Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Digital platforms (e.g., LinkedIn, WeChat, university webpages, and blogs) significantly influence students’ career decision-making, career choice satisfaction, and career commitment.

- Traditional marketing tools (e.g., brochures and fairs) remain important sources of credibility and trust, particularly for long-term commitment.

- Transparency, authenticity, and alignment between online messages and students’ lived experiences are central to positive outcomes.

- Demographic factors, especially age and gender, moderate how students engage with and respond to marketing tools.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Universities should adopt hybrid marketing strategies that integrate digital engagement with trusted traditional channels.

- Clear, transparent, and realistic online communication is essential for sustaining student satisfaction and institutional trust.

- Alumni and peer-generated content can strengthen authenticity and support long-term career commitment.

- Marketing strategies should be demographically sensitive and culturally adaptive to enhance inclusivity, competitiveness, and institutional performance in emerging higher education systems.

Abstract

This study explores how digital and traditional marketing tools influence higher education students’ career decision-making, satisfaction, and career commitment during students’ educational trajectories in Iraq’s rapidly expanding university sector. Using an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design, a survey of 622 students was analysed with partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), followed by 24 semi-structured interviews with marketing and recruitment professionals. The quantitative findings show that students’ first-choice preferences, demographic factors, and engagement with LinkedIn, WeChat, blogs, and university webpages significantly shaped their career choices and satisfaction levels. Qualitative insights reveal that authenticity, transparent communication, and alignment between institutional messaging and lived experiences were key to sustaining trust. Traditional channels such as brochures and fairs remained important for credibility, supporting a hybrid marketing approach. The study contributes to management theory and practice in universities by linking digital communication strategies to student engagement and institutional performance. It also highlights the need for inclusive, transparent, and culturally adaptive marketing that reflects local and global contexts. These findings provide actionable guidance for higher education administrators seeking to build sustainable student trust, enhance recruitment effectiveness, and strengthen institutional reputation in competitive and resource-constrained systems.

1. Introduction

Within higher education, online marketing tools, particularly social media, have become central to how institutions communicate with stakeholders and shape students’ academic and career trajectories. Social platforms nurture interaction, brand awareness, and community engagement, making them integral to higher education marketing and management strategies (Peruta & Shields, 2017; Rutter et al., 2016). Universities’ digital presences now extend beyond information dissemination, functioning as interactive spaces where students form perceptions of institutional quality, reputation, and value (Rauschnabel et al., 2016). These dynamics are especially relevant in competitive, resource-constrained systems, where effective recruitment and retention are critical to organisational sustainability (Guilbault, 2016).

Recent management research highlights that digital engagement directly influences organisational trust, brand credibility, and performance in higher education (Song et al., 2023; Perera et al., 2023). At the same time, studies in Administrative Sciences stress the strategic importance of digital transformation, communication transparency, and data-driven decision-making for institutional competitiveness (Magdalenić, 2025; Shalihati et al., 2025). Despite this growing evidence, the mechanisms through which online marketing tools shape students’ educational and career decisions remain underexplored, particularly in emerging systems. Addressing this gap, the present study investigates how digital and traditional marketing tools influence higher education students’ career decision-making, satisfaction, and commitment in Iraq, a rapidly expanding and digitally evolving higher education context.

1.1. Universities and Social Media Interaction with the Public

Marketing in higher education has evolved from one-way promotional activity to interactive branding and stakeholder engagement (Berthon et al., 2012; Vrontis et al., 2018). Universities increasingly rely on social media to strengthen brand identity (Rauschnabel et al., 2016), enhance institutional reputation (Azoury et al., 2014), and support recruitment outcomes (Rutter et al., 2016). Platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and LinkedIn enable direct dialogue with prospective students, fostering trust and value co-creation (Peruta & Shields, 2017).

In this new landscape, students act as “co-creators of value,” shaping brand credibility through engagement with institutional and peer-generated content (Berthon et al., 2012). Such engagement influences perceptions of authenticity and relevance, which in turn affect application and enrolment decisions. Research in Administrative Sciences reinforces that digital interaction and user-generated content have measurable managerial implications for higher education administrators, particularly in recruitment, stakeholder communication, and service quality improvement (Garay Gallastegui & Reier Forradellas, 2021; Magdalenić, 2025). Similarly, cross-cultural studies highlight the need for culturally adaptive digital strategies to maintain competitiveness across diverse international markets (Alalwan et al., 2017; Shneikat et al., 2021). Building on these insights, this study situates Iraq within the global conversation on higher education management, examining how universities leverage online platforms to sustain trust, enhance credibility, and remain competitive in an expanding system.

1.2. Career Decision-Making, Career Choice Satisfaction, and Career Commitment

Career decision-making refers to the process by which students evaluate and select career paths (Kulcsár et al., 2020). Online marketing tools can shape this process by providing access to programme information, peer experiences, and professional networks through institutional websites, social media, and online events (Guilbault, 2016). Studies have shown that when students perceive congruence between institutional messages and their aspirations, they make more confident and informed decisions (Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka, 2015).

Career choice satisfaction reflects students’ contentment with their academic or professional trajectory and has been linked to psychological and contextual antecedents such as career adaptability and self-efficacy (Li et al., 2023). Online platforms can enhance satisfaction by providing transparent, experience-based information about programme quality, learning opportunities, and graduate outcomes, thereby supporting informed expectations and engagement (Okolie et al., 2022). Satisfaction grows when marketing content is authentic, consistent, and supported by real outcomes, reinforcing trust between institutions and students (Veloutsou et al., 2004).

