Abstract

Background: Intestinal angioedema is an important drug-induced adverse effect that is often misdiagnosed due to vague and nonspecific symptoms. This study aimed to identify drugs with potential to cause intestinal angioedema by performing a disproportionality analysis, supplemented with literature review. Methods: Using OpenVigil, we extracted relevant individual case safety reports from the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database. Drugs with signal of disproportionate reporting (SDR) of intestinal angioedema were identified. A literature review was performed using PubMed and Embase databases to identify potential suspect drugs. Results: During 2004–2024, 303 cases of intestinal angioedema were reported to FAERS. Fourteen suspect medications showed SDR; of these, seven drugs were also reported in the literature to have caused intestinal angioedema, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, losartan, and acetylsalicyclic acid. A literature search identified 89 relevant articles, providing details of 121 cases. Some drugs linked to intestinal angioedema in the literature did not show SDR. Conclusions: Disproportionality analysis as well as a literature review showed that most patients were middle-aged females on antihypertensive therapy. The results will assist health professionals in determining the temporal association of acute abdomen with the suspected drug, potentially avoiding unnecessary interventions and their attendant complications.

1. Introduction

Intestinal angioedema is the oedema occurring within the submucosal space of the bowel that thickens the intestinal wall [1]. Gastrointestinal involvement leads to nonspecific symptoms that consist of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, that can resemble an acute abdominal condition. In rare cases, the massive collection of fluids within the gut lumen, gut wall, and the peritoneum can eventually result in hypovolemic shock [2]. In general, the classification of angioedema is based on its cause, comprising drug-induced; hereditary, with or without a deficiency of the enzyme C1 esterase inhibitor; acquired deficiency of C1 esterase inhibitor; and allergic angioedema [3]. Hereditary angioedema (HAE) affects around one in every 10,000 to 50,000 people, regardless of ethnicity, although a recent Norwegian study suggests that one out of every 100,000 people could be impacted [4]. The epidemiological data of drug-induced intestinal angioedema is undetermined yet. Intestinal angioedema is an exceedingly difficult diagnosis since it is a lesser-known ailment that is not as widespread as angioedema of the tongue, face, genitals, upper airways, or extremities [1]. Reactions to food (that incorporates shellfish, nuts, and some fruits), drugs, bug stings, latex, or other external allergens may culminate in allergic angioedema [3]. HAE attacks can be triggered by physical stress (pressure, mechanical impact), medication (oestrogen contraceptives, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACE-I]), medical interventions, infections, and surgical procedures (like dental surgery), endogenous fluctuations in hormones (menopause, menstruation, pregnancy), or psychological stress [5].

Intestinal angioedema has been reported to be caused by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) [6]. ACE-I are now the most frequently implicated drugs in the development of iatrogenic intestinal angioedema. ACE-I are frequently prescribed to treat renal and cardiovascular conditions. According to many guidelines, they are one of the first-line medications in treating essential hypertension [7,8]. Plenty of reviews and case reports have established that ACE-Is cause intestinal angioedema [9]. As ACE-Is prevent bradykinin (BK) from being converted to its inactive metabolites, BK builds up and plays a role in the development of intestinal angioedema. Patients merely require supporting care; antihistamines and corticosteroids are not indicated [10,11]. Due to the fact that their nonspecific vague symptoms can mirror an acute abdominal condition and provide diagnostic dilemmas, 57% of patients with ACE-I-induced intestinal angioedema have previously undergone gastrointestinal surgery or biopsies [12]. It would have been curtailed, and symptoms would have improved within 12 to 72 h if ACE-I had been identified as the causal agent and stopped immediately. Therefore, early clinical suspicion of drug-induced intestinal angioedema is crucial for surgeons [6]. A comprehensive analysis of all drugs that have the potential to induce intestinal angioedema is therefore necessary, since many cases may go unreported or undiagnosed, and such rare adverse reactions to drugs are very unlikely to be encountered during clinical trials. There may be other drugs that have the potential to induce intestinal angioedema but have not yet been identified or documented in scientific literature. Updating physicians’ knowledge on drug-induced intestinal angioedema will assist prevent significant morbidity, unnecessary testing, and diagnostic delays [13].

Adverse event databases are useful in identifying drug-adverse event relationships. The United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) was created to assist the FDA in monitoring the safety of drugs and medicinal products after they have been marketed. FAERS contributes 45% of global adverse event data and serves as one of the biggest pharmacovigilance databases with open public access [14,15]. All drugs with a temporal relation to an adverse drug reaction are reported. It is often difficult to establish the precise causal relationship between a drug and an adverse event, and rescue drugs are often included. Due to this, FAERS is constrained by its very nature, making it impossible to draw definitive conclusions regarding prevalence, incidence, and assessment of causality of adverse drug reactions. Additionally, reporting may be significantly biased depending on regional awareness or national attention [16]. Disproportionality methods are being used to detect signals of disproportionate reporting that may warrant additional clinical exploration to establish the role of the drug in causing an adverse event.

Given that the current literature on drug-induced intestinal angioedema is largely confined to case reports/case series, a comprehensive analysis of spontaneously reported adverse events along with a targeted literature review may reveal the drugs with potential to cause intestinal angioedema. Accordingly, the current study aimed to perform a disproportionality analysis to identify drugs with signals of disproportionate reporting (SDR) of intestinal angioedema. To overcome the inherent limitations of spontaneously reported adverse event data and improve the validity of the findings, the disproportionality analysis has been coupled with literature evidence. This study is aligned to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3.4: “By 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being.”

2. Method

2.1. Literature Search

We searched the published literature to identify papers describing drug-induced intestinal angioedema. The extracted papers were used to identify the suspect medications, the clinicodemographic characteristics of the patients, outcomes and management, and the proposed mechanism. To identify the relevant literature, we searched the PubMed and Embase databases without any time or language restrictions. All identified case reports were included in the study, irrespective of the quality of the report. The search strategy used was as follows: (“intestinal angioedema” OR “small bowel angioedema” OR “visceral angioedema”). Two authors independently searched for the relevant studies, and the results were deduplicated.

