Abstract

This study examined the relationships among principals’ servant leadership, kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being, psychological empowerment, and an inclusive atmosphere. A questionnaire survey was conducted with 531 kindergarten teachers using purposive sampling. Results showed that (1) principals’ servant leadership positively predicted teachers’ professional well-being; (2) servant leadership positively predicted teachers’ psychological empowerment; (3) psychological empowerment mediated the relationship between servant leadership and teachers’ professional well-being; and (4) an inclusive kindergarten climate moderated the relationship between servant leadership and psychological empowerment. These findings clarify the mechanism through which servant leadership influences teachers’ professional well-being and provide practical implications for improving kindergarten management and promoting teachers’ occupational well-being.

1. Introduction

Teacher occupational well-being (TWB) is a critical issue for both society and schools (Hascher & Waber, 2021), as it plays an essential role in enhancing teachers’ professional competence and supporting learner development (Madigan & Kim, 2021; Kwon et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024). TWB encompasses teachers’ sense of achievement, self-efficacy, and overall job satisfaction. It is not only a positive emotional state but also a key psychological indicator of work quality (Bardach et al., 2022; Acton & Glasgow, 2015), especially under high job demand and work pressure TWB also influences the quality of teacher–child interactions (Narea et al., 2022) as well as children’s growth, development, and personality formation (Kwon et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2017). In recent years, rising turnover among kindergarten teachers has attracted growing attention across fields (Birch et al., 2018; Xia et al., 2023). Identifying the factors that shape their occupational well-being is therefore essential for stabilizing the workforce and improving the overall quality of preschool education.

Previous research indicates that both personal and organizational characteristics influence teachers’ professional well-being. On the personal level, psychological factors such as psychological well-being (Peele & Wolf, 2021), cognitive regulation (Klusmann et al., 2008), psychological capital (Zhou et al., 2021; Madigan & Kim, 2021), and psychological empowerment (Rantika & Yustina, 2017) are significant determinants. At the organizational level, beyond support (Gang et al., 2018), job stress (Jõgi et al., 2023), and organizational climate (Ji & Yue, 2020), leadership style has been identified as one of the most critical predictors of teachers’ professional well-being (Niinihuhta & Häggman-Laitila, 2022; Das & Pattanayak, 2023; Laine et al., 2017). Servant leadership, in particular, is a teacher-centered approach rooted in service-oriented values. It emphasizes prioritizing teachers’ interests, addressing their needs, fostering professional growth through empowerment, and creating a supportive psychological climate. Compared with other leadership styles, servant leadership is especially attentive to teachers’ professional needs and long-term development (Greenleaf, 2002). Taken together, teachers’ professional well-being is shaped by the interplay of internal psychological resources and external organizational conditions.

Since the 1930s, “happiness” has gained prominence as an academic focus (Lomas et al., 2021). In recent years, educators’ professional well-being has also attracted growing societal concern (Fathi et al., 2020). In China, however, the preschool teaching workforce continues to face challenges such as heavy workloads, relatively low overall qualifications, high occupational mobility, and elevated turnover rates (Qi & Melhuish, 2017). Addressing kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being and identifying effective strategies to enhance it have thus become pressing issues. This study aims to improve the research on kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being to investigate how the servant leadership by kindergarten principals affects the professional well-being of kindergarten teachers and to explore the roles of psychological empowerment and an inclusive atmosphere.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Servant Leadership and Teachers’ Professional Well-Being

Previous research has shown that leaders’ behaviors, leader-employee relationships, and leadership styles are significantly related to employees’ stress levels and affective well-being (Skakon et al., 2010). Servant leadership differs from transformational leadership in both vision formation and trust-building mechanisms, as it emphasizes member well-being (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011) and cultivates trust primarily through emotional bonds rather than cognitive strategies or organizational interests (Schaubroeck et al., 2011). As a result, this leadership style is more effective in eliciting employees’ emotional identification, thereby enhancing their professional well-being.

From a theoretical perspective, servant leadership promotes human values and community-oriented practices by addressing employees’ developmental and psychological needs (Eva et al., 2019; Greenleaf, 2002). Leaders who serve as role models and communicate effectively can strengthen employees’ professional well-being through supportive human resource management (Gallego-Nicholls et al., 2022; Agustin-Silvestre et al., 2024). The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model further explains this process, suggesting that job resources provided by leaders interact with employees’ psychological empowerment to mitigate the negative impact of job demands and foster occupational well-being (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Empirical studies have confirmed that servant leadership is positively related to teachers’ well-being (Jin et al., 2017; Das & Pattanayak, 2023) and can reduce stress, alleviate burnout, and enhance professional happiness by providing sufficient resources (De Jonge & Huter, 2021; Tadić et al., 2015).

