Current Trends in Music Performance Anxiety Intervention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

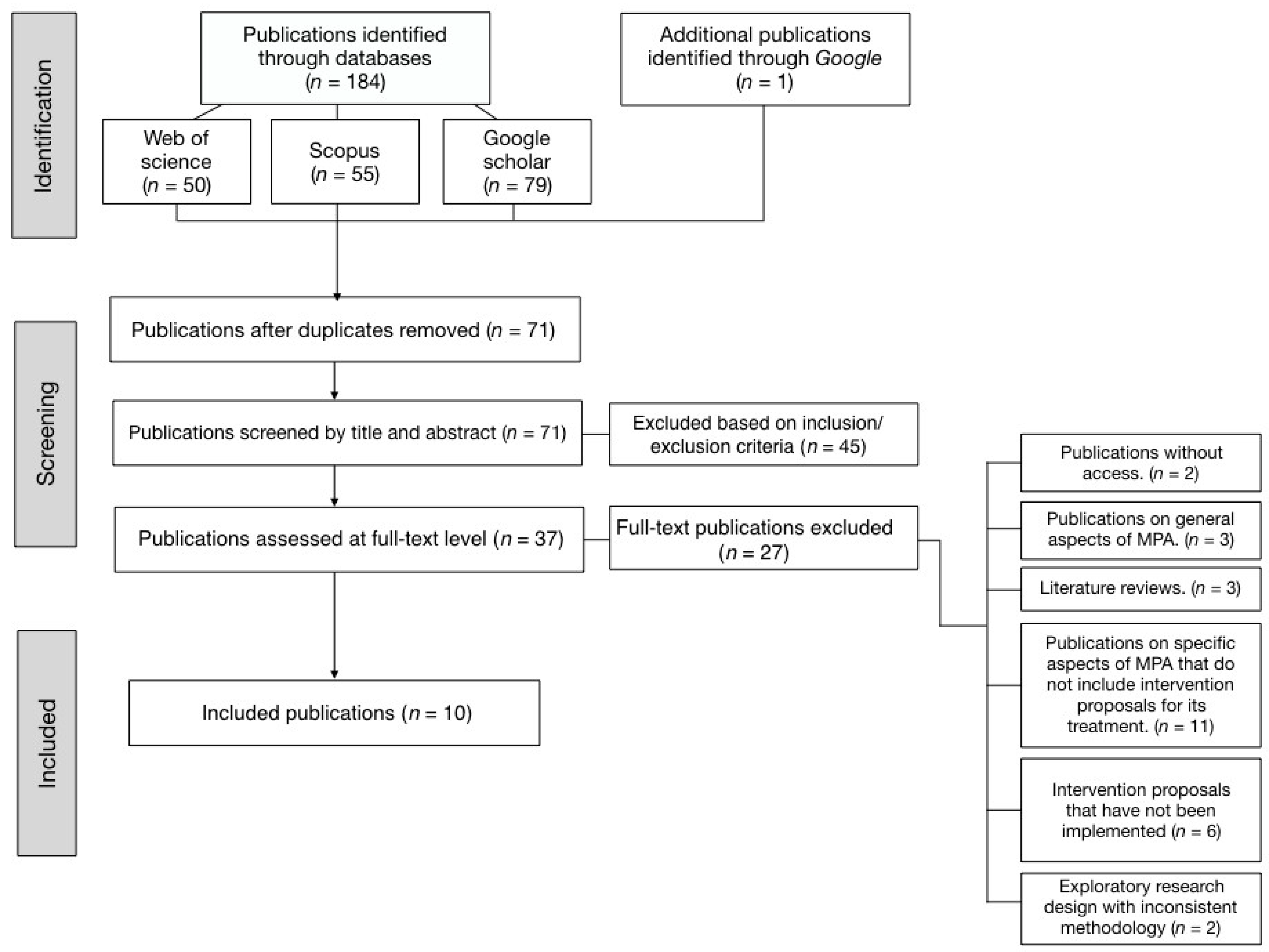

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Method

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Strengths

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D.T. A Systematic Review of Treatments for Music Performance Anxiety. Anxiety Stress Coping 2005, 18, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Hernández, N.L.; González-Santoyo, I.; López-Tello, A.; Moreno-Coutiño, A.B. Intervención basada en atención plena compasiva en estudiantes de música con sintomatología ansiosa. Psicol. Salud 2023, 33, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-92-4-154916-5.

