Abstract

The entrepreneurial performance of new ventures operating within the sustainable open innovation paradigm remains underexplored, particularly in terms of how specific sustainability-oriented practices translate into measurable performance outcomes. Prior research has largely examined sustainability, entrepreneurship, and open innovation in isolation, offering limited empirical evidence on their combined effects at the early venture stage. To address this gap, this study analyzes panel data from 407 new ventures incubated in science and technology parks, employing regression-based panel data analysis to examine the relationships between sustainable practices, open innovation engagement, and entrepreneurial performance. The findings suggest that new ventures widely adopt sustainable materials and energy as key strategies, which significantly influence entrepreneurial performance. In contrast, support from local communities does not have a statistically significant impact. Among the sociodemographic factors tested, only the number of years participating in open innovation networks shows a significant effect on entrepreneurial performance. Theoretically, this study advances sustainable open innovation literature by empirically integrating sustainability practices into entrepreneurship performance models. From a managerial perspective, the findings offer actionable insights for entrepreneurs and incubator managers, highlighting which sustainability strategies and network engagements are most likely to yield performance benefits in new ventures.

1. Introduction

Open innovation has emerged as a critical paradigm shift in the way businesses approach innovation, especially for new ventures. Rather than relying solely on internal resources and expertise, open innovation emphasizes the importance of collaborating with external partners, including customers, suppliers, universities, and even competitors, to co-create value (Chesbrough, 2003). In recent years, the open innovation paradigm has evolved to meet society’s concerns about sustainability. In discussions about open innovation, sustainability is indeed a crucial but often overlooked aspect. Open innovation, which emphasizes rapid product development and market entry through external collaborations and idea sharing, seems to prioritize speed and agility (Satar et al., 2025). This focus can appear at odds with the principles of sustainability, which often require more deliberate and systemic changes. However, this apparent contradiction underscores an important point in today’s business environment: integrating sustainability into open innovation processes is not only necessary but also beneficial. Balancing the urgency of open innovation with the thoughtful implementation of sustainable practices can lead to solutions that are both innovative and responsible (Gonçalves et al., 2024).

The emergence of sustainable open innovation stems from a confluence of factors reflecting shifts in societal, economic, and environmental paradigms. Firstly, the recognition of pressing global challenges, such as climate change, resource scarcity, and social inequality, has necessitated a reevaluation of traditional innovation models (Matos et al., 2022). These challenges demand collaborative, cross-sectoral solutions that go beyond the capabilities of any single organization or sector. Secondly, advancements in communication technology have facilitated greater connectivity and information sharing among individuals and organizations worldwide. This connectivity has democratized access to knowledge and expertise, enabling widespread participation in the innovation process. Sustainable open innovation refers to an approach in which organizations purposefully open their innovation processes to internal and external actors to co-create solutions that integrate economic value creation with environmental and social sustainability objectives. As articulated by Kimpimäki et al. (2022), this paradigm emphasizes the strategic use of collaborative networks to access diverse knowledge, technologies, and resources, while ensuring that innovation outcomes contribute not only to business growth but also to the mitigation of environmental impacts and the generation of broader societal value.

Studies such as Habiyaremye (2020) and Milana and Ulrich (2022) highlight that open innovation practices in firms can promote sustainability by enabling collaboration, knowledge sharing, and innovation across organizational boundaries. Kurniawati et al. (2022) add this approach also has the potential to be adopted by SMEs and Harsanto et al. (2022) value its potential for adoption by social enterprises. There are also studies that look to exploit the benefits of this approach in specific processes of an organization such as the management of a supply chain (Viale et al., 2022) and its application to specific industries such as the food industry (Venturelli et al., 2022) and the empirical exploitation of its results considering case studies such as the study carried out by Lippolis et al. (2023) at Enel. Building on this stream of research, attention has increasingly shifted toward understanding not only how sustainable open innovation is adopted across organizational contexts, but also how it translates into entrepreneurial outcomes. In this regard, entrepreneurial performance can be seen as the multidimensional capacity of a venture to transform innovation-related inputs into economic, innovative, and growth-oriented results. However, despite the growing body of literature on open innovation and sustainability, the implications of sustainable open innovation for the entrepreneurial performance of new ventures remain insufficiently theorized and empirically examined. Existing studies predominantly focus on established firms or large incumbents, where organizational resources, absorptive capacity, and governance structures differ substantially from those of nascent ventures. Moreover, much of the empirical evidence relies on qualitative case studies, sector-specific analyses, or single-industry contexts, which, while insightful, limit the generalizability of findings and offer only partial explanations of performance outcomes. Research addressing SMEs and social enterprises has largely emphasized adoption potential rather than performance implications, leaving unanswered questions about whether and how sustainability-oriented open innovation strategies translate into tangible entrepreneurial success at early stages of firm development. This study addresses this research gap by using a panel of 407 companies incubated in science parks that adopt open innovation practices in the development of their products or processes aimed at sustainable innovation. Accordingly, the research goal of this study is to analyze the entrepreneurial performance of new ventures within the sustainable open innovation paradigm, focusing on how sustainability-oriented strategies and sociodemographic factors influence their success. The theoretical foundation of this study draws primarily on the Resource-Based View (RBV) and open innovation theory. From an RBV perspective, sustainability-oriented practices, such as the adoption of sustainable materials and renewable energy, are considered valuable, rare, and difficult-to-imitate resources that can generate competitive advantage and enhance entrepreneurial performance. Open innovation theory complements this view by emphasizing the strategic role of external knowledge and collaborative networks in expanding a venture’s resource base and innovation capacity. By integrating these lenses, the study conceptualizes entrepreneurial performance as an outcome that emerges from the interaction between internal sustainability-oriented resources and externally leveraged capabilities through open innovation networks.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Initially, a theoretical contextualization is provided to explore the relevance of topics related to sustainable open innovation and entrepreneurial performance. After that, the research hypotheses that guide this study are developed. Next, the methodology adopted in this study is presented with the characterization of the sample and the measures that support each construct. The results are then presented, indicating the hypotheses accepted and rejected. After this, the results are discussed considering their relevance to the evolution of literature in the field. Finally, the main conclusions of the work are listed, taking the opportunity to make suggestions for future work.

2. Theoretical Framework

Literature has given increasing importance to new ventures and their role in economic growth and innovation ecosystems. Rather than treating ventures as isolated entities, recent scholarship converges on the view that their performance and survival are deeply embedded in collaborative innovation structures. New ventures often face resource constraints, including limited financial capital, human capital, and expertise. Across studies, there is broad agreement that open innovation acts as a compensatory mechanism for these constraints, as collaboration with external partners enables access to specialized skills, technologies, and resources that ventures may not have internally, thereby accelerating innovation processes and strengthening competitive positioning (Flamini et al., 2022; Toroslu et al., 2023; Wyrwich et al., 2022). This perspective aligns with ecosystem-based views of entrepreneurship, which emphasize interdependence rather than firm-level self-sufficiency.

Similarly, open innovation enables new ventures to leverage external networks and ecosystems to gain market insights and validation for their products or services. Empirical studies consistently suggest that early stakeholder engagement reduces market uncertainty by aligning innovation outputs with real customer needs. This is achieved by engaging customers, industry experts, and other stakeholders throughout the innovation process, which improves understanding of market preferences and trends (Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2022; Siriwong et al., 2024). This market-oriented logic complements resource-based arguments by showing that open innovation supports not only capability building but also demand-side validation. Furthermore, Bigliardi et al. (2021) emphasize speed-related advantages, noting that open innovation facilitates faster time-to-market through access to existing technologies, infrastructure, and distribution channels.