Despite extensive evidence from fields such as business and healthcare, empirical research on the impact of servant leadership on well-being in education, particularly in early childhood education, remains limited. This gap highlights the necessity for further investigation into servant leadership as a pathway to enhancing kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being. Thus, the first hypothesis of this study is:

H1.

Servant leadership by principals significantly predicts kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being.

2.2. Psychological Empowerment as a Mediator

Psychological empowerment was first introduced by Conger and Kanungo (1988) and further developed by Spreitzer (1995) as a psychological state shaped by individuals’ holistic perceptions of their work environment. It encompasses four dimensions: job meaning, self-efficacy, autonomy, and job impact. Together, these four elements enable employees to collaborate effectively, make decisions, and manage resources (Spreitzer, 2008). Within the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, the “attrition-path” hypothesis posits that excessive job demands can generate negative emotions when they exceed employees’ capacities. However, psychological empowerment, by interacting with job resources, can buffer the detrimental effects of demands on professional well-being (Bakker et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2023). Leadership styles play a crucial role in this process. Research indicates that servant, transformational, and transactional leadership all significantly influence employees’ psychological empowerment (Schermuly et al., 2022), with servant leadership being particularly effective in strengthening teachers’ empowerment (Van der Hoven et al., 2021). Psychological empowerment, in turn, fosters positive emotions, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and self-confidence, all of which are closely linked to well-being (Hatcher et al., 2023). Empirical evidence also shows that psychological empowerment serves as a mediator in the relationship between leadership style and job satisfaction (Kõiv et al., 2019). Collectively, these findings highlight that organizational leaders can enhance employees’ professional well-being by addressing basic psychological needs and providing meaningful work-related autonomy. Therefore, the second hypothesis of this study is:

H2.

Servant leadership by principals significantly predicts kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being through the mediating role of teachers’ psychological empowerment.

2.3. Inclusive Atmosphere as a Moderator

An inclusive climate integrates diverse personalities and perspectives, reduces bias, and fosters equality in organizational decision-making (Nishii, 2013; Dwertmann & Boehm, 2016). As a form of organizational climate, it highlights leaders’ openness, fairness, and positivity, which in turn shape employees’ cognitions, attitudes, and behaviors (Ali et al., 2022). In diverse workplaces, an inclusive climate provides psychological safety, enabling employees to express themselves and fully utilize their talents (Mousa, 2021). Empirical research shows that an inclusive climate enhances organizational commitment, promotes innovation, and positively moderates the relationship between servant leadership and employees’ occupational well-being (der Kinderen et al., 2020). Within the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, inclusive climates serve as job resources that motivate employees and support their career development (Bakker et al., 2023). By ensuring respect and equality, they reduce interpersonal distance, build trust among colleagues, and foster positive manager–employee relationships (Nishii, 2013; Mor Barak et al., 2016). Hence, the third hypothesis of this study is:

H3.

An inclusive climate moderates the relationship between principals’ servant leadership and teachers’ psychological empowerment.

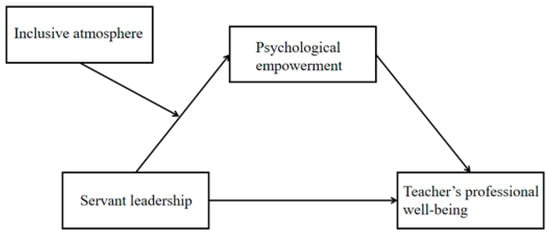

In this context, we propose a moderated mediation model (Figure 1) that clearly illustrates how principals’ servant leadership influences teachers’ professional well-being.

Figure 1.

Moderated mediation model.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

This study used purposive sampling to investigate kindergarten teachers’ perceptions of principals’ servant leadership, the inclusive climate in kindergartens, teachers’ psychological empowerment, and their professional well-being. A total of 628 questionnaires were distributed in northeastern and central China, and 530 valid responses were collected, yielding a valid response rate of 84.39% after excluding questionnaires with unusually short completion times or inconsistent answers. Table 1 displays the details of the respondents.

Table 1.

List of basic information about the respondents to the questionnaire (N = 530).

3.2. Measures

In the survey, teachers provided their demographic information and their perceptions of kindergarten principal’s leadership, school climate, job satisfaction, and psychological empowerment. Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 and Process 3.3. First, SPSS 26.0 was used for data entry and organization, descriptive and correlation analysis. Afterwards, the SPSS macro program Process 3.3, developed by Hayes, was used to select the bootstrap method for estimating the confidence interval, with 5000 repetitions of sampling and the calculation of a 95% confidence interval.

