Abstract

Background: Gambling risk behaviour is an emerging problem among adolescents. This study investigated the role of psychological factors, school behaviours, and normative perceptions as correlates of gambling among 12–14-year-old students in Italy. Methods: The study included 1822 students from 29 secondary schools in two Italian Regions (Piedmont and Lazio) who participated in the baseline survey of the experimental controlled trial “GAPUnplugged”. Results: The prevalence of gambling in the last 30 days was 36.4%. The mean age was 13.1 years. Multilevel mixed-effect regression models identified high positive attitudes, high performance beliefs, low risk perceptions toward gambling, friends’ gambling, friends’ approval of gambling, and gambling with friends as independent correlates of adolescent gambling behaviour. Conclusions: It appears essential to design and implement preventive strategies addressing these factors among early adolescents in order to reduce gambling behaviours and their consequences in later ages.

1. Introduction

Gambling behaviour among adolescents is recognized as a public health problem (Armitage, 2021; Delfabbro et al., 2016). Gambling experiences among adolescents begin at an early age, and early gamblers have a higher risk of gambling-related consequences at later ages (Burge et al., 2006; Rahman et al., 2012). Over the years, gambling has become highly accessible, primarily due to the rise in online forms of gambling, such as the “freemium” video games and online sports betting (Andrie et al., 2019; Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones, 2021). Furthermore, loot boxes, i.e., an in-game reward system that can be purchased repeatedly with real money to obtain a random selection of virtual items, have become very common on mobile platforms, contributing to gambling behaviour among adolescents and youth (King & Delfabbro, 2018; Montiel et al., 2022; Rockloff et al., 2021).

Moreover, advertising plays a significant role in promoting the behaviour, as it portrays gambling as socially desirable, entertaining, and a source of “easy money” (McMullan & Miller, 2010; O’Loughlin & Blaszczynski, 2018; Sklar & Derevensky, 2011). As a consequence, adolescents often consider gambling a fun entertainment, a way to not become bored, a recreational activity, and finally, perceive it as risk-free (McGrane et al., 2023; Vegni et al., 2019).

Several factors have been identified as correlates of adolescent gambling. Among socio-demographic characteristics, male gender, being part of an immigrant family, and being the only child were associated with gambling in previous studies (Anagnostopoulos et al., 2017; Dickson et al., 2008; Frisone et al., 2020; Giralt et al., 2018; Pisarska & Ostaszewski, 2020; Sharman et al., 2019). Among psychological factors, attitudes, beliefs, expectancies, and risk perceptions played an important role (Botella-Guijarro et al., 2020; Delfabbro et al., 2006; Delfabbro et al., 2009a; Delfabbro & Thrupp, 2003; Derevensky & Gilbeau, 2015; Donati et al., 2013; Favieri et al., 2023; Griffiths & Wood, 2000; Hanss et al., 2014; Hurt et al., 2008; Pallesen et al., 2016). Moreover, problematic stressful situations, negative life events, depression or anxiety symptoms, negative mood and low self-esteem were also associated with engagement in gambling (Delfabbro et al., 2006; Nigro et al., 2017; Stefanovics et al., 2023), as well as maladaptive coping strategies, poor self-control, impulsiveness, high sensation-seeking and risky activity propensity (Bergevin et al., 2006; Dickson et al., 2008; Dowling et al., 2017; Kaltenegger et al., 2019; Reardon et al., 2019; Rizzo et al., 2023).

Similarly to other risk behaviours, social influences such as friends’ gambling and friends’ approval toward gambling were found to increase the probability of gambling behaviour (Canale et al., 2017; Hanss et al., 2014; Hurt et al., 2008; Lussier et al., 2014; Parrado-González et al., 2023; Riley et al., 2021). Finally, school factors such as truancy at school, school difficulties, and low grades were also found to be associated with adolescent gambling (Anagnostopoulos et al., 2017; Dickson et al., 2008; Molinaro et al., 2018). Indeed, lower-than-average academic performance, as measured by students’ self-reported grades in various subjects, including mathematics, was associated with gambling and risky gambling (Wahlström & Olsson, 2023). Maths grades and attitudes can be relevant since erroneous knowledge and understanding of mathematical/probabilistic concepts are recognized to cause gambling-related cognitive distortions influencing gambling behaviour (Delfabbro et al., 2009b; Donati et al., 2018; Raylu & Oei, 2004).

