1. Introduction

Virtual interactivity in marketing has evolved significantly in recent decades, becoming an essential tool for effectively connecting with consumers in digital environments (

Nguyen & Hoang, 2024;

Yan et al., 2024). Through interactive digital platforms, brands can generate a two-way dialogue with their customers, allowing them to obtain instant feedback and adapt their strategies quickly and effectively (

Arora & Banerji, 2024;

Sawhney et al., 2024). This not only improves but also contributes to strengthening brand image and fostering long-term loyalty. In contrast, relationship marketing (RM) provides an important and direct connection between the customer and the brand (

Obaze et al., 2023). This allows for improvements in organizational development (

Perišić et al., 2022), brand value (

Olivares et al., 2018), marketing development (

Mulyana et al., 2020) and customer loyalty (

Suarniki & Lukiyanto, 2020).

The way the world interacts today is also transforming the way brands interact with their customers (

Arghashi & Yuksel, 2022;

X. Jia et al., 2022). In this sense, virtual interactivity creates a space where people can develop connections, exchange interests, and share information, facilitating business relationships between sellers, buyers, and intermediaries (

Arghashi & Yuksel, 2022;

Gaines, 2019). This is where word of mouth (WOM) plays a crucial role for companies that want to achieve greater success in their marketing goals compared to those that do not use this strategy. This is because WOM is a more effective form of advertising that facilitates a greater number of consumers to engage with a brand (

Zasuwa, 2024). For this same reason, WOM could be considered an ally of digitalized brands (

Aljumah et al., 2023;

Rubalcava de León et al., 2019), as any social media user can talk or comment about their favorite brands, sharing positive, neutral, or negative opinions, which will influence a potential customer’s choices (

Damayanti, 2023;

Rubalcava de León et al., 2019).

The relevance of this study lies in the fact that, thanks to the creation of new technologies and algorithms, almost any type of information can now be accessed almost immediately. With the expansion of technology in the business world, the way we manage businesses has evolved over the last ten years (

X. Jia et al., 2022). A total of 97.6% of the world’s population has access to a smartphone, representing a 1.8% increase compared to 2023, according to the “Digital 2024 Global Overview Report” (

DataReportal, 2024). These devices have a significant impact on purchasing habits and interaction due to their widespread use among users. In this sense, as in other business environments, the banking sector faces the challenge of retaining its customers and attracting new ones (

Junaid et al., 2019;

Panduro-Ramirez et al., 2024), and in response to this, the specialists in question have considered that virtual interactivity is essential to grow and retain loyal customers, in addition to reducing desertion (

Borishade et al., 2022).

On the one hand, the banking sector is implementing different strategies and methods that emphasize brand love as an essential component (

Amegbe et al., 2021;

Chow & Ho, 2025;

Panduro-Ramirez et al., 2024), as this approach is the most widely used to understand the emotional bond, respect, and loyalty toward a brand. On the other hand, recent studies have evaluated the link between this sector from the perspective of relationship marketing theory (

K. Hidayat & Idrus, 2023;

Nguyen & Hoang, 2024;

Zegullaj et al., 2023), WOM (

Dangaiso et al., 2024;

Zasuwa, 2024), and the integrative role of the customer loyalty theory in mobile banking (

Arora & Banerji, 2024;

Muflih et al., 2024;

Nguyen & Hoang, 2024). In this context, establishing banking brands that connect emotionally has become a strategic necessity to create lasting and differentiating relationships in a highly competitive and digital market.

