The Safety and Efficacy of Mechanical Thrombectomy with Acute Carotid Artery Stenting in an Extended Time Window: A Single-Center Study †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

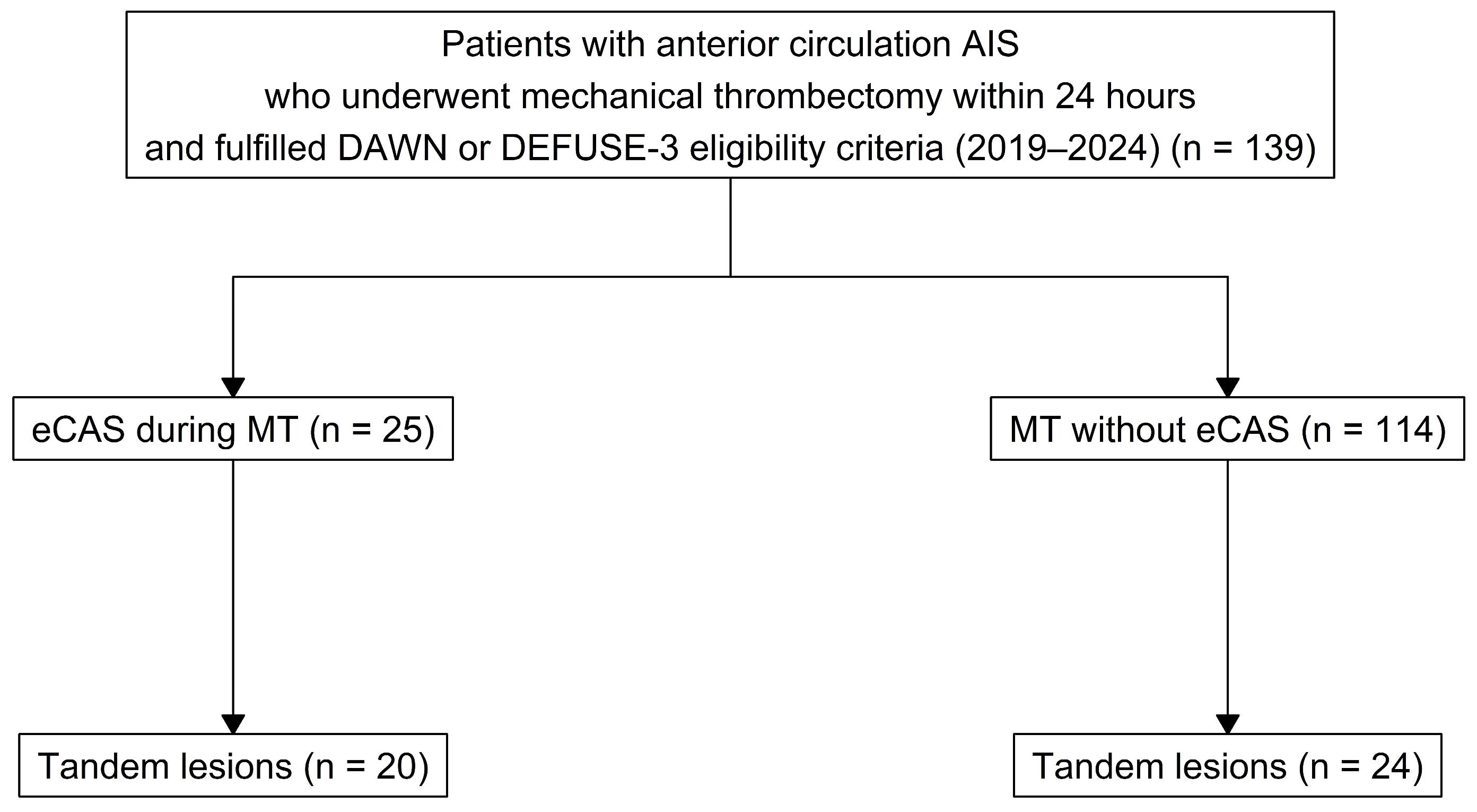

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data

- Infarct core volume < 70 mL

- critically hypoperfused volume/infarct core volume > 1.8

- mismatch volume > 15 mL

- Relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) < 30% (CT perfusion), Tmax > 6 s