2.2. ADR Database Analysis

Since not all cases of potentially drug-induced intestinal angioedema may be reported in the literature, we supplemented the literature search by identifying relevant adverse event reports from the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database, a database of spontaneously reported adverse events by consumers, doctors, other healthcare professionals, and lawyers. All individual case safety reports (ICSRs) reported to the FAERS from the first quarter of 2004 to third quarter of 2024 were included. The FAERS data was accessed using the OpenVigil (version 2.1) software application [17]. OpenVigil provides an intuitive custom user interface for drug/ADR search and for conducting disproportionality analysis. Cases of potentially drug-induced intestinal angioedema were identified by searching for the following Medical Dictionary of Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) low level terms (LTs): intestinal angioedema and small bowel angioedema. ICSRs reported from United States involving all ages, genders, indications, outcomes, and reporter types were included for the analysis. The drugs listed as the suspect medication (primary or secondary) in one or more reports were considered to have caused the adverse event. To determine whether the observed reporting rate for the event is higher than expected for a particular drug, disproportionality analysis was performed using reporting odds ratio (ROR) [18]. A ROR >2 with the lower end of the 95% confidence interval >1 and a minimum of 3 reported cases was considered as SDR.

Among the drugs with SDR, those that have not yet been described in the literature as having caused intestinal angioedema were identified. A literature search was performed again using the PubMed and Embase databases by prefixing the drug name to the search string (“drugname” AND (“intestinal angioedema” OR “small bowel angioedema” OR “visceral angioedema”)). If no relevant literature was obtained on searching these databases, we searched the first three pages of search results in Google Scholar.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. The study adheres to the READUS-PV (Reporting of a disproportionality analysis for drug safety signal detection using ICSRs in pharmacovigilance) guideline.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Presentation of Patients with Intestinal Angioedema Based on Literature

A literature search yielded 250 articles, 94 in PubMed and 156 in Embase. After removing duplicates, 177 articles were available. Screening of the title and abstract resulted in 89 relevant articles, which provided details of 121 cases. Of these, age was reported for 117 patients (Supplementary Table S1). The median age of the patients was 48 years (interquartile range, 42–58 years; range, 19–92 years); 70.09% (82/117) were females. The most common indication for drug use was hypertension (72.65% [85/117]) with or without other comorbidities. Regarding time to onset after initiation of treatment with the suspect drug, 46.84% (37/79) cases had onset in less than a month, 20.25% (16/79) cases had onset between 1 month to 1 year, and in 32.91% (26/79) cases, onset was after 1 year or more. In 5 cases, the time to onset was unclear, and no data was available in 37 cases. Regarding time to resolution, it was within a day in 60.61% (40/66) cases, and between one day and one week in 39.39% (26/66) cases. No data was available in 36 cases.

The details of the cases with suspected ACE-I-induced angioedema are presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1. Of the 86 ACE inhibitor-related case reports, lisinopril was the most commonly implicated ACE-I (65.12%, 56/86). The discontinuation of the suspect medication was the only measure taken in 29 cases, without any additional treatment or management. ADR was frequently managed by administration of intravenous fluids (19 cases) and supportive care (14 cases). In four case reports, patients underwent unnecessary surgical interventions, such as exploratory laparotomy (suspected intestinal ischemia), cholecystectomy, and unspecified surgical interventions, as diagnosis was delayed without getting any relief from symptoms. The concomitant medications reported were diuretics (17 cases), statins (11 cases), acetylsalicylic acid (9 cases), amlodipine (6 cases), and metformin (6 cases). No similar past history and multiple past similar history was noted in 67 (83%) and 20 (24%) case reports, respectively. Past failed exploratory laparotomy and cholecystectomy were reported in two case reports. Positive rechallenge was noted in 5 out of 82 case reports (6%).

Table 1.

Summary of case reports of ACE-I induced intestinal angioedema.

Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2 present the details of cases of intestinal angioedema suspected to be induced by drugs other than ACE-Is. Among the 23 case reports, nonionic contrast medium was the most implicated drug. The discontinuation of the suspect medication was the only measure taken in 13 cases, without any additional treatment or management. ADR was frequently managed by hydration (5 cases) and bowel rest (4 cases). In one report of a patient who underwent injections of hyaluronic acid–based dermal fillers in the face and developed intestinal angioedema, the episode was successfully treated with injection hyaluronidase. No similar past history and multiple past similar history was noted in 17 (81%) and 6 case reports (19%), respectively. Positive rechallenge was noted in 3 out of 23 case reports (13%).

Table 2.

Summary of case reports of intestinal angioedema induced by drugs other than angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

