Abstract

Objective: There is growing interest in analyzing whether ethical climates influence the emotional states of organizational members. For this reason, the main objective of this study is to evaluate the relationship between a benevolent ethical climate, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization, taking into account the mediating effect of job autonomy. Methodology: To evaluate the research hypotheses, data were collected from 448 people belonging to six organizations in the Colombian electricity sector. Statistical analysis was performed using two structural equation models (SEMs). Results: The results show that a benevolent climate and its three dimensions (friendship, group interest, and corporate social responsibility) mitigate the negative effect of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. A work environment focused on people and society triggers positive moods that prevent the loss of valuable psychological resources. On the other hand, job autonomy is a mechanism that has a direct impact on the emotional well-being of employees. Therefore, being able to intentionally direct one’s own sources of energy and motivation prevents an imbalance between resources and demands that blocks the potential effect of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. Practical implications: This study has important practical implications. First, an ethical climate that seeks to build a caring environment needs to strengthen emotional communication among employees through a high perception of support. Second, organizations need to grow and achieve strategic objectives from a perspective of solidarity. Third, a benevolent ethical climate needs to be nurtured by professionals with a clear vocation for service and a preference for interacting with people. Finally, job autonomy must be accompanied by the necessary time management skills. Social implications: This study highlights the importance to society of an ethical climate based on friendship, group interest, and corporate social responsibility. In a society with a marked tendency to disengage from collective problems, it is essential to make decisions that take into account the well-being of others. Originality/value: This research responds to recent calls for more studies to identify organizational contexts capable of mitigating the negative effects of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

1. Introduction

Organizations are increasingly recognizing that sustainability is closely linked to the improvement of employee behavioral models. Unethical conduct directly affects institutional assets and undermines trust-based relationships with stakeholders. Moreover, workplace environments detached from ethical principles negatively impact professional satisfaction and significantly increase chronic workplace stress (Khan et al., 2021). As a result, there is growing interest in understanding which organizational systems can guide and regulate employee attitudes through specific ethical climates (Ayub et al., 2022). In this regard, Victor and Cullen (1988) proposed a conceptual framework grounded in three independent ethical criteria: benevolence, principle, and egoism. Their primary aim was to expand upon the notion of a moral atmosphere previously advanced by Levine et al. (1985). This study focuses on a specific ethical climate—benevolence—given its central objective of enhancing individual well-being alongside the social responsibility that organizations have toward their stakeholders (Blome & Paulraj, 2013). A benevolent ethical climate comprises three core dimensions: friendship, group interest, and corporate social responsibility (Cullen et al., 1993).

Cullen et al. (2003) define benevolence as a genuine concern for human beings and their needs. Decision-making is oriented toward enhancing collective well-being, even if it means curtailing certain individual needs. A fair and impartial work environment enables employees to shift part of their self-interest toward the benefit of the group. This tolerant and understanding framework is associated with perceptions of responsibility, emotional closeness, and trust, which may impede the development of burnout (Elçi et al., 2015). Burnout is characterized as a state of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment that leads to diminished concern for work-related tasks and for the needs of others. Burnout typically manifests in negative and cynical behaviors, lack of empathy, and a tendency toward self-deprecating evaluations (Maslach & Leiter, 2016).

In this context, a work culture that decisively embraces a benevolent climate demonstrates a sincere concern for society and prioritizes the practical consequences of organizational behavior over abstract theoretical intentions (Santiago-Torner, 2023b). This realistic and functional approach helps mitigate role ambiguity and conflict, as work expectations are shared, reducing job uncertainty and stress levels. The orientation of a benevolent climate weakens workplace tension by establishing clear boundaries for employee engagement within organizational processes (Ayub et al., 2022). In fact, burnout often stems from extra-role behaviors or ill-defined personal contributions. When this role expansion becomes habitual, it overwhelms emotional limits, leading to exhaustion. Therefore, an organizational context that decisively regulates codes of conduct is more likely to prevent exaggerated emotional responses or impersonal reactions toward others (Elçi et al., 2015).

Furthermore, a benevolent climate enhances professionals’ sense of responsibility regarding role-related demands. In this respect, a workplace that fosters emotional security enables employees to perform their tasks autonomously (Santiago-Torner, 2023a). Job autonomy functions as a critical resource at work and is defined as the employee’s capacity to manage work-related aspects, act independently, make decisions, and adapt schedules within organizational boundaries (Sia & Appu, 2015). From this perspective, the ability to redistribute effort voluntarily fosters a sense of harmony that obstructs emotional depletion (Fernet et al., 2014).

This research aims to contribute to the existing literature in several ways, thereby addressing a significant knowledge gap. First, the buffering effect of certain ethical climates on burnout remains inconclusive. There is limited empirical evidence demonstrating how ethical climates influence employee attitudes. For instance, Ayub et al. (2022) found a positive association between unethical practices and the burnout dimensions of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. Elçi et al. (2015) proposed a partial mediating role of ethical climate in the relationship between organizational justice and burnout. Similarly, authors such as Faelens et al. (2013) and Ozdoba et al. (2022) identified a clear affinity between ethical climate and job satisfaction. Tehranineshat et al. (2020) found a positive association between professional values, ethical climate, and quality of life. Other studies (Li & Peng, 2022; Rivaz et al., 2020; Sahi et al., 2022; Saleh et al., 2022) indicate that an ethical climate mitigates employee burnout. Meanwhile, Mulki et al. (2008) concluded that an ethical climate reduces role stress, interpersonal conflict, and psychological burnout by fostering trust in supervisors.

Second, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization have garnered substantial attention from both scholars and practitioners in the post-COVID-19 era (Sunjaya et al., 2021; Tian & Sun, 2024). However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have specifically examined the role of a benevolent ethical climate in influencing the depletion or enhancement of emotional resources. A workplace environment that prioritizes well-being may function as a resource that promotes professional engagement. In doing so, employees are better able to absorb increased workloads while maintaining emotional resilience (Shanafelt & Noseworthy, 2017). Friendship and collective interest serve as psychosocial supports and may act as beneficial strategies for managing emotional conflicts that lead to exhaustion and depersonalization (Doolittle, 2021). Additionally, internal and external corporate social responsibility enhances subjective well-being and professional resilience, significantly reducing the risk of emotional exhaustion (Liu et al., 2023).

Third, this study provides additional theoretical support regarding the relationship between ethical climate and burnout by introducing job autonomy as a mediating mechanism. Job autonomy is a resource that grants professionals a degree of control over their tasks. According to the updated self-determination theory by Ryan and Deci (2020), job autonomy involves the ability to manage motivational and energy-related resources, thus serving as a psychological mechanism that may counteract emotional overload (Fernet et al., 2013). Recent studies (e.g., Guo et al., 2023; Zhang & He, 2022) have confirmed the buffering role of job autonomy on burnout. However, this is the first study to introduce job autonomy as a mechanism that explains how and why a benevolent ethical climate is associated with burnout.

Thus, the main objective of this study is to assess the relationship between a benevolent ethical climate and the two core dimensions of burnout—emotional exhaustion and depersonalization—while accounting for the mediating effect of job autonomy. This study deliberately omits the analysis of reduced personal accomplishment, as several studies suggest it is an inseparable consequence of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Elçi et al., 2015).

