Abstract

Background: Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a high-risk prodromal stage of dementia. While tablet/computer-based computerized cognitive training (CCT) is widely used, its efficacy and gamification’s role need clarification. Objective: This study aimed to evaluate the effect of tablet/computer-based CCT on global cognition in older adults with MCI and explore the impact of gamification. Methods: We systematically searched five databases for RCTs (through October 2025) involving individuals aged ≥55 with MCI. The intervention was task-based CCT via tablets/computers. Primary outcome was global cognition. We used random-effects meta-analysis and subgroup analyses. Results: Nineteen RCTs (1013 participants) were included. CCT demonstrated a significant, moderate positive effect on global cognition (Hedges’ g = 0.57, 95% CI [0.36, 0.78]). A trend suggesting greater benefits with higher gamification was observed: high (g = 0.71), medium (g = 0.46), and low (g = 0.45) degrees. However, subgroup differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.4333). Results were robust in sensitivity analyses. Conclusions: Tablet/computer-based CCT effectively improves global cognition in MCI. The potential additive value of gamification highlights its promise for enhancing engagement and effects, warranting further investigation in larger trials. This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD420251231618).

1. Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) represents a transitional stage between normal aging and dementia, characterized by measurable cognitive decline that does not yet significantly interfere with daily functioning (Anderson, 2019). Epidemiological data indicate that the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) among individuals aged 60 years and older is approximately 15% to 20%, with an annual progression rate of 8% to 15% from MCI to dementia (DeCarli, 2003; Tahami Monfared et al., 2022). In the context of global population aging, the number of people living with dementia has reached about 50 million worldwide and is projected to increase to 152 million by 2050 (World Health Organization, 2021; Prince et al., 2013). Consequently, interventions that can preserve or enhance cognitive function in this population are of critical clinical importance.

Non-pharmacological interventions have gained growing attention due to the limited efficacy and potential side effects of current pharmacotherapies (Dyer et al., 2018). Among these, computerized or digital cognitive training (CCT/DCT) has emerged as a promising approach that leverages digital technologies to deliver structured, adaptive cognitive exercises targeting multiple domains such as memory, attention, and executive function (Chan et al., 2024; Ge et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2021). Compared with traditional paper-and-pencil training, CCT offers several advantages, including automated feedback, progressive task difficulty, remote accessibility, and high reproducibility (Harvey et al., 2018; Hill et al., 2017).

Computerized cognitive training has evolved into a diverse and versatile intervention approach (Kueider et al., 2012). Compared to traditional immersive systems like virtual reality or motion-based games that rely on specialized hardware and physical spaces, tablet and desktop devices offer significant advantages in widespread accessibility, lower cost, and ease of operation (Burford & Park, 2014). Furthermore, tablet- and computer-based cognitive training programs demonstrate strong environmental adaptability, allowing flexible deployment in diverse settings like homes or clinics without complex setup or continuous professional supervision (Realdon et al., 2016; Zuschnegg et al., 2025). These practical features not only facilitate widespread adoption but also help maintain long-term user engagement. For cognitive interventions, sustained training adherence is crucial for consolidating lasting benefits (Butler et al., 2018; Jaeggi et al., 2011).

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the integration of gamification elements, such as rewards, progress tracking, competition, and narrative feedback into cognitive training programs (Lumsden et al., 2016; Vermeir et al., 2020). Gamified features are hypothesized to enhance intrinsic motivation, user engagement, and emotional reward, potentially amplifying training effects and mitigating attrition (de Paiva Azevedo et al., 2019; Litvin et al., 2020). However, the extent to which gamification improves cognitive outcomes in older adults with MCI remains unclear. Some studies have reported significant improvements in global cognition and memory when game-like designs are employed, whereas others have shown minimal or no added benefit (Coelho et al., 2025; Oldrati et al., 2020).

Numerous trials have evaluated the intervention effects of digital cognitive training in individuals with MCI (Park & Ha, 2024); however, substantial heterogeneity in intervention design, target cognitive domains, training intensity, and user experience has led to inconsistent findings. Furthermore, previous meta-analyses often combined different digital intervention platforms, making it difficult to isolate the independent effects of tablets or computers. Despite the increasing interest in gamified cognitive training, most existing computer-based interventions for MCI remain minimally gamified.

Therefore, a systematic review focusing specifically on (1) task-based digital cognitive training implemented via tablet and computer platforms is warranted, to clarify its overall intervention efficacy and to further examine, (2) through subgroup analyses, the influence of different levels of gamification and other characteristics on training outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). The protocol for this systematic review was registered retrospectively with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the identification number CRD420251231618. A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, and PsycINFO from database inception to October 2025. The following combinations of search terms were used: (“mild cognitive impairment” OR “MCI”) AND (“computerized cognitive training” OR “digital cognitive training” OR “tablet-based” OR “computer-based” OR “serious game” OR “gamified training”) AND (“randomized controlled trial” OR “RCT”).

No restrictions were placed on publication year, but only studies published in English were included. Reference lists of previous systematic reviews and relevant meta-analyses were also manually screened to identify additional eligible studies. The search process and study selection were independently performed by two reviewers, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (Munn et al., 2018).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies are randomized controlled trials involving adults aged 55 years or older diagnosed with MCI or cognitive decline. The experimental intervention was defined as a structured, task-based digital cognitive training program, delivered on computer or tablet platforms. Comparators included active or passive control conditions. The primary endpoint was global cognitive function, necessitating the reporting of quantitative data (e.g., Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (Nasreddine et al., 2005), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Tombaugh & McIntyre, 1992) scores) with extractable post-intervention metrics for meta-analysis. Exclusion criteria encompassed studies employing interventions primarily focused on physical exertion (e.g., exergames) or immersive virtual reality (e.g., using head-mounted displays), non-randomized designs, and those lacking requisite data.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data were independently extracted by two reviewers using a standardized form, including the following variables, Study characteristics, Participant information, Intervention characteristics, Outcome measures and so on (Smith et al., 2011). When data were incomplete, corresponding authors were contacted for clarification. If multiple cognitive outcomes were reported, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was prioritized over the MMSE (Siqueira et al., 2019). This preference is based on the MoCA’s superior sensitivity in detecting mild cognitive deficits and executive dysfunction compared to the MMSE, which is prone to ceiling effects in MCI populations (Nasreddine et al., 2005). However, to ensure comprehensive coverage, studies utilizing other validated batteries (e.g., RBANS, S-NAB) were also included and analyzed.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two reviewers using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2.0) (Ma et al., 2020). The assessment covered key domains, including the randomization process, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. Each study was judged to be at ‘low risk’, of ‘some concerns’, or at ‘high risk’ of bias for each domain. Any discrepancies between the reviewers’ independent assessments were resolved through discussion to reach a consensus. A visual summary of the ratings was subsequently created with the ggplot2 package in R to enhance transparency.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.5) with the meta and metafor packages (Viechtbauer, 2010). For each study, standardized mean differences (SMDs; Hedges’ g) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to quantify the between-group effect on global cognitive outcomes (Goulet-Pelletier & Cousineau, 2018). Both baseline and post-intervention means and standard deviations were extracted from each trial. For studies with multi-arm designs sharing a single group, the sample size of the shared group was divided evenly among the comparisons to prevent double-counting and avoid unit-of-analysis errors, in accordance with Cochrane guidelines.

