Abstract

In complex societal contexts, resilience seems the only way to survive and prosper. This is even truer when considering the present COVID-19 pandemic and its detrimental effects on global health systems and on every aspect of life. The impact was so deep that the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global emergency on 30 January 2020. Accordingly, governments declared border closures, travel restrictions, and quarantines in the world’s largest economies, also giving rise to socio-economic recessions. There is wide literature on the pandemic’s impacts on people’s minds and societies, yet still few studies have investigated this topic holistically, examining how language shapes both human and social sides of COVID-19’s impacts. To fill this gap, this work discusses the need for new metaphorical clusters—bricolage, vicariance, and exaptation—as social sense makers to reframe a positive socially resilient response after COVID-19.

1. Introduction

In a complex context as the one in which present societies and organizations act, resilience is the only way to survive and prosper (Fisher 1984; Lederach 1996; Hopkinson and Hogarth-Scott 2001; Harari 2018). This evidence is clearer moving the attention toward the present COVID-19 pandemic. Labeled as black swan (Taleb 2007; Murphy et al. 2020; Keenan 2020), the COVID-19 pandemic had detrimental effects on global health systems, with widespread effects on every aspect of life. The impact was so profound that the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global emergency on 30 January 2020. In an attempt to flatten the curve, governments declared border closures, travel restrictions, and quarantines in countries that constitute the world’s largest economies, activating wide economic recessions (Sohrabi et al. 2020; Nicola et al. 2020). There is wide literature on the pandemic’s impact on the texture of people’s minds, organizations, and societies (Lupton 2020; Di Gennaro et al. 2020; Atalan 2020), yet still few studies have investigated this topic holistically, examining how language shapes both human and social sides of this impact, influencing social resilience.

Indeed, COVID-19 has been everywhere treated with a warlike language. According to Sontag (1978), illnesses are discussed not through language of management or treatment but through attack. Therefore, it is easy to fall into the trap of representing a health emergency as a war (and not as a complex sociocultural problem), where sick people become inevitable, dehumanized losses. Resistance metaphors are not any better: the metaphor of the “warrior against evil” distorts the weight and the meaning of any illness, loading sicks with responsibilities they do not have: framing illnesses as a personal battle obscures that health as a collective issue (Sontag 1978).

With reference to COVID-19, there are many reflections on the causes and effects of the pandemics on individuals and society as well as on similarities and differences (behavioral, cultural, social, and economic) among countries and people affected. However, some types of conceptual metaphor are more frequent than others (Lakoff 2014) and, among these, war metaphors are dominant (Jackson 2018). As it is apparent, framing this issue in a resistance-driven logic may impede a positive social response, also inhibiting social resilience. Therefore, it is worthwhile to observe this issue more in watermark and consider its semantic field. To fill this gap, this work discusses the need for new metaphors—namely vicariance, bricolage, and exaptation—as social sense makers aimed at reframing an effective socially resilient response in the post-COVID-19 era. COVID-19 is a societal outcast too deadly to ignore and provides the chance to reflect on issues and lessons learned within the design of new social resilience and adaptation paths. The work is structured as follows: rooted in metaphors and resilience literature (Section 2), first the paper investigates the main dimensions of social resilience (Section 2.1) and on the metaphorical meaning of resilience in the COVID-19 context (Section 2.2). Then, by adopting the methodological lens offered by the critical discourse analysis (CDA) (Section 4), the paper deepens war metaphors and their impact on framing COVID-19 response (Section 3), underlying the need to switch from a robust (yet fragile) logic to a resilient logic. Then, bricolage, vicariance, and exaptation are discussed as useful mental images to reframe and make sense from the new post COVID-19 outbreak context (Section 5). Eventually, the paper addresses implications and conclusion (Section 6).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Resilience and Its Building Blocks

Socially conceived, resilience is a process of sensemaking resulting from the interplay of three dimensions—i.e., modularity and scale, social metabolism, and emergence (Thompson 1967; Barile et al. 2019; La Sala 2020; La Sala et al. 2022)—each referred to specific social behaviors, that is by resistance, adaptation, and transformability. In what follows, the paper will briefly attempt to describe these dimensions.

Modularity and scale are central in describing resilience (Thompson 1967; West 2017). In its most elemental form, scaling simply refers to how a system responds when its size changes. Addressing this issue has remarkably profound consequences across the entire spectrum of science and affects almost every aspect of human life (Gould and Lewontin 1979; Bettencourt et al. 2007). Even more challenging and of greater urgency is understanding how to scale social structures of increasing size and complexity (such as cities or governments), where the underlying principles are typically not well understood because of the nature of adaptive systems. Almost any quantifiable characteristic of a complex system typically scales nonlinearly.

To be more precise, social systems’ nonlinear behavior reflects a complementary double effect (Pentland 2014; Moffett 2019):

- -

- a systematic enhancement in terms of performance (e.g., a higher level of GDP), when size increases;

- -

- a systematic saving of energy, when size increases (i.e., reduced metabolism).

Under this light, this principle mainly attains to resistance. In fact, the context that institutions and societies share and in which they survive is liquid and unstable (Beck 1992; Bauman 2000; Taleb 2007). This precarious state makes the whole future uncertain and prevents any form of rational anticipation (Bourdieu 1988). In this sense, modularity and scalability only allow social systems to couple or decouple the (already existent) links among components (Scott 1988; Orton and Weick 1990), to modify their behavioral dynamics and performance by modifying the scale (West 2017). In social terms, this usually happens by acting on the normative system (Powell and DiMaggio 2012; Barile et al. 2019).

Social metabolism refers to adaptation. In biology, systems are controlled and maintained by metabolic processes expressed in terms of metabolic rate, that is the amount of energy needed per second to keep an organism alive (Nicholson and Wilson 2003; de Molina and Toledo 2014; West 2017). Therefore, concerning social systems, the major portion of this energy is devoted to forming communities and institutions (Martinez-Alier 2009). However, no energy transformation happens without consequences: it produces “useless disorder” as a degraded byproduct, and “unintended consequences” in the form of unexpected feedback loops or unworkable social outcomes (West 2017), i.e., entropy (Second Law of Thermodynamics). All systems are subject to the forces of “wear and tear” in its multiple forms. The discourse on entropy underlies any serious attempt to manage the resilience of organisms and societies, given more energy for growth, innovation, maintenance, and repair is needed as systems operate (Crutzen 2006; Steffen et al. 2015). Thus, social metabolism feeds the links among systems’ structural components with the energy they need to maintain viability. In social terms, this energy has an informative nature: the metabolism allows system’s learning and provides the system with the adaptability, plasticity, and cognitive slack (Luhmann et al. 2013), and the ability to read and absorb a wider variety of inputs (Ashby 1956).

Emergence allows the system to overcome simple adaptation (Bocchi and Ceruti 2007). Complex systems are made up of a multitude of single components that, once aggregated, acquire communal properties that normally are not manifested (nor can be easily predicted) considering the properties of the individual components themselves (e.g., a person is more than the totality of cells and tissues) (Von Bertalanffy 1968).

