Late Pleistocene to Holocene Depositional Environments in Foredeep Basins: Coastal Plain Responses to Sea-Level and Tectonic Forcing—The Metaponto Area (Southern Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

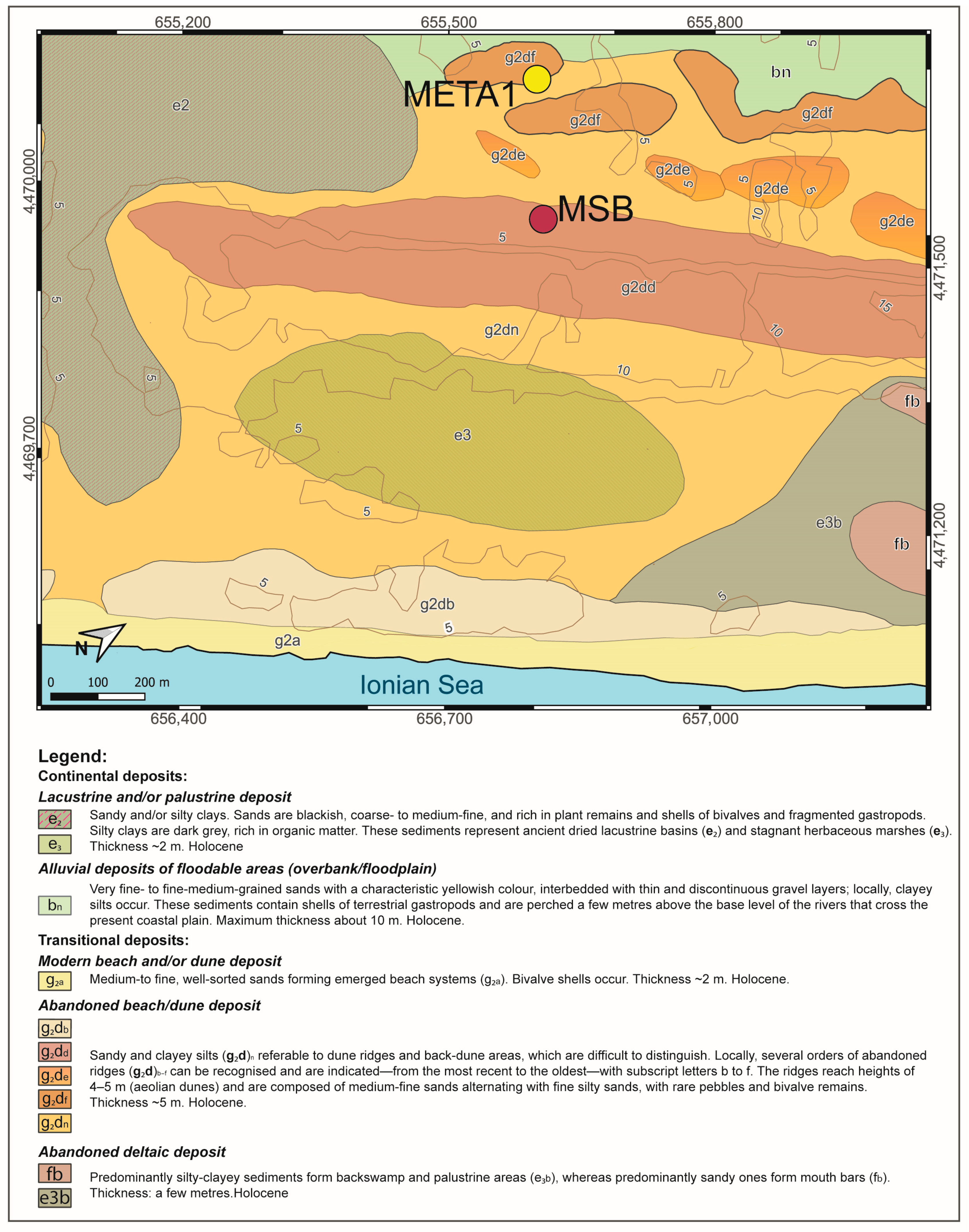

2. Geological Setting

The Bradanic Foredeep

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

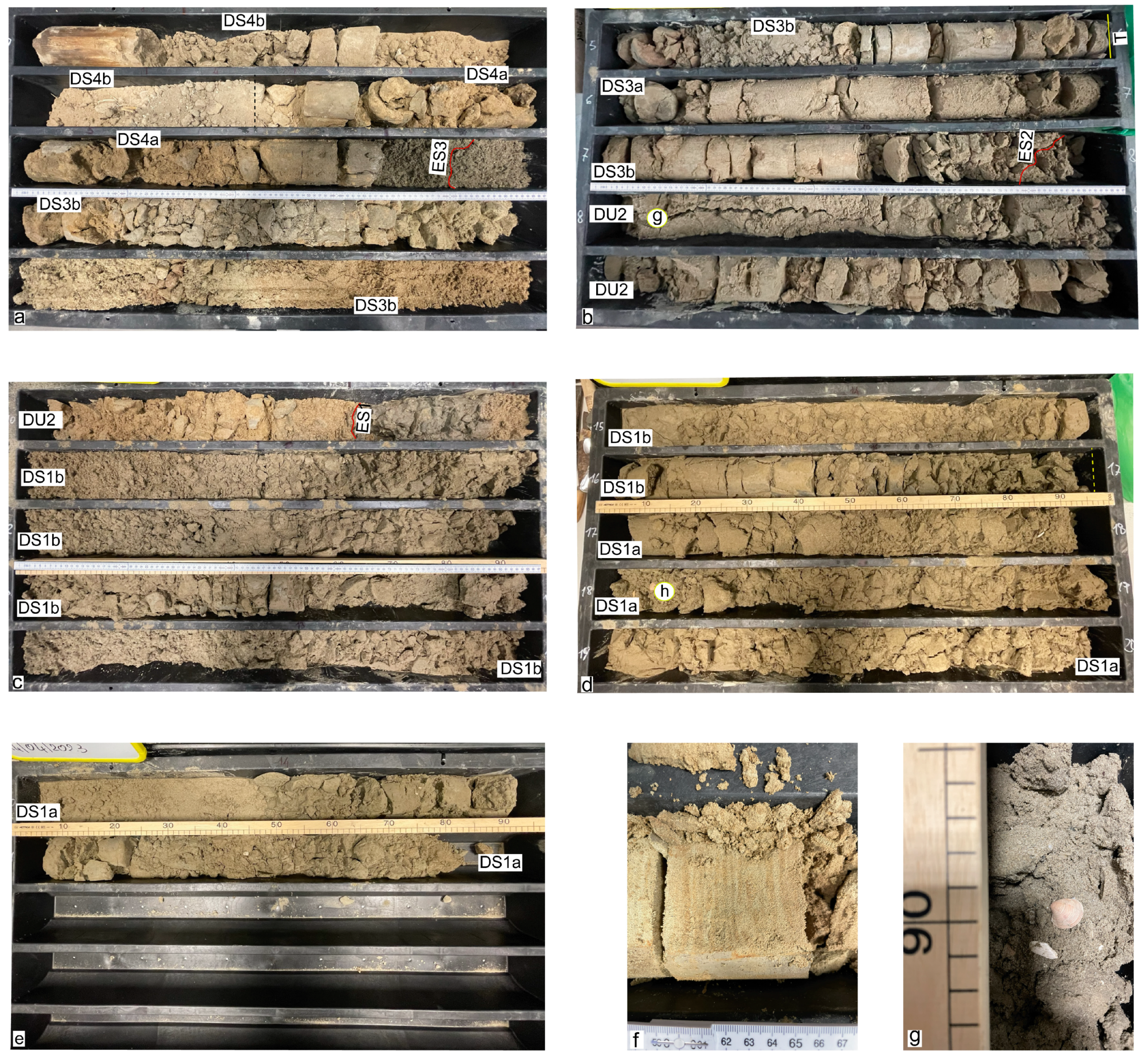

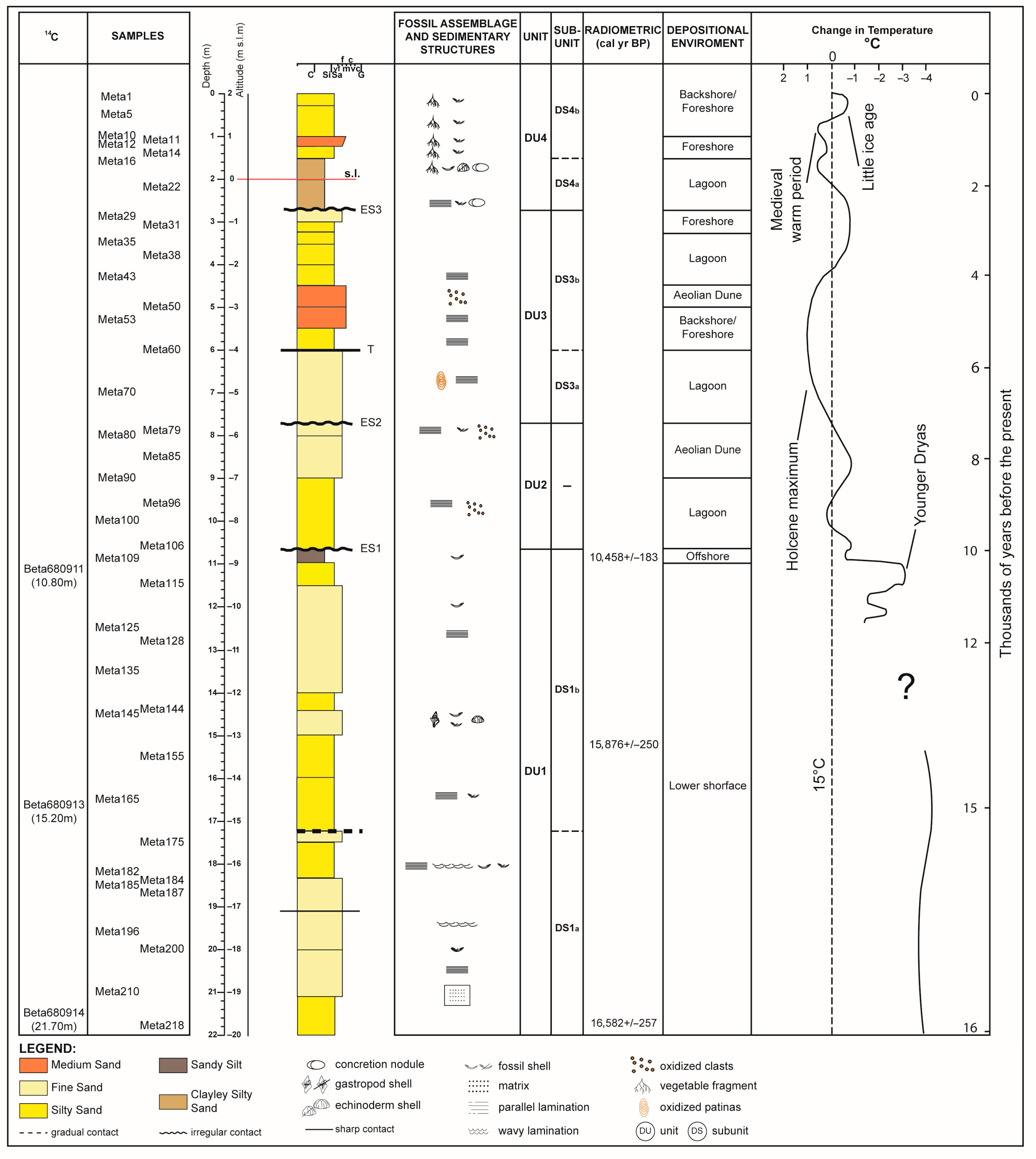

4.1. Stratigraphic Log with Radiometric Data

- -

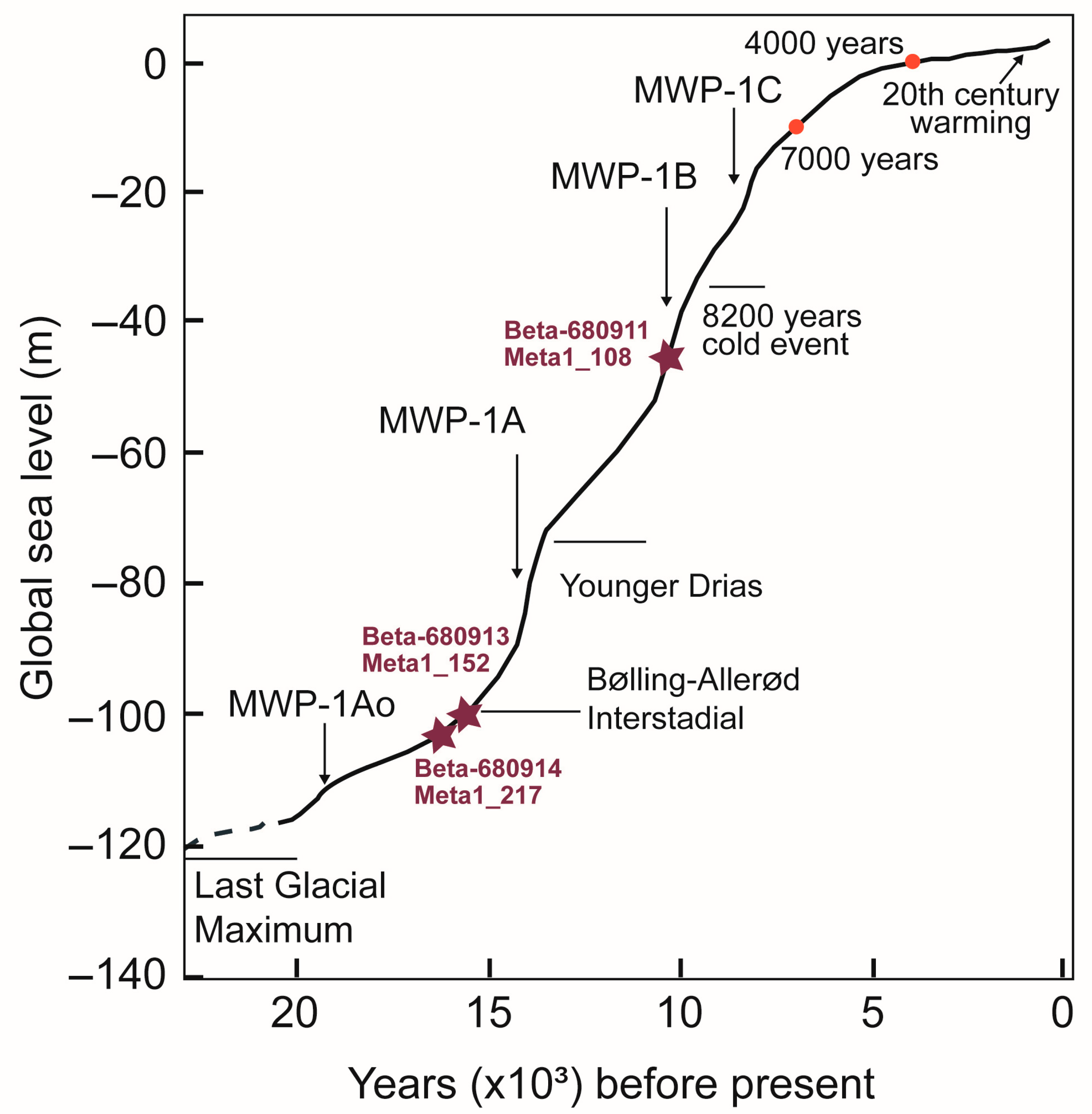

- DS1a (2200–1697 cm): The minimum recorded thickness is 480 cm, consisting of alternating sand, silt, and fine sand beds with parallel horizontal and cross-laminations. Complete and fragmented mollusc shells occur throughout. A radiocarbon age at 1217 cm yielded 16,582 ± 257 cal yr BP (Beta-680914_META1_217).

- -

- DS1b (1697–1062 cm): This sub-unit comprises a 615 cm succession of interbedded silty sand and fine sand with parallel horizontal laminations. Mollusc shells (bivalves and gastropods) are frequent; echinoderms are locally fragmented. At 1152 cm, the radiocarbon age is 15,876 ± 250 cal yr BP (Beta-680913_META1_152). A thin sandy silt layer (43 cm) containing bivalve shells overlies this bed and was dated to 10,458 ± 183 cal yr BP (Beta-680911_META1_108). The top of DS1b is marked by a sharp irregular contact (ES1).

- -

- DS3a (780–600 cm): This sub-unit comprises a 180 cm bed of fine sand with parallel horizontal lamination and oxidation patinas.

- -

- DS3b (600–280 cm): The basal portion comprises a 40 cm bed of silty sand with parallel horizontal lamination, overlain by two beds of medium sand with a total thickness of 100 cm. The lower medium-sand bed shows parallel horizontal lamination, whereas the upper bed contains oxidized clasts and horizontal lamination. Above, several silty sand beds (cumulative thickness 160 cm) occur, some with parallel horizontal laminations; the interval is capped by a 20 cm bed of fine sand. The base of DS3b is marked by a sharp, horizontal minor erosional surface (T).

- -

- DS4b (145–0 cm): This sub-unit demonstrates upward gradation from silty clay at the base to sandy silt. At a 100 cm depth, a 20 cm thick bed exhibits inverse grading from silt to medium sand.

