Abstract

Integration of internationally educated nurses (IENs) in the workplace over the long term, has not been a clear focus in nursing. The role of the employer organization in facilitating workplace integration for IENs has also not been emphasized in research. The overall aim of this paper is to highlight findings from an instrumental qualitative case study research informed by critical social theory, which examined workplace integration of IENs. The study explored what is meant by ‘integration’ and how the employer organizational context affects workplace integration of IENs. A purposeful sample of twenty-eight participants was involved. The participants included: stakeholders from various vantage points within the case organization as well as IENs from diverse backgrounds who were beyond the process of transitioning into the Canadian workplace—they had worked in Canada for an average of eleven years. Four methods of data collection were used: semi-structured interviews; socio-demographic survey; review of documents; and focus group discussions (FGDs). Thematic analysis methods guided the within subcase analysis first, followed by an across subcase analysis. FGDs were used as a platform for member-checking to establish the credibility of study findings. The resulting definition and conceptual framework point to workplace integration of IENs as a two-way process requiring efforts on the part of the IENs as well as the employer organization. This paper elaborates on selected themes of how beyond transition, workplace integration entails IENs progressing on their leadership journey, while persevering to overcome challenges. Organizational factors such as workforce diversity, leadership commitment to equity and engagement with the broader community serve as critical enablers and the importance of workplaces striving to avoid common pitfalls in addressing the priority of IEN integration are also discussed. This paper concludes with implications and key considerations for workplace integration of IENs.

1. Background

Immigrants are a substantial part of the labour markets in most countries belonging to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. Similarly, internationally educated nurses (IENs) have been recruited to address the health human resource challenges and are a significant segment of nursing workforces in high-income countries. In 2012, about 7% of the 365,422 nurses in Canada had graduated from an international nursing program (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2012), whereas a U.S. national survey estimated 5.6% of the 2.6 million registered nurses were IENs (Health Resources and Services Administration 2010). In Ontario, Canada’s largest province, IENs made up over 12% of the nursing workforce (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2012). Aside from helping sustain the profession, IENs are reflective of the increasingly diverse populations across Ontario and other parts of Canada. The 2012 immigrant landing statistics from Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), indicate that the top three source countries for immigrants and for IENs destined for Ontario were the Philippines, India and China. Furthermore, it is worthy to note that just as in the U.S. (Sherwood and Shaffer 2014), IENs enter Canada primarily as permanent residents with the objective of settling with their families and making Canada their new home (Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2012).

Within the broader context of integrating immigrants in the workplace, there is a growing interest in research on IENs. There is an abundance of research about the challenges experienced relating to migration to the destination country (Kingma 2007; Buchan 2006), processes of navigating through the regulatory systems of credential assessment and registration requirements (Blythe and Baumann 2009), finding meaningful employment, adapting and transitioning into the nursing workplace and discrimination (Bourgeault et al. 2010; McGuire and Murphy 2005; Newton et al. 2012; Primeau et al. 2014; Sochan and Singh 2007; Tregunno et al. 2009). Adams and Kennedy (2006), consultants to the International Council on Nurse Migration, note that there is limited research on the IENs’ post-transition phase, their contributions to nursing and healthcare and the organization-wide efforts of employers that are supportive for IENs. In their review of the nursing and healthcare literature, Ramji and Etowa (2014) conclude that while the term ‘workplace integration’ is used extensively, including in titles of various publications and conferences, the focus is skewed towards the early phases of the IENs’ orientation, adaptation and transition to their new host environment and not integration over the long-term. For instance, a recent integrative review of IENs’ experiences and socio-professional best practices uses the ability of an employee to pass the probation period, as the definition of early professional integration (Primeau et al. 2014). Like other research on the earlier transition phase, this too has an emphasis on how IENs must adjust and meet the social and professional expectations of the host environment; their opportunity to influence nursing practice is not evident (Raghuram 2007). The lack of clarity about what workplace integration entails over the longer-term diminishes the role of employers and effects of the organizations’ contexts on IENs’ progress (Ramji and Etowa 2015).

2. Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to highlight findings from a qualitative case study research on workplace integration of IENs, including the resulting definition and conceptual framework. The overall aim of this study was to understand how IENs are integrated into workplaces beyond the transition phase. The objectives were two-fold: (i) to understand how workplace integration is conceptualized or understood by IENs and other stakeholders; and (ii) to examine how integration is influenced by the organizational context of the workplace. The paper will also provide a brief review of the significance of the topic, the theoretical perspective and the research methodology. The discussion and implications of the findings will focus on key considerations in striving for workplace integration of IENs.

3. Theoretical Underpinnings

Introduction of IENs to the nursing profession and the healthcare system in Canada has brought with it much diversity in terms of race, culture, religion, nursing education and indigenous philosophies and practices from around the globe. While this diversity should add richness to nursing, many IENs who have come to Canada over the last twenty years are racialized (Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2012) and are from source countries that have long histories of colonization. Aside from the lack of clarity and definition of workplace integration of IENs, views about effects of power and powerlessness of IENs in the workplace are also under-represented in the literature.

This research was approached from a critical social theory (CST) perspective. Works of various theorists and thought leaders with a critical outlook underpin this study. Building on Weber’s (Weber 1978) theory of domination and social closure, Lukes’ (Lukes 2005) three dimensions or faces of power provides insights as to how oppression and power imbalances impact not only groups such as IENs but also the structures and systems that make up their workplace organizations. An anti-racist organizational change model by Minors et al. (1995) and the Positive Action Approach by National Health Service Employers and University of Bradford (2005) focus on cultivating inclusive workplace cultures. Nussbaum’s (Nussbaum 2005) critical analysis of organizations also helps identify policy areas that require closer examination for removal of barriers and redressing exclusive practices. The CST lens was utilized to critique organizational practices and for continual dialogue about the creation of new and shared meanings about what integration of IENs is and can or should be.

4. Methodology

The study design was an instrumental case study approach as described by Stake (1995). Case study research is a qualitative approach whereby “the investigator explores a real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case)…over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information…and reports a case description and case themes” (Creswell and Poth 2018). In an instrumental case study, the researcher focuses on an issue or phenomenon and then selects one case to illustrate this issue in real-life (Stake 1995). The instrumental ‘case’ examined in this study is a single employer organization, St. Michael’s Hospital, with a track record of supporting IENs. Given that the objective of this study was to broaden our understanding of IENs’ workplace integration, an active case was more appropriate for the best learning to come across—an organization similar to what Adams and Kennedy (2006) might describe as a positive practice environment for IENs. With a history of several initiatives related to the integration of IENs and other internationally educated professionals, St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Canada, was selected as such a setting.

