Long-Duration Vocational Education’s Effects on Individuals’ Vocational Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Job Satisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Study of the Effects of Vocational Education

2.2. Vocational Education and Vocational Identity

2.3. Vocational Education and Self-Efficacy

2.4. Vocational Education and Job Satisfaction

3. Research Hypotheses

4. Research Method

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Sample Collection

4.3. Variable’s Measurement

5. Results

5.1. Estimation Before Matching

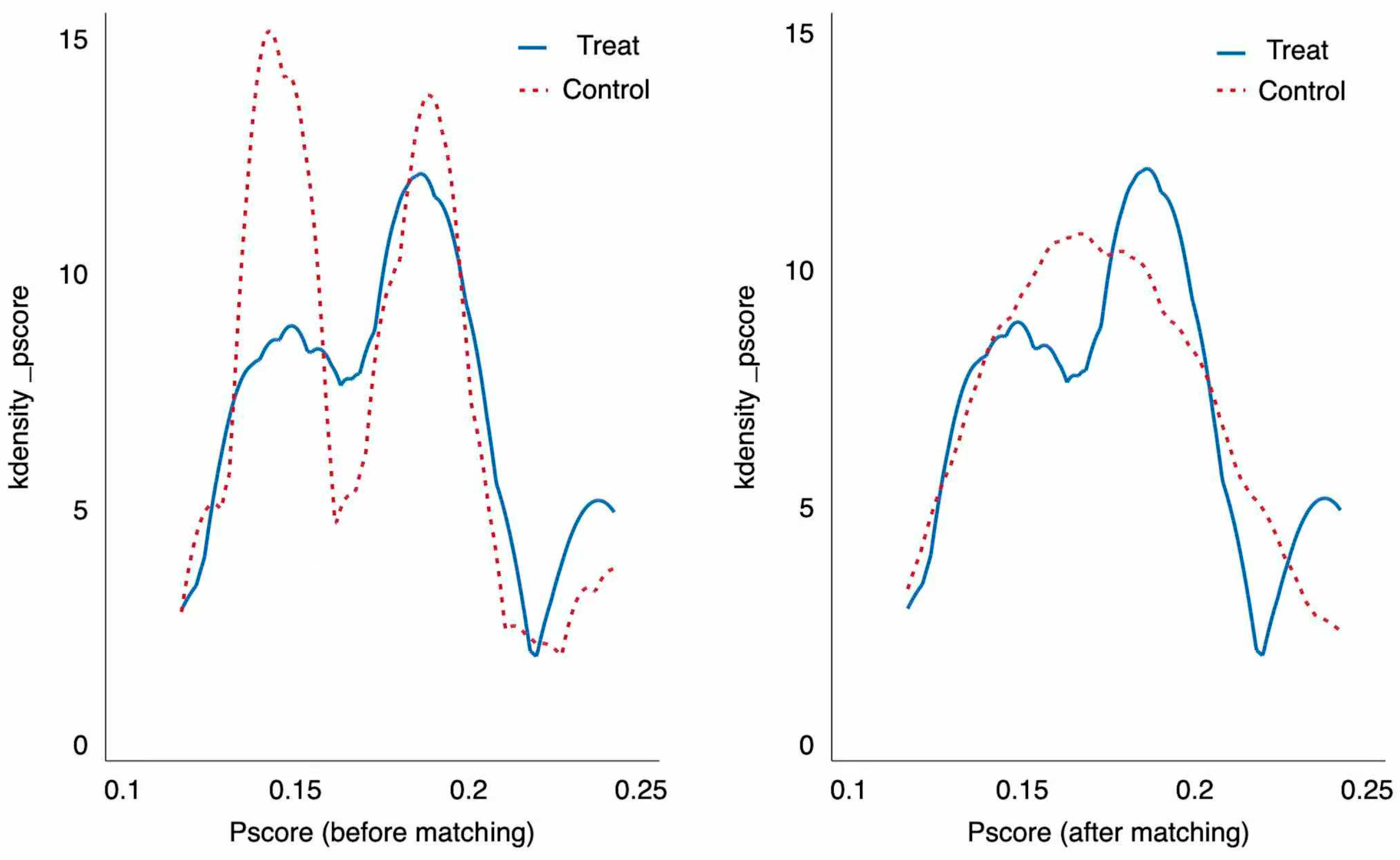

5.2. Propensity Score Estimation

5.3. Propensity Score Matching Analysis

5.4. Propensity Score Matching Results

5.5. Robustness Analysis

5.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

6. Conclusions and Discussions

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Discussion and Suggestions

6.3. Shortcomings and Prospects

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LDVE | Continuous and prolonged vocational education |

| VIVE | Vertically integrated vocational education |

| PSM | Propensity score matching |

| ATT | Average treatment effect of the treated |

References

- Allan, V., Ramagopalan, S. V., Mardekian, J., Jenkins, A., Li, X., Pan, X., & Luo, X. (2020). Propensity score matching and inverse probability of treatment weighting to address confounding by indication in comparative effectiveness research of oral anticoagulants. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, 9(9), 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (1991). Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 979–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L., & Epple, D. (1990). Learning curves in manufacturing. Science, 247(4945), 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P. C. (2011). Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharmaceutical Statistics, 10(2), 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, X., Xue, H., Zhang, Q., & Xu, W. (2023). Academic stereotype threat and engagement of higher vocational students: A moderated mediation model. Social Psychology of Education, 26(5), 1419–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battu, H., Belfield, C. R., & Sloane, P. J. (2000). How well can we measure graduate over-education and its effects? National Institute Economic Review, 171, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S. (1967). Human capital, A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. Revue Économique, 18(1), 132–133. [Google Scholar]