- Díaz, F.M. Relationships Among Meditation, Perfectionism, Mindfulness, and Performance Anxiety Among Collegiate Music Students. J. Res. Music Educ. 2018, 66, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Torres, L.; Campoy-Barreiro, C. Ansiedad escénica musical en profesorado de conservatorio: Frecuenciay análisis por género. Rev. Psicol. Educ. 2020, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernholz, I.; Mumm, J.L.M.; Plag, J.; Noeres, K.; Rotter, G.; Willich, S.N.; Ströhle, A.; Berghöfer, A.; Schmidt, A. Performance Anxiety in Professional Musicians: A Systematic Review on Prevalence, Risk Factors and Clinical Treatment Effects. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 2287–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. The Psychology of Music Performance Anxiety; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-19-162099-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dalia, G. El Músico Adicto. La Musicorexia; Ideamusica: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lledó-Valor, R. Las Habilidades Interpretativas y Personales del Músico: Programa para Mejorar la Interpretación Saxofonística en Público. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Catolica de Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester-Martínez, J. Un Estudio de la Ansiedad Escénica en los Músicos de los Conservatorios de la Región de Murcia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nwokenna, E.N.; Sewagegn, A.A.; Falade, T.A. Effect of Educational Music Intervention on Emotion Regulation Skills of First-Year University Music Education Students. Medicine 2022, 101, e32041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.P. A National Analysis of Music Coursetaking, Social-Emotional Learning, and Academic Achievement Using Propensity Scores. J. Res. Music Educ. 2022, 69, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernuda, A. La ansiedad escénica en los músicos profesionales de alto rendimiento. Un problema de adicción y salud pública. In Proceedings of the II Congreso Virtual Internacional de Psicología, Online, 26 April 2018; Volume 2, p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte-Useros, E.B. Canto. Bases y Método: 1, 1st ed.; Almud Ediciones de Castilla-La Mancha: Albacete, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-84-946676-3-3. [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, E.; Jasusch, H.-C. Focal Dystonia in Musicians: Phenomenology, Pathophysiology, Triggering Factors, and Treatment. Med. Probl. Perform. Artists 2010, 25, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, V.; Burwell, K.; PICKUP, D. Areas of Study and Teaching Strategies Instrumental Teaching: A Case Study Research Project. Music Educ. Res. 2003, 5, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Morante, B.; Ortiz, F.D.P.; Blanco-Piñeiro, P. Profesionales de la psicología como docentes en los conservatorios de música: Hacia una educación musical sostenible. Pap. Psicol. 2020, 41, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosset, J.; Odam, G. The Musician’s Body: A Maintenance Manual for Peak Performance; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgi, I. Prevalence and Predictors of Music Performance Anxiety in Adolescent Learners: Contributions of Individual, Task-Related and Environmental Factors. Music Sci. 2022, 26, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P. Fear Reduction and Fear Behavior: Problems in Treating a Construct. In Proceedings of the Research in Psychotherapy Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 3 May–1 June 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño-López, D.; Osorno-Cardona, A.M. Niveles de Ansiedad en Bailarines de Competencia, en una Academia de Baile de la Ciudad de Medellín. Ph.D. Thesis, Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios, Bogotá, Columbia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, D.H. Unraveling the Mysteries of Anxiety and Its Disorders from the Perspective of Emotion Theory. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Granados, L.M.; Bonastre, C. La Ansiedad en la Interpretación Musical: Programa de intervención en un coro. Rev. Electrónica Complut. Investig. Educ. Music 2021, 18, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.K.; Srinivasan, M.; Sarkar, S.; Kaur, R.; Sharma, Y.; Venkatesan, L.; Gupta, S.; Venugopal, A. Depression, Anxiety, Insomnia, and Distress among Health-Care Workers Posted in COVID-19 Care. Indian J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2023, 20, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Gonzáles, J.L.A.; Cáceres-Chávez, M.D.R.C. Ansiedad escénica y ejecución musical en estudiantes del conservatorio de música en Arequipa, 2020. ESCENA Rev. Artes 2021, 81, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgi, I.; Hallam, S.; Welch, G.F. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Musical Performance Anxiety. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 2007, 28, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbeau, A.K. Performance Anxiety Inventory for Musicians (PerfAIM): A New Questionnaire to Assess Music Performance Anxiety in Popular Musicians; McGill University Libraries: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Morante, B. Psychological Violence in Current Musical Education at Conservatoires. Rev. Int. Educ. Music 2018, 6, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukov, K. Current Approaches for Management of Music Performance Anxiety: An Introductory Overview. Med. Probl. Perform. Artists 2019, 34, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Torres, L.; Manjón, G.J.; Quiles, O.L. Ansiedad escénica musical en alumnos de flauta travesera de conservatorio. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2015, 32, 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Burin, A.B.; Barbar, A.E.M.; Nirenberg, I.S.; Osório, F.d.L. Music Performance Anxiety: Perceived Causes, Coping Strategies and Clinical Profiles of Brazilian Musicians. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2020, 41, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burin, A.B.; Osório, F.D.L. Interventions for Music Performance Anxiety: Results from a Systematic Literature Review. Arch. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 43, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Serna, K.V.; Orozco Núñez, D.M.; Pérez Navas, E.C.; Conde Cardona, G.; Barrios Serna, K.V.; Orozco Núñez, D.M.; Pérez Navas, E.C.; Conde Cardona, G. Nuevas recomendaciones de la versión PRISMA 2020 para revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Acta Neurológica Colomb. 2021, 37, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Mckenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Mother, D. A Declaração PRISMA 2020: Diretriz Atualizada Para Relatar Revisões Sistemáticas. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2022, 46, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Serrano, S.; Pedraza-Navarro, I.; Donoso-González, M. ¿Cómo hacer una revisión sistemática siguiendo el protocolo PRISMA? Usos y estrategias fundamentales para su aplicación en el ámbito educativo a través de un caso práctico. Bordón Rev. Pedagog. 2022, 74, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.K.; Osborne, M.S.; Baranoff, J.A. Examining a Group Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Intervention for Music Performance Anxiety in Student Vocalists. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 538344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czajkowski, A.M.L.; Grasley, A.E.; Allis, M. Mindfulness for Musicians: A Mixed Methods Study Investigating the Effects of 8-Week Mindfulness Courses on Music Students at a Leading Conservatoire. Music. Sci. 2022, 26, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima-Osório, F.; Espitia-Rojas, G.V.; Aguiar-Ricz, L.N. Effects of Intranasal Oxytocin on the Self-Perception and Anxiety of Singers during a Simulated Public Singing Performance: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 943578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Bofill, L.; López de la Llave, A.; Pérez-Llantada, M.C.; Holgado-Tello, F.P. Development of Flow State Self-Regulation Skills and Coping With Musical Performance Anxiety: Design and Evaluation of an Electronically Implemented Psychological Program. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 899621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, T.A.; Juncos, D.G.; Winter, D. Piloting a New Model for Treating Music Performance Anxiety: Training a Singing Teacher to Use Acceptance and Commitment Coaching With a Student. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, A. Testing the Effects of Mindfulness Meditation in Reducing Music Performance Anxiety as Measured by Cortisol and Self-Report. Honor. Program Theses 2020, 412, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Ryan, L. Music Performance Anxiety: Can Expressive Writing Intervention Help? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tief, V.J.; Gröpel, P. Pre-Performance Routines for Music Students: An Experimental Pilot Study. Psychol. Music 2021, 49, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, F.J.; Suárez-Falcón, J.C. The Spanish Version of the Believability of Anxious Feelings and Thoughts Questionnaire. Psicothema 2014, 26, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Tello, A.; Moreno-Coutiño, A. Escala de Compasión (ECOM) Para Población Mexicana. Psicol. Salud 2018, 29, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahn, C.; Walther, J.-C.; Nusseck, M. The Effectiveness of a Multimodal Concept of Audition Training for Music Students in Coping with Music Performance Anxiety. Psychol. Music 2016, 44, 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Ruiz, A.; Abalo, J.; Madam, A.; Los, M.; Londián, A.; Martín, M.; Torres, F. Validation of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children in Cuban Adolescents. Psicol. Salud 2013, 13, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, F.J.; Suárez-Falcón, J.C.; Riaño-Hernández, D. Psychometric properties of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in Colombian undergraduates. SUMPSIC 2016, 23, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupano-Perugini, M.L.; de la Iglesia, G.; Castro-Solano, A.; Keyes, C.L.M. The Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) in the Argentinean Context: Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Measurement Invariance. Eur. J. Psychol. 