Data collection took place between October 2014 and March 2015 after obtaining approval from research ethics boards of the study site and University of Ottawa, Canada. A purposeful sampling strategy was used to select twenty-eight participants from various vantage points of the case organization to understand workplace integration from multiple perspectives. IEN participants were accessed through awareness strategies such as presentations at meetings, information letters and posters. Contact information was displayed on letters and posters so that prospective participants could get in touch with the researchers voluntarily. Snowballing technique was also used for both IENs and other stakeholder participants. Preliminary contact was made to explain the purpose of the study, gain consent and organize an interview time and place.

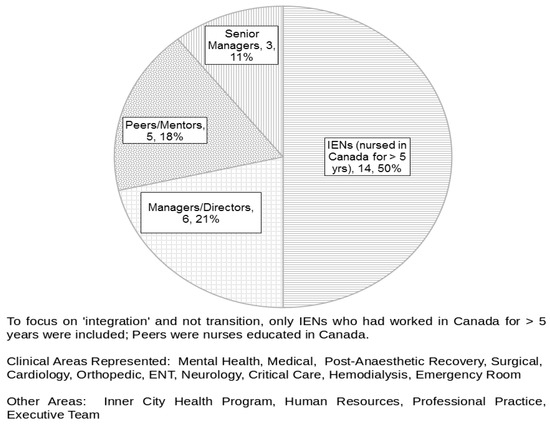

The sample (see Figure 1) was diverse with respect to age range, gender, country of origin and nursing education, immigration status and number of years and types of nursing or other professional work experiences. Fifty percent were IENs from diverse backgrounds and the rest of the stakeholders included peers/mentors (18%), managers/directors (21%) and senior leaders (11%). The majority of the IENs were female (86%) and in the 35 to 54-year age group (79%). Most of the IENs were Canadian citizens (86%) and had originated from seven countries: Philippines (43%), China (22%), Belarus (7%), Croatia (7%), Scotland (7%), Trinidad and Tobago (7%) and the Ukraine (7%). All the IEN participants were practicing in the registered nurses (RN) category of nursing. On average, IENs had 5.6 years of nursing experience prior to coming to Canada, with a total average of having worked as a nurse for 16.5 years.

Figure 1.

Sub-Units of Analysis (n = 28).

Data was collected through four methods: a total of 28 semi-structured in-depth individual interviews; socio-demographic survey administered to each of the 28 interviewees; review of 25 organizational documents and 5 focus group discussions with a total of 13 participants. The focus groups served as a form of member checking and further data collection, especially with respect to recommendations. Each interview and focus group participant provided informed consent. At the organizational level, permission was obtained from senior representatives at the study site about identification of their organization during and/or after completion of the research. Privacy and confidentiality was maintained by giving participants the option of being interviewed at an accessible offsite location away from their area of work; alpha-numeric code numbers were used to identify participants; interview notes, demographic profile and consent forms were separated from the data files and all electronic data files and storage devices were password protected. Finally, in reporting out the findings, quotes have been selected carefully so as not to inadvertently identify the participants.

Thematic analysis was carried out in various stages. At a preliminary level, data analysis occurred simultaneously with data collection; it was inductive and iterative. Inductive coding of the data from the interviews and document sources did not start with a pre-established list of codes but instead the codes emerged from the data (Braun and Clarke 2006). After analyzing the perspectives of each individual participant (within subcase analysis), the data was then re-sorted using NVivo 10 according to four stakeholder groups that make up the sample (i.e. between sub-unit analysis—of IENs, peers/mentors, managers/directors and senior managers). This was followed by analysis of the IENs across each of the sub-units, namely: peers/mentors, managers/directors and senior managers—to identify areas of convergence and divergence (Stake 2006).

Four criteria to achieve methodological rigour (Lincoln and Guba 1985) were applied: (i) credibility through member checking and triangulation. (ii) transferability by ensuring a thick description of the case (Stake 1995) and through peer debriefing (Morse 2018); (iii) confirmability through audit trail and various records such as transcriptions of interviews and focus group discussions, process notes from debriefings as well as analytic matrices, tables and flow charts; (iv) reflexivity through journaling.

Table 1 shows how the sub-themes are clustered with those highlighted by all/most participant groups at the top. These themes and sub-themes are discussed and illustrated in the next sections with direct quotes from the case study data.

Table 1.

Across Sub-Case Analysis—Select Themes of ‘Integrated’ IENs and Organizational Factors.

All these levels of analysis provided important ways of understanding the overall case organization (Baxter and Jack 2008). Guided by the tenets of critical social theory, the data analysis revealed the multiple issues nested within the topic of workplace integration of IENs including efforts required by and results achieved at the levels of both the IENs and the organization. IENs in the study sample shared their stories and had their voices heard; some participated in member-checking through focus group discussions to ensure the trustworthiness of the key findings and to add to the analysis, as well as suggest recommendations.

5. Findings

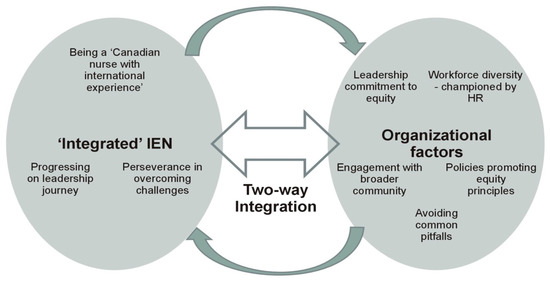

The findings presented here are based on the across-case analysis between the four groups of participants. Overall, there are nine major themes as captured in the conceptual framework in Figure 2. ‘Two-way integration’ between the IEN and workplace organization is an overarching theme and amplifies the idea that workplace integration is a process involving efforts on the part of the IEN as well as the employer. Also, that the changes resulting from workplace integration occur both at the individual IEN and the organizational levels. This overall theme of two-way integration is the subject of a separate analytical paper.

Figure 2.

Workplace Integration of IENs—Conceptual Framework.

This paper elaborates on selected themes of how beyond transition, workplace integration entails IENs progressing on the leadership journey, while persevering to overcome challenges. Organizational factors such as workforce diversity, leadership commitment to equity and engagement with the broader community serve as critical enablers and the importance of workplaces striving to avoid common pitfalls in addressing the priority of IEN integration are also discussed. These themes and their sub-themes emerged when the data was re-examined for convergence and divergence between the IENs, peers/mentors, managers/directors and senior leaders.

5.1. Progressing on the Leadership Journey

One major cross-cutting themes about workplace integration has to do with the individual IEN progressing on her/his leadership journey. Assuming responsibilities that require advanced clinical expertise and leadership capabilities is a central way of how all participant groups in this research think about IENs who are ‘integrated.’ Participants’ perspectives about integrated IENs progressing on their leadership journey have four sub-themes: (i) being an expert resource and role model; (ii) commitment to learning, (iii) broader understanding and involvement to influence change and (iv) satisfaction and retention.

