Abstract

Purpose—This study explores the determinants of entrepreneurial intention (EI) among university students, analyzing entrepreneurial motivation (EM) as a mediator and perceived institutional support (PIS) as a moderator within the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) framework. Design/Methodology/Approach—Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), data from 128 students at the Polytechnic Institute of Cávado and Ave, Portugal, were analyzed to assess direct, indirect, and moderating effects of entrepreneurial attitudes, education, and social norms. Findings—EM significantly mediates the relationship between attitude concerning entrepreneurship (ACE), perceived social norms (PSN), entrepreneurial education (EE), and EI, reinforcing its role in bridging individual and educational influences with entrepreneurial behavior. However, PIS does not significantly moderate the EM-EI relationship, suggesting institutional support alone is insufficient to enhance motivation’s impact on EI. This challenges assumptions about institutional effectiveness and highlights the importance of entrepreneurial ecosystems, social capital, and mentorship networks as alternative enablers. Implications—The study extends TPB by incorporating mediation and moderation effects, offering a deeper understanding of personal, social, and institutional influences on EI. This study contributes by simultaneously modeling entrepreneurial motivation as mediator and perceived institutional support as moderator within a TPB framework. Such integration remains rare, particularly in Southern European higher education contexts, and our findings nuance current assumptions by revealing when institutional supports may fail to strengthen motivational pathways. The findings emphasize the need for education policies that integrate experiential learning, entrepreneurial ecosystems, and mentorship to foster entrepreneurial mindsets. Originality/Value—This research challenges the assumed role of institutional support, highlighting motivation as a key driver of EI and providing new insights into policy-driven entrepreneurship promotion in higher education.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship has increasingly established itself as a critical driver of economic growth and innovation (Dieguez et al., 2023; Kreiterling, 2023), setting its position as a prominent field of academic research (Alkathiri et al., 2024; Fernandes et al., 2022; Thurik et al., 2024). At its core, entrepreneurship involves identifying, creating, and leveraging opportunities to foster the development of new products, processes, and organizations while simultaneously revitalizing established enterprises (Munyo & Veiga, 2024). Recognized as a key element for achieving competitive advantages, generating wealth, and advancing societal progress, entrepreneurship takes on heightened significance in a global context marked by increasing complexity, uncertainty, and volatility (Audretsch & Belitski, 2021).

In this dynamic environment, universities play a pivotal role in equipping students with the necessary skills and knowledge to address the pressing challenges of the 21st century. By fostering entrepreneurial competencies and innovation-driven mindsets, higher education institutions can empower future leaders to navigate and thrive in this rapidly changing landscape (Bardales-Cárdenas et al., 2024; Dieguez et al., 2021; Dieguez et al., 2024).

While entrepreneurial education plays a vital role in equipping individuals with the skills needed for innovation and sustainable business creation (Del Vecchio et al., 2021), gaps remain in the literature regarding key determinants of entrepreneurial intention (EI), such as perceived social norms (PSN), attitude concerning entrepreneurship (ACE), entrepreneurial motivation (EM), and the moderating role of perceived institutional support (PIS). Although the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) has been widely applied to understand EI, the mediating effect of EM and the moderating influence of PIS have received limited attention. This study aims to bridge the gap between entrepreneurial intention and action in the context of sustainable university entrepreneurship, examining the mediating role of motivation and the influence of institutional support.

This study, grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), examines the relationship between these variables and entrepreneurial intention (EI) using data collected from 128 students at the Polytechnic Institute of Cávado and Ave, based in the North of Portugal. Quantitative methods were employed, including Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29.0.2.0 (20))) program and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), Path Analysis, and Moderation and Mediation Tests.

The results indicate that attitude concerning entrepreneurship exerts a strong and direct positive influence on entrepreneurial intention, while perceived social norms significantly shape entrepreneurial intention by affecting entrepreneurial behavior. Entrepreneurial education (EE) contributes to the development of EI, notwithstanding with a relatively smaller effect size. Entrepreneurial motivation (EM) emerges as a critical determinant of EI, not only exerting a strong direct influence but also mediating the relationship between ACE and EI, amplifying the effects of PSN on EI, and bridging the connection between EE and EI, thereby underscoring the indirect role of education. However, Perceived Institutional Support (PIS) does not significantly moderate the relationship between EM and EI.

This study specifically addresses the gap between entrepreneurial intention and action in sustainable university entrepreneurship, assessing motivation as a mediating factor and institutional support as a contextual influence within the Theory of Planned Behavior framework. This study contributes by simultaneously modeling entrepreneurial motivation as mediator and perceived institutional support as moderator within a TPB framework. Such integration remains rare, particularly in Southern European higher education contexts, and our findings nuance current assumptions by revealing when institutional supports may fail to strengthen motivational pathways. Our results confirm this and suggest that the mechanisms of institutions do not always succeed in adding their own weight to a motivational path, as it may seem is commonly held.

The structure of this article begins with an introduction, followed by the theoretical framework for the topics under analysis presented in Section 2, while Section 3 outlines the methodology employed in this study. Section 4 describes the results, including descriptive statistics, and explores the discussion of the findings, examining research paths and proposing a future research agenda. Finally, Section 5 concludes with the main findings alongside theoretical and practical implications as well as directions for further exploration.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Entrepreneurial Intention and the Theory of Planned Behavior

Entrepreneurial intention refers to a person’s conscious state of mind that directs attention, experience, and action to start any venture or business. Within TPB for N. F. Krueger et al. (2000), attitudes, social norms, and how they influence determination are examined. In other words, these make up Ajzen’s (1991) combination of all three TPB variables.

Entrepreneurial intention (EI) has been extensively studied, with models developed to explain its dynamics. Among these, Ajzen’s (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is a key framework for understanding factors driving entrepreneurial activities. TPB identifies three determinants of intention: attitude toward the behavior, perceived social norms (SN), and perceived behavioral control (PBC). TPB effectively predicts entrepreneurial intentions and actions (Dieguez et al., 2023; Karan et al., 2024). Attitude concerning entrepreneurship (ACE) reflects how individuals assess the pros and cons of starting a business and is a primary driver of EI, as favorable attitudes foster entrepreneurial pursuits (Douglas et al., 2021; Martínez-Cañas et al., 2023). Perceived social norms (PSN) reflect the influence of networks like family, peers, and mentors on entrepreneurial behavior (Bazan, 2022; Hossain et al., 2023). PBC, or confidence in managing a business, impacts not only EI but also its conversion into actions (Al-Mamary & Alraja, 2022; Romero-Colmenares & Reyes-Rodríguez, 2022).

2.2. The Role of Entrepreneurial Education

Entrepreneurial education is defined as structured learning experiences that develop knowledge, skills, and attitudes to recognize and pursue entrepreneurial opportunities (Fayolle & Gailly, 2008). It includes formal, informal, and experiential approaches that influence how students perceive and engage with entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurial education (EE) is a key driver of entrepreneurial intention, equipping individuals with skills and knowledge to manage the complexities of entrepreneurship. It fosters resilience, creative problem-solving, and adaptability to address entrepreneurial uncertainties (Bauman & Lucy, 2021; Gazi et al., 2024; Hassan et al., 2021). The educational and institutional environment also significantly influences entrepreneurial intention, offering opportunities to transform ideas into viable ventures (Porfírio et al., 2023; Mohamed & Sheikh Ali, 2021). EE enhances not only knowledge and skills but also self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control, which in turn strengthen EI. Recent large-scale evidence from emerging economies confirms that sustainable EE significantly predicts students’ entrepreneurial intentions (López Sánchez et al., 2024; Rakicevic et al., 2023). Beyond technical knowledge, EE cultivates values, attitudes, and competencies such as leadership and innovation, which are critical for entrepreneurial success (Ferreira-Neto et al., 2023; Maziriri et al., 2024).

