Abstract

This study investigates digital literacy thresholds within South African higher education institutions in the context of Industry 4.0, focusing on entrepreneurship education. The research addresses the critical gap between current digital competencies and Industry 4.0 requirements, challenging assumptions about “digital natives” and examining factors influencing digital literacy development. A qualitative methodology employing semi-structured interviews was conducted with 25 participants, including 11 faculty members and 14 entrepreneurship students from a South African higher education institution. Data underwent rigorous thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke’s six-phase approach. The study revealed significant disparities in digital competencies among both faculty and students, contradicting binary digital native classifications. Key findings identified distinct transformative thresholds separating performative digital interaction from entrepreneurial digital practice, with access, training, and motivation forming interconnected factors in a digital literacy ecosystem. Most participants demonstrated bounded digital fluency limited to familiar environments rather than transferable entrepreneurial capabilities. The research introduces novel theoretical contributions, including “entrepreneurial digital thresholds” and “digital literacy structuration,” advocating for contextually responsive frameworks addressing socioeconomic inequalities. Practical implications include targeted professional development, multidimensional assessments, and policies prioritising equitable digital participation to prepare graduates for meaningful engagement in the global digital economy rather than passive consumption.

1. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (Industry 4.0) presents unprecedented challenges and opportunities for higher education institutions (HEIs) worldwide, with particular complexities in the South African context, where technological advancement intersects with persistent socioeconomic inequalities (). This study examines the critical but underexplored dimension of digital literacy thresholds within entrepreneurship education (EE) programs, revealing a complex landscape where technological competence varies significantly among both faculty and students. We observed that while some participants demonstrate advanced digital capabilities, many exhibit only rudimentary skills that fall short of Industry 4.0 requirements, pointing to a significant gap between current educational practices and industry expectations.

The central argument of this paper is that South African HEIs must develop contextually responsive digital literacy frameworks that acknowledge local realities while preparing students for global participation. Thus, our study challenges the prevailing assumption that technological exposure automatically translates to meaningful digital literacy; instead, it reveals a multifaceted ecosystem where access, training, motivation, and pedagogical integration collectively determine digital competence levels. We contend that effective digital literacy development requires moving beyond the binary classification of “digitally literate” versus “digitally illiterate” toward a more nuanced understanding of the spectrum of capabilities required for entrepreneurial success in the digital economy.

As our study demonstrates, the gap between performative digital interaction (such as social media usage) and transformative digital competence (leveraging advanced technologies for entrepreneurial innovation) represents a critical threshold that many South African students and academics struggle to cross. Through our investigation, we examine these thresholds through the lens of EE; hence, our study offers valuable insights into how higher education can more effectively bridge theoretical digital knowledge with practical application in entrepreneurial contexts. We are convinced that this perspective not only addresses South Africa (SA)’s specific developmental priorities but also contributes to broader discussions about preparing graduates for meaningful participation in the rapidly evolving global digital economy. Based on these considerations, this study addresses three research questions:

- RQ1:

- What are the current digital literacy levels among faculty and students in South African entrepreneurship education programs?

- RQ2:

- What factors influence the development of digital literacy competencies in the context of Industry 4.0?

- RQ3:

- What specific digital literacy thresholds must be crossed for effective entrepreneurial practice in the digital economy?

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Digital Literacy in Higher Education

Digital literacy has undergone a radical transformation, transcending basic technical proficiencies to encompass a sophisticated assemblage of capabilities essential for meaningful participation in digitally mediated environments (; ). This transformation demands questioning as competing conceptual frameworks offer fundamentally divergent pathways for educational praxis. It is worth noting that, although dominant conversations often position digital literacy as a neutral skillset, we argue that this perspective requires contestation. On the other hand, the socio-material approach advocated by () convincingly reframes digital literacy as embedded academic practice rather than decontextualised competencies. It has become a truism to observe that there has been an evolution of conceptual thinking in terms of how HEIs might address digital literacy education. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified recognition of digital literacy’s critical importance. As () observe, “the abrupt transition from face-to-face to online education has created the need for some specific abilities, such as digital literacy on the side of the learners at all educational levels.” This shift revealed not only immediate practical needs but also long-term implications for educational policy and practice.

The South African context presents unique complexities that challenge internationally derived models. ’s () research demonstrates how digital practices remain profoundly shaped by historical inequalities and structural constraints, with technologies often reproducing rather than disrupting social stratifications. () similarly reveal a complex “digital continuum” of access and capability fundamentally shaped by socioeconomic positioning, rather than a simple binary divide.