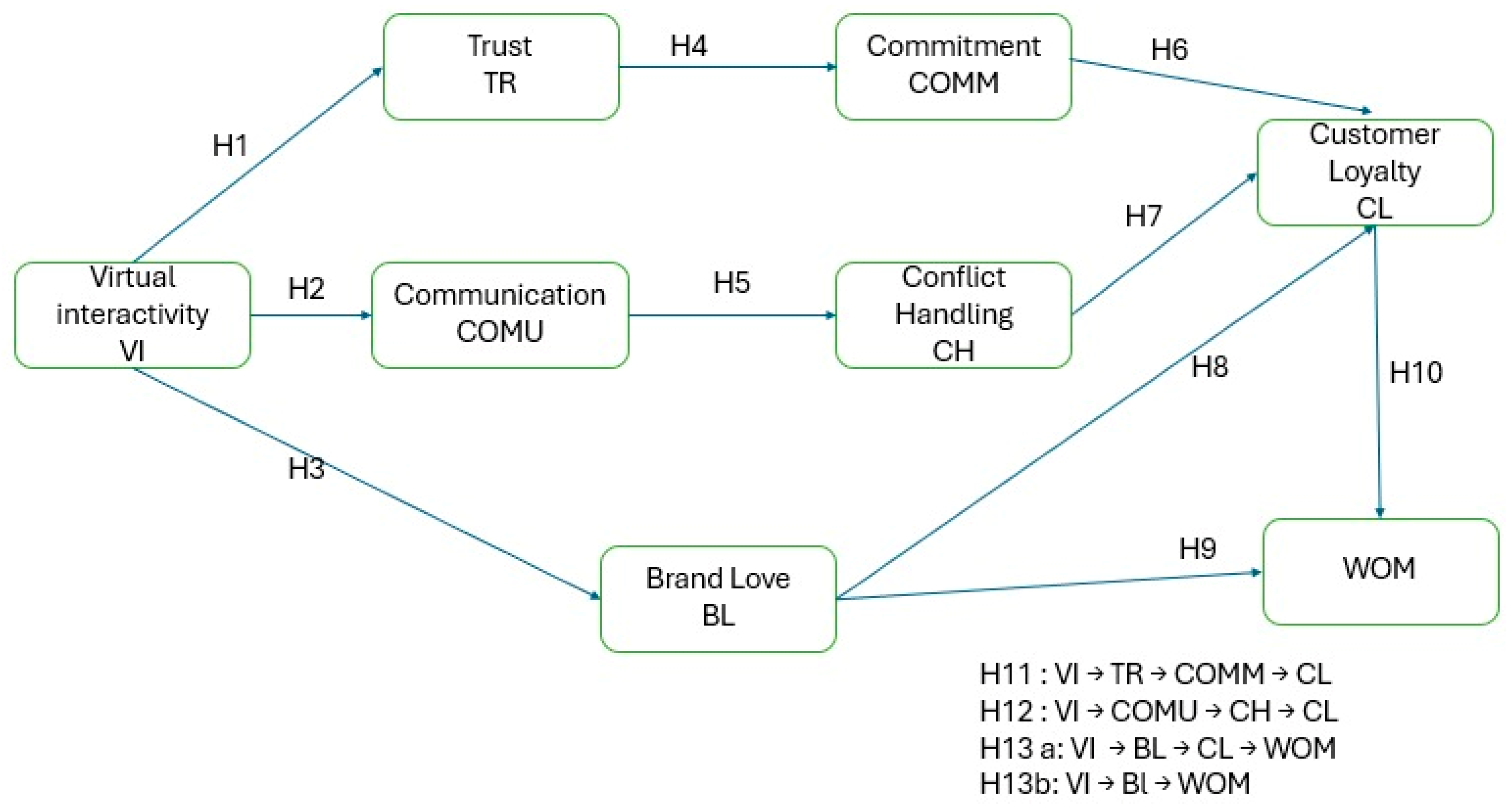

In this regard, after reviewing the aforementioned background, interest arose in delving deeper into virtual interactivity, relationship marketing, WOM, customer loyalty, and brand love as an integrative model that could add value to academics and professionals in the banking sector. Bibliometric indicators reveal the ten countries that most disseminate their scientific results, including Indonesia, India, Malaysia, Iran, the United Kingdom, China, the United States, Australia, Vietnam, and Spain; all of them are analyzed for virtual interactivity. These countries have applied their research to diverse areas of knowledge, sectors, and populations, including business, management and accounting, economics, econometrics, finance, and the social sciences. Despite this, no empirical research has been found that examines how the suggested model behaves in banking environments, which reveals a clear lack of scientific production for this cultural context. This lack of scientific evidence prevents a proper understanding of the fundamental factors of virtual interactivity in different sociocultural contexts. Briefly, with the intention of addressing this theoretical and empirical gap, this study aims to analyze and validate the model in a Peruvian context, thereby providing valuable information that will enrich both international knowledge and the development of more effective strategies for digital environments in developing countries. Consequently, the objective of this research was to analyze the effect of virtual interactivity on customer loyalty and WOM through multiple sequential mediation paths, considering the elements of relationship marketing and examining the cognitive (trust–commitment), communicational (communication–conflict management), and experiential (brand love–WOM) mechanisms that operate in digital consumer–brand interactions.

4. Results

As shown in

Table 2, the constructs evaluated in the study meet the acceptable criteria of reliability (α and CR > 0.70) and convergent validity (AVE > 0.50) (