Being an expert resource and role model—IENs and managers/directors provide examples of leadership roles such as team leading or being the charge nurse on shift, getting involved with clinical fellowships and demonstration or pilot projects, as well as hospital-wide special initiatives, including being designated as “super user” for trials of new equipment or software. Responsibility as a mentor or preceptor to students and newly hired staff is another common expectation highlighted by all participant groups. Peers/mentors describe how IENs serve as role models while working alongside their peers and influence others in a practical sense:

Most of them are very passionate… for example, the family of the patient is very, what we call not demanding but very anxious and frequently calling or something like that. But I see most of the time, the internationally educated nurses are very patient to engage into that care… to find the solution or to work alongside with the patient and the family to tackle the issue…they see it’s a chance to make things better, they see a chance to improve care.(participant P010)

Commitment to learning—IENs value the development that results from the various leadership roles as part of their integration in the workplace. Senior managers and IENs talk about these as opportunities to “give back” to others, to the organization and in the case of involvement with the professional association and the labour union, giving back to nursing:

Because I find if the IEN decides to get engaged and to develop the skills and to pursue dreams, they’re not doing it for their own selfish benefits, they’re doing it because they’re nurses who are dedicated to their profession. And they want to advance themselves but also advancing the nursing profession as a whole.(participant I027)

Peers/mentors emphasize how all nurses on staff at St. Michael’s Hospital [hospital name] have available to them, numerous opportunities to get involved in projects, committees and professional development. Managers/directors reiterate that the IEN who is integrated in the workplace is one who is committed to lifelong learning. Senior managers highlight the importance of self-advocacy as a skill, especially for pursuing professional aspirations, both within the workplace or externally.

Broader understanding and involvement to influence change—Managers/directors focus on the importance of language proficiency and the confidence in communicating in English as a pre-requisite to influencing others. This group also highlights the importance for IENs to understand the organizational process and culture to bring about change in the workplace: “There are some opportunities for people to take part. But to take part, they need to understand … what that process looks like, that you can’t just walk in and say something and immediately change happens” (participant L005). IENs describe how bringing practice issues or concerns to their manager or the nurse educator on the unit is a common way of initiating dialogue. An open and participative management style on the unit allows for the engagement of the team members in considering possible alternatives or changes.

Managers/directors reflect on the steep learning curve experienced by IENs during the early transition phase when they are adjusting to Canadian nursing practice and the local workplace environment. One manager refers to this as “soaking up like a sponge” and then when integrated, the IEN is able to “squeeze the sponge” and share with or contribute to others’ learning (participant L005). Senior managers explain how IENs can help expose their colleagues to different ways of thinking about health and illness and that the prevailing way may not be the right or only way:

I think our IENs help us to be empathetic that there are other ways, not just the Canadian way of looking at treatment and…death and even care of the body after, these things…I think, when I talk to IENs about these things, I become very sensitive to the fact that what you know is just what you know, it doesn’t mean it’s right.(participant L018)

All groups of participants refer to how getting involved in initiatives to influence nursing policies and practices is what can be expected of an IEN who is integrated in the workplace. Beyond the workplace, getting involved in the nursing community, appreciating the roles and responsibilities of its various institutions, is also described as an expectation by the IENs integrated in the workplace. Senior managers state that integrated IENs understand the broader healthcare system and appreciate how it impacts their workplace organization.

Satisfaction and retention in the workplace and in nursing are additional dimensions of this theme of progressing on their leadership journey. Senior managers and IENs agree that workplace integration is when the IEN is happy at work, when there is a sense of belonging and satisfaction in her/his professional capacity. IENs express gratitude and a desire to stay with the organization over the long term. An IEN participant puts it as: “…there is a bigger chance of them staying within the workplace where they are because there’s one thing about the people, nurses especially, who come from other countries, there’s a gratitude for being given an opportunity to grow” (participant I027).

5.2. Persevering to Overcome Challenges

Participants often juxtapose the ideal achievements of an integrated IEN with the real barriers they continue to experience and must persevere well past the earlier period of transitioning into the workplace. Two common sub-themes associated with barriers to the IEN progressing on her/his leadership journey relate to: (i) personal and/or family commitments and (ii) lack of preparedness of the workplace environment to be influenced by IENs.

Personal or family circumstances—IENs as well as their peers/mentors identify this as a barrier for some IENs to get involved in educational activities or committee work. Aside from childcare and other in-home responsibilities, the need to juggle multiple jobs to generate enough income to support extended family members, including those off-shore, are barriers for some IENs: “I’ve done like a lot of courses already prior…I wanted to take the bachelors here but I got married and then I’m supporting, like my parents…I had to bring them here too, I sponsored them” (participant I008). Even though there may not be an out-of-pocket expense for pursuing courses or workshop offerings, being available to attend, especially during her/his days off is challenging as explained by this peer/mentor: “I get to talk to some [IENs]… and I say that, you know…there is a workshop and it’s free…but they have to use their days off, so that’s another hindrance too for IENs” (participant P002). Various situations at the personal level prevent IENs from pursuing their aspirations. One IEN explains concretely, her hesitation in using any vacation days for professional development:

I want to save my vacation to go back [home] to China, which is a long way and you want to save all your, maybe the whole year’s vacation. But if I want to also learn and if I was asked to use my vacation time, then…I will probably kind of resist to think about…do I really want to use my vacation time?...I may not be able to go.(participant I022)

Similarly, peers/mentors indicate that committee meeting times to develop policies or discuss changes are often problematic due to work schedules, preventing IENs from participating, especially if they have commitments during their days off.

Lack of preparedness or openness of workplace to be influenced by IENs—While there are many examples of support for the IEN to take on advanced level responsibilities, there are concerns about how senior or leadership roles can also suppress the IEN’s development. For example, one IEN participant describes how because of her advanced skills, she is not able to get the scheduling accommodation she requires for pursuing her educational goals:

I don’t know why they don’t give the other staff other skills, so they can do telemetry…special skills…and then they can free up the other senior staff. Because I find I’m always either in the [name of unit withheld] or I’m in the charge nurse role that…no one can work on those areas…I was thinking maybe that’s why they’re not supporting me in my schedule if I go back to school.(participant I015)

It is also not clear as to how open others are in terms of having IENs share or speak about their knowledge, especially from their international experiences. For example, one manager suggests that when the IEN is reflecting a lot about “how it was back home,” this may be a sign of someone who is not as well integrated. Another manager explains how for IENs to bring forward ideas, it is important they learn “diplomatic or strategic” English and to only present them in the context of “quality improvement” if they want to be heard (participant L005). One peer talked about how an IEN colleague was received positively at a staff meeting with respect to her suggestions on how to do things differently. It was only later in a private conversation, that the IEN disclosed that the proposed change was how they did things “back home” (participant P016).

