Abstract

This research investigates the integration of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into the business practices of the Portuguese energy giant EDP Group. We analyse the company’s annual reports, sustainability reports, and public statements to explore the motivations, challenges, and key organisational dimensions involved in this process. Our findings reveal that EDP Group’s strong commitment to sustainability, external pressures, and stakeholder expectations have driven the integration of the SDGs into its strategic and operational plans. The company’s cultural emphasis on environmental and social responsibility and formal management control systems has facilitated this integration. However, challenges such as the lack of standardised metrics to measure social and environmental impacts and the evolving regulatory landscape hinder progress. This study contributes to understanding how large corporations can effectively integrate the SDGs into their business models, providing valuable insights for practitioners and policymakers.

1. Introduction

In a world where sustainability is essential for the survival of humanity, it is imperative to reformulate current paradigms and direct them towards sustainable development. Sustainability is gradually becoming a recognised and incorporated practice within businesses, with companies increasingly aware of their role in this process. Financial information seems to be insufficient to measure the company’s ability to create value. This trend highlights that integrating environmental and social issues into the business model can create opportunities and offer benefits for the organisation (Rodriguez et al., 2002; Global Reporting Initiative, United Nations Global Compact & World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2015), allowing them to meet the growing demands of consumers and investors (PwC, 2015, 2019).

Through the definition of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the SDG Compass, companies, despite sharing responsibilities, play a crucial role in achieving the SDGs (Global Reporting Initiative, United Nations Global Compact & World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2015). However, despite this progress and the business sector’s growing awareness of its role and responsibility (through sustainability discourse and external reports), the integration of the SDGs is still a challenge. Although companies show interest in this process, they often do not know how to act (PwC, 2015, 2019).

In this context, management control helps companies to include sustainability in the business model, become more sustainable, and promote the SDGs effectively. Several authors (Gond et al., 2012; Lueg & Radlach, 2016; Crutzen et al., 2017; Fleming et al., 2017; Van der Kolk, 2019; Hasu et al., 2025a) argue that, through different management control systems (MCSs), it is possible to assess the sustainable performance of organisations by analysing and guiding economic, environmental, and social data in an integrated manner. This provides access to complete, accurate, and relevant information that guides employee behaviour and supports strategic planning and decision-making (Anthony, 1988; Flamholtz, 1996; Drury, 2012; Jordan et al., 2015), while addressing sustainability issues on different levels. The governance literature highlights the role of board-level structures, such as sustainability or CSR committees, in enhancing sustainability disclosures. Gürbüz and Gürbüz (2025), focusing on the transportation sector, found that the presence of a sustainability committee significantly strengthens the link between environmental performance and strategic governance structures. This finding underscores the relevance of internal governance mechanisms in achieving concrete environmental sustainability outcomes.

There is also a gap, in the theoretical literature and empirical studies, on management control tools applied to sustainable development (Florêncio et al., 2023). The analysis of how management control can contribute to integrating sustainable development is still under-explored (Gond et al., 2012; Lueg & Radlach, 2016; Crutzen et al., 2017). It is not yet known to what extent companies are implementing the integration of sustainable development and the SDGs, nor how management control has supported this process. While sustainability and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have received increasing attention in the academic literature, a specific gap remains regarding the analysis of how MCSs are operationalised to support the integration of SDGs into corporate strategy (Quesado et al., 2025). Most existing studies focus either on the theoretical frameworks of sustainability control (e.g., balanced scorecard adaptations, ESG reporting, or SDG Compass principles) or on environmental aspects alone, often neglecting the organisational and managerial processes that facilitate integration. In particular, there is limited empirical research on how companies translate SDG-related ambitions into internal control mechanisms, especially in a holistic manner that includes economic, environmental, and social dimensions.

This is understandable because the integration of the SDGs into management practices, until a few years ago at least, was limited to a few companies, due to the novelty of the topic and the limited knowledge of the business sector in this process (PwC, 2015, 2019). In this context, basing this study on a benchmark company such as EDP Group–Portugal Energy [Energias de Portugal], which has incorporated the SDGs since their creation by the UN in 2015, makes this study relevant for addressing the aforementioned gap with a rare empirical case from Southern Europe.

It is crucial to investigate how a pioneering company in the adoption of sustainable development and the SDGs is facing these challenges. In this way, this study seeks to deepen the analysis of the management control practices applied to integrate the SDGs and understand the motivations and challenges involved in this procedure. It contributes to the debate on how management control can help incorporate the SDGs into the corporate environment and also extends Herath’s (2006) management control framework to the context of SDG integration. This qualitative study relies on documental and discourse analysis.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Integrating the SDGs into Business Strategy

In September 2015, a new agenda was launched, initially called “Transforming Our World: 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” and aimed at the new decade that followed, 2020–2030. Considered by the United Nations to be the “Decade of Action”, a developed and ambitious agenda was born that intertwines the three strands of sustainable development (social, economic, and environmental) and aims to promote peace, justice, and effective institutions, with an essential focus on eradicating poverty (United Nations, 2015).

It presents 17 SDGs capable of turning this vision into reality and to act in the main critical areas of the planet, committing to “leave no one behind” (United Nations, 2015, p. 3) through a path structured around five Ps: People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnerships. In these pillars, the United Nations is determined to end poverty and hunger all over the world and is committed to protecting the planet from degradation, considering sustainable production and consumption necessary to support future generations. Therefore, combining economic and social growth with nature is a key factor for all human beings enjoying a prosperous and healthy life. However, none of this is possible in a world where there is no peace, so promoting peace and “peaceful, just and inclusive societies, free from fear and violence” (United Nations, 2015, p. 2) is crucial to sustainable development, as is enabling a global partnership, encompassing governments, companies, and individuals, in a stronger sense of universal solidarity to enable the realisation and implementation of this new agenda (United Nations, 2015).

The goals addressed in this agenda are a continuation of the Millennium Development Goals, broadening the scope and being more incisive regarding the primary goals that will always be the mission of all signatory countries, which are to eradicate hunger and poverty and promote health, in addition to the environmental issues that are the order of the day (Matos, 2021).

When examining MDGs (Millennium Development Goals) and SDGs, it is possible to identify some distinctions that reflect divergent approaches to sensitive issues. However, some aspects have remained consistent, highlighting the influence of the MDGs on the SDGs. There is a clear determination to complete the work started by the previous goals, which is reflected in the updating of the goals. Previously, the focus was on halving issues such as poverty, hunger, and child mortality. These goals are presented to eliminate them and are referred to as “zero goals”.

As a result of Rio+20, the open working group attached great importance to the environmental issue, which contrasts sharply with the MDGs, which were more centred on human development issues. These goals are all-encompassing, as they are not just limited to poverty reduction but also address issues such as peace, stability, human rights, and effective governance. This represents a break from the previous paradigm, offering a broader perspective for achieving sustainable development.

The SDGs represent a gradual advance. Despite criticism, the development of the 17 SDGs was influenced in part by the gaps identified in the MDGs. Table 1 highlights some of the practical divergences between the fundamental principles of the MDGs and the SDGs.

Table 1.

Distinction between MDGs and SDGs.

Based on the SDGs (see Figure 1), governments and society have taken a leading role in implementing changes aimed at sustainable development by the year 2030, recognising that the SDGs act as a guide that sets out the main objectives to be achieved and the points where intervention is needed.

Figure 1.

The Sustainable Development Goals. Source: United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development, consulted at https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 23 October 2024).