’s () work on “digital habitus” provides compelling evidence that differential technology access creates stratified dispositions significantly impacting academic performance. Drawing on Bourdieusian concepts of capital, this framework shows how conventional digital interventions often perpetuate inequality by privileging dominant technological dispositions. ’s () call for decolonised digital pedagogies that acknowledge indigenous knowledge systems alongside global technological practices offers a crucial corrective to Western-centric digital literacy discourse.

2.2. Industry 4.0 and Entrepreneurship Education

Given that Industry 4.0 has set an unprecedented technological reconfiguration characterised by the convergence of digital systems, physical infrastructure, and algorithmic governance, it has fundamentally restructured economic activity and labour requirements (). This tells us that the entrepreneurial landscape is also impacted. Be that as it may, it is important; we must recognise that this technological revolution generates profound contradictions documented through robust empirical investigation. In particular, ’s () Global Entrepreneurship Monitor data reveals this paradox, while digital platforms reduced initial capital requirements, only 23% of South African entrepreneurs reported sufficient digital capabilities for Industry 4.0 technologies, compared to 47% globally. This disparity challenges techno-optimist narratives of digital democratisation and exposes a disconnect between Western-derived theoretical frameworks, which assume universal digital infrastructure and literacy, and South African realities characterised by structural inequalities and inadequate digital education systems (). This understanding is crucial as this disconnect manifests in the implementation gap between theoretical digital entrepreneurship potential and the lived experience of South African students navigating a complex digital divide. As a result, our study demonstrates the necessity of what we term “contextually responsive digital entrepreneurship education” that acknowledges SA’s unique digital entrepreneurship landscape. The key implication drawn from this perspective represents not merely practical adaptation but a fundamental theoretical reorientation that positions digital entrepreneurship within specific socio-technical systems rather than abstract technological imperatives.

2.3. Digital Literacy Thresholds

Our discussion further highlights the threshold concept framework, which originates from ’s () seminal epistemological analysis. This offers a particularly generative lens for examining digital literacy development within EE. However, the application of threshold theory to digital domains requires examination. Hence, ’s () study provides compelling evidence that conventional threshold applications frequently privilege cognitive aspects while neglecting equally crucial affective and identity dimensions of digital transformation. We should stress that these threshold transformations involve cognitive and affective changes, altering how individuals understand and experience the world, as argued by ().

Although we cannot precisely predict how digital literacy thresholds in EE delineate critical transition points where faculty and students transcend passive consumption to achieve strategic deployment of digital technologies for value creation, we aim to provide convincing arguments supporting this perspective. Based on our understanding, the acquisition of digital competencies follows a non-linear progression with distinct phases followed by accelerated capability development. Undoubtedly, these capability inflection points frequently coincide with what () characterise as “threshold concepts”, a transformative portal that fundamentally alters students’ perception of their technological agency. Moreover, studies by () demonstrate that once students cross certain cognitive boundaries in their digital literacy development, they exhibit distinctly different behaviour patterns, shifting from technology utilisation to technology orchestration. This transformation aligns with ’s () constructionist framework, wherein learners progress from “using the tool” to “thinking with the tool” as their conceptual framework evolves.

’s () research substantiates the educational significance of these thresholds, showing that students who navigate critical transitions demonstrate substantially enhanced innovative capacity compared to peers at pre-threshold literacy levels. This positions digital literacy development not as cumulative skill acquisition but as epistemological transformation, aligning with EE’s broader transformative aims while demanding theoretical adaptation for South Africa’s diverse digital starting points.

3. Methodology and Scope

3.1. Research Design and Approach

As we reflected on various methodological choices, we decided to employ an interpretive qualitative methodology to investigate digital literacy levels among faculty members and students within EE contexts. From our perspective, a qualitative approach was selected based on its capacity to capture rich contextual data and facilitate in-depth exploration of participants’ lived experiences and perceptions regarding digital literacy (; ). Therefore, the research design followed a phenomenological orientation seeking to understand how participants make meaning of their experiences with digital technologies in entrepreneurial learning environments ().

Semi-structured interviews served as the primary data collection method, allowing for both systematic inquiry across predetermined topics and flexibility to explore emergent themes (). This approach facilitated a thorough investigation of participants’ digital literacy competencies, challenges, and adaptation strategies within South African HEIs.

3.2. Participants and Sampling

The study employed a two-tier purposive sampling strategy to ensure representation from key stakeholder groups. Participants included both faculty members (n = 11, denoted as FM1–FM11) and entrepreneurship students (n = 14, denoted as ES1–ES14) from a South African HEI. Although the sample seems so limited for this study, based on our professional judgement, this sample size aligns perfectly with qualitative research principles where depth of insight takes precedence over statistical power. As we considered methodological rigour, the purposive sampling strategy employed in our study prioritises information-rich cases that yield detailed understandings of the phenomenon rather than statistical generalisability. From our experience in qualitative inquiry, a sample of 25 heterogeneous participants is sufficient to achieve theoretical saturation in phenomenological studies, especially when maximum variation sampling techniques are applied as noted in the methodology. We firmly believe this carefully constructed sample provides enough diversity across technological proficiency levels, academic ranks, student educational stages, and socioeconomic backgrounds to capture the essential variations in digital literacy experiences. The selection criteria for faculty members included the following:

- Minimum three years of experience teaching entrepreneurship-related courses.