Study Context

Colombia represents a paradigmatic case for examining the interaction between organizational structures, ethical factors, and emotional well-being at work. For decades, the country has endured structural challenges associated with armed conflict, institutional corruption, and pronounced social inequality. These conditions have had widespread effects on strategic sectors, including the electric industry, which has been compelled to transform in response to the demands of a sustainability-oriented energy transition marked by decentralization and digital innovation.

In this context of continuous change, the psychological well-being of workers has become an emerging concern. Constant adaptation requirements, combined with pressure to meet new technical and social standards, can trigger emotional fatigue and affective disconnection—especially in environments where organizational support systems are weak or nonexistent (Bellou & Chatzinikou, 2015). Despite its strategic relevance, the Colombian electric sector lacks empirical studies analyzing how ethical configurations in the work environment may act as protective factors against burnout, particularly emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. This study makes a substantive empirical contribution by addressing this gap. It introduces the concept of a benevolent ethical climate as a central explanatory variable—a form of organizational climate grounded in mutual care, colleague solidarity, and social responsibility as normative pillars. This approach is especially relevant in a context like Colombia’s, where organizations face constant tension between operational efficiency and the need to rebuild institutional trust based on robust ethical principles.

The inclusion of a benevolent ethical climate as an explanatory variable in the analysis of burnout responds to recent scholarly calls to examine the contextual factors that promote emotionally sustainable workplaces with greater precision (Santiago-Torner, 2024a). The analysis focuses not on a general notion of ethical climate but on a specific configuration—benevolence—distinguished by its capacity to foster emotional bonds, group cohesion, and moral engagement with the environment. This focus enables the identification of specific mechanisms through which organizations can protect employees’ emotional capital, rather than depleting their psychological resources in response to mounting external demands. Moreover, this study positions job autonomy as a mediating variable that links the subjective experience of ethical climate to the emotional outcomes perceived by workers. This approach is especially valuable in sectors such as energy, where change management is often accompanied by rigid hierarchical models that inhibit self-direction and individual initiative. In this sense, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of how ethical redesign of workplace environments can activate individual psychosocial resources—such as autonomy—to buffer the adverse effects of chronic stress.

In sum, this research stands out for three key contributions: (1) it analyzes a specific type of ethical climate (benevolent) within a socially and economically impactful industrial sector; (2) it incorporates a mediating mechanism (job autonomy) that elucidates how organizational values translate into emotional well-being; and (3) it does so in a nationally underexplored context, offering original empirical evidence from Latin America in a field predominantly shaped by studies from Anglo-Saxon and European contexts.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Benevolent Ethical Climate, Emotional Exhaustion, and Depersonalization

Burnout is a complex phenomenon that manifests itself when the emotional and psychological demands of the work environment consistently exceed the individual’s available resources. The two most critical dimensions of this condition—emotional exhaustion and depersonalization—are highly sensitive indicators of the deterioration of emotional bonds at work and the loss of subjective meaning in the task (Maslach et al., 2001; Maslach, 2003). While emotional exhaustion is expressed as a persistent feeling of internal fatigue and loss of motivational energy, depersonalization involves a progressive disconnection from others and one’s own professional role.

From this perspective, the organizational climate plays a fundamental role in modulating the psychosocial processes underlying burnout. In particular, a benevolent ethical climate—understood as an environment where values such as mutual aid, interpersonal care, and concern for collective well-being prevail—can act as a preventive barrier against emotional deterioration (Cullen et al., 1993; Blome & Paulraj, 2013; Santiago-Torner et al., 2025a, 2025b). Unlike ethical climates based on regulatory compliance or individual interest, the benevolent climate emphasizes human relationships, intragroup solidarity, and responsibility to the social environment (Victor & Cullen, 1988).

Numerous studies have suggested that organizations that promote interpersonal relationships based on empathy and respect significantly reduce levels of work stress and promote emotional commitment (McClelland et al., 2018; Rathert et al., 2022). In such contexts, work ceases to be an exclusive source of pressure and becomes a space where professionals perceive emotional recognition and moral validation. This reduces the likelihood of employees resorting to defensive mechanisms, such as emotional distancing or emotional cynicism, which are characteristic of depersonalization (Maslach & Leiter, 2016).

Resource conservation theory (RCT) (Hobfoll et al., 2018) offers a solid explanatory framework for understanding this process. According to this theory, people seek to conserve, accumulate, and protect their personal and social resources. When these are perceived as insufficient in the face of environmental demands, stress emerges. In this sense, a benevolent ethical climate can be interpreted as a contextual resource that provides emotional support, strengthens social bonds, and improves the individual’s ability to cope with adverse situations without experiencing a drastic loss of psychological resources.

Empirical evidence supports this approach. For example, Elçi et al. (2015) found that ethical climates oriented toward prosocial values moderate the relationship between perceived organizational justice and burnout. Similarly, recent studies identify a sense of community, group cohesion, and support among colleagues as protective factors that reduce the likelihood of emotional exhaustion (Rathert et al., 2022; Doolittle, 2021). Friendship in the workplace, as a component of a benevolent climate, functions not only as a support network but also as an active strategy for coping with emotional pressure (McClelland & Vogus, 2021).

Furthermore, when organizations integrate corporate social responsibility into their internal culture—that is, not just as an external projection—employees tend to develop a greater sense of purpose, which reinforces their intrinsic motivation and emotional resilience (Chen & Liu, 2023; Liu et al., 2023). In this context, depersonalization is minimized, as employees feel part of a mission with ethical meaning, rather than performing fragmented tasks unrelated to their values.

Consequently, it can be argued that organizational environments that promote a culture of care, mutual support, and community engagement not only facilitate subjective well-being but also create an affective environment that prevents the progression of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

A benevolent ethical climate is negatively associated with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Job Autonomy

Autonomy at work has become established as a key construct in the analysis of factors that affect employee psychological well-being. In general terms, it refers to the individual’s ability to organize their activities, make decisions about how to perform their tasks, and regulate the use of their time according to the priorities of the role they perform (Spreitzer, 1995; Sia & Appu, 2015). In work contexts marked by uncertainty, autonomy is not only a right but also an instrumental psychological resource that allows individuals to cope with demanding work requirements with a greater sense of control and self-efficacy.

According to self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2020), autonomy not only increases intrinsic motivation but also promotes emotional and cognitive self-regulation processes. In particular, when the work environment organizes its relationships around respect, participation, and recognition, professionals tend to experience greater self-direction, which enhances their commitment and reduces their vulnerability to emotional exhaustion. Along these lines, studies such as those by Fernet et al. (2013) and Guo et al. (2023) have shown that the degree of perceived autonomy acts as a buffer between stress and manifestations of burnout.

This work argues that autonomy not only acts as an independent variable but also constitutes an essential mediating mechanism in the relationship between a benevolent ethical environment and levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. This mediation is theoretically sound for two reasons. First, an ethical climate focused on collective well-being tends to build horizontal working relationships characterized by trust, reciprocity, and participation in decision-making (Fein et al., 2013). These conditions, in turn, create the psychosocial foundations necessary for autonomy to flourish as an everyday work experience.