Career commitment denotes students’ long-term dedication to a chosen field of study and future profession (Zhu et al., 2021). Marketing tools play a role in reinforcing this commitment by facilitating ongoing engagement through networking opportunities, alumni communities, and professional development initiatives (Zhu et al., 2021). Sustained engagement fosters loyalty and strengthens institutional reputation, linking individual career development to broader organisational goals (Perera et al., 2023; Shalihati et al., 2025). Collectively, these findings suggest that digital and traditional marketing tools serve as managerial levers to shape students’ perceptions, satisfaction, and long-term attachment to their careers and institutions.

1.3. Theoretical Perspectives

The study draws upon three complementary theoretical perspectives. Career development theories (Super, 1990; Savickas, 2013) propose that satisfaction and commitment evolve as individuals perceive alignment between their aspirations and available educational opportunities. Person-environment fit theory emphasises that congruence between personal goals and institutional characteristics enhances decision-making confidence, satisfaction, and identity clarity (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). Meanwhile, digital branding and communication research demonstrates that authenticity, transparency, and trust are central to maintaining long-term engagement (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010; Alalwan et al., 2017). Recent management scholarship also highlights how the integration of digital tools and administrative practices can improve institutional responsiveness and evidence-based decision-making (Garay Gallastegui & Reier Forradellas, 2021). Together, these perspectives underpin the study’s conceptual framework, explaining why digital and traditional marketing tools are expected to influence students’ decision-making, satisfaction, and commitment within higher education.

1.4. The Iraqi Higher Education Sector

Iraq’s higher education sector has expanded rapidly over the past two decades due to demographic growth, political reform, and economic diversification. Before 2003, public universities were few and centrally managed; subsequent reforms increased access through the establishment of new institutions across provinces. Private universities also emerged to reduce pressure on the public system and expand provision in fields such as business, law, computer science, and pharmacy (Al-Bayati & Salman, 2020). This expansion has intensified competition, encouraging universities to adopt diverse marketing and recruitment strategies, including the strategic use of social media and digital communication (Republic of Iraq, Ministry of Education, 2022; Harb, n.d.).

Alongside sectoral expansion, recent evidence points to significant progress in educational participation between genders, particularly at the postgraduate level. National statistics and policy reports indicate a substantial rise in women’s enrolment in graduate programmes over recent years, reflecting broader reforms aimed at improving access, equity, and women’s empowerment in Iraqi higher education (Republic of Iraq, Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, 2023; UNESCO, 2023). Secondary analyses suggest that women’s participation in postgraduate studies increased from approximately 48% in the 2018–2019 academic year to nearly 69% by 2022–2023, signalling a marked shift in gender representation within the sector (Abdulnabi Abbas & Fadhil Ridha, 2025).

These developments have implications for how universities communicate with prospective students. In culturally embedded contexts such as Iraq, institutional communication is shaped not only by market competition but also by social norms related to gender roles, family expectations, and perceptions of professional legitimacy. As a result, marketing messages often balance globalised digital branding practices with culturally resonant narratives emphasising trust, respectability, and alignment with societal values (Hemsley-Brown & Oplatka, 2015; Shneikat et al., 2021).

While global scholarship has examined digital marketing in higher education (Vrontis et al., 2018; Shneikat et al., 2021), research on these dynamics in Iraq remains limited. Exploring this context contributes to the broader understanding of how universities in emerging markets integrate marketing tools into management practices to attract and retain students in an increasingly competitive environment.

1.5. Significance of the Study

This study examines how online marketing tools influence students’ career decision-making, satisfaction, and commitment, constructs that are central to student success and institutional sustainability. By combining quantitative and qualitative methods, the research generates actionable insights for university leaders, policymakers, and marketing professionals. It highlights how digital platforms and traditional tools together shape student perceptions, institutional credibility, and long-term engagement.

The study contributes to management theory and practice in higher education by linking digital marketing and communication strategies to decision-making processes, satisfaction, and career commitment. It also responds to calls for research that integrates student-centred and administrative perspectives to enhance organisational learning and performance (Magdalenić, 2025; Shalihati et al., 2025). The findings are timely, given the accelerating digital transformation of universities worldwide and the growing importance of evidence-based marketing management in competitive, resource-constrained environments.

2. Methodology

This study employed an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design (Doyle, 2019), beginning with a quantitative survey of 622 students, followed by 24 qualitative interviews with higher education marketing practitioners. The qualitative phase enriched the statistical results and enabled integration across design, methodology, and interpretation (Fetters et al., 2013). The two phases were sequentially linked, and the results were synthesised through narrative weaving to produce a coherent explanation of how marketing tools influence career-related outcomes.

This design is particularly suitable for higher education management research, where quantitative data identify broad patterns and qualitative insights offer institutional and practical context (Song et al., 2023).

2.1. Quantitative Study

2.1.1. Measures

The survey was informed by prior studies of digital marketing in higher education (Guilbault, 2016; Rutter et al., 2016). It included five sections:

- Demographics: gender (male = 0, female = 1), age (continuous), education level (ordinal; undergraduate [1–5], Master’s, PhD), country of study, and scholarship status (self-funded = 0, scholarship = 1) as described in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive sample data.

Table 1. Descriptive sample data. - Perceptions of e-marketing tools: perceived effectiveness of Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, LinkedIn, Instagram, WeChat, university webpages, YouTube Ads, WhatsApp Ads, blogs, Google Ads, and virtual open days.

- Career-related choices: (a) Was this university your first career choice? (No = 0, Yes = 1); (b) Which influenced your choice more—e-marketing (0) or traditional marketing (1)?; (c) Was your chosen profession your first choice? (No = 0, Yes = 1).

- Career commitment: a seven-item scale adapted from Kautish et al. (2021). Reliability and validity were acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.783; AVE = 0.714; MSV = 0.425; ASV = 0.372; CR = 0.884). Example items included: “I do not regret my decision to select this profession,” and “I would like to work in this profession after completing my education.”

- Career choice satisfaction: three items adapted from the FIT-Choice scale (Richardson & Watt, 2006; Watt & Richardson, 2007) measuring satisfaction, happiness, and thoughtful decision-making about the programme.