As described, previous studies identified a range of psychological, social, and environmental factors associated with gambling among adolescents. However, most studies were focused on problematic gambling behaviour and conducted on samples of adolescents older than 14 years of age. Given the multifaceted nature of gambling behaviour, the present study adopts an exploratory approach to examine a variety of correlated factors and broad patterns of gambling. The final aim is to comprehensively assess potential influences and generate insights for future hypothesis-driven research, as well as to provide information and knowledge suitable for designing effective school-based programmes to prevent gambling among early adolescents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

This cross-sectional study used data from the baseline survey of the experimental controlled trial “GAPUnplugged” designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the GAPUnplugged school curriculum in preventing gambling among 12–14 years old adolescents. Study design and methods of the trial are described elsewhere (Vigna-Taglianti et al., 2024).

The survey involved 1874 students of 29 secondary schools located in the territories of nine National Health Service (NHS) districts (Rome, Alessandria, Torino 3, Torino 5, Vercelli, Cuneo 1, Cuneo 2, city of Torino, Novara) of Piedmont and Lazio Regions in Italy between November 2022 and January 2023. The analytical sample of the present study included 1822 students who answered the question on gambling behaviour in the last 30 days.

2.2. Data Collection and Data Management

A self-completed anonymous questionnaire was used to collect information on sociodemographic characteristics, substance use, gambling behaviours, beliefs, attitudes, risk perceptions and refusal skills towards gambling, perception of peers’ and friends’ substance use and gambling, friend’s approval of gambling, parental gambling, monitoring, support, permissiveness, school climate, attitudes toward maths and maths grades, self-esteem, impulsiveness, sensation-seeking, and antisocial behaviours.

The questionnaire was developed ad hoc and contained previously validated questions derived from the Unplugged evaluation survey “www.eudap.eu (accessed on 7 September 2022)”, the EDDRA data bank of EMCDDA “www.euda.europa.eu (accessed on 7 September 2022)”, and other international sources and projects (ESPAD, HBSC, Project ALERT, RATING Swedish cohort, SOGS-RA, BSSS). To preserve the confidentiality of the data, a 9-digit individual code was self-generated by the student before filling out the questionnaire.

Only students whose parents or caregivers gave consent to participate were involved in the study. Before the administration of the questionnaire, information on the study was provided to the pupils, and consent to participate was requested. The questionnaires were filled in by students in the classroom during school time through an online application. In cases of a lack of computers or problems of connection, the paper version of the questionnaire was administered.

2.3. Measures

Individual socio-demographic information included grade, age (based on birth date), gender, and languages spoken in the family.

Gambling behaviour was investigated by asking students if they gambled (scratch cards, lottery, bingo, slot machines, sport betting, event betting, poker, cards) during the last 30 days, with response categories ranging on a scale from 0 to 13 times or more for each specific game. A unique variable of gambling behaviour was created, and all the answers were summed up into a dichotomous indicator, “Yes” and “No”.

As regards psychological factors, attitudes, beliefs, risk perceptions, refusal skills, negative mood, impulsiveness, and sensation-seeking were investigated. Positive attitudes toward gambling were assessed through a 3-item scale: “I find it fun”, “I find it enthusiastic”, and “I will become rich”, ranking the answers on a 4-point Likert scale “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree”, and “Strongly disagree”. The reliability of the scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha α = 0.68). Performance beliefs toward gambling were assessed through the following statements “I have an ability to predict my gambling winnings”, “Gambling is a sure way of becoming rich”, “If I gamble often, I have higher probability of winning”, “Winning and losing in gambling depends only on chance”, “Those who play sport have higher probability of winning the sports betting”, “If I come close to winning now, next time I will win”, and “In the lottery, if one number doesn’t come out for a long time, it will certainly come out soon”, ranking the answers on a 4-point Likert scale “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree” and “Strongly disagree”. The reliability of the scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha α = 0.78). Risk perceptions were measured by using the question “How much do you think people risk harming themselves if they gamble” with possible answers “No risk”, “Slight risk”, “Great risk”, and “Don’t know”. Refusal skills were assessed through a situation question investigating students’ ability to cope with gambling offers, providing the following answers on a 4-point Likert scale: “Very likely”, “Likely”, “Unlikely”, and “Very unlikely”. The reliability of the Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.60. Negative mood was measured by the two statements “I feel I have nothing to be proud of” and “I think I am a failure” of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965), allowing the response alternatives on a 4-point Likert scale “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree”, and “Strongly disagree”. The reliability of the scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha α = 0.65). A 5-item scale investigated impulsiveness by asking for opinions on these statements: “I often say or do things without thinking”, “I often get in troubles because I do things without thinking it through”, “I am impulsive person”, “I weight up all the choices before I decide on something” (inversed), and “I often say something off the top of my head”, responding to a 4-point Likert scale with “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree”, and “Strongly disagree”. The reliability of the scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha α = 0.77). Sensation-seeking was evaluated with the Italian version of Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS), including questions on experience seeking (e.g., “I would like to explore strange places”), boredom susceptibility (e.g., “I get restless when I spend too much time at home”), thrill and adventure seeking (e.g., “I like to do frightening things”), and disinhibition (e.g., “I like wild parties”), recording the responses on a 4-point Likert scale with “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree”, and “Strongly disagree” (Primi et al., 2011). The reliability of the scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha α = 0.76). For all these variables, the answers of the Likert scales were scored from 1 to 4 and summed, means were calculated, and categories of high, middle, and low level of the indicator were created by using tertiles.