Second, from the perspective of resource conservation theory (Hobfoll et al., 2018), autonomy is a highly adaptive resource that allows individuals to better manage their energy, identify priorities, and set limits in the face of disproportionate demands. By allowing for a strategic redistribution of effort, autonomy prevents professionals from being exposed to prolonged overload situations, thus reducing the risk of emotional fatigue and the need to adopt defensive attitudes such as depersonalization (Zhang & He, 2022; Matthews et al., 2018).

Empirically, recent research has confirmed that employees with greater job autonomy have a greater ability to regulate their emotions, establish positive coping strategies, and maintain a sense of purpose in the face of adverse working conditions (Kim et al., 2019; De Clercq & Brieger, 2022). This finding is especially relevant in environments such as the Colombian electricity sector, where the pressure to achieve energy transformation goals can generate additional tensions if there are not adequate margins for self-direction.

Thus, it is argued that a benevolent ethical climate creates the necessary conditions for job autonomy to emerge as an available resource, which in turn facilitates the balance between demands and capabilities, reducing the likelihood of experiencing emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. This mediation not only adds an explanatory nuance to the theoretical model but also allows for the identification of a specific organizational mechanism that is susceptible to intervention and improvement.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Job autonomy mediates the negative relationship between the benevolent ethical climate and the two dimensions of burnout. Specifically, the benevolent ethical climate is positively associated with autonomy, which in turn is negatively related to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

2.3. Research Model

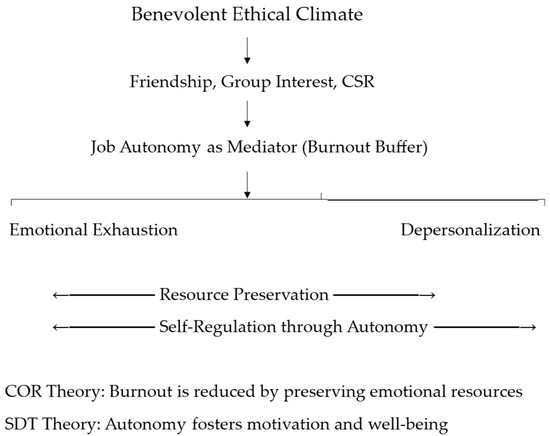

Based on the theoretical framework developed above, we propose an explanatory model that analyzes the direct effect of a benevolent ethical climate on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, considering the mediating role of job autonomy. This model is based on a dual conceptual framework: on the one hand, resource conservation theory (Hobfoll et al., 2018), which posits that individuals tend to protect and mobilize psychological resources in the face of stress; and on the other hand, self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2020), which highlights the adaptive value of autonomy in sustaining motivation and well-being in demanding environments.

From this perspective, it is proposed that a benevolent ethical climate constitutes a contextual organizational resource that can activate individual psychological resources, such as job autonomy. The latter, in turn, would allow employees to distribute their emotional energy more efficiently, reducing the negative impact of intense organizational demands. The model not only seeks to confirm direct relationships between variables, but also to explore an explanatory mechanism that adds depth to the understanding of the organizational processes that modulate burnout.

The proposed framework consists of three main paths: (1) a direct negative relationship between benevolent ethical climate and the two central dimensions of burnout (emotional exhaustion and depersonalization); (2) a positive relationship between benevolent ethical climate and job autonomy; and (3) a negative relationship between autonomy and the dimensions of burnout. The mediation of autonomy allows us to examine whether the protective effect of the benevolent climate operates wholly or partly through the strengthening of perceived self-direction. This model has significant theoretical and practical value, as it allows us to analyze how the ethical principles that shape the work environment can translate, through specific psychosocial mechanisms, into lower levels of emotional exhaustion. Unlike other approaches that focus solely on objective working conditions (such as workload or time pressure), this study incorporates subjective and moral variables, providing a richer and more nuanced understanding of the factors that explain organizational well-being.

Figure 1 represents the integration of SDT and COR theories as complementary lenses for understanding ethical climate, autonomy, and burnout.

Figure 1.

Integrated theoretical framework based on self-determination theory and conservation of resources theory.

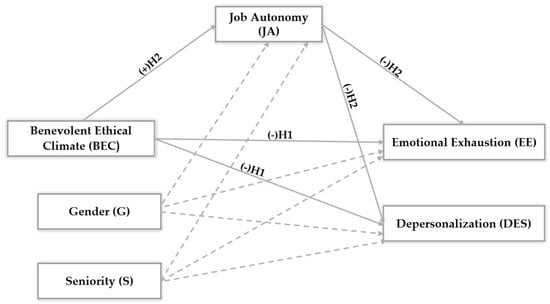

Figure 2 graphically summarizes the research model and the direction of the hypotheses proposed.

Figure 2.

Research model.

3. Method

3.1. Methodological Approach

This study adopts a quantitative empirical strategy, aimed at analyzing causal relationships through a non-experimental, cross-sectional design. The research is framed within an explanatory model, supported by mediation analysis using structural equations with bootstrapping estimates. This procedure allowed us to test a theoretical model that posits a negative association between a benevolent ethical climate and two key indicators of burnout syndrome—emotional exhaustion and depersonalization—considering job autonomy as an intervening mechanism.

3.2. Sample and Context

The target population consisted of professionals linked to the electricity sector in Colombia, in the particular context of teleworking. A stratified cluster probability sample was selected, consisting of 448 participants (61.4% men and 38.6% women), whose average age was 37 years (range between 20 and 69 years). A total of 13.4% of respondents performed direct supervisory functions. The sample included different hierarchical levels: senior management (4.5%), middle management (8.9%), analysts (68.8%), and support staff (17.8%). The average length of service in the organization was 10 years. All subjects had a university education, and 60% had postgraduate studies, which reinforces the validity of the analysis as these are highly qualified profiles.

3.3. Procedure

The information was collected between January and March 2022, with the endorsement of an independent ethics committee, approved in June 2021. Access to the organizations was managed through institutional presentations made to the sector’s community action committees, where the objectives, scope, and guarantees of the study were presented. Voluntary and anonymous participation was guaranteed, in accordance with current regulations on confidentiality and personal data protection. Each organization received informed consent documents, voluntary withdrawal protocols, and agreements on the responsible use of information. The questionnaire was administered through the Microsoft Forms platform. Participants responded synchronously in sessions differentiated by functional unit, lasting approximately 35 min. Prior to completing the instrument, the principal investigator gave a brief introduction (5 min), highlighting the overall objective of the research as well as the importance of reflecting carefully before giving each answer.

3.4. Measurement of Variables: Contextual Justification and Cultural Validity

The validity of a psychometric instrument depends not only on its internal structure, but also on its suitability for the social and work context in which it is applied. In this study, all the scales used were selected for their solid empirical track record and their high relevance to the Colombian electricity sector, which is characterized by demanding working conditions, high operational technification, and strict safety regulations.

