1. Context and Aims of the Special Issue

Geomorphological hazards such as landslides, debris flows, coastal erosion, and slope collapses are among the world’s most pervasive natural threats, with worsening impacts on lives, livelihoods, and infrastructures in terms of deaths and economic losses. The World Bank estimates that disasters cost the global economy USD 520 billion annually. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, the global plan to reduce disaster losses adopted on 18 March 2015 at the Third UN World Conference in Sendai (Japan), highlighted a practical mandate: know where, when, and how hazards evolve, then act before they escalate. Remote Sensing (RS), spanning ground-based cameras [1], UAV photogrammetry/LiDAR [2], multispectral and hyperspectral satellites [3,4,5], InSAR [6], and thermal imaging [5], has matured into an indispensable toolkit for that mandate, enabling continuous, spatially extensive, and increasingly rapid monitoring across a spectrum of temporal and spatial scales [7]. This Special Issue (SI) was conceived to showcase state-of-the-art research and to illustrate how innovations in sensors, platforms, and analytical workflows are moving geohazard science from episodic observation toward proactive risk governance.

Across the six contributions, one technical note and five articles, already published, three common threads emerge: (i) the use of multi-sensor integration to capture complex processes at an appropriate resolution; (ii) the use of quantitative change detection, whether via DEM differencing, spectral unmixing, or image correlation, to turn pixels into physics; and (iii) emphasis on operational aspects in terms of protocols, accuracies, and decision-ready products for emergency response, early warning, and long-term mitigation. Below, we synthesize the contributions, which vary from coastal cliffs and mud eruptions to rainstorm-triggered and small-scale landslides, highlighting where the field is heading next. Table 1 summarizes the RS data, the processing techniques used in each paper, and the general purpose of the presented research.

Table 1.

An overview of the RS data, techniques, purposes, and natural hazard types presented in the papers comprising this Special Issue. Access links to each paper are also provided, together with their DOI numbers.

