Simple Summary

Understanding the air quality inside modern chicken houses is essential for protecting both animal health and the well-being of farm workers. In winter, poultry farms often reduce ventilation to maintain warmth, which unintentionally allows airborne bacteria to build up. Our study examined the air inside Taihang chicken houses during three important stages of growth—early chicks, growing birds, and adult layers—under typical winter conditions. We found that the amount of airborne bacteria increased steadily as the birds grew and that smaller particles capable of reaching deeper into the lungs became more common over time. We also discovered that the types of bacteria in the air changed with age, shifting from environmental and potentially harmful species in young-chick environments toward more diverse communities that included bacteria originating from the birds’ own digestive systems. These findings show that winter creates unique challenges for air quality management in poultry houses and highlight when bacterial exposure risks are likely to be highest. Our results provide valuable guidance for improving ventilation, hygiene, and the working environment on farms, ultimately supporting healthier flocks, safer workplaces, and more sustainable poultry production.

Abstract

Bioaerosols are a major source of airborne microbial contamination in intensive poultry production systems. Their concentration and community structure can profoundly influence animal health, public health, and the overall safety of the farming environment. However, the dynamic characteristics of bacterial aerosols in enclosed poultry houses during winter remain insufficiently studied. Using Taihang chickens as a model, this study investigated three key production stages—brooding (15 days), growing (60 days), and laying (150 days)—under winter cage-rearing conditions. A six-stage Andersen sampler was employed alongside culture-dependent enumeration and 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing to analyze variations in bacterial aerosol concentration, particle size distribution, and community succession patterns. The results revealed a significant increase in the concentration of culturable airborne bacteria with bird age, rising from 8.98 × 103 colony-forming unit (CFU)/m3 to 2.89 × 104 CFU/m3 (p < 0.001). The particle size distribution progressively shifted from larger, settleable particles (≥4.7 μm) toward smaller, respirable particles (<4.7 μm). Microbial sequencing indicated a continuous increase in bacterial alpha diversity across the three stages (Chao1 and Shannon indices, p < 0.05), while beta diversity exhibited stage-specific clustering, reflecting clear differences in community assembly. The composition of dominant bacterial genera transitioned from potentially pathogenic taxa such as Acinetobacter and Corynebacterium during the brooding stage to a greater abundance of beneficial genera, including Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, and Ruminococcus, in later stages. This shift suggests a potential ecological link between aerosolized bacterial communities and host development, possibly related to the aerosolization of gut microbiota. Notably, several zoonotic bacterial species were detected in the poultry house air, indicating potential public health and occupational exposure risks under winter confinement conditions. This study is the first to elucidate the ecological succession patterns of airborne bacterial aerosols in Taihang chicken houses across different growth stages during winter. The findings provide a scientific basis for optimizing winter ventilation strategies, implementing stage-specific environmental controls, and reducing pathogen transmission and occupational hazards.

1. Introduction

As one of the world’s largest producers and consumers of poultry, China remains a global leader in both poultry meat and egg production. According to the latest FAO livestock and poultry outlook report, national poultry meat output exceeded 24 million tons in 2023, and egg production surpassed 35 million tons, ranking first worldwide [1]. This sector plays a vital role in ensuring national food security and supplying high-quality dietary protein. With the ongoing intensification and modernization of animal husbandry, enclosed cage systems have been widely implemented in cold northern regions to improve production efficiency, facilitate controlled waste management, and enhance environmental regulation [2,3]. However, such confined and high-density rearing systems also promote the accumulation of bioaerosols within poultry houses. These aerial pollutants comprise a complex mixture of particulate matter, culturable and unculturable microorganisms—including bacteria, fungi, and viruses—as well as endotoxins and noxious gases such as ammonia and hydrogen sulfide [4,5]. These components pose potential threats to animal welfare, the respiratory health of farm workers, and the surrounding environment [6,7,8].

Previous studies have established that inhalable fine particulate matter, particularly particles in the particulate matter (PM) 2.5–PM4.7 size range, can serve as carriers for bacterial aerosols. Experimental and occupational exposure studies have demonstrated that such particles induce oxidative stress responses and alter respiratory immune function, including airway inflammation and immune dysregulation [8,9]. Workers subjected to long-term exposure to high aerosol concentrations exhibit increased incidence of airway hypersensitivity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and respiratory infections [7]. Moreover, airborne transmission of pathogenic or zoonotic microorganisms within poultry houses may not only accelerate intra-flock disease spread but also raise public health concerns for both farm workers and nearby communities [6,8,10].

Winter conditions exert a particularly significant influence on this issue. In northern China, low ambient temperatures often lead to reduced ventilation in poultry houses as a means of conserving heat. While this strategy lowers energy consumption, it also encourages the buildup of particulate matter, microorganisms, and harmful gases, thereby modifying their transport behavior, size distribution, and biological load [9,10]. The balance between ventilation and insulation creates distinct environmental selection pressures that shape the structure of microbial aerosol communities. Studies have indicated that the microbial community in poultry houses during winter differs markedly from that in other seasons, typically showing higher microbial density, greater complexity in microbial networks, and an elevated prevalence of potential pathogens [6]. Nevertheless, current understanding of the ecological dynamics of airborne bacterial aerosols in enclosed poultry environments—particularly under winter minimum-ventilation conditions and across different growth stages—remains limited, as existing studies have primarily focused on overall microbial burden rather than stage-resolved community succession [9,11]. Whether aerosol composition follows stage-specific patterns is still an open question.