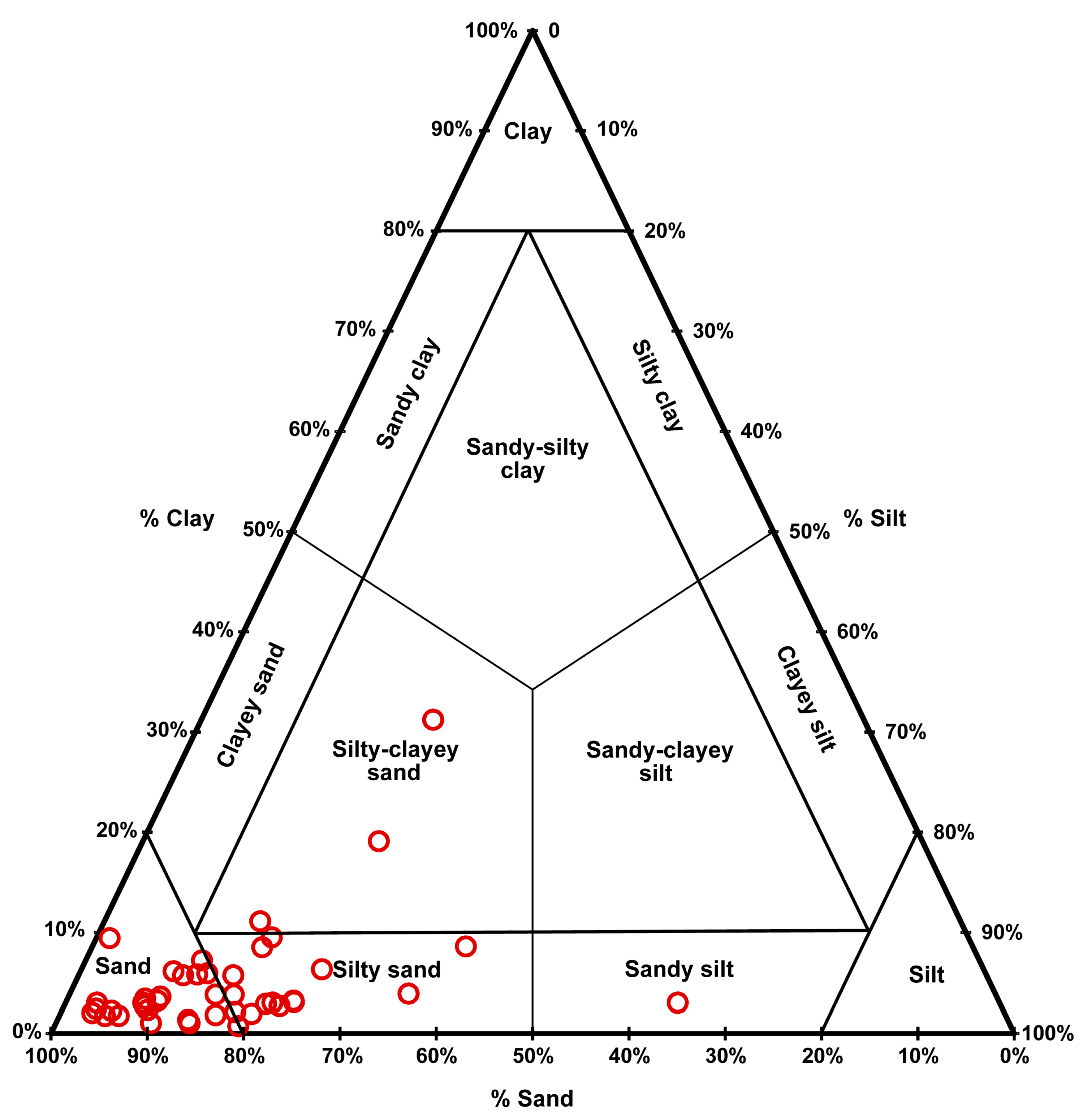

4.2. Statistical Parameters

4.3. Relationship Between Grain Size Parameters

4.4. Visher Model

4.5. Multivariate Analysis (PCA and k-Means Clustering)

4.6. Unit-by-Unit Synthesis

- DU1 (2200–1062 cm): Grain size statistics, long fine tails, and the dominance of transitional–offshore Visher families indicate offshore to lower shoreface conditions during the Late Glacial. PCA places these samples mainly in Cluster 1 (negative PC1), consistent with relatively mud-rich, suspension-influenced sand–silt mixtures. Radiocarbon ages between ~16.6 and 10.5 kyr BP bracket this offshore to lower-shoreface setting during the Last Glacial–interglacial transition.

- DU2 (1062–780 cm): The sharp, sand-dominated succession with improved sorting and reduced mud content marks a shift to higher-energy, tractional conditions, compatible with foreshore to upper-shoreface and aeolian dune facies. Grain size distributions mainly fall in Cluster 0 and are plotted at positive PC1 values, reflecting well-developed sand modes and attenuated fine tails.

- • DU3 (780–280 cm): Alternations of medium sand and silty sand, together with repeated lagoonal and transitional Visher families, indicate a stacked set of aeolian dune facies. PCA/cluster analysis shows an interbedding of Cluster 0 and Cluster 1 samples, reflecting the vertical alternation between traction-dominated sand bodies and finer, tail-rich intervals. This organization is consistent with repeated shifts between lagoonal infill and aeolian/beach reworking.

- • DU4 (280–0 cm): The upward transition from lagoonal silty clay and sandy silt (Cluster 1; negative PC1, long fine tails) to sandier deposits with local tractional beds (Cluster 0) records the final stages of lagoonal infill and subsequent emergence of the plain. Residual sand lenses preserve the imprint of shallow-marine or beach reworking predating stabilization, whereas roots, calcareous nodules, and other soil features reflect ongoing pedogenesis under present subaerial conditions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Global Sea Level Change

5.2. Paleoenvironmental Evolution of the Metaponto Area from ~16 kyr to the Present: Evidence from the Meta 1 Borehole

5.3. Stratigraphic Correlation Between Meta 1 and MSB Boreholes

5.4. Sea Level Change and Tectonic Interplay

- -

- At 17 kyr BP, transitional–offshore deposits are observed at −19 m b.s.l., while the global sea level stood at ~−100 m, implying that an ~81 m offset difference suggests an apparent uplift component on the order of ~4 mm/yr (consistent with [39]).

- -

- At ~16 kyr BP, transitional–offshore deposits are observed at −12 m b.s.l., corresponding to a global sea level of ~−105 m, implying that an offset of ~93 m likewise supports apparent uplift near ~4 mm/yr.

- -

- At ~10 kyr BP, offshore deposits are observed at −9 m b.s.l. and coincide with a global sea level of ~−40 m, implying that an offset of ~31 m difference suggests ongoing uplift near ~4 mm/yr.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

- A phase of net tectonic uplift likely persisted at least until ~7 kyr BP, with the relative sea level approaching a quasi-steady position around −5 m b.s.l. (as inferred from the DU2 aeolian-dune deposits at Meta 1).

- After ~7 kyr BP, the system appears to have entered a phase of modest net subsidence on the order of ~1 mm/yr, for which a compaction contribution is plausible but unquantified, as indicated by the relationship between the Meta 1 aeolian dune deposits in DS3b and the dated emerged-beach sands in the MSB core ~4 m below the present sea level [4].

