Abstract

Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) play a crucial role in the global economy, accounting for approximately two-thirds of global employment and contributing significantly to the GDP of developed countries. Despite the availability of various cybersecurity standards and frameworks, SMEs remain highly vulnerable to cyber threats. Limited resources and a lack of expertise in cybersecurity make them frequent targets for cyberattacks. It is essential to identify the challenges faced by SMEs and explore effective defensive strategies to enhance the implementation of cybersecurity measures. The study aims to bridge the gap and help these organizations in implementing cost-effective and practical cybersecurity approaches through a systematic mapping study (SMS) conducted, where 73 articles were thoroughly reviewed. This research will shed light on the current cybersecurity approaches (practices) posture for different SMEs, along with the threats they are facing, which have stopped them from deciding, planning, and implementing cybersecurity measures. The study identified a wide range of cybersecurity threats, including phishing, social engineering, insider threats, ransomware, malware, denial of services attacks, and weak password practices, which are the most prevalent for SMEs. This study identified defensive practices, such as cybersecurity awareness and training, endpoint protection tools, incident response planning, network segmentation, access control, multi-factor authentication (MFA), access controls, privilege management, email authentication and encryption, enforcing strong password policies, cloud security, secure backup solutions, supply chain visibility, and automated patch management tools, as key measures. The study provides valuable insights into the specific gaps and challenges faced by SMEs, as well as their preferred methods of seeking and consuming cybersecurity assistance. The findings can guide the development of targeted defensive practices and policies to enhance the cybersecurity posture of SMEs for successful software development. This SMS will also provide a foundation for future research and practical guidelines for SMEs to improve the process of secure software development.

1. Introduction

In today’s business world, cybersecurity plays a critical role in safeguarding organizations. It involves implementing strategies, technologies, and measures to protect systems, networks, data, and software from cyber threats. As technologies become central to business operations, ensuring cybersecurity has become essential for protecting digital resources, maintaining operational continuity, and building customer trust in an aseasingly interconnected digital landscape. However, SMEs often lag behind larger organizations in adopting digital tools and robust cybersecurity measures. The digital divide has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with SMEs cutting back on IT spending while larger companies continue to invest in it (Arroyabe et al., 2024b). This disparity has left SMEs more vulnerable to cybersecurity risks compared to their larger counterparts. Against this backdrop, it becomes important to explore the connection between cybersecurity and SMEs, focusing on the specific threats they face and the strategies they can adopt to safeguard their operations. In Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs), integration with ICT is incredibly productive since it has changed the way SMEs do business, providing much better connectivity, efficiency, and market exposure. However, with the growing shift to digital operations for most companies, SMEs are also more vulnerable to cybercrimes (Arroyabe et al., 2024b; Chidukwani et al., 2022). While large companies can afford to put up an elaborate security system, SMEs are generally disadvantaged in their capacity to prevent cyber incidents because of inadequate finances, human resources, and technology (AlDaajeh & Alrabaee, 2024; Tam et al., 2021) Despite this, SMEs are an essential segment of the global economy, and their susceptibility to cyber risks constitutes specific threats to their performance and to other aligned business systems, such as supply and customer chains (Wong et al., 2022).

Today, threats like data leaks, malware, and ransomware attacks are more complex, posing severe consequences for organizations lacking adequate defences (Tanimu & Abada, 2025). These cyberattacks can lead to future losses of data and assets, legal consequences, reputational losses, and interrupted business processes (Fotis, 2024a). Furthermore, it is equally or even more essential to elaborate on the economic and operational consequences, which can be ten times more damaging to SMEs, many of which lack the financial and technical resources to recover quickly (Chaudhary et al., 2023; Nanda et al., 2024; W. Alhakami, 2024). As more firms realize the importance of cybersecurity, most SMEs continue to suffer from poor cybersecurity measures. Some of the reasons for this are a lack of funding, a lack of cybersecurity awareness amongst the staff, inadequate identification of risks, and core problems in placing security in other business activities (Erdogan et al., 2023). As a result, SMEs tend to use readily available and unsuitable software applications that do not solve their cybersecurity issues. Otherwise, they apply security solutions randomly, making them more vulnerable to cyber threats (Al Aamer & Hamdan, 2023; Arroyabe et al., 2024a).

The main objective of this paper is to present a precise mapping of cybersecurity threats and protection measures for SMEs in secure software. By synthesizing the existing literature and industry reports, the study identifies the most common cyber threats faced by SMEs. It examines the various defence mechanisms that have been suggested or implemented in response to these threats. This work aims to fill the identified gap in understanding the existing cybersecurity threats faced by SMEs and provide a framework that can be used to facilitate the process of determining the right cybersecurity solution for SMEs. This mapping divides the threats in terms of their characteristics, effects, and occurrences and assesses the protective actions of technologies, policies, structures, and training for organizational security. Therefore, this research helps the existing literature on cybersecurity in SMEs by presenting an up-to-date state and analysis of cybersecurity practices, threats, and countermeasures.

1.1. Research Objectives

The study has several key research objectives:

- To identify and categorize the types of cybersecurity threats most faced by SMEs.

- To evaluate and classify the defensive practices currently employed by SME to mitigate cybersecurity threats.

- To know the critical areas of focus in the existing literature on cybersecurity within SMEs and how these areas have evolved.

- To identify research methodologies and approaches used to study cybersecurity in SMEs and how they contribute to understanding SME-specific cybersecurity threats.

- To compare different regions and industries regarding the focus and findings of research on SME cybersecurity.

- To know about the critical gaps in the current research on SMEs cybersecurity needs to be addressed in future studies.

1.2. Significance of the Study

The findings from this study will be of significance to a variety of stakeholders, including SME owners, IT professionals, policymakers, and cybersecurity service providers. As SMEs increasingly become targets for cybercriminals, understanding the specific cybersecurity challenges they face and the most effective defence strategies will be crucial in helping them protect their operations. Additionally, the results of this mapping study will offer insights into the gaps in current cybersecurity practices and the need for tailored, affordable solutions for the SME sector. By addressing these gaps, SMEs can enhance their preparedness against cyber threats, thereby contributing to the broader goal of building a more secure and resilient digital economy.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 gives a comprehensive overview of the existing literature on the topic of cybersecurity threats and countermeasures for SMEs. Section 3 details the systematic mapping approach that was employed to determine and categorize the studies. Section 4 offers the mapping study’s results: the categorization of cybersecurity threats and defensive measures. Section 5 emphasizes the summary of the paper and recommends areas of further research. Implications of the study are explained in Section 6, while Section 7 contains the findings of the limitations of the study.

2. Literature Review

Small and medium-sized enterprises play crucial roles in the economy across the world, depending on them to provide a substantial number of employment opportunities and contribute a significant part of the GDP. However, these businesses remain one of the most susceptible to cyber threats because of poor financial conditions, a lack of awareness, and resources. This mapping study synthesizes existing research on the types of cybersecurity threats faced by SMEs, the defensive practices implemented, and the challenges in achieving cybersecurity resilience (Novelli et al., 2024).

2.1. Cybersecurity Threats to SMEs

SMEs face a wide range of cybersecurity threats, which can change dynamically. Studies have identified a range of threats that disproportionately impact SMEs.

Phishing and Social Engineering Attacks: Phishing is one of the most common cyber threats targeting SMEs, as indicated in (Waelchli & Walter, 2025). Previous research (Junior et al., 2023) has highlighted how cybercriminals exploit human vulnerabilities through deceptive emails and messages to gain unauthorized access to sensitive information. SMEs, often lacking robust email security solutions, are prime targets for these attacks.

Ransomware: The new trend in ransomware attacks has been especially terrible for SMEs. Djenna et al. (2024) have estimated that ransomware attacks rose by over 150% between 2023 and 2024, and many of the victims were SMEs. Accordingly, Djenna et al. (2024) underscore that SMEs are in danger since there are no proper backup solutions and incident response plans to mitigate the effects caused by ransomware attacks.

Data Breaches: The leakage of data represents a significant threat to SMEs that collect and store customer and financial information. Numerous studies have reported that SMEs frequently experience data breaches within their organizations (Al-Dalati, 2023; Chidukwani et al., 2022)

Insider Threats: Despite the fact that insider threats are either intentional or accidental, they have been proven to be dangerous for SMEs. Works, like those of Chidukwani et al. (2022); Moneva and Leukfeldt (2023), reveal that the risk is even higher for SMEs because of the lack of proper training of the employees and the inadequate implementation of access management practices.

