Abstract

Environmental problems may develop in groundwater basins when water levels change due to long-term wetter or drier climate or land development. A term related to water-level elevation is flow capacity, which develops in aquifers when the water table is at or very close to land surface. Non-capacity develops in systems where the water table is too deep for capillary water to reach the land surface. Flow capacity is the maximum amount of water that an aquifer can transmit. Sufficient moisture is not available for flow capacity to be established in most aquifers in arid zones and these aquifers are at non-capacity, but many aquifers in today’s deserts were at flow capacity when paleoclimates were cooler and moister during the late Pleistocene. Climate change and anthropogenic activities can cause aquifers to move toward flow capacity but in the last 15,000 years, almost always toward non-capacity. This paper reviews environmental and geotechnical problems associated with the transition of groundwater basins from flow capacity to non-capacity, and vice versa. Five relevant topics are discussed and evaluated: (1) The effects of flow capacity and non-capacity on groundwater basins targeted for waste repositories; (2) The salt contamination of groundwater where flow capacity was present in the Late Pleistocene and is no longer present; (3) Trace element enrichment in salt crusts in playa sediments and environmental risks to groundwater when the flow systems transition from flow capacity to non-capacity; (4) The development and retention of environmental tracers in arid groundwater flow systems at flow capacity that cannot be explained under conditions of non-capacity; and (5) The relationship of flow capacity to fossil hydraulic gradients and non-equilibrium conditions where there is little groundwater extraction. A case example is provided with each of these topics to demonstrate relevance and to provide an understanding of topics as they relate to land management.

1. Introduction

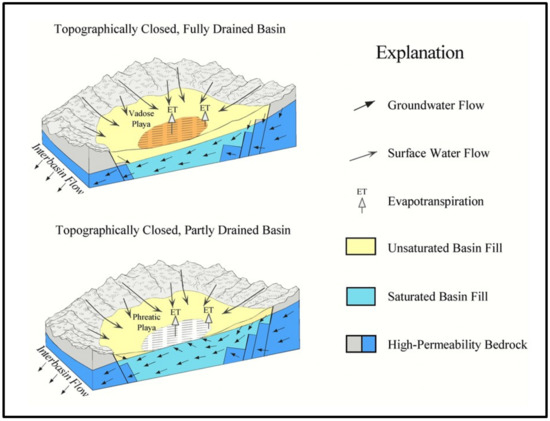

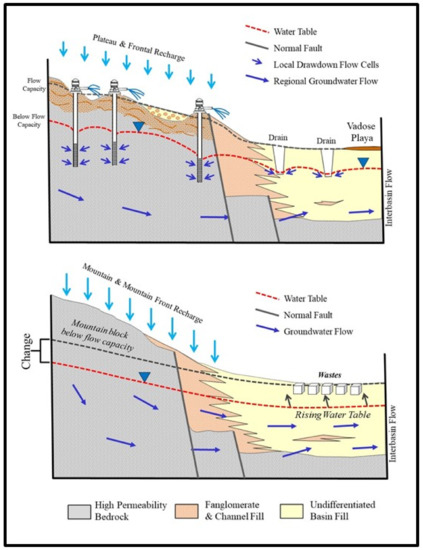

Flow capacity occurs when the water table is at land surface where there is maximum recharge available at a terrain (Figure 1) [1,2]. Flow capacity may be more formally defined as the maximum amount of groundwater recharge that an aquifer system can receive and transmit [3]. Aquifers are not at flow capacity and capillary water will not reach land surface when a water table is at least tens of meters beneath land surface at a desert floor. Paleohydrologic evidence of flow capacity in arid aquifers that are not presently at flow capacity is found in the southwestern Basin and Range province, Africa, Middle East, South America, and in other arid regions in the world. Flow capacity was established in some of these aquifers during the pluvial periods of the late Pleistocene Epoch when precipitation was higher.

Figure 1.

Conceptual hydrogeologic models showing a topographically closed and fully drained basin and a topographically closed and partly drained basin. The basin floor in the topographically closed, partly drained basin is at or nearly at flow capacity (modified from [4]).

This paper is a commentary and review of flow capacity and hydrological problems associated with flow capacity, topics that have received little attention in the peer-reviewed literature except as they relate to paleoenvironments and paleoclimates. As aquifers transition from flow capacity to flow systems below flow capacity, or non-capacity, and vice versa, several practical environmental issues may develop that are of concern and that should be recognized by groundwater scientists and policy makers. Data may be difficult to interpret if a flow system was at flow capacity several thousand years ago, and is in a state of non-capacity today. Examples are shown in this paper where distribution and concentration of hydrochemical and isotopic parameters may be difficult to explain in a flow system that is no longer at flow capacity.

This commentary uses existing data and technical studies that are relevant to aquifers departing from or returning to flow capacity, in both real and hypothetical cases. The paper explores issues of aquifer flow capacity in arid zones, primarily from the perspective of aquifers achieving or losing flow capacity as climate changes or as land-use modification causes water levels to change, leading from flow capacity to non-capacity, and vice versa. The topics are approached in a way that is pertinent to policy and land management.

Flow capacity may occur in mountain blocks, on mountain fronts, and on basin floors (Figure 1). The paper focuses mostly on flow capacity on desert floors (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3) with a supplemental discussion of flow capacity in flanking highlands (Figure 4). A desert floor at flow capacity will have regional saturation up to land surface, usually at the point of lowest topography in a basin or area. Flow capacity in mountain areas occurs more regionally when the highlands have moderately gentle topography, such as is found in mesas and plateaus (Figure 4).

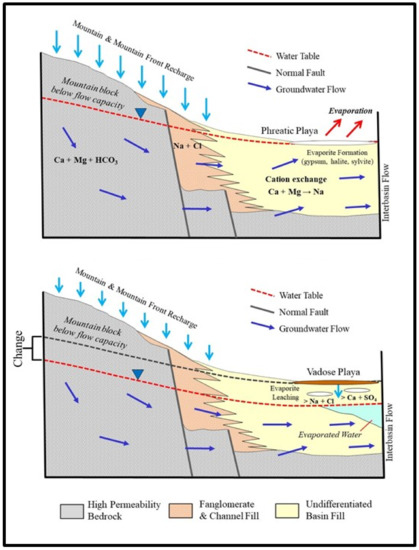

Figure 2.

Representation of mountain ranges and basin-fill aquifers at flow capacity and non-capacity. Water tables are at or near land surface in aquifers at flow capacity. Salt deposits form at phreatic playas, which present a salinity threat to aquifers when the basin floor is no longer at flow capacity due to climate change. Partially evaporated water isotopes (also known as enriched) are formed at phreatic playas and as the aquifer transitions from flow capacity to non-capacity the partially evaporated water may move to water wells down the hydraulic gradient.

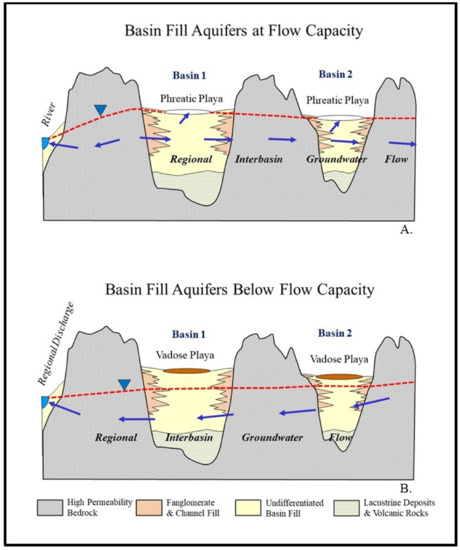

Figure 3.

Conceptual diagram showing interconnected basins at flow capacity and non-capacity. Topographically closed and partly drained basins (A) and topographically closed and fully drained basins (B) are shown. Flow systems with basin floors at flow capacity usually have a phreatic (wet) playa at the basin floor. Regional flow paths may change as basin aquifer systems transition from flow capacity to non-capacity. The surface elevation of the phreatic playas in model (A) regulates hydraulic head and regional groundwater flow.

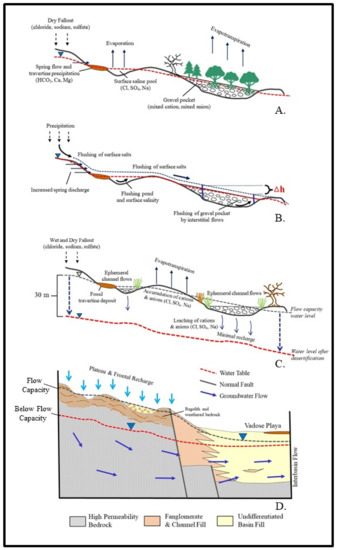

Figure 4.

Flow capacity in mountain areas occurs more regionally when the highlands have moderately gentle topography, such as is found in mesas and plateaus. (A,B) show processes when gently sloping highlands are at flow capacity. (C) shows salt accumulation in interchannel areas and percolation of salts with downward moving wetting fronts in channel areas. (D) shows full model perspective in mountain/plateau and basin floor areas ((A,B) modified from [5]).