3.2. Disproportionality Analysis

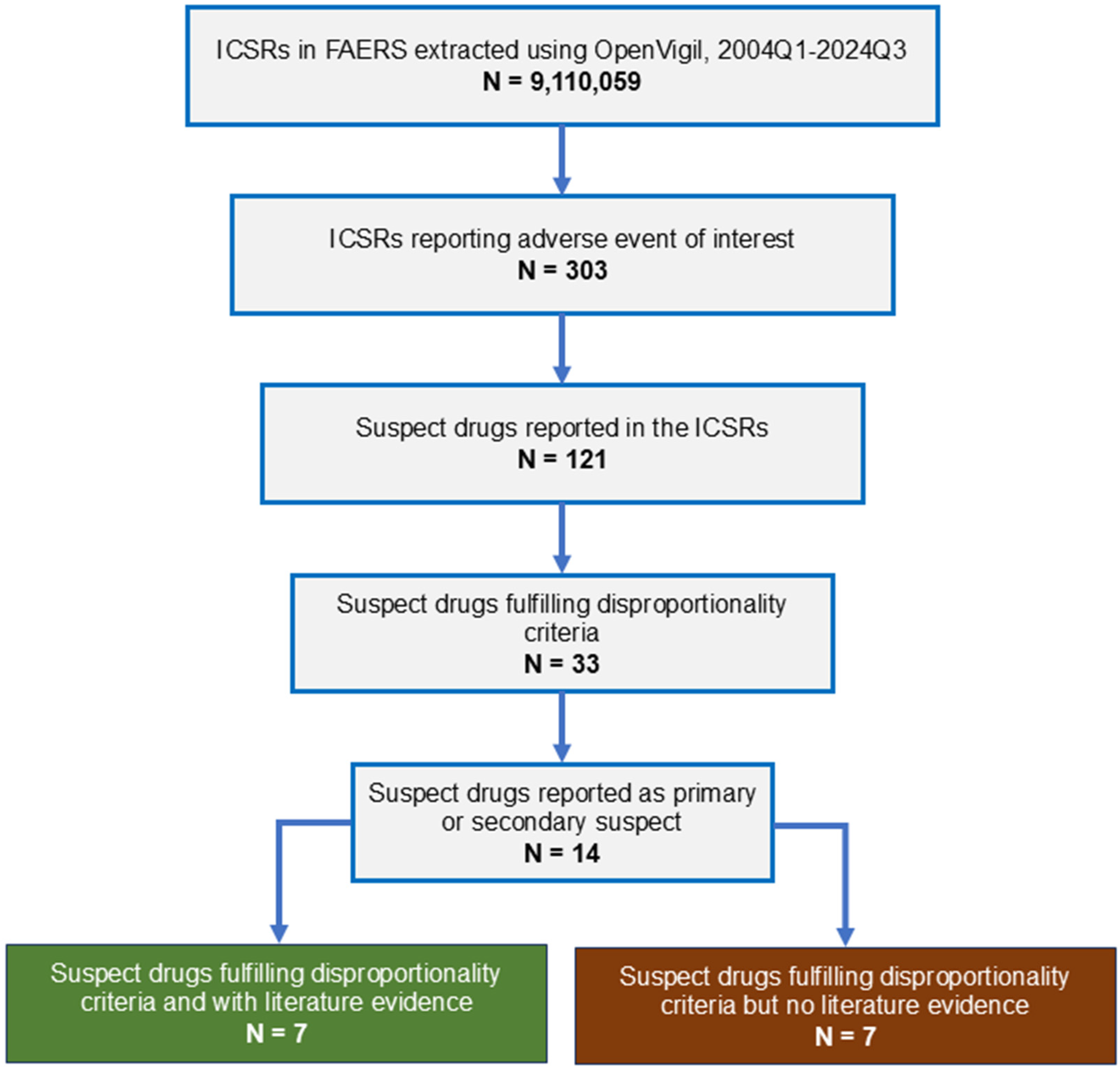

From 2004 to 2024, 9,110,059 adverse events were reported to FAERS (Figure 1). Three hundred and three cases of intestinal angioedema were reported. Age was reported in 277 ICSRs; the median age of the patients was 49 years (interquartile range, 41–61 years; range, 23–87 years); gender was reported in 282 ICSRs; 75.18% (212/282) were females. The most common indication for drug use was hypertension (72.69% [189/260]). None of the cases resulted in death.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. ICSR, individual case safety report; FAERS, Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System.

Thirty-three medications showed SDR for intestinal angioedema. Of these, 14 drugs were reported as primary or secondary suspect medications in one or more ICSRs. The disproportionality results for these medications are shown in Table 3. As seen, the maximum number of ICSRs were reported with lisinopril (254) followed by losartan and hydrochlorothiazide (38 each), pantoprazole (21), amlodipine (17), and nifedipine (15).

Table 3.

Suspect drugs showing signals of disproportionate reporting for intestinal angioedema with or without evidence from literature review.

Of the 14 suspect medications, case reports were available for 7 drugs, implicating them in the causation of intestinal angioedema (Table 4). Four of these were ACE-Is, and one was an angiotensin receptor blocker. The drugs for which supporting literature was not available were amlodipine, atorvastatin, clonidine, dicyclomine, metformin, nifedipine, and nisoldipine. However, some of these, such as amlodipine, atorvastatin, and metformin, were commonly reported as concomitant medications in the case reports.

Table 4.

Drugs with potential to cause intestinal angioedema as identified by literature search with or without signal of disproportionate reporting (SDR).

4. Discussion

Our study described the clinicodemographic profile of patients with suspected drug-induced intestinal angioedema and identified the potential causative drugs. The age and gender presentation as determined by the literature review and FAERS database analysis closely match each other, with most patients being middle-aged females with hypertension. Besides ACE-Is, particularly lisinopril, losartan, and acetylsalicylic acid are the other drugs with evidence both from disproportionality analysis and literature review. Of note, some drugs implicated in causing intestinal angioedema based on case reports did not show SDR; similarly, many drugs with SDR did not have supporting literature evidence. A number of the later drugs, although mentioned as suspect drugs in one or more ICSRs, were more often reported as concomitant medications, and therefore are likely to be false positives. Excluding the names of the 4 suspect drug groups (ACE-I, calcium channel blockers, hormone replacement therapy, nonionic contrast medium), literature review identified 19 unique drugs (Table 4) which potentially induced intestinal angioedema. Of these, hydrochlorothiazide and indapamide were reported in combination with lisinopril and perindopril, respectively. Of these, 7 drugs showed SDR on disproportionality analysis. However, 13 drugs, including hormone replacement therapy, did not appear in the disproportionality analysis results. Barring sirolimus, tacrolimus, and hyaluronic acid, the rest of the drugs were ACE-Is or angiotensin receptor blockers, or nonionic radiocontrast media. It is to be noted that ACE-Is and estrogen-containing medications, which have been reported to cause intestinal angioedema, are also known triggers for HAE attacks in susceptible patients [5].

The mechanisms leading to the development of angioedema, in general, include excess production or inability to degrade the vasoactive compounds like histamine, BK, and leukotrienes, resulting in increased vascular permeability [11]. Drug-induced angioedema can be of two types, allergic and nonallergic. Histamine, which is involved in type 1 IgE hypersensitivity reaction, is the initiating factor in allergic angioedema [114]. The most commonly implicated drugs are beta-lactam antibiotics, quinolones, and the iodinated contrast media [115]. NSAIDs and ACEIs are the commonly encountered drugs implicated in nonallergic angioedema [116]. The primary underlying mechanism with these drugs is interference with arachidonic acid metabolism by blocking cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme, increased production, and decreased metabolism of BK and C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency [115].

Histamine-mediated angioedema is a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction. Certain iodine and gadolinium-based contrast media can cause histamine-mediated angioedema by direct degranulation of mast cells and basophils [117,118]. It is also proposed that inhibition of COX enzyme by NSAIDs in arachidonic acid pathway leads to increased synthesis of leukotrienes, which increase vascular permeability and induce hyperresponsiveness to histamine [119,120].

