Abstract

This research examines social entrepreneur competencies and the ability to create value through social innovation, which affect sustainability in Thai social enterprises. The study used questionnaires administered to 200 social enterprises registered with the Social Enterprise Promotion Office. The data were analyzed using structural equation modeling. The results showed that social entrepreneur competencies had the highest overall mean among causal factors, while sustainability in social entrepreneur groups had a high mean level. The study found that visionary leadership was the strongest indicator of social entrepreneur competencies, marketing innovation was the strongest indicator of innovation capability, and environmental performance was the strongest indicator of sustainability outcomes. Social entrepreneur competencies strongly influenced the ability to create value through social innovation (β = 0.972), which in turn significantly affected sustainability outcomes (β = 0.707). The study’s limitations include its cross-sectional nature and its focus solely on registered social enterprises. These findings can guide policy formulation to help enterprises create value through social innovation and achieve sustainable success.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

Over the past two decades, business organizations have increasingly acknowledged their social responsibilities, largely due to local, regional, and international pressures affecting their operations. These pressures have prompted entrepreneurs to adapt to stakeholder expectations, particularly regarding social aspects. This adaptation has led to the emergence of social entrepreneur groups and social enterprises, resulting in the rapid expansion of the social business model (Halsall et al., 2022; Ascencio et al., 2024). Social enterprise represents a new business concept established with a primary social goal, focusing on addressing problems related to communities, society, and the environment rather than pursuing maximum profit (Jewer et al., 2023). This operational approach aligns with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to eradicate social problems and comprehensively protect the environment (Fiandrino et al., 2022). This approach emphasizes social responsibility within economic development while safeguarding environmental resources for future generations. It provides diverse social groups with opportunities to actively participate in sustainable development (Docherty et al., 2009) by fostering collaboration between the business and social sectors. Success is pursued in accordance with established goals while cultivating corporate sustainability across three balanced areas following the “Triple Bottom Line” principle (Elkington & Rowlands, 1999), which encompasses economic, social, and environmental performance (Allinson et al., 2012).

Social enterprises in Thailand concretely began in 2009. The government and agencies in various sectors realized the importance of the concept of social enterprise and applied it to business operations in Thailand, seeing that social enterprises will be one way to help bring back and develop the stability and sustainability of national economic and social conditions. The development of social enterprises in Thailand aligns closely with the nation’s economic policies and development frameworks. The Thai government has recognized social enterprises as crucial vehicles for addressing societal challenges while contributing to economic growth. This recognition is evidenced in Thailand’s 20-Year National Strategy (2018–2037) (Pokpermdee, 2020) and the 13th National Economic and Social Development Plan (B.E. 2023–2027) (Yothasmutr, 2008), which emphasize inclusive growth and sustainable development. These national policies specifically support social enterprises through targeted initiatives such as tax incentives, capacity-building programs, and dedicated funding mechanisms. Additionally, the Board of Investment (BOI) has created special categories for social impact investments, further integrating social enterprises into the broader economic strategy. This policy environment demonstrates Thailand’s commitment to fostering a social economy where business operations simultaneously generate economic returns and deliver social impact.

The Social Enterprise Promotion Act B.E. 2019, which was enacted to determine measures to promote, support, assist, and develop social enterprises and social entrepreneur groups, has been effective from 23 May 2019 onwards. These measures are also consistent with Thailand’s current economic policy, which follows the goals of sustainable development within the framework of the national development plans: the 20-Year National Strategy 2018–2037 and the 13th National Economic and Social Development Plan (B.E. 2023–2027). The mentioned policies focus on accelerating the development of the potential of small and medium-sized enterprises and community enterprises and creating opportunities for them to generate income and grow steadily. The policies and legal measures of the government sector mentioned above are a good starting point for promoting social enterprises in Thailand. However, the guidelines for promoting a new paradigm of social enterprises in Thailand are still in the formation process. Through the advancement of digital technology, the traditional community economy has gradually disappeared, making businesses create value through innovation.

The timing of this legislation coincided with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly affected social enterprises in Thailand and globally. The pandemic created both challenges and opportunities for social innovation in these organizations. On one hand, social enterprises faced operational disruptions, funding constraints, and market volatility that threatened their sustainability (Weaver, 2023). Many social enterprises experienced decreased revenues and difficulties maintaining their workforce during lockdown periods (Gigauri & Djakeli, 2021). On the other hand, the pandemic intensified the importance of social innovation as communities faced unprecedented health, economic, and social challenges. Social enterprises demonstrated remarkable adaptability by pivoting their business models and developing innovative solutions to address pandemic-related needs (Shaheen et al., 2023). The implementation of the Social Enterprise Promotion Act during this critical period provided timely institutional support that helped many Thai social enterprises weather the crisis. Government-backed funding mechanisms, tax incentives, and capacity-building programs established under the Act became even more crucial as traditional revenue streams diminished (Thotongkam et al., 2023). Additionally, the pandemic highlighted the essential role of social enterprises in addressing systemic vulnerabilities, potentially accelerating public awareness and support for the social enterprise sector in Thailand (Chienwattanasook et al., 2023). This convergence of legislative support and pandemic-induced innovation pressures may have catalyzed the more rapid development of social innovation capabilities among Thai social enterprises than would have occurred under normal circumstances.

The Theory of Economic Development emphasizes conducting scientific and technological research and development and acquiring innovative technology. Innovation is likely to be a threshold to technology acceptance, simultaneous with creative thinking (Raheem, 2019). In a study by Dees (2016), the Father of Social Entrepreneurship Education, he stated that social entrepreneurship education is one of the branches of entrepreneurs’ theory, involving the crucial principle of building total business and economic growth by being more applied to finding solutions to social problems, becoming what is known as social entrepreneurs, linking social missions and business principles as well as innovation and cooperative decision-making, in addition to seeking an effective approach to advancing society, focusing more on discipline and accountability. This significantly increases social efficiency in problem-solving. Therefore, entrepreneurs necessarily have the competencies to be social entrepreneurs (Dess et al., 2021), using their focus on social business and interest in innovation as strengthening tools to differentiate them from competitors. Therefore, social entrepreneurs are like innovators, as innovation and technology are tools that open up entrepreneurs’ marketing opportunities for competitiveness, leading to success and sustainability in operations (Baron & Tang, 2011). However, management research on the ability to create value through innovation has been limited, without any clear conclusions. In this study, the related literature was reviewed, and we found that the important factors that are expected to result in the ability to create value through innovation include social entrepreneurship competencies since leaders set strategies or goals and allocate resources for all activities that contribute to organizational objectives (Banerjee et al., 2003). When social entrepreneurs have the ability to create value through innovation, they may lead to sustainable performance using the triple bottom line approach with indicators in three areas—environmental, social, and economic—combined with a balanced scorecard (BSC).

