnets. In this section, we describe the N-BaIoT dataset used in our framework and design the proposed framework.

3.1. N-BaIoT Dataset

The N-BaIoT dataset was generated by Mohammed et al. [42] and consists of data samples with 115 features. The datasets were collected through the port mirroring of IoT devices. The benign data were captured immediately after setting the network to ensure that the data was benign. For two types of packet sizes (only outbound/both outbound and inbound), packet counts, and packet jitters, the times between packet arrival were extracted for each statistical value. A total of 23 features were extracted for each of the 5 time windows (100 ms, 500 ms, 1.5 s, 10 s, and 1 min), for a total of 115 features. We use all of the 115 features in our framework. Table 4 shows the detailed features of the dataset.

Table 4.

Detailed features of the N-BaIoT dataset.

The datasets were collected by injecting two types of attacks into various types of IoT devices, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Specific device type and model name in the N-BaIoT dataset.

Each dataset was generated by injecting various Bashlite and Mirai attacks. Bashlite, also known as gafgyt, was written by Lizard Squad in C. This botnet is used for DDoS attacks by infecting Linux-based IoT devices. Various types of flooding attacks are used, such as UDP and TCP attacks. Mirai, which was written by Paras, is used for large-scale attacks using IoT devices. Mirai was discovered in August 2016. Since 2016, the botnets have evolved significantly and have become more proficient [51,52]. Mirai is now available as open source [53]. Bastos et al. [54] suggested a framework to identify Mirai and Bashlite C&C servers by combining 4 heuristic algorithms. Table 6 shows the 10 specific attack types of Bashlite and Mirai.

Table 6.

Botnet and attack types used in this study.

3.2. Proposed Framework

Our framework comprises a botnet dataset, botnet training models, and botnet detection models. The botnet dataset consists of four subdatasets of N-BaIoT. We select devices that include all 10 attack samples described in Table 6 in the N-BaIoT, such as a doorbell (Ennio), baby monitor (Philips B120N/10), security camera (Provision PT-838), and webcam (Samsung SNH 1011 N). Table 7 shows the number of samples in the four datasets according to the device type we used.

Table 7.

Number of samples used in this paper.

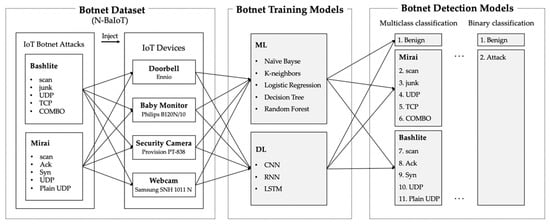

As botnet training models, we use most widely used ML and DL algorithms. We employed not only five types of ML models (naïve Bayes (NB), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), logistic regression (LR), decision tree (DT), and random forest (RF)) but also three types of DL models (convolutional neural network (CNN), recurrent neural network (RNN), and long short-term memory (LSTM)). There are two types of botnet detection models: binary classification and multiclass classification. The binary classification classifies the N-BaIoT dataset into two categories: attack and benign. This classification does not consider different types of protocols that can be used for botnet attacks, while the multiclass classification distinguishes each of protocol used for the Bashlite and Mirai. Figure 1 shows our framework for developing ML- and DL-based IoT botnet detection models.

Figure 1.

Our proposed framework for IoT botnet detection.

4. Experimental Evaluation

In this Section, we find out the most effective model for IoT botnet detection by analyzing performance differences depending on the type of IoT devices as well as the type of ML and DL models. We first develop an IoT botnet detection model based on the proposed framework. Among the samples of the N-BaIoT dataset, we randomly divide the training and testing samples by 70 to 30 using a dataset split function of Scikit-learn, an open source ML library for supervised and unsupervised learning, so the training and testing sets are independent each other. In order to prevent overfitting, furthermore, we use 20%of the training set as a validation set. We calculate the validation loss during training to monitor whether the validation loss does not increase while the training loss decreases.