The findings related to what is expected of an IEN who is integrated in the workplace highlight some of the efforts and achievements of the IEN at the individual level. The focus on how the organizational context influences workplace integration of IENs is evident in the next section. Specifically, the four themes to be discussed are: workforce diversity, leadership commitment to equity, engagement with the broader community and avoiding common pitfalls.

5.3. Workforce Diversity

All participant groups agree that the level of diversity in the staff at the case organization is one of the main facilitators of workplace integration of IENs. Diversity helps create a sense of comfort and belonging for IENs. There is a common understanding that the organization’s mission and designation as a teaching hospital, provides rationale for ensuring that policies and practices are in place so that like patients, staff of all backgrounds are also welcomed and valued. Two sub-themes emerging from the participants’ perspectives on workforce diversity include: (i) the key role of the Human Resources (HR) department in recruitment and retention of diverse employees and (ii) openness, acceptance and camaraderie.

HR department as a key player in recruitment and retention of diverse employees, including IENs—Senior leaders, managers/directors and IENs have expectations that at the corporate level, human resource initiatives should help sustain the focus and track outcomes related to the hiring, progress and satisfaction of IENs. Human resource departments have a vital role in ensuring recruitment and retention practices are fair and transparent.

Openness, acceptance and camaraderie—IENs and mentors/peers attribute the diversity of the nursing workforce to having an open and accepting team culture. Aside from how the team becomes more responsive to needs of patients from diverse backgrounds, they speak to how IENs as newly settling immigrants also struggle and need to be given a chance. They appreciate the hiring managers’ consideration and interest in recruiting IENs for the team, especially their sensitivity to those IENs who are already on staff but underemployed as clinical assistants and who are actively working towards their nursing registration. Several IENs specify how the feeling of being supported and included is accentuated when their colleagues are of a cultural and linguistic background like their own. Speaking to others in their mother tongue strengthens the connection and creates a sense of community. On the other hand, they also have a heightened awareness of how this in turn can sometimes make others feel excluded:

Because sometimes…so at night time, we are 13 nurses and 10 are Filipinos and three are non-Filipinos. And what we do, we group each other and talk in Tagalog while we’re eating in the lunchroom. So, what would you feel if you were one of those three?(participant I013)

The organization’s deliberate efforts to diversify the nursing workforce are a key factor in promoting the IENs’ sense of belonging and integration in the workplace.

5.4. Leadership Commitment to Equity

Participants’ perspectives about leadership commitment to equity as another organizational factor influencing workplace integration of IENs have three sub-themes: (i) senior-most leaders visibly championing the cause; (ii) nurse managers’ leadership style and sensitivity towards IENs; and (iii) supports for learning and career development.

Senior-most leaders visibly championing the cause of health equity—all participant groups agree that this is critical for others to feel reassured that the priority of workplace integration of IENs will be acted upon. One peer/mentor states: “I would say it [priority of IEN integration] would obviously come from the leadership down. Because it’s not something that can just be, you know, from unit to unit. It is really something…from the CEO downwards” (participant M007). However, at the corporate level, it is challenging to determine which department will be the lead for implementing and monitoring the agendas for equity, diversity and inclusion. The case organization has had the experiences of having a clinical program as well as the HR department take the lead and with each scenario, there have been challenges.

The concept of equity is spontaneously raised by senior leaders. A definition is offered by one participant: “Equity is more than just treating everyone equally, in fact, it means doing more for some groups, because they start from a position of inequity in the first place...to bolster their position, you have to do more” (participant L026). At the senior management level, there is clarity and comfort that from an equity perspective, different supports may be required for IENs for them to achieve workplace integration:

But one of the discussions I had with our nurse leaders at one point, like the new grads, we isolate them because they’re new grads and they’re not the same as our three and five and 20-year nurses. So, it’s getting people to be comfortable with being different is okay.(participant L018)

Nurse Managers’ leadership style and sensitivity—IENs emphasize that the nurse manager sets the tone with the rest of the team and affects their integration in the workplace: “Because we have meetings…they welcome opinions, suggestions…for the improvements of our units…they ask for our ideas” (participant I008). During the bi-annual performance appraisal process, managers inquire about goals and aspirations they have for future growth; concrete support or follow up for achieving these is expected by IENs. IENs may need career coaching to successfully compete for promotions. Managers/directors acknowledge that other employees have also raised the need for career coaching and succession planning in staff engagement surveys.

Support for learning and career development—Peers/mentors reinforce how learning goals and plans must be clear and customized for the individual. Development opportunities for nurses are highlighted as important for growth and integration of IENs in the workplace: “I think that with the opportunities to further grow and develop, you continually integrate” (participant L006). Senior managers describe how investment in the growth of the IEN beyond the initial transition phase encourages them to in turn contribute to the development of others and promotes their integration in the workplace:

It’s not just okay, now they’re here and they’re fully working and my job is done. It’s now how do they contribute back to the role of IENs. You know, it’s always thinking of maximizing your investment for the best of that individual in your organization.(participant L018)

5.5. Engagement with the Broader Community

Participants’ perspectives about how external engagement promotes workplace integration of IENs has three sub-themes: (i) responsiveness to the community; (ii) awards and recognition; and (iii) senior leaders’ involvement at the system level.

Responsiveness to the community—Senior leaders and managers/directors describe how the strategic priority of recruiting and integrating IENs came to light from the organization’s engagement with its community stakeholders. IENs and other internationally educated professionals were part of the hospital’s catchment area; their needs to integrate were also aligned with the organization’s human resource needs. They explain how the external community environment reinforces the organization’s efforts to facilitate workplace integration of IENs: “It met our staff shortages needs…not just ours but broader than St. Michael’s Hospital [at the healthcare system level] …” (participant L005).

Managers/directors and senior leaders describe how their participation in various external forums has been beneficial in furthering the cause of workplace integration of IENs within the case organization itself. Accessing additional funding from external sources has helped the organization keep the priority of IEN integration stay at the forefront. Two such examples of special project funding obtained by the case organization are: (i) implementation of best practice guidelines on embracing cultural diversity and managing violence in the workplace; and (ii) piloting a mentoring initiative for IENs and other internationally educated professionals. Both these projects have focused directly on facilitating integration of IENs as well as benefiting other employee groups within the workplace.

Awards and recognition—IENs, managers/directors and senior leaders highlight that the organization’s commitment to addressing barriers encountered by IENs and other internationally educated professionals within its community is noticed by external stakeholders. Given that integration of immigrants is a broader system level priority, efforts of St. Mike’s, a major employer in Toronto, have received formal recognition by external bodies. External recognition through prominent awards for the organization helps reinforce the importance of IEN integration to internal stakeholders:

The mentorship program that we had here...I think first of all, the knowledge of knowing that it existed at St. Mike’s, there was a sense of pride in the organization that we were doing something...even though they might not be involved.(participant L005)

Such recognition also results in the case organization becoming known as an expert resource at the broader system level; it is sought out and consulted for its experience and expertise with supporting IENs.