Supply Chain Attacks: SME continues to be the favourite of cybercriminals because they are suppliers to large firms and can act as a gateway to penetrating large enterprises. Finally, a paper by Wong et al. (2022) examines supply chain security threats and the problems that SMEs encounter when trying to protect third parties’ relationships.

2.2. Defensive Approaches for SMEs

The following are the defensive measures undertaken by SMEs to counter cyber threats in a vertically integrated industry. However, the success of these measures depends on the size and existing awareness of the organization.

Technical Solutions: SMEs have increasingly turned to off-the-shelf security solutions, including firewalls, antivirus software, and endpoint protection (Moneva & Leukfeldt, 2023; Yin et al., 2020). Studies by Zadeh and Jeyaraj (2022) conclude that although these tools imply a certain amount of security, they fail to prevent such threats as Zero-day ones.

Employee Training and Awareness: There is general agreement about the fact that employee training is one of the most effective ways to address human risk factors, such as phishing and social engineering, that can be implemented at a relatively low cost (Beuran et al., 2023; Sushma et al., 2023).

Adoption of Cybersecurity Frameworks: Frameworks, such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework and ISO 27001, have been recommended for SMEs to address cybersecurity risks (Daim et al., 2024; Ding et al., 2021). However, according to research by Radanliev et al. (2023) the adoption of such frameworks is still relatively rare because it is thought to entail high complexity and expenses.

Cloud-based Security Solutions: The given solutions predict the continued growth of utilization for security solutions hosted by the cloud, which can be effective for SMEs with a cost-saving perspective (Qamar, 2022). Studies by Furfaro et al. (2018) provide a comparison of cloud-based services with their overall benefits, like software updates and centralized control. Still, the author notes that using the service of a third party requires extra vigilance.

Incident Response and Recovery Plan: It is important to build and sustain incident responses regarding cybersecurity threats since they happen frequently. Research by (Dawson et al., 2019; Geach, 2021) reveals that SME firms that have developed response plans return to normal operations and spend less than SME firms without such measures.

2.3. Challenges in Cybersecurity for SMEs

However, several challenges plague SMEs, which affect their cybersecurity posture even when protective mechanisms are available. Key barriers include:

Resource Constraints: SMEs’ lack of investment in cybersecurity is caused by their constant inability to procure more funds to purchase sophisticated security technologies. Fotis (2024b) demonstrates that organizations implementing preventive security measures may reduce the probability of a successful cyberattack by up to 70%.

Lack of Expertise: SMEs frequently do not possess an internal cybersecurity specialist, so they are forced to pay for a consultant or turn to MSPs. However, previous research (Al Aamer & Hamdan, 2023) shows that SMEs face a problem in selecting reliable vendors and assessing the quality of outsourced services.

Low Awareness and Prioritization: Cybersecurity is frequently perceived as a low-priority issue among SME owners and managers. Studies by Chidukwani et al. (2022) highlight the need for increased awareness campaigns to emphasize the importance of cybersecurity as a business enabler.

Regulatory Compliance: Compliance with regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and other local policies poses significant challenges for SMEs (Chaudhuri et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024; Wong et al., 2022). Research by Antunes et al. (2022) identifies a lack of understanding of compliance requirements as a critical barrier to implementation.

2.4. Research Gaps and Opportunities

Although significant progress has been made in understanding cybersecurity challenges and solutions for SMEs, several gaps remain unaddressed.

- To conduct a systematic mapping study to identify cybersecurity threats and the defensive practices employed by SMEs to address the identified cybersecurity threats.

- To conduct an empirical survey to identify the most prevalent cybersecurity threats and their mitigation practices identified through real-world industries that impact SMEs.

- To determine the gap between the findings of the literature review and real industry security threats that affect SMEs.

- To design a tailored cybersecurity mitigation model to address the cybersecurity threats facing SMEs. From the literature review, it is clear that SMEs require a more proactive approach to issues of cybersecurity. Despite several defensive strategies having been proffered, issues relating to resource concerns and awareness have not been addressed. This systematic mapping study (SMS) will fill the gap by presenting a systematic review of the existing cybersecurity threats and protective measures specifically for SMEs, thereby contributing to the development of practical, scalable solutions for enhancing their cybersecurity resilience.

3. Research Methodology

In this research, the authors used a systematic mapping study (SMS) (Petersen et al., 2008, 2015) approach, which is systematic and enables authors to categorize and analyze the existing literature. This research will seek to give an outline of cybersecurity threats to and defensive practices at SMEs (Laato et al., 2020). The SMS was chosen because it can offer a systematic map of a broad research field, outline research gaps as well as trends, and classify the literature for future use (Khan et al., 2021, 2022).

The research follows the PRISMA guidelines, which provide rigour and transparency to systematic review (Supplementary Table S1). The risks and practices were identified through thematic coding of the included studies, not limited solely to keyword occurrence during the search phase.

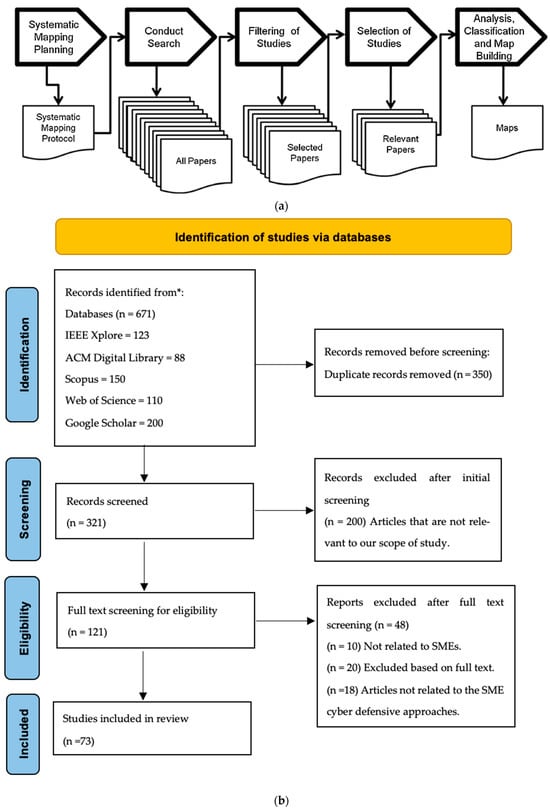

The goal is to make sure the criteria and procedure for the selection of all published articles are unbiased and relevant to our study scope. The transparency inherent to the SMS process forms the foundation for achieving high-quality standards in both the process and the results. Figure 1a,b presents the steps in SMS and PRISMA Flowchart.

Figure 1.

(a) Systematic Mapping Study process. (b) Systematic review flowchart (Page et al., 2021).

3.1. Research Questions

The main objective of the SMS is to identify the cybersecurity threats and defensive practices for small- and medium-sized firms. We outline the research question in a sophisticated way to collect mature work and identify trends which are directly related to the domain. In Table 1, the research questions (RQs) are discussed along with their key motivations.

Table 1.

Research Questions and Motivation.

3.2. Search String Development

The search strings were designed using Boolean operators and keywords related to the research questions. The following search strings were designed and shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Search strings.

3.3. Data Extraction

The selected articles were found from the well-known databases, which were based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria: The search parameters were narrowed down to target only publications published in English from 2015 to 2025, including peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and high-quality white papers. “High quality” refers to white papers published by reputable institutions, government agencies, or recognized research organizations that demonstrate methodological rigour, transparency, and relevance to the research objectives (De Cassai et al., 2025), focusing on cybersecurity threats or defensive approaches for SMEs.

Exclusion Criteria: The articles which are not in the English language and do not focus on SMEs cybersecurity, articles that are not peer-reviewed papers, blogs, and publications that lack empirical or theoretical contributions.

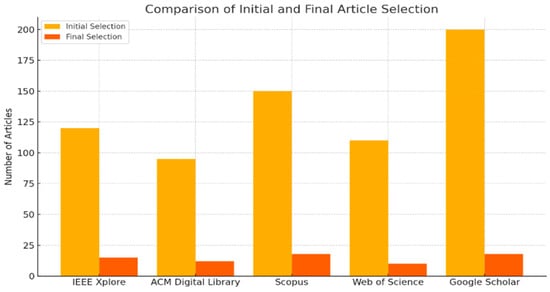

Figure 2 presents the comparison of the initial and final selection of articles in this study. The final sample size is 73 articles.

Figure 2.

Comparison of initial and final selection articles.