In this section, we carry out multiclass classification as well as binary classification. Multiclass classification classifies not only benign but also fine grains of attacks by learning them, while binary classification categorizes N-BaIoT only into benign and attack. We then verify our ML and DL models using the testing sets.

4.1. Binary Classification

The binary classification model considers 10 different detailed Bashlite and Mirai attacks injected into IoT devices as one attack. It also distinguishes between attack or benign states, the latter of which means that the attack is not injected. We train our model using the dataset collected from each device based on the ML and DL models. We design these models using Keras, as well as Scikit-learn. Table 8 describes the design of our models.

Table 8.

Design of our ML and DL models.

We then analyze the performance of the models through their F1-score measurements. The F-score is an index expressed as a single value considering both precision and recall, and the F1-score is the value that is given a weighted beta value of 1 for precision when calculating the F-score. The F1-score can be expressed by the following equation:

where

True positive (TP) is the number of samples that are properly classified as benign. False negative (FN) is the number of samples that falsely detect benign data as a botnet. False Positive (FP) refers to a sample that incorrectly predicts an actual botnet as benign. A True Negative (TN) indicates the number of samples that are properly detected as a botnet. Table 9 shows the detailed detection results of precision, recall, and F1-score for each ML model.

Table 9.

Detection results of the five ML models.

In Table 9, all models except logistic regression (LR) are able to classify benign and botnet samples with very high performance. For LR, the precision, recall, and F1-score of benign samples are significantly lower than that of attack on all the devices. Thus, errors occur frequently in benign classification.

In addition, the naïve Bayes (NB) classification in Table 9 corresponds to multinomial NB, which has the best performance out of Gaussian NB, Bernoulli NB, and multinomial NB. As shown in Table 10, Gaussian and Bernoulli NB have a lower detection F1-score than multinomial NB. Therefore, we also used multinomial NB for multi-classification because multinomial NB provides high detection F1-score.

Table 10.

Detection F1-score of each naïve Bayes on 4 different devices.

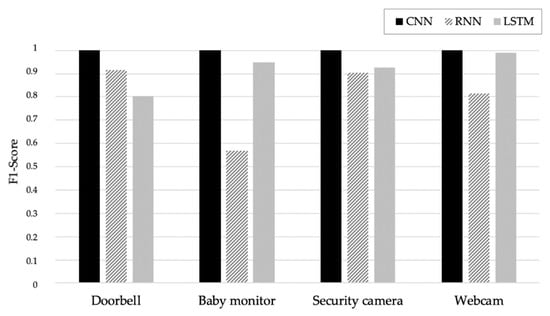

Figure 2 shows the results of binary classification based on the three DL models. It can be seen that the CNN model has more than 0.99 F1-score on all devices and offers higher performance than the RNN and LSTM models. LSTM, which has the second highest performance, yields more than 0.99 F1-score for the baby monitor, security camera, and webcam, but only 80% for the doorbell. In the doorbell results, all botnets were accurately detected (except for 2) out of 290,000 botnet samples. However, for benign samples, 5000 samples (comprising about 61% of the 15,000 samples) were incorrectly detected as botnets. This is because the number of benign samples for learning was significantly less than the number of botnet samples, thereby producing several false positive with a benign classification. Using RNN, the F1-score was 0.57 for the baby monitor, about 0.815 for the webcam, and 0.905 for the doorbell and security camera, thus offering the lowest average F1-score compared to CNN and LSTM. Notably, the RNN result for the baby monitor showed high F1-score in benign classification, but about 80% of the samples incorrectly classified the botnet samples as benign during botnet detection. In Section 4.2, using the results of multiclass classification, we determine what specific botnet attacks provide the highest false positive rates.

Figure 2.

Result of binary classification based on the three DL models.