However, not all forms of entrepreneurial education exert the same influence on EI, making it essential to differentiate between its varying approaches (Alam & Bhowmick, 2023). Formal EE, typically offered through structured academic programs and degrees, provides foundational knowledge and theoretical frameworks but may lack practical engagement (Mohamed & Sheikh Ali, 2021). In contrast, informal EE, which includes workshops, mentorship programs, and business incubators, offers hands-on learning and networking opportunities that enhance entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Bauman & Lucy, 2021). Additionally, experiential EE, such as business simulations, startup competitions, and real-world entrepreneurial projects, has gained prominence as an effective method for fostering proactive entrepreneurial behavior and opportunity recognition (Porfírio et al., 2023). Technology-mediated approaches such as virtual laboratories illustrate how experiential EE scales skill acquisition and motivation; adoption follows diffusion-of-innovation dynamics and is associated with higher perceived usefulness and intention to use (Achuthan et al., 2020).

Despite the positive impact of EE, studies suggest that education alone may not be sufficient to drive EI, as entrepreneurial motivation (EM) and the presence of role models often act as key moderating factors (Maziriri et al., 2024; Nowiński & Haddoud, 2019) Moreover, the institutional environment significantly shapes EE’s effectiveness, as access to resources, policy support, and entrepreneurial ecosystems influences the extent to which education translates into venture creation (Stephan et al., 2015; Mohamed & Sheikh Ali, 2021). Therefore, future research should explore the interplay between different types of EE, motivational drivers, and institutional factors to develop more holistic and impactful entrepreneurial education models.

Immersive modalities (e.g., VR/AR) can elicit flow and satisfy SDT needs, while adoption follows TAM/UTAUT antecedents (usefulness, ease, facilitating conditions), together reinforcing motivational pathways to EI (Raman et al., 2025). The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM; Davis, 1989) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT; Venkatesh et al., 2003) explain technology adoption through key factors such as perceived usefulness, ease of use, social influence, and facilitating conditions, which in turn shape behavioral intention.

2.3. Entrepreneurial Motivation as a Driver

Entrepreneurial motivation involves the internalized ambition and disposition to start and run a business (Haynie et al., 2010). It is associated both with a person’s inner needs (e.g., autonomy, competence, and relatedness; intrinsic motivation aspects seen in (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and expectancy-value considerations (Wigfield & Eccles, 2002).

Entrepreneurial motivation (EM) is a crucial determinant of entrepreneurial intention (EI), characterized as the internal drive that compels individuals toward entrepreneurial pursuits. It emerges from a combination of personal attributes, including psychological traits, values, and demographics (Batz Liñeiro et al., 2024; Ephrem et al., 2021), and can be categorized into general versus task-specific motivation (Sahu et al., 2023). Additionally, EM encompasses both structural drivers, linked to planning and strategic decision-making, and dynamic drivers, shaped by emotional and intrinsic factors (Nag et al., 2024; Vrontis et al., 2022). However, motivation is not solely an individual construct; contextual influences, such as social, environmental, and institutional conditions, play a pivotal role in shaping its intensity and direction (A. L. Carsrud et al., 1989; Esfandiar et al., 2019; L. Lee et al., 2011).

Among these external influences, Perceived Institutional Support (PIS) is often cited as a crucial enabler, particularly within educational ecosystems, where it provides access to resources, mentorship, and networking opportunities that facilitate the translation of entrepreneurial aspirations into actionable ventures (Behfar et al., 2024; Semrau et al., 2016). Nevertheless, empirical findings on the effectiveness of institutional support remain inconsistent. While some studies argue, for example, that PIS fosters social entrepreneurship, its impact is highly dependent on regional economic conditions and institutional frameworks (Stephan et al., 2015). Others suggest that institutional environments influence EI indirectly, rather than through direct support mechanisms (Bazan, 2022). Furthermore, research indicates that peer influence and entrepreneurial role models often exert a stronger effect on EI than institutional support alone (Porfírio et al., 2023). This variability suggests that PIS may only be effective when combined with other contextual factors, such as social capital, entrepreneurial networks, and cultural attitudes toward risk-taking.

Therefore, future research should investigate the interplay between institutional support and broader ecosystem dynamics to better understand its role in shaping entrepreneurial motivation and intention. Drawing on Self-Determination Theory and Expectancy-Value Theory, EM is positioned as the volitional mechanism that translates TPB antecedents into entrepreneurial intention.

2.4. Perceived Institutional Support as a Moderator

Perceived institutional support (PIS) is the extent to which students believe that their university and related institutions provide resources, policies, and networks that facilitate entrepreneurship (Walter & Block, 2016). It represents the institutional dimension of entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Institutional support is commonly regarded as a facilitator of entrepreneurial activity, offering financial assistance, policy backing, and networking opportunities that can reinforce motivation and intention toward entrepreneurship (Nag et al., 2024; Stephan et al., 2015). From a theoretical perspective, Resource-Based Theory (Barney, 1991) suggests that access to institutional resources enhances entrepreneurial success, while Institutional Theory (Scott, 2005) highlights the role of regulatory and normative pressures in shaping entrepreneurial behavior. Based on these theories, it was expected that higher levels of institutional support would strengthen the EM-EI relationship by providing tangible incentives and structural assistance to aspiring entrepreneurs.

However, the absence of a significant moderating effect suggests that institutional support alone may not be sufficient and that its influence is likely contingent on additional factors. For example, research indicates that entrepreneurial motivation is often driven more by intrinsic factors (e.g., self-efficacy, risk-taking) and social influences (e.g., peer networks, role models) than by formal institutional mechanisms (Ephrem et al., 2021). This highlights the need to reconsider whether PIS is the most effective moderator and whether alternative contextual variables should be explored.

2.5. The Complexity of Entrepreneurial Motivation

Entrepreneurial motivation is a complex construct that can be defined by the driver’s own internal mechanisms (e.g., passion, self-efficacy) and actual circumstances (institutional encouragement; social consultation) jointly affecting one’s venture purpose behavior (A. Carsrud & Brännback, 2011).

Entrepreneurial motivation (EM) is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon that emerges from the interplay between internal factors, such as autonomy and personal competencies, and external influences, including institutional frameworks and societal support (Zhou et al., 2023). This complexity underscores the necessity of an integrated approach (Barbosa et al., 2024) to understanding how motivation drives entrepreneurial intention (EI) and behavior (Lang & Liu, 2019).

A strong theoretical foundation for understanding EM is provided by Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Al-Jubari et al., 2019; Ryan & Deci, 2000), which differentiates between intrinsic motivation, driven by personal satisfaction and self-fulfillment, and extrinsic motivation, influenced by external rewards and pressures. This distinction is particularly relevant in the entrepreneurial context, where individuals may be motivated by passion and autonomy or by financial gains, social expectations, and institutional incentives.

