Abstract

Small and medium-sized enterprises face significant challenges in effectively implementing design thinking due to limited resources, leadership skepticism, and a paucity of suitable frameworks. This study addresses these challenges by developing and validating a web-based Design Thinking and Innovation Strategy Toolbox tailored to SME needs. The Toolbox is designed to align with the ISO 56001:2024 Innovation Management Systems standard and was developed through systematic literature reviews and expert interviews, shaping practical modules based on previously identified barriers and success factors. A multi-round Delphi study with 14 experienced consultants refined the Toolbox, focusing on usability, ISO compliance, and practical relevance. The results indicate strong consensus among experts regarding its clarity, adaptability, and alignment with SME constraints, while also highlighting areas for improvement such as visual design and continuous feedback mechanisms. Preliminary validation suggests that the Toolbox can support SMEs in improving sustainable innovation, strategic alignment, and capability development. By addressing contextual constraints, this research contributes to the field of design-led innovation in SMEs by offering a practical, ISO-compliant tool that connects theory and practice in resource-limited environments.

1. Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are important contributors to economic growth, innovation, and employment in Europe, accounting for 99% of all businesses and approximately 65% of employment (European Commission, 2023). Despite increasing attention on design-led innovation, SMEs continue to face significant challenges when integrating structured innovation frameworks such as Design Thinking (DT) into their strategic processes. Common barriers include limited financial and human resources, fragmented innovation knowledge, and organizational cultures that do not encourage experimentation or creativity (Elsbach & Stigliani, 2018; Ibarra et al., 2020).

DT has been recognized for its ability to promote empathy-driven problem-solving, iterative experimentation, and customer-centered innovation (Brown, 2008; Carlgren et al., 2016). However, existing frameworks and toolkits are mostly designed for large corporations with dedicated innovation departments and extensive support systems (Amalia & von Korflesch, 2023; Schweitzer et al., 2016). Recent studies also emphasize that SMEs require leaner, more adaptable, and context-specific instruments that reflect their operational realities and strategic limitations (Demir et al., 2023; Jaskyte & Liedtka, 2022; Kihlander et al., 2024). Contributions by Olivares Ugarte and Bengtsson (2024) and Tuffuor et al. (2025) highlight both the critical success factors for applying DT in industrial SMEs and the role of design management capabilities in strengthening SME performance, which further reinforces the need for frameworks that combine theoretical robustness with practical adaptability.

While the literature highlights the benefits of DT for SMEs, there is still a lack of validated frameworks that combine design-led innovation with structured, standards-based approaches. No prior study has developed a DT toolbox explicitly aligned with the ISO 56001:2024 Innovation Management Systems standard. This represents a key gap, since the ability to adapt abstract international standards into practical, accessible tools is essential for SMEs to strengthen their innovation capabilities under resource constraints.

This study addresses this gap by developing a web-based DT Toolbox specifically developed to answer SME needs. The toolbox is aligned with the ISO 56001:2024 Innovation Management Systems standard (Merrill, 2024), enabling compatibility with global innovation benchmarks while remaining accessible to resource-constrained organizations. A multi-round Delphi methodology involving experienced DT consultants and SME innovation advisors was conducted to refine the toolbox, focusing on practical relevance and theoretical robustness.

The main research question guiding this study is: How can DT principles be effectively applied within SMEs through a flexible toolbox that accommodates resource limitations while supporting systematic innovation capability development?

This research contributes to the field by offering a practical, ISO-compliant framework for operationalizing design thinking in SMEs to enhance sustainable innovation and strategic alignment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the existing literature on DT in SMEs, innovation management, and the ISO 56001:2024 standard. Section 3 describes the methodology, focusing on the Delphi study used to develop and validate the toolbox. Section 4 presents the main results, including the structure and refinement of the DT Toolbox. Finally, Section 5 discusses the conclusions, limitations, and potential directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. DT in SMEs

DT is a widely recognized human-centred and iterative problem-solving approach that promotes innovation through empathy, experimentation, and collaboration with stakeholders (Brown, 2008; Liedtka, 2015). It typically involves five phases: empathizing to understand user needs, defining the problem, generating ideas, developing prototypes, and testing solutions with users. While large organizations have incorporated DT through innovation labs, internal training, and cross-functional teams (Carlgren et al., 2016), SMEs have received less attention and lack frameworks adapted to their specific conditions.