The 2030 Agenda assigns a central role to the business sector in advancing sustainable development. The contribution of companies to the recognition of the SDGs is essential, as they are drivers of economic growth, entrepreneurship, and innovation (World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2016). This relation emphasises that action by governments alone is not enough to achieve the proposed goals. Furthermore, it demonstrates that governments, civil society, and the public and private sectors evenly share responsibility in this process of advancement.

The implementation of the SDGs results in several benefits for each country. Integrating education, health, and sanitation actions in areas aligned with the SDGs can result in a cohesive approach that is further economically viable and capable of impacting individuals in a more comprehensive and coordinated manner (Sachs, 2004), making interventions more efficient and effective (Langlois et al., 2012). In addition, environmental management practices can bring significant economic benefits, such as reducing production costs by adopting measures such as recycling, reusing, and reducing waste, within a circular production system, as pointed out by Ghisellini et al. (2018).

However, when reviewing the available literature, it is common to find criticisms of the topic. The number of objectives is an aspect often highlighted by authors as a point of concern, considering it to be an excessive number. Vaughan (2015) questions the increase in the number of objectives, arguing that there is an overload of targets, indicators, and country participation in the process, which could jeopardise their effectiveness and implementation. Doyle (2016) raises a possible consequence of this extension of goals, namely that states may take a selective approach to the goals, leading to the creation of projects that aim to achieve only a few specific goals, neglecting other equally important ones, which would jeopardise the collective purpose of the goals, as recommended by the 2030 Agenda.

Holistic strategies are essential to effectively tackle global challenges (Cruz et al., 2025), and one key component of such strategies is the active involvement of companies in implementing the SDGs, which can strengthen the business environment by minimising risks and creating new opportunities. However, it is important to emphasise that the participation of companies in designing the SDGs can also bring conflicts of interest between their corporate interests and the need for sustainable economic growth (Koehler, 2015; Scheyvens et al., 2016).

Integrating the SDGs into corporate strategies can create opportunities, foster innovation, open new markets, and boost growth (PwC, 2015). This integration can reduce legal and regulatory risks, improve the company’s image, increase trust in the brand, and strengthen relationships with stakeholders, creating value and competitive advantages (Verboven & Vanherck, 2016; Scheyvens et al., 2016). Verboven and Vanherck (2016) highlight the main drivers of success in promoting the SDGs, such as the integration of these goals into business strategies, the implementation of management tools, integration into the research and development of new products, and financial support.

In this context and given the importance of the business sector in sustainable development, the SDG Compass was created, with an emphasis on the impact of corporate practices. The SDG Compass is an initiative developed in collaboration with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the United Nations Global Compact, and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). The aim of the SDG Compass, according to Verboven and Vanherck (2016, p. 167), is

to facilitate the effective realisation of the SDGs, in a strategic manner, and the improvement of sustainability policies in the company. The aim of the tool is twofold: (1) to explain how the SDGs influence business activities and (2) to offer guidance on implementing and managing the SDGs.

The SDG Compass provides practical guidance on how companies can incorporate the SDGs into their operations, strategies, and value chains. It promotes a framework for companies to understand how they can contribute to achieving the SDGs and integrate these goals into their business models in a meaningful and effective way. In essence, it is based on a tool to help organisations, as it clarifies the process of building and defining the SDGs, providing a deeper understanding of the goals and targets set by the United Nations; it highlights how these can influence businesses and help companies understand and map potential impacts, both positive and negative; it guides companies on how they can align their strategies with the SDGs, offering practical guidelines for integrating them; it indicates the best way to meet economic, social, and environmental demands; and it facilitates the management of companies’ contributions to the SDGs, allowing them to identify opportunities for contribution and to measure the impact of their operations and results (Global Reporting Initiative, United Nations Global Compact & World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2015).

In short, the SDG Compass serves as a tool to help companies understand, plan, and act on the SDGs, thereby promoting sustainable development and corporate responsibility. Companies must recognise their responsibility to promote sustainable development, in collaboration with civil society and the state, and take corporate social responsibility seriously, not just as a way of minimising the negative impacts associated with their business activities.

Reflecting the importance, as well as the complexity, of sustainability in the broadest sense to companies’ management, other influential frameworks have emerged to guide corporate sustainability disclosures and accountability, proposing a more standardised, comparable, and decision-useful reporting. The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), established under the IFRS Foundation, seeks to develop a comprehensive global baseline for sustainability-related financial disclosures, helping investors understand how sustainability factors affect enterprise value (de Villiers et al., 2024). Similarly, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), introduced by the European Union, requires large companies to report on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues using detailed and standardised metrics aligned with the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRSs) (Operato et al., 2025). Complementing these, the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), initiated by the Financial Stability Board, provides a widely adopted framework for disclosing climate-related financial risks and opportunities, emphasizing governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics (Dilling et al., 2024).

These frameworks align closely with the ambitions of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which calls for transformative action during the Decade of Action (2020–2030), with businesses playing a central role in delivering the SDGs. The Global Sustainable Development Reports (GSDRs) of 2019 and 2023 further reinforce the urgency of systemic, integrated approaches to sustainability, highlighting risks of fragmented or symbolic efforts.

2.2. The Challenge of Integrating the SDGs into Management Control

MCSs represent an interrelated set of controls within an organisation. They represent one of the fundamental management tools, enabling the planning, budgeting, analysis, measurement, and evaluation of financial and accounting information. In addition, they serve as a reliable and valuable source on which to base managers’ decisions, achieve the defined strategic objectives, and gain a competitive advantage (Duréndez et al., 2016).

It should be noted that MCSs are essential for the development of organisations, as they seek to influence the behaviour of their constituents, both managers and employees, to ensure that the execution of the strategy is in line with the plan. This is achieved by synchronising individual goals and decision-making processes with the overall goals and objectives of the organisation (Chenhall, 2003; Gond et al., 2012).

Jordan et al. (2015) describe management control as a set of mechanisms designed to encourage distant employees to achieve the company’s strategic goals, emphasising quick action and decision-making, as well as promoting the delegation of authority and responsibility. In this context, the authors establish eight fundamental principles of management control (Table 2).

Table 2.

The eight principles of management control.

Hewege (2012) points out that one of the main tasks of management control is to align the interests of individual employees with those of the organisation. He considers that management control within a company encompasses human and technical systems and that organisational effectiveness can only be achieved by effectively integrating these systems. However, it also recognises that management control focused on human behaviour can present complexities, since there are differences in the social, cultural, and political context, as well as variations in the characteristics of the organisations and individuals themselves, leading to different reactions to the same stimuli. To summarise, management control involves the controller, the controlled, and the control mechanism.

Strauß and Zecher (2013) highlight the crucial role of aggregated information as a guide to decision-making and the importance of controlling individual human behaviour within organisations. According to the authors, the configuration of MCSs must be adapted to the specific decision-making needs at different hierarchical levels of the organisation, considering the unique characteristics of each company and the conditions of the external environment in which it operates.

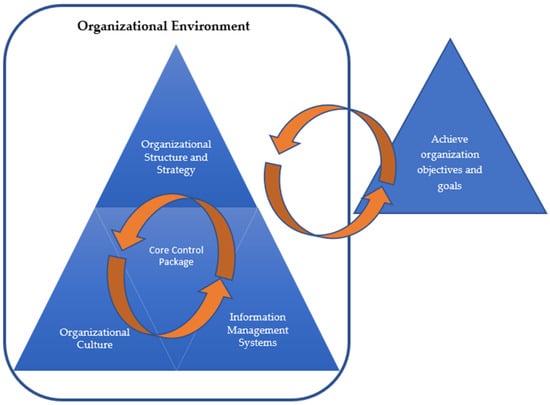

Based on the existing literature to date, Herath (2006) consolidates and presents a structural model of management control (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Structure of management control. Source: Adapted from Herath (2006).