3.4. Search Execution

In total, 671 articles related to cybersecurity for SMEs were found from the different databases (see Table 3). After the implementation of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the duplicate articles were removed, and the articles which do not relate to cybersecurity specifically to SMEs were excluded. We selected 73 research articles as the final studies.

Table 3.

Articles found.

3.5. Mapping Process

The extracted data were organized into a systematic mapping framework consisting of three dimensions:

- Focus of Research: Categorized as either threats or defensive approaches.

- Research Contribution Type: Theoretical, empirical, or solution proposals.

- Research Type: Conceptual framework, empirical studies, or case studies.

- Area of Focus: Categorize as early and evolution focus.

- Region and Industries: The focus and findings of research on SME cybersecurity across different regions and industries.

3.6. Primary Data Selection

The selection process was carried out in three steps:

- Title and Abstract Screening: All retrieved studies were screened for relevance based on their titles and abstracts.

- Full-Text Review: Studies passing the initial screening were reviewed in full to ensure they met the inclusion criteria.

- Quality Assessment: The following systematic quality assessment criteria were adopted:

- Relevance (Weight: 30%)

- ○

- How closely does the article address cybersecurity threats or defensive practices for SMEs?

- ○

- Scored as:

- ▪

- High (3): Directly relevant to both SMEs and cybersecurity

- ▪

- Medium (2): Relevant to cybersecurity, but in general, not SME-focused

- ▪

- Lower (1): Limited or tangential relevance

- Scientific Rigour (Weight: 25%)

- ○

- Does the article use a validated methodology, theoretical framework, or empirical analysis?

- ○

- Scored as:

- ▪

- High (3): Strong methodology, data-backed findings

- ▪

- Medium (2): Moderate methodology, limited empirical data

- ▪

- Lower (1): Weak or absent methodology

- Innovation (Weight: 15%)

- ○

- Does the article propose novel threats, defensive practices, or frameworks?

- ○

- Scored as:

- ▪

- High (3): Strong innovation or unique perspectives

- ▪

- Medium (2): Moderately innovative

- ▪

- Lower (1): Lacks innovation

- Citation Impact (Weight: 10%)

- ○

- How widely is the article cited within its domain

- ○

- Scored as:

- ▪

- High (3): Frequently cited

- ▪

- Medium (2): Moderately cited

- ▪

- Lower (1): Rarely cited

- Publication Quality (Weight: 10%)

- ○

- Was the article published in a reputable journal or conference?

- ○

- Scored as:

- ▪

- High (3): Tier-1 journal or conference

- ▪

- Medium (2): Tier-2 or niche publication

- ▪

- Lower (1): Low-impact source

- Recency (Weight: 10%)

- ○

- Was the article published within the last 5 years?

- ○

- Scored as:

- ▪

- High (3): Published in the last 3 years

- ▪

- Medium (2): 3–5 years old

- ▪

- Lower (1): Older than 5 years

According to the above quality assessment criteria, the following data (see Table 4) were evaluated accordingly.

Table 4.

Quality assessment of final study sample (73 Articles).

4. Results and Analysis

The systematic mapping process identified a comprehensive range of cybersecurity threats faced by SMEs and corresponding defensive practices. The findings are categorized into the following six main themes: critical areas of focus, most prevalent cybersecurity threats, defensive practices, research methodologies and approaches, different regions and SME industries, and the critical gaps in the current research on SMEs.

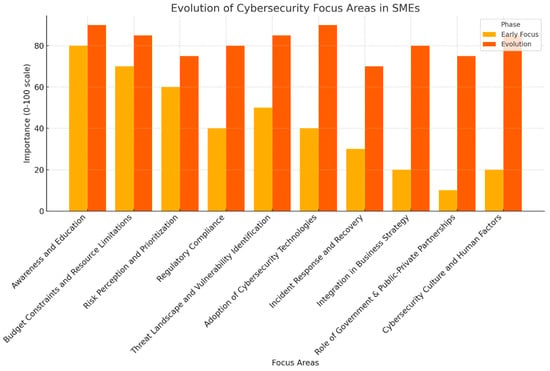

4.1. Critical Areas of Focus in Cybersecurity Within SMEs and How These Areas Evolved

The existing literature on cybersecurity within small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) primarily focuses on several critical areas, which have evolved in response to the growing sophistication of cyber threats and the increasing dependence of SMEs on digital infrastructure. The evolution in these areas reflects both a deep understanding of SMEs’ unique challenges in cybersecurity and the expansion of tools and strategies to address them. Figure 3 presents the main areas of focus and their evolution.

Figure 3.

Evolution of Cybersecurity Focus Areas in SMEs.

- Awareness and Education:

Early Focus: This refers to the initial stage of research emphasis, typically representing the foundational studies or conceptual frameworks identified in the earlier years of the reviewed literature. Early studies emphasized the limited cybersecurity awareness among SME owners and employees, often noting that SMEs lacked a basic understanding of cyber risks. The initial literature aimed to highlight the importance of cybersecurity and create awareness about common threats.

Evolution: This denotes the subsequent development and expansion of research themes, reflecting how the field has progressed over time through newer studies and emerging perspectives. In the past years, this sector has evolved to focus on tabled training and extensive awareness programmes tailored to SMEs, where emphasis is placed on frequency, phishing emails, and cybersecurity basics. The current paper discusses the effect of cybersecurity education on enhancing organizational security and awareness.

- 2.

- Budget Constraints and Resource Limitations:

Early Focus: The first trends showed that money is a crucial factor, as most SMEs could not afford to invest special funds for cybersecurity. Several smaller organizations were discouraged or indeed unable to afford to implement high-cost protection measures.

Evolution: Previously, the emphasis in this area was transitioning towards searching for affordable and mass-fit security solutions for SMEs, for example, cloud-based security products, open-source solutions, and MSPs, which include MSSPs. There is also emerging material on where and how SMEs can apply security investment to drive the most overall change, such as where budgets should go, but resources are constrained.

- 3.

- Risk Perception and Prioritization:

Early Focus: The early literature described the general observation that most SME managers lacked appreciation for cybersecurity, either dismissing it outright or considering themselves immune to such attacks. The study’s objective was to call attention to the problems and costs of failing to address cybersecurity.

Evolution: Present research focuses on risk mapping approaches specific to SMEs, and with the awareness that these companies require uncomplicated, easy-to-use tools to identify and rank their risks. There is also much more emphasis placed on identifying why SMEs are forced towards specific cybersecurity measures. Within this, regulatory compliance needs, customer expectations, and past incidents have been highlighted.

- 4.

- Regulatory Compliance:

Early Focus: Compliance was at first covered as an afterthought, while the literature predominantly revolved around highly developed companies. SMEs were always thought to be less relevant to complex compliance requirements.

Evolution: You need only look at the best practices for SMEs to protect their data, in the wake of the GDPR and CCPA, to note the increase in emphasis on compliance without the resources of larger companies. The scholarly literature increasingly discusses frameworks, checklists, and guidelines to help SMEs realize compliance with regulatory requirements, while avoiding overburdening their operations.

- 5.

- Threat Landscape and Vulnerability Identification:

Early Focus: During the early stages of research, the threats that are faced by SMEs were identified primarily, including phishing, ransomware, and social engineering attacks, with little regard for advanced attack vectors.

Evolution: There has been a concentration on comprehensive risk evaluations and risks of IoT, working remotely, and cloud computing in SMEs. The more recent papers focus on understanding the unique threats that affect SMEs and how SMEs can handle them without employing professionals with advanced security knowledge.

- 6.

- Adoption of Cybersecurity Technologies and Solutions:

Early Focus: The first literature recommended conventional IT security solutions, which were developed for large enterprises and failed to adapt to SME contexts.

Evolution: This has led to an increasing focus on designing and recommending cybersecurity solutions targeted at SMEs, including, but not limited to, EDR solutions, affordable firewalls, and simple MFA. Unlike fixed-priced and fixed-contracted services that are geared toward becoming a company’s exclusive technology partner in implementing its managed services and cloud computer-based solutions, flexibility and scalability are now pointed to as the virtues that make them particularly appropriate for SMEs.

- 7.

- Incident Response and Recovery:

Early Focus: Cyber incident response was, in the past, primarily overlooked, and few resources were available explaining how SMEs could protect themselves, and respond and recover from cyber incidents they had not deemed themselves likely to suffer from.

Evolution: The current literature is centred on the development of lean and efficient incident response strategies for SMEs, key areas of predesigned response models, guidelines for backup and disaster recovery, and the use of managed security service providers for incident response as a service. Current work shows that, for resilience, it is now essential for firms, including smaller ones, to always be prepared for an incident.