- Diverse technological expertise levels.

- Representation across different academic ranks.

For students, the selection criteria encompassed the following:

- Current enrollment in entrepreneurship programs.

- Varying academic levels (undergraduate and postgraduate)

- Diversity in demographic backgrounds and digital exposure.

Maximum variation sampling techniques () were applied to capture experiences across different technological proficiency levels, academic disciplines, and socioeconomic backgrounds. In this regard, we are convinced this sample size strikes the optimal balance between breadth and depth, allowing for rich, nuanced exploration of digital literacy in EE contexts while remaining manageable for rigorous phenomenological analysis as prescribed by () and supported by qualitative methodologists like ().

3.3. Data Collection Procedures

The initial data collection occurred between October 2022 and January 2023. Semi-structured interviews (45–60 min) were conducted with all participants using a standardised interview protocol that was pilot tested with two faculty members and two students not included in the final sample. The protocol explored four key domains: (1) participants’ digital literacy competencies and self-efficacy, (2) experiences with digital technologies in entrepreneurship contexts, (3) perceived barriers and facilitators to digital technology integration, and (4) perceptions of Industry 4.0 skill requirements ().

To enhance data quality, following the thesis submission, an opportunity arose to enhance the robustness and comprehensiveness of the findings through additional data collection, conducted from May to August 2024, which added 8 more participants to the study. This methodological enhancement represents a natural progression from doctoral research to publication, reflecting the iterative nature of qualitative inquiry and the commitment to producing the most comprehensive analysis possible for scholarly dissemination. Complementary data sources were utilised, including document analysis of course materials and institutional digital literacy frameworks. All interviews were audio-recorded with participants’ informed consent and transcribed verbatim for analysis, with member checking employed to verify transcript accuracy.

3.4. Data Analysis

The collected data underwent rigorous thematic analysis following ’s () systematic six-phase approach:

- Familiarisation with data through repeated reading;

- Generating initial codes using ATLAS. ti software;

- Searching for themes by clustering related codes;

- Reviewing themes against the entire dataset;

- Defining and naming themes;

- Producing the final report.

Initial coding employed both deductive codes derived from existing digital literacy frameworks () and inductive codes emerging from the data. A constant comparative method was applied throughout the analysis process to identify patterns, contradictions, and relationships across participant groups ().

The analysis was guided by the research objective of assessing digital literacy levels among faculty members and students while exploring the implications for EE in South African contexts, and analytical memos were maintained throughout to document emergent insights and theoretical connections ().

4. Findings

4.1. Divergent Levels of Digital Competence: Beyond the Digital Native Paradigm

The study revealed significant variations in digital literacy competencies among both faculty members and students, challenging ’s () binary classification of digital natives and immigrants. This heterogeneity manifested not only between the two groups but also within each cohort, aligning with ’s () critique of deterministic technological assumptions in higher education.

Among faculty members, FM2, FM3, FM5, FM7, and FM9 demonstrated notable proficiency in understanding and utilising Industry 4.0 digital technologies, reflecting what () term Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK):

As one participant noted:

“I have integrated digital simulation tools and analytics platforms into my entrepreneurship modules, allowing students to experience virtual market testing and data-driven decision-making.”(FM3)

This integration represents the highest level of digital competence, where technology becomes seamlessly incorporated into pedagogical practice as described by (). In contrast, FM1 and FM10 exhibited limitations in applying digital technologies to practical entrepreneurship scenarios:

“I understand the importance of these new technologies but translating them into meaningful learning experiences for students remains challenging.”(FM4)

This gap between theoretical knowledge and implementation capabilities exemplifies what () identified as second-order barriers to technology integration, specifically, pedagogical beliefs and confidence that constrain practical application.

Similar divergence was observed among students with ES1, ES2, ES4, ES5, ES9, and ES13, demonstrating foundational digital literacy skills. However, most students exhibited what we conceptualise as “bounded digital fluency”, a competence within familiar digital environments (social media & learning platforms) but limited ability to transfer these skills to entrepreneurial contexts. This finding contradicts the assumption that contemporary students naturally possess transferable digital capabilities, supporting ’s () contention that domain-specific digital literacy requires intentional development.