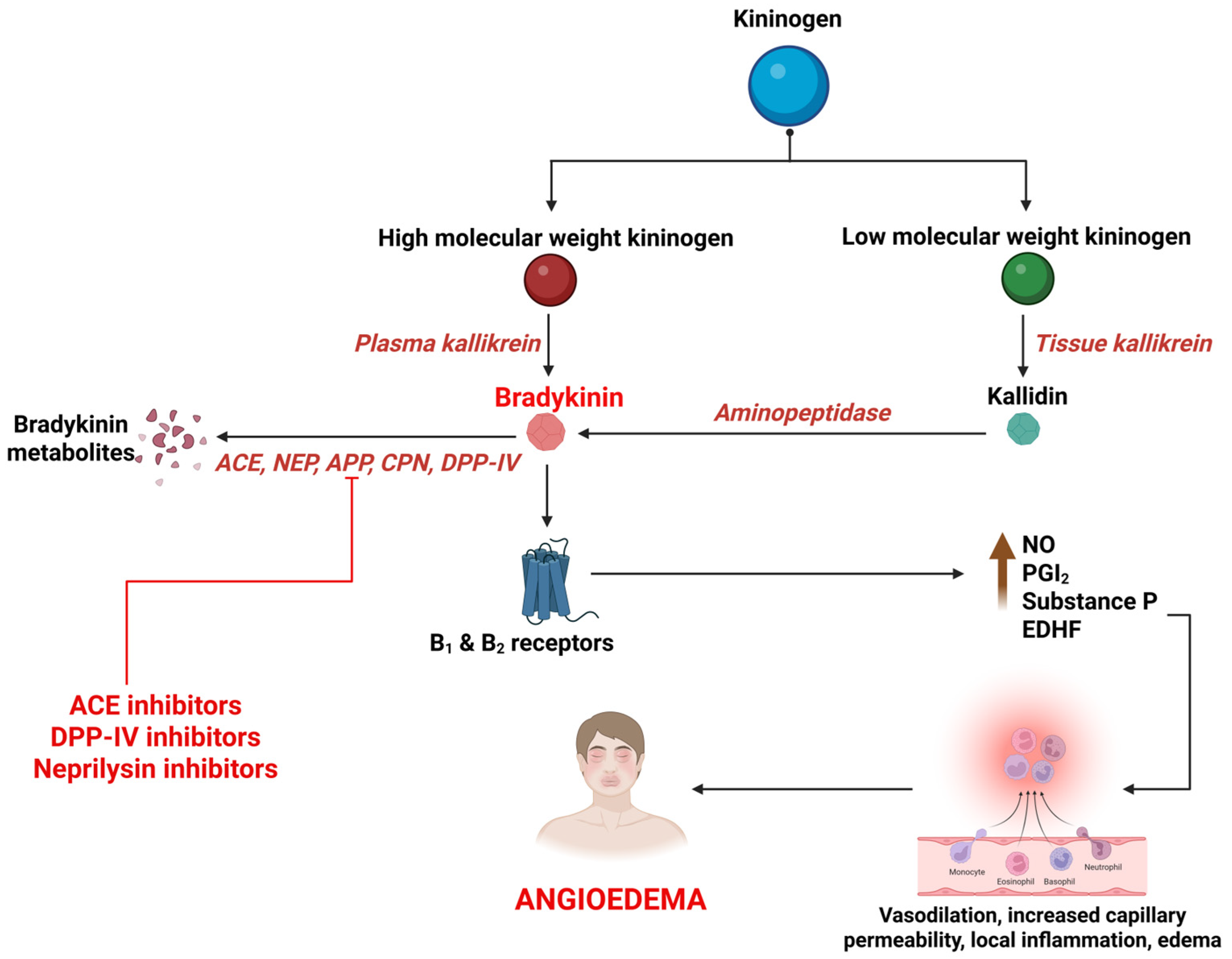

BK is a potent, short-acting vasoactive peptide that mediates inflammation and vasodilation in multiple signaling cascades. It is synthesized primarily through the activation of the kallikrein–kininogen system (KKS), by a protease called kallikrein [121,122]. BK then acts on BK receptor type 1 and 2 to mediate various actions that constitute the regulation of vascular tone, maintenance of kidney function, and defense against ischemic reperfusion damage. It also plays an important role in inflammation by releasing nitric oxide and prostaglandins, causing angioedema by increase in blood vessel permeability and diffusion of plasma into submucosal tissues [123,124,125,126] (Figure 2). BK is primarily degraded by Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE), neutral endopeptidase (NEP), aminopeptidase P (APP), carboxypeptidase N (CPN), dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV), and Kininase I. The primary enzyme, ACE (Kininase II), degrades BK to inactive metabolites. The ACEIs interfere with this process, leading to accumulation of BK. The metabolism of BK is taken over by secondary enzymes; deficiencies of these further interfere with the process of BK degradation, extending its action and culminating in angioedema [13,127] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Synthesis and breakdown of bradykinin and its association with drug-induced angioedema. B1, bradykinin receptor type 1; B2, bradykinin receptor type 2; NO, nitric oxide; PGI2, prostacyclin; EDHF, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; NEP, neutral endopeptidase; APP, aminopeptidase P; CPN, carboxypeptidase N; DPP-IV, dipeptidyl peptidase IV.

The exact mechanism for ARB-induced angioedema is not clearly understood. There are two postulated mechanisms in the literature. First, the ARBs exert a feedback rise in plasma levels of angiotensin II by suppressing the Angiotensin II type 1 (AT 1) receptor, and this causes self-inhibition of the ACE, causing BK accumulation and angioedema [10]. Second, ARBs block the AT 1 receptor and increase the angiotensin II levels, which then activates the AT 2 receptor and causes release of BK, resulting in angioedema [128].

The drug-induced angioedema linked to prostaglandin and leukotrienes occurs with NSAIDs. It’s a non-immunological reaction that involves the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway. The NSAIDs interfere with the metabolism of arachidonic acid through the inhibition of COX 1 and 2 pathways, which leads to a decrease in prostaglandin synthesis and loss of its beneficial effects and redirects the arachidonic acid towards the 5-lipoxygenase pathway. This leads to the release of cysteinyl leukotrienes, which is a vasoactive substance, causing an increase in vascular permeability and edema, resulting in the development of angioedema. Though the primary mechanism for NSAID-induced angioedema is COX inhibition, mast cell and basophil degranulation that release chemical mediators like histamine can contribute to the above mechanism [115,129].

The importance of this study lies in the fact that many cases of drug-induced intestinal angioedema experienced significant delays in diagnosis and underwent unnecessary diagnostic or therapeutic interventions, including surgeries. The presence of cases of multiple episodes of positive rechallenge indicates the lack of adequate awareness among the treating physicians. Since there is evidence that most of the patients experienced complete resolution following discontinuation of the suspect drug with or without supportive measures, having a list of potential suspect medication will aid in proper management of the condition.

