Exposure to the Death of Others during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Growing Mistrust in Medical Institutions as a Result of Personal Loss

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Procedures and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

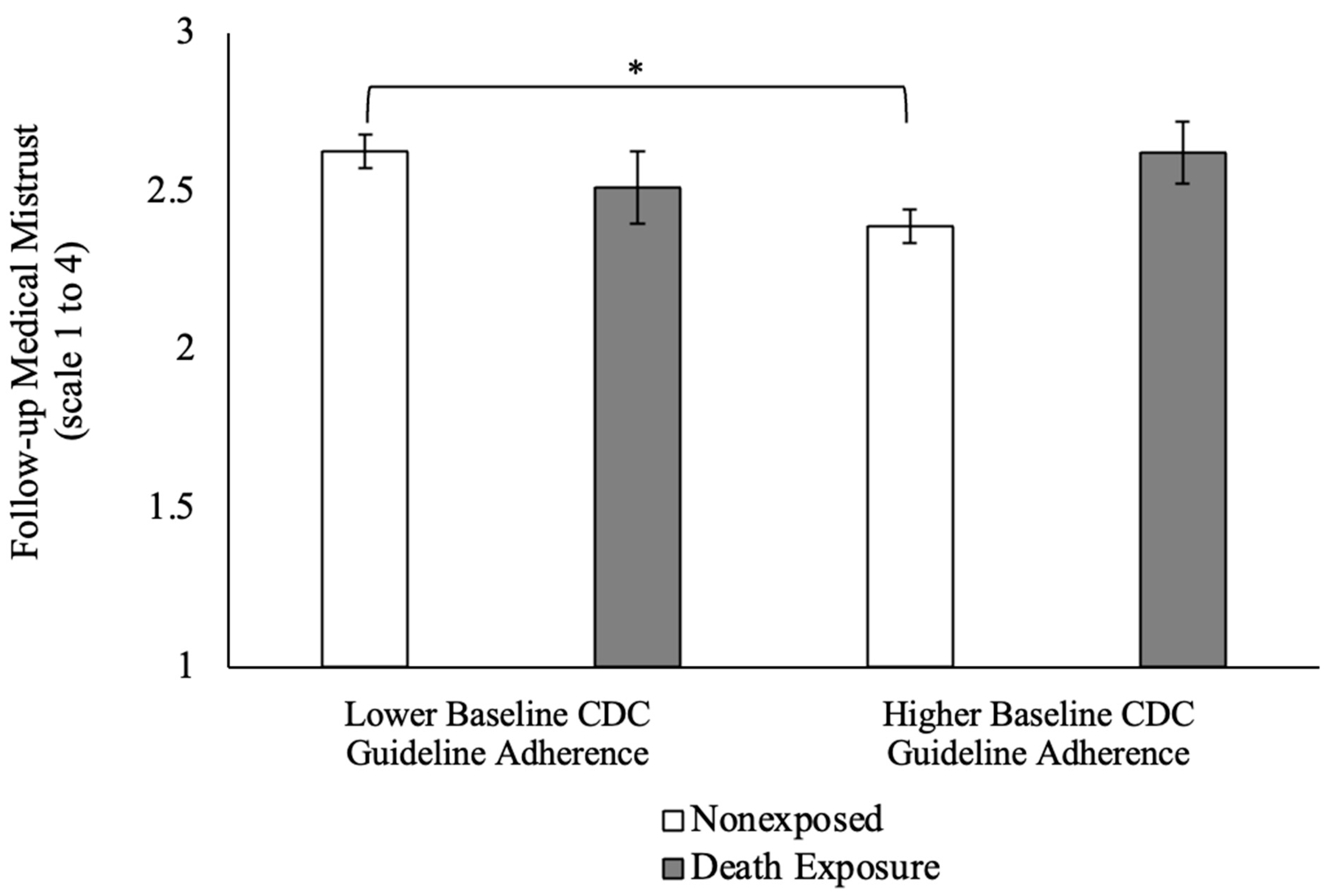

4.1. Interaction Effect of Death Exposure and CDC Adherence on Medical Mistrust

4.2. Main Effects of Death Exposure on Safety Measures

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bogoch, I.I.; Watts, A.; Thomas-Bachli, A.; Huber, C.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Khan, K. Potential for global spread of a novel coronavirus from China. J. Travel. Med. 2020, 27, taaa011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallapaty, S. Why does the coronavirus spread so easily between people? Nature 2020, 579, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Rahman, K.M.; Sun, Y.; Qureshi, M.O.; Abdi, I.; Chughtai, A.A.; Seale, H. Current knowledge of COVID-19 and infection prevention and control strategies in healthcare settings: A global analysis. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.L.; Russell, B.S.; Fendrich, M.; Finkelstein-Fox, L.; Hutchison, M.; Becker, J. Americans’ COVID-19 Stress, Coping, and Adherence to CDC Guidelines. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 2296–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batova, T. To wear or not to wear: A commentary on mistrust in public comments to CDC tweets about mask-wearing during COVID-19. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2022, 59, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, S.H.; Chapman, D.A.; Lee, J.H. COVID-19 as the Leading Cause of Death in the United States. JAMA 2021, 325, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Rai, M. Social isolation in COVID-19: The impact of loneliness. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.; Panagopoulos, C.; van der Linden, S. Political polarization on COVID-19 pandemic response in the United States. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 179, 110892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.W.; Zvolensky, M.J.; Long, L.J.; Rogers, A.H.; Garey, L. The Impact of COVID-19 Experiences and Associated Stress on Anxiety, Depression, and Functional Impairment in American Adults. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2020, 44, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, B.L.; Martens, A.; Faucher, E.H. Two decades of terror management theory: A meta-analysis of mortality salience research. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 14, 155–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Shaver, P.R.; Goldenberg, J.L. Attachment, self-esteem, worldviews, and terror management: Evidence for a tripartite security system. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyszczynski, T.; Greenberg, J.; Solomon, S. A dual-process model of defense against conscious and unconscious death-related thoughts: An extension of terror management theory. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, A.; Malik, M.; Raees, V.; Anwar, A. Role of Mass Media and Public Health Communications in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cureus 2020, 12, e10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, J.; Pyszczynski, T.; Solomon, S.; Simon, L.; Breus, M. Role of consciousness and accessibility of death-related thoughts in mortality salience effects. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeichel, B.J.; Gailliot, M.T.; Filardo, E.A.; McGregor, I.; Gitter, S.; Baumeister, R.F. Terror management theory and self-esteem revisited: The roles of implicit and explicit self-esteem in mortality salience effects. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeyta, A.A.; Juhl, J.; Routledge, C. Exploring the effects of self-esteem and mortality salience on proximal and distally measured death-anxiety: A further test of the dual process model of terror management. Motiv. Emot. 2014, 38, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyszczynski, T.; Greenberg, J.; Solomon, S.; Arndt, J.; Schimel, J. Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 435–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyszczynski, T.; Solomon, S.; Greenberg, J. Thirty years of terror management theory: From genesis to revelation. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Volume 52, pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsubo, K.; Yamaguchi, H. No significant effect of mortality salience on unconscious ethnic bias among the Japanese. BMC Res. Notes 2023, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Merle, P. Terror management and civic engagement. J. Media Psychol. 2013, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, J.L.; Arndt, J. The implications of death for health: A terror management health model for behavioral health promotion. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 115, 1032–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Winzeler, S.; Topolinski, S. When the death makes you smoke: A terror management perspective on the effectiveness of cigarette on-pack warnings. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 46, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, R.E.; Forrester, M.; Sharpe, L. Starving off death: The effect of mortality salience on disordered eating in women. PsyArXiv Prepr. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, J.L.; Pyszczynski, T.; Greenberg, J.; Solomon, S. Fleeing the body: A terror management perspective on the problem of human corporeality. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 4, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyszczynski, T.; Lockett, M.; Greenberg, J.; Solomon, S. Terror management theory and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2021, 61, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.G.; Gadarian, S.K.; Goodman, S.W.; Pepinsky, T.B. Morbid Polarization: Exposure to COVID-19 and Partisan Disagreement about Pandemic Response. Political Psychol. 2022, 43, 1169–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, B.L.; Kosloff, S.; Landau, M.J. Death goes to the polls: A meta-analysis of mortality salience effects on political attitudes. Political Psychol. 2013, 34, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatard, A.; Arndt, J.; Pyszczynski, T. Loss shapes political views? Terror management, political ideology, and the death of close others. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 32, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifshin, U.; Helm, P.J.; Greenberg, J.; Soenke, M.; Ashish, D.; Sullivan, D. Managing the death of close others: Evidence of higher valuing of ingroup identity in young adults who have experienced the death of a close other. Self Identity 2017, 16, 580–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadarian, S.K.; Goodman, S.W.; Pepinsky, T. Racial resentment and support for COVID-19 travel bans in the United States. Political Sci. Res. Methods 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnig, M.A.; Padovano, H.T.; Sokolovsky, A.W.; DeCost, G.; Aston, E.R.; Haass-Koffler, C.L.; Szapary, C.; Moyo, P.; Avila, J.C.; Tidey, J.W. Association of substance use with behavioral adherence to centers for disease control and prevention guidelines for COVID-19 mitigation: Cross-sectional web-based survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e29319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Eaton, L.A.; Kalichman, S.C.; Brousseau, N.M.; Hill, E.C.; Fox, A.B. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaVeist, T.A.; Isaac, L.A.; Williams, K.P. Mistrust of health care organizations is associated with underutilization of health services. Health Serv. Res. 2009, 44, 2093–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, K.M.; Maglalang, D.D.; Monnig, M.A.; Ahluwalia, J.S.; Avila, J.C.; Sokolovsky, A.W. Medical mistrust, perceived discrimination, and race: A longitudinal analysis of predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in US adults. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 1846–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shieh, G. Detecting interaction effects in moderated multiple regression with continuous variables power and sample size considerations. Organ. Res. Methods 2009, 12, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimoff, J.D.; Dao, A.N.; Mitchell, J.; Olson, A. Live free and die: Expanding the terror management health model for pandemics to account for psychological reactance. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass. 2021, 15, e12585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, G.; Gangl, K.; Van Prooijen, J.W.; Van Lange, P.A.M.; Mosso, C.O. Enhancing feelings of security: How institutional trust promotes interpersonal trust. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. COVID Data Tracker; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Shrout, P.E.; Rodgers, J.L. Psychology, Science, and Knowledge Construction: Broadening Perspectives from the Replication Crisis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.A.; Cook, C.L.; Ebersole, C.R.; Vitiello, C.; Nosek, B.A.; Hilgard, J.; Ahn, P.H.; Brady, A.J.; Chartier, C.R.; Christopherson, C.D. Many Labs 4: Failure to replicate mortality salience effect with and without original author involvement. Collabra Psychol. 2022, 8, 35271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatard, A.; Hirschberger, G.; Pyszczynski, T. A word of caution about Many Labs 4: If you fail to follow your preregistered plan, you may fail to find a real effect. PsyArXiv Prepr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Benjamin, R.; Lai, A.; Heine, S. Managing the terror of publication bias: A comprehensive p-curve analysis of the Terror Management Theory literature. PsyArXiv Prepr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treger, S.; Benau, E.M.; Timko, C.A. Not so terrifying after all? A set of failed replications of the mortality salience effects of Terror Management Theory. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, S.; Hilgard, J.; Fritsche, I.; Burke, B.; Pfattheicher, S. Do salient social norms moderate mortality salience effects? A (challenging) meta-analysis of terror management studies. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 27, 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Covid Public Policy | Vaccination Status(Logistic) | CDC Guideline Adherence | Medical Mistrust | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Age | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.00 (.000) | −0.00 (0.00) |