Questions on the perceived number of friends gambling allowed the answers: “None”, “Less than half of them”, “About half of them”, “More than half of them”, and “All of them”. The question regarding their friends’ approval of gambling allowed the answers “Would approve”, “Would disapprove but still be my friends”, “Would disapprove and stop being my friends”, and “They would not care”. The behaviour of gambling with friends was measured by asking “Have you ever gambled together with friends?” with possible answers including “Never gambled in general”, “Never gambled with friend”, “Sometimes”, and “Often”.

In terms of school behaviours, mathematics grades, attitudes toward mathematics, school performance, and respect for teachers were studied. Mathematics grades were investigated by a specific question, “My math grades are …”, allowing the answers “High”, “Medium”, and “Low”. A 4-item scale assessed the negative attitudes of the student toward mathematics (e.g., “I don’t like it”, “I don’t understand it”, “I make mistakes doing calculations”, “I don’t understand the formulas I have to apply”) allowing answers on a 4-point Likert scale such as “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree”, and “Strongly disagree”. The reliability of the scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha α = 0.82). These answers were scored 1 to 4 and summed, means were calculated, and categories of high, middle, and low level were created by using tertiles. School performance and pupil’s respect for teachers were assessed by a single-item scale “How I do in school matters a lot to me” and “I have great respect for what my teachers tell me”, respectively, allowing answers on a 4-point Likert scale such as “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree”, and “Strongly disagree”. Further details on the measures are provided in the study design paper (Vigna-Taglianti et al., 2024).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The outcome under study was gambling in the last 30 days (yes/no).

Descriptive statistics were summarized through frequency and percentage for categorical variables and mean and SD for continuous variables.

The associations of sociodemographic characteristics, attitudes, and beliefs toward gambling, risk perceptions, refusal skills, negative mood, impulsiveness, sensation-seeking, normative perceptions of friend’s gambling, friends’ approval of gambling, gambling with friends, mathematics grades, negative attitudes toward mathematics, school performance, and respect for teachers with the probability of adolescent’s gambling in the last 30 days were estimated through bivariate regression models. Collinearity between variables was checked before building the final model. Non-collinear and statistically significant variables from the bivariate model were included in the final multivariate regression model simultaneously. Some variables were collinear: “Age” and “Grade” (r = 0.8); “Negative attitudes toward mathematics” and “Mathematics grades” (r = 0.6). We included in the multivariate model the variables “Age” and “Mathematics grades” due to their stronger significance in the bivariate model.

Multilevel mixed-effect modelling was used to control for the hierarchical nature of the data, with two grouping levels: centre as I level, and class as II level. The LR test showed that adding the third level “school” did not make a statistically significant difference, so the two-level model was used. The variable “Centre” was recategorized, merging NHS districts with low sample according to context similarities, so the final variable had four levels, i.e., Rome, Torino3/Torino5/Torino, Vercelli/Cuneo1/Cuneo2, and Alessandria/Novara. Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) and 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI) were estimated as measures of association between the studied factors and the outcome. Some categorical variables were re-coded in order to reduce the number of items included in the model, i.e., categories were merged. Missing data were less than 6% for all studied variables. Applying listwise deletion to handle missing data, the final model was run on 1565 students (86% of the initial sample).

Statistical analysis was carried out using STATA software release 18.0 (Stata Corporation, 2023).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

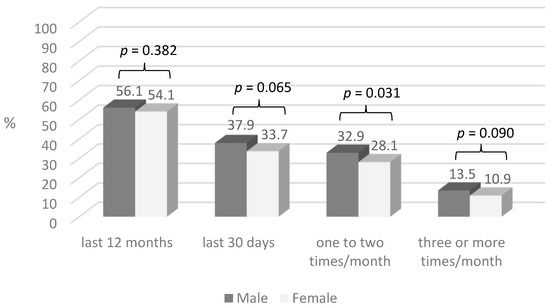

The overall prevalence of last 30 days gambling behaviour was 36.4%, of which 37.9% among males and 33.7% among females (p = 0.065) (Figure 1). A significantly higher proportion of males than females gambled one to two times a month (32.9% vs. 28.1%, p = 0.031).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of gambling behaviours by gender.