SMEs often face challenges in adopting DT due to limited financial resources, time constraints, informal organizational structures, and the absence of internal innovation champions (Demir et al., 2023; Ibarra et al., 2020). The open-ended and experimental nature of DT may also clash with the efficiency-driven routines common in smaller firms (Schweitzer et al., 2016). These barriers are not only operational but reflect deeper organizational tensions between the exploratory nature of design-led innovation and the focus on immediate performance required in resource-constrained environments. Research has also shown that developing a DT mindset is essential to overcoming such cultural and organizational barriers, particularly in SMEs operating in creative industries (Suhaimi et al., 2024).

However, research indicates that, when adapted to SME contexts, DT can improve strategic alignment, product and service differentiation, and user-driven innovation (Jaskyte & Liedtka, 2022). Key adaptation factors include simplifying methods, integrating them into existing routines, and demonstrating value through early, tangible results (Fischer et al., 2020). Successful implementation depends on adjusting Design Thinking to fit operational realities without compromising its core principles.

According to the extant literature, the implementation of DT in SMEs requires a pragmatic, user-friendly, and adaptable approach that aligns with the operational logic and facilitates incremental capability development (Elsbach & Stigliani, 2018). However, existing toolkits and frameworks often prioritize abstract methods over context-sensitive applicability.

2.2. Management of Innovation and ISO 56001:2024

Innovation management has evolved from isolated initiatives to a structured discipline, increasingly supported by international standards. The publication of ISO 56001:2024, the first international certifiable standard for innovation management systems, marks an important step in the formalization of innovation practices across organizations (Merrill, 2024). ISO 56001 builds on the ISO 56002:2019 guidelines, offering a process-oriented framework structured around leadership, strategy, support, operations, and performance evaluation (ISO, 2024).

For SMEs, adopting standards such as ISO 56001 offers both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, the standard can help formalize innovation activities, improve competitiveness, and meet the requirements of procurement processes and funding applications (Gault, 2018). It provides a shared language and structure to manage innovation, which may increase SMEs’ ability to demonstrate their capabilities to investors, partners, and clients (Kihlander et al., 2024). On the other hand, SMEs often lack resources, internal expertise, and methodological support needed to implement complex innovation management systems (Carneiro et al., 2021). Translating the abstract requirements of the standard into practical routines can be particularly difficult in smaller firms with limited capacity (Iraldo et al., 2010).

This study uses ISO 56001 as a normative reference for the DT toolbox. The objective is not to impose rigid processes but to provide SMEs with a modular, user-friendly instrument that supports gradual alignment with international innovation practices. By breaking down the standard’s requirements into practical and actionable components, the Toolbox aims to make structured innovation management accessible to resource-constrained organizations. Its integration of ISO-aligned criteria supports the development of scalable and certifiable innovation capabilities, helping SMEs strengthen their position in an increasingly standards-driven market by breaking down the standards’ requirements into practical and actionable components. The Toolbox aims to make structured innovation management accessible to resource-constrained organizations. Its integration of ISO-aligned criteria supports the development of scalable and certifiable innovation capabilities, helping SMEs improve their competitive position in standards-driven markets.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Delphi Method

The Delphi method is a widely used research technique for gathering expert knowledge through iterative rounds of structured feedback. It is particularly useful when consensus needs to be built around complex or emerging topics (Linstone & Turoff, 2002). Originally developed for forecasting, the Delphi method has been applied across various fields, including innovation management, policy development, and system design (Nowack et al., 2011).

A major strength of the Delphi method is its ability to generate reliable knowledge in situations characterized by uncertainty, limited empirical data, or divergent expert opinions (Skulmoski et al., 2007). Anonymity between participants helps avoid biases that can arise in face-to-face group discussions, e.g., influence of dominant personalities or hierarchical differences (Rowe & Wright, 2011). The iterative structure allows experts to reconsider their opinions based on aggregated feedback, supporting a more informed and balanced consensus.

In this study, the Delphi method is used to refine and validate the DT toolbox (Demir, 2025). The process involved three rounds of data collection, each combining quantitative assessments with qualitative feedback. The three-round structure follows established methodological recommendations for ensuring exploration and convergence (Nowack et al., 2011).

Quantitative evaluations used 5-point Likert scales to assess elements such as the Toolbox’s structure, usability, SME suitability, and ISO compatibility. Open-ended questions gathered suggestions, contextual insights, and implementation feedback, enriching the understanding of expert views. After each round, anonymized summaries of the results were shared with participants, allowing them to reflect on the collective feedback before responding in the next round (Schifano & Niederberger, 2025).

