Simple Summary

This systematic review reveals that the prevalences of Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon in Southeast Asia are 21% (95% CI: 18–25%), 18% (95% CI: 15–22%) and 34% (95% CI: 30–37%), respectively. Additionally, this review reveals 23 lineages of Plasmodium, 35 lineages of Haemoproteus and 21 lineages of Leucocytozoon identified in avian species throughout Southeast Asia. These findings indicate that monitoring of these parasites in domestic poultry and wild birds should be implemented. Furthermore, the high genetic diversity suggests the existence of undescribed species. Thus, further experimental studies applying combined microscopic and molecular techniques may reveal overlooked parasites.

Abstract

In this study, for the first time, a systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to understand the prevalence and genetic diversity of haemosporidian parasites—namely, Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon—in avian species in Southeast Asia. Following the PRISMA guidelines, 14,211 studies were retrieved from PubMed, ScienceDirect and Scopus, which contain data relevant to ‘Plasmodium’ or ‘Haemoproteus’ or ‘Leucocytozoon’ and ‘birds’ or ‘chickens’. Of these, 15 articles reporting the prevalence of Plasmodium, Haemoproteus or Leucocytozoon in Southeast Asia were selected for meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon were analyzed using a meta-analysis of their proportions, implemented in R programming. The publication bias was checked using a funnel plot and Egger’s test. Consequently, the pooled prevalences of Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon in Southeast Asia were found to be 21% (95% CI: 18–25%), 18% (95% CI: 15–22%) and 34% (95% CI: 30–37%), respectively. The prevalence of Plasmodium in domestic poultry (37.94%) was found significantly higher than in wild birds (6.46%). There was substantial heterogeneity among studies related to Plasmodium (χ2 = 171.50, p < 0.0001, I2 = 94.84%), Haemoproteus (χ2 = 52.20, p < 0.0001, I2 = 90.4%) and Leucocytozoon (χ2 = 433.90, p < 0.0001, I2 = 98.80%). Additionally, this review revealed 23 lineages of Plasmodium, 35 lineages of Haemoproteus and 21 lineages of Leucocytozoon reported from both domestic poultry and wild birds in Southeast Asia. In conclusion, this systematic review suggested that the prevalence of avian haemosporidian parasites in Southeast Asia is high. Particularly, domestic poultry has a high prevalence of Plasmodium, suggesting that monitoring of this parasite should be implemented in the poultry production system. Furthermore, several parasites found in wild birds are undescribed species. Further experimental studies using combined microscopic and molecular techniques might reveal the characteristics of overlooked parasites.

1. Introduction

Haemosporidian parasites are a group of vector-borne parasites belonging to the order Haemosporida, which are classified into four families: Haemoproteidae (Haemoproteus), Plasmodiidae (Plasmodium), Leucocytozoidae (Leucocytozoon) and Garniidae (Fallisia) [1,2]. During the first half of the 20th century, the term ‘malaria parasites’ was used broadly for all haemosporidian parasites, but later, the term was dropped because of the differences in basic biological characteristics among these parasites [3]. More recently, the term ‘malaria parasites’ has been restricted to the haemosporidian parasites belonging to the genus Plasmodium. Diseases caused by Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon are named malaria, haemoproteosis and leucocytozoonosis, respectively [3]. The vectors of these parasites are as follows: Culex, Aedes and Culiseta mosquitoes for Plasmodium, biting midges and hippoboscids for Haemoproteus, and simuliids for Leucocytozoon [1]. However, one species of Leucocytozoon (Leucocytozoon caulleryi) can also be transmitted by biting midges.

Recently, 55 morphospecies of Plasmodium, 177 morphospecies of Haemoproteus and 45 morphospecies of Leucocytozoon have been described in birds [4,5,6]. Furthermore, PCR-based techniques [7,8] amplifying the fragment cytochrome b gene of these parasites showed huge genetic diversity, comprising ~5131 described lineages deposited in a haemosporidian-specific public database (the MalAvi database, accessed on November 2024) [9]. Some of haemosporidian parasites, such as Plasmodium elongatum [10], Plasmodium gallinaceum [11], Plasmodium homocircumflexum [12], Plasmodium relictum [13], Haemoproteus minitus [14] and L. caulleryi [15], can cause severe diseases in non-adapted hosts. Generally, Plasmodium can rupture the red blood cells of birds, resulting in anemia, weakness and eventually death [16]. Additionally, the development of the exo-erythrocytic stage in the brain can cause cerebral capillary blockage, resulting in ischemia [17,18]. Furthermore, infected birds can die because of hypoxemia, secondary to the severe pulmonary pathology [19]. Haemoproteus infection may lead to the damage of internal organs caused by the development of the exo-erythrocytic megalomeront stage [14]. Megalomeronts of Haemoproteus might also induce myositis in an infected host [20]. In the case of Leucocytozoon, the parasite can cause lethal hemorrhagic disease [21], anemia, anorexia, lethargy, green dropping and decreased egg production [1].

