Abstract

Despite evidence that internal marketing influences key employees and customer outcomes, its role in shaping employee agility, creativity, and engagement remains underexplored, limiting organizations’ ability to develop a workforce that sustains competitiveness in dynamic environments. While previous literature has addressed individual relationships between internal marketing, employee creativity, agility, engagement, and satisfaction, we propose a structural model to test the proposed effects and provide a holistic understanding of how internal marketing interacts with employee creativity and other concepts. Covariance-based structural equation modeling was used to test relationships. The results confirm a significant positive impact of internal marketing on employee agility and engagement. While we did not find a direct impact on creativity, we identified an indirect impact on employee creativity via agility. Additionally, analysis showed a positive impact of creativity on satisfaction, highlighting the importance of a creative work environment in enhancing overall employee satisfaction. The study demonstrates that a well-structured IM strategy can set a company apart by fostering a workforce that is more agile, creative, engaged, and committed to success.

1. Introduction

Prior studies highlight the importance of creativity and employee agility for enabling rapid responses to market shifts and for generating novel solutions (Shalley et al., 2004; Eldor & Harpaz, 2016; Bakker et al., 2020), yet much less is known about how organizational practices—particularly internal marketing (IM)—shape these employee capabilities. Despite growing recognition that structured IM can support a more proactive and engaged workforce (Anderson et al., 2014; Bakker et al., 2020), the interplay between IM, creativity, and agility has rarely been empirically examined.

According to Gwinji et al. (2020), IM is an important factor that positively influences a company’s ability to secure a competitive advantage in the marketplace. IM practices empower employees to develop a sense of belonging, which motivates them to give their best to achieve organizational goals. Furthermore, Brown et al. (2025) emphasize that IM facilitates employee engagement with customer-oriented goals, creating value that contributes to a sustainable competitive advantage. Moreover, recent evidence shows that workplace well-being, employee development, and retention initiatives jointly enhance employee engagement, which in turn leads to higher overall satisfaction (Sypniewska et al., 2023).

The importance of employee agility to organizational success and securing a competitive advantage is widely recognized (Morgan, 2004; Jager et al., 2022). Harnessing employee agility through effective talent management practices provides a viable way to navigate the complex and uncertain business landscape, enabling rapid adaptation to environmental changes and promoting more effective responses. An agile, creative, engaged, and satisfied workforce enables companies to adapt to change, improve service quality, and achieve long-term success.

Innovation driven by creative employees is crucial to achieving a competitive advantage and organizational success (e.g., Hughes et al., 2018; Anderson et al., 2014). Employee creativity has been proven to be crucial in achieving and maintaining a competitive advantage (Andleeb et al., 2019; Gjurašić & Marković, 2017). Several studies have shown that creativity has a positive impact on employee satisfaction (Shalley et al., 2004; Hassan et al., 2013). Creativity and innovation are also closely linked to employee engagement in the workplace, as engaged employees are enthusiastic about their tasks and responsibilities, which in turn encourages creative thinking (Nawaz et al., 2014).

IM impacts employees and their behavior and should be related to employee creativity and agility. By encouraging interaction between employees and employers, IM promotes the exchange of ideas, experiences and perspectives, which can increase employee creativity and agility (Gjurašić & Marković, 2017). While further research is needed to fully understand the interplay between IM and employee creativity and agility, the practices associated with IM offer several opportunities to foster a culture of innovation in the workplace.

Studies (Ferdous & Polonsky, 2014; Y. Huang & Rundle-Thiele, 2015; Y.-T. Huang et al., 2019; Kadic-Maglajlic et al., 2018; Sarker & Ashrafi, 2018; Nemteanu & Dabija, 2021) have confirmed the positive impact of IM on employee satisfaction. In addition, several authors (Ahmed et al., 2003; Caldwell et al., 2015; Ali & Ahmad, 2017) have investigated the impact of employee satisfaction on organizational performance and competitive advantage. However, there remains a lack of research examining the impact of IM on employee agility and creativity. Although IM strategies can improve employee motivation and engagement, their role in fostering adaptability and innovative thinking is under-researched. Understanding these relationships is important as organizations operating in a dynamic environment rely on agile and creative employees to drive innovation and maintain their competitiveness. This knowledge can provide valuable insights into how to use IM to develop a more responsive and innovative workforce.

In this study, we also address a gap concerning the interaction between IM activities and employee agility, creativity, and engagement. Studies, including empirical research up to now, have examined the impact of IM on employee engagement and job satisfaction (Sarangal & Nargotra, 2017), (Dlačić et al., 2018); (Črnjar et al., 2020), and Brunetto et al.’s (2012) empirical study confirms that engagement positively affects employee satisfaction. However, there is a gap in focusing on the impact of employee creativity and agility on their engagement.

To address this research gap, the present study aims to investigate the impact of IM on employee creativity and engagement, while examining the relationship between employee agility, satisfaction, and engagement within the organizational context of companies in Slovenia. The Slovenian organizational environment offers a representative context for studying IM practices in small EU economies, with its innovative and competitive landscape enabling the examination of employee creativity and related outcomes. Research on selected topics is also relevant for post-transitional economies, such as Slovenia, because organizations must continually adapt their workforces to compete in increasingly dynamic, innovation-driven markets. Exploring and measuring IM in different cultural contexts is crucial in order to understand whether its impact on employees remains the same or varies significantly across cultural settings, as the concept of IM can vary significantly across different industries, research contexts, and cultural settings, which emphasizes the importance of context-specific measurements of IM (Lings & Greenley, 2005).

This study also draws on contemporary theoretical approaches that emphasize the integration of micro- and macro-level perspectives, which are essential for understanding organizational phenomena in contextually rich settings (Homer & Lim, 2024).

The paper is organized into several main sections. It begins with an introduction, followed by a presentation of the theoretical background and the development of hypotheses. The methodology used is then outlined, followed by the presentation of the results. The paper concludes with a discussion of the findings, as well as theoretical and empirical implications. In addition, the conclusion section addresses the study’s limitations and provides suggestions for further research.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Internal Marketing

IM integrates marketing philosophy with human resource management practices to enhance performance in the external market (Paul & Sahadev, 2018). IM seeks to inspire, retain, and attract employees to accomplish business objectives. This can be accomplished by comprehending employees’ emotional and intellectual needs, providing tailored solutions, and prioritizing the establishment of long-term relationships (Roberts-Lombard, 2010). Rafiq and Ahmed (2000) define IM as a strategy for managing organizational change, addressing resistance, and offering the initial comprehensive definition as “a planned effort using a (1) marketing-like approach to (2) motivate employees, targeting on delivering (3) customer satisfaction and (4) achieving organizational objectives through (5) inter-functional coordination.”