The author initially highlights two main dimensions, the MCS and the achievement of organisational objectives and targets, stressing that these dimensions are interconnected since the MCS is fundamental to achieving the established objectives.

According to Figure 2, the MCS is built on the interaction between the three essential components represented in the inner triangles: organisational structure and strategy, organisational culture, and information management systems. The organisational structure covers the hierarchy, rules, regulations, and internal communication channels. The strategy involves the methods and strategies adopted to achieve specific objectives. Organisational culture is made up of the set of values, beliefs, norms, and behaviours that define the organisation. Finally, information management systems are the mechanisms, both formal and informal, that managers use to control the flow of information within the organisation (Herath, 2006).

The components described interact with each other to form what Herath (2006) calls the “core control package”, i.e., the central set of organisational control mechanisms and practices. This integrated structure of the MCS is influenced by the external environment surrounding the organisation, highlighting the role of MCSs in adapting and responding to the operational context. It is therefore crucial that the elements of the MCS are flexible and capable of enabling management to adopt procedures and measures that are effective and efficient, thus increasing the chances of achieving the proposed organisational objectives. The author emphasises that incompatibility between any of the components of the MCS will result in an ineffective system.

Faced with emerging challenges, Cowton and Dopson (2002) highlight a peculiar trend in the process of change and reorientation of management control, with an increasing focus on researching how management control is implemented in organisations.

Malmi and Brown (2008) argue that management control should be seen as an integrated set of systems, and not just as a single system. Thus, understanding management control offers a more comprehensive perspective that helps to explore the impact of different control systems, as well as seeking to facilitate and improve the implementation of these controls to support objectives, manage activities, and boost organisational performance.

Management control is a constantly evolving field. Over time, with the advancement of knowledge, techniques, and practices, it has been refined and expanded; its role goes beyond just providing information to support decision-making, it plays a fundamental role in guiding the behaviour of the organisation’s members.

Sustainability has become increasingly accepted and adopted by companies but incorporating it into organisational strategies is still a significant challenge for many organisations (Jollands et al., 2015; Traxler et al., 2020). Lueg and Radlach (2016) argue that to achieve success in the process of integrating sustainability, the first step is to provide a clear definition of the concept, as indicated in the first stage of the SDG Compass: understanding the SDGs.

As organisations recognise the benefits of incorporating the social and environmental dimensions, in addition to the economic one, into their business strategies, various management control mechanisms, such as budgeting, balanced scorecard, and product life cycle costing, are being adapted to integrate sustainability into companies. However, even with the increase in the tools available to facilitate the integration of sustainable development in companies, studies by PwC (2015, 2019) show that there is a divergence between the agents who plan to integrate the SDGs and those who do it, understand how to do it, or know which tools to use to do it.

In this context, Fleming et al. (2017) and Silva (2021) agree with the PWC studies (PwC, 2015, 2019), stating that although the SDGs offer a comprehensive vision, there are still many challenges in practice, especially about how they should be implemented, monitored, and evaluated in terms of their development. There is still a lack of key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure organisations’ real contribution to promoting the SDGs, since they are generally only indicated in published reports without any kind of quantification.

Management control is crucial for implementing sustainable practices in organisations (Hasu et al., 2025a), linking them to the SDGs. Lueg and Radlach (2016) point out that MCSs are essential for integrating sustainable development into the economic, social, and environmental dimensions in line with the organisation’s strategies. However, traditional financial and management accounting are considered insufficient to measure environmental and social practices and balance them with economic performance. To achieve sustainability objectives, it is necessary to adapt existing models or create new specific models to promote sustainable strategies and objectives.

Gond et al. (2012) suggest a set of integrated sustainability-orientated controls based on MCSs, emphasising the necessary interrelationship between them. Technical integration, according to the authors, involves incorporating specific sustainability control practices within a broader MCS. That is, it ensures that decision-making is based on a range of comprehensive information, including the organisation’s economic, environmental, and social data. Organisational integration refers to the practices and behaviours of individuals relating to management control and sustainability control. In other words, the integration of sustainable development into management control must be seen as a daily practice, reflected in the actions of the organisation’s members, and not just in the tools implemented. As far as cognitive integration is concerned, sustainability-orientated control systems must be approached from a communication perspective, creating a favourable environment for debates and the exchange of knowledge between those involved. Cognitive integration is essential for the successful incorporation of sustainability into the organisation’s management control (Gond et al., 2012).

Jollands et al. (2015) highlight the influence of informal controls, namely core values, in achieving organisational sustainability. However, they agree with other authors that these values alone are insufficient to achieve the objectives, as a set of controls, i.e., a GIS with several elements, is needed to succeed. Both corporate and personal values, as well as fundamental values, significantly influence the integration of the SDGs in organisations, making this type of informal control one of the important motivators for implementing the SDGs (Fleming et al., 2017).

Organisations seek to incorporate sustainable development for various reasons: pressure from stakeholders, compliance with institutional and legal requirements, improving their corporate image, or gaining a competitive advantage by being recognised as sustainability-minded companies (Arjaliès & Mundy, 2013; Albertini, 2019; Lueg & Radlach, 2016; Pizzi et al., 2021).

External pressures from stakeholders such as governments, NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations), consumers, and investors, among others, are fundamental in the implementation of MCSs geared towards the SDGs. Thus, the influence of these stakeholders is one of the main drivers for integrating the SDGs into organisations’ management control and directly influences decisions regarding proactive organisational strategies for sustainable development (Wijethilake, 2017; Albertini, 2019; Johnstone, 2020; Pizzi et al., 2021; Nishitani et al., 2021).

An important factor is the fact that the environmental aspect tends to be the most included in organisations, as it initially received the most attention in sustainable development and is relatively easier to monitor due to its tangibility. In contrast, the social dimension is addressed less frequently, and few companies have MCSs that cover all aspects of sustainable development (Riccaboni & Leone, 2010; Gond et al., 2012; Lueg & Radlach, 2016).

Rosati and Faria (2019, p. 588) emphasise that corporate reports that encompass the SDGs can help companies “plan, implement, measure and communicate” their actions related to the SDGs. However, Traxler et al. (2020) argue that these reports only reflect part of the reality. Pizzi et al. (2021) point out that many companies use non-financial reports primarily to gain legitimacy and protect their reputation by minimising negative perceptions of their activities. Thus, there is often a discrepancy between what companies say in their reports and what they practice, indicating that simply presenting a report does not guarantee a true commitment to sustainable development (Riccaboni & Leone, 2010; Scheyvens et al., 2016; Crutzen et al., 2017).

When it comes to implementing sustainable practices, the economic dimension is still the most important. Although environmental and social issues are urgent, if there is no economic viability, cost reduction, and return on investment, these issues can be disregarded, which reveals that the cost–benefit ratio is fundamental to the adoption of sustainability-orientated MCSs. Thus, the integration of the SDGs often occurs only through legislative and political pressure, rather than being a voluntary initiative (Scheyvens et al., 2016; Crutzen et al., 2017; Albertini, 2019; Nishitani et al., 2021).

According to the SDG Compass, Fleming et al. (2017) argues that the first step in incorporating the SDGs is to ensure a clear and comprehensive understanding, involving all members of the organisation and orienting them towards the SDG targets, and to effectively measure progress toward the SDGs, a specific MCS that monitors result indicators and evaluates the associated costs and benefits is needed.