The prevalence and transmission of haemosporidian parasites among birds were reported in Southeast Asia [22], suggesting concerns in poultry production and wild bird conservation. Previously, a systematic review and meta-analysis of the global prevalence of Plasmodium infection in wild birds was published [16]. However, this study only included avian Plasmodium in Indonesia [23], thus lacking information from other countries in Southeast Asia. To fill the gap, a systematic review and meta-analysis were performed in this study to estimate the molecular prevalence of avian Plasmodium and other haemosporidian parasites in Southeast Asia, considering geographical locations, avian host species and their heterogeneity. This study provides novel information about the prevalence of Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon in Southeast Asia. Furthermore, this review reveals the genetic diversity of Plasmodium and other haemosporidian parasites, providing baseline information for future experimental studies and the development of preventive measures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol, Literature Search and Screening

The systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines [24]. The review protocol has been registered in the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ZS9UW). All published articles that reported the prevalence of avian haemosporidians (Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon) were retrieved from three bibliographic databases, namely PubMed, ScienceDirect and Scopus. The search string was used as follows: (“Plasmodium” OR “Leucocytozoon” OR “Haemoproteus” OR “blood parasites”) AND (“bird” OR “chicken”). The papers published until 31 October 2024 were included. Title and abstract screening were performed independently by three reviewers (K.S., N.SR. and N.SO.).

2.2. Article Selection and Quality Assessment

Papers were selected for the systematic review if they met the predefined inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) study performed in any avian species; (ii) cross-sectional study; (iii) locations within Southeast Asia; (iv) sample size of greater than 25; (v) study that used PCR-based detection method; and (vi) exact total and positive number (or prevalence with 95% confidence interval) were provided. Studies that reported Plasmodium sp., Haemoproteus sp. or Leucocytozoon sp. in non-avian species, case reports, and review articles were excluded.

The quality of selected studies was evaluated using the Quality Assessment Scale applied from the previously published report [25]. Studies were grouped into two groups: low (0–8 scores) and high quality (9–14 scores). The full-text assessment, article selection and quality assessment were independently performed by two reviewers (P.P. and C.J.S.). Disputes were resolved by discussion.

2.3. Data Extraction

Two reviewers (P.P. and T.M.) investigated the included papers thoroughly for data extraction. The extracted data included (i) study characteristics: the authors and year of publication; (ii) study methodology: sampling area, period of study, method used for parasites detection, sample size and number of positive samples; (iii) species and order of birds; and (iv) parasite species.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables (number of total birds and number of birds infected with Plasmodium spp., Leucocytozoon spp. and Haemoproteus spp.) were pooled and analyzed. The available prevalence data of each parasite with a minimum of three articles were pooled and considered for meta-analysis, which included pooled prevalence of Plasmodium and Leucocytozoon in both wild birds and domestic poultry as well as pooled prevalence of Haemoproteus in wild birds. Meta-analysis of proportion (fixed effect model) was implemented in R (version 4.3.3) [26], following the previously reported guidelines [27]. I2 and Q tests were used to evaluate the heterogeneity among the included studies (p ≥ 0.10 or I2 < 50% indicated low statistical heterogeneity, whereas p ≤ 0.10 or I2 > 50% indicated high statistical heterogeneity) [28]. The results of meta-analysis were visualized by using forest plots. Meta-regression was used to identify any significant differences in the prevalence of Plasmodium and Haemoproteus between regions (mainland and maritime) and host species (domestic poultry and wild birds). Publication bias was assessed in meta-analysis that contained ≥ 10 studies using funnel plots and Egger’s regression test. The funnel plots and Egger’s regression test were performed in R [26] using ‘meta’ (version 8.0-1) and ‘metafor’ (version 4.6-0) packages.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies (Table 1)

Initially, a total of 14,211 articles were retrieved from the search databases. After deduplication, 446 articles were removed (Figure 1). Subsequently, 13,741 articles that did not meet the selection criteria were excluded based on the screening of titles and abstracts. Full texts of a total of twenty-four articles were investigated for eligibility and ten articles were excluded for the following reasons: one article did not focus on the prevalence of avian haemosporidian parasites [29], two articles provided insufficient data [30,31], three articles did not use the molecular detection methods [32,33,34], two articles shared a dataset with other studies [35,36], one article had a sample size lower than 25 [37] and one article was conducted outside of Southeast Asia [38].

Figure 1.

Flowchart for study selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Region | Period of Study | PCR-Based Detection Method | Information of Birds | Information of Parasites | Positive Cases | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boonchuay et al. [39] | 2023 | Thailand | Mainland | 2021–2022 | HaemF-HaemR2 | Galliformes | P. gallinaceum | 7 | 57 |

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Galliformes | P. juxtanucleare | 5 | 57 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Galliformes | Plasmodium sp. | 25 | 57 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Galliformes | L. schoutedeni | 6 | 57 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Galliformes | Leucocytozoon sp. | 45 | 57 | |||||

| Chatan et al. [40] | 2024 | Thailand | Mainland | 2022 | HaemF-HaemR2 | Galliformes | P. gallinaceum | 4 | 36 |

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Galliformes | P. juxtanucleare | 1 | 36 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Galliformes | Plasmodium sp. | 20 | 36 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Anseriformes | Plasmodium sp. | 12 | 80 | |||||

| Dhamayanti et al. [41] | 2023 | Indonesia | Maritime | 2022 | HaemOF-HaemOR | Galliformes | P. juxtanucleare | 21 | 60 |

| Ivanova et al. [42] | 2010 | Malaysia | Maritime | 2010 | HaemF-HaemR2 | Coraciiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 9 |