1.2. Research Gap and Contributions

Despite the increasing importance of social entrepreneurship both in Thailand and globally, significant research gaps remain in our understanding of how social entrepreneur competencies translate into value creation through innovation and sustainable outcomes. The literature on social entrepreneurship has evolved considerably over the past decade, yet important theoretical and empirical questions remain unaddressed. As noted by Ramadani et al. (2022), most research has focused either on conceptualizing social entrepreneurship or examining isolated aspects of social enterprise operations without providing integrative frameworks. Similarly, Pansuwong et al. (2022) highlight that, while innovation is frequently cited as central to social entrepreneurship, the specific mechanisms through which social entrepreneurs develop and deploy innovation capabilities remain underexplored, particularly in developing economy contexts.

The existing literature reveals three significant gaps that this research aims to address. First, there is limited empirical evidence on how specific social entrepreneur competencies influence innovation capabilities within social enterprises. While studies such as that by Li et al. (2020) have examined entrepreneurial leadership in conventional business contexts, the unique combination of visionary leadership, social responsibility, and stakeholder collaboration that characterizes social entrepreneurship requires distinct theoretical treatment. Second, the mechanisms through which different types of innovations—process, product, and marketing—create social value remain insufficiently understood. Mursalzade (2024) notes that most innovation research in social enterprises focuses on outcomes rather than the value creation processes themselves, leaving a significant gap in our understanding of how innovative capabilities translate into tangible social and environmental benefits.

Third, there is limited knowledge about how these innovations contribute to triple bottom line sustainability outcomes, particularly in the unique context of emerging economies like Thailand. Chijere (2024) observes that sustainability measurements in social enterprises often lack theoretical grounding and contextual sensitivity, resulting in models that may not accurately capture the relationship between innovation capabilities and sustainability performance in specific cultural and institutional environments. This gap is particularly pronounced in Southeast Asian contexts, where according to Pansuwong et al. (2022), social enterprises operate within distinctive institutional arrangements that shape how entrepreneurial competencies manifest in innovation outcomes.

By addressing these interconnected gaps, this research contributes to advancing both theory and practice in social entrepreneurship. The study investigates the relationships between social entrepreneur competencies and innovation capabilities, examines how these capabilities create value across different innovation types, and identifies which dimensions of competencies and capabilities have the strongest influence on sustainable outcomes in Thai social enterprises. This comprehensive approach extends beyond the fragmentary examinations that have characterized much of the existing literature [ref] and provides an integrated framework for understanding the path from entrepreneurial competencies to sustainable impact in social enterprises.

The existing literature has primarily focused on either social entrepreneurship as a concept or innovation management in conventional businesses, with limited integration of these domains in the context of social enterprises. Specifically, there is insufficient empirical evidence in the following areas:

- How specific social entrepreneur competencies (visionary leadership, social responsibility, and stakeholder collaboration) influence innovation capabilities within social enterprises.

- The mechanisms through which process, product, and marketing innovations create social value.

- How these innovations ultimately contribute to triple bottom line sustainability out-comes in the unique context of Thai social entrepreneurship.

This research aims to examine the relationship between social entrepreneur competencies and the ability to create value through social innovation, and how these factors influence sustainability in Thai social enterprises. The study employs structural equation modeling to analyze the causal relationships between these variables, with a particular focus on innovation in processes, products, and marketing approaches. The findings provide valuable insights into organizational efficiency in business management and responsiveness to customer and social needs. These insights reflect management practices that prioritize addressing social problems, leading to sustainable long-term outcomes rather than focusing exclusively on profits. By properly developing social entrepreneur competencies and emphasizing innovation capabilities, government policies and social entrepreneurs can effectively drive sustainable social enterprise development.

The present study makes several distinct theoretical contributions. First, it integrates social entrepreneurship theory with innovation management frameworks specifically in the context of developing economies, where institutional voids create unique challenges for social value creation. Second, while previous research has examined either social entrepreneur competencies or innovation capabilities separately, this study provides a comprehensive framework that explains the mediating mechanisms through which specific entrepreneurial competencies translate into social innovation capabilities and ultimately sustainability outcomes. Third, the research extends the application of dynamic capabilities theory to the social enterprise context by demonstrating how innovation capabilities enable adaptation to complex social and environmental challenges in resource-constrained environments.

Our research findings offer significant contributions that extend beyond Thailand to other regions, including East Asia, the Middle East, and European countries. For East Asian nations with similar cultural contexts and developing social enterprise ecosystems (such as Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia), this study provides a validated framework for understanding how entrepreneurial competencies can be channeled into effective social innovation. The demonstrated relationship between social entrepreneur competencies and innovation capabilities offers these countries a roadmap for capacity-building programs that target specific entrepreneurial skill development. For Middle Eastern countries seeking to diversify their economies and address social challenges simultaneously, this research highlights the potential of social entrepreneurship as a sustainable development mechanism that integrates social responsibility with business innovation. The findings on the primacy of marketing innovation may be particularly relevant to economies transitioning toward more diversified, knowledge-based structures. European countries, despite having more established social enterprise sectors, can benefit from this research through its integration of innovation capabilities as a critical mediating factor between entrepreneurial competencies and sustainability outcomes. This perspective may help refine existing support programs by emphasizing the development of specific innovation capabilities alongside traditional entrepreneurial skills. Additionally, the demonstrated importance of environmental performance in sustainability outcomes offers valuable insights for countries worldwide as they work to align business operations with climate action initiatives and the Sustainable Development Goals.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the concepts, theories, and related research that form the foundation of this study, including detailed discussions of social innovation, social entrepreneur competencies, and sustainability outcomes. Section 3 outlines the research framework and hypothesis development. Section 4 describes the research methodology, including population and sample selection, data collection procedures, measurement scale development, and data analysis techniques. Section 5 presents the empirical results of the study, including descriptive statistics and structural equation modeling analysis. Section 6 discusses the findings in relation to the existing literature and theoretical implications. Finally, Section 7 concludes with a summary of key findings, practical implications, the limitations of the study, and directions for future research.

2. Concepts, Theories, and Related Research

2.1. The Concept of the Ability to Create Value Through Social Innovation

The ability to create value through social innovation means the ability to create value through the business practices in managing innovation in the incessantly changeable strategic management context of production, and the rate of situational changes will be a driving force that increases the potential of technology serving customer needs and its competitive ability. To create innovation in a business requires many innovative issues, taking into account relevant factors from diverse sectors, starting with products or services, organizational structure, technological processes, and management system plans that are related to personnel within the organization (Atkočiūnienė & Siudikienė, 2021). This concept is an important business strategy that must necessarily be taken into consideration practically in both production and services in order for modern society to sustain technological development and changes, enabling loss reduction and efficient ecosystem improvement (Khan et al., 2016). As for consumers, Kang et al. (2012) stated that today’s consumers are willing to pay money for valuable products and services, such as environmental friendliness. This is consistent with Purnomo et al. (2015), who said that the ability to create value through social innovation will be key to sustainable operating results and efficiently help business operations in terms of social and environmental dimensions. The factors influencing the ability to create value through social innovation in this research include the following:

Creating value through process innovation: This is the application of new ideas, methods, or processes that clearly result in an effective production process and overall workflow (Špacek & Vacík, 2016). The efficiency in most innovative process is focused on quality control, constant production efficiency, and operation improvement, as well as on activities or processes related to systems within the organization. In other words, input factors, processes, and outputs. It consists of reducing production costs and time in addition to production process development by placing an emphasis on social and environmental principles (Huarng et al., 2011).