The recent literature reflects a significant evolution in how sustainable development is integrated into MCSs, marking a shift from surface-level ESG reporting toward deeply embedded sustainability governance. Suhardjo et al. (2025) propose an extended sustainability strategy map and balanced scorecard framework that incorporates environmental, social, cultural, and technological KPIs, enabling businesses to align operational goals with long-term sustainable development. Hasu et al. (2025b) highlight the differentiated roles of diagnostic and interactive control levers in shaping financial performance outcomes under various sustainability strategies, particularly within SMEs. Cruz et al. (2025) further support the strategic value of embedding ESG factors by showing correlations with improved financial, operational, and reputational performance.

Accordingly, sustainability must be integrated into the core MCS architecture to foster adaptability, resilience, and legitimacy in an era of environmental and social urgency. So, MCSs are fundamental for defining and communicating the company’s sustainability strategies and objectives, influencing the practices and behaviours of members, motivating them concerning the SDGs, and monitoring and evaluating sustainable performance and progress towards the SDGs. In addition, they help to manage risks and identify opportunities, since by using them appropriately, they provide a balanced inclusion of the three dimensions of sustainable development (Lueg & Radlach, 2016; Wijethilake, 2017; Crutzen et al., 2017; Traxler et al., 2020; Hasu et al. 2025a).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Purpose and Research Questions

The purpose of this study is to analyse the integration of the SDGs into management control. This study describes how a company is perceived regarding the integration of the SDGs, reflecting the importance of the topic for management and the importance of the public perception about the topic. As such, we address how the integration of the SDGs is publicly communicated, formalised, and operationalised within EDP Group’s MCSs, adopting interpretive research.

This study relies on the Portuguese energy leader company, the EDP Group, recognised for its sustainability performance and cultivated public image. The research questions were defined through a review of the recent literature on sustainable development and MCSs, which revealed a notable gap: while frameworks for integrating sustainability exist, there is a lack of empirical studies exploring how these frameworks are applied in real-world corporate settings, particularly regarding MCSs. Additionally, a preliminary exploratory analysis of EDP Group’s public reports and communications indicated a structured yet evolving approach to SDG integration, suggesting the relevance of an in-depth case study. Based on these insights, the following research questions were developed:

- (1)

- How does the group integrate the SDGs into its business?

- (2)

- How are management practices used to promote the SDGs? What are the group motivations and challenges when integrating sustainability?

- (3)

- What are the key organisational dimensions to integrate the SDGs (following Herath’s theory)?

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

This work is based on an exploratory qualitative method and analyses secondary data, through the group’s reports such as financial reports, sustainability reports, and integrated reports.

It analysed the EDP Group’s public annual reports from 2020 to 2024, along with the company’s indicators and measures, to assess their alignment with the SDGs and the indicators set by the UN. The SDGs were related to the group’s area of activity, to analyse the relationship in the selection of the group’s preferences.

Additionally, supplementary documents released by the EDP Group, such as the sustainability reports, were analysed (see Table 3). To validate the information from the annual reports, relevant content from the group’s website was also examined. Although this corresponds to the final phase of the SDG Compass (reporting and communication), the analysis began with these publicly available documents, as they provided easy access to key information and helped identify the main stakeholders involved in the SDG integration process. In this context, these documents were studied to understand how the EDP Group communicates its management control practices related to sustainable development and its contribution to the SDGs.

Table 3.

Documents analysed.

The complementary, discourse analysis technique was used for public interviews, podcasts, and articles (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Interviews and articles by EDP Group’s main agents.

A case study is a research methodology used to analyse complex social phenomena, allowing for a detailed investigation that preserves the essential and holistic characteristics of events within their natural context (Yin, 2003).

As Riccaboni and Leone (2010) and Scheyvens et al. (2016) emphasise, the mere disclosure of reports does not guarantee that the company is truly committed to integrating sustainable development. Therefore, we used public interviews and podcasts conducted between 2020 and 2024, released by EDP Group and third parties of members of the Executive Board of Directors, and the Environment and Sustainability Board, such as Miguel Stilwell d’Andrade, Vera Pinto Vieira, Miguel Setas, María Mendiluce, José Manuel Viegas, and Rui Teixeira. The speakers were chosen based on their management position in the group, as well as their area of activity, such as sustainability, and their involvement in the process of incorporating the SDGs.

Once the necessary material had been collected on video and in written documents, they were analysed, looking for keywords such as SDGs, sustainability, management, objectives, and strategies. Then, they were organised into four aspects (social, economic, environmental, and management/vision) to complement and correlate the most pertinent information, promote the validation of the data collected, and answer the research questions.

3.3. The EDP Group

The selection of the organisation for the case study should not be arbitrary, but reasoned, considering its economic relevance, size, market share, capacity for innovation, and/or its contribution to the topic in question (Moll et al., 2006; Siggelkow, 2007). In this way, it will ensure that the research questions are adequately answered and that significant insights are gained.

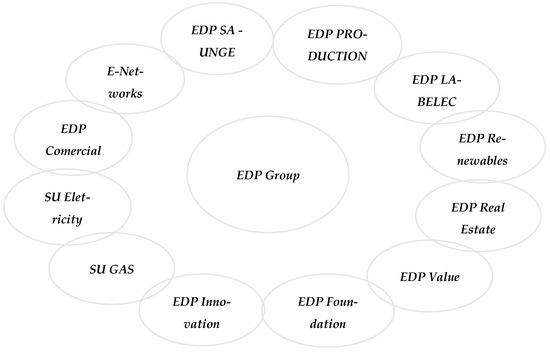

Thus, this study was carried out with the EDP Group–Portugal Energy [Energias De Portugal]. In Portugal, EDP is the largest industrial group and one of the main drivers of the national economy. It is also the main producer, distributor, and supplier of electricity in the country. Energy production is carried out through hydroelectric and thermal generation by EDP Produção and wind generation by EDP Renováveis. Distribution is the responsibility of E-REDES, while energy is commercialised by SU Eletricidade and SU Gás in the regulated market and by EDP Comercial in the free market (EDP, 2017). However, the group is also made up of other companies, as can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Constitution of the EDP Group.

EDP Group is a significant group in the energy sector and one of the market leaders in Portugal. Its economic importance can be reflected in its revenue and job creation. In terms of revenue (EUR 1290 million in 2023), it has been one of the main contributors to the Portuguese economy (EDP, 2023c). As for job creation, the company employed 113.041 employees in 2023, thus helping to sustain the country’s labour force (EDP, 2023b).

The history of the EDP Group goes back to the beginning of the energy sector in Portugal at the end of the 20th century. EDP—Energias de Portugal was founded in 1976 because of the nationalisation and merger of the thirteen main public companies in the sector in the country (EDP, 2017). The last change in EDP Group took place in October 2011, when China Three Gorges was chosen as the new reference partner, acquiring 21.01% of the capital for EUR 2.69 billion, becoming the largest shareholder and guaranteeing crucial funding for EDP Group’s future. This shareholder is followed by Blackrock, Inc. and Oppidium, both representing 7% of capital.

EDP Group has achieved several milestones, including being ranked as the world’s most sustainable electricity company in 2021 by the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, remaining on this index since 2008. With more than 75% of its energy production coming from renewable sources, it was recognised as the third most sustainable utility in Europe. In addition, EDP Brasil achieved first place in the Brazilian Stock Exchange’s Corporate Sustainability Index.