The strength of our study is that we systematically combined the disproportionality analysis approach with literature review to overcome the limitations associated with FAERS data, in particular the presence of false positives. The similarity in the clinicodemographic profiles of the patients from FAERS and the published literature strengthens the observation that drug-induced intestinal angioedema predominantly affects middle-aged females. However, the study also has limitations. While we supplemented adverse event database analysis with literature review, given that intestinal angioedema is not very common and difficult to diagnose without an index of suspicion, significant underreporting of cases cannot be ruled out. This is more likely to impact drugs other than ACE-Is, which are not known to cause the event. Another important limitation is the potential for reporting bias, where medications may be incorrectly classified as suspect or concomitant. This can lead to false associations or missed signals. For instance, commonly co-prescribed drugs such as amlodipine and metformin were frequently listed as concomitant medications in case reports, yet showed signals of disproportionate reporting, raising the possibility of confounding. These medications are commonly prescribed alongside antihypertensives, particularly ACE inhibitors, which are known to cause intestinal angioedema. Their frequent co-prescription likely contributes to their appearance in FAERS reports. Importantly, no case reports were found implicating these drugs as causative agents, and they were often listed as concomitant medications. This highlights the need for cautious interpretation of SDRs and underscores the importance of integrating literature evidence to validate pharmacovigilance signals. We studied a single adverse event database. Inclusion of other international databases, such as EudraVigilance or VigiBase, could provide a broader perspective and potentially identify additional signals. However, differences in coding practices, drug availability, and reporting behaviors across regions may introduce heterogeneity and bias, complicating direct comparisons. Future studies incorporating multiple pharmacovigilance databases could help validate the findings and improve generalizability.

5. Conclusions

The available evidence suggests that in the vast majority of cases of drug-induced intestinal angioedema, the diagnosis was often delayed until after several similar episodes. Antibiotics and emergency surgery have been attempted in multiple instances, with unsuccessful outcomes. Symptoms appear immediately after administration of contrast medium or within a month to a year after starting other drugs. Discontinuation of the suspect drug enabled the complete recovery of all patients within hours to a few days. Literature review and adverse event database evidence reveal that the causative drugs, besides the commonly reported ACE-Is, particularly lisinopril, are angiotensin receptor blockers and acetylsalicylic acid. Some drugs, such as oestrogen, radiocontrast media, and immunosuppressants, are potential suspect medications despite the absence of evidence from disproportionality analysis.

The results of this study will assist health professionals in determining the temporal association of acute abdomen with the suspected drug, thereby potentially avoiding unnecessary interventions and their attendant complications. Given the diagnostic challenges and frequent misattribution of symptoms to surgical or infectious causes, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for drug-induced intestinal angioedema, especially in patients presenting with recurrent abdominal pain and a history of ACE inhibitor or ARB use. Early recognition can prevent unnecessary imaging, antibiotic therapy, and surgical procedures such as exploratory laparotomy. Prescribers should consider discontinuation of the suspect drug as a first-line response when intestinal angioedema is suspected, and monitor for rapid symptom resolution. Incorporating awareness of this adverse event into routine clinical assessment may improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce patient morbidity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/medsci13040327/s1.

Author Contributions

A.K. and P.B.R. conceptualized and designed the study; R.R.R. created the artwork; A.K. supervised and made critical revisions; P.B.R. and R.R.R. conducted the literature review; A.K. did the analysis and interpretation of data; P.B.R. and R.R.R. drafted the original manuscript; all authors prepared the draft and approved the submitted version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Kasturba Medical College Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC KMCMLR-01/2025/23). Approval date: 16 January 2025. Informed consent was not required for this study because the study used de-identified data from a database accessible to the public.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. These data were derived from the following resource available in the public domain: United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) (https://www.fda.gov/drugs/surveillance/fdas-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers (accessed on 5 September 2025)).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support provided by Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India, in accessing the scientific databases.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Pal, N.L.; Fernandes, Y. Intestinal Angioedema: A Mimic of an Acute Abdomen. Cureus 2023, 15, e34619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.; Rice, L. “Surgical” Abdomen in a Patient with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Case of Acquired Angioedema. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2011, 15, 2262–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nzeako, U.C. Diagnosis and Management of Angioedema with Abdominal Involvement: A Gastroenterology Perspective. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 4913–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Suarez, L.D.; Kapur, S.; Bielory, L. Hereditary Angioedema and Gastrointestinal Complications: An Extensive Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Immunol. 2015, 2015, 925861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnowski, J.; Treudler, R. Dietary and Physical Trigger Factors in Hereditary Angioedema: Self-Conducted Investigation and Literature Overview. Allergol. Sel. 2024, 8, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, T.N.A.; Hua, L.; Smalberger, J.A.; James, J. ACE Inhibitor Induced Intestinal Angioedema. ANZ J. Surg. 2022, 92, 3110–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obtułowicz, K. Bradykinin-Mediated Angioedema. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2016, 126, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barnes, P.J. Effect of Bradykinin on Airway Function. Agents Actions. Suppl. 1992, 38 Pt 3, 432–438. [Google Scholar]