Analysis of faculty participants revealed three distinct competence levels, as illustrated in Table 1 above. Among the 11 faculty members, 5 (45%) demonstrated advanced proficiency in understanding and utilising Industry 4.0 digital technologies, reflecting what () term Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK). These faculty members (FM2, FM3, FM5, FM7, and FM9) successfully integrated sophisticated digital tools into their entrepreneurship pedagogy:

“I’ve integrated digital simulation tools and analytics platforms into my entrepreneurship modules, allowing students to experience virtual market testing and data-driven decision-making.”(FM3)

Table 1.

Faculty digital competence distribution (n = 11).

This integration represents the highest level of digital competence where technology becomes seamlessly incorporated into pedagogical practice, as described by (). Conversely, six faculty members (55%) exhibited moderate to limited competence, characterised by a gap between theoretical knowledge and implementation capabilities.

This gap exemplifies what () identified as second-order barriers to technology integration—specifically, pedagogical beliefs and confidence constraints that impede practical application despite theoretical understanding.

Similar divergence was observed among student participants in Table 2, revealing a more complex competence landscape than traditional digital native assumptions suggest. As shown in Table 1, while six students (43%) demonstrated foundational digital literacy skills suitable for entrepreneurial contexts (ES1, ES2, ES4, ES5, ES9, and ES13), the majority exhibited what we conceptualise as “bounded digital fluency”, competence within familiar digital environments (social media & learning platforms) but limited ability to transfer these skills to entrepreneurial applications. This finding contradicts the assumption that contemporary students naturally possess transferable digital capabilities, supporting ’s () contention that domain-specific digital literacy requires intentional development rather than emerging organically from generational exposure.

Table 2.

Student digital competence profile (n = 14).

4.2. Factors Influencing Digital Literacy Development: An Ecological Perspective

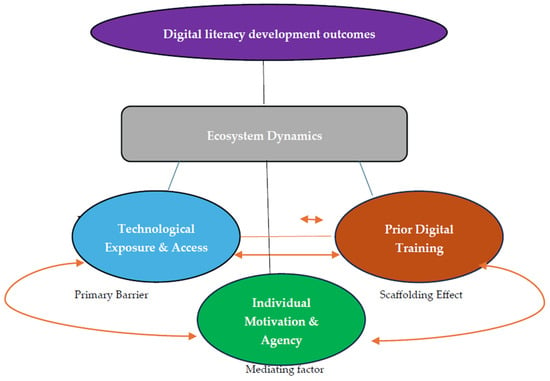

Our study identified several interconnected factors that significantly influence digital literacy development among participants, forming what we describe as a digital literacy ecosystem (; ).

4.2.1. Technological Access and Exposure: Reconceptualising Digital Divides

Disparities in access to digital devices and reliable internet connectivity emerged as a significant determinant of digital literacy levels, supporting ’s () multifaceted model of digital divides:

“Inconsistent internet access at home means I often cannot practice using online business tools outside of campus hours.”(ES11)

Our study extends beyond what () call “digital access” to encompass what we identify as “effective access”, which is the quality, consistency, and context of technological engagement that determines meaningful digital participation. Therefore, the South African context introduces particular complexities in this regard, aligning with ’s () research on how socioeconomic factors create distinctive patterns of digital inequality in post-apartheid higher education.

4.2.2. Prior Digital Training: The Scaffolding Effect

Formal and informal digital training experiences significantly shaped participants’ digital literacy trajectories.

“The professional development workshop on digital business tools transformed my teaching approach. I now incorporate data visualisation and digital marketing elements into my entrepreneurship modules.”(FM5)

This finding challenges assumptions about incidental digital learning. While () argue that learning can occur without explicit instruction to attend to presented information, our findings suggest that targeted training is particularly effective for entrepreneurial digital literacy development. This aligns with what () term “legitimate peripheral participation” in communities of digital practice, which appears essential for developing contextualised digital capabilities.

4.2.3. Individual Motivation and Agency: The Self-Efficacy Factor

Participant motivation emerged as a powerful mediating factor that could either amplify or mitigate the effects of access limitations and training opportunities:

“Despite initially having limited exposure to digital tools, I sought out online courses and tutorials to develop the skills I need for my business idea.”(ES14)

This finding expands ’s () self-efficacy theory to digital entrepreneurship contexts and aligns with ’s () research on digital agency in South African higher education. It demonstrates what () terms “structuration”, which is the interplay between structural constraints and individual agency, significantly shaping digital literacy development trajectories.

Figure 1 below identifies three interconnected factors that significantly influence digital literacy development among participants, forming what we describe as a digital literacy ecosystem. Rather than operating in isolation, these factors interact dynamically to either enable or constrain digital competence development, as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

The digital literacy ecosystem: three-dimensional interaction model. Source: illustration by authors.

