Exploring the Lived Experience on Recovery from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) among Women Survivors and Five CHIME Concepts: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

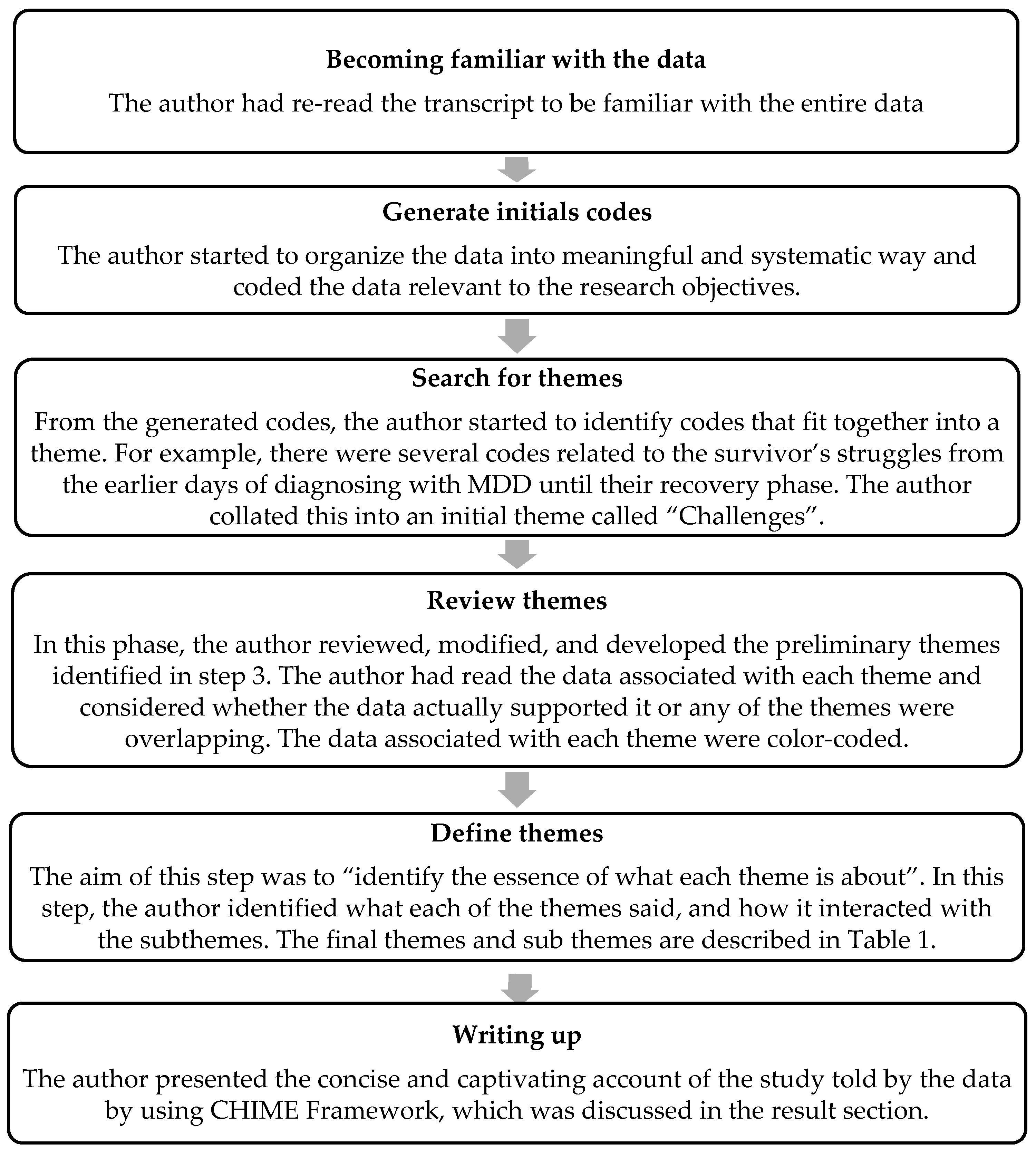

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Demography of Informants

- (a)

- Connectedness

- i.

- Social support

- (i)

- Good care by the caregiver

After I gave birth to my first child, I had post-partum depression. I could feel that I did not like my baby. I felt like it’s hard to take care of the baby. I used to rage, I hit my husband, I kicked him. That’s not normal right? Usually, I raged when my parents were asleep. So, my husband was the one who saw my true colors.