1.1. Statistics

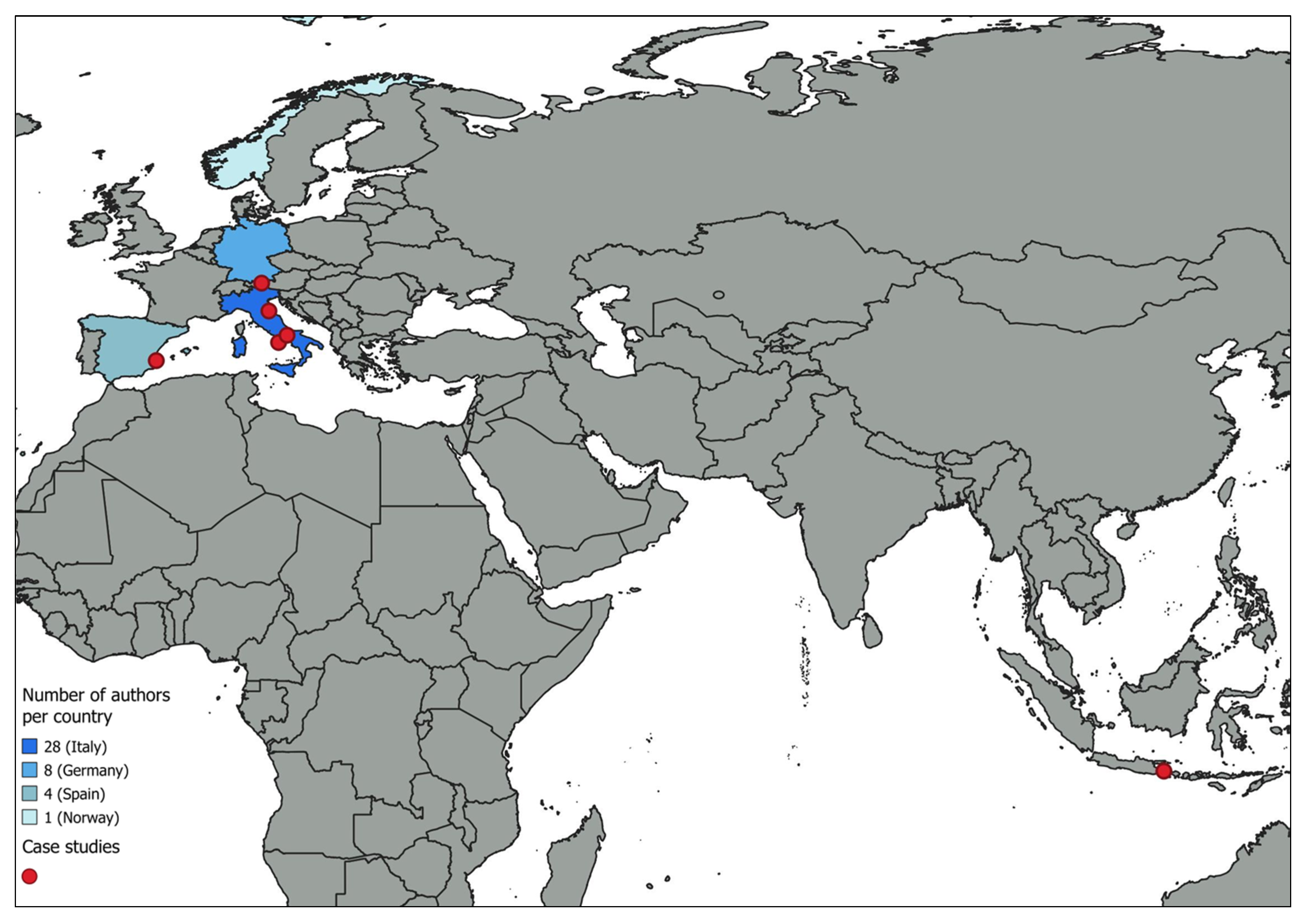

The Special Issue includes 6 papers authored by 41 researchers from 4 countries based on their affiliation (Italy, Germany, Norway and Spain; Figure 1), with an average of 6.8 contributors per article. The case studies were conducted in Italy (one in Emilia-Romagna and two in Campania), Spain (Alicante), Austria (Tyrol), and Indonesia (East Java).

Figure 1.

An overview of the authors’ affiliation by country, together with the locations of the case studies discussed in this Special Issue.