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Coraciiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 1 | 9 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Apodiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 1 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Apodiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 1 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Columbiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 3 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Columbiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 1 | 3 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Passeriformes | Plasmodium sp. | 4 | 62 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Passeriformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 16 | 62 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Piciformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 4 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Piciformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 1 | 4 | |||||

| Khumpim et al. [35] | 2021 | Thailand | Mainland | 2019–2020 | LsF2-LsR2 | Galliformes | L. sabrazesi | 252 | 313 |

| Lertwatcharasarakul et al. [43] | 2021 | Thailand | Mainland | 2012–2019 | HaemFL-HaemR2L | Accipitriformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 3 | 198 |

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Strigiformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 5 | 202 | |||||

| Muriel et al. [44] | 2021 | Myanmar | Mainland | 2019 | HaemF-HaemR2 | Passeriformes | Plasmodium sp. | 3 | 120 |

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Passeriformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 8 | 120 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Passeriformes | Haems/Plas * | 1 | 120 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Pelecaniformes | Plasmodium sp. | 1 | 1 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Pelecaniformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 1 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Coraciiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 4 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Coraciiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 2 | 4 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Cuculiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 1 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Cuculiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 1 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Columbiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 1 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Columbiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Noni and Tan [45] | 2023 | Malaysia | Maritime | 2021 | AE983-AE985 | Passeriformes | Plasmodium sp. | 14 | 29 |

| Piratae et al. [46] | 2021 | Thailand | Mainland | 2020 | HaemFL-HaemR2L | Galliformes | L. schoutedeni | 5 | 250 |

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Galliformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 45 | 250 | |||||

| Pornpanom et al. [22] | 2019 | Thailand | Mainland | 2012–2018 | HaemF-HaemR2 | Strigiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 15 | 167 |

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Strigiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 41 | 167 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Strigiformes | Haem/Plas | 1 | 167 | |||||

| Pornpanom et al. [47] | 2021 | Thailand | Mainland | 2013–2019 | HaemF-HaemR2 | Accipitriformes | Plasmodium sp. | 5 | 198 |

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Accipitriformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 8 | 198 | |||||

| Prompiram et al. [48] | 2023 | Thailand | Mainland | 2018–2019 | HaemF-HaemR2 | Columbiformes | H. columbae | 24 | 87 |

| Subaneg et al. [49] | 2024 | Thailand | Mainland | 2020–2022 | HaemF-HaemR2 | Accipitriformes | Plasmodium sp. | 3 | 78 |

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Strigiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 1 | 31 | |||||

| Win et al. [50] | 2020 | Myanmar | Mainland | 2017–2020 | HaemFL-HaemR2L | Galliformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 81 | 461 |

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Galliformes | Haem/Plas | 158 | 461 | |||||

| Yuda [23] | 2019 | Indonesia | Maritime | 2009 | HaemF-HaemR2 | Pelecaniformes | Plasmodium sp. | 3 | 3 |

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Pelecaniformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 3 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Pelecaniformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 0 | 3 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Charadriiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 3 | 40 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Charadriiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 40 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Charadriiformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 1 | 40 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Columbiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 3 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Columbiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 3 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Columbiformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 0 | 3 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Cuculiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 5 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Cuculiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 1 | 5 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Cuculiformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 0 | 5 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Caprimulgiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 11 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Caprimulgiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 11 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Caprimulgiformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 0 | 11 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Apodiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 14 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Apodiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 14 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Apodiformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 0 | 14 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Coraciiformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 2 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Coraciiformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 2 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Coraciiformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 0 | ||||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Passerinformes | Plasmodium sp. | 1 | 34 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Passerinformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 1 | 34 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Passerinformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 1 | 34 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Galliformes | Plasmodium sp. | 0 | 10 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Galliformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 10 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Galliformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 0 | 10 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Aneriformes | Plasmodium sp. | 1 | 10 | |||||

| HaemF-HaemR2 | Aneriformes | Haemoproteus sp. | 0 | 10 | |||||

| HaemFL-HaemR2L | Aneriformes | Lecucocytozoon sp. | 0 | 10 |

* Haems/Plas = Haemoproteus or Plasmodium.

Fifteen cross-sectional articles were included in the final qualitative and quantitative analysis. All the characteristics of the included articles are shown in Table 1. Among the fourteen included articles, six articles reported haemosporidian parasites in domestic poultry [35,39,40,41,46,50], eight articles reported haemosporidian parasites in wild birds [22,42,43,44,45,47,48,49] and one article reported haemosporidian parasites in both domestic poultry and wild birds [23]. Likewise, Plasmodium sp. was reported in ten articles on both domestic poultry and wild birds [22,23,39,40,41,42,44,45,47,49]. Haemoproteus sp. was reported in six articles on only wild birds [22,23,42,44,47,48]. Leucocytozoon sp. was reported in six articles on both domestic poultry and wild birds [23,35,39,43,46,50].

Out of the fifteen included articles, two were from Indonesia [23,41], Malaysia [42,45], Myanmar [44,50] each, and nine were from Thailand [22,35,39,40,43,46,47,48,49]. The quality assessment showed that all 15 articles were of high quality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included studies applied from Zhou et al. (2022) [25].

