Simple Summary

This study assesses the diet and trophic specialization of the short-tailed chinchilla (Chinchilla chinchilla), a critically endangered species from the Chilean Andes. The results show a strong dependence on a single plant resource (Pappostipa frigida), evidencing its vulnerability to changes in high-Andean vegetation and highlighting the need to conserve these grasslands.

Abstract

Understanding trophic ecology is fundamental for the conservation of threatened species with specialist trophic strategies, such as the short-tailed chinchilla (Chinchilla chinchilla), a critically endangered rodent whose diet in the wild is poorly understood. This study presents the first integrated annual characterization of the dietary habits, trophic niche, and resource selection patterns of a high-Andean population. Plant availability was assessed, and dietary composition was analyzed via seasonal microhistological analysis of fecal samples. Diversity (Shannon-Wiener, H′), overlap (Schoener, PS), and resource selection (Manly’s selection index) metrics were calculated. The results indicate a diet of very low diversity (H′ < 0.1), stable throughout the year (PS > 0.99), and dominated (>77%) by grass Pappostipa frigida, with significant positive selection in all seasons. Shrub species, such as Adesmia frigida, were consistently avoided. This high degree of specialization reflects low functional plasticity and highlights the high vulnerability of C. chinchilla to environmental changes and habitat loss, underscoring that the conservation and restoration of P. frigida grasslands are imperative for the species’ survival. Microhistological methodology is confirmed as a key tool for identifying critical trophic relationships and supporting conservation plans based on essential resources.

1. Introduction

Trophic ecology is a fundamental pillar for understanding the autecology of a species and its role within an ecosystem [1]. This understanding is particularly crucial for herbivorous mammals inhabiting environments with limited and highly unpredictable resources, such as high-Andean ecosystems, where detailed knowledge regarding their diet, resource availability, and foraging strategies is essential for developing effective conservation plans [2]. The characterization of trophic parameters allows for the evaluation of a species’ degree of dependence on specific resources and its dietary flexibility in the face of environmental variations [3]. In high-Andean ecosystems, diverse herbivores, including camelids and rodents, present diets dominated by grasses, reflecting a specialized strategy within communities characterized by limited resources and extreme environmental conditions [4,5,6]. The evaluation of parameters such as dietary niche breadth, selectivity, and botanical composition of the diet constitutes an essential tool for understanding these feeding strategies and their relationship with seasonal forage availability [7].

In high-Andean ecosystems, distinct herbivores show trophic adaptations to forage availability and seasonality. The taruka (Hippocamelus antisensis) presents a primarily herbaceous diet, while the guanaco (Lama guanicoe) maintains a generalist consumption with a preference for grasses. In contrast, the Andean viscacha (Lagidium viscacia) exhibits a greater dependence on species of the genus Stipa, evidencing a trend towards specialization in arid high-altitude environments [8,9,10,11].

The short-tailed chinchilla (Chinchilla chinchilla) is a hystricomorph rodent endemic to the Andes, classified as Critically Endangered [12]. Historically, populations suffered a severe reduction due to overexploitation by the fur industry, driving them to the brink of extinction [13]. Currently, its study in natural conditions is limited due to the remote and extreme nature of its habitat—consisting of arid rocky outcrops between 3900 and 4900 m in altitude—as well as its crepuscular and nocturnal habits, which hinder direct observation (Figure 1) [14].

Figure 1.

Individual short-tailed chinchilla (Chinchilla chinchilla) foraging in its natural high-Andean rocky habitat in the Atacama Region, Chile.