Open innovation fosters a relational orientation that is particularly valuable for new ventures operating in dynamic and uncertain environments, as it enables them to access and integrate external knowledge beyond organizational boundaries. Rather than just emphasizing collaboration, recent studies such as those by Arsanti et al. (2024) and Kim et al. (2024) underscore the knowledge recombination and boundary-spanning functions of open innovation, through which diverse expertise is selectively absorbed and transformed into actionable solutions. Furthermore, Hofstetter et al. (2021) show that engaging with heterogeneous external actors enhances not only creative problem-solving but also the contextual fit and practical relevance of innovative outcomes. These findings resonate with relational and social capital perspectives, which stress that trust, transparency, and shared norms are critical enablers of sustained collaboration (Antonelli et al., 2026; Brockman et al., 2018). Accordingly, open innovation is not merely a structural arrangement but a governance logic that mitigates uncertainty and coordination risks inherent in entrepreneurial experimentation.

The relationship between open innovation and sustainable open innovation reflects an important conceptual evolution in innovation theory. Initially, open innovation primarily emphasized efficiency, speed, and knowledge inflows to enhance competitiveness. However, more recent contributions converge on the argument that these efficiency-oriented models are insufficient in the face of escalating environmental and social challenges. As global awareness of sustainability issues increased, scholars such as Ferlito and Faraci (2022) and Mignon and Bankel (2023) observed a shift toward integrating sustainability imperatives into innovation processes. This transition does not replace open innovation but extends it, giving rise to sustainable open innovation, which combines diverse external inputs with explicit environmental and social objectives.

Sustainable open innovation management thus emerges as a strategic approach that leverages external ideas, technologies, and resources while systematically incorporating environmental, social, and economic considerations. The literature shows strong convergence on its strategic relevance, particularly in complex and stakeholder-rich environments. First, sustainable open innovation management fosters collaboration and knowledge sharing among customers, suppliers, partners, and even competitors, thereby expanding the pool of expertise and perspectives available for innovation. Empirical evidence suggests that this multi-actor engagement enhances the likelihood of developing environmentally friendly products, processes, and business models, reinforcing both innovation quality and legitimacy (Dorrego-Viera et al., 2025; Maresova et al., 2022; Peñarroya-Farell et al., 2023). Second, sustainability-oriented open innovation enables organizations to identify and exploit emerging market opportunities driven by rising demand for eco-friendly solutions (Sheth & Parvatiyar, 2020; Venturelli et al., 2022). Costa and Moreira (2022) further argue that this proactive orientation strengthens organizational resilience, as it mitigates regulatory, reputational, and operational risks while positioning firms to capture first-mover advantages. Thus, sustainability is increasingly framed not as a constraint on innovation but as a catalyst for strategic renewal.

Current literature on the entrepreneurial performance of new ventures reflects a similar broadening of analytical scope. Traditional research emphasizes financial outcomes, growth rates, and market share as core indicators of performance (Alqahtani et al., 2025). While these metrics remain central, scholars increasingly acknowledge their limitations in capturing the multidimensional nature of venture success. A growing stream of research integrates sustainability into entrepreneurial performance frameworks, examining how environmental and social considerations shape value creation processes. Rather than treating sustainability as an external outcome, recent studies position it as an integral component of performance, influencing customer satisfaction and brand reputation (Rosário et al., 2024). This shift signals a theoretical convergence between entrepreneurship, innovation, and sustainability research, underscoring the need for integrative models that reflect both short-term performance and long-term societal impact.

As businesses increasingly acknowledge the importance of incorporating sustainability into their innovation strategies, evaluating the performance of new ventures in this context offers valuable insights into their effectiveness and long-term potential. In this study, sustainable open innovation is conceptualized as a process-level construct, encompassing the set of practices through which new ventures purposefully engage external actors, knowledge flows, and collaborative networks to develop innovations that integrate environmental and social considerations. These practices reflect how innovative activities are organized and executed, rather than the results they generate. By contrast, entrepreneurial performance is treated as an outcome-level construct, capturing the extent to which new ventures translate these sustainability-oriented open innovation processes into measurable economic, innovative, and growth-related results. Evaluating entrepreneurial performance in the context of sustainable open innovation, therefore, does not conflate processes with outcomes but instead assesses the effectiveness of specific innovation practices in delivering tangible venture-level benefits. This distinction enables a clearer analytical separation between how new ventures pursue sustainable innovation and how effectively these efforts perform in entrepreneurial terms. Accordingly, the assessment of entrepreneurial performance serves to gauge how effectively new ventures balance the dual objectives of rapid innovation and sustainability, while recognizing that sustainable open innovation operates as an antecedent mechanism shaping these outcomes rather than as a performance indicator itself.

3. Research Hypothesis Development

From the perspective of RBV theory, entrepreneurial performance is driven by the firm’s ability to acquire and leverage valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) resources (Colombo et al., 2024; Kellermanns et al., 2016). RBV suggests that firms can achieve a competitive advantage by utilizing unique and valuable resources. Sustainable materials can serve as strategic resources that enhance product differentiation. As recognized by Qayyum et al. (2024), Organizations are increasingly integrating principles of eco-design, life cycle assessment, and resource efficiency into their innovation processes to minimize environmental impact. This may involve developing products with lower carbon footprints using renewable materials. Creating a production process that minimizes harm to the environment requires careful consideration of materials used at every stage. This can be done using renewable resources like sustainably sourced wood or recycled materials. Furthermore, throughout the production process, Mesa et al. (2022) suggest prioritizing durability and longevity in product design reduces the need for frequent replacements, ultimately decreasing resource consumption and waste generation. Therefore, as businesses engage in open innovation with a sustainability mindset, they benefit from increased adaptability and resilience. Companies can tap into a broader spectrum of ideas and innovations from external sources, enhancing their ability to develop unique products and services. According to Neves et al. (2022), this approach not only aligns with global sustainability goals but also attracts environmentally conscious consumers, opening new market opportunities. Moreover, Yoo et al. (2019) point out that the focus on sustainability can drive cost reductions through the efficient use of resources, improving profitability.

H1.

The use of sustainable materials in open innovation paradigm has a positive impact on entrepreneurial performance.

According to RBV, sustainable energy can be considered a strategic capability that enhances efficiency, reduces operational costs, and aligns with sustainability-driven market demands (Aasa et al., 2025; Khanra et al., 2022; Kowalska et al., 2025). Efficient utilization of energy and water resources is vital in ensuring sustainable and responsible production processes. Adopting a holistic approach, various strategies can be implemented to optimize energy and water usage throughout the production lifecycle. Investing in energy-efficient equipment is a foundational step. Businesses can significantly reduce their carbon footprint while also cutting down operational costs by employing machinery and technology specifically designed to minimize energy consumption (Dogan et al., 2022; Roemer et al., 2023). Furthermore, integrating renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, or hydroelectric power into production facilities can further diminish reliance on fossil fuels, contributing to a greener and more sustainable operation (Østergaard et al., 2023). Therefore, it is important to continuously track energy and water usage, which allows production managers to make informed decisions to optimize processes and minimize waste. This strategic focus on resource efficiency and sustainability ultimately drives better entrepreneurial performance by improving profitability, enhancing market positioning, and fostering long-term business resilience.

H2.

The use of sustainable energy in open innovation paradigm has a positive impact on entrepreneurial performance.