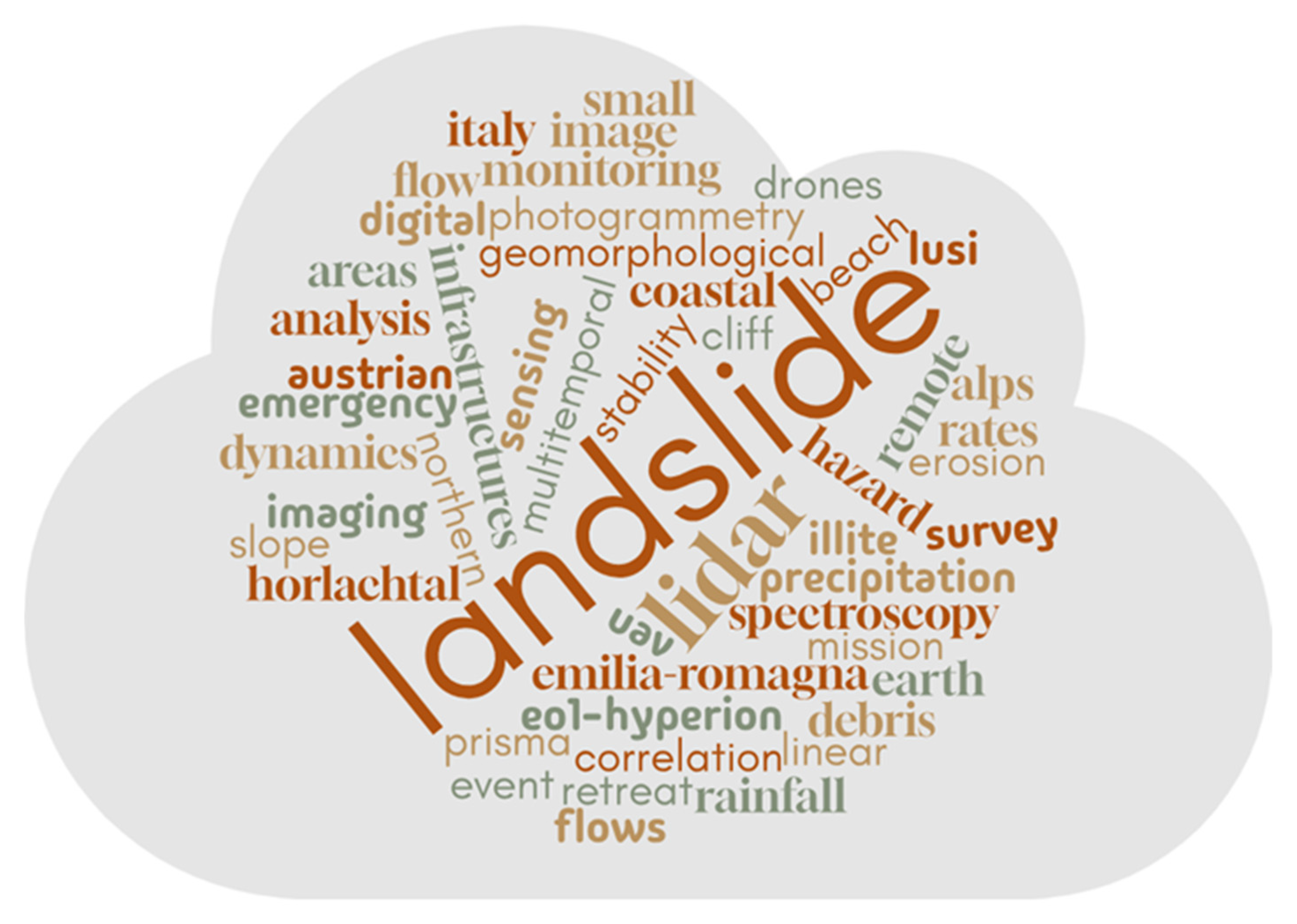

The most commonly recurring words among the keywords chosen by the authors are shown in the word cloud in Figure 2; among them, “landslide” was selected four times, followed by “LiDAR”.

Figure 2.

A word cloud (also known as a text cloud or tag cloud) generated from the keywords of all contributions to this Special Issue. The more a word appears as a keyword, the bigger and bolder it appears in the word cloud.