Senior leaders’ involvement at the system level—Senior leaders emphasize how their role in external projects or agencies focused on IENs is also reinforcing for those with the case organization: “I am on the board of [name withheld] and…so not only do they see that I’m saying we should do this but they’re saying, wow, she must really think this is important, right?” (participant L018). Through these involvements, opportunities for the case organization to accept IENs for job shadowing and clinical placements, as part of bridge training programs are also readily facilitated. These are additional simple but meaningful ways that reiterate the organization’s commitment at the frontline for nurses and facilitates workplace integration of IENs.

5.6. Avoiding Common Pitfalls

Despite its achievements, there are ongoing challenges that speak to how even the case organization’s efforts are a work in progress that others can also learn from. There are two primary challenges: (i) wavering commitment in parts of the organization; and (ii) sustaining organizational commitment to the priority of IEN integration.

Wavering commitment in parts of the organization—IEN participants notice that there is an uneven application of hiring policies across different units or clinical areas within the hospital. Some speculate that with greater fiscal constraints, new graduates may be preferred as the years of experience that IENs bring results in higher salary costs and can serve as a deterrent. There is concern that corporate level policy commitments to integration of IENs may not always get implemented at the unit level. This, coupled with the IEN’s lack of familiarity and comfort to self-advocate, point to the need for some pro-active communication. A supportive and proactive communication strategy could outline all the available opportunities, along with what is expected in terms of the typical trajectory of the IEN’s development. A peer/mentor speaks to this:

If they set up a policy for IENs, at a corporate level, I think what is needed is in a small scale, on a unit level...follow-up on those policies. And those policies should be known, should be communicated to IENs, not only say that there’s a policy…what to expect and they say, okay, this is what I need to do to be able to integrate better…you’d be encouraged to do more training...by your manager or your educator to be more involved. And so that you will know what is expected of you…For nurses that have been there for a while, they should be encouraged to participate in policymaking or be approached and be encouraged to be involved.(participant P002)

While attending in-services or courses pertaining to the immediate role do not seem to have been an issue, the lack of direction and feedback following application for leadership roles have been discouraging for some IEN participants:

I strongly believe in continuing education…I have a Masters, I have other qualifications…and I’m still at the bedside…but it’s not because I want to be…I’ve applied for several positions and there’s always, you know, oh, the interview went well, you did well but we found somebody who’s better, you know…I have not received any helpful feedback.(participant I012)

Post-application debriefing and career coaching is recommended by some IEN participants: “Having an opportunity to grow and become more of a leader, how do you do that? So if you know…what the steps you need to take, to get there, that’d be helpful” (participant I027).

Work schedules or related accommodations to pursue aspirations of higher education have prevented other IENs from integrating more fully at the case organization:

I know other senior nurses too who wanted to maybe become like…having aspiration like to do other than bedside…I wanted actually to be a clinical instructor at one time…management wasn’t supportive of doing this schedule for us. Like it was such a hindrance, it’s such a big job for me…I have to ask…then she okayed it but during the scheduling they don’t give me days that I wanted to be off. Because I have to be in school…I have to find someone all the time like to work for me…I find that so distracting…I gave up the course…I took that, just one course and I didn’t pursue it again.(participant I015)

An ongoing communication strategy to create awareness and understanding of workplace integration of IENs across the case organization is reiterated by one manager/director participant when acknowledging accomplishments: “We’ve won all kinds of awards and I think we deserve them…but by the same token, I think we still have a lot left to do for…the general staff population to become aware [of IENs/IEPs]” (participant L026).

Sustaining organizational commitment to the priority of IEN integration—Managers/directors reflect on the benefits of the Mentoring Program and the efforts championed by the HR department for a period: “so many good things that suddenly come to an end for XYZ reasons, funding maybe…” (participant L026). The struggle to sustain the focus on workplace integration of IENs over the long term is real for St. Michael’s Hospital as there are multiple priorities and demands. Senior leaders emphasize the need for a deliberate and strategic approach whereby the commitment to workplace integration of IENs is aligned with the organization’s core priorities and all areas are held accountable for key outcomes. Being explicit and keeping the agenda of equity, diversity and inclusion on all the decision-making platforms is recommended by one senior leader:

And the other barrier I think, which is true in all busy organizations, is if we’re not again explicit and clear and keep the IEN human resource strategy visible and on an annual basis, looking at how many IENs did you hire, how are they doing, what was their turnover, those sorts of things. So measuring the impact of our strategies…it’s a barrier if you don’t do it.(participant L018)

The issue of who has the lead at the corporate level and from a structural point of view is relevant for sustaining the priority but not easy to resolve:

I’ve seen other organizations try to do what St. Mike’s has done and create an office of diversity or…where that’s all they do. And that to me is not integration. And I think we’ve had a measure of success here because…of a number of clinical programs are also part of the portfolio…If you just create an office of diversity or an office of equity, it just becomes something out there on its own…there is no direct link to clinical care delivery…those people in those positions have no credibility.(participant L025)

The findings related to the organizational facilitators of IEN integration focus on the workplace environment’s influence on IENs. Some emerging factors are broad in scope and have relevance for IENs, as well as other internationally educated professionals and groups of staff who may experience inequities or exclusion. The themes identified have implicit in them, the notions of a systematic organization-wide approach and leadership commitment to sustaining the priority of workplace integration of IENs.

6. Discussion

The overarching theme of workplace integration of IENs as a ‘two-way’ process and the major themes related to what an ‘integrated’ IEN is and the organizational context are aligned with how the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (2005) defines integration of immigrants and refugees. This notion of integration as a ‘two-way’ process has not permeated into the nursing discourse about IENs; in fact, Raghuram (2007) argues that integration of IENs has been predominantly ‘one-sided.’ As noted earlier, a forthcoming publication specifically focuses on this theme of ‘two-way’ integration (Ramji and Etowa forthcoming).