In the open innovation paradigm, firms leveraging external partnerships may gain access to sustainable materials and cutting-edge renewable energy technologies. Currently, many organizations recognize the importance of giving back to their local communities, both financially and through non-financial means. Financial contributions often take the form of donations to local charities, sponsorships of community events, or grants to support local initiatives. Non-financial contributions are equally vital and can include volunteering programs where employees donate their time and skills to community projects or initiatives. The importance of these actions has become even more evident during the COVID-19 pandemic (Almeida & Wasim, 2023). Furthermore, some organizations establish partnerships with local community organizations or government agencies to collaboratively address systemic social and environmental challenges. Through such partnerships, organizations can leverage shared resources and complementary expertise to co-create sustainable solutions to issues facing local communities (Julsrud, 2023). Beyond their instrumental value, these collaborations can be theoretically understood through the lenses of stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984) and social capital theory (Putnam, 1993). From a stakeholder perspective, local communities represent salient stakeholders whose support can enhance organizational legitimacy, reduce uncertainty, and facilitate access to critical resources, thereby strengthening entrepreneurial performance. Engaging with community stakeholders allows new ventures to align their innovative activities with societal expectations, fostering trust and long-term relational stability. Similarly, social capital theory suggests that repeated interactions and collaborative ties with community actors generate relational assets such as trust, shared norms, and reciprocity, which can lower transaction costs and improve coordination. For new ventures, particularly those operating within sustainable open innovation ecosystems, such social capital may enhance the effectiveness of innovation processes by improving knowledge exchange, easing market acceptance, and accelerating the diffusion of sustainable products or services. Consequently, community support is expected to function not merely as contextual goodwill but as a strategic resource that can positively influence entrepreneurial performance by reinforcing both legitimacy and resource mobilization.

H3.

The support of the local community in open innovation paradigm has a positive impact on entrepreneurial performance.

This study also seeks to account for key sociodemographic characteristics that may help explain variation in entrepreneurial performance, not as primary explanatory mechanisms but as control expectations that capture background conditions influencing venture outcomes. It is assumed that entrepreneurial performance is influenced by a multitude of factors that interact in complex ways. Studies such as Rosado-Cubero et al. (2022) and Yangailo and Qutieshat (2022) expose that entrepreneur’s characteristics determine their ability to persist in the face of adversity, maintain optimism, and adapt to changing market conditions. Overall, these characteristics collectively influence the strategic decisions performed by entrepreneurs. Age often correlates with accumulated experience, skills, and networks, which can positively influence entrepreneurial performance (Zhao et al., 2021). Older entrepreneurs may possess greater industry knowledge, managerial experience, and financial stability, enabling them to navigate challenges more adeptly and make informed decisions. Conversely, younger entrepreneurs may bring fresh perspectives, innovative ideas, and adaptability to their ventures, potentially enhancing performance through agility and creativity. Secondly, gender profoundly impacts entrepreneurial performance due to societal norms, access to resources, and differential experiences. It is addressed in Ahmetaj et al. (2023) that women entrepreneurs often face systemic barriers such as limited access to funding, networks, and mentorship opportunities, affecting their performance outcomes. Moreover, gender stereotypes and biases can influence perceptions of competence and leadership, impacting entrepreneurial success (Sarango-Lalangui et al., 2023). Addressing gender disparities in entrepreneurship through targeted support, policies, and initiatives can unlock the untapped potential of female entrepreneurs, contributing to economic growth and innovation.

H4.

Age is a determining factor in characterizing entrepreneurial performance in the context of open innovation paradigm.

H5.

Gender is a determining factor in characterizing entrepreneurial performance in the context of open innovation paradigm.

Although academic degrees are valuable assets for entrepreneurs, it is essential to acknowledge that they are not the sole determinants of entrepreneurial success. They provide individuals with essential knowledge and skills that are crucial for starting and managing a business effectively. Through academic programs, entrepreneurs gain insights into various aspects of business operations such as finance, marketing, management, and strategy (Bauman & Lucy, 2021). This foundational knowledge can enhance their decision-making abilities, problem-solving skills, and overall competency in navigating the complexities of entrepreneurship.

H6.

Academic degree is a determining factor in characterizing entrepreneurial performance in the context of open innovation paradigm.

Finally, open innovation networks serve as powerful enablers for entrepreneurs, offering access to external knowledge, technological advancements, and strategic partnerships that help new ventures to growth (Gay, 2014; Huang & Zhou, 2025). The collaborative landscape offered by open innovation networks provides fertile ground for overcoming resource constraints and accelerating product development. Therefore, entrepreneurs who actively participate in open innovation networks can drive their performance. Furthermore, Arsanti et al. (2024) recognize the role of these networks in facilitating knowledge exchange and strategic alliances that would be difficult to achieve in isolation, enabling ventures to respond more effectively to market demands and sustainability challenges. Moreover, it is expected that experienced entrepreneurs may be more adept at navigating the complexities of open innovation networks. They may have likely encountered various challenges and learned from past successes and failures, which enables them to make informed decisions and effectively leverage the resources available within the network. Furthermore, Flamini et al. (2022) advocate that experience fosters the development of social capital, which is essential for successful engagement in open innovation networks. Established relationships and trust networks built over time allow experienced entrepreneurs to access valuable information, expertise, and opportunities that might not be readily available to newcomers.

H7.

Years of experience in open innovation networks is a determining factor in characterizing entrepreneurial performance in the context of open innovation paradigm.