Despite its priority status for conservation, knowledge regarding the trophic ecology of C. chinchilla is notoriously fragmented. Most available information on the diet of C. chinchilla is limited primarily to qualitative descriptions of the plant species present in its habitat [15], without quantitative evaluations of composition or food selection. To date, only one study has quantified its diet through microhistological analysis, describing a consumption consisting mainly of grasses of the genus Stipa (currently Pappostipa) and, to a lesser extent, shrubs of the genus Adesmia [16]. However, that work was limited in its temporal scope, leaving a fundamental gap regarding the seasonal dynamics of the diet. It remains unknown whether C. chinchilla maintains a stable feeding regime throughout the year or if it exhibits trophic plasticity to adapt to seasonal variations in resource availability—an uncertainty that contrasts with the better understanding of its congener C. lanigera, for which data on dietary flexibility are available [6]. Furthermore, ecophysiological studies conducted on this species (under the synonym C. brevicaudata) have explicitly documented a reduced basal metabolism and high digestive retention capacity [17], key adaptations for processing fibrous diets in low-productivity environments.

Based on this specific physiological background and previous reports of grass consumption in high-Andean populations [16], it is hypothesized that the diet of C. chinchilla will be determined by a strategy of functional specialization. It is predicted that consumption will be concentrated mostly on the dominant grass resource (Pappostipa frigida) and that this pattern will remain stable seasonally through active selection, discriminating against the use of available shrub resources due to chemical restrictions (secondary metabolites) and physical constraints (e.g., thorns in Adesmia) that would limit energetic efficiency.

In this context, the objective of this study was to quantitatively characterize the trophic ecology of a population of Chinchilla chinchilla over a complete annual cycle in the Atacama region. Specifically, we proposed the following: (1) determine the composition, diversity, and stability of the diet across the four seasons; and (2) quantify resource selection patterns to identify the key plant species that sustain the population. This information is essential for generating an ecological baseline to support the development of evidence-based management and conservation strategies oriented toward this threatened species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

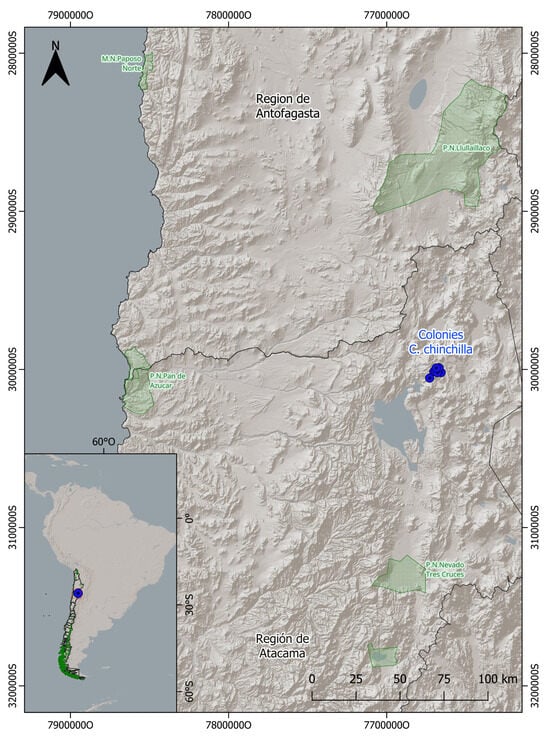

The study was conducted in the Atacama Region, Chañaral Province, in the commune of Diego de Almagro (90 km northeast of the city of the same name), covering an altitudinal range between 3900 and 4700 m a.s.l. (Figure 2). The general study area comprises approximately 1800 hectares and corresponds phytogeographically to the “Desert Steppe of the Andean Salt Flats” formation [18]. Climatically, the zone is classified as High Mountain Tundra, a regime combining desert and polar features characterized by low temperatures throughout the year, with an annual mean of −1.7 °C and a daily thermal oscillation exceeding 15 °C; the temperature difference between extreme months is nearly 10 °C, with a mean of 3.5 °C in January and −6.3 °C in July [19]. Annual precipitation is scarce (<150 mm) and presents a dual seasonal dynamic: snow events occur during the austral winter, while summer rains associated with the “Altiplanic Winter” phenomenon are recorded in summer [20]. The persistence of snow cover seasonally restricts access to trophic resources. In this context, the effective habitat of C. chinchilla is naturally fragmented, restricted to 12 rocky outcrops where the burrows (colonies) identified in this study are located, acting as islands of refuge and resource concentration within the arid matrix.