The benevolent ethical climate scale allows for the evaluation of perceptions of organizational norms focused on well-being, fair treatment, and mutual care. In an environment such as the electricity sector, where decisions have critical human and environmental implications, a benevolent ethical climate is directly linked to the prevention of psychosocial distress and the consolidation of more resilient organizational cultures.

The work autonomy scale measures the degree of control and self-direction perceived by workers. In the Colombian electricity sector, where routine tasks and highly responsible technical functions coexist, this dimension is key to assessing the responsiveness and adaptability of personnel to operational contingencies, particularly in a context of energy transition and digital transformation.

Finally, the burnout scale captures the cumulative psychological wear and tear of intense work demands. In this sector, where employees face physical risks, long shifts, and pressure to perform, burnout is a critical indicator of psychosocial risk and a strategic variable in human talent management.

Sociodemographic control variables. In order to control for the variance explained by individual factors, gender (0 = male; 1 = female) and length of service in the organization, measured in years, were included as exogenous control variables. The scales used in the study employed a six-point Likert format, with anchors ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

Benevolent ethical climate. This variable was assessed using a subscale adapted from the Ethical Climate Questionnaire (Victor & Cullen, 1988), which considers three structural components, namely, friendship (3 items), group orientation (4 items), and corporate social responsibility (4 items), for a total of 11 items. A representative example of the items is as follows: “In this company, our main concern is always what is best for others.” The original instrument reports an α = 0.85, and in this research, the reliability index reached α = 0.88.

Job autonomy. For this variable, the unidimensional scale proposed by Spreitzer (1995) was used, consisting of three items, such as “I can decide for myself how to do my job.” The scale assesses the perception of control and self-direction in the execution of tasks within organizational limits. The Cronbach’s alpha obtained was 0.87, higher than that originally reported (α = 0.72).

Emotional exhaustion. This was measured with five items from the Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey adapted by Schaufeli et al. (1996). An example of an item is as follows: “I am emotionally exhausted at work.” Internal consistency reached α = 0.90 (original α = 0.85).

Depersonalization. The four-item scale developed by Salanova and Schaufeli (2000) was used, including “I have become more cynical about the usefulness of my work.” The internal reliability of this scale was 0.90 in this sample (original α = 0.78).

3.5. Data Analysis

Data processing was carried out using SPSS software (version 27), using the PROCESS macro developed by Hayes (2018), specifically the simple mediation model 4. A bootstrapping resampling procedure with 10,000 iterations and a 95% confidence interval was applied to estimate the direct, indirect, and total effects of the proposed relationships. The PROCESS macro was used instead of other alternative SEM software (version 2024.2) for multiple reasons. First, the main strength of PROCESS lies in its ability to estimate mediation effects without requiring the creation of complex path diagrams. Second, various authors show identical results between PROCESS and SEM (Hayes, 2015). Before estimating the mediation model, the statistical assumptions associated with multiple regression analysis were verified. The normality and linearity of the distributions were evaluated using the kurtosis and skewness indices. Possible outliers were identified using Mahalanobis distance (Aguinis et al., 2017). In addition, multivariate normality was assessed. The results indicated that, although slight deviations from ideal normality were observed, these did not compromise the stability or validity of the factorial solutions obtained. Likewise, the influence of outliers was statistically controlled, with no significant distortions detected in the estimated parameters. The presence of multicollinearity was ruled out by verifying that the VIF index values were less than 10, and the condition index (CI) values did not exceed the critical threshold of 30. This methodological strategy allowed us to rigorously estimate the magnitude of the mediating effects of job autonomy on the relationship between benevolent ethical climate and indicators of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, controlling for the effects of gender and seniority.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

In order to explore the general patterns in the distribution of the data and establish preliminary relationships between the variables in the model, the fundamental descriptive measures were calculated: mean (M), standard deviation (SD), and Pearson correlations between the latent variables and their respective dimensions. Regarding the control variables, the analyses revealed that gender in the organization did not show significant correlations with any of the central variables of the study, while seniority showed a weak but statistically significant relationship only with emotional exhaustion (r = 0.129; p < 0.001), suggesting a minimal influence on emotional exhaustion processes.

Regarding the benevolent ethical climate, both the global variable and its three dimensions (friendship, interest in the group, and corporate social responsibility) correlated positively with job autonomy and, simultaneously, showed negative associations with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. These preliminary findings support the theoretical premise that an ethical environment oriented toward care and solidarity promotes the perception of self-direction at work, while mitigating adverse emotional reactions. For its part, job autonomy exhibited a significant inverse correlation with both dimensions of burnout, suggesting its role as a protective factor against emotional deterioration. These correlations also support the validity of the proposed mediation hypothesis, which posits that autonomy acts as an explanatory mechanism between the ethical climate and the professional’s affective outcomes.

The discriminant validity of the constructs was also verified through cross-correlation analysis, observing that all variables showed higher correlations with themselves (diagonal; in bold) than with any other construct, which meets the criteria established by Fornell and Larcker (1981). The correlation values are presented in Table 1, along with the descriptive statistics for each scale.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, correlations, and discriminant validity between constructs.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

To validate the structure of the measurement model, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed, which is a rigorous statistical strategy aimed at validating hypotheses about the underlying structure of latent constructs through the empirical adjustment of a pre-specified theoretical model. This technique allows the structural validity of the model to be evaluated through fit indicators such as RMSEA, RMR, GFI, NFI, NNFI, CFI, IFI, and RFI, whose values provide evidence of the model’s adequacy to the observed covariance matrix (Sureshchandar, 2023). In this study, the analysis performed using AMOS v. 25 revealed a satisfactory fit (χ2 = 495.30; CFI = 0.91; IFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.06; NFI = 0.92; GFI = 0.93), which supports the validity of the proposed measurement model in accordance with established international standards (Byrne, 2001).

This initial descriptive approach, together with evidence of significant relationships in the expected theoretical direction, provides a solid basis for proceeding with the analysis of reliability, structural validity, and hypothesis testing.

4.2. Reliability and Validity of the Instruments

In order to ensure the psychometric accuracy of the measurements used, the levels of internal consistency, as well as the convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs included in the model, were evaluated. This procedure is essential to confirm that the selected scales robustly capture the underlying theoretical dimensions and that the indicators do not overlap between different factors.

4.2.1. Internal Consistency

The reliability of each scale was estimated using Cronbach’s α coefficient. Following the criteria of Bonett and Wright (2015), values equal to or greater than 0.70 are considered to indicate acceptable consistency. In all cases, the coefficients obtained were within optimal ranges: benevolent ethical climate (α = 0.88), job autonomy (α = 0.87), emotional exhaustion (α = 0.90), and depersonalization (α = 0.90). These figures indicate a high degree of homogeneity among the items that make up each factor, even exceeding the reference values reported in the original validation studies (Victor & Cullen, 1988; Spreitzer, 1995; Schaufeli et al., 1996; Salanova & Schaufeli, 2000).

4.2.2. Convergent Validity

To analyze convergent validity, three key indicators were calculated: composite reliability (CR), critical coefficient (CC), and average variance extracted (AVE). According to Hair et al. (2011), composite reliability values are expected to exceed 0.70 and AVE to be equal to or greater than 0.50. In this study, composite reliability scores ranged from 0.72 to 0.86, while AVE ranged from 0.38 to 0.80. Although some dimensions had AVE values slightly below the ideal threshold, these were considered acceptable given the theoretical support of the constructs and the robustness of their factor loadings (Chin, 1998).