To ensure robustness, the number of items was progressively reduced across rounds, focusing only on those dimensions that did not yet meet the predefined consensus threshold (75% of respondents selecting 4 or 5 on a 5-point Likert scale). No additional statistical weighting of variables was applied; instead, prioritization was achieved through this consensus threshold, which is widely adopted in Delphi research for ensuring comparability and methodological transparency.

3.2. Expert Selection

Experts were selected based on three criteria: (1) professional experience in DT and innovation consulting; (2) familiarity with SME innovation contexts; and (3) involvement in applied innovation practice or standardization processes. This ensured that participants had both theoretical understanding and practical experience relevant to the study’s objectives.

A purposive sampling strategy was used to gather a diverse panel of 14 experts from Germany (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Expert Panel.

The number of experts falls within the recommended range for Delphi studies, which typically suggests that at least 8 experts are needed to balance diversity with manageability (van Zollingen & Klasssen, 2003; Mitchell, 1991). Informed consent was obtained from the participants before the study was initiated.

All experts were based in Germany and had professional experience in the disciplines of innovation management, design thinking, and SME consulting. The panel composition ensured diversity in terms of occupational role, professional background, and industry exposure, contributing to the robustness of the study’s insights and the theoretical transferability of its findings. Despite the shared national context, the experts brought a variety of perspectives due to their different roles.

All experts were experienced in applying DT methods in the context of SMEs. Their profiles covered roles such as transformation consultants, SME innovation managers, and design thinking coaches. All had facilitated or supported innovation initiatives in SME settings, either through internal initiatives or external consulting engagements. This approach ensured a practice-based and methodologically sound foundation for evaluating and refining the digital innovation toolkit.

Furthermore, several experts had contributed to the development of innovation tools, training materials, and academic publications. The average professional experience in the field exceeded ten years, which ensured a critical perspective throughout the iterative feedback process.

3.3. Delphi Rounds and Instruments

The Delphi study was conducted in three iterative rounds between March and May 2025. Each round consisted of two parts: a quantitative assessment and qualitative feedback.

In the quantitative assessment, experts rated statements about the Toolbox’s structure, usability, relevance to SMEs, and compatibility with ISO 56001 using a 5-point Likert scale. Items reaching 75% agreement (scores of 4 or 5) were considered validated and removed from subsequent rounds to avoid redundancy. This provided measurable indicators of agreement and helped identify areas of convergence and divergence.

In the qualitative feedback, open-ended questions collected suggestions, contextual observations, and improvement ideas. These responses helped increase the comprehension on how the toolbox could be adapted to SME environments.

The survey was administered using the SurveyMonkey platform, which allowed anonymous participation and secure data collection. Between rounds, anonymized summaries of results and synthesized feedback were shared with participants. This feedback loop enabled reflection and helped build consensus across rounds (Schifano & Niederberger, 2025).

The first round focused on the original version of the DT Toolbox, asking feedback on its overall structure, content, and alignment with DT principles and SME operational realities. The second round concentrated on the modified version of the DT Toolbox developed based on feedback from the first round. The final round validated the final version of the DT Toolbox in terms of completeness, coherence, and practical applicability across different SME contexts.

The method enabled a structured translation of expert expectations into concrete features of the design thinking toolbox, aligned with ISO 56002’s iterative improvement logic.

3.4. Data Analysis and Quality Criteria

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Items that received agreement ratings (scores of 4 or 5) from at least 75% of participants were considered validated. Items falling below this threshold were reviewed and, if necessary, revised or removed.

Qualitative responses were analyzed using thematic analysis. A coding framework was developed inductively, and codes were grouped into broader categories based on similarity of content. These categories were then consolidated into thematic clusters representing recurrent areas of feedback (e.g., outcome orientation, application guidance, tool prioritization). NVivo software, version 15, was used to ensure consistency in coding and traceability of the analysis (Nowell et al., 2017). This systematic approach allows for replication and provides transparency in how clusters were derived from raw expert input.

The Delphi process followed established quality criteria, including transparency (detailed documentation of the research process), anonymity, iteration with controlled feedback, and statistical and thematic analysis of group responses (Skulmoski et al., 2007). These principles helped ensure that the resulting toolbox reflects a balanced, evidence-informed view of how DT can be adapted to SME contexts.

4. Results

4.1. Delphi Round 1: Initial Feedback

The initial round of the Delphi study aimed to evaluate the relevance, structure, and practical usability of the design thinking and innovation toolkit for SMEs. All experts participated in the initial assessment.