In addition to psychological dimensions, contextual factors play a critical role in shaping entrepreneurial motivation. A. Carsrud and Brännback (2011) conceptualize EM as a construct shaped not only by individual cognitive and emotional traits but also by social and institutional environments, reinforcing the argument that motivation is not merely an individual characteristic but is embedded in a broader entrepreneurial ecosystem. Ephrem et al. (2021) further emphasize the role of psychological capital, such as self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism, in fostering entrepreneurial motivation and persistence.

Moreover, recent research highlights that entrepreneurial motivation is influenced by factors beyond traditional psychological theories. For instance, Expectancy-Value Theory (Wigfield, 1994; Wigfield & Eccles, 2002) suggests that individuals develop motivation based on perceived benefits and expected success in entrepreneurship, reinforcing the role of entrepreneurial education and social norms. Similarly, Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1999; Luszczynska & Schwarzer, 2015) underscores the impact of observational learning, role models, and self-efficacy on motivation, particularly in environments where entrepreneurship is a viable career path.

Given these perspectives, it is manifest that entrepreneurial motivation extends beyond psychological predispositions, encompassing institutional support, entrepreneurial ecosystems, and socio-economic conditions that influence individual decision-making. Recognizing these dynamics provides valuable insights for policymakers, educators, and institutional leaders, emphasizing the need for entrepreneurial education programs, mentorship initiatives, and supportive institutional policies to cultivate a robust entrepreneurial culture. Future research should explore how these contextual factors interact to enhance or hinder entrepreneurial motivation, particularly in diverse socioeconomic environments where access to resources, funding, and institutional support varies significantly.

Consistent with Institutional Theory and the Resource-Based View, PIS is modeled here as a moderator rather than a direct predictor. This choice reflects the expectation that institutional enablers, namely rules, norms, and support structures, buffer motivational constraints and strengthen (or weaken) the effectiveness of individual motivational resources in driving EI. By positioning PIS as a boundary condition rather than a universal antecedent, the model captures its context-dependent role in shaping entrepreneurial pathways.

2.6. Research Hypotheses

Entrepreneurial intention is significantly shaped by core constructs such as attitude toward entrepreneurship, perceived social norms, and perceived behavioral control, as outlined in the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Entrepreneurial education further enhances this intention by developing skills, fostering resilience, and cultivating adaptability among aspiring entrepreneurs. The institutional and educational environment acts as a facilitator, empowering individuals to recognize and seize entrepreneurial opportunities (Hammoda, 2025). Entrepreneurial motivation also plays a pivotal role in linking intention to behavior, driven by internal factors like psychological traits and values, as well as external influences such as social and institutional support systems (Batz Liñeiro et al., 2024). Given its complexity, further exploration is needed to understand how these variables interact to influence entrepreneurial behavior and outcomes. Based on these insights, we propose eight hypotheses, hypotheses that we will detail on the next paragraphs.

For some time now, attitudes towards entrepreneurship have been recognized as an important determinant of entrepreneurial intention. Since people’s perceptions of entrepreneurship as an attractive and viable alternative influence whether they are more likely to have a genuine intention to start-up (Ajzen, 1991; Douglas et al., 2021; Martínez-Cañas et al., 2023), if people perceive the possibility of starting their own business worthy enough, they may be more willing to engage in this type of behavior.

H1.

ACE positively influences EI.

Further, social expectations may have a similar effect in the sense that support and lack of support from family members, peers, or mentors, for example, also steer how people perceive creating their own business, either positively or negatively, strengthening or discouraging their entrepreneurial intention (Bazan, 2022; Hossain et al., 2023; Kolvereid, 1996).

H2.

PSN positively influences EI.

Regarding learning experiences, if the entrepreneurship education is designed to do more than transmit knowledge, it equips individuals with problem-solving skills, creativity, and resilience, allowing students to feel better prepared for uncertainty and consider an entrepreneurial career as a feasible alternative (Bauman & Lucy, 2021; Gazi et al., 2024; Porfírio et al., 2023).

H3.

EE positively influences EI.

Though positive attitudes, network support, and education college alone cannot guarantee “entrepreneurial intention” (Ephrem et al., 2021; Vrontis et al., 2022), there are several possible models that can be adopted. The process of circular accumulation of results driven by this motive power converts material stratified intention into action that is consistent with entrepreneurial goals.

H4.

EM exerts a positive influence on EI.

This motivational force also helps to explain why favorable attitudes sometimes lead to strong intentions and other times do not. Without motivation, even positive perceptions of entrepreneurship may fail to generate a clear intention to act (Haynie et al., 2010; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

H5.

EM mediates the relationship between ACE and EI.

A similar dynamic applies to social norms. Encouragement and recognition from others are most powerful when they spark or reinforce a person’s own motivation to become an entrepreneur (Bandura, 1999; Linan, 2008).

H6.

EM mediates the relationship between PSN and EI.

The effectiveness of entrepreneurship education likewise depends on its ability to inspire. Courses and initiatives that foster self-belief and enthusiasm are more likely to translate into entrepreneurial intention than those that merely deliver technical content (Chahal et al., 2024; Souitaris et al., 2007).

H7.

EM mediates the relationship between EE and EI.

Moreover, the institutional context also influences motivation. While we often assume that support from universities or other bodies strengthens the link between motivation and intention, there is representative and counterevidence. In some contexts, it acts as an enabler, while in others its effect is negligible. For this reason, perceived institutional support is treated here as a potential moderator, rather than as a universal condition (Kara et al., 2024; Stephan et al., 2015).

H8.

PIS moderates the relationship between EM and EI.

We used a moderated mediation model in this study because prior research shows that institutional enablers can help stimulate entrepreneurial activity, but their impact varies by context. Thus, we test whether PIS strengthens the EM → EI path as a boundary condition rather than assuming it to be universally effective (Abigael et al., 2024; Davidsson et al., 2025; Malin et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2022).

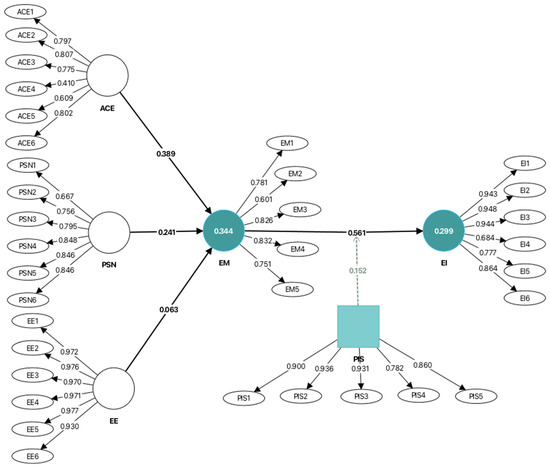

The proposed hypotheses form the foundation of a theoretical model designed to explore the influence of ACE, PSN, EE, and EM on entrepreneurial intention (EI). This model examines EM as both a direct determinant of EI and a mediator in the relationships between ACE, PSN, and EE with EI. Furthermore, it investigates the moderating role of PIS in the relationship between EM and EI. Grounded in the earlier theoretical framework, this model provides a systematic approach to understanding the intricate interactions among these constructs. Figure 1 presents the structural model results derived from the PLS-SEM analysis. The path coefficients, indicated on the arrows, represent the strength and direction of relationships between constructs. The R2 values within the endogenous constructs (EM and EI) indicate the variance explained by the predictor variables. Outer loadings, displayed next to the indicators, assess the reliability of each indicator with its respective latent variable. Detailed interpretations of these findings will be discussed in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model Results.