Figure 2.

Study area in the Andes Mountains of the Atacama Region, northern Chile. Blue dots indicate the location of the 12 burrows (colonies) inhabited by Chinchilla chinchilla where sampling was conducted. These specific sites constitute the patches of effective habitat distributed within the general study matrix of approximately 1800 ha. The red box indicates the location of the enlarged study area shown in the main map. Nearby protected areas are shown in green polygons (P.N. = National Park, M.N. = Natural Monument) along with the site’s location in the context of South America (bottom left inset). Coordinate values correspond to UTM coordinates (meters), with “S” indicating the Southern Hemisphere and “O” indicating West (Oeste).

2.2. Trophic Availability and Diet Analysis

Sampling campaigns were carried out seasonally in Autumn (April 2017), Winter (August 2017), Spring (October 2017), and Summer (February 2018). Trophic resource availability was assessed by estimating seasonal vegetation cover using the point-intercept method [21]. Fifteen transects of 25 m in length were established, distributed proportionally among the studied rocky outcrops and placed randomly within the “feeding zones,” defined as the vegetated area located within a 200 m radius of active rocky shelters (a distance coinciding with the maximum displacement range observed for the species in the area). Cover was recorded every 25 cm, totaling 1500 points per season. Relative plant cover was used as a proxy for environmental availability.

Although fecal samples were successfully collected during all four seasons, direct vegetation measurement via transects was not feasible in winter due to the presence of snow cover. Consequently, winter availability was estimated using late autumn data as a valid biological proxy. This approach is supported by two lines of evidence: first, the phenological dynamics of the Puna indicate the cessation of vegetative growth by mid-May [20]; second, the dominance of Pappostipa frigida (>82% cover), a perennial grass that retains its senescent aerial biomass throughout the winter with minimal structural turnover until spring [18].

For dietary analysis, 12 fresh fecal samples were collected per season. This sample size ( per season) was considered adequate based on methodological reviews indicating that, for major components or low-diversity diets, precision stabilizes with reduced sample sizes [22]. Given the specialist behavior of C. chinchilla, it is assumed that intra-seasonal dietary variability is lower than that of generalist herbivores, allowing for a faster saturation of the species accumulation curve. To ensure statistical independence and avoid pseudoreplication, samples were selected from active burrows located in distinct rocky outcrops or spatially separated by a minimum distance of 200 m, assuming they belonged to different individuals or family groups. Sixty histological slides were prepared per season (5 per sample) following the modified Williams technique [23]. Botanical composition was estimated by analyzing 10 microscopic fields per slide, selected systematically to avoid bias and overlap. Fragments lacking diagnostic epidermal characteristics were categorized as “unidentified fibers.”

2.3. Statistical Analysis

To quantitatively assess the trophic ecology of Chinchilla chinchilla, descriptive analyses of composition, niche, and selection were performed. To guarantee data independence and avoid pseudoreplication, fecal samples ( per season) were collected from latrines or active crevices that were spatially separated (minimum distance m), assuming they belonged to different individuals or family groups within the colony. All calculations and confidence interval estimations were performed using the Python programming language (version 3.11) and the scientific libraries NumPy (version 2.3.5) and Pandas (version 2.2.3) for data matrix manipulation.

2.3.1. Trophic Niche Breadth and Diversity

The diversity of both environmental availability and diet for each season was calculated using the Shannon-Wiener index ():

where is the proportion of item i and S is the total richness of items [1]. To obtain robust estimates and assess statistical uncertainty, 95% confidence intervals (CI) for were generated using the non-parametric bootstrapping method. We performed 1000 iterations using multinomial resampling based on effective sample sizes reflecting the actual sampling effort: simulated observations for vegetation availability (corresponding to total transect points) and for dietary use (corresponding to 60 slides × 10 microscopic fields).