Creating value through product innovation: This refers to developing and introducing products that are new in terms of technology or improving the quality of existing products. Product innovation is a product of business that can possibly take the form of new products or services. The main important variables in product innovation development are technological opportunities and market needs, using the concept of C. L. Wang and Ahmed (2004). Product innovation consists of producing high-quality products with uniqueness that are difficult to imitate, mainly emphasizing social and environmental principles.

Creating value through marketing innovation: This refers to a form of innovation related to improving the marketing mix among target customers and determining the most appropriate products or services for typical markets. Marketing innovation aims to determine new potential markets in addition to new presentations for introducing products and services. The selection of markets for better presentations to target customers employs the concept of Lin et al. (2010). It adapts new marketing methods, including market changes, pricing methods, distribution channels, and marketing promotion development, by placing an emphasis on social and environmental principles.

2.2. The Influence of Social Entrepreneur Competencies on the Ability to Create Value Through Social Innovation

From the reviewed literature, it was found that social entrepreneur competencies, which are considered as support within the organization for generating the ability to create value through innovation, comprise the following properties to be used as research guidelines: (1) visionary change leadership; (2) being environmentally and socially responsible; (3) collaboration with stakeholders. These are discussed below:

Visionary change leadership refers to a leader’s ability to use ideological influence to convey their vision to subordinates in order to carry out work for the public’s benefit, potentially inspire and clearly communicate the need for changes, and stimulate those below them to express their opinions on the environmental analysis affecting the business in order to create a concept of operations that is consistent with changes. This concept comes from transformational leadership theory, which is consistent with contingency theory, explaining that the most appropriate organization is one that has a structure and system that can adapt to the environment and real situations of the organization. Therefore, contingency theory is consistent with the environment of current business organizations with rapid and drastic changes. This is consistent with Epstein (2018), who gave importance to leadership, emphasizing developing and implementing development strategies sustainably in addition to communicating the organization’s sustainability to both internal and external stakeholders. The concept of visionary change leadership arises from the pressure of Corporate Social Responsibility (Mostovicz et al., 2009), which is an important starting point for the concept of transformational leadership, especially in being socially and environmentally responsible for the environment and being able to create value through innovation to achieve sustainability.

Being environmentally and socially responsible means conducting business activities with social responsibility, giving importance to social awareness, connecting marketing with society, solving social problems with a focus on behavioral changes in the environment and health, and promoting the awareness of changes. In addition, according to the literature review and regarding the results obtained for social responsibility, social responsibility has a positive impact on organizations in various aspects, including on the organization’s reputation. Social responsibility will create awareness of the organization’s values in diverse dimensions from the perspective of stakeholders (Zaki et al., 2025).

Collaboration with stakeholders refers to the ability to integrate with downstream parties such as customers, communities, and stakeholders. This creates a network relationship between individuals, groups, and organizations with the same target, aiming to have mutual benefits, to potentially meet customer needs with products and services, and to coordinate cooperation with stakeholders, leading to acceptance and trust in operating, continuous organizing activities, and supporting cooperative activities, in addition to merging benefits between stakeholders. The ability to integrate with stakeholders will promote rapid responses and operational improvement, increasing competitive potential in more global markets. It opens an opportunity for them to take part in decision-making in work operations. This interdependence creates a competitive advantage for a business. This is in accordance with the study of van Hoof and Thiell (2014), which found that when a business has the ability to integrate with stakeholders it will generate development in various dimensions, leading to the ability to efficiently create value through innovation. From this connection mentioned, the research team determined the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Social entrepreneur competencies have a positive direct influence on the ability to create value through social innovation in social entrepreneurship in Thailand.

2.3. The Results of the Ability to Create Value Through Social Innovation Towards Sustainability in Social Enterprises in Thailand

Sustainable corporate performance refers to the integrated results of operations in various areas of organizations, leading to continuous, balanced, and sustainable growth. It consists of three areas: economic performance, social performance, and environmental performance. The sustainable corporate performance of an organization is its ability to create balance among the triple bottom line (TBL), which focuses on the ability to manage and create financial performance, Corporate Social Responsibility, and environmental outcomes. A sustainable organization must have a strong financial management ability, be resistant to economic and social crises, and be able to maintain leadership in the relevant market (Kantabutra & Avery, 2011).

Concerning the concept of a balanced scorecard (BSC), Kaplan and Norton presented a concept for measuring the performance of organizations which can be used as a tool for evaluating performance, not only from financial perspectives but also from non-financial performance perspectives (Galbreath, 2018) by applying the triple bottom line principle. This encourages operating a business while focusing on the balance between economy, society, and environment in order to be an organization that grows sustainably with the same concept in the same direction.

Signaling theory offers another important theoretical perspective on why non-financial performance measurement matters. This theory suggests that in contexts of information asymmetry, organizations use observable actions or characteristics to signal their unobservable qualities or intentions to external stakeholders (Cui et al., 2016). Social enterprises face substantial information asymmetry challenges, as their social value creation is often difficult for external stakeholders to directly observe or verify. By implementing comprehensive measurement systems that capture social and environmental impacts, these enterprises can signal their commitment to social missions and distinguish themselves from organizations that merely engage in “social washing” (Locatelli et al., 2025). This signaling becomes particularly important in competitive funding environments or when trying to attract socially conscious consumers and partners.

Furthermore, stakeholder theory provides additional justification for balanced performance measurement. Unlike the shareholder primacy model that dominates conventional business thinking, stakeholder theory argues that organizations should be managed for the benefit of all the stakeholders affected by their operations (de Gooyert et al., 2017). For social enterprises, whose very existence is predicated on creating value for diverse stakeholders beyond shareholders, measuring performance across multiple dimensions becomes an operational necessity rather than just a strategic choice.

It is suggested that successful business should not be measured only in financial performance but also social and environmental aspects. This concept has since been used as an indicator in the sustainability report guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (Blackburn, 2012). The triple bottom line concept potentially helps the management of business organizations proceed to the stage of sustainable development (Figure 1). From the above connections, the research team established the following hypothesis.

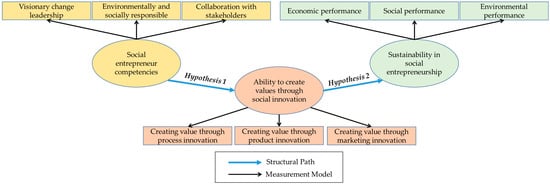

Figure 1.

Research framework.

Hypothesis 2:

The ability to create value through social innovation has a positive direct influence on the sustainability of social entrepreneurship in Thailand.

The relationship between innovation capabilities and sustainability outcomes has been extensively explored in the literature, though with varied findings. Numerous studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between the ability to create value through innovation and sustainable performance outcomes. For instance, Howaldt and Schwarz (2017) found that social innovation capabilities directly contribute to both social impact and organizational sustainability in social enterprises. Similarly, Biggeri et al. (2017) demonstrated that social entrepreneurs who effectively develop innovation capabilities are more likely to achieve triple bottom line outcomes.

