Abstract

Background/Objective: The rising prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), coupled with sedentary behavior and an increase in obesity rates in South Asian countries, calls for effective management strategies. We aimed to assess the efficacy of lifestyle interventions on glycemic control among adults with T2DM in South Asian countries. Methods: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were conducted to assess the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions on glycemic control in adults diagnosed with T2DM in South Asia. We conducted a comprehensive search in CINAHL, Embase, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science (WoS), and Scopus to identify related studies published from 2000 to 13 June 2024. We assessed the risk of bias using the ROB 2.0 tool and calculated the pooled mean differences in HbA1c and FBG levels under a random-effects model. We conducted subgroup and leave-one-out sensitivity analyses to assess and explore sources of heterogeneity. PROSPERO Registration: CRD42024552286. Results: We included 16 RCTs with a total of 1499 participants. Lifestyle interventions reduced HbA1c levels by 0.86% (95% CI: −1.30 to −0.42, p < 0.01) and FBG levels by 22.49 mg/dL (95% CI: −32.88 to −12.10, p < 0.01). We observed substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 98% for HbA1c and I2 = 87% for FBG). Subgroup analyses indicated larger HbA1c reductions in long-term (−1.44%) than short-term trials (−0.62%), and greater FBG decreases in long-term (−23.7 mg/dL) versus short-term studies (−22.5 mg/dL). Physical activity interventions had the largest improvements (HbA1c −0.99%; FBG −26.1 mg/dL), followed by dietary (HbA1c −0.59%; FBG −15.8 mg/dL) and combined programs (HbA1c −0.55%). Participants aged >50 years achieved greater glycemic improvements (HbA1c −0.92%; FBG −24.0 mg/dL) compared to younger adults (HbA1c −0.60%; FBG −21.3 mg/dL). Despite high heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the overall findings. Conclusions: Lifestyle modifications yielded a clinically significant reduction in HbA1c and FBG in adults with T2DM in South Asia. Although heterogeneity of the included studies was substantial, the direction of the effects was uniformly consistent across subgroups. To further validate these findings and assess their long-term effects, large-scale and standardized RCTs conducted for longer durations are necessary.

1. Introduction

Globally, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) continues to rank among the most prevalent noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), affecting people across all age groups and genders [1]. According to the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas (11th Edition, 2025), T2DM and its complications contributed to an estimated 3.4 million deaths worldwide in 2024. indicating its substantial and growing contribution to global mortality [2]. In the South Asian populations, this burden is even greater due to genetic susceptibility and rapidly evolving lifestyle patterns [3]. Lifestyle changes play an important role in both the management and prevention of T2DM. Evidence shows that lifestyle interventions can bring down the T2DM incidence by 58% in high-risk groups of the population [4] and are effective across diverse racial and ethnic groups [5]. Key components like exercise and physical activity have been shown to play a vital role in improving glycemic control by lowering Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) and fasting blood glucose (FBG), among other health metrics [6].

The prevalence of T2DM in South Asia is mainly influenced by urbanization and a shift to a sedentary lifestyle, as well as a rapid dietary transition [7]. This shift includes a reduced consumption of coarse cereals, vegetables, and fruits, along with an increased carbohydrate intake [8,9]. The combination of low fiber, high glycemic index, and saturated fat in the diet contributes to poor glycemic control [10]. Personalized dietary interventions demonstrated significant improvements in HbA1c and FBG levels, highlighting the significance of individualized dietary management and nutrition education [11].

In spite of such established benefits, lifestyle changes are not consistently part of diabetes management in South Asia [12]. Because of this, many patients do not meet recommended treatment targets for HbA1c, blood pressure, or lipids [13]. The majority of studies on lifestyle interventions have focused on South Asians who are living abroad. However, diabetes management is shaped by more than genetic predisposition; it is also influenced by country-specific socio-economic, nutritional, and cultural factors [14], which makes it challenging to apply existing research findings. Although lifestyle modifications and dietary changes have shown effective results on glycemic control, the specific impact of these interventions in South Asian populations, where the burden of T2DM is particularly high, has not been fully established. Given the unique challenges in this region, more research is needed to determine the effectiveness of these interventions in South Asia. Therefore, we aimed to systematically review, assess, and consolidate evidence on lifestyle modifications, physical activity, dietary changes, or a combination of both to improve glycemic control among South Asian adults with T2DM.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs that quantified the impact of lifestyle modification interventions on glycemic control among patients with T2DM in South Asia. This review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO 2024 CRD42024552286) and conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines [15,16].