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pescatore, T.; Pieri, P.; Sabato, L.; Senatore, M.R.; Gallicchio, S.; Boscaino, M.; Cilumbriello, A.; Quarantiello, R.; Capretto, G. Stratigrafia dei depositi pleistocenico-olocenici dell’area costiera di Metaponto compresa fra Marina di Ginosa ed il Torrente Cavone (Italia meridionale): Carta geologica in scala 1: 25.000. Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 2009, 22, 307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, R.; Bianca, M.; D’Onofrio, R. Ionian marine terraces of southern Italy: Insights for the quaternary geodynamic evolution of the area. Tectonics 2010, 29, TC4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.; Bavusi, M.; Di Leo, P.; Giammatteo, T.; Schiattarella, M. Geoarchaeology and geomorphology of the Metaponto area, Ionian coastal belt, Italy. J. Maps 2020, 16, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, G.; Aiello, G.; Barra, D.; Di Leo, P.; Gioia, D.; Amodio Antonio, M.; Parisi, R.; Schiattarella, M. Late Quaternary evolution of the Metaponto coastal plain, southern Italy, inferred from geomorphological and borehole data. Quat. Int. 2022, 638–639, 84–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.; Schiattarella, M.; Giano, S.I. Right-Angle Pattern of Minor Fluvial Networks from the Ionian Terraced Belt, Southern Italy: Passive Structural Control or Foreland Bending? Geosciences 2018, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, D.; Wagner, S.; Brückner, H.; Scarciglia, F.; Mastronuzzi, G.; Stahr, K. Soil development on marine terraces near Metaponto (Gulf of Taranto, southern Italy). Quat. Int. 2010, 222, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.; Corrado, G.; Amodio, A.M.; Schiattarella, M. Uplift rate calculation based on the comparison between marine terrace data and river profile analysis: A morphotectonic insight from the Ionian coastal belt of Basilicata, Italy. Geomorphology 2024, 447, 109030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropeano, M.; Cilumbriello, A.; Sabato, L.; Gallicchio, S.; Grippa, A.; Longhitano, S.G.; Bianca, M.; Gallipoli, M.R.; Mucciarelli, M.; Spilotro, G. Surface and subsurface of the Metaponto coastal plain (Gulf of Taranto-southern Italy): Present- day- vs LGM-landscape. Geomorphology 2013, 203, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leo, P.; Bavusi, M.; Corrado, G.; Danese, M.; Giammatteo, T.; Gioia, D.; Schiattarella, M. Ancient settlement dynamics and predictive archaeological models for the Metapontum coastal area in Basilicata, southern Italy: From geomorphological survey to spatial analysis. J. Coast. Conserv. 2018, 22, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, D.; De Pippo, T.; Ilardi, M.; Pennetta, M. Studio delle caratteristiche morfoevolutive quaternarie della piana del Garigliano. Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 1998, 11, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, G.; Barra, D.; De Pippo, T.; Donadio, C.; Miele, P.; Russo Ermolli, E. Morphological and paleoenvironmental evolution of the Vendicio coastal plain in the Holocene (Latium, Central Italy). Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 2007, 20, 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, G.; Amato, V.; Aucelli, P.P.C.; Barra, D.; Corrado, G.; Di Leo, P.; Di Lorenzo, H.; Jicha, B.; Pappone, G.; Parisi, R.; et al. Multiproxy study of cores from the Garigliano plain: An insight into the late quaternary coastal evolution of central-southern Italy. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 567, 110298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, G.; Barra, D.; Parisi, R.; Arienzo, M.; Donadio, C.; Ferrara, L.; Toscanesi, M.; Trifuoggi, M. Infralittoral Ostracoda and benthic foraminifera of the Gulf of Pozzuoli (Tyrrhenian sea, Italy). Aquat. Ecol. 2021, 55, 955–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, F.O.; Argenio, C.; Faranda, C.; Ferraro, L.; Gliozzi, E.; Magri, D.; Michelangeli, M.; Russo, B.; Siciliano, J.; Vallefuoco, M.; et al. Sedimentological and biostratigraphic reconstruction of the Early Pleistocene San Giuliano Lake section (Matera, Southern Italy). Quat. Int. 2025, 730, 109793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, D.; Romano, P.; Santo, A.; Campajola, L.; Roca, V.; Tuniz, C. The Versilian transgression in the Volturno River Plain (Campania, southern Italy): Palaeoenvironmental history and chronological data. Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 1996, 9, 445–458. [Google Scholar]