Specifically, the effect size for each study was estimated as the difference in pre–post change between the intervention and control groups, standardized by the pooled standard deviation. This approach minimizes potential bias due to baseline imbalance across studies while maintaining comparability of outcome measures. When necessary, correlations between pre- and post-test scores were assumed to be moderate (r = 0.5) for variance estimation, consistent with established meta-analytic conventions in cognitive training research (Traut et al., 2021). The standard deviation of the change scores (SDchange) was calculated using the following formula:

To assess the impact of this assumption on the overall results, sensitivity analyses were performed using conservative (r = 0.3) and liberal (r = 0.7) correlation coefficients.

A random-effects model was applied using the restricted maximum-likelihood (REML) estimator to account for between-study heterogeneity, with Hartung–Knapp adjustments to provide more conservative confidence intervals (Langan et al., 2019). Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic (representing the proportion of total variance due to between-study variability) and tested using Cochran’s Q statistic (p < 0.10 indicating significant heterogeneity) (Jackson et al., 2012).

Pre-specified analyses were conducted to examine potential moderators, including the type of cognitive scale and the degree of gamification. To assess the robustness of the overall estimates, we performed sensitivity analyses using the leave-one-out method (Iooss & Lemaítre, 2015). Potential publication bias was evaluated by visually inspecting funnel plots and applying Egger’s regression test alongside the trim-and-fill procedure (Lin & Chu, 2018). Furthermore, we used the influence function from the metafor package to identify any studies that disproportionately influenced the pooled results (Viechtbauer, 2010). All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

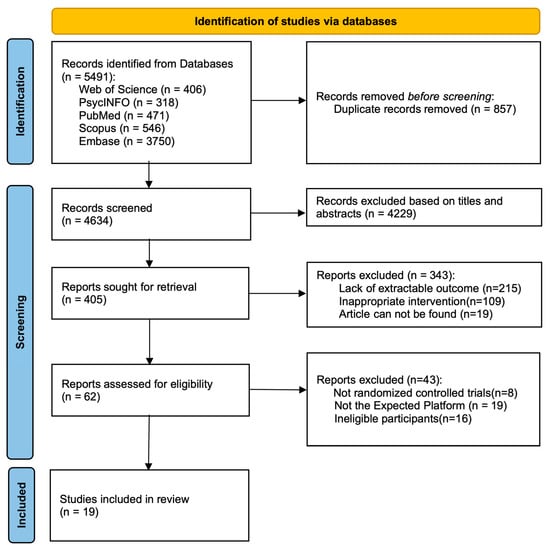

A systematic database search yielded 5491 records. After the removal of 857 duplicates, 4634 records were screened by title and abstract, leading to the exclusion of 4229. Of the 405 reports sought for full-text retrieval, 343 were excluded due to lack of extractable outcomes (n = 215), inappropriate intervention (n = 109), or unavailability (n = 19). Subsequent eligibility assessment of the remaining 62 reports excluded 41 for not being RCTs (n = 8), an ineligible platform (n = 19), or ineligible participants (n = 16). Ultimately, 19 studies were included in the systematic review. The selection process is summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram. Adapted from (Page et al., 2021) (PRISMA 2020 statement).

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 outlines the key characteristics of the 19 included studies. Data extractability was confirmed for all 19 studies, comprising complete means and standard deviations at baseline and post-intervention. Consequently, the quantitative synthesis included the full set of 19 RCTs, which yielded 20 independent comparisons due to the multi-arm design of (Bernini et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review.

The pooled sample comprised 1031 older adults, distributed across 505 in intervention groups and 526 in control groups. Participants were clinically diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or MCI associated with specific neurodegenerative or clinical conditions (classified as “Mixed” populations).

Intervention delivery relied on digital platforms, specifically personal computers (12 comparisons) and tablets (8 comparisons). Training protocols varied in intensity. As detailed in the revised Table 1, intervention durations ranged from 3 to 24 weeks, with training frequencies spanning from 1 to 5 sessions per week. To better characterize the intervention dosage, Table 1 has been updated to include session lengths, which typically ranged from 30 to 60 min.

In terms of gamification strategies, the interventions were categorized as low-gamified (n = 4), medium-gamified (n = 9), or high-gamified (n = 7), depending on the extent of game mechanics utilized. Global cognitive outcomes were assessed primarily via the MoCA (n = 11 comparisons) and MMSE (n = 6 comparisons), with the remaining 3 comparisons employing other standardized neuropsychological batteries.