Sarstedt et al., 2021). In this sense, brand love (BL) obtained a Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.908, CR of 0.916, and AVE of 0.845, with factor loadings between 0.902 and 0.950. Conflict handling (CH) registered an α of 0.842, CR of 0.846, and AVE of 0.760, with loadings between 0.831 and 0.900. Customer loyalty (CL) had an α and CR of 0.791, with an AVE of 0.827 and factor loadings between 0.908 and 0.911. Commitment (COMM) recorded an α and CR of 0.908 and an AVE of 0.783, with factor loadings ranging from 0.870 to 0.902. Communication (COMU) obtained an α of 0.894, CR of 0.970, and AVE of 0.759, with factor loadings between 0.857 and 0.889. Likewise, trust (TR) presented an α of 0.940, CR of 0.909, and AVE of 0.679, with factor loadings between 0.702 and 0.873. Virtual interactivity (VI) registered an α of 0.893, CR of 0.895, and AVE of 0.824, with factor loadings between 0.898 and 0.919. Finally, word of mouth (WOM) obtained an α of 0.892, CR of 0.895, and AVE of 0.822, with factor loadings in the range of 0.882 to 0.929.

To evaluate the discriminant validity of the model, this study applied the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio criterion, which measures the relationship between latent constructs by comparing the correlation between their indicators (

Henseler et al., 2015). According to this criterion, discriminant validity is considered to be achieved if HTMT < 0.90 (flexible criterion) or HTMT < 0.85 (stricter criterion, used in models with high conceptual similarity between constructs). In the present study, all the relationships between constructs meet this requirement, since the HTMT values ranged from 0.529 to 0.817, indicating that they were below the permissible threshold.

Table 3 presents the details of these results.

To address potential common method bias (CMB), we applied

Kock’s (

2015) complete collinearity test. The results show that the variance inflation factors (VIFs) ranged from 1.000 to 1.918, all substantially below the critical threshold of 3.3, confirming that the model is free from significant CMB contamination. This can be seen in

Table 4.

The MICOM invariance test confirmed that the comparisons were methodologically valid (all

p values > 0.05), indicating that men and women interpreted the constructs equally (See

Table 5).

The multi-group analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between men and women in the main path coefficients (all

p > 0.05), suggesting that the effects of virtual interactivity operate similarly regardless of the consumer’s sex (see

Table 6).