2.7. Research Hypotheses (Integrative Theoretical Rationale: TPB—Centric Model with EM as Mediator and PIS as Moderator)

This study adopts Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) as the primary framework for entrepreneurial intention (EI) while integrating Self-Determination Theory (SDT) to explain how internalized autonomy/competence/relatedness enhance entrepreneurial motivation (EM), and Expectancy-Value Theory to connect perceived value and success expectancies with motivated goal pursuit.

Within this TPB-plus lens, EM is theorized to mediate attitudinal, social-normative, and educational antecedents. In parallel, perceived institutional support (PIS) is conceptualized as a boundary condition grounded in Institutional Theory and the Resource-Based view, such that rules, norms, and access to resources can amplify (or dampen) the EM → EI linkage. Evidence from large-scale educational contexts corroborates the pathway from education to intention through motivation and value-expectancy mechanisms (Abigael et al., 2024).

3. Operationalization, Data, and Method

3.1. Operationalization and Data

The methodologies adopted in this study were tailored to achieve the primary objective: identifying student profiles concerning entrepreneurial intention within the context of sustainable entrepreneurship, focusing on attitudes, norms, and behaviors. Operating within a constructivist research paradigm, this quantitative study was both descriptive and inductive in nature. Data collection was conducted using a questionnaire adapted from prior validated instruments (Grégoire et al., 2015). The study employed PLS-SEM, a robust and flexible method suitable for exploratory research, predictive analysis, and complex models with non-normal data, making it widely applicable in business, social sciences, and management (Dash & Paul, 2021). Entrepreneurs’ actions are influenced by their values, emotional experiences, and personal judgments about entrepreneurial value creation, alongside their capacity to evaluate potential consequences (Grégoire et al., 2015; Shepherd et al., 2019).

The constructs in the model (Figure 1) were measured using reflective models with multiple items, as recommended by Sarstedt and Cheah (2019). Items were selected based on theoretical and empirical foundations. Data collection, conducted in November 2024, included 128 voluntary participants from a population of 220 students at the Polytechnic Institute of Cávado and Ave (IPCA) in Northern Portugal. Participants, enrolled in an entrepreneurship and innovation course, represented programs in Accounting, Business Management, and Illustration and Animation. Participants were recruited through classroom announcements and follow-up emails. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. The survey was administered online via Moodle during a classroom session and remained open for three hours. The sample comprised 128 students (57% female; mean age = 22.3 years, SD = 2.1) across business, engineering, and social sciences programs. These proportions closely mirror the university’s enrollment profile, suggesting reasonable representativeness.

Power and Minimum Sample Size: We assessed sample adequacy using (i) the ‘10-times rule’ based on the maximum number of structural paths targeting an endogenous construct (five arrows into EI), implying N ≥ 50; (ii) post hoc power for multiple regression with five predictors and a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), yielding power > 0.80 at α = 0.05 for N = 128; and (iii) contemporary PLS guidelines (inverse square root and gamma-exponential heuristics), all supporting that N = 128 is adequate for our model.

The questionnaire, designed in Portuguese, consisted of two sections: (i) sociodemographic data and (ii) entrepreneurial intention. It included 48 items—8 sociodemographic and 40 related to entrepreneurial intention—all mandatory and close-ended. Scales were adapted from Autio et al. (2001) for entrepreneurial intention and attitudes, N. Krueger (1993) for perceived norms and desirability, D. Y. Lee and Tsang (2001) for propensity to act, and Miranda et al. (2017) for perceived institutional support. Insights from Dieguez (2021) were also incorporated. Validation involved academic experts in entrepreneurship and student feedback, leading to adjustments such as the exclusion of perceived entrepreneurial abilities due to weak factor loadings. Demographic data collected included gender, age, professional experience, course, business ownership, marital status, professional status, and family business background. Adjustments ensured the questionnaire’s reliability and alignment with the study’s objectives. The details of the analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measurement items for the constructs in the theoretical model.

In what concerns instrument adaptation and translation, items adapted from validated sources underwent forward translation to Portuguese and independent back-translation to English. Discrepancies were reconciled by a bilingual panel of three entrepreneurship scholars. Cognitive pretests (n = 10) led to minor wording clarifications. Items with weak content equivalence were dropped prior to fielding (Alakaleek et al., 2025). Constructs were measured with multi-item scales adapted from validated sources: Attitude (Ajzen, 2002; 4 items), Subjective Norm (Liñán & Chen, 2009; 3 items), EE (Souitaris et al., 2007; 5 items), EM (Haynie et al., 2010; 5 items), PIS (Walter & Block, 2016; 4 items), and EI (Liñán & Chen, 2009; 6 items).

All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. The original scale ranged from 1 (highest response) to 5 (lowest response). For final research Perceived Entrepreneurial Ability was not considered as already explained in this document.

3.2. Method

To evaluate the theoretical model (Figure 1), Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed, a robust method introduced by Wold (1982) and refined by Sarstedt et al. (2017). Widely used in social sciences, it has applications in knowledge management, information systems and management studies (Praditya & Purwanto, 2024). PLS-SEM is particularly suited for prediction-focused studies (Shmueli et al., 2019) and models with high complexity or exploratory objectives (J. Hair & Alamer, 2022). This method also supports confirmatory research by validating causal relationships, combining explanatory and confirmatory approaches. It effectively handles mediation analyses (Cepeda-Carrion et al., 2023) and advanced model construction (Sobaih & Elshaer, 2022). Model estimation was performed using SmartPLS 3, employing bootstrapping with 5000 samples and a two-tailed test for significance.

The analysis included measurement model evaluation followed by structural model assessment, following (J. F. Hair et al., 2019; J. Hair & Alamer, 2022). Significance was assessed via 5000-sample bootstrapping with bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) 95% CIs. Collinearity was examined with inner VIFs (all < 5). To address potential common-method bias, we (i) assured anonymity, (ii) varied scale anchors, and (iii) separated measurement of predictors and outcomes. Post hoc Harman’s single-factor analysis showed no single factor explained >50% of variance, and full collinearity VIFs were <3.3, indicating CMB is not a major concern.

4. Empirical Analysis

Participant responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics to identify key aspects of entrepreneurial attitudes. The results are structured as follows: Section 4.1 and Section 4.2 present questionnaire findings, Section 4.3 evaluates measurement models, and Section 4.4 examines the structural model.

4.1. Sociodemographic Data

The impact of sociodemographic factors on entrepreneurial intention reveals notable patterns. Most respondents are female (66%), aged 17–25 (85%), single (92%), and full-time students (57%). All were enrolled in an entrepreneurship course, with 40% in the Accounting program. While 12% had owned a business, 43% reported family ties to entrepreneurship.

Sociodemographic factors, except for the “Attending Course” variable (p < 0.001), did not significantly influence entrepreneurial intention, likely due to the sample’s homogeneity. Variables like Gender (p = 0.752), Age (p = 0.088), Civil Status (p = 0.271), and Professional Experience (p = 0.396) showed no significant effects. These findings highlight the critical role of academic programs in shaping entrepreneurial aspirations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and T-Test Results for Demographic Variables.