1.1. Previous Research on Aquifer Flow Capacity

Flow capacity as a formal hydrogeological term was first coined by Mifflin [1] in his seminal report “delineating groundwater flow systems of the Great Basin, USA”. There is almost no other groundwater literature that was found in the references cited in this paper using the terms “flow capacity” or “terrain capacity.” Sigstadt et al. [6] used the term “underfit aquifer” for an aquifer that is well-below flow capacity, but other terms do not appear in the literature except for summary descriptions, such as “the aquifer is full” or “is at full storage capacity’ quote symbol wrong? In a closely related topic, there is abundant literature on fossil spring deposits and fossil wetlands that developed in flow systems that were once at flow capacity [1,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Studies of fossil springs are often related to groundwater discharge points at the end of regional flow paths, and tied to paleo-environments and long-term climate change, but not necessarily to flow capacity. Fossil springs that developed at the end of local flow paths provide evidence of possible paleo flow capacity. Mifflin described spring-formed mineral deposits such as travertine mounds at land surface, where modern groundwater depths are at least 25 m, too deep for capillary water to reach land surface [1]. These travertine deposits dated from the Pleistocene-Holocene transition and indicated that aquifers that are far from flow capacity today had reached flow capacity several thousand years ago.

Mifflin and Wheat reinterpreted areas described as pluvial lakes of Wisconsin age to have formed from groundwater discharge deposits at fossil springs and fossil wetlands [8]. Quade examined stratigraphic units and soils of late Pleistocene to Holocene age at Corn Creek Flat and Tule Springs, Nevada, USA to evaluate transitioning from marsh-forming sediments to dry desert soils when groundwater table fell at least 25 m due to climate change [9]. Changes were accompanied by major vegetation shifts from marsh varieties to sagebrush and desert scrub along with the decreased activity of biota. Quade and Pratt examined desert landscapes in Indian Springs Valley, Nevada USA for evidence of shallow groundwater during the late Pleistocene and reinterpreted extensive green mudstone deposits as groundwater discharge deposits that were not of lacustrine origin as had been previously thought [11]. Quade et al. indicated that water level changes of 10 m are common in the Great Basin since the last full glacial period, and as much as 95 m of change took place in Coyote Springs Valley, Nevada, USA [12].

Hibbs et al. developed a numerical groundwater flow model and pathline simulator to estimate recharge rates needed to bring a simulated region in a Chihuahuan Desert basin-fill aquifer to flow capacity [2]. The model was first calibrated under the present conditions of quasi-steady-state and negligible groundwater pumping than used to compute the recharge rate needed to bring the water table to land surface. In another modeling study, Matsubara and Howard developed a spatially explicit hydrological model for the Great Basin to predict runoff and mega lake formation when the model was parameterized with temperature and precipitation values for late Pleistocene conditions [14]. Pigati et al., studied the paleo record for long-term wetlands formed by groundwater discharge at Valley Wells, California, USA during the late Pleistocene and evaluated the wetland/vegetation transition as water tables fell [15]. By the Holocene, no evidence of wet conditions was found in the sediment record at Valley Wells.

Previous studies focused primarily on paleohydrology and palaeoclimatological issues related to late Pleistocene to Holocene climate change. Some investigations looked at how animal and plant life adapted or transitioned to other types as the climate dried during the Holocene. Studies on the environmental effects of flow systems transitioning from flow capacity to non-capacity, such as contamination of groundwater, have been much more limited [2,3,12].

1.2. Relationship of Flow Capacity to Internal Playas in Groundwater Basins

Hydrogeologic controls and meteorological conditions determine if flow capacity can occur in groundwater basins. In developing basins, groundwater pumping and other engineering works add other controls (Figure 5). The principal natural factors influencing flow capacity and non-capacity include moisture availability, topography, hydraulic head relationships in adjacent groundwater basins, and permeability of rock and basin fill, particularly in the intervening strata between basins (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Fault controls are also important and act as either barriers or conduits to groundwater flow in valley-fill aquifers [12]. Moisture is insufficient for flow capacity to be established in most groundwater systems in modern arid zones.

Figure 5.

Upper figure, aquifer development can convert a groundwater basin and highlands from flow capacity to non-capacity. Lower figure, buried wastes may be a threat to aquifers used for waste disposal if the aquifer achieves flow capacity due to climate change.

To understand flow capacity in desert basins, it is necessary to discuss playa types and how they relate to intra-and-inter basin groundwater flow (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Much of the remaining text focuses on desert playas at flow capacity and non-capacity. Aquifers formed by filling of sediments between intervening mountain ranges may be at or below flow capacity and are often defined by the presence of phreatic or vadose playas. Within these “basin fill” or “bolson” aquifers, inland lakes or playas usually exist where basin floors are at flow capacity. Although the terms are often used interchangeably for surface water and groundwater movement, the terms “closed basin” and “open basin” should refer to surface drainage and not to groundwater flow. For groundwater flow conditions within and between basins, the terms “undrained, partly drained, and drained basins” are better used to describe intrabasin or interbasin groundwater movement [1,16,17,18,19,20,21]. This classification scheme avoids the common confusion between discussion of surface water and groundwater movement in and between basins and is the working vocabulary of this paper.

Hydrologic processes of open and closed basins and drained and undrained basins and how these flow systems operate are often related to playa types and at what particular times they act as surface-water and groundwater discharge areas. Playas include (1) phreatic, or wet playas; and (2) vadose, or dry playas (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Phreatic playas are groundwater discharge areas that are moist near the playa surface and have a regional water table no more than a few feet beneath groundwater-surface for the entire year [1,22]. Vadose playas are usually dry because capillary water does not reach land surface (Figure 2). Vadose playas are temporarily filled with water from surface drainage, but the depth to groundwater is too great for groundwater to play a role in the water budget of the dry playa except to sometimes receive recharge when the playa holds surface runoff. Aquifer systems with a phreatic playa along the basin floor are at or are near flow capacity while systems that do not have a phreatic playa are not at flow capacity (Figure 1 and Figure 2). If there is no phreatic playa in the basin and no pumping, groundwater usually discharges by interbasin flow (Figure 2). When there is a perennial lake stand, the water table is usually directly connected to the lake at land surface.

A basin-fill aquifer at flow capacity often has a phreatic playa and sometimes a perennial lake on the basin floor due to a high water table and surface runoff that is appreciable due to melting snow and periods of heavy precipitation. The convention that is used in this paper is a groundwater basin that minimally contains a phreatic playa from regional groundwater flow is effectively at flow capacity (Figure 2). The size and shape of the phreatic playa may vary with climate and basin floor topography. Lakes may come and go seasonally, but effectively the water table is near land surface where a phreatic playa exists in the low part of the basin (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Stephens reports that there are probably hundreds of vadose playas in the arid southwestern United States, and considerably more worldwide [23]. A significant percentage of today’s vadose playas were phreatic playas when the climate was cooler and wetter. The modern environmental problems that may result from the transition of basins to non-capacity have been discussed little in the published literature.

2. Methods

Topics reviewed and developed for this paper include flow capacity related to water level change, water quality degradation by salts and toxic trace elements, and shallow geologic sources of salinity. These factors are evaluated in the context of current policy and management implications of paleo-flow capacity and non-capacity today. Several of the case studies and issues discussed in this paper came from field studies carried out by the author, supplemented by research and data from other studies that are pertinent to flow capacity and non-capacity in groundwater basins. Where appropriate, combinations of existing raw data are presented along with discussion topics (Table 1). Case examples 3 and 4 uses data collected mainly by the author and a few water isotope samples from Newton and Allen [24]. Case example 2 uses raw data collected by Waring and Sims and Spaulding and reinterpreted in relation to modern flow capacity [25,26]. Case examples 1 and 5 uses information developed in studies by Miner et al., Duffy and Al Hassan [27], and Hamann et al. [13,17,28].

A variety of methods were used to collect groundwater samples from the sites investigated in case studies 3 and 4. Field water samples were collected via grab sampling in new HDPE bottles. Sample bottles were soaked and triple rinsed in deionized water and inspected prior to field usage. All bottles were triple rinsed with the water being sampled in the field prior to filling. Groundwater sampling included field-filtered and unfiltered samples. Filtered samples were obtained using 0.45 micrometer filters. Samples were stored on ice until returned to the lab. Sample preservation with acid or other preservatives was performed in the field for those samples requiring it.

Before sampling groundwater from monitoring wells, the wells were purged and stabilized. Well purging removed a sufficient volume of groundwater in the well casing so stagnant water is removed and a representative water sample from the aquifer can be obtained. Representative aquifer water was obtained when temperature, specific conductance, and pH readings taken at two-minute intervals were stable, and the wells were sampled. Checks for stabilization of index parameters were performed after wells had been pumped long enough to purge at least three casing volumes of water from the well bore. After wells were pumped, samples were collected and preserved in accordance with methods required for groundwater. Springs issue continuously and groundwater was sampled at the spring orifice.

All samples for isotopic and hydrochemical analyses were collected in HDPE bottles and sealed with tight-fitting caps, usually leaving no bubbles or headspace if required. Sample containers were clearly labeled with the well or spring identification number, date of collection, type of parameters to be analyzed, and preservation used. The sample was sealed so that opening the sample container without breaking the seal is impossible. The seal adhered to both the cap and the sample container and encompassed the entire perimeter of the mouth of the container.

Groundwater samples were collected for a variety of parameters, but only standard anions, halides, arsenic and arsenic species, O-H stable water isotopes, carbon-14, and tritium are discussed in the abbreviated case examples (Table 1). Stable water isotope measurements were made at the Laboratory of Isotope Geochemistry at the University of Arizona, USA. The hydrogen and oxygen isotopic composition of water was determined using a Finnigan Delta-S Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS) following reduction with Cr [29] or CO2 equilibration [30,31], respectively. Results were expressed as δ2H and δ18O in per mil (‰) relative to the standard VSMOW [32] with analytical precisions of 0.9‰ and 0.08‰, respectively.