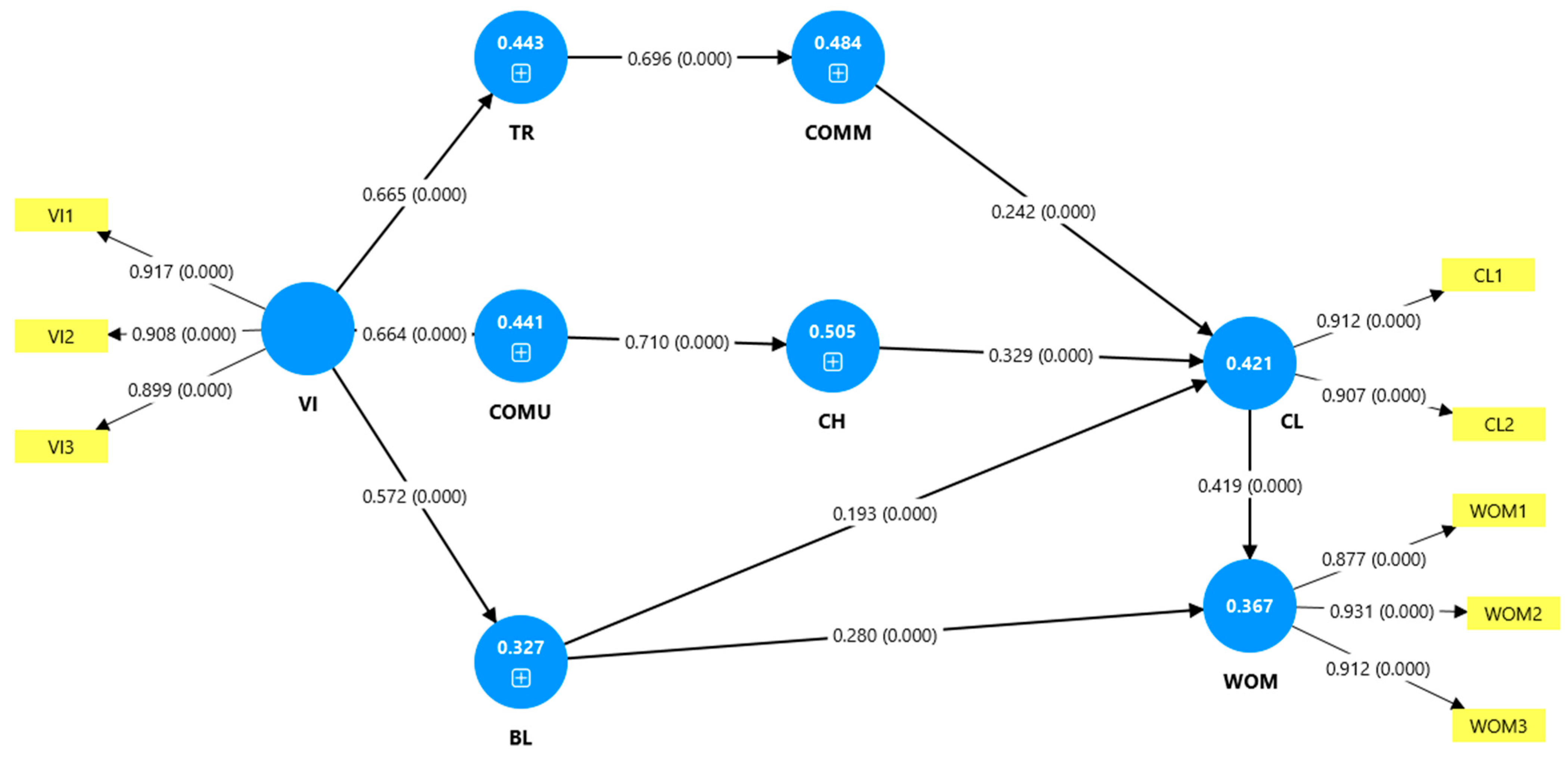

Figure 2 presents the final structural model developed in SmartPLS, which illustrates the causal relationships between virtual interactivity and its effects on consumer relational variables through three distinct mediation paths. The model employs a standard graphical representation, where latent constructs are shown as blue circles with their respective R

2 values, observable variables appear as yellow rectangles, and structural relationships are represented by directional arrows with their standardized path coefficients and significance levels.