Quantitative data revealed high levels of agreement across several key areas. The clarity of objectives, the usability of structure, and the relevance of the toolkit for SME innovation contexts received strong endorsement. Items that achieved a minimum of 75% agreement on Likert scores of 4 or 5 were considered as having reached preliminary consensus; others were revised for the next Delphi round. To facilitate comparison and improve clarity, a sample of the results obtained in this initial round is presented in Table 2. To illustrate the results more clearly, additional tables have been included in the Supplementary Materials, showing consensus levels across all items for all rounds of the Delphi study.

Table 2.

Delphi Round 1—Quantitative Evaluation of Toolbox Dimensions.

Thematic analysis of the open-ended responses yielded insights and suggestions that were grouped into categories such as practical applicability, strategic integration, and usability enhancements. Experts emphasized the importance of providing more guidance for non-expert users within SMEs, such as facilitator tips and real-world application examples. There was also a clear call for stronger alignment with business impact, including suggestions for KPI reflection templates and ROI-oriented decision tools. These qualitative results were then clustered into key feedback themes, which directly informed the refinement of the toolbox prior to round two.

In response to these inputs, several targeted improvements were implemented. New downloadable templates, including the “Facilitator Tips” and “Interview Quick Guide” were introduced in the Empathize phase, and the “Impact Reflection Sheet” was developed to guide measurement of innovation outcomes. In addition, visual and structural changes were implemented to improve navigability and reduce cognitive load. These refinements established the foundation for a second round of evaluation with a more focused approach.

4.2. Delphi Round 2: Refinements and Adjustments

The second round of the Delphi study focused on validation of the refinements implemented after the initial round and the acquisition of additional insights for enhancement. The same panel reviewed the updated digital toolkit, including the newly added features and structural adjustments based on their prior feedback.

Quantitatively, the refinements received a high level of endorsement. Core structural elements such as navigation logic, phase clarity, and visual layout exceeded the 80% consensus threshold.

In particular, the integration of SME-relevant templates and the simplification of prototyping tools received high ratings. Experts also acknowledged the effectiveness of the “Impact Reflection Sheet” and the introduction of lightweight guidance tools such as the “Feasibility Checklist” and “Paper Prototype Guide”.

Open-ended feedback was again clustered thematically, leading to identification of twelve recurrent areas that necessitated enhancement. These included stronger alignment between tools and expected innovation outcomes, more clearly delineated onboarding pathways for novice users, enhanced visual grouping of tools, and support for business-model thinking. Several experts emphasized the need for a “lightweight track”, defined as a set of expeditious tools for SMEs with limited time and resources. Others recommended providing a simplified, ROI-oriented decision aid for resource-constrained implementation scenarios.

Many suggestions received in Round 2 reinforced the direction of the implemented changes and provided further details. As a result, a final wave of refinements was prepared for validation in Round 3, including modular decision paths, updated download templates, and additional instructional texts for non-expert users. The feedback loop demonstrated increasing convergence across rounds, highlighting the iterative quality of the toolkit’s co-development process.

4.3. Delphi Round 3: Final Validation

The third and final round of the Delphi study was designed to validate the refined version of the Design Thinking Toolbox. This was achieved by systematically consolidating expert feedback from the preceding iterations. The final phase of the study was implemented as a structured Likert-scale assessment, in which all experts participated, once again. The consistency of the expert panel ensured methodological consistency and reliability in the final evaluation.

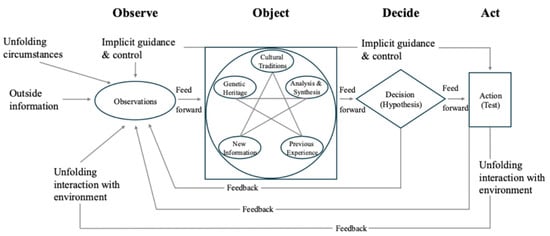

The survey instrument was comprised of four thematic dimensions: relevance and objectives, usability and navigation, alignment with the OODA model (Observe–Orient–Decide–Act), and sensitivity to SME-specific constraints (Begley & Boyd, 1987), as illustrated in Figure 1. Each thematic block contained several items, which were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Figure 1.

The OODA loop (Observe–Orient–Decide–Act), illustrating iterative decision logic used as a reference framework in the toolbox evaluation. Adapted from Begley and Boyd (1987).

The analysis of the 20 items indicated a high level of convergence. The mean agreement across all responses was 4.38. Notably, no respondent selected a score below 3 for any item. The highest level of endorsement was recorded for the statement regarding the relevance of the toolbox for SME innovation practice, where 79 percent of the panel selected “strongly agree”. Other items in this category also exceeded the predefined consensus threshold, which reflects a shared perception that the toolbox offers clearly articulated objectives and is well aligned with the challenges and needs of SMEs (Demir et al., 2023).