4.2.3. Discriminant Validity

This study evaluated discriminant validity (the degree of differentiation of items between constructs or the measurement of individual concepts) using two main criteria. First, discriminant validity was verified using the parameters established by Fornell and Larcker (1981), who consider that if the square root of the AVE of a construct is greater than the correlation between that construct and any other construct in the model, then discriminant validity exists between them. This requirement was met for all pairs of variables in the model, indicating that the measured factors represent distinct conceptual dimensions without significant overlap. In addition, the factor loadings of all items exceeded the threshold of 0.50, reinforcing the suitability of the factor structure of the scales (Bagozzi et al., 1998). (See bold diagonal Table 1 and also Table 2).

Table 2.

General validity of the constructs.

Second, to ensure the robustness of discriminant validity, the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio criterion was used (Henseler et al., 2015). According to HTMT, discriminant validity exists when all HTMT ratio values are less than 0.85 (Kline, 2010). As shown in Table 3, the HTMT ratio of each indicator against its respective indicator was less than 0.85, indicating discriminant validity between indicators.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity via HTMT criterion.

Table 2 presents a summary of the reliability coefficients (α and CR), extracted variance (AVE), and discriminant validity between constructs.

Taken together, these results indicate that the scales used possess solid psychometric properties and are suitable for inclusion in the mediation analysis model. This assessment ensures the statistical reliability of subsequent results and strengthens the validity of the inferences derived from hypothesis testing.

4.3. Hypothesis Analysis and Mediation Process

The proposed model was tested using a simple mediation analysis, employing the stepwise regression procedure integrated in the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 4), developed by Hayes (2018). This approach allowed for the simultaneous examination of the direct and indirect effects of a benevolent ethical climate on the two indicators of burnout considered—emotional exhaustion and depersonalization—incorporating job autonomy as a mediating variable. To ensure robust estimations, a non-parametric resampling method (bootstrapping) with 10,000 iterations was applied, computing 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. This technique is particularly suitable for detecting significant mediation effects even in the presence of non-normal distributions and has been extensively validated in studies with complex psychometric models (Hayes, 2018).

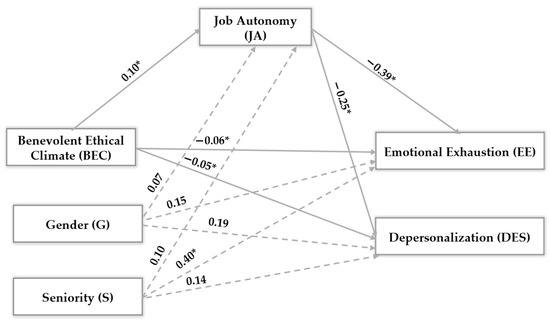

4.3.1. Direct Effects

Hypothesis 1 (H1) posits that a benevolent ethical climate mitigates the negative effects leading to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. The linear regressions corresponding to the c’ effects of Model 2 (β = −0.060; SE = 0.030; p < 0.05) and Model 3 (β = −0.049; SE = 0.023; p < 0.05) support this proposition and provide empirical validation for H1.

4.3.2. Indirect Effects—Mediation

The mediation analysis revealed that job autonomy functions as an explanatory mechanism in both pathways of the model. First, a significant positive relationship was found between a benevolent ethical climate and autonomy in Model 1—effect ai—(β = 0.097; SE = 0.013; p < 0.05), suggesting that environments characterized by solidarity and care foster perceptions of self-direction. Second, autonomy was negatively associated with both emotional exhaustion in Model 2—effect bi—(β = −0.394; SE = 0.102; p < 0.05) and depersonalization in Model 3—effect bi—(β = −0.249; SE = 0.068; p < 0.05), supporting its buffering role against organizational stress. Mediation was confirmed as the indirect effects of ethical climate on burnout through autonomy were statistically significant in Model 2 (β = −0.038; SE = 0.013; 95% CI [−0.068, −0.015]) and Model 3 (β = −0.024; SE = 0.009; 95% CI [−0.044, −0.008]). Since the confidence intervals did not include zero, Hypothesis 2 (H2) was empirically supported. Mediation was complete, as the direct effects of ethical climate on both burnout variables remained significant after including the mediator, indicating that the model integrates both direct and indirect pathways.

Figure 3 presents the final model with the standardized coefficients for each path, while Table 4 summarizes the direct, indirect, and total effects with their respective significance levels.

Figure 3.

Results of the regression analysis. The figure shows the proposed statistical diagram of simple mediation. * Statistical significance.

Table 4.

Mediation analysis results.

Together, these findings support the idea that ethical environments not only directly impact employees’ emotional well-being but also activate key personal resources—such as autonomy—that enhance resilience against work-related strain. This integrative perspective contributes to a more dynamic understanding of the factors that modulate burnout in complex organizational contexts.

5. Discussion

This research examined the effect of a benevolent ethical climate on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, considering job autonomy as a mediating mechanism. The results support both proposed hypotheses. This study makes a significant contribution to the existing literature as one of the first analyses confirming the buffering effect of a benevolent climate on emotional resource depletion, thereby addressing specific knowledge gaps on the topic.

H1 confirms that a benevolent climate prevents the progression of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. A supportive and inclusive climate compensates for the loss of employees’ psychological resources (Li & Peng, 2022). Paying attention to emotions and creating a setting that reduces conflict serves as a useful guide for professionals. In fact, an atmosphere grounded in collective interest and strong relationships significantly reduces negative behaviors and feelings among employees; that is, it becomes an additional psychological resource that helps to effectively cope with stressful situations.

According to COR theory, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization result from a continuous drain of emotional resources without timely replenishment (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Therefore, friendship at work is a key element in the social exchange system of any organization, as it provides valuable emotional resources (Rathert et al., 2022). Friendship becomes a coping strategy that alleviates stress. Improved communication, shared values and experiences, along with open and honest exchange, likely enhance psychological and social well-being (McClelland et al., 2018). Moreover, mutual trust and understanding are critical psychosocial variables that can positively reshape emotional conflicts typically leading to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Doolittle, 2021).

Additionally, the collective interest promoted by a benevolent climate helps prevent mismatches between job demands and resources. Fostering psychologically safe spaces at work plays a prominent role in preventing emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Rathert et al., 2022). The social support provided by a benevolent climate stimulates interpersonal interactions and prevents emotional isolation. In fact, it intentionally seeks psychosocial support through environments of empathy and reciprocity (Santiago-Torner, 2023d).

Finally, the corporate social responsibility promoted by a benevolent ethical climate significantly reduces the likelihood of employee emotional exhaustion. COR theory suggests that alignment between organizational and employee values, along with the perception that social responsibility reflects a life purpose, prevents resource loss and the negative emotions associated with such deterioration (Chen & Liu, 2023). A climate with a clear community orientation is indeed a contextual resource that prevents employees from feeling overwhelmed, thereby radically reducing the likelihood of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Liu et al., 2023).