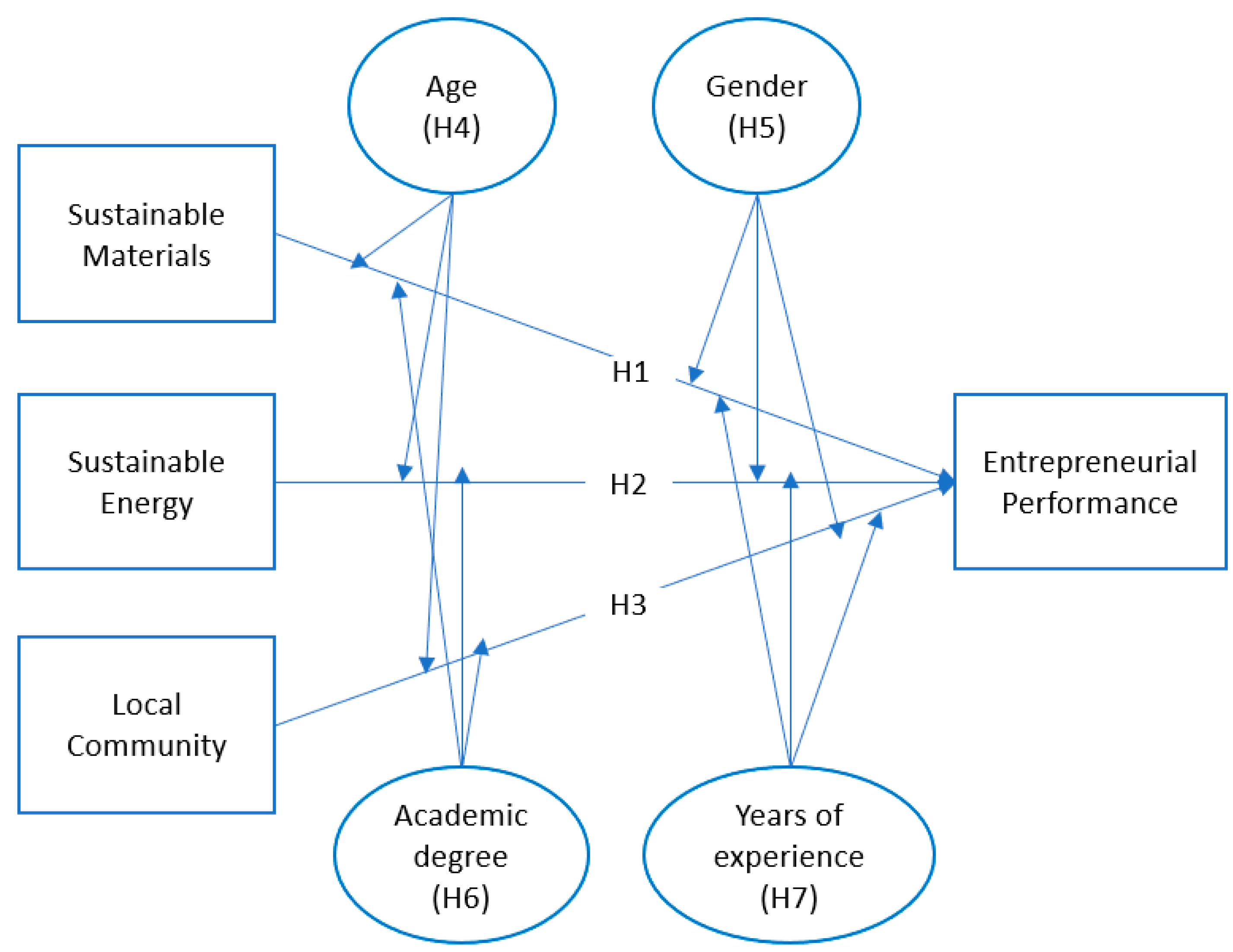

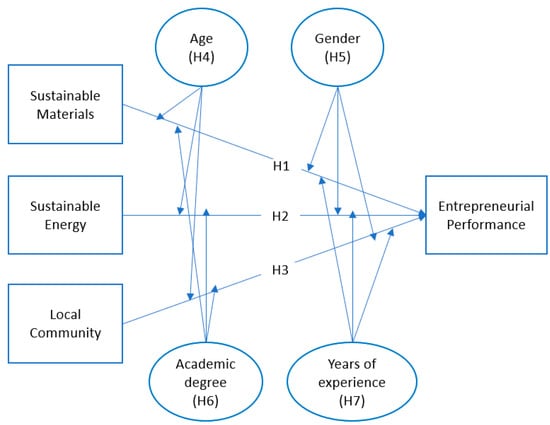

Figure 1 presents the research model developed in this study, illustrating the conceptual framework that links sustainable innovation practices to entrepreneurial performance. The model specifies the hypothesized relationships between the core constructs, reflecting the theoretical assumptions underpinning the analysis, while also incorporating control variables to account for alternative explanations.

Figure 1.

Research model with the established hypothesis and control variables.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample and Data Gathering

The sample consists of entrepreneurs (i.e., founders and co-founders) whose startups are in the process of incubation at Science and Technology Parks (STPs). The sample included venture companies that are incubated in STPs located in European Union countries (EU-28). The focus on EU-28 STPs is theoretically justified for several reasons. First, EU STPs operate within a highly supportive institutional and regulatory environment that actively promotes innovation, sustainability, and knowledge-based entrepreneurship, providing a rich context to study sustainable open innovation practices. Second, the EU represents a diverse set of economies and innovation ecosystems, allowing for broader generalizability of findings across multiple regulatory, cultural, and technological contexts, while maintaining comparability due to shared EU-wide policies and standards. Information on each park and incubated companies was obtained from the International Association of Science Parks (IASP). An STP is a structured program designed to support the development and growth of startup companies within the realm of science, technology, and innovation. These parks are often established by universities, research institutions, or governmental bodies to foster innovation and entrepreneurship in specific fields. A Google Forms questionnaire was constructed and structured according to the research hypotheses, which was sent to these companies and filled in by entrepreneurs participating in open innovation networks. Participants in such networks engage in various forms of collaboration, including joint research projects, technology licensing, and crowdsourcing initiatives.

This study adopts a cross-sectional research design, as data were collected at a single point in time from entrepreneurs participating in open innovation networks. The questionnaire was available online between October and December 2023. A reminder was sent to the companies at the beginning of December 2023. A total of 635 companies were contacted during this process. In the end, the survey received a total of 407 valid responses, as depicted in Table 1. The sample is essentially composed of individuals aged between 38 and 47. Despite this, there is good homogeneity in the gender distribution of the entrepreneurs. Most respondents (almost 90%) have at least a BSc. degree. Individuals with a PhD represent 21.62% of the sample. The distribution of experience of participating in collaborative innovation networks is fairly homogeneous, with only 13.51% of respondents indicating that they had less than a year’s experience. On the other hand, a total of 98 individuals (around 24.08%) indicated that they have more than 5 years of experience.

Table 1.

Distribution of samples.

4.2. Measures

The constructs used in this study have been previously validated in literature. The role of using sustainable materials and energy is presented by Kurniawati et al. (2022). Sustainable materials refer to resources, substances, or products that are responsibly sourced, manufactured, utilized, and disposed of in a manner that minimizes negative impacts on the environment, society, and economy. Key aspects of sustainable materials include environmental considerations such as reduced carbon footprint, conservation of natural resources, and minimal pollution throughout their life cycle. Sustainable energy refers to the production, distribution, and utilization of energy resources in a manner that meets present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Key components of sustainable energy include the utilization of renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, hydroelectric, geothermal, and biomass, which are naturally replenished and have minimal environmental impact compared to fossil fuels. Furthermore, the role of local communities in sustainable development is presented in studies such as Kapsalis and Kapsalis (2020) and Toniolo et al. (2023). These two studies share the same view of the role of local communities by indicating that local communities possess indigenous knowledge that has been passed down over generations, offering insights into sustainable practices suited to their environments. To capture this broad view of the role of local communities, the questionnaire included questions about their strategic knowledge of the startup and the financial and non-financial contribution the organization can make to local communities. Finally, entrepreneurial performance is measured according to the model proposed by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which considers its financial impact on the organization, the increase in its capacity for innovation, and employment (Ahmad & Hoffman, 2007). A uniform seven-level Likert scale was adopted to capture respondents’ answers. The full items included in the questionnaire are provided in Appendix A.

4.3. Statistical Procedures

The statistical procedures used in this study include descriptive analysis, correlational analysis, and inferential statistics. These techniques were used for different but complementary purposes. Descriptive analysis was adopted to comparatively explore the relative importance of the survey questions in both sustainable innovation practices and entrepreneurial performance outcomes. Correlational analysis was then used to explore the interdependence between the questions, and to explore the impact of these variables on entrepreneurial performance. Pearson’s correlational analysis is a fundamental statistical technique that measures the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two continuous variables (Holcomb, 2016). In observational studies, where it is not possible to manipulate independent variables, Pearson’s correlational analysis is essential for examining the relationships between variables. This approach also has the potential to be used in the development of predictive models, which makes it possible to identify which variables are most strongly associated with the response variable, helping in the selection of variables for inclusion in the model. Furthermore, a difference between means test was applied, considering each of the factors in the sample individually. As Asadoorian (2008) recognizes, this is a statistical analysis used to determine whether there is a significant difference between the means of two independent samples. This type of test is commonly carried out when you want to compare the means of two different populations or groups. These statistical techniques were calculated using IBM SPSS software v.27. Given that the data were collected through a single self-reported questionnaire, particular attention was paid to the potential risk of common method bias. To mitigate this risk, several procedural remedies were implemented at the design stage. These included assuring respondents of anonymity and confidentiality, and carefully wording items to minimize ambiguity and social desirability bias. Moreover, independent and dependent variables were presented in separate sections of the questionnaire to reduce respondents’ tendency to infer causal relationships. To further assess the presence of common method bias, a statistical diagnostic was conducted using Harman’s single-factor test (Harman, 1967). The results indicated that no single factor accounted for most of the variance, suggesting that common method bias is unlikely to pose a serious threat to the validity of the findings. Nevertheless, consistent with best practices in survey-based research, the potential influence of common method bias cannot be entirely ruled out and should be considered when interpreting the results. Finally, non-response bias was also examined to assess the representativeness of the sample. Following established methodological recommendations, early and late respondents were compared across key variables, assuming that late respondents may approximate non-respondents. The analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between these groups, indicating that non-response bias is unlikely to substantially affect the study’s conclusions.