Tritium samples were enriched nine-fold through electrolytic enrichment to concentrate the sample and then analyzed by liquid scintillation counting with an LBK Wallac Quantulus 1220. Results are reported in tritium units (1 TU = ~3.2 pCi/L) with the detection limit ranging from 0.6 to 0.9 TU. Tritium was analyzed at the Laboratory of Isotope Geochemistry at the University of Arizona. To analyze carbon-14, approximately 2 cm3 of gaseous CO2 from the water sample dissolved inorganic carbon was extracted by acid hydrolysis on a vacuum line. The CO2 was then analyzed by Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) at the University of Arizona AMS Lab. Results are reported in percent modern carbon (PMC) relative to the NBS oxalic acid I and II standards.

The Anion analysis and halide analysis were performed by ion chromatography in the Hydrogeology Laboratory at California State University-Los Angeles following guidelines in EPA Method 300.0 [33]. Arsenic speciation was performed by ion chromatography inductively coupled plasma dynamic reaction cell mass spectrometry (IC-ICP-DRC-MS) by Applied Speciation of Tukwila, Washington, USA. Where raw data from other sources are used, the methods were reviewed to determine as much as possible if standard methods and procedures were used.

Table 1.

Topics and Case Examples Related to Aquifer Flow Capacity and Paleoclimate and Anthropogenic Change.

Table 1.

Topics and Case Examples Related to Aquifer Flow Capacity and Paleoclimate and Anthropogenic Change.

| Topic | Case Example | Case Example: Source, Data, or Findings |

|---|---|---|

| 3.1. Flow Capacity and Aquifer Water Levels | Example 1. Paleo Spring Discharge in Death Valley, USA | Miner et al. [13] |

| 3.2. Flow Capacity and Groundwater Salinity | Example 2. Paleoclimate and Salinity of Ivanpah Valley, USA | Waring, [25]; Sims and Spaulding, [26]; This Paper |

| 3.3. Flow Capacity and Toxic Trace Elements | Example 3. Arsenic Loading to Ground- water from a Drained Phreatic Playa— San Diego Creek Watershed, USA | Hibbs and Andrus, [34] |

| 3.4. Isotope Hydrology and Flow Capacity | Example 4. Isotopically Evaporated Water in Eastern Hueco Bolson, USA | Hibbs and Ortiz, in press Newton and Allen, [35] |

| 3.5. Flow Capacity, Fossil Hydraulic Gradients, and Groundwater Modeling | Example 5. Variable Density Modeling of Groundwater Flow near a Phreatic Playa | Duffy and Al-Hassan, 1988 Hamann et al. [27,28] |

3. Topics and Case Examples Related to Aquifer Flow Capacity and Paleoclimate and Anthropogenic Change

3.1. Flow Capacity and Aquifer Water Levels

Climate-induced changes in water tables are relatively slow. Changes of tens of meters take thousands of years when climate changes [1,36,37]. This raises concerns about certain types of wastes disposed of in arid groundwater basins (Figure 5). Buried wastes can become inundated if the aquifer achieves flow capacity, which means that “safe” basins with thick unsaturated zones today may not be safe in the future [2,12]. Assessment must focus on wastes that are toxic for thousands of years, especially radioactive wastes and other recalcitrant wastes (Figure 5). Considerable research has been conducted on the vadose zone at proposed high-level and low-level radioactive wastes sites [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Policy makers should also consider the possibility that flow capacity could develop in groundwater basins where water levels are tens of meters and even hundreds of meters below land surface today. Cognizant of this issue, Quade et al. considered the question of water table changes related to climate change at Yucca Mountain, Nevada [12]. Groundwater below the once-proposed nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain is 200 m to 400 m below ground surface (BGS). Quade et al. indicated that groundwater at Yucca Mountain had water levels no more than 115 m higher than it is today as a result of cooler and moister climate [12].

Rapid water table changes of tens of meters over a few decades is usually related to extensive modern development and engineering projects in groundwater basins [47,48,49,50,51]. Aquifer pumping from municipal and agricultural wellfields is the most common reason for aquifer drawdown while artificial recharge, excessive irrigation, seepage from canals, and leakage from aging and degraded pipelines are the most common reasons for water tables rising by tens of meters over a few decades [52,53,54] Change of a system that was at flow capacity to non-capacity by groundwater development in highland areas and by pumping and/or drainage of lowland areas is also common (Figure 5). Interception of stream water or groundwater in feeder hydrological basins will have the same effect, by reducing a water input into the hydrological basin of interest from other basins.

Another condition relating to water levels in desert aquifers pertains to regional groundwater sinks, such as major rivers (Figure 3). Many basin-fill aquifers bounded by highly permeable bedrock units in areas with limited recharge have regional groundwater flow to regional sinks. While there are usually local flow cells within individual basin-fill aquifers, the prevailing flow component for groundwater discharge is often a regional groundwater sink drawing groundwater from multiple basins (Figure 3). Such an example is found in the Eagle Flat/Red Light Draw/El Cuervo Bolson aquifer system in Trans-Pecos Texas and northern Chihuahua, Mexico [20,55]. There, groundwater flows from the Northwest Eagle Flat basin into the Red Light Draw basin with discharge at the Rio Grande. Groundwater in El Cuervo Bolson may flow into the extension of Red Light Draw in Mexico and discharge at the Rio Grande [20]. If connected basins formerly achieved or later achieve aquifer flow capacity, the land surface elevation of adjacent basins can moderate and change the trajectory of groundwater flow paths, leading to different patterns of regional groundwater flow (Figure 3). Where the transition reverses regional flow paths across multiple basins, the provenance of hydrochemical and isotopic tracers that cross multiple basins may challenge hydrogeological interpretations to determine the source of unique constituents using modern hydraulic head data (Figure 3).

Case Example 1—Paleospring Discharge in Death Valley, USA

The provenance of isotope and hydrochemical species just discussed can also be applied to mineral cements deposited from ancient springs when basins were formerly at flow capacity. A variation of this concept was presented by Miner et al. [13], for fossil spring deposits used to date paleo spring discharge in Tecopa Basin, Death Valley USA region. Using oxygen, strontium, and U-series isotopes in their study, a regional groundwater flow component dating back 70 to 285 ka was interpreted along a permeable north-south fault zone along the base of Resting Spring Range. Contemporary models of groundwater flow interpret the dominant flux to come from westward interbasin flow from the Spring Mountains through the Nopah and Resting Spring mountain systems. Miner et al., (2007) concluded that paleohydrologic flow paths and groundwater discharge at fossil springs produced mineral cements that could not develop flow paths that exist today [13].

3.2. Flow Capacity and Groundwater Salinity

Paleo-phreatic playas that formed during pluvial periods in basins that are no longer at flow capacity were commonly tens of meters above the contemporary water table, even when there has been no groundwater development of the basin [12]. Drying climate creates changing conditions where the basin transitions from partly drained to fully drained basin and playas transition from phreatic to vadose playas (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Many of the minerals that were formed in phreatic playas in partly drained basins are highly soluble and are prominent sources of salinity, even after thousands of years of dry climate where phreatic playas are no longer present [34]. Modern phreatic playas and playa margins are known for the formation of carbonates, evaporites, and efflorescent salts such as thernardite [22,56,57,58]. Predominantly muds and sands with abundant gypsum are found in the phreatic playas of the Salt Basin, Texas. Evaporite minerals described as “salines” are also present, including halite and sylvite [22]. Calcite, dolomite, magnesite, and native sulfur are found at specific depths below phreatic playas and at playa margins [22].

Rosen and Warren found concentric rings of gypsum and anhydrite along the inner fringes of the Bristol Playa, a modern phreatic playa in southern California [56]. Secondary carbonates are the dominant minerals forming on the outer fringes of the Bristol Playa, while halite and sylvite are the predominant minerals forming in the interior of Bristol Playa. This assemblage of concentric minerals forming around and in the phreatic playa is known as the “Bulls Eye pattern” [56]. The precipitation of minerals in concentric patterns is determined by the concentration of cations and ions and the solubility constrains on specific minerals. Low solubility carbonate minerals precipitate first along the outer fringes of phreatic playas, followed by gypsum and anhydrite. Halite and sylvite precipitate last due to their high solubility. Efflorescent salts commonly form at land surface throughout the perimeter and interior of phreatic playas wherever capillary water reaches land surface. These surface salts are often removed seasonally by wind deflation [22].

When conditions become more arid, recharge slackens and water tables fall (Figure 2). A phreatic playa may then transition to a vadose playa with more aridity. Saline groundwater and salts that formed at land surface percolate downward with falling water table. Pulses of flood water moving into the vadose playa at a later time often become enriched in salts and may percolate downward to the water table. Leaching of evaporite minerals entrained in fine-textured playa sediments may occur for tens of thousands of years or more after the water table has fallen (Figure 2) [59].

Flow capacity and salinization in mountains and uplands are most relevant to salinization in surfaces with flat or gently sloping topography (Figure 4). Mountain surfaces with steep and highly irregular topography rarely reach regional flow capacity. Gently sloping uplands also accumulate thin veneers of sediments (e.g., a few meters up to 75 m thick) in areas of low topography (Figure 4). These sediment aprons and pediments can be sites for vegetation development. Patterns of temporary concentration of salts develop on uplands with gentle and flat slopes, followed by periods of active flushing when the uplands are at flow capacity (Figure 4).

