E-Government/AI Integration State and Capacity in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the current state of e-government/AI integration in developing countries?

- What are the critical strengths and factors in e-government/AI integration?

- What framework could guide e-government/AI integration in developing countries?

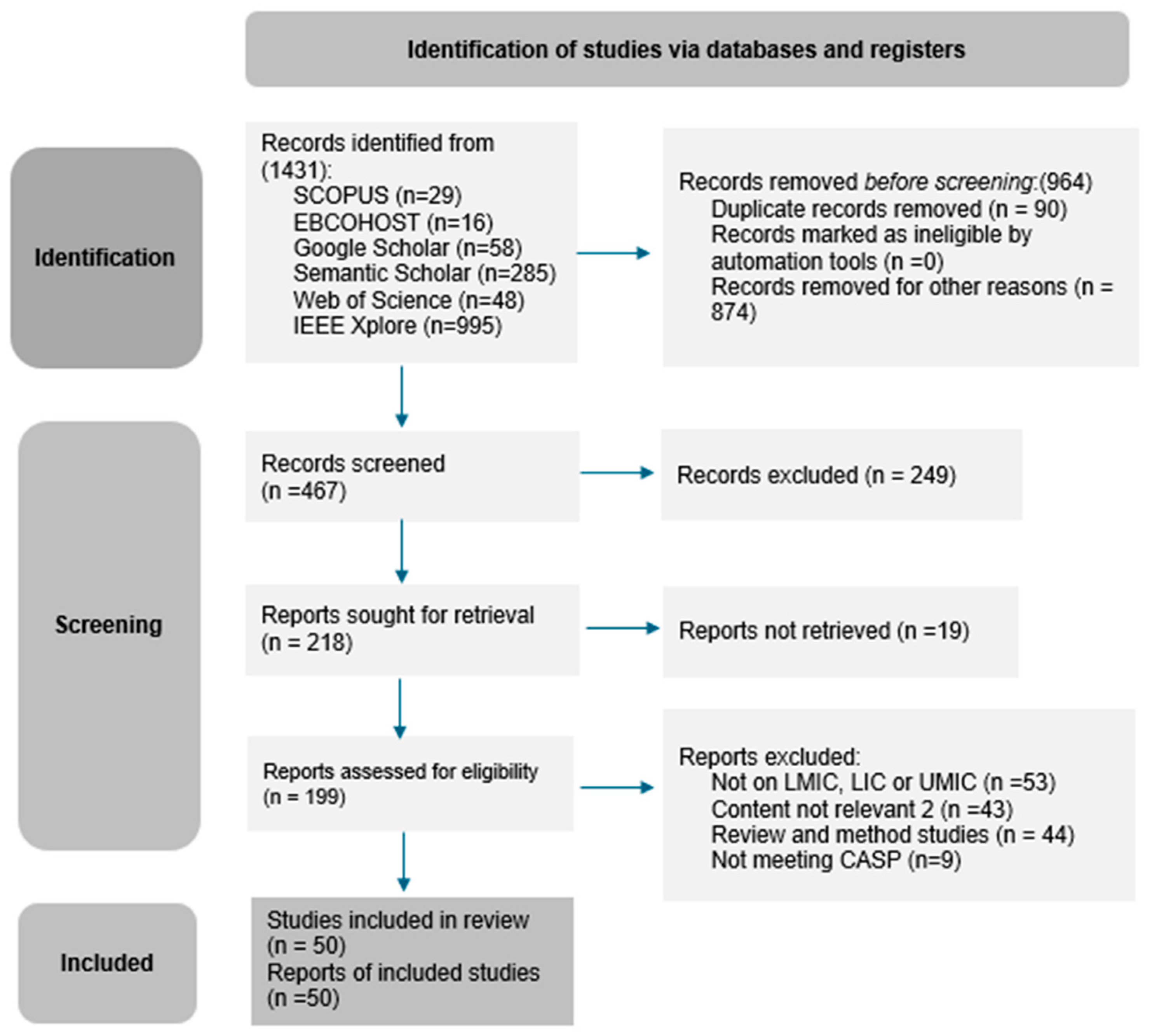

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

e-government OR digital government OR online government OR government-to-business OR smart government OR G2B AND artificial intelligence OR AI

Allintitle (Google Scholar): “e-government” AND “artificial intelligence”

e-government AND “artificial intelligence (will all system available synonyms enabled)

Full Text & Metadata: e-government) AND (“Full Text & Metadata”: artificial intelligence

E-Government OR digital government OR e-governance OR digital governance OR digital public services OR government digital services OR smart governance OR government-as-a-platform OR digital transformation OR digital public service delivery OR e-services AND artificial intelligence OR AI OR machine learning OR deep learning OR generative AI OR large language models OR natural language processing OR AI algorithms OR intelligent systems OR cognitive computing OR AI techniques OR AI models OR AI tools OR AI capabilities OR AI solutions OR AI technology OR chatbots OR bots