Concerning usability and structural logic, the feedback indicated that the toolbox offers intuitive navigation and clearly defined module titles. While the overall ratings in this dimension were consistently positive, the item related to visual design received more reserved evaluations, with a mean score of 3.93 and a notable number of neutral responses. This finding indicates the presence of possibility for enhancement in the visual and aesthetic presentation, particularly in improving accessibility for users with limited experience in design methodologies (Schweitzer et al., 2016).

In relation to the integration of the OODA model, the toolbox was considered especially supportive in the “Observe” and “Decide” phases, as indicated by mean scores of 4.64 and 4.14 respectively. These findings correspond to features such as structured templates and reflective prompts. However, the item measuring support for continuous feedback loops achieved only moderate consensus, with a mean score of 4.00 and six neutral responses. These results underscore the necessity for improved integration of iterative learning mechanisms and post-decision reflection prompts, which are essential for operationalizing cyclical innovation models (Carlgren et al., 2016; Elsbach & Stigliani, 2018).

The dimension addressing SME-specific constraints demonstrated the highest overall agreement. Experts have confirmed that the toolbox adequately reflects common conditions within SMEs, such as time and budget limitations, flat organizational hierarchies, and a lack of internal innovation expertise. The mean scores across five of the seven items in this category exceeded 4.60. The statement regarding the toolbox’s capacity to compensate for the absence of internal innovation experts received a slightly lower mean score of 3.93. This finding indicates that, although the toolbox enables self-guided utilization, certain SMEs might still require supplementary onboarding materials or structured formats for guidance (Fischer et al., 2020; Ibarra et al., 2020).

In summary, the third Delphi round yielded a high level of consensus across all evaluated dimensions. The consensus among all participants was that all items met the established criteria, and no dissenting opinions were expressed. The results confirm the validity and perceived utility of the toolbox while also highlighting areas for targeted refinement. These include improvements in visual communication, mechanisms for iterative learning, and enhanced support for non-expert users.

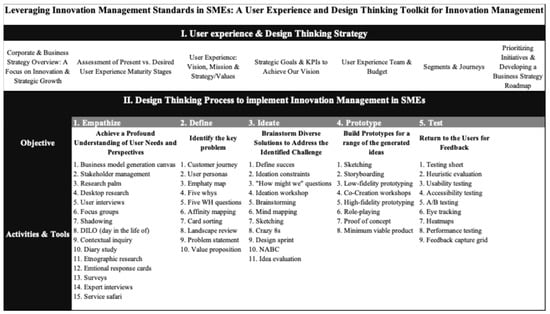

Based on the feedback from all three Delphi rounds, the final toolbox version was confirmed as both relevant for and implementable in SMEs. Figure 2 provides a structured overview of the toolbox architecture, including its five core phases, example tools, and additional features that were integrated in response to expert feedback.

Figure 2.

Structure of the DT Toolbox for SMEs with Delphi-driven enhancements (own elaboration).

4.4. Summary of Key Changes Across Rounds

The iterative nature of the Delphi process enabled the progressive refinement of the toolbox based on expert feedback. Table 3 offers a comprehensive overview of the most frequently identified improvement areas raised across Rounds 1 and 2, grouped into thematic clusters. Each cluster highlights an area where specific concerns or improvement suggestions were expressed, such as tool prioritization, reflection guidance, or integration into the daily work context. The table also indicates how these issues were addressed in the toolbox and which topics remained partially unresolved or require further development.

Table 3.

Delphi Study—Cluster Analysis of Open Feedback (Round 1 & 2).

This feedback-driven evolution resulted in the introduction of new tools, e.g., the KPI sheet and the ROI canvas. Structural changes were implemented, including enhanced menu logic and feedback buttons. Usability enhancements were also made, such as clearer examples, visual filtering, and facilitator guidance. The frequency of mentions further reflects the perceived urgency or relevance of the issues from an expert perspective. Overall, the Delphi feedback functioned as a formative mechanism to develop a toolbox that aligns more closely with SME-specific needs and implementation realities.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Results

The Delphi results revealed consensus on the conditions shaping SME innovation, particularly the need for simplification, modularity, and strategic alignment. The final toolbox version was confirmed to meet these expectations through intuitive structure, phased navigation, and adaptability across varying resource levels. As one expert noted: “The strength of the toolbox lies in its pragmatic orientation. It reflects how SMEs really work, not how we wish they would”.