When flow systems in uplands are not at flow capacity, the salinity dynamics are very different. In arid regions salts accumulate in inter-drainage areas due to the substantial excess of evaporation over precipitation [60,61,62]. There is no shallow water table moderating the leaching of salts. The drainage areas (arroyos, ephemeral channels) are sites for salt leaching and focused aquifer recharge due to ephemeral flows [60] (Figure 4). During years of extreme rainfall (e.g., 100-year events), small masses of the accumulated salts in inter-channel areas may be finally mobilized and carried to recharge. In some cases, the channels shift and flows through areas that were formerly interchannel areas and picks up the accumulated salts. These dynamics explain the dilute, mixed cation-Cl type waters that are often found in alluvial fans in the groundwater basins of the Mexican and American basin and range complex [63,64,65].

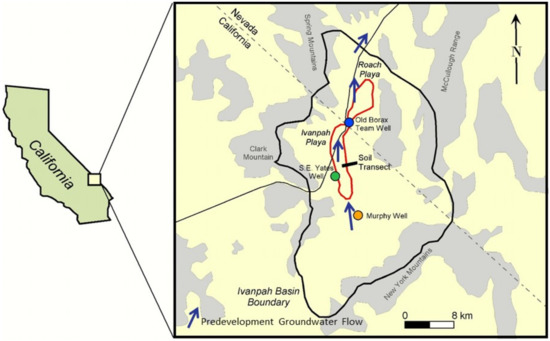

Case Example 2—Paleoclimate and Salinity of Ivanpah Valley, USA

An example of a basin-fill aquifer that was at flow capacity during the Pleistocene-Holocene transitional period but no longer is at flow capacity and may be a source of groundwater salinity is the Ivanpah Valley aquifer of California and Nevada (Figure 6) [66]. In the early 1900s groundwater depth was about 25 m BGS at the lowest elevation in the playa and the Ivanpah Valley aquifer was not at flow capacity [25,67]. The Ivanpah playa was the site for the disposal of mining process water beginning around 1980 and ending in 1998 (ENSR Corporation [68]. These ponds accounted for between 271,500 and 728,000 m3/year of recharge between 1981 and 1997 (ENSR Corporation [68]. The ponds may have intensified the leaching of salts into groundwater beneath Ivanpah Playa. Information replicating predevelopment conditions and pre-dating industrial ponding of water on the playa is best for assessing the leaching of salts due to natural processes (Figure 2). Limited but purposeful data is found in Waring [25] where aquifer water level and basic water quality data were obtained from wells at and near Ivanpah Playa before there was any significant pumping or land use activity in the valley (Table 2). The water well data in Waring [25] were collected from dug wells at and above Ivanpah Playa (Figure 6). On and off-playa groundwater samples from Waring [25] show a clear relationship to evaporite dissolution chemistry beneath the playa (Table 2). On-playa wells, (S.E. Yates and Old Borax Team Well) suggest evaporite dissolution. Off playa well (Murphy) is a dilute sample showing no evidence of evaporite dissolution. In more recent work, Glancy, Moyle and TRC all reported dilute, bicarbonate-mixed cation type groundwaters of less than 1000 mg/L TDS in the Ivanpah Valley at distances from the playa margin [69,70,71]. Glancy and TRC [69,71] report much more saline groundwater near the playa environment with sodium-chloride and sodium-sulfate signatures with TDS in the 5000 to 20,000 mg/L TDS range.

Figure 6.

Site location map at Ivanpah Valley, showing water well locations and transect for soil cores on and off Ivanpah Playa (modified from [26]).

Table 2.

Groundwater data from dug wells at and above Ivanpah Playa (from [25]).

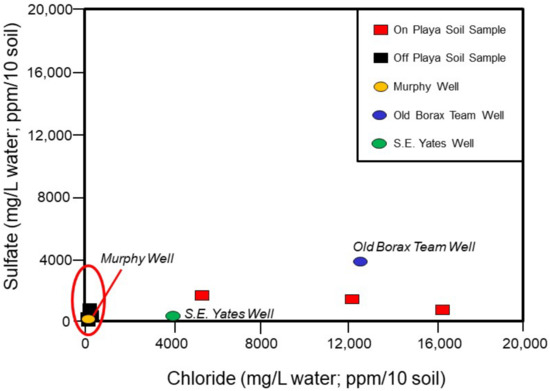

Sims and Spaulding measured soil salinity at Ivanpah Playa [26]. Shallow soil cores for salinity and trace element analysis were collected along a transect on and off the Ivanpah Playa (Figure 6; Table 3). Soil samples were collected off-site where there was no historical industry. At 12 core locations, soil samples were collected at 10 cm intervals to a bottom depth of 50 cm. The mean soil chemistry value of vertical soil cores at each station is presented in Table 3. These data reveal an evaporite signature in samples at Ivanpah Playa, and a much weaker evaporite concentration at stations off-playa (Table 3). When on and off-playa groundwater and soil chemistry data from Table 2 are plotted against adjusted soil concentration data collected on and off-playa from Table 3, a salinity relationship between soils and groundwater is seen (Figure 7). The most likely reason for the contrasting salinity in on-and-off playa groundwater samples is due to the leaching of evaporite salts directly beneath Ivanpah Playa. TRC reported saline groundwater was from the dissolution of playa evaporite salts but did not discuss issues of aquifer flow capacity [71].

Table 3.

Soil chemistry data from soil cores collected at and above Ivanpah Playa (from Sims and Spaulding, 2017).

Figure 7.

Groundwater chemistry data from dug wells at and above Ivanpah Playa (Table 2, from Waring, 1920) plotted against soil chemistry data from soil cores collected at and above Ivanpah Playa (Table 3, from [26]). On playa samples for groundwater and soils (see Figure 6) show a clearly related evaporite dissolution signature. Murphy well is an off-playa well sample upgradient from Ivanpah Playa.

Sims and Spaulding reported that transitional lakes existed in Ivanpah Valley in two Holocene and one Pleistocene-Holocene transitional period [26]. The deepest and longest was a lake unit that was dated at a high stand at ca. 13,090–12,900 years BP. This unit also corresponds to periods of long-standing water environment during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition that was gradually succeeded by drying (ca 14,600 to 8000 years BP reported by Antinao and McDonald [72]). The longstanding lakes in Ivanpah Valley gradually dried precipitated salts, and were succeeded by phreatic playas for perhaps one or two thousand years before the moisture regime diminished when water tables fell below the point that capillary water reached land surface. Today Ivanpah Playa is demonstrably a vadose playa that transitioned from a phreatic playa in the last 15,000 years. In addition to reporting water levels in dug wells 25 m BGS at the lowest point of the playa, Waring [25] reported that groundwater from Ivanpah Valley might discharge along faults and fractures northeastward toward Las Vegas Valley which is also the regional interpretation of modeling of predevelopment groundwater flow by ENSR corporation [68]. This places Murphy well (very dilute groundwater) as the upgradient control well in the early 1900s (Figure 6, Table 2).

Phreatic playa-lake sediments of high salinity that formed when water tables were at land surface are probably the source of salinity in groundwater beneath Ivanpah Playa (Figure 7, Table 2). There were other more recent but smaller and shorter duration Holocene lakes at Ivanpah Playa [26] that may have both precipitated and leached salts, creating a complex transition from phreatic to vadose playas at various times. A vadose playa has existed primarily at Ivanpah Playa for most of the last two thousand years.

3.3. Flow Capacity and Toxic Trace Elements

In addition to the accumulation of salts, modern phreatic playas have been shown to be sinks for accumulating toxic trace elements (e.g., As, Pb, Se, Cu, Zn, Cr) [26,73,74,75]. The mechanisms for trace element accumulation varies, from enrichment due to evaporation and precipitation with evaporites in the salt crusts, to sorption mechanics in the clays and oxides of iron and aluminum disseminated in and below the salt crusts. Gill et al. examined surface crusts in Owens Lake bed, California USA for general salts and select trace elements using Proton-Induced X-Ray Emission [73]. The origin of these salts relates to the history of Owens Lake, which had a high stand 15,000 to 16,000 years ago when surface water flowed out of the lake through Rose Valley, USA [76]. Post-pluvial drying trends and tectonic uplift of the Coso Range led to the cessation of surface outflow from the lake about 3000 years ago, resulting in loss of lake water through surface evaporation. Owens Lake became increasingly saline during this time but collected enough runoff to remain a navigable waterway through most of the 1800s [76]. In 1913 runoff water from the eastern Sierra Mountains began to be diverted to Los Angeles via the Los Angeles Aqueduct, resulting in loss of runoff water into Owens Lake [76]. This caused a significant drop in lake level and resulted in the development of a small brine pool surrounded by a large phreatic playa, by the late 1920s. Evaporative salts began to form in the phreatic playa from upwelling groundwater, dominated first by carbonate and sulfate salts in the early 1920s and later with more salts of chloride forming. Shallow groundwater levels continue to perpetuate the formation of salt crusts at Owens Lake bed playa today [76].