2.4. Data Charting

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Data Evaluation

2.7. Protocol Registration

3. Results

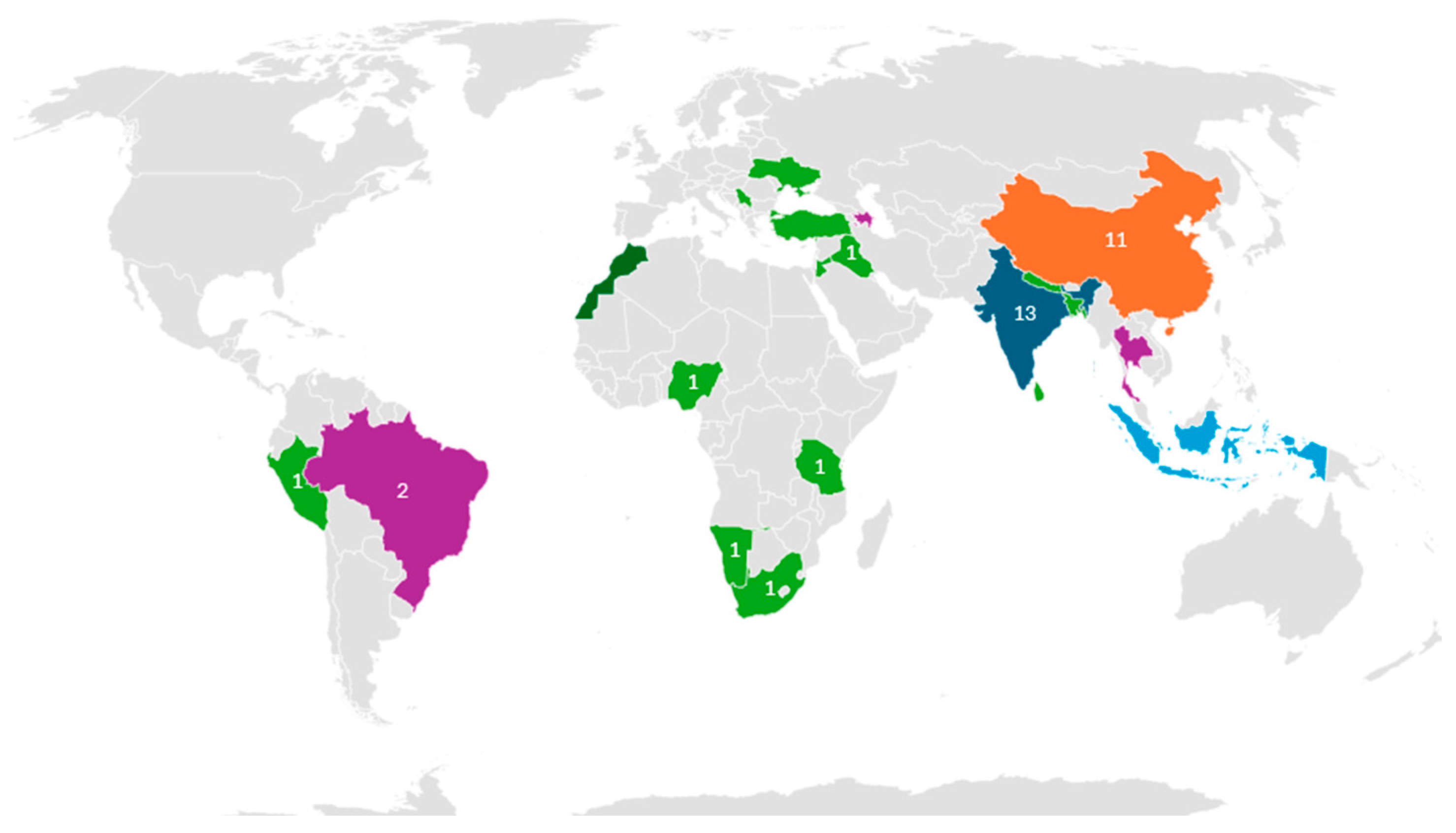

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

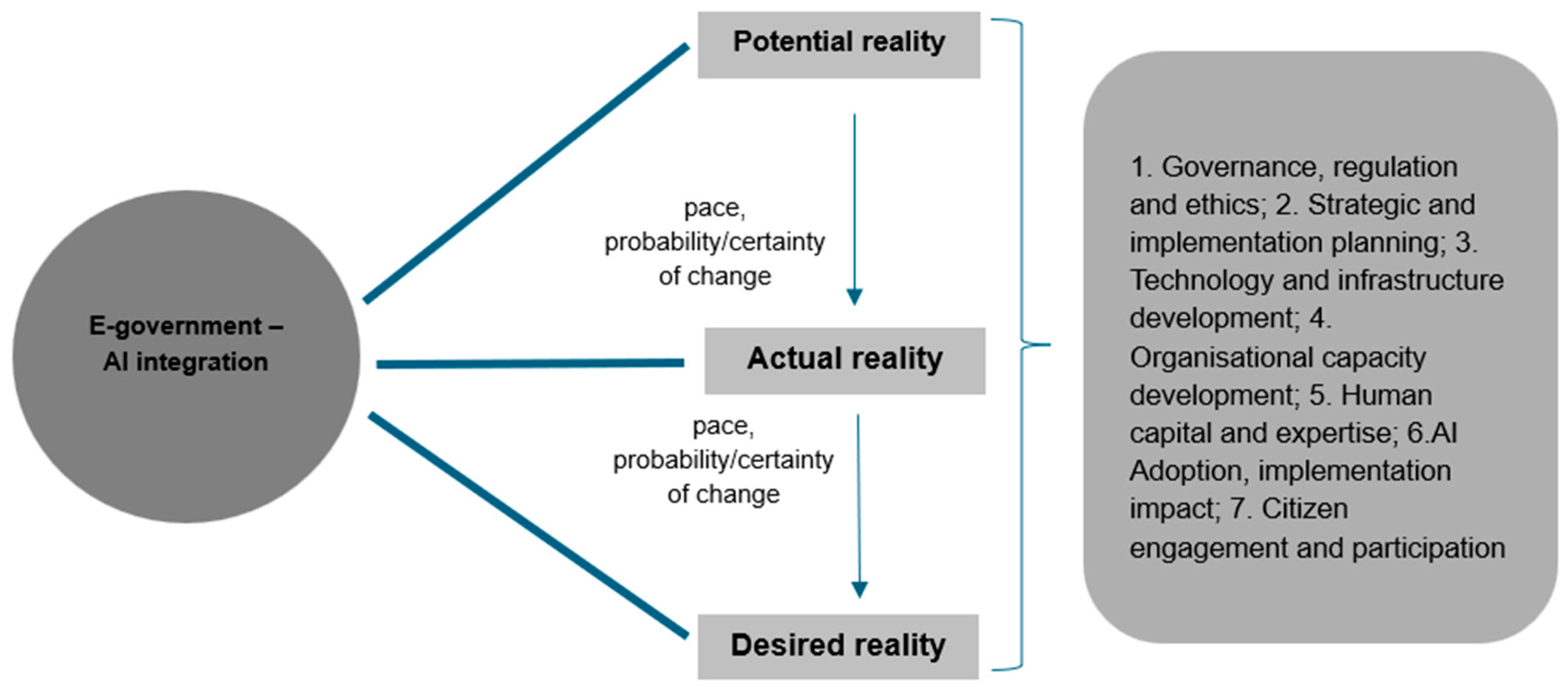

3.2. Theme 1: The Current Realities in E-Government AI Integration

3.2.1. E-Government/AI Integration Benefits as a Potential Reality

3.2.2. E-Government/AI Integration Benefits as an Actual Reality

3.3. Theme 2: Benefits and Opportunities in the Desired Reality

3.4. Theme 3: Strengths and Capabilities for the Desired State

3.4.1. Governance, Regulation and Ethics

3.4.2. Strategic and Implementation Planning

3.4.3. Technology and Infrastructure Development

3.4.4. Organisational Capacity Development

3.4.5. Human Capital and Expertise

3.4.6. AI Adoption, Implementation, and Impact

3.4.7. Citizen Engagement and Participation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| G2B | Government to Business |

| G2C | Government to Citizen |

| G2G | Government to Government |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| UNDESA | United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs |

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Authors | Country | Aim/Focus/Purpose | E-Government Focus | AI Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdulkareem (2024) | Nigeria | Examines generative AI’s potential for boosting civic participation in Nigeria | G2C | Generative AI |

| Alqudah et al. (2024) | Azerbaijan | Determines AI’s impact on user confidence and government service quality | G2C | General AI |

| Efe (2023) | Turkey | Analyses AI potential and evaluates risks for new ethics principles | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Suhendarto (2025) | Indonesia | Analyses AI integration to strengthen local governance and participation | G2C | General AI |

| Ajay et al. (2024) | India | Examines blockchain’s potential for e-governance in smart cities | General/Strategic | AI-Blockchain |