While our ANOVA/T-tests indicate no significant effects for gender, age, or marital status, we note emerging evidence of gendered pathways to sustainable EI; thus, effects may surface in more heterogeneous samples (Abdelwahed & Alshaikhmubarak, 2023; Alakaleek et al., 2025).

4.2. Entrepreneurial Intention

As previously explained, the entrepreneurial intention was analyzed according to five parameters: attitude, norms, behavior, entrepreneurial education, entrepreneurial motivation and perceived institutional support. Table 3 presents the Reliability Analysis of Constructs, which allows us to conclude that this reliability analysis ensures that the constructs are measured consistently, strengthening the validity of subsequent analyses.

Table 3.

Reliability Analysis of Constructs.

4.3. Assessment of the Measurement Models

The results of the measurement model evaluation, including composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and the Fornell-Larcker criterion, are presented in Table 4. This process involves assessing key metrics, including construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. In what concerns CR, this result measures the internal consistency of the constructs. A CR value of 0.7 or higher is considered acceptable. In this study, all constructs exceed this threshold, demonstrating strong reliability (for example, Entrepreneurial Education (EE): CR = 0.986). For the AVE, measuring the amount of variance captured by a construct relative to the variance due to measurement error, when AVE values are above 0.5 it indicates convergent validity. The constructs in this study meet this criterion, as evidenced (for example, EE: AVE = 0.933). These results confirm that the constructs reliably capture the variance of their indicators, satisfying the requirements for both reliability and convergent validity. Finally, to confirm discriminant validity, the Fornell-Larcker criterion was applied. This method requires that the square root of the AVE for each construct be greater than its correlations with other constructs. This condition ensures that constructs are distinct from one another. The results of this analysis support discriminant validity. For instance, the square root of the AVE for Entrepreneurial Education (EE) is 0.966, which is higher than its correlations with other constructs, such as Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) (0.258) and Social Norms (PSN) (0.187).

Table 4.

Model Evaluation Results: Effects, Reliability, Validity, and Fit Indicators.

These findings collectively establish that the measurement model is robust, with constructs exhibiting adequate reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

4.4. Assessment of the Structural Model

All significance tests were based on 5000-sample BCa bootstrapping, and multicollinearity was not a concern (all VIFs < 5). The structural model results are summarized in Figure 1, which report the path coefficients, t-values, and confidence intervals for each hypothesized relationship.

The evaluation of the structural model involves systematically analyzing key metrics to validate the hypothesized relationships and the overall robustness of the model. This process includes assessing path coefficients, R2 values, effect sizes, and the model’s fit. Path Coefficients, reflect the strength and direction of the hypothesized relationships between constructs. R2 Values Indicate the proportion of variance in dependent variables explained by predictors. Higher R2 values reflect better explanatory power (e.g., 0.50 = moderate, 0.75 = substantial). Effect Sizes (f2) measure the individual impact of each predictor on R2. Small (0.02), medium (0.15), and large (0.35) effects highlight the importance of variables. Model Fit assesses how well the model aligns with the data. Key indicators like SRMR (≤0.08) and NFI (closer to 1) confirm the model’s adequacy. These metrics ensure the model’s validity, predictive strength, and alignment with theoretical expectations. Building on this logic, the answers to the questions posed earlier are summarized in Table 5. From these findings, it becomes clear that Attitude Concerning Entrepreneurship (ACE) has a strong and direct positive impact on Entrepreneurial Intention (EI). Perceived Social Norms (PSN) also play an important role, shaping EI, by influencing Entrepreneurial Motivation (EM). Although Entrepreneurial Education (EE) has a smaller effect, it still makes a meaningful contribution to fostering EI, primarily through indirect pathways. At the core of these relationships lies EM, which emerges as a critical driver of EI, with a strong direct effect (β = 0.561). EM also enhances the impact of ACE on EI through mediation, channels the influence of PSN on EI, and bridges the connection between EE and EI, reinforcing the indirect contribution of education.

Table 5.

Conclusions on the research.

Figure 1 provides further support for these findings, emphasizing the central role of entrepreneurial behavior (EM) in shaping entrepreneurial intention (EI). ACE significantly impacts EM (β = 0.389), which in turn magnifies its effect on EI. Similarly, PSN has a positive influence on EM (β = 0.241), highlighting its role as a critical mediator. Although EE has a smaller indirect effect on EI via EM (β = 0.063), it underscores the foundational role of education in equipping individuals with the skills and mindset necessary for entrepreneurial behavior. Interestingly, Perceived Institutional Support (PIS) does not appear to significantly amplify the relationship between EM and EI (β = 0.0152), suggesting that institutional perceptions may not have a strong influence in this context.

Overall, these results highlight the importance of nurturing entrepreneurial behavior, especially through practical experiences and opportunities to build networks, as this pathway has the strongest influence on entrepreneurial intention.

Looking ahead, future research could further explore the roles of entrepreneurial motivation and institutional support in shaping entrepreneurial intention. Investigating the impact of cultural contexts, socioeconomic backgrounds, and previous entrepreneurial experiences would also provide valuable insights. Comparative studies across institutions and regions, longitudinal research on how entrepreneurial attitudes evolve over time, and qualitative approaches to understanding entrepreneurial motivation are all promising areas for further exploration. Additionally, studying the intersection of digital technologies, innovation, and entrepreneurial intention would align research with current global trends and challenges in the entrepreneurial landscape.

5. Discussion of Findings

The discussion of the findings in this study explores the role of Entrepreneurial Motivation (EM) as a mediator and Perceived Institutional Support (PIS) as a moderator in shaping Entrepreneurial Intention (EI).

Regarding mediation effects of Entrepreneurial Motivation (EM), the findings confirm that Entrepreneurial Motivation (EM) mediates the relationships between Attitude Concerning Entrepreneurship (ACE), Perceived Social Norms (PSN), Entrepreneurial Education (EE), and EI, reinforcing its role as a key mechanism in shaping entrepreneurial behavior. This aligns with previous studies emphasizing motivation as a fundamental link between individual perceptions and entrepreneurial actions (Vrontis et al., 2022; Sahu et al., 2023). From a theoretical perspective, Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) provides a robust explanation for these findings, distinguishing between intrinsic motivation, driven by self-fulfillment and passion, and extrinsic motivation, influenced by rewards and external validation. Similarly, Expectancy-Value Theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002) suggests that individuals engage in entrepreneurship when they perceive value in entrepreneurial activities and expect successful outcomes. Additionally, Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986) underscores the role of observational learning and self-efficacy, suggesting that exposure to entrepreneurial role models strengthens motivational pathways toward EI. In addition, immersive approaches such as VR/AR may complement educational design by fostering flow and motivation, while their adoption tends to follow established TAM/UTAUT factors such as perceived usefulness, ease of use, and facilitating conditions.

However, while EM significantly mediated the effect of ACE, PSN, and EE on EI, its influence may be contingent on additional psychological factors, such as self-efficacy, entrepreneurial passion, and risk tolerance (Ephrem et al., 2021). Future studies could explore alternative mediators, assessing whether factors such as perceived behavioral control or entrepreneurial identity serve as more effective pathways for explaining EI (Aga, 2023; Alshebami et al., 2023; Mishra & Singh, 2024). Competing mediators (e.g., entrepreneurial identity, perceived behavioral control) were not modeled alongside EM; comparative testing is warranted given recent evidence (Paunovic & Deimel, 2025).