- Barra, D.; Calderoni, G.; Cinque, A.; De Vita, P.; Rosskopf, C.M.; Russo Ermolli, E. New data on the evolution of the Sele river coastal plain (southern Italy) during the Holocene. Alp. Mediterr. Quat. 1998, 11, 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Cilumbriello, A.; Sabato, L.; Tropeano, M.; Gallicchio, S.; Grippa, A.; Maiorano, P.; Mateu-Vicens, G.; Rossi, C.A.; Spilotro, G.; Calcagnile, L.; et al. Sedimentology, stratigraphic architecture and preliminary hydrostratigraphy of the Metaponto coastal-plain subsurface (Southern Italy). Mem. Descr. Carta Geol. D’italia 2010, 90, 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Marturano, A.; Aiello, G.; Barra, D. Evidence for late Pleistocene uplift at the Somma-Vesuvius apron near Pompeii. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 2011, 202, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, R.L.; Ward, W.C. A Study in the Significance of Grain-Size Parameters. J. Sediment. Petrol. 1957, 27, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visher, G.S. Grain-Size Distribution and Depositional Processes. J. Sediment. Petrol. 1969, 39, 1074–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Ferranti, L.; Antonioli, F.; Scicchitano, G.; Spampinato, C.R. Uplifted Late Holocene shorelines along the coasts of the Calabrian Arc: Geodynamic and seismotectonic implications. Ital. J. Geosci. 2017, 136, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, E.; Mazzella, M.E.; Ferranti, L.; Randisi, A.; Napolitano, E.; Rittner, S.; Radtke, U. Raised coastal terraces along the Ionian Sea coast of northern Calabria, Italy, suggest space and time variability of tectonic uplift rates. Quat. Int. 2009, 206, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, E.; Ferranti, L.; Burrato, P.; Mazzella, M.E.; Monaco, C. Deformed Pleistocene marine terraces along the Ionian Sea margin of southern Italy: Unveiling blind fault-related folds contribution to coastal uplift. Tectonics 2013, 32, 737–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardino, G.; Sabatier, F.; Scicchitano, G.; Piscitelli, A.; Milella, M.; Vecchio, A.; Anzidei, M.; Mastronuzzi, G. Sea-level rise and shoreline changes along an open sandy coast: Case study of Gulf of Taranto, Italy. Water 2020, 12, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, V.; Caldara, M.; Torres, T.; Ortiz, J.E.; Sánchez-Palencia, Y. The Role of Beach Ridges, Spits, or Barriers in Understanding Marine Terraces Processes on Loose or Semiconsolidated Substrates: Insights from the Givoni of the Gulf of Taranto (Southern Italy). Geol. J. 2019, 55, 2951–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, V.; Scardino, G.; Meschis, M.; Ortiz, J.E.; Sánchez-Palencia, Y.; Caldara, M. Refining the Middle-Late Pleistocene Chronology of Marine Terraces and Uplift History in a Sector of the Apulian Foreland (Southern Italy) by Applying a Synchronous Correlation Technique and Amino Acid Racemization to Patella spp. and Thetystrombus Latus. Ital. J. Geosci. 2021, 140, 438–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescatore, T.; Senatore, M.R. A Comparison between a Present-Day (Taranto Gulf) and a Miocene (Irpinian Basin) Foredeep of the Southern Apennines (Italy); John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986; Volume 8, pp. 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, M.R.; Normark, W.R.; Pescatore, T.; Rossi, S. Structural framework of the Gulf of Taranto (Ionian Sea). Mem. Della Soc. A Geol. D’italia 1988, 41, 533–539. [Google Scholar]