I should have been hospitalized. But, because the bed was full, and I had a baby to breastfeed, on my husband’s assurance, I took a very high dose of medicine, and I was like a living corpse for two weeks at home. I just slept all the time. During that time, my husband was a very tired person. Before he went to work, he would prepare the breakfast. At 10 o’clock in the morning, he would come back to bathe the kids and go back to work. At 12 o’clock, he would buy lunch and send to us. At 5 o’clock, he would buy food for dinner, bathe and take care of the kids. I just lied down. Slept.

Although I have been hospitalized, my brother would come every day. He would come to bring the food, and I would eat with him with his wife and his children. That was his routine every day. Only then, he could sleep after seeing me. He also gave some conditions to the ward if they wanted to detain me. He told the doctor and nurses to bathe and feed me every day, just like how he would take care of me at home.

- (ii)

- Support from other family members

My brother, he’s more silent. Because yeah, man… he doesn’t have many things to say. So, when we meet, we chat as usual. But my sister, maybe because… I am the only sister, when those things went viral (Mrs. R’s sharing about her illness on Facebook), my sister was so shocked, but she did not condemn.

So since then, she has given a lot of support. I started selling biscuits. At that time, I was pregnant and living on the 4th floor of apartment. My sister will help me pick up the biscuits, take order from her officemate, and help me with sales. Not only that, when I did an online class (teach photography), she would be in that group. She would ask a lot even though she knew the answers already.

There were many places that we went. It’s a bit tense for me. Because when we met the ustaz (Islamic named for Muslim faith healer), he would judge me and tell me to stop taking the medicine. So, that added more pressure.

- (iii)

- Indirect assistance from others

There was one time when I shared a room with Mrs. W (her friend from the support group). Mrs. W has already slept that night. But, I couldn’t. I cried and sobbed. It was 3–4 o’clock in the morning. Mrs. W then realized that I was crying. She then asked, “M, why are you crying? Are you sick?”. Then I said, “No. I’m ok”. Then, Mrs. W asked, “Is there anything you want to share with me?” Those questions were like a medicine for me. I felt relieved.

Sometimes, if I felt uncomfortable in class, I would go to the counselling room. She (Counsellor) would tell my teacher about my conditions. She explained to the teacher that I couldn’t study like other students.

The counsellor sometimes messaged my mom to ask about me.

- (b)

- Hope and optimism

- ii.

- Hope

- (i)

- Expectation to self

My hope is one day I could speak in front of many people like in Ted Talk. I have that vision. But I realized, my biggest anxiety right now is speaking English. I can speak English, but with broken grammar.

I hope I can go to the international stage, not only talking about awareness, but also serving the community since it is my life satisfaction.

And my dream is, one day I can live just like a normal human being and benefit others. Hopefully, when I die later, there is something I can leave behind. Wow, how big is that dream! (laugh).

I want to socialize with others. Making new friends. For now, I feel stress whenever I need to go out, meeting other people. I hope I can overcome this in future.

- (ii)

- Expectations of family

Before this, there were those who felt the stress of taking care of me. But, of all their sacrifices, I hope they will feel blessed, just like how I feel. I hope by taking care of me, they know that God has taught them something. “There have been many favors and lessons I got by taking care of my sister.”

I hope one day they will understand my illness. It was not that I was lazy to do certain things when we gathered at my in-laws. But sometimes, there was something that triggered me. I could sense that my mental health would be affected. So, I decided to stay inside the room to calm my emotions. I hope one day my in-laws will better understand the symptoms of MDD.

- (iii)

- Expectations of the community

The stigma from people who think that they are healthy, rich, and knowledgeable. Hence, these people are lacking empathy.

It is the stigma that actually worsens the patient’s conditions.

- (iv)

- Expectations of healthcare workers and service providers

I think the role of psychology students or other people who have the skills in these things are to do the therapy sessions, where patients can come and enjoy the therapy. For example, I have seen a counsellor who does art therapy. Patients will go there and do the art. And the counsellor will then try to tell the story from the art. For example, if the patients use a lot of dark color, maybe they are currently depressed about something.

Patients need therapy. Examples in terms of Qur’anic verses.

- (c)

- Identity

- iii.