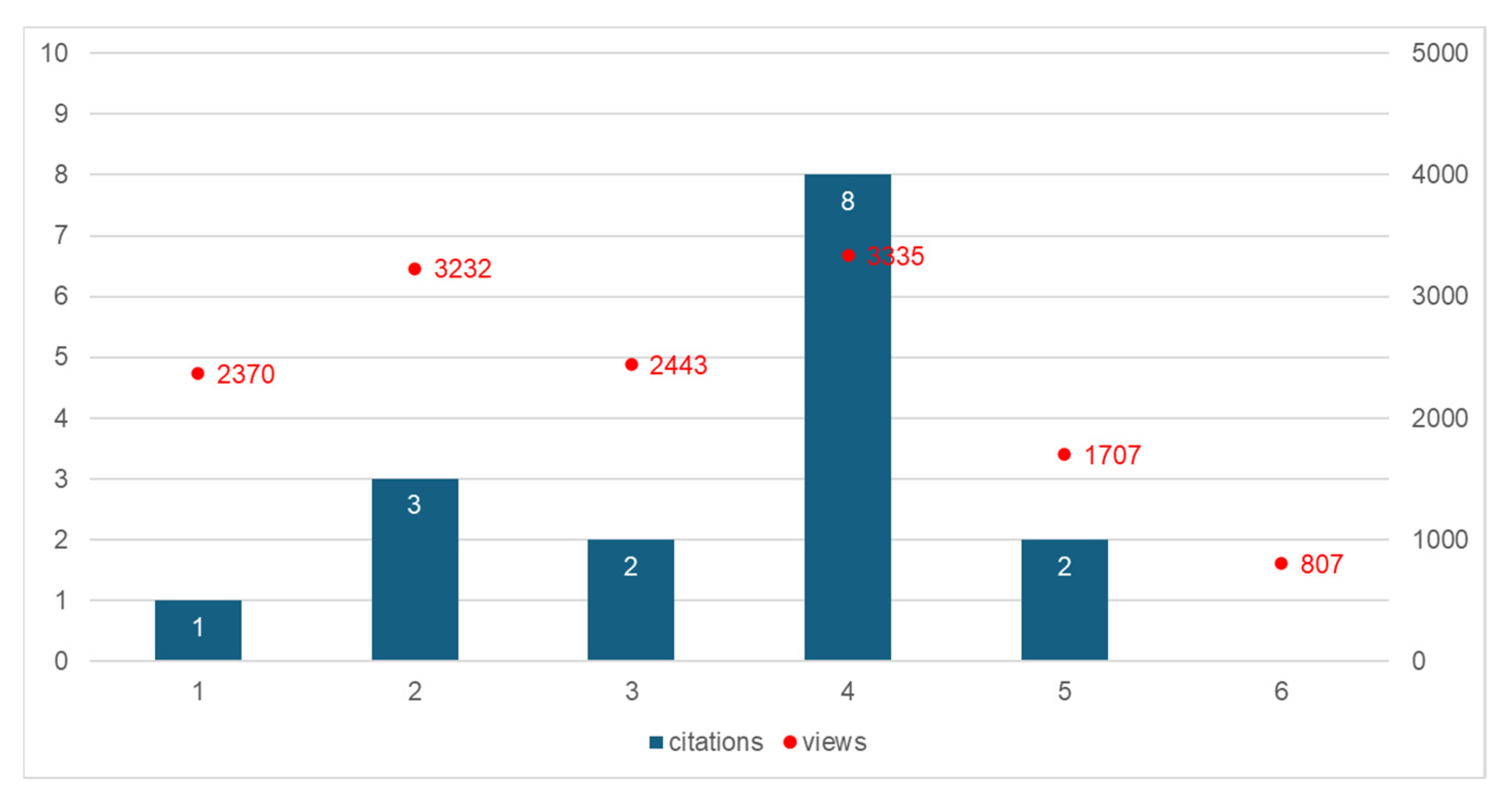

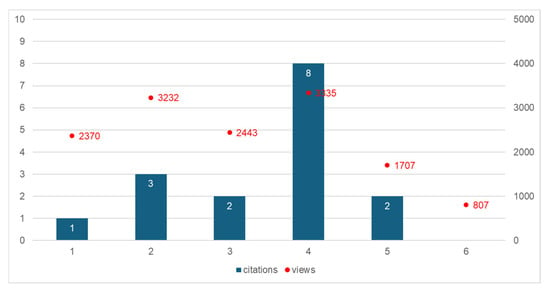

1.2. Bibliometrics and Impact

The six papers in this Special Issue were published over a period of 2 years, from March 2023 to September 2025. Each manuscript received rigorous peer review from at least two experts in the field. Based on MDPI’s article metrics, this Special Issue has received, up to now (1 December 2025), more than 13,000 total views. Overall, the published papers have already received 16 citations in the indexed literature. In detail, Rom et al. [11] achieved eight citations and 3335 online views, followed by the paper from Massaro et al. [9], with three citations and 3232 online views (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A graph showing the total number of citations and online views for each article as of 1 December 2025 (data source: MDPI).