3.2.1. Kindergarten Teachers’ Professional Well-Being

This study adopted the Kindergarten Teacher Occupational Well-Being Scale (KTOWBS), revised by G. Wang (2013). The scale consists of four dimensions: psychological well-being, emotional well-being, social well-being, and cognitive well-being, with a total of 15 items. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each dimension range from 0.87 to 0.90. Emotional well-being refers to the fact that positive emotions prevail at work, with fewer negative emotions observed. Cognitive well-being refers to high satisfaction at work. Psychological well-being refers to the ability to control one’s work and have a sense of fulfillment. Social well-being refers to harmonious and good interpersonal relationships with one’s colleagues. Items 1 to 4 are for psychological well-being, 5 to 7 for emotional well-being, 8 to 11 for social well-being, and 12 to 15 for cognitive well-being. The answers to the questionnaire were based on a 3-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from a complete lack of conformity to complete conformity by 1~3 points. A total of 45 points could be obtained on the questionnaire, with higher scores indicating higher occupational well-being.

3.2.2. Servant Leadership

This study employed the revised Servant Leadership Scale developed by F. Wang (2011), as referenced by Ye et al. (2021). This scale integrates elements from earlier instruments developed by Laub (2005), Patterson (2003), Dennis and Bocarnea (2007), among other scholars. It comprises three dimensions: vision, service, and empowerment, with a total of 14 items. Specifically, items 1 to 4 correspond to the vision dimension, items 5 to 9 to the service dimension, and items 10 to 14 to the empowerment dimension. Responses were collected using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The overall score was calculated as the mean of all items, with higher scores indicating a greater perceived level of servant leadership among kindergarten teachers. The scale demonstrated high reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.91 to 0.94 across dimensions. To better align with the linguistic and contextual expressions of Chinese kindergarten teachers, minor modifications were made to certain items without altering the original scale structure. For example, “My supervisor often asks me about my opinion on the future direction of the company” was changed to “My leader often asks for my opinion on the future development of the kindergarten.” Similarly, “My supervisor prioritizes the personal development of departmental employees” was rephrased as “My leader prioritizes the development of kindergarten teachers.

3.2.3. Psychological Empowerment

The Psychological Empowerment Scale was first developed by Spreitzer (1995) to better measure individual psychological empowerment, with its Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.79 to 0.85 for the dimensions of the source scale. Xiao et al. (2017) used this scale in Chinese context, and its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each dimension ranged from 0.72 to 0.86 (Xiao et al., 2017), indicating the suitability of this tool in China. The scale consists of four dimensions: job meaning, autonomy, self-efficacy, and job impact, with a total of 12 items. Items 1 to 3 are about job meaning, items 4 to 6 are about autonomy, items 7 to 9 are about self-efficacy, and items 10 to 12 are about job impact. The answers are based on a 5-point Likert scale. The higher the score of the servant leadership scale is, the greater the degree to which employees feel psychological empowerment. To make it more consistent with Chinese kindergarten context, this study modified expressions of some questions without changing the structure of the original scale. For example, “I have a powerful influence on the things that happen in my department” was modified to “I have a powerful influence on the teaching and learning that happens in the kindergarten.” And “I have a great deal of control over what happens in my department” was changed to “I have a great deal of control over what happens in kindergarten education”.

3.2.4. Inclusive Climate

The Inclusive Climate Scale developed by Nishii (2013) was used. This scale includes three dimensions: hiring equity, the integration of differences, and the compatibility of decision-making, with a total of 15 items. Items 1 to 6 are about the integration of differences, items 7 to 10 are about the compatibility of decision-making, and items 11 to 15 are about the fairness of hiring. The answers to the questions were categorized on a scale of 1 to 7 using a 7-point Likert scale, with the smallest number representing complete disagreement (Nishii, 2013). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the scale range from 0.95 to 0.97, which is suitable for localized research in China. To ‘better align with the Chinese kindergarten context, this study adapted wording of certain questions without changing the structure of the original scale. For example, “The promotion procedure of the department is fair” was changed to “The promotion procedure of the kindergarten is fair”. And “The department is fair for all staff” was changed to “The promotion procedure of the kindergarten is fair”.

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Test

The data in this study were obtained from self-reports, and common method bias may be present in the measurements. The study used “controlling for unmeasured single-method latent factor methods” to test for common method bias (Xiong et al., 2013). First, a validated factor analysis model, Model F1, was constructed with the following leading fit indices: χ2/df = 4.277, NFI = 0.966, GFI = 0.924, CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.967, and RMSEA = 0.079. Then, Model F2, containing method factors, was constructed based on the original validated factor analysis model, with the following main fit indices: χ2/df = 3.619, NFI = 0.977, GFI = 0.949, CFI = 0.983, TLI = 0.973, and RMSEA = 0.070. The difference between the fitted fit indices of Model F2 and Model F1 was slight, the indices of the CFI and TLI did not exceed 0.1, and the change in the RMSEA did not exceed 0.05. This indicated that the model was not significantly improved by adding the common method factor, and this study has no serious standard method bias.