4.3. Contextual Digital Literacy Requirements for Entrepreneurship Education: Domain-Specific Competencies

The study revealed specific digital literacy requirements unique to the EE context, challenging generic approaches to digital literacy development in higher education and supporting ’s () conceptualisation of multiple, contextualised digital literacies.

4.3.1. Industry-Aligned Digital Competencies: Bridging Academic-Industry Divides

Participants emphasised the need for digital skills that directly translate to entrepreneurial practice:

“Understanding social media analytics for business decision-making is far more valuable for my entrepreneurial journey than general computer literacy.”(ES9)

As such, digital entrepreneurship research by () is reinforced by our findings, demonstrating how digital technologies fundamentally transform entrepreneurial processes rather than merely enhancing them. The evidence suggests that effective digital literacy development in EE requires alignment with what () argue as “design thinking and a methods approach”, which emphasises a practical approach where students step outside the classroom.

4.3.2. Integration of Theory and Practice: Experiential Learning for Digital Competence

Both faculty members and students identified experiential learning as critical for developing meaningful digital literacy in entrepreneurship contexts:

“The most significant digital learning happens when students apply technologies to solve real entrepreneurial problems, not when they merely learn about the technologies in abstract.”(FM8)

This finding extends ’s () experiential learning theory to digital literacy development and supports ’s () argument that EE requires practice-based approaches. It suggests that what Schön (1979) terms “reflection-in-action” during authentic technological engagement may be particularly important for developing the adaptive digital capabilities required for entrepreneurial innovation.

4.3.3. Advanced Technological Capabilities: Threshold Competencies in Industry 4.0

Participants recognised the growing importance of advanced digital competencies for entrepreneurial success in Industry 4.0:

“Understanding how to leverage AI and big data is not optional anymore for entrepreneurs, it’s becoming a baseline requirement for competitive advantage.”(FM2)

This finding aligns with ’s () research on digital entrepreneurship in Industry 4.0 and extends Schwab’s (2016) conceptualisation of Industry 4.0 competencies to EE contexts. It indicates an emerging threshold between what () would classify as Bloom’s Taxonomy, which has been widely used to structure curriculum learning objectives, assessments, and activities.

4.4. Challenges in Assessing Digital Literacy: Toward Nuanced Evaluation

We highlight significant complexities in evaluating digital literacy levels within contemporary higher education contexts where technology use is ubiquitous but often superficial.

4.4.1. Beyond Binary Classification: Multidimensional Taxonomies

Participants’ experiences revealed the inadequacy of binary classifications in capturing the nuanced spectrum of digital capabilities:

“A student may be highly proficient with social media but struggle to analyse digital market data or create compelling online content for business purposes.”(FM7)

This supports the argument by () for multidimensional digital competence frameworks and extends Bloom’s revised taxonomy to digital entrepreneurship contexts. It suggests the need for assessment approaches that recognise what () term the “sociocultural” dimension of digital literacies and how they manifest differently across varied domains of practice.

4.4.2. Performance vs. Capability Gap: The Zone of Proximal Digital Development

The research identified a notable gap between demonstrated digital performance (what participants currently do with technology) and digital capability (what they could potentially do with appropriate support and motivation):

“I know there are digital tools that could help scale my business idea, but I do not feel confident exploring them without guidance.”(ES3)

This finding directly applies ’s () zone of proximal development to digital literacy assessment and aligns with ’s () visitor-resident continuum of digital engagement. It challenges assessment approaches focused exclusively on observable behaviours and suggests the importance of what () terms a “growth mindset” perspective that recognises developmental potential rather than fixed digital traits.

5. Discussion

5.1. Reimagining Digital Literacy Thresholds for South African Entrepreneurship Education: A Transformative Framework

Our findings challenge prevailing conceptualisations of digital literacy in higher education by revealing distinct thresholds that separate performative digital interaction from transformative digital practice in entrepreneurial contexts. These thresholds extend beyond technical skills to encompass critical thinking, creative application, and strategic deployment of digital technologies for entrepreneurial value creation, aligning with ’s () threshold concepts theory.

The identified variation in digital literacy levels among both faculty and students contradicts deterministic assumptions about digital natives and immigrants () that have often influenced higher education policies. Instead, our findings align with ’s () research on digital diversity in South African higher education, which demonstrates how age-based digital stereotypes fail to capture the complex interrelationship between socioeconomic positioning, educational opportunity, and technological engagement. However, this study extends previous research by introducing a novel theoretical contribution by identifying specific transformative thresholds within the EE context that determine whether individuals can effectively leverage digital technologies for entrepreneurial purposes.