EDP Group operates in three main business areas: renewables (hydro, wind, and solar energy), which are the group’s main growth platform; regulated networks, which cover energy distribution in Portugal, Spain, and Brazil, as well as transmission in Brazil; and customers and energy management, which includes customer services, energy trading and thermal generation (EDP, 2020b). The group’s value chain includes the following activities: production; transmission; energy distribution; and finally, supply, the activity closest to the customer (EDP, 2020b).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Contributions to the SDGs Through Annual Reports

4.1.1. Vision, Values, and Commitments

The company has set its sights on becoming “a global energy company, a leader in the energy transition to create superior value” (EDP, 2021b, p. 34).

As a global energy group, it stands out for its values of innovation, creating value in the various areas in which it operates; sustainability, seeking to improve the quality of present and future generations’ lives; and humanisation, building authentic and trusting relationships with its stakeholders.

Thus, by assuming its vision and values, the group’ commitments are fundamental to its success. EDP Group has defined its commitments as follows: regarding people, it combines rigorous ethical and professional conduct with the promotion of teamwork, encouraging the development of skills and recognising merit; regarding sustainability, it displays social and environmental responsibilities arising from its activities and actively promotes energy efficiency; finally, in terms of results, it fulfils its commitments to its shareholders and strives for excellence in all its operations (EDP, 2023b).

The EDP Group recognises the importance of sustainability in its value chain, incorporating risks and opportunities related to ESG (environmental, social, and corporate governance) criteria into its business strategy, especially those arising from the energy transition. The EDP Group’s sustainability strategy is based on leading the energy transition and making a commitment to the environment and society, according to four fundamental pillars: accelerated and sustainable growth, through the implementation of the investment plan for the period 2023 to 2026; excellence in ESG and an organisation prepared for the future; a distinctive and resilient portfolio; and the creation of superior value for stakeholders (EDP, 2023b).

To preserve the future of humanity and combat climate change, concrete measures have been implemented, as presented in the following points, to become a 100% green company by 2030 and net-zero by 2040, committing to supplying clean energy (EDP, 2023b).

4.1.2. Incorporating the SDGs into the Organisation

Based on corporate responsibility and sustainability, EDP Group has demonstrated a growing commitment over time to align its business practices with environmental, social, and management considerations. The group’s annual reports consolidate and integrate financial, non-financial, social, and environmental information into a single document. Integrated reporting aims to achieve more than just combine financial and sustainability reporting. It is a comprehensive, concise, and simplified approach that communicates how the business model generates value and interconnects the three strands of sustainable development. In this way, it promotes understanding of their interdependencies and supports the creation of increasingly integrated management in organisations (IFRS Foundation, 2021). However, EDP Group also has Sustainability Management Approach Reports, which complement the Annual Report and Accounts and in which the themes established by the GRI methodology are addressed, detailing the relationship between organisational processes and materially relevant themes for society. EDP Brasil managed to achieve first place in the Corporate Sustainability Index of the Brazilian Stock Exchange and in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. EDP Group has consistently ranked highly since 2008, even being considered the most sustainable company in the world.

In this context, EDP Group’s management control practices related to sustainable development and the SDGs have become increasingly prominent in their disclosure.

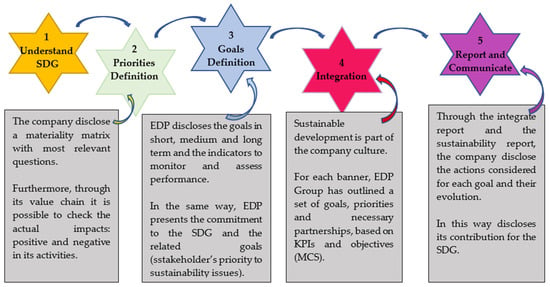

The sustainability strategies created by EDP Group came before the SDGs that appeared in 2015, since it had already been discussing and planning environmental values and commitments since at least 1998–1999. Additionally, the group adopted steps very similar to those defined by the SDG Compass (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The SDG Compass for EDP Group. Source: Adapted from the Global Reporting Initiative, United Nations Global Compact & World Business Council for Sustainable Development (2015, p. 7).

Firstly, the company drew up a materiality matrix, i.e., established the main economic, social, and environmental aspects and their priorities, considering the needs of the business and its presence in the world, with the aim of maximising positive impacts. EDP anticipated the reasons that led to the SDGs, identified the most relevant sustainability issues based on stakeholder priorities and risk assessments, and mapped both positive and negative impacts across its value chain, linking them explicitly to what came to be relevant SDGs. As of 2024, this process has been enhanced through improved stakeholder engagement mechanisms and internal training programs, aligned with evolving global frameworks such as the UN 2030 Agenda, ISSB, and CSRD. Sustainability priorities are supported through stakeholder consultations and the use of impact assessment tools. In 2024, EDP notably expanded its Solidarity Energy Programme, a social initiative aimed at addressing energy poverty and social inequality, thus reinforcing commitments to SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). The introduction of a refined ESG Criticality Matrix also allowed the company to evaluate and prioritise climate and environmental risks more strategically (EDP, 2024a).

The group then defined measurable targets, i.e., ambitions or commitments, through 14 material topics, for short-, medium-, and long-term cycles, as suggested by SDG Compass in the second and third stages. The materiality process also makes it possible to identify the priority that each stakeholder group gives to sustainability issues. A major achievement in 2024 was the company’s success in reaching 95% renewable electricity generation, ahead of previous projections. Additionally, its key performance indicators (KPIs) have been updated to align with the CSRD/ESRS framework and now include metrics for water usage, biodiversity preservation, and aspects related to a just transition.

One of the company’s strategic priorities is strongly linked to the value chain addressed in the SDG Compass since monitoring suppliers ensures that the raw materials used come from supply chains that fulfil traceability and social and environmental assessment criteria and thus provide an efficient supply chain by developing business partnerships that respect sustainability, social, and environmental responsibility criteria.

The integration of sustainable development issues and the SDGs are associated with the fourth stage of the SDG Compass, which in EDP’s case, are reflected in the reports published since 2017. Thus, starting with the 2017 Sustainability Report, the company began to relate the goals set out in the sustainability strategies to the SDGs in this crucial document for communicating with stakeholders. However, this relationship has been frequently adjusted from then until 2023, showing that the company has undergone an evolutionary change in its way of associating itself with the SDGs over the years. From 2018 onwards, the EDP Group demonstrated consistency and began to directly correlate the SDG targets. For each banner, EDP Group has outlined a set of goals, priorities, and necessary partnerships, based on key performance indicators (KPIs) and objectives. Each cause also has its management tools to support strategic planning and decision-making. Sustainability is embedded in the company’s core operations and investment strategy. Initiatives such as community solar projects, electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure, and grid modernisation reflect the integration of sustainability goals. Furthermore, integration is enhanced by the adoption of a TCFD-aligned scenario analysis, ensuring that climate-related risks and opportunities are incorporated into long-term strategic planning.

Thus, following the fifth and final stage of the SDG Compass, this company highlights in its annual reports the ambitions set out in the sustainability strategies for each strategic plan; the impacts generated, both positive and negative; and the plans adopted to deal with these impacts. It is important to note that all the annual reports analysed are duly verified by an independent third party, specifically PricewaterhouseCoopers & Associados-Sociedade de Revisores Oficiais e Contas, Lda (PWC), and follow the guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI Standards). In this way, EDP Group demonstrates its commitment to the principles of transparency, which it promotes, also promoting an image of sustainability commitment. The company publishes both an integrated annual report and a sustainability report, each aligned with the GRI, CSRD, and TCFD standards and externally audited. In 2024, EDP was once again included in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index and the S&P Sustainability Yearbook, underscoring its leadership in ESG performance. The company also reported an 88% reduction in water usage, surpassing its 2025 target. Its communication systems include real-time dashboards, climate transition plans, and detailed updates on SDG-linked performance.