- Betz, N. E., & Hackett, G. (2006). Career self-efficacy theory: Back to the future. Journal of Career Assessment, 14(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, S. (2011). Vocational education: Purposes, traditions and prospects. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, S. (2014). The standing of vocational education: Sources of its societal esteem and implications for its enactment. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 66(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bils, M., & Klenow, P. J. (2000). Does schooling cause growth? American Economic Review, 90(5), 1160–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blossfeld, H. P., Kilpi-Jakonen, E., de Vilhena, D. V., & Buchholz, S. (Eds.). (2014). Adult learning in modern societies: An international comparison from a life-course perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Budría, S., & Telhado-Pereira, P. (2009). The contribution of vocational training to employment, job-related skills and productivity: Evidence from Madeira. International Journal of Training and Development, 13(1), 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1996). Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67(3), 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. (2014). Advanced econometrics and Stata applications. Higher Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q., Zhang, Q., Yu, F., & Hou, B. (2023). Investigating structural relationships between professional identity, learning engagement, academic self-efficacy, and university support: Evidence from tourism students in China. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B. Y., Park, H., Yang, E., Lee, S. K., Lee, Y., & Lee, S. M. (2012). Understanding career decision self-efficacy: A meta-analytic approach. Journal of Career Development, 39(5), 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Kean, P. E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehejia, R. H., & Wahba, S. (2002). Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Kappa Delta Pi. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. S. (1994). Understanding women’s educational and occupational choices: Applying the Eccles et al. model of achievement-related choices. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18(4), 585–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragher, E. B., Cass, M., & Cooper, C. L. (2005). The relationship between job satisfaction and health: A meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(2), 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, A. G., Bol, T., & Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2016). Vocational education and employment over the life cycle. Sociological Science, 3(21), 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A., Maier, T., Helmrich, R., & Zika, G. (2016). IT-Berufe und IT-Kompetenzen in der Industrie 4.0. BIBB-Fachbeiträge im internet. Available online: https://www.bibb.de/veroeffentlichungen/de/publication/show/7833 (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Hanushek, E. A., Schwerdt, G., Woessmann, L., & Zhang, L. (2017). General education, vocational education, and labor-market outcomes over the lifecycle. Journal of Human Resources, 52(1), 48–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. B. (2011). The motivation to work (Vol. 1). Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi, A. (2012). Vocational identity trajectories: Differences in personality and development of well–being. European Journal of Personality, 26(1), 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J., Daiger, D., & Power, P. (1980). My vocational situation: Description of an experimental diagnostic form for the selection of vocational assistance. Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J. L. (1973). Making vocational choices: A theory of careers. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hussien, F. M., & La, L. M. (2018). The determinants of student satisfaction with internship programs in the hospitality industry: A case study in the USA. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 17(4), 502–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Urban Education, 42(1), 82–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J. Q., & Shi, W. P. (2018). The policy logic, key issues, and rational practice of higher-to-undergraduate vocational education model. Vocational Education Forum, 6, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, A. B., & Lindahl, M. (2001). Education for growth: Why and for whom? Journal of Economic Literature, 39(4), 1101–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnen, E. S. (2013). The effects of career choice guidance on identity development. Education Research International, 2013(1), 901718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. W., & Mitchell, T. R. (2011). The story of why we stay: A review of job embeddedness. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8(1), 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2006). Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J., Schneegans, S., & Straza, T. (2021). UNESCO science report: The race against time for smarter development. Unesco Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. P. (2021). China’s skilled labor force exceeds 200 million. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021–03/19/content_5593804.ht (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Lin, K. S., & Wang, Y. N. (2016). The logic, concerns, and rational practice of the policy of secondary-to-undergraduate vocational education model. Journal of Hebei Normal University, 18(3), 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2(5), 360–580. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, J. L., Wanberg, C. R., & Zytowski, D. G. (1997). Development of a career task self-efficacy scale: The Kuder task self-efficacy scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50(3), 432–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, L. Y. Y., & Chan, C. K. Y. (2020). Adaptation and validation of the work experience questionnaire for investigating engineering students’ internship experience. Journal of Engineering Education, 109(5), 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, E., Aeschlimann, B., & Herzog, W. (2019). The gender gap in STEM fields: The impact of the gender stereotype of math and science on secondary students’ career aspirations. Frontiers in Education, 4, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A. M. (1974). A social learning theory of career decision making. American Institutes for Research in the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- MoE. (2023). Chinese vocational education development report (2021–2022). Available online: http://en.moe.gov.cn/documents/reports/202304/t20230403_1054100.html (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Nian, C. X. (2020). The ‘3+4’ integrated talent cultivation model: Implementation logic, practical contradictions, and promotion path based on data collected from Fujian province. Chinese Vocational and Technical Education, 3, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2021). Education at a glance 2021: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oje, O., Adesope, O., & Oje, A. V. (2021, July 26–29). Work in progress: The effects of hands-on learning on STEM students’ motivation and self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. 2021 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Access, online. [Google Scholar]