Secondly, H2 confirms the mediating effect of job autonomy on the relationship between benevolent ethical climate, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization, significantly expanding the previous literature on ethical climates and burnout (Li & Peng, 2022; Rivaz et al., 2020; Sahi et al., 2022; Saleh et al., 2022).

This finding suggests that a climate centered on collective well-being grants employees responsibility and initiative. In fact, a benevolent ethical climate is built through a horizontal structure that respects employee opinions and identifies work areas that promote collaborative, positive, and efficient performance supported by continuous communication (Kim et al., 2019; Santiago-Torner et al., 2024). Voluntarily accepting certain responsibilities tends to increase job satisfaction. The concept of autonomy goes beyond merely redistributing daily tasks; expanding opportunities for self-management and considering employees’ input is an organizational opportunity to reduce conflict, increase belonging, and avoid burnout risks (Kim et al., 2019). Additionally, job autonomy is a resource that enables a better work–life balance (De Clercq & Brieger, 2022). According to COR theory, the ability to structure and direct work activities suggests a process of resource gain. Autonomy is a key variable that offsets high demands by providing control over them, thus mitigating role stress, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization (Charoensukmongkol, 2022).

A benevolent work climate that encourages individual initiative, reduces tension and uncertainty, provides ongoing feedback, and identifies employees’ feelings positively impacts their emotional functioning by satisfying basic needs. The ability to direct psychological resources likely involves a series of motivational and energetic processes that prevent affective blockage stemming from emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Fernet et al., 2013).

This study offers an original contribution in at least four key dimensions:

It deepens the link between organizational ethics and emotional health, integrating two traditionally separate fields of study. Unlike most previous research, which has explored ethics from a behavioral or normative perspective, this study demonstrates that ethically benevolent climates not only regulate behavior but also protect workers’ emotional integrity (Santiago-Torner, 2023c).

It introduces a relational mediation model, where autonomy is not merely a job design feature but a psychological experience emerging from the ethical environment. In this sense, the study reconceptualizes autonomy as a relational condition nurtured by respect, trust, and perceived fairness in everyday work relationships.

It situates the research in an empirically relevant and underexplored context: the Colombian electricity sector. This field has historically been approached from technical or engineering perspectives, with little attention to the psychosocial and ethical factors affecting human talent sustainability.

It proposes a conceptual framework that articulates conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll et al., 2018) with self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2020), providing a solid theoretical foundation for future research seeking to integrate ethics, autonomy, and well-being in complex models.

On the other hand, although the results of the present study align with prior research emphasizing the protective role of a benevolent ethical climate and job autonomy in mitigating emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, the empirical literature presents a more nuanced picture. Several studies have identified limited or non-significant effects of ethical climate on psychological well-being, particularly when discrepancies exist between an organization’s stated ethical norms and the actual behaviors of its leaders or supervisors (Mayer et al., 2010; Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2021). In such cases, the so-called “symbolic ethical climate” may generate cognitive dissonance among employees, thereby nullifying the climate’s potential buffering effect against burnout.

Furthermore, the universal benefits of job autonomy have been questioned in the recent literature. For instance, Van den Broeck et al. (2014) and more recently Slemp et al. (2021) suggest that in contexts characterized by high uncertainty or role ambiguity, autonomy may become an additional source of stress by increasing employees’ perceived responsibility for complex or ambiguous demands. In this sense, autonomy does not operate as a protective resource per se; rather, its effectiveness is contingent upon factors such as perceived competence, organizational support, and value congruence (Deci et al., 2017).

Nonlinear relationships have also been documented between ethical climate and emotional exhaustion. Some studies warn that a climate overly focused on collective well-being can produce emotional overload due to prosocial pressure or excessive ethical self-demand (De Gieter et al., 2018). In such cases, employees may experience “empathic fatigue” stemming from the constant expectation to care for others. This paradoxical effect highlights the importance of considering saturation mechanisms or the potential reversal of benefits in climates perceived as excessively normative.

Therefore, although these findings are consistent with the dominant literature on the positive effects of benevolent ethical climate and autonomy, a critical perspective is necessary—one that acknowledges the boundary conditions of their effectiveness, the possibility of unintended consequences, and the contextual variables that may alter or even reverse the observed effects.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge alternative explanations for the findings and certain factors that may have influenced the results. Although the proposed theoretical model is solidly grounded in conservation of resources theory (COR) and self-determination theory (SDT), it is methodologically relevant to consider potential alternative explanations that may have affected the observed outcomes. A first omitted variable is supervisor support, which has been extensively documented as a key moderator of the effects of the organizational environment on emotional well-being (Eisenberger et al., 2020). It is plausible that part of the effect attributed to ethical climate or autonomy was mediated by employees’ perceived closeness to or support from their immediate supervisors—an aspect that was not controlled for in this study.

Another plausible explanation involves employees’ psychological capital (Chaffin et al., 2023). Constructs such as self-efficacy, optimism, resilience, and hope may interact with organizational conditions, either amplifying or buffering their impact on burnout. Employees with high levels of personal resources may derive greater benefit from benevolent or autonomous environments, whereas those with lower resource levels may not experience the same protective effects, even under favorable organizational conditions.

In addition, the role of work–family conflict and person–organization fit (PO fit) was not considered, despite both being closely associated with emotional exhaustion and frequently linked to perceptions of autonomy or ethical climate (Lee et al., 2023). These contextual factors may offer plausible alternative explanations, particularly in sectors such as the electric power industry, where job demands are high and work schedules may interfere with personal and family life.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings support meaningful conceptual advancements for organizational and psychosocial research:

Toward an Ethics of Organizational Care. The results suggest that a benevolent ethical climate should be understood as a form of institutionalized ethics of care, where affective relationships, solidarity, and a sense of community are not soft or peripheral dimensions but rather core structural components of occupational health. This perspective challenges traditional approaches centered on rules and sanctions and opens the door to more humanistic models of work.

Autonomy as an Emergent Outcome. Job autonomy should not be treated exclusively as an exogenous or structural variable but rather as an emergent experience shaped by the moral and social environment of work. This conceptual shift invites a rethinking of organizational design from an ethical—not merely functional—standpoint.

Integration of Ethics and Mental Health in Predictive Models. The findings indicate that organizational ethics not only predict behaviors such as satisfaction or loyalty but also act as a protective factor for mental health. This connection opens new pathways to incorporate ethics as a key predictor in complex psychosocial models.

5.2. Practical Implications

From an applied perspective, the results offer concrete guidelines for the redesign of organizational policies, particularly within the Colombian electricity sector, which faces high operational demands, exposure to psychosocial risks, and the need for sustained innovation.

Embedding Benevolence into Organizational Culture: Incorporating benevolence into organizational culture requires moving beyond declarative ethical commitments and integrating care-based principles into operational protocols and managerial routines. In the Colombian electricity sector, this implies developing ethical infrastructures that actively promote interpersonal support, psychosocial safety, and dignity at work. Practical actions may include the formalization of affective mentoring programs for field engineers and technical staff, conflict mediation protocols based on empathy and restorative dialog, and the systematic inclusion of prosocial behaviors in performance evaluations. Additionally, fostering cross-functional support networks—particularly in geographically dispersed or high-risk operational units—can enhance solidarity and reduce emotional isolation in challenging work environments.