3.2. The Crude Prevalence of Haemosporidian Parasites in Southeast Asia

All 15 included articles investigated a total of 2498 birds. Plasmodium spp. were found in 149 birds. With regard to Plasmodium species, Plasmodium gallinaceum was found in seven domestic chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) and four turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo). Plasmodium juxtanucleare was found in twenty-six domestic chickens and one turkey. Plasmodium sp. was found in 58 domestic poultry and 53 wild birds (Accipitriformes, Charadriiformes, Passeriformes, Palecaniformes and Strigiformes). Haemoproteus spp. were found in 81 wild birds (Accipitriformes, Columbiformes, Coraciiformes, Cuculiformes, Passeriformes, Piciformes and Strigiformes). With regard to Haemoproteus species, Haemoproteus columbae was found in 24 pigeons (Columba liva). Likewise, Leucocytozoon spp. were found in 444 birds. Among Leucocytozoon species, Leucocytozoon sabrazesi was reported in 252 domestic chickens. Leucocytozoon schoutedeni was found in eleven domestic chickens. Leucocytozoon sp. was found in 171 domestic chickens and 10 wild birds (Accipitriformes, Charadriiformes, Passeriformes and Strigiformes).

The highest prevalence of Plasmodium sp. (64.91%) was reported by Boonchuay et al. (2023) [39], while Pornpanom et al. (2021) [47] reported the lowest prevalence at 2.53%. Likewise, the highest prevalence of Haemoproteus sp. was reported to be 27.59% in the study conducted by Prompiram et al. (2019) [48]. The lowest prevalence of Haemoproteus sp. was 1.79% in the study conducted by Yuda (2019) [23]. The prevalence of Leucocytozoon spp. was in the range of 89.47% [39] to 1.52% [23].

3.3. Genetic Diversity of Haemosporidian Parasites in Southeast Asia

In total, nine articles [22,39,40,42,43,44,45,47,48] reported the lineage of haemosporidian parasites following the MalAvi database (Table 3). The pooled data revealed that only one lineage of Plasmodium gallinaceum (GALLUS01) and one lineage of Plasmodium juxtanucleare (GALLUS02) were found in domestic chickens in Southeast Asia. However, there are six other lineages of Plasmodium sp. that were found to infect domestic poultry. In wild birds, 15 lineages were reported from four orders of avian species (Accipitriformes, Passeriformes, Pelecaniformes and Strigiformes).

Table 3.

Summary of avian haemosporidian lineages found in Southeast Asia.

In the case of Haemoproteus sp., 35 lineages were isolated and described from wild birds belonging to six orders (Accipitriformes, Coraciiformes, Columbiformes, Passeriformes, Piciformes and Strigiformes). Sixteen lineages of Leucocytozoon sp. were isolated and described from domestic chickens and five lineages were isolated and described from two orders of wild birds (Accipitriformes and Strigiformes). Furthermore, some lineages including ACCBAD01, ORW1 and FANTAIL01 were found in both domestic poultry and wild birds.

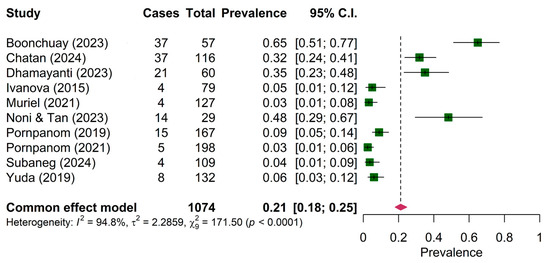

3.4. The Pooled Prevalence Estimate of Haemosporidian Parasites in Southeast Asia

The pooled prevalence of Plasmodium sp. in both wild birds and domestic poultry was comparable among ten articles (21.00%, 95% CI: 18.00–25.00%) (Figure 2). The prevalence of Plasmodium sp. between mainland (14.33%, 95% CI: 11.55–17.12%) and maritime (12.18%, 95% CI: 8.28–16.07%) was not significantly different (Table 4). However, the prevalence of Plasmodium sp. among wild birds (4.77%, 95% CI: 4.77–8.17%) was significantly different from domestic poultry (37.94%, 95% CI: 37.97–43.92%).

Figure 2.

Pooled prevalence of Plasmodium in wild birds and domestic poultry [22,23,39,40,41,42,44,45,47,49].

Table 4.

Pooled prevalence, heterogeneity and meta-regression in Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon infection in Southeast Asia.

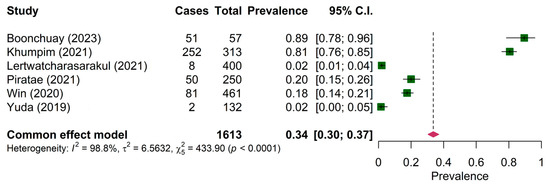

The prevalence of Haemoproteus sp. was reported in six papers on wild birds only. The pooled prevalence of Haemoproteus sp. was 18.00% (95% CI: 15.00–22.00%) (Figure 3). The prevalence of Haemoproteus sp. in the mainland region (19.89%, 95% CI: 16.23–24.14%) was significantly different from the maritime region (10.99, 95% CI: 6.56–15.43%) (Table 4). The pooled prevalence of Leucocytozoon sp. in both wild birds and domestic poultry was comparable among the six articles (34.00%, 95% CI: 30.00–37.00%) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Pooled prevalence of Haemoproteus in wild birds [22,23,42,44,47,48].

Figure 4.

Pooled prevalence of Leucocytozoon in wild birds and poultry [23,35,39,43,46,50].