2.1.2. Validity, Reliability, and Multilingual Procedures

Validity was established through alignment with existing, validated scales and a pilot test involving 10 students prior to full data collection (Thornhill et al., 2009). During pilot testing, two participants recommended offering the survey in additional languages to improve accessibility for linguistic minority groups. Consequently, the survey was administered in multiple languages.

The survey instrument was administered primarily in Iraq’s two official languages, Arabic and Kurdish. In response to participant feedback during the pilot phase, the survey was additionally translated into Turkmen and Assyrian to enhance inclusivity and comprehension within the Iraqi higher education context.

All survey instruments, questionnaires, and response materials were translated by a professional translation agency. To ensure linguistic equivalence and conceptual consistency across language versions, one co-author, fluent in all spoken and written languages used in the study, conducted a systematic item-by-item review of all translations. This expert review involved comparing each translated version against the original instrument, identifying discrepancies in wording or meaning, and resolving inconsistencies through discussion and revision. This process served as a quality-assurance and expert-validation mechanism rather than a mechanical back-translation procedure.

In addition, all language versions of the survey were pilot tested prior to the main data collection to verify clarity, comprehension, and equivalence of meaning across languages. Feedback from pilot participants indicated that items were clearly understood and conveyed consistent meanings across language versions. These procedures were undertaken to support measurement equivalence and cross-linguistic comparability, while acknowledging the practical constraints of multilingual survey administration in applied field research.

Reliability and construct validity indices for each scale are reported in the Results Section.

2.1.3. Participant Recruitment and Sample Size

Data were collected between January and June 2022 using an online questionnaire administered via Google Forms. A convenience sampling approach was employed due to logistical, access, and institutional constraints common in large, multi-institutional higher education systems. Recruitment was conducted by distributing QR codes during lecture sessions across participating universities and encouraging students to share the survey link with peers through informal student networks.

Inclusion criteria required participants to be officially enrolled university students, actively attending their programme of study, and aged 18 years or older. Exclusion criteria included individuals who were not enrolled as students or who were under the age of 18. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained prior to survey completion; participants were free to withdraw at any point without penalty.

The survey link was distributed to approximately 6,220 university students, yielding 789 initial responses (approximate response rate: 12.7%). After excluding incomplete, inconsistent, or ineligible submissions, 622 valid responses remained for analysis. This final sample exceeded the minimum recommended sample size of 384 for a population of approximately 900,000 higher education students in Iraq (5% margin of error; 95% confidence level) (Qualtrics, 2023; Republic of Iraq, Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, 2023). All survey respondents were already enrolled in higher education at the time of data collection, and the survey captured retrospective reflections on how engagement with university marketing touchpoints influenced their initial university and early career-related decisions.

Although the use of convenience sampling limits the statistical generalisability of the findings, the sample is appropriate for the study’s objectives, which focus on examining relationships between students’ engagement with marketing tools and career-related outcomes rather than estimating population prevalence. The sample demonstrates substantial heterogeneity in gender, age, level of study, and funding status (see Table 1), supporting the robustness of the relational analyses conducted using PLS-SEM.

Accordingly, the findings are interpreted as analytically generalisable to similar higher education contexts characterised by rapid expansion, mixed public–private provision, and increasing reliance on digital communication, rather than as statistically representative of all Iraqi university students. These limitations are considered further in the Discussion Section.

No missing data were observed in the retained dataset; however, several items were removed during model refinement due to low factor loadings, in line with established PLS-SEM guidelines.

2.1.4. Data Analysis

Data were analysed using SmartPLS 4 for Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) (Ringle et al., 2022). Two MIMIC (Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes) models were specified: Model 1, with career choice satisfaction as the endogenous variable, and Model 2, with career commitment. PLS-SEM is particularly suited for exploratory, variance-based analysis and has been widely applied in management and digital transformation studies (Garay Gallastegui & Reier Forradellas, 2021; Henseler, 2017).

2.2. Qualitative Study

2.2.1. Data Collection

The qualitative phase consisted of 24 semi-structured key informant interviews with marketing, social media, and recruitment staff from Iraqi universities (see Table 2 for participant profiles). This phase was designed to elaborate on, contextualise, and explain the quantitative findings within an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design (Fetters et al., 2013). University marketing and recruitment professionals were selected as interview participants because the qualitative phase aimed to explain institutional communication strategies and decision rationales underlying the patterns observed in student responses, rather than to capture additional student-level perceptions.

Table 2.

The profile of the experts interviewed.

Participants were recruited using purposive, key informant sampling, drawing on volunteers from the survey phase and professionals identified through academic and institutional networks. Key informant interviewing was selected because participants occupied roles that made them particularly knowledgeable about institutional marketing practices, communication strategies, and student engagement processes. As Patton (2002, p. 321) notes, key informants are individuals who are “particularly knowledgeable about the inquiry setting and articulate about their knowledge,” enabling researchers to understand not only what is happening but also why.

This sampling strategy was intended to enhance the credibility and explanatory power of the qualitative findings, rather than to achieve statistical representativeness (Miles et al., 2014; Patton, 2002, p. 321). Efforts were made to ensure diversity across gender, age, geographic region, and institutional type (public and private) in order to capture a range of organisational perspectives and practices within the Iraqi higher education sector.

Interviews were conducted either online or face-to-face, depending on participant availability and institutional context. All interviews were audio-recorded with informed consent and transcribed verbatim. Sessions took place several weeks after the completion of the survey to ensure proper sequential integration between the quantitative and qualitative phases. The interviewers’ professional backgrounds in marketing positioned them as cultural insiders, facilitating rapport and context-sensitive inquiry while maintaining reflexive awareness of positionality (Manohar et al., 2017).