The major theme of how ‘integrated’ IENs expect to progress on their leadership journey, albeit, the need for perseverance in overcoming challenges, has been a focus in this paper. IENs who are integrated function as professionals alongside with their peers, leading teams, participating in projects to influence practice improvements, as well as advancing in their careers. Aside from clinical expertise, colleagues benefit from IENs’ knowledge of the role of specific cultures, traditions and religions in illness and in healing. The non-IEN participants in this research acknowledge how integrated IENs are effective as role models, mentors, preceptors and team leaders. This finding does not resonate with what generally appears in the literature about IENs and their leadership capacities. Further to Gerrish and Griffith’s (Gerrish and Griffith 2003) finding of IENs’ difficulties in challenging team members, mentors and managers in Ferguson et al.’s (Ferguson et al. 2014) research also feel that IENs are not ready to be in charge and assume leadership of a team. Both studies indicate they are exploring “integration” experiences of IENs but neither one provides any definitions and they both seem to focus on the challenges IENs encounter while they are still adapting and transitioning into the new host environment. It is recognized that St. Michael’s Hospital, the case organization in this research, is an exceptional case and that while social closure (Roscigno et al. 2007) may be operating to some degree, the discussion of exclusionary practices affecting IENs are limited.

Involvement on unit level or hospital-wide committees and projects are viewed as leadership development and career advancing activities that integrated IENs engage in, according to participants in this study. This is contrary to Wheeler and Foster’s (Wheeler and Foster 2013) finding that both IENs and their US educated counterparts shared similar perspectives, in that they do not value participation in committees to influence governance or decision-making and prefer to be at the bedside. While the logistical barriers of time and cost (schedules, days off, etc.) explained in Wheeler and Foster’s (Wheeler and Foster 2013) work are also concerns of participants in this research, the sense of apathy is not conveyed. As noted earlier, the case organization is an exceptional case and its culture of valuing nurses’ involvement through continuous communication and encouragement from management could be the difference. In fact, the IEN and senior manager participants go even further and refer to involvements of integrated IENs at a broader level, providing leadership and exerting their influence outside the workplace, within the profession. Such references do not seem to be evident in the IEN related literature.

Winklemann-Gleed (2006) states that professional identity can be an integral part of personal identity or sense of self-worth among immigrant nurses. Career development is therefore important and if it is not encouraged by employers, immigrant nurses would be prepared to change their place of work (Winklemann-Gleed 2006). Adeniran et al.’s (Adeniran et al. 2013) research indicates that the mean number of continuing education hours and professional certifications in practice areas between IENs and US educated nurses are comparable. They also find that even though IENs enter the profession with higher education, they are less likely to go on to pursue advanced degrees and receive promotions less frequently compared with their US educated peers. The consequence of fewer IENs in leadership roles is noted by Adeniran et al. (2013) and supported by Premji and Etowa (2014), who document the concern about lower representation of visible minority nurses in leadership roles in Canada.

IENs may experience these challenges because social closure may be operating in explicit or implicit ways (Roscigno et al. 2007). Even though IENs are practicing competently and may be demonstrating leadership in various ways, they may be overlooked for development opportunities. Social closure may be implicit in how managers and other team members are described to not always be sensitive to the cultural differences in leadership styles and self-promotional behaviours (or lack of) exhibited by IENs. As settling immigrants, IENs frequently have different demands and realities at their personal and family level. The need for re-establishing family and financial stability may have a local as well as overseas dimension and could exert added strain on the IENs in terms of having any disposable time or income. These areas requiring perseverance, where social closure may be operating, are also supported by Salma et al.’s (Salma et al. 2012) study on IENs’ experiences and perceptions of career advancement and educational opportunities. Among the major themes, Salma et al. (2012) found that priority of motherhood, communication and cultural barriers and perceptions of lack of opportunity were key factors that hindered IENs’ career advancement. The IENs’ perseverance to transcend challenges has an underlying tone which relates to Lukes’ (Lukes 2005) overt face of power theory whereby organizational approaches or norms may appear to be “open” to most but do not fully account for differences amongst the groups. As a result, the IENs’ non-participation or participating in ways that are not familiar to the dominant group could be misinterpreted as incompetence leading to further exacerbation of the pressures on IENs.

Workforce diversity at the case organization has been noted favourably as a key factor in creating openness, acceptance, camaraderie and a sense of belonging for IENs. Although it is implicit in the notion of an inclusive culture, the emphasis placed by research participants warrants that the vital role of HR in recruiting and integrating diverse staff be made more explicit. Various experts also agree that human resource policies and practices can be exclusionary in subtle and covert ways, as employment systems are set up for homogenous or the dominant group and “others” can be perceived to not “fit in” (Manning 2012; Minors et al. 1995; Weiner 2012). This is referred to as unintended systemic or institutional racism (Manning 2012) and if the goal of recruiting and sustaining a diverse workforce at all levels of the organization is to be achieved, deliberate efforts are necessary (Minors et al. 1995). The review of organizational documents and interviews with participants both indicate that recruitment of IENs has been a strategic priority for the case organization. However, accountability systems to track and monitor the degree of workforce diversity at the case organization do not exist—in other words, information about diversity in different programs, disciplines and organizational levels is only anecdotal. This is problematic because as McKenzie (2015) puts it in terms of basic democratic principles: “if you do not count people, they do not count” (p. 4). The case organization is now part of a regional initiative to measure the level of diversity in its patient population in comparison to its community profile, by incorporating demographic questions in intake/admission processes. Similar initiatives focused on measuring workforce diversity would allow the organization to track progress on its recruitment and retention goals, including the extent to which the staff profile is reflective of its patient population.

Leaders at the top influence managers and staff at other levels and set the tone for the culture in the workplace. The leaders’ strategic management approach to keep integration of IENs on all agendas helps translate this priority into policies and practices that are valuing of IENs and that are sensitive to their needs. However, this study highlights that the concept of equity is challenging to grasp and needs to be “unpacked” regularly. Continuous education and dialogue to further clarify the concept of equity, as opposed to equality and how the organization can implement equitable practices, is needed for staff and managers. Learning exchanges which recognize that “the other” is both “present” and “different” and that this difference can be an opportunity and not a burden, can add to the organization’s efforts towards equity (His Highness the Aga Khan 2010).

At the case organization, there is greater clarity about health equity in the context of patient care and several programs relevant to the priority populations are in place. When it comes to offering specific supports to IENs, it appears that some nurse managers are hesitant and provide the rationale of wanting to treat all of their staff nurses “equally.” For staff who might be in positions of inequity, Minors et al. (1995) explain that to achieve equitable outcomes, it is important that workplaces are also considerate of their need for differential supports. Given that the frontline managers’ support and openness are seen to be critical by IEN participants in this research as well as in other studies (Gerrish and Griffith 2003; Hoxby et al. 2010; Parkouda 2014), a focused development program for nurse managers may be appropriate. Under the broad topic of equitable practices for managing the workforce, nurse managers would benefit from different perspectives on harnessing the talents of a diverse team. Aside from key functions of employee engagement, performance appraisals and access to organizational networks (Manning 2012), understanding cultural dimensions in leadership styles (House et al. 2002; Konu and Viitanen 2008) may also be relevant for nurse managers at the case organization. Some organizations have gone further and instituted accountability measures by expecting nurse managers to have the core competency of supporting IENs effectively (Romaniuk 2015).