Socio-demographic and school behaviours of the pupils are described in Table 1. The mean age was 13.1 (SD ± 0.8). Age did not differ significantly by gambling group. Third-grade students of the first cycle were significantly more prevalent in the gambling vs. non-gambling group (p = 0.004). Regarding the languages spoken in the family, the proportion of students from non-Italian speaking families was higher in the gambling group (28.6% vs. 24.0%, p = 0.029). Only Arabic- and Chinese/Indian/Philippines-speaking families were more prevalent in the non-gambling group. Low mathematic grades (21.6% vs. 17.6%, p = 0.019), low school performance (17.9% vs. 11.2%, p < 0.001), and low respect for teachers (15.2% vs. 9.8%, p = 0.001) were more prevalent in the gambling group. Attitudes toward mathematics did not differ between groups.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and school behaviours of pupils who gamble vs. those who do not gamble in the last 30 days.

In terms of psychological factors, high positive attitudes (43.7% vs. 19.3%, p < 0.001), high performance beliefs toward gambling (40.4% vs. 20.5%, p < 0.001), low and slight risk perceptions (37.4% vs. 21.0% and 29.6% vs. 25.1%, p < 0.001), and low refusal skills (36.1% vs. 16.8%, p < 0.001) were significantly higher among pupils who gambled in the last 30 days. Other characteristics such as having high levels of negative mood (23.2% vs. 18.2%, p = 0.021), high impulsiveness (39.0% vs. 28.4%, p < 0.001), and high sensation-seeking (38.3% vs. 27.3%, p < 0.001) were also significantly higher in the gambling group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Attitudes, beliefs, risk perceptions, skills, mood, impulsiveness, sensation seeking, and normative perceptions of pupils gambling vs. no gambling in the last 30 days.

As regards norms, perception of friends gambling (43.6% vs. 21.0%, p < 0.001) was significantly higher in the gambling group. A higher proportion of pupils who gambled reported their friends would approve of gambling compared to non-gamblers (54.6% vs. 30.0%, p < 0.001). Gambling with friends sometimes and often (20.2% vs. 5.5% and 5.1% vs. 0.8%, p < 0.001) was significantly higher among pupils who gambled (Table 2).

3.2. Multilevel Regression Model

In the multivariate multilevel regression model, some factors (languages in family, school behaviours, refusal skills, negative mood, impulsiveness, and sensation seeking) lost significance.

High positive attitudes toward gambling (OR 1.72, 95%CI 1.26–2.34) were confirmed as independent correlate of adolescent’s gambling behaviour. High performance beliefs toward gambling were associated with 67% higher probability of recent gambling. Slight and low risk perceptions toward gambling were associated with 68% to 98% higher probability of gambling, respectively.

Adolescents who perceived their friends gambled were 1.71 times more likely to engage in gambling (OR 1.71, 95%CI 1.31–2.23). The odds of adolescent’s last 30 days gambling was highest if their friends approved gambling (OR 2.92, 95%CI 1.95–4.37) and would not care if they gambled (OR 1.88, 95%CI 1.28–2.78), as well as if they gambled with friends (OR 2.78, 95%CI 1.90–4.06) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with gambling in the last 30 days.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the association of psychological factors, school behaviours, and normative perceptions with the probability of recent gambling among 1822 secondary school students in Italy. The prevalence of gambling behaviour was very high, with 55.7% of participants (12–14 years old) declaring they have gambled at least once in the last year and 36.4% at least once in the last month. Results showed that attitudes toward gambling, performance beliefs, risk perceptions, and normative perceptions were independent significant correlates of adolescents’ recent gambling behaviour.

The prevalence of last year’s gambling was similar to the 52% prevalence found among 15-year-old students in the study by Favieri et al. (2023), but higher than the 32% found among 16-year-old Italian ESPAD students (Molinaro et al., 2020). However, the sample of students participating in our study were younger than 14 years of age, confirming that gambling behaviour is a worrisome problem even in early ages, although we cannot compare our results with other surveys conducted on early adolescents. Given the precocious age of the study participants, it appears essential to implement prevention programmes focused on gambling behaviour in lower secondary schools and other prevention strategies in the larger community to reduce this risky behaviour.

Adolescents with high positive attitudes toward gambling, i.e., those who stated that they considered gambling fun, exciting, and a chance to become rich, had about 70% higher probability of involvement in gambling behaviour. The role of beliefs and attitudes as determinants of gambling behaviour is well recognized (Derevensky & Gilbeau, 2015; Griffiths & Wood, 2000; Hanss et al., 2014; Hurt et al., 2008; Pallesen et al., 2016). Attitudes and beliefs form from the influence of the general environment, including society, the family, and the media. The latter have a strong role in gambling attitudes of adolescents, e.g., a positive image of gambling is shared by social media that are widely used by adolescents (Delfabbro et al., 2016; O’Loughlin & Blaszczynski, 2018). As a consequence, gambling represents a fun, exciting, and get-rich-quick activity for adolescents (Hurt et al., 2008; Vegni et al., 2019).