4.2. Multiclass Classification

The multiclass classification model considers 10 attacks injected into each device as individual attacks and classifies them into 11 groups, including benign. The F1-score of each model as a result of training each device dataset using the five ML models and performing multiple classifications is shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

F1-score of each model based on the ML model.

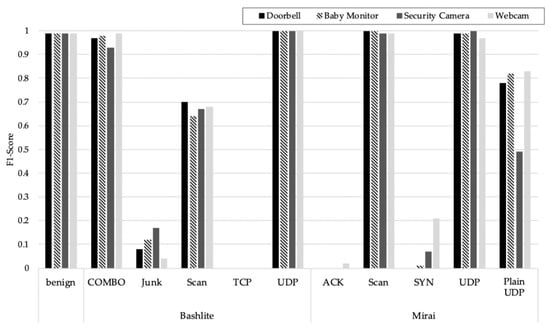

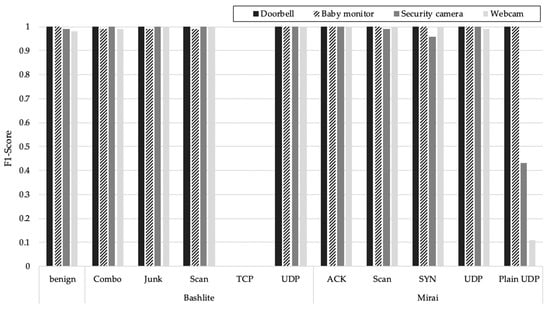

Compared to the binary classification in Table 8, DT and RF still provide F1-score closes to 1 for all devices, but NB and KNN show lower F1-scores. To determine why the F1-scores decreased in the NB model, the results of analyzing the F1-scores by attack type are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The F1-score of each attack type in naïve Bayes-based model.

As shown in Figure 3, for NB based botnet detection under Bashlite attacks, junk, scan, and TCP detection have low F1-score, and for Mirai attacks, ACK, SYN, and Plain UDP detection show low F1-score. This occurs because, as shown in Table 12, the Junk of Bashlite was mis-detected as a COMBO (SYN+UDP) of Bashlite, the scan of Bashlite was mis-detected as a scan of Mirai, and the TCP of Bashlite was mis-detected as the UDP of Bashlite. There were also several samples that were mis-detected as the UDP of Mirai from the ACK of Mirai and as a COMBO of Bashlite or a scan of Mirai from the SYN of Mirai and the UDP of Mirai from the Plain UDP of Mirai.

Table 12.

Detailed results of the naïve Bayes-based botnet detection.

In KNN-based detection, the F1-score was universally high for Bashlite attacks, as shown in Figure 4, but in the case of the Mirai attack, the F1-score was always about 0.7 to 0.9, except for scan.

Figure 4.

The F1-score of each attack type in the KNN-based model.

Detection results by attack type, as shown in Table 13. The ACK of Mirai was mis-detected as UDP of Mirai, the SYN of Mirai was mis-detected as a COMBO of Bashlite and a scan of Mirai, and the UDP of Mirai was mis-detected as a Plain UDP of Mirai. Because of this, false positives occurred frequently.

Table 13.

Detailed results of the KNN-based botnet detection.

The average F1-score of each model as a result of training the dataset for each device using the three DL models and performing multiple classification is shown in Table 14. According to Table 14, CNN has the highest F1-score. Compared to CNN, RNN and LSTM have lower F1-score.

Table 14.

Average F1-score of the DL models.