2. From What Are We Moving? Why, How Fast, and How Much Are We Moving? Highlights from the Six Papers

2.1. Mud Spectral Characteristics from the Lusi Eruption, East Java, Indonesia, Using Satellite Hyperspectral Data

Amici et al. [8] exploit spaceborne imaging spectroscopy (EO-1 Hyperion, PRISMA) to retrieve the spectral signatures of minerals within the active Lusi mud eruption, an exceptionally challenging “wet and muddy” environment. By combining laboratory reflectance of sampled mud (Illite/Smectite) with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) spectral libraries and continuum-removed satellite spectra, the team identifies diagnostic Al-OH bands near ~2.2 µm and Fe electronic absorptions in the VNIR, quantifying differences in turbid vs. walkable surfaces and revealing artifacts calling for improved atmospheric corrections for PRISMA L2 products. This study demonstrates that new hyperspectral missions (PRISMA, EnMAP, EMIT) can map mineralogical variability relevant to hazard evolution and fluid pathways, with immediate implications for monitoring compositional change, sediment sources, and potential gas emissions.

2.2. Geomorphological Evolution of Volcanic Cliffs in Coastal Areas: The Case of Maronti Bay (Ischia Island)

Massaro et al. [9] integrate historical aerials, LiDAR (2009/2022), UAV photogrammetry (2023), and Virtual Outcrop Models to quantify 25 years of sea-cliff retreat and beach width oscillations on a volcanic coast subject to storms, landslides, and erosion. DEM-of-Difference analyses estimate ~29,700 m3 of land eroded (2009–2022) and ~2600 m3 was further eroded (2022–2023), while a November 2022 debris avalanche induced ~19 m of cliff recession locally and beach accretion at the toe. This study disentangles the roles of waves (SW storms) vs. mass wasting, relates transect-scale retreat rates to lithology, and translates time-series geomorphic change into mitigation needs for a densely inhabited coastal cliff line.

2.3. The Contribution of Digital Image Correlation for the Knowledge, Control, and Emergency Monitoring of Earth Flows

Mazza et al. [10] evaluate DIC for knowledge, control, and emergency monitoring of clay-rich earth flows in Campania. Using low-cost ground cameras (hourly images), UAV hillshade photogrammetry, and satellite imagery, DIC retrieves 2D displacement fields and high-frequency time series that correlate strongly with RTS/GNSS measurements (e.g., r ≈ 0.91), resolving velocities up to ~0.63 m/day during surge phases and ~5 cm within 1 h in single-pair analyses. The paper evaluates DIC as a versatile, cost-effective component of early warning architectures, while addressing geometric configuration, GSD, and vegetation issues, advocating hillshades and standardized workflows to maximize reliability.

2.4. Analysing the Large-Scale Debris Flow Event in July 2022 in Horlachtal, Austria Using Remote Sensing and Measurement Data

Rom et al. [11] present a rare catchment-wide quantification built on two ALS acquisitions bracketing a single convective thunderstorm (max intensity ~44 mm h−1). DEM differencing mapped 156 debris flows with a total deposition of ~199,000 m3; magnitudes were scaled with rainfall via a power-law, while spatial clustering reflected local convective forcing and landform controls (slope, curvature). This study exemplifies rigorous co-registration, uncertainty appraisal, and multi-data corroboration (gauges, INCA radar-blend rainfall), offering parameterizations useful for susceptibility/runout modeling and illuminating the limitations of gridded precipitation at an hourly resolution in alpine terrain.

2.5. The May 2023 Rainstorm-Induced Landslides in the Emilia-Romagna Region (Northern Italy): Considerations from UAV Investigations Under Emergency Conditions

Schilirò et al. [12] highlighted lessons from rapid deployments under civil protection coordination, combining field reconnaissance, UAV/PPK photogrammetry, and LiDAR to characterize thousands of shallow slides and slumps evolving into flows, with areal density driven by exceptional rainfall (return periods ≥ 500 years in some stations) and sensitive slope materials. The team documents anthropogenic factors (inadequate drainage, steep road cuts) that amplify triggers, emphasizes residual hazards (fractures, retrogression), and delivers decision-ready products (orthomosaics, DEMs) to support access restoration and hazard zoning—an operational template for post-event geoscience.

2.6. A Small Landslide as a Big Lesson: Drones and GIS for Monitoring and Teaching Slope Instability

Zaragozì et al. [13] show how multitemporal LiDAR (2009/2016) and UAV photogrammetry (2021/2023) can quantify a small rotational slide (~3500 m3 net loss 2016–2021; minor changes 2021–2023), then turn the case into a robust pedagogical resource for hazard education and local planning. The paper argues that small, frequent landslides, which are often overlooked, have disproportionate societal costs, as well as that reproducible UAV-LiDAR-GIS workflows strengthen site-specific diagnostics, community awareness, and practical training for students and practitioners alike.