Digital enablers and sustainable university entrepreneurship. Emerging digital technologies, particularly immersive and metaverse-based approaches, are increasingly reshaping entrepreneurial ecosystems. Recent studies highlight the growing role of VR/AR in entrepreneurship education, tourism, and new venture creation, where these tools foster experiential learning, opportunity recognition, and sustainability-oriented innovation (Raman et al., 2025). By linking entrepreneurial intention to broader themes of digital transformation, these modalities provide scalable ways to build competencies and enhance motivation, reinforcing the university’s role in promoting sustainable entrepreneurship (Achuthan et al., 2020).

Importantly, the null moderation effect of Perceived Institutional Support (PIS) should be interpreted with caution. Substantively, it is possible that in our context informal sources of support (e.g., peers, mentors, role models) dominate over formal institutional mechanisms in shaping entrepreneurial pathways. Methodologically, restricted variance in the PIS measures and limited statistical power for interaction effects may also have obscured potential moderating influences. This combination suggests that institutional support may function less as a direct amplifier of motivation and more as part of broader ecosystem dynamics that were not fully captured in our model.

For moderation effects of Perceived Institutional Support (PIS), the results suggest that PIS did not significantly moderate the relationship between EM and EI, suggesting that institutional support alone may be insufficient to enhance entrepreneurial motivation’s impact on EI. This finding contrasts with studies that have found institutional support to be a key enabler of entrepreneurship, particularly in regions with strong regulatory and financial frameworks (Stephan et al., 2015; Karan et al., 2024). One possible reason for this discrepancy is the context-dependent nature of PIS. Prior research suggests that institutional support may only be effective when combined with other enabling conditions, such as access to funding, entrepreneurial networks, and favorable market conditions (Bazan, 2022; Bazan et al., 2020; Chahal et al., 2024): Furthermore, studies highlight that peer influence and entrepreneurial role models often have a stronger impact on EI than institutional support alone, reinforcing the importance of social capital and mentorship programs (Ferreira et al., 2016; Jardim et al., 2021; Porfírio et al., 2023).

This raises important questions regarding the true moderating role of institutional support. If PIS is not a direct moderator, it may function indirectly through ecosystem interactions, such as the availability of accelerators, incubators, and venture capital (Leitão et al., 2022; Qin, 2025).

Our ANOVA/T-tests found no significant effects for gender, age, or marital status; however, evidence of gender-specific pathways to sustainable entrepreneurial intention suggests that such effects may emerge in more diverse samples.

Future research could explore alternative moderators, including, among others, entrepreneurial ecosystems (e.g., funding availability, market access), Social capital (e.g., networking, mentorship), and Economic conditions (e.g., employment rates, industry growth).

Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be recognized. First, the present sample came from one university and includes relatively homogeneous students whose findings cannot be generalized. Second, performing this in self-collected data may still result in common-method bias despite our checks thereon. Third, being cross-sectional did not allow the inference of causality and thus the importance of longitudinal cohorts in investigating these relationships. Fourth, the PIS construct may not be exhaustive of its domain and extent of variation across contexts. Lastly, other mediators (e.g., entrepreneurial identity) or their correlated factors, like PBC in our study, were not included in the simultaneous model that could supplement an additional explanation.

All these considerations imply avenues for further study: multi-institutional and cross-cultural samples to add external validity; panel data or longitudinal design to estimate the dynamic processes from EM → EI → behavior; a more nuanced or comprehensive operationalization of PIS; comparative tests among mediators.

6. Future Research Directions

Given the mixed findings on PIS as a moderator, future studies should conduct longitudinal research to track how institutional support influences entrepreneurial intention over time. We now propose more concrete methodological designs: (a) panel designs tracking EM → EI → behavior over semesters; (b) multilevel models clustering students within courses/programs to test contextual PIS; (c) mixed-methods (PLS-SEM + qualitative interviews) to unpack mechanisms; and (d) experimental/field interventions with technology-mediated EE. Finally, we investigate how alternative mediators and moderators, such as entrepreneurial ecosystems, self-efficacy, and social capital, could enhance the refining of existing models.

7. Conclusions and Practical and Theoretical Implications

This study highlights the significant influence of Attitude Concerning Entrepreneurship (ACE), Perceived Social Norms (PSN), Entrepreneurial Education (EE), and Entrepreneurial Motivation (EM) in shaping Entrepreneurial Intention (EI). The findings confirm the central role of EM, not only as a direct determinant but also as a key mediator, reinforcing the relationship between individual, educational, and social factors and entrepreneurial behaviors. However, the non-significant moderation effect of Perceived Institutional Support (PIS) suggests that institutional support alone may be insufficient in strengthening entrepreneurial motivation, highlighting the need for alternative enabling factors such as entrepreneurial ecosystems, social capital, and mentorship networks. These results contribute to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by incorporating mediation and moderation analyses, offering a more nuanced understanding of how personal, educational, and institutional dynamics influence entrepreneurship.

From a practical perspective, these findings underscore the importance of entrepreneurship-focused education, policy interventions, and institutional strategies that go beyond formal support mechanisms. Tailored educational programs, experiential learning opportunities, and ecosystem-driven initiatives should be prioritized to foster a more dynamic entrepreneurial culture.

At the policy level, specific gaps remain, namely limited mentoring density, weak university–ecosystem brokerage, underfunded seed/mini-grant schemes, and fragmented support visibility. Addressing these gaps requires targeted mentorship networks, brokerage roles to connect universities with entrepreneurial ecosystems, and transparent one-stop support portals. Such measures would render recommendations more actionable, reflecting our null moderation finding for PIS. Concretely, university leaders and policymakers should prioritize: building visible mentorship networks; strengthening university–ecosystem brokerage; creating transparent one-stop portals for student entrepreneurs; and providing micro-grants and seed funding opportunities. These actionable steps ensure that policy recommendations are both practical and aligned with institutional contexts.