- Patrinos, H. A., & Psacharopoulos, G. (2020). Returns to education in developing countries. In S. Bradley, & C. Green (Eds.), The economics of education (pp. 53–64). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, L. W. (2004). Understanding the decision to enroll in graduate school: Sex and racial/ethnic group differences. The Journal of Higher Education, 75(5), 487–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Porfeli, E. J., & Lee, B. (2012). Career development during childhood and adolescence. New Directions for Youth Development, 2012(134), 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J. P. (2020). A practical guide to econometric methods for causal inference. Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rauner, F., & Maclean, R. (2008). Handbook of technical and vocational education and training research. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, B. L., LePine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1985). The bias due to incomplete matching. Biometrics, 41, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C. (2002a). Individual returns to vocational education and training qualifications: Their implications for lifelong learning. National Centre for Vocational Education Research. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C. (2002b). What are the longer-term outcomes for individuals completing vocational education and training qualifications? National Centre for Vocational Education Research. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M. L. (2013). Career construction theory and practice. Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, 2, 144–180. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B., & Konz, A. M. (1989). Strategic job analysis. Human Resource Management, 28(1), 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C., Li, X., Li, L., & Were, M. C. (2011). Sensitivity analysis for causal inference using inverse probability weighting. Biometrical Journal, 53(5), 822–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H. C., & Liu, Y. (2020). Becoming excellent student: A case study on the construction of the self-identity of well-performed students in higher vocational colleges. Journal of Research in Education and Ethnic Minorities, 31(1), 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y. L. (2022). An analysis of the difference in junior high school students’ willingness to enter secondary vocational schools—A survey of 21531 ninth graders in the three autonomous prefectures. Journal of Central China Normal University, 61(1), 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, D. (2004). Modern apprenticeships in the retail sector: Stresses, strains and support. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 56(4), 539–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Skorikov, V., & Vondracek, F. W. (2011). Vocational identity and career development. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 693–714). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Suddaby, R., Gendron, Y., & Lam, H. (2009). The organizational context of professionalism in accounting. Accounting Organizations and Society, 34(3–4), 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D. E. (1980). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 16(3), 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turda, E. S., Ferenț, P., Claudia, C., & Sebastian Turda, E. (2021). The impact of teacher’s feedback in increasing student’s self-efficacy and motivation. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Weerd, P. (2022). Being ‘the lowest’: Models of identity and deficit discourse in vocational education. Ethnography and Education, 18(2), 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, L. E., & García-Mora, B. (2005). Education and the determinants of job satisfaction. Education Economics, 13(4), 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, J. L., Ryan, A. M., & Oswald, F. L. (2008). The relationship between objective and perceived fit with academic major, adaptability, and major-related outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(3), 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelmann, R. (1996). Employment prospects and skill acquisition of apprenticeship-trained workers in Germany. ILR Review, 49(4), 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woessmann, L. (2019). Facing the life-cycle trade-off between vocational and general education in apprenticeship systems: An economics-of-education perspective. Journal for Educational Research Online, 11(1), 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. J. (2013). Career outcomes of STEM and non-STEM college graduates: Persistence in majored-field and influential factors in career choices. Research in Higher Education, 54, 349–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldin, A. L., Britner, S. L., & Pajares, F. (2008). A comparative study of the self-efficacy beliefs of successful men and women in mathematics, science, and technology careers. Journal of Research in Science Teaching: The Official Journal of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, 45(9), 1036–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 867 | 46.2 |

| Female | 1011 | 53.8 | |

| Family Background | Urban | 761 | 40.5 |

| Rural | 1117 | 59.5 | |

| Educational Level | Secondary vocational school | 387 | 20.6 |

| Vocational college | 1125 | 59.9 | |

| Vocational university | 366 | 19.5 | |

| Major | Engineering and manufacturing | 503 | 26.8 |

| Business | 704 | 37.5 | |

| Medicine and nursing | 314 | 16.7 | |

| IT | 357 | 19.0 |

| Variable | Treated | Control | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Vocational identity | 32.04 | 8.21 | 31.80 | 8.010 | 0.44 | 0.66 |

| Self-efficacy | 32.73 | 7.76 | 32.83 | 7.515 | 0.49 | 0.62 |

| Job satisfaction | 27.21 | 6.93 | 27.03 | 6.789 | −0.20 | 0.84 |

| Variable | β | SE | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.35 * | 0.16 | 0.61 |

| Gender | −0.13 | 0.69 | 0.80 |

| Family Background | −0.16 * | 0.69 | 0.75 |

| Major | −0.07 * | 0.03 | 0.88 |

| Log likelihood | −857.79 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.01 | ||

| LR Chi2 | 14.81 |

| Variable | Matching | Mean | SE | ASMD | % Bias | t-Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | Control | t | p > |t| | |||||