2017, 13, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolffs, J.L.; Rogge, R.D.; Wilson, K.G. Disentangling Components of Flexibility via the Hexaflex Model: Development and Validation of the Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory (MPFI). Assessment 2018, 25, 458–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krane, V. The Mental Readiness Form as a Measure of Competitive State Anxiety. Sport Psychol. 1994, 8, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardaciotto, L.; Herbert, J.; Forman, E.; Moitra, E.; Farrow, V. The Assessment of Present-Moment Awareness and Acceptance The Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Assessment 2008, 15, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, L.; Williamon, A. Measuring Distinct Types of Musical Self-Efficacy. Psychol. Music 2011, 39, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoponi, E.; Mari, J.J. Reliability and Factor Structure of the Portuguese Version of Self-Reporting Questionnaire. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 1989, 35, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismero, E. EHS. Escala de Habilidades Sociales; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2000; ISBN 978-84-7174-609-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brugués, A.O. Music Performance Anxiety—Part 2: A Review of Treatment Options. Med. Probl. Perform. Artists 2011, 26, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Lauzurique, M.; Vera Fernández, Y.; Dennis, C.-L.; Rubén Quesada, M.; Álvarez Valdés, G.; Lye, S.; Tamayo-Pérez, V. Prevalence, Incidence, and Persistence of Postpartum Anxiety, Depression, and Comorbidity: A Cohort Study Among Women in Havana Cuba. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2022, 36, E15–E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mora, Á.; López Díaz, R. Rasgos de personalidad y variables asociadas a la ansiedad escénica musical. Ansiedad Estrés 2020, 26, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Fernández, A.; Sánchez-Cabrero, R.; Arigita-García, A.; Mañoso-Pacheco, L.; Pericacho-Gómez, F.J.; Novillo-López, M.Á. Measurement of Different Types of Intelligence (General, Verbal vs. Non-Verbal, Multiple), Academic Performance and Study Habits of Secondary Students at a Music Integrated Centre. Data Brief 2019, 25, 104124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cabrero, R.; Barrientos-Fernández, A.; Arigita-García, A.; Mañoso-Pacheco, L.; Costa-Román, O. Demographic Data, Habits of Use and Personal Impression of the First Generation of Users of Virtual Reality Viewers in Spain. Data Brief 2018, 21, 2651–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian-Quinto, O.R. La Ansiedad en los Estudiantes de Música y Estrategia Para su Mejora. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Educacion, Lima, Peru, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Urruzola, M.V.; Bernaras, E. Aprendizaje musical y ansiedad escénica en edades tempranas: 8–12 años. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2020, 25, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.G.; Díaz, A.; Blak, M.G. Manifestaciones fonoaudiológicas de la ansiedad por performance musical en cantantes solistas y coreutas. Boletín Univ. Mus. Soc. Argent. 2019, 11, 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, M.; Díaz, A.; Blake, M. La autoevaluación como destreza en el músico performer. Rev. Actos 2021, 3, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Zaldumbide, M.A.; Borja-Narváez, D.S. La Ansiedad Escénica en Estudiantes de Música y Sus Métodos de Tratamiento, una Revisión Bibliográfica. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesianase de Quito, Quito, Ecuador, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Publications | Design | Data Collection | Type of Treatment | Control | Duration of Intervention | N (GE/GC) and Participant Profiles | Statistical Contrast Tests Applied | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clarke, O. & Baranoff (2020) [37] (Australia) | Uncontrolled trial. Quasi-experimental within-subject design with pre- and post-treatment measurements. Follow up over three months. | K-MPAI, MPFI-SF DASS, and MHC-SF. Open questions | Group therapy of acceptance and commitment | No control group | Six weeks. One 2 h session per week. | 6 (6/-) University music students in their 1st, 2nd, or 3rd year of studies | Repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) | A significant and sustained reduction in MPA was observed over time (Huynh–Feldt correction F (1.11, 5.58) = 9.48, p = 0.019, partial η 2 = 0.655). |