| Barodi and Lalaoui (2023) | Morocco | Highlights Morocco’s imperative to overcome digital transformation challenges | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Cheng et al. (2021) | China | Explores AI’s pros and cons via pandemic case studies | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Chinnapareddy et al. (2025) | India | Introduces an AI-driven framework to automate e-government services | G2C | Process Automation |

| Chinnasamy et al. (2023) | India | Advances e-government services using reliable AI approaches | G2C | General AI |

| Chiranjeevi et al. (2024) | India | Proposes a chatbot for explaining government welfare schemes | G2C | Chatbot |

| Essabbar et al. (2024) | Morocco | Evaluates open data initiatives in Morocco | G2G (Government) | Data Analytics |

| Fang and Xu (2023) | China | Develops an LLM-based system for answering citizen inquiries | G2C | Chatbot |

| Garcia-Carrera et al. (2025) | Peru | Describes how AI tools are changing public management | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Ji et al. (2024) | China | Focuses on the government data governance system | G2G (Government) | Data Analytics |

| Herdhiyanto et al. (2023) | Indonesia | Evaluates AI readiness in Indonesian ministries | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Jirari et al. (2025) | Morocco | Investigates AI’s contribution to managing Moroccan public schools | G2G (Government) | Data Analytics |

| Krishna et al. (2023) | India | Provides an integrative overview of AI’s public sector applications | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Nawafleh et al. (2025) | Jordan | Examines AI’s impact on improving e-government service efficiency | G2C | General AI |

| Osakwe et al. (2021) | Namibia (focus on African) | Calls attention to AI’s benefits for the public sector | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Ramathilagam et al. (2024) | India | Discusses a chatbot for bridging government information gaps | G2C | Chatbot |