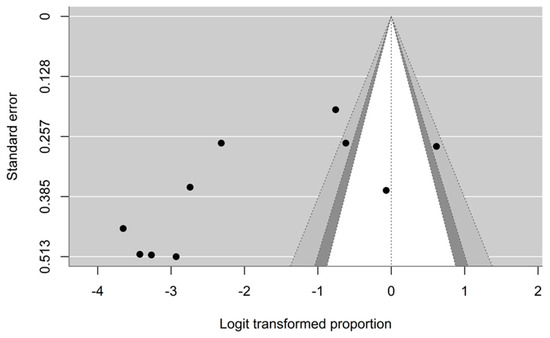

3.5. Publication Bias

The funnel plot (Figure 5) showed publication bias, which was confirmed by Egger’s test (the regression coefficient = -0.0813, 95% CI: −0.1420–−0.0205, p = 0.003). The funnel plot analysis and Egger’s test were not performed for the studies on Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon because the analysis required a minimum of 10 studies.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot for prevalence of avian Plasmodium in Southeast Asia.

4. Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis conducted to demonstrate the pooled prevalence estimates of Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon infection in wild birds and domestic poultry in Southeast Asia. The results showed that the pooled prevalences of Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon were 21%, 18% and 34%, respectively. Southeast Asia has mostly hot and humid tropical climatic zones that might be suitable for the existence of both haemosporidian parasites and their vectors. Previously, it was shown that temperatures above 12 °C and 20 °C were suitable for the completion of sporogony development of Plasmodium sp. and Haemoproteus sp., respectively [51,52]. Likewise, temperatures above 22 °C allow the complete sporogony development of Leucocytozoon sp. [53]. Furthermore, other environmental factors such as high rainfall might also promote the abundance of vectors [35]. Additionally, wild birds and domestic poultry raised in open fields are exposed to blood-sucking insects that are known to transmit blood parasites such as Plasmodium sp., Haemoproteus sp. and Leucocytozoon sp. On the other hand, infected birds that are raised in indoor conditions or in open fields might also shed these parasites, resulting in the further spread of parasites. As a partial remedy, recently, swiftlet houses were designed in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand that imitated the environment of natural caves [54]. In Thailand, income generated by selling such swiftlet nests was estimated to be USD 66–100 million per year [54]. However, the occurrence of infectious diseases, including blood parasites in swiftlets (Aerodramus germani) might affect the economy as well.

It was observed that the prevalence of Plasmodium was significantly higher in domestic poultry than in wild birds (Table 4). This might be related to the biology of infected birds, such as hunting activity and defensive behaviors (foot stomping, head and wing movement and tail shaking) [22,49,55]. Interestingly, some Plasmodium-infected birds were migratory birds, such as the Cinerous Vulture (Aegypius monachus) and Himalayan Vulture (Gyps himalayansis) [47,49]. Himalayan Vultures normally reside in the Himalayas from Northern Pakistan to Bhutan, Southern and Eastern Tibet and China [56]. During winter, juveniles might migrate to other South Asian countries [56]. Consequently, there were records of Himalayan Vultures in countries, such as Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand and Singapore [57]. This migratory pattern of infected birds could play a role in introducing Plasmodium sp. in non-adaptive birds from a new environment, which might lead to clinical signs in naïve birds. Furthermore, the East Asia Flyway of migratory birds lies in Southeast Asia, which connects Northern, Eastern Asia and insular Southeast Asia [58]. Thus, there exists a possibility of Plasmodium infection and transmission in several migratory and native birds. Proper implementation of disease monitoring systems is crucial to prevent the spread of the parasite.

A study on Haemoproteus was conducted in only four countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand) (Table 1). Furthermore, several lineages were reported from non-described species (Table 3). This was evidence of the existence of a number of overlooked parasites. Thus, it is worth conducting further investigation using combined microscopic and molecular techniques to identify the prevalence of Haemoproteus in birds in Southeast Asia. This will reveal the existence of undescribed species, if any. In the case of Leucocytozoon, the prevalence of the parasite was very high in domestic poultry (Table 4). Parasite species that are known for their low pathogenicity such as Leucocytozoon sabrazesi and Leucocytozoon schoutedeni were reported. However, there was a report on the pathology and molecular characteristics of a lethal parasite (Leucocytozoon caulleryi) in Thailand [21]. Although L. sabrazesi and L. schoutedeni might not be pathogenic, they can still cause anemia, greenish droppings, slight emaciation and reduced egg production [1,59]. Altogether, the infection of birds with these parasites should not be neglected, especially in large commercial poultry production systems.

The present systematic review and meta-analysis have some limitations. Firstly, the heterogeneity among the included studies was high (I2 = 94.81%, 90.4% and 98.8% for the study on Plasmodium (Figure 2), Haemoproteus (Figure 3) and Leucocytozoon (Figure 4), respectively). Heterogeneity might occur due to the varied characteristics of samples or avian species. This was supported by the regression analysis that revealed the significant difference between the prevalence of Plasmodium in wild birds and domestic poultry. Second, the funnel plot and Egger’s test showed publication bias. Thus, this pooled prevalence might be influenced by some small-scale studies. Nevertheless, the prevalence of haemosporidian parasites in Southeast Asia was high, and there were a number of genetic diversities of undescribed species of haemosporidian parasites. In the future, combined microscopic and molecular studies are deemed necessary to explore the actual status of the parasite prevalence. PCR-based (molecular) techniques allow us to understand the genetic characteristics of parasites, which could be used for phylogenetic analysis and the description of lineages following the haemosporidian-specific public database, the MalAvi [9]. However, the microscopy technique was reported as an inexpensive method that can provide an opportunity to determine the identity and intensity of infection [60]. Additionally, the description of parasite morphospecies mainly relied on morphologic characteristics [1,4,5]. Thus, using combined methods might allow the identification of the species, genetic diversity, phylogeny and epidemiology of haemosporidian parasites.