- Survivor efforts

- (i)

- Help from health services

I had four appointments. First, I was given the DASS test. Then, it was massage therapy. Then, there was aromatherapy. Then, the last time I remember, the therapist told me to lie down, the lights were dimmed, music was played, I heard a sound of waterfall, the sounds of birds… From there I understood how the grounding technique worked. We need to focus on the surrounding, not what is on our mind.

Hospital medicines are more helpful than traditional medicines.

I went to therapy at four different places. Two at government hospitals, one at a private hospital, and another one at university’s hospital.

For example, if we are having panic attack, the therapist taught us to do deep breathing.

- (ii)

- Completing one task at a time

Honestly, if I say it all, people will feel heavy. Like myself, as a patient, if I listen to a talk, and that individual tell me to take care of everything, I feel like… I can’t. Because I once went through a phase of depression that made me feel lazy. So, I learnt to do one by one.

As a patient who has experienced a phase of feeling lazy to live, my advice is try to settle one by one. Like me, I learn by getting up early. When I could get up in the morning, I learned to set small goals. Then, I learned to cook. At first, I tried to cook one dish only. Then, I tried to cook rice with fried fish for example. When I saw everyone eats, I felt happy. Only after that I learned to add dishes. So, when I was able to wake up early in the morning, I learned to do other things too.

During the latest relapse, I couldn’t really afford to do anything. It’s just that God gave me the power to do what I liked to do before. For example, I have learned about 99 names of Allah. But I only remember one name (during relapse). So, I recited it the whole time. I couldn’t afford to get up, but it’s ok. I just recited it while lying down.

- (iii)

- Taking care of the food intakes, sleep and emotions

You have to take care of the daily nutrition and sleep. People are always taking easy about sleep. Need to keep track of screen time as well.

No problem (if forget to take medicine). You got to take care of your emotions and food intake (nutrition) and have enough sleep. That’s all.

- (d)

- Meaning

- (i)

- Good coping skills

Writing had helped me deleting bad memories in my brain. When I did the writings, it seemed to help remove the unwanted things that I did not want to remember, and those things made my brain feel free.

I don’t want people to take many years to get help like me. I know that I’m sick, but I denied it. I got married, and had post-partum depression. I’ve beaten my children to the point of wanting to drown my children. I don’t want people to feel the bad things I’ve been through them. That’s why I wrote.

I listen to songs… I clean the house…

- (e)

- Empowerment

- iv.

- Challenges

- (i)

- Acceptance of family members

My mother said, when I got an invitation to go live on television and talk about my depression, my father’s side started to talk about me on their WhatsApp group. My mother told me that she had never seen my father look very sad. Not long after that, he got a call from his sibling. They said, “what are you doing with your daughter? You don’t know how to take care of your children.”

So, one day my mom came to my house. We both hugged and apologized. And I think the main core that made me depressed was gone. And my health is getting better after that. (crying).

For example, my siblings may understand, but not my uncles and aunties. They don’t understand until now. They still believe in the ‘saka’ thing. So, this thing cannot be solved if they still believe in the mystics.

- (ii)

- Social stigma

There is no cure for this disease (laugh).

People say depression happens because we don’t pray. Many people feel that this thing (depression) does not exist.

Like me… I’ve been through these many times… For example, in the previous relapse, I went to XXX clinic. There, the staff asked me, “Are you not praying? If not, why are you feel like committing suicide, right?” So, I feel like the staff themselves need to be educated.

- (iii)

- Struggle against self-stigma

It’s just the hardest when… for me, when I started to feel better and see the rhythm of wanting to be healthy, but then, I felt I was a loser. I spend much time on Facebook (doing sharing), but sometimes I will indirectly judge and differentiate myself from others. As a result, it affects my mental health.

I feel like I want to close (Facebook). But at the same time, I have a responsibility to society. My way of helping and educating is by sharing. If I deactivate my Facebook, all my writing will be lost.

The stigma that said we’re crazy. We can’t recover. No one else is sick like me. It’s only me.

I feel like… crazy… I remember I was very sensitive… Apparently what I felt… was a disease…

- (iv)

- Challenges of starting a new life

Frankly speaking, I wanted to go out to work, but I did not know what to do. For example, when I got an invitation to something, it’s actually my husband who took care most of the things. My husband is the one who encourages me, especially in terms of technical support.

Because I used to be in a phase where I did not want to do anything in life (when relapse), now I’m learning to take responsibility. But I do not dare to do many things at once.