4.2. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlation Coefficients for Each Variable

Table 2 presents the mean, standard deviation, and correlation matrix of the variables. There is a significant correlation between kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being, principals’ servant leadership, and kindergarten teachers’ psychological empowerment. The results of the study provide data support for subsequent modeling.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for key variables and covariates (N = 530).

4.3. Moderated Mediation Model Test

In the first step, a simple mediation model was tested. In the moderated mediation model, the simple mediation model is the benchmark model, which was tested first (Wen & Ye, 2014). In this study, Model 4 was first chosen to test the mediating role of psychological empowerment between principals’ servant leadership and kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being. The results of regression analysis showed that the demographic variables of kindergarten grade, kindergarten teachers’ age, education level, and enrollment status were significantly different for the variables of principals’ servant leadership, kindergarten teachers’ psychological empowerment, and kindergarten teachers’ occupational well-being, respectively. Thus, in controlling for kindergarten grade, as well as kindergarten teachers’ age, education level, and enrollment status, principals’ servant leadership significantly and positively predicted kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being (β = 0.269, p < 0.001). This proves that Hypothesis H1 is valid. When the mediator variable of kindergarten teachers’ psychological empowerment was introduced, principals’ servant leadership significantly and positively predicted kindergarten teachers’ psychological empowerment (β = 0.735, p < 0.001), and psychological empowerment was able to positively predict kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being (β = 0.137, p < 0.001). Moreover, the effect of principals’ ‘servant leadership on kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being remained significant (β = 0.101, p < 0.001). In sum, an equation model for the partial mediation role of psychological empowerment was established, with the partial mediation effect accounting for 49.070% of the total effect (Table 3). As such, Hypothesis H2 is supported.

Table 3.

Bootstrap analysis of mediation effects (N = 530).

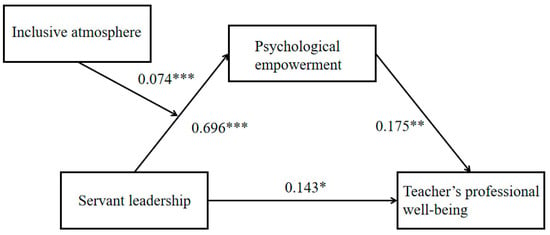

4.4. Moderated Mediation Effects Test

In the second step, the mediating effect with moderation was tested. The model was chosen for testing since the moderating variables moderated the first half of the mediating effect. This study revealed that the demographic variables of kindergarten grade, kindergarten teachers’ age, education level, and enrollment status differed significantly for the variables of principals’ servant leadership, kindergarten teachers’ psychological empowerment, and kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being, respectively. Thus, in controlling for kindergarten grade as well as kindergarten teachers’ age, education level, title, and enrollment status, principals’ servant leadership positively predicted teachers’ psychological empowerment (β = 0.696, p < 0.001), and an inclusive climate positively predicted kindergarten teachers’ psychological empowerment (β = 0.145, p < 0.001). Moreover, the interaction term between principals’ servant leadership and an inclusive climate also significantly predicted teachers’ psychological empowerment (β = 0.074, p < 0.001), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.028, 0.120]. See Table 4 and Figure 2 for details.

Table 4.

Mediated model tests with adjustment (n = 530).

Figure 2.

Path diagram. Note: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

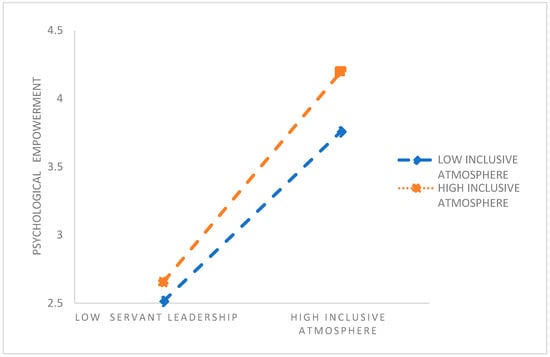

To further understand the essence of the interaction between an inclusive climate and principals’ servant leadership, the inclusive climate was divided into a robust and inclusive climate group and a weak inclusive climate group according to one standard deviation of the mean. Table 5 depicts the mediation effect values and 95% bootstrap confidence intervals of teachers’ psychological empowerment between principals’ servant leadership and kindergarten teachers’ occupational well-being in the two groups of participants. Further simple slope analyses showed (e.g., Figure 3) that in the weakly inclusive climate group, principals’ servant leadership significantly and positively predicted kindergarten teachers’ psychological empowerment (βsimple = 0.696, t = 15.563, p < 0.001). In contrast, in the strongly inclusive climate group, principals’ servant leadership positively predicted kindergarten teachers’ psychological empowerment even more strongly (βsimple = 0.770, t = 7.029, p < 0.001). Taken together, these results indicate differences in the level of inclusive climate within different kindergartens, and that the predictive effect of principals’ servant leadership on kindergarten teachers’ psychological empowerment tends to increase as the overall level of the kindergarten’s inclusive climate increases. These results imply that Hypothesis H3 is valid.