It is also important to acknowledge the limitations of the statistical approach used in this study. The hypotheses were tested primarily using correlational analyses and mean difference tests, which allow for the examination of associations and group differences but do not support definitive causal inference. As the independent variables were not experimentally manipulated, the observed relationships indicate correlation rather than causation, and the possibility of unobserved confounding factors cannot be fully ruled out. Consequently, while these methods provide valuable insights into patterns, strengths, and differences among variables, the results should be interpreted as indicative of potential relationships rather than proof of causal effects.

5. Results

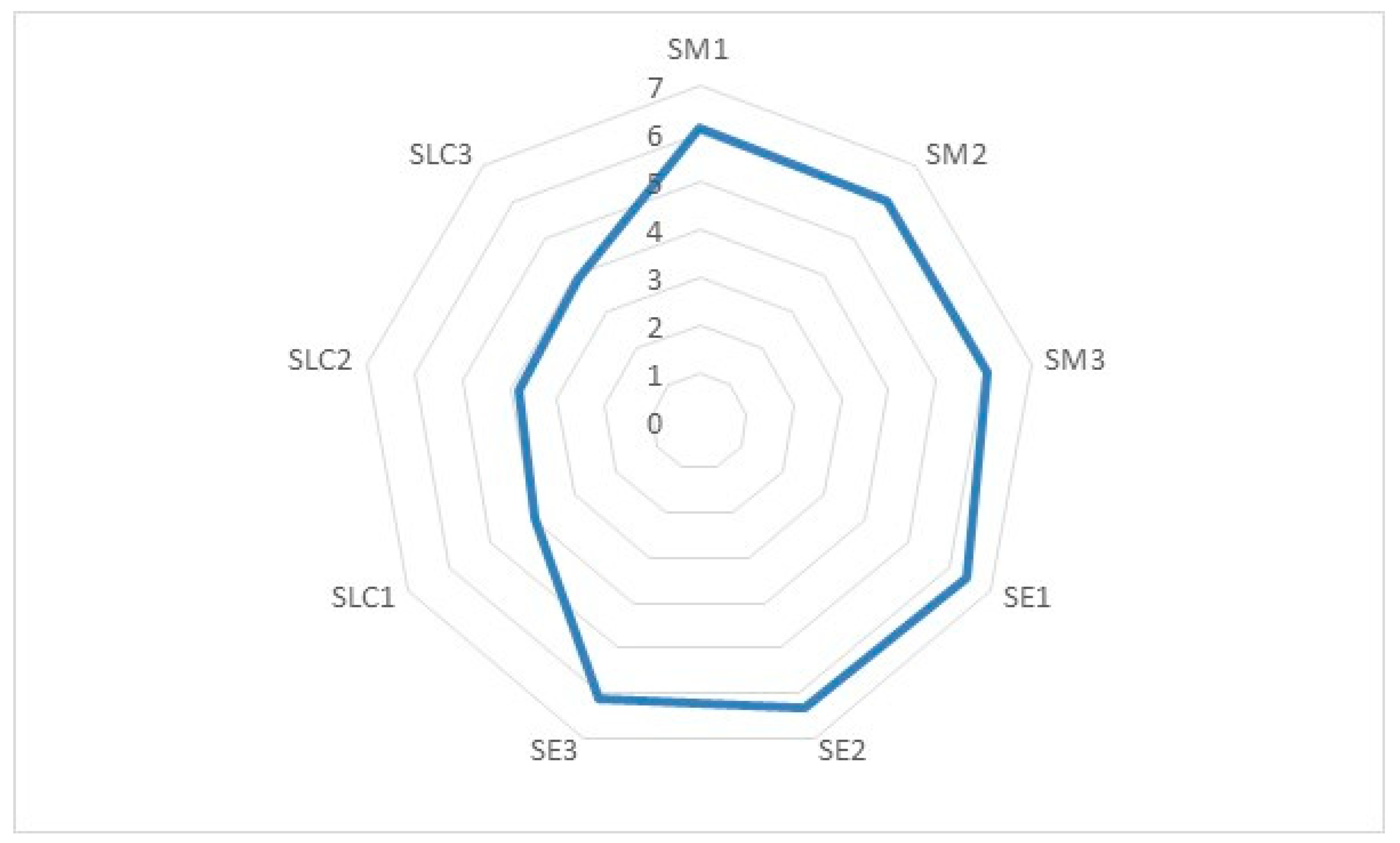

Figure 2 shows the relative importance of the variables relating to the sustainable open innovation paradigm construct. Each construct is made up of 3 variables so that SM1, SM2, and SM3 are part of the sustainable material (SM) construct, SE1, SE2, and SE3 belong to the sustainable energy (SE) construct, while SLC1, SLC2, and SLC3 are part of the sustainable local community (SLC) construct. The findings indicate that the first two constructs (mean = 6.073 and 6.301) have a much greater weight than the third construct (mean = 3.897).

Figure 2.

Relative weight of the constructs regarding the sustainable open innovation paradigm.

Subsequently, the individual behavior of each of the variables was explored in greater depth, as shown in Table 2. The organizations highlight the priority given to the use of sustainable energies and their adoption throughout the production process. The involvement of local communities is not a practice widely disseminated by the organizations (mean = 3.97 and SD = 1.464), which indicates a high dispersion of responses. Entrepreneurial performance (EP) is mainly evidenced by an increase in turnover (mean = 6.44), but this is not equally reflected in an increase in employability (mean = 4.01).

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of the sample.

Using SPSS Amos extension, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to investigate every measurement construct. To assess the accuracy of our model estimates in compliance with prescribed goodness-of-fit standards, such as the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), we employed maximum likelihood estimation approaches while conducting a measurement model analysis. GFI is equal to 0.913 and CFI is 0.939, which is higher than 0.90 as recommended by Hooper et al. (2008). Furthermore, Table 3 explores the Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC), Cronbach’s α, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO), and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. CITC is a measure used to evaluate the reliability and validity of individual items within a test or questionnaire. CITC higher than 0.30 is acceptable (Nurosis, 1994). Cronbach’s α is used to measure the internal consistency or reliability of a set of items, whose value should be higher than 0.7 (Taber, 2018). KMO measure evaluates how well the variables in a dataset correlated with each other, which is essential for determining whether factor analysis is appropriate (Field, 2009). Values of KMO close to 1 indicate that the variables have high correlations with each other and are suitable for factor analysis. Finally, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity examines whether the correlation matrix of a dataset is significantly different from an identity matrix (Field, 2009). Essentially, it tests whether the variables in the dataset are correlated enough to justify performing factor analysis. p-value below 0.05 indicates a significant result, which means that the correlation matrix is significantly different from the identity matrix. This suggests that the variables are correlated with each other to a degree that makes factor analysis appropriate.

Table 3.

Measurement model.