The toolbox’s fundamental logic mirrors pivotal aspects of the ISO 56002 innovation management standard. These aspects include opportunity identification, risk-based thinking, and knowledge-driven iteration (ISO, 2024). The integration of phases such as “Observe” and “Decide” with both the OODA framework and ISO process requirements establishes a structured framework that is both accessible and normatively sound. The systematisation of tools across the innovation cycle, including templates for exploration, evaluation and reflection, echoes ISO’s emphasis on a structured, value-oriented approach to innovation capability.

Despite the expressed desire among several experts for clearer mechanisms of continuous learning, the final version of the toolbox already includes feedback buttons embedded within each phase. These elements, although not explicitly acknowledged by all respondents, align with ISO 56002’s principle of feedback-driven improvement and reflection cycles. The integration of these elements is designed to not only facilitate the execution of innovation but also to provide users with opportunities for reflection and learning during the process.

The consensus across expert roles and sectors indicates that the toolbox effectively addresses a persistent methodological gap. It provides a structured and flexible tool that SMEs can apply independently without requiring substantial training or facilitation.

Nevertheless, the findings also confirm that the toolbox cannot be considered a one-size-fits-all solution. Industry-specific conditions, organizational cultures, and firm characteristics such as being family-owned or operating in service-dominated sectors may require additional adaptations. Similarly, SMEs with low levels of digital maturity might encounter implementation challenges that are less pronounced in more technologically advanced organizations. These contextual differences highlight the importance of adapting the toolbox to specific circumstances and testing it across a wider range of SME settings.

5.2. Comparison with Literature

The study’s findings reinforce and extend the results of previous investigations into the innovation needs of SMEs and the practical limitations of design thinking. Demir et al. (2023) highlighted that SMEs require low-threshold, modular tools that are usable without expert facilitation. The present toolbox directly addresses this requirement by providing self-guided modules, structured templates, and clearly formulated reflection prompts. One expert described the toolbox as a bridge between design thinking theory and practical SME application, emphasizing that its strength lies in self-guided usability without reliance on external consultants.

The findings also align with those of Ibarra et al. (2020), who describe the difficulty faced by SMEs in translating abstract innovation concepts into action. The toolbox addresses this discrepancy through a project-phase logic, guiding questions, and compact canvases that facilitate decision-making and orientation. These features are indicative of the objective of ISO 56002 to facilitate innovation in a manageable and value-oriented manner, especially in contexts characterized by limited innovation infrastructure.

The emphasis on the OODA loop as an organizing logic also supports a structured yet flexible approach. Carlgren et al. (2016) questioned the operational depth of many design thinking implementations. In contrast, the toolbox in this study translates abstract process models into tangible, phase-specific instruments. While this advances the applicability of design thinking, it also emphasizes the challenges identified by Elsbach and Stigliani (2018), particularly the need to consider team dynamics, organizational context and learning culture. Recent experimental evidence from design sprint innovation contests confirms the value of short, iterative interventions in SME contexts, further supporting the practical relevance of lightweight DT tools (Azzolini et al., 2025). These aspects are only partially addressed by the current toolkit, suggesting the need for complementary interventions.

5.3. Implications for Practice

The toolbox is useful to support innovation in SME environments, typically constrained by time, budget, and lack of specialist knowledge. The modular design and explicit phase logic allow in-house teams to explore, reflect, and prototype without reliance on external facilitation. According to numerous experts, this self-guided usability is a significant advantage, especially for small firms with limited access to consultants or formal training programs.

From a managerial perspective, the toolbox supports SME leaders in systematically approaching innovation while respecting organizational constraints. It provides practical templates for decision-making, outcome reflection, and incremental capability development, which are very important in environments with limited expertise or budgets. The explicit alignment with ISO 56002 facilitates the integration into existing quality management and innovation development systems. Features such as feedback prompts and framing templates support reflection and learning cycles, which are essential in ISO-guided improvement contexts.

For policymakers and ecosystem actors, it represents a ready-to-use resource that can be embedded in regional development programs, incubators, and capacity-building initiatives aimed at democratizing access to innovation practices. The combination of visual clarity, step-by-step structure and accessible language lowers barriers to entry for companies that have not yet engaged with design thinking or innovation management frameworks.

Consequently, the toolbox contributes to practical innovation work within SMEs, and also to broader efforts aimed at democratizing access to structured innovation tools across heterogeneous business contexts.