Gill et al. [73] describe three types of surface sediment crusts that predominate in Owens Lake bed; (1) soft surficial soils with white salty appearance, (2) loose salty crusts that are clay and silt dominated and that contain intermittent windblown sands, and (3) hard and clean saline crusts that are clay and silt dominated. Gill et al. [73] found no consistent relationship between any major or trace elements with these three types of crusts. Data from Gill et al. [73] indicate chloride varied from 2.0 to 11.5 percent by weight with 10 of 16 samples between 3.0 and 7.0 percent by weight. Sulfur varied from 0.4 to 5.0 percent by weight with 11 of 16 samples between 1.0 and 3.0 percent by weight. Heavy metals and trace elements reported by Gil et al. [73] as parts per million (ppm) by mass include chromium, detected in all but two samples at levels of 19 to 41 ppm; nickel, detected in all but one sample at levels of 9 to19 ppm; gallium, detected in all samples at levels of 6 to 17 ppm; copper, detected in all samples at levels between 11 and 36 ppm; zinc, detected in all samples at levels between 40 and100 ppm; and rubidium, detected in all samples at levels between 75 and 150 ppm. Arsenic and lead are of special interest at Owens Lake bed due to concerns about toxic elements moving with windblown dust. Arsenic was detected in 14 of 16 samples at levels of 7 to 38 ppm while lead was detected in 11 of 16 samples at levels of 17 to 32 ppm. Most of the samples with arsenic detected were between 10 and 22 ppm. Almost all of the samples with lead detected were between 22 and 38 ppm.

Gill et al. [73] completed their study due to concerns about wind erosion as a source of dust containing toxic elements that could threaten human populations and sensitive desert ecosystems far from Owens Lake bed. Other studies of vadose and phreatic playas focused on potential contamination of groundwater due to the possible leaching of toxic trace elements. Gao et al. [74,75] for example, collected sediment samples at depths varying from 2 to 4 m below land surface in Tulare Lake bed, California, USA and analyzed the sediments for total and sorbed arsenic for the purpose of determining sorption/desorption phenomena in the laboratory. The study was carried out to help determine the potential for arsenic contamination of shallow groundwater and thence deeper potable groundwater. Tulare Lake, having a very different history than Owen Lake, was the second-largest freshwater lake based on the surface area, in the United States in the mid-1800s, (ECORP [77]). Tulare Lake received runoff from several large rivers including the Kings, Kaweah, Tule, and Kern Rivers (ECORP [77]). The lake had a natural outlet to the San Joaquin River Basin whenever the lake level was above 207 ft (63 m). Tulare Lake water reportedly flowed out of Tulare Lake Basin during 65% of the years from 1850 to 1878 (US Bureau of Reclamation, 1970; ECORP [77]). In the 1860s the flow of the Kings River began to be diverted for irrigation. From that point on, increasing diversions of flows from streams tributary to Tulare Lake led to drying of the lake by 1899, and the end of perennial lake conditions. The lake continued to be flooded intermittently, often for a number of years at a time during the 20th century [77,78].

Irrigation works and dams were completed in the 19th and 20th centuries on the rivers and streams that flow into Tulare Basin. Tulare Lake bed was then redeveloped to manage intermittent flooding through a series of levees, water detention cells and storage basins, and extensive drainage works [77,79]. The lakebed was farmed in various areas throughout the 20th century and is extensively farmed today.

Tulare Basin is topographically closed and mostly undrained, and salts accumulate in shallow groundwater due to the irrigation and drainage works. Surface evaporation ponds have been constructed in areas of low elevation to collect agricultural drainage water and to keep saline groundwater from moving into the crop rooting zones [77,79,80]. Shallow groundwater beneath Tulare Lake bed is brackish to saline (2000 to about 20,000 mg/L) [80] with elevated concentrations of several minor and toxic trace elements, including boron, molybdenum, uranium, arsenic, and selenium [75,81,82]. Elevated concentrations of arsenic in soils and shallow groundwater is of particular concern, due to potential leakage from the shallow contaminated aquifer to deeper aquifers in Tulare Basin that could be used for future drinking water supply [75]. The original source of arsenic in Tulare Basin is derived from weathering of marine sedimentary rocks in the mountains surrounding the basin [75].

Gao et al. [74] found that the sediments collected below Tulare Lake bed averaged about 24 mg/kg arsenic. About 25% of this arsenic was adsorbed, and about 60% of the adsorbed arsenic was released to soluble forms during laboratory extraction tests. Further results showed that the sediments beneath Tulare Lake bed were oxidized, and that pore water extracted from the sediments contained a total arsenic concentration of about 590 μg/L. The arsenic adsorbed on sediments was predominantly in the most oxidized (+5) form, with 97% in the form of arsenate (+5) and about 3% as arenite (+3) [74,75]. Organic forms of arsenic were not detected in the sediments collected by Gao et al. [74]. Based on these results, Gao et al. [74], concluded that adsorbed arsenic could be a significant source of arsenic contamination of groundwater due to desorption and leaching processes beneath Tulare Lake bed. Factors that affect arsenic movement and leaching rates include sediment characteristics, such as the presence of clay minerals and oxides of iron and aluminum coating many of the sediment particles [75]. The sediments below Tulare Lake bed demonstrated high adsorption capacity for arsenate, while the high pore water concentration of arsenic indicated active desorption and/or solubility of arsenic [74,75]. Gao et al. concluded that the mechanisms controlling sorption and desorption of arsenic associated with leaching processes are not well understood in Tulare Lake bed sediments and shallow groundwater, and that further study is warranted [75].

Case Example 3—Arsenic Loading to Groundwater from a Drained Phreatic Playa—San Diego Creek Watershed, USA

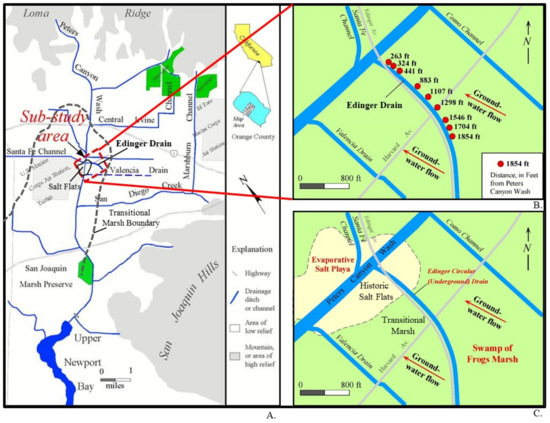

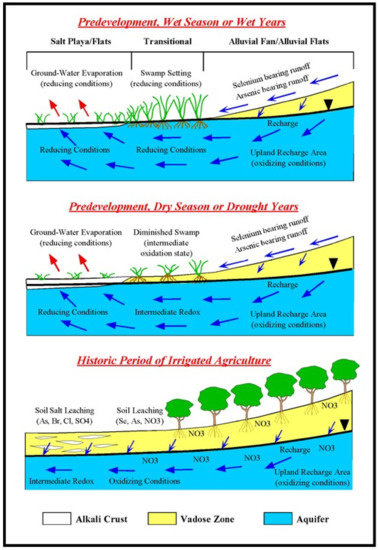

As a follow up to the work of Gao et al. [74,75] this case study focuses on arsenic leaching into groundwater after drainage of a phreatic playa that contained large amounts of arsenic in playa surface salts [34]. Arsenic concentration in groundwater is correlated with the dissolution of evaporative salts that also formed in the phreatic playa. Drainage of the marsh/playa complex in the mid to late 1800s depressed groundwater about 15 feet (4.6 m) beneath land surface. The loss of the phreatic playa due to intentional drainage and the case example serves as an analog of a phreatic playa transforming from flow capacity to non-capacity during the early stages of drying climate.

The study was conducted in the San Diego Creek Watershed on the southern end of the Los Angeles Coastal Plain, California (Figure 8). The watershed area has flat topography in interior areas. Topography increases where land surface rises gradually to the alluvial aprons along the surrounding mountain ranges (Figure 8). The central part of the watershed was a marshland and salt flat at flow capacity until the 1870s. The historic marsh was known to the locals of the time as “La Cienaga de las Ranas,” or “Swamp of the Frogs” [83] Drainage ditches and channels, some of which still exist, were constructed to drain the marsh for grazing purposes and for irrigated agriculture (Figure 8). San Diego Creek Watershed is a rapidly urbanizing area today.

Figure 8.

Physiographic features in San Diego Creek Watershed (A), and Edinger Drain study area (B), showing groundwater sampling points at springs and seeps issuing into Edinger Drain. The distance from groundwater seepage points to Peters Canyon Wash identified the groundwater sampling points in red dots. Edinger drain crosses an interpreted historic alkali flat (i.e., evaporative salt playa; or phreatic playa) that is an important source of high arsenic in the area (C).

Heavy trace element and nutrient loads had been previously identified in surface flows in San Diego Creek Watershed [84,85,86]. These toxins and nutrients threaten the habitat of migratory waterfowl and other species. San Diego Creek Watershed hosts a very active migratory and non-migratory bird population. Upper Newport Bay, the coastal receiving water body for these watersheds is a protected ecological reserve that is home to five threatened and endangered bird species (Figure 8). A principal source of arsenic loading is from shallow groundwater discharging into surface channels [86]. Following the work of [86], the author performed a detailed reconnaissance of the Edinger Drain (Figure 8) to try to determine sources of elevated arsenic issuing out of the drain. Flows out of Edinger Drain had consistently shown the highest arsenic concentrations in the watershed, varying from 20 to 40 ug/L. Most other channels had dry weather discharge with less than 10 ug/L arsenic.

During channel reconnaissance, many groundwater seeps and spring flows were identified at Edinger Drain. Nine of the springs and seeps were selected for sampling during detailed studies completed in March 2007 (Figure 8). Edinger Drain is oriented in line with a groundwater flow path, allowing the changes of groundwater hydrochemistry to be observed at the springs oriented in line with the flow path. The flow path is oriented first through a historic “Transitional Swamp” region, then through the historic evaporative salt flat that existed in the predevelopment period (Figure 8 and Figure 9). Edinger Drain now issues into Peters Canyon Wash, the principal drainage stream in the upper part of the watershed that flows into Upper Newport Bay, and thence to the Pacific Ocean. The salt flats at the phreatic playa no longer exist, and shallow groundwater beneath the historic Salt Flats reaches 40,000 mg/L TDS. Salt enriched crusts are identified in soils reports developed shortly after the marsh and salt flats were drained [87,88]. Agriculture and urban grading left no trace of the marsh and salt flats at the surface, aside from some residual white salty material that sometimes collects at land surface by soil capillarity in the fine-textured soils formed in marshes and salt flats.