2.1. Search Strategy

We conducted a comprehensive database search to identify relevant studies published between 1 January 2000 and 13 June 2024 across CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane Library, PubMed, Web of Science (WoS), and Scopus. We used the following keywords: (Exercise OR Diet OR Lifestyle OR “Lifestyle Interventions”) and (Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Bhutan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Maldives, South Asia) and Type 2 Diabetes. Appropriate Mesh terms and subject headings were used in search queries. We applied filters to refine the search, focusing on study design, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), English language, and free full-text access. In addition, references and citations of all eligible studies were searched. A detailed search strategy for each database can be found in [Supplementary Tables S1–S6].

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Records from all the databases were combined, and duplicate titles were removed using EndNote 21 [17]. Two reviewers (IA and GP) independently screened titles and abstracts, and subsequently retrieved full texts to assess the eligibility for inclusion. We resolved the disagreements about eligibility through discussion, and consensus was reached in all cases. Two reviewers independently extracted the following information from the finally selected papers: author, study type, study location, length of the study, and characteristics of the participants (sample size, age, and gender) in the intervention group and control group. The type of intervention, post-intervention mean values, and standard deviations were also extracted.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if (a) it was conducted among adults aged 18 years and older in South Asia who were clinically diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; (b) the study design was RCTs with a comparison group (e.g., standard care, no intervention); (c) lifestyle interventions that consist of structured and planned programs involving dietary modification, physical activity, or a combination of both; and (d) the outcome was HbA1c levels or fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels. However, studies were excluded if they involved participants under 18 years of age, individuals without a T2DM diagnosis, or pregnant or lactating women. In addition, we excluded the studies if they were not written in English, conducted on non-human populations, or published as conference abstracts, review articles, opinion pieces, or letters to the editor.

2.4. Outcomes

The outcome of interest was the change in glycemic control, as measured by HbA1c (%) (Glycated Hemoglobin) or fasting blood glucose (FBG) (mg/dL).

2.5. Risk of Bias

One author (I.A) assessed the risk of bias, and a second author (G.V.p) reviewed it using the RoB 2.0 tool by Cochrane [18]. This assessment considered aspects such as bias arising from the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result

Each domain was rated as low risk of bias, high risk of bias, and some concerns. As specified in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews to assess the risk of bias [19], if we determine that any of the domains has a high risk of bias in a trial, then the overall risk of bias is considered high. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

2.6. Effect Sizes

The effect size of interest was the mean difference (MD). We extracted post-intervention data on HbA1c and/or FBG. We extracted the mean and standard deviation (SD) for the HbA1c or FBG values in both the intervention and control groups. The ESs were estimated using the MD of post-intervention HbA1c/FBG values in both intervention and control groups.

2.7. Data Analysis

A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the pooled mean difference for two clinical outcomes—HbA1c and FBG. We assessed the level of heterogeneity (I2 statistic) between studies. We also conducted subgroup analyses based on duration of intervention, participants’ age, and type of lifestyle modification: dietary, physical activity, and combined (both physical activity and dietary). We performed a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis to explore the influence of each included study on the pooled ES. We assessed the publication bias by visually examining the asymmetry in funnel graphs, Egger’s test, and Begg’s test, and we addressed the bias using the Trim and Fill method. Statistical analyses were performed in R Version 4.4.1 [20] using the “metafor” [21] and “meta” [22] packages

3. Results

Our initial search identified 295 unique studies that are potentially eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, we excluded several. We assessed 55 full-text articles, and 16 Studies met the inclusion criteria for our review and meta-analysis. Additionally, we searched for references and citations from eligible articles and included any further studies that met the inclusion criteria. A PRISMA flow diagram summarizing this process is presented in [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

All interventions in the included studies were integrated into the context of usual care. The type of lifestyle intervention differed between studies; 10 studies [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] focused solely on physical activity, 4 studies [33,34,35,36] implemented dietary changes exclusively, and 2 studies [37,38] incorporated both physical activity and dietary components. The interventions differed significantly in duration, intensity, delivery method, and focus. On average, the interventions lasted about 5 months, with durations ranging from 2 to 12 months [30,35]. A total of eleven studies [23,24,25,27,28,29,31,32,33,37,38] employed short-term interventions (less than six months), while five studies [26,30,34,35,36] employed longer-term interventions (six months or more). Participant age varied across studies; eleven studies [23,24,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37] predominantly involved older adults (average age 50+), while five studies [25,26,27,36,38] included participants with an average age below 50 years.

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the clinical trials included in this review. Across the included studies, sample sizes ranged from 18 to 117 participants. The studies were conducted in South Asian countries and varied in design, encompassing RCTs, prospective cohort studies, and case–control designs. The duration of follow-up ranged from 2 to 12 months, allowing for comprehensive assessment of both short- and long-term outcomes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included trials.