EDP Group states that the SDGs are essential for tackling today’s main environmental and social problems, providing an opportunity to promote the energy transition. The EDP Group uses annual reports and sustainability reports as a relevant communication tool to demonstrate progress in meeting the SDGs and the management practices that support this process, operating as a validation mechanism. Although integration has taken place by correlating the SDGs with the ambitions previously established in the sustainability vision, the steps adopted are like those defined by the SDG Compass (see Figure 4), which tends to achieve the company’s effectiveness in integration.

4.1.3. Management Control and Sustainable Development

Following the group’s strategic alignment and the goals defined for the short, medium and long terms, the EDP Group began to establish its formal planning system, to involve employees in achieving a common positive impact on the organisation internally.

As the group progresses towards the proposed objectives, it refines its operating model to reflect EDP Group’s global presence and guarantee operational excellence in a volatile and uncertain context, relying on the talent of its teams. Thus, taking into account Drury’s (2012) category of behavioural control, the group has several responsible teams that manage the policies in force in the organisation, with knowledge and involvement in the process, such as ethics, compliance, purchasing, health and safety, environment, and people management, among others, policies approved by each of the areas responsible for implementation, and when necessary, offers training to employees to improve their knowledge.

The group’s management control practices also consider risk management intrinsic to the business. Since 2001, the company has adopted a risk management model, which guarantees continuous and preventive monitoring of the business environment, making it possible to anticipate, react to, and mitigate possible adverse events. This model establishes the stages and responsibilities of each participant in the process, including the identification, assessment, and management of risks that could threaten the company’s objectives; the alignment of the climate scenario; and the quantification of risk and aggregate Climate Value Risk, thus corresponding to action or behavioural control. In its annual reports, EDP Group communicates the progress made in identifying, mapping, and developing risk supervision indicators, as well as the updates implemented to the risk matrix and internal controls over the years.

The EDP Group’s risk management model is widely recognised in the specialist literature, based on the concept of the organisation’s three internal lines of defence (business, risk, and audit). In certain circumstances, this model can be complemented by a fourth external line of defence, involving external auditing and regulation/supervision.

The group’s mission, vision, and values, disseminated throughout the company and published in its annual reports, constitute cultural controls, as divided into the category of personnel, cultural, and social controls, according to Drury (2012).

Although economic viability plays a crucial role for EDP Group, the environmental aspect plays an equally essential role in decision-making. Investors are relying less and less on financial metrics alone for their investments and are now using ESG principles to evaluate companies’ performance concerning sustainability objectives.

Through an ESG criticality matrix that combines the relevant risks of the activity, identified through stakeholder consultation and attributed to the sector, with the characteristics of the specifications, criteria are established that the company considers in the analysis: financial, relevance, and business continuity; dependence and autonomy; access to data; facilities; customers; local communities; cybersecurity; emissions potential; waste; environmental accidents; accidents at work; integrity and compliance; and human and labour rights. For example, suppliers only move onto the negotiation phase after passing a rigorous ESG assessment, which includes integrity; legal and ethical aspects; and financial, technical, social, and environmental compliance.

As part of the control of results, EDP Group has been disclosing the main sustainability performance indicators following the taxonomy regulation since 2019. The EDP Group, in compliance with the sustainability reporting directive, needs to implement an Internal Control System for Sustainability Information (SCIRS) by 2025. Although not yet mandatory, this system ensures the completeness, accuracy, and transparency of the sustainability information reported. To prepare for this, EDP Group has designed a project that will guarantee the implementation of the key elements of the SCIRS by 2024.

To monitor progress in relation to the medium- and long-term objectives set, indicators and metrics have been defined that track EDP Group’s performance in its climate initiatives.

The EDP Group recognises that financial indicators alone are not enough to assess the real value generated for society. For this reason, it adopts management practices that integrate formal mechanisms, such as the implementation of strategies, and informal ones, such as leadership, culture, and values, to promote behaviours aligned with sustainable development.

In summary, EDP Group highlights its environmental and social actions, as well as presents symbols of sustainability, such as the Aboño thermal power station in the Green Hydrogen Valley of Asturias. The group shows that these issues are incorporated into the daily activities of all its areas. At the same time, it incorporates the four aspects of sustainable development (economic, environmental, social, and cultural) into its vision and strategic plan. The EDP Group believes that its core values significantly influence the successful integration of the SDGs, as well as defining clear procedures enables the dissemination of its culture and mentality, increasing the understanding of the interrelationship between the environmental, social, and economic dimensions, as well as the level of awareness regarding sustainability goals, in consensus with Jollands et al. (2015) and Fleming et al. (2017). According to Crutzen et al. (2017), the EDP Group shows that cultural management control, being weaker and less imperative compared to formal controls, tends to be more easily implemented and faces less resistance.

The results corroborate the existing literature, which suggests that current business models are unsustainable and that traditional accounting and management control are insufficient for an inclusive analysis of all aspects of sustainable development (Lueg & Radlach, 2016). Thus, the EDP Group is seeking to introduce more tools to support the effective incorporation and disclosure of the SDGs, promoting the definition of innovative measurement parameters that enable greater comparability and transparency of the information disclosed, such as the ISSB.

In line with the literature (Riccaboni & Leone, 2010; Gond et al., 2012; Lueg & Radlach, 2016), EDP Group has also started to integrate sustainable development from the environmental side, as the company believes that the standards in this area are more consolidated, making assessment relatively easier. Regarding the main management control methodologies employed to measure the impact, such as the ESG criteria, the logic was the same: start with environmental accounting and then expand the analysis to the social aspect. Currently, EDP Group claims to use an integrated perspective that broadens the analysis and provides more detailed and accurate data for management, which allows for an effective assessment of the TBL supporting strategic planning and decision-making in a set of organised and more inclusive, assertive, and adapted information on economic, environmental, and social data. In addition, these data become important accountability mechanisms, facilitating the communication and interpretation of information. Thus, the EDP Group states that the main contribution to achieving the SDGs is the sharing of these and other methodologies that it uses for measurement, evaluation, and support for deliberation, allowing the concrete integration of all the perspectives of sustainable development.

4.2. Integrating the SDGs into EDP’s Management Practices: How and Why

4.2.1. Motivations for Integrating Sustainable Development and the SDGs

It is impossible to talk about EDP Group without mentioning sustainability, since the group was created for this purpose from the outset, incorporating concern for environmental and social issues and making them an integral part of its business. As Vera Pinto Vieira, a member of the Executive Board of Directors, says, “We share our purpose with the world, hoping to inspire and mobilise all of society to take care of our planet.” (EDP, 2022, September 26).

In all the executive messages that begin each annual report, integrating its role in sustainability is indispensable. In its 2023 annual report, EDP Group states that “Through sustainable innovation, we want to be part of an endless natural cycle. That is our choice, to give power to every leaf, every drop, every breeze and every sunrise” (EDP, 2023b, p. 3).