Table 5.

The mediating effects of psychological empowerment.

Figure 3.

Slope plot.

5. Discussion

As societies advance, priorities have shifted from production efficiency to inner spirituality and experiential well-being, driving growing interest in more humanistic leadership models. Existing research on servant leadership has primarily examined its effects on employee job satisfaction (Lapointe & Vandenberghe, 2018), organizational citizenship behavior (Neubert et al., 2008), and helping behavior (Walumbwa et al., 2010) from a managerial perspective, while giving limited attention to teachers’ professional well-being in educational settings. This study addresses this gap by framing servant leadership as a key antecedent of kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being. It underscores the importance of leadership practices that enhance teachers’ job satisfaction and highlights the mechanisms through which servant leadership contributes to positive work experiences, workforce stability, and organizational efficiency. The findings provide practical insights for kindergarten administrators to refine leadership styles and adopt more humanistic management approaches that better support teachers’ professional well-being.

5.1. Servant Leadership and Kindergarten Teachers’ Professional Well-Being

Data analysis revealed a significant positive relationship between principals’ servant leadership and kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being, consistent with previous findings (Jin et al., 2017; Das & Pattanayak, 2023). Leadership style is a key determinant of employees’ mental health and occupational well-being (Kelloway & Barling, 2010), yet many studies have overlooked employee well-being as a primary outcome (Montano et al., 2017; Inceoglu et al., 2018). Due to the demanding nature of their work, kindergarten teachers are particularly vulnerable to burnout and chronic stress, which can impair both their mental health and career development (Peele & Wolf, 2021; Tang et al., 2018; Madigan et al., 2023). Compared to other leadership styles, servant leadership places greater emphasis on teachers’ well-being by creating supportive work environments and addressing psychological needs (Ozyilmaz & Cicek, 2015; Jit et al., 2017). Guided by the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model, servant leadership provides teachers with critical resources and emotional support that mitigate job stress and enhance professional well-being (De Nobile, 2017). These findings highlight the importance for kindergarten principals to adopt servant leadership practices, foster a culture of respect and support, and actively promote teachers’ occupational well-being.

5.2. The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment

This study found that principals’ servant leadership enhances kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being by strengthening their psychological empowerment. Previous research has confirmed that psychological empowerment serves as a key mediating variable linking leadership style to employees’ perceptions and behaviors (Saira et al., 2021; Kundu et al., 2019). According to the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model, servant leadership, grounded in service and collaboration, provides teachers with appropriate job resources, strengthens psychological empowerment, and promotes greater work engagement and job satisfaction (Bakker et al., 2023).

In China, kindergarten teachers often face high parental expectations and heavy workloads (Berger et al., 2019), resulting in exhaustion and burnout (Hu et al., 2017) andhighlighting the need to improve their professional well-being. As a critical factor, psychological empowerment mediates the impact of servant leadership on teachers’ well-being. Therefore, kindergarten principals should recognize the multiple determinants of teachers’ psychological empowerment and adopt sustained strategies to strengthen both their empowerment and overall professional well-being.

5.3. The Moderating Role of an Inclusive Atmosphere

Data analysis indicates that an inclusive kindergarten climate moderates the relationship between principals’ servant leadership and teachers’ psychological empowerment, echoing findings from previous studies (Kuknor & Bhattacharya, 2022; Davies et al., 2019; Mousa, 2021). Social context theory posits that team environment and organizational climate shape members’ perceptions and behaviors. A positive climate fosters satisfaction and creativity, whereas a hostile climate undermines well-being (Battistelli et al., 2022). Organizational climate can thus modulate the effects of leadership on employee attitudes and performance (Megawaty et al., 2022).

As a specific form of organizational climate, inclusiveness promotes equality, respect, and openness, encouraging employees to embrace diversity and address challenges collaboratively (Nishii, 2013; Dwertmann & Boehm, 2016). In diverse work settings, an inclusive climate provides psychological safety, motivates talent utilization, and strengthens the employee–organization relationship (der Kinderen et al., 2020; Bodla et al., 2023; Li et al., 2017). In this study, the moderating effect of an inclusive climate was stronger in kindergartens with higher inclusiveness, which enhanced teachers’ perception of positive leadership, their willingness to express themselves, and their sense of competence. These findings suggest that kindergarten principals should adopt servant leadership practices and foster an inclusive organizational climate to strengthen teachers’ psychological empowerment, organizational commitment, and overall professional well-being.