- 8.

- Integration of Cybersecurity in Business Strategy:

Early Focus: The first few studies that were conducted did not consider how cybersecurity must be incorporated into the business plans of SMEs, mainly because cybersecurity was always perceived as a standalone problem.

Evolution: Based on these outcomes, there is now increased emphasis on the need to integrate cybersecurity into an SME’s strategic plans with suggestions for leadership engagement, business as well as cybersecurity objective alignment, and the use of cybersecurity as an enabler of business sustainability and customer confidence.

- 9.

- Role of Government and Public–Private Partnerships:

Early Focus: The earlier literature did not pay much attention to the role of government because cybersecurity was formerly regarded as the affair of the business entity.

Evolution: The rise in new threats led to more attention being given to government-led efforts, joint industry sectors, and support structures to help SMEs enhance their cybersecurity posture. This comprises such things as funds, grants, and intellectual support services that assist SMEs in improving their security.

- 10.

- Cybersecurity Culture and Human Factors:

Early Focus: Much of the existing literature focused on the technical aspects of cybersecurity and did not consider users and the organizational context.

Evolution: This is where human factors come into play and are now understood, with much focus being laid on creating awareness of cybersecurity among SMEs. Academic work investigated what training, leadership, and organizational practices contribute to cybersecurity outcomes and enactment.

4.2. Most Prevalent Cybersecurity Threats That Impact SMEs

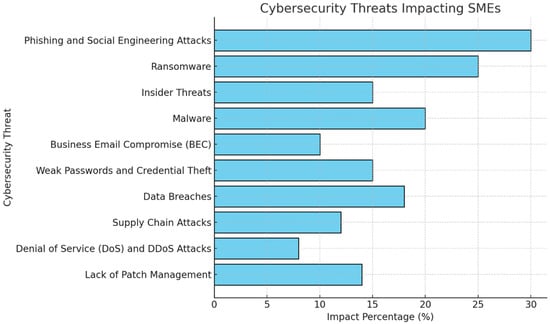

SMEs face a range of cybersecurity threats due to limited resources, insufficient security awareness, and often outdated infrastructures. Literature reviews commonly identified the following prevalent threats impacting SMEs (See Table 5 and Figure 4):

Table 5.

Cybersecurity threats impacting SMEs.

Figure 4.

Cybersecurity threats impacting SMEs.

- Phishing and Social Engineering Attacks:

SMEs are vulnerable to social engineering attacks, specifically phishing, where fraud artists attempt to trick users over the phone or email into divulging account information on computer systems. Inadequate cybersecurity insight and knowledge at the workplace typically fall victim to hackers, who use them as a means to penetrate restricted areas or obtain valuable information or login information.

Impact: Identity theft, violation of privacy, and perversion of funds.

Literature Insights: The literature review notes that phishing is still the most prevalent form of cyberattack because of its ease and ineffaceable impact.

- 2.

- Ransomware:

Malicious software encrypts critical business data, demanding ransom payments for decryption.

Impact: Lost time, lost work, and lost money.

Literature Insights: SMEs are generally at significant risk due to poor backup strategies and low resource capability for restoration.

- 3.

- Insider Threats:

Executives or normal computer users, either negligently or intentionally, cause attacks on systems.

Impact: Losing data and their reputations.

Literature Insights: The insider threat is more apparent due to failed or reduced employee training, coupled with failed monitoring.

- 4.

- Weak Passwords and Credential Reuse:

Inadequate password management results in risks; SMEs have a relaxed password policy as compared to large organizations.

Impact: Account and system control breakouts.

Literature Insights: Another reason why credential-stuffing attacks work as planned with SMEs is that there is always the repeated use of the same password across platforms.

- 5.

- Software Vulnerabilities:

Unpatched or outdated software means the opening of security gaps.

Impact: The other vulnerability to be exploited by attackers to gain unauthorized access and install malware on a target computer.

Literature Insights: One of the key issues affecting SMEs is always related to the lack of IT skills needed to provide frequent updates(Budde et al., 2023).

- 6.

- Supply Chain Attacks:

SMEs are regarded as the entry points in large organization networks.

Impact: Compromise of business partners and cascading vulnerabilities.

Literature Insights: There is growing concern as SMEs are considered the “weakest link” in supply chains.

- 7.

- Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attacks:

A condition in which a network or system is flooded with traffic until it becomes virtually inaccessible.

Impact: Loss of operating time and revenue.

Literature Insights: Small businesses, conversely, are ransomed to launch DDoS attacks because they cannot prevent them from happening.

- 8.

- IoT Vulnerabilities:

The security of IoT devices in SMEs is still relatively poor.

Impact: Cyber espionage and botnet development.

Literature Insights: As IoT adoption grows, so does the attack surface, with poorly secured devices being exploited (H. Alhakami, 2024; Shaffique, 2024).

- 9.

- Cloud Security Risks:

Misconfigurations and insufficient safeguards in cloud platforms.

Impact: Data exposure, service disruptions, and account hijacking.

Literature Insights: SMEs increasingly rely on cloud services but often overlook securing them properly.

- 10.

- Business Email Compromise (BEC):

Cybercriminals impersonate executives or trusted partners using compromised or fake email accounts to manipulate employees into transferring funds or sharing sensitive data.

Impact: Financial losses, reputation damage, operational disruptions, and legal consequences

Literature Insights: Limited resources, inadequate training, lack of cybersecurity infrastructure, third-party risks for each cybersecurity threat (CST), we calculate the “Impact Percentage (%)” and determine its “Importance for SMEs”. Below is the breakdown of the data:

i. Number of Threats (N): N = 10

ii. Total Impact Percentage: (Σ Impact Percentage)

Σ Impact Percentage = 30 + 25 + 15 + 20 + 10 + 15 + 18 + 12 + 8 + 14 = 167%

iii. Average Impact Percentage (μ):

μ = Σ Impact Percentage

N

N

μ = 167 = 16.7%

10

10

iv. Threat Categories by Importance for SMEs:

- High Importance: 5 threats (CST1, CST2, CST4, CST7)

- Medium Importance: 4 threat types (CST3, CST5, CST6, CST8, CST10)

- Low Importance: 1 threat (CST9)

v. Weighted analysis by importance level:

To better understand the distribution, we assign weights to importance levels:

- High Importance = 3

- Medium Importance = 2

- Low Importance = 1

Each threat-weighted contribution to impact is:

Weighted contribution = (Impact percentage) × (Weight)

To find out the relative figure of merit and distribution analysis based on Table 6, the total weighted contribution and then the relative merit of each entry was calculated.

Table 6.

Importance and weight of cybersecurity threats in SMEs.

- Step 1: Calculate the Total Weighted Contribution

Sum up all the Weighted Contributions from Table 7:

Total Weighted Contribution = 90 + 75 + 30 + 60 +20 + 30 + 54 + 24 + 8 + 28 = 419

Table 7.

Cybersecurity risks and practices for SMEs.

- Step 2: Calculate the Relative Figure of Merit for Every Code

The relative figure of merit for each CST code is then obtained by dividing the Weighted Contribution for a particular CST code by the Total Weighted Contribution and multiplying it by 100 to obtain a percentage:

Relative figure of merit = Weighted Contribution of each CST × 100

Total Weighted Contribution

Total Weighted Contribution

CST1: 21.5%

CST2: 17.9%

CST3: 7.2%

CST4: 14.3%

CST5: 4.8%

CST6: 7.2%

CST7: 12.9%

CST8: 5.7%

CST9: 1.9%

CST10: 6.7%

- Step 3: Distribution Analysis

To analyze the distribution, we perform the following calculations:

High Impact (CST1, CST2, CST4, CST7):

Total Weighted Contribution: 90 + 75 + 60 + 54 = 279

Relative Contribution of High Impact: 66.6%

Medium Impact (CST3, CST5, CST6, CST8, CST10):

Total Weighted Contribution: 30 + 20 + 30 + 24 + 28 = 132

Relative Contribution of Medium Impact: 31.5%

Low Impact (CST9):

Total Weighted Contribution: 8

Relative Contribution of Low Impact: 1.9%

From the above analysis, there is a clear dominance of “High Impact CSTs,” with “Medium Impact CSTs” being in the middle and “Low Impact CSTs” occupying the last positions.