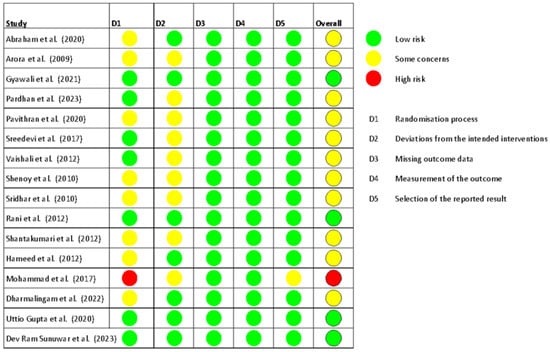

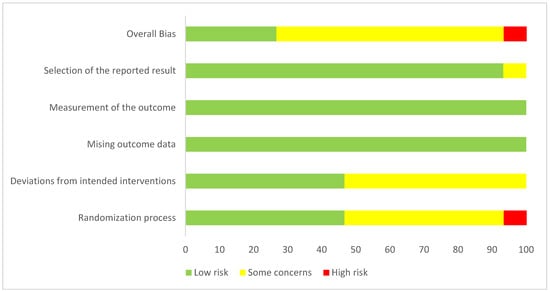

In terms of risk of bias, most RCTs were rated as having some concerns (n = 11, 69%), followed by low risk (n = 4, 25%), and high risk (n = 1, 6%). The risk of bias for all included trials is presented in [Figure 2], and the percentage of trials categorized as high risk, low risk, or with some concerns is detailed in [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Risk of bias in all trials included in the review [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38].

Figure 3.

Overall risk of bias summary of RCTs included in the meta-analyses.

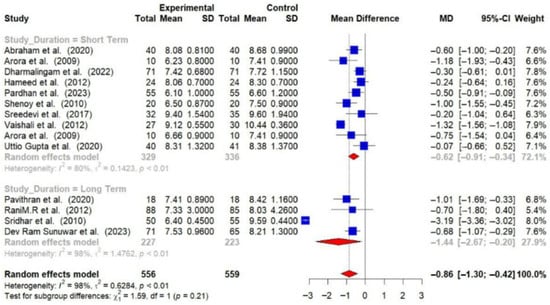

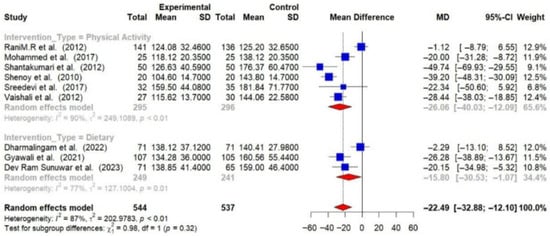

A total of 13 RCTs provided post-intervention data on HbA1c. The post-intervention pooled MD in HbA1c levels between intervention and control groups was −0.86% (95% CI: −1.30 to −0.42). This reduction is statistically significant (p < 0.01), indicating that lifestyle modifications effectively lower HbA1c levels among T2DM patients. However, substantial heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 98%), suggesting that the effectiveness of the interventions varied across different studies [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of the post-intervention mean difference in HbA1c between the intervention and control groups [23,24,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38]. Each blue square represents an individual study result, with larger squares indicating higher weight. The horizontal lines show the 95% confidence intervals. The red diamond represents the overall pooled effect from the random-effects model. The solid vertical line indicates no effect, and the dotted line shows the overall pooled estimate.

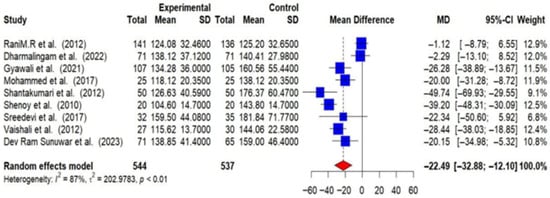

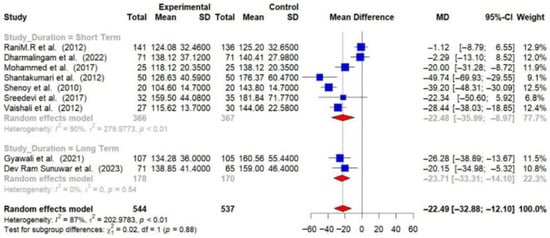

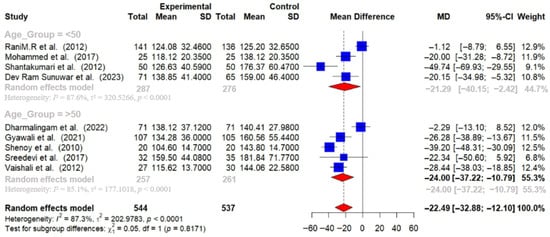

Out of 16 RCTs, 9 provided post-intervention data on FBG among T2DM patients. Using a random-effects meta-analysis, the post-intervention pooled MD in FBG levels between intervention and control groups was found to be −22.49 mg/dL (95% CI: −32.88 to −12.10), indicating that lifestyle modifications effectively lower FBG levels (p < 0.01). A substantial level of heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 87%), suggesting that the effectiveness of the interventions varied across different studies [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of the post-intervention mean difference in FBG levels between intervention and control groups [25,26,27,28,29,31,33,35,36].