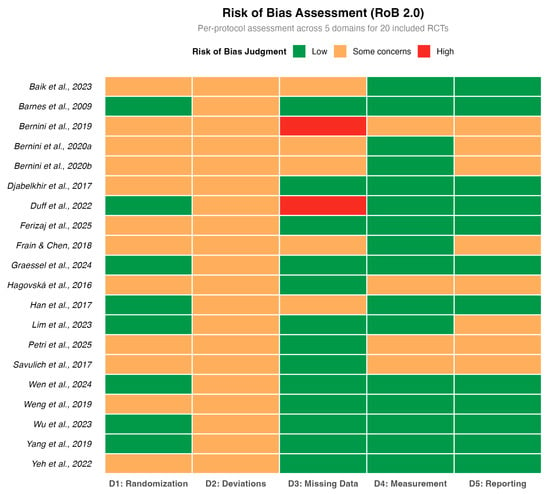

3.3. Methodological Quality

The methodological quality assessment was rigorously re-evaluated using the RoB 2.0 tool (Eldridge et al., 2016), as detailed in Figure 2. While the randomization process (Domain 1) was generally well-conducted, the assessment revealed a more nuanced landscape regarding other biases. Most notably, two studies (Bernini et al., 2019; Duff et al., 2022) were judged to be at ‘High Risk’ of bias in Domain 3 (Missing Outcome Data) due to substantial attrition rates without adequate statistical correction. Furthermore, the majority of studies were rated as having ‘Some Concerns’ in Domain 2 (Deviations from intended interventions), reflecting the inherent challenge of blinding participants in open-label behavioral interventions.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality assessment (Cochrane RoB 2.0). The included studies are: (Barnes et al., 2009; Hagovská & Olekszyová, 2016; Savulich et al., 2017; Djabelkhir et al., 2017; Han et al., 2017; Frain & Chen, 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2019; Weng et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2021; Yeh et al., 2022; Duff et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Baik et al., 2024; Graessel et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2024; Petri et al., 2025; Ferizaj et al., 2025).

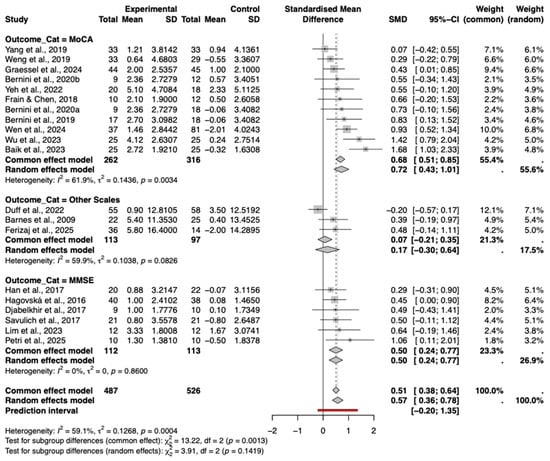

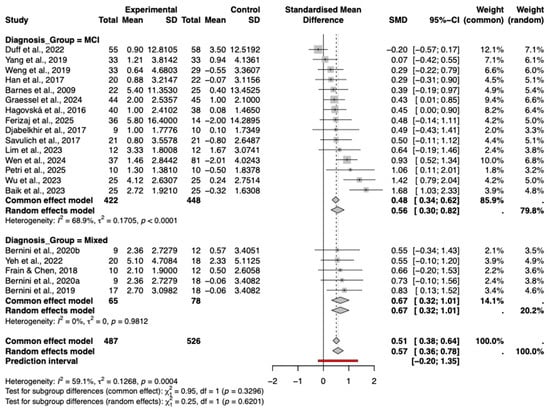

3.4. Overall Meta-Analysis

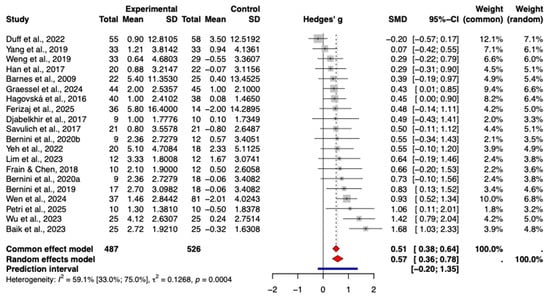

Based on the random-effects meta-analysis, task-based CCT delivered via tablets and computers demonstrated a statistically significant beneficial effect on global cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment (Hedges’ g = 0.57, 95% CI [0.36, 0.78], p < 0.0001) (Figure 3). The extent of heterogeneity across the included studies was moderate to high (I2 = 59.1%). A 95% prediction interval of −0.20 to 1.35 implies that while a positive effect is possible, its magnitude in future applications remains uncertain.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the pooled effect of CCT on global cognition.The included studies are: (Barnes et al., 2009; Hagovská & Olekszyová, 2016; Savulich et al., 2017; Djabelkhir et al., 2017; Han et al., 2017; Frain & Chen, 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2019; Weng et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2021; Yeh et al., 2022; Duff et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Baik et al., 2024; Graessel et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2024; Petri et al., 2025; Ferizaj et al., 2025).

3.5. Heterogeneity and Moderator Analysis

Given the substantial heterogeneity observed in the main analysis (I2 = 69.0%) and the wide prediction interval, we conducted influence diagnostics and moderator analyses to investigate potential sources of variability.

Influence diagnostics using the influence function identified two studies, (Baik et al., 2024) and (Wu et al., 2023), as potential outliers due to their exceptionally large effect sizes (SMD > 1.4). Sensitivity analysis excluding these two studies reduced the heterogeneity, although the overall positive effect of the intervention remained statistically significant.

To further explore the sources of heterogeneity, meta-regression analyses were performed on continuous moderators. The results indicated no significant linear relationship between the effect size and intervention duration (weeks) (p > 0.05) or training frequency (p > 0.05). Similarly, a subgroup analysis comparing intervention settings (Home-based vs. Center-based) revealed no statistically significant difference in efficacy (p > 0.05).

However, a critical source of heterogeneity was identified in the outcome assessment tools. As detailed in Section 3.8.1, the subgroup of studies using the MMSE demonstrated zero heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), whereas substantial heterogeneity persisted in the MoCA subgroup. This suggests that the variability in results is partly methodological, driven by the sensitivity or domain coverage of the specific cognitive scales used.

To explore the influence of training dosage on the results, meta-regression analyses were performed. We found no significant linear relationship between the intervention effect and intervention duration (weeks) (p = 0.38), suggesting that longer training periods do not automatically guarantee superior cognitive outcomes within the ranges studied.