4.3. Defensive Practices for Addressing Cybersecurity Threats That Impact SMEs

Defensive cybersecurity threats in SMEs are crucial as these organizations often face a disproportionate number of cyberattacks but lack the resources and expertise to manage sophisticated threats. According to a literature review, several best practices can help SMEs address cybersecurity, as presented in Table 7.

4.4. Research Methodologies, Approaches and Their Contribution to SMEs-Specific Cybersecurity Threats

Studying cybersecurity in SMEs requires specific research methodologies and approaches, as SMEs face unique challenges compared to larger organizations. The methods employed often address the resource constraints, limited expertise, and different risk environments that SMEs experience. Here are the predominant research methodologies and their contributions:

- Qualitative Research. (Fotis, 2024a; Ismail et al., 2024; Knight & Nurse, 2020; Nautiyal & Rashid, 2024; Waelchli & Walter, 2025)

Interviews and Case Studies: Researchers often conduct in-depth interviews with SME owners, IT managers, and employees to understand their cybersecurity practices, risk perceptions, and challenges. Case studies of specific SMEs or industry sectors also provide detailed insights into the decision-making processes and threat management in SMEs.

Contribution: This approach focuses on SME vulnerabilities like the absence of professional staff qualified in cybersecurity, constrained financial and recognition problems, and presents a more complex outlook on SME cybersecurity organizational culture and practices.

Focus Groups: Host a focus group of SME stakeholders (such as SME owners and professionals in IT and cybersecurity) for an open-air concern-sharing session.

Contribution: Furnishes an enhanced perspective of ongoing matters by other institutions and organizations about cybersecurity. Furthermore, it construes misconceptions or knowledge deficiencies that could be incurred in SMEs’ security plans.

- 2.

- Surveys and Quantitative Research. (Alqudhaibi et al., 2025; Ismail et al., 2024)

Surveys: Questionnaires are administered to SMEs in large numbers to collect information on perceptions of their cybersecurity, current trends, normal and abnormal security threats, and their preparedness. This typically comprises questions on the application of security technologies, security policies and security training of employees.

Contribution: Useful for understanding how often specific security equipment is utilized, how exposed small and medium businesses are, and the most typical cyberattack patterns. It also enables researchers to generalize the results of the study to the remaining SME population.

Statistical Analysis: This includes analyzing patterns in the frequency and types of cyberattacks experienced by SMEs, as well as assessing the effectiveness of specific cybersecurity strategies.

Contribution: Provides quantifiable insights into the relationship between cybersecurity practices and outcomes (e.g., breach rates, financial losses), allowing for evidence-based recommendations for SMEs.

- 3.

- Action Research. (Liang et al., 2023)

Action Research: In this methodology, researchers work directly with SMEs to help them implement cybersecurity improvements and assess the impact of these challenges. This involves iterative cycles of problem identification, intervention, and evaluation.

Contribution: This hands-on approach not only helps SMEs improve their cybersecurity practices but also provides actionable insights into the practical challenges they face in applying security measures. It bridges the gap between theory and real-world application.

- 4.

- Comparative Research. (Erbas et al., 2024)

Comparative Studies: Analysts make cross-sectional (between different sectors of SMEs, for instance, the healthcare and the retail sector(s)) or cross-country between SMEs and large firms’ comparison of cybersecurity measures.

Contribution: By comparing and distinguishing the cybersecurity strategies in the context of SMEs and other types of business entities, which involves the comparison of SMEs’ cybersecurity risks and cybersecurity risks in large companies or comparing cybersecurity risks within SMEs, the researcher is able to identify specific risks that SMEs are exposed to while doing business but may not necessarily be exposed to by large companies.

- 5.

- Cybersecurity Maturity Models. (Erbas et al., 2024; Nautiyal & Rashid, 2024)

Maturity Models: Various models are available to evaluate the cybersecurity level of SMEs. These models give SMEs an assessment of their cybersecurity condition on aspects such as policies, processes, technologies, and awareness.

Contribution: Maturity models help categorize SMEs based on their cybersecurity readiness and identify areas that need improvement. These models also enable researchers to benchmark cybersecurity practices against industry standards.

- 6.

- Scenario-based and Threat Modelling

Scenario-based Studies: These include conducting constructive as well as actual cyber threat simulation exercises that SMEs might encounter (like phishing, ransomware, insider threats).

Contribution: Enables SMEs to gain an understanding of the nature of threats likely to face their businesses and the effect of these threats. It enables the researchers to explain how SMEs are weak in the use of specific attack types.

Threat Modelling: Threat modelling is applied by researchers to determine threats, weaknesses and the consequences that are possible in case of a cyberattack in SMEs. Sometimes, this involved drawing a plan of what relates to IT and where the problematic areas are most likely to be found.

Contribution: Enables SMEs to gain a better insight into the threats they face and design a better cybersecurity approach, as well as find out about vulnerabilities that the SME would never have known were issues.

- 7.

- Longitudinal Studies. (Zhang & Malacaria, 2025)

Long-term Observational Studies: It is essential to capture the evolution of cybersecurity practices of SMEs over a long period to capture their dynamics regarding their security profile and experience new threats.

Contribution: Offers multidimensional analysis regarding the state and development of cybersecurity measures and how internal and external conditions influence SMEs’ cybersecurity approach and measures in the long run.

- 8.

- Behavioural Research. (Ismail et al., 2024; Kiran et al., 2025)

Human Factors Research: There are not enough acceptable works on the human angle of cybersecurity, such as employees’ behaviour, consciousness, and training. This might entail a desire to know how employees engage with phishing trials or receptiveness to security measures or policies.

Contribution: SMEs do not perform well when it comes to cybersecurity, and human error is ranked among the chief culprits. Analyzing behavioural patterns makes it easier to develop training, awareness, and other activities and policies that respond to these weaknesses.

- 9.

- Literature Reviews and Meta-Analysis. (Alqudhaibi et al., 2025; Fotis, 2024b; Jada & Mayayise, 2024)

Systematic Literature Reviews: Researchers aggregate and analyze existing studies on SME cybersecurity to identify trends, gaps, and best practices.

Contribution: This paper integrates the findings outlined across several different works to offer an overview of SME cybersecurity threats, approaches, and issues. This makes it easier to establish broad trends and even present a research-based set of conclusions.

- 10.

- Risk Assessment Frameworks. (Alqudhaibi et al., 2025; Knight & Nurse, 2020; Zhang & Malacaria, 2025)

Risk Analysis and Assessment: Using frameworks such as NIST, ISO 27001, or customized models, researchers assess the cybersecurity risks SMEs face based on their specific business context, size, and industry.

Contribution: These frameworks assist SMEs in risk recognition, evaluation, and ranking. Thus, SMEs can allocate more efforts to the protection of the areas which they are most sensitive to.

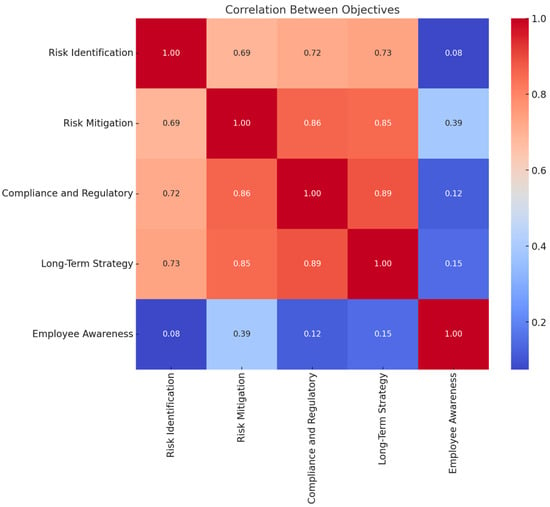

Table 8 presents research methodologies’ impact on SMEs’ basic objectives, such as Risk Identification, Risk Mitigation, Compliance and Regulatory, Long-Term Strategy, and Employee Awareness.

Table 8.

Research methodologies’ impact on SMEs’ basic objectives.

Figure 5 visualizes the correlation between the SMEs’ objectives. Correlation coefficients were calculated using Pearson’s correlation method to identify the strength and direction of relationships among the main variables. This approach follows standard statistical procedures described by Cohen and Pallant (Dufera et al., 2023; Sedgwick, 2012). The intensity of the colours and numerical values represents the strength and direction of these correlations, ranging from 1.0 (perfect positive correlation) to 0 (no correlation).

Figure 5.

Correlation between various SME Factors/Objectives.