Figure 9.

Time series conceptual models for water table and land surface conditions along a transect along Edinger Drain and Valencia Drain (Figure 8) showing conditions that are postulated to occur pre-and-post drainage of the marsh (swamp) and salt flats.

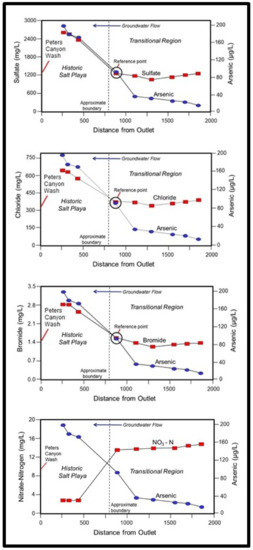

The groundwater sample collected at the furthest upgradient point (1854 ft in Figure 8) contained 13.5 ug/L total arsenic (Table 4 and Figure 10). Arsenic concentration increased only a small amount initially along the groundwater flow path, and then increased to 90 ug/L at the boundary between the “Transitional Swamp Region” and the “Historic Salt Flats.” From there arsenic more than doubles in the Salt Flats region (Figure 9 and Figure 10) where the maximum arsenic concentration in groundwater increased to 196 ug/L (Table 4 and Figure 10). Arsenic in all groundwater samples is in the (+V) oxidation state (Table 4).

Table 4.

Arsenic Speciation Data for Edinger Drain—Groundwater Seeps, March 2007.

Figure 10.

Graphs showing concentrations of sulfate and arsenic, chloride and arsenic, bromide and arsenic, and nitrate and arsenic in groundwater sampling points at Edinger Drain. The reference point is calibrated on the axis scale so the points overlap directly for the ions on the relative axes right above the salt flats (dashed line). As groundwater flows through the alkali flats region (left of dashed line), sulfate, chloride, bromide, and arsenic increase in a proportional manner, whereas nitrate decreases sharply in concentration. Evaporative enrichment of arsenic and salts of sulfate, chloride, and bromide is implied in the alkali salt flats region.

Sulfate, chloride, and bromide are plotted alongside arsenic along to examine possible correlations with highly soluble salts along the flow path (Figure 10). Anions change little in groundwater until the groundwater flow path reaches the salt flats, then anions increase considerably in concentrations. Comparing arsenic and sulfate first, the ions increase proportionately in groundwater in the Historic Salt Flats (Figure 10). Visual comparison along the flow path is obtained by creating a “reference point” that is adjusted so that the concentration scales for sulfate and arsenic match (see Figure 10 and find “reference point”). Sulfate and arsenic values overlap directly at the “reference point.” Downgradient from the reference point, sulfate and arsenic concentrations increase proportionately (Figure 10). Repeating the process for chloride and bromide, slightly weaker but positive correlative results are found with arsenic in the salt flats region (Figure 10). Anions and arsenic increase in a fairly proportional manner within the Historic Salt Flats, with sulfate and arsenic showing the closest correlation (Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11). Soils are enriched in arsenic in the Salt Flats area. Three shallow soil samples collected near Edinger Drain at a depth of 1.5 m in the historic salt flats region contained 27.0, 32.0, and 41.0 mg/kg arsenic. Control areas above the Swamp of the Frogs region contained 1.5, 3.2, and 7.7 mg/kg arsenic at a depth of 1.5 m.

Figure 11.

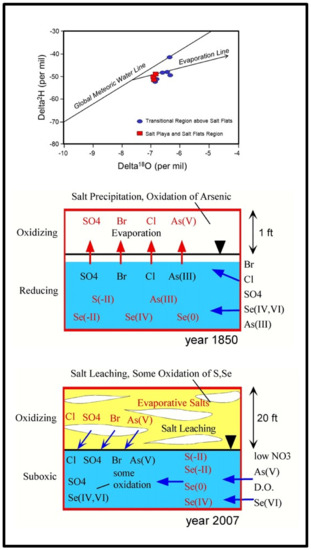

Stable isotope data for groundwater from Edinger Drain, showing the evaporation line that defines most shallow groundwater in San Diego Creek Watershed [34]. Groundwater within the Transitional Swamp Region and Historical Salt Flats is usually isotopically similar. This means that saline groundwater within the salt flats forms from dissolution of salts during aquifer recharge, and not due to pure evaporation of groundwater. The conceptual model for this leaching process, pre-and-post drainage of the marsh and salt flats (Figure 9), is shown in the model above.

A model for arsenic and anion enrichment along the flow path is as follows; soluble anions and arsenic moved with subsurface water and floodwater into the Historic Salt Flats. Soluble salts did not accumulate in the transitional swamp region because salts were periodically flushed by periods of heavy surface runoff and high water tables (Figure 9 and Figure 11). Soluble salts accumulated in the salt flats area where a phreatic playa existed (Figure 9). Arsenic and soluble anions increased in the Historic Salt Flats, because masses of Cl, SO4, Br, and As precipitated in the evaporative salts crusts due to groundwater evaporation. When the marsh and salt flats were drained, residual salts remaining in unsaturated soils at the salt flats began leaching into groundwater (Figure 11). This carried large masses of Cl, SO4, Br, and AS (V) into shallow groundwater. The arsenic has remained in the most oxidized +5 state in groundwater (Table 4).

Oxygen and deuterium isotopes in groundwater show no evaporative enrichment along the Edinger Drain flow path because there is no change in stable water isotope signature down the hydraulic gradient (Figure 11). This indicates that elevated salinity in groundwater must be due to second cycle dissolution of previously precipitated solid salts, and not due to evaporative enrichment of solutions of shallow groundwater (Figure 11). The three groundwater samples collected in the historic salt flats region are actually the least evaporated groundwater types based on stable water isotope results (Figure 11). Almost all samples are clustered along an evaporation line previously identified for shallow groundwater throughout San Diego Creek Watershed [34], but there is no evaporative enrichment shown by the stable water isotopes between data points at the salt flats and transitional marsh region.

After the drainage of the marsh and salt flats, the area was developed for irrigated agriculture (Figure 9). Nitrogen fertilizer was applied to crops above the Historic Swamp of the Frogs Marsh in alluvial fan soils that are well-drained and have little concentration of soluble salts. Nitrate from the fertilizer has moved down the hydraulic gradient into the transitional marsh region (Figure 10). A notable decrease in nitrate in the salt flats area indicates either that the nitrate from historic agriculture has not moved as far as the historic playa flats, or nitrate is lost by denitrification (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Details on redox conditions, other trace elements, and arsenic sources and transformations above the salt flats in the historic swamp region are found in [34]. The findings are presented here for arsenic and salts only and with reference to arsenic accumulation and leaching from salt crusts in the historic salt flats (Figure 11).

3.4. Isotope Hydrology and Flow Capacity

Groundwater in desert basins is often old; bulk ages of 15,000 years or more are not uncommon. Arid basins may contain mixtures of old (>20,000 years) and young (<500 years) groundwater with bulk ages indicating the overall age of the mixture. Gently sloping hydraulic head gradients and limited modern recharge rates are factors controlling the age of groundwater stored in arid groundwater basins. An indirect method has been used to approach the problem of differentiating between late Pleistocene and post-Pleistocene groundwater ages based on the combined use of carbon-14 with water isotopes with a known temperature-fractionation effect [55,89,90,91]. Carbon-14 is one of the most widely used tools for age-dating groundwater up to 40,000 years [92,93,94]. The use of carbon-14 for dating the age of groundwater is complicated by numerous factors. The most critical factors are water/rock and sediment/rock interactions incorporating “dead carbon” in groundwater due to dissolution of carbonate rocks and cements, and mixing between young and old groundwater. The mixing of waters can usually be determined by using tritium, tritium-helium, or chlorofluorocarbons with carbon-14 or other isotopes measuring both old and modern groundwater in a mixture. Dead carbon renders apparent groundwater ages older than the true age of groundwater [92,94]. Correction factors have been developed for cases where carbon-13 of rocks and sediment cements show little variability, but the correction factors are dubious where heterogenous mixtures of rock types are found in bounding mountain ranges and basin fill in arid basins. Combinations of rocks and sediments of several types, including igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks and their erosional derivatives are commonly found in many arid groundwater basins.

The indirect approach to differentiating between late Pleistocene and post-Pleistocene groundwater ages has been used successfully in groundwater basins with heterogeneous rock and sediment types where carbon-14 correction factors are not very reliable [55,89,90,91]. A depleted water isotope signature is derived from lower temperatures and heavier precipitation associated with the late Wisconsin glacial period, when temperatures in the southwestern United States may have been 5 to 8 °C cooler [55,89]. The correlation between small percentages of modern carbon in groundwater (<10 PMC for example) and isotopically depleted water provides a semi-quantitative means of age dating pluvial groundwater.