2.2.2. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis combined deductive categories derived from quantitative findings with inductive themes emerging from transcripts (Brannen & O’Connell, 2015; Doyle, 2019). Manual coding involved iterative reading, note-taking, and peer debriefing between researchers to enhance analytical rigour. Reflexivity was maintained throughout to acknowledge the researchers’ positionality and minimise bias (Corlett & Mavin, 2018).

Integration followed an explanatory sequential logic (Creswell, 2015), in which qualitative findings explained and expanded on statistical trends. This complementarity strengthened both the academic contribution and practical value of the study, enhancing the evidence base for effective management and decision-making in higher education.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Faculty Research Ethics Committee of the institution with which the fifth author was affiliated at the time of approval(Approval No. Approval No. FMS105, dated 27 October 2020). The study complied with all relevant institutional and national guidelines for research involving human participants. All participants provided informed consent, and confidentiality and anonymity were assured throughout data collection, analysis, and reporting.

3. Results

The results are presented in two stages, reflecting the explanatory sequential mixed-methods design. First, quantitative findings are reported, beginning with the measurement and structural model assessments using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). These tests establish construct validity and reliability and assess the hypothesised relationships. The findings are then organised thematically around three key outcomes: career decision-making, career choice satisfaction, and career commitment. Second, qualitative insights from interviews with marketing and social media experts are integrated within each theme to provide organisational and managerial context.

3.1. Measurement and Structural Models

The measurement model was first assessed for internal consistency, discriminant validity, and convergent validity (Hair et al., 2019). Reliability was confirmed through Dijkstra-Henseler’s rho_A, Werts’s rho_C, and Cronbach’s alpha (Henseler, 2017; Ringle et al., 2020), with all values falling within the acceptable 0.70–0.95 range for career choice satisfaction (Hair et al., 2017). However, items CCOMMIT2 and CCOMMIT5 were removed because they did not meet the required factor loadings. Convergent validity was supported by average variance extracted (AVE) values above 0.50 (Ringle et al., 2020), indicating that more than half of each construct’s variance was explained by its items. All external loadings exceeded 0.708 (Hair et al., 2017), and discriminant validity was established with HTMT ratios below 0.85.

Table 3.

Internal consistency reliability and convergent validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant analysis (Heterotrait Monotrait Ratio Matrix).