Subgroup analyses were conducted, and detailed forest plots are provided in the Supplementary Materials. Long-term trials (≥6 months) demonstrated a greater reduction in HbA1c (−1.44% [95% CI: −2.67 to −0.20]) and FBG (−23.71 mg/dL [95% CI: −33.31 to −14.10]) compared to short-term trials (<6 months) (HbA1c: −0.62% [95% CI: −0.91 to −0.34]; FBG: −22.48 mg/dL [95% CI: −35.99 to −8.97]) [Figure 6 and Figure 7].

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis of the post-intervention mean difference in HbA1c levels between intervention and control groups by the duration of study [23,24,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38]. The grey color was automatically suggested by RStudio (2025.07.2+1299 “Ocean Storm”) program to differentiate the sub-group names from the author names. The color was not manually selected.

Figure 7.

Meta-analysis of the post-intervention mean difference in FBG levels between intervention and control groups by the study duration [25,26,27,28,29,31,33,35,36]. The grey color was automatically suggested by RStudio program to differentiate the sub-group names from the author names. The color was not manually selected.

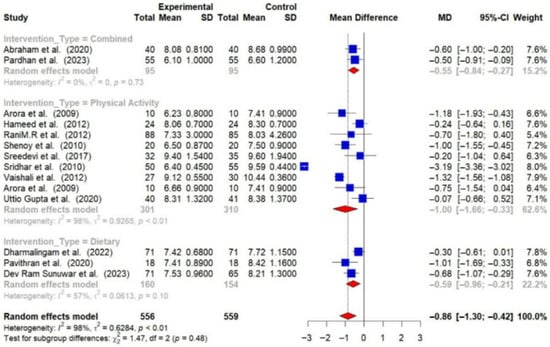

Physical activity interventions led to more substantial reductions in HbA1c (−0.99% [95% CI: −1.66 to −0.33]) and FBG (−26.06 mg/dL [95% CI: −40.03 to −12.09]) compared to dietary interventions (HbA1c: −0.59% [95% CI: −0.96 to −0.21]; FBG: −15.80 mg/dL [95% CI: −30.53 to −1.07]). Combined interventions also showed a decrease in HbA1c (−0.55 [95% CI: −0.84 to −0.27]) [Figure 8 and Figure 9].

Figure 8.

Meta-analysis of the post-intervention mean difference in HbA1c levels between intervention and control groups by the type of intervention [23,24,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38]. The grey color was automatically suggested by RStudio program to differentiate the sub-group names from the author names. The color was not manually selected.

Figure 9.

Meta-analysis of the post-intervention mean difference in FBG levels between intervention and control groups by the type of intervention [25,26,27,28,29,31,33,35,36]. The grey color was automatically suggested by RStudio program to differentiate the sub-group names from the author names. The color was not manually selected.

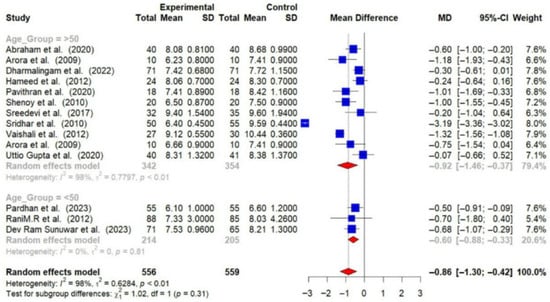

Participants over 50 years of age experienced greater reductions in HbA1c (−0.92% [95% CI: −1.46 to −0.37]) and FBG (−24.00 mg/dL [95% CI: −37.22 to −10.79]) compared to those under 50 years (HbA1c: −0.60% [95% CI: −0.88 to −0.33]; FBG: −21.29 mg/dL [95% CI: −40.15 to −2.42]) [Figure 10 and Figure 11].

Figure 10.

Meta-analysis of the post-intervention mean difference in HbA1c levels between the intervention and control groups by age group [23,24,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38]. The grey color was automatically suggested by RStudio program to differentiate the sub-group names from the author names. The color was not manually selected.

Figure 11.

Meta-analysis of the post-intervention mean difference in FBG levels between intervention and control groups by age group [25,26,27,28,29,31,33,35,36]. The grey color was automatically suggested by RStudio program to differentiate the sub-group names from the author names. The color was not manually selected.

Overall, these studies demonstrate that lifestyle interventions are more effective than dietary interventions in lowering HbA1c, with patients over 50 years showing greater improvements in both HbA1c and fasting blood glucose levels. Despite these observed differences in effect sizes across subgroups, none of the tests for subgroup differences were statistically significant for either HbA1c or FBG, and marked heterogeneity was present.