6. Limitations, Implications and Conclusions

This study examined the mechanism through which principals’ servant leadership affects kindergarten teachers’ professional well-being, but several limitations should be noted. First, due to constraints of time, geography, and researcher experience, the sample size was relatively small and unevenly distributed. In addition, purposive sampling may have introduced researcher bias, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future studies may consider expand the sample size and diversity, covering different regions and participant groups to enhance representativeness. Second, the cross-sectional design limited the ability to examine temporal dynamics and establish causal relationships. Longitudinal designs with multiple data waves could better control extraneous factors and provide more precise insights. Third, the measures used, the Psychological Empowerment Scale and Inclusive Atmosphere Scale, were adapted from foreign instruments. Despite translation and validation efforts, cultural differences may have affected their construct validity and applicability in the Chinese preschool context. Fourth, reliance on self-reported data may have introduced social desirability bias, as teachers could overreport positive feelings or behaviors to align with professional or societal expectations, a limitation particularly salient in early childhood education research. Finally, the study focused only on the managerial perspective of how servant leadership influences teachers’ professional well-being. Future research should explore additional factors, introduce new variables, and further refine the underlying mechanisms. Despite these limitations, this study adopts the job demands-resources theory and social context theory as research perspectives, incorporating the variables of psychological empowerment and inclusive climate to explore the impact of servant leadership on the professional well-being of kindergarten teachers in depth, thereby further improving research in this field. It not only enriches the understanding of the internal mechanisms through which servant leadership affects the professional well-being of kindergarten teachers, but also further investigates the pathways through which servant leadership influences them, thus holding certain theoretical significance and practical value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Y., W.Y. and S.H.; methodology, W.Y. and S.H.; software, W.Y.; validation, D.Y., W.Y. and S.H.; formal analysis, W.Y.; investigation, D.Y. and W.Y.; resources, D.Y.; data curation, W.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Y. and W.Y.; writing—review and editing, D.Y., W.Y. and S.H.; visualization, W.Y.; supervision, D.Y. and Q.W.; project administration, D.Y. and D.L.; funding acquisition, D.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by General Programs of the National Social Science Fund of China, China (Grant No. BGA230264).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Northeast Normal University (approval number EF2024-98, approval date: 20 December 2024). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all those who contributed to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acton, R., & Glasgow, P. (2015). Teacher wellbeing in neoliberal contexts: A review of the literature. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 40(8), 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustin-Silvestre, J. A., Villar-Guevara, M., García-Salirrosas, E. E., & Fernández-Mallma, I. (2024). The human side of leadership: Exploring the impact of servant leadership on work happiness and organizational justice. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A., Ali, S. M., & Xue, X. (2022). Motivational approach to team service performance: Role of participative leadership and team-inclusive climate. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 52, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job demands–resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardach, L., Klassen, R. M., & Perry, N. E. (2022). Teachers’ psychological characteristics: Do they matter for teacher effectiveness, teachers’ well-being, retention, and interpersonal relations? An integrative review. Educational Psychology Review, 34(1), 259–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistelli, A., Odoardi, C., Cangialosi, N., Di Napoli, G., & Piccione, L. (2022). The role of image expectations in linking organizational climate and innovative work behaviour. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(6), 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R., Czakert, J. P., Leuteritz, J. P., & Leiva, D. (2019). How and when do leaders influence employees’ well-being? Moderated mediation models for job demands and resources. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, P., Balcon, M. P., Bourgeois, A., Davydovskaia, O., & Tremosa, S. P. (2018). Teaching careers in Europe: Access, progression and support. Eurydice report. Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency, European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Bodla, A. A., Li, Y., Ali, A., & Hernandez Bark, A. S. (2023). Female leaders’ social network structures and managerial performance: The moderating effects of promotional orientation and climate for inclusion. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 64(2), 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1988). The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. S., & Pattanayak, S. (2023). Understanding the effect of leadership styles on employee well-being through leader-member exchange. Current Psychology, 42(25), 21310–21325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S. E., Stoermer, S., & Froese, F. J. (2019). When the going gets tough: The influence of expatriate resilience and perceived organizational inclusion climate on work adjustment and turnover intentions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(8), 1393–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J., & Huter, F. F. (2021). Does match really matter? The moderating role of resources in the relation between demands, vigor and fatigue in academic life. The Journal of Psychology, 155(6), 548–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, R., & Bocarnea, M. (2007). Servant leadership assessment instrument. In Handbook of research on electronic surveys and measurements (pp. 339–342). IGI Global. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- De Nobile, J. (2017). Organisational communication and its relationships with job satisfaction and organisational commitment of primary school staff in Western Australia. Educational Psychology, 37(3), 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- der Kinderen, S., Valk, A., Khapova, S. N., & Tims, M. (2020). Facilitating eudaimonic well-being in mental health care organizations: The role of servant leadership and workplace civility climate. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwertmann, D. J. G., & Boehm, S. A. (2016). Status matters: The asymmetric effects of supervisor-subordinate disability incongruence and climate for inclusion. Academy of Management Journal, 59(1), 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., Van Dierendonck, D., & Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, J., Derakhshan, A., & Saharkhiz Arabani, A. (2020). Investigating a structural model of self-efficacy, collective efficacy, and psychological well-being among Iranian EFL teachers. Iranian Journal of Applied Language Studies, 12(1), 123–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Nicholls, J. F., Pagán, E., Sánchez-García, J., & Guijarro-García, M. (2022). The influence of leadership styles and human resource management on educators’ well-being in the light of three Sustainable Development Goals. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 35(2), 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, W., Yong, F., Xu, H., Liu, X. Q., & Wang, D. L. (2018). Effects of government support, organizational support and competency on occupational well-being among kindergarten teachers: Mediating effect of occupational identity. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 16(6), 801. [Google Scholar]