All constructs employ reflective measurement models, with indicators showing factor loadings greater than 0.70, meeting individual item reliability criteria. The dependent constructs (CL and WOM) have two indicators each, while IV includes three indicators, and the mediating constructs vary between two and four indicators. Regarding the pathways, it can be observed that the cognitive pathway (VI → TR → COMM → CL) is displayed at the top of the model, starting from VI to TR (β = 0.665, p < 0.001), continuing to COMM (β = 0.696, p < 0.001), and ending at CL (β = 0.242, p < 0.001). The graphical representation shows a linear progression that reflects the theoretical logic of the sequential development of trust and commitment. Regarding the communication path (VI → COMU → CH → CL), located in the central section of the model, it shows a progression from VI to COMU (β = 0.664, p < 0.001), followed by the strongest relationship in the model toward CH (β = 0.710, p < 0.001), and culminating in CL (β = 0.329, p < 0.001). The central position emphasizes its role as a primary mechanism for generating loyalty.

Finally, the experiential path (VI → BL → WOM/CL), positioned at the bottom, presents a bifurcated structure where VI influences BL (β = 0.572, p < 0.001), which subsequently affects both WOM (β = 0.280, p < 0.001) and CL (β = 0.193, p < 0.001). This visual configuration reflects the dual nature of brand love as a generator of both positive word of mouth and loyalty.

Table 7 presents the Path Hypothesis Testing. The results confirm the empirical validity of the cognitive path as a fundamental mechanism for generating customer loyalty through the sequential processes of trust and commitment. Virtual interactivity demonstrated a significant and robust direct effect on brand trust (H1: β = 0.665, t = 15.721,

p < 0.001), followed by an equally strong effect of trust on consumer commitment (H4: β = 0.696, t = 20.642,

p < 0.001), representing the strongest relationship between mediating constructs in the entire model. However, the conversion of psychological commitment into behavioral loyalty exhibited a more moderate effect (H6: β = 0.242, t = 4.463,

p < 0.001), suggesting that while virtual interactivity is highly effective in generating relational cognitive processes, the final translation into loyalty behaviors requires complementary factors. The sequential mediation hypothesis (H11: VI → TR → COMM → CL) was supported with a significant indirect effect of 0.112 (t = 3.876,

p < 0.001), empirically validating the extension of the Commitment–Trust Model (

Morgan & Hunt, 1994) to virtual interactivity contexts and confirming that traditional relational processes maintain their relevance in contemporary digital environments.

The communication path emerged as the model’s most effective mechanism for generating customer loyalty, highlighting the critical importance of communication management in interactive digital environments. Virtual interactivity exerted a positive and significant effect on perceived communication quality (H2: β = 0.664, t = 15.969,

p < 0.001), establishing a solid foundation for effective two-way exchanges. Crucially, perceived communication predicted conflict management ability with the highest t statistic in the entire model (H5: β = 0.710, t = 19.598,

p < 0.001), evidencing that interactive platforms not only facilitate communication, but also enable proactive and competent problem-solving. Conflict management capability subsequently generated a moderately strong effect on customer loyalty (H7: β = 0.329, t = 5.241,

p < 0.001), outperforming the effect of commitment on the cognitive route and confirming that consumers particularly value organizational competence to effectively manage problems through digital media. The sequential mediation hypothesis (H12: VI → COMU → CH → CL) was supported by the strongest indirect effect in the model (β = 0.155, t = 4.229,

p < 0.001), extending the Computer-Mediated Communication Theory (

Walther, 1996) and establishing communication management as the most potent mechanism for converting virtual interactivity into customer behavioral loyalty.

The experiential path revealed a unique dual-operation pattern that differentiates between the generation of emotional advocacy and traditional loyalty behaviors, challenging conventional theoretical expectations about brand love. Virtual interactivity significantly influenced the development of brand love (H3: β = 0.572, t = 12.793,

p < 0.001), confirming that interactive digital experiences facilitate the formation of intense emotional bonds. However, brand love displayed a distinct and counterintuitive pattern of effects: it generated a stronger impact on positive word of mouth (H9: β = 0.280, t = 4.761,