2.3.2. Estimation of Seasonal Trophic Overlap

To compare dietary similarity between different seasons, Schoener’s overlap index () was used [1]:

where and are the proportions of item i in seasons x and y, respectively. A value of was considered biologically significant.

2.3.3. Estimation of Resource Selection

The selectivity of individual food items was determined by calculating Manly’s selection ratio () for Type II designs (individual animals identified, population-level availability) [24]:

where is the proportion of resource i used (in the diet) and is the proportion of resource i available in the environment. For plant species present in the diet but with cover undetected in transects (i.e., relative availability = 0%), a nominal cover value of 1% was assigned to allow for coefficient calculation. To assign statistical significance to selection, 95% confidence intervals were estimated for each value via bootstrapping (1000 iterations) using the Bonferroni inequality. A species was considered positively selected (+) if the confidence interval lay entirely above 1, and negatively selected (−) if it lay entirely below 1.

3. Results

3.1. Resource Availability and Vegetation Cover

Total vegetation cover at the study site averaged 10.3% throughout the year, presenting marked seasonal variation. Absolute values fluctuated between a maximum of 15.18% during spring and a minimum of 1.52% in summer (Table 1). This summer minimum coincides with regional meteorological records for the summer of 2018, which documented an extreme precipitation deficit (0 mm accumulated between January and March at high-mountain reference stations) and temperatures above the historical average, creating a scenario of severe aridity that limited primary productivity [25].

Table 1.

Absolute (A%) and relative (R%) vegetation cover in the study area for each season. Winter cover was estimated using autumn data as a proxy due to snow presence.

Despite this environmental constraint, the structure of the plant community maintained its dominance: Pappostipa frigida invariably constituted more than 82% of the relative availability (proportional supply) across all seasons. In contrast, shrub species (e.g., Adesmia frigida, Fabiana bryoides) represented a minority fraction, with values consistently below 9% of relative cover (Table 1).

3.2. Diet Composition and Trophic Diversity

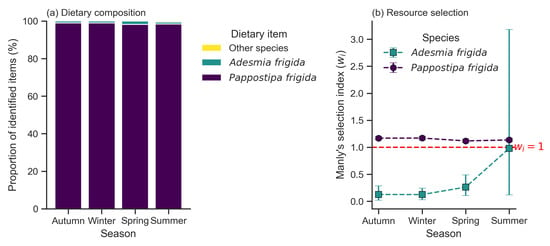

The diet of Chinchilla chinchilla was composed of five plant species. Pappostipa frigida was the principal dietary component in all seasons, with a contribution varying from a minimum of 77.58% in spring to a maximum of 82.36% in summer (Table 2; Figure 3a). Adesmia frigida was the second most consumed item, although its contribution did not exceed 1.44%. Species available in the habitat such as Fabiana bryoides, Senecio rahmeri, and Menonvillea cuneata were not detected in the diet.

Table 2.

Seasonal comparison between relative availability of plant resources (%) and their utilization in the diet of Chinchilla chinchilla (%).

Figure 3.

Trophic ecology of Chinchilla chinchilla across seasons. (a) Proportional dietary composition based on identified plant fragments. Percentages were normalized to 100% of the identified fraction for clarity. Unidentified material (fibers and other fragments) constituted approximately 20% of the total sample volume throughout the seasons and was excluded from this compositional analysis. The diet is consistently dominated by the grass Pappostipa frigida. (b) Resource selection analysis using Manly’s selection ratio () for the two main plant species. Values are shown with their 95% confidence intervals. The dashed line at indicates the threshold between selection and avoidance. P. frigida was consistently selected, while Adesmia frigida was consistently avoided. The wide confidence interval for A. frigida in summer reflects its sporadic and minimal consumption.