| Gender | 0.09 (0.10) | −0.32 (0.29) | 0.22 (0.07) * | −0.02 (0.06) |

| Race | 0.13 (0.11) | −0.61 (0.33) | 0.10 (0.08) | 0.18 (0.08) |

| Ethnicity | −0.26 (0.15) | −0.71 (0.43) | −0.03 (0.11) | 0.05 (0.10) |

| Socioeconomic status | −0.06 (0.03) * | 0.31 (0.08) ** | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.06 (0.02) * |

| Perceived discrimination | −0.09 (0.05) | −0.14 (0.14) | −0.06 (0.04) | 0.98 (0.03) * |

| Death exposure | 0.24 (0.12) * | 0.92 (0.41) * | 0.17 (0.08) * | 0.03 (0.08) |

| F-value (7, 275)/chi-square | 2.66 * | 30.41 ** | 3.25 * | 5.05 ** |

| Variance explained (R²) | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gully, B.J.; Padovano, H.T.; Clark, S.E.; Muro, G.J.; Monnig, M.A. Exposure to the Death of Others during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Growing Mistrust in Medical Institutions as a Result of Personal Loss. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120999

Gully BJ, Padovano HT, Clark SE, Muro GJ, Monnig MA. Exposure to the Death of Others during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Growing Mistrust in Medical Institutions as a Result of Personal Loss. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(12):999. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120999

Chicago/Turabian StyleGully, Brian J., Hayley Treloar Padovano, Samantha E. Clark, Gabriel J. Muro, and Mollie A. Monnig. 2023. "Exposure to the Death of Others during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Growing Mistrust in Medical Institutions as a Result of Personal Loss" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 12: 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120999

APA StyleGully, B. J., Padovano, H. T., Clark, S. E., Muro, G. J., & Monnig, M. A. (2023). Exposure to the Death of Others during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Growing Mistrust in Medical Institutions as a Result of Personal Loss. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120999