- Sravanthi, M.V.; Suma Kumaran, S.; Sharma, N.; Milekic, B. ACE Inhibitor Induced Visceral Angioedema: An Elusive Diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e236391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudit, G.; Girgrah, N.; Allard, J. ACE Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema of the Intestine: Case Report, Incidence, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2001, 15, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigami, K.; Averill, S.L.; Pollard, J.H.; McDonald, J.M.; Sato, Y. Radiologic Manifestations of Angioedema. Insights Imaging 2014, 5, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korniyenko, A.; Alviar, C.L.; Cordova, J.P.; Messerli, F.H. Visceral Angioedema Due to Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor Therapy. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2011, 78, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thalanayar, P.M.; Ghobrial, I.; Lubin, F.; Karnik, R.; Bhasin, R. Drug-Induced Visceral Angioedema. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2014, 4, 25260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Shu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, F.; Li, J. A Real-World Pharmacovigilance Study of FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Events for Osimertinib. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppsala Reports—Record Growth Pushes VigiBase Past 28 Million Reports. Available online: https://uppsalareports.org/articles/record-growth-pushes-vigibase-past-28-million-reports/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Yu, R.J.; Krantz, M.S.; Phillips, E.J.; Stone, C.A. Emerging Causes of Drug-Induced Anaphylaxis: A Review of Anaphylaxis-Associated Reports in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 819–829.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, R.; von Hehn, L.; Herdegen, T.; Klein, H.-J.; Bruhn, O.; Petri, H.; Höcker, J. OpenVigil FDA—Inspection of U.S. American Adverse Drug Events Pharmacovigilance Data and Novel Clinical Applications. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, A. Exploratory Disproportionality Analysis of Potentially Drug-Induced Eosinophilic Pneumonia Using United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myslinski, J.; Heiser, A.; Kinney, A. Hypovolemic Shock Caused by Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Visceral Angioedema: A Case Series and A Simple Method to Diagnose This Complication in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 54, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoger, S.H.; Sayed, M.A. Simultaneous Mucosal and Small Bowel Angioedema Due to Captopril. South. Med. J. 1998, 91, 1060–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, A.S.; Schranz, C. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema of the Small Bowel-A Surgical Abdomen Mimic. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 48, e127–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, K.K.; Myers, J.R. Intermittent Visceral Edema Induced by Long-Term Enalapril Administration. Ann. Pharmacother. 2004, 38, 825–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillion, V.; Dragean, C.A.; Dahlqvist, G.; Jadoul, M. Intestinal Angioedema from Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruetman, J.E.; Montes Onganía, A.; Finn, B.C.; Young, P. Isolated intestinal angioedema induced by enalapril. Medicina 2018, 78, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Syed, M.; Rey-Mendoza, J.; Simons-Linares, R.C.; Stroger, J.H. Isolated Small Intestine Angioedema: An Under-Recognized Complication of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor Therapy: 2504. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2017, 112, S1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, R.J.; Shanahan, T.M.; Dobson, R.T. Visceral Angioedema Related to Treatment with an ACE Inhibitor. Med. J. Aust. 1996, 165, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutnuri, S.; Khan, A.; Variyam, E.P. Visceral Angioedema: An under-Recognized Complication of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. Postgrad. Med. 2015, 127, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeu Vilar, D.; López Rey, D. Angioedema of the small bowel secondary to treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. Radiologia 2015, 57, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, E.I.; Mishra, G.; Abdelmalek, M.F. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Isolated Visceral Angioedema in a Liver Transplant Recipient. Transplantation 2003, 75, 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahn, T.W.; Grosse-Thie, W.; Mueller, M.K. Endoscopic Visualization of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Small Bowel Angioedema as a Cause of Relapsing Abdominal Pain Using Double-Balloon Enteroscopy. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2008, 53, 1257–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Li, Y. Gastrointestinal: Small Intestinal Angioedema Induced by Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 39, 1967–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincic Antulov, M.; Båtevik, R.B. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Gastrointestinal Angioedema: The First Danish Case Report. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2018, 12, 556–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, T.J.; Douglas, D.D.; Landis, M.E.; Heppell, J.P. Isolated Visceral Angioedema: An Underdiagnosed Complication of ACE Inhibitors? Mayo Clin. Proc. 2000, 75, 1201–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augenstein, V.A.; Heniford, B.T.; Sing, R.F. Intestinal Angioedema Induced by Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors: An Underrecognized Cause of Abdominal Pain? J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2013, 113, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Razzano, A.; Alagheband, S.; Ahmed, H.; Malet, P.; Katz, D. Isolated Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitor Induced Small Bowel Angioedema After 10 Years of Oral Lisinopril Therapy: 2211. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2016, 111, S1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, L.; Ahmed, A.; Grossman, E. Isolated Intestinal Involvement of Angioedema Induced by ACE Inhibitor: 332. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2013, 108, S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmquist, S.; Mathews, B. Isolated Intestinal Type Angioedema Due to ACE-Inhibitor Therapy. Clin. Case Rep. 2017, 5, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voore, N.; Stravino, V. Isolated Small Bowel Angio-Oedema Due to ACE Inhibitor Therapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2015212623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, T.J.; Tran, L. Isolated Visceral Angioedema: An Uncommon Complication of ACEI Therapy: 2495. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2017, 112, S1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarze, J.C.; Sablich, D. Lisinopril-Induced Small Bowel Angioedema: 2511. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2017, 112, S1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.W.; Rydburg, A.M.; Do, V.D. Lisinopril-Induced Small Bowel Angioedema: An Unusual Cause of Severe Abdominal Pain. Am. J. Case Rep. 2022, 23, e937895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, I.; Shaheen, A.A.; Edhi, A.I.; Cappell, M.S. S2882 Mesenteric Angioedema Induced by Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2020, 115, S1445–S1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuthnow, C.; Bharwad, A.; Rowe, K. S3458 Often Reported, Rarely Considered: A Case of ACEI-Induced Mesenteric Angioedema. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2022, 117, e2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, E.C.; Wall, G.C. Possible Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEI)-Induced Small Bowel Angioedema. J. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 24, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, J.G.; Vedantam, V.; Kapila, A.; Bajaj, K. Recognizing a Rare Phenomenon of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors: Visceral Angioedema Presenting with Chronic Diarrhea—A Case Report. Perm. J. 2018, 22, 17-030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abstracts from the 37th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 1–545. [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aggarwal, A.; Mehta, N.; Shah, S.N. Small Bowel Angioedema Associated with Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor Use. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 446–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabh, H.; Hahn, B.; Bryan, C.; Hogg, J.; Kupec, J.T. Small Bowel Angioedema from Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme: Changes on Computed Tomography. Radiol. Case Rep. 2018, 13, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; Yu, K.K.; Mayilvaganan, B. S4714 Small Bowel Angioedema Secondary to ACE Inhibitor. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2024, 119, S2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inayat, F.; Hurairah, A. Small Bowel Angioedema Secondary to Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. Cureus 2016, 8, e943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uy, P.P.; Yap, J.E. 2601 Small Intestine Angioedema Due to Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors: A Great Mimicker. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2019, 114, S1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaff, L.C.G.; van Essen, M.; Schipper, E.M.; Boom, H.; Duschek, E.J.J. Unnecessary Surgery for Acute Abdomen Secondary to Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor Use. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 30, 1607–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharwad, A.; Wuthnow, C.; Mahdi, M.; Rowe, K. Unresolved Chronic Diarrhea: A Case of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Mesenteric Angioedema. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2023, 10, 003995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, J.; Balagoni, H.; Kapila, A.; Bajaj, K. Visceral Angioedema: A Rare Complication of ACE Inhibitors Causing Chronic Diarrhea: 2073. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2016, 111, S990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Case Isolated Intestinal Angioedema—Record Details—Embase. Available online: https://www.embase.com/records?subaction=viewrecord&rid=9&page=1&id=L636473581 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Pirzada, S.; Raza, B.; Mankani, A.A.; Naveed, B. A Case of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitor-Induced Small Bowel Angioedema. Cureus 2023, 15, e47739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niyibizi, A.; Cisse, M.S.; Rovito, P.F.; Puente, M. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema of the Small Bowel: A Diagnostic Dilemma. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2023, 36, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilin, K.L.; Czupryn, M.J.; Mui, R.; Renno, A.; Murphy, J.A. ACE Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema of the Small Bowel: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 31, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, M.B.; Vecchio, M.; Santos, M.A. A Gut Feeling: Isolated Small Bowel Angioedema Due to Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor. Rhode Isl. Med. J. 2022, 105, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, E.; Baqal, O.; LeMond, L. A Rare Case of ACE Inhibitor-Induced Intestinal Angioedema Presenting as a Delayed Complication in a Heart Transplant Recipient. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2022, 41, S458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.A.; Alves, M.R.; Oliveira, A.M.P.; Silva, F.S.S.; Pereira, C. A Rare Cause of Abdominal Pain: Intestinal Angioedema. J. Med. Cases 2021, 12, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squillante, M.D.; Trujillo, A.; Norton, J.; Bansal, S.; Dragoo, D. ACE Inhibitor Induced Isolated Angioedema of the Small Bowel: A Rare Complication of a Common Medication. Case Rep. Emerg. Med. 2021, 2021, 8853755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, D.; Strohbehn, G.W.; Cascino, T. ACE inhibitor-Associated Intestinal Angioedema in Orthotopic Heart Transplantation. ESC Heart Fail. 2017, 4, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez, M.; Grosel, J.M. ACE Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema Causing Small Bowel Obstruction. J. Am. Acad. Physician Assist. 2020, 33, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, S.; Van Meerbeeck, S.; De Pauw, M. ACE Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema of the Small Intestine: A Case Report. Acta Cardiol. 2011, 66, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahani, L. ACE Inhibitor-Induced Intestinal Angio-Oedema: Rare Adverse Effect of a Common Drug. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013200171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ace Inhibitor-Induced Visceral Angioedema-a Rare Phenomenon—Record Details—Embase. Available online: https://www.embase.com/records?subaction=viewrecord&rid=1&page=1&id=L630841473 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Acute Abdomen Due to Large Bowel Angioedema Caused by Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor—Record Details—Embase. Available online: https://www.embase.com/records?subaction=viewrecord&rid=1&page=1&id=L70698275 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Goyal, J.; Weber, F. Alimentary, My Dear Watson! ACE Inhibitor-Induced Bowel Angioedema: 1071. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2014, 109, S318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Ace Inhibitor of Spades: An Unsual Cause of Enteritis—Record Details—Embase. Available online: https://www.embase.com/records?subaction=viewrecord&rid=1&page=1&id=L71878150 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- An Unusual Case of Recurrent Abdominal Pain: Ace Inhibitor Induced Visceral Angioedema—Record Details—Embase. Available online: https://www.embase.com/records?subaction=viewrecord&rid=1&page=1&id=L636474361 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Krause, A.J.; Patel, N.B.; Morgan, J. An Unusual Presentation of ACE Inhibitor-Induced Visceral Angioedema. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e230865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujer, M.T.P.; Rai, M.P.; Nemakayala, D.R.; Yam, J.L. Angioedema of the Small Bowel Caused by Lisinopril. Drug Ther. Bull. 2019, 57, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.S.; Sorrentino, D. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor Induced Small Bowel Angioedema. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adusumilli, R.K.; Patel, M.; Hong, G.; Kulairi, Z.I. 2631 Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Isolated Angioedema of Small Bowel. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2019, 114, S1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Intestinal Angioedema: A Rare Side Effect of a Common Drug—Record Details—Embase. Available online: https://www.embase.com/records?subaction=viewrecord&rid=1&page=1&id=L2027228533 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Marmery, H.; Mirvis, S.E. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Visceral Angioedema. Clin. Radiol. 2006, 61, 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, M.; Sada, R. Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Intestinal Angioedema. Intern. Med. 2015, 54, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, S.; Benjamin, A.; Khattab, A.; Fine, M. S3021 Development of Isolated Intestinal Angioedema 10 Years After Initiation of Lisinopril. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2021, 116, S1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastroenterologist’s Recognition of Rare Adverse Drug Effect Prevents Further Harm in a Patient with Small Bowel Obstruction Due to Lisinopril: A Case Report and Literature Review—Record Details—Embase. Available online: https://www.embase.com/records?subaction=viewrecord&rid=1&page=1&id=L646034839 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Jani, C.; Walker, A.; Ahmed, A.; Rupal, A.; Patel, D.; Agarwal, L.; Al Omari, O.; Bhatia, K.; Dar, A.Q.; Singh, H.; et al. Lisinopril Induced Visceral Angioedema. Res. Health Sci. 2021, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, M.; Murata, Y.; Rikimaru, Y.; Sasaki, Y. Drug-Induced Isolated Visceral Angioneurotic Edema. Intern. Med. 2005, 44, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sehmbey, G.; Mann, S.; Seetharam, A. 2644 ACE Inhibitor-Induced Visceral Angioedema—A Rare Phenomenon. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2019, 114, S1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, H.; Locher, C.; Chenard, A.; Bigorie, B.; Beroud, P.; Gatineau-Sailliant, G.; Glikmanas, M. Small bowel angioedema due to perindopril. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 2005, 29, 1180–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECIM. Abstract Book of the 18th Conference in Internal Medicine. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutuoso, B.; Esteves, J.; Silva, M.; Gil, P.; Carneiro, A.C.; Vale, S. Visceral Angioedema Induced by Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor: Case Report. GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 23, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACE Inhibitor-Induced Small Bowel Angioedema, Mimicking an Acute Abdomen—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33072254/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Dobbels, P.; Van Overbeke, L.; Vanbeckevoort, D.; Hiele, M. Acute Abdomen Due to Intestinal Angioedema Induced by ACE Inhibitors: Not so Rare? Acta Gastroenterol. Belg. 2009, 72, 455–457. [Google Scholar]