Miguel Setas, executive director of EDP Group, sees the three dimensions of the ESG objectives, environmental, social and governance, as “more than a set of topics, this has become our culture” (EDP, 2023a, June 16). The director believes that sustainability is a priority and that it is no longer a side concern or just a department or activity but is now seen as EDP Group’s business. He also points to five priority areas in sustainability for EDP Group. The first is “accelerated decarbonisation,” achieving 100% renewable energy by 2030, elimination of coal by 2025, and Scope 3 carbon neutrality by 2040. The second area is the promotion of a just transition, ensuring net job creation. The third focuses on regenerating the ecosystems where EDP Group operates, and the fourth involves collaborating with suppliers on the “ESG Journey.” The last area is cultural, promoting sustainability values within the organisation. The social and governance dimensions are also fundamental, with management and human resources standing out.

Thus, to effectively reflect EDP Group’s global presence and continuously increase collaboration, efficiency, and agility in decision-making, CEO Miguel Stilwell d’Andrade confesses that they need to improve the company’s organisational model (EDP, 2024b, March 13).

To back up the claim that EDP Group and sustainability are inseparable, it was named the world’s most sustainable utility company by S&P Global CSA for the third time in ten years (EDP, 2023b).

Thus, EDP Group’s cultural MCS stands out, according to the conceptualisation of Malmi and Brown (2008), as the main guideline for the commitments and purposes assumed in the context of sustainability. However, as Hewege (2012) points out, the relationship between management control and human behaviour can be complex due to the individual differences of people, the context, and the organisation. Therefore, culture alone is not enough to guide and direct employee behaviour.

In this context, and the conceptualisation of Malmi and Brown (2008), which highlights the importance of administrative MCSs, it is not enough for a company to only have a corporate culture geared towards sustainable development, since it is also necessary to establish standards and rules to minimise possible conflicts in meeting goals.

The Executive Board of Directors also emphasises the importance of long-term reward systems for top management and for critical positions in the senior management segment, which not only encourage members to align themselves with the defined objectives and achieve results but also show the serious commitment of EDP Group and its employees to the subject and eventually attract and retain talent. In 2023, this global approach was extended to the various benefits offered to employees in the different markets where EDP Group operates, establishing a common global offer, complemented by specific local benefits.

In summary, one of the main reasons for companies to adopt sustainable development and the SDGs in management practices, as stated in much of the previous literature (Wijethilake, 2017; Crutzen et al., 2017; Albertini, 2019; Johnstone, 2020; Pizzi et al., 2021; Nishitani et al., 2021), comes from a slight pressure from stakeholders, and according to the discourse of the main representatives, EDP Group’s motivation comes essentially from the company’s culture. The results show that the integration and effective promotion of sustainable development and the SDGs are only possible through cultural and, consequently, behavioural change. Thus, EDP Group promotes networking, as suggested by the SDG Compass, with employees spreading the knowledge acquired and acting as agents of transformation.

4.2.2. The Challenges of Integrating the Environmental and Social Dimensions

Both the environmental and social dimensions have gained prominence in recent years. In the social sphere, the current targets seek to address issues such as inequality, diversity, and income distribution and promote a positive impact in this area.

María Mendiluce, a member of the Environment and Sustainability Council, states that tackling social inequalities is a major challenge today. She stresses that it is essential to understand that climate, nature, and social equality are deeply interconnected, requiring holistic approaches to address these issues. As an example, she mentions that the climate transition must truly include people, whether through retraining workers, providing clean and affordable solutions to consumers, or collaborating closely with companies in the value chain so that they also transform themselves (EDP, 2021a).

In the environmental field, José Manuel Viegas, chairman of the Environment and Sustainability Council, points to several challenges, namely the rapid technological evolution and the need to keep up with it. However, the main challenge he points to is the inevitable profound change in the business model. In other words, although EDP Group has a very competent technical structure and a healthy relationship with start-ups in the technological area and business models and is, therefore, able to respond to the challenge of rapid technological evolution, there is consequently a delay in regulation and reaction to the new emerging rules, making it a very difficult path for companies in sectors of great importance. Allied to this is the fact that there is an energy transition, where there is greater efficiency in the electrical vector compared to the energy sector, and the migration to renewable sources, which results in a change in marginal production costs that in turn changes business models (EDP, 2020a).

However, even though the environmental dimension has a more consolidated agenda, the methodologies and metrics focused on this dimension continue to evolve, with the private sector increasingly mobilizing to set new standards. Financial and sustainability reports are increasingly integrated, and companies tend to face greater scrutiny from investors regarding their climate recommendations. María Mendiluce states that “Being responsible for climate actions and being able to transparently disclose climate-related financial information will become an obligation in the coming years.” (EDP, 2021a, p. 37).

According to the CFO, Rui Teixeira, there is another barrier that has been a challenge for the company, namely the fact that the global financial system does not yet support ESG factors as a standard, that is, its reporting is voluntary and therefore not universal, which makes public information not very comparable and not always verified (Sustainable Finance, 2022, December).

In addition, EDP Group’s certifications act as references and proof of the company’s commitment, in which they not only help to legitimise the company before consumers and shareholders but also serve as guides for best business practices, since certification processes are frequently updated with the latest market trends.

The important challenges for incorporating sustainable development and the SDGs into management practices are in line with many presented in the literature. The lack of standardised metrics and KPIs for evaluating social and environmental impact continues to hinder meaningful measurement and comparison of SDG progress across the firm. This issue is well documented by Fleming et al. (2017) and Crutzen et al. (2017), who argue that most companies rely on qualitative disclosures or symbolic gestures rather than robust, data-driven indicators. Also, Gond et al. (2012) already emphasised that while MCSs can support sustainability integration, they struggle to cohesively align across financial, social, and environmental dimensions—something that many firms, including EDP, are still evolving toward. The dynamic and evolving regulatory landscape presents another challenge. Nishitani et al. (2021) pointed out that regulatory uncertainty and the lack of harmonised ESG disclosure standards, such as varying adoption timelines for the EU CSRD or ISSB frameworks, make it difficult for companies to anticipate compliance requirements or design long-term strategies. Regarding the challenge of the internal cultural shift required for authentic SDG integration, Lueg and Radlach (2016) argued that integrating sustainability is not merely about tools or KPIs but also about reshaping corporate culture, which is often slow and uneven. EDP’s emphasis on cultural controls reflects this, yet behavioural alignment across all levels of the organisation remains a long-term effort. Finally, stakeholder pressures may lead to selective SDG adoption—what Doyle (2016) and Pizzi et al. (2021) describe as “SDG cherry-picking,” where firms focus on easily attainable or reputation-enhancing goals while neglecting more systemic or complex issues. This reduces the comprehensiveness and authenticity of SDG alignment.

4.3. EDP Group’s Key Organisational Dimensions to Integrate SDGs

Regarding the management control practices disclosed for the integration of the SDGs, a detailed analysis of the comprehensive approach of formal and informal systems of the conceptual framework of Malmi and Brown (2008) reveals that the EDP Group reports applying a structure of the MCSs discussed by the author Herath (2006), presenting the following results:

- ▪

- Structure and Organisational Strategy

Through its governance structure and risk and opportunity management, EDP Group communicates that it establishes management guidelines, principles, and responsibilities, as well as actions for mapping, monitoring, analysing, controlling, and communicating the goals aimed at sustainable development and the SDGs. In addition, the ISO and SIGAC (Corporate Environmental Management System) certifications that EDP Group has also function as organisational strategies, as these are formal and standardised structures that not only legitimise the company but also help to implement the best procedures and practices. Thus, although it is a commitment shared by all members of the organisation, EDP Group has a formal structure with a sustainability department. This department is responsible for defining policies and procedures that balance social, environmental, and economic aspects. In addition, the company has a code of conduct for the entire group and a specific one for suppliers, to guide and align its actions. EDP has a MCS that tries to operationalise SDG commitments, especially through formal governance bodies and reporting mechanisms in line with the study of Gürbüz and Gürbüz (2025).