Researchers have examined the concept of IM from both strategic and functional perspectives. From a strategic standpoint, IM is defined as a holistic approach for the entire company, based on treating employees as internal customers. This approach to IM encompasses numerous managerial activities aimed at motivating employees to become customer-oriented, thereby achieving better market success (Berry et al., 1976; Gummesson, 2000; Lings & Greenley, 2005). From a functional perspective, IM is defined as an organizational activity that utilizes marketing and human resources approaches to achieve the company’s set objectives. In the recent literature, IM is presented as a set of functional activities that provide top managers with tools to shape employee behavior and achieve desired behavioral outcomes (Lings & Greenley, 2005). Within this functional framework, the design of jobs that involve employees in a manner that enhances market performance is advocated (Lings & Greenley, 2005; Boukis & Gounaris, 2014). These highlights include treating employees as internal customers and using marketing principles to engage them in achieving goals. Inter-functional coordination fosters collaboration for shared objectives. Implementing IM strategies enhances satisfaction, engagement, productivity, and customer experiences. Prioritizing employee needs generates value through support and reciprocity (Papasolomou & Vrontis, 2006).

2.2. Employee Agility

Companies must continuously adapt, a goal that can be achieved through fostering agility. Employee agility has become an important topic in terms of organizational success and gaining competitive advantages (Morgan, 2004; Jager et al., 2022). It refers to employees’ ability not only to respond adaptively to changes but also to proactively anticipate and address them (Chonko & Jones, 2005). Thus, agility is an important factor for ensuring success and maintaining a competitive edge. The level of agility within an organization depends on employees’ initiative, which includes their skills, knowledge, and access to information (Salmen & Festing, 2022).

IM practices that focus on employee care and development and utilize technology for better communication can enhance employee agility. Studies have shown that such practices foster an environment that encourages innovation and adaptability. By valuing employee input and engagement, IM can lead to greater workforce agility and increased innovation (Sackey et al., 2025).

According to Ortiz Alvarado and Guerra Leal (2022), integrated management (IM) enhances employee agility by fostering effective communication, promoting emotional well-being, and empowering staff. These factors are essential for helping employees quickly adapt to changes and align their efforts with organizational objectives during challenging times. However, the study did not empirically verify these relationships, leaving it unclear how IM truly promotes agility in practice. Sackey et al. (2025) provide empirical evidence of a positive relationship between IM orientation and employee workforce agility, although their research is limited to the tourism sector. This limitation means that the findings may not be easily applicable to other sectors, where work processes, employee expectations, and organizational structures can differ significantly. Organizations that implement IM strategies are better positioned to prepare for crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, when agility is crucial for adapting to new work environments (Ortiz Alvarado & Guerra Leal, 2022). Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H1.

Internal marketing positively influences employee agility.

2.3. Employee Creativity

Employee creativity is a concept related to IM, especially for achieving and maintaining a competitive advantage. Creative employees can improve service quality, increase efficiency, and ensure long-term survival. Understanding and utilizing employee creativity within IM strategies is a way to succeed in dynamic market conditions (Andleeb et al., 2019; Gjurašić & Marković, 2017). According to Anderson et al. (2014), creativity involves the generation of ideas that facilitate the development, acceptance, and implementation of new concepts (Shalley et al., 2004; Yuan & Woodman, 2010), which ultimately contributes to improved service quality.

IM can enhance employee creativity by fostering an environment that encourages communication, trust, and innovation (Gursoy et al., 2018). Providing training and development opportunities equips employees with the skills needed to generate and implement new ideas. This approach can lead to increased employee creativity and job satisfaction, positively affecting organizational performance (Lin, 2007; Gounaris et al., 2010; Rezvani et al., 2016).

According to social exchange theory, it enhances employee performance when organizations support their employees. Research by Hassan et al. (2013) indicates that employees who receive training and feel empowered perceive that the organization cares about their well-being. This support fosters employee engagement, ultimately contributing to increased creativity.

Implementing IM practices also enhances interaction between employees and employers, fostering a greater exchange of ideas, experiences, and thoughts. This, in turn, boosts employee creativity (Gjurašić & Marković, 2017). Additionally, these practices support the growth and development of employees, which can further strengthen their creative capabilities (Ferdous & Polonsky, 2014), but there is scarce evidence from the literature on the relationship between IM and employee creativity. Hence, we hypothesize:

H2.

Internal marketing positively influences employee creativity.

Employee agility entails employees adapting to changes and seeking new, innovative solutions (Chonko & Jones, 2005). Agile employees can quickly respond to new challenges, promoting creative thinking and generating new ideas, thus fostering creativity. Ameen et al. (2024) argue that agility techniques enhance creativity. Integrating these attributes with intuition, judgment, and risk-taking substantially enhances an organization’s capacity for generating innovative product ideas and fostering creativity. Additionally, organizational agility facilitates human performance throughout the creative process, encompassing idea generation and product development (Kiranantawat & Ahmad, 2023)

Rasheed et al. (2023) reported a positive relationship between social media usage and employee agility and creativity. In their study, employee agility was identified as an important underlying psychological process in the association between social media usage and employee creativity. This research examines the targeted use of social media as a key external construct, which is more specific than the broader concept of IM. Franco and Landini (2022) emphasize that workforce agility can enhance innovation by promoting intrinsic motivation and creativity. However, the primary focus of their research was on exploring the relationship between agility and innovation, rather than directly investigating the link between agility and creativity. Empirical studies also show evidence of a reverse effect, i.e., that creativity can influence employee agility (Khaddam, 2020). Thus, we propose:

H3.

Employee agility positively influences employee creativity.

2.4. Employee Engagement

Engaged employees are committed to their company’s goals and values and are motivated to contribute to its success actively. This engagement enhances their sense of well-being. Employee engagement has several positive outcomes, such as job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, and reduced absenteeism. These benefits are also associated with effective internal management. Engaged employees experience higher levels of job satisfaction and demonstrate greater commitment to their organization, leading to improved performance and productivity. This increased productivity can provide a competitive advantage and foster creative work among employees.

IM enhances employee engagement by promoting a strong organizational culture and aligning employees with company values. This fosters better communication, increases brand commitment, and boosts job satisfaction, leading to higher engagement levels. It is a two-way process where the company’s investment in IM encourages employees to put forth their best efforts.

According to Črnjar et al. (2020), effective IM practices lead to higher levels of employee commitment, job performance, and motivation within the hotel industry. Other empirical studies show that IM positively affects employee engagement by enhancing emotional and cognitive aspects and boosting physical engagement (Saks, 2006; Shuck & Reio, 2014). Strategies for IM can be implemented to enhance employees’ engagement in value (co)-creation activities (Boukis, 2019; Vivek et al., 2012). Furthermore, tailored communication strategies that treat employees as internal customers can increase engagement by addressing their motivations and aspirations (e.g., Chikazhe & Nyakunuwa, 2022). None of the research involved agility and creativity, while simultaneously testing the indirect impact of IM on employee engagement through employee agility and creativity. Our next hypothesis is:

H4.

Internal marketing positively influences employee engagement.

When employees show creativity in their work, this leads to greater commitment to their tasks and the company. The more creative employees are, the more committed they are to their work and the more connected they feel to their tasks and the company (Rezvani et al., 2016; Andleeb et al., 2019). Previous literature has only addressed this issue in recent years, but there is empirical evidence of the links between employee agility and employee engagement. However, most studies assume that engaged employees are more creative because they are physically, cognitively and sympathetically connected to their creativity (Kahn, 1990) and because different dimensions of engagement can motivate employees to develop new ideas (Christian et al., 2011).