- Acute Abdominal Pain in a Patient Taking ACE-I—Record Details—Embase. Available online: https://www.embase.com/records?subaction=viewrecord&rid=1&page=1&id=L71279815 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Wojciechowska, E.; Gryglas, P.; Dul, P. Gastrointestinal Angioneurotic Edema as a Consequence of Angiotensin—Converting Enzyme Inhibitor Treatment. J. Hypertens. 2023, 41, e312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietler, V.; Fusi-Schmidhauser, T. Intestinal Angioedema in a Palliative Care Setting. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, e293–e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.M.; Santiago, I.; Carvalho, R.; Martins, A.; Reis, J. Isolated Visceral Angioedema Induced by Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor. GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 23, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weingärtner, O.; Weingärtner, N.; Böhm, M.; Laufs, U. Bad Gut Feeling: ACE Inhibitor Induced Intestinal Angioedema. BMJ Case Rep. 2009, 2009, bcr0920080868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Y.; Sekhon, N.; Sharma, N.; Ramakrishna, S.; Ochieng, P. 587: Recurrent Bowel Angioedema Diagnosed Retrospectively After Oropharyngeal Angioedema. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 50, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, G.; Korsten, M.A.; Blatt, C.; Motwani, P. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-Associated Angioedema of the Stomach and Small Intestine: A Case Report. Mt. Sinai J. Med. N. Y. 2006, 73, 1123–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Abstracts Presented at Poster Sessions November 7–8, 2009 Miami Beach Convention Center. Ann. Allergy. Asthma. Immunol. 2009, 103, A93–A146. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Baig, M.A.; Javed, R.A.; Ali, S.; Qamar, U.R.; Vasavada, B.C.; Khan, I.A. Benazepril Induced Isolated Visceral Angioedema: A Rare and under Diagnosed Adverse Effect of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. Int. J. Cardiol. 2007, 118, e68–e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingos, N.; Tjandra, D.; Lim, B.; Hebbard, G. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Small Bowel Angioedema: An Important Differential for Episodic Enteritis. ACG Case Rep. J. 2022, 9, e00877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.-H.; Gong, X.-Y.; Hu, P. Transient Small Bowel Angioedema Due to Intravenous Iodinated Contrast Media. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-K.; Chang, H.-T.; Chen, C.-W.; Lee, R.-C.; Sheu, M.-H.; Wu, M.-H.; Chou, H.-P.; Shen, Y.-C.; Chiu, N.-C.; Chang, C.-Y. Dynamic Computed Tomography of Angioedema of the Small Bowel Induced by Iodinated Contrast Medium: Prompted by Coughing-Related Motion Artifact. Clin. Imaging 2012, 36, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.W.; Bae, I.Y.; Eun, H.W.; Park, H.W.; Choe, J.W. Small-Bowel Angioedema during Screening Computed Tomography Due to Intravenous Contrast Material. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2011, 35, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maarek, R.; Sellier, N.; Seror, O.; Sutter, O. Small Bowel Angioedema Due to Intravenous Administration of Gadobenate Dimeglumine. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2019, 100, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Cho, J.Y.; Lim, H.K. CT Findings of Isolated Small Bowel Angioedema Due to Iodinated Radiographic Contrast Medium Reaction. Abdom. Imaging 1999, 24, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, O.; Sacco, K.; Wang, M.-H. Losartan-Induced Intestinal Angioedema: 2169. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2016, 111, S1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majoni, S.W.; Smith, S.R. Membranous Nephropathy in a Patient with Hereditary Angioedema: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2008, 2, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavers, C.J.; Dunn, S.P.; Macaulay, T.E. The Role of Angiotensin Receptor Blockers in Patients with Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Induced Angioedema. Ann. Pharmacother. 2011, 45, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi, C.L.A.; Ghezzi, T.L.; Corleta, O.C. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors-Induced Angioedema of the Small Bowel Mimicking Postoperative Complication. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2017, 109, 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Malcolm, A.; Prather, C.M. Intestinal Angioedema Mimicking Crohn’s Disease. Med. J. Aust. 1999, 171, 418–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, K.; Kendi, A.T.; Maselli, D. Isolated Angioedema of the Bowel Caused by Aspirin. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 1096–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, A.F.; White, J.A.; Kulaga, M.E.; Skluth, M.; Gruss, C.B. Calcium Channel Blocker-Associated Small Bowel Angioedema. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2009, 43, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alawami, A.Z.; Tannous, Z. Late Onset Hypersensitivity Reaction to Hyaluronic Acid Dermal Fillers Manifesting as Cutaneous and Visceral Angioedema. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 1483–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, W.; Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L. Sirolimus-Induced Severe Small Bowel Angioedema: A Case Report. Medicine 2018, 97, e12029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvidi, I.; Gal, E.; Rachamimov, R.; Niv, Y. Tacrolimus-Induced Intestinal Angioedema: Diagnosis by Capsule Endoscopy. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2007, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalambay, J.; Ghazanfar, H.; Martes Pena, K.A.; Munshi, R.A.; Zhang, G.; Patel, J.Y. Pathogenesis of Drug Induced Non-Allergic Angioedema: A Review of Unusual Etiologies. Cureus 2017, 9, e1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inomata, N. Recent Advances in Drug-Induced Angioedema. Allergol. Int. 2012, 61, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Niu, K.; Wu, X.; Shi, H. Risk of Drug-Induced Angioedema: A Pharmacovigilance Study of FDA Adverse Event Reporting System Database. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1417596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia Bara, M.T.; Gallardo-Higueras, A.; Moreno, E.M.; Laffond, E.; Muñoz Bellido, F.J.; Martin, C.; Sobrino, M.; Macias, E.; Arriba-Méndez, S.; Castillo, R.; et al. Hypersensitivity to Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media. Front. Allergy 2022, 3, 813927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kun, T.; Jakubowski, L. Influence of MRI Contrast Media on Histamine Release from Mast Cells. Pol. J. Radiol. 2012, 77, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynaert, G.; Grooten, J.; van Deventer, S.J.; Peppelenbosch, M.P. Cysteinyl Leukotrienes Mediate Histamine Hypersensitivity Ex Vivo by Increasing Histamine Receptor Numbers. Mol. Med. 1999, 5, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala-Cunill, A.; Guilarte, M. The Role of Mast Cells Mediators in Angioedema Without Wheals. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2015, 2, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, D.A.B.; Vaid, N.; Deepak, K.; Dagamajalu, S.; Prasad, T.S.K. A Comprehensive Review on Current Understanding of Bradykinin in COVID-19 and Inflammatory Diseases. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 9915–9927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, A.P.; Joseph, K.; Silverberg, M. Pathways for Bradykinin Formation and Inflammatory Disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002, 109, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.J. Neprilysin Inhibitors and Bradykinin. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoola, K.D.; Figueroa, C.D.; Worthy, K. Bioregulation of Kinins: Kallikreins, Kininogens, and Kininases. Pharmacol. Rev. 1992, 44, 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, M.; Adams, V.; Suvorava, T.; Niehues, T.; Hoffmann, T.K.; Kojda, G. Nonallergic Angioedema: Role of Bradykinin. Allergy 2007, 62, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.D.; MacFarlane, R.C.; Mulligan, A.N.; Scafidi, J.; Davis, A.E. Increased Vascular Permeability in C1 Inhibitor-Deficient Mice Mediated by the Bradykinin Type 2 Receptor. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudey, S.N.; Westermann-Clark, E.; Lockey, R.F. Cardiovascular and Diabetic Medications That Cause Bradykinin-Mediated Angioedema. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2017, 5, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irons, B.K.; Kumar, A. Valsartan-Induced Angioedema. Ann. Pharmacother. 2003, 37, 1024–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Borges, M.; Capriles-Hulett, A.; Caballero-Fonseca, F. NSAID-Induced Urticaria and Angioedema: A Reappraisal of Its Clinical Management. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2002, 3, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).