This collective outcome is called emergent behavior: an easily perceptible trait of economies, communities, societies, and organisms. In social terms, personality, identity, and culture all result from the nonlinear nature of the manifold feedback in the interactions among institutions, people, and their environment. In such systems, there is no central control, but rather self-organization, an emergent behavior in which systems’ constituents agglomerate to form a different emergent whole, as with the formation of human social groups (Brent 1978; Schieve and Allen 1982; McKelvey 1999). Furthermore, a small perturbation in one part of the system may have significant consequences elsewhere. The system can be prone to sudden and seemingly unpredictable changes (Pentland 2014).

In fact, the metabolic process that transforms information into energy is not without cost but involves the simultaneous production of entropy. This product is diluted in the system with unpredictable but potentially dangerous effects (e.g., information asymmetry). Therefore, the management of non-linearity cannot take place thanks to a rigid, pre-planned process or to the sole adaptation (Weick 1993; La Sala 2020); instead, it requires a creative process of recombination, which allows societies to reorganize themselves even without planning reorganization (Lévi-Strauss 1966; Gould and Vrba 1982; Berthoz 2013).

Eventually, modularity, social metabolism, and emergence are combined by “sensemaking”. Sensemaking—an intrinsically metaphorical process—relies on the idea that reality is an emergent product of mind that rises from the attempt to create order and make retrospective sense of what occurs (Weick 1995); it is an ongoing, feedback-driven process in which systems simultaneously shape their environments. This feedback helps infer systems’ identity from interaction with other systems and, if well managed, can move the system toward a sense of shared understanding and commonality of purpose.

Sensemaking gives unity to the social action, favoring plausibility over accuracy (Abolafia 2010). States Weick: “in an equivocal, postmodern world, infused with the politics of interpretation and conflicting interests and inhabited by people with multiple shifting identities an obsession with accuracy seems fruitless, and not of much practical help, either” (Weick 1995, p. 61).

2.2. Metaphors and Their Role as Sensemakers in the Social Fabric: The Case of COVID-19 Pandemic

There is vast literature demonstrating metaphors influencing people’s thinking, language, and knowledge (Sontag 1978; Morgan 2016). Aristotle was the first to identify the role of metaphors in the production of knowledge. In Rhetoric, he suggested that “midway between the unintelligible and the commonplace, it is metaphor which most produces knowledge”. In Poetics, he identified the images of metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, and irony as metaphor typologies (although with different shades in meaning). Giambattista Vico (1730), in the XVIII century, was the first to recognize the importance of metaphors as modes of experience, with more than symbolic significance. However, it was only with first works on the role of language and symbolism in reality building (Cassirer and Cassirer 1946; Wittgenstein 1953; White 1978; Morgan 1983) that these ideas acquired major prominence. From then and over sixty years, several works, particularly in linguistics, hermeneutics, semiology, and psychoanalysis, stressed metaphors’ role as a “form of life” (Wittgenstein 1961; Black 1962; Ricoeur 1975; Eco 1986; Brown 1978; Manning 1979; Schön 1979; Tilley 1999). This is because metaphors pervade ordinary language (Lakoff and Johnson 1980): speaking and writing are inherently metaphorical, and life is lived through metaphors (Eco 2017). Metaphors imply defining one thing in terms of another, where the two are different, but one can perceive similarities between them (Tsoukas 1991; Gherardi 2000; Baker et al. 2003; Cameron and Stelma 2004; Kuusi et al. 2016). Consequently, metaphors are crucial sensemaking tools (Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Semino 2021).

Therefore, in these terms, it is apparent that illness (and COVID-19 in particular) may be exactly the type of subjective experience that could be conceptualized and emotionally experienced through metaphors (Tay 2016). To give an example, when Boris Johnson talked about “fighting” in his 17 March 2020 speech, he was intending to reduce the infection, disease, and death of the new coronavirus as it was a violent physical confrontation with an opponent. The two are different, but there are similarities (e.g., both are dangerous matters involving injury to people and potentially death).

Nevertheless, metaphors are not neutral in representing reality. According to the conceptual metaphor theory (Lakoff and Johnson 1980), a metaphor (i.e., source domain) only highlights specific features of the object which aims to describe (i.e., target domain) and overshadows others, facilitating social inference (Lakoff and Johnson 1980). For example, war metaphors for disease highlight illness and complete elimination and overshadow the idea of adapting to and living with it. Metaphors are central rhetorical devices because they explain and persuade (Semino 2021). This line shows that a new virus, causing disease and death worldwide and requiring fast responses from governments and citizens, is told via metaphors.

The most common metaphors draw on basic experiences (Sontag 1978). For example, facing an aggressive animal may threaten survival: this scenario may be metaphorically exploited by describing a range of less tangible problems such as injury or pain (Grady 2017). Military power or invaders are clear examples of dangerous adversaries, while wars are the most direct way to deal with them. This explains the use of war metaphors to talk about a pressing problem such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Atanasova and Koteyko 2017; Semino et al. 2018; Wicke and Bolognesi 2020).

There are several potential structural correspondences between war and pandemic, such as between virus and enemy, health workers and army, sick people and victims, and virus elimination and victory (Ribeiro-Silva et al. 2018). Critics of war metaphors are right to be concerned, but they can also have their usefulness, depending on the context (Flusberg et al. 2018). For example, war metaphors can increase attention to serious and urgent social problems (e.g., climate change) (Flusberg et al. 2017; Landau et al. 2018). However, war metaphors can also have potentially counterproductive framing effects. For example, in the context of cancer prevention, battle metaphors increased fatalism and decreased self-limiting behaviors to reduce cancer risk (Hauser and Schwarz 2015, 2020). Similarly, because the pandemic requires most citizens to abstain from their normal activities, framing the virus as an enemy to be fought could contradict social-distancing messages (Wicke and Bolognesi 2020).

Indeed, the portrayal of populist leaders (e.g., Boris Johnson or Donald Trump) as too solid to be crushed by the virus may reinforce the perception that recovery depends on character, rather than demographic and genetic characteristics, social circumstances, or medical treatments.

This perception supports the concern that war metaphors may legitimize even disproportionate authoritarian measures well beyond the specific pandemic response (Table 1). Indeed, the establishment of martial law and war powers for the executive in several countries reveals the potentially blurred boundary between military references’ literal and metaphorical status during the pandemic (Semino 2021).

Table 1.

War metaphors, grey rhinos1, and COVID-19 metaphorical framing.

Thus, accordingly, this study is built around two main research questions:

- R.Q. 1: How did the war-driven discourse affect the framing of the current COVID-19 pandemic and consequent social response?

- R.Q. 2: Are there any viable discourse alternatives useful to build social resilience?