Some recent studies (Al-Ajlouni, 2021; Bakker et al., 2020) support the positive and significant relationship between engagement and creativity, demonstrating that organizational support and valuing their contributions encourage employees to complete work tasks in a productive and creative way. Chang and Shih (2019) found that high levels of creativity are associated with higher levels of employee engagement in experimental and exploratory tasks. Hence, our hypothesis is:

H5.

Employee creativity positively influences employee engagement.

Employee agility enables individuals to adapt, learn and respond effectively to changing work environments, promoting greater engagement. When employees demonstrate agility, they proactively seek out learning opportunities, embrace challenges and cultivate new skills, which increases their investment in their work. This continuous development increases motivation, job satisfaction and commitment to organizational goals. In addition, agile employees are more inclined to contribute innovative ideas and collaborate effectively, which further strengthens their sense of purpose and engagement in the workplace. Employee engagement is influenced by an individual’s ability to learn and adapt. Activities that encourage continuous learning, curiosity and open dialog are important to increase engagement as they provide both external and internal motivation. These learning opportunities not only help employees achieve their goals, but also support their professional development (Eldor & Harpaz, 2016).

The importance of employee agility to organizational success and securing competitive advantage is widely recognized (Morgan, 2004; Jager et al., 2022). Talent management initiatives that focus on employee development and empowerment, as well as the integration of technology to improve communication and collaboration, hold great promise for increasing employee agility. This comprehensive approach to employee development fosters organizational growth and a resilient, forward-thinking culture, helping companies achieve sustainable success.

Previous research has examined various aspects of agility, focusing on the relationship between employee agility and employee engagement. The key dimensions of agility—including perceptual agility, decision-making agility and action agility—are important determinants of job engagement. According to Nafei (2017), these dimensions have a positive influence on employees’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement, underscoring the importance of agility in dynamic work environments.

Learning agility has been shown to have an impact on innovation behavior, with employee engagement serving as a key mediating factor (Jo & Hong, 2022). Employees with higher learning agility tend to be more engaged, which in turn promotes creativity and innovation. Additionally, organizational agility plays a crucial role in enhancing employee engagement. However, the relationship may not be linear; moderate levels of agility can increase engagement, while excessive agility can diminish its benefits (Busse & Weidner, 2020). Saputra et al. (2018) have also confirmed that employees’ learning agility directly influences their engagement.

Our study adopts a more concise and behavior-oriented approach to measuring employee agility, contrasting with previous research that sees agility as a multidimensional concept. We focus on four specific items: real-time work monitoring, quick task adaptation, openness to critical feedback, and emotional concentration in challenging situations. While this method provides a more practical assessment of employee adaptability, it covers fewer aspects of agility compared to existing multidimensional models. Along with direct effect measurement, it also allows for the assessment of the indirect impact of IM on engagement through agility. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H6.

Employee agility positively influences employee engagement.

2.5. Employee Satisfaction

Employee satisfaction is the main goal of IM; hence it makes sense to address it in all research in this field. Job satisfaction is presumed to be a pleasant and positive emotional state resulting from evaluating or assessing one’s work or work experiences. A satisfied employee has a lower desire for turnover and strives for greater loyalty to the company. Additionally, it has been shown that IM, employee engagement, and job crafting positively influence job satisfaction (Saks, 2006; Shuck & Reio, 2014; Toma & Kant, 2024). Understanding and increasing job satisfaction is important for organizations to retain talented employees and maintain a competitive advantage.

Employee creativity is linked to job satisfaction, as it empowers individuals to shape their work environment and enhance their professional success (Janssen et al., 2004). New employees often face uncertainty and may engage in creative behaviors—like adjusting tasks and improving communication—to gain control over their roles. This creativity fosters better working conditions and leads to higher job satisfaction (Janssen et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2009).

Zhou and George (2001) found that creative actions help reduce dissatisfaction by enabling employees to perform tasks more effectively. Creativity also positively impacts workplace dynamics; when it benefits colleagues and processes, job satisfaction tends to increase. Additionally, positive emotions, which are linked to creativity, contribute to overall job satisfaction (Isen & Baron, 1991).

Employee creativity is also one way to generate new ideas and ensure competitive advantages. A creative employee is satisfied because creativity enables expression in the workplace and a sense of purpose and benefit. Improving creativity allows employees personal development and advancement, contributing to greater satisfaction (Rezvani et al., 2016; Gursoy et al., 2018).

Previous research has confirmed the positive association between creativity and employee satisfaction (Kim et al., 2009; Sacchetti & Tortia, 2013; Valentine et al., 2011). Nemanich and Keller (2007) note that supporting creative thinking in the context of transformational leadership also promotes job satisfaction. Jaskyte et al. (2020) studied the association of employee attitudes and values toward creativity with pleasure and found that this relationship can be positive but not necessarily in different cultural contexts. Research studies also confirm the inverse positive relationship between employee satisfaction and workplace creativity (Sugiarto & Huruta, 2023; Akgunduz et al., 2018), which have also reported a positive relationship. Accordingly:

H7.

Employee creativity positively influences employee satisfaction.

Employee engagement and job satisfaction are closely related, with engagement often leading to higher levels of satisfaction. When employees feel engaged in their work, they experience a sense of purpose, motivation, and fulfillment, which enhances their overall job satisfaction. Engaged employees tend to be more productive, committed, and willing to put forth effort in their roles, resulting in positive workplace experiences that reinforce their satisfaction (Harter et al., 2002). Macey and Schneider (2008) have found a strong link between employee engagement and various positive outcomes. When employees understand the purpose and benefits of their work, they develop a greater sense of well-being (Saks, 2006; Shuck & Reio, 2014), increasing their job satisfaction. Additionally, social exchange theory suggests that when employees receive socio-emotional rewards from their organization, they cultivate a stronger sense of commitment and satisfaction, further enhancing their levels of engagement.

Our research presents a conceptual shift by examining the relationship between job satisfaction and employee engagement from a different perspective. Unlike previous studies, which generally focus on how job satisfaction positively influences employee engagement, we hypothesize that inclusion is the primary driver of job satisfaction. Existing literature primarily suggests that well-designed, challenging, and motivating workplaces enhance job satisfaction, leading to higher inclusion (Biswas & Bhatnagar, 2013). It also asserts that satisfied employees tend to be more committed and effective (Arifin et al., 2019; Pongton & Suntrayuth, 2019). In contrast, our research emphasizes the role of inclusion as the main predictor of job satisfaction. We consider engagement not just as a result of favorable working conditions, but as a psychological state that fosters positive evaluations of work. By adopting this perspective, we move away from the traditional models focused on workplace motivation and test the idea that higher inclusion enhances feelings of fulfillment, satisfaction, and value in one’s work. This approach builds on existing knowledge and offers a more dynamic understanding of the relationship between inclusion and employee satisfaction. Some recent studies also report the same directional relationship; but they typically view it as a secondary or reciprocal effect (Hendriks et al., 2022; Maleka et al., 2021). A study by Ababneh et al. (2019) suggests that organizations seeking to boost engagement should prioritize improving job satisfaction. To achieve this, it is important to focus on intrinsic and extrinsic factors, such as job autonomy, recognition, and fair compensation (Tepayakul & Rinthaisong, 2018). Overall, the evidence underscores that increasing job satisfaction through meaningful work and positive organizational support is essential for fostering high levels of employee engagement. Based on these findings, we have formulated the following hypothesis:

H8.