Furthermore, the correlational analysis presented in Table 4 shows that the strongest relationships are observed between the sustainable materials and sustainable energy constructs, with correlation coefficients predominantly in the high range (r ≈ 0.70–0.93), indicating a strong positive association in practical terms. In contrast, the correlations between the local community support construct and the remaining constructs are low and mostly non-significant (r < 0.35). Entrepreneurial performance is most strongly associated with sustainable energy and materials practices, particularly turnover growth and innovation capability, where the correlations range from moderate to strong (r ≈ 0.53–0.94), suggesting that these sustainability practices have not only statistical significance but also substantive practical relevance for the performance of new ventures. Accordingly, H1 and H2 are accepted. The components of entrepreneurial performance most correlated with these two constructs are turnover growth (EP1) and innovation capability (EP2). The correlation is weak to moderate for the performance of new ventures in increasing employability for all the other constructs. A p-value of less than 0.05 was not found for all the variables in this construct. Accordingly, H3 cannot be accepted.

Table 4.

Correlational analysis.

Finally, the hypothesis test carried out considering the profile of the entrepreneurs is shown in Table 5. The data indicates that entrepreneurial performance is only influenced by the factor relating to the number of years of involvement in open innovation networks. It can be concluded that greater exposure to open innovation networks increases the turnover and innovative capacity of a new venture. However, this factor is not associated with increased employability. In summary, the findings indicate that H4, H5, and H6 are rejected. While H7 can be partially supported with respect to the dimensions of increased turnover and innovative capacity, it is important to note that the hypotheses were tested using correlational and mean difference analyses, which limits the ability to draw definitive causal conclusions.

Table 5.

Impact of the profile of entrepreneurs on the performance of new ventures.

6. Discussion

The findings highlight the importance of adopting sustainable materials for new ventures. Incorporating sustainable materials into entrepreneurial ventures demonstrates a commitment to environmental stewardship, which resonates positively with consumers. In today’s socially conscious market, consumers are increasingly prioritizing eco-friendly products and services. Entrepreneurs can tap into this growing consumer demand by adopting sustainable materials. Therefore, new ventures can access previously untapped markets and diversify their customer portfolio, reducing dependency on a narrow customer segment. The findings obtained in this study align with those provided by Puumalainen et al. (2023), who note that this not only improves sales in the short term but also strengthens the business against market fluctuations and economic downturns in the long term.

The findings demonstrate that entrepreneurs can improve their financial performance by leveraging sustainable energy. Initially, sustainable energy can reduce operational costs for entrepreneurs. Abba et al. (2022) note that the adoption of sustainable energy can mitigate regulatory risks and enhance long-term business resilience. As governments introduce stricter environmental regulations and carbon pricing, fossil fuel–dependent businesses face rising compliance costs and legal risks. By adopting sustainable energy initiatives, entrepreneurs can mitigate regulatory exposure while fostering innovation and technological advancement. Consistent with sustainable materials practices, these initiatives are strongly correlated and often require new technologies and processes, enabling entrepreneurs to develop innovative solutions and strengthen their competitive position.

The connection between entrepreneurial performance through the lens of sustainable open innovation and the impact of entrepreneurial characteristics is intricate and multidimensional. Allal-Chérif et al. (2023) advocate that entrepreneurs engaged in sustainable open innovation need to adopt a mindset that embraces collaboration and adaptability. They often work with a variety of external partners, from other businesses to research institutions, and must be adept at incorporating diverse perspectives and technologies into their ventures. This integration is not just about acquiring new ideas but also about aligning these ideas with sustainable practices that benefit society and the environment. The complexity of this process is reflected in the multidimensional nature of entrepreneurial performance in this context. This study reveals that success in sustainable open innovation depends on several interrelated factors, including the ability to anticipate and respond to evolving markets, technologies, and regulatory environments, and the skill to align innovative efforts with broader sustainability objectives.

The findings indicate that years of experience in open innovation networks significantly influence entrepreneurial performance, whereas control variables such as age, gender, and academic degree do not exhibit a significant effect. Open innovation networks constitute environments in which collaboration, knowledge exchange, and resource sharing are central to entrepreneurial success. Prolonged engagement in such networks enables entrepreneurs to accumulate relational capital, develop collaborative skills, and gain insights into effectively integrating external knowledge, thereby enhancing performance. This experience also fosters adaptability and resilience, equipping entrepreneurs to navigate uncertainty and respond to changing market conditions. One critical manifestation of this adaptability is the ability to pivot, understood as making substantial adjustments to business models, products, or strategies in response to feedback and environmental signals. Burnell et al. (2023) emphasize that pivoting is essential for entrepreneurial survival in dynamic contexts. In sustainable entrepreneurship, achieving a balance between economic viability and environmental impact is particularly challenging, often requiring iterative adjustments. As highlighted by Gupta and Dharwal (2022) and Tekala et al. (2024), green entrepreneurship involves regulatory uncertainty, technological complexity, and evolving sustainability demands, making the capacity to pivot a key determinant of entrepreneurial performance.

Finally, these findings extend both the RBV and open innovation theory by demonstrating how sustainability-oriented practices function as strategically valuable resources and capabilities in new ventures. In line with RBV, the adoption of sustainable materials and renewable energy can be interpreted as the development of valuable, rare, and increasingly difficult-to-imitate resources that enhance entrepreneurial performance not merely through cost efficiencies, but through reputational capital, regulatory alignment, and innovation potential. Unlike traditional RBV applications that emphasize internally controlled assets, this study shows that such resources are often co-created through open innovation processes and embedded within broader innovation ecosystems. Furthermore, open innovation theory is extended by evidencing that prolonged engagement in open innovation networks enhances performance through experiential learning, relational capital, and adaptive capabilities, rather than through knowledge access alone. The significance of network experience underscores the role of dynamic, process-based capabilities (e.g., pivoting and knowledge integration) as key performance drivers in sustainable entrepreneurship.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Final Considerations

Entrepreneurial performance within the realm of sustainable open innovation paradigms represents a multifaceted and dynamic landscape. Entrepreneurial performance in sustainable open innovation is characterized by the ability of ventures to effectively leverage collaboration, knowledge sharing, and resource efficiency to drive innovation and create value. Unlike conventional entrepreneurship, where success is often measured solely in financial terms, the performance of ventures in this paradigm encompasses broader dimensions such as social and environmental impact alongside economic profitability. The findings indicate that the adoption of sustainable materials and energy are two integral elements of the strategy of new ventures and that they contribute to influencing entrepreneurial performance. On the opposite side, the support of local communities is not a determining element in the characterization of entrepreneurial performance, which reveals that their role is very diverse considering the typologies of each business and the open innovation networks that are created and participated in by the new ventures. Despite this, the number of years an entrepreneur has participated in open innovation networks improves their entrepreneurial performance, indicating the role these networks can play in the various phases of launching and growing a company in its early years.