3. Results: War Metaphors as a R-Y-F (Robust-Yet-Fragile) Response

War metaphors are pervasive in sensemaking about COVID-19: hospital trenches, virus front, and wartime economy. However, rather than treating a health emergency as a complex sociocultural problem, war metaphors make one obedient and docile, almost like a designated victim. Sick people become inevitable losses, being dehumanized as they lose their health. Sick people, victims of the disease, are also victims of the metaphor of the disease: to be sick is to be invaded by an enemy and to die is a defeat. Metaphors of struggle and resistance are not any better: the metaphor of the “warrior who defeats evil” not only distorts the weight (including the psychological weight) of the illness, loading sick people with responsibilities, expectations, and individual guilt, but also the relationship between individuals and society. As Sontag (1978) points out, the representation of illness as a personal battle obscures the fact that health and its preservation are collective issues.

With reference to COVID-19, there are many articulate reflections on the causes of the pandemic, on the effects on individuals and society, and on the similarities and differences (behavioral, cultural, social, and economic) among countries and people affected by the virus. However, some types of conceptual metaphor—which activate the mental frames that determine our worldview (Lakoff 2014)—are more frequent than others. Among these, the metaphor of war is dominant, especially in emergency situations of crisis and of problematic consensus management (Jackson 2018). It was worthwhile, then, to observe it more in watermark and consider its semantic field.

As seen, war is “declared” and “fought”, and effective “weapons” are sought and used to entrust to “warriors” who have the “responsibility to fight” (Table 2a).

Table 2.

(a)—War, weapons, warriors: COVID-19 and war metaphors. (b)—Battles and trenches: COVID-19 and war metaphors.

Soldiers have behind them an entire country, a “war economy”. A hyperbolic metaphor, but certainly functional to the circularity of the reasoning: if there is an economy of war, then there are also armies, weapons, and war itself.

The battle, however, takes place mainly at the “war front”, a very productive phrase in terms of locutions: “on the front of the Coronavirus”, “going to the front”, “at the front of”, “to face”, “health front”, and “new front”.

Moreover, at the front, one is “in the trenches” facing daily “battles”: a trench as big as a city or an entire country. A trench where the fight happens against an “invisible enemy” (Table 2b).

“Invisible enemy” is a widespread expression in the language of information and politics. To only provide few examples, it was used by Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte (17 March 2020) in his speech for the 159th Anniversary of Italian Unification2. It was used by the German weekly Bild (21 March 2020)3, by the Spanish daily ABC, and in an editorial by Ferran Garrido4.

However, this framing response is not functional for society as a whole to reorganize its main activities. Warlike metaphors recall and spread the need to resist much more than the awareness to change. Even the idea of “anticipation”, which relies under the idea of “fighting an enemy”, drives society more toward “designed robustness”—a Robust-Yet-Fragile (RYF) response—than emergence.

The expression Robust-Yet-Fragile (RYF) identifies a precise complex system greatly capable of dealing with programmed and predictable events, but profoundly vulnerable to unforeseeable events (Doyle et al. 2005). Indeed, these systems are built on a structural compromise between efficiency–fragility and inefficiency–robustness. An efficient, clock-like system is linear in its behavior, because it is the sum of discrete parts whose contribution to overall performance is easily isolable (Burns and Stalker 1961). Such a system, although allowing relevant advantages in terms of cost efficiency and speed of intervention, is more exposed to a wide range of structural shocks: its linearity, built around well-recognized and standardized procedures and strict cause-effect relations, is unable to describe the emergencies and feedbacks of social and organizational phenomena (Harari 2018; La Sala et al. 2022). On the contrary, a robust, resource redundant system would not wholly allow to develop adequate capacities to respond to change (Taleb 2012): “by creating a synthesis between efficiency and robustness, the compensatory structure of RYF systems balance advantages from linearity and those from complexity” (La Sala et al. 2022, p. 1348). However, while this compensatory structure expands, the same redundancy that allowed to cope with environmental variance may turn into fragility: the effort to provide the system with variety (Ashby 1956; Barile 2009) and redundancy (Castells 2002; Simone et al. 2017a) increases its vulnerability. Close to the turning point, even the slightest unplanned disturbance can lead the entire system to a different state (Holling 1973; Prigogine and Stengers 1984; Maldonado et al. 2020): the possibility of impacting events occurring becomes endogenous to the system (Taleb 2007). This vulnerability happens because previously designed redundancy is directly chained to the issues that undermine the system: they are part of the narration that has been overcome by events (La Sala et al. 2022).

4. Methodology

Because metaphors are pivotal for conveying positions and beliefs and for providing meaning to complex events (Lakoff and Johnson 1980), frequently with a persuasive function (Kitis and Milapides 1997; Charteris-Black 2009), they are key linguistic devices for constructing, contesting, or legitimising specific social, cultural, political, and ideological representations of the world (Fairclough 2001; Musolff 2012). Furthermore, metaphors are crucial tools for conceptualising diseases (e.g., SARS and avian flu—(Larson et al. 2005; Wallis and Nerlich 2005; Chiang and Duann 2007; de la Rosa 2008)—where metaphors have been framed as rhetorical devices).

Accordingly, for this study, critical discourse analysis (CDA) was adopted, a qualitative orientation whose main objective is to analyse how power is enacted, reproduced, and resisted through text or discourse (Fairclough 2001).

The main objective is to explore how war metaphors were employed during the COVID-19 pandemic as a crisis management tool. The focus is on goals of the communicative practices of spokespersons in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, understanding language as “a goal-oriented activity that takes place within a set of contextual constraints” (Ihnen and Richardson 2011, p. 235) and metaphors as “actions embedded in broader discursive activities” (Musolff and Zinken 2009; Castro Seixas 2021); a sample of speeches and interviews given by key political representatives during the COVID-19 pandemic was selected, focusing on the month of March 2020, when most countries planned restrictive measures. Therefore, attention will be paid to the social, institutional, and political conditions in which metaphorical discourse is produced (Reisigl and Wodak 2001).

Speeches were selected based on their (predominant) use of war metaphors. The complete speeches:

- were consulted from official websites in the original language;

- were read and coded according to their use of war metaphors and in relation to communication and crisis management.

The excerpts (presented here in their English translation) were selected for their relevance to highlight these various associations with communication and crisis management by national and local Italian and international media.

5. Discussion

New Metaphor Clusters in Post-COVID-19 Era: Bricolage, Vicariance and Exaptation to Foster Social Resilience

As seen, the essence of resilience is the intrinsic ability to dynamically maintain or regain equilibrium, preserving viability after a major mishap and in the presence of continuous stress (Hollnagel et al. 2006; Zolli and Healy 2012). Differently from resilience, resistance is the ability to resist damage remaining substantially unchanged until breaking: it represents the systems’ imperturbability to change (Bottrell 2009; Batty 2013). Resistance does not ensure the systems access to alternative resources, nor its structures restoration nor the recovery of its essential functions: if a system resists, it purely means that its resources were sufficient to withstand (Adger 2006; Barile et al. 2019). However, a strategy that fully relies on resistance is very costly, potentially harmful, and likely in conflict with social norms and individual freedom. When such a strategy fails, the system becomes rigid (Thompson 1967), and once broken it is irreparable (Barile et al. 2019). Therefore, the more a system strengthens its boundaries to resist, the higher the risk that it becomes rigid, the greater it loses the capacity to absorb change, and the greater is the speed with which this loss occurs in a recursive feedback loop toward vulnerability.