Employee engagement positively influences employee satisfaction.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Sample

The data were collected using an online survey, and the research involved employees in Slovenia from different sectors and companies. The sample consisted of 89 respondents, with 45% men and 55% women. On average, the respondents have been employed for 7.4 years. Regarding work arrangements, 60% of the sample work from the office, while 40% work in a hybrid arrangement. Additionally, only 37% of respondents have flexible working hours, and others have fixed working hours. The average age of respondents was 39 years. The sample for this study was a non-random judgmental sample.

3.2. Measuring Instrument

The measurement instrument underwent a validation process, integrating items sourced from existing literature and by the researchers. The instrument was developed in two phases. Initially, an assessment of content validity ensued, engaging four expert reviewers, comprising two academics from the field of IM and two proficient in marketing research. Subsequently, a questionnaire was formulated in English before undergoing translation into Slovenian, employing the back-translation methodology to ensure linguistic and conceptual fidelity.

The five-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), was used to measure the proposed concepts. A list of items for measuring IM was developed from items previously used in the literature (Foreman & Money, 1995; Lings & Greenley, 2005; Gounaris, 2006; Tsai & Tang, 2008). Items for measuring employee satisfaction were adopted from Williams and Anderson (1991), Rue and Byars (2003), Kaliski (2007) and Y. Huang and Rundle-Thiele (2015). Additionally, some were self-generated. Creativity was measured using the scale by George and Zhou (2001). A scale for measuring employee engagement was adopted from Robinson et al. (2004) and Gallup (2006). Employee agility was measured using items adopted from Alavi et al. (2014).

3.3. Dimensionality, Reliability, and Validity of the Scales

To assess the potential influence of common method bias, first, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted by loading all measurement items into an unrotated exploratory factor analysis. The results showed that the first factor accounted for only 33.30% of the total variance, which is well below the commonly cited threshold of 50%, indicating that no single factor dominated the variance of the measures. Second, we applied the common latent factor technique (Collier, 2020). Loadings on a common latent factor were 0.22 or less, and the comparison between the baseline model and the model including the common latent factor revealed a non-significant chi-square difference (Δχ2 = 2.96, df = 1), suggesting that the inclusion of a common method factor did not meaningfully improve model fit. Together, these results indicate that common method bias is unlikely to pose a serious threat to the validity of our findings.

As the first step, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using the statistical software IBM SPSS 30 and AMOS 27. Structural as well as measurement models were estimated with the covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM). Despite the small sample size, which was more in favor of using PLS-SEM, other arguments were strongly in favor of using CB-SEM, namely, a large enough number of indicators, small deviations from normal distribution, and the development of hypotheses (theory) testing. Additionally, CB-SEM facilitates global goodness-of-fit indices and allows for assessing how well the entire model reproduces the observed covariance matrix, meaning that it generally offers more accurate and unbiased parameter estimates under correctly specified models, making it preferable for rigorous hypothesis testing.

Some items were excluded from the analysis if their factor loadings were low, based on model fit and modification indices. In order to simplify the structure of the model, we first implemented a factor analysis of the IM construct, which was then converted into a second-order concept by calculating latent scores.

IM was first tested as a single-construct concept, followed by the multi-construct test with three latent variables. The latter model had a much better fit and was retained. The CFA results show that all indicator loadings, except for one, are higher than the suggested value of 0.6. The values range from 0.46 to 0.68. Additionally, the composite reliabilities for the scales are reliable, as they range from 0.71 to 0.87 and are within the suggested intervals. The AVE values range from 0.48 to 0.61, and only for the training construct the value did not exceed the suggested threshold of 0.5. Based on the model, it appears to be a good fit as all the indices fall within the suggested intervals when compared to the criteria set by representative literature (e.g., Byrne, 1994; Hu & Bentler, 1999). These criteria have acceptable thresholds of RMSEA < 0.08, TLI > 0.90, CFI > 0.90, and IFI > 0.9.

The Fornell-Larcker test was conducted to evaluate the correlation between the latent constructs and the square roots of AVE. The results are presented in Table 1, which shows that the square root of the AVE calculations is higher than the correlations between the constructs. The HTMT matrix (Henseler et al., 2015) was used to further assess the discriminant validity of the scales. The results indicated that all the correlation ratios between latent variables were lower than the recommended threshold of 0.85, as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, CFA Loadings, AVE, and CR for the First-Order Internal Marketing Construct.

Table 2.

Correlations between latent variables, square roots of AVE and HTMT ratios of correlations.

The next step involved testing the structural model, which included the addition of IM as a second-order factor with three indicators: internal communication, motivation, and training. The Second-order IM factor was calculated using the latent scores. This model also integrated other constructs from the conceptual model and hypotheses: employee satisfaction, creativity, engagement, and agility. The measurement model showed an appropriate fit with respect to the following fit indices: χ2/df = 1.522 (p < 0.05), CFI = 0.911, RMR = 0.040, RMSEA = 0.077, IFI = 0.910, and TLI = 0.893. It is worth noting that the χ2 value was significant, indicating a less-than-perfect fit. However, this index is known to be highly sensitive to the small sample size. Additional evaluation with other indices showed that they were within the suggested thresholds, except TLI, which was slightly below 0.9.

Based on Table 3, all scales exhibit convergent validity, with average variance extracted coefficients exceeding 0.5, except for employee agility. Small samples in SEM models usually lead to lower AVE values (dos Santos & Cirillo, 2023) because they reduce the stability of factor loadings, increase the measurement error, and cause instability of correlations between indicators, so the AVE decreases, and it is more difficult to reach the 0.50 threshold, meaning that explained variance in our study may therefore be appropriate.

Table 3.

Means, Standard Deviations, CFA Loadings, AVE, and CR for all included latent variables.

Additionally, all indicator loadings were higher than 0.6. All composite reliability coefficients exceeded 0.6, which is the suggested threshold for a reliable scale. Further, the discriminant validity analysis was conducted using HTMT ratios of correlations calculation (Table 4), which showed no problems with discriminant validity since all ratios were below or close to the limit value of 0.85.

Table 4.

HTMT ratios of correlations between latent variables.

4. Results

A structural model was constructed to test the proposed hypothesis, and its fit was evaluated using various fit indices, including the χ2 value. Although the χ2 value was statistically significant and the TLI was slightly below 0.9, other fit indices were within the suggested boundaries. Specifically, the CFI was 0.912, RMR was 0.041, IFI was 0.915, and RMSEA was 0.076.