p < 0.001) than on behavioral loyalty (H8: β = 0.193, t = 4.009,

p < 0.001), suggesting that emotional bonds motivate spontaneous advocacy more effectively than repeat purchase behaviors in digital contexts. The corresponding mediation hypotheses confirmed this functional differentiation: the indirect effect towards WOM (H13b: VI → BL → WOM = 0.160, t = 4.050,

p < 0.001) outweighed the effect towards loyalty, while the multiple sequential mediation path (H13a: VI → BL → CL → WOM = 0.046, t = 3.081,

p = 0.002) reached statistical significance with a small effect size. Paradoxically, customer loyalty more strongly predicted recommendations (H10: β = 0.419, t = 7.675,

p < 0.001) than direct emotional love, suggesting that in virtual environments, consistent behavioral satisfaction constitutes a more robust predictor of advocacy than purely emotional ties, thus recontextualizing the Brand Love Theory (

Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006) for digital environments where functionality may predominate over emotionality in generating authentic recommendations.

To provide a comprehensive assessment of the model, we analyzed multiple quality indicators including the explanatory power (R

2), effect sizes (f

2), and predictive relevance (Q

2). The results reveal a robust model with an explanatory power ranging from moderate to substantial. In terms of explanatory power, the mediating constructs showed substantial R

2s, indicating that their antecedents explain a considerable portion of their variance: CH (50.5%), COMM (48.4%), TR (44.2%), and COMU (44.1%). The dependent constructs exhibited moderate to substantial explanatory power: CL (42.1%) and WOM (36.7%). Notably, BL showed the lowest R

2 (32.7%), suggesting the existence of additional factors influencing the development of brand love in digital contexts. Effect size analysis (f

2) revealed that the most influential relationships in the model included COMU → CH (f

2 = 1.019) and TR → COMM (f

2 = 0.939), both classified as very large effects according to

Cohen’s (

1988) criteria. The effects of VI on the primary mediators were also large, confirming the substantial importance of virtual interactivity: VI → TR (f

2 = 0.794), VI → COMU (f

2 = 0.788), and VI → BL (f

2 = 0.485). Predictive relevance assessment using Q

2 showed that all constructs exceeded the relevance threshold (Q

2 > 0), with values ranging from 0.222 (BL) to 0.439 (TR and COMU). This confirms that the model has satisfactory predictive capacity for all endogenous constructs. This can be seen in

Table 8.

5. Discussion

Relationship marketing has gained a prominent place in the business world, not only because it marks a transition from a transactional approach to one more focused on building ongoing relationships between stakeholders, but also because it promotes an organizational awareness that drives value creation from different spheres: academia, business management, and marketing leaders (

Gómez-Bayona et al., 2024). This study fits precisely into this scenario, demonstrating how virtual interactivity, far from being a simple communication channel, acts as a strategic driver that transforms customer–brand relationships. An analysis of the behavior of 417 individuals confirms that virtual interactivity generates a tangible impact on key variables such as trust, communication, conflict management, and brand love. These variables highlight the fundamental aspects of relationship marketing in digital environments, where interactive experiences strengthen brand identity and stimulate loyal consumer behavior (

Cachero-Martínez & Vázquez-Casielles, 2021;

De Ruyter & Wetzels, 2000).

Particularly in sectors such as financial services, the implementation of relational digital strategies contributes to developing two-way and personalized communication, which is essential for interpreting consumer tastes, needs, and expectations (

Gaines, 2019). This capacity for dynamic interaction is precisely what builds the bridge between the brand and its audience, consolidating its positioning and generating meaningful emotional bonds. The empirical results of this work reaffirm the importance of these interactions on three levels.