This also provides the basis for detecting the role of decision-makers and institutions in making a system vulnerable, only resistant, or wholly resilient (Barile 2009; La Sala 2020). The issues the COVID-19 pandemic posed seem to dictate the end of consolidated models (mental, educational, strategic, organizational, cultural, and social) and, at the same time, they ask for new approaches to succeed—or at least to survive—in such complex landscape. COVID-19 acted as a huge amplifier. Thus, how could societies react to these pressures? How do present war metaphors shape social sensemaking? Moreover, because metaphors are world-creator devices, which mental images are needed to overcome this social impasse?

This reorganization happens because of creativity and second-order change. Therefore, in what follows, we propose three metaphor clusters that might be used to reshape social response: i.e., bricolage, vicariance, and exaptation.

A first category to reshape the post-COVID-19 is bricolage. The Savage Mind (Lévi-Strauss 1966) presents “bricolage” and “bricoleur” as analogies to holistically describe a particular relationship that human beings entertain with the world. The term is used in political science (Cleaver 2002), sociology (Stark 1996), anthropology (Douglas 1986), and philosophy (Baker et al. 2003; Di Domenico et al. 2010). Over the last decades, the notion has gained growing popularity in social sciences (Weick 1993; Duymedjian and Rüling 2010). These contributions mostly chain bricolage to improvisation (Phillimore et al. 2016): “doing things with whatever is at hand” (Lévi-Strauss 1966, p. 17). Thus, bricolage can be defined as the invention of resources from what is available to manage unforeseen issues. It is a local, contextual process, not conceivable outside of the specific situation in which it appears (Ciborra 1999, 2002). This “practical intelligence” is manifested in how people and societies (re)organize their resources and activities to undertake their goals and how they reorganize to adapt to unexpected circumstances (Weick 1993; Wagner 2000; Pina e Cunha 2005; Taleb 2007, 2012).

Under this light, bricolage also plays a central, still largely ignored, role in institutional engineering, where it often occurs not on the ruins but with the ruins of the old regime, as available resources are deployed to respond to emerging practical dilemmas (Douglas 1986; Lanzara 1998; Grandori 2020).

The above-mentioned authors stress the visible side of bricolage as they focus on the recombination of physical and socio-economic resources “at hand” in the adjacent environment. However, bricolage also pertains to the manipulation of symbolic resources. Lévi-Strauss himself uses bricolage in a semiotic sense, stating how actors “build ideological castles out of the debris of what was once a social discourse” (Lévi-Strauss 1966, p. 21). The literature shows how actors recombine “available and legitimate concepts, scripts, models and other cultural artifacts that they find around them in their institutional environment” (Douglas 1986, pp. 66–67). This type of (cultural) bricolage can lead to new sociocultural recombination in which internal and external skills and habits are blended (Perkmann and Spicer 2014; Prosperi 2018; Välikangas and Lewin 2020).

Furthermore, bricolage has been defined as the “process of sensemaking that makes do with whatever materials are at hand” (Weick 1993, pp. 351–52): it refers to “mind in action” (Scribner 1986, p. 15) where resource allocation may not be adequate. This clarifies why bricolage is normally adopted in critical situations (Rerup 2001; Montuori 2003), when it is urgent using the world, obtaining what is needed, and doing what must be done (Lewin 1998; Vera and Crossan 2004).

Lévi-Strauss’s bricoleur possesses intimate knowledge of the elements belonging to a given repertoire, which is based not on an exhaustive and complete understanding of what things are, but of how they can be related to one another, being one of the key elements in fostering resilience in crisis situations (Weick 1993, 1998, 2004). In this context, Homerian Odysseus could provide a clear example of a bricoleur. Odysseus, in fact, never complains of inadequacy of resources but, making do with whatever resources are available, he recombines useless materials in line with his goals (Gabriel 1995, 2010).

Vicariance contributes to what Ashby (1956) calls “information variety endowment” of individuals, organizations, and societies, being an essential capability to prosper in complex environments (Simone et al. 2017b). The term comes from the Latin “vicarious” which literally means “substitute”. It has been associated to simplexity (Berthoz 2009), bifurcation (Prigogine and Stengers 1984), and creative deviation from the previous extant path. Similarly, according to the neuroscientist Alain Berthoz (2013), vicariance refers to a process that supersedes another process that might lead to the same result.

Therefore, metaphorically speaking, vicariance provides a mental image which fosters resilience, because it proposes new ways of thinking and imagining notable changes that can positively disrupt the expected pattern of events. These internal models are analogical representations of reality, explicative tools that individuals use to interact with the environment, perceptive, and manipulative experience of their world (Norman 1983; Gentner and Stevens 2014). Internal models are “mental simulation” of a real problematic situation, feasible causal models for the system they represent (Greca and Moreira 2000). These simulations involve the envisioning of the social system, the representation of its components and their structural relations, and the running or the execution of the causal model (Duymedjian and Rüling 2010). Internal models are recursive and dynamic (Reuchlin 1978; Johnson-Laird 1983): they are never complete; they continue to be expanded as new information is included. This iterative process depends on the subject’s knowledge, on the scheme that relies under the model (Greca and Moreira 2000; Barile 2009). This principle is known as vicariance for model building. Moreover, internal models will not only be useful to anticipate the effects of an action and its adjustment according to the constraints of the task or the environment. They have the additional property of allowing to simulate the act to find alternative strategies or to arrange another movement that can perform the same task. They can drive toward new, unprecedented actions in the normal functional repertoire.

Exaptation (Gould and Vrba 1982) is a concept defined by its relation to adaptation, that is a function that is shaped through natural selection for a particular purpose. However, given that evolution is nonlinear (Darwin 1859), how does one name a feature that evolved for one reason but was later co-opted for a new purpose? Gould and Vrba proposed the term exaptation. In short, not everything in nature is useful for something, but everything can always come in handy. Bird feathers may be an early example: feathers originated for thermoregulation and were later co-opted to catch insects. Then, large contour feathers and their arrangement on the arms—emerged as a secondary adaptation—were co-opted for flight. According to Gould and Vrba (1982), such preaptation is a source of exaptation.

In addition, there is a second alternative, i.e., nonaptation. Nonaptation refers to current features whose origins cannot be attributed to any previous direct action of natural selection. An example is the sutures of the mammalian brain. At birth, mammalian skull bones are not completely sutured together. Without this feature, humans could not pass through the birth canal due to the dimensions of their head. Yet, this cannot be studied as a mammalian adaptation because it is shared with other vertebrates that only need to free themselves from an egg (Gould 1991; Garud et al. 2016).