7.2. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

The theoretical contributions offered by this study are multifaceted. Firstly, it extends the understanding of entrepreneurship beyond mere economic gains to encompass sustainability dimensions, emphasizing the importance of environmental and social impacts. By integrating sustainability into the entrepreneurial performance framework, this study contributes to advancing the field’s theoretical underpinnings, highlighting the significance of sustainable practices such as the adoption of sustainable materials and energy in new venture development. Furthermore, the study provides insights into the mechanisms through which sustainable entrepreneurship can create value for various stakeholders, including investors, customers, and society at large. By elucidating the pathways linking sustainability initiatives to entrepreneurial performance metrics, such as profitability, growth, and market competitiveness, it advances theoretical frameworks for evaluating the impact of sustainable practices on business outcomes. From a policy perspective, the findings of this study suggest the potential value of supportive frameworks and targeted incentives to encourage entrepreneurship in sustainable domains. Rather than prescribing specific policy actions, the results indicate that policymakers may consider measures such as tax incentives for sustainability-oriented ventures, funding schemes for green startups, or regulatory environments that facilitate open innovation and collaboration among stakeholders. Moreover, the evidence points to the possible relevance of education and training initiatives aimed at strengthening entrepreneurs’ skills and knowledge for operating within a sustainable open innovation paradigm, while acknowledging that the design and effectiveness of such interventions depend on broader institutional and contextual factors. Finally, we also recognize the practical contributions made by this study. It should be emphasized that the involvement of local communities should be explored from other perspectives for the evolution of a business that does not exclusively involve entrepreneurial performance. It is also recommended that entrepreneurs get involved in open innovation networks before launching their business, which can help them mitigate the difficulties of setting up a new business.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

This study has some limitations that it is important to address. Entrepreneurial performance is explored by considering the direct effects of sustainable materials, energy, and local community support. Indirect effects such as entrepreneurial leadership models or the adoption of knowledge management models are not considered. Therefore, in future work, we suggest applying structural equation models that can capture the impact of these indirect factors. Another future research direction is the inclusion of entrepreneur’s personality characteristics such as entrepreneur’s mindset, ambition, and approach to problem-solving, which may fundamentally drive the direction and success of their ventures. Also, the number of sociodemographic characteristics mapped in this study is limited to four factors. It is recognized that different demographic groups may face unique challenges and barriers to entrepreneurship, such as access to capital, networks, and support systems. By identifying these specific needs, this study could offer a more inclusive and supportive sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem. Future research could explore the impact of socioeconomic status (e.g., income, previous occupation, current and previous connections to education systems and scientific research centers) and geographic location (e.g., country, rural/urban local). It is also suggested to monitor the evolution of the new ventures considering changes in sociodemographic trends over time, which could in tracking societal shifts and informing long-term planning and decision-making processes.

In addition to the methodological limitations discussed above, this study is constrained by its cross-sectional research design and its focus on new ventures incubated in STPs within the EU. The cross-sectional nature of the data restricts the ability to capture temporal dynamics and causal mechanisms underlying sustainable open innovation, entrepreneurial learning, and performance evolution. From a theoretical perspective, this limitation calls for longitudinal research grounded in dynamic capabilities and learning theories to examine how sustainability-oriented resources and open innovation capabilities are developed, reconfigured, and potentially eroded over time. Furthermore, the EU-centric context—characterized by relatively mature innovation ecosystems, strong regulatory frameworks, and institutional support for sustainability—may condition the observed relationships. Future studies could extend stakeholder theory and institutional theory by comparing entrepreneurial performance under sustainable open innovation across different regional and institutional settings, such as emerging economies or less policy-driven innovation systems. Such comparative designs would deepen theoretical understanding of how institutional environments moderate the effectiveness of sustainable open innovation practices and help clarify the boundary conditions of the study’s findings.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Centro de Investigação e Desenvolvimento do of ISPGAYA (protocol code ISPG/RD/21, 21 October 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CITC | Corrected Item-Total Correlation |

| EP | Entrepreneurial Performance |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index |

| IASP | International Association of Science Parks |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| RBV | Resource-Based View |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Sustainable Energy |

| SLC | Sustainable Local Community |

| SM | Sustainable Material |

| STP | Science and Technology Park |

| VRIN | Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, and Non-substitutable |

Appendix A

The full items of the questionnaire:

| SM1 | The use of sustainable raw materials is a priority. |

| SM2 | Materials are used efficiently throughout the production process. |

| SM3 | Materials used in the entire production process do not harm the environment. |

| SE1 | The use of sustainable energy sources is a priority. |

| SE2 | Energy is used efficiently in the entire production process. |

| SE3 | Water is used efficiently in the entire production process. |

| SLC1 | Local communities are involved in innovation processes. |

| SLC2 | The organization contributes financially to support the activities of the local community. |

| SLC3 | The organization contributes non-financially to support the activities of the local community. |

| EP1 | My organization has experienced high turnover growth. |

| EP2 | My organization has increased innovation capability. |

| EP3 | My organization has increased employability. |

References

- Aasa, O. P., Phoya, S., Monko, R. J., & Musonda, I. (2025). Integrating sustainability and resilience objectives for energy decisions: A systematic review. Resources, 14(6), 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abba, Z. Y. I., Balta-Ozkan, N., & Hart, P. (2022). A holistic risk management framework for renewable energy investments. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 160, 112305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N., & Hoffman, A. (2007). A framework for addressing and measuring entrepreneurship. OECD-Entrepreneurship Indicators Steering Group. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/a-framework-for-addressing-and-measuring-entrepreneurship_243160627270.html (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Ahmetaj, B., Kruja, A. D., & Hysa, E. (2023). Women entrepreneurship: Challenges and perspectives of an emerging economy. Administrative Sciences, 13(4), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal-Chérif, O., Climent, J. C., & Berenguer, K. (2023). Born to be sustainable: How to combine strategic disruption, open innovation, and process digitization to create a sustainable business. Journal of Business Research, 154, 113379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F., & Wasim, J. (2023). The role of data-driven solutions for SMEs in responding to COVID-19. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 20(1), 2350001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, N., Uslay, C., & Yeniyurt, S. (2025). Entrepreneurial marketing and firm performance: Scale development, validation, and empirical test. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 33(7), 859–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, G. A., di Prisco, D., & Leone, M. I. (2026). Trust in open innovation: An integrated model based on a systematic literature review. R&D Management, 56, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsanti, T. A., Rupidara, N., & Bondarouk, T. (2024). Managing knowledge flows within open innovation: Knowledge sharing and absorption mechanisms in collaborative innovation. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2351832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadoorian, M. (2008). Essentials of inferential statistics. University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, A., & Lucy, C. (2021). Enhancing entrepreneurial education: Developing competencies for success. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B., Ferraro, G., Filippelli, S., & Galati, F. (2021). The past, present and future of open innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(4), 1130–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockman, P., Khurana, I. K., & Zhong, R. (2018). Societal trust and open innovation. Research Policy, 47(10), 2048–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnell, D., Stevenson, R., & Fisher, G. (2023). Early-stage business model experimentation and pivoting. Journal of Business Venturing, 38(4), 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). The era of open innovation. MIT sloan management review. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-era-of-open-innovation/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Colombo, M. G., Lucarelli, C., Marinelli, N., & Micozzi, A. (2024). Emergence of new firms: A test of the resource-based view, signaling and behavioral perspectives. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 20, 1153–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J., & Moreira, A. C. (2022). Public policies, open innovation ecosystems and innovation performance. Analysis of the impact of funding and regulations. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(4), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E., Hodžić, S., & Šikić, T. F. (2022). A way forward in reducing carbon emissions in environmentally friendly countries: The role of green growth and environmental taxes. Economic Research, 35(1), 5879–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrego-Viera, J. I., Urbinati, A., Hansen, E. G., & Lazzarotti, V. (2025). Open innovation for circular and sustainable business models: Case evidence from the bioeconomy sector. Innovation, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlito, R., & Faraci, R. (2022). Business model innovation for sustainability: A new framework. Innovation & Management Review, 19(3), 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS: Introducing statistical method. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Flamini, G., Pellegrini, M. M., Fakhar Manesh, M., & Caputo, A. (2022). Entrepreneurial approach for open innovation: Opening new opportunities, mapping knowledge and highlighting gaps. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 28(5), 1347–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, B. (2014). Open innovation, networking, and business model dynamics: The two sides. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R., Vlačić, B., González-Loureiro, M., & Sousa, R. (2024). The impact of open innovation on the environmental sustainability practices and international sales intensity nexus: A multicountry study. International Business Review, 33(5), 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M., & Dharwal, M. (2022). Green entrepreneurship and sustainable development: A conceptual framework. Materials Today: Proceedings, 49(8), 3603–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiyaremye, A. (2020). Knowledge exchange and innovation co-creation in living labs projects in South Africa. Innovation and Development, 10(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. (1967). A single factor test of common method variance. The Journal of Psychology, 35, 359–378. [Google Scholar]