The Taihang chicken, a native breed from Hebei Province, is valued for its dual-purpose meat and egg production, adaptability to low-quality feed, strong disease resistance, superior meat quality, and well-developed immune system [12,13]. As consumer demand for high-quality and specialty animal products continues to grow, the Taihang chicken industry has expanded substantially. Taihang chickens are known for their strong adaptability, slow-growing characteristics, and high-quality eggs. Recent statistics indicate that the national flock size has reached approximately 20 million birds, producing more than 190,000 tons of high-quality eggs annually [14]. Typical production data show that Taihang hens produce 165–185 eggs per bird per year, with an average daily feed intake of 95–110 g and a feed conversion ratio of 2.5–2.8 during the laying period [15]. These production traits highlight the economic relevance of this breed and underscore the importance of optimizing its housing environment. Accompanying this growth is a rapid shift from traditional free-range systems to high-density, intensive, and facilities-based production models [16]. Under winter enclosed-cage conditions, notable differences in feed intake, activity levels, respiratory excretion, and metabolic output occur across developmental stages—such as the brooding, growing, and laying periods [17,18,19]. These variations are likely to drive stage-dependent shifts in the concentration, size distribution, dominant species, and pathogen-related risks of bacterial aerosols [20]. Without effective control of aerosol pollution during winter, even excellent genetic stock, high-quality feed, and strict vaccination protocols may fail to ensure optimal production performance [21].

Although recent research has addressed seasonal variation, exposure risks, and mitigation strategies related to bioaerosols in livestock buildings, systematic investigations targeting the multi-factor interplay among winter enclosed-cage environments, local poultry breeds, different production stages, and bacterial aerosol ecological succession are still lacking [22,23]. Therefore, this study conducted systematic monitoring of bacterial aerosols in the air of typical enclosed Taihang chicken houses in Hebei Province during winter, covering the brooding, growing, and laying periods. Using a six-stage Andersen sampler coupled with 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing, we aimed to characterize the temporal dynamics of aerosol concentration, particle size distribution, biodiversity, and community structure throughout the winter period. Our findings are expected to advance the understanding of microbial aerobiology in enclosed poultry environments under winter conditions. Importantly, the stage-specific patterns identified in this study can be incorporated into practical management guidelines by informing winter ventilation adjustments, refining stage-dependent cleaning and disinfection schedules, and supporting targeted monitoring of airborne microbial loads. These applications provide a scientific basis for improving flock productivity and reducing occupational and public health risks in cold-region poultry systems. This study provides the first stage-resolved characterization of bacterial aerosol dynamics in winter poultry houses, offering new insights into how restricted ventilation and host developmental factors jointly shape airborne microbiomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Experimental Design

This study was conducted during the winter (December 2024) at five standardized, large-scale cage-layer farms housing Taihang chickens in Hebei Province. All poultry houses were fully enclosed with a multi-tiered staircase cage design, equipped with mechanical ventilation and centralized manure-belt cleaning systems. Each poultry house contained approximately 12,000–15,000 Taihang chickens housed in a fully enclosed. Each cage housed 5 birds, corresponding to a stocking density of approximately 4.17 birds/m2. Manure was removed by the automatic belt system every 48 h. During the winter season, the houses operated under routine thermal insulation and a minimum-ventilation mode, maintaining an air speed of ≤0.20 m/s. To characterize the dynamics of airborne bacterial aerosols across different growth stages, sampling was conducted at three representative phases of the production cycle: the brooding stage at approximately 1–3 weeks of age (15 days), the growing stage at approximately 8–10 weeks of age (60 days), and the early laying stage at approximately 20–23 weeks of age (150 days). Taihang chickens typically reach the onset of lay at approximately 140–160 days of age (20–23 weeks), with an average body weight of 1.35–1.55 kg at first lay. The 150-day sampling point in this study therefore corresponds to the early laying stage, when reproductive maturity and metabolic demand increase substantially. The environmental conditions within the houses were maintained as follows: Brooding stage (15 days): 30–35 °C, 60–70% relative humidity; houses operated under minimum winter ventilation with an air speed ≤ 0.20 m/s. Growing stage (60 days): 22–27 °C, 55–65% relative humidity; ventilation and heating adjusted to maintain stable airflow and thermal insulation. Laying stage (150 days): 15–20 °C, 50–60% relative humidity; minimum-ventilation mode maintained with controlled airflow to prevent heat loss. These controlled environmental parameters reflect typical winter operational conditions in enclosed multi-tier cage systems. Air sampling at 15, 60, and 150 days was conducted using a cross-sectional design across different flocks housed in the same type of enclosed Taihang chicken houses. All houses had identical structural design, stocking density standards, cage configuration, and ventilation settings. Each flock was sampled at the corresponding production stage, following the same management schedule. This design ensured that differences observed among stages reflected biological and production-stage characteristics rather than variations in housing or density.

A total of five fixed sampling points were established within each house at each farm and for each growth stage. These points were strategically located in ventilation zones at the front, middle, and rear of the house, as well as at upper and lower tiers representing typical breathing heights. All sampling at these five points within a single house was completed on the same day. This design resulted in a total of 75 air samples, calculated as: 5 farms × 3 growth stages × 5 sampling points = 75 samples. The five samples collected per stage were assigned to two analytical approaches. For culturable bacterial counting, all samples were analyzed individually to allow statistical comparison of airborne bacterial load and particle size distribution. For 16S rRNA gene sequencing, however, the five samples were pooled into one composite sample. This pooling strategy is commonly used in bioaerosol studies to obtain sufficient microbial biomass for reliable DNA extraction, particularly under winter minimum-ventilation conditions, and to generate a representative profile of the overall airborne bacterial community at each growth stage.

16S rRNA High-Throughput Sequencing Analysis: To profile the overall composition and diversity of the airborne bacterial community, the biomass from the five samples obtained from the same farm and stage was pooled into a single composite sample. This pooling strategy yielded a total of 15 composite samples for sequencing (5 farms × 3 stages).

This integrated sampling strategy ensured statistical robustness for quantifying culturable microbial load while maintaining representativeness and cost-effectiveness for community structure analysis, adhering to common experimental design principles in poultry aerosol research.

2.2. Airborne Microorganism Sampling and Culturable Counting

The six-stage impactor, operating at a flow rate of 28.3 L·min−1, fractionated particles according to the following aerodynamic diameters: Stage 1: ≥7.0 μm; Stage 2: 4.7–7.0 μm; Stage 3: 3.3–4.7 μm; Stage 4: 2.1–3.3 μm; Stage 5: 1.1–2.1 μm; and Stage 6: 0.65–1.1 μm. At each sampling point, collection was conducted at a height of approximately 1.2–1.5 m above the ground, corresponding to the typical breathing zone of the chickens. A single sampling volume of 300 L (over a duration of 10.6 min) was collected per point. Each stage of the impactor was loaded with a pre-poured Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) plate.