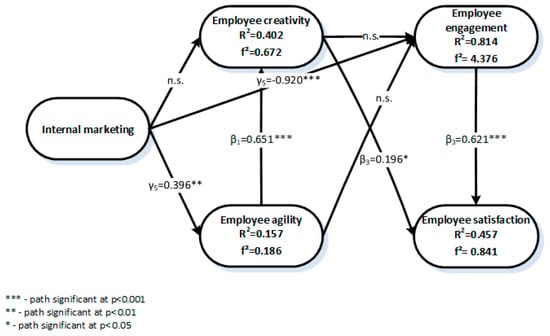

The structural model results and the relationships among constructs are presented in Table 5 and Figure 1, which also presents the latent variables’ R2 values and Cohen’s f2 coefficients. Our results show that IM significantly affects employee agility (H1, β = 0.396, p < 0.01). The relationship between IM and employee creativity (H2) was found to be non-significant (β = −0.048, p > 0.05), suggesting that IM efforts may not directly influence employees’ creative ideation processes. Therefore, we additionally tested (Kenny & Judd, 2014; Preacher et al., 2007) the indirect influence of IM on creativity through agility, and the result was positive and significant (βm = 0.258, p < 0.01).

Table 5.

Results of the structural model.

Figure 1.

Structural model, R2 values, and Cohen’s f2 coefficient of latent variables.

IM substantially positively impacts employee engagement (H4, β = 0.920. p < 0.001). Also, employee creativity positively impacted employee satisfaction (H7, β = 0.196, p < 0.1), at the lower level of statistical significance. Concerning H5, the relationship between creativity and employee engagement was insignificant (H5, β = −0.037, p > 0.05).

Employee agility emerged as a significant predictor of employee creativity (H3, β = 0.651, p < 0.001), but did not significantly impact employee engagement (H6, β = −0.029, p > 0.05), suggesting that its direct influence on overall engagement levels may be limited.

Lastly, employee engagement exhibited a strong positive association with employee satisfaction (H8, β = 0.621, p < 0.001), indicating that actively engaged employees are more likely to experience higher levels of job satisfaction within the organizational context.

5. Discussion

The findings suggest a significant impact of IM on employee agility and engagement (H1, H4). Improved IM initiatives are related to elevated levels of employee agility and engagement. While previous research (Saks, 2006; Shuck & Reio, 2014; Črnjar et al., 2020) has established a relationship between IM and employee engagement, this study makes a valuable contribution by highlighting the significance of IM in cultivating agile employees. It shows that employees are more agile when organizations promote IM culture and reward adaptive behaviors. Professional development and training opportunities enhance employees’ skills, making them more versatile. A positive work environment boosts job satisfaction and decreases resistance to change, leading employees to be more open to new ideas. Therefore, a supportive and enjoyable workplace is essential for fostering agility among employees.

The finding that IM has no impact on creativity (H2) contradicts the existing literature, particularly the study by Gjurašić and Marković (2017). It is possible that the cultural context of Slovenia defines the relationship between IM and creativity. Market conditions or economic uncertainty can affect the expression of creativity independently of IM. Organizations undergoing digital transformation may already have internal processes in place that mitigate the direct impact of IM. Also, measurement constraints or a relatively small sample size could contribute to the absence of a significant impact. It makes sense to consider these alternative explanations, but at the same time, it is important to consider the implications of these findings for theory and practice. The lack of a significant impact of IM on creativity suggests that while IM practices aim to foster employee engagement and satisfaction, they may not directly influence the generation of creative ideas. However, the indirect influence of IM on employee creativity through employee agility suggests that IM initiatives may indirectly stimulate employee creativity by nurturing a work environment characterized by flexibility, autonomy, and a supportive culture that encourages experimentation and risk-taking.

The research also revealed that employee agility has a positive impact on creativity (H3). Agile employees adapt quickly, experiment with new approaches, and respond flexibly to changing situations. This openness to learning and trying alternative solutions fosters an environment where novel ideas can emerge. By remaining proactive and resilient in the face of uncertainty, agile employees are more likely to generate creative insights and contribute innovative solutions.

In contrast, no relationship was observed between employee creativity and engagement (H5). Despite a small sample size, which may lead to such results, this finding appears counterintuitive, given the positive associations often drawn between these two constructs in the literature (Al-Ajlouni, 2021; Bakker et al., 2020). Employee engagement is often driven by intrinsic motivation (e.g., Thomas, 2009; Ghosh et al., 2020). Creativity can boost intrinsic motivation, but it may not always align with extrinsic motivators, such as recognition and career advancement, which are also important for engagement. Employees often expect their creativity to be valued and lead to meaningful changes, but if their ideas are overlooked, they may feel disillusioned and disengaged. This highlights the complex relationship between creativity and employee well-being, underscoring the need to examine factors affecting engagement related to creativity.

This study did not confirm the positive relationship between employee agility and engagement (H6). This could be because some of these studies tested the impact of engagement on agility (Sugiarto & Huruta, 2023; Akgunduz et al., 2018). Also, some suggested a non-linear relationship (Busse & Weidner, 2020). Once again, a small sample could be the reason, but also the way we measure agility, as we have operationalized this construct at the individual level and as a general self-assessment of ability, whereas many previous studies use more differentiated, multidimensional, or behavior-oriented measures (e.g., learning agility, decision-making agility, organizational agility). Additionally, our results suggest that the relationship between agility and engagement may not be universal, but dependent on institutional conditions. In Slovenia, which is in the final stages of transition from a regulated to a market economy, organizational systems are often still relatively formalized and less flexible, which can limit the expression of individual agility. In such an environment, agile employees may encounter structural barriers that prevent their agile skills from transforming into greater engagement—for example, rigid decision-making processes, limited autonomy, or low tolerance for experimentation. Such circumstances may explain why well-established theoretical relationships have not been empirically confirmed in our case.

The relationship between creativity and satisfaction (H7) is consistent with the growing body of literature indicating that creativity in the workplace is a key driver of job satisfaction (Kim et al., 2009; Sacchetti & Tortia, 2013; Valentine et al., 2011).

As in previous studies, we confirmed that engagement influences employee satisfaction (H8) (Karatepe, 2013; Shabane et al., 2022; Farooq et al., 2024), suggesting that employees who feel engaged in their work are more likely to be satisfied with their jobs. Since IM impacts engagement, which in turn influences satisfaction, it highlights its importance for overall employee satisfaction.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study enriches the field of IM by proposing and empirically testing relationships within the multidimensional conceptualization of engagement, agility, and creativity concepts. Additionally, it examines the relationships between IM and factors that may potentially influence outcomes. Lastly, this study underscores the significance of employee agility and creativity, highlighting their potential to significantly impact a company’s success and bolster its competitive advantage.