3. Discussion: What These Studies Collectively Contribute

3.1. Multi-Sensor Integration

All six papers deal with data fusion. Hyperspectral analyses are anchored to lab-measured spectra and spectral libraries [8]; coastal morphodynamics emerge from orthophoto time series, LiDAR, and UAV DEMs [9]; DIC displacement maps are validated with RTS/GNSS [10]; debris-flow mapping marries ALS DoD with precipitation and discharge [11]; emergency campaigns combine UAV photogrammetry and LiDAR [12]; and educational case study research combines LiDAR and UAV products for change detection [13]. This approach improves reliability, quantifies uncertainty, and facilitates the transferability of results across sites and research teams.

3.2. From Imagery to Metrics

Quantitative geomorphic change is crucial: DEM of Difference (DoDs) estimates mobilized volumes and partition erosion/deposition [9,11], while DIC recovers pixel-level displacements and hour-scale velocities [10], and UAV/PPK workflows deliver centimeter-level DEMs for rapid emergency mapping and small landslide accounting [12]. These methods transform remote sensing “pictures” into process-aware variables (rates, magnitudes, kinematics) that feed forecasting, thresholds, and hazard models.

3.3. Operational Readiness and Protocols

Several contributions explicitly discuss acquisition geometry, co-registration, positional accuracy (RTK/PPK/GCPs), atmospheric corrections, and error propagation, essentials for reproducible products in civil protection contexts and engineering design. Mazza et al. [10] and Schilirò et al. [12] provide a clear framework for translating raw imagery into site-specific recommendations during crises. Rom et al. [11] and Massaro et al. [9] anchor their conclusions in the formal quantification of DoD uncertainties and transect-based statistical analyses. Amici et al. [8] detect where L2 reflectance needs corrections before mineral mapping.

3.4. Geoscience Education and Urban Resilience

Zaragozì et al. [13] highlight the pedagogical benefits of small landslide monitoring; their open workflow aligns with this Special Issue’s aim of strengthening prevention by democratizing technology and training. That same approach is used in Mazza et al. [10] and Schilirò et al. [12], which emphasize low-cost sensors, repeatable setups, and standardized forms/reporting for rapid knowledge transfer to agencies and the public.

4. Conclusions

The contributions in this Special Issue reveal that progress in remote sensing for hazard monitoring is not without obstacles. One recurring challenge lies in the reliability of input data: hyperspectral imagery, for instance, still suffers from atmospheric and radiometric artifacts that compromise mineralogical interpretation [8]. Similarly, precipitation datasets in mountainous regions often lack the spatial and temporal resolution needed to monitor convective storms, which are critical for understanding debris-flow triggers [11]. These limitations underline the need for integrated observation networks and improved correction algorithms.

Operational constraints also emerged during emergency deployments. Schilirò et al. [12] demonstrated how widespread slope failures can disrupt access, complicating rapid surveys. Here, UAV photogrammetry proved invaluable, but its effectiveness depends on standardized workflows and positional accuracy protocols. Digital Image Correlation introduced another layer of complexity: vegetation cover, camera geometry, and Ground Sampling Distance (GSD) can significantly affect displacement estimates, requiring careful planning and validation against ground-based sensors [10].