Following sampling, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h for colony enumeration. To monitor potential contamination, both transport blanks (unopened plates carried to and from the site) and field exposure blanks (plates opened at the site without active sampling) were included during each sampling event. The concentration of culturable bacteria in CFU per cubic meter of air (CFU·m−3) was calculated according to established methods [10].

2.3. Aerosol Sample Processing and DNA Extraction

The airborne microorganisms were collected following a method adapted from previous studies. Aerosol sampling was conducted using a high-volume air sampler (Model HH02-LS120, Beijing Hvarian Nuclear Safety Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) loaded with pre-sterilized Tissuquartz™ quartz fiber filters (20.32 cm × 25.4 cm, PALL, New York, NY, USA). To ensure collection efficiency and sample representativeness, the sampler operated continuously for 12 h at a high flow rate of 1000 L/min [24]. Sampling was simultaneously performed at five designated points within the poultry house of each of the five Taihang chicken farms during the brooding, growing, and laying stages. After the 12-h collection, the filters from these five parallel sampling points were pooled in the laboratory to form one composite sample per house per stage for subsequent nucleic acid analysis. To minimize background contamination, all filters were pre-treated by baking in a muffle furnace at 500 °C for 48 h. Post-sampling, each filter was immediately placed into a sterile zip-lock bag, transported to the laboratory in a portable cooler, and stored at −80 °C until processing. Prior to DNA extraction, each filter was cut into small pieces of approximately equal weight (weight difference ≤ 1 mg) using sterile scissors. The pieces were transferred to a sterile 50 mL centrifuge tube, and ultrapure water was added, followed by vigorous vortexing to release microorganisms from the filter into the aqueous phase. The resulting suspension was centrifuged at 25,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet the total biomass of bioaerosol particles. Total genomic DNA was then extracted from the pellet using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method. The concentration and purity of the extracted DNA were measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and its integrity was assessed by 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis. For samples that failed to meet the quality standards, DNA re-extraction was performed until the quality was sufficient for downstream amplification and library construction.

2.4. 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing and Library Construction

The V3–V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primer pair 341F (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in a total volume of 25 μL. The reaction mixture comprised 12.5 μL of 2× high-fidelity master mix, 0.2 μM of each primer, and 10–20 ng of template DNA. The thermal cycling protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; followed by 30–32 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 45 s; with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Negative and positive controls were included in each amplification batch. The PCR products were verified for quality and specificity via 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and subsequently purified using a gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts for library construction. Sequencing libraries were prepared using the TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform for 250 bp paired-end reads. Primary quality control of the raw sequencing data and data delivery were performed by Novogene Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under BioProject accession number PRJNA1354577.

2.5. Bioinformatic Analysis of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Data

Raw sequencing reads were first processed for quality control using QIIME2 (version 2025.4). This step involved the removal of adapter contaminants, low-quality sequences, and ambiguous nucleotides to generate high-quality clean tags. Subsequently, chimeric sequences were detected and filtered out using UCHIME (version 4.2). The resulting effective tags were then clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold using Uparse (version 7.0.1001), from which representative sequences for each OTU were selected. Taxonomic annotation of these representative sequences was performed against the SILVA 132 database to obtain phylogenetic information at levels from phylum to genus. For community diversity analysis, alpha diversity, reflecting microbial richness and diversity within samples, was assessed using the Chao1 and Shannon indices. Beta diversity, which measures compositional differences between samples, was calculated using Bray–Curtis dissimilarity based on OTU profiles and visualized through Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCA) to reveal structural similarities and differences among microbial communities. Statistically significant differentially abundant taxa were identified through comparative analysis, and their distribution patterns were visualized using clustered heatmaps and stacked bar plots to illustrate the overall differences in airborne bacterial community composition across the various growth stages.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses of airborne bacterial concentrations and diversity indices were performed using SPSS (version 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism (version 8.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Differences across growth stages were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test to control for multiple testing, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. All experimental data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD).

3. Results

3.1. Concentration and Size Distribution of Airborne Culturable Bacteria

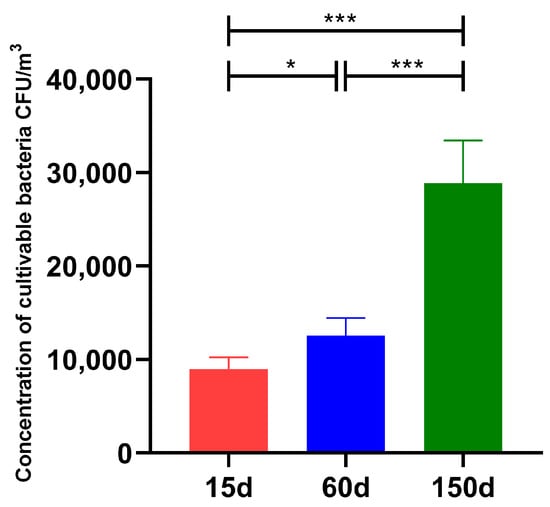

The concentration of airborne culturable bacteria demonstrated significant dynamic changes across different growth stages of the Taihang chickens (Figure 1). At 15 days of age, the bacterial concentration was 8.98 × 103 ± 1.26 × 103 CFU/m3. A significant increase to 1.26 × 104 ± 1.86 × 103 CFU/m3 was observed at 60 days of age (p < 0.05). The concentration further rose markedly to 2.89 × 104 ± 4.58 × 103 CFU/m3 by 150 days of age (p < 0.001). Notably, the concentration at 150 days was also significantly higher than that at 60 days (p < 0.001). This progressive accumulation of bacterial bioaerosols with increasing flock age and metabolic activity is likely associated with enhanced microbial emissions from the chickens, manure fermentation, and limited ventilation efficiency in the poultry houses.