Eventually, a further typology of nonadaptation comes from causal correlation. To explain it, Gould (1991, 1997) proposed—as a metaphor—the spandrels (in architecture, the triangular spaces resulting from the junction of two arches) of St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The spandrels of San Marco (Venice). Source: Pikaia.eu.

Therefore, an exaptation occurs (Gould and Vrba 1982):

- when a character, selected for a specific aim, is co-opted for new use;

- when a character, which is not related to the direct work of natural selection, is co-opted for its current use.

Once combined, these options constitute an exaptative pool, providing resources for evolution via exaptation, a source of “genetic” variation far beyond mutation and recombination. Furthermore, broadening the exaptation meaning, Vrba and Gould noted that “upward or downward causation to new characters may lead to exaptation” (Gould and Vrba 1982, p. 225). Thus, adaptation can occur not only within a single level, but it may happen across levels (Gould 1991; Pievani 2002).

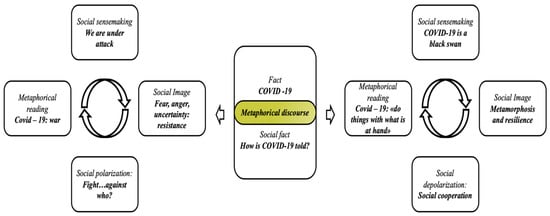

This rereading could significantly impact the way crisis is framed and faced by a given society. Indeed, human society is instinctively predisposed to translate experience into narrative terms (Bruner 1990): this is a cognitive strategy that consists in the construction of stories as interpretative models of reality (Brown et al. 2008; Andersen et al. 2020; Ganzin et al. 2020). From the social point of view, a narrative can be considered as a flexible socio-linguistic tool through which events are ordered, selected, connected, and arranged according to a causal sequence. The narrative is constructed respecting the paradigm of coherence, that is seeking agreement based on what the narrator believes to be reality. The construction follows a principle based on the “before”, the “after”, and the “therefore”; this narrative structure reduces chaos. Thus, a sort of grammar of history is produced, a system of general and abstract expectations about how a given society works, which allows anticipating and predicting the flow of events: expectations are elaborated based on the regularities that society identifies in its relationship with stories and by virtue of the interactive experience with others. The impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had and is still having on social fabric has this nature. While the pandemic was hitting at the very heart of health care, logistics, and instruction, social reaction was designed according to a “narrative of protocol”, oriented toward resistance rather than bricolage, vicariance, and exaptation. This provoked a collapse in sensemaking with a consequent spread of anger, fear, and distrust (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Facts, social facts, and metaphorical discourse: the case of COVID-19. Source: our elaboration.

Every fact that affects the behavioral dynamics of the social system as a whole is the object of interpretation, of narration. It is not, therefore, read in terms of intrinsic objectivity, but in symbolic terms, as a system of meaning, culture, and beliefs (Moscovici 1976): it is a social fact whose meaning is closely linked to the sense that society attributes to it. Every social representation is, therefore, the product of words and images that construct meaning around the event (Judge 2016). Words make the world, as George Orwell recalls in his 1984. Who is the “enemy”, then? The virus, possibly. However, precisely because the virus is invisible, fluid, intangible, and abstract, rhetoric leaves room for other implicit, evoked, and variable enemies: the hunt for an enemy, the circumspect gaze, anger, populism, and racism. The “enemies” to be waged war against have multiplied. They simply are the others. Enemies are not needed, then: better, by weighting and choosing words, reshaping a new social sensemaking and being aware that in shocks there are no certainties. Social resilience only comes from this.

Therefore, social resilience is not the result of a voluntary adaptation, yet it emerges from the limited-but-redundant availability of resources, from a process of natural recombination, from a recursive cycle of hypotheses and rejection of hypotheses (Popper 1945), and from the work of a “sensemaking” bricoleur. The result, as happens with the spandrels of San Marco, can be far from what is expected.

6. Conclusions

This paper has shown the relevance of metaphors and their constructivist and evocative power: metaphors stimulate an emergent stream of thinking that often goes well beyond the concepts that they initially suggest.

For these reasons, given the exponential acceleration that social systems are experiencing in terms of unpredictability, non-linearity, and emergence—during and after the COVID-19 pandemic—a new discourse is increasingly required to deepen the adaptive nature and unpredictable evolutionary path on this emerging environment. As seen, war metaphors are particularly hazardous: every day it becomes clearer that COVID-19 knows no boundaries and requires a unified global response. Talking about war, invasion, and heroism, with a nineteenth-century war lexicon, distances from the idea of unity and sharing of objectives that will allow to emerge from it.

This is an epochal phenomenon, and it will be impossible to think of a future without virus: the idea to eliminate it is illusory. It is a resistance logic. Any war metaphor to describe illness is not only harmful to any society, but deeply flawed. It is not possible to “kill” the virus, rout it, or bomb it. Nor it is possible to remove it from our awareness and our lives. Indeed, it must be contained, designing a future for which being prepared. The public discourse needs to speak the language of care, travel, and change. Social care not only means attention to medical and hygienic aspects, but also to ethical and social ones; it means paying close attention to how the pandemic is changing society and the relationship with institutions. When an entire society is in care, it needs a clear, limpid communication. As long as communication will be set in terms of war, it will be felt a continuous state of emergency, of threat and attack.

Starting to think in terms of care, travel, and change, instead, may contribute to the construction of a more conscious society, ready to rebuild its future. Bricolage, vicariance, and exaptation well address this perspective because they directly push on the functional and cognitive discourse that characterizes societies as viable entities. This shift will allow not only to overcome the COVID-19 pandemics, but also to prepare for all the other changes coming.

However, the dependence among these levers, resilience, and social change clearly deserves much attention because it can lay the foundations for further theoretical analyses supported by empirical research.

Moreover, the communicative issue is directly related to the informational issue. Metaphors are vehicles of social construction, central in the representation and dissemination of the cultural image of each social group. The impact of the digital revolution and the medial transition could change their nature and communicative effectiveness.

Indeed, this is an issue that cuts across institutions (and the associated risk of disintermediation) and the nature of information (in particular, information overload and partisan information).

Thus, a reflection on the socio-cultural level becomes imperative: on the one hand, accuracy and verification of sources are slowly being replaced by emotionality and the speed of media fruition; on the other hand, the metaphorical construction itself is a cultural construct and recalls, in accordance, precise meanings with each change in the social context. Communication by metaphors cannot ignore this double level of analysis.