The mechanisms through which innovation capabilities translate into sustainability outcomes have been investigated from different perspectives. Azmat (2013) identified three key pathways: (1) innovation enabling more efficient resource utilization, leading to economic sustainability; (2) innovation creating novel solutions to social problems, enhancing social performance; (3) innovation developing environmentally friendly processes and products, improving environmental performance. These pathways align with this study’s conceptualization of how innovation capabilities influence sustainability.

However, some researchers have presented contrasting views. Galindo-Martín et al. (2020) argued that the relationship between innovation and sustainability in social enterprises is not always straightforward, as tensions between commercial and social objectives can complicate the translation of innovation into sustainable outcomes. Similarly, Chijere (2024) suggested that, without proper governance mechanisms, innovations might not consistently lead to enhanced sustainability performance.

In the specific context of Thailand and Southeast Asia, Pansuwong et al. (2022) found that social enterprises with strong innovation capabilities were better positioned to navigate institutional voids and achieve sustainable performance. This aligns with our hypothesis that the ability to create value through social innovation positively influences sustainability outcomes in Thai social enterprises.

The process through which innovation capabilities create value that contributes to sustainability involves several steps. First, according to Selloni and Corubolo (2017), social innovations generate new ideas, products, or processes that address social needs more effectively than the existing alternatives. These innovations then create value by improving resource utilization efficiency (economic dimension), enhancing community well-being (social dimension), and reducing environmental impacts (environmental dimension). As Mursalzade (2024) noted, this value creation process is not linear but iterative, with feedback loops between innovation development and implementation that continuously refine the innovation’s ability to create sustainable value.

The current research model focuses specifically on examining the mediating role of the ability to create value through social innovation on the relationship between social entrepreneur competencies and sustainability performance. While a direct relationship between social entrepreneur competencies and sustainability performance could theoretically exist, this research deliberately examines the innovation pathway based on several theoretical and practical considerations. First, from the perspective of resource-based theory (Amini et al., 2018), social entrepreneur competencies represent organizational resources that typically need to be operationalized through specific organizational processes and capabilities in order to generate performance outcomes. In this research framework, innovation capability serves as a crucial transformative mechanism that converts entrepreneur competencies into tangible sustainability outcomes. Second, the prior literature in the entrepreneurship field suggests that the impact of entrepreneurial characteristics on performance is often indirect and mediated by strategic actions and organizational capabilities (Karunanithy & Jeyaraman, 2013). Innovation represents one of the primary mechanisms through which entrepreneurial vision and capabilities manifest in organizational outcomes. Third, in the specific context of social entrepreneurship in Thailand, innovation is particularly critical, given resource constraints and complex social challenges. Social innovation serves as the necessary bridge that enables social entrepreneurs to translate their competencies into sustainable solutions for social problems (Ramadani et al., 2022). Finally, this research design choice allows for a more focused examination of the innovation pathway, which has been identified as a critical yet understudied mechanism in social entrepreneurship research (Kostetska & Berezyak, 2014). By concentrating on this specific causal chain, this research provides deeper insights into how social innovation enables sustainability in social enterprises.

2.4. The Theoretical Foundations Underpinning the Research Model

This research is grounded in and extends several interconnected theoretical frameworks that were selected based on their particular relevance to the social entrepreneurship context in Thailand. Transformational leadership theory (Korejan & Shahbazi, 2016) provides the foundation for understanding visionary change leadership in social entrepreneurship. This theory was chosen because its central assumption—that leaders can inspire followers to pursue collective goals beyond self-interest—directly aligns with the mission-driven nature of social enterprises. In the Thai context, where collective cultural values often supersede individualistic approaches, transformational leadership’s emphasis on shared vision makes it especially appropriate for examining how social entrepreneurs mobilize stakeholders around social missions.

Stakeholder theory (Mahajan et al., 2023) underpins the conceptualization of stakeholder collaboration as a key competency. Unlike conventional businesses that primarily focus on shareholder value, social enterprises must balance the interests of multiple stakeholders including beneficiaries, communities, and funders. This research extends stakeholder theory by investigating how collaborative stakeholder engagement catalyzes social innovation processes. Corporate Social Responsibility theory, particularly the pyramid model (Masoud, 2017), informs the understanding of social and environmental responsibility. We extend this theory by examining how the integration of CSR principles into core business activities (rather than as peripheral considerations) enhances innovation capabilities specifically oriented toward social value creation.

Resource-based view theory (Barney, 2001) was selected because its core assumption—that competitive advantage stems from unique, valuable, and difficult-to-imitate resources—helps explain how social entrepreneurs leverage distinctive competencies to create social value. This is especially relevant in the resource-constrained environment of Thai social enterprises, where intangible assets like leadership vision and stakeholder relationships often compensate for limited financial resources. The theory’s focus on internal capabilities makes it appropriate for examining how social entrepreneurs transform their competencies into innovation capabilities despite resource limitations.

Schumpeterian innovation theory (Mehmood et al., 2019) provides the theoretical basis for the examination of social innovation. While conventional applications of this theory focus on market disruption for commercial gain, we extend it to social contexts based on the assumption that innovation processes can be directed toward social value creation. This extension is particularly appropriate for Thai social enterprises, which often need to develop innovative approaches to address complex social issues with limited resources. The theory’s emphasis on entrepreneurial agency aligns with the proactive problem-solving orientation required of social entrepreneurs in Thailand’s developing economy context.

Triple bottom line theory (Farooq et al., 2021) offers the most appropriate framework for measuring sustainability outcomes because it assumes that organizational success should be evaluated across economic, social, and environmental dimensions simultaneously. This multidimensional assumption is perfectly aligned with the hybrid nature of social enterprises, which pursue blended value creation rather than single bottom line objectives. In Thailand, where social enterprises often emerge in response to environmental challenges and social inequities while still needing economic viability, this theoretical approach provides a comprehensive measurement framework that reflects their complex performance objectives.

Dynamic capabilities theory (Vézina et al., 2019) was selected based on its assumption that organizations must continuously reconfigure their resources to address changing environments. This assumption is particularly relevant for Thai social enterprises operating in rapidly evolving social, environmental, and policy contexts. The theory’s focus on adaptation makes it appropriate for understanding how social innovation capabilities enable social enterprises to respond to emerging social challenges while maintaining organizational sustainability amid Thailand’s transitioning economy.

3. Research Framework

This research employs a hierarchical model structure that includes both first-order and second-order variables. Second-order (or higher-order) constructs represent abstract latent variables that are not directly measured but are instead manifested through multiple first-order constructs (Champahom et al., 2025). In this study, social entrepreneurship competencies function as a second-order construct that is manifested through three first-order constructs: Visionary Leadership for Change, Corporate Social Responsibility, and stakeholder collaboration. Similarly, the ability to create value through social innovation is conceptualized as a second-order construct manifested through three first-order constructs: process innovation, product innovation, and marketing innovation. Performance Sustainability is likewise a second-order construct, with economic, social, and environmental performance as its first-order components.

This hierarchical approach offers several advantages. First, it allows for the modeling of complex theoretical concepts that have multiple dimensions or facets. Second, it provides a more parsimonious representation of the relationships between major theoretical constructs while still accounting for their multidimensional natures. Third, it enables the examination of how these broader constructs relate to each other while acknowledging their distinct components. This approach is particularly appropriate for studying social entrepreneurship, where key concepts like entrepreneurial competencies and innovation capabilities are inherently multidimensional.