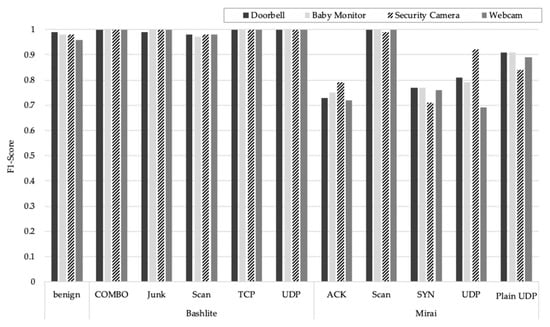

For the CNN, although most of the detailed attacks were accurately detected, the detection F1-score for the TCP attack of Bashlite was 0%, as shown in Figure 5. According to the confusion matrix results (which is the table showing whether the class predicted by the model matches the original class of the target), the CNN model consistently detected the TCP attack of Bashlite as a UDP attack of Bashlite on all devices. In addition, for the security camera and webcam, the model detected the Plain UDP attack of Mirai as a UDP attack of Mirai. The model also mis-detected the ACK and scan of Mirai.

Figure 5.

F1-score of each specific attack in the CNN.

For RNN, the F1-score of each specific attack is shown in Table 15. The model correctly detected the benign and UDP of Mirai. For Bashlite attacks, the model mis-detected COMBO as benign (security camera). It mis-detected Junk as a scan of Bashlite (doorbell), the UDP of Mirai (baby monitor), benign (security camera), and a COMBO of Bashlite (webcam). It mis-detected scan as benign (baby monitor, security camera), TCP as the UDP of Mirai (doorbell), the UDP of Bashlite (baby monitor), benign (security camera), and the UDP of Bashlite (webcam). It also mis-detected UDP as the UDP of Mirai (doorbell) and benign (security camera). For Mirai attacks, the model mis-detected ACK as a COMBO of Bashlite (webcam) and scan as the Ack of Mirai (doorbell) and the scan of Mirai (baby monitor). It mis-detected SYN as the scan of Mirai (doorbell), the COMBO of Bashlite (baby monitor), and benign (security camera, webcam). It also mis-detected Plain UDP as the UDP of Mirai (doorbell, security camera) and benign (webcam).

Table 15.

F1-score of each specific attack for the RNN.

The F1-score of each specific attack for LSTM is shown in Table 16. The model correctly detected benign and COMBO Bashlite attacks. For Bashlite attacks, the model mis-detected junk as a COMBO of Bashlite (doorbell), the SYN of Mirai (baby monitor), and a COMBO of Bashlite (security camera). It mis-detected scan as the SYN of Mirai (baby monitor) and benign and TCP as the ACK of Mirai (doorbell, webcam), the UDP of Bashlite (baby monitor), and benign (security camera). It also mis-detected UDP as the Ack of Mirai (doorbell), benign (security camera), and the SYN of Mirai (webcam). For Mirai attacks, the model mis-detected ACK as benign (security camera, webcam) and the UDP of Bashlite (baby monitor), benign (security camera), and the Plain UDP of Mirai (webcam). It mis-detected SYN as benign (security camera) and UDP as the Plain UDP of Mirai (webcam); it also mis-detected the ACK of Mirai (doorbell) and benign (security camera).

Table 16.

F1-score of each specific attack for LSTM.

Through the experimental evaluation, we found out that the most effective ML models in detecting Bashlite and Mirai botnets are decision tree and random forest in both binary and multiclass classifications. For DL models, the performance of CNN model is better than that of RNN and LSTM. These models have high performance regardless of the type of IoT devices.

5. Conclusions

We developed a framework based on ML and DL to detect IoT botnet attacks and then detected botnet attacks targeting various IoT devices using this framework. Our framework consists of a botnet dataset, botnet training model, and botnet detection model.