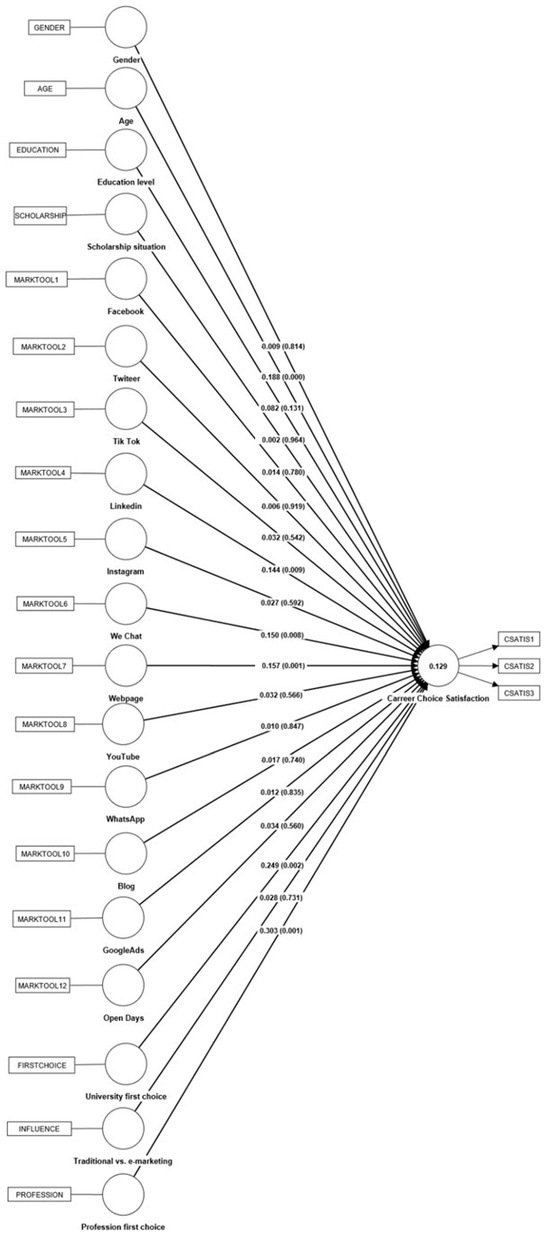

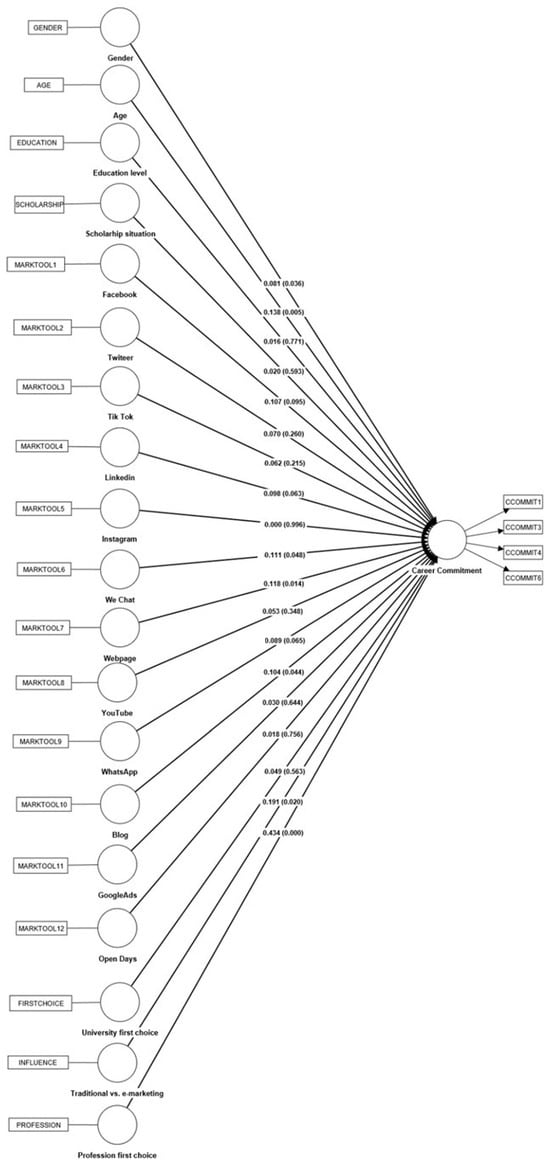

The structural model was then evaluated using two MIMIC models: Model 1, with career choice satisfaction as the endogenous variable, and Model 2, with career commitment. Both models included demographic characteristics, marketing tools (Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, LinkedIn, Instagram, WeChat, university webpage, YouTube, WhatsApp, blogs, Google Ads, and open days), and student-related variables as exogenous predictors. Bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples was applied (Henseler et al., 2016). The analysis included R2 values, path coefficients, and effect sizes (Henseler, 2017). Results are summarised in Table 5 and illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Furthermore, the SRMR fit index (Standardised root mean square residual) was evaluated for both models, obtaining values of 0.040 for model 1 and 0.046 for model 2, which are below 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1998), thus indicating an adequate fit of the models.

Table 5.

Structural model assessment.

Figure 1.

Model 1.

Figure 2.

Model 2.

These findings confirm that the use of digital engagement indicators in modelling student behaviour can provide measurable insights for university decision-making and performance management (Magdalenić, 2025).

3.2. Career Decision-Making

Model 1 revealed that students’ first-choice profession (beta = 0.303, p < 0.001) and first-choice university (beta = 0.249, p < 0.002) were significant predictors of career decision-making, alongside engagement with WeChat (beta = 0.150, p < 0.008) and LinkedIn (beta = 0.144, p < 0.009). These results indicate that both personal preference and institutional marketing activities shape students’ initial career-related choices.

Qualitative findings supported these results. A social media coordinator (A1) noted,

“Students usually start their search on WeChat groups and LinkedIn because they trust information coming from peers and alumni, not just official advertisements.”

Similarly, a marketing manager (B4) described online groups as “a first point of influence before formal recruitment campaigns,” while content creators (C3, D4) highlighted the role of visual storytelling on Instagram and blogs. Together, these insights emphasise that authentic, peer-driven content complements universities’ digital strategies in guiding prospective students’ decisions.

3.3. Career Choice Satisfaction

In Model 1, age (beta = 0.188, p < 0.000), university first choice (beta = 0.249, p < 0.002), WeChat (beta = 0.150, p < 0.008), LinkedIn (beta = 0.144, p < 0.009), and the university webpage (beta = 0.157, p < 0.001) were significant positive predictors of career choice satisfaction. These findings suggest that satisfaction depends on personal alignment with institutional choice, reinforced by transparent digital communication.

Interview insights confirmed the importance of credibility. A marketing analyst (C5) stated,

“When the webpage clearly shows programme outcomes and career opportunities, students feel reassured that they made the right choice.”

A sales manager (A3) added that “misalignment between online promises and reality leads to disappointment,” while a promotion manager (D1) observed that transparency “reduces regret later on.” For institutional leaders, these findings highlight the managerial value of ensuring that online communication reflects authentic institutional strengths.

3.4. Career Commitment

Model 2 indicated that profession first choice (beta = 0.434, p < 0.000), traditional versus e-marketing tools (beta = 0.191, p < 0.020), WeChat (beta = 0.111, p < 0.048), university webpage (beta = 0.118, p < 0.014), blogs (beta = 0.104, p < 0.044), gender (beta = 0.081, p < 0.036), and age (beta = 0.138, p < 0.005) significantly influenced career commitment. These results highlight the combined effect of demographic factors and marketing channels on students’ sustained engagement.

A social media specialist (E2) explained,

“Blogs by alumni keep students motivated about their field because they see real career paths unfolding.”

A digital marketing manager (F1) added,

“Webpages are not just marketing; they become reference points throughout the degree.”

Across participant roles (B2, D3, F3), experts also emphasised the continuing relevance of traditional tools such as fairs and brochures in building familiarity and trust. These findings align with evidence from Shalihati et al. (2025), which underscores the complementary role of digital and traditional communication in higher education management.

3.5. Summary of Findings and Managerial Implications

The quantitative models demonstrated that demographic factors, first-choice preferences, and engagement with key online platforms (WeChat, LinkedIn, webpages, and blogs) significantly influence students’ career decision-making, satisfaction, and commitment. The qualitative findings explained why: students trust peer-generated and transparent institutional content (A1, B4, C5), value authenticity and consistency between institutional messages and their lived experiences (A3, D1), and maintain long-term engagement through alumni blogs and institutional webpages (E2, F1).

For university administrators and policymakers, three managerial implications emerge:

- Transparency: Institutional webpages and social media profiles should present clear and verifiable information on programmes and career-related outcomes.

- Authenticity: Peer- and alumni-driven content enhances credibility; universities should facilitate and moderate such contributions.

- Hybrid strategies: Traditional tools, including fairs and brochures, remain vital in complementing digital communication and building trust.

These findings strengthen the evidence base for effective higher education management by demonstrating how hybrid digital strategies can enhance recruitment, retention, and long-term student engagement in competitive, resource-constrained systems.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates how online marketing tools shape students’ career decision-making, career choice satisfaction, and career commitment, integrating quantitative modelling with qualitative insights from institutional experts. The findings contribute to management and higher education research by clarifying how universities use digital and hybrid communication strategies to attract, inform, and retain students (Song et al., 2023; Shalihati et al., 2025). Importantly, the study focuses on career choice processes, satisfaction, and commitment during students’ educational trajectories, rather than on objective post-graduation labour-market outcomes.