| Syahidi et al. (2025) | Thailand | Presents a GPT-4-based system for citizen services | G2C | Generative AI |

| Mohammed et al. (2022) | Iraqi | Investigates machine learning effects on e-governance in Iraq | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Tamilarasi et al. (2024) | India | Identifies obstacles to cloud computing in e-government | General/Strategic | Other Tech (Cloud) |

| Xavier (2023) | Brazil | Reviews the natural language processing and machine learning project for monitoring government gazettes | G2G (Government) | NLP/Document Intelligence |

| Bakhov et al. (2025) | Ukraine | Analyses AI trends for the digital transformation of local government | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Jha and Jha (2024) | Nepal | Explores AI integration into e-governance cybersecurity | General/Strategic | AI & Security |

| Plantinga (2024) | South Africa | Synthesises findings from digital government in Africa and considers the implications for AI use | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Y. Zhang and Li (2025) | China | Examines AI’s impact on government services in Chinese cities | G2C | General AI |

| Alqudah et al. (2021) | Azerbaijan | Identifies AI applications for supporting administrative decisions | G2G (Government) | Data Analytics |

| Febiandini and Sony (2023) | India | Assesses AI preparedness in the Indonesian government | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Hasan et al. (2021) | India | Presents a conversational assistant for government services | G2C | Chatbot |

| Ishengoma et al. (2022) | Tanzania | Creates a modular framework for AIoT in the public sector | General/Strategic | AI and Infrastructure |

| Mazumder and Hossain (2024) | Bangladesh | Explores the AI Hub concept for enhancing citizen services | G2C | General AI |

| Srivastava and Sharma (2025) | India | Examines AI’s role in improving transparency in India | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Aminah and Saksono (2021) | Indonesia | Recommends digital transformation strategies for Indonesian e-government | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Arora et al. (2024) | India | Investigates AI integration for data-driven policy making | G2G (Government) | Data Analytics |

| Chatterjee et al. (2022) | India | Examines AI’s impact on public service performance and satisfaction | G2C | General AI |

| El El Gharbaoui et al. (2024) | Morocco | Investigates AI-chatbot effects on citizen satisfaction in Morocco | G2C | Chatbot |

| Elisa et al. (2023) | Thailand | Proposes a decentralised e-government framework with threat detection | General/Strategic | AI & Security |

| Li et al. (2025) | China | Develop an understanding of how AI creates public value in local governance | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Rathnayake et al. (2025) | Sri Lanka | Investigates AI-chatbot acceptance factors in developing countries | G2C | Chatbot |

| Song et al. (2025) | China | Compares citizen trust in human versus AI-delivered services | G2C | General AI |

| Spalević et al. (2023) | Serbia | Examines AI utilisation within the e-government realm | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Tueiv and Schmitz (2023) | Brazil | Creates a method for optimising chatbot value in e-government | G2C | Chatbot |

| S. Wang et al. (2024) | China | Analyses global factors influencing government AI adoption | General/Strategic | General AI |

| C. Wang et al. (2021) | China | Develop an understanding of how AI’s dual role in creating public value | General/Strategic | General AI |

| W. Zhang et al. (2021) | China | Summarises factors influencing the Chinese government’s use of AI | General/Strategic | General AI |

| Zhao et al. (2025) | China | Shows how AI technology enhances government transparency | General/Strategic | General AI |

| M. Zhou et al. (2025a) | China | Investigates how interaction type influences e-participation intention | G2C | General AI |

| Z. Zhou et al. (2025b) | India | Analyses factors influencing government adoption of Generative AI | General/Strategic | Generative AI |

References

- Abdulkareem, A. K. (2024). E-government in Nigeria: Can generative AI serve as a tool for civic engagement? Public Governance, Administration and Finances Law Review, 9(1), 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajay, N., Shrihari, M. R., Suchitra, K. S., Usha, B. S., Nandini, V., & Vandana, S. R. (2024, April 18–19). Development of e-governance services in smart cities using artificial intelligence and blockchain [Conference paper]. International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Communication Systems (ICKECS), Chikkaballapur, India. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, B. (2025). Integrating AI, blockchain, and cloud computing for enhanced e-government solutions. In Harnessing AI, blockchain, and cloud computing for enhanced e-government services (pp. 331–370). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Alqudah, M. A., Muradkhanli, L., & Abuhashish, M. (2024). Implementation of artificial intelligence by using amazon web services to improve services in e-government. Problems of Information Society, 15(2), 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, M. A., Muradkhanli, L., & Al-Awasa, M. (2021). Artificial intelligence applications that support: Business organizations and e-government in administrative decision. International Journal on Economics, Finance and Sustainable Development, 2(6), 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminah, S., & Saksono, H. (2021). Digital transformation of the government: A case study in Indonesia. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication, 37(2), 272–288. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, A., Vats, P., Tomer, N., Kaur, R., Saini, A. K., Shekhawat, S. S., & Roopak, M. (2024, August 11–12). Data-driven decision support systems in e-governance: Leveraging ai for policymaking [Conference paper]. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence on Textile and Apparel, Bangalore, India. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhov, I., Niema, O., Kravchenko, T., Borysenko, O., Kuspliak, I., & Zayats, D. (2025). Local self-government digital transformation in the context of sustainable development: Potential of artificial intelligence. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 6(2), e25019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barodi, M., & Lalaoui, S. (2023, October 5–6). Moroccan public administration in the era of artificial intelligence: What challenges to overcome? [Conference paper]. International Conference on Optimization and Applications (ICOA), AbuDhabi, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar]