Figure 1.

Dynamics of culturable bacterial concentrations in the air of enclosed Taihang chicken houses during three growth stages in winter (n = 5 farms × 5 sampling points). Bacterial concentrations at 15, 60, and 150 days of age progressively increased, ranging from 103 to 104 CFU/m3 (mean ± SD), with statistically significant differences between stages (* p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001).

3.2. Size Distribution of Culturable Bacteria

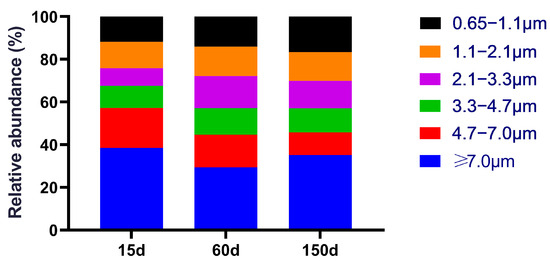

The size distribution of culturable bacteria also exhibited significant stage-specific dynamics (Figure 2). At 15 days of age, bacteria were predominantly associated with large particles (≥4.7 μm, 57.18%), with the highest proportion found in the ≥7.0 μm fraction (38.56%). This pattern suggests that the airborne bacteria during the early stage primarily originated from settleable particulates, such as fecal dust, feather debris, and feed fragments. By 60 days of age, the proportion of large particles decreased to 44.65%, while the fraction in the 3.3–4.7 μm range peaked at 12.46%. This shift indicates a transition towards respirable particle sizes capable of depositing in the deeper respiratory tract. A fine-particle-dominant profile emerged at 150 days of age, with small particles (<4.7 μm) constituting 54.21% of the total, despite a slight rebound in large particles (45.79%). Given that fine particles possess prolonged airborne residence times, higher respiratory deposition efficiency, and greater potential for inducing inflammation, this particle-size transition signifies a dual increase in airborne exposure risk—both in quantity and potential toxicity—as the flock ages during winter. This trend not only elevates the risk of oxidative stress in poultry but also raises potential health concerns for farm workers due to increased exposure.

Figure 2.

Size-fractionated distribution of culturable bacteria across three growth stages (15, 60, and 150 days). The distribution shifted from large, settleable particles (≥4.7 μm) dominating at 15 days toward significantly increased proportions of respirable particles (<4.7 μm) at 60 and 150 days, accompanied by notable enrichment in the 3.3–4.7 μm size range. n = 5 farms × 5 sampling points.

3.3. General Sequencing Characteristics and OTUs Abundance

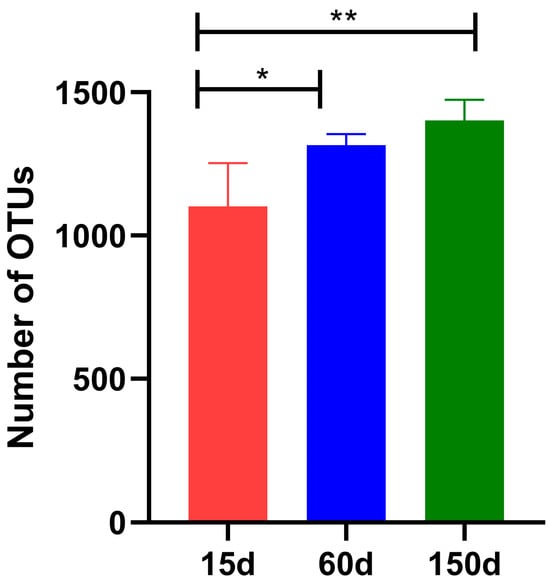

After quality control, a total of 5.97 × 104 high-quality effective sequences were obtained. Rarefaction curves for all samples approached a plateau, indicating adequate sequencing depth for diversity analysis (Supplementary Figure S1). The OTUs demonstrated a significant increasing trend with flock age (Figure 3): 1.10 × 103 ± 1.36 × 102 at 15 days, rising to 1.32 × 103 ± 0.38 × 102 at 60 days (p < 0.05), and further increasing to 1.40 × 103 ± 0.73 × 102 at 150 days (p < 0.01). The rarefaction curves for all samples approached a plateau, indicating sufficient sequencing depth and confirming that the data were representative and reliable for subsequent analysis. These results reveal that within the enclosed environment during winter, the airborne bacterial community becomes progressively richer, concomitant with the physiological development and metabolic changes of the chickens.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) richness in air samples across different growth stages (n = 5 farms × 5 sampling points). OTU counts were lowest at 15 days, increased significantly at 60 days, and further elevated at 150 days (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01).

3.4. Changes in Bacterial Community Alpha and Beta Diversity

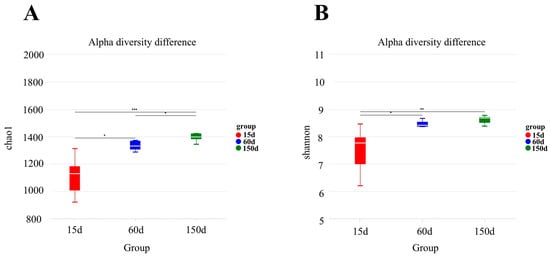

Both the Chao1 and Shannon indices indicated a significant increase in the alpha diversity of the bacterial communities with increasing flock age (Figure 4). The Chao1 index rose from 1.11 × 103 ± 1.50 × 102 at 15 days to 1.33 × 103 ± 3.90 × 101 at 60 days, and further to 1.41 × 103 ± 7.40 × 101 at 150 days, with all pairwise comparisons being statistically significant (p < 0.05). The most pronounced increase in the Shannon index occurred between 15 days (7.50 ± 0.90) and 60 days (8.50 ± 0.10) (p < 0.05), followed by a more modest rise to 8.60 ± 0.20 at 150 days. These trends suggest that the richness and evenness of the airborne bacterial community were rapidly established during the mid-growth stage and subsequently stabilized.

Figure 4.