Since this study shows that IM indirectly impacts employee creativity through agility, it challenges the classic theory that understands IM as a general enabler of positive employee behavior. It makes an important theoretical contribution to the IM field, in that creativity can only be achieved with agile employees who adapt to changing circumstances, acquire new skills, and effectively respond to dynamic challenges within the organizational environment. Furthermore, employee agility has a positive influence on creativity. Employees who feel empowered and encouraged to explore new ideas and approaches are more likely to engage in creative thinking processes, generating novel solutions and innovations within the organization. This is a new finding that may warrant further research. The results of the research contribute to the theoretical understanding of employee agility as a key individual factor in modern organizational environments. Affirming the positive impact of agility on creativity aligns with dynamic capabilities theory (Teece et al., 1997), which posits that employee adaptability is the core of organizational innovation. While it builds on existing models that focus primarily on organizational or process agility, it also emphasizes that the underlying mechanisms of adaptability and innovation begin at the individual level. In doing so, the study opens up space for more in-depth micro-fundamental explanations of organizational agility, shifting attention from systemic characteristics to the behavioral abilities of employees, which can then be applied to the macro level. Employee agility appears to be more directly linked to tasks that require creative problem-solving or innovation. In such situations, agile employees can quickly adapt to changes and develop innovative solutions, thereby positively influencing their creativity. The organizational culture fostered by IM activities can also play a role. If the organizational culture emphasizes effective internal communication, training, and rewards for creative thinking, agile employees may feel more empowered to express their creativity, leading to a positive impact on creativity. This result again highlights the importance of the relationship between IM, agility, and creativity for organizations.

The results regarding the relationship between creativity, engagement, and employee satisfaction raise important theoretical questions. The lack of a relationship between creativity and engagement, as well as between agility and engagement, highlights the complexity of these constructs and their dependence on institutional conditions. This is in line with the Job Demands–Resources model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), which emphasizes that engagement depends on a balance between requirements and resources, with creativity or agility not in itself being a necessary resource if the organization does not provide autonomy, support, or space to bring ideas to life. Future theoretical models of engagement need to be complemented by a multi-conceptual understanding of agility, its different dimensions, and the organizational context in which these personal resources can—or cannot—be translated into engaged behavior. Traditional theories suggest that creative individuals exhibit higher levels of engagement due to greater intrinsic motivation and a stronger sense of purpose. However, our results show that this relationship is not always present in specific post-transition economies. This opens up space for theories that make a clearer distinction between creativity as a personal characteristic and creativity as actual behavior made possible by the environment.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Our study provides valuable insights into the relationship between IM and employee outcomes in Slovenian organizations. The implications for organizational leadership highlight the importance of prioritizing employee needs and preferences by implementing effective IM practices. Managers should focus on IM initiatives that equip employees with critical information, resources, and training. By ensuring that their employees are well informed and have the necessary skills, organizations can promote agility. In addition, fostering a flexible corporate culture that rewards adaptability can further improve employee agility and lead to greater responsiveness and innovation. This can be achieved through targeted “agility boosters”—micro-training sessions focused on rapid problem-solving, scenario-based simulations, and cross-functional rotation weeks. These activities directly enhance employees’ ability to switch tasks, adapt quickly, and manage uncertainty.

Managers can harness its indirect effects through agility even if IM does not directly impact creativity. By fostering a culture of learning, flexibility, and autonomy, managers can increase the creativity of their employees. Organizations should create platforms for knowledge sharing, cross-functional collaboration, and risk-taking that enable employees to develop innovative solutions and drive business success. Also, using IM practices on their own may not be enough to support creativity if employees are not motivated to exhibit agile behavior. Companies can conduct “creative sprints,” which are time-limited sessions where teams generate ideas and quickly develop small prototypes. This method translates agility into creative output, ensuring that creativity is not only encouraged but also operationally supported while incorporating IM practices.

The study reveals that while creativity increases job satisfaction, it does not necessarily increase engagement, suggesting that managers should ensure that creative achievements are recognized, rewarded, and integrated into the company’s decision-making process. Establishing feedback loops that allow employees to see how their ideas are implemented can increase engagement and prevent potential disillusionment. Also, linking creativity to tangible career development opportunities can help bridge the gap between creativity and engagement.

Given that IM impacts agility, engagement, and satisfaction, organizations should treat IM as a strategic priority rather than an administrative function. A well-structured IM strategy can set an organization apart from the competition by fostering a workforce that is adaptable, motivated, and committed to the company’s success.

Small companies often lack separate human resource departments, so they can implement measures directly, such as regular internal communication (meetings, emails, chat channels), clear presentations of goals and expectations, and prompt feedback to employees. The results show that employee agility has a strong impact on creativity, allowing small businesses to capitalize on this by employing flexible task assignment and experimentation, as they lack the complex formal structures that can inhibit agility. They can also ensure that employees’ ideas are recognized and used. This can include informal praise, incorporating ideas into product development, or smaller rewards that increase satisfaction and motivation. Since IM affects agility and engagement, large companies need formalized processes, systematic competency development programs, and tools to monitor employee satisfaction and engagement. Agility does not always lead to greater engagement when there are rigid structures in place. Large companies can learn that they need to create space for autonomy and quick decision-making and reduce bureaucratic hurdles to allow employee agility to be effectively expressed.

We recommend that the policy place greater emphasis on addressing the specific needs of employees alongside their overall well-being. Meeting these needs involves providing the conditions and resources that enhance an employee’s work experience. In contrast, well-being refers to a broader psychological state that results from a combination of fulfilled needs and various personal and organizational factors. Achieving well-being is challenging without considering the specific needs of employees. Additionally, we propose establishing standards for workplace autonomy, prompt decision-making, and flexible work processes. These elements create an environment where individual agility can be effectively demonstrated.

Regular evaluations of these policies, supported by measurements of employee satisfaction, inclusion, and perceived organizational support, will help adapt practices to the actual needs of employees. This approach aligns with the fundamental mission of IM and can ensure the long-term sustainability and effectiveness of the implemented measures. We recommend that state policy place greater emphasis on meeting the needs of employees in its measures, in addition to prioritizing employee well-being. Needs met refer to specific conditions or resources that support an employee’s work experience, while well-being represents a broader, holistic psychological state that arises from a combination of those needs met and other personal and organizational factors and is difficult to achieve without considering the needs of employees. We also propose setting standards for workplace autonomy, quick decision-making, and flexibility in work processes, as this creates the conditions in which individual agility can be effectively expressed. Regular reviews of these policies, supported by measurements of satisfaction, inclusion and experience of organizational support, enable the adaptation of practices to the actual needs of employees, which is the basic mission of IM and can ensure the long-term sustainability and effectiveness of the implemented measures.

5.3. Conclusions

This study investigated the influence of internal marketing on employee agility, creativity, and engagement within the context of Slovenia. The findings reveal a significant relationship between internal marketing and agility, underscoring its crucial role in fostering both adaptability and innovative thinking among employees. Conversely, no direct impact of internal marketing on creativity was identified, suggesting that any potential effects on creativity may occur indirectly, facilitated by the creation of a supportive and flexible work environment. These insights warrant further exploration into the nuanced dynamics of internal marketing’s role in fostering creative capabilities among employees.

The impact of creativity on employee engagement has also not been confirmed, highlighting the complexity of the relationship between creativity and motivation. It is essential to recognize creative contributions and coordinate motivating factors effectively. The same applies to the influence of agility on engagement, which may be constrained by institutional factors, formalized processes, and limited autonomy within the Slovenian work environment.

The findings suggest that internal marketing plays an important role in fostering an agile workforce. However, its effects on creativity and engagement may vary depending on the context and organizational culture. Future research should explore the indirect effects of internal marketing, examine the different dimensions of agility, and include larger, more representative samples to gain a better understanding of how internal marketing can promote an innovative, flexible, and engaged workforce.