High performance beliefs toward gambling, i.e., the perception of knowing gambling rules and how to win, and slight or low risk perceptions toward gambling were significantly correlated with gambling behaviour. Similarly, Favieri et al. (2023) found that 15-year-old adolescents who gamble have greater gambling-related expectancies, illusion of control, predictive control, perceived inability to stop gambling, and interpretative control. This illusion of control may lead adolescents to believe they can control the negative outcomes of the gaming experience (Favieri et al., 2023). Other studies have shown that adolescent gambling is associated with incorrect point of view on the randomness, superstitious beliefs, optimistic attitudes towards the profitability of gambling, and poor perception of the risks associated with gambling (Botella-Guijarro et al., 2020; Delfabbro et al., 2006; Delfabbro et al., 2009a; Delfabbro & Thrupp, 2003; Donati et al., 2013). Adolescents who gamble may not perceive the random nature of gambling but rather have a distorted vision about the real risk of losing money, the impossibility of controlling the game itself, and the prediction of winnings, as they consider gambling to be a harmless and risk-free activity. Furthermore, these aspects are corroborated by the great release of adrenaline that occurs during gambling, which determines a disconnection from reality (Bullock & Potenza, 2012).

Our study confirms the important role of normative beliefs in influencing risk behaviours. Indeed, friends’ gambling, friends’ approval of gambling, and gambling with friends were significantly correlated with adolescent gambling behaviour (Hanss et al., 2014; Hurt et al., 2008; Parrado-González et al., 2023; Riley et al., 2021). A behaviour perceived as being adopted by one’s friends is considered needed to be accepted into the group and be part of it. Behaviours shared and appreciated by friends and perceived as acted by the majority of peers may be considered as correct and risk-free. This concept is in line with the social learning theory, which suggests that behaviours are learned through imitation, modelling, and observation of social interactions with others (Bandura, 1986; Bandura & Walters, 1977).

Finally, we cannot confirm the role of negative mood, impulsiveness, and sensation seeking as independent correlates of gambling behaviour among 12–14-year-old adolescents. These factors indeed lost significance in the adjusted model. The prevalence was not low; therefore, the inconsistency is more likely due to differences in the sample of students analyzed by the studies. Also, it is arguable that other factors are more important in influencing the gambling behaviour in this age group.

This study has several strengths. The surveys used standardized questionnaires containing previously validated questions derived from recognized international sources, minimizing possible misclassifications related to data collection and measures. Multilevel mixed-effect regression models were performed to evaluate the association between correlates and gambling, according to higher-order clustering (centre and class). The information collected in the survey allowed the analysis of a large set of correlates. However, this study should be considered in light of some limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the study prevents inferring causality. Missing values reduced the sample in the adjusted regression models; however, the models were run on 86% of the sample, which is a large sample. All the information was self-reported by the students; therefore, the students’ perceptions of their friends’ gambling and friends’ approval of gambling may not accurately reflect the actual behaviour. Nevertheless, we consider the students’ perceptions of the behaviour and approval of their friends to be important because it may have an even stronger impact on their behaviour. Furthermore, this is a secondary analysis of the study, i.e., the study was designed to evaluate the impact of the school prevention curriculum on reducing gambling behaviour, and this could limit the representativeness of this study. The sample was not equally distributed between the nine centres; therefore, we needed to merge some centres according to similarity between them to perform multilevel analysis by centre.

The results of the study highlight the need to design large and coordinated preventive strategies to prevent gambling in adolescence. In this light, limiting the availability and accessibility of gambling opportunities appears to be of paramount importance. Schools should educate to raise awareness of the harms and the impact of gambling on relationships, finances, and mental health (Giménez Lozano & Morales Rodríguez, 2022; Monreal-Bartolomé et al., 2023). In this regard, promoting the comprehension of complex mathematical concepts such as randomness and expected value can help adolescents to understand the unprofitability and unpredictability of gambling. Indeed, it has been found that focusing only on the negative aspects of gambling and its consequences is not sufficient to prevent gambling behaviour (Keen et al., 2017). Finally, the interventions should use new technologies and multimedia elements to be more attractive to adolescents (Monreal-Bartolomé et al., 2023; St-Pierre & Derevensky, 2016).