The first critical threshold appears at the juncture between passive digital consumption and active digital creation for entrepreneurial purposes. This threshold represents what () would classify as a shift from brute facts about technology (knowing how to use digital tools) to “institutional facts” (recognising how these tools acquire specific meanings and functions within entrepreneurial contexts). While most participants demonstrated comfort with consumption-oriented activities, significantly fewer exhibited capabilities in creative digital production. This threshold aligns with what () labels the creative element of digital literacy, but contextualises it specifically within entrepreneurial practice, extending ’s () distinction between productive and unproductive entrepreneurship to digital domains.

5.2. The Mediating Role of Contextual Factors: A Structuration Perspective

The identified factors influencing digital literacy development, technological access, prior training, and individual motivation interact in complex ways that both reflect and potentially reinforce existing socioeconomic disparities in South African higher education. Our findings reveal that these factors form what () would term a “structuration system” where structural constraints and individual agency recursively shape digital literacy development pathways.

The relationship between technological access and digital literacy development extends beyond what we express as “material access” to encompass what () identifies as “usage access”, which encompasses the opportunities, time, and contexts available for meaningful digital engagement. Hence, our study contributes to this literature by demonstrating how access limitations specifically impact entrepreneurial digital capabilities. The finding that inconsistent access impedes the development of entrepreneurial digital workflows suggests what () terms “episodic access”, which may be insufficient for developing the sustained digital practices necessary for entrepreneurial success in Industry 4.0.

The significance of prior digital training challenges the mythological assumption that digital literacy develops naturally through general technology use. This finding aligns with ’s () research on the importance of intentional digital literacy development but extends it by identifying the specific value of entrepreneurially contextualised digital training. The experiences of faculty members who successfully integrated digital technologies into their teaching following targeted professional development suggest that digital literacy for entrepreneurship requires “specialised pedagogical content knowledge” rather than generic technological familiarity.

Perhaps most significantly, our findings regarding individual motivation introduce what can be termed “digital self-efficacy” as a critical mediating factor in digital literacy development. This extends ’s () self-efficacy theory to digital entrepreneurship contexts and aligns with ’s () self-determination theory, suggesting that fostering autonomous motivation for digital engagement may be as important as providing technological resources for developing entrepreneurial digital literacy. This theoretical extension offers a novel perspective on how individual agency operates within structural constraints in digital literacy ecosystems.

5.3. Implications for Entrepreneurship Education in Industry 4.0: Pedagogical Transformation

The identified gap between current digital literacy levels and Industry 4.0 requirements has profound implications for EE in South African HEIs. Our findings suggest that traditional approaches to digital literacy development, which often focus on technical competence rather than critical and creative application, may be insufficient for preparing students for entrepreneurial success in the digital economy.

The divergent digital literacy levels among faculty members raise particular concerns about institutional readiness to deliver Industry 4.0-aligned EE. This finding challenges the “assumption of capability” often made about educators and extends the research of () on EE in SA by highlighting a specific capability gap related to digital integration. The struggle of some faculty members to implement digital technologies in entrepreneurial contexts suggests what we would identify as a critical need for professional development that addresses not just technical skills but also pedagogical beliefs and attitudes toward technology.

The predominantly passive approach to digital technologies exhibited by many student participants indicates a “participation gap”, which is a disparity not just in access but in the capacities to meaningfully participate in digital culture. This finding contradicts assumptions about students as “digital natives” () and instead aligns with more nuanced understandings of digital engagement patterns (). However, our study extends this understanding by identifying specific thresholds between passive digital consumption and active entrepreneurial digital creation that education programs must help students traverse, what () term the transformative learning transitions.

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.1. Theoretical Contributions: Advancing Digital Literacy Discourse

This study makes several significant contributions to theoretical understandings of digital literacy in higher education contexts. First, it extends threshold concept theory () to digital literacy development by identifying specific transformative thresholds that separate performative digital interaction from entrepreneurial digital practice. This extension highlights what we call “entrepreneurial digital thresholds”. These are critical junctures where learners transition from understanding digital technologies as tools to conceptualising them as enablers of entrepreneurial value creation.

Second, the study contributes to the literature on digital divides by demonstrating how traditional socioeconomic factors interact with educational and motivational factors to create complex digital literacy ecosystems. This nuanced understanding moves beyond ’s () multifaceted model of digital divides toward what we conceptualise as “digital literacy structuration”, which is the recursive relationship between institutional structures, individual agency, and technological affordances that shapes digital literacy development in higher education settings.

6.2. Practical Implications: Transforming Education and Policy

We offer several practical implications for HEIs, entrepreneurship educators, and policymakers. For institutions, the identified divergence in digital literacy levels among faculty members highlights the need for integrated professional development that addresses not just technical skills but also pedagogical beliefs and institutional cultures surrounding technology.