- Bawole, J. N., Mensah, J. K., & Amegavi, G. B. (2019). Public service motivation scholarship in Africa: A systematic review and research agenda. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(6), 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., Khorana, S., & Kizgin, H. (2022). Harnessing the potential of artificial intelligence to foster citizens’ satisfaction: An empirical study on India. Government Information Quarterly, 39(4), 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., Luo, H., Lin, W., & Hu, G. (2021, June 18–20). Pros and cons of artificial intelligence—Lessons from e-government services in the COVID-19 pandemic [Conference paper]. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Education (ICAIE), Chengdu, China. [Google Scholar]

- Chinnapareddy, S. V., Gangisetty, V., & Sabat, N. K. (2025, January 10–12). AI-powered framework for enhancing e-government service automation [Conference paper]. International Conference on Innovations in Intelligent Systems: Advancements in Computing, Communication, and Cybersecurity (ISAC3), Bhubaneswar, India. [Google Scholar]

- Chinnasamy, P., Tejaswini, D., Dhanasekaran, S., Ramprathap, K., Lakshmi Priya, K., & Kiran, A. (2023, January 23–25). E-governance services using artificial intelligence techniques [Conference paper]. International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), Coimbatore, India. [Google Scholar]

- Chiranjeevi, V. R., Senthil, P. S., Keerthana, H., Abhignya, P., Rajendiran, M., Priyadharshini, S., Sanjay, S., Santhosh, R., Sharan, S., Subiksha, S., Sujith, S., Tharun, V., Tharunika, S., Udhayakumar, S., Vaishnavi, V., Varsha, S., Vasanth, K., Venkatasalam, M., Vijay, A., … Yazhini, M. (2024, July 10–12). Chatbot for government schemes using SEQ2SEQ model [Conference paper]. International Conference on Advances in Information Technology (ICAIT), Bangkok, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Demaidi, M. N. (2025). Artificial intelligence national strategy in a developing country. AI & Society, 40(2), 423–435. [Google Scholar]

- Efe, A. (2023). An evaluation on the relationship of Society 5.0, e-government applications and artificial intelligence. Medeniyet ve Toplum Dergisi, 7(2), 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- El El Gharbaoui, O., El Boukhari, H., & Salmi, A. (2024). Chatbots and citizen satisfaction: Examining the role of trust in ai-chatbots as a moderating variable. TEM Journal, 13(3), 1825–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisa, N., Yang, L., Chao, F., Naik, N., & Boongoen, T. (2023). A secure and privacy-preserving e-government framework using blockchain and artificial immunity. IEEE Access, 11, 8773–8789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essabbar, D., Chadli, S. Y., & Remmach, H. (2024, June 24–26). Evaluating government open data in Morocco for the advancement of artificial intelligence development [Conference paper]. International Conference on Global Aeronautical Engineering and Satellite Technology (GAST), Marrakesh, Morocco. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, K., & Xu, K. (2023, November 24–26). Automating government response to citizens’ questions: A large language model-based question-answering guidance generation system [Conference paper]. International Conference on Digital Society and Intelligent Systems (DSInS), Bangkok, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Febiandini, V. V., & Sony, M. S. (2023). Analysis of public administration challenges in the development of artificial intelligence Industry 4.0. IAIC Transactions on Sustainable Digital Innovation, 4(2), 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Carrera, P., Bernardo, G., Fuentes-Calcino, A., & Auccahuasi, W. (2025, March 15–17). Application of artificial intelligence in public management processes [Conference paper]. International Conference on Sentiment Analysis and Deep Learning (ICSADL), Lima, Peru. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, E. S., Shao, S., Shi, Q., & Arinaitwe, M. (2025). Applying artificial intelligence in software development education. Engineering Proceedings, 92(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, M., Hamidi, M. S., Miskinyar, M. S., & Sazish, B. (2023). Integrating artificial intelligence into e-government: Navigating challenges, opportunities, and policy implications. International Journal of Academic and Practical Research, 2(2), 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, I., Rizvi, S., Jain, S., & Huria, S. (2021, March 17–19). The AI enabled chatbot framework for intelligent citizen-government interaction for delivery of services [Conference paper]. 8th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development, New Delhi, India. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, H., Silva, E. S., Unger, S., TajMazinani, M., & Mac Feely, S. (2020). Artificial Intelligence (AI) or Intelligence Augmentation (IA): What is the future? AI, 1(2), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdhiyanto, A. D., Wirawan, & Rachmadi, R. F. (2023, July 26–27). Evaluation of AI readiness level in the ministries of Indonesia [Conference paper]. International Conference on Computer System, Information Technology, and Electrical Engineering (COSITE), Banda Aceh, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Ishengoma, F. R., Shao, D., Alexopoulos, C., Saxena, S., & Nikiforova, A. (2022). Integration of artificial intelligence of things (AIoT) in the public sector: Drivers, barriers and future research agenda. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 24(5), 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. R. (2024). Administrative reform in Bangladesh civil service in the era of artificial intelligence. In Comparative governance reforms: Assessing the past and exploring the future (pp. 213–233). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, R. K., & Jha, M. (2024). Optimizing e-government cybersecurity through artificial intelligence integration. Journal of Trends in Computer Science and Smart Technology, 6(1), 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M., Gu, X., Guo, Q., & Ding, X. (2024, June 14–16). Research on government data governance in the era of large language model [Conference paper]. IEEE International Conference on Data Science in Cyberspace (DSC), Shanghai, China. [Google Scholar]