- <21 mL core infarct and NIHSS ≥ 10 (and age ≥ 80 years old)

- <31 mL core infarct and NIHSS ≥ 10 (and age < 80 years old)

- 31 mL to <51 mL core infarct and NIHSS ≥ 20 (and age < 80 years old)

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

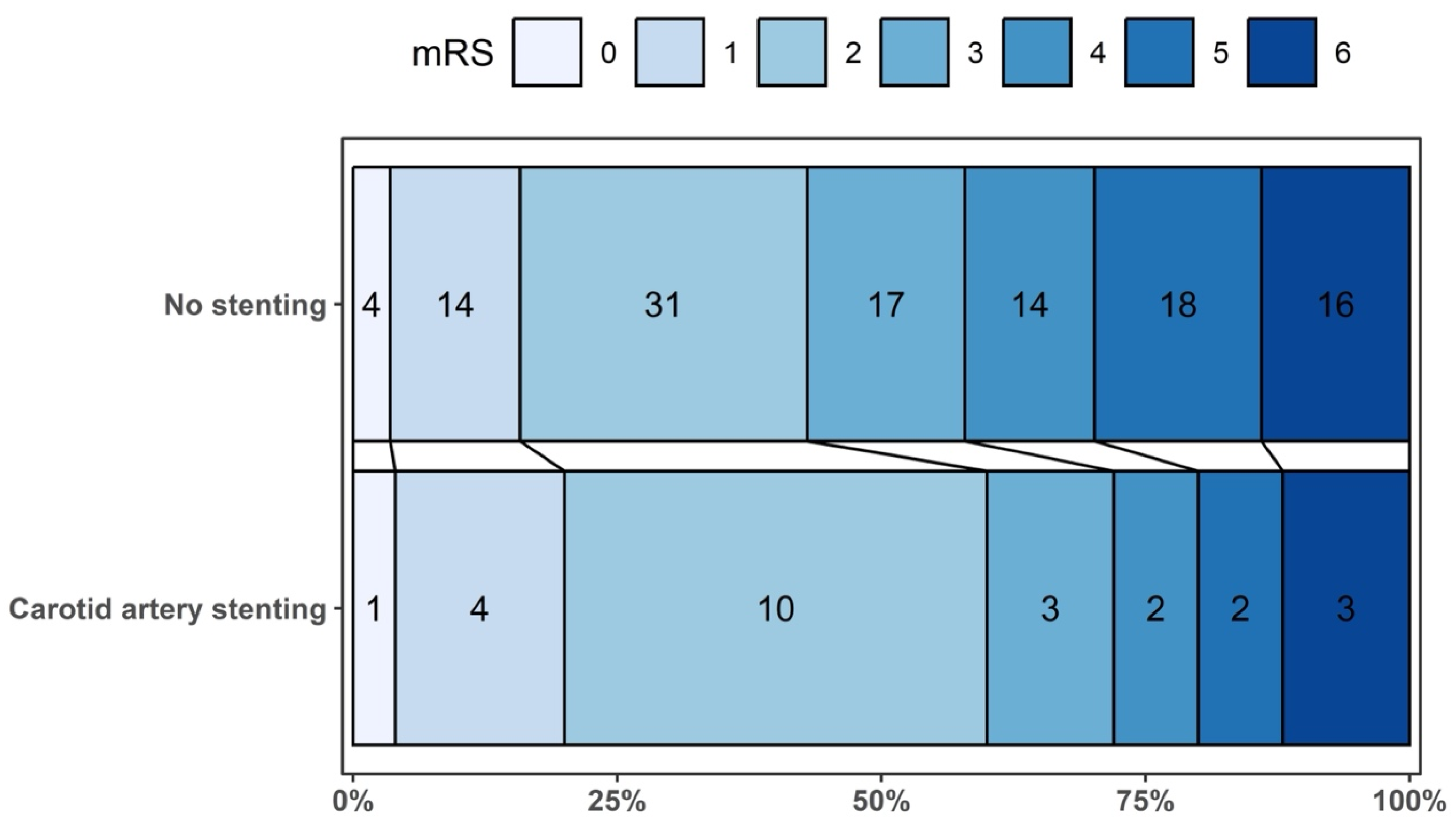

3.2. Study Outcomes

3.3. Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIS | Acute ischemic stroke |