- Greenleaf, R. K. (2002). Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hascher, T., & Waber, J. (2021). Teacher well-being: A systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educational Research Review, 34, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, J. A., Bringle, R. G., & Hahn, T. W. (Eds.). (2023). Research on student civic outcomes in service learning: Conceptual frameworks and methods. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B. Y., Zhou, Y., Chen, L., Fan, X., & Winsler, A. (2017). Preschool expenditures and Chinese children’s academic performance: The mediating effect of teacher-child interaction quality. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 41, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inceoglu, I., Thomas, G., Chu, C., Plans, D., & Gerbasi, A. (2018). Leadership behavior and employee well-being: An integrated review and a future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D., & Yue, Y. (2020). Relationship between kindergarten organizational climate and teacher burnout: Work–family conflict as a mediator. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L. N., Liu, T., & Chen, Y. W. (2017, December 10–13). The effect of servant leadership on work-related well-being: The mediating role of work flow and work engagement. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM) (pp. 2210–2214), Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Jit, R., Sharma, C. S., & Kawatra, M. (2017). Healing a broken spirit: Role of servant leadership. Vikalpa, 42(2), 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jõgi, A. L., Aulén, A. M., Pakarinen, E., & Lerkkanen, M. K. (2023). Teachers’ daily physiological stress and positive affect in relation to their general occupational well-being. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E. K., & Barling, J. (2010). Leadership development as an intervention in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 24(3), 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2008). Teachers’ occupational well-being and quality of instruction: The important role of self-regulatory patterns. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(3), 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõiv, K., Liik, K., & Heidmets, M. (2019). School leadership, teacher’s psychological empowerment and work-related outcomes. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(7), 1501–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuknor, S. C., & Bhattacharya, S. (2022). Inclusive leadership: New age leadership to foster organizational inclusion. European Journal of Training and Development, 46(9), 771–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S. C., Kumar, S., & Gahlawat, N. (2019). Empowering leadership and job performance: Mediating role of psychological empowerment. Management Research Review, 42(5), 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K. A., Horm, D. M., & Amirault, C. (2021). Early childhood teachers’ well-being: What we know and why we should care. Zero to Three Journal, 41(3), 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Laine, S., Saaranen, T., Ryhänen, E., & Tossavainen, K. (2017). Occupational well-being and leadership in a school community. Health Education, 117(1), 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, E., & Vandenberghe, C. (2018). Examination of the relationships between servant leadership, organizational commitment, and voice and antisocial behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laub, J. (2005). From paternalism to the servant organization: Expanding the organizational leadership assessment (OLA) model. The International Journal of Servant-Leadership, 1(1), 155–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. R., Lin, C. J., Tien, Y. H., & Chen, C. M. (2017). A multilevel model of team cultural diversity and creativity: The role of climate for inclusion. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 51(2), 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, T., Case, B., Cratty, F. J., & VanderWheele, T. (2021). A global history of happiness. International Journal of Wellbeing, 11(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., Kim, L. E., Glandorf, H. L., & Kavanagh, O. (2023). Teacher burnout and physical health: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research, 119, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megawaty, M., Hamdat, A., & Aida, N. (2022). Examining linkage leadership style, employee commitment, work motivation, work climate on satisfaction and performance. Golden Ratio of Human Resource Management, 2(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D., Reeske, A., Franke, F., & Hüffmeier, J. (2017). Leadership, followers’ mental health and job performance in organizations: A comprehensive meta-analysis from an occupational health perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(3), 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor Barak, M. E., Lizano, E. L., Kim, A., Duan, L., Rhee, M. K., Hsiao, H. Y., & Brimhall, K. C. (2016). The promise of diversity management for a climate of inclusion: A state-of-the-art review and meta-analysis. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(4), 305–333. [Google Scholar]