Diversity analysis reflected the conditions of an ecosystem with low species richness. The diversity of vegetation availability ( Availability) showed consistently low values, fluctuating between in spring and in summer. Even more notably, dietary diversity ( Diet) was markedly lower, with values ranging between and . This difference between environmental and consumer diversity underscores the high degree of trophic specialization of the species (Table 3).

Table 3.

Trophic diversity and diet overlap indices for Chinchilla chinchilla by season.

3.3. Seasonal Trophic Overlap

The analysis of dietary overlap between seasons yielded high values, with Schoener’s index () exceeding 0.99 in all pairwise comparisons (Table 3). These results indicate that the diet composition of C. chinchilla was practically identical and showed no biologically significant variations throughout the year.

3.4. Resource Selection

Resource selection analysis indicated non-random consumption patterns (Table 4). The main species in the diet, Pappostipa frigida, was consumed in a proportion greater than its availability, showing significant positive selection (+) in all four seasons (Figure 3b).

Table 4.

Resource selection by Chinchilla chinchilla in each season. The table shows the used proportion (), available proportion (), Manly’s selection ratio () with its 95% confidence interval (CI), and the selection result: (+) positive selection, (−) negative selection, (ns) not significant.

For Adesmia frigida, a seasonal pattern was observed: it was significantly avoided (−) during autumn, winter, and spring. In summer, however, its consumption was proportional to its availability, showing no significant selection (ns).

The shrub species Fabiana bryoides and Senecio rahmeri, along with the herbs Menonvillea cuneata, Baccharis tola, and Oxalis pycnophylla, were negatively selected (−). Finally, Cistanthe minuscula was consumed in proportion to its availability during summer, with no significant selection (ns) (Table 4).

4. Discussion

The trophic ecology of Chinchilla chinchilla, a species listed as Critically Endangered, has remained largely unexplored, in marked contrast to the knowledge available for its congener C. lanigera, characterized as a generalist and opportunistic herbivore [6,15,26]. The foraging strategy of C. chinchilla had been inferred primarily from a single quantitative study [16]. Our research provides the first detailed seasonal assessment of the diet and food selection of C. chinchilla in a high-Andean ecosystem, offering robust evidence to characterize its trophic strategy.

The results reveal unequivocal specialist behavior, defined by a diet of very low diversity, stable throughout the year, and based on the positive selection of a single grass, Pappostipa frigida. This dependence highlights the ecological relevance of this plant resource for the rodent’s survival and evidences a specialized strategy in the face of a low-productivity environment.

4.1. Trophic Strategy: A Specialist in a Low-Diversity Environment

This pattern contrasts strongly with C. lanigera, described as generalist and opportunistic [6,15,26], and validates our working hypothesis regarding niche differentiation between the two species, while C. lanigera is restricted to lower-altitude coastal and pre-Andean ranges characterized by milder climates and a diverse and seasonally variable plant supply [13,15], C. chinchilla inhabits a Puna ecosystem where floristic diversity is low and the availability of quality resources is restrictive. This differential environmental pressure likely forced an evolutionary divergence: the heterogeneity of the coastal scrubland favored dietary plasticity in C. lanigera, whereas the homogeneity and harshness of the high-Andean steppe directed C. chinchilla toward specialization in the most predictable and abundant resource (P. frigida), sacrificing niche breadth in exchange for greater efficiency in fiber processing.

Evidence of active and positive selection of P. frigida, rather than passive consumption, reinforces the specialist character of C. chinchilla in this demanding environment. This specialization appears to be sustained by physiological adaptations described for the genus, such as the capacity to process diets high in fiber and low in nutrients [17], which is crucial in high-Andean steppes [2]. This pattern coincides with other high-altitude Andean mammals (e.g., Abrocoma cinerea, Lagidium viscacia) whose diets, dominated by Poaceae and exhibiting low trophic plasticity, have been documented via microhistology [10]. Taken together, the results suggest a shared physiological limitation regarding lignified shrubs, orienting selection toward grasses with high fiber content.