5. Conclusions

The prevalence of haemosporidian parasites, including Plasmodium (21%), Haemoproteus (18%) and Leucocytozoon (34%) was found to be high in Southeast Asia. Generally, domestic poultry has a higher prevalence of Plasmodium than wild birds, demanding continuous monitoring of these parasites in poultry production systems. There were several parasitic lineages of undescribed parasite species found in wild birds, which indicated the existence of overlooked parasites. Further experimental studies using combined microscopic and molecular techniques may reveal such overlooked parasites. Comprehensive knowledge about parasites will help understand host–parasite interactions, pathology and the development of treatment and prevention strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ani15050636/s1, PRISMA 2020 checklist. Reference [61] is cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: K.S., N.S. (Nikom Srikacha), S.P., T.M. and P.P.; methodology: K.S., N.S. (Nikom Srikacha), T.M. and P.P.; investigation: K.S, N.S. (Nikom Srikacha), N.S. (Nittakone Soulinthone), W.S., C.J.S., T.M. and P.P.; Visualization: K.S., N.S. (Nikom Srikacha) and P.P.; formal analysis: P.P.; data curation: P.P.; writing—original draft preparation: K.S.; writing—review and editing: N.S. (Nikom Srikacha), N.S. (Nittakone Soulinthone), S.P., W.S., C.J.S. and P.P.; funding acquisition: N.S. (Nikom Srikacha), N.S. (Nittakone Soulinthone), W.S., C.J.S. and P.P.; project administration: P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Walailak University under the New Researcher Development scheme (Contract Number WU67211), the international research collaboration scheme (WU-CIA-04507/2024) and the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT, Contract Number N42A670081).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Akkhraratchakumari Veterinary College, Walailak University, for arranging the “systematic review article workshop”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Valkiūnas, G. Avian Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporidia; CRC Press: Boca Roton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Minichová, L.; Slobodník, V.; Slobodník, R.; Olekšák, M.; Hamšíková, Z.; Škultéty, L.; Špitalská, E. Detection of avian haemosporidian parasites in wild birds in Slovakia. Diversity 2024, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Anwar, A.M.; Atkinson, C.T.; Greiner, E.C.; Paperna, I.; Peirce, M.A. What distinguishes malaria parasites from other pigmented haemosporidians? Trends Parasitol. 2005, 21, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Iezhova, T.A. Keys to the avian malaria parasites. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Iezhova, T.A. Keys to the avian Haemoproteus parasites (Haemosporida, Haemoproteidae). Malar. J. 2022, 21, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Iezhova, T.A. Insights into the biology of Leucocytozoon Species (Haemosporida, Leucocytozoidae): Why is there slow research progress on agents of leucocytozoonosis? Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensch, S.; Stjerman, M.; Hasselquist, D.; Östman, Ö.; Hansson, B.; Westerdahl, H.; Pinheiro, R.T. Host specificity in avian blood parasites: A study of Plasmodium and Haemoproteus mitochondrial DNA amplified from birds. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. B 2000, 267, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, O.; WaldenstrÖm, J.; Bensch, S. A new PCR assay for simultaneous studies of Leucocytozoon, Plasmodium, and Haemoproteus from avain blood. J. Pasasitol. 2004, 90, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensch, S.; Hellgren, O.; Pérez-Tris, J. MalAvi: A public database of malaria parasites and related haemosporidians in avian hosts based on mitochondrial cytochrome b lineages. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009, 9, 1353–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgūnas, M.; Palinauskas, V.; Platonova, E.; Lezhova, T.; Valkiūnas, G. The experimental study on susceptibility of common European songbirds to Plasmodium elongatum (lineage pGRW6), a widespread avian malaria parasite. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.B. Avian malaria: Clinical and chemical pathology of Plasmodium gallinaceum in the domesticated fowl Gallus gallus. Avian. Pathol. 2005, 34, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgūnas, M.; Bukauskaitė, D.; Palinauskas, V.; Iezhova, T.; Fragner, K.; Platonova, E.; Weissenböck, H.; Valkiūnas, G. Patterns of Plasmodium homocircumflexum virulence in experimentally infected passerine birds. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, C.T.; Woods, K.L.; Dusek, R.J.; Sileo, L.S.; Iko, W.M. Wildlife disease and conservation in Hawaii: Pathogenicity of avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum) in experimentally infected Iiwi (Vestiaria coccinea). Parasitology 1995, 111, S59–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Catedral, L.; Brunton, D.; Stidworthy, M.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Pennycott, T.; Schulze, C.; Braun, M.; Wink, M.; Gerlach, H.; Pendl, H.; et al. Haemoproteus minutus is highly virulent for Australasian and South American parrots. Parasit. Vectors. 2019, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.R.; Koo, B.-S.; Jeon, E.-O.; Han, M.-S.; Min, K.-C.; Lee, S.B.; Bae, Y.; Mo, I.-P. Pathology and molecular characterization of recent Leucocytozoon caulleryi cases in layer flocks. J. Biomed. Res. 2016, 30, 517–524. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.-L.; Sun, H.-T.; Zhao, Y.-C.; Hou, X.-W.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Q.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Ni, H.-B. Global prevalence of Plasmodium infection in wild birds: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res. J. Vet. Sci. 2024, 168, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattaradilokrat, S.; Tiyamaneea, W.; Simpalipana, P.; Kaewthamasornb, M.; Saiwichai, T.; Li, J.; Harnyuttanakorna, P. Molecular detection of the avian malaria parasite Plasmodium gallinaceum in Thailand. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 210, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Iezhova, T.A. Exo-erythrocytic development of avian malaria and related haemosporidian parasites. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, E.; Hunter, S.; Howe, L.; Castillo-Alcala, F. The pathology of fatal avian malaria due to Plasmodium elongatum (GRW6) and Plasmodium matutinum (LINN1) infection in New Zealand Kiwi (Apteryx spp.). Animals 2022, 12, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, M.; Ozawa, K.; Kondo, H.; Echigoya, Y.; Shibuya, H.; Sato, Y.; Sehgal, R.N.M. A fatal case of a captive snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus) with Haemoproteus infection in Japan. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohuang, T.; Jittimanee, S.; Junnu, S. Pathology and molecular characterization of Leucocytozoon caulleryi from backyard chickens in Khon Kaen Province, Thailand. Vet. World. 2021, 14, 2634–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornpanom, P.; Fernandes Chagas, C.R.; Lertwatcharasarakul, P.; Kasorndorkbua, C.; Valkiūnas, G.; Salakij, C. Molecular prevalence and phylogenetic relationship of Haemoproteus and Plasmodium parasites of owls in Thailand: Data from a rehabilitation centre. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2019, 9, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuda, P. Detection of avian malaria in wild birds at Trisik beach of Yogyakarta, Java (Indonesia). Ann. Parasitol. 2019, 65, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Sang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in cats in mainland China 2016–2020: A meta-analysis. J. Vet. Sci. 2021, 23, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. Conducting meta-analyses of proportions in R. J. Behav. Data Sci. 2023, 3, 64–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huedo-Medina, T.B.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Marín-Martínez, F.; Botella, J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol. Methods 2006, 11, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadjian, G.; Martinsen, E.; Duval, L.; Chavatte, J.M.; Landau, I. Haemoproteus ilanpapernai n. sp. (Apicomplexa, Haemoproteidae) in Strix seloputo from Singapore: Morphological description and reassignment of molecular data. Parasite 2014, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Prasopsom, P.; Salakij, C.; Lertwatcharasarakul, P.; Pornpranom, P. Hematological and phylogenetic studies of Leucocytozoon spp. in backyard chickens and fighting cocks around Kamphaeng Saen, Thailand. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2020, 54, 595–602. [Google Scholar]