5.4. Limitations

While the Delphi study provided valuable expert validation, several limitations must be acknowledged. The panel comprised 14 experts, which, although sufficient for methodological rigor, limits generalizability. Most participants were based in German-speaking regions, which may constrain cultural transferability. The toolbox should not be interpreted as universally applicable across all SME contexts. Differences in industry dynamics, governance models (e.g., family firms), and levels of digital maturity may influence adoption and effectiveness. Future research should explicitly investigate these contingencies to better understand where and how the toolbox requires adaptation. Emerging research also suggests that the integration of DT with technologies such as business intelligence and AI may open additional pathways for SME innovation, which should be considered in future adaptations of the toolbox (Kaaria, 2025).

Additionally, the validation process was based on expert judgement rather than direct application. The toolbox has not yet been tested by SME teams in live settings. As a result, insights into user behavior, learning curves, and team dynamics remain preliminary. Future field-testing is needed to confirm whether the toolbox performs as intended under practical conditions.

Another limitation is the potential influence of expert familiarity with innovation methods. Since most panel members had prior exposure to design thinking, their evaluations may have been shaped by an implicit understanding of key concepts and structures. The perspectives of less experienced users were not systematically included, which leaves open the question of how intuitive the toolbox is for complete novices.

Finally, although feedback mechanisms were built into the toolbox, their perceived visibility varied among experts. Some respondents may not have recognized the feedback options embedded in each phase, suggesting that further visual and instructional reinforcement may be beneficial. These limitations indicate important directions for empirical validation, user onboarding, and contextual adaptation in subsequent iterations.

6. Conclusions

This study designed, developed and validated a web-based design thinking toolbox adapted to the needs and constraints of SMEs. Through a three-round Delphi study with 14 experts, the toolbox was iteratively refined to ensure usability, ISO 56001:2024 compliance, and practical relevance. The results demonstrate strong expert consensus on the importance of modularity, intuitive structure, SME-specific adaptation, and alignment with established innovation frameworks such as ISO 56002 and the OODA loop. Across all rounds, experts consistently emphasised the value of a self-guided, low-threshold approach to supporting innovation without external facilitation.

From a theoretical perspective, it advances the literature on design-led innovation by bridging the gap between abstract DT frameworks and the operational requirements of SMEs. It shows how international standards such as ISO 56001 can be translated into modular, context-sensitive tools, thus contributing to discussions on how SMEs build structured innovation capabilities under resource constraints.

From a practical perspective, the toolbox provides SME managers and consultants with a flexible, self-guided instrument that supports systematic innovation without requiring extensive facilitation or resources. It can also be applied in policy and ecosystem initiatives, where it offers a practical solution for promoting design-led innovation at scale.

Nonetheless, the Delphi panel, while diverse, was concentrated in German-speaking regions and based on expert perspectives rather than direct SME applications. Furthermore, the Toolbox is not a one-size-fits-all solution: industry dynamics, governance models such as family businesses, and levels of digital maturity may require specific adaptations.

Future research could focus on empirical testing of the toolbox by applying and refining it in SME settings, across different industries and organizational cultures, to assess usability, learning processes, and innovation outcomes. Such studies could help understand more about user experience, learning effects, and innovation outcomes. Particular attention should be paid to onboarding processes, tool selection behavior, and the role of facilitation versus autonomy. Facilitating mechanisms could involve integration with coaching formats, blended learning modules, or digital innovation platforms supported by regional development agencies.