- Jirari, S., El Makkaoui, I., Benbrahim, M., El Khalfi, A., El Yadari, I., & Benaddy, F. (2025, April 18–19). Artificial intelligence and Morocco’s education system: A strategic tool for enhancing public management and institutional performance [Conference paper]. International Conference on Circuit, Systems and Communication (ICCSC), Rabat, Morocco. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, S. H., Aljohani, N., Mishra, D., Garg, N., Verma, V., & Malathy, V. (2023, December 14–15). Applications of artificial intelligence in public sector and its challenges [Conference paper]. International Conference on Computation, Automation and Knowledge Management (ICCAKM), Dubai, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Fan, Y., & Nie, L. (2025). Making governance agile: Exploring the role of artificial intelligence in China’s local governance. Public Policy and Administration, 40(2), 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malodia, S., Dhir, A., Mishra, M., & Bhatti, Z. A. (2021). Future of e-government: An integrated conceptual framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, R., & Hossain, M. A. (2024). AI hub: Idea to innovative service—An AI service hub for the citizens of Bangladesh to accelerate the implementation of Smart Bangladesh. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 12(5), 1217–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S. T., Elbir, A., & Aydin, N. (2022, September 7–9). Enhancing e-governance in the Ministry of Electricity in Iraq using artificial intelligence [Conference paper]. Innovations in Intelligent Systems and Applications Conference (ASYU), Antalya, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Monasterio Astobiza, A., Ausín, T., Liedo, B., Toboso, M., Aparicio, M., & López, D. (2022). Ethical governance of AI in the global south: A human rights approach to responsible use of AI. Proceedings, 81(1), 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañés-Sánchez, J., Sánchez-Fernández, M. D., Soares, J. R. R., & Ramón-Cardona, J. (2025). High performance work systems in the tourism industry: A systematic review. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muparadzi, T., Wissink, H., & McArthur, B. (2024). Towards a framework for accelerating e-government readiness for public service delivery improvement in Zimbabwe. Administratio Publica, 32(2), 96–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawafleh, S., Rawabdeh, I., Qaoud, G. A., & Alshoubaki, W. E. (2025). E-governance and AI impact on the improvement of e-government services: Transformative leadership as a mediator. International Journal of Electronic Governance, 17(1), 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osakwe, J., Mutelo, S., & Shilamba, M. (2021, November 22–26). Artificial intelligence: A veritable tool for governance in developing countries [Conference paper]. International Multidisciplinary Information Technology and Engineering Conference (IMITEC), Windhoek, Namibia. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantinga, P. (2024). Digital discretion and public administration in Africa: Implications for the use of artificial intelligence. Information Development, 40(2), 332–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramathilagam, A., Gunasekaran, K., Pandian, E., Kumar, M. S., Ponkumar, D. D. N., & Saravanakumar, R. (2024, January 5–7). G-Bot: Revealing government programs with smarted assistance [Conference paper]. International Conference on Recent Trends in Microelectronics, Automation, Computing and Communications Systems (ICMACC), Hyderabad, India. [Google Scholar]

- Rathnayake, A. S., Nguyen, T. D. H. N., & Ahn, Y. (2025). Factors influencing AI chatbot adoption in government administration: A case study of Sri Lanka’s digital government. Administrative Sciences, 15(5), 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, D. (2025). Integration of IoT and edge computing in smart industrial environments. Technical Science Integrated Research, 1(1), 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y., Natori, T., & Yu, X. (2025). Trusting humans or bots? Examining trust transfer and algorithm aversion in China’s e-government services. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalević, Ž., Kaljević, J., Vučetić, S., & Milić, P. (2023). Enhancing legally-based e-government services in education through artificial intelligence. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education, 11(3), 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M., & Sharma, N. (2025). E-governance and AI integration: A roadmap for smart governance practices. Samsad Journal, 2(1), 160–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhendarto, B. P. (2025). Integration of e-government and artificial intelligence to increase public participation in local governance. Law and Justice, 10(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahidi, A. A., Kiyokawa, K., & Nuchitprasitchai, S. (2025, August 9). A fine-tuned GPT-4-based question answering system for e-government services using a custom-built dataset [Conference paper]. IEEE Symposium on Computers & Informatics (ISCI), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- Tamilarasi, R., Karthik, S., Priya, D., Ananth, V., & Sharma, A. (2024, February 28–March 1). Machine learning challenges of e-government models of cloud computing in developing countries [Conference paper]. International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India. [Google Scholar]