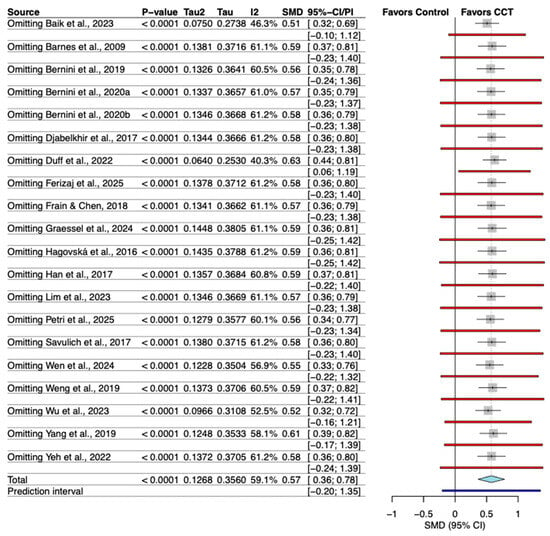

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis demonstrated the robustness of the pooled result. The omission of any individual study led to only negligible changes in the overall effect size (Hedges’ g), which remained statistically significant throughout all analyses (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of the effect of individual study omission. The included studies are: (Barnes et al., 2009; Hagovská & Olekszyová, 2016; Savulich et al., 2017; Djabelkhir et al., 2017; Han et al., 2017; Frain & Chen, 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2019; Weng et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2021; Yeh et al., 2022; Duff et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Baik et al., 2024; Graessel et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2024; Petri et al., 2025; Ferizaj et al., 2025).

Given the imputation of the correlation coefficient for change scores, we performed sensitivity analyses varying r from 0.3 to 0.7. The pooled effect size remained statistically significant in all scenarios: for r = 0.3 (SMD = 0.48, 95% CI [0.30, 0.66]), for r = 0.5 (SMD = 0.57, 95% CI [0.36, 0.78]), and for r = 0.7 (SMD = 0.74, 95% CI [0.48, 1.00]). Although higher correlations increased the estimated effect size and heterogeneity, the positive impact of CCT on cognitive function remained robust.

To assess the impact of study quality, a sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding studies flagged with ‘High Risk’ of bias in any domain (Baik et al., 2024; Bernini et al., 2019). The pooled effect size remained statistically significant (Hedges’ g = 0.62, 95% CI [0.42, 0.81]). Notably, the heterogeneity (I2) decreased to 42.9%, suggesting that the excluded high-risk studies contributed to the variability. This confirms that the observed benefit of CCT is robust and potentially underestimated when biased studies are included.

To verify whether the results were driven by specific clinical subtypes, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding studies on MCI associated with specific medical conditions (Parkinson’s disease, HIV, Stroke). The remaining 15 studies on general/amnestic MCI yielded a pooled Hedges’ g of 0.56 (95% CI [0.30, 0.82], p < 0.001), which is nearly identical to the overall effect (g = 0.57). This indicates that the positive intervention effect is robust across MCI subtypes.

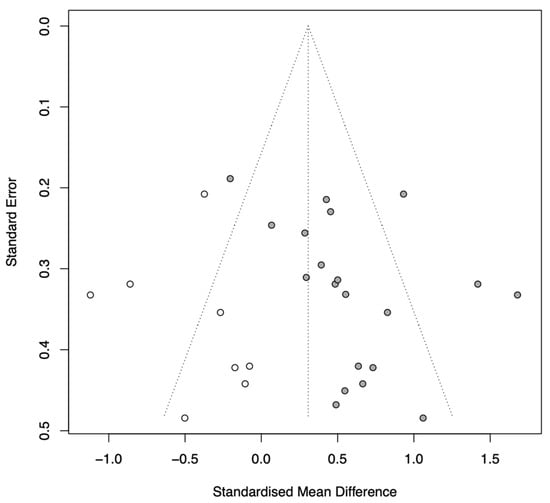

3.7. Publication Bias and Influence Diagnostics

Visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested potential asymmetry. Quantitative analysis using Egger’s regression test yielded a p-value of 0.064, indicating a trend toward publication bias. Furthermore, the trim-and-fill method identified asymmetry and imputed 8 potential missing studies. The adjusted pooled effect size using the random-effects model was Hedges’ g = 0.31 (95% CI [0.08, 0.54], p = 0.010). This analysis suggests that while publication bias may have inflated the initial estimate (g = 0.57), the positive effect of CCT remains statistically significant even after adjustment for potential missing negative results (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Funnel plot with trim-and-fill adjustment.

3.8. Subgroup Analyses

3.8.1. Cognitive Scale Type

A subgroup analysis was conducted based on the type of cognitive assessment tool used. The results showed varying effect sizes across different instruments (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of the subgroup analysis by cognitive assessment scale type. The included studies are: (Barnes et al., 2009; Hagovská & Olekszyová, 2016; Savulich et al., 2017; Djabelkhir et al., 2017; Han et al., 2017; Frain & Chen, 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2019; Weng et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2021; Yeh et al., 2022; Duff et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Baik et al., 2024; Graessel et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2024; Petri et al., 2025; Ferizaj et al., 2025).

The MoCA subgroup demonstrated a significant and relatively large pooled effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.72, 95% CI [0.43, 1.01]), albeit with considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 61.9%). In stark contrast, the MMSE subgroup showed a statistically significant positive effect (g = 0.50, 95% CI [0.24, 0.77]) with a complete absence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 =0%, p = 0.86). This indicates that when assessed via MMSE, the intervention effects are highly consistent across studies, whereas MoCA scores may be more sensitive to variations in study design or population characteristics.

The subgroup utilizing other scales (e.g., RBANS, S-NAB) indicated a smaller, non-significant positive effect (g = 0.17, 95% CI [−0.30, 0.64]). The test for subgroup differences was not statistically significant (p = 0.14), suggesting that while magnitude varies, the direction of effect is generally positive across instruments.

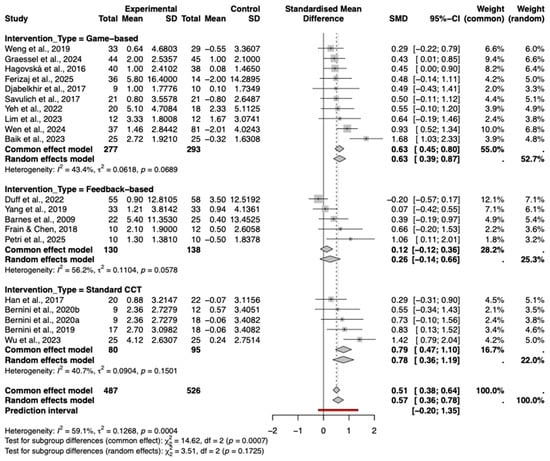

3.8.2. Types of Intervention

A subgroup analysis was performed to compare the effects of different intervention types, including game-based, feedback-based, and standard computerized cognitive training. As shown in the forest plot (Figure 7), varying degrees of efficacy were observed.

Figure 7.