This physiological efficiency is fundamental for interpreting the species’ response to extreme environmental fluctuations. Although the literature describes summer as a season of vegetative growth in the Puna [27], the minimum cover recorded in our study (1.52%) reflects the severe drought conditions that affected the region during the summer of 2018, characterized by a lack of precipitation and heatwaves [25]. Faced with this abiotic restriction preventing green regrowth, the diet of C. chinchilla remained unaltered. This confirms that the species is capable of decoupling itself from phenology, validating a resilient short-term specialization strategy.

However, this obligate functional dependence on a single resource carries inherent risks. Concordantly, recent studies warn that the resilience of specialist mammals is critically linked to the stability of their key trophic resources; therefore, significant or chronic alterations in P. frigida populations could exceed the ecological resilience thresholds of these colonies [28].

4.2. Resource Selection and Foraging Strategy

The constant positive selection of P. frigida establishes this species as a key resource. The avoidance of resources with chemical and physical defenses also influences the strategy: Adesmia frigida was avoided in three seasons, and shrubs such as Fabiana bryoides—whose congeneric species, like F. patagonica, present secondary metabolites with diuretic effects [29]—were not recorded in the diet. The seasonal variation in A. frigida (not significant in summer) could be related to greater leaf biomass during the growing season, reducing the efficacy of physical defenses and allowing incidental consumption. Even rare herbs consumed exclusively in summer (Baccharis tola, Oxalis pycnophylla) showed negative selection, suggesting incidental events rather than active diversification, which reinforces low trophic plasticity.

4.3. Trophic Context and Relationships with Other Herbivores

The documented patterns are consistent with regional work. Tirado et al. [16] reported dominance of Stipa (=Pappostipa) and secondary consumption of Adesmia. This specialization and avoidance of shrubs may reduce competition with other Andean rodents, such as Abrocoma cinerea, a consumer of resinous shrubs [10]. Such interactions are key to understanding the high-Andean community assembly and should be incorporated into conservation strategies.

4.4. Global Perspective and Methodological Approach

Trophic specialization is a frequent strategy in extreme ecosystems but increases vulnerability to environmental changes and loss of key resources [30]. Paleontological evidence indicates that the disappearance of specific food sources has been a determinant in the extinctions of specialists [31].

Methodologically, microhistological analysis is confirmed as a robust and cost-effective tool for cryptic or nocturnal species [7,23,32,33,34], allowing for the contrast of availability and use via indices such as Manly’s, while this technique presents inherent limitations, such as the presence of an unidentified material fraction (ca. 20% in this study), this is attributable to differential digestion and the loss of epidermal characteristics in highly lignified tissues. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that this fraction biases the conclusion of specialization: given the fibrous nature and dominance of P. frigida, it is reasonable to infer that a large part of these fibers corresponds to vascular tissue of this same species that lost its diagnostic features. Even assuming a conservative scenario, the high proportion of P. frigida in the identified fraction ratifies the specialist strategy.

To overcome these resolution limitations in the future, integration with DNA metabarcoding and automated classification (deep learning) offers increased taxonomic precision and efficiency [34,35], a relevant projection for non-invasive monitoring of C. chinchilla.

5. Conclusions

This study concludes that Chinchilla chinchilla, in the high-Andean ecosystem of Atacama, is an herbivore with a markedly specialist trophic strategy, rather than a generalist opportunist. The diet is stable throughout the year, based on positive selection and high dependence on the dominant grass Pappostipa frigida, with systematic avoidance of the available shrub flora.

These findings fill a fundamental gap in the autecology of this critically endangered species, providing the first quantitative evidence of its seasonal trophic niche and feeding behavior. The unique dependence on P. frigida makes the viability of populations inseparable from the conservation of these grasslands; protecting the plant resource is as essential as safeguarding the colonies.