- ▪

- Organisational Culture

The EDP Group’s organisational culture is shaped by a set of values and practices, which reflect an ongoing commitment to sustainability, innovation, and social responsibility. The company has a strong emphasis on sustainable practices and environmental responsibility, as it is committed to the energy transition and the reduction in carbon emissions, promoting renewable energies and projects that minimise environmental impact. Allied with this commitment, innovation is also a central pillar in the EDP Group’s culture, as it invests in new technologies and solutions to improve energy efficiency and the customer experience, such as the development of smart grids, electric mobility, and research and development projects for renewable energies, not forgetting the corporate social responsibility integrated into EDP Group’s operations.

- ▪

- Information Management Systems

To measure and evaluate the performance of the established standards, EDP Group informs that it defines a series of indicators, which make it possible to recognise possible deviations and make the necessary corrections to achieve the defined goals. The company uses annual reports to communicate the level of achievement of targets and the status of performance. In addition to feedback mechanisms, EDP Group also uses forecasting mechanisms, which means that the company is committed to making predictions and identifying possible risks and impacts caused by its products or business model in advance, which allows it to develop mitigation methods before these impacts occur.

These three components represented here of Herath’s SCG (Herath, 2006) interact with each other to form a core set of organisational control mechanisms and practices, which results in an effective system if both are compatible. From management and administration to the practice of all employees and business units, the goal is the same at EDP Group: the energy transition and the creation of value for all stakeholders.

Table 5 provides a structured visualisation of how EDP Group integrates the SDGs into its corporate strategy and operations, using the SDG Compass framework (Global Reporting Initiative, United Nations Global Compact & World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2015) as a process model and Herath’s (2006) MCS dimensions as an organisational lens. Each cell illustrates concrete practices aligned with a specific SDG Compass stage and a corresponding element of organisational structure, culture, or information systems.

Table 5.

Mapping EDP’s SDG integration via SDG Compass and Herath’s dimension.

This dual-framework approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of SDG integration by highlighting not only what actions EDP undertakes (e.g., materiality analysis, stakeholder engagement, and ESG metrics) but also how these actions are embedded within internal systems and routines. For example, the inclusion of community solar projects and electric vehicle infrastructure in the core business strategy demonstrates both strategic alignment (SDG Compass Stage 4) and a shift in organisational culture toward innovation and decarbonisation (Herath’s cultural dimension).

5. Conclusions

The incorporation of the SDGs is an important factor for sustainability management and control, which, in a way, serves to start broadening the scope for companies to reflect on social and environmental issues as well. In this context, studying how companies incorporate the SDGs and sustainability-related issues into their management control is pertinent.

Based on the EDP case study, this research aimed to analyse the evolution of the communication of management control practices aiming at the SDGs, focusing mainly on the company’s annual reports, to understand the motivations that led the company to incorporate the SDGs into its management and to investigate the challenges that the integration of the SDGs imposes on these practices. As we sustain this paper with reports of EDP, though some are reviewed by proper entities, we do analyse the image that EDP projects of itself regarding the integration of SDGs in the organisation. As we did not resort to other sources, we take our findings with some caution, purporting them as the way EDP publicly sees itself in this topic. Taking this into account, we believe these findings are important because they show an effort in projecting the image of an enterprise committed to sustainability through the integration of the SDGs, and so putting forward a proper understanding of how this can be achieved.

According to the cross-referencing of company information, it is possible to see that the environmental aspect is as important as the economic aspect in the company’s viability analysis, and the social dimension has gained the prominence it deserves, being increasingly integrated. Thus, the results indicate that contrary to what the literature suggests (Scheyvens et al., 2016; Crutzen et al., 2017; Albertini, 2019; Nishitani et al., 2021), for EDP Group, economic viability does not play a more prominent role compared to the other aspects. EDP Group also considers that by eliminating trade-offs and effectively including the three dimensions, it is possible to obtain several benefits, which is in line with the research of Sachs (2004), Langlois et al. (2012), Ghisellini et al. (2018), and PwC (2015, 2019), in which the PwC suggests that this approach guarantees the company a prominent position among consumers and investors, who are increasingly demanding corporate sustainability. It also allows the company to respond more assertively to regulatory requirements and reduce legal risks. This approach provides EDP Group with efficiency and productivity gains, as indicated by the SDG Compass, resulting in truly sustainable growth. In addition, it strengthens the company’s image, increases trust in the brand, and strengthens relations with all stakeholders, considering it to be a source of differentiation and competitive advantage.

EDP Group uses its annual and sustainability reports as an important communication tool to highlight progress in meeting the SDGs and the management practices that support this process, acting as a validation mechanism. Although the integration took place by aligning the SDGs with the targets previously established in the sustainability vision, the steps adopted are like those defined by the SDG Compass, which tends to guarantee the company’s effectiveness in the integration. Through the integrated reports and the speeches of its main representatives, it is possible to observe the company’s actions and contributions to each of the SDGs.

Although the SDGs were aligned with the sustainable development goals that EDP Group had already established and did not serve as a basis for defining them, the main challenge reported by the company is in line with the literature (PwC, 2015; Lueg & Radlach, 2016; Crutzen et al., 2017; Fleming et al., 2017; Johnstone, 2020; Silva, 2021), namely the issue of measurement. There is still a lack of standardised indicators capable of supporting the implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of corporate sustainable development and the contribution of companies to the SDGs. In addition, traditional management control is considered inadequate for evaluating environmental and social practices and integrating them into the economic dimension, which often requires adapting existing models or creating new ones that can promote these objectives (see Lueg & Radlach, 2016). Through the analysis of EDP Group’s annual reports over time, it was possible to conclude that the company has continually sought to improve the control mechanisms used, as well as look for tools to resolve these issues, developing new measurement standards that also act as accountability mechanisms. This is the case with the ESG criteria, as it broadens the analysis of the accounting content, integrating more and more economic, social, and environmental data, which is more detailed and accurate for management, allowing for an effective assessment of the TBL.

The results of this study indicate that the main motivation mentioned by EDP Group for integrating the SDGs into its management control practices is related to stakeholder engagement and to its culture and values, highlighting the importance attributed to the cultural MCS, in line with the observations of Lueg and Radlach (2016). The company considers the cultural dimension to be one of the central pillars of sustainable development. Although pressure from stakeholders and legislative issues play an important role in integrating sustainable development and promoting the SDGs, this process only becomes possible and effective through cultural change. In other words, it must guide employee behaviour so that it is aligned with the company’s objectives and decisions on environmental and social issues, integrating them into daily activities.

In the context of the empirical study, this work follows the theoretical lens of Herath (2006) to analyse the organisational dimensions. It highlights the pivotal role of strong corporate culture and a commitment to sustainability in driving SDG integration. EDP Group’s emphasis on environmental and social responsibility, coupled with the implementation of formal MCSs, has facilitated the alignment of its business strategy with the SDGs. However, challenges such as the lack of standardised metrics for measuring social and environmental impact and the evolving regulatory landscape continue to hinder progress. This study maps practices across Herath’s (2006) management control and the SDG Compass Framework and develops a matrix that not only showcases EDP’s progress but also serves as a replicable tool for other organisations aiming to operationalise the SDGs within their control systems.