| Cortés-Hernández et al. (2023) [3] (Mexico) | Uncontrolled trial. Quasi-experimental within-subject design with pre- and post-treatment measurements, without follow up. | IDARE, MAAS, and ECOM | Mindfulness and compassion therapy | No control group | Eight weeks. One 2 h session per week. | 20 (20/-) University music students | McNemar’s Test and the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test | No significant changes in trait and state anxiety or physiological variables. |

| Czajkowski et al. (2022) [38] (United Kingdom) | Uncontrolled trial. Quasi-experimental within-subject design, without follow up. | FFMQ, ad hoc questionnaire MFM, and semi-structured interview | Mindfulness through the MfPAS course | No control group | Eight weeks. Weekly group session of 2–2.5 h. Daily individual practice (Routine) of 40–45 min. | 25 (25/-) University music students | Paired t-tests and related non-parametric samples Wilcoxon | Indirectly reported improved MPA via Mindfulness tests (p < 0.01). Qualitative data showed varied focus on positive effects on MPA symptoms. |

| De Lima-Osorio et al. (2022) [39] (Brazil) | Crossover experimental design applying the double-blind technique to the same subjects. | K-MPAI, SSPS-P, and SRQ-20 | Oxytocin (pharmacological treatment) | Placebo | Two measurement sessions with a distance of 15 to 30 days. | 50 (22/28) Music students and professionals | ANOVA 2 × 2 for crossover trials | Oxytocin improved the cognitive component of MPA (p = 0.06). |

| Fernández- Granados y Bonastre (2021) [24] (Spain) | Uncontrolled trial. Quasi-experimental within-subject design with pre- and post-treatment, without follow up. | Open questions | Psychotherapy, visualization, body awareness, breathing, and relaxation | No control group | Eight sessions over two weeks (Each session lasts 15 min.) | 46 (46/-) Amateurs, beginners, pre-college or university students, and professionals | Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s t-tests | The results were not statistically significant in the Psychological Vulnerability, Specific Thoughts, Motor and Physiological scales overall, but were significant in some items of each scale. |

| Moral-Bofill et. al. (2022) [40] (Spain) | Controlled trial. Mixed experimental design, between-subjects and within-subjects, with pre- and post-treatment measurements, without follow up. | EFIM, KMPAI-E, and SSS | HAMI method. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) exercises, mindfulness, emotional regulation therapy, optimal experience states, and positive psychology | Untreated control group | Not specified. | 62 (28/34) Students in their final year of university and university professors | Structural equation modeling (SEM), repeated measures mixed ANOVA, and Student’s t-test | Intervention significantly decreased MPA (t = 2.64, p = 0.01, d = 0.24), and self-awareness (t = −3.66, p = 0.00, d = 0.70) in the experimental group. |

| Shaw et al. (2020) [41] (United Kingdom) | Uncontrolled trial. Single- subject design. Measurements taken before, at the midpoint, and after the intervention. Follow up after three months. | BAFT, AAQ-2, PHLMS, and K-MPAI | (ACT) acceptance and commitment coaching (version of commitment therapy) | No control group | One introductory session and six 1 h sessions over four months. | 1 (1/-) University musical theater student and professional | Reliable change index | Clinically significant improvements in two ACT-based processes believed to correlate with improved psychological flexibility in previous ACT for MPA psychotherapy research, i.e., acceptance of MPA-related discomfort and defusion from MPA-related thoughts. |

| Shorey (2020) [42] (United States) | Controlled trial. Mixed experimental design, between-subjects and within-subjects, with pre- and post-treatment measurements without follow up. | K-MPAI and FZA-S | Mindfulness, yoga, and other mind–body exercises | Equivalent neutral treatment | A single session. | 16 (8/8) University music students | One-tailed t-test and Regression model | There were no significant improvements in cortisol reactivity or state MPA. |

| Tang & Ryan (2020) [43] (United States) | Controlled trial. Mixed experimental design, between-subjects and within-subjects, with pre- and post-treatment measurements, without follow up. | QSMEEPH and expressive writing | Expressive writing | Equivalent neutral treatment | Two sessions two to three days apart. | 35 (18/17) University music students | Mixed-design ANOVA | Students with high levels of MPA significantly reduced it (F = 4.99, p < 0.04). |

| Tief & Gröpel (2021) [44] (Austria) | Controlled trial. Mixed experimental design, between-subjects and within-subjects, with pre- and post-treatment measurements, without follow up. | K-MPAI, MRF-3, and SMPQ | Pre-concert routines (goal setting system = control group) | Active comparator (a goal setting system applied to control group) | Two sessions 33 days apart. | 30 (15/15) Music students and professionals | 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA and chi-square test | There were no significant differences observed in MPA in either of the two intervention techniques. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gómez-López, B.; Sánchez-Cabrero, R. Current Trends in Music Performance Anxiety Intervention. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090720

Gómez-López B, Sánchez-Cabrero R. Current Trends in Music Performance Anxiety Intervention. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(9):720. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090720

Chicago/Turabian StyleGómez-López, Belén, and Roberto Sánchez-Cabrero. 2023. "Current Trends in Music Performance Anxiety Intervention" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 9: 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090720

APA StyleGómez-López, B., & Sánchez-Cabrero, R. (2023). Current Trends in Music Performance Anxiety Intervention. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090720