Digital engagement is now integral to institutional performance and competitiveness, influencing how students perceive organisational quality, trust, and credibility (Magdalenić, 2025). The study’s mixed-methods design allows the observed quantitative relationships to be interpreted alongside institutional rationales and practices, revealing that digital and traditional tools function as interdependent components of higher education marketing ecosystems rather than as isolated or competing channels. This integrated perspective extends existing work by moving beyond platform effectiveness to examine how communication strategies collectively shape early career-related decisions.

4.1. Career Decision-Making

Students’ first-choice preferences and engagement with platforms such as WeChat and LinkedIn emerged as the strongest predictors of early career-related decisions. The relative strength of these predictors suggests that platforms perceived as credible, professionally oriented, and peer-informed play a particularly influential role in students’ evaluations of academic and career pathways. Qualitative insights reinforce this interpretation, as experts consistently emphasised that authentic, peer-generated, and alumni-shared content was more persuasive than overt promotional messaging. This aligns with prior evidence that relational and trust-based online engagement enhances institutional reputation and decision confidence (Song et al., 2023).

From a theoretical perspective, these findings reaffirm career construction theory (Savickas, 2013) and person–environment fit (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005), both of which emphasise the alignment between individual aspirations and organisational characteristics. Digital tools operationalise this alignment by enabling students to access personalised and credible narratives that help them visualise potential academic and career trajectories (Rutter et al., 2016; Vrontis et al., 2018). Managerially, the comparatively stronger influence of first-choice status and professional platforms highlights that marketing effectiveness depends not on volume of exposure but on the quality and congruence of communicated signals, supporting arguments that strategic alignment enhances institutional performance and conversion efficiency (Garay Gallastegui & Reier Forradellas, 2021).

4.2. Career Choice Satisfaction

Career choice satisfaction was shaped by demographic factors (particularly age), first-choice university status, and engagement with institutional webpages and professional networking platforms such as LinkedIn and WeChat. The prominence of official webpages relative to more informal social media channels suggests that satisfaction is closely tied to informational depth, transparency, and perceived reliability rather than to immediacy or entertainment value. Interview data reinforce this interpretation, as participants emphasised that satisfaction depended on the consistency between institutional promises and lived student experience (C5, D1).

These findings extend managerial discussions on informed university choice by demonstrating that truthful and evidence-based communication functions as a key mechanism for sustaining satisfaction, retention, and brand loyalty. Conceptually, this supports views of organisational communication as a trust-building process rather than a purely persuasive activity (Veloutsou et al., 2004). From a management perspective, the results indicate that accurate digital communication serves as a form of strategic quality assurance, strengthening perceived integrity and stakeholder confidence while reducing the risk of expectation–experience gaps (Magdalenić, 2025).

4.3. Career Commitment

Career commitment was influenced by profession first choice, the combined use of traditional and digital marketing tools, and exposure to institutional webpages and alumni blogs. Interviewees described how long-term attachment was reinforced through institutionally curated narratives of alumni success, including digital testimonials, career progression stories, and graduate spotlights shared via university websites and social media platforms. These narratives were discussed as strategic communication practices grounded in professional experience rather than as outcomes formally tracked through longitudinal metrics (E2, F1). Such practices appear to function as symbolic reinforcement mechanisms, supporting students’ identification with institutional and professional identities.

These results align with Super’s (1990) life-span, life-space theory, which conceptualises commitment as an evolving process shaped by repeated validation and role affirmation. The findings also corroborate management research highlighting the value of hybrid digital strategies in sustaining engagement and institutional trust over time (Shalihati et al., 2025). Notably, the continued relevance of traditional tools such as fairs and brochures suggests that face-to-face and tangible interactions remain critical for credibility and reassurance, particularly in early engagement stages, mitigating risks associated with digital fatigue or overreliance on transient online trends.

4.4. Demographic Moderators: Age and Gender

Age and gender differences moderated students’ responses to online marketing tools. Older students reported higher levels of career choice satisfaction and career commitment, reflecting more deliberate, reflective, and research-driven engagement with digital content (C2, F3). This pattern is consistent with research linking age and experience to increased digital literacy and evaluative information processing (Junco & Mastrodicasa, 2007). Importantly, age was treated as a continuous variable in the analysis; references to “older” students therefore reflect relative differences within the sample rather than categorical distinctions.

Gender differences were also evident, with female students demonstrating stronger career commitment, particularly in response to personalised digital content and the visibility of relatable role models. These effects should be interpreted in light of recent structural changes in Iraqi higher education, including substantial growth in women’s postgraduate participation, reflecting broader reforms aimed at enhancing access, equity, and professional opportunity. In this context, digital communication may serve not only informational but also identity-affirming functions, reinforcing legitimacy, aspiration, and professional self-efficacy.

This interpretation aligns with Bandura’s (1997) social cognitive theory, which emphasises modelling, representation, and self-efficacy as drivers of motivation and commitment. In culturally embedded contexts such as Iraq, where educational and career decisions are closely intertwined with family expectations and social norms, inclusive and culturally resonant communication may therefore be especially salient (Hemsley-Brown & Oplatka, 2015; Shneikat et al., 2021). Managerially, these findings underscore the strategic value of demographically sensitive marketing approaches that combine representation with transparency to promote equity and sustained engagement (Magdalenić, 2025).

4.5. Online vs. Traditional Tools

The positive influence of traditional tools such as fairs and printed brochures challenges assumptions of digital dominance in higher education marketing. Participants described these tools as tangible, trustworthy, and socially embedded, providing reassurance and interpersonal connection that mitigate the impersonality of digital platforms (B2, D3). This supports arguments for hybrid marketing ecosystems in which online and offline channels complement one another to maintain authenticity and credibility (Rauschnabel et al., 2016).