- Chilovi, C.; De Feyter, A.J.; Pompucci, A. Wrench zone reactivation in the Adriatic block: The example of the Mattinata fault system (SE Italy). Boll. Soc. Geol. It 2000, 119, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Morsilli, M.; De Cosmo, P.D.; Bosellini, A.; Luciani, V. L’annegamento santoniano della Piattaforma Apula nell’area di Apricena (Gargano, Puglia): Nuovi dati per la paleogeografia del Cretaceo superiore. In Fascicolo Degli Abstract Della IX Riunione del Gruppo di Sedimentologia del CNR (Pescara, Italy, 21–22 October 2002); Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR): Rome, Italy, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Spalluto, L. La Piattaforma Apula nel Gargano Centro-Occidentale: Organizzazione Stratigrafica ed Assetto Della Successione Mesozoica di Piattaforma Interna. PhD Thesis, Università degli Studi di Bari, Bari, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Spalluto, L. Facies evolution and sequence chronostratigraphy of a “mid”-Cretaceous shallow-water carbonate succession of the Apulia Carbonate platform from the northern Murge area (Apulia, southern Italy). Facies 2011, 58, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santantonio, M.; Scrocca, D.; Lipparini, L. The Ombrina-Rospo Plateau (Apulian platform): Evolution of a carbonate platform and its margins during the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2013, 42, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneva, I.; Tondi, E.; Agosta, F.; Rustichelli, A.; Spina, V.; Bitonte, R.; Di Cuia, R. Structural properties of fractured and faulted Cretaceous platform carbonates, Murge Plateau (southern Italy). Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2014, 57, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, F.; Manniello, C.; Cavalcante, F.; Belviso, C.; Prosser, G. Late cretaceous transtensional faulting of the Apulian platform, Italy. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2021, 127, 104889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, S.; D’Errico, M.; Aldega, L.; Corrado, S.; Invernizzi, C.; Shiner, P.; Zattin, M. Tectonic burial and “young” (<10 Ma) exhumation in the southern Apennines fold-and-thrust belt (Italy). Geology 2008, 36, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.; Ciarcia, S. Tectono-stratigraphic and kinematic evolution of the southern Apennines/Calabria–Peloritani Terrane system (Italy). Tectonophysics 2013, 583, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.; Prinzi, E.P.; Tramparulo, F.D.A.; De Paola, C.; Di Maio, R.; Piegari, E.; Sabbatino, M.; Natale, J.; Notaro, P.; Ciarcia, S. Late Miocene-early Pliocene out-of-sequence thrusting in the southern Apennines (Italy). Geosciences 2020, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarcia, S.; Vitale, S. Orogenic evolution of the northern Calabria–southern Apennines system in the framework of the Alpine chains in the central-western Mediterranean area. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2025, 137, 1143–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiattarella, M.; Leo, P.D.; Beneduce, P.; Giano, S.I.; Martino, C. Tectonically Driven Exhumation of a Young Orogen: An Example from the Southern Apennines, Italy; Willett, S.D., Hovius, N., Brandon, M.T., Fisher, D., Eds.; Geol S Am S. Special Paper of the Geological Society of America; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006; Volume 398, pp. 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondi, E.; Piccardi, L.; Cacon, S.; Kontny, B.; Cello, G. Structural and time constraints for dextral shear along the seismogenic Mattinata fault (Gargano, southern Italy). J. Geodyn. 2005, 40, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doglioni, C.; Mongelli, F.; Pieri, P. The Puglia uplift (SE Italy): An anomaly in the foreland of the Apenninic subduction due to buckling of a thick continental lithosphere. Tectonics 1994, 13, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doglioni, C.; Tropeano, M.; Mongelli, F.; Pieri, P. Middle-late Pleistocene uplift of Puglia: An anomaly in the Apenninic foreland. Mem. Soc. Geol. It 1996, 51, 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Patacca, E.; Scandone, P. The Plio-Pleistocene thrust belt-foredeep system in the southern Apennines and Sicily (Italy). Geol. Italy 2004, 32, 93–129. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbatino, M.; Tavani, S.; Vitale, S.; Ogata, K.; Corradetti, A.; Consorti, L.; Arienzo, I.; Cipriani, A.; Parente, M. Forebulge migration in the foreland basin system of the central-southern Apennine fold-thrust belt (Italy): New high-resolution Sr-isotope dating constraints. Basin Res. 2021, 33, 2817–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doglioni, C.; Harabaglia, P.; Martinelli, G.; Mongelli, F.; Zito, G. A geodynamic model of the Southern Apennines accretionary prism. Terra Nova 1996, 8, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaway, R.; Bridgland, D. Late Cenozoic uplift of southern Italy deduced from fluvial and marine sediments: Coupling between surface processes and lower crustal flow. Quat. Int. 2007, 175, 86–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzaroli, A.; Perno, U.; Radina, B. Note Illustrative Della Carta Geologica d’Italia Alla Scala 1:100,000. Foglio 188: Gravina di Puglia; Servizio Geologico d’Italia: Roma, Italy, 1968; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Di Gennaro, M.; Moresi, M.; Nuovo, G. Argille subappennine di Irsina (Mt) e Monternesola (Ta): Analisi comparativa di dati geochimici e mineralogici. Geol. Appl. Idrogeol. 1977, 12, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete, M. Aspetti evolutivi dei versanti in argille sub-appennine dell’avanfossa bradanica. Edagricola Bologna 1994, 4, 320–330. [Google Scholar]

- Ciaranfi, N.; Marino, M.; Sabato, L.; D’Alessandro, A.; De Rosa, R. Studio geologico stratigrafico di una successione infra e mesopleistocenica nella parte sudoccidentale della Fossa Bradanica (Montalbano Ionico, Basilicata). Boll. Soc. Geol. It. 1996, 115, 379–391. [Google Scholar]

- Ciaranfi, N.; Lirer, F.; Lirer, L.; Lourens, L.J.; Maiorano, P.; Marino, M.; Petrosino, P.; Sprovieri, M.; Stefanelli, S.; Brilli, M.; et al. Integrated stratigraphy and astronomical tuning of the Lower- Middle Pleistocene Montalbano Jonico land section (southern Italy). Quat. Int. 2010, 210, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropeano, M.; Sabato, L.; Pieri, P. Filling and cannibalization of a foredeep: The Bradanic Trough, southern Italy. Geol. Soc. Lond. Sp. Publ. 2002, 191, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallicchio, S.; Colacicco, R.; Capolongo, D.; Girone, A.; Maiorano, P.; Marino, M.; Ciaranfi, N. Geological features of the special nature reserve of Montalbano Jonico Badlands (Basilicata, Southern Italy). J. Maps 2023, 19, 2179435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivenga, M.; Coltorti, M.; Prosser, G.; Tavarnelli, E. Marine terraces and extensional faulting in the Taranto Gulf, Bradanic Trough, Southern Italy. Studi Geol. Camerti Nuova Ser. 2004, 123, 391–404. [Google Scholar]

- Cilumbriello, A.; Sabato, L.; Tropeano, M. Problemi di cartografia geologica relativa ai depositi quaternari di chiusura del ciclo della Fossa bradanica: L’area chiave di Banzi e Genzano di Lucania (Basilicata). Mem. Soc. Geol. It 2008, 77, 119–142. [Google Scholar]

- Gallicchio, S.; Senatore, M.R.; Sabato, L.; Boscaino, M.; Capretto, G.; Cilumbriello, A.; Quarantiello, R. Carta Geologica Dell’area Costiera di Metaponto fra Marina di Ginosa ed il Torrente Cavone (scale 1:25,000). Il Quat. (Ital. J. Quat. Sci.) 2025, 22. Available online: https://www.aiqua.it/images/Tavole/Gallicchio%20et%20al%2022_2%20rid.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Simms, A.R.; Rouby, H.; Lambeck, H. Marine terraces and rates of vertical tectonic motion: The importance of glacio-isostatic adjustment along the Pacific coast of central North America. GSA Bull. 2016, 128, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckner, H. Marine Terrassen in Süditalien Eine quartärmorphologische Studie über dasKüstentiefland von Metapont. Düsserdolfer Geogr. Schriften 1980, 14, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Finetti, I. The CROP profiles across the Mediterranean Sea (CROP mare I and II). Mem. Descr. Carta Geol. D’It. 2003, 12, 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Patacca, E.; Scandone, P. Late thrust propagation and sedimentary response in the thrust-belt—Foredeep system of the Southern Apennines (Pliocene-Pleistocene). In Anatomy of an Orogen: The Apennines and Adjacent Mediterranean Basins; Vai, G.B., Martini, I.P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2001; pp. 401–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, D.L.; Schubert, G. Applications of Continuum Physics to Geological Problems; University of Michigan; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, D.C.; Kidd, W.S.F. Flexural extension of the upper continental crust in collisional foredeeps. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1991, 103, 1416–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Doglioni, C. Geological remarks on the relationships between extension and convergent geodynamic settings. Tectonophysics 1995, 252, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhi, L.; Ciftci, N.B.; Borel, G.D. Impact of lithospheric flexure on the evolution of shallow faults in the Timor foreland system. Mar. Geol. 2011, 284, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavani, S.; Vignaroli, G.; Parente, M. Transverse versus longitudinal extension in the foredeep-peripheral bulge system: Role of Cretaceous structural inheritances during early Miocene extensional faulting in inner central Apennines belt. Tectonics 2015, 34, 1412–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, A.; Chiocci, F.L.; Senatore, M.R. Morphometric measures to assess the maturity of the submerged drainage basins: The case of the Taranto Canyon upper reach. In Proceedings of the IMEKO International Conference on Metrology for the Sea (MetroSea 2017), Naples, Italy, 11–13, October 2017; pp. 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Senatore, M.R.; Meo, A.; Budillon, F. Measurements in marine geology: Anexample in the Gulf of Taranto (northern Ionian Sea). In Measurement for the Sea: Supporting the Marine Environment and the Blue Economy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 271–289. [Google Scholar]