The second-order constructs in this research are specifically modeled as reflective–reflective hierarchical constructs (Qureshi et al., in press). In this type of hierarchical model, both the relationships between the second-order construct and its first-order constructs (higher-order relationships) and the relationships between the first-order constructs and their indicators (lower-order relationships) are reflective in nature. This means that the second-order constructs are manifested by their first-order constructs, and that changes in the second-order constructs are reflected in changes in all their first-order components.

For social entrepreneurship competencies, this reflective–reflective structure implies that the three first-order constructs (Visionary Leadership for Change, Corporate Social Responsibility, and stakeholder collaboration) are reflective manifestations of the overall competency construct. Similarly, the three innovation dimensions (process, product, and marketing innovations) are reflective indicators of the higher-order ability to create value through social innovation. Performance Sustainability is likewise reflectively measured by economic, social, and environmental performance dimensions.

In terms of operationalization, this reflective–reflective approach was implemented through a two-stage approach in the structural equation modeling analysis. First, the measurement models for each first-order construct were established and validated through confirmatory factor analysis. Then, the factor scores of the first-order constructs were used as reflective indicators of their respective second-order constructs in the structural model. This approach allowed us to test the relationships between the second-order constructs while accounting for their multidimensional natures. The choice of the reflective–reflective model was based on the theoretical understanding that these competencies, innovation capabilities, and performance dimensions represent manifestations of their respective higher-order constructs rather than formative components that would create or cause the higher-order construct (Ruiz et al., 2008).

3.1. Antecedent Variable Consists of Three Variables

Social entrepreneurship competency (CSE) encompasses three key areas. Firstly, it involves the competencies necessary for social entrepreneurship, serving as internal support within an organization to facilitate the creation of value through innovation. The essential qualities of this include the following:

- Visionary Leadership for Change (VC): This refers to the capacity to use ideological influence to articulate a vision to subordinates, motivating them to undertake work that benefits the broader community. This entails inspiring others and effectively communicating the necessity for change. It also involves fostering discussions on environmental analysis within the business context, enabling subordinates to generate operational ideas aligned with societal and environmental responsibilities. Ultimately, this fosters innovation and sustainability (Mostovicz et al., 2009).

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): This entails conducting business activities with a focus on social responsibility, prioritizing social awareness and the relationship between marketing efforts and societal needs. It involves addressing social issues through initiatives aimed at promoting behavioral changes in areas such as the environment and public health. The literature suggests that such initiatives positively impact organizational reputation and stakeholder perceptions of value (Mostovicz et al., 2009).

- Stakeholder collaboration (SK): This refers to the ability to engage with downstream customers, communities, and other stakeholders to establish mutually beneficial relationships. Effective collaboration involves meeting customer needs, coordinating efforts with stakeholders to build trust and acceptance, and fostering ongoing cooperative activities. Integration with stakeholders facilitates swift responses to market demands and operational enhancements, thereby enhancing competitiveness on a global scale.

3.2. Mediator Variables Encompass Capacity to Generate Value Through Innovation (IN) Across Three Main Domains

- Creating value through process innovation (IN process) involves implementing fresh ideas, methods, or procedures resulting in significantly enhanced efficiency and effectiveness within production processes and overall operations. Most process innovations center on quality control and continual the enhancement of production efficiency and operations, encompassing activities or processes within organizational systems including inputs, processes, and outputs. This concept entails reducing production costs, minimizing production time, and refining production processes, with an emphasis on addressing social and environmental concerns (Dubey et al., 2015).

- Creating value through product innovation (IN product) entails the development and introduction of new products, whether through technological advancements or enhancing existing products to bolster their quality and efficiency. Product innovation is integral to business success and may involve delivering high-quality, unique products that are challenging to replicate. This aspect also emphasizes addressing social and environmental considerations (C. L. Wang & Ahmed, 2004).

- Creating value through marketing innovation (IN mk) involves enhancing the business’s marketing mix to better appeal to target customers and identifying suitable products or services for specific markets. Marketing innovation seeks to identify new markets with potential and novel approaches for product and service delivery. It encompasses selecting markets to target customers more effectively, incorporating new market dynamics, adopting new pricing models, modifying distribution channels, and devising innovative marketing strategies, all with an emphasis on addressing social and environmental concerns (Lin et al., 2010).

3.3. Variables Referring to Performance Sustainability (PS) Comprise Three Aspects

- Economic performance (EP) denotes the outcomes in economic terms resulting from an organization’s operations. This includes increases in market share, sales, revenue, and profits (Dubey et al., 2015).

- Social performance (SOP) pertains to the social outcomes arising from an organization’s operations. This involves considering employees’ commitment to the organization and fostering positive relationships with community organizations and society (Dubey et al., 2015).

- Environmental performance (ENP) signifies the outcomes related to environmental factors resulting from an organization’s operations. This encompasses the responsible utilization of natural resources in operations and efforts to reduce the environmental impact of operating processes, including obtaining certifications or awards related to environmental management (Dubey et al., 2015).

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Population and Sample Group

The population used in this study was social entrepreneurs, including social enterprises and social entrepreneurship groups that were registered as social enterprises according to the Social Enterprise Promotion Act of 2019, totaling 304 businesses according to information from March 2023. The calculation of sample size (n) from the mentioned groups (304 businesses) was determined using the criteria for consideration in conducting structural equation modeling (SEM). Based on Jackson’s criteria (2001), the sample size should be 10–20 times that of the observable variables. This research had 10 observable variables, so the sample size needed to equal l was 100–200. This research comprised a total of 200 samples used in the actual data analysis. Therefore, the number of samples in this research met the requirements. In addition, Kline (2015)’s criteria state that the sample size for appropriate structural equation modeling analysis should be at least 200 samples or more. The social enterprises were key informants who provided the information.

4.2. Data Collection

This research used a questionnaire to collect data by post. In general, the response rate for postal questionnaires, if not requested, approximates 20 percent. However, there may have been limitations on the ability to provide good representative data for this research due to the small response rate, as the population was 304 businesses. The respondents were able to answer the questionnaire and send it back by post or scan a QR code on their questionnaire and complete them online in order to reduce the risk of not receiving a response from the sample. After collecting the data, it was found that there were actually 200 samples that could be used for data analysis. Therefore, the number of samples in this research met the requirements and was consistent with the criteria of Kline (2015), who stated that the appropriate sample size for use in structural equation modeling analysis should be at least 200 samples. In addition, after checking their content completeness, our sample accounted for 65.78 percent of the population. This was in accordance with the acceptable criteria for a postal response rate of at least 20 percent. The collected sample data details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details about sample group.

4.3. Measurement Scale Development and Validation

The measurement scales used in this study were developed based on the existing literature and adapted to the social entrepreneurship context in Thailand. Content validity was established through expert assessment, with three subject matter experts evaluating the items. The index of item–objective congruence (IOC) values ranged from 0.838 to 0.937, exceeding the threshold of 0.80, which indicated that the measurement items adequately represented the constructs being measured (Kline, 2015).