Furthermore, this case illustrates the need for detailed studies and robust methodologies to move from generalist approaches to specific, evidence-based plans. In line with global evidence, reliance on few food resources is associated with a higher extinction risk in mammals [28,31]; specialization reduces resilience to environmental alteration [36]. Finally, these results acquire critical relevance in the face of climate change scenarios projecting increased aridification in the Puna. The obligate dependence of C. chinchilla on P. frigida suggests that monitoring the health of these tussock grasslands may serve as an early warning indicator for population viability, anticipating potential local collapses in the face of the degradation of its single key resource. Integrating trophic indicators into risk assessments and conservation planning is, therefore, a priority.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.C. and A.C.; methodology, J.P.C.; software, J.P.C.; validation, J.P.C., A.C. and F.N.; formal analysis, J.P.C.; investigation, J.P.C.; resources, F.N.; data curation, J.P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.C.; writing—review and editing, J.P.C., A.C. and F.N.; visualization, J.P.C.; supervision, A.C.; project administration, F.N.; funding acquisition, F.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Gold Fields Salares Norte SpA through the project executed by the Centro de Ecología Aplicada (CEA), Code: MGF046.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to it being conducted exclusively with fecal samples collected in the field, with no capture or manipulation of live animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technical staff of the Centro de Ecología Aplicada (CEA) for their support during the fieldwork, and Eduardo Miranda for his assistance in laboratory activities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from Gold Fields Salares Norte SpA. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Krebs, C.J. Ecological Methodology, 2nd ed.; Benjamin/Cummings: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, I.J.; Prins, H.H.T. The Ecology of Browsing and Grazing II; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facultad de Agronomía y Zootecnia, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán. Hábitos Dietarios de herbíVoros: Parámetros tróFicos, Selectividad y Amplitud del Nicho. Technical Report, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, 2025. Documento Institucional. Available online: https://faz.unt.edu.ar/idehost/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/SD-92-FAZ-UNT-Habitos-dietariosMarcadores.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Borgnia, M.; Vilá, B.L.; Cassini, M.H. Foraging ecology of Vicuña, Vicugna vicugna, in dry Puna of Argentina. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 88, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, P.; Mühlenberg, M. Composición botánica de las dietas de alpacas (Lama pacos) y llamas (Lama glama) en pastizales altoandinos de Chile. In Proceedings of the Tropentag 1999: Degradation and Rehabilitation of Agricultural Landscapes, Göttingen, Germany, 14–15 October 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, A.; Miranda, E.; Jiménez, J.E. Seasonal food habits of the endangered long-tailed chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera): The effect of precipitation. Mamm. Biol. 2002, 67, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holechek, J.L. Sample preparation techniques for microhistological analysis. J. Range Manag. 1982, 35, 267–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellaro, G.L.; Orellana, C.L.; Escanilla, J.P.; Fuentes-Allende, N.; González, B.A. Preliminary Report on Diet Estimation of Taruka (Hippocamelus antisensis d’Orbigny, 1834) in an Agricultural Area of the Andean Foothills of the Tarapacá Region, Chile. Animals 2024, 14, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, S.; Videla, F.; Méndez, E.; Cona, M. Summer and winter diet of the guanaco and food availability for a high Andean migratory population. Mamm. Biol. 2011, 76, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, A.; Rau, J.R.; Miranda, E.; Jiménez, J.E. Food-habits of Lagidium viscacia and Abrocoma cinerea: Syntopic rodents in high Andean environments of northern Chile. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2002, 75, 583–593. [Google Scholar]