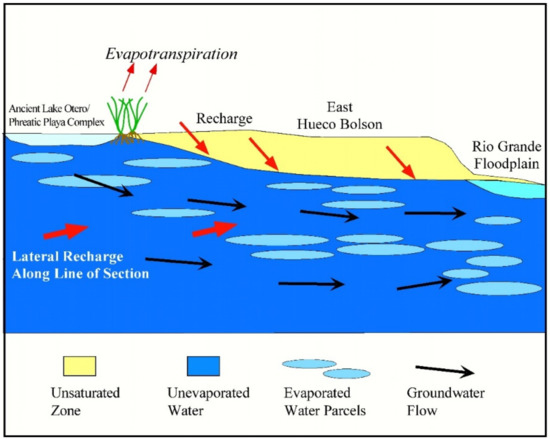

Stable water isotopes and carbon-14 data are useful in studies of paleo-flow capacity in arid groundwater basins. Groundwater evaporates partially at shallow phreatic playas and stable water isotopes become isotopically enriched [22,95]. Isotopically evaporated (enriched) groundwater begins to accumulate beneath playa surfaces. Groundwater beneath a phreatic playa becomes more dense and may begin to descend in an aquifer by convection [27]. Isotopically enriched groundwater may also move down the hydraulic gradient while mixing with native groundwater (Figure 2). Down the hydraulic gradient and after thousands of years, this unit of mixed-evaporated water might be detected during well sampling if its original volume is great enough.

Evaporation of water can also occur in arid environments prior to recharge due to temporary ponding at land surface [92] or where water resides in the uppermost vadose zone before a pulse of recharge from heavy rain or flood mixes with evaporated water in the vadose zone and carries it downward [92,96]. These contemporary processes may be observed or investigated by field monitoring. If these modern sources of evaporation are ruled out, a hydrogeologic interpretation may be challenged to determine a source of evaporated water in an aquifer where water tables are everywhere 30 to 150 m BGS today. By back-calculating the evaporation trajectory to the meteoric line, the use of carbon-14 with the evaporated water may indicate evaporated water is more depleted at the intercept with the meteoric line than can be explained by modern climates, leading one to conclude that the evaporated water is of pluvial origin and may have evaporated partially when the groundwater basin was at flow capacity during the late Pleistocene.

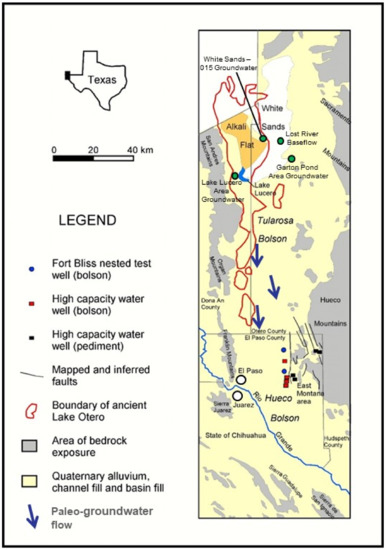

Case Example 4—Isotopically Evaporated Water in Eastern Hueco Bolson, USA

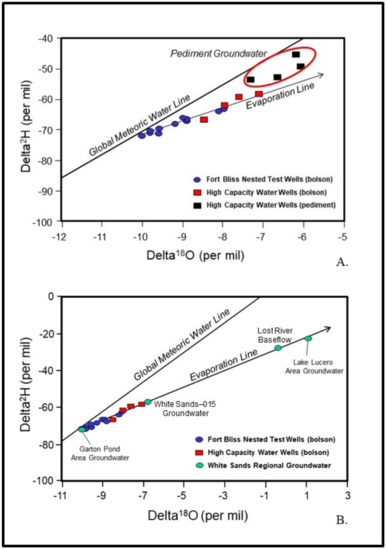

A paleohydrologic source of evaporated water from an ancient paleo lake/phreatic playa complex is described for the eastern Hueco Bolson [35]. Heavy evaporated water is found at the east side of the Hueco Bolson in the east Montana area, where the depth to groundwater is 90 to 105 m BGS (Figure 12 and Figure 13). Evaporation during recharge at a contemporary recharge area at a mountain pediment east of the basin bounding fault, adjacent to the east Montana area, was quickly disregarded as the source of evaporated water because the pediment contained both old and modern groundwater with a unique stable water isotope signature that differed from east Montana area groundwater (Figure 12 and Figure 13). The hydraulically connected Tularosa Basin, north of the Hueco Bolson, had an identical evaporative water isotope signature as east Hueco Bolson groundwater, many tens of kilometers upgradient at White Sands National Monument [24,35]. The evaporation line at White Sands was identified by an old groundwater endmember entering the deeper aquifer at White Sands area that was not evaporated, and a very evaporated groundwater endmember near lake Lucero [24] (Figure 12). Two other samples from the White Sands area plot right on the evaporation line as does east Montana area groundwater (Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Location map for isotope results in the east Hueco Bolson, showing current physiographic features and approximate boundary of historic Lake Otero (Lake Otero boundary from [97]; base map modified from [2]; mapped and inferred faults [98,99]).

Figure 13.

Partially evaporated water is found at the east side of the Hueco Bolson in the east Montana area, where depth to groundwater is 90 to 105 m BGS (Fort Bliss Nested Test Wells and High Capacity Water Wells). Evaporation during recharge at a contemporary recharge area at a mountain pediment east of the basin bounding faults, adjacent to the east Montana area, is an unlikely source of evaporated water, because the pediment contains both old and modern groundwater with a unique stable water isotope signature that differs from east Montana area groundwater (Pediment Groundwater) (A). The hydraulically connected Tularosa Basin, north of the Hueco Bolson, has an identical evaporative signature as east Hueco Bolson groundwater along a trajectory from White Sands National Park to the east Montana area (green dots, (B)). These results suggest Tularosa Basin is the likely source of evaporated water in the east Hueco Bolson. Groundwater likely moved into the east Hueco Bolson from the site of ancient Lake Otero, and/or from surrounding phreatic playas in Tularosa Basin where groundwater was at or near land surface (White Sands data from [24]; Fort Bliss samples collected by El Paso Water Utilities; other groundwater samples collected by Barry Hibbs).

Based on these results, Tularosa Basin is a likely source of evaporated water in east Hueco Bolson (Figure 12 and Figure 13). Groundwater recharged along the Franklin and Organ Mountains on the western side of the Hueco Bolson all plot near the meteoric water line and show little to no evaporation [100]. Evaporated groundwater may have moved into the east Hueco Bolson from the site of ancient Lake Otero, and/or from surrounding phreatic playas in Tularosa Basin where the groundwater was at or near land surface during the late Pleistocene-early Holocene transition (Figure 12 and Figure 14) [35]. The apparently old age of the two endmember groundwaters at White Sands, based on C14 results (uncorrected 9000 to 22,000 years BP) [24] is consistent with the age of groundwater in the bolson aquifer in the East Montana area (<7 PMC). The only other sample from White Sands with carbon-14 data was a regional groundwater sample at Alkali Flats that had an uncorrected carbon-14 age of 3720 years with 4.20 tritium units, suggesting it contains very young water (<50 years) that is probably mixed with slightly older groundwater (500 to 2000 years BP). This sample also plots directly on the evaporation line (green dot closest to Garton Pond in Figure 13) indicating that both old and young groundwater from White Sands follows the same evaporation trend. This might preclude the presence of a significant climatic shift on stable water isotope signature in this part of the Tularosa and Hueco bolsons. That the groundwater from Eastern Hueco Bolson plots on the evaporation line in Figure 13 and is old (<7 PMC) and that all groundwater collected at White Sands plots on the same evaporation line, with 2 of 3 samples with C14 data appearing to be old groundwater, suggests that all groundwater on the evaporation line is from the same evaporative source, probably from ancient Lake Otero or related phreatic playa complexes. The intercept of the evaporation line with the meteoric line gives an approximate value of the original isotopic signal of the source of recharge. The value of −74 δ2H and −10.2 δ18O per mil (‰) at the intercept between the two lines (Figure 13) is entirely consistent with water that was recharged in this area during the cooler and wetter climate of the late Wisconsin glacial period [91].

Figure 14.

Conceptual model for groundwater flow from a partially evaporated (or enriched) water source near historic Lake Otero, extending across the Tularosa Bolson into the east Hueco Bolson and moving to the El Paso-Juarez Valley (Rio Grande Floodplain).

Interpretations of isotope hydrology need to consider contemporary and historic sources of evaporated groundwater where there are multiple potential sources in a basin below flow capacity. By examining the paleohydrology, possible ancient shorelines and paleo wetlands, possible fossil spring cements, basin-fill lithofacies, and evidence of paleobiologic activity consistent with wetland and phreatic playa settings, a suitable interpretation can be made. Looking for contemporary sources of evaporated groundwater in a basin that is presently not at flow capacity may be a false lead if the basin was at flow capacity thousands of years ago.

3.5. Flow Capacity, Fossil Hydraulic Gradients, and Groundwater Modeling

Fossil hydraulic gradient is a non-steady state condition in an aquifer that is a residual of groundwater mounding that occurred when the climate was far wetter. Groundwater is losing potential but has not reached an equilibrium state. Fossil hydraulic gradients may have developed in arid regions where groundwater mounds were established during the late Pleistocene climate, when conditions were cooler and wetter [101,102,103,104,105]. Hydraulic gradients are steeper than expected when compared to modern rates of recharge where fossil hydraulic gradients might exist [105,106,107]. The residual hydraulic head gradient is an artifact of higher recharge rates during pluvial periods. Thousands of years later, the only formations that are likely to have fossil hydraulic gradients are low permeability strata, such as is commonly found in mountain blocks.