This work views the beneficiaries of the research as anyone impacted by the conception of the health emergencies as war or resistance metaphors. Since these war and resistance metaphors have had far-reaching and disempowering effects in COVID-19 as well as other contexts, we view the impact of reframing to adaptive metaphors as wide-reaching. For example, by reframing their conceptualization of COVID-19 through the use of vicariance, bricolage, and exaptation metaphors, the definition of the problem shifts, and different alternatives open up for responses. Policy makers and governments can respond in more flexible, rather than rigid, ways to health emergencies such as COVID-19. Rather than encouraging a disempowering, victim narrative, these alternative conceptions provide a stronger sense of individual and collective self-efficacy. Hopefully, the use of different metaphors by policy makers will also influence media discourses about the current and future health emergencies, which could also reinforce their use by policy makers and individuals and move away from attack-and-defend conceptions.

In sum, the attempt of this study and its contribution has been threefold. First of all, the study has shown how metaphorical discourse was used during the COVID-19 pandemic; second, by stressing the use of war metaphors, the paper has shown how war-driven discourse acted as an inhibitor of social resilience; and eventually, the work proposes new metaphorical clusters (namely, bricolage, vicariance, and exaptation) to help policy-makers in reframing communication not only for the current pandemic but for further challenging events yet to come.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.S.; Methodology, A.L.S., R.P.F. and M.C.; Writing—original draft, A.L.S. and R.P.F.; Writing—review & editing, A.L.S., R.P.F. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A gray rhino is a metaphor coined by risk expert Michele Wucker to describe ‘highly obvious, highly probable, but still neglected’ dangers, as opposed to unforeseeable or highly improbable risks—the kind in the black swan metaphor. |

| 2 | https://twitter.com/giuseppeconteit/status/1239840430847668230 (accessed on 1 November 2021). |

| 3 | |

| 4 |

References

- Abolafia, Mitchel Y. 2010. Narrative construction as sensemaking: How a central bank thinks. Organization Studies 31: 349–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, Neil W. 2006. Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change 16: 268–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Ditte, Signe Ravn, and Rachel Thomson. 2020. Narrative sense-making and prospective social action: Methodological challenges and new directions. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 23: 367–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, W. Ross. 1956. An Introduction to Cybernetics. London: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Atalan, Abdulkadir. 2020. Is the lockdown important to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic? Effects on psychology, environment and economy-perspective. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 56: 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atanasova, Dimitrinka, and Nelya Koteyko. 2017. Metaphors in Guardian Online and Mail Online opinion-page content on climate change: War, religion, and politics. Environmental Communication 11: 452–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Ted, Anne S. Miner, and Dale T. Eesley. 2003. Improvising firms: Bricolage, account giving and improvisational competencies in the founding process. Research Policy 32: 255–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, Sergio, Cristina Simone, Antonio La Sala, and Marcelo Enrique Conti. 2019. Surfing the complex interaction between new technology and norms: A resistance or resilience issue? Insights by the Viable System Approach (VSA). Acta Europeana Systemica 9: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, Sergio. 2009. Management Sistemico Vitale. Torino: Giappichelli. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, Michael. 2013. The New Science of Cities. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Modernity and the Holocaust. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz, Alain. 2009. Simplexité (La). Paris: Odile Jacob. [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz, Alain. 2013. La vicariance: Le Cerveau Créateur de Mondes. Paris: Odile Jacob. [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt, Luís M. A., José Lobo, Dirk Helbing, Christian Kühnert, and Geoffrey B. West. 2007. Growth, innovation, scaling, and the pace of life in cities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104: 7301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Max. 1962. Models and Metaphors: Studies in Language and Philosophy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bocchi, Gianluca, and Mauro Ceruti, eds. 2007. La Sfida Della Complessità. Milan: Pearson Italia Spa, vol. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Bottrell, Dorothy. 2009. Understanding ‘marginal’ perspectives: Towards a social theory of resilience. Qualitative Social Work 8: 321–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1988. Vive la crise! Theory and Society 17: 773–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, Sandor B. 1978. Prigogine’s model for self-organization in nonequilibrium systems. Human Development 21: 374–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Andrew D., Patrick Stacey, and Joe Nandhakumar. 2008. Making sense of sensemaking narratives. Human Relations 61: 1035–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Richard Harvey. 1978. A Poetic for Sociology: Toward a Logic of Discovery for the Human Sciences. CUP Archive. Cambridge: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, Jerome Seymour. 1990. Acts of Meaning. Four Lectures on Mind and Culture. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Tom, and George M. Stalker. 1961. Mechanistic and organic systems. In Classics of Organizational Theory. Essential Theories of Process and Structure. London: Routledge, pp. 209–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Lynne J., and Juurd H. Stelma. 2004. Metaphor clusters in discourse. Journal of Applied Linguistics 1: 107–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassirer, Ernst, and Ernst Alfred Cassirer. 1946. Language and Myth. Chelmsford: Courier Corporation, vol. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 2002. The Internet Galaxy: Reflections on the Internet, Business, and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Seixas, Eunice. 2021. War metaphors in political communication on COVID-19. Frontiers in Sociology 2021: 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charteris-Black, Jonathan. 2009. Metaphor and political communication. In Metaphor and Discourse. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, Wen-Yu, and Ren-Feng Duann. 2007. Conceptual metaphors for SARS: ‘War’ between whom? Discourse & Society 18: 579–602. [Google Scholar]