Subgroup Analysis by type of cognitive intervention. The included studies are: (Barnes et al., 2009; Hagovská & Olekszyová, 2016; Savulich et al., 2017; Djabelkhir et al., 2017; Han et al., 2017; Frain & Chen, 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2019; Weng et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2021; Yeh et al., 2022; Duff et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Baik et al., 2024; Graessel et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2024; Petri et al., 2025; Ferizaj et al., 2025).

Standard computerized cognitive training (Standard CCT) demonstrated the largest pooled effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.78, 95% CI [0.36, 1.19]), followed closely by game-based interventions (g = 0.63, 95% CI [0.39, 0.87]), both of which were statistically significant. In contrast, feedback-based interventions showed a smaller, non-significant effect (g = 0.26, 95% CI [−0.14, 0.66]).

The test for subgroup differences was not statistically significant (p = 0.17), indicating that while numerical differences exist, there is currently no statistical evidence to suggest that one specific intervention type is definitively superior to the others.

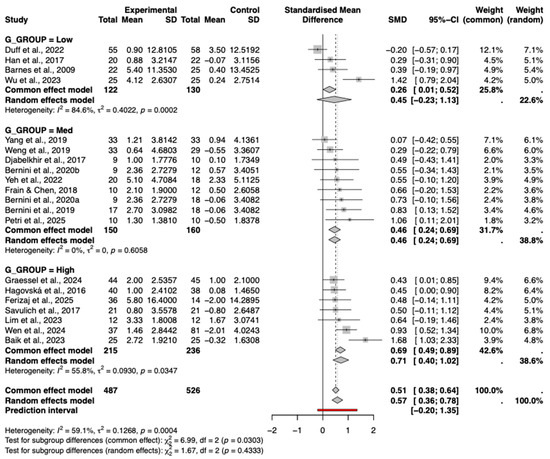

3.8.3. Degree of Gamification

A subgroup analysis was conducted to examine the impact of the degree of gamification on intervention efficacy. As shown in the forest plot (Figure 8), interventions with a high degree of gamification yielded a significant pooled effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.71, 95% CI [0.10, 1.02]), while those with a medium degree also showed a significant effect (g = 0.46, 95% CI [0.24, 0.69]).

Figure 8.

Subgroup Analysis by Gamification Degree. The included studies are: (Barnes et al., 2009; Hagovská & Olekszyová, 2016; Savulich et al., 2017; Djabelkhir et al., 2017; Han et al., 2017; Frain & Chen, 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2019; Weng et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2021; Yeh et al., 2022; Duff et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Baik et al., 2024; Graessel et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2024; Petri et al., 2025; Ferizaj et al., 2025).

In contrast, interventions with a low degree of gamification demonstrated a small, moderate effect (g = 0.45, 95% CI [−0.23, 1.13]). Although a trend of increasing effect sizes with higher degrees of gamification was observed, the test for subgroup differences was not statistically significant (p = 0.43), indicating that the variation in effects across gamification levels was not significant. Furthermore, meta-regression using the continuous gamification score did not reveal a significant linear relationship (p = 0.39), confirming that this trend should be interpreted with caution.

3.8.4. Types of Diagnosis

Forest plot presents the results of subgroup analysis stratified by diagnosis type (Figure 9). The analysis indicates that studies involving participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) demonstrated a significant and moderate pooled effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.56, 95% CI [0.30, 0.82]), with moderate heterogeneity observed within this subgroup (I2 = 68.9%, p < 0.0001). Studies involving mixed diagnostic populations (e.g., MCI with Parkinson’s disease or stroke) also showed a significant positive effect (g = 0.67, 95% CI [0.32, 1.01]), notably with zero heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), suggesting highly consistent outcomes within this specific subset of studies.

Figure 9.

Subgroup analysis by diagnosis type (MCI vs. Mixed). The included studies are: (Barnes et al., 2009; Hagovská & Olekszyová, 2016; Savulich et al., 2017; Djabelkhir et al., 2017; Han et al., 2017; Frain & Chen, 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2019; Weng et al., 2019; Bernini et al., 2021; Yeh et al., 2022; Duff et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Baik et al., 2024; Graessel et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2024; Petri et al., 2025; Ferizaj et al., 2025).

The test for subgroup differences was not statistically significant (p = 0.62), indicating that the intervention effects did not differ significantly between the MCI and mixed diagnosis subgroups. These findings suggest that the cognitive intervention produced comparable benefits across the different diagnostic groups included in the analysis.

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy of task-based computerized cognitive training (CCT) delivered via tablet and computer platforms for improving global cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Based on a synthesis of 21 randomized controlled trials, our findings indicate that CCT yields a statistically significant, moderate positive effect on global cognitive function (Hedges’ g = 0.55) compared to control conditions. Subgroup analyses demonstrated that this effect was consistent across different types of cognitive assessment tools, intervention designs, and participant diagnostic categories. Although not statistically significant, a trend was observed suggesting that interventions with a higher degree of gamification might be associated with larger effect sizes. The overall results were robust to sensitivity analysis, and no substantial publication bias was detected.

4.1. Interpretation of Results

The pooled effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.55) indicates a moderate beneficial effect of tablet-and computer-based CCT, which aligns with a growing body of evidence supporting digital cognitive interventions for MCI (Li et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2019). The clinical relevance of this finding is substantial, given the progressive nature of MCI and the need for safe, scalable, and accessible interventions (Sabbagh et al., 2020). The utilization of tablets and computers likely facilitates this accessibility, enabling decentralized delivery, flexible scheduling, and potentially enhanced adherence, all of which are crucial for long-term cognitive maintenance (Dasgupta et al., 2016).

A primary objective of this study was to investigate the role of gamification. Although the test for subgroup differences was not statistically significant, a compelling trend emerged: interventions with high and medium degrees of gamification yielded effect sizes of g = 0.71 and g = 0.57, respectively, whereas low-gamification interventions demonstrated a negligible effect (g = 0.05). While numerically distinct, the lack of statistical significance in subgroup differences suggests that gamification is likely a contributory, rather than solely determinative, factor in intervention efficacy. This pattern provides tentative evidence that incorporating game-like elements may enhance the efficacy of CCT, potentially by boosting intrinsic motivation, engagement, and emotional reward (Oldrati et al., 2020). However, the wide confidence interval for the low-gamification subgroup and the overall non-significant result indicate that this finding remains preliminary. Future studies specifically designed to directly compare gamified versus non-gamified protocols are warranted to confirm this potential added benefit.