| eCAS | Emergent carotid artery stenting |

| DAPT | Dual antiplatelet therapy |

| HT | Hemorrhagic transformation |

| LVO | Large vessel occlusion |

| MT | Mechanical thrombectomy |

| TL | Tandem lesions |

| NIHSS | National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| DWI | Diffusion-weighted imaging |

| CTP | Computed tomography perfusion |

| mRS | Modified Rankin Scale |

| sICH | Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage |

| CBF | Cerebral blood flow |

| rCBF | Relative cerebral blood flow |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| IPW | Inverse probability weighting |

| SMD | Standardized mean difference |

| GLM | Generalized linear model |

| RD | Risk difference |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| SAEM | Stochastic Approximation Expectation-Maximization |

| Q1 | The first quartile |

| Q3 | The third quartile |

References

- Jadhav, A.P.; Zaidat, O.O.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Yavagal, D.R.; Haussen, D.C.; Hellinger, F.R.; Jahan, R.; Jumaa, M.A.; Szeder, V.; Nogueira, R.G.; et al. Emergent Management of Tandem Lesions in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Analysis of the STRATIS Registry. Stroke 2019, 50, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turc, G.; Tsivgoulis, G.; Audebert, H.J.; Boogaarts, H.; Bhogal, P.; De Marchis, G.M.; Fonseca, A.C.; Khatri, P.; Mazighi, M.; Pérez de la Ossa, N.; et al. European Stroke Organisation—European Society for Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy Expedited Recommendation on Indication for Intravenous Thrombolysis before Mechanical Thrombectomy in Patients with Acute Ischaemic Stroke and Anterior Circulation Large Vessel Occlusion. Eur. Stroke J. 2022, 7, I–XXVI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, R.G.; Jadhav, A.P.; Haussen, D.C.; Bonafe, A.; Budzik, R.F.; Bhuva, P.; Yavagal, D.R.; Ribo, M.; Cognard, C.; Hanel, R.A.; et al. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 Hours after Stroke with a Mismatch between Deficit and Infarct. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, G.W.; Marks, M.P.; Kemp, S.; Christensen, S.; Tsai, J.P.; Ortega-Gutierrez, S.; McTaggart, R.A.; Torbey, M.T.; Kim-Tenser, M.; Leslie-Mazwi, T.; et al. Thrombectomy for Stroke at 6 to 16 Hours with Selection by Perfusion Imaging. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olthuis, S.G.H.; Pirson, F.A.V.; Pinckaers, F.M.E.; Hinsenveld, W.H.; Nieboer, D.; Ceulemans, A.; Knapen, R.R.M.M.; Robbe, M.M.Q.; Berkhemer, O.A.; van Walderveen, M.A.A.; et al. Endovascular Treatment versus No Endovascular Treatment after 6–24 h in Patients with Ischaemic Stroke and Collateral Flow on CT Angiography (MR CLEAN-LATE) in the Netherlands: A Multicentre, Open-Label, Blinded-Endpoint, Randomised, Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Abdalkader, M.; Sang, H.; Sarraj, A.; Campbell, B.C.V.; Miao, Z.; Huo, X.; Yoo, A.J.; Zaidat, O.O.; Thomalla, G.; et al. Endovascular Thrombectomy for Large Ischemic Core Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Neurology 2025, 104, e213443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, M.; Menon, B.K.; Van Zwam, W.H.; Dippel, D.W.J.; Mitchell, P.J.; Demchuk, A.M.; Dávalos, A.; Majoie, C.B.L.M.; Van Der Lugt, A.; De Miquel, M.A.; et al. Endovascular Thrombectomy after Large-Vessel Ischaemic Stroke: A Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data from Five Randomised Trials. Lancet 2016, 387, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anadani, M.; Spiotta, A.; Alawieh, A.; Turjman, F.; Piotin, M.; Steglich-Arnholm, H.; Holtmannspötter, M.; Taschner, C.; Eiden, S.; Haussen, D.C.; et al. Effect of Extracranial Lesion Severity on Outcome of Endovascular Thrombectomy in Patients with Anterior Circulation Tandem Occlusion: Analysis of the TITAN Registry. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2019, 11, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desilles, J.P.; Consoli, A.; Redjem, H.; Coskun, O.; Ciccio, G.; Smajda, S.; Labreuche, J.; Preda, C.; Ruiz Guerrero, C.; Mazighi, M.; et al. Successful Reperfusion with Mechanical Thrombectomy Is Associated with Reduced Disability and Mortality in Patients with Pretreatment Diffusion-Weighted Imaging-Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score ≤6. Stroke 2017, 48, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Kronast, N.H.; Zaidat, O.O.; Froehler, M.T.; Jahan, R.; Aziz-Sultan, M.A.; Klucznik, R.P.; Saver, J.L.; Hellinger, F.R.; Yavagal, D.R.; Yao, T.L.; et al. Systematic Evaluation of Patients Treated With Neurothrombectomy Devices for Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2017, 48, 2760–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, F.; Treurniet, K.; Kaesmacher, J.; Kappelhof, M.; Rohner, R.; Yang, P.; Liu, J.; Suzuki, K.; Yan, B.; van Elk, T.; et al. Intravenous Thrombolysis before Endovascular Treatment versus Endovascular Treatment Alone for Patients with Large Vessel Occlusion and Carotid Tandem Lesions: Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis of Six Randomised Trials. Lancet Neurol. 2025, 24, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, R.G.; Gupta, R.; Jovin, T.G.; Levy, E.I.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Zaidat, O.O.; Rai, A.; Hirsch, J.A.; Hsu, D.P.; Rymer, M.M.; et al. Predictors and Clinical Relevance of Hemorrhagic Transformation after Endovascular Therapy for Anterior Circulation Large Vessel Occlusion Strokes: A Multicenter Retrospective Analysis of 1122 Patients. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2015, 7, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Tian, X.; Shi, Z.; Peng, W.; Zhang, X.; Yang, P.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lou, M.; Yin, C.; et al. Clinical and Imaging Indicators of Hemorrhagic Transformation in Acute Ischemic Stroke after Endovascular Thrombectomy. Stroke 2022, 53, 1674–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Lam, C.; Christie, L.; Blair, C.; Li, X.; Werdiger, F.; Yang, Q.; Bivard, A.; Lin, L.; Parsons, M. Risk Factors of Hemorrhagic Transformation in Acute Ischaemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaesmacher, J.; Kaesmacher, M.; Maegerlein, C.; Zimmer, C.; Gersing, A.S.; Wunderlich, S.; Friedrich, B.; Boeckh-Behrens, T.; Kleine, J.F. Hemorrhagic Transformations after Thrombectomy: Risk Factors and Clinical Relevance. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2017, 43, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppe, A.Y.; Jacquin, G.; Roy, D.; Stapf, C.; Derex, L. Tandem Carotid Lesions in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Challenges, and Future Directions. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 41, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabłoński, B.; Wyszomirski, A.; Pracoń, A.; Stańczak, M.; Gąsecki, D.; Karaszewski, B. The safety and efficacy of mechanical thrombectomy with acute carotid artery stenting in an extended time window: A single- center study. Int. J. Stroke 2025, 20, 374–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacke, W.; Kaste, M.; Bluhmki, E.; Brozman, M.; Dávalos, A.; Guidetti, D.; Larrue, V.; Lees, K.R.; Medeghri, Z.; Machnig, T.; et al. Thrombolysis with Alteplase 3 to 4.5 Hours after Acute Ischemic Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires Coelho, A.; Lobo, M.; Gouveia, R.; Silveira, D.; Campos, J.; Augusto, R.; Coelho, N.; Canedo, A. Overview of Evidence on Emergency Carotid Stenting in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke Due to Tandem Occlusions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. (Torino) 2020, 60, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, W.J.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Ackerson, T.; Adeoye, O.M.; Bambakidis, N.C.; Becker, K.; Biller, J.; Brown, M.; Demaerschalk, B.M.; Hoh, B.; et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke a Guideline for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019, 50, E344–E418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anadani, M.; Marnat, G.; Consoli, A.; Papanagiotou, P.; Nogueira, R.G.; Siddiqui, A.; Ribo, M.; Spiotta, A.M.; Bourcier, R.; Kyheng, M.; et al. Endovascular Therapy of Anterior Circulation Tandem Occlusions: Pooled Analysis From the TITAN and ETIS Registries. Stroke 2021, 52, 3097–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diana, F.; Romoli, M.; Toccaceli, G.; Rouchaud, A.; Mounayer, C.; Romano, D.G.; Di Salle, F.; Missori, P.; Zini, A.; Aguiar De Sousa, D.; et al. Emergent Carotid Stenting versus No Stenting for Acute Ischemic Stroke Due to Tandem Occlusion: A Meta-Analysis. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2023, 15, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Carotid Artery Stenting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable 1 | Overall N = 139 | Yes N = 25 | No N = 114 | p-Value 2 |