Changes in alpha diversity indices (Chao1 and Shannon) across 15, 60, and 150 days of age (n = 5 farms × 5 sampling points). The Chao1 index progressively increased (A). The Shannon index showed the most significant increase from 15 to 60 days (B). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

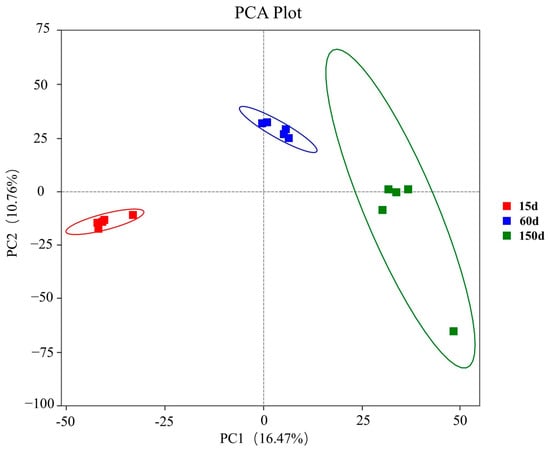

PCA revealed a clear separation of bacterial community structures among the three growth stages (Figure 5). The distinct clustering of samples from each stage, with no overlap observed, indicates a time-dependent assembly pattern of the airborne bacterial communities in the Taihang chicken houses during winter. This structural divergence is likely driven by a combination of factors, including increased manure excretion, changes in stocking density, and the specific microclimate and ventilation strategies within the houses, which collectively exert selective pressures on the microbiota.

Figure 5.

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCA) of bacterial community β-diversity across the three growth stages based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity (n = 5 farms × 5 sampling points).

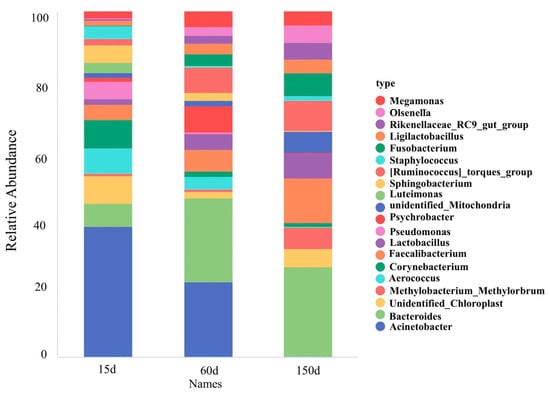

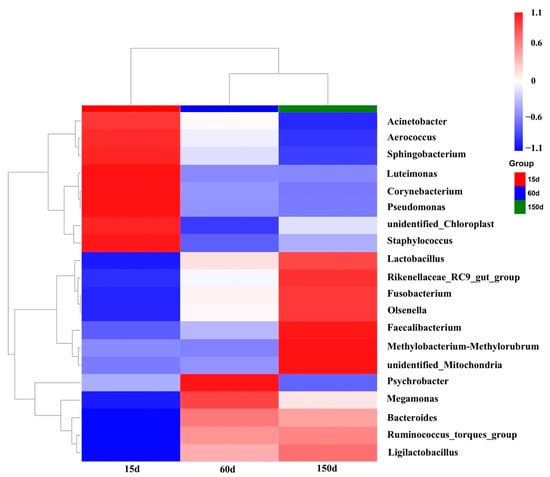

3.5. Bacterial Community Composition and Analysis of Potential Pathogens

The composition of dominant bacterial genera demonstrated significant succession across the growth stages (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Beneficial or conditionally beneficial genera, such as Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Ruminococcus, and Faecalibacterium, became increasingly predominant from 60 days of age onward. This shift reflects a progression towards a more complex and diversified community structure. However, several genera listed as zoonotic pathogens in national catalogs, including Acinetobacter, Corynebacterium, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, and Fusobacterium, were also detected in the winter housing environment. Notably, Acinetobacter accounted for a substantial 37.90% of the relative abundance at 15 days but declined rapidly thereafter. To provide quantitative support for the observed trends, detailed relative abundance values of dominant genera and families across the three growth stages are presented in Supplementary Table S1. This pattern suggests that early-stage airborne contamination was primarily dominated by environmental bacteria, whereas the increased presence of host-associated taxa in later stages may reflect greater biological activity and organic matter accumulation as birds mature.

Figure 6.

Ecological succession of dominant bacterial genera across three growth stages (n = 5 farms × 5 sampling points).

Figure 7.

Heatmap clustering of the top 20 most abundant bacterial genera (n = 5 farms × 5 sampling points).

4. Discussion

Airborne bioaerosols represent one of the most epidemiologically significant vectors of contamination in intensive poultry operations. They can carry bacteria, viruses, fungal spores, antibiotic resistance genes, and endotoxins, often coexisting with inhalable particulate matter and irritant gases such as ammonia [6]. This complex mixture poses considerable threats to poultry health, the respiratory systems of farm workers, and environmental safety [8]. Our study systematically elucidates the dynamics of bacterial aerosols in enclosed, cage-housed Taihang chicken houses during winter, characterizing the stage-dependent patterns of concentration accumulation, particle size migration, and community succession. From a microbial ecology perspective, our findings illustrate a dynamic process best described as “enclosure in winter → restricted ventilation → particulate accumulation → microbial succession → risk superposition.” Understanding this cascade is of immediate practical importance for implementing precise environmental control in poultry facilities located in cold regions [9,25]. By revealing the temporal succession of airborne bacterial communities across growth stages, this study advances the current understanding of winter poultry-house microbiology and identifies critical intervention windows for bioaerosol control.

This study demonstrated that the concentration of culturable airborne bacteria in Taihang chicken houses increased markedly across growth stages during winter, rising from 8.98 × 103 CFU/m3 at 15 days to 2.89 × 104 CFU/m3 at 150 days. Although our study did not directly quantify environmental drivers such as stocking density, manure accumulation, feather debris, or feed dust, the observed trend is consistent with patterns reported in previous poultry-house studies in which these factors have been proposed to contribute to elevated airborne microbial loads [9]. Moreover, low ventilation rates and dry winter conditions likely facilitate prolonged particle suspension and enhanced bacterial persistence [26]. This phenomenon aligns with earlier findings from livestock buildings in northern winter climates, suggesting that the winter environment itself has an amplifying effect on bacterial aerosol accumulation.