- Toderas, M. (2025). Artificial intelligence for sustainability: A systematic review and critical analysis of AI applications, challenges, and future directions. Sustainability, 17(17), 8049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totonchi, A. (2025). Artificial intelligence in e-government: Identifying and addressing key challenges. Malaysian Journal of Information and Communication Technology, 10(1), 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tueiv, M., & Schmitz, E. (2023, September 26–29). Maximizing the value delivered of chatbots in e-Gov using the incremental funding method [Conference paper]. 16th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Belo Horizonte, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). (2024). UN e-government survey 2024. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Vigan, F. A., & Giauque, D. (2018). Job satisfaction in African public administrations: A systematic review. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 84(3), 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Teo, T. S., & Janssen, M. (2021). Public and private value creation using artificial intelligence: An empirical study of AI voice robot users in Chinese public sector. International Journal of Information Management, 61, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Xiao, Y., & Liang, Z. (2024). Exploring cross-national divide in government adoption of artificial intelligence: Insights from explainable artificial intelligence techniques. Telematics and Informatics, 90, 102134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, H. S. (2023, June 21–24). Overseeing government with AI: Lessons learned from a Brazilian experience [Conference paper]. Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Aveiro, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W., Zuo, N., He, W., Li, S., & Yu, L. (2021). Factors influencing the use of artificial intelligence in government: Evidence from China. Technology in Society, 66, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Li, Y. (2025). The impact of artificial intelligence on government digital service capacity. International Review of Economics & Finance, 98, 104374. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., Huo, Y., Abedin, M. Z., Shang, Y., & Alofaysan, H. (2025). Intelligent government: The impact and mechanism of government transparency driven by AI. Public Money & Management, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., Liu, L., Zhang, J., & Feng, Y. (2025a). Exploring the role of chatbots in enhancing citizen e-participation in governance: Scenario-based experiments in China. Journal of Chinese Governance, 10(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z., Liu, D., Chen, Z., & Pancho, M. (2025b). Government adoption of generative artificial intelligence and ambidextrous innovation. International Review of Economics & Finance, 98, 103953. [Google Scholar]

| Database | Total Papers | Qualitative | Quantitative | Articles | Conference Papers | UMIC | LMIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | 15 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 4 | 10 | 5 |

| IEEE Xplore | 19 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 19 | 9 | 10 |

| Scopus | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Semantic Scholar | 7 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| Google Scholar | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| EBSCO | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 50 | 33 (66%) | 17 (34%) | 22 (44%) | 28 (56%) | 24 (48%) | 26 (52%) |

| Subtheme | Category | Specific Area | Scholars |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance, regulation and ethics | Regulatory frameworks | Legal compliance requirements | Rathnayake et al. (2025); Bakhov et al. (2025); Jha and Jha (2024); Zhao et al. (2025); Ji et al. (2024) |

| Data protection regulations | Y. Zhang and Li (2025); Efe (2023); Ji et al. (2024); Jirari et al. (2025) | ||

| Ethical governance | Algorithmic fairness regulation | Efe (2023); Jha and Jha (2024); Arora et al. (2024); Xavier (2023) | |

| Accountability mechanisms | Efe (2023); Rathnayake et al. (2025); Arora et al. (2024) | ||

| Public value and impact | Public value creation (operational and strategic) | Li et al. (2025); C. Wang et al. (2021); Chatterjee et al. (2022) | |

| Socio-economic impact | Aminah and Saksono (2021); Barodi and Lalaoui (2023) | ||

| Oversight mechanisms | Independent auditing and external monitoring | Efe (2023); Rathnayake et al. (2025); Y. Zhang and Li (2025) | |

| Strategic and implementation planning | National strategy | AI strategy development | Y. Zhang and Li (2025); Srivastava and Sharma (2025); Aminah and Saksono (2021); Herdhiyanto et al. (2023) |

| Digital transformation roadmaps | Efe (2023); Suhendarto (2025); Aminah and Saksono (2021); Barodi and Lalaoui (2023) | ||

| Localisation strategies | Academic/industry collaboration | Febiandini and Sony (2023); Ishengoma et al. (2022) | |

| Context-specific adaptation | Bakhov et al. (2025); Plantinga (2024); Aminah and Saksono (2021) | ||

| Implementation planning | Phased rollout approach | Ishengoma et al. (2022); Y. Zhang and Li (2025); Tueiv and Schmitz (2023) | |

| Pilot programmes | Abdulkareem (2024); Y. Zhang and Li (2025) | ||

| Resource planning | Funding allocation | Efe (2023); Mazumder and Hossain (2024); Y. Zhang and Li (2025) | |

| Infrastructure development | Efe (2023); Srivastava and Sharma (2025); Aminah and Saksono (2021); Nawafleh et al. (2025); Tamilarasi et al. (2024) | ||

| Technology and infrastructure development | System architecture | Scalable platform infrastructure | Hasan et al. (2021); Chinnasamy et al. (2023) |

| Interoperability standards | Alqudah et al. (2024); Hasan et al. (2021); Aminah and Saksono (2021); Garcia-Carrera et al. (2025) | ||

| AI capabilities | Advanced algorithm development | Chinnasamy et al. (2023); Alqudah et al. (2024); Jha and Jha (2024); Chinnapareddy et al. (2025) | |