- Ciborra, Claudio U. 1999. Notes on improvisation and time in organizations. Accounting, Management and Information Technologies 9: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciborra, Claudio U. 2002. The Labyrinths of Information. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver, Frances. 2002. Reinventing institutions: Bricolage and the social embeddedness of natural resource management. The European Journal of Development Research 14: 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, Paul J. 2006. The “anthropocene”. In Earth System Science in the Anthropocene. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles. 1859. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. New York: International Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa, Victoria Martín. 2008. The Persuasive Use of Rhetorical Devices in the Reporting of ‘Avian Flu’. Vigo International Journal of Applied Linguistics 5: 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- de Molina, Manuel González, and Víctor M. Toledo. 2014. The Social Metabolism: A Socio-Ecological Theory of Historical Change. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Di Domenico, MariaLaura, Helen Haugh, and Paul Tracey. 2010. Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34: 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, Francesco, Damiano Pizzol, Claudia Marotta, Mario Antunes, Vincenzo Racalbuto, Nicola Veronese, and Lee Smith. 2020. Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) current status and future perspectives: A narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, Mary. 1986. How Institutions Think. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, John C., David L. Alderson, Lun Li, Steven Low, Matthew Roughan, Stanislav Shalunov, Reiko Tanaka, and Walter Willinger. 2005. The “robust yet fragile” nature of the Internet. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102: 14497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duymedjian, Raffi, and Charles-Clemens Rüling. 2010. Towards a foundation of bricolage in organization and management theory. Organization Studies 31: 133–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco, Umberto. 1986. Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, vol. 398. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 2017. Dall’albero al Labirinto: Studi Storici sul Segno e L’interpretazione. Milan: La Nave di Teseo Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2001. Critical discourse analysis as a method in social scientific research. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis 5: 121–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Walter R. 1984. Narration as a human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communications Monographs 51: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flusberg, Stephen J., Teenie Matlock, and Paul H. Thibodeau. 2017. Metaphors for the War (or Race) against climate change. Environmental Communication 11: 769–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flusberg, Stephen J., Teenie Matlock, and Paul H. Thibodeau. 2018. War metaphors in public discourse. Metaphor and Symbol 33: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, Yiannis. 1995. The unmanaged organization: Stories, fantasies and subjectivity. Organization Studies 16: 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, Yiannis. 2010. Organization studies: A space for ideas, identities and agonies. Organization Studies 31: 757–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzin, Max, Gazi Islam, and Roy Suddaby. 2020. Spirituality and entrepreneurship: The role of magical thinking in future-oriented sensemaking. Organization Studies 41: 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, Raghu, Joel Gehman, and Antonio Paco Giuliani. 2016. Technological exaptation: A narrative approach. Industrial and Corporate Change 25: 149–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner, Dedre, and Albert L. Stevens, eds. 2014. Mental Models. London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gherardi, Silvia. 2000. Practice-based theorizing on learning and knowing in organizations. Organization 7: 211–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, Stephen Jay, and Elisabeth S. Vrba. 1982. Exaptation: A missing term in the science of form. Paleobiology 8: 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, Stephen Jay, and Richard C. Lewontin. 1979. The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: A critique of the adaptationist programme. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B Biological Sciences 205: 581–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, Stephen Jay. 1991. Exaptation: A crucial tool for an evolutionary psychology. Journal of Social Issues 47: 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, Stephen Jay. 1997. Evolution: The pleasures of pluralism. The New York Review of Books 44: 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Grady, Joseph. 2017. Using metaphor to influence public perceptions and policy: How metaphors can save the world. In The Routledge Handbook of Metaphor and Language. Edited by Elena Semino and Zsofia Demjén. London: Routledge, pp. 343–54. [Google Scholar]

- Grandori, Anna. 2020. Black swans and generative resilience. Management and Organization Review 16: 495–501. [Google Scholar]

- Greca, Ileana Maria, and Marco Antonio Moreira. 2000. Mental models, conceptual models, and modelling. International Journal of Science Education 22: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Harari, Yuval Noah. 2018. 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, David J., and Norbert Schwarz. 2015. The war on prevention: Bellicose cancer metaphors hurt (some) prevention intentions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 41: 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, David J., and Norbert Schwarz. 2020. The war on prevention II: Battle metaphors undermine cancer treatment and prevention and do not increase vigilance. Health Communication 35: 1698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holling, Crawford S. 1973. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, Erik, David D. Woods, and Nancy Leveson, eds. 2006. Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson, Gillian C., and Sandra Hogarth-Scott. 2001. “What happened was…broadening the agenda for storied research”. Journal of Marketing Management 17: 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihnen, Constanza, and John E. Richardson. 2011. On combining pragma-dialectics with critical discourse analysis. In Keeping in Touch with Pragma-Dialectics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 231–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Richard. 2018. Writing the War on Terrorism: Language, Politics and Counter-Terrorism. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Laird, Philip N. 1983. Mental Models: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference, and Consciousness (No. 6). Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, Anthony. 2016. Metaphor as fundamental to future discourse. Futures 84: 115–19. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, Jesse M. 2020. COVID, resilience, and the built environment. Environment Systems and Decisions 40: 216–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kitis, Eliza, and Michalis Milapides. 1997. Read it and believe it: How metaphor constructs ideology in news discourse. A case study. Journal of Pragmatics 28: 557–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kuusi, Osmo, Outi Lauhakangas, and Ruuta Ruttas-Küttim. 2016. From metaphoric litany text to scenarios—How to use metaphors in futures studies. Futures 84: 124–32. [Google Scholar]

- La Sala, Antonio, Ryan Patrick Fuller, and Marcelo Enrique Conti. 2022. Neither backward nor forward: Understanding crazy systems resilience. Paper presented at IFKAD 2022 Proceedings—17th International Forum for Knowledge Assets Dynamics: Knowledge Drivers for Resilience and Transformation, Lugano, Switzerland, June 20–22; pp. 1339–52. [Google Scholar]

- La Sala, Antonio. 2020. Resilience in Complex Socio-Organizational Systems. From the State-of-the-Art to an Empirical Proposal. Rome: Edizioni Nuova Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 2014. The All New Don’t Think of an Elephant! Know Your Values and Frame the Debate. Hartford: Chelsea Green Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, Mark J., Jamie Arndt, and Linda D. Cameron. 2018. Do metaphors in health messages work? Exploring emotional and cognitive factors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 74: 135–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzara, Giovan Francesco. 1998. Self-destructive processes in institution building and some modest countervailing mechanisms. European Journal of Political Research 33: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, Brendon M. H., Brigitte Nerlich, and Patrick Wallis. 2005. Metaphors and biorisks: The war on infectious diseases and invasive species. Science Communication 26: 243–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lederach, John Paul. 1996. Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation across Cultures. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1966. The Savage Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, Arie Y. 1998. Introduction—Jazz improvisation as a metaphor for organization theory. Organization Science 9: 539–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Luhmann, Niklas, Dirk Baecker, and Peter Gilgen. 2013. Introduction to Systems Theory. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, Deborah. 2020. Special section on “Sociology and the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic”. Health Sociology Review 29: 111–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, Ana D., Maria Morales, Pedro A. Aguilera, and Antonio Salmerón. 2020. Analyzing uncertainty in complex socio-ecological networks. Entropy 22: 123. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, Peter K. 1979. Metaphors of the Field: Varieties of Organizational Discourse. Administrative Science Quarterly 24: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alier, Joan. 2009. Social metabolism, ecological distribution conflicts, and languages of valuation. Capitalism Nature Socialism 20: 58–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, Bill. 1999. Self-organization, complexity catastrophe, and microstate models at the edge of chaos. In Variations in Organization Science: In Honor of Donald T. Campbell. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 279–307. [Google Scholar]

- Moffett, Mark W. 2019. The Human Swarm: How Our Societies Arise, Thrive, and Fall. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Montuori, Alfonso. 2003. The complexity of improvisation and the improvisation of complexity: Social science, art and creativity. Human Relations 56: 237–55. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Gareth. 1983. More on metaphor: Why we cannot control tropes in administrative science. Administrative Science Quarterly 27: 601–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Gareth. 2016. Commentary: Beyond Morgan’s eight metaphors. Human Relations 69: 1029–42. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici, Serge. 1976. Social Influence and Social Change. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, John F., Jerry Jones, and James Conner. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic: Is it a “Black Swan”? Some risk management challenges in common with chemical process safety. Process Safety Progress 39: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Musolff, Andreas. 2012. The study of metaphor as part of critical discourse analysis. Critical Discourse Studies 9: 301–10. [Google Scholar]