| Age [years] | 0.117 | |||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 69.0 (62.0–76.0) | 66.0 (58.0–71.0) | 70.0 (63.0–77.0) | |

| Female, n/N (%) | 68/139 (48.9%) | 10/25 (40.0%) | 58/114 (50.9%) | 0.381 |

| NIHSS baseline | 0.358 | |||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 15.0 (11.0–19.0) | 14.0 (10.0–19.0) | 15.5 (12.0–19.0) | |

| IVT, n/N (%) | 11/139 (7.9%) | 3/25 (12.0%) | 8/114 (7.0%) | 0.416 |

| Site of occlusion, n/N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Tandem occlusion | 44/139 (31.7%) | 20/25 (80.0%) | 24/114 (21.1%) | |

| ICA extracranial | 13/139 (9.4%) | 5/25 (20.0%) | 8/114 (7.0%) | |

| Other | 82/139 (59.0%) | 0/25 (0.0%) | 82/114 (71.9%) | |

| Time to treatment [hours] | 0.139 | |||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 13.0 (10.5–15.9) | 14.1 (12.9–17.2) | 12.6 (10.3–15.5) | |

| Core DWI/CBF < 30% CTP 3 | 0.654 | |||

| Median (Q1–Q3); N missing | 19.0 (10.0–30.0); 11 | 18.0 (7.0–29.0); 2 | 20.0 (10.0–30.0); 9 | |

| Atherosclerosis, n/N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Atherosclerosis | 42/139 (30.2%) | 22/25 (88.0%) | 20/114 (17.5%) | |

| Dissection | 5/139 (3.6%) | 3/25 (12.0%) | 2/114 (1.8%) | |

| No | 92/139 (66.2%) | 0/25 (0.0%) | 92/114 (80.7%) | |

| Antithrombotic medication, n/N (%) | 0.174 | |||

| Antiplatelet | 25/139 (18.0%) | 3/25 (12.0%) | 22/114 (19.3%) | |

| Oral anticoagulant | 19/139 (13.7%) | 1/25 (4.0%) | 18/114 (15.8%) | |

| No | 95/139 (68.3%) | 21/25 (84.0%) | 74/114 (64.9%) | |

| Antithrombotic treatment during procedure, n/N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 103/139 (74.1%) | 0/25 (0.0%) | 103/114 (90.4%) | |

| DAPT and/or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 24/139 (17.3%) | 22/25 (88.0%) | 2/114 (1.8%) | |

| Others | 12/139 (8.6%) | 3/25 (12.0%) | 9/114 (7.9%) | |

| Hypertension, n/N (%) | 95/139 (68.3%) | 14/25 (56.0%) | 81/114 (71.1%) | 0.159 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n/N (%) | 38/139 (27.3%) | 8/25 (32.0%) | 30/114 (26.3%) | 0.622 |

| Dyslipidemia, n/N (%) | 54/139 (38.8%) | 8/25 (32.0%) | 46/114 (40.4%) | 0.503 |

| Smoking, n/N (%) | 56/139 (40.3%) | 10/25 (40.0%) | 46/114 (40.4%) | >0.999 |

| Mothership, n/N (%) | 0.171 | |||

| Yes | 52/139 (37.4%) | 6/25 (24.0%) | 46/114 (40.4%) | |

| No, drip and ship | 87/139 (62.6%) | 19/25 (76.0%) | 68/114 (59.6%) | |

| Number of passes with thrombectomy device, n/N (%) | 0.543 | |||

| 1 | 74/139 (53.2%) | 14/25 (56.0%) | 60/114 (52.6%) | |

| 2 | 40/139 (28.8%) | 8/25 (32.0%) | 32/114 (28.1%) | |

| 3 | 12/139 (8.6%) | 2/25 (8.0%) | 10/114 (8.8%) | |

| 4 | 9/139 (6.5%) | 0/25 (0.0%) | 9/114 (7.9%) | |

| 5 | 3/139 (2.2%) | 1/25 (4.0%) | 2/114 (1.8%) | |

| 6 | 1/139 (0.7%) | 0/25 (0.0%) | 1/114 (0.9%) | |

| Carotid Artery Stenting | IPW-Weighted Binomial Regression with Identity Link | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Yes N = 25 | No N = 114 | Risk Difference (95% CI) | p-Value |