Longitudinal studies could further analyze how the toolbox contributes to the development of innovation capabilities over time, as a way to increase the understanding of how DT and ISO-based models may be used as learning systems in practice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/admsci15100384/s1, Table S1. Delphi Round 1—Quantitative Evaluation of Toolbox Dimensions; Table S2. Delphi Round 2—Quantitative Evaluation of Toolbox Dimension; Table S3. Delphi Round 3—Quantitative Evaluation of Toolbox Dimension.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.D., I.S.-A., and D.F.P.; methodology, F.D.; validation, I.S.-A., and D.F.P.; formal analysis, F.D.; investigation, F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.D.; writing—review and editing, I.S.-A., and D.F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NECE-UBI, Research Centre for Business Sciences, funded by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, IP, project UIDB/04630/2020 and by CIMAD—Research Center on Marketing and Data Analysis (I.S-A). It was also funded by the Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policy Research Unit (GOVCOPP), funded by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, IP, project UIDB/04058/2020 (DP).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ESOMAR Code, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Director of CIMAD (protocol code 01/2025 and date of approval 15 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amalia, R. T., & von Korflesch, H. F. O. (2023). Entrepreneurial design thinking© in higher education: Conceptualizing cross-cultural adaptation of the western teaching methodology to the eastern perspective. In J. H. Block, J. Halberstadt, N. Högsdal, A. Kuckertz, & H. Neergaard (Eds.), Progress in entrepreneurship education and training: New methods, tools, and lessons learned from practice (pp. 137–154). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Azzolini, D., Codagnone, C., & Lupianez-Villanueva, F. (2025). Experimental evidence from design sprint innovation contests. Technovation, 138, 103504. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, T. M., & Boyd, D. P. (1987). A comparison of entrepreneurs and managers of small business firms. Journal of Management, 13(1), 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), 84–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carlgren, L., Rauth, I., & Elmquist, M. (2016). Framing design thinking: The concept in idea and enactment. Creativity and Innovation Management, 25(1), 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, V., Rocha, A., Rangel, B., & Alves, J. (2021). Design management and the SME product development process: A bibliometric analysis and review. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 7, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, F. (2025). Innovate by desgin: Your innovation Canvas for SMEs. Available online: https://fatmademir2.wixsite.com/design-thinking (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Demir, F., Saur-Amaral, I., & Polónia, D. F. (2023). Design thinking and innovation in SMEs: A systematic literature review in terms of barriers and best practices. In G. Goldschmidt, & E. Tazari (Eds.), Expanding the frontiers of design: A blessing or a curse? (pp. 1–21) Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Elsbach, K. D., & Stigliani, I. (2018). Design thinking and organizational culture: A review and framework for future research. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2274–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2023). Annual report on European SMEs 2022/2023. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-08/Annual%20Report%20on%20European%20SMEs%202023_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Fischer, S., Lattemann, C., Redlich, B., & Guerrero, R. (2020). Implementation of design thinking to improve organizational agility in an SME. Die Unternehmung, 74(2), 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gault, F. (2018). Defining and measuring innovation in all sectors of the economy. Research Policy, 47(3), 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, D., Bigdeli, A. Z., Igartua, J. I., & Ganzarain, J. (2020). Business model innovation in established SMEs: A configurational approach. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(3), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraldo, F., Testa, F., & Frey, M. (2010). Environmental management system and SMEs: EU experience, barriers and perspectives. In S. Sarkar (Ed.), Environmental management (pp. 1–34). Sciyo. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. (2024). Innovation management system—Requirements and guidance for use (ISO 56001:2024). ISO. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/80958.html (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Jaskyte, K., & Liedtka, J. (2022). Design thinking for innovation: Practices and intermediate outcomes. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 32(4), 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaaria, A. G. (2025). Empowering kenyan SMEs: Leveraging business intelligence, design thinking, and AI for sustainable innovation: A narrative review. East African Journal of Business and Economics, 10(1), 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihlander, I., Rains, J., & Magnusson, M. (2024, June 17–19). Systematic implementation of an innovation strategy using ISO 56002. R&D Management Conference, Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Liedtka, J. (2015). Perspective: Linking design thinking with innovation outcomes through cognitive bias reduction. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(6), 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H. A., & Turoff, M. (2002). The Delphi method: Techniques and applications. Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, P. (2024). Innovation certification: ISO 56001: 2024 arrives this month. Here’s a breakdown of key clauses. Quality Progress, 57(9), 46.49. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, V. W. (1991). The delphi technique: An exposition and application. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 3(4), 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowack, M., Endrikat, J., & Guenther, E. (2011). Review of Delphi-based scenario studies: Quality and design considerations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 78(9), 1603–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares Ugarte, J. E., & Bengtsson, L. (2024). Central characteristics and critical success factors of design thinking for product development in industrial SMEs—A bibliometric analysis. Insights into Regional Development, 4(4), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G., & Wright, G. (2011). The Delphi technique: Past, present, and future prospects—Introduction to the special issue. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 78(9), 1487–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifano, J., & Niederberger, M. (2025). How Delphi studies in the health sciences find consensus: A scoping review. Systematic Reviews, 14(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, J., Groeger, L., & Sobel, L. (2016). The design thinking mindset: An assessment of what we know and what we see in practice. Journal of Design, Business & Society, 2(1), 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulmoski, G., Hartman, F., & Krahn, J. (2007). The Delphi method for graduate research. Journal of Information Technology Education, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhaimi, S. N., Sulaiman, N., Hussain, H., & Yahya, M. (2024). Design thinking mindset: A user-centred approach toward innovation in the Welsh creative industries. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 12(4), 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuffuor, G. O., Owusu, R. A., Boakye, K. O., & Acquah, M. (2025). Design management capabilities and performance of small and medium-scale enterprises. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 14, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zollingen, S. J., & Klasssen, C. A. (2003). Selection processes in a Delphi study about key qualifications in Senior Secondary Vocational Education. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 70(4), 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).