Promoting Structures that Strengthen Relational Autonomy: Job design must be reconceptualized to ensure that autonomy is not solely technical or hierarchical but relational and inclusive. In the context of the Colombian electricity sector, where rigid operational hierarchies and regulatory constraints prevail, organizations should establish participatory planning forums, collaborative problem-solving teams, and flexible task allocation systems that empower employees at all levels. Ensuring equitable access to decision-making mechanisms is especially relevant for operational crews and regional maintenance teams, whose roles are traditionally excluded from strategic deliberation. Promoting relational autonomy under these conditions contributes not only to employee well-being but also to organizational agility and adaptive capacity in the face of sectoral transitions.

Reframing Burnout Prevention Programs: Traditional burnout prevention strategies tend to focus on individual stress management techniques. However, this research calls for a paradigmatic shift toward collective ethical-preventive models. In the electricity sector, this involves redesigning psychosocial risk assessments to include dimensions such as ethical climate quality, perceived fairness, and emotional inclusiveness. Organizations should embed indicators of relational ethics into workplace climate surveys and use the results to inform leadership development, health and safety programs, and organizational communication protocols. Moreover, HR departments should be equipped to detect and address early warning signs of moral distress or emotional erosion, especially in high-demand operational units (Santiago-Torner, 2024b, 2024c).

Applicability to Transforming Sectors: The Colombian electricity sector is undergoing significant transformations driven by decarbonization efforts, digital innovation, and regulatory modernization. In this dynamic landscape, ethically grounded organizational climates provide the emotional and cognitive infrastructure required for successful change management. By fostering environments of mutual trust and collective purpose, companies can mobilize internal commitment to transformation while mitigating the psychological toll associated with uncertainty and increased performance pressures. In practice, this means anchoring transition processes in inclusive dialogs, value-based leadership, and systemic care for employees’ emotional health—thus replacing individualized adaptation demands with collective resilience strategies.

Finally, the findings obtained can serve as strategic input for the design of management training programs based on ethical competencies. Leadership training should include specific modules on promoting benevolent organizational climates, with an emphasis on active listening, the emotional management of the team, and shared responsibility in decision-making. Likewise, labor policies can incorporate indicators of ethical climate and autonomy as key criteria in performance evaluations, 360° feedback, and internal promotion. In this way, well-being is not only institutionalized as an organizational value, but also becomes a sustainable practice that strengthens commitment, talent retention, and mental health at work.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although the findings of this study provide solid empirical evidence and a novel explanatory model regarding the role of a benevolent ethical climate in burnout prevention, it is important to acknowledge certain methodological and conceptual limitations that delimit the scope of the inferences and open new pathways for future research.

First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish definitive causal relationships between the variables analyzed. While the observed associations are consistent with existing theoretical and empirical research, future studies could adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to explore how experiences of autonomy and emotional exhaustion vary in relation to perceived changes in ethical climate over time.

Second, data were collected through self-report measures, which may have introduced biases related to social desirability or subjective perceptions. Although statistical controls were implemented to minimize these effects, future research would benefit from triangulated data sources, such as third-party evaluations or objective indicators of occupational health.

A third limitation concerns the specific sectorial and geographical context. The study was conducted exclusively in the Colombian electricity sector, which, while providing contextual relevance and depth, restricts the generalizability of the findings to other economic sectors or countries with different cultural dynamics. Future studies could replicate this model in diverse industrial contexts, or even in public and third-sector organizations, to assess its cross-cultural and functional validity.

An additional limitation of the study is the exclusion of the dimension of reduced personal fulfillment in burnout syndrome. This methodological decision was based on solid evidence that considers this dimension to be a consequence of the combination of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, rather than an independent component. However, its inclusion could offer a more comprehensive view of the phenomenon. Future research should consider an expanded model that integrates this third dimension, exploring whether a benevolent ethical climate and job autonomy influence the perception of professional competence and sense of achievement, key elements for complete emotional recovery.

Further studies could explore new mediating or moderating variables that may enrich the model, such as perceived self-efficacy, leadership quality, or organizational identity. These variables could help explain more precisely the conditions under which an ethical environment enhances emotional well-being or, conversely, loses its efficacy in structurally high-pressure contexts.

Future lines of research should also consider advanced methodological approaches such as latent growth modeling or cross-lagged panel designs, which allow for a more nuanced examination of the temporal dynamics between ethical climate, autonomy, and burnout. Additionally, multi-level modeling could be used to disentangle individual- and team-level effects, particularly in organizations where ethical climate is shaped by both top–down policies and localized leadership practices. Further inquiries may also benefit from qualitative or mixed methods designs, including in-depth interviews or focus groups, to capture the subjective meanings that employees assign to ethical practices and emotional experiences in their specific work environments. Finally, future research should explore how macro-level factors—such as institutional trust, labor policy, and national ethical standards—interact with organizational climate to influence employee well-being, especially in emerging economies and high-risk sectors like energy and infrastructure.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a benevolent ethical climate is not only a desirable normative framework but also a critical organizational resource for the emotional protection of workers. Through a mediation model incorporating job autonomy as an explanatory mechanism, the study shows that organizations promoting values of mutual care, social responsibility, and cooperation significantly reduce levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

From a theoretical perspective, this work proposes a reinterpretation of burnout as a phenomenon that is not exclusively individual but profoundly conditioned by the moral environment in which work practices are embedded. The study provides an integrative model that connects organizational ethics, motivational psychology, and occupational health, thereby opening new avenues for interdisciplinary dialog and emerging lines of research.

From a practical standpoint, the findings call for a rethinking of burnout prevention strategies, prioritizing the ethical redesign of the work environment as a sustainable path to preserving well-being. It is not only about intervening at the individual level but about transforming the relational structures that shape emotional experience at work.