Key Observations:

- Strong Positive Correlations:

There is a high correlation between Risk Mitigation and Compliance and Regulatory (0.86), as well as between Long-Term Strategy and Compliance and Regulatory (0.89). This suggests these objectives are strongly interconnected, likely because effective risk mitigation and regulatory compliance are foundational for long-term planning.

Risk Identification correlates significantly with both Compliance and Regulatory (0.72) and Long-Term Strategy (0.73), reflecting that recognizing risks is critical for maintaining compliance and ensuring sustainable strategies.

- 2.

- Moderate Positive Correlations:

Risk Mitigation has a notable correlation with Risk Identification (0.69) and Long-Term Strategy (0.85), indicating that managing risks supports broader strategic objectives.

- 3.

- Low OR Negligible Correlations:

Employee Awareness shows weak correlations with most other objectives:

- Risk Identification (0.08)

- Compliance and Regulatory (0.12)

- Long-Term Strategy (0.15)

This suggests that employee awareness initiatives are not strongly aligned with these strategic objectives in the dataset represented.

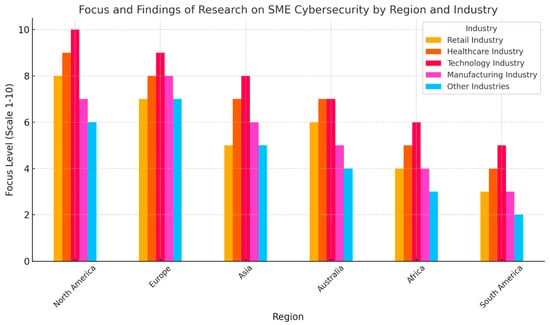

4.5. Focus and Research on SME Cybersecurity by Region and Industry

Figure 6 was developed based on a comprehensive literature review and data synthesis of previous studies on cybersecurity in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The data underlying this figure were derived from secondary sources, including peer-reviewed journal articles, industry reports, and conference proceedings published between 2015 and 2025.

Figure 6.

Focus and research findings on SME cybersecurity by region and industry.

Each region (North America, Europe, Asia, Australia, Africa, and South America) and industry category (Retail, Healthcare, Technology, Manufacturing, and Other Industries) was evaluated according to the relative research emphasis or focus level observed in the literature. The focus levels were quantified on a 1–10 scale, representing the extent to which each sector and region has been addressed in SME cybersecurity research:

- 1–3 indicates low research attention,

- 4–7 indicates moderate attention, and

- 8–10 indicates high attention.

Scores were computed through a frequency-weighted averaging method, where the number of studies focusing on each industry–region pair was counted and normalized to fit the 1–10 scale. This approach provided a comparative visualization of the intensity of academic and applied research focus across global regions and key industries.

Key Observations:

- Regional Trends:

- ○

- North America and Europe demonstrate the highest focus across all industries, indicating these regions lead in SME cybersecurity research.

- ○

- Asia shows strong research efforts, particularly in the Technology and Healthcare industries.

- ○

- Africa and South America exhibit comparatively lower levels of focus, with only modest efforts across industries.

- Industry-Specific Insights:

- ○

- The Technology Industry consistently receives the highest focus across all regions, reflecting its critical need for robust cybersecurity measures.

- ○

- The Healthcare Industry also receives significant attention, especially in North America and Europe, likely due to increased digitalization and regulatory requirements.

- ○

- Retail and Manufacturing industries see moderate levels of focus, with a stronger emphasis on developed regions.

- ○

- Other Industries, such as agriculture or small-scale services, tend to receive the least attention overall.

- Global Disparities:

- ○

- Developed regions (North America, Europe) show a more balanced and high-level focus

- ○

- across all industries, while developing areas (Africa, South America) lag, particularly in sectors outside of healthcare and technology.

Implications:

- ○

- Policymakers and researchers in developing regions should prioritize cybersecurity awareness and solutions in industries like Manufacturing and Retail to ensure equitable growth.

- ○

- Industries like Technology and Healthcare require sustained investment in cybersecurity due to their critical vulnerabilities.

- ○

- Collaboration between regions with advanced research (e.g., North America and Europe) and those with lower focus levels could help address global cybersecurity challenges.

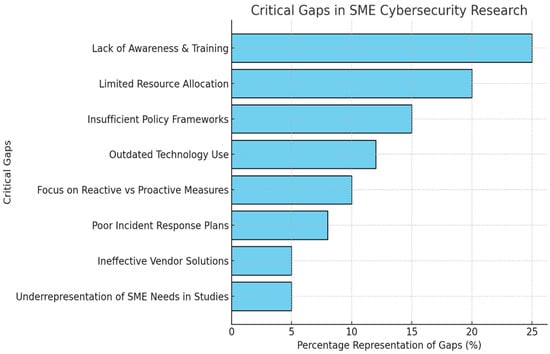

4.6. Critical Gaps in SMEs Cybersecurity Research

Figure 7 illustrates the critical gaps in SME cybersecurity research, categorized by key challenges and their percentage representation. The graph prioritizes gaps that require urgent attention, highlighting the areas where current research and practices fall short.

Figure 7.

Critical gaps in SME cybersecurity research.

Analysis:

- Lack of Awareness and Training (25%):

This is the most significant gap, indicating that SMEs lack sufficient knowledge about cybersecurity risks and best practices (Zhao et al., 2024). Employees and leadership often underestimate the impact of cyber threats, leading to vulnerabilities.

Training programmes and awareness campaigns are essential for equipping SMEs with the knowledge to identify, mitigate, and respond to threats (Burská et al., 2022).

- 2.

- Limited Resource Allocation (20%):

SMEs often lack the financial and human resources to invest in robust cybersecurity measures (Almahmoud et al., 2025). This gap reflects a need for cost-effective solutions tailored to SMEs, such as subsidized cybersecurity tools or government-funded initiatives.

- 3.

- Insufficient Policy Frameworks (15%):

Policies and regulatory frameworks designed explicitly for SMEs are inadequate (Toftegaard et al., 2024). Current policies often cater to larger enterprises, leaving SMEs without clear guidance or actionable compliance standards (McIntosh et al., 2023).

- 4.

- Outdated Technology Use (12%):

SMEs frequently rely on outdated software and hardware, which increases their exposure to cyber risks (Chidukwani et al., 2022). This is often due to budget constraints or a lack of understanding of modern technologies.

- 5.

- Focus on Reactive vs. Proactive Measures (10%):

Many SMEs only implement cybersecurity measures after experiencing an attack. This gap highlights the need for proactive strategies, such as regular risk assessments, penetration testing, and threat intelligence systems (Gunes et al., 2021).

- 6.

- Poor Incident Response Plans (8%):

SMEs often lack structured response plans for cybersecurity incidents (Geach, 2021). This can result in delayed recovery, financial losses, and damage to reputation after an attack.

- 7.

- Ineffective Vendor Solutions (5%):

Cybersecurity products and services are often designed for large organizations, making them unsuitable for SMEs (Naseer et al., 2021). Vendors need to develop scalable, affordable, and user-friendly solutions tailored to the unique needs of SMEs.

- 8.

- Underrepresentation of SME Needs in Studies (5%):

Research on Cybersecurity predominantly focuses on large enterprises, neglecting the specific challenges faced by SMEs (Medeiros et al., 2023). More studies are needed to understand their unique vulnerabilities and develop targeted strategies.

Implications:

- ○

- Prioritizing Awareness and Resources:

The graph highlights the importance of increasing awareness and resource allocation as the foundational steps to improve SME cybersecurity.

- ○

- Proactive vs. Reactive Approaches:

A shift in mindset from reactive to proactive measures is critical. SMEs must prioritize investments in preventive technologies and processes rather than waiting for breaches to occur.

- ○

- Customized Solutions for SMEs:

The gaps suggest that both policymakers and technology vendors need to address the unique requirements of SMEs. Tailored frameworks, cost-effective solutions, and specific research for SMEs can significantly reduce their cybersecurity risks.

- ○

- Collaboration Opportunities:

Collaboration between governments, the private sector, and research institutions could bridge these gaps. For example, partnerships could provide SMEs with subsidized access to cybersecurity training, tools, and incident response expertise.

The gaps identified in Figure 7 provide a roadmap for future research and action in SME cybersecurity. By addressing these critical challenges, the overall resilience of SMEs to cyber threats can be significantly improved.