- Vaisusuk, K.; Chatan, W.; Seerintra, T.; Piratae, S. High prevalence of Plasmodium Infection in fighting cocks in Thailand determined with a molecular method. J. Vet. Res. 2022, 66, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archawaranon, M. First report of Haemoproteus sp. in Hill Mynah blood in Thailand. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2005, 4, 523–525. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, B.K.C.; Paller, V.G.V.; de Guia, A.P.O.; Balatibat, J.B.; Gonzalez, J.C.T. Prevalence of avian haemosporidians among understorey birds of Mt. Banahaw de Lucban, Philippines. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2015, 63, 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Prompiram, P.; Kaewviyudth, S.; Sukthana, Y.; Rattanakorn, P. Study of morphological characteristic and prevalence of Haemoproteus blood parasite in passerines in bung boraphet. Thai J. Vet. Med. 2015, 45, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumpim, P.; Chawengkirttikul, R.; Junsiri, W.; Watthanadirek, A.; Poolsawat, N.; Minsakorn, S.; Srionrod, N.; Anuracpreeda, P. Molecular detection and genetic diversity of Leucocytozoon sabrazesi in chickens in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16686, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salakij, C.; Pornpanom, P.; Lertwatcharasarakul, P.; Kasorndorkbua, C.; Salakij, J. Haemoproteus in barn and collared scops owls from Thailand. J. Vet. Sci. 2018, 19, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavatte, J.M.; Okumura, C.; Landau, I. Haematozoa of the great blue turacos, Corythaeola cristata (Vieillot, 1816) (Aves: Musophagiformes: Musophagidae) imported to Singapore jurong bird park with description and molecular characterisation of Haemoproteus (Parahaemoproteus) minchini new species (Apicomplexa: Haemosporidia: Haemoproteidae). Raffles Bull. Zool. 2017, 65, 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Masello, J.F.; Martínez, J.; Calderón, L.; Wink, M.; Quillfeldt, P.; Sanz, V.; Theuerkauf, J.; Ortiz-Catedral, L.; Berkunsky, I.; Brunton, D.; et al. Can the intake of antiparasitic secondary metabolites explain the low prevalence of hemoparasites among wild Psittaciformes? Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonchuay, K.; Thomrongsuwannakij, T.; Chagas, C.R.F.; Pornpanom, P. Prevalence and diversity of blood parasites (Plasmodium, Leucocytozoon and Trypanosoma) in backyard chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) raised in Southern Thailand. Animals 2023, 13, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatan, W.; Khemthong, K.; Akkharaphichet, K.; Suwarach, P.; Seerintra, T.; Piratae, S. Molecular survey and genetic diversity of Plasmodium sp. infesting domestic poultry in Northeastern Thailand. J. Vet. Res. 2024, 68, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamayanti, E.; Priyowidodo, D.; Nurcahyo, W.; Firdausy, L.W. Morphological and molecular characteristics of Plasmodium juxtanucleare in layer chicken from three districts of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Vet. World 2023, 16, 1576–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, K.; Zehtindjiev, P.; Mariaux, J.; Georgiev, B.B. Genetic diversity of avian haemosporidians in Malaysia: Cytochrome b lineages of the genera Plasmodium and Haemoproteus (Haemosporida) from Selangor. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 31, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertwatcharasarakul, P.; Salakij, C.; Prasopsom, P.; Kasorndorkbua, C.; Jakthong, P.; Santavakul, M.; Suwanasaeng, P.; Ploypan, R. Molecular and morphological analyses of Leucocytozoon parasites (Haemosporida: Leucocytozoidae) in raptors from Thailand. Acta Parasitol. 2021, 66, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muriel, J.; Marzal, A.; Magallanes, S.; García-Longoria, L.; Suarez-Rubio, M.; Bates, P.J.J.; Lin, H.H.; Soe, A.N.; Oo, K.S.; Aye, A.A.; et al. Prevalence and diversity of avian haemosporidians may vary with anthropogenic disturbance in tropical habitats in Myanmar. Diversity 2021, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noni, V.; Tan, C.S. Prevalence of haemosporidia in Asian glossy starling with discovery of misbinding of Haemoproteus-specific primer to Plasmodium genera in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piratae, S.; Vaisusuk, K.; Chatan, W. Prevalence and molecular identification of Leucocytozoon spp. in fighting cocks (Gallus gallus) in Thailand. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 2149–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornpanom, P.; Kasorndorkbua, C.; Lertwatcharasarakul, P.; Salakij, C. Prevalence and genetic diversity of Haemoproteus and Plasmodium in raptors from Thailand: Data from rehabilitation center. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2021, 16, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prompiram, P.; Mongkolphan, C.; Poltep, K.; Chunchob, S.; Sontigun, N.; Chareonviriyaphap, T. Baseline study of the morphological and genetic characteristics of Haemoproteus parasites in wild pigeons (Columba livia) from paddy fields in Thailand. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2023, 21, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subaneg, S.; Sitdhibutr, R.; Pornpanom, P.; Lertwatcharasarakul, P.; Ploypan, R.; Kiewpong, A.; Chatkaewchai, B.; To-adithep, N.; Kasorndorkbua, C. Molecular prevalence and haematological assessments of avian malaria in wild raptors of Thailand. Birds 2024, 5, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, S.Y.; Chel, H.M.; Hmoon, M.M.; Htun, L.L.; Bawm, S.; Win, M.M.; Murata, S.; Nonaka, N.; Nakao, R.; Katakura, K. Detection and molecular identification of Leucocytozoon and Plasmodium species from village chickens in different areas of Myanmar. Acta Trop. 2020, 212, 105719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukauskaite, D.; Ziegyte, R.; Palinauskas, V.; Iezhova, T.A.; Dimitrov, D.; Ilgunas, M.; Bernotiene, R.; Markovets, M.Y.; Valkiunas, G. Biting midges (Culicoides, Diptera) transmit Haemoproteus parasites of owls: Evidence from sporogony and molecular phylogeny. Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPointe, D.A.; Goff, M.L.; Atkinson, C.T. Thermal constraints to the sporogonicdevelopment and altitudinal aistribution of avian malaria Plasmodium relictum in Hawai’i. J. Parasitol. Res. 2010, 96, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallis, A.M.; Bennett, G.F. Sporogony of Leucocytozoon and Haemoproteus in simulids and ceratopogonids and a revised classification of the haemosporiida. Can. J. Zool. 1961, 39, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammartsena, A.; Dittapan, S. The swiftlet house business in Thailand sustainable development goals: Study in the legal and policy. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 20, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbro, J.M.; Harrington, L.C. Avian defensive behavior and blood-feeding success of the West Nile vector mosquito, Culex pipiens. Behav. Ecol. 2007, 18, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, J.; Nameer, P.O.; Karuthedathu, D.; Ramaiah, C.; Balakrishnan, B.; Rao, K.M.; Shurpali, S.; Puttaswamaiah, R.; Tavcar, I. On the vagrancy of the Himalayan Vulture Gyps himalayensis to southern India. Indian Birds 2024, 9, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, D.L.; Kasorndorkbua, C. The status of the Himalayan Griffon Gyps himalayensis in South-East Asia. Forktail 2008, 24, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, D.L.; Heim, W.; Chowdhury, S.U.; Choi, C.-Y.; Ktitorov, P.; Kulikova, O.; Kondratyev, A.; Round, P.D.; Allen, D.; Trainor, C.R.; et al. The state of migratory landbirds in the East Asian Flyway: Distributions, threats, and conservation needs. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 613172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, R.N.M.; Valkiunas, G.; Iezhova, T.A.; Smith, T.B. Blood parasites of chickens in Uganda and Cameroon with molecular descriptions of Leucocytozoon schoutedeni and Trypanosoma gallinarum. J. Pasasitol. 2006, 92, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Iezhova, T.-A.; Križanauskienė, A.; Palinauskas, V.; Sehgal, R.N.M.; Bensch, S. A comparative analysis of microscopy and PCR-based detection methods for blood parasites. J. Parasitol. 2008, 94, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).