Of greater concern is the observed temporal shift in particle size distribution. As the flock aged, the aerosol profile transitioned from being dominated by large particles (which primarily deposit in the upper respiratory tract) to a finer-particle-dominated regime. These smaller particles can penetrate deeper into the lower respiratory tract and even reach the alveolar regions [27,28,29]. Particle size is a critical determinant of the deposition site within the host, the efficiency of pathogen carriage, airborne residence time, and the potential for cross-host transmission [30]. Consequently, the combination of “decreasing particle size + increasing concentration” signifies a dual escalation of airborne exposure risk during the later winter period [31]. This synergistic effect can amplify oxidative stress, immune suppression, and respiratory inflammation in poultry, while concurrently elevating the chronic occupational exposure risk for farm workers [32,33,34].

The microbial diversity analysis further confirmed a continuous succession of the aerosolized bacterial communities with flock age. The significant increase in alpha diversity, coupled with the clear separation of communities in the PCA plot for each stage, indicates that the structural shift was not a simple accumulation but an ecological transition from the dominance of environmental bacteria to host-associated taxa. The stage-specific restructuring of OTUs in the enclosed winter environment reflects a community reassembly mechanism driven by host development, immune maturation, manure accumulation, and indoor microclimate parameters. This dynamic aligns with the recently proposed concept of the “aerosolization of gut microbiota.”

In this study, several genera identified in the airborne bacterial community are recognized etiological agents of serious infections in both humans and animals. For instance, Acinetobacter can cause pneumonia and septicemia [35]; Fusobacterium is associated with Lemierre’s syndrome [36,37]; Corynebacterium can lead to respiratory inflammation and diphtheria [38]; and Pseudomonas and Staphylococcus are known to cause pyogenic infections in multiple organs [7,39]. Consequently, the enclosed poultry housing environment during winter presents a potential public health risk, warranting attention from both occupational health and environmental management perspectives. Our findings revealed that the aerosolized community exhibits a dual ecological character, co-harboring both potentially hazardous environmental pathogens and beneficial gut microbes closely linked to host health. On one hand, conditional pathogens such as Acinetobacter, Corynebacterium, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, and Fusobacterium were present at relatively high abundances during the early stage. This is likely attributable to the underdeveloped immune system of chicks, high environmental hygiene pressure, and frequent dispersal of excreta [11,24,26,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Given the low pathogen exposure threshold in chicks, our results highlight the brooding period as a critical window for intensified bioaerosol risk control during winter.

On the other hand, beneficial genera with significance for gut homeostasis, including Bacteroides, Ruminococcus, and Lactobacillus, became progressively dominant as the flock aged [47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. This suggests that as the chickens’ digestive systems matured, their gut microbiota more readily entered the air circulation and came to dominate the aerosolized community. This is not only a result of fecal aerosolization but may also reflect a long-term “ecological spillover” of gut flora into the indoor environment.

It is crucial to emphasize that some of the detected zoonotic-related genera are priority pathogens of national concern. This finding underscores the potential for occupational exposure and a One Health risk within these enclosed winter houses. Without proper environmental management and air monitoring, aerosol transmission could breach the confines of the poultry house, establishing a pathway for regional dissemination and thereby threatening surrounding public health. Consequently, managing airborne microorganisms in winter poultry operations should not be viewed solely through the lens of disease control. It must be integrated into a One Health framework and advanced in parallel with strategies for animal welfare, laborer protection, and environmental sustainability.

This study provides significant insights into the ecological succession patterns of bacterial aerosols in enclosed poultry houses during the critical winter season. Based on our findings, the following strategies are recommended for poultry farms in cold regions: Optimize winter ventilation systems to ensure essential air exchange while maintaining low energy consumption. Enhance disinfection protocols and implement rapid manure removal procedures, particularly during the brooding period. Equip farm workers with certified personal respiratory protective equipment. Establish routine airborne microbial monitoring systems for early detection of potential zoonotic pathogens. Future research should integrate pathogen genomics, investigations into antibiotic resistance gene dissemination, dynamic particulate matter modeling, and host respiratory immune responses. Such multidisciplinary approaches will provide a scientific foundation for developing intelligent, low-carbon, and biosecure management strategies for poultry farming environments.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically elucidates the dynamics of airborne bacterial aerosols in enclosed, cage-housed Taihang chicken facilities during winter, revealing pronounced age-dependent patterns in concentration, particle-size distribution, and community structure. Culturable airborne bacterial concentrations increased progressively across growth stages, accompanied by a notable shift from coarse particles to fine respirable fractions capable of deep lung deposition. This particle-size migration substantially heightens respiratory exposure risks for both poultry and farm workers under winter minimum-ventilation conditions. High-throughput sequencing further demonstrated increasing bacterial diversity with flock age, characterized by a clear successional transition from environmentally derived taxa toward host-associated genera.

Our findings highlight a dual ecological pattern in which potentially pathogenic and beneficial bacteria coexist within the airborne microecosystem. Zoonotic-related taxa were most abundant during the chick stage, reinforcing the brooding period as a critical window for bioaerosol exposure control. Conversely, beneficial genera associated with gut homeostasis became increasingly dominant as birds matured, reflecting the strong ecological coupling between host physiological development, fecal aerosolization processes, and airborne microbial dispersal. This successional trajectory underscores the intrinsic plasticity of the airborne microbiome within intensive poultry environments.