It was my husband who taught me to look for solutions, not problems. But, it took me three years to finally taught my brain to always think about solutions whenever problems occurred.

4. Discussion—Key Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albert, P.R. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. Can. Med. Assoc. 2015, 40, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Suicide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Bradvik, L. Suicide Risk and Mental Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, E.A.; Mengistu, B.T.; Engidaw, N.A.; Wubetu, A.D.; Haile, A.B. Suicidal Ideation and Its Associated Factors Among Patients with Major Depressive Disorder at Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 1571–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanzar, S.; Shah, N.; Vithalani, S.; Shah, S.; Squires, J.; Appasani, R.; Katz, C.L. Knowledge of and Attitudes toward Clinical Depression among Health Providers in Gujarat, India. Ann. Glob. Health 2014, 80, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Bruffaerts, R.; Chiu, W.T.; Florescu, S.; de Girolamo, G.; Gureje, O.; et al. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1560–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.L.; Hutagalung, F.D.; Lau, P.L. A Review of Depression and Its Research Studies in Malaysia. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Couns. 2017, 2, 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, N.G. A Review of Depression Research in Malaysia. Med. J. Malays. 2014, 69, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- VanPraag, H.M. Can stress cause depression? World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 6, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Saadah, M.A.; Noremy, M. Empowering Informal Caregivers and Care for Family. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 444–452. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Suhaimi, M.; Fatimah, A.; Farid, M.Z. Empowering Informal Caregivers Across Gender. Humanisma J. Gend. Stud. 2018, 2, 172–188. [Google Scholar]

- Siti Marziah, Z.; Nurul Shafini, S.; Noremy, M.A.; Suzana, M.H.; Jamiah, M. Cabaran Hidup Ibu Tunggal: Kesan Terhadap Kesejahteraan Emosi. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Couns. 2019, 4, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbo, F.A.; Mathsyaraja, S.; Koti, R.K.; Perz, J.; Page, A. The burden of depressive disorders in South Asia, 1990-2016: Findings from the global burden of disease study 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1103 Clinical Sciences. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, K.M.; Rossi, F.S.; Nillni, Y.I.; Fox, A.B.; Galovski, T.E. PTSD and Depression Symptoms Increase Women’s Risk for Experiencing Future Intimate Partner Violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, L.; Happell, B.; Reid-Searl, K. Recovery as a lived experience discipline: A grounded theory study. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 36, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, J.Y.K.; Wong, V.; Ho, G.W.K.; Molassiotis, A. Understanding the experiences of hikikomori through the lens of the CHIME framework: Connectedness, hope and optimism, identity, meaning in life, and empowerment; systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brijnath, B. Applying the CHIME recovery framework in two culturally diverse Australian communities: Qualitative results. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo, R.R.; Vinat, V.; Bahari, R.; Chauhan, S.; Deborah, A.F.M.; Stephanie, N.F.; Johnson, C.C.P.; Agkesh Qumar, T.; Rahman, M.M.; Goel, S. Depression and anxiety in Malaysian population during third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 12, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader Maideen, S.F.; Mohd Sidik, S.; Rampal, L.; Mukhtar, F. Prevalence, associated factors and predictors of depression among adults in the community of Selangor, Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M.; Obrosky, S.; George, C. The course of major depressive disorder from childhood to young adulthood: Recovery and recurrence in a longitudinal observational study. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 203, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifah, I.; Noremy, M.A. The impacts of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on caregivers of family members with mental health issues: The untold story. Malays. J. Soc. Space 2022, 18, 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Barkham, M. Recovery from depression: A systematic review of perceptions and associated factors. J. Ment. Health 2017, 29, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piat, M.; Seida, K.; Sabetti, J. Understanding everyday life and mental health recovery through CHIME. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2017, 21, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.; de Medeiros, A.G.A.P.; Rolim, C.; Pinheiro, K.S.C.B.; Beilfuss, M.; Leão, M.; Castro, T.; Junior, J.A.S.H. Hope Theory and Its Relation to Depression: A Systematic Review. Ann. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, V.; Leamy, M.; Tew, J.; le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Fit for purpose? Validation of a conceptual framework for personal recovery with current mental health consumers. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favale, D.; Bellomo, A.; Bradascio, C.; Ventriglio, A. Role of Hope and Resilience in the Outcome of Depression and Related Suicidality. Psychology 2020, 11, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, S.P.; Agustin, M.; Wijayanti, D.Y.; Sarjana, W.; Afrikhah, U.; Choe, K. Mediating Effect of Hope on the Relationship Between Depression and Recovery in Persons with Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 627588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, A.; Stylianidis, S.; Issari, P.; Chondros, P.; Alexiadou, A.; Belekou, P.; Giannou, C.; Karali, E.K.; Foi, V.; Tzaferou, F. Experiences of Recovery in EPAPSY’s Community Residential Facilities and the Five CHIME Concepts: A Qualitative Inquiry. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, S.R.; Tansey, L.; Quayle, E. What we talk about when we talk about recovery: A systematic review and best-fit framework synthesis of qualitative literature. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsgaard, J.B.; Jensen, A. Music activities and mental health recovery: Service users’ perspectives presented in the chime framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørjasæter, K.B.; Davidson, L.; Hedlund, M.; Bjerkeset, O.; Ness, O. “I now have a life!” Lived experiences of participation in music and theater in a mental health hospital. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrudin, S.; Fatin Nabihah, O.; Mohd Suhaimi, M. Stress and Coping Strategies of Trainee Counsellors during COVID-19 Movement Control Order. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 958–968. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, P.; Stanhope, V. Recovery: Expanding the vision of evidence-based practice. Brief Treat. Crisis Interv. 2004, 4, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, W.A. Recovery from Mental Illness: The Guiding Vision of the Mental Health Service System in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 1993, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; Hording, C.; Larsen, J.; Boutillier, C.L.E.; Oades, L.; Slade, M. Measures of the recovery orientation of mental health services: Systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 1827–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdisa, E.; Fekadu, G.; Girma, S.; Shibiru, T.; Tilahun, T.; Mohamed, H.; Wakgari, A.; Takele, A.; Abebe, M.; Tsegaye, R. Self-stigma and medication adherence among patients with mental illness treated at Jimma University Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teferra, S.; Hanlon, C.; Beyero, T.; Jacobsson, L.; Shibre, T. Perspectives on reasons for non-adherence to medication in persons with schizophrenia in Ethiopia: A qualitative study of patients, caregivers and health workers. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Camacho, D.; Kimberly, L.L.; Lukens, E.P. Women’s Experiences and Perceptions of Depression in India: A Metaethnography. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 29, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa DaSilva, M.A.R.; Margareth, A. Experiences and meanings of post-partum depression in women in the family context. Enferm. Glob. 2016, 42, 280–302. [Google Scholar]