Fossil hydraulic gradients have been the subject of commentary by groundwater scientists for more than 40 years [101,102,106]. The question of fossil hydraulic head gradients is of practical importance. Discharge from mountain springs is controlled by a hydraulic head in surrounding terrains, and if the hydraulic head is decaying due to fossil hydraulic gradients, it adds another factor that is relevant to long-term spring sustainability, even where no groundwater is pumped. Many endangered and threatened species and most other desert species depend on springs in arid zones.

Fossil water is often associated with fossil hydraulic gradients and may be loosely, but commonly defined as water recharged during the wetter periods 10,000 to 30,000 years ago [101,108]. Others have defined fossil groundwater on a process level, that the present rate of recharge is negligible in comparison to the extent and groundwater storage in the modern aquifer [109,110]. The existence of fossil hydraulic gradients and fossil water was postulated to occur due to the fact that current groundwater levels in some aquifers seem to be inconsistent with modern recharge and discharge rates. Modern recharge rates were determined with environmental isotopes, water balance estimates, and numerical modeling. In some studies, groundwater discharge was estimated to be much greater than groundwater recharge when there was no extraction from the aquifers, suggesting that fossil hydraulic gradients are likely to exist [107,111].

Some of the studies of fossil hydraulic gradients presume that current recharge is negligible or even zero, and that only fossil hydraulic gradients can explain areas where hydraulic head gradients are much steeper than expected under conditions of negligible recharge [107]. In an analysis of steeper than expected hydraulic gradients in arid aquifers in North African and Arabia, Bourdon started with the apriori assumption that arid groundwater basins contain only fossil groundwater and there is net-zero modern recharge [101]. To explain the hydraulic gradients in the absence of modern recharge, Bourdon evaluated several other possibilities for hydraulic head gradients, including: (i) fossil hydraulic gradients; (ii) tilting of basins; (iii) compaction effects due to sedimentation, loading from Holocene volcanic flows, and water loading/unloading; (iv) thermal processes and drive; (v) gas drive; (vi) lowering of discharge levels of aquifers by mechanisms such as tectonic displacement and land subsidence; and (vii) changing water levels in the discharge zone, such as lowering of lake levels by evaporation and evaporation from sabkhas [101]. Combinations of these mechanisms can contribute to steeper hydraulic gradients in some of the aquifers studied, but are insufficient to produce modern hydraulic heads without at least some modern recharge [101].

Systems that might have fossil hydraulic gradients today may or may not have been at flow capacity at the height of groundwater recharge when the hydraulic head was at its recent peak 10,000 to 30,000 years ago. It is interesting to note that fossil hydraulic gradients and flow capacity have been evaluated differently, with many papers and dissertations addressing fossil hydraulic gradients as referenced in this section but with flow capacity evaluated mostly in relation to paleoenvironments such as paleowetlands. As shown in this commentary and review, there are several reasons why flow capacity should be considered concurrently with the analysis of fossil hydraulic gradients. A groundwater system that was at flow capacity during the late Pleistocene sets the maximum hydraulic head possible and may provide a means of comparing modern hydraulic gradients and fossil hydraulic gradients. This review paper has presented a number of lines of evidence of flow capacity during pluvial periods, including the presence of evaporated water in basins, the occurrence of unexplained evaporative salts, the identification of unique isotopes and hydrochemical species related to provenance, the presence of fossil spring deposits at paleo-spring orifices at land surface, and the evidence for paleowetlands and associated biological communities associated with the recent fossil record. All of these may aid in determining flow capacity when the climate was cooler and may provide insights on the possibility of fossil hydraulic gradients in modern flow systems. Flow capacity often leaves evidence in the form of dateable mineral cements that precipitated at the orifice of paleo-springs and sediments and biological proof of flow capacity in the record of lifeforms preserved at paleowetlands. It is much more challenging to prove that fossil hydraulic gradients exist. The two concepts should be explored mutually because they are often interrelated.

3.6. Fossil Hydraulic Gradients and Modeling Protocol

Steady-state models are often developed to simulate predevelopment conditions as an initial step in model calibration. Modeling of steady-state, predevelopment conditions provides initial conditions as needed for transient models. Most aquifers in arid zones were not developed until the late 1800s to early 1900s when drilling technology allowed water wells to be drilled hundreds of meters deep. Predevelopment conditions usually go back only 100 to 150 years. An exception to this rule of thumb is found in some of the groundwater systems that were developed thousands of years ago in ancient civilizations, primarily in the middle east and north Africa, where an intricate series of tunnels and shafts for collecting groundwater, known as qanats were constructed [112,113,114]. These are found in relatively few arid groundwater basins elsewhere. If groundwater systems are not in a quasi-steady state due to fossil hydraulic gradients, steady-state assumptions in predevelopment models may present questions about how to set initial conditions in models [105,107]. It has already been noted that fossil hydraulic gradients are not likely to occur except in formations of low hydraulic conductivity, such as those found in mountain blocks and in some bedrock formations. More commonly, permeable formations such as basin-fill aquifers have sufficient permeability that the response of the aquifer to changing climate generally follows the climate change trajectory reasonably well, and remains in a state of quasi-steady-state equilibrium as the climate becomes drier. Bounding mountain blocks and underlying bedrock formations are included more and more in the active cells of model grids in basin-fill aquifers however [115,116,117,118]. The assumption of steady-state conditions may be relevant to model development if fossil hydraulic gradients exist in any part of the active model domain. Some of the regional groundwater models in arid zones cover areas as large as countries such as Jordan (~89,000 km2), and include many geologic materials, including heterogeneous basin-fill material and intervening bedrock formation in mountains, or beneath basin-fill deposits. It is possible fossil hydraulic gradients exist in parts of those regions.

Groundwater modeling is one of the most important tools for assessing the possibility that fossil hydraulic gradients exist in basins. Various models have been developed to test assumptions of groundwater recharge that might produce fossil hydraulic gradients. In an early modeling effort, Lloyd and Faraq used a resistance-analog model of a conceptual basin to test combinations of hydraulic conductivity and storage coefficients and evaluate conditions leading to fossil hydraulic gradients [102]. Lloyd and Faraq concluded that fossil hydraulic gradients could exist today in some of the modern arid basins [102]. Wright et al. developed a numerical model of the Kufra and Sirte basins in eastern Libya to test water balance anomalies [119]. They decided that present water levels may be fairly close to equilibrium. Heinl and Brinkmann developed a two-dimensional horizontal finite element groundwater model for simulating large-scale flow from part of the Nubian aquifer system [104]. The model evaluated significant amounts of water stored in the aquifer that may represent non-equilibrium conditions. Heinl and Brinkmann suggested that large amounts of fossil water are stored, fossil hydraulic gradients exist, and part of the aquifer has been in a natural state of depletion as a result of the decay of pluvial recharge mounds over several thousand years [104].

To provide circumstantial evidence of the timing of recharge and if unsteady conditions existed, Houston and Hart developed a numerical model to test paleo and modern recharge with a generalized adaptive model configured after basic features of the Salar de Veronica Basin of Chile [120]. Their results indicate recharge has taken place within the last 1000 years in smaller basins of western Chile (e.g., 500 km2). Timing of recharge took place during episodic events as a result of centennial-level forcing such as changes in solar or cosmic-ray activity. In the smaller basins in Chile without well extraction, a major recharge event several hundred years ago means that residual heads are present, that these are in decline for shorter centennial intervals of recharge, and that environmental change, such as reduced spring flow, will likely take place. Another pulse of recharge of centennial periodicity could occur at any time and reset the process.

Schulz et al. claim that model non-uniqueness issues during model calibration are relevant to the reliability of earlier models [105]. They developed a modeling approach to help circumvent problems of model non-uniqueness. Their approach is tested on the Upper Mega Aquifer of the Arabian Peninsula and consists of four steps: (i) estimating the discharge amount into the Gulf and the Euphrates originating from residual heads from fossil recharge; (ii) determining the origin of the groundwater flowing into the Gulf and Euphrates by using backward particle tracking in the model; (iii) fitting the hydraulic conductivity by adding the fossil outflow to the recharge and running a pseudo-steady-state calibration in order to fit values of horizontal and vertical hydraulic conductivity for each hydrofacies as part of the fitting of measured to simulated heads; (iv) running a transient simulation from 1950 to 2010 to fit the storage coefficients by adjusting S or Sy to simulate head drawdown induced by pumping with all other parameters from previous steps held constant.

Many models of fossil hydraulic gradients have been developed to test hypotheses of fossil hydraulic gradients and non-equilibrium conditions in groundwater basins. Many of the studies support the existence of modern recharge, which does not rule out the existence of fossil hydraulic gradients on which any modern recharge would be superimposed. The Chilean example of Houston and Hart may provide the most satisfactory abstraction [120]; that even the term fossil hydraulic gradient may not adequately describe the non-equilibrium condition of residual heads where there is no extraction of water. As shown in the smaller groundwater basins of Chile, these residual heads operate over hundreds, not thousands of years of time. The question of the existence of residual hydraulic gradients may operate over a time continuum that is as little as a few hundred years, to something on the order of 15,000 years before quasi-equilibrium might be approached, if an equilibrium state is even possible. Given the superposition of episodic, modern recharge and always changing climate on water levels, it would first seem necessary to first define what is the time scale over which quasi-equilibrium might be reached. In the case of the large periods of time over which fossil hydraulic gradients may exist, this seems to be a most challenging question to answer, given the enormous size of many of the basins to which the question of fossil gradients has been posed. The paucity and fragmentary nature of hydrogeologic data and the lengthy time intervals considered for which critical historical data is lacking are significant challenges to resolving the question of fossil hydraulic gradients in arid basins [121].