| Appropriate specialised AI model development | Z. Zhou et al. (2025b); Ji et al. (2024); Fang and Xu (2023); Syahidi et al. (2025); Chiranjeevi et al. (2024); Ramathilagam et al. (2024) | ||

| Cybersecurity integration | Cybersecurity implementation | Alqudah et al. (2021); Hasan et al. (2021); Elisa et al. (2023); Tamilarasi et al. (2024); Ajay et al. (2024) | |

| Integration Models and Frameworks | Integration model/framework appropriateness | Jha and Jha (2024); Alqudah et al. (2024); Chinnasamy et al. (2023); Hasan et al. (2021) | |

| AI-ready e-government platforms | Hasan et al. (2021); Efe (2023); Alqudah et al. (2024); Srivastava and Sharma (2025); Suhendarto (2025) | ||

| Data governance | Data quality and management | Herdhiyanto et al. (2023); Ji et al. (2024); Aminah and Saksono (2021) | |

| Open Data Practices | Zhao et al. (2025); Spalević et al. (2023); Essabbar et al. (2024) | ||

| Physical infrastructure | Network infrastructure | Plantinga (2024); Efe (2023); Hakimi et al. (2023); Aminah and Saksono (2021) | |

| Computing and hardware resources | Chinnasamy et al. (2023); Hasan et al. (2021); Alqudah et al. (2024); Jha and Jha (2024) | ||

| Organisational capacity development | Change management | Innovation culture development | Ishengoma et al. (2022); Osakwe et al. (2021) |

| Lifecycle management systems | Chinnasamy et al. (2023); Suhendarto (2025) | ||

| Performance management | Continuous evaluation mechanisms | Efe (2023); Suhendarto (2025); Jirari et al. (2025) | |

| Value-based prioritisation | Alqudah et al. (2021); Bakhov et al. (2025); Tueiv and Schmitz (2023) | ||

| Interagency coordination | Cross-government collaboration | Y. Zhang and Li (2025); Ishengoma et al. (2022); Aminah and Saksono (2021) | |

| Multi-stakeholder Engagement | Public-private partnerships | Mazumder and Hossain (2024); Hakimi et al. (2023); Aminah and Saksono (2021) | |

| Human capital and expertise | Workforce development | Education, skills and training development | Alqudah et al. (2021); Abdulkareem (2024); Osakwe et al. (2021); Herdhiyanto et al. (2023); Nawafleh et al. (2025) |

| Knowledge management | Research and knowledge development | Alqudah et al. (2021); Efe (2023); Mazumder and Hossain (2024); Jha and Jha (2024); Bakhov et al. (2025) | |

| Learning systems | Experience-based learning | Plantinga (2024); Abdulkareem (2024); Cheng et al. (2021) | |

| Research-driven adaptation | Abdulkareem (2024); Plantinga (2024) | ||

| AI adoption, implementation, and impact | Operational implementation and assimilation capabilities | Human/AI interaction design/dual AI model deployment | Cheng et al. (2021); C. Wang et al. (2021); Li et al. (2025); Song et al. (2025) |

| Integration depth and breadth | Chatterjee et al. (2022); S. Wang et al. (2024) | ||

| Strategic analysis and adoption planning | Framework application | S. Wang et al. (2024); Z. Zhou et al. (2025b) | |

| Stakeholder influence mapping | W. Zhang et al. (2021); Rathnayake et al. (2025) | ||

| Performance and impact evaluation | Impact on government transparency | Zhao et al. (2025) | |

| Impact on citizen satisfaction | Chatterjee et al. (2022); El El Gharbaoui et al. (2024); C. Wang et al. (2021) | ||

| Impact on operational and strategic performance | Chatterjee et al. (2022); Nawafleh et al. (2025); Jirari et al. (2025); Mohammed et al. (2022) | ||

| Citizen engagement and participation | Trust building | Transparency mechanisms | Rathnayake et al. (2025); Hakimi et al. (2023); Zhao et al. (2025); Spalević et al. (2023); Song et al. (2025) |

| Public awareness processes | Rathnayake et al. (2025); Osakwe et al. (2021) | ||

| Inclusive design | Accessibility features assessment | Rathnayake et al. (2025); Bakhov et al. (2025); Tueiv and Schmitz (2023) | |

| User-centric designs/approaches | Abdulkareem (2024); Cheng et al. (2021); M. Zhou et al. (2025a); Syahidi et al. (2025) | ||

| Public participation | Citizen engagement mechanisms | Suhendarto (2025); Bakhov et al. (2025); M. Zhou et al. (2025a); Xavier (2023) | |

| Community collaboration | Rathnayake et al. (2025); Bakhov et al. (2025); Cheng et al. (2021) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kampira, A.; Mukonza, R.M. E-Government/AI Integration State and Capacity in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120482

Kampira A, Mukonza RM. E-Government/AI Integration State and Capacity in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(12):482. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120482

Chicago/Turabian StyleKampira, Abisha, and Ricky Munyaradzi Mukonza. 2025. "E-Government/AI Integration State and Capacity in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 12: 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120482

APA StyleKampira, A., & Mukonza, R. M. (2025). E-Government/AI Integration State and Capacity in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. Administrative Sciences, 15(12), 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120482