As a botnet dataset, we used the N-BaIoT dataset generated by injecting Bashlite and Mirai botnet attacks into four types of IoT devices (doorbell, baby monitor, security camera, and webcam). Bashlite and Mirai attacks each consist of five types of attacks, including TCP, UDP, and ACK. We developed a botnet training model based on five ML models, naïve Bayes, K-neighbors Nearest Neighbors, logistic regression, decision tree, and random forest. We also used the three DL models of CNN, RNN, and LSTM. Based on this training model, we developed a botnet detection model that can detect relevant botnet attacks. The botnet detection model consists of not only a binary classification model that considers 10 Bashlite and Mirai sub-attacks as one attack (and then distinguishes them from benign data) but also a multiclass classification model that can distinguish the 10 sub-attacks and benign data. In the experimental results of the ML-based binary classification, the F1-score of the ML models, except for Logistic Regression (LR), were very high (mostly 1). In the multiclass classification, F1-score of LR was still a low as that in binary classification, but the F1-score of the naïve Bayes model, which was high in the binary classification, was also low. In both DL-based binary and multiclass classifications, the performance of the CNN was much better than that of the RNN and LSTM, and the F1-score of the LSTM was slightly higher than that of the RNN. In other words, the experimental evaluation determined that detecting Mirai and Bashlite botnets in N-BaIoT with ML models, such as decision tree and random forest results in better performance. Among the various DL models, CNN showed the best performance in our framework. Bashlite and Mirai botnets, which occurred in 2014 and 2016, mainly targeted IP cameras and home routers. Our experimental results using the N-BaIoT dataset showed that the performance of botnet detection mostly depends on the type of training models rather than the type of IoT devices. We believe that developing IoT botnet detection models based on decision tree, random forest, and CNN would be an effective way of improving the performance of botnet detection for various types of IoT devices.

In the multiclass classification, the models tend to detect TCP as UDP, compared to SYN and benign. In the production IoT environment, botnet attacks can occur using various types of protocols. Thus, various protocols, including TCP and UDP, should be considered when collecting traffic and training models for the better performance of detecting IoT botnets.

Our study contributes to providing a framework that can easily compare various ML and DL models in IoT botnet detection. In future, we will develop an integrated IoT security framework that detects a variety of IoT attacks, as well as botnet attacks, based on various ML and DL models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, project administration, software, writing-original draft, writing review and editing—J.K.; Investigation, visualization, writing-original draft, writing review and editing—M.S.; Investigation, software, and validation—S.H.; Investigation, data acquisition, and writing-original draft—Y.S.; Project administration, resources, and writing-review and editing—E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1D1A1B07050543).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/focus/fourth-industrial-revolution (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Ashton, K. That ‘internet of things’ thing. RFiD J. 2009, 22, 97–114. Available online: https://www.rfidjournal.com/articles/view?4986 (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Gartner Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends for 2020. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/gartner-top-10-strategic-technology-trends-for-2020 (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2019-08-29-gartner-says-5-8-billion-enterprise-and-automotive-io (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- IoT Attacks Escalating with a 217.5% Increase in Volume. Available online: https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/iot-attacks-escalating-with-a-2175-percent-increase-in-volume/ (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Lin, J.; Yu, W.; Zhang, N.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, W. A survey on internet of things: Architecture, enabling technologies, security and privacy, and applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 1125–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonar, K.; Upadhyay, H. A survey: DDOS attack on internet of things. Int. J. Eng. Res. Dev. 2014, 10, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Abomhara, M.; Køien, G.M. Cyber security and the internet of things: Vulnerabilities, threats, intruders and attacks. J. Cyber Secur. Mobil. 2015, 4, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, I.; Chrysostomou, C.; Hadjichristofi, G. Internet of things: Security vulnerabilities and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communication (ISCC), Larnaca, Cyprus, 6–9 July 2015; pp. 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Deogirikar, J.; Vidhate, A. Security attacks in IoT: A survey. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC), Palladam, India, 10–11 February 2017; pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Neshenko, N.; Bou-Harb, E.; Crichigno, J.; Kaddoum, G.; Ghani, N. Demystifying IoT security: An exhaustive survey on IoT vulnerabilities and a first empirical look on internet-scale IoT exploitations. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2702–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronen, E.; Shamir, A. Extended functionality attacks on IoT devices: The case of smart lights. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), Saarbrücken, Germany, 21–24 March 2016; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alaba, F.A.; Othman, M.; Hashem, I.A.T.; Alotaibi, F. Internet of things security: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 88, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IoT Botnets Found Using Default Credentials for C&C Server Databases. Available online: https://thehackernews.com/2018/06/iot-botnet-password.html (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Available online: https://www.bankinfosecurity.com/massive-botnet-attack-used-more-than-400000-iot-devices-a-12841 (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Available online: https://www.enigmasoftware.com/bashlite-malware-hits-one-million-iot-devices/ (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Thingbots: The Future of Botnets in the Internet of Things. Available online: https://securityintelligence.com/thingbots-the-future-of-botnets-in-the-internet-of-things/ (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- McDermott, C.D.; Majdani, F.; Petrovski, A.V. Botnet detection in the internet of things using deep learning approaches. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 8–13 July 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, O.; Yin, Y.; Gelenbe, E. Deep learning with dense random neural network for detecting attacks against IoT-connected home environments. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 134, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meidan, Y.; Bohadana, M.; Shabtai, A.; Ochoa, M.; Tippenhauer, N.O.; Guarnizo, J.D.; Elovici, Y. Detection of unauthorized IoT devices using machine learning techniques. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.04647. [Google Scholar]