Workplace integration is enabled when employer organizations recognize their role in promoting community integration. In a US study on the relationship between IEN hiring practices and broader community and hospital characteristics, Cho et al. (2011) found that employers in urban areas with older, more diverse and more educated populations, are more likely to report hiring IENs. These researchers explain that the findings may reflect the hospital administrators’ perceptions of community receptiveness to IENs. Various experts on integration of immigrants and diverse peoples point out that employees are part of the larger community and employers should work with and contribute to the external context (Galabuzi 2012). For workplace integration to be successful, the “community as a whole must grow socially, culturally and economically as it faces up to the challenges of greater diversity” (Creticos et al. 2006, p. 3).

Finally, challenges in sustaining the commitment and getting broad based buy-in for workplace integration of IENs cannot be underestimated. Adams and Kennedy (2006) emphasize the critical role of employers in undertaking systematic organization-wide approaches that create an inclusive, enabling climate that values the contributions of IENs. Several participants refer to how other priorities in the organization can compete for finite resources, resulting in a shift away from the focus on workplace integration of IENs. Choiniere and Macdonnell (2012) provide added insights into how healthcare restructuring and policy changes have resulted in nurse managers overseeing more departments, more staff and needing to be more focused on cost savings, as opposed to offering supportive leadership for their teams. Competing demands, coupled with a lack of clarity about equity, can have the inadvertent effect of IENs being “left off the agenda” as in Lukes’ (Lukes 2005) second or covert dimension of power. Persistent reinforcement of workplace integration of IENs as part of the organization’s strategic priorities and core business is the leadership challenge.

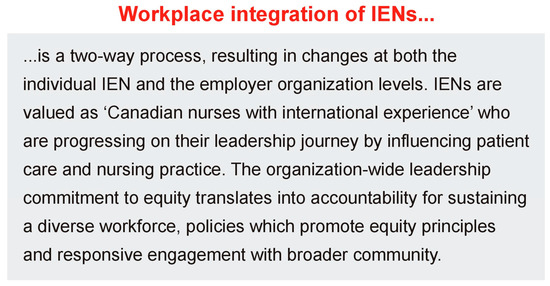

7. Implications

This research has resulted in a definition of workplace integration of IENs as stated in Figure 3. It provides nursing with a vision of what IENs’ workplace integration can be, both at the organization and the IENs’ levels. The notion of two-way integration in the workplace amplifies the idea that the process involves efforts on the part of the IEN as well as the employer. Similarly, changes resulting from workplace integration occur both at the individual IEN and the organizational levels.

Figure 3.

Definition of Workplace Integration of IENs.

The organizational environment is inclusive in all respects and this way, barriers to fairness, equity, acceptance, belonging and participation are eliminated. That is, IENs who are immersed in such a workplace do not just “fit in” in order to survive but instead they thrive to develop and perform at their optimal levels. IENs have equitable opportunities for career advancement and mobility; they experience fair and equitable treatment by colleagues, managers, patients and families. IENs are encouraged to share their expertise from their former international practice environments, so that lessons can be drawn for the workplace to lead to better outcomes for the nursing care of patients. The workplace achieves and sustains this context through a systematic process driven by senior leaders embroiling all levels and parts of the organization. Furthermore, the definition stresses accountability and provides parameters for outcomes that could be monitored and tracked.

The conceptual framework in Figure 2 provides a pictorial representation of workplace integration of IENs and reflects the emphases that emerged in this research. When IENs work in an organization that is committed to equity, diversity and inclusion, their integration is facilitated. The organizational leadership’s application of the equity lens to all decisions about resources and policies translates into practices that strive for equitable outcomes for IENs. Diversity in the organization’s workforce is a major facilitator and it is achieved by HR departments championing appropriate recruitment and retention strategies. The relevance of and responsiveness to the external community are also reflected through the organization’s active engagement. The framework highlights that organizations have to continue to be diligent as there will be various pitfalls along the way that need to be dealt with. The framework clarifies that IENs have moved beyond transition and are being “Canadian nurses with international experiences,” who are progressing on their leadership journey while still persevering in overcoming challenges.

8. Limitations

This research is a qualitative, instrumental case study involving a single organization within a specific community context. There are no expectations of replicating this study as this is a foundational work exploring the concept of workplace integration of IENs. However, it is conceivable that this study may lead to a program of research with multiple sites. A thick description of the organizational context is provided so that the reader who is interested can reach a conclusion about transferability to another similar situation.

9. Conclusions

Using a qualitative case study approach informed by critical social theory, this research has addresses gaps in knowledge by offering a conceptual framework and definition of workplace integration of IENs based on the perspectives of IENs and other stakeholders. This research shifts the focus to IENs who are in a later, post-transition phase and clarifies workplace integration as a two-way process to include how the employer organization influences the integration of IENs. This outlook is well overdue other researchers are invited to further test the conceptual framework and definition emerging from this study. The findings and analysis presented in this paper highlight that beyond the challenges of the earlier transition phase, IENs progress on their leadership journey. When workplaces are committed to facilitating integration, IENs do not merely survive but they have capacity to thrive and positively influence nursing and healthcare practice.

Author Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, Elizabeth, and Annette Kennedy. 2006. Positive Practice Environments—Key Considerations for the Development of a Framework to Support the Integration of International Nurses. Geneva: International Centre on Nurse Migration. [Google Scholar]

- Adeniran, Rita K., Mary Ellen Smith-Glasgow, Anand Bhattacharya, and X. U. Yu. 2013. Career advancement and professional development in nursing. Nursing Outlook 61: 437–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, Pamela, and Susan Jack. 2008. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report 13: 544–59. [Google Scholar]

- Blythe, Jennifer, and Andrea Baumann. 2009. Internationally educated nurses: Profiling workforce diversity. International Nursing Review 56: 191–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeault, Ivy Lynn, Elena Neiterman, Jane Lebrun, Ken Viers, and Judi Winkup. 2010. Brain Gain, Drain & Waste: Experiences of Internationally Educated Health Professionals in Canada. Ottawa: University of Ottawa. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, James. 2006. The impact of global nursing migration on health services delivery. Policy Politics Nursing Practice 7: 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2012. Regulated Nurses: Canadian Trends, 2007 to 2011. Ottawa: CIHI, Available online: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productSeries.htm?pc=PCC449 (accessed on 9 February 2018).