Consistent with management literature, these findings suggest that digitally augmented rather than digitally exclusive strategies foster greater institutional resilience and stakeholder loyalty (Shalihati et al., 2025). For universities, the implication is not to abandon digital innovation but to strategically balance it with human-centred engagement to sustain trust and long-term relationships.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research

Although the study provides valuable managerial and theoretical insights, several limitations warrant careful consideration. First, the study relied on a non-probability, convenience sampling approach, which constrains the statistical generalisability of the findings beyond the surveyed participants. While this approach was appropriate given logistical and access constraints and the study’s focus on examining relationships between marketing tools and career-related outcomes, the results should be interpreted with caution when extrapolating to the wider population of higher education students in Iraq or other contexts.

Second, although the sample exhibited substantial heterogeneity in gender, age, level of study, and funding status, it may not fully capture variation linked to socio-economic background, institutional culture, or regional disparities, which were not directly measured in the present study. These factors may shape students’ access to digital resources, perceptions of institutional communication, and career decision-making processes, and should therefore be examined explicitly in future research.

Third, the study employed a multilingual survey administration strategy to enhance accessibility and inclusivity. Although professional translation, expert review, and pilot testing were used to support linguistic equivalence across language versions, future studies could employ formal back-translation procedures or multi-group measurement invariance testing to further strengthen cross-linguistic measurement validation and comparability.

Additionally, the study did not analyse the relative effectiveness of specific content formats (e.g., video, audio, or text), focusing instead on platform-level engagement; future research could disaggregate content modalities to refine managerial guidance.

Because the study relied on convenience sampling, future research employing probability-based, stratified, or longitudinal designs would help strengthen external validity and assess the stability of observed relationships over time. Longitudinal or comparative cross-country studies could further explore how career choice satisfaction and career commitment evolve across educational stages and labour-market transitions (Super, 1990; Savickas, 2013).

Moreover, continued research on digital divides and unequal access to online information remains critical for understanding how structural inequalities influence engagement with digital marketing tools (Hargittai, 2010; van Deursen & van Dijk, 2015). Future investigations could also examine how differences in institutional digital maturity and strategic capacity shape the effectiveness of marketing communication and management performance across diverse higher education systems (Garay Gallastegui & Reier Forradellas, 2021).

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study demonstrates that online marketing tools significantly influence students’ career decision-making, choice satisfaction, and career commitment during their educational trajectories within Iraq’s expanding higher education sector. Platforms such as WeChat, LinkedIn, alumni blogs, and institutional webpages emerged as the most influential digital channels, while traditional methods, such as fairs and brochures, continued to build trust and confidence.

By integrating quantitative modelling with qualitative insights, the study explains both how and why these tools shape early career-related decisions and perceptions. The results underscore that authenticity, transparency, and hybrid engagement strategies drive satisfaction and institutional attachment, rather than objective post-graduation outcomes.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings extend career development and person-environment fit theories by demonstrating that digital tools serve as mechanisms for alignment between institutional communication and student aspirations. They also contribute to management research by illustrating how marketing and communication strategies can act as strategic levers for improving institutional performance, competitiveness, and brand equity (Shalihati et al., 2025; Magdalenić, 2025).

5.2. Managerial Implications

For university leaders and marketing managers, four priorities emerge:

- Transparency and Trust: Digital communication must accurately reflect programme realities and educational and career-development expectations.

- Authenticity and Engagement: Incorporating alumni and peer narratives strengthens early decision-making and long-term commitment.

- Hybrid Strategies: Combining digital and traditional marketing reduces fatigue and enhances credibility.

- Tailored Approaches: Age-sensitive and gender-inclusive messaging can improve both engagement and perceived institutional fairness.

These strategies support evidence-based decision-making and align marketing with institutional ethics, improving recruitment quality and student satisfaction.

5.3. Social and Policy Implications

From a societal perspective, transparent and inclusive marketing fosters fairness, broadens access, and empowers students as active contributors to institutional identity. Locally adapted yet globally oriented strategies, such as using WeChat for regional engagement and LinkedIn for international visibility, strengthen both equity and competitiveness.

In rapidly expanding systems such as Iraq’s, these insights are timely: universities that align institutional promises with student expectations not only enhance recruitment outcomes but also strengthen their social responsibility and contribute to sustainable human capital development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.K. and S.M.; Methodology, S.N.L.-H., M.K. and S.M.; Software, S.N.L.-H.; Validation, S.N.L.-H., M.K. and S.M.; Formal Analysis, S.N.L.-H.; Investigation, S.T., I.K. and N.C.; Data Curation, S.T., I.K. and N.C.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, M.K., S.M. and S.N.L.-H.; Writing-Review and Editing, M.K., S.M., S.N.L.-H., S.T., I.K. and N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Faculty Research Ethics Committee of the institution with which the fifth author was affiliated at the time of approval (Approval No. FMS105, dated 27 October 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time without penalty.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with participating institutions and data protection requirements.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of participating universities and staff members who supported data collection. The authors reviewed, edited, and approved all text and take full responsibility for the content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdulnabi Abbas, M., & Fadhil Ridha, R. (2025). Empowering women: Iraqi universities leading the way. Iraqi Academic Scientific Journals, 6(3), 907–928. [Google Scholar]