Further subgroup analyses reinforced the robustness of the primary finding. The positive effect of CCT remained consistent across different intervention designs and samples with varying diagnostic compositions. Notably, the effect size was slightly larger when measured by the MoCA (g = 0.68) compared to the MMSE (g = 0.49). This is likely attributable to the MoCA’s superior sensitivity in assessing executive functions and detecting subtle cognitive changes, domains often targeted by CCT programs (Julayanont et al., 2012).

The considerable heterogeneity observed is a common feature in meta-analyses of complex interventions and likely originates from variations in training protocols, software platforms, and session parameters (Petropoulou et al., 2021; Terhorst et al., 2024). Furthermore, the wide 95% prediction interval suggests that the effect in a future application could range from negligible to large. This uncertainty underscores the importance of personalizing interventions and identifying patient-level moderators that may predict individual response.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to specifically isolate and evaluate the effect of task-based CCT delivered exclusively on tablet and computer platforms for individuals with MCI, and to systematically explore the degree of gamification as a potential effect modifier. This study adhered to rigorous methodological standards, including a comprehensive literature search, duplicate study selection and data extraction processes, utilization of the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool, and pre-specified analyses employing robust statistical methods.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the number of included studies, particularly within certain subgroups (e.g., low-gamification), was limited, which constrained the statistical power of the subgroup analyses. Second, the substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity, although accounted for by a random-effects model, complicates the interpretation of a single pooled effect estimate. Third, regarding methodological quality, a significant proportion of studies were assessed as having ‘Some Concerns,’ primarily due to deviations from intended interventions. This reflects the inherent challenge of blinding in behavioral trials. Furthermore, factors specific to digital interventions, such as digital fatigue, device familiarity, and dropout rates (which led to ‘High Risk’ ratings in two studies), represent potential sources of bias that standard analyses may not fully mitigate. Fourth, the categorization of gamification degree, while based on a rubric, remains constrained by the absence of a universally standardized scale for quantifying gamification. Fifth, a notable limitation is the absence of reported negative effects or adverse events (e.g., eye strain, frustration) in the included studies. This lack of reporting may reflect a ‘file drawer’ problem regarding safety data in behavioral interventions, potentially leading to an underestimation of the burden on participants. Finally, the analysis focused solely on global cognition as the primary outcome; the effects on specific cognitive domains remain important avenues for future research.

4.3. Implications for Clinical Practice and Future Research

The findings provide robust evidence supporting the integration of tablet- and computer-based CCT as a feasible and effective complementary intervention into comprehensive management strategies for individuals with MCI.

The observed trend suggesting enhanced efficacy with higher degrees of gamification offers a practical insight for intervention designers. Incorporating game-like elements may represent a promising strategy for maximizing user engagement and adherence, which are critical for achieving sustained cognitive benefits. However, this approach should be balanced with usability considerations, particularly for older adults with varying levels of digital literacy.

Future research should prioritize several key areas: (1) conducting large-scale RCTs that directly compare gamified versus non-gamified CCT to definitively establish its additive value; (2) investigating the active components and optimal dosing parameters of effective training; (3) employing longer follow-up periods to assess the long-term sustainability of cognitive benefits and transfer to daily functioning; and (4) exploring personalized intervention strategies based on individual patient characteristics.

5. Conclusions

This meta-analysis demonstrates that computerized cognitive training administered through tablet and computer platforms effectively enhances global cognition in patients with mild cognitive impairment. While these widely accessible technologies provide a practical basis for intervention implementation, our findings underscore the complementary role of gamification in augmenting treatment outcomes. The consistent trend of increasing effect sizes with higher gamification levels indicates that well-designed game elements may significantly potentiate intervention efficacy, potentially through enhanced engagement and motivation. Future development should focus not only on leveraging the accessibility of these platforms but, more importantly, on systematically integrating and optimizing gamification principles to maximize both adherence and cognitive benefits.

Future development should focus not only on leveraging the accessibility of these platforms but, more importantly, on systematically integrating and optimizing gamification principles. However, it is important to note that unexplained clinical variability remains, which may be partly attributable to the use of broad screening instruments (e.g., MoCA) rather than specific neuropsychological batteries. To clarify these diverse effects and minimize methodological biases, future research must adopt standardized reporting protocols and rigorous study designs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/bs16010040/s1, Table S1: Reconciliation of included studies: Systematic review versus meta-analysis data availability; Table S2: Individual study results (Pre/Post data), effect sizes, and weights.