- Puig, S.; Rosi, M.I.; Videla, F.; Seitz, V.P. Diet selection and habitat use by the mountain vizcacha (Lagidium viscacia) in the Southern Andean Precordillera (Argentina). Mammalia 2020, 84, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. Decreto Supremo N°13, Clasifica Especies Según Estado de Conservación, Noveno Proceso; Gobierno de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, J.E. The extirpation and current status of wild chinchillas Chinchilla lanigera and C. brevicaudata. Biol. Conserv. 1996, 77, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, S.M.; Barahona, P.P.; Ávila, J.M. Análisis de nuevos registros de la chinchilla de cola corta (Chinchilla chinchilla, Lichtenstein, 1829) en la Región de Atacama, Chile. Boletín Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. 2019, 68, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Valladares, P.; Spotorno, A.; Zuleta, C. Natural history of the Chinchilla genus (Bennett 1829). Considerations of their ecology, taxonomy and conservation status. Gayana 2014, 78, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado, C.; Cortés, A.; Miranda-Urbina, E.; Carretero, M.A. Trophic preference in an assemblage of mammal herbivores from Andean Puna (Northern Chile). J. Arid Environ. 2012, 79, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, A.; Tirado, C.; Rosenmann, M. Energy metabolism and thermoregulation in Chinchilla brevicaudata. J. Therm. Biol. 2003, 28, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajardo, R. La VegetacióN Natural de Chile: Clasificación y DistribucióN GeográFica; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Juliá, C.; Montecinos, S.; Maldonado, A. Características Climáticas de la Región de Atacama. In Libro Rojo de la Flora Nativa y de los Sitios Prioritarios Para su Conservación: Región de Atacama; Ediciones Universidad de La Serena: La Serena, Chile, 2008; pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez, R.O.; Christie, D.A.; Olea, M.; Anderson, T.G. A Multiscale Productivity Assessment of High Andean Peatlands across the Chilean Altiplano Using 31 Years of Landsat Imagery. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Dombois, D.; Ellenberg, H. Aims and Methods of Vegetation Ecology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Holechek, J.L.; Vavra, M.; Pieper, R.D. Botanical composition determination of range herbivore diets: A review. J. Range Manag. 1982, 35, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, O. A technique for studying microtine food habits. J. Mammal. 1962, 43, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manly, B.; McDonald, L.; Thomas, D.; McDonald, T.; Erickson, W. Resource Selection by Animals: Statistical Design and Analysis for Field Studies, 2nd ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Reporte Anual de la Evolución del Clima en Chile 2018; Technical Report; Dirección Meteorológica de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Naranjo, V.; Zuleta, C. Selección de recursos en colonias de Chinchilla lanigera (Rodentia: Chinchillidae) en la Reserva Nacional Las Chinchillas, Chile. Gayana 2023, 87, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarancca, R. Evaluación Fenológica de Especies Forrajeras Altoandinas. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional de San Cristóbal de Huamanga, Ayacucho, Peru, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Morelli, F.; Hanson, J.O.; Benedetti, Y. Human pressures threaten diet-specialized mammal communities. Proc. R. Soc. B 2025, 292, 20241735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.E.; Maria, A.O.; Saad, J.R. Diuretic activity of Fabiana patagonica in rats. Phytother. Res. 2002, 16, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colles, A.; Liow, L.H.; Prinzing, A. Are specialists at risk under environmental change? Neoecological, paleoecological and phylogenetic approaches. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 849–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.E.; Purvis, A.; MacLarnon, A. Dietary specialization and extinction risk in primates: A paleontological perspective. Paleobiology 2009, 35, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, L. Methods of morphological diet micro-analysis in rodents. Oikos 1970, 21, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Wofford, H.; Pearson, H. Microhistological Techniques for Food Habits Analyses; Technical Report; USDA Forest Service: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Espunyes, J.; Espunya, C.; Chaves, S.; Calleja, J.A.; Bartolomé, J.; Serrano, E. Comparing the accuracy of PCR-capillary electrophoresis and cuticle microhistological analysis for assessing diet composition in ungulates: A case study with Pyrenean chamois. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Khattak, R.H.; Han, X.; Sun, J.; Li, Z.; Lang, J.; Chen, C.; Jin, J.; et al. Dietary patterns of water deer recently rediscovered in Northeast China show high similarity to those in other regions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.D.; Hamilton, M.J.; Boyer, A.G.; Brown, J.H.; Ceballos, G. Multiple ecological pathways to extinction in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 10702–10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.