- Alalwan, A. A., Rana, N. P., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Algharabat, R. (2017). Social media in marketing: A review and analysis of the existing literature. Telematics and Informatics, 34(7), 1177–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, S. J. K., & Salman, N. A. (2020). Private university education in Iraq: Advantages, constraints, and remedies. Entrepreneurship Journal for Finance and Business, 1(2), 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Azoury, N. M., Daou, L. E., & El Khoury, C. (2014). University image and its relationship to student satisfaction: Case of the Middle Eastern private business schools. International Strategic Management Review, 2(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Berthon, P. R., Pitt, L. F., Plangger, K., & Shapiro, D. (2012). Marketing meets Web 2.0, social media, and creative consumers: Implications for international marketing strategy. Business Horizons, 55(3), 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannen, J., & O’Connell, R. (2015). Data analysis I: Overview of data analysis strategies. In S. Hesse-Biber, & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry (pp. 257–274). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corlett, S., & Mavin, S. (2018). Reflexivity and researcher positionality. In C. Cassell, A. Cunliffe, & G. Grandy (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods (pp. 377–399). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2015). Revisiting mixed methods and advancing scientific practices. In S. Hesse-Biber, & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry (pp. 61–71). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, L. (2019). An overview of mixed methods research. In SAGE mixed methods research. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—Principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6 Pt 2), 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay Gallastegui, N., & Reier Forradellas, R. (2021). Business methodology for the application in university environments of predictive machine learning models for the management of online reputation. Administrative Sciences, 11(4), 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbault, M. (2016). Students as customers in higher education: Reframing the debate. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 26(2), 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, I. (n.d.). Higher education and the future of Iraq. Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/46082/sr195.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Hargittai, E. (2010). Digital na(t)ives? Variation in internet skills and uses among members of the “net generation”. Sociological Inquiry, 80(1), 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsley-Brown, J., & Oplatka, I. (2015). University choice: What do we know, what don’t we know and what do we still need to find out? International Journal of Educational Management, 29(3), 254–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. (2017). Bridging design and behavioural research with variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junco, R., & Mastrodicasa, J. (2007). Connecting to the Net. Generation: What higher education professionals need to know about today’s students. NASPA. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P., Walia, S., & Kour, P. (2021). The moderating influence of social support on career anxiety and career commitment: An empirical investigation from India. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(8), 782–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulcsár, V., Dobrean, A., & Gati, I. (2020). Challenges and difficulties in career decision-making: Their causes, and their effects on the process and the decision. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 116, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Fan, W., & Zhang, L. (2023). Career adaptability and career choice satisfaction: Roles of career self-efficacy and socioeconomic status. The Career Development Quarterly, 71(4), 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalenić, I. (2025). Assessing the impact of digital tools on the recruitment and management processes in higher education institutions. Administrative Sciences, 15(4), 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, N., Liamputtong, P., Bhole, S., & Arora, A. (2017). Researcher positionality in cross-cultural and sensitive research. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp. 1–15). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Okolie, U. C., Nwali, A. C., Ogbaekirigwe, C. O., Ezemoyi, C. M., & Achilike, B. A. (2022). A closer look at how work placement learning influences student engagement in practical skills acquisition. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(7), 2278–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, C. H., Nguyen, L. T. V., & Nayak, R. (2023). Brand engagement on social media and its impact on brand equity in higher education: Integrating the social identity perspective. International Journal of Educational Management, 37(6–7), 1335–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruta, A., & Shields, A. B. (2017). Social media in higher education: Understanding how colleges and universities use Facebook. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 27(1), 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics. (2023). Sample size calculator. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/research/determine-sample-size/ (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Rauschnabel, P. A., Krey, N., Babin, B. J., & Ivens, B. S. (2016). Brand management in higher education: The university brand personality scale. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3077–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Iraq, Ministry of Education. (2022). National education strategy for Iraq 2022–2031. World Bank/Republic of Iraq. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099091824091030738/pdf/P171165-cfac2b5e-6448-4093-a5a5-2591a8024209.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Republic of Iraq, Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research. (2023). Annual statistical report on higher education in Iraq (2018–2023). MOHESR.

- Richardson, P. W., & Watt, H. M. G. (2006). Who chooses teaching and why? Profiling characteristics and motivations across three Australian universities. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., & Gudergan, S. P. (2020). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2022). SmartPLS 4 [Computer software]. SmartPLS GmbH. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Rutter, R., Roper, S., & Lettice, F. (2016). Social media interaction, the university brand and recruitment performance. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3096–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L. (2013). Career construction theory and practice. In S. D. Brown, & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 147–183). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Shalihati, H. I., Rahmawati, I., & Hadi, A. P. (2025). Mapping customer relationship management research in higher education institutions: A bibliometric analysis. Administrative Sciences, 15(2), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneikat, B., Cobanoglu, C., & Tanova, C. (Eds.). (2021). Global perspectives on recruiting international students: Challenges and opportunities. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Song, B.-L., Li, M., & Yu, C. (2023). The role of social media engagement in building relationship quality and brand performance in higher education marketing. International Journal of Educational Management, 37(2), 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D. E. (1990). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In D. Brown, & L. Brooks (Eds.), Career choice and development (2nd ed., pp. 197–261). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill, A., Saunders, M., & Lewis, P. (2009). Research methods for business students (5th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2023). Women’s participation in higher education in the Arab States: Trends and policy implications. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2015). Internet skill levels increase, but gaps widen: A longitudinal cross-sectional analysis (2010–2013) among the Dutch population. Information, Communication & Society, 18(7), 782–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloutsou, C., Lewis, J. W., & Paton, R. A. (2004). University selection: Information requirements and importance. International Journal of Educational Management, 18(3), 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D., El Nemar, S., Ouwaida, A., & Shams, S. R. (2018). The impact of social media on international student recruitment: The case of Lebanon. Journal of International Education in Business, 11(1), 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2007). Motivational factors influencing teaching as a career choice: Development and validation of the FIT-Choice scale. Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D., Kim, P. B., Milne, S., & Park, I.-J. (2021). A meta-analysis of the antecedents of career commitment. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(3), 502–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.