5. Summary and Conclusions of the Study

This paper systematically identified cybersecurity threats to SMEs and assessed defensiveness strategies addressing their constraints and risks. The listed threat types included phishing, ransomware, insider threats, supply chain threats, denial of service (DoS), and other attacks. SMEs are most vulnerable to these threats because of the restricted funds, the lack of professional IT protection, and the insufficient defensive measures that were grouped into training interventions, endpoint protection tools, cloud services, network protection, and access-regulation regimes. Of all of them, the training option was found to be the most effective and the most recommended measure, especially for combating phishing and insider threats. At the same time, it is necessary to note deficiencies in the follow-up of the stated defensive measures’ uninterrupted application and long-term employment. Some of the observations made were that SMEs perhaps engage in reactive approaches to cybersecurity rather than planning appropriately for it. Therefore, the study finds that SME cybersecurity is a threat that requires a comprehensive response to counter. Mitigating measures like training, endpoint protection, and cloud-based solutions are important; all the aversion measures mentioned above are helpful and applicable, but they have constraints and a lower utilization priority.

To address these challenges, the study emphasizes the need for:

- Proactive Measures: Regarding cybersecurity, businesses should transform from simply responding to threats to a more strategic approach to the problem that includes constant risk analysis and future planning.

- Sustainability of Training Programmes: This is why awareness must be constant and frequently reinforced through the culture set up in the company.

- Resource Optimization: SMEs can, therefore, improve the security of their organizations by building on affordable solutions and adopting threat intelligence sharing services from the cloud across organizations at a fractional cost of exclusive control solutions.

- Policy and Vendor Collaboration: Leaders in government and technology industries should, therefore, offer policies and products that will enhance the cybersecurity frameworks in SMEs.

The results should prove useful to policymakers, academics, and SMEs to formulate prevention and management measures. The future research direction in the subject area is to investigate the viability of AI-based solutions, the influence of governmental incentives on SMEs, and the effects of international cybersecurity standards on the SME sector. By addressing these areas, the SMEs would be better placed to overcome challenges that come with the cyberspace environment.

6. Implication of the Study

The findings from this SMS of cybersecurity threats and defensive approaches for SMEs present several significant implications:

- Enhanced Awareness of Threat Landscape: This paper for SMEs summarizes the current top-level threats that this sector faces in terms of cybersecurity. Because SMEs are aware of the kind of threats and threat vectors that dominate their environment while operating, they can allocate resources and attention appropriately.

- Guidance for Resource Allocation: Since most SMEs operate under tightly controlled financial and technical resource environments, these mapped-out defensive strategies can point to where to deploy these scarce resources. The threats identified make it easier for SMEs to concentrate on cost-efficient solutions that can provide adequate security to the companies.

- Policy and Training Development: The research findings can help policymakers and industry regulators to launch the relevant programmes and policies, such as cybersecurity training and local regulatory frameworks, that address the significant hurdles to SMEs. This could motivate the adoption of the proper practices and technologies at various political stages.

- Foundation for Future Research: The discussed SMS is the prerequisite for future research on SME cybersecurity. The breakdown of the issues highlighted in the case allows the researchers to find out the directions in which new technologies and methodologies can be applied to mitigate specific risks in SMEs.

- Customized Cybersecurity Solutions: Most of the existing works call for the development of more generalized as well as more organization-specific security solutions that are more appropriate for SMEs. Businesses with limited technological expertise may adopt these findings to potentially develop cost-effective tools and services that are simple to implement using available software tools.

- Collaborative Cybersecurity Ecosystem: The benefits are not limited to promoting cooperation between SMEs and large companies and cybersecurity service providers. This approach suggests that the development of a mutual threat database and synchronized defensive measures can help SMEs increase their overall security levels.

- Encouragement for Cybersecurity Investment: This study makes the need for proper cybersecurity infrastructure investments transparent by providing examples of how cybersecurity breaches can affect an organization. It can be used as an argument for SME leadership to put their money where their protection is.

- Benchmarking and Standards: The SMS is helpful as it paints a picture of the state of the identified best practice that an SME has implemented to determine its cybersecurity posture. It also creates a foundation of best practices for the growth of field-specific cybersecurity benchmarks and policies.

- Impact on SME Competitiveness: When SMEs implement better cybersecurity, they reduce their risk of threats while, at the same time, creating more credibility in the market. It can give competitive advantages in fields that require data security for clients and partners because of its nature.

- Long-term Sustainability: Considering the study, the timely implementation of defensive measures explained above guarantees long-term functional flexibility to SMEs, reducing risks of financial and reputational loss due to cyber threats.

When these implications are taken as a means of implementing policies and activities, they will help stakeholders improve SMEs’ cybersecurity position and protect their jobs within the global economy.

7. Limitations of the Study

This SMS clarifies the state of the cybersecurity threats and countermeasures for SMEs at present. However, several limitations, which in some ways are self-imposed, need to be highlighted to situate the present research and its results properly.

- Scope of Data Sources: The study mainly depended on scholarly articles, business materials, and data accessible to the public. Although these sources present strong and reliable information, some of the practices and threats faced might not be fully reflected, particularly in minority sectors of SMEs or some geographic areas.

- Publication Bias: The inclusion of rich sources of published documents poses the danger of publication bias into the equation. A large number of positive research results or remarkable cases of work may be published, which may distort the picture of adequate protective measures or the share of threats.

- Generalizability: This SMS is primarily directed at the SME and its maturing cybersecurity concerns and guard mechanisms. It is also important to note that although some of the findings may refer to larger organizations or other sectors, the results are specific to the SME population and should not be generalized outside of this setting.

- Methodological Constraints: Despite this, the SMS process entails rigorous activity, which ultimately limits it owing to the selection criteria and frameworks in question. As a result of comparing the proposed empirical criteria, some relevant studies or other innovative approaches might have been filtered out because of poor fit.

- Rapid Evolution of Threats and Defensive Approaches: This sort of threat and activity changes frequently, so commemorative defensive strategies are a necessity. The very characteristic of an SMS is static, which means it trails real-life developments in the field.

Mitigating these limitations in future research will ensure that there is a better appreciation of the cybersecurity issues facing SMEs, as well as enhance the creation of effective protective mechanisms. First, future research could use a broader range of source data to support this type of analysis; second, it could add actual verification to the proposed models. Finally, future research could expand the investigations of the specific sector and the region, and analyze the difficulties that relate to it in view of the outcomes provided by this work.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/admsci15120481/s1. Table S1: Checklist for compliance with the review based on the PRISMA method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and A.A.; methodology, M.A.; software, M.A.; validation, M.A., A.A.; formal analysis, M.A.; investigation, M.A.; resources, M.A.; data curation, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A.; visualization, M.A.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, M.A.; funding acquisition, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al Aamer, A. K., & Hamdan, A. (2023). Cyber security awareness and SMEs’ profitability and continuity: Literature review (pp. 593–604). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Alahmari, A., & Duncan, B. (2020, June 15–17). Cybersecurity risk management in small and medium-sized enterprises: A systematic review of recent evidence. 2020 International Conference on Cyber Situational Awareness, Data Analytics and Assessment (CyberSA) (pp. 1–5), Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- AlDaajeh, S., & Alrabaee, S. (2024). Strategic cybersecurity. Computers & Security, 141, 103845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dalati, I. (2023). Digital twins and cybersecurity in healthcare systems. In Digital twin for healthcare (pp. 195–221). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alhakami, H. (2024). Enhancing IoT security: Quantum-level resilience against threats. Computers, Materials & Continua, 78(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhakami, W. (2024). Enhancing cybersecurity competency in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A fuzzy decision-making approach. Computers, Materials & Continua, 79(2), 3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahmoud, Z., Yoo, P. D., Damiani, E., Choo, K. K. R., & Yeun, C. Y. (2025). Forecasting cyber threats and pertinent mitigation technologies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 210, 123836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudhaibi, A., Albarrak, M., Jagtap, S., Williams, N., & Salonitis, K. (2025). Securing industry 4.0: Assessing cybersecurity challenges and proposing strategies for manufacturing management. Cyber Security and Applications, 3, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M., Maximiano, M., & Gomes, R. (2022). A customizable web platform to manage standards compliance of information security and cybersecurity auditing. Procedia Computer Science, 196, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyabe, M. F., Arranz, C. F. A., De Arroyabe, I. F., & de Arroyabe, J. C. F. (2024a). Revealing the realities of cybercrime in small and medium enterprises: Understanding fear and taxonomic perspectives. Computers & Security, 141, 103826. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyabe, M. F., Arranz, C. F. A., Fernandez De Arroyabe, I., & Fernandez de Arroyabe, J. C. (2024b). Exploring the economic role of cybersecurity in SMEs: A case study of the UK. Technology in Society, 78, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuran, R., Vykopal, J., Belajová, D., Čeleda, P., Tan, Y., & Shinoda, Y. (2023). Capability assessment methodology and comparative analysis of cybersecurity training platforms. Computers & Security, 128, 103120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budde, C. E., Karinsalo, A., Vidor, S., Salonen, J., & Massacci, F. (2023). CSEC+ framework assessment dataset: Expert evaluations of cybersecurity skills for job profiles in Europe. Data in Brief, 48, 109285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S. M. S., Zafar, M. H., Abou Houran, M., Qadir, Z., Moosavi, S. K. R., & Sanfilippo, F. (2024). Enhancing cybersecurity in Edge IIoT networks: An asynchronous federated learning approach with a deep hybrid detection model. Internet of Things, 27, 101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burská, K. D., Rusňák, V., & Ošlejšek, R. (2022). Data-driven insight into the puzzle-based cybersecurity training. Computers & Graphics, 102, 441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, J., Sharma, P., Jantunen, E., Baglee, D., & Fumagalli, L. (2016). The challenges of cybersecurity frameworks to protect data required for the development of advanced maintenance. Procedia Cirp, 47, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, Y. H., Lee, C., Choi, M. K., & Seong, P. H. (2022). Evaluating attractiveness of cyberattack path using resistance concept and page-rank algorithm. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 166, 108748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S., Gkioulos, V., & Katsikas, S. (2023). A quest for research and knowledge gaps in cybersecurity awareness for small and medium-sized enterprises. Computer Science Review, 50, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A., Behera, R. K., & Bala, P. K. (2025). Factors impacting cybersecurity transformation: An Industry 5.0 perspective. Computers & Security, 150, 104267. [Google Scholar]