5.3.1. Limitations of the Study

The study provided valuable insights, but it is important to note its limitations. The most important limitation of our study is the small sample size (N = 89), which is below the recommended 200–300 participants to perform SEM analyses and thus the generalizability of the findings and statistical power. This can potentially reduce the statistical power of the model and may be the reason why some hypotheses (H2, H5, H6) have not been supported. Research that compared SEM models with different sample sizes (Goodhue et al., 2007; Westland, 2010; Wolf et al., 2013; Rožman et al., 2020), find that certain SEM method can yield problematic results with a smaller number of respondents. Although a larger sample size is often recommended, there are a number of studies where smaller samples are meaningful and informative—especially in studies where access to participants is difficult or expensive. This fits in with our context, where the population is specific and more difficult to access, which gives great importance to our empirical data. Overall, the study provides important insights for both theory and practice. Replicating this model with a larger, cross-cultural, and ideally longitudinal sample would be a highly valuable next step.

Although tests indicate a low likelihood of common method bias, it cannot be completely ruled out due to data being collected from a single source. Common method variance may still affect results, as responses were gathered simultaneously from individual respondents. Additionally, a desire for social approval might lead some to present themselves favorably, regardless of their true feelings (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Also, a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish temporal precedence between variables. As a result, while associations and correlations can be observed, it is not possible to determine causality or the direction of effects.

The sample was limited to Slovenian employees, which may affect the generalizability of the results to other cultural and geographical contexts. Future research should focus on evaluating the scale and its validity in different cultural contexts. In addition, it is important to recognize that this study was exploratory and focused on examining five specific constructs. Due to this approach, the study did not include control variables, such as employee and organizational demographic characteristics, which could potentially influence the regression results.

5.3.2. Future Research

To improve future research, it is important to consider these additional factors. Those could examine how individual characteristics such as age, gender, education level, and experience might affect the relationships between the constructs under investigation. Company-specific variables, such as industry type, size, and organizational culture, may also influence the strength and direction of these relationships. By accounting for these differences, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of the subtle factors that contribute to employee agility, creativity, satisfaction, and engagement in different organizational contexts. This would provide valuable insights into human resource management practices and organizational policies and facilitate the optimization of employee well-being and performance.

Future studies could use an experimental and longitudinal research framework to analyze the enduring effects of IM on creativity and its uniformity in different cultural settings. As suggested by Lings and Greenley (2005), there is an opportunity to examine the relationship between IM and other important outcomes such as organizational performance, turnover intention, and burnout in different cultural settings. Also replicating this model with a larger, cross-cultural, and ideally longitudinal sample would be a highly valuable next step. Subsequent studies could explore how IM practices, in combination with intrinsic and extrinsic motivators, recognition systems, and perceived value of creative contributions, influence the link between employee creativity and engagement. Additionally, more behavior-based measures of agility would be beneficial, while also considering how internal marketing practices and organizational structures interact with institutional constraints to determine how individual agility translates into employee engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H. and B.M.; methodology, T.H. and B.M.; software, T.H. and B.M.; validation, T.H. and B.M.; formal analysis, T.H. and B.M.; investigation, T.H. and B.M.; resources, T.H.; data curation, T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.H.; writing—review and editing, T.H. and B.M.; supervision, B.M.; project administration, T.H. and B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Economics and Business at the University of Maribor (protocol no. 2025/7, approved on 8 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used the following AI tools: GPT-4o and Grammarly v1.2 in order to enhance the writing process, providing suggestions and corrections to improve clarity, grammar, and overall effectiveness. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ababneh, O. M. A., LeFevre, M., & Bentley, T. (2019). Employee engagement: Development of a new measure. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 19(2), 105–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, P., Rafiq, M., & Saad, N. (2003). Internal marketing and the mediating role of organizational competencies. European Journal of Marketing, 37(9), 1221–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgunduz, Y., Kizilcalioglu, G., & Sanli, S. C. (2018). The effects of job satisfaction and meaning of work on employee creativity: An investigation of EXPO 2016 exhibition employees. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 66(2), 130–147. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/202743 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Al-Ajlouni, M. I. (2021). Can high-performance work systems (HPWS) promote organisational innovation? Employee perspective-taking, engagement and creativity in a moderated mediation model. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 43(2), 373–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S., Wahab, D. A., Muhamad, N., & Shirani, B. A. (2014). Organic structure and organisational learning as the main antecedents of workforce agility. International Journal of Production Research, 52(21), 6273–6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. Z., & Ahmad, N. (2017). Impact of pay promotion and recognition on job satisfaction (A study on banking sector employees Karachi). Global Management Journal for Academic & Corporate Studies, 7(2), 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ameen, N., Tarba, S., Cheah, J. H., Xia, S., & Sharma, G. D. (2024). Coupling artificial intelligence capability and strategic agility for enhanced product and service creativity. British Journal of Management, 35(4), 1916–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N., Potocnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state of the science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andleeb, N., Chan, S. W., & Nazeer, S. (2019). Triggering employee creativity through knowledge sharing, Organizational culture and internal marketing. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE), 8(8S), 275–279. [Google Scholar]