- Doshi, R.; Apthorpe, N.; Feamster, N. Machine learning DDoS detection for consumer internet of things devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–24 May 2018; pp. 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaraman, V.; Gharakheili, H.H.; Vishwanath, A.; Boreli, R.; Mehani, O. Network-level security and privacy control for smart-home IoT devices. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 11th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob), Abu Dhabi, UAE, 19–21 October 2015; pp. 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Meidan, Y.; Bohadana, M.; Shabtai, A.; Guarnizo, J.D.; Ochoa, M.; Tippenhauer, N.O. ProfilIoT: A machine learning approach for IoT device identification based on network traffic analysis. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Applied Computing, Marrakech, Morocco, 4–6 April 2017; pp. 506–509. [Google Scholar]

- Namvar, N.; Saad, W.; Bahadori, N.; Kelley, B. Jamming in the internet of things: A game-theoretic perspective. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Washington, DC, USA, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, Z.; Si, G.; Lin, Y.; Wang, M. An adaptive resource allocation model with anti-jamming in IoT network. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 93250–93258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrishi, K. Turning internet of things (iot) into internet of vulnerabilities (iov): Iot botnets. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.03681. [Google Scholar]

- Kolias, C.; Kambourakis, G.; Stavrou, A.; Voas, J. DDoS in the IoT: Mirai and other botnets. Computer 2017, 50, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Qin, Z.; Novak, E.; Li, Q. Securing SDN infrastructure of IoT–fog networks from MitM attacks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekerevac, Z.; Dvorak, Z.; Prigoda, L.; Cekerevac, P. Internet of things and the man-in-the-middle attacks-security and economic risks. MEST J. 2017, 5, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallgren, L.; Raza, S.; Voigt, T. Routing attacks and countermeasures in the RPL-based internet of things. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2013, 9, 794326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, F.Y.; Devrim, Ü.N.A.L.; Ensar, G.Ü.L. Deep learning for detection of routing attacks in the internet of things. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2018, 12, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiranzaei, A.; Khan, R.Z. An Approach to Discover the Sinkhole and Selective Forwarding Attack in IoT. J. Inf. Secur. Res. 2018, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, V.; Modi, P.; Chaudhri, V. Detecting Sinkhole attack in wireless sensor network. Int. J. Appl. Innov. Eng. Manag. 2013, 2, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Palacharla, S.; Chandan, M.; GnanaSuryaTeja, K.; Varshitha, G. Wormhole attack: A major security concern in internet of things (IoT). Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Clark, A.; Bushnell, L.; Poovendran, R. A passivity framework for modeling and mitigating wormhole attacks on networked control systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2014, 59, 3224–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizal, R.; Riadi, I.; Prayudi, Y. Network forensics for detecting flooding attack on internet of things (IoT) device. Int. J. Cyber Secur. Digit. Forensics 2018, 7, 382–390. [Google Scholar]