We found considerable heterogeneity in the pooled analyses (HbA1c: I2 = 98%; FBG: I2 = 87%). However, subgroup analyses revealed that heterogeneity was markedly reduced in certain categories. For example, combined lifestyle interventions showed perfect consistency (I2 = 0%) for HbA1c, while dietary interventions had moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 57%). Similarly, heterogeneity for FBG was not present in long-term studies (I2 = 0%) and reduced in dietary interventions (I2 = 77%).

We conducted a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for both HbA1c and FBG to assess the robustness of the results. For HbA1c, the pooled MD ranged from −0.66 to −0.92, and heterogeneity remained high (I2 > 97%), an indication of the consistency in findings across the different studies. For FBG, the pooled MD ranged from −19.73 to −25.55, with heterogeneity also remaining high (I2>79%). These results imply that no single study had a disproportionate impact on the overall effect, confirming the stability of the findings [Supplementary Figures S1 and S2].

We assessed publication bias using Egger’s test, Begg’s test, and the trim-and-fill method. Egger’s test showed that there was significant funnel plot asymmetry for HbA1c (t = 3.02, p = 0.0106), indicating potential publication bias, though there was no significant asymmetry in FBG (t = −0.95, p = 0.37). Begg’s test did not show any publication bias for either HbA1c (Kendall’s tau = −0.25, p = 0.23) or FBG (Kendall’s tau = −0.56, p = 0.06). We used the trim-and-fill method to adjust for potential bias, which imputed additional studies. For HbA1c, this adjustment suggested that the intervention effect might be underestimated (MD = −2.09, 95% CI [−2.84; −1.34] vs. MD = −0.86, 95% CI [−1.30; −0.42] without adjustment). For FBG, the imputed studies resulted in a less negative mean difference (MD = −8.51, 95% CI [−21.34; 4.32] vs. MD = −22.49, 95% CI [−32.88; −12.09]), indicating potential overestimation of the intervention effect. Overall, our analysis suggests that while there is some evidence of publication bias in the HbA1c findings, it may not be substantial for FBG [Supplementary Figures S3–S6]. Egger’s and Begg’s tests suggested potential publication bias in studies assessing HbA1c; it may not be substantial for FBG, and the trim-and-fill method identified additional imputed studies, indicating that the overall effect estimates may be slightly overestimated.

4. Discussion

4.1. Glycemic Outcomes of Lifestyle Interventions

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the impact of lifestyle interventions on glycemic control in adults with T2DM across South Asian countries, focusing exclusively on RCTs. Our study offered a critical, region-specific evaluation of these interventions in the South Asian population, demonstrating a statistically and clinically significant reduction in both HbA1c and FBG levels.

The reduction of 0.5% of HbA1c is considered clinically significant [39]. Notably, we found a mean reduction of 0.86% in HbA1c and 22.49 mg/dL in FBG, which are larger than those reported in the meta-analyses by Jansson AK et al. [40], and Yuwen Wan et al. [41], This discrepancy in effect size may be attributed to the exclusive focus of our review on the South Asian population, which may have distinct genetic predispositions and responses to lifestyle interventions compared to the populations included in other reviews.

These findings are also comparable to the results of the Look AHEAD trial [42], which reported a 0.64% reduction in HbA1c after one year of intensive lifestyle modification among individuals with T2DM. Although the landmark diabetes prevention trials Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study [4] and USA Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group [5] did not report direct reductions in HbA1c or FBG, both demonstrated that structured lifestyle changes substantially lowered the incidence of T2DM.

4.2. Physical Activity and Glycemic Control

Exercise is an extremely important part of lowering blood sugar levels, achieved through multiple mechanisms. Both strength training and aerobic exercises promote the activity of the GLUT4 transporter protein in skeletal muscles, thus increasing the amount of glucose absorbed from the blood, thereby lowering blood sugar levels [43]. Physical activity also increases the sensitivity of skeletal muscle cells to insulin by increasing their oxidative capacity, the amount of mitochondria, and their reduced ability to accumulate excess lipid molecules [44]. Exercise also allows the entry of glucose into the cells despite low levels of insulin by stimulating the AMPK pathway [45].

4.3. Dietary Interventions and Glycemic Control

Similarly, a low-glycemic index and high fiber diet prevents a sudden rise in glucose levels [46]. Restriction of calorie intake and a balanced nutrient diet improve insulin sensitivity, thereby reducing hepatic glucose production, thus lowering the levels of fasting glucose and Hemoglobin A1C [47]. In addition, diets such as Mediterranean or low-carbohydrate diets improve lipid and inflammation status, therefore offering a positive impact on metabolism among diabetic patients [48].