- Arifin, Z., Nirwanto, N., & Manan, A. (2019). Analysis of bullying effects on job performance using employee engagement and job satisfaction as mediation. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 9(6), 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands–Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Petrou, P., Op den Kamp, E. M., & Tims, M. (2020). Proactive vitality management, work engagement, and creativity: The role of goal orientation. Applied Psychology, 69(2), 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L. L., Hensel, J. S., & Burke, M. C. (1976). Improving retailer capability for effective consumerism response. Journal of Retailing, 52(3), 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, S., & Bhatnagar, J. (2013). Mediator analysis of employee engagement: Role of perceived organizational support, PO fit, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. Vikalpa, 38(1), 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukis, A. (2019). Internal market orientation as a value creation mechanism. Journal of Services Marketing, 33(2), 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukis, A., & Gounaris, S. (2014). Linking IMO with employees’ fit with their environment and reciprocal behaviours towards the firm. Journal of Services Marketing, 28(1), 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. M., Pattinson, S., Sutherland, C., & Davies, M. A. P. (2025). Internal marketing and organizational performance: A systematic review and future research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 194, 115384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, Y., Teo, S. T., Shacklock, K., & Farr-Wharton, R. (2012). Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, well-being and engagement: Explaining organisational commitment and turnover intentions in policing. Human Resource Management Journal, 22(4), 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, R., & Weidner, G. E. (2020). A qualitative investigation on combined effects of distant leadership, organisational agility and digital collaboration on perceived employee engagement. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41(4), 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (1994). Burnout: Testing for the validity, replication, and invariance of causal structure across elementary, intermediate, and secondary teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 31(3), 645–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, C., Licona, B., & Floyd, L. A. (2015). Internal marketing to achieve competitive advantage. International Business and Management, 10(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-Y., & Shih, H.-Y. (2019). Work curiosity: A new lens for understanding employee creativity. Human Resource Management Review, 29(4), 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikazhe, L., & Nyakunuwa, E. (2022). Promotion of perceived service quality through employee training and empowerment: The mediating role of employee motivation and internal communication. Services Marketing Quarterly, 43(3), 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chonko, L. B., & Jones, E. (2005). The need for speed: Agility selling. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 25(4), 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. E. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: Basic to advanced techniques. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Črnjar, K., Dlacic, J., & Milfelner, B. (2020). Analysing the relationship between hotels’ internal marketing and employee engagement dimensions. Trziste, 32(4), 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlačić, J., Črnjar, K., & Lazarić, M. (2018). Linking internal marketing and employee engagement in the hospitality industry. In A. Mašek Tonković, & B. Crnković (Eds.), 7th international scientific symposium “Economy of Eastern Croatia—Vision and growth” (pp. 785–794). University of J. J. Strossmayer in Osijek, Faculty of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, P. M., & Cirillo, M. Â. (2023). Construction of the average variance extracted index for construct validation in structural equation models with adaptive regressions. Communications in Statistics: Simulation and Computation, 52(12), 1639–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldor, L., & Harpaz, I. (2016). A process model of employee engagement: The learning climate and its relationship with extra--role performance behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(2), 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, F., Mohammad, S., Nazir, N., & Shah, P. (2024). Happiness at work: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 32(10), 2236–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, A. S., & Polonsky, M. (2014). The impact of frontline employees’ perceptions of internal marketing on employee outcomes. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 22(4), 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, S. K., & Money, A. H. (1995). Internal marketing: Concepts, measurement and application. Journal of Marketing Management, 11, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, C., & Landini, F. (2022). Organizational drivers of innovation: The role of workforce agility. Research Policy, 51(2), 104423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. (2006). Employee engagement: What’s your engagement ratio? Available online: https://www.gallup.com/q12-employee-engagement-survey/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- George, J. M., & Zhou, J. (2001). When openness to experience and conscientiousness are related to creative behavior: An interactional approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D., Sekiguchi, T., & Fujimoto, Y. (2020). Psychological detachment: A creativity perspective on the link between intrinsic motivation and employee engagement. Personnel Review, 49(9), 1789–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjurašić, M., & Marković, S. (2017). Does internal marketing foster employee creativity in the hospitality industry? A conceptual approach. Tourism in Southern and Eastern Europe, 4, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, D., Lewis, W., & Thompson, R. (2007). Research note: Statistical power in analyzing interaction effects: Questioning the advantage of PLS with product indicators. Information Systems Research, 18(2), 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S. P. (2006). Internal-market orientation and its measurement. Journal of Business Research, 59(4), 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S. P., Dimitriadis, S., & Stathakopoulos, V. (2010). An examination of the effects of service quality and satisfaction on customers’ behavioral intentions in e-retailing. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(2), 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, E. R. (2000). Internal marketing in the light of relationship marketing and network organizations. In Internal marketing: Directions for management (pp. 45–60). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D., Chi, C. G., & Lu, L. (2018). Antecedents and outcomes of frontline employees’ internal branding proactivity. Journal of Business Research, 88, 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Gwinji, W. A., Chiliya, N., Chuchu, T., & Ndoro, T. (2020). An application of internal marketing for sustainable competitive advantage in johannesburg construction firms. African Journal of Business and Economic Research (AJBER), 15(1), 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M. U., Malik, A. A., Hasnain, A., Faiz, M. F., & Abbas, J. (2013). Measuring employee creativity and its impact on organization innovation capability and performance in the banking sector of Pakistan. World Applied Sciences Journal, 24(7), 949–959. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, M., Burger, M., & Commandeur, H. (2022). The influence of CEO compensation on employee engagement. Review of Managerial Science, 17, 607–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, S. T., & Lim, W. M. (2024). Theory development in a globalized world: Bridging “doing as the romans do” with “understanding why the romans do it”. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 43(3), 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., & Rundle-Thiele, S. (2015). A holistic management tool for measuring internal marketing activities. Journal of Services Marketing, 29(6), 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-T., Rundle-Thiele, S., & Chen, Y.-H. (2019). Extending understanding of the internal marketing practice and employee satisfaction relationship: A budget Chinese airline empirical examination. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 25(1), 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D. J., Lee, A., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2018). Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(5), 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A. M., & Baron, R. A. (1991). Positive affect as a factor in organizational behavior. Research in Organizational Behavior, 13(1), 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jager, S. B., Born, M. P., & Molen, H. T. (2022). The relationship between organizational trust, resistance to change and adaptive and proactive employees’ agility in an unplanned and planned change context. Applied Psychology, 71, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O., Van de Vliert, E., & West, M. (2004). The bright and dark sides of individual and group innovation: A special issue introduction. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(2), 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskyte, K., Butkevičienė, R., Danusevičienė, L., & Jurkuvienė, R. (2020). Employees’ attitudes and values toward creativity, work environment, and job satisfaction in human service employees. Creativity Research Journal, 32(4), 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y., & Hong, A. J. (2022). Impact of agile learning on innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model of employee engagement and perceived organizational support. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 900830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadic-Maglajlic, S., Boso, N., & Micevski, M. (2018). How internal marketing drive customer satisfaction in matured and maturing European markets? Journal of Business Research, 86, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliski, B. (2007). Encyclopedia of business and finance. Macmillan Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O. M. (2013). High-performance work practices, work social support and their effects on job embeddedness and turnover intentions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(6), 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. A., & Judd, C. M. (2014). Power anomalies in testing mediation. Psychological Science, 25, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaddam, A. (2020). Impact of personnel creativity on achieving strategic agility: The mediating role of knowledge sharing. Management Science Letters, 10(10), 2293–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. Y., Hon, A. H., & Crant, J. M. (2009). Proactive personality, employee creativity, and newcomer outcomes: A longitudinal study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiranantawat, B., & Ahmad, S. Z. (2023). Conceptualising the relationship between green dynamic capability and SME sustainability performance: The role of green innovation, organisational creativity, and agility. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 31(7), 3157–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. F. (2007). The impact of website quality dimensions on customer satisfaction in the B2C e-commerce context. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 18(4), 363–378. [Google Scholar]

- Lings, I., & Greenley, G. (2005). Measuring internal market orientation. Journal of Service Research, 7, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, W. H., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleka, M. J., Schultz, C. M., Van Hoek, L., Paul-Dachapalli, L., & Ragadu, S. C. (2021). Union membership as a moderator in the relationship between living wage, job satisfaction, and employee engagement. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 64(3), 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R. E. (2004). Business agility and internal marketing. European Business Review, 16(5), 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafei, W. A. (2017). Job engagement as a mediator of the relationship between organizational agility and organizational performance: A study on teaching hospitals in Egypt. International Business Research, 10(10), 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M. S., Hassan, M., Hassan, S., Shaukat, S., & Asadullah, M. A. (2014). Impact of employee training and empowerment on employee creativity through employee engagement: Empirical evidence from the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 19(4), 593–601. [Google Scholar]

- Nemanich, L. A., & Keller, R. T. (2007). Transformational leadership in an acquisition: A field study of employees. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(1), 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemteanu, M. S., & Dabija, D.-C. (2021). The influence of internal marketing and job satisfaction on task performance and counterproductive work behavior in an emerging market during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]