The reliability of the measurement scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. A pilot test was conducted with 30 social enterprises not registered under the Social Enterprise Promotion Act of 2019 to ensure that the target population would not be contaminated. The reliability analysis yielded Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.838 to 0.924 for all construct measures, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70 (Saher, 2020). This confirmed that the measurement scales demonstrated adequate internal consistency and could be reliably used for data collection from the main sample. The details of Cronbach’s alpha values for each construct dimension are presented in Table 2 and Table A1.

Table 2.

Details of coefficients’ Cronbach’s alpha values.

4.4. Data Analysis

In the initial phase of data analysis, various descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, means, and standard deviations, were employed to examine factors related to social entrepreneurship competencies, the ability to generate value through innovation, and sustainability in social business operations. The subsequent hypothesis testing involved inferential statistics, employing confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM). Several descriptive statistical values, such as χ2/df, CFI, TLI, RMR, and RMSEA, were utilized in this analysis. The assessment of statistical values revealed specific criteria for model fit: a relative Chi-Square ratio index (χ2/df) below 3; the Comparative Fit Index (CFI); Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) values exceeding 0.90; and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) below 0.08 (Kline, 2015). Based on these criteria, all four measurement models were consistent with the empirical data. Therefore, it could be concluded that all four latent variables used in the study exhibited construct validity and could be appropriately used for structural equation modeling analysis. The AMOS software was used for conducting the subsequent hypothesis testing.

5. Results

5.1. Data Analysis Results for Opinion Level

From the sample group’s overall opinion of their ability to create value through social innovation of social entrepreneurs in Thailand, it can be seen the antecedent factors and effects of the ability to create value through social innovation are at the highest level (M = 4.21, S.D. = 0.57). The overall mean of the antecedent factors of the ability to create value through social innovation is also at the highest level (M = 4.38, S.D. = 0.43), and the overall mean of the outcomes of the ability to create value through social innovation, including sustainable performance, is at a high level (M = 4.07, S.D. = 0.55), as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Data analysis for opinion levels on ability to create value through social innovation. Antecedent factors and effects of ability to create value through social innovation.

The discriminant validity of the constructs was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which compares the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) with the correlation between constructs. As shown in Table A2, the square root of the AVE for each construct (displayed in bold on the diagonal) exceeds its correlation with other constructs, confirming adequate discriminant validity. Additionally, all the AVE values exceeded 0.5, ranging from 0.685 to 0.814, indicating that each construct explained more than 50% of the variance in its indicators. The correlation coefficients between the constructs ranged from 0.349 to 0.702, demonstrating that the constructs were sufficiently distinct from one another while still maintaining their theoretically expected relationships. These results confirm that the measurement model demonstrates both convergent and discriminant validity, providing a solid foundation for structural model analysis (Thotongkam et al., 2023).

5.2. The Overall Test Results of the Model for the Ability to Create Value Through Innovation

After confirming preliminary agreement by analyzing the relationships and testing the data distribution, the relationship between every pair of variables had a correlation coefficient between 0.508 and 0.802, with statistical significance at the 0.01 level. The coefficients between the variables were not more than 0.9 and were considered to be correlated at an acceptable level (Field, 2005). For data distribution, considering skewness and kurtosis, the results showed a normal curve for every observable variable, with a skewness value between −0.573 and −0.066, which is not more than +3, and a kurtosis value between −0.909 and 0.481, which is not more than ±10 (Kline, 2015).

The factor analysis results for the social entrepreneurship competencies consisted of three factors, including (1) visionary change leadership; (2) being environmentally and socially responsible; (3) collaboration with stakeholders. The indices used to test consistency and the model’s good fit with the empirical data were as follows: Chi-Square = 168.655; df = 86; χ2/df =1.961; RMASE = 0.069; SRMR = 0.026; CFI = 0.948; and TLI = 0.936. These indicate that the measurement model of social entrepreneurship competencies is consistent with the empirical data and can be used to measure the social entrepreneurship competencies of social enterprises in Thailand.

The factor analysis results for the ability to create value through social innovation consist of three factors: (1) creating value through process innovation; (2) creating value through product innovation; (3) creating value through marketing innovation. The indices used for examining the consistency and the model’s good-of-fit with the empirical data were as follows: Chi-Square = 92.290; df = 48; χ2/df = 1.923; RMASE = 0.068; SRMR = 0.026; CFI = 0.953; and TLI = 0.935. These indicate that the model’s measurement of the ability to create value through social innovation of social entrepreneurship in Thailand is consistent with the empirical data and can be used to measure the ability to create value through social innovation.

The factor analysis results for sustainability in social business operations consist of three factors: (1) economic performance; (2) social performance; (3) environmental performance. The indices used to measure the consistency and model good-of-fit with the empirical data were as follows: Chi-Square = 177.588; df = 86; χ2/df = 2.065; RMASE = 0.073; SRMR = 0.030; CFI = 0.934; TLI = 0.920. These indicate that the model’s measurement of sustainability in social entrepreneurs is consistent with the empirical data and can be used to measure sustainability in social entrepreneurship in Thailand, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Factor analysis results of variables.

Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 testing was conducted to examine the goodness-of-fit between the model variance matrix and the empirical data and to study the influence of the ability to create value through social innovation on the sustainability of social entrepreneurship in Thailand. The results are shown in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

The index values of the validity of the structural equation model of the overall ability to create value through social innovation.

Table 6.

Statistical results of structural equation model analysis of overall ability to create value through innovation for social entrepreneurs in Thailand.

The results of the structural equation model analysis in Table 5 reveal insights into the ability to create value through social innovation. To assess the model’s fit with the empirical data, various indices were considered in line with Hypothesis 1. These indices included a Chi-Square value of 39.893 with 22 degrees of freedom (df), a relative Chi-Square ratio index (χ2/df) of 1.813 (below 3), a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 0.983, a Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) of 0.973 (exceeding 0.95, as recommended by Hair et al., 2010), a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of 0.064 (below 0.08), and a root mean square residual (RMR) of 0.009 (below 0.05, as suggested by Hair et al., 2010). These statistical values collectively indicate that the structural equation model for the ability to create value through innovation aligns well with the empirical data.

From Table 6 and Figure 2, the estimations of the parameters for the factor loadings of the social entrepreneurship competencies variables are all statistically significant at the 0.01 level, meaning that all three indicators of social entrepreneurship competencies are important factors in explaining the social entrepreneurship competencies that affect the ability to create value through social innovation. The most important factor is visionary change leadership (β = 0.860), followed by being environmentally and socially responsible (β = 0.828) and collaboration with stakeholders (β = 0.796). As for the factor loading of the variable “ability to create value through social innovation”, all the items are statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The most important factor was creating value through marketing innovation (β = 0.969), followed by creating value through process innovation (β = 0.933) and creating value through product innovation (β = 0.908), and the factor loadings for the Performance Sustainability of social innovation were also statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The most important factor was environmental performance (β = 0.793), followed by social performance (β = 0.753) and economic performance (β = 0.575).

Figure 2.