Future research should further explore the interplay between institutional support and broader ecosystem dynamics, investigating alternative moderators that may more effectively strengthen the link between motivation and entrepreneurial intention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, data curation and validation T.D.; supervision and software, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the Programme Contract UID/5105/2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institution (Polytechnic Institute of Cávado and Ave, Ipca, Portugal) has only an Ethical Committee since July 2025. (please see https://ipca.pt/informacao-institucional/comissao-de-etica/). The research was conducted in November 2024. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Polytechnic Institute of Cávado and Ave (IPCA), Portugal, in September 2024. All participants have been informed that their anonymity would be assured, the reason for the research, how their data would be used, and that no risks were involved. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects participating in the study. All participants were invited to participate in the study. Any participant was obliged to do it.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in 10.6084/m9.figshare.30479201.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdelwahed, N. A. A., & Alshaikhmubarak, A. (2023). Developing female sustainable entrepreneurial intentions through an entrepreneurial mindset and motives. Sustainability, 15(7), 6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abigael, O. A., Olusegun, O. O., & Olayiwola, O. M. (2024). Entrepreneurial education and intention as a Panacea for sustainable development goals: Evidenced among public and private university students in Southwest, Nigeria. Science, 12(4), 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achuthan, K., Nedungadi, P., Kolil, V., Diwakar, S., & Raman, R. (2020). Innovation adoption and diffusion of virtual laboratories. International Journal of Online and Biomedical Engineering (iJOE), 16(09), 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aga, M. K. (2023). The mediating role of perceived behavioral control in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakaleek, W., Harb, A., & Alzyoud, S. (2025). Toward a sustainable entrepreneurship future: Exploring sustainable entrepreneurial attitudes and intention among young women in an emerging economy. Social Enterprise Journal, 21(4), 668–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A., & Bhowmick, B. (2023). Examining the domains of entrepreneurial ecosystem framework—A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 13(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jubari, I., Hassan, A., & Liñán, F. (2019). Entrepreneurial intention among university students in Malaysia: Integrating self-determination theory and the theory of planned behavior. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(4), 1323–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkathiri, N. A., Said, F. B., Meyer, N., & Soliman, M. (2024). Knowledge management and sustainable entrepreneurship: A bibliometric overview and research agenda. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y. H. S., & Alraja, M. M. (2022). Understanding entrepreneurship intention and behavior in the light of TPB model from the digital entrepreneurship perspective. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(2), 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, A. S., Alholiby, M. S., Elshaer, I. A., Sobaih, A. E. E., & Al Marri, S. H. (2023). Examining the relationship between green mindfulness, spiritual intelligence, and environmental self identity: Unveiling the path to green entrepreneurial intention. Administrative Sciences, 13(10), 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2021). Knowledge complexity and firm performance: Evidence from the European SMEs. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(4), 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E., H. Keeley, R., Klofsten, M., GC Parker, G., & Hay, M. (2001). Entrepreneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterprise and Innovation Management Studies, 2(2), 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of personality. In Handbook of personality (2nd ed., pp. 154–196). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, R. M. A., Pérez-Nebra, A. R., Villajos, E., & González-Ladrón-De-Guevara, F. (2024). The entrepreneur’s well-being: Current state of the literature and main theories. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 14(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardales-Cárdenas, M., Cervantes-Ramón, E. F., Gonzales-Figueroa, I. K., & Farro-Ruiz, L. M. (2024). Entrepreneurship skills in university students to improve local economic development. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batz Liñeiro, A., Romero Ochoa, J. A., & Montes de la Barrera, J. (2024). Exploring entrepreneurial intentions and motivations: A comparative analysis of opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurs. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A., & Lucy, C. (2021). Enhancing entrepreneurial education: Developing competencies for success. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, C. (2022). Effect of the university’s environment and support system on subjective social norms as precursor of the entrepreneurial intention of students. Sage Open, 12(4), 21582440221129105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, C., Gaultois, H., Shaikh, A., Gillespie, K., Frederick, S., Amjad, A., Yap, S., Finn, C., Rayner, J., & Belal, N. (2020). A systematic literature review of the influence of the university’s environment and support system on the precursors of social entrepreneurial intention of students. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behfar, S. K., Shekhtman, L., & Crowcroft, J. (2024). Competitive funding and academic-industry collaboration: Policy trends and insights. Data & Policy, 6, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsrud, A. L., Olm, K. W., & Thomas, J. B. (1989). Predicting entrepreneurial success: Effects of multi-dimensional achievement motivation, levels of ownership, and cooperative relationships. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 1(3), 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Carrion, I., Ortega-Gutierrez, J., Garrido-Moreno, A., & Cegarra-Navarro, J. G. (2023). The mediating role of knowledge creation processes in the relationship between social media and open innovation. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 14(2), 1275–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, J., Shoukat, M. H., & Ayoubi, R. (2024). How entrepreneurial environment and education influence university students’ entrepreneurial intentions: The mediating role of entrepreneurial motivation. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 14(3), 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs. PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P., Recker, J., & von Briel, F. (2025). External enablement of entrepreneurial actions and outcomes: Extension, review and research agenda. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 21(3), 172–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P., Secundo, G., Mele, G., & Passiante, G. (2021). Sustainable entrepreneurship education for circular economy: Emerging perspectives in Europe. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(8), 2096–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieguez, T. (2021). COVID-19: Uma oportunidade para desenvolver a Intenção empreendedora. ICIEMC Proceedings, 8(2), 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dieguez, T., Au-Yong-Oliveira, M., Sobral, T., & Jacquinet, M. (2021). Entrepreneurship and changing mindsets: A success story. In Proceedings of the international conferences-internet technologies & society (ITS 2021). Applied management advances in the 21st century 2021 (AMA21 2021) and sustainability, technology and education 2021 (STE 2021) (pp. 111–116). IADIS. [Google Scholar]