In the cognitive path, the model demonstrates how virtual interactivity generates trust (β = 0.665) and how that trust transforms into commitment (β = 0.696). Following the logic of the

Morgan and Hunt (

1994) model, although the transition from commitment to customer loyalty shows a lower intensity (β = 0.242), it is still relevant, although it requires strengthening additional factors such as service experience or personalization to fully close this relational cycle. Even more compelling is the role of the communication route, where digital interactivity positively influences communication quality (β = 0.664), which, in turn, enhances conflict management (β = 0.710). These results not only confirm

Walther’s (

1996) predictions about the effectiveness of computer-mediated communication, but also position this route as the most influential in the model in terms of loyalty conversion (total indirect effect = 0.155). Effective conflict management emerges as a key differential, even more so in service contexts where the perception of rapid and effective resolution makes a decisive difference in the customer experience (

Grönroos, 2004;

Smith et al., 1999).

Regarding the experiential route, the analysis reveals a more emotional and dual dynamic. On the one hand, digital interactivity increases cognitive processing and generates emotional bonds (brand love) with the brand (β = 0.481), following the proposal by

Carroll and Ahuvia (

2006). However, it is observed that brand love has a greater influence on positive word of mouth (β = 0.280) than on direct loyalty (β = 0.193). This is particularly interesting: in digital environments, emotional expression tends to be channeled more into spontaneous recommendations than repeat purchases. In this sense, loyalty based on specific behaviors seems to have a greater weight on WOM (β = 0.419), which suggests that consistent satisfaction has a greater predictive power than pure emotions.

This finding implies an adjustment to the classic theories of emotional marketing. Rather than conceiving brand love as the core of loyalty, this study proposes that brand love acts as a trigger for advocacy, while loyalty is built on rational and trustworthy experiences. This distinction is key for marketers, who must recognize that in the digital environment, emotional bonds are relevant but must be accompanied by a coherent functional value proposition.

Taken together, the results highlight the importance of incorporating virtual interactivity as a structural component of relationship marketing strategies (

Cachero-Martínez & Vázquez-Casielles, 2021;

Nambisan & Baron, 2007). Organizations that understand and capitalize on these mechanisms will be able to improve the quality of their customer relationships, foster lasting bonds, and build more human and relatable brands. Furthermore, the evidence from this study is consistent with the scientific reports of

Yan et al. (

2024), who highlight how transparent communication and genuine engagement generate greater peace of mind for consumers and, therefore, strengthen the brand’s reputation and positioning. It is necessary to mention that this type of model also shows that digital tools not only serve to attract customers, but, well managed, they allow for continuous support, anticipating conflicts, personalizing responses, and maintaining an active dialogue with audiences. Thus, the contribution of relationship marketing is not only limited to the business field, but, as

Gómez-Bayona et al. (

2024) point out, it also becomes an opportunity to educate communities on the importance of trust, satisfaction, and loyalty as shared values that contribute to the development of a more conscious organizational culture. This study not only validates the theoretical hypotheses raised, but also confirms the validity of traditional models (

Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006;

Morgan & Hunt, 1994) by reinterpreting them in a digital key, where virtual interactivity is shown as a multifaceted relational medium, capable of activating cognitive, communicational, and affective processes, and translating them into real behaviors that benefit both brands and consumers.

6. Conclusions

Virtual interactivity in marketing has evolved significantly in recent decades, becoming an essential tool for effectively connecting with consumers in digital environments. Through interactive digital platforms, brands can generate a two-way dialogue with their customers, allowing them to obtain instant feedback and adapt their strategies quickly and effectively. This not only improves brand image but also contributes to strengthening brand image and fostering long-term loyalty. In this context, this research aimed to analyze the effect of virtual interactivity on customer loyalty and WOM through multiple sequential mediation pathways, considering the elements of relationship marketing and examining the cognitive (trust–commitment), communication (communication–conflict management), and experiential (brand love–WOM) mechanisms at work in digital interactions between consumers and brands.

The study’s hypotheses confirmed the proposed model, which considered trajectory theory: the cognitive trajectory (trust–commitment), which extends the Commitment–Trust Model to the context of virtual interactivity; the communicational trajectory (communication–resolution), which integrates Computer-Mediated Communication Theory with customer relationship management; and the experiential trajectory (cognitive–affective), which combines cognitive processing with affective responses, and extends the Brand Love Theory to interactive digital environments. In this sense, this research provides valid results related to the digital world in banking contexts and considers applicable implications for business and industry management, which are detailed in the subsequent sections.