Author Contributions

M.J. was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, and language polishing of the manuscript, with a focus on enhancing the clarity and coherence of the text. Z.D. contributed most prominently to conceptualization, methodology, statistical analysis, and manuscript drafting, providing leadership throughout the study. C.H. was primarily responsible for data extraction, literature search, and validation of included studies. Y.X. contributed to data analysis, visualization, and reviewing the manuscript draft. B.Z. and H.C. provided overall supervision, funding support, methodological guidance, and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Science and Technology Innovation 2030-“Brain Science and Brain-like Research” Major Project (No. 2022ZD0210800 to H.C.); the Emerging Enhancement Technology under Perspective of Humanistic Philosophy, supported by the National Office for Philosophy and Social Science (No. 20&ZD045 to H.C.); and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32171046 and No. 32471093 to H.C.). The study was also supported by the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission (No. WX23A99 and No. WX21D62 to B.Z.) and the 2024 Wuhan Natural Science Foundation Exploration Plan Municipal Medical Institutions Clinical Research Key Project (No. 2024020801020405 to B.Z.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of previously published research and does not involve direct contact with human subjects or primary data collection.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. As a systematic review and meta-analysis, this study utilized only data from already published articles where informed consent was obtained by the original investigators.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as it is a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing literature. The data presented in this study, including the extraction sheets and the R code used for meta-analysis, are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Anderson, N. D. (2019). State of the science on mild cognitive impairment (MCI). CNS Spectrums, 24(1), 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, J. S., Min, J. H., Ko, S.-H., Yun, M. S., Lee, B., Kang, N. Y., Kim, B., Lee, H., & Shin, Y.-I. (2024). Effects of home-based computerized cognitive training in community-dwelling adults with mild cognitive impairment. IEEE Journal of Translational Engineering in Health and Medicine, 12, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, D. E., Yaffe, K., Belfor, N., Jagust, W. J., DeCarli, C., Reed, B. R., & Kramer, J. H. (2009). Computer-based cognitive training for mild cognitive impairment: Results from a pilot randomized, controlled trial. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 23(3), 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernini, S., Alloni, A., Panzarasa, S., Picascia, M., Quaglini, S., Tassorelli, C., & Sinforiani, E. (2019). A computer-based cognitive training in mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation, 44(4), 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernini, S., Panzarasa, S., Barbieri, M., Sinforiani, E., Quaglini, S., Tassorelli, C., & Bottiroli, S. (2021). A double-blind randomized controlled trial of the efficacy of cognitive training delivered using two different methods in mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: Preliminary report of benefits associated with the use of a computerized tool. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(6), 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burford, S., & Park, S. (2014). The impact of mobile tablet devices on human information behaviour. Journal of Documentation, 70(4), 622–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M., McCreedy, E., Nelson, V. A., Desai, P., Ratner, E., Fink, H. A., Hemmy, L. S., McCarten, J. R., Barclay, T. R., Brasure, M., & Davila, H. (2018). Does cognitive training prevent cognitive decline? A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 168(1), 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A. T., Ip, R. T., Tran, J. Y., Chan, J. Y., & Tsoi, K. K. (2024). Computerized cognitive training for memory functions in mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digital Medicine, 7(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, F., Gonçalves, D., & Abreu, A. M. (2025). The impact of game-based interventions on adult cognition: A systematic review. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 41(19), 12479–12514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, D., Chaudhry, B., Koh, E., & Chawla, N. V. (2016). A survey of tablet applications for promoting successful aging in older adults. IEEE Access: Practical Innovations, Open Solutions, 4, 9005–9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCarli, C. (2003). Mild cognitive impairment: Prevalence, prognosis, aetiology, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 2(1), 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paiva Azevedo, J., Delaney, H., Epperson, M., Jbeili, C., Jensen, S., McGrail, C., Weaver, H., Baglione, A., & Barnes, L. E. (2019, April 26). Gamification of ehealth interventions to increase user engagement and reduce attrition. 2019 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS) (pp. 1–5), Charlottesville, VA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djabelkhir, L., Wu, Y.-H., Vidal, J.-S., Cristancho-Lacroix, V., Marlats, F., Lenoir, H., Carno, A., & Rigaud, A.-S. (2017). Computerized cognitive stimulation and engagement programs in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: Comparing feasibility, acceptability, and cognitive and psychosocial effects. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 12, 1967–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, K., Ying, J., Suhrie, K. R., Dalley, B. C. A., Atkinson, T. J., Porter, S. M., Dixon, A. M., Hammers, D. B., & Wolinsky, F. D. (2022). Computerized cognitive training in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 35(3), 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, S. M., Harrison, S. L., Laver, K., Whitehead, C., & Crotty, M. (2018). An overview of systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(3), 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S., Campbell, M., Campbell, M., Dahota, A., Giraudeau, B., Higgins, J., Reeves, B., & Siegfried, N. (2016). Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2.0): Additional considerations for cluster-randomized trials. Cochrane Methods Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ferizaj, D., Stamm, O., Perotti, L., Martin, E. M., Finke, K., Finke, C., Strobach, T., & Heimann-Steinert, A. (2025). Preliminary effects of mobile computerized cognitive training in adults with mild cognitive impairment: Interim analysis of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frain, J. A., & Chen, L. (2018). Examining the effectiveness of a cognitive intervention to improve cognitive function in a population of older adults living with HIV: A pilot study. Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease, 5(1), 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S., Zhu, Z., Wu, B., & McConnell, E. S. (2018). Technology-based cognitive training and rehabilitation interventions for individuals with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet-Pelletier, J.-C., & Cousineau, D. (2018). A review of effect sizes and their confidence intervals, Part I: The Cohen’sd family. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 14(4), 242–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graessel, E., Jank, M., Scheerbaum, P., Scheuermann, J.-S., & Pendergrass, A. (2024). Individualised computerised cognitive training (iCCT) for community-dwelling people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI): Results on cognition in the 6-month intervention period of a randomised controlled trial (MCI-CCT study). BMC Medicine, 22(1), 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagovská, M., & Olekszyová, Z. (2016). Impact of the combination of cognitive and balance training on gait, fear and risk of falling and quality of life in seniors with mild cognitive impairment. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 16(9), 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. W., Son, K. L., Byun, H. J., Ko, J. W., Kim, K., Hong, J. W., Kim, T. H., & Kim, K. W. (2017). Efficacy of the ubiquitous spaced retrieval-based memory advancement and rehabilitation training (USMART) program among patients with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled crossover trial. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 9(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P. D., McGurk, S. R., Mahncke, H., & Wykes, T. (2018). Controversies in computerized cognitive training. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(11), 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N. T., Mowszowski, L., Naismith, S. L., Chadwick, V. L., Valenzuela, M., & Lampit, A. (2017). Computerized cognitive training in older adults with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(4), 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M., Wu, X., Shu, X., Hu, H., Chen, Q., Peng, L., & Feng, H. (2021). Effects of computerised cognitive training on cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Neurology, 268(5), 1680–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iooss, B., & Lemaítre, P. (2015). A review on global sensitivity analysis methods. In Uncertainty management in simulation-optimization of complex systems: Algorithms and applications (pp. 101–122). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D., White, I. R., & Riley, R. D. (2012). Quantifying the impact of between-study heterogeneity in multivariate meta-analyses. Statistics in Medicine, 31(29), 3805–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Jonides, J., & Shah, P. (2011). Short-and long-term benefits of cognitive training. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(25), 10081–10086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julayanont, P., Phillips, N., Chertkow, H., & Nasreddine, Z. S. (2012). Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA): Concept and clinical review. In Cognitive screening instruments: A practical approach (pp. 111–151). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kueider, A. M., Parisi, J. M., Gross, A. L., & Rebok, G. W. (2012). Computerized cognitive training with older adults: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 7(7), e40588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langan, D., Higgins, J. P., Jackson, D., Bowden, J., Veroniki, A. A., Kontopantelis, E., Viechtbauer, W., & Simmonds, M. (2019). A comparison of heterogeneity variance estimators in simulated random-effects meta-analyses. Research Synthesis Methods, 10(1), 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Geng, J., Yang, R., Ge, Y., & Hesketh, T. (2022). Effectiveness of computerized cognitive training in delaying cognitive function decline in people with mild cognitive impairment: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(10), e38624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E. H., Kim, D.-S., Won, Y.-H., Park, S.-H., Seo, J.-H., Ko, M.-H., & Kim, G.-W. (2023). Effects of home based serious game training (Brain TalkTM) in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment: Randomized, a single-blind, controlled trial. Brain & Neurorehabilitation, 16(1), e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L., & Chu, H. (2018). Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. Journal of the International Biometric Society, 74(3), 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S., Saunders, R., Maier, M. A., & Lüttke, S. (2020). Gamification as an approach to improve resilience and reduce attrition in mobile mental health interventions: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 15(9), e0237220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumsden, J., Edwards, E. A., Lawrence, N. S., Coyle, D., & Munafò, M. R. (2016). Gamification of cognitive assessment and cognitive training: A systematic review of applications and efficacy. JMIR Serious Games, 4(2), e5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-L., Wang, Y.-Y., Yang, Z.-H., Huang, D., Weng, H., & Zeng, X.-T. (2020). Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Military Medical Research, 7(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., Bédirian, V., Charbonneau, S., Whitehead, V., Collin, I., Cummings, J. L., & Chertkow, H. (2005). The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldrati, V., Corti, C., Poggi, G., Borgatti, R., Urgesi, C., & Bardoni, A. (2020). Effectiveness of computerized cognitive training programs (CCTP) with game-like features in children with or without neuropsychological disorders: A meta-analytic investigation. Neuropsychology Review, 30(1), 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., & Chou, R. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H., & Ha, J. (2024). Effect of digital technology interventions for cognitive function improvement in mild cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research in Nursing & Health, 47(4), 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, M. C., Messinis, L., Patrikelis, P., Nasios, G., Dimitriou, N., Nousia, A., & Kosmidis, M. H. (2025). Feasibility and clinical effectiveness of computer-based cognitive rehabilitation in illiterate and low-educated individuals with mild cognitive impairment: Preliminary data. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 40(3), 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulou, M., Efthimiou, O., Ruecker, G., Schwarzer, G., Furukawa, T. A., Pompoli, A., Koek, H. L., Del Giovane, C., Rodondi, N., & Mavridis, D. (2021). A review of methods for addressing components of interventions in meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 16(2), e0246631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, M., Bryce, R., Albanese, E., Wimo, A., Ribeiro, W., & Ferri, C. P. (2013). The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 9(1), 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realdon, O., Rossetto, F., Nalin, M., Baroni, I., Cabinio, M., Fioravanti, R., Saibene, F., Alberoni, M., Mantovani, F., Romano, M., & Nemni, R. (2016). Technology-enhanced multi-domain at home continuum of care program with respect to usual care for people with cognitive impairment: The Ability-TelerehABILITation study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, M. N., Boada, M., Borson, S., Chilukuri, M., Doraiswamy, P., Dubois, B., Ingram, J., Iwata, A., Porsteinsson, A., Possin, K., & Rabinovici, G. D. (2020). Rationale for early diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) supported by emerging digital technologies. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease, 7(3), 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savulich, G., Piercy, T., Fox, C., Suckling, J., Rowe, J. B., O’Brien, J. T., & Sahakian, B. J. (2017). Cognitive training using a novel memory game on an iPad in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI). International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 20(8), 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, G. S., Hagemann, P. d. M., Coelho, D. de S., Santos, F. H. D., & Bertolucci, P. H. (2019). Can MoCA and MMSE be interchangeable cognitive screening tools? A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 59(6), e743–e763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, V., Devane, D., Begley, C. M., & Clarke, M. (2011). Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahami Monfared, A. A., Byrnes, M. J., White, L. A., & Zhang, Q. (2022). Alzheimer’s disease: Epidemiology and clinical progression. Neurology and Therapy, 11(2), 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhorst, Y., Kaiser, T., Brakemeier, E.-L., Moshe, I., Philippi, P., Cuijpers, P., Baumeister, H., & Sander, L. B. (2024). Heterogeneity of treatment effects in internet-and mobile-based interventions for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 7(7), e2423241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombaugh, T. N., & McIntyre, N. J. (1992). The mini-mental state examination: A comprehensive review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 40(9), 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traut, H. J., Guild, R. M., & Munakata, Y. (2021). Why does cognitive training yield inconsistent benefits? A meta-analysis of individual differences in baseline cognitive abilities and training outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 662139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeir, J. F., White, M. J., Johnson, D., Crombez, G., & Van Ryckeghem, D. M. (2020). The effects of gamification on computerized cognitive training: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Serious Games, 8(3), e18644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X., Song, S., Tian, H., Cui, H., Zhang, L., Sun, Y., Li, M., & Wang, Y. (2024). Intervention of computer-assisted cognitive training combined with occupational therapy in people with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 16, 1384318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W., Liang, J., Xue, J., Zhu, T., Jiang, Y., Wang, J., & Chen, S. (2019). The transfer effects of cognitive training on working memory among chinese older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Global status report on the public health response to dementia. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., He, Y., Liang, S., Liu, Z., Huang, J., Liu, W., Tao, J., Chen, L., Chan, C. C. H., & Lee, T. M. C. (2023). Effects of computerized cognitive training on structure-function coupling and topology of multiple brain networks in people with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 15(1), 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-L., Chu, H., Kao, C.-C., Chiu, H.-L., Tseng, I.-J., Tseng, P., & Chou, K.-R. (2019). Development and effectiveness of virtual interactive working memory training for older people with mild cognitive impairment: A single-blind randomised controlled trial. Age and Ageing, 48(4), 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-T., Chang, K.-C., Wu, C.-Y., Chen, C.-J., & Chuang, I.-C. (2022). Clinical efficacy of aerobic exercise combined with computer-based cognitive training in stroke: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 29(4), 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Huntley, J., Bhome, R., Holmes, B., Cahill, J., Gould, R. L., Wang, H., Yu, X., & Howard, R. (2019). Effect of computerised cognitive training on cognitive outcomes in mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 9(8), e027062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuschnegg, J., Ropele, S., Opriessnig, P., Schmidt, R., Russegger, S., Fellner, M., Leitner, M., Spat, S., Garcia, M. L., Strobl, B., & Ploder, K. (2025). The effect of tablet-based multimodal training on cognitive functioning in Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 20(8), e0329931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.