- Dieguez, T., Loureiro, P., Ferreira, S. I., & Basto, M. (2024). Transformative forces: Social entrepreneurship as key competency. International Journal of Innovation and Economic Development, 10(1), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieguez, T., Sobral, T., & Conceição, O. (2023). Entrepreneurial intention acknowledgment in sustainable entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Journal of Innovation Management, 11(2), 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E. J., Shepherd, D. A., & Venugopal, V. (2021). A multi-motivational general model of entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(4), 106107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ephrem, A. N., Nguezet, P. M. D., Charmant, I. K., Murimbika, M., Awotide, B. A., Tahirou, A., Lydie, M. N., & Manyong, V. (2021). Entrepreneurial motivation, psychological capital, and business success of young entrepreneurs in the drc. Sustainability, 13(8), 4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K., Sharifi-Tehrani, M., Pratt, S., & Altinay, L. (2019). Understanding entrepreneurial intentions: A developed integrated structural model approach. Journal of Business Research, 94, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2008). From craft to science: Teaching models and learning processes in entrepreneurship education. Journal of European Industrial Training, 32(7), 569–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C., Ferreira, J. J., Veiga, P. M., Kraus, S., & Dabić, M. (2022). Digital entrepreneurship platforms: Mapping the field and looking towards a holistic approach. Technology in Society, 70, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. J., Fernandes, C. I., & Ratten, V. (2016). The influence of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions. In Entrepreneurial universities: Exploring the academic and innovative dimensions of entrepreneurship in higher education (pp. 19–34). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Neto, M. N., de Carvalho Castro, J. L., de Sousa-Filho, J. M., & de Souza Lessa, B. (2023). The role of self-efficacy, entrepreneurial passion, and creativity in developing entrepreneurial intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1134618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazi, M. A. I., Rahman, M. K. H., Yusof, M. F., Masud, A. A., Islam, M. A., Senathirajah, A. R. B. S., & Hossain, M. A. (2024). Mediating role of entrepreneurial intention on the relationship between entrepreneurship education and employability: A study on university students from a developing country. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2294514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, D. A., Cornelissen, J., Dimov, D., & Van Burg, E. (2015). The mind in the middle: Taking stock of affect and cognition research in entrepreneurship. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(2), 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., & Alamer, A. (2022). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoda, B. (2025). Extracurricular activities for entrepreneurial learning: A typology based on learning theories. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 8(1), 142–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A., Anwar, I., Saleem, I., Islam, K. B., & Hussain, S. A. (2021). Individual entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of entrepreneurial motivations. Industry and Higher Education, 35(4), 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D., Mosakowski, E., & Earley, P. C. (2010). A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. I., Tabash, M. I., Siow, M. L., Ong, T. S., & Anagreh, S. (2023). Entrepreneurial intentions of Gen Z university students and entrepreneurial constraints in Bangladesh. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardim, J., Bártolo, A., & Pinho, A. (2021). Towards a global entrepreneurial culture: A systematic review of the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education programs. Education Sciences, 11(8), 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A., Ergulec, F., & Eren, E. (2024). The mediating role of self-regulated online learning behaviors: Exploring the impact of personality traits on student engagement. Education and Information Technologies, 29(17), 23517–23546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, A., Singh, M., & Rana, N. P. (2024). Does entrepreneurial motivation influence entrepreneurial intention? Exploring the moderating role of perceived supportive institutional environment on Indian university students. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 20(1), 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvereid, L. (1996). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21(1), 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiterling, C. (2023). Digital innovation and entrepreneurship: A review of challenges in competitive markets. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F., Jr., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C., & Liu, C. (2019). The entrepreneurial motivations, cognitive factors, and barriers to become a fashion entrepreneur: A direction to curriculum development for fashion entrepreneurship education. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 12(2), 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. Y., & Tsang, E. W. (2001). The effects of entrepreneurial personality, background and network activities on venture growth. Journal of Management Studies, 38(4), 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L., Wong, P. K., Der Foo, M., & Leung, A. (2011). Entrepreneurial intentions: The influence of organizational and individual factors. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(1), 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, J., Pereira, D., & Gonçalves, Â. (2022). Business incubators, accelerators, and performance of technology-based ventures: A systematic literature review. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linan, F. (2008). Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(3), 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Sánchez, L. M., Salcedo Plazas, L. A., & Rodríguez Ariza, L. (2024). The influence of emotional competencies on the entrepreneurship intentions of university students in Colombia. Sustainability, 16(22), 9933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, A., & Schwarzer, R. (2015). Social cognitive theory (Vol. 2015, pp. 225–251). Faculty of Health Sciences Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Malin, J. R., Brown, C., Ion, G., van Ackeren, I., Bremm, N., Luzmore, R., Flood, J., & Rind, G. M. (2020). World-wide barriers and enablers to achieving evidence-informed practice in education: What can be learnt from Spain, England, the United States, and Germany? Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cañas, R., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Jiménez-Moreno, J. J., & Linuesa-Langreo, J. (2023). Push versus pull motivations in entrepreneurial intention: The mediating effect of perceived risk and opportunity recognition. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 29(2), 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziriri, E. T., Dzingirai, M., Nyagadza, B., & Mabuyana, B. (2024). From perceived parental entrepreneurial passion to technopreneurship intention: The moderating role of perseverance and perceived parental entrepreneurial rewards. Sustainable Technology and Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, F. J., Chamorro-Mera, A., & Rubio, S. (2017). Academic entrepreneurship in Spanish universities: An analysis of the determinants of entrepreneurial intention. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 23(2), 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A., & Singh, P. (2024). Effect of emotional intelligence and cognitive flexibility on entrepreneurial intention: Mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 16(3), 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N. A., & Sheikh Ali, A. Y. (2021). Entrepreneurship education: Systematic literature review and future research directions. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 17(4), 644–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyo, I., & Veiga, L. (2024). Entrepreneurship and economic growth. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(1), 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, I., Manohar, S., Mittal, A., & Nair, A. J. (2024). Thought clarity to execution chaos: A review on core competencies of grassroots entrepreneurs for instigation, growth and sustainability of startups. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W., & Haddoud, M. Y. (2019). The role of inspiring role models in enhancing entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Research, 96, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, I., & Deimel, K. (2025). Revisiting the role of behavioral control and entrepreneurial identity in empirical entrepreneurial intention research: A theory of planned behavior approach. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 6(3), 436–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfírio, J. A., Felício, J. A., Carrilho, T., & Jardim, J. (2023). Promoting entrepreneurial intentions from adolescence: The influence of entrepreneurial culture and education. Journal of Business Research, 156, 113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praditya, R. A., & Purwanto, A. (2024). Linking The influence of dynamic capabilities and innovation capabilities on competitive advantage: PLS-SEM analysis. PROFESOR: Professional Education Studies and Operations Research, 1(02), 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, F. (2025). Oasis in the desert or icing on the cake? The impact of entrepreneurship accelerators across ecosystems. Journal of International Business Studies, 56, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakicevic, Z., Njegic, K., Cogoljevic, M., & Rakicevic, J. (2023). Mediated effect of entrepreneurial education on students’ intention to engage in social entrepreneurial projects. Sustainability, 15(5), 4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R., Kowalski, R., & Achuthan, K. (2025). Metaverse technologies and human behavior: Insights into engagement, adoption, and ethical challenges. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 19, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Colmenares, L. M., & Reyes-Rodríguez, J. F. (2022). Sustainable entrepreneurial intentions: Exploration of a model based on the theory of planned behaviour among university students in north-east Colombia. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, D. K., Pawar, S., Gaur, P., & Jain, S. K. (2023). Academic’s motivation for entrepreneurial engagement: A systematic literature review. Journal of Operations and Strategic Planning, 6(2), 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., & Cheah, J. H. (2019). Partial least squares structural equation modeling using SmartPLS: A software review. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 7, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2017). Treating unobserved heterogeneity in PLS-SEM: A multi-method approach. In Partial least squares path modeling: Basic concepts, methodological issues and applications (pp. 197–217). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W. R. (2005). Institutional theory: Contributing to a theoretical research program. In Great minds in management: The process of theory development (pp. 460–484). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Semrau, T., Ambos, T., & Kraus, S. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation and SME performance across societal cultures: An international study. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1928–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D. A., Wennberg, K., Suddaby, R., & Wiklund, J. (2019). What are we explaining? A review and agenda on initiating, engaging, performing, and contextualizing entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 45(1), 159–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J. H., Ting, H., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. European Journal of Marketing, 53(11), 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A. E. E., & Elshaer, I. A. (2022). Personal traits and digital entrepreneurship: A mediation model using SmartPLS data analysis. Mathematics, 10(21), 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S., & Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(4), 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U., Uhlaner, L. M., & Stride, C. (2015). Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. Journal of International Business Studies, 46, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurik, A. R., Audretsch, D. B., Block, J. H., Burke, A., Carree, M. A., Dejardin, M., Rietveld, C. A., Sanders, M., Stephan, U., & Wiklund, J. (2024). The impact of entrepreneurship research on other academic fields. Small Business Economics, 62(2), 727–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D., El Chaarani, H., El Nemar, S., EL-Abiad, Z., Ali, R., & Trichina, E. (2022). The motivation behind an international entrepreneurial career after first employment experience. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 28(3), 654–675. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, S. G., & Block, J. H. (2016). Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A. (1994). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation: A developmental perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 6, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (Eds.). (2002). Development of achievement motivation. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, H. (1982). Models for knowledge. In The making of statisticians (pp. 189–212). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, F. K., Jiang, K., Combs, D. R., & Chang, S. (2022). Informal institutions and absorptive capacity: A cross-country meta-analytic study. Journal of International Business Studies, 53(6), 1091–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W., Jiang, M., & Li, H. (2023). Explaining academic entrepreneurial motivation in China: The role of regional policy, organizational. Small Business Economics, 61, 1357–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]