- Cho, Sung-Hyun, Leah E. Masselink, Cheryl B. Jones, and Barbara A. Mark. 2011. Internationally Educated Nurse Hiring: Geographic Distribution, Community and Hospital Characteristics. Nursing Economics 29: 308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choiniere, Jacqueline, and Judith A. Macdonnell. 2012. Challenging Everyday Violence Taking Race & Gender Into Account: Policy Implications. Canadian Diversity 9: 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 2012. Landing Statistics for Immigrants with National Occupations Category of Nurse, Nurse Manager/Educator, Special Data Request by CARE Centre for IENs.

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design—Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Creticos, Peter A., James M. Schultz, Amy Beeler, and Eva Ball. 2006. The Integration of Immigrants in the Workplace. Chicago: Institute for Work and the Economy. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Linda, Louise Racine, Sonia Udod, S. Maposa, and Susan Fowler-Kerry. 2014. Exploring the Integration Experiences of IENs and their Canadian Educated Colleagues and Nurse Managers. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of Education and Support of IENs, Toronto, ON, Canada, November 27. [Google Scholar]

- Galabuzi, Grace-Edward. 2012. Employment Equity as “Felt Fairness”: The Challenge of Building an Inclusive Labour Market. Canadian Diversity 9: 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish, Kate, and Vanessa Griffith. 2003. Integration of overseas Registered Nurses: Evaluation of an adaptation programme. Journal of Advanced Nursing 45: 579–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Resources and Services Administration. 2010. The registered nurse population: Findings from the 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. Available online: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/health-workforce/rnsurvey/2008/nssrn2008.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2018).

- His Highness the Aga Khan. 2010. LaFontaine-Baldwin Lecture. Available online: http://www.akdn.org/Content/1018 (accessed on 9 February 2018).

- House, Robert, Mansour Javidan, Paul Hanges, and Peter Dorfman. 2002. Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: An introduction to project GLOBE. Journal of World Business 37: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxby, Heather, Verla Fortier, Nancy Brown, Gail Yardy, and Jennifer Blythe. 2010. Internationally educated nurses: Building capacity for clinical/nurse managers. Nursing Leadership 23: 132–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingma, Mireille. 2007. Nurses on the move: A global overview. Health Services Research 42: 1281–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konu, Anne, and Elina Viitanen. 2008. Shared leadership in Finnish social and health care. Leadership in Health Services 21: 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. 1985. Establishing worthiness. In Naturalistic Inquiry. Edited by Yvonna S. Lincoln and Egon G. Guba. Beverly Hills: SAGE Publications, pp. 289–331. [Google Scholar]

- Lukes, S. 2005. Power: A radical View. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, Linda. 2012. Disarming Culture Traps. Canadian Diversity 9: 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Sandra, and Marion McGuire. 2005. The internationally educated nurse: Well-researched and sustainable programs are needed to introduce internationally educated nurses to the culture of nursing practice in Canada. Canadian Nurse 101: 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Kwame. 2015. Racism, Health and What You Can Do About It, Black History Month Speech at Toronto Public Health.

- Minors, A., A. Mukherjee, and G. Posen. 1995. Employment Equity for Racially Visible and Aboriginal Peoples—Laying the Groundwork for Change. Ottawa: Canadian School Boards Association. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Janice. 2018. Reframing Rigor in Qualitative Inquiry. In The Sage handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service Employers and University of Bradford. 2005. Positive Action: Key Success Factors & Best Practices. Available online: www.nhsemployers.org (accessed on 9 February 2018).

- Newton, Stacey, Jennifer Pillay, and Gina Higginbottom. 2012. The migration and transitioning experiences of internationally educated nurses: A global perspective. Journal of Nursing Management 20: 534–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussbaum, Martha. 2005. Women’s capabilities and social justice. Journal of Human Development 1: 219–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkouda, M. 2014. The Immigrant Advantage Leveraging Immigrants for Innovation and Competitiveness. Paper presented at Canadian Immigration Conference 2014: Enhancing Canada’s Immigration System—From Invitation to Integration, Toronto, ON, Canada, May 14. [Google Scholar]

- Premji, Stephanie, and Josephine B. Etowa. 2014. Workforce utilization of visible and linguistic minorities in Canadian nursing. Journal of Nursing Management 22: 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primeau, Marie-Douce, François Champagne, and Mélanie Lavoie-Tremblay. 2014. Foreign-Trained Nurses’ Experiences and Socioprofessional Integration Best Practices—An Integrative Literature Review. The Health Care Manager 35: 245–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghuram, Parvati. 2007. Interrogating the language of integration: The case of internationally recruited nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramji, Zubeida, and Josephine Etowa. 2014. Current Perspectives on Integration of Internationally Educated Nurses into the HealthCare Workforce. Humanities and Social Sciences Review 3: 225–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ramji, Zubeida, and Josephine Etowa. 2015. Towards a Conceptual Framework for Workplace Integration of Internationally Educated Nurses Management Education. An International Journal 15: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ramji, Zubeida, and Josephine Etowa. Unpacking "two-way" workplace integration of internationally educated nurses. Nursing Inquiry, Under Review.

- Romaniuk, D. 2015. Two Q’s-Quality Workforce for Quality Care: Integrating Diverse Staff. Paper presented at Health Care Employment Summit, Ontario Hospital Association, Toronto, Canada, November 17. [Google Scholar]

- Roscigno, Vincent J., Sherry Mong, Reginald Byron, and Griff Tester. 2007. Age discrimination, social closure and employment. Social Forces 86: 313–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, Jordana, Kathleen M. Hegadoren, and Linda Ogilvie. 2012. Career advancement and educational opportunities: Experiences and perceptions of internationally educated nurses. Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership 25: 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwood, Gwen D., and Franklin A. Shaffer. 2014. The role of internationally educated nurses in a quality, safe workforce. Nursing Outlook 62: 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sochan, Anne, and Mina. D. Singh. 2007. Acculturation and socialization: Voices of internationally educated nurses in Ontario [corrected] [published erratum appears in INT NURS REV 2007 sep;54(3):301]. International Nursing Review 54: 130–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stake, Robert E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oakes: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, Robert E. 2006. Multiple Case Study Analysis. New York: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tregunno, Deborah, Suzanne Peters, Heather Campbell, and Sandra Gordon. 2009. International nurse migration: U-turn for safe workplace transition. Nursing Inquiry 16: 182–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations High Commission on Refugees. 2005. Executive Committee Conclusion on Local Integration. No. 104 (LVI). Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/4357a91b2.html (accessed on 11 February 2018).

- Weber, Max. 1978. Domination by economic power and by authority. In Economy and Society. Edited by G. Roth and C. Wittich’s. Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 941–48. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, Nan. 2012. Introduction. Canadian Diversity 9: 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, Rebecca M., and Jennifer W. Foster. 2013. Barriers to participation in governance and professional advancement. Journal of Nursing Administration 43: 409–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winklemann-Gleed, Andrea. 2006. Migrant Nurses: Motivation, Integration and Contribution. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).