Coastal environments present additional challenges. Massaro et al. [9] illustrate how multi-hazard dynamics—arising from the interplay of marine erosion, landslides, and storm impacts—necessitate multitemporal and multi-sensor approaches. Finally, the under-representation of small, frequent landslides in hazard inventories remains a systemic issue. Zaragozì et al. [13] shows that these events, though modest in scale, accumulate substantial socio-economic impacts. Addressing these challenges demands not only technological refinement but also institutional commitment to systematic documentation and open data practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.; methodology, S.R. and M.B.; validation, S.R., M.B., C.C., F.M. and R.B.; writing-original draft preparation, M.B.; writing-review and editing, S.R. and C.C.; visualization, S.R. and M.B.; project administration, S.R., M.B. and C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The Guest Editors would like to acknowledge all the authors who contributed to this Special Issue and all the reviewers involved for their thoughtful comments and efforts toward improving the submitted manuscripts. Sincere gratitude is extended to the Editorial Board and Office of Geosciences for the invaluable assistance provided at all stages of the design, management, and publication of this Special Issue.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALS | Airborne Laser Scanning |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| DoD | DEM of Difference |

| DIC | Digital Image Correlation |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GCP | Ground Control Point |

| GSD | Ground Sampling Distance |

| INCA | Integrated Nowcasting through Comprehensive Analysis |

| InSAR | Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| PPK | Post-Processing Kinematic |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| RTS | Robotic Total Station |

| RTK | Real-Time Kinematic |

| SI | Special Issue |

| SfM | Structure from Motion |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

References

- Scaioni, M.; Longoni, L.; Melillo, V.; Papini, M. Remote Sensing for Landslide Investigations: An Overview of Recent Achievements and Perspectives. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 9600–9652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nex, F.; Remondino, F. UAV for 3D mapping applications: A review. Appl. Geomat. 2014, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberoi, I. Advancements in Multi-Spectral and Hyperspectral Remote Sensing: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions. J. Adv. Res. Geo Sci. Remote Sens. 2025, 12, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, M.B.; McGonigle, A.J.S.; Willmott, J.R. Hyperspectral Imaging in Environmental Monitoring: A Review of Recent Developments and Technological Advances in Compact Field Deployable Systems. Sensors 2019, 19, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Jain, S. Remote Sensing for Environment Assessment: Multispectral, Hyperspectral, and Thermal Imaging Applications. In Remote Sensing for Environmental Monitoring; Saritha, V., Pande, C.B., Singh, R., Shahid, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.; Wright, T.J. How satellite InSAR has grown from opportunistic science to routine monitoring over the last decade. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, K.E.; Wright, K.C.; Samsonov, S.V.; Ambrosia, V.G. Remote sensing and the disaster management cycle. In Advances in Geoscience and Remote Sensing; Jedlovec, G., Ed.; In-Tech: London, UK, 2009; pp. 317–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amici, S.; Buongiorno, M.F.; Sciarra, A.; Mazzini, A. Mud Spectral Characteristics from the Lusi Eruption, East Java, Indonesia Using Satellite Hyperspectral Data. Geosciences 2024, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, L.; Forte, G.; De Falco, M.; Santo, A. Geomorphological Evolution of Volcanic Cliffs in Coastal Areas: The Case of Maronti Bay (Ischia Island). Geosciences 2023, 13, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, D.; Romeo, S.; Cosentino, A.; Mazzanti, P.; Guadagno, F.M.; Revellino, P. The Contribution of Digital Image Correlation for the Knowledge, Control and Emergency Monitoring of Earth Flows. Geosciences 2023, 13, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rom, J.; Haas, F.; Hofmeister, F.; Fleischer, F.; Altmann, M.; Pfeiffer, M.; Heckmann, T.; Becht, M. Analysing the Large-Scale Debris Flow Event in July 2022 in Horlachtal, Austria Using Remote Sensing and Measurement Data. Geosciences 2023, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilirò, L.; Bosman, A.; Caielli, G.M.; Corazza, A.; Crema, S.; Di Salvo, C.; Gaudiosi, I.; Mancini, M.; Norini, G.; Peronace, E.; et al. The May 2023 Rainstorm-Induced Landslides in the Emilia-Romagna Region (Northern Italy): Considerations from UAV Investigations Under Emergency Conditions. Geosciences 2025, 15, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragozí, B.; Giménez-Font, P.; Cano-Aladid, J.; Marco-Molina, J.A. A Small Landslide as a Big Lesson: Drones and GIS for Monitoring and Teaching Slope Instability. Geosciences 2025, 15, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.