4.4. Comparison of Physical Activity and Dietary Interventions

The majority of the included studies emphasized physical activity as the primary intervention, encompassing various forms such as yoga [25,26,27,29,31,32], resistance training [23,24], aerobic exercises, and daily exercise routines [28,30,38]. Physical activity interventions led to larger reductions in HbA1c (−0.99%) and FBG (−26.06 mg/dL) compared to dietary interventions (HbA1c: −0.59% and FBG: −15.80 mg/dL), indicating the vital role of physical activity in the management of T2DM patients. These results are consistent with the existing literature. For example, Jansson AK et al. [40] reported a significant reduction in HbA1c with resistance training (weighted MD = −0.39%), while Yuwen Wan et al. [41] observed reductions in HbA1c (−0.50%) and FBG (−12.03 mg/dL). However, these reviews have included studies of different populations, potentially explaining the relatively smaller effect size as compared to our findings in South Asian adults. In contrast, Jun Jia et al. [49] found that resistance training interventions did not significantly change HbA1c levels compared to controls (−0.22%, 95%CI: −0.98 to 0.54). They suggested that their focus was on quality of life rather than glycemic control, which may have influenced these findings, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions when assessing HbA1c outcomes.

Dietary interventions, while fewer in number, also played a role in improving glycemic control. Consistent with Parisa Ghasemi et al. [50] which demonstrated reductions in FBG (−11.68 mg/dL) and HbA1c (−0.29%) with a very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet, our results (HbA1c: −0.59% [95% CI: −0.96 to −0.21]; FBG: −15.80 mg/dL [95% CI: −30.53 to −1.07]) support the role of dietary modifications in improving glycemic control through improved nutritional literacy. Encouraging dietary changes at both clinical and community levels can improve awareness and adherence to diabetes-specific nutritional guidelines, which in turn leads to better patient outcomes.

4.5. Heterogeneity and Subgroup Analyses

We observed high heterogeneity in our pooled results, which might have resulted from differences in lifestyle interventions, duration of the studies, and participant characteristics within the South Asian studies. When we performed a subgroup analysis, we found that some of this variability could be explained by these factors. For example, studies that used combined lifestyle interventions and those with longer follow-up periods showed more consistency in the results. Overall, even though the heterogeneity across studies was high, the direction of the effect consistently favored lifestyle interventions for improving glycemic control.

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our study are that we only included RCTs, which have long been recognized as the gold standard for evidence [51], and the comprehensive nature of our analysis, which included random-effects meta-analysis, subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, and assessment of publication bias. To the best of our knowledge, our systematic review and meta-analysis are the first to specifically investigate the impact of lifestyle interventions on glycemic control in South Asian adults with T2DM.

However, some limitations must be acknowledged. Most studies were carried out in India, with only a limited number of studies from other South Asian countries, limiting the generalizability of our findings to the entire South Asian population. The short-term nature of follow-up data restricts our ability to determine the sustained impact of lifestyle interventions. Another limitation was that we were unable to directly apply Egger’s test for FBG due to low sample size (n = 9), which did not meet the minimum threshold of 10 required for reliable results. Because of this, we had to modify the standard procedure. Therefore, we conducted the Begg’s test and used the trim-and-fill method to assess potential bias.

4.7. Conclusion and Implications

The results showed clinically significant evidence that lifestyle interventions can improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM in South Asia. Despite the high heterogeneity, there has been a consistent reduction in HbA1c and FBG throughout the subgroups. These findings align with existing international guidelines from the IDF, American Diabetes Association (ADA) [2,52], and the World Health Organization (WHO) [53], all of which recommend lifestyle modifications like regular physical activity and dietary changes as crucial components of diabetes management and prevention. Future research should prioritize multi-center, well-supervised RCTs with longer follow-up periods in diverse South Asian populations. This is because participants in well-supervised studies are more likely to experience greater positive outcomes due to the structured guidance and consistent support provided throughout all sessions of the study [54]. Along with this, national guidelines should integrate dietary interventions and moderate physical activity into standard diabetic care at the health center level, along with initiatives to raise awareness and improve nutritional literacy among South Asian T2DM patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/medsci14010048/s1, Table S1: PubMed Search Strategy, Table S2: Web Of Science Search Strategy, Table S3: Scopus search Strategy, Table S4: CINAHL search Strategy (In EBSCOHost), Table S5: Cochrane Library Search Strategy, Table S6: Summary Results of database search and full-text screening, Figure S1: Sensitivity Analyses for HbA1c by performing the meta-analysis by excluding one study at a time, Figure S2: Sensitivity Analyses for FBG by performing the meta-analysis by excluding one study at a time, Figure S3: Funnel plot for random effects meta-analysis of post intervention mean difference of HbA1C Levels, Figure S4: Funnel plot for random effects meta-analysis of post intervention mean difference of FBG Levels, Figure S5: Funnel and Forest plots Publication Bias Analysis using Trim and Fill method for mean difference of HbA1c levels, Figure S6: Funnel and Forest plots of Publication Bias Analysis using Trim and Fill method for mean difference of FBG levels, PRISMA 2020 Checklist