- Meo, A.; Senatore, M.R. Morphological and seismostratigraphic evidence of Quaternary mass transport deposits in the North Ionian Sea: The Taranto landslide complex (TLC). Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1168373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceramicola, S.; Senatore, M.R.; Cova, A.; Meo, A.; Forlin, E.; Critelli, S.; Markezic, N.; Zecchin, M.; Civile, D.; Bosman, A.; et al. Geohazard features of the Gulf of Taranto. J. Maps 2024, 20, 2431073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, M.R. Caratteri sedimentari e tettonici di un bacino di avanfossa. Il Golfo di Taranto. Mem. Soc. Geol. It. 1987, 38, 177–204. [Google Scholar]

- Di Bucci, D.; Burrato, P.; Vannoli, P.; Valensise, G. Tectonic evidence for the ongoing Africa-Eurasia convergence in central Mediterranean foreland areas: A journey among long-lived shear zones, large earthquakes, and elusive fault motions. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, B12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropeano, M.; Sabato, L. Response of Plio-Pleistocene Mixed Bioclastic-Lithoclastic Temperate-Water Carbonate Systems to Forced Regressions: The Calcarenite di Gravina Formation, Puglia, SE Italy. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2000, 172, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boenzi, F.; Radina, B.; Ricchetti, G.; Valduga, A. Note Illustrative della Carta Geologica d’Italia, Foglio 201 “Matera”; Servizio Geologico d’Italia: Roma, Italy, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Lisco, S.; Corselli, C.; De Giosa, F.; Mastronuzzi, G.; Moretti, M.; Siniscalchi, A.; Marchese, F.; Bracchi, V.; Tessarolo, C.; Tursi, A. Geology of Mar Piccolo, Taranto (southern Italy): The physical basis for remediation of a polluted marine area. J. Maps 2016, 12, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, A.; Mauro, A.; Senatore, M.R. Geological map of the San Giuliano Lake (Southern Italy): New stratigraphic and sedimentological data. Ital. J. Geosci. 2024, 143, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaway, R. Quaternary uplift of southern Italy. J. Geophys. Res. 1993, 87, 21741–21772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferranti, L.; Oldow, J.S. Latest Miocene to Quaternary horizontal and vertical displacement rates during simultaneous contraction and extension in the Southern Apennines orogen, Italy. Terra Nova 2005, 17, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainone, M.; Nanni, T.; Ori, G.G.; Ricci Lucchi, F. A prograding gravel beach in Pleistocene fan-delta deposits South of Ancona, Italy. In International Association of Sedimentologists―European Regional Meeting, 2nd ed.; European Meeting: Bologna/Ancona, Italy, 1981; pp. 155–156. [Google Scholar]

- Massari, F.; Parea, G.C. Progradational gravel beach sequences in a moderate to high energy microtidal marine environment. Sedimentology 1988, 35, 881–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M. Techniques in Sedimentology; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1988; p. 394. [Google Scholar]

- Munsell, A. Soil Colour Charts; Macbeth Division of Eolianllmorgen Corporation: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1975; p. 21218. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.V. Lamina, laminaset, bed and bedset. Sedimentology 1967, 8, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, R.L. Petrology of Sedimentary Rocks; Hemphill’s: Austin, TX, USA, 1968; Volume 70, p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D.W.; McConchie, D. Analytical Sedimentology; Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA.; London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, M. Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy|S. Boggs (1995); Englewood Cliffs; Hardcover, XVII; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1995; ISBN 0-02-311792-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsline, D.S. 1971, Procedures in Sedimentary Petrology; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 1960; p. 653. [Google Scholar]

- Blott, S.J.; Pye, K. Particle size scales and classification of sediment types based on particle size distributions: Review and recommended procedures. Sedimentology 2012, 59, 2071–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönwiese, C.D. Globale Klimaänderungen aufgrund des anthropogenen Treibhauseffektes und konkurrierender Einflüsse. In CO2—Eine Herausforderung für die Menschheit; Gehr, P., Kost, C., Stephan, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornitz, V. The Great Ice Meltdown and Rising Seas: Lessons for Tomorrow. NASA News 2012, Public Domain. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42012722 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Aiello, G. Regional Geological Data on the Volturno Basin Filling and Its Relationship to the Massico Structure (Southern Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budillon, F.; Senatore, M.R.; Insinga, D.D.; Iorio, M.; Lubritto, C.; Roca, M.; Rumolo, P. Late Holocene sedimentary changes in shallow water settings: The case of the Sele river offshore in the Salerno Gulf (south-eastern Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). Rend. Lincei 2012, 23, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Barra, D.; Calderoni, G.; Cipriani, M.; De La Genire, J.; Fiorillo, L.; Greco, G.; Mariotti Lippi, M.; Mori Secci, M.; Pescatore, T.; Russo, B.; et al. Depositional history and paleogeographic reconstruction on Sele coastal plain during Magna Grecia Settlement of Hera Argiva (Southern Italy). Geol. Romana 1999, 35, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fanget, A.S.; Bassetti, M.A.; Fontanier, C.; Tudryn, A.; Berné, S. Sedimentary archives of climate and sea-level changes during the Holocene in the Rhône prodelta (NW Mediterranean Sea). Clim. Past 2016, 12, 2161–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynal, O.; Bouchette, F.; Certain, R.; Sabatier, P.; Lofi, J.; Seranne, M.; Dezileau, L.; Briqueu, L.; Ferrer, P.; Courp, T. Holocene evolution of a Languedocian lagoonal environment controlled by inherited coastal morphology (northern Gulf of Lions, France). Bull. De La Société Géologique De Fr. 2010, 181, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cearreta, A.; Benito, X.; Ibáñez, C.; Trobajo, R.; Giosan, L. Holocene palaeoenvironmental evolution of the Ebro Delta (Western Mediterranean Sea): Evidence for an early construction based on the benthic foraminiferal record. Holocene 2016, 26, 1438–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaibi, C.; Kamoun, F.; Viehberg, F.; Carbonel, P.; Jedoui, Y.; Abida, H.; Fontugny, M. Impact of relative sea level and extreme climate events on the Southern Skhira coastline (Gulf of Gabes, Tunisia) during Holocene times: Ostracodes and foraminifera associations’ response. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2016, 118, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Visher Environment | Key Curve Criteria | Indicative Stats (φ) | Gorsline (1960) Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta1_218 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_210 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_200 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_196 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_187 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_185 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_184 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_182 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_175 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_165 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_155 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_135 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_128 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_125 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_115 | Transitional → Offshore | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_109 | Offshore fine | Prominent fine tail; subdued coarse shoulder | σᵢ~0.9–1.4 φ; Skᵢ ≥ 0; K_G meso → lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_106 | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) | Long fine tail; concave-up sand–silt transition | σᵢ ≥ 1.4–1.8 φ; Skᵢ > 0; K_G lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_100 | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) | Long fine tail; concave-up sand–silt transition | σᵢ ≥ 1.4–1.8 φ; Skᵢ > 0; K_G lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_96 | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) | Long fine tail; concave-up sand–silt transition | σᵢ ≥ 1.4–1.8 φ; Skᵢ > 0; K_G lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_90 | Lagoon/transitional | Long fine tail; concave-up sand–silt transition | σᵢ ≥ 1.4–1.8 φ; Skᵢ > 0; K_G lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_85 | Aeolian dune/beach (traction-dominated) | Sharp sand-mode; attenuated fine tail | σᵢ ≈ 0.7–1.0 φ; Skᵢ~0 to +; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_80 | Aeolian dune/beach (traction-dominated) | Sharp sand-mode; attenuated fine tail | σᵢ ≈ 0.7–1.0 φ; Skᵢ~0 to +; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_79 | Aeolian dune/beach (traction-dominated) | Sharp sand-mode; attenuated fine tail | σᵢ ≈ 0.7–1.0 φ; Skᵢ~0 to +; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_50 | Aeolian dune/beach (traction-dominated) | Sharp sand-mode; attenuated fine tail | σᵢ ≈ 0.7–1.0 φ; Skᵢ~0 to +; K_G meso → lepto | Sand |