- Mousa, M. (2021). Does gender diversity affect workplace happiness for academics? The role of diversity management and organizational inclusion. Public Organization Review, 21(1), 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narea, M., Treviño, E., Caqueo-Urízar, A., Miranda, C., & Gutiérrez-Rioseco, J. (2022). Understanding the relationship between preschool teachers’ well-being, interaction quality and students’ well-being. Child Indicators Research, 15(2), 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M. J., Kacmar, K. M., Carlson, D. S., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2008). Regulatory focus as a mediator of the influence of initiating structure and servant leadership on employee behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinihuhta, M., & Häggman-Laitila, A. (2022). A systematic review of the relationships between nurse leaders’ leadership styles and nurses’ work-related well-being. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 28(5), e13040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L. H. (2013). The benefits of climate for inclusion for gender-diverse groups. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1754–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyilmaz, A., & Cicek, S. S. (2015). How does servant leadership affect employee attitudes, behaviors, and psychological climates in a for-profit organizational context? Journal of Management & Organization, 21(3), 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K. A. (2003). Servant leadership: A theoretical model. Regent University. [Google Scholar]

- Peele, M., & Wolf, S. (2021). Depressive and anxiety symptoms in early childhood education teachers: Relations to professional well-being and absenteeism. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 55(2), 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X., & Melhuish, E. C. (2017). Early childhood education and care in China: History, current trends and challenges. Early Years, 37(3), 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantika, S. D., & Yustina, A. I. (2017). Effects of ethical leadership on employee well-being: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business: JIEB, 32(2), 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saira, S., Mansoor, S., & Ali, M. (2021). Transformational leadership and employee outcomes: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(1), 130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Schaubroeck, J., Lam, S. S. K., & Peng, A. C. (2011). Cognition-based and affective-based trust as mediators of leader behavior influence on team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermuly, C. C., Creon, L., Gerlach, P., Graßmann, C., & Koch, J. (2022). Leadership styles and psychological empowerment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 29(1), 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skakon, J., Nielsen, K., Borg, V., & Guzman, J. (2010). Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work & Stress, 24(2), 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (2008). Taking stock: A review of more than twenty years of research on empowerment at work. Handbook of Organizational Behavior, 1, 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R., Yang, H. M., Chau, C. T., Cheong, I. S., & Wu, A. M. (2023). Psychological empowerment, work addiction, and burnout among mental health professionals. Current Psychology, 42(29), 25602–25613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, M., Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. (2015). Challenge versus hindrance job demands and well-being: A diary study on the moderating role of job resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(4), 702–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., He, W., Liu, L., & Li, Q. (2018). Beyond the paycheck: Chinese rural teacher well-being and the impact of professional learning and local community engagement. Teachers and Teaching, 24(7), 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hoven, A. G., Mahembe, B., & Hamman-Fisher, D. (2021). The influence of servant leadership on psychological empowerment and organisational citizenship on a sample of teachers. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 19, a1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dierendonck, D., & Nuijten, I. (2011). The servant leadership survey: Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(3), 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F. O., Hartnell, C. A., & Oke, A. (2010). Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-level investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(3), 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. (2011). An empirical study on the relationship between servant leadership, organizational citizenship behavior, and employee turnover [Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University]. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=H1ADs8FciQ_kLW4KOaOokNgYsXHWtLfPSi1a1qOmFXVs-tXEjKDTIHGO2hWS39w1wGK5mM6XPotqyCsLyy6KQt5kn8Y9olqpzUW-9nsVdiCkV64cxYhVQS-VvGstdF4N6lpfCoDxNL4E9AZUaIO56Iz_Gc--058MOPPtPBFKAeXvmkF8F7_wqQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Wang, G. (2013). The characteristics of kindergarten teachers’ occupational well-being and its relationship with occupational commitment. Psychological Development and Education, 29(06), 616–624. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z., & Ye, B. (2014). Different methods for testing moderated mediation models: Competitors or backups? Acta Psychologica Sinica, 46(5), 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J., Wang, M., & Zhang, S. (2023). School culture and teacher job satisfaction in early childhood education in China: The mediating role of teaching autonomy. Asia Pacific Education Review, 24(1), 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J., Liu, T., & Chen, Y. (2017, December 10–13). The impact of performance feedback on work engagement—The mediating effect of psychological empowerment. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM) (pp. 2199–2203), Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, H., Zhang, J., Ye, B., Zheng, X., & Sun, P. (2013). Common method variance effects and the models of statistical approaches for controlling it. Advances in Psychological Science, 20(5), 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B. J., Cai, Y. J., Liu, L., & Fu, H. H. (2021). The effect of servant leadership on employees’ job performance: A moderated mediation model at different levels. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, (2), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Chen, J., Li, X., & Zhan, Y. (2024). A scope review of the teacher well-being research between 1968 and 2021. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 33(1), 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., Wang, D., Zhou, L., Liu, Y., & Hu, Y. (2021). The effect of work-family conflict on occupational well-being among primary and secondary school teachers: The mediating role of psychological capital. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 745118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).