For entrepreneurship educators, the findings suggest the importance of designing experiential learning cycles that help students traverse identified digital literacy thresholds. This may involve creating scaffolded opportunities for students to progress from participatory culture to productive digital participation within entrepreneurial contexts.

For policymakers, the study underscores the need for educational policies that address usage access rather than merely physical access to technology. This may involve developing more nuanced digital literacy frameworks that recognise domain-specific competencies required for entrepreneurial success in Industry 4.0, as well as implementing funding models that support institutional capacity building for digitally enriched EE.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study provides valuable insights into digital literacy thresholds in South African EE, several limitations should be acknowledged. While the study enables in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences, it limits the generalisability of findings to broader populations. This limitation aligns with what () identifies as inherent trade-offs between depth and breadth in qualitative inquiry. Future research could employ mixed-methods approaches to combine qualitative insights with quantitative measures of digital literacy across larger samples.

The cross-sectional design captures digital literacy levels at a specific point in time but does not track developmental trajectories. This limitation aligns with what () identifies as the challenge of capturing processes rather than states through single-point data collection. Longitudinal studies would provide valuable insights into how individuals traverse identified digital literacy thresholds over time and what factors facilitate or impede this progression.

Additionally, the study focused primarily on higher education contexts and did not extensively explore industry perspectives on digital literacy requirements. This limitation reflects challenges in bridging academic and industry perspectives. Future research could incorporate employer viewpoints to further align educational approaches with industry expectations for entrepreneurial digital literacy.

8. Conclusions

This study breaks new ground in conceptualising digital literacy as a spectrum of transformative thresholds rather than binary competencies, revealing the critical intersection between digital capabilities and EE in South African higher education. By applying threshold concept theory to digital literacy development, our research identifies specific transformative junctures that distinguish passive digital consumption from active entrepreneurial creation, demonstrating that preparing students for Industry 4.0 requires addressing not just technical access but fundamental pedagogical challenges.

Therefore, this study makes three original contributions to digital literacy scholarship:

First, we introduce the concept of ‘entrepreneurial digital thresholds’—specific transformative junctures unique to entrepreneurial contexts that extend beyond general digital literacy frameworks.

Second, we develop the ‘digital literacy structuration’ framework, demonstrating how individual agency, institutional structures, and technological affordances recursively shape digital competence development in ways not captured by existing models.

Third, we provide empirical evidence challenging the digital native paradigm in the Global South context, revealing complex competency variations that demand nuanced, contextually responsive educational interventions.

These contributions are particularly significant for South African higher education as they provide actionable pathways for addressing the digital divide while preparing graduates for meaningful participation in the global digital economy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/admsci15100396/s1.

Author Contributions

F.I.M. led the conceptualisation and design, analysis, interpretation of findings and drafting of the manuscript. N.H.M. was engaged in reviewing the manuscript and approving the submission to the journal. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of the University of South Africa (UNISA) and approved by the Unisa College of Economic and Management Sciences Research Ethics Review Committee for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EE | Entrepreneurship Education |