| mRS 0–1 at 90 days, n/N (%) | 5/25 (20.0%) | 18/114 (15.8%) | 0.05 (−0.17; 0.26) | 0.678 |

| mRS 0–2 at 90 days, n/N (%) | 15/25 (60.0%) | 49/114 (43.0%) | 0.25 (−0.02; 0.52) | 0.067 |

| Parenchymal hematoma (PH 1–2) vs. other hemorrhagic transformation types or none, n/N (%) | 3/25 (12.0%) | 21/114 (18.4%) | −0.11 (−0.31; 0.10) | 0.308 |

| Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, n/N (%) | 2/25 (8.0%) | 4/114 (3.5%) | 0.06 (−0.06; 0.17) | 0.317 |

| Mortality at 90 days, n/N (%) | 3/25 (12.0%) | 16/114 (14.0%); | −0.03 (−0.22; 0.16) | 0.786 |

| Carotid Artery Stenting | IPW-Weighted Binomial Regression with Identity Link | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Yes N = 25 | No N = 24 | Risk Difference (95% CI) | p-Value |

| mRS 0–1 at 90 days, n/N (%) | 5/25 (20.0%) | 4/24 (16.7%) | 0.03 (−0.21; 0.27) | 0.817 |

| mRS 0–2 at 90 days, n/N (%) | 15/25 (60.0%) | 10/24 (41.7%) | 0.18 (−0.12; 0.49) | 0.232 |

| Parenchymal hematoma (PH 1–2) vs. other hemorrhagic transformation types or none, n/N (%) | 3/25 (12.0%) | 6/24 (25.0%) | −0.10 (−0.34; 0.14) | 0.416 |

| Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, n/N (%) | 2/25 (8.0%) | 1/24 (4.2%) | 0.06 (−0.10; 0.22) | 0.480 |

| Mortality at 90 days, n/N (%) | 3/25 (12.0%) | 2/24 (8.3%) | 0.02 (−0.16; 0.20) | 0.853 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jabłoński, B.; Wyszomirski, A.; Pracoń, A.; Stańczak, M.; Gąsecki, D.; Gorycki, T.; Dorniak, W.; Regent, B.; Magnus, M.; Baścik, B.; et al. The Safety and Efficacy of Mechanical Thrombectomy with Acute Carotid Artery Stenting in an Extended Time Window: A Single-Center Study. Med. Sci. 2026, 14, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010047

Jabłoński B, Wyszomirski A, Pracoń A, Stańczak M, Gąsecki D, Gorycki T, Dorniak W, Regent B, Magnus M, Baścik B, et al. The Safety and Efficacy of Mechanical Thrombectomy with Acute Carotid Artery Stenting in an Extended Time Window: A Single-Center Study. Medical Sciences. 2026; 14(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleJabłoński, Bartosz, Adam Wyszomirski, Aleksandra Pracoń, Marcin Stańczak, Dariusz Gąsecki, Tomasz Gorycki, Waldemar Dorniak, Bartosz Regent, Michał Magnus, Bartosz Baścik, and et al. 2026. "The Safety and Efficacy of Mechanical Thrombectomy with Acute Carotid Artery Stenting in an Extended Time Window: A Single-Center Study" Medical Sciences 14, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010047

APA StyleJabłoński, B., Wyszomirski, A., Pracoń, A., Stańczak, M., Gąsecki, D., Gorycki, T., Dorniak, W., Regent, B., Magnus, M., Baścik, B., Szurowska, E., & Karaszewski, B. (2026). The Safety and Efficacy of Mechanical Thrombectomy with Acute Carotid Artery Stenting in an Extended Time Window: A Single-Center Study. Medical Sciences, 14(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010047