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

From a theoretical perspective, this study enriches the literature by integrating path theory (cognitive, communicational, and experiential) with an empirical analysis of virtual interactivity, explaining how people process information, generate connections, and make decisions in complex digital contexts such as the banking sector. The cognitive path extends the Commitment–Trust Model, demonstrating that trust and commitment can be activated through interactive technologies. The communicational path, based on Computer-Mediated Communication Theory, shows how digital platforms facilitate proactive conflict resolution and improve relationship management. The experiential path articulates cognitive processing with affective responses (brand love), extending the Brand Love Theory to virtual environments. This approach not only allows us to understand how virtuality transforms the interaction between banks and customers in aspects such as functionality, experience, security, and loyalty, but also offers a solid framework for the design of evidence-based models and strategies, useful both for academic purposes and for innovation and competitiveness in the digital industry.

As a practical implication, this study suggests that organizations operating in digital environments, such as the banking sector, should adopt a comprehensive approach based on the three pathways. From the cognitive pathway, it is recommended to design interactive experiences that strengthen customer trust and engagement. From the communication pathway, it is key to implement tools that facilitate effective two-way communication and early conflict resolution. Finally, the experiential pathway encourages the creation of interactions that not only increase brand recognition but also generate lasting emotional bonds, promoting customer loyalty and advocacy spontaneously.

It is important to recognize that, in the digital age, relationships between companies and customers have evolved toward closer and more meaningful interactions. Virtual interactivity not only transforms the way brands communicate with their audiences but also strengthens bonds of trust and loyalty. When a company manages to genuinely connect with its customers, they feel valued and heard, which reduces the likelihood of them migrating to competitors. Furthermore, the ability to personalize the customer experience in real time allows for more dynamic and effective relationship marketing strategies. Each interaction becomes an opportunity to better understand customer needs and expectations, adjusting the offer of products or services more precisely.

Beyond commercial strategies, virtual interactivity contributes to building a solid reputation and a brand identity with which customers can emotionally identify. This connection goes beyond a simple commercial transaction: when people trust and value a brand, they not only remain loyal to it but also recommend it, generating a positive impact on its growth and sustainability. In a constantly changing digital environment, those companies that manage to humanize their communication and adapt to their audience’s expectations not only stand out in competitive markets, but also ensure their long-term relevance. From a theoretical perspective, it has been proven that effective digital communication fosters brand love and positive word of mouth, consolidating its impact on customer loyalty and business development.

On the other hand, promoting brand affection through prompt, reliable, honest, and accurate information will contribute to developing a stronger and more lasting brand. Customers tend to feel affection for a brand when banks address complaints and other issues effectively, aiming to anticipate potential sources of conflict before they arise. This will allow the brand to build customer loyalty, strengthening their bond in situations of loss and fraud, which are, above all, key aspects in this sector. Finally, it is essential to foster clear communication and address conflicts diplomatically to reduce unnecessary losses and problems for customers. An important aspect is WOM, as it can influence other customers. Therefore, it is essential to create strategies to improve this element in the banking sector, as this encourages customers to choose one brand over another.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

This research acknowledges a significant contribution to the academic community and the banking sector; however, some limitations have been identified that would be valuable to consider for future studies. Initially, the respondents were residents of Lima, the capital of Peru, famous for being a populous and culturally diverse city, where its inhabitants come from diverse areas of the country. However, future research is likely to consider other significant regions of the country, including cities located by the Peruvian coast, mountains, and jungle, in order to achieve more homogeneous participation and perception. Furthermore, the descriptive data indicated that 63.3% of respondents were between 25 and 34 years old. This research focuses on a fairly young segment of the Peruvian banking population, raising potential doubts regarding their opinions of the sector, preventing the results from being generalized to other age groups. Further research could examine psychosocial, sociodemographic, and specific environmental factors to better understand their behavior.