In conclusion, the present study identified some psychological factors, school behaviours, and normative perceptions as independent correlates of gambling among adolescents: attitudes toward gambling, performance beliefs, risk perceptions toward gambling, friends’ gambling, friends’ approval of gambling, and gambling with friends. These factors should be taken into account to design and implement preventive strategies to reduce gambling behaviours among early adolescents and limit health consequences in later ages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.V.-T., E.M., M.R., M.G. and C.V.; methodology, F.V.-T., E.M., M.R., A.S., E.V., M.M. and the GAPUnplugged Coordination Group; software, M.R.; validation, E.M., E.V. and M.M.; formal analysis, F.V.-T. and E.M.; investigation, F.V.-T., E.M., M.R., A.S., E.V., M.M., G.G., M.G., C.V., A.C., C.A., S.V. and the GAPUnplugged Coordination Group; resources, F.F., F.V.-T., P.C. and the GAPUnplugged Coordination Group; data curation, F.V.-T., E.M., A.S., G.G., M.G. and C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, F.V.-T., E.M. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, F.V.-T., E.M., M.R., A.S., E.V. and M.M.; visualization, P.C., S.V. and the GAPUnplugged Coordination Group; supervision, F.F. and A.C.; project administration, A.S., E.V., M.M., G.G., M.G., C.V., A.C., C.A., S.V. and the GAPUnplugged Coordination Group; funding acquisition, F.F. and P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by funding of ASLRoma1, regulated through contract n.0005406, 15 October 2020, and by funding of Ministry of University and Research (D.D. n. 1159, 23 July 2023-bando PROBEN, project PROBEN_0000009).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol of the study including details on the study design, materials, intervention, instruments, and procedures for enrolment was submitted to the Novara Ethical Committee, and approval was obtained on 18/11/2022 (prot. 943/CE; study code CE228/2022). Small amendments to the procedures were requested and applied.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided upon request. Federica Vigna-Taglianti is responsible for the data.