The structural equation model of the overall ability to create value through innovation of social entrepreneurs in Thailand (Chi-Square = 39.893; df = 22; χ2/df = 1.813; RMSEA = 0.064; RMR = 0.009; CFI = 0.983; TLI = 0.973). The structural equation model illustrated in the figure demonstrates the relationships between three key latent constructs and their respective observed variables in the social entrepreneurship context. The social entrepreneurship competencies (CSEs) are a higher-order construct measured through three observed variables: visionary change leadership (TotalVC), environmental and social responsibility (Total CSR), and collaboration with stakeholders (Total SK). The second latent construct, the ability to create value through social innovation (IN), is measured by creating value through process innovation (TotalINprocess), creating value through product innovation (TotalINproduct), and creating value through marketing innovation (TotalINmk). The third latent construct, Performance Sustainability (PS), is assessed through economic performance (TotalEP), social performance (TotalSOP), and environmental performance (TotalENP). The model displays standardized path coefficients on the arrows connecting the latent variables, with error terms represented by circles (e1–e16). The values on the paths between the latent and observed variables indicate factor loadings, while the values between the latent variables reflect the strength of causal relationships. This structural model provides empirical validation of the theoretical framework proposing that social entrepreneur competencies influence innovation capabilities, which in turn affect sustainability outcomes.

The effect size values between the variables of social entrepreneur competencies influence the ability to create value through social innovation with a coefficient value of DE = 0.972 (p < 0.01); external supporting factors influence the ability to create value through social innovation with a coefficient value of DE = 0.707 (p < 0.01); and the ability to create value through social innovation affects Social Performance Sustainability with a coefficient value of DE = 0.687 (p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 are accepted, as shown in the details of Table 7.

Table 7.

Summarized results of research hypothesis testing.

6. Discussion

This study examined how social entrepreneur competencies influence the ability to create value through social innovation and how this ability subsequently affects sustainability outcomes in Thai social enterprises. Our findings provide several important insights that both support and extend previous research in this domain.

6.1. Social Entrepreneur Competencies and Value Creation Through Social Innovation

The results confirm Hypothesis 1, demonstrating that social entrepreneur competencies positively influence the ability to create value through social innovation (β = 0.972, p < 0.01). This strong relationship aligns with previous research by Fontana and Musa (2017), who found that entrepreneurial leadership qualities significantly affect innovation outcomes in social ventures. However, the magnitude of the relationship in this study is notably stronger than in previous studies, which have typically reported moderate relationships (e.g., β = 0.45 to 0.65) (Li et al., 2020). This difference may reflect the particularly critical role of entrepreneurial competencies in the resource-constrained environment of Thai social enterprises. Among the three dimensions of social entrepreneur competencies, visionary change leadership emerged as the strongest indicator (β = 0.860), followed by environmental and social responsibility (β = 0.828) and stakeholder collaboration (β = 0.796). This finding extends research by Pless et al. (2021), who identified visionary leadership as a key driver of social innovation but did not examine its relative importance compared to other competencies. The strong loading of environmentally and socially responsible orientation contradicts findings by Segarra-Oña et al. (2017), who found this dimension to be less influential in Western contexts, but supports research by Sharma (2013) highlighting the importance of social responsibility in Asian business contexts.

6.2. Innovation Capabilities and Sustainability Outcomes

Hypothesis 2 was also supported, with the ability to create value through social innovation having a significant positive effect on sustainability outcomes (β = 0.707, p < 0.01). This finding corroborates research by Vézina et al. (2019), who found that innovation capabilities contribute significantly to social enterprise sustainability. However, our research extends this work by specifically examining the relative contribution of different innovation types.

Marketing innovation emerged as the strongest indicator of innovation capability (β = 0.969), followed by process innovation (β = 0.933) and product innovation (β = 0.908). This finding contrasts with studies in commercial entrepreneurship contexts, where product innovation is typically the strongest predictor of performance (Austin et al., 2012). The primacy of marketing innovation in this study may reflect the particular importance of effectively communicating social values to diverse stakeholders in social enterprises, as noted by Estrin et al. (2016). It also suggests that Thai social enterprises may focus more on innovative approaches to reaching and engaging beneficiaries and customers than on developing entirely new products or services.

6.3. Sustainability Outcomes in Social Enterprises and Theoretical and Contextual Implications

In examining sustainability outcomes, environmental performance showed the strongest factor loading (β = 0.790), followed by social performance (β = 0.753) and economic performance (β = 0.668). This finding diverges from some previous studies in Western contexts that have found social performance to be the dominant dimension in social enterprises (Defourny et al., 2011). The prominence of environmental performance in our study may reflect Thailand’s particular environmental challenges and the growing emphasis on environmental sustainability in national policies (Z. Wang & Zhou, 2020).

The strong mediating role of innovation capabilities in the relationship between social entrepreneur competencies and sustainability outcomes supports dynamic capabilities theory (Ince & Hahn, 2020), which suggests that organizations must develop capabilities to reconfigure resources in response to changing environments. In the context of Thai social enterprises, innovation capabilities appear to be critical mechanisms through which entrepreneurial competencies are translated into sustainable performance.

The findings also extend resource-based theory by demonstrating how intangible resources, particularly entrepreneurial competencies, can be leveraged to create competitive advantages in social enterprises. This supports arguments by Kong and Kong (2010) that resource constraints in social enterprises often lead to more innovative approaches to value creation.

7. Conclusions

Studying the level of factors related to social entrepreneurship competencies and the ability to create value that affects sustainability through social innovation in social entrepreneurship in Thailand, our results revealed that the first factor most affecting the ability to create value through social innovation is social entrepreneur competencies, which are being environmentally and socially responsible, having visionary change leadership, and having the ability to collaborate with stakeholders. At the operational level, regarding the ability to create value through social innovation, creating value through marketing innovation is the most important, followed by product innovation and process innovation. The factors resulting from the ability to create value through social innovation include Social Performance Sustainability. The areas with the highest opinion levels were social, environmental, and economic performances. With the overall sample group’s opinions on their ability to create value through social innovation in social entrepreneurship in Thailand, academics may use these results as a starting model to expand the study’s scope in terms of the ability to create value through social innovation, considering factors such as the various activities organizations should carry out related to social activities or environmental management. In addition, in broader areas, such as integrating the relationships of various variables upstream and downstream of organizations, these research results provide a measurement model and a cause-and-effect model of managing the ability to create value through social innovation in Thai social entrepreneurship that is consistent with the real context of Thai society.

From the study of effect size between variables, it can be explained that social entrepreneur competencies comprise visionary change leadership, being environmentally and socially responsible, and collaboration with stakeholders. Entrepreneurs must have an interest in, awareness of, and appreciation of the value of operating businesses while serving society. They must also have the ability in both science and art to create a vision, be able to stimulate motivation, have a positive influence on thoughts and behavior among followers, and have a sense of social responsibility.