| Meta1_43 | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) | Long fine tail; concave-up sand–silt transition | σᵢ ≥ 1.4–1.8 φ; Skᵢ > 0; K_G lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_38 | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) | Long fine tail; concave-up sand–silt transition | σᵢ ≥ 1.4–1.8 φ; Skᵢ > 0; K_G lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_35 | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) | Long fine tail; concave-up sand–silt transition | σᵢ ≥ 1.4–1.8 φ; Skᵢ > 0; K_G lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_31 | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) | Long fine tail; concave-up sand–silt transition | σᵢ ≥ 1.4–1.8 φ; Skᵢ > 0; K_G lepto | Sandy Silt |

| Meta1_22 | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) | Long fine tail; concave-up sand–silt transition | σᵢ ≥ 1.4–1.8 φ; Skᵢ > 0; K_G lepto | Sandy Silty Clay |

| Sample | PC1 | PC2 | Cluster | PCA Based Facies | Visher Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta1_218 | −2.97449 | 0.315614 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_210 | −2.82921 | −0.29432 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_200 | −3.13065 | −0.07919 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_196 | −2.25531 | −0.1285 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_187 | −2.33456 | −0.65492 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_185 | −2.59284 | 0.639002 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_184 | −3.14172 | −0.08728 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_182 | −2.92571 | 1.265715 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_175 | −2.78347 | 1.893667 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_165 | −2.91909 | −0.55201 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_155 | −2.55669 | 0.054152 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_145 | −2.44086 | 0.0276438 | 1 | MF | - |

| Meta1_144 | 2.240749 | −2.26476 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_135 | −2.40521 | −1.00642 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_128 | −2.8837 | −0.23341 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_125 | −2.5722 | −0.08284 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_115 | −0.3518 | 0.567688 | 1 | MF | Transitional → Offshore |

| Meta1_109 | −1.64989 | 4.584531 | 1 | MF | Offshore fine |

| Meta1_106 | 1.941333 | 1.918864 | 0 | SF | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) |

| Meta1_100 | 2.206886 | 0.710402 | 0 | SF | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) |

| Meta1_96 | −0.92843) | −1.64451 | 1 | MF | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) |

| Meta1_90 | −0.41509 | −0.41678 | 1 | MF | Lagoon/transitional |

| Meta1_85 | 3.676703 | 4.280587 | 0 | SF | Aeolian dune/beach (traction-dominated) |

| Meta1_80 | 2.578333 | 2.449743 | 0 | SF | Aeolian dune/beach (traction-dominated) |

| Meta1_79 | 2.354783 | 0.507488 | 0 | SF | Aeolian dune/beach (traction-dominated) |

| Meta1_70 | 1.349685 | 0.416738 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_60 | 0.510658 | −1.2877 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_53 | 2.479244 | −0.00492 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_50 | 3.50737 | 2.281984 | 0 | SF | Aeolian dune/beach (traction-dominated) |

| Meta1_43 | 1.1085 | −0.31047 | 0 | SF | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) |

| Meta1_38 | 1.023073 | −0.44702 | 0 | SF | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) |

| Meta1_35 | 1.489476) | −1.71804 | 0 | SF | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) |

| Meta1_31 | 1.075504 | −2.3511 | 0 | SF | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) |

| Meta1_29 | 1.645979 | −0.74583 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_22 | 1.207115 | −1.24026 | 0 | SF | Lagoon (fine-tail-dominated) |

| Meta1_16 | 1.092128 | 1.3789 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_14 | 2.240749 | −2.26476 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_12 | 1.956824 | −0.52682 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_11 | 2.677513 | −0.24283 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_10 | 2.77089 | −0.14409 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_5 | 1.047294 | −0.22105 | 0 | SF | - |

| Meta1_1 | 1.910121 | −1.83389 | 0 | SF | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meo, A.; Senatore, M.R. Late Pleistocene to Holocene Depositional Environments in Foredeep Basins: Coastal Plain Responses to Sea-Level and Tectonic Forcing—The Metaponto Area (Southern Italy). Geosciences 2026, 16, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010005

Meo A, Senatore MR. Late Pleistocene to Holocene Depositional Environments in Foredeep Basins: Coastal Plain Responses to Sea-Level and Tectonic Forcing—The Metaponto Area (Southern Italy). Geosciences. 2026; 16(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeo, Agostino, and Maria Rosaria Senatore. 2026. "Late Pleistocene to Holocene Depositional Environments in Foredeep Basins: Coastal Plain Responses to Sea-Level and Tectonic Forcing—The Metaponto Area (Southern Italy)" Geosciences 16, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010005

APA StyleMeo, A., & Senatore, M. R. (2026). Late Pleistocene to Holocene Depositional Environments in Foredeep Basins: Coastal Plain Responses to Sea-Level and Tectonic Forcing—The Metaponto Area (Southern Italy). Geosciences, 16(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010005