Acknowledgments

We thank school principals, teachers, and students for participating, and the members of the GAPUnplugged Coordination Group for their contribution to the study. The GAPUnplugged Coordination Group includes: Federica Vigna-Taglianti, Emina Mehanović, Mariaelisa Renna, Giulia Giraudi, Chiara Sacchi (Department of Translational Medicine, University of Piemonte Orientale, Novara); Adalgisa Ceccano, Maria Ginechesi, Claudia Vullo, Pietro Casella (Department of Mental Health, Addiction Unit, ASL Roma1, Roma); Serena Vadrucci (Department of Prevention, Hygiene and Public Health Unit, ASL Città di Torino, Torino); Fabrizio Faggiano, Chiara Andrà, Alberto Sciutto, Erica Viola, Marco Martorana, Matteo Pezzutto, Cristina Scalvini (Department of Sustainable Development and Ecological Transition, University of Piemonte Orientale, Vercelli); Gian Luca Cuomo, Laura Donati (Piedmont Centre for Drug Addiction Epidemiology, ASL TO3, Grugliasco, Torino).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anagnostopoulos, D. C., Lazaratou, H., Paleologou, M. P., Peppou, L. E., Economou, M., Malliori, M., Papadimitriou, G. N., & Papageorgiou, C. (2017). Adolescent gambling in greater Athens area: A cross-sectional study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(11), 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrie, E. K., Tzavara, C. K., Tzavela, E., Richardson, C., Greydanus, D., Tsolia, M., & Tsitsika, A. K. (2019). Gambling involvement and problem gambling correlates among European adolescents: Results from the European network for addictive behavior study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(11), 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, R. (2021). Gambling among adolescents: An emerging public health problem. Lancet Public Health, 6(3), e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. In The health psychology reader (Vol. 2, pp. 23–28). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1, pp. 141–154). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bergevin, T., Gupta, R., Derevensky, J., & Kaufman, F. (2006). Adolescent gambling: Understanding the role of stress and coping. Journal of Gambling Studies, 22(2), 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella-Guijarro, Á., Lloret-Irles, D., Segura-Heras, J. V., Cabrera-Perona, V., & Moriano, J. A. (2020). A longitudinal analysis of gambling predictors among adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock, S. A., & Potenza, M. N. (2012). Pathological gambling: Neuropsychopharmacology and treatment. Current Psychopharmacology, 1(1), 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, A. N., Pietrzak, R. H., & Petry, N. M. (2006). Pre/early adolescent onset of gambling and psychosocial problems in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 22(3), 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, N., Vieno, A., Griffiths, M. D., Siciliano, V., Cutilli, A., & Molinaro, S. (2017). “I am becoming more and more like my eldest brother!”: The relationship between older siblings, adolescent gambling severity, and the attenuating role of parents in a large-scale nationally representative survey study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfabbro, P., King, D., Lambos, C., & Puglies, S. (2009a). Is video-game playing a risk factor for pathological gambling in Australian adolescents? Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(3), 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfabbro, P., King, D. L., & Derevensky, J. L. (2016). Adolescent gambling and problem gambling: Prevalence, current issues, and concerns. Current Addiction Reports, 3(3), 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfabbro, P., Lahn, J., & Grabosky, P. (2006). Psychosocial correlates of problem gambling in Australian students. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(6–7), 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfabbro, P., Lambos, C., King, D., & Puglies, S. (2009b). Knowledge and beliefs about gambling in Australian secondary school students and their implications for education strategies. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfabbro, P., & Thrupp, L. (2003). The social determinants of youth gambling in South Australian adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 26(3), 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derevensky, J. L., & Gilbeau, L. (2015). Adolescent gambling: Twenty-five years of research. Canadian Journal of Addiction, 6(2), 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, L., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2008). Youth gambling problems: Examining risk and protective factors. International Gambling Studies, 8(1), 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, M. A., Chiesi, F., Iozzi, A., Manfredi, A., Fagni, F., & Primi, C. (2018). Gambling-related distortions and problem gambling in adolescents: A model to explain mechanisms and develop interventions. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, M. A., Chiesi, F., & Primi, C. (2013). A model to explain at-risk/problem gambling among male and female adolescents: Gender similarities and differences. Journal of Adolescence, 36(1), 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, N. A., Merkouris, S. S., Greenwood, C. J., Oldenhof, E., Toumbourou, J. W., & Youssef, G. J. (2017). Early risk and protective factors for problem gambling: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favieri, F., Forte, G., Casagrande, M., Dalpiaz, C., Riglioni, A., & Langher, V. (2023). A portrait of gambling behaviors and associated cognitive beliefs among young adolescents in Italy. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisone, F., Settineri, S., Sicari, P. F., & Merlo, E. M. (2020). Gambling in adolescence: A narrative review of the last 20 years. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 38(4), 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez Lozano, J. M., & Morales Rodríguez, F. M. (2022). Systematic review: Preventive intervention to curb the youth online gambling problem. Sustainability, 14(11), 6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giralt, S., Müller, K. W., Beutel, M. E., Dreier, M., Duven, E., & Wölfling, K. (2018). Prevalence, risk factors, and psychosocial adjustment of problematic gambling in adolescents: Results from two representative German samples. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M., & Wood, R. T. (2000). Risk factors in adolescence: The case of gambling, videogame playing, and the internet. Journal of Gambling Studies, 16(2–3), 199–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanss, D., Mentzoni, R. A., Delfabbro, P., Myrseth, H., & Pallesen, S. (2014). Attitudes toward gambling among adolescents. International Gambling Studies, 14(3), 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hurt, H., Giannetta, J. M., Brodsky, N. L., Shera, D., & Romer, D. (2008). Gambling initiation in preadolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 43(1), 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltenegger, H. C., Låftman, S. B., & Wennberg, P. (2019). Impulsivity, risk gambling, and heavy episodic drinking among adolescents: A moderator analysis of psychological health. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 10, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, B., Blaszczynski, A., & Anjoul, F. (2017). Systematic review of empirically evaluated school-based gambling education programs. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(1), 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2018). Predatory monetization schemes in video games (e.g., ‘loot boxes’) and internet gaming disorder. Addiction, 113(11), 1967–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussier, I. D., Derevensky, J., Gupta, R., & Vitaro, F. (2014). Risk, compensatory, protective, and vulnerability factors related to youth gambling problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 28(2), 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrane, E., Wardle, H., Clowes, M., Blank, L., Pryce, R., Field, M., Sharpe, C., & Goyder, E. (2023). What is the evidence that advertising policies could have an impact on gambling-related harms? A systematic umbrella review of the literature. Public Health, 215, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullan, J. L., & Miller, D. (2010). Advertising the “new fun-tier”: Selling casinos to consumers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, S., Benedetti, E., Scalese, M., Bastiani, L., Fortunato, L., Cerrai, S., Canale, N., Chomynova, P., Elekes, Z., Feijão, F., Fotiou, A., Kokkevi, A., Kraus, L., Rupšienė, L., Monshouwer, K., Nociar, A., Strizek, J., & Urdih Lazar, T. (2018). Prevalence of youth gambling and potential influence of substance use and other risk factors throughout 33 European countries: First results from the 2015 ESPAD study. Addiction, 113(10), 1862–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, S., Vincente, J., Benedetti, E., Cerrai, S., Colasante, E., Arpa, S., & Skarupova, K. (2020). ESPAD Report 2019: Results from European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Available online: https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/joint-publications/espad-report-2019_en (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Monreal-Bartolomé, A., Barceló-Soler, A., García-Campayo, J., Bartolomé-Moreno, C., Cortés-Montávez, P., Acon, E., Huertes, M., Lacasa, V., Crespo, S., Lloret-Irles, D., Sordo, L., Clotas Bote, C., Puigcorbé, S., & López-Del-Hoyo, Y. (2023). Preventive gambling programs for adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montiel, I., Basterra-González, A., Machimbarrena, J. M., Ortega-Barón, J., & González-Cabrera, J. (2022). Loot box engagement: A scoping review of primary studies on prevalence and association with problematic gaming and gambling. PLoS ONE, 17(1), e0263177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, G., Cosenza, M., & Ciccarelli, M. (2017). The blurred future of adolescent gamblers: Impulsivity, time horizon, and emotional distress. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones. (2021). Informe sobre Adicciones Comportamentales 2020: Juego con dinero, uso de videojuegos y uso compulsivo de internet en las encuestas de drogas y otras adicciones en España EDADES y ESTUDES (68p). Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas. Ministerio de Sanidad. Available online: https://pnsd.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/sistemasInformacion/sistemaInformacion/pdf/2020_Informe_adicciones_comportamentales.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- O’Loughlin, I., & Blaszczynski, A. (2018). Comparative effects of differing media presented advertisements on male youth gambling attitudes and intentions. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallesen, S., Hanss, D., Molde, H., Griffiths, M. D., & Mentzoni, R. A. (2016). A longitudinal study of factors explaining attitude change towards gambling among adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrado-González, A., Fernández-Calderón, F., Newall, P. W. S., & León-Jariego, J. C. (2023). Peer and parental social norms as determinants of gambling initiation: A prospective study. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 73(2), 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarska, A., & Ostaszewski, K. (2020). Factors associated with youth gambling: Longitudinal study among high school students. Public Health, 184, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primi, C., Narducci, R., Benedetti, D., Donati, M., & Chiesi, F. (2011). Validity and reliability of the Italian version of the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS) and its invariance across age and gender. Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 18(4), 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A. S., Pilver, C. E., Desai, R. A., Steinberg, M. A., Rugle, L., Krishnan-Sarin, S., & Potenza, M. N. (2012). The relationship between age of gambling onset and adolescent problematic gambling severity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(5), 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. (2004). The gambling related cognitions scale (GRCS): Development, confirmatory factor validation and psychometric properties. Addiction, 99, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reardon, K. W., Wang, M., Neighbors, C., & Tackett, J. L. (2019). The personality context of adolescent gambling: Better explained by the Big Five or sensation-seeking? Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 41(1), 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, B. J., Oster, C., Rahamathulla, M., & Lawn, S. (2021). Attitudes, risk factors, and behaviours of gambling among adolescents and young people: A literature review and gap analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, A., La Rosa, V. L., Commodari, E., Alparone, D., Crescenzo, P., Yıldırım, M., & Chirico, F. (2023). Wanna bet? Investigating the factors related to adolescent and young adult gambling. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(10), 2202–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockloff, M., Russell, A. M. T., Greer, N., Lole, L., Hing, N., & Browne, M. (2021). Young people who purchase loot boxes are more likely to have gambling problems: An online survey of adolescents and young adults living in NSW Australia. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(1), 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Journal of Religion and Health. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, S., Butler, K., & Roberts, A. (2019). Psychosocial risk factors in disordered gambling: A descriptive systematic overview of vulnerable populations. Addictive Behaviors, 99, 106071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklar, A., & Derevensky, J. L. (2011). Way to play: Analyzing gambling ads for their appeal to underage youth. Canadian Journal of Communication, 35(4), 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stata Corporation. (2023). STATA Statistical Software (Release 18.0). StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanovics, E. A., Gueorguieva, R., Zhai, Z. W., & Potenza, M. N. (2023). Gambling participation among Connecticut adolescents from 2007 to 2019: Potential risk and protective factors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 12(2), 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, R., & Derevensky, J. L. (2016). Youth gambling behavior: Novel approaches to prevention and intervention. Current Addiction Reports, 3(2), 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegni, N., Melchiori, F. M., D’Ardia, C., Prestano, C., Canu, M., Piergiovanni, G., & Di Filippo, G. (2019). Gambling behavior and risk factors in preadolescent students: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigna-Taglianti, F. D., Martorana, M., Viola, E., Renna, M., Vadrucci, S., Sciutto, A., Andrà, C., Mehanović, E., Ginechesi, M., Vullo, C., Ceccano, A., Casella, P., Faggiano, F., & The GAPUnplugged Coordination Group. (2024). Evaluation of effectiveness of the unplugged program on gambling behaviours among adolescents: Study protocol of the experimental controlled study “GAPUpplugged”. Journal of Prevention, 45(3), 405–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlström, J., & Olsson, G. (2023). Poor school performance and gambling among adolescents: Can the association be moderated by conditions in school? Addictive Behaviors Reports, 18, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).