- Musolff, Andreas, and Jörg Zinken, eds. 2009. Metaphor and Discourse. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, Jeremy K., and Ian D. Wilson. 2003. Understanding ‘global’ systems biology: Metabonomics and the continuum of metabolism. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2: 668. [Google Scholar]

- Nicola, Maria, Zaid Alsafi, Catrin Sohrabi, Ahmed Kerwan, Ahmed Al-Jabir, Christos Iosifidis, Maliha Agha, and Riaz Agha. 2020. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal of Surgery 78: 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Donald A. 1983. Some observations on mental models. Mental Models 7: 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Orton, J. Douglas, and Karl E. Weick. 1990. Loosely coupled systems: A reconceptualization. Academy of Management Review 15: 203–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentland, Alex. 2014. Social Physics: How Good Ideas Spread—The Lessons from a New Science. New York: Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perkmann, Markus, and André Spicer. 2014. How emerging organizations take form: The role of imprinting and values in organizational bricolage. Organization Science 25: 1785–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillimore, Jenny, Rachel Humphris, Franziska Klaas, and Michi Knecht. 2016. Bricolage: Potential as a Conceptual Tool for Understanding Access to Welfare in Superdiverse Neighbourhoods. IRiS Working Paper Series 14; Birmingham: Institute for Research into Superdiversity, University of Birmingham. [Google Scholar]

- Pievani, Telmo. 2002. Rhapsodic evolution: Essay on exaptation and evolutionary pluralism. World Futures: The Journal of General Evolution 59: 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina e Cunha, Miguel. 2005. Bricolage in Organizations. Lisbon: Universidade Nova de Lisboa. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, Karl. 1945. The Open Society and Its Enemies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Walter W., and Paul DiMaggio, eds. 2012. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, Ilya, and Isabelle Stengers. 1984. Order out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature. New York: Bantam books. [Google Scholar]

- Prosperi, Adriano. 2018. Identità: L’altra Faccia Della Storia. Gius: Laterza & Figli Spa. [Google Scholar]

- Reisigl, Martin, and Ruth Wodak. 2001. Discourse and Discrimination: Rhetorics of Racism and Anti-Semitism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rerup, Claus. 2001. “Houston, We Have a Problem”: Anticipation and Improvisation as Sources of Organizational Resilience. Philadelphia: Snider Entrepreneurial Center, Wharton School. [Google Scholar]

- Reuchlin, Maurice. 1978. Processus vicariants et différences individuelles. Journal de Psychologie 75: 135–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-Silva, Rita, Deborah C. Malta, Laura C. Rodrigues, Dandara O. Ramos, Rosemeire L. Fiaccone, Daiane B. Machado, and Maurício L. Barreto. 2018. Social, environmental and behavioral determinants of asthma symptoms in Brazilian middle school students—A national school health survey (Pense 2012). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricoeur, Paul. 1975. The Rule of Metaphor: Multi-Disciplinary Studies of the Creation of Meaning in Language. University of Toronto Romance Series; Toronto: University of Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Schieve, William C., and Peter M. Allen, eds. 1982. Self-Organization and Dissipative Structures: Applications in the Physical and Social Sciences. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, Donald A. 1979. Generative metaphor: A perspective on problem-setting in social policy. Metaphor and Thought 2: 137–63. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, John. 1988. Social network analysis. Sociology 22: 109–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scribner, Sylvia. 1986. Thinking in action: Some characteristics of practical thought. Practical Intelligence: Nature and Origins of Competence in the Everyday World 13: 60. [Google Scholar]

- Semino, Elena, Zsófia Demjén, Andrew Hardie, Sheila Payne, and Paul Rayson. 2018. Metaphor, Cancer and the End of Life: A Corpus-Based Study. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Semino, Elena. 2021. “Not soldiers but fire-fighters”–Metaphors and COVID-19. Health Communication 36: 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, Cristina, Antonio La Sala, and Marta Maria Montella. 2017a. The rise of P2P ecosystem: A service logics amplifier for value co-creation. The TQM Journal 29: 863–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, Cristina, Marco Arcuri, and Antonio La Sala. 2017b. Be vicarious: The challenge for project management in the service economy. Paper presented at 20th Excellence in Services International Conference, Verona, Italy, September 7–8; pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi, Catrin, Zaid Asafi, Niamh O’neill, Mehdi Khan, Ahmed Kerwan, Ahmed Al-Jabir, Christos Iosifidis, and Riaz Agha. 2020. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). International Journal of Surgery 76: 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sontag, Susan. 1978. Illness as Metaphor. London: Allen Lane. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, David. 1996. Recombinant property in East European capitalism. American Journal of Sociology 101: 993–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, Will, Wendy Broadgate, Lisa Deutsch, Owen Gaffney, and Cornelia Ludwig. 2015. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The great acceleration. The Anthropocene Review 2: 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. 2007. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. 2012. Antifragile: How to Live in a World We Don’t Understand. London: Allen Lane. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, Dennis. 2016. Using metaphor in healthcare: Mental health. In The Routledge Handbook of Metaphor and Language. London: Routledge, pp. 389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, James. 1967. Organizations in Action: Social Science Bases of Administrative Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, Christopher. 1999. Metaphor and Material Culture. Hoboke: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoukas, Haridimos. 1991. The missing link: A transformational view of metaphors in organizational science. Academy of Management Review 16: 566–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välikangas, Liisa, and Arie Y. Lewin. 2020. The resilience forum: A lingering conclusion. Management and Organization Review 16: 967–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, Dusya, and Mary Crossan. 2004. Theatrical improvisation: Lessons for organizations. Organization Studies 25: 727–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vico, Giambattista. 1730. Principj di una Scienza Nuova intorno alla natura delle nazioni, per la quale si ritruovano i principj di altro sistema del Diritto Naturale delle genti. Florence: Mosca. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bertalanffy, Ludwig. 1968. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. New York: G. Braziller. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Richard K. 2000. Practical intelligence. In Handbook of Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 380–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wallis, Patrick, and Brigitte Nerlich. 2005. Disease metaphors in new epidemics: The UK media framing of the 2003 SARS epidemic. Social Science & Medicine 60: 2629–39. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, Karl. 1993. The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly 38: 628–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, Karl. 1995. Sensemaking in Organisations. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, Karl. 1998. Introductory essay—Improvisation as a mindset for organizational analysis. Organization Science 9: 543–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, Karl. 2004. Normal accident theory as frame, link, and provocation. Organization & Environment 17: 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- West, Geoffrey. 2017. Scale. The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- White, Hayden V. 1978. Tropics of Discourse Essays in Cultural Criticism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wicke, Philipp, and Marianna Bolognesi. 2020. Framing COVID-19: How we conceptualize and discuss the pandemic on Twitter. PLoS ONE 15: e0240010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1953. Philosophical Investigations. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1961. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Translated by Pears and McGuinness. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zolli, Andrew, and Ann Marie Healy. 2012. Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back. Paris: Hachette UK. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).