In summary, this study offers an original, rigorous, and socially relevant theoretical and empirical contribution, demonstrating that an ethically committed work environment can act as a protective barrier against emotional exhaustion by activating key psychosocial resources such as autonomy. This finding reinforces the need to conceive ethics not merely as a normative aspiration, but as a necessary condition for organizational well-being.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by The UVic-UCC Research Ethic Committee (protocol code: 170/2021; 20 July 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguinis, H., Edwards, J. R., & Bradley, K. J. (2017). Improving our understanding of moderation and mediation in strategic management research. Organizational Research Methods, 20(4), 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, A., Khan, A. J., Ahmed, T., & Ansari, M. A. A. (2022). Examining the relationship between ethical climate and burnout using role stress theory. Review of Education, Administration & LAW, 5(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Nassen, K. D. (1998). Representation of measurement error in marketing variables: Review of approaches and extension to three-facet designs. Journal of Econometrics, 89(1–2), 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellou, V., & Chatzinikou, I. (2015). Preventing employee burnout during episodic organizational changes. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(5), 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, C., & Paulraj, A. (2013). Ethical climate and purchasing social responsibility: A benevolence focus. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(3), 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, D. G., & Wright, T. A. (2015). Cronbach’s alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. International Journal of Testing, 1(1), 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, T. D., Luthans, B. C., & Luthans, K. W. (2023). Integrity, positive psychological capital and academic performance. Journal of Management Development, 42(2), 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, P. (2022). Supervisor-subordinate guanxi and emotional exhaustion: The moderating effect of supervisor job autonomy and workload levels in organizations. Asia Pacific Management Review, 27(1), 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R., & Liu, W. (2023). Managing healthcare employees’ burnout through micro aspects of corporate social responsibility: A public health perspective. Frontiers in Public Health, 10(1), 1050867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–358). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah, K. P., & Victor, B. (2003). The effects of ethical climates on organizational commitment: A two-study analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 46, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Bronson, J. W. (1993). The ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychological Reports, 73(2), 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D., & Brieger, S. A. (2022). When discrimination is worse, autonomy is key: How women entrepreneurs leverage job autonomy resources to find work–life balance. Journal of Business Ethics, 177(3), 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gieter, S., Hofmans, J., & Bakker, A. B. (2018). Need satisfaction at work, job strain, and performance: A diary study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(3), 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, B. R. (2021). Association of burnout with emotional coping strategies, friendship, and institutional support among internal medicine physicians. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 28(2), 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., Rhoades Shanock, L., & Wen, X. (2020). Perceived organizational support: Why caring about employees counts. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7(1), 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elçi, M., Karabay, M. E., & Akyüz, B. (2015). Investigating the mediating effect of ethical climate on organizational justice and burnout: A study on financial sector. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 207, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faelens, A., Claeys, M., Sabbe, B., Schrijvers, D., & Luyten, P. (2013). Ethical climate in a Belgian psychiatric inpatient setting: Relation with burnout and engagement in psychiatric nurses. European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare, 1(2), 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fein, E. C., Tziner, A., Lusky, L., & Palachy, O. (2013). Relationships between ethical climate, justice perceptions, and LMX. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 34(2), 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C., Austin, S., Trépanier, S.-G., & Dussault, M. (2013). How do job characteristics contribute to burnout? Exploring the distinct mediating roles of perceived autonomy, competence, and relatedness. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(2), 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C., Lavigne, G. L., Vallerand, R. J., & Austin, S. (2014). Fired up with passion: Investigating how job autonomy and passion predict burnout at career start in teachers. Work & Stress, 28(3), 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., Hancock, J., Cooper, D., & Caldas, M. (2023). Job autonomy and employee burnout: The moderating role of power distance orientation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 32(1), 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. J., Bhatti, M. A., Hussain, A., Ahmad, R., & Iqbal, J. (2021). Employee job satisfaction in higher educational institutes: A review of theories. Journal of South Asian Studies, 9(3), 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B., Liu, L., Ishikawa, H., & Park, S.-H. (2019). Relationships between social support, job autonomy, job satisfaction, and burnout among care workers in long-term care facilities in Hawaii. Educational Gerontology, 45(1), 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, F. C., Diefendorff, J. M., Nolan, M. T., & Trougakos, J. P. (2023). Emotional exhaustion across the workday: Person-level and day-level predictors of workday emotional exhaustion growth curves. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(10), 1662–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, C., Kohlberg, L., & Hewer, A. (1985). The current formulation of Kohlberg’s theory and a response to critics. Human Development, 28(2), 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Peng, P. (2022). How does inclusive leadership curb workers’ emotional exhaustion? The mediation of caring ethical climate and psychological safety. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 877725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y., Cherian, J., Ahmad, N., Han, H., de Vicente-Lama, M., & Ariza-Montes, A. (2023). Internal corporate social responsibility and employee burnout: An employee management perspective from the healthcare sector. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C. (2003). Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, L., Beeler, L., Zablah, A. R., & Hair, J. F. (2018). All autonomy is not created equal: The countervailing effects of salesperson autonomy on burnout. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 38(3), 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., & Greenbaum, R. L. (2010). Examining the link between ethical leadership and employee misconduct: The mediating role of ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, L. E., Gabriel, A. S., & DePuccio, M. J. (2018). Compassion practices, nurse well-being, and ambulatory patient experience ratings. Medical Care, 56(1), 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, L. E., & Vogus, T. J. (2021). Infusing, sustaining, and replenishing compassion in health care organizations through compassion practices. Health Care Management Review, 46(1), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, J. F., & Locander, W. B. (2008). Effect of ethical climate on turnover intention: Linking attitudinal-and stress theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(4), 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdoba, P., Dziurka, M., Pilewska-Kozak, A., & Dobrowolska, B. (2022). Hospital ethical climate and job satisfaction among nurses: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathert, C., Ishqaidef, G., & Porter, T. H. (2022). Caring work environments and clinician emotional exhaustion. Health Care Management Review, 47(1), 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivaz, M., Asadi, F., & Mansouri, P. (2020). Assessment of the relationship between nurses’ perception of ethical climate and job burnout in intensive care units. Investigación y Educación En Enfermería, 38(3), e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., Martínez-Cañas, R., & Bañón-Gomis, A. (2021). Is unethical leadership a negative for Employees’ personal growth and intention to stay? The buffering role of responsibility climate. European Management Review, 18(4), 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, G. K., Roy, S. K., & Singh, T. (2022). Fostering engagement among emotionally exhausted frontline employees in financial services sector. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 32(3), 400–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2000). Exposure to information technology and its relation to burnout. Behaviour & Information Technology, 19(5), 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T. A., Sarwar, A., Islam, M. A., Mohiuddin, M., & Su, Z. (2022). Effects of leader conscientiousness and ethical leadership on employee turnover intention: The mediating role of individual ethical climate and emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 8959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023a). Ethical leadership and creativity in employees with University education: The moderating effect of high intensity telework. Intangible Capital, 19(3), 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023b). Relación entre liderazgo ético y motivación intrínseca: El rol mediador de la creatividad y el múltiple efecto moderador del compromiso de continuidad. Revista de Métodos Cuantitativos para la Economía y la Empresa, 36(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023c). Selfish ethical climate and teleworking in the Colombian electricity sector. The moderating role of ethical leadership. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 26(2), 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023d). The influence of teleworking on creative performance by employees with high academic training: The mediating role of work autonomy, self-efficacy, and creative self-efficacy. Revista Galega de Economía, 32(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2024a). Clima ético benevolente y autoeficacia laboral. La mediación de la motivación intrínseca y la moderación del compromiso afectivo en el sector eléctrico colombiano. Lecturas de Economía, (101), 235–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2024b). Creativity and emotional exhaustion in virtual work environments: The ambiguous role of work autonomy. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(7), 2087–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2024c). Teletrabajo y autoeficacia laboral: El papel moderador de la creatividad y el mediador de la motivación intrínseca. Innovar, 34(91), e102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., Corral-Marfil, J. A., & Tarrats-Pons, E. (2024). The relationship between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion in a virtual work environment: A moderated mediation model. Systems, 12(11), 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., González-Carrasco, M., & Miranda-Ayala, R. (2025a). Relationship between ethical climate and burnout: A new approach through work autonomy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]