| Industry4.0 | Directory of Open Access Journals |

| SA | South Africa |

| TPACK | Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge |

| UNISA | University of South Africa |

References

- Aviram, A., & Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2006). Towards a theory of digital literacy: Three scenarios for the next steps. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 9(1). [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A., & Wessels, S. (1997). Self-efficacy. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baumol, W. J. (1996). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetham, H., & Sharpe, R. (2019). Theory into practice: Approaches to understanding how people learn and implications for design. In Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age (pp. 243–250). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Belshaw, D. (2012). What is ‘digital literacy’? A Pragmatic investigation [Doctoral dissertation, Durham University]. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook i the cognitive domain. Longman, Green Co. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimah, A. N., Salau, A. A., & Sanni, A. M. (2023). Effect of digital literacy responsibility of telecoms on entrepreneurial ecosystem building. Fuoye Journal of Management, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 2(2), 311–312. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C., & Czerniewicz, L. (2010). Debunking the ‘digital native’: Beyond digital apartheid, towards digital democracy. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 26(5), 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangiano, G. R. (2011). Studying episodic access to personal digital activity: Activity trails prototype. University of California, San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (introducing qualitative methods series). Constr. grounded theory. SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, C. (2013). The habitus of digital scholars. Research in Learning Technology, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Czerniewicz, L., & Brown, C. (2014). The habitus and technological practices of rural students: A case study. South African Journal of Education, 34(1), 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behaviour. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2018). The sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Ertmer, P. A. (1999). Addressing first-and second-order barriers to change: Strategies for technology integration. Educational Technology Research and Development, 47(4), 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. (1984). Elements of the theory of structuration. In Practicing history: New directions in historical writing after the linguistic turn. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, R., & Lea, M. R. (2013). Literacy in the digital university. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Mendoza, J. E., Muñoz-Arteaga, J., Muñoz-Zavala, Á. E., & Santaolaya-Salgado, R. (2015). An interactive ecosystem of digital literacy services: Oriented to reduce the digital divide. International Journal of Information Technologies and Systems Approach (IJITSA), 8(2), 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, M., Kew, J., & Kew, P. (2020). Global entrepreneurship monitor. University of Cape Town. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, S. K., Ma, J., & Yang, J. (2016). Student rules: Exploring patterns of students’ computer-efficacy and engagement with digital technologies in learning. Computers & Education, 101, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan Karagul, B., Seker, M., & Aykut, C. (2021). Investigating students’ digital literacy levels during online education due to COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(21), 11878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. H. (2024). A study on the impact of digital literacy competence on entrepreneurial opportunity competence: Focusing on the moderating effect of entrepreneurial orientation. The Journal of Korean Career· Entrepreneurship & Business Association, 8(2), 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Krumsvik, R. J. (2014). Teacher educators’ digital competence. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(3), 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuteesa, K. N., Akpuokwe, C. U., & Udeh, C. A. (2024). Theoretical perspectives on digital divide and ICT access: Comparative study of rural communities in Africa and the United States. Computer Science & IT Research Journal, 5(4), 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2015). Interviews. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (Eds.). (2008). Digital literacies: Concepts, policies and practices (Vol. 30). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, G., & Klinton, M. (2019). University entrepreneurship education: A design thinking approach to learning. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 8(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. (2007). Gradations in digital inclusion: Children, young people and the digital divide. New Media & Society, 9(4), 671–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A., Furberg, A., & Gudmundsdottir, G. B. (2019). Expanding and embedding digital literacies: Transformative agency in education. Media and Communication, 7(2), 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda, M. I., & Ben Dhaou, S. (2019, April 3–5). Responding to the challenges and opportunities in the 4th Industrial revolution in developing countries. 12th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (pp. 244–253), Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Bravo, M. C. (2022). Digital literacy: A multidimensional view of digital competencies in 21st century skills frameworks [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad de Navarra]. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. H., & Land, R. (2003). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: Linkages to ways of thinking and practising within the disciplines. Oxford Brookes University. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. H., & Land, R. (2005). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (2), Epistemological considerations and a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Higher Education, 49, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S., Wright, M., & Feldman, M. (2019). The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Research Policy, 48(8), 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, H. M., & Greene, P. G. (2011). Entrepreneurship education: Known worlds and new frontiers. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers & Education, 59(3), 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedemi, T., & Mogano, S. (2018). The digitally disadvantaged: Access to digital communication technologies among first year students at a rural South African University. Africa Education Review, 15(1), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papert, S. (1980). Children, computers, and powerful ideas (Vol. 10). Harvester. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattray, J. (2016). Affective dimensions of liminality. In Threshold concepts in practice (pp. 67–76). Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, T., & Hernandez, K. (2019). Digital access is not binary: The 5′A’s of technology access in the Philippines. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 85(4), e12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. (2003). Longitudinal qualitative research: Analysing change through time. Rowman Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J., & Omasta, M. (2016). Qualitative research: Analysing life. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, K. (2024). The Fourth Industrial Revolution: What it means, how to respond. In Handbook of research on strategic leadership in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (pp. 29–34). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, J. R. (1995). The construction of social reality. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiwu, D., Akena, F. A., & Rugambwa, N. O. (2022). Decolonising the African University Pedagogy Through Integrating African Indigenous Knowledge and Information Systems. In Handbook of research on transformative and innovative pedagogies in education (pp. 171–188). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Shabdin, N. I., & Yaacob, S. (2023). Digitalization components at strategizing digital transformation in organizations. Open International Journal of Informatics, 11(2), 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, W. W., & Boechler, P. M. (2014). Incidental learning in 3D virtual environments: Relationships to learning style, digital literacy and information display. International Journal of Virtual and Personal Learning Environments (IJVPLE), 5(4), 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, J. A., & Meyer, J. H. (2019). Embedding affect in the threshold concepts framework. Threshold Concepts on the Edge, 73, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Van Deursen, A. J., & Van Dijk, J. A. (2015). Toward a multifaceted model of internet access for understanding digital divides: An empirical investigation. The Information Society, 31(5), 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, T. A. (2005). Discourse analysis as ideology analysis. In Language & peace (pp. 41–58). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen, M. (2023). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychologicalprocesses. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, D. S., & Le Cornu, A. (2011). Visitors and Residents: A new typology for online engagement. First Monday, 16(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).