- Chidukwani, A., Zander, S., & Koutsakis, P. (2022). A survey on the cyber security of small-to-medium businesses: Challenges, research focus and recommendations. IEEE Access, 10, 85701–85719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidukwani, A., Zander, S., & Koutsakis, P. (2024). Cybersecurity preparedness of small-to-medium businesses: A Western Australia study with broader implications. Computers & Security, 145, 104026. [Google Scholar]

- Daim, T., Yalcin, H., Mermoud, A., & Mulder, V. (2024). Exploring cybertechnology standards through bibliometrics: Case of national institute of standards and technology. World Patent Information, 77, 102278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M., Taveras, P., & Taylor, D. (2019). Applying software assurance and cybersecurity nice job tasks through secure software engineering labs. Procedia Computer Science, 164, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cassai, A., Dost, B., Tulgar, S., & Boscolo, A. (2025). Methodological standards for conducting high-quality systematic reviews. Biology, 14(8), 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., Wu, Z., Tan, Z., & Jiang, X. (2021). Research and application of security baseline in business information system. Procedia Computer Science, 183, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenna, A., Belaoued, M., Lifa, N., & Moualdi, D. E. (2024). PARCA: Proactive anti-ransomware cybersecurity approach. Procedia Computer Science, 238, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufera, A. G., Liu, T., & Xu, J. (2023). Regression models of Pearson correlation coefficient. Statistical Theory and Related Fields, 7(2), 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbas, M., Khalil, S. M., & Tsiopoulos, L. (2024). Systematic literature review of threat modeling and risk assessment in ship cybersecurity. Ocean Engineering, 306, 118059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, G., Halvorsrud, R., Boletsis, C., Tverdal, S., & Pickering, J. B. (2023, February 22–24). Cybersecurity awareness and capacities of SMEs. 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2023) (pp. 296–304), Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Fotis, F. (2024a). Cyberattacks: Economic Impacts and Risk Management Strategies. Procedia Computer Science, 251, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotis, F. (2024b). Economic impact of cyber attacks and effective cyber risk management strategies: A light literature review and case study analysis. Procedia Computer Science, 251, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furfaro, A., Piccolo, A., Parise, A., Argento, L., & Saccà, D. (2018). A Cloud-based platform for the emulation of complex cybersecurity scenarios. Future Generation Computer Systems, 89, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geach, D. (2021). Grid cyber security: Secure by design, continuous threat monitoring, effective incident response and board oversight. Network Security, 2021(6), 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, B., Kayisoglu, G., & Bolat, P. (2021). Cyber security risk assessment for seaports: A case study of a container port. Computers & Security, 103, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N., & Hasan, M. (2024). The impacts of cyberattack on SMEs in the USA and way to accelerate cybersecurity. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 11(10), 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M., Madathil, N. T., Alalawi, M., Alrabaee, S., Al Bataineh, M., Melhem, S., & Mouheb, D. (2024). Cybersecurity activities for education and curriculum design: A survey. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 16, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jada, I., & Mayayise, T. O. (2024). The impact of artificial intelligence on organisational cyber security: An outcome of a systematic literature review. Data and Information Management, 8(2), 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, C. R., Becker, I., & Johnson, S. (2023). Unaware, unfunded and uneducated: A systematic review of SME cybersecurity (Vol. Abs/2309.17186). CoRR.

- Khan, R. A., Khan, S. U., & Ilyas, M. (2022). Exploring security procedures in secure software engineering: A systematic mapping study. The International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, 2022, 433–439. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R. A., Khan, S. U., Khan, H. U., & Ilyas, M. (2021). Systematic mapping study on security approaches in secure software engineering. IEEE Access, 9, 19139–19160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, U., Khan, N. F., Murtaza, H., Farooq, A., & Pirkkalainen, H. (2025). Explanatory and predictive modeling of cybersecurity behaviors using protection motivation theory. Computers & Security, 149, 104204. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, R., & Nurse, J. R. (2020). A framework for effective corporate communication after cyber security incidents. Computers & Security, 99, 102036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S., Farooq, A., Tenhunen, H., Pitkamaki, T., Hakkala, A., & Airola, A. (2020, July 6–9). AI in cybersecurity education—A systematic literature review of studies on cybersecurity MOOCs. 2020 IEEE 20th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT) (pp. 6–10), Tartu, Estonia. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X., Konstantinou, C., Shetty, S., Bandara, E., & Sun, R. (2023). Decentralizing cyber physical systems for resilience: An innovative case study from a cybersecurity perspective. Computers & Security, 124, 102953. [Google Scholar]

- Mantha, B., de Soto, B. G., & Karri, R. (2021). Cyber security threat modeling in the AEC industry: An example for the commissioning of the built environment. Sustainable Cities and Society, 66, 102682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C., Rajarajan, M., Arvanitis, K. G., & Vatsanidou, A. (2024). Cybersecurity threats and mitigation measures in agriculture 4.0 and 5.0. Smart Agricultural Technology, 9, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, T., Liu, T., Susnjak, T., Alavizadeh, H., Ng, A., Nowrozy, R., & Watters, P. (2023). Harnessing GPT-4 for generation of cybersecurity GRC policies: A focus on ransomware attack mitigation. Computers & Security, 134, 103424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, N., Ivaki, N., Costa, P., & Vieira, M. (2023). Trustworthiness models to categorize and prioritize code for security improvement. Journal of Systems and Software, 198, 111621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmango, N., & Gundu, T. (2023, November 16–17). Cyber resilience in the entrepreneurial environment: A framework for enhancing cybersecurity awareness in SMEs. 2023 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies (ICECET) (pp. 1–6), Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Moneva, A., & Leukfeldt, R. (2023). Insider threats among Dutch SMEs: Nature and extent of incidents, and cyber security measures. Journal of Criminology, 56(4), 416–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, M., Saraswat, M., & Sharma, P. K. (2024). Enhancing cybersecurity: A review and comparative analysis of convolutional neural network approaches for detecting URL-based phishing attacks. E-Prime—Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy, 8, 100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, A., Naseer, H., Ahmad, A., Maynard, S. B., & Siddiqui, A. M. (2021). Real-time analytics, incident response process agility and enterprise cybersecurity performance: A contingent resource-based analysis. International Journal of Information Management, 59, 102334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, L., & Rashid, A. (2024). A framework for mapping organisational workforce knowledge profile in cyber security. Computers & Security, 145, 103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, C., Casolari, F., Hacker, P., Spedicato, G., & Floridi, L. (2024). Generative AI in EU law: Liability, privacy, intellectual property, and cybersecurity. Computer Law & Security Review, 55, 106066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., & Chou, R. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K., Feldt, R., Mujtaba, S., & Mattsson, M. (2008, June 26–27). Systematic mapping studies in software engineering. 12th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering (EASE), Bari, Italy. [Google Scholar]