| Gender | Unmatched | 1.48 | 1.55 | −13.4 | 0.134 | 100 | −2.2 | 0.028 |

| Matched | 1.48 | 1.48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 | ||

| Family Background | Unmatched | 1.54 | 1.61 | −14.5 | 0.145 | 100 | −2.4 | 0.016 |

| Matched | 1.54 | 1.54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 | ||

| Major | Unmatched | 2.15 | 2.31 | −15.2 | 0.152 | 100 | −2.48 | 0.013 |

| Matched | 2.15 | 2.15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 | ||

| Variable | Matching Method | Treated | Control | ATT (%) | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vocational identity | K-NN matching with caliper (k = 3, caliper = 0.01) | 32.037 | 33.304 | −1.267 | 0.82 |

| K-NN matching (k = 2) | 32.037 | 32.230 | −0.193 | 0.29 | |

| Kernal matching | 32.037 | 31.718 | 0.319 | 0.64 | |

| MD matching | 32.037 | 31.787 | 0.249 | 0.14 | |

| Caliper matching (caliper = 0.05) | 32.037 | 32.158 | −0.121 | 0.21 | |

| Mean | 32.037 | 32.239 | −0.203 | - | |

| Self-efficacy | K-NN matching with caliper (k = 3, caliper = 0.01) | 32.732 | 33.216 | −0.484 | 0.34 |

| K-NN matching (k = 2) | 32.732 | 32.998 | −0.266 | 0.43 | |

| Kernal matching | 32.732 | 32.761 | −0.028 | 0.06 | |

| MD matching | 32.732 | 32.563 | 0.169 | 0.10 | |

| Caliper matching (caliper = 0.05) | 32.732 | 33.232 | −0.500 | 0.94 | |

| Mean | 32.732 | 32.954 | −0.222 | - | |

| Job satisfaction | K-NN matching with caliper (k = 3, caliper = 0.01) | 27.212 | 28.234 | −1.022 | 0.84 |

| K-NN matching (k = 2) | 27.212 | 27.333 | −0.121 | 0.22 | |

| Kernal matching | 27.212 | 26.959 | 0.252 | 0.60 | |

| MD matching | 27.212 | 27.628 | −0.415 | 0.34 | |

| Caliper matching (caliper = 0.05) | 27.212 | 27.296 | −0.084 | 0.18 | |

| Mean | 27.212 | 27.49 | −0.278 | - |

| Variable | ATT (%) | SE | Z-Value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vocational Identity | 0.266 | 0.517 | 0.52 | 0.606 |

| Self-efficacy | −0.133 | 0.489 | −0.27 | 0.785 |

| Job Satisfaction | 0.172 | 0.441 | 0.39 | 0.696 |

| Variable | Integration Type | n | Treated | Control | ATT (%) | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vocational identity | secondary-to-higher | 178 | 32.46 | 32.12 | 0.39 | 0.54 |

| higher-to-undergraduate | 147 | 31.53 | 31.73 | −0.209 | −0.27 | |

| Self-efficacy | secondary-to-higher | 178 | 32.9878 | 33.03 | −0.05 | −0.08 |

| higher-to-undergraduate | 147 | 32.44 | 32.73 | −0.29 | −0.41 | |

| Job satisfaction | secondary-to-higher | 178 | 27.58 | 27.29 | 0.29 | 0.53 |

| higher-to-undergraduate | 147 | 26.77 | 27.00 | 0.23 | −0.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, C. Long-Duration Vocational Education’s Effects on Individuals’ Vocational Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Job Satisfaction. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091161

Yan C. Long-Duration Vocational Education’s Effects on Individuals’ Vocational Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Job Satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091161

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Cailing. 2025. "Long-Duration Vocational Education’s Effects on Individuals’ Vocational Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Job Satisfaction" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091161

APA StyleYan, C. (2025). Long-Duration Vocational Education’s Effects on Individuals’ Vocational Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Job Satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091161