- Zender, R.; Olshansky, E. Women’s Mental Health: Depression and Anxiety. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 2009, 44, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emslie, C.; Ridge, D.; Ziebland, S.; Hunt, K. Exploring men’s and women’s experiences of depression and engagement with health professionals: More similarities than differences? A qualitative interview study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2007, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schon, U.K. How men and women in recovery give meaning to severe mental illness. J. Ment. Health 2009, 18, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subordinate Themes | Themes |

|---|---|

| Good coping skills | |

| Getting help from health services | |

| Completing one task at a time | |

| Taking care of the food intakes, sleep, and emotions | Survivor efforts |

| Acceptance by family members | |

| Social stigma | |

| Struggle against self-stigma | Challenges |

| Challenges of starting a new life | |

| Good care by the caregiver | |

| Support from other family members | Social Support |

| Indirect assistance from others | |

| Expectation for self | |

| Expectation for family | |

| Expectation for community | |

| Expectation for health care workers and service providers | Hope |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Idris, A.; Md Akhir, N.; Mohamad, M.S.; Sarnon, N. Exploring the Lived Experience on Recovery from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) among Women Survivors and Five CHIME Concepts: A Qualitative Study. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020151

Idris A, Md Akhir N, Mohamad MS, Sarnon N. Exploring the Lived Experience on Recovery from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) among Women Survivors and Five CHIME Concepts: A Qualitative Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(2):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020151

Chicago/Turabian StyleIdris, Afifah, Noremy Md Akhir, Mohd Suhaimi Mohamad, and Norulhuda Sarnon. 2023. "Exploring the Lived Experience on Recovery from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) among Women Survivors and Five CHIME Concepts: A Qualitative Study" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 2: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020151

APA StyleIdris, A., Md Akhir, N., Mohamad, M. S., & Sarnon, N. (2023). Exploring the Lived Experience on Recovery from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) among Women Survivors and Five CHIME Concepts: A Qualitative Study. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020151