- Campus, N.M.I.T.; Govindapura, G.; Yelahanka, B. Denial-of-service or flooding attack in IoT routing. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2018, 118, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Azmoodeh, A.; Dehghantanha, A.; Conti, M.; Choo, K.K.R. Detecting crypto-ransomware in IoT networks based on energy consumption footprint. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2018, 9, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, A.; Pal, S.; Hegde, C. Ransomware auto-detection in IoT devices using machine learning. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2018, 8, 19538–19546. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yu, W.; Champion, A.; Fu, X.; Xuan, D. Detecting worms via mining dynamic program execution. In Proceedings of the 2007 Third International Conference on Security and Privacy in Communications Networks and the Workshops-SecureComm 2007, Nice, France, 17–21 September 2007; pp. 412–421. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, N.; Fu, X.; Zhao, W. Self-disciplinary worms and countermeasures: Modeling and analysis. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2009, 21, 1501–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Garadi, M.A.; Mohamed, A.; Al-Ali, A.; Du, X.; Ali, I.; Guizani, M. A Survey of machine and deep learning methods for internet of things (IoT) security. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.11023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wu, D.; Liu, S.; Li, R. IoT data analytics using deep learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.03854. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, F.; Mehmood, R.; Katib, I.; Albeshri, A. Analysis of eight data mining algorithms for smarter internet of things (IoT). Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 98, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Sorour, S.; Guizani, M. Deep learning for IoT big data and streaming analytics: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 20, 2923–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KISA (Korea Internet & Security Agency). Study on IoT Device Malware Analysis Based on Embedded Linux, KISA-WP-2018-0025. 2018. Available online: https://www.kisa.or.kr/jsp/common/libraryDown.jsp?folder=0012200 (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- HaddadPajouh, H.; Dehghantanha, A.; Khayami, R.; Choo, K.K.R. A deep recurrent neural network based approach for internet of things malware threat hunting. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 85, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodo, E.; Bellekens, X.; Hamilton, A.; Dubouilh, P.L.; Iorkyase, E.; Tachtatzis, C.; Atkinson, R. Threat analysis of IoT networks using artificial neural network intrusion detection system. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC), Yasmine Hammamet, Tunisia, 11–13 May 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Meidan, Y.; Bohadana, M.; Mathov, Y.; Mirsky, Y.; Shabtai, A.; Breitenbacher, D.; Elovici, Y. N-BaIoT—Network-based detection of IoT botnet attacks using deep autoencoders. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2018, 17, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shorman, A.; Faris, H.; Aljarah, I. Unsupervised intelligent system based on one class support vector machine and Grey Wolf optimization for IoT botnet detection. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 11, 2809–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manos, A.; April, T.; Bailey, M.; Bernhard, M.; Bursztein, E.; Cochran, J.; Durumeric, Z.; Halderman, J.A.; Invernizzi, L.; Kallitsis, M.; et al. Understanding the mirai botnet. In Proceedings of the 26th {USENIX} Security Symposium ({USENIX} Security 17), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–18 August 2017; pp. 1093–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, A.; Alexander, D.; Fonseca, O.; Fazzion, E.; Hoepers, C.; Steding-Jessen, K.; Chaves, M.H.P.C.; Cunha, Í.; Guedes, D.; Meira, W. The evolution of bashlite and mirai iot botnets. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Natal, Brazil, 25–28 June 2018; pp. 00813–00818. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://github.com/jgamblin/Mirai-Source-Code (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Bastos, G.; Marzano, A.; Fonseca, O.; Fazzion, E.; Hoepers, C.; Steding-Jessen, K.; Chaves, M.H.P.C.; Cunha, Í.; Guedes, D.; Meira, W. Identifying and Characterizing bashlite and mirai C&C servers. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Barcelona, Spain, 29 June–3 July 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).