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported. Study conception and design: I.A., H.T., G.V.P., and M.Y. Data collection and analysis: A.N., Y.S., S.S., M.S.R., and I.A. Manuscript writing: H.S.A., M.O., G.V.P., A.U., and I.A. Supervision and overall study integrity: I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the people who participated in primary RCTs and the teams who conducted them.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation (IDF). IDF Diabetes Atlas, 11th ed.; IDF: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Khan, N.A.; Wang, H.; Anand, S.; Jin, Y.; Campbell, N.R.C.; Pilote, L.; Quan, H. Ethnicity and sex affect diabetes incidence and outcomes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomilehto, J.; Lindström, J.; Eriksson, J.G.; Valle, T.T.; Hämäläinen, H.; Ilanne-Parikka, P.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S.; Laakso, M.; Louheranta, A.; Rastas, M.; et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowler, W.C.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Fowler, S.E.; Hamman, R.F.; Lachin, J.M.; Walker, E.A.; Nathan, D.M.; Watson, P.G.; Mendoza, J.T.; Smith, K.A.; et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 393–403. [Google Scholar]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Missbach, B.; Dias, S.; König, J.; Hoffmann, G. Impact of different training modalities on glycaemic control and blood lipids in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.; Ma, R.C.W.; Snehalatha, C. Diabetes in Asia. Lancet 2010, 375, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, A.; Singhal, N.; Sivakumar, B.; Bhagat, N.; Jaiswal, A.; Khurana, L. Nutrition transition in India: Secular trends in dietary intake and their relationship to diet-related non-communicable diseases. J. Diabetes 2011, 3, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forouhi, N.G.; Misra, A.; Mohan, V.; Taylor, R.; Yancy, W. Dietary and nutritional approaches for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. Bmj 2018, 361, k2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvetsky, A.C.; Edelstein, S.L.; Walford, G.; Boyko, E.J.; Horton, E.S.; Ibebuogu, U.N.; Knowler, W.C.; Montez, M.G.; Temprosa, M.; Hoskin, M.; et al. A High-Carbohydrate, High-Fiber, Low-Fat Diet Results in Weight Loss among Adults at High Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 2060–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Deng, L. Effects of an Outpatient Diabetes Self-Management Education on Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in China: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 1073131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, N.; Sahay, R.; Kalra, S.; Bajaj, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Shrestha, D.; Dhakal, G.; Tiwaskar, M.; Sahay, M.; Somasundaram, N.; et al. Consensus on Medical Nutrition Therapy for Diabesity (CoMeND) in Adults: A South Asian Perspective. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 1703–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhurji, N.; Javer, J.; Gasevic, D.; A Khan, N. Improving management of type 2 diabetes in South Asian patients: A systematic review of intervention studies. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e008986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, H.; Coulter, E.; Ghouri, N.; Paul, L. The effectiveness of structured exercise in the South Asian population with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Phys. Sportsmed. 2017, 45, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; The PRISMA Group; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Re-views and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Endnote Team. Endnote, version 21; Clarivate Analytics: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.; Flemyng, E. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 6.4; Updated August 2023; Cochrane: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduzzi, S.; Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2019, 22, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, E.; Shenoy, S.; Sandhu, J.S. Effects of resistance training on metabolic profile of adults with type 2 diabetes. Indian J. Med. Res. 2009, 129, 515–519. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.E.; Hameed, U.A.; Manzar, D.; Raza, S.; Shareef, M.Y. Resistance Training Leads to Clinically Meaningful Improvements in Control of Glycemia and Muscular Strength in Untrained Middle-aged Patients with type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 4, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R.; Banu, A.; S., I.; Jaiswal, R. Importance of yoga in diabetes and dyslipidemia. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2017, 4, 3504–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarathna, R.; Usharani, M.R.; Rao, A.R.; Chaku, R.; Kulkarni, R.; Nagendra, H.R. Efficacy of yoga based life style modification program on Medication score and lipid profile in type 2 diabetes—A randomized control study. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2012, 32, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantakumari, N.; Sequeira, S.; Eldeeb, R. Effect of a yoga intervention on hypertensive diabetic patients. J. Adv. Intern. Med. 2012, 1, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, S.; Guglani, R.; Sandhu, J.S. Effectiveness of an aerobic walking program using heart rate monitor and pedometer on the parameters of diabetes control in Asian Indians with type 2 diabetes. Prim. Care Diabetes 2010, 4, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreedevi, A.; Gopalakrishnan, U.A.; Ramaiyer, S.K.; Kamalamma, L. A Randomized controlled trial of the effect of yoga and peer support on glycaemic outcomes in women with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A feasibility study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridhar, B.; Haleagrahara, N.; Bhat, R.; Kulur, A.B.; Avabratha, S.; Adhikary, P. Increase in the heart rate variability with deep breathing in diabetic patients after 12-month exercise training. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2010, 220, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishali, K.; Kumar, K.V.; Adhikari, P.; UnniKrishnan, B. Effects of Yoga-Based Program on Glycosylated Hemoglobin Level Serum Lipid Profile in Community Dwelling Elderly Subjects with Chronic Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Occup. Ther. Geriatr. 2012, 30, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, N.; Gupta, U.; Gupta, Y.; Jose, D.; Mani, K.; Jyotsna, V.P.; Sharma, G. Effectiveness of Yoga-based Exercise Program Compared to Usual Care, in Improving HbA1c in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Control Trial. Int. J. Yoga 2020, 13, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmalingam, M.; Das, R.; Jain, S.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, M.; Kudrigikar, V.; Bachani, D.; Mehta, S.; Joglekar, S. Impact of Partial Meal Replacement on Glycemic Levels and Body Weight in Indian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (PRIDE): A Randomized Controlled Study. Diabetes Ther. 2022, 13, 1599–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavithran, N.; Kumar, H.; Menon, A.S.; Pillai, G.K.; Sundaram, K.R.; Ojo, O. The Effect of a Low GI Diet on Truncal Fat Mass and Glycated Hemoglobin in South Indians with Type 2 Diabetes-A Single Centre Randomized Prospective Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, B.; Sharma, R.; Mishra, S.R.; Neupane, D.; Vaidya, A.; Sandbæk, A.; Kallestrup, P. Effectiveness of a Female Community Health Volunteer-Delivered Intervention in Reducing Blood Glucose Among Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: An Open-Label, Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2035799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunuwar, D.R.; Nayaju, S.; Dhungana, R.R.; Karki, K.; Pradhan, P.M.S.; Poudel, P.; Nepal, C.; Thapa, M.; Shakya, N.S.; Sayami, M.; et al. Effectiveness of a dietician-led intervention in reducing glycated haemoglobin among people with type 2 diabetes in Nepal: A single centre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 2023, 18, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.M.; Sudhir, P.M.; Philip, M.; Bantwal, G. Efficacy of a Brief Self-management Intervention in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Trial from India. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardhan, S.; Upadhyaya, T.; Smith, L.; Sharma, T.; Tuladhar, S.; Adhikari, B.; Kidd, J.; Sapkota, R. Individual patient-centered target-driven intervention to improve clinical outcomes of diabetes, health literacy, and self-care practices in Nepal: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1076253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, R.R.; Rohlfing, C.L. The long and winding road to optimal HbA1c measurement. Clin. Chim. Acta 2013, 418, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, A.K.; Chan, L.X.; Lubans, D.R.; Duncan, M.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C. Effect of resistance training on HbA1c in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus and the moderating effect of changes in muscular strength: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2022, 10, e002595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Su, Z. The Impact of Resistance Exercise Training on Glycemic Control Among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2024, 26, 597–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Look AHEAD Research Group. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: One-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Yardley, J.E.; Riddell, M.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Dempsey, P.C.; Horton, E.S.; Castorino, K.; Tate, D.F. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Hao, C. The Effect and Mechanism of Regular Exercise on Improving Insulin Impedance: Based on the Perspective of Cellular and Molecular Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, E.A.; Sylow, L.; Hargreaves, M. Interactions between insulin and exercise. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 3827–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, W.R.; Baka, A.; Björck, I.; Delzenne, N.; Gao, D.; Griffiths, H.R.; Hadjilucas, E.; Juvonen, K.; Lahtinen, S.; Lansink, M.; et al. Impact of Diet Composition on Blood Glucose Regulation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 56, 541–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, W.; Ansari, T.; Butt, N.S.; Ab Hamid, M.R. Effect of diet on type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, T.; Zhang, S.; Bai, M.; Chen, Z.; Gao, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, J. Effect of Dietary Approaches on Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y.C.; Hu, Y.; Liu, S. The effects of resistance exercises interventions on quality of life and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prim. Care Diabetes 2024, 18, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, P.; Jafari, M.; Maskouni, S.J.; Hosseini, S.A.; Amiri, R.; Hejazi, J.; Chambari, M.; Tavasolian, R.; Rahimlou, M. Impact of very low carbohydrate ketogenic diets on cardiovascular risk factors among patients with type 2 diabetes; GRADE-assessed systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 21, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murad, M.H.; Asi, N.; Alsawas, M.; Alahdab, F. New evidence pyramid. Evid. Based Med. 2016, 21, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Bannuru, R.R.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Ekhlaspour, L.; Gaglia, J.L.; Hilliard, M.E.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S158–S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diabetes Fact Sheet; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- Lacroix, A.; Hortobágyi, T.; Beurskens, R.; Granacher, U. Effects of Supervised vs. Unsupervised Training Programs on Balance and Muscle Strength in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2341–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.