- Harsanto, B., Mulyana, A., Faisal, Y. A., & Shandy, V. M. (2022). Open innovation for sustainability in the social enterprises: An empirical evidence. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(3), 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, R., Dahl, D. W., Aryobsei, S., & Herrmann, A. (2021). Constraining ideas: How seeing ideas of others harms creativity in open innovation. Journal of Marketing Research, 58(1), 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, Z. (2016). Fundamentals of descriptive statistics. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods (EJBRM), 6(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J., & Zhou, P. (2025). Open innovation and entrepreneurship: A review from the perspective of sustainable business models. Sustainability, 17(3), 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P. P., Fayolle, A., Jambrino-Maldonado, C., & de las Heras-Pedrosa, C. (2022). Open innovation for entrepreneurial opportunities: How can stakeholder involvement foster new products in science and technology-based start-ups? Heliyon, 8(12), e11897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julsrud, T. E. (2023). Sustainable sharing in local communities: Exploring the role of social capital. Local Environment, 28(6), 811–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsalis, T. A., & Kapsalis, V. C. (2020). Sustainable development and its dependence on local community behavior. Sustainability, 12(8), 3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermanns, F., Walter, J., Crook, T. R., Kemmerer, B., & Narayanan, V. (2016). The resource-based view in entrepreneurship: A content-analytical comparison of researchers’ and entrepreneurs’ Views. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanra, S., Kaur, P., Joseph, R. P., Malik, A., & Dhir, A. (2022). A resource-based view of green innovation as a strategic firm resource: Present status and future directions. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(4), 1395–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Roh, T., & Boroumand, R. H. (2024). Resource recombination perspective on open eco-innovation: Open innovation type, strategic orientation, and green innovation. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(7), 6207–6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimpimäki, J. P., Malacina, I., & Lähdeaho, O. (2022). Open and sustainable: An emerging frontier in innovation management? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, M., Gniadkowska-Szymańska, A., Misztal, A., & Comporek, M. (2025). Sustainable development of the energy sector in the context of socioeconomic cohesion in France, Germany, and Poland. Energies, 18(1), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, A., Sunaryo, I., Wiratmadja, I. I., & Irianto, D. (2022). Sustainability-oriented open innovation: A small and medium-sized enterprises perspective. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(2), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippolis, S., Ruggieri, A., & Leopizzi, R. (2023). Open innovation for sustainable transition: The case of Enel “open power”. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(7), 4202–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresova, P., Javanmardi, E., Maskuriy, R., Selamat, A., & Kuca, K. (2022). Dynamic sustainable business modelling: Exploring the dynamics of business model components considering the product development framework. Applied Economics, 54(51), 5904–5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, S., Viardot, E., Sovacool, B. K., Geels, F. W., & Xiong, Y. (2022). Innovation and climate change: A review and introduction to the special issue. Technovation, 117, 102612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, J., Gonzalez-Quiroga, A., Aguiar, M. F., & Jugend, D. (2022). Linking product design and durability: A review and research agenda. Heliyon, 8(9), e10734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignon, I., & Bankel, A. (2023). Sustainable business models and innovation strategies to realize them: A review of 87 empirical cases. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(4), 1357–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milana, E., & Ulrich, F. (2022). Do open innovation practices in firms promote sustainability? Sustainable Development, 30(6), 1718–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, C., Oliveira, T., & Santini, F. (2022). Sustainable technologies adoption research: A weight and meta-analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 165, 112627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurosis, M. (1994). Statistical data analysis. SPSS Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard, P. A., Duic, N., Noorollahi, Y., & Kalogirou, S. (2023). Advances in renewable energy for sustainable development. Renewable Energy, 219(1), 119377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñarroya-Farell, M., Miralles, F., & Vaziri, M. (2023). Open and sustainable business model innovation: An intention-based perspective from the Spanish cultural firms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(2), 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. (1993). The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American Prospect, 4, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Puumalainen, K., Sjögrén, H., Soininen, J., Syrjä, P., & Kraus, S. (2023). Crisis response strategies and entrepreneurial orientation of SMEs: A configurational analysis on performance impacts. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 19, 1527–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, M., Zhang, Y., Ali, M., & Kirikkaleli, D. (2024). Towards environmental sustainability: The role of information and communication technology and institutional quality on ecological footprint in MERCOSUR nations. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 34, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, N., Souza, G. C., Tröster, C., & Voigt, G. (2023). Offset or reduce: How should firms implement carbon footprint reduction initiatives? Production and Operations Management, 32(9), 2940–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado-Cubero, A., Freire-Rubio, T., & Hernández, A. (2022). Entrepreneurship: What matters most. Journal of Business Research, 144, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A. T., Figueiredo, J., & Bloor, M. (2024). Sustainable entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility: Analysing the state of research. Sustainable Environment, 10(1), 2324572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarango-Lalangui, P., Castillo-Vergara, M., Carrasco-Carvajal, O., & Durendez, A. (2023). Impact of environmental sustainability on open innovation in SMEs: An empirical study considering the moderating effect of gender. Heliyon, 9(9), e20096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satar, M. S., Alenazy, A., Alarifi, G., Alharthi, S., & Omeish, F. (2025). Digital capabilities and green entrepreneurship in SMEs: The role of strategic agility. Innovation and Development, 15(3), 709–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. N., & Parvatiyar, A. (2020). Sustainable marketing: Market-driving, not market-driven. Journal of Macromarketing, 41(1), 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwong, C., Pongsakornrungsilp, S., Pongsakornrungsilp, P., & Kumar, V. (2024). Mapping the terrain of open innovation in consumer research: Insights and directions from bibliometrics. Sustainability, 16(15), 6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekala, K., Baradarani, S., Alzubi, A., & Berberoğlu, A. (2024). Green entrepreneurship for business sustainability: Do environmental dynamism and green structural capital matter? Sustainability, 16, 5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniolo, S., Pieretto, C., & Camana, D. (2023). Improving sustainability in communities: Linking the local scale to the concept of sustainable development. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 101, 107126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toroslu, A., Herrmann, A., Chappin, M., Schemmann, B., & Castaldi, C. (2023). Open innovation in nascent ventures: Does openness influence the speed of reaching critical milestones? Technovation, 124, 102732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, A., Caputo, A., Pizzi, S., & Valenza, G. (2022). A dynamic framework for sustainable open innovation in the food industry. British Food Journal, 124(6), 1895–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viale, L., Vacher, S., & Frelet, I. (2022). Open innovation as a practice to enhance sustainable supply chain management in SMEs. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal, 23(4), 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrwich, M., Steinberg, P. J., Noseleit, F., & de Faria, P. (2022). Is open innovation imprinted on new ventures? The cooperation-inhibiting legacy of authoritarian regimes. Research Policy, 51(1), 104409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangailo, T., & Qutieshat, A. (2022). Uncovering dominant characteristics for entrepreneurial intention and success in the last decade: Systematic literature review. Entrepreneurship Education, 5, 145–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S. H., Rhim, H., & Park, M. S. (2019). Sustainable waste and cost reduction strategies in a strategic buyer-supplier relationship. Journal of Cleaner Production, 237, 117785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., O’Connor, G., Wu, J., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2021). Age and entrepreneurial career success: A review and a meta-analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(1), 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.