These research findings allowed us to construct a model verified through research procedures as being appropriate for the context of Thai society. Thus, these results can be used as guidelines for developing the ability to create value through social innovation in an integrative manner, as follows: (1) Entrepreneurs can use them as analytical data to plan their operational design and determine guidelines for improving and developing the ability to create value through social innovation by allowing personnel to take part in this innovation seriously, and take social responsibility through social innovation by creating value through process innovation, product innovation, and marketing innovation, leading to sustainable performances. (2) The obtained information can be used as a guideline for changing the paradigm of social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurs should be aware of creating social value, striving to develop the ability to create value for their business through social innovation and value creation. (3) Social entrepreneurs and government agencies can use the data to clearly create a personnel development plan in terms of training and developing operational skills in order to increase knowledge and understanding about creating value through social innovation so that entrepreneurship can keep up with the rapidly changing environment.

These research findings have significant policy implications that can guide the development of a more robust social enterprise ecosystem in Thailand and similar developing economies. Policymakers should consider establishing dedicated funding mechanisms specifically targeting social enterprises with strong innovation capabilities, particularly those focused on environmental sustainability, given their strong correlation with overall sustainability outcomes. The Thai government should implement tiered tax incentives that reward social enterprises based on measurable environmental and social impact metrics, thereby encouraging the development of more sophisticated impact measurement systems. Additionally, policy initiatives should focus on strengthening the entrepreneurial competencies identified as crucial in this study. This could include establishing specialized training programs that emphasize visionary leadership development and stakeholder collaboration skills for emerging social entrepreneurs. Government agencies should create regional innovation hubs that facilitate knowledge exchange between social enterprises, traditional businesses, and academic institutions to foster marketing innovation capabilities, which emerged as the strongest indicator of overall innovation performance. Educational institutions should be incentivized through policy to incorporate social entrepreneurship modules into business curricula, with particular emphasis on the development of competencies in environmental responsibility and stakeholder engagement. Finally, the Social Enterprise Promotion Office should establish a formal mentorship program pairing established social entrepreneurs with emerging ventures in order to transfer knowledge about successful innovation practices in the Thai context.

This research has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevents the examination of how relationships between variables might evolve over time, particularly in a rapidly changing business environment. A longitudinal approach would provide deeper insights into the causal relationships between entrepreneurial competencies, innovation, and sustainability outcomes. Second, the study focused solely on registered social enterprises, potentially overlooking nascent or informal social entrepreneurship initiatives that might exhibit different patterns of innovation and sustainability. Third, the geographical concentration within Thailand limits the generalizability of these findings to other contexts with different cultural, economic, and institutional arrangements. Had these limitations been addressed, the research might have revealed additional nuances in how social innovation capabilities develop across different types of social enterprises and cultural contexts.

For future research, there should be studies on other factors that potentially influence the ability to create value through social innovation, and their samples may be selected from other associations related to social entrepreneurship or may specify a business sector that more clearly enables social entrepreneurship development. Additionally, comparative studies across different countries in Southeast Asia would enhance our understanding of how institutional contexts shape social innovation processes and outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.W. and N.L.; methodology, N.L.; software, N.W.; validation, A.T., W.W. and T.C.; formal analysis, N.L.; investigation, A.T.; data curation, N.W.; writing—original draft preparation, N.W. and N.L.; writing—review and editing, T.C.; visualization, N.L.; supervision, W.W.; project administration, N.W.; funding acquisition, N.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Rajamangala University of Technology Isan, grant number NKR2566INCO64.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, Rajamangala University of Technology Isan (protocol code HEC-01-66-041; date of approval 18 May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request due to restrictions (e.g., privacy, legal or ethical reasons).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire items.

Table A1.

Questionnaire items.

| Item | Description | Cronbach’s Alpha | M | S.D. | Factor Loading | SE. | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Entrepreneur Competencies | 0.547 | 0.947 | ||||||

| Visionary change leadership | 0.908 | 0.539 | 0.852 | |||||

| VC1 | Leaders possess knowledge, capability, and appropriate understanding of global, economic, social, and environmental changes. | 4.42 | 0.652 | 0.789 | 0.377 | |||

| VC2 | Leaders establish clear vision and goals for environmental and social operations. | d | 4.47 | 0.649 | 0.864 | 0.254 | ||

| VC3 | Leaders promote staff participation in organizational environmental decision-making. | 4.35 | 0.685 | 0.75 | 0.438 | |||

| VC4 | Leaders support the establishment of operational guidelines for social and environmental responsibility. | 4.26 | 0.731 | 0.594 | 0.647 | |||

| VC5 | Leaders play a crucial role in driving organizational environmental strategies that align with sustainable marketing. | 4.4 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.59 | |||

| Environmental and social responsibility | 0.912 | 0.608 | 0.884 | |||||

| CSR1 | The organization continuously conducts activities that reflect environmental and social responsibility. | 4.45 | 0.64 | 0.768 | 0.41 | |||

| CSR2 | The organization prioritizes social awareness and expectations regarding business operations. | 4.46 | 0.6 | 0.859 | 0.262 | |||

| CSR3 | The organization focuses on solving social problems such as health, environment, and community behavior. | 4.51 | 0.634 | 0.841 | 0.293 | |||

| CSR4 | The organization has concrete activities that integrate marketing with social responsibility. | 4.59 | 0.586 | 0.8 | 0.36 | |||

| CSR5 | The organization’s social responsibility activities enhance its reputation and value. | 4.49 | 0.626 | 0.605 | 0.634 | |||

| Collaboration with stakeholders | 0.907 | 0.493 | 0.828 | |||||

| SK1 | You believe stakeholder participation is essential to the success of organizational activities. | 4.17 | 0.643 | 0.736 | 0.458 | |||

| SK2 | You believe stakeholder participation promotes the development of products/services that meet needs. | 4.21 | 0.636 | 0.711 | 0.494 | |||

| SK3 | You believe the ability to manage stakeholders is a crucial qualification for social entrepreneurs. | 4.25 | 0.7 | 0.718 | 0.484 | |||

| SK4 | The organization can arrange activities that build continuous relationships and cooperation with stakeholders. | 4.24 | 0.709 | 0.758 | 0.425 | |||

| SK5 | The organization can respond to stakeholder needs quickly and efficiently. | 4.59 | 0.56 | 0.573 | 0.672 | |||

| Ability to create values through social innovation | 0.56 | 0.938 | ||||||

| Creating value through process innovation | 0.905 | 0.531 | 0.819 | |||||

| Iprocess1 | Your organization’s production processes continuously incorporate new concepts to reduce costs. | 4.35 | 0.706 | 0.734 | 0.461 | |||

| Iprocess2 | Your organization has improved work processes to be more efficient and faster. | 4.22 | 0.703 | 0.758 | 0.425 | |||

| Iprocess3 | Quality control processes in the organization have been improved using new innovations that are environmentally conscious. | 3.99 | 0.808 | 0.703 | 0.506 | |||

| Iprocess4 | Your organization has improved production processes to comply with social and environmental standards. | 4.19 | 0.79 | 0.719 | 0.483 | |||

| Creating value through product innovation | 0.903 | 0.601 | 0.856 | |||||

| Iproduct1 | Your organization continuously develops new products of higher quality than competitors. | 4.31 | 0.696 | 0.635 | 0.597 | |||

| Iproduct2 | The organization’s products have unique characteristics that are difficult to imitate. | 4.14 | 0.73 | 0.828 | 0.314 | |||