Overall, this study provides mechanistic insight into the formation pathways and ecological succession of bacterial aerosols in winter poultry houses. These findings offer a scientific basis for optimizing ventilation management, airborne contamination control, and biosecurity practices in Taihang chicken production systems in cold regions. From a One Health perspective, future strategies should integrate intelligent ventilation regulation, rapid manure and dust management, continuous airborne microbial monitoring, and strengthened occupational protection to mitigate aerosol transmission risks and promote animal welfare, human health, and environmental sustainability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ani15243635/s1. Figure S1: Rarefaction curves illustrating the sequencing depth and OTU richness of airborne bacterial communities collected from Taihang chicken houses at three different growth stages (15 days, 30 days, and 150 days). Table S1: Relative abundance (%) of dominant bacterial genera in airborne bacterial communities at 15, 60, and 150 days of age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and S.D.; methodology, Y.Y. (Yejin Yang), Z.L. (Zhenyue Li), Z.L. (Zhuhua Liu), H.C. and Z.R.; validation, Y.Y. (Yejin Yang), H.C., C.Z. and Z.Y.; formal analysis, Y.Y. (Yuqing Yang), Z.L. (Zhuhua Liu)., X.C., Z.Y. and W.F.; investigation, Y.Y. (Yuqing Yang), Z.Y., R.Z., W.F., X.C., M.Y. and M.L.; resources, H.L. and S.D.; data curation, Y.Y. (Yuqing Yang), M.L., Z.Y. and M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. (Yejin Yang) and H.C.; writing—review and editing, C.Z., H.C. and S.D.; visualization, Y.Y. (Yuqing Yang) and Z.Y.; supervision, R.Z., H.L. and S.D.; project administration, H.C. and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the special project of introducing talents for scientific research in Hebei Agricultural University, grant number YJ2023038, central government guided local science and technology development fund projects, grant number 246Z6604G, Hebei Agriculture Research System, grant number HBCT2024260101, Hebei Province Modern Poultry Breeding Innovation Team Project, grant number 21326303D, and Shijiazhuang Science and Technology Plan Project, grant number 231500152A.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics. Committee of Hebei Agricultural University (Document number of approval: 20240519, Date: 19 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All original contributions of this study are contained within the article; further details are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bist, R.B.; Bist, K.; Poudel, S.; Subedi, D.; Yang, X.; Paneru, B.; Mani, S.; Wang, D.; Chai, L. Sustainable poultry farming practices: A critical review of current strategies and future prospects. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kistanova, E.; Yotov, S.; Zaimova, D. Intelligent animal husbandry: Present and future. Animals 2024, 14, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibler, J.H.; Dalton, K.; Pekosz, A.; Gray, G.C.; Silbergeld, E.K. Epizootics in industrial livestock production: Preventable gaps in biosecurity and biocontainment. Zoonoses Public Health 2017, 64, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska-Kieltyka, M.; Roman, A.; Nalepa, I. The air we breathe: Air pollution as a prevalent proinflammatory stimulus contributing to neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 647643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. Production phase affects the bioaerosol microbialcomposition and functional potential in swineconfinement buildings. Animals 2019, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; He, L.Y.; Wu, D.L.; Gao, F.Z.; Zhang, M.; Zou, H.Y.; Yao, M.S.; Ying, G.G. Spread of airborne antibiotic resistance from animal farms to the environment: Dispersal pattern and exposure risk. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, C.; Di Filippo, P.; Pomata, D.; Simonetti, G.; Castellani, F.; Uccelletti, D.; Bruni, E.; Federici, E.; Buiarelli, F. Comparison of analytical approaches for identifying airborne microorganisms in a livestock facility. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 147044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, Y. Spatiotemporal variations in the association between particulate matter and airborne bacteria based on the size-resolved respiratory tract deposition in concentrated layer feeding operations. Environ. Int. 2021, 150, 106413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Germain, M.W.; Létourneau, V.; Cruaud, P.; Lemaille, C.; Robitaille, K.; Denis, É.; Boulianne, M.; Duchaine, C. Longitudinal survey of total airborne bacterial and archaeal concentrations and bacterial diversity in enriched colony housing and aviaries for laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. Distribution of aerosol bacteria in broiler houses at different growth stages during winter. Animals 2025, 15, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, B.; Pena, P.; Cervantes, R.; Dias, M.; Viegas, C. Microbial contamination of bedding material: One health in poultry production. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Sun, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Chi, R.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, K.; Li, W.; et al. Microbial diversity and community composition of duodenum microbiota of high and low egg-yielding Taihang chickens identified using 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. Life 2022, 12, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Han, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y. Effect of polymorphisms in the 5′-flanking sequence of MC1R on feather color in Taihang chickens. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wu, X.; Cui, S.; Li, Y.; Mu, Y.; Gao, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, J. Residue Elimination patterns and determination of the withdrawal times of seven antibiotics in eggs of Taihang chickens. Animals 2024, 14, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Ding, H.; Liu, H.; Zang, S.; Zhou, R. Genome-wide re-sequencing reveals selection signatures for important economic traits in Taihang chickens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiaoxian, Y.; Hui, C.; Yingjue, X.; Chenxuan, H.; Jianzhong, X.; Rongyan, Z.; Lijun, X.; Han, W.; Ye, C. Effect of housing system and age on products and bone properties of Taihang chickens. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, T.; Heng, C.; Jiang, L.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Zhan, X. Research note: Metabolic changes and physiological responses of broilers in the final stage of growth exposed to different environmental temperatures. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 2017–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Heng, C.; Jiang, L.; Cai, C.; Zhan, X. Effects of different stocking densities on tracheal barrier function and its metabolic changes in finishing broilers. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 6307–6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Li, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Zheng, W. Assessing temperature distribution inside commercial stacked cage broiler houses in winter. Animals 2024, 14, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descatha, A.; Hamzaoui, H.; Takala, J.; Oppliger, A. A systematized overview of published reviews on biological hazards, occupational health, and safety. Saf. Health Work 2023, 14, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walser, S.M.; Gerstner, D.G.; Brenner, B.; Bünger, J.; Eikmann, T.; Janssen, B.; Kolb, S.; Kolk, A.; Nowak, D.; Raulf, M.; et al. Evaluation of exposure-response relationships for health effects of microbial bioaerosols—A systematic review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2015, 218, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katwal, S.; Singh, Y.; Bedi, J.S.; Chandra, M.; Honparkhe, M. Microbial dynamics and climatic interactions in pig sheds: Insights into airborne microbes and particulate matter concentrations. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Woo, C.; Yamamoto, N.; Choi, H.L. Variations in abundance, diversity and community composition of airborne fungi in swine houses across seasons. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.C.; Lam, G.K.; Chen, J.H.; Li, X.; Ip, F.T.; Yuen, L.L.; Chan, V.W.; AuYeung, C.H.; So, S.Y.; Ho, P.L.; et al. Air dispersal of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Implications for nosocomial transmission during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 116, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storlazzi, C.D.; Takesue, R.K.; Hendrix, A.M. Letter to Editor regarding “Potential impact of the 2023 Lahaina wildfire on the marine environment: Modeling the transport of ash-laden benzo[a]pyrene and pentachlorophenol” by Downs et al. (2024) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.176346. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 970, 178965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindari, Y.R.; Moore, R.J.; Van, T.T.H.; Walkden-Brown, S.W.; Gerber, P.F. Microbial taxa in dust and excreta associated with the productive performance of commercial meat chicken flocks. Anim. Microbiome 2021, 3, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadal, M.; Lassel, L.; Denis, M.; Gibelin, A.; Fournier, S.; Menard, L.; Goulet, H.; Abdi, B.; Farthoukh, M.; Pialoux, G. Role of super-spreader phenomenon in a COVID-19 cluster among healthcare workers in a primary care hospital. J. Infect. 2021, 82, e13–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, J.; Chen, P.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, J.; You, L.; Jin, Y.; Jiang, L.; Tang, F.; et al. Higher SARS-CoV-2 shedding in exhaled aerosol probably contributed to the enhanced transmissibility of omicron ba.5 subvariant. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, H.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Chen, Z.; Tang, F.; Fu, Y.; Jin, Y.; et al. Similar aerosol emission rates and viral loads in upper respiratory tracts for COVID-19 patients with delta and omicron variant infection. Virol. Sin. 2022, 37, 762–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Z.; Zuo, Z.; Yuan, T. Fungal community shows more variations by season and particle size than bacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 925, 171584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, K.; Liu, J.; Pu, J.; Kong, Y.; Dong, S.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Effects of different laying periods on airborne bacterial diversity and antibiotic resistance genes in layer hen houses. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2023, 251, 114173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Wang, K.; Guo, Z.; Huang, K.; Li, Y.; Li, C. Proteomic analysis of dysregulated pulmonary protein expression and potential pathways in broilers induced by particulate matter exposure in poultry houses. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Guo, Q.; Huang, K.; Mao, W.; Wang, K.; Zeng, W.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Nagaoka, K.; Li, C. Exposure to particulate matter in the broiler house causes dyslipidemia and exacerbates it by damaging lung tissue in broilers. Metabolites 2023, 13, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Wang, K.; Fathi, M.A.; Li, Y.; Win-Shwe, T.T.; Li, C. A succession of pulmonary microbiota in broilers during the growth cycle. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiku, V. Acinetobacter baumannii: Virulence strategies and host defense mechanisms. DNA Cell Biol. 2022, 41, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.F.; Zhao, P.Y.; He, X.J.; Jiang, K.; Wang, T.S.; Xiao, J.W.; Sun, D.B.; Guo, D.H. Fusobacterium necrophorum promotes apoptosis and inflammatory cytokine production through the activation of NF-κB and death receptor signaling pathways. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 827750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. Lemierre’s syndrome in the 21st century: A literature review. Cureus 2023, 15, e43685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangutov, E.O.; Kharseeva, G.G.; Alutina, E.L. Corynebacterium spp. as problematic pathogens of the human respiratory tract (review of literature). Klin. Lab. Diagn. 2021, 66, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, T.; Hébraud, M.; Dapkevicius, M.; Maltez, L.; Pereira, J.E.; Capita, R.; Alonso-Calleja, C.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. Genomic and metabolic characteristics of the pathogenicity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzone, J.P.; Mackow, N.A.; van Duin, D. Current treatment options for pneumonia caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 37, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.M.; Lim, S.K.; Kang, H.M.; Kim, J.M.; Moon, J.S.; Jang, K.C.; Kim, J.M.; Joo, Y.S.; Jung, S.C. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-negative bacteria isolated from bovine mastitis between 2003 and 2008 in Korea. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 2020–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupel, D.; Borer, A.; Yosipovich, R.; Nativ, R.; Sagi, O.; Saidel-Odes, L. A multilayered infection control intervention on carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii acquisition: An interrupted time series. Am. J. Infect. Control 2025, 53, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thatrimontrichai, A.; Pannaraj, P.S.; Janjindamai, W.; Dissaneevate, S.; Maneenil, G.; Apisarnthanarak, A. Intervention to reduce carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a neonatal intensive care unit. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Ghany, W.A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of avian origin: Zoonosis and one health implications. Vet. World 2021, 14, 2155–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Gan, J.; Zeng, D.; Li, J.; Yu, H.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Y.; Tan, S.; Li, G.; Luo, C.; et al. Specific microbial taxa and functional capacity contribute to chicken abdominal fat deposition. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 643025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.Y.; Lee, S.I.; Kim, S.D.; Park, J.H.; Kim, G.B.; Yang, S.J. Clonal distribution and antimicrobial resistance of methicillin-susceptible and -resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from broiler farms, slaughterhouses, and retail chicken meat. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 102070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.S.; Mi, J.D.; Mei, L.; Liang, J.; Feng, K.X.; Wu, Y.B.; Liao, X.D.; Wang, Y. Microbial diversity and community variation in the intestines of layer chickens. Animals 2021, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Hu, J.; Peng, H.; Li, B.; Xu, J.; Song, X.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Du, X.; Bu, G.; et al. Research Note: The gut microbiota varies with dietary fiber levels in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, F.; Na, W.; Tan, Z. Dynamic changes in the gut microbiota and metabolites during the growth of Hainan Wenchang chickens. Animals 2023, 13, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, C.; et al. Molecular characterization, receptor binding property, and replication in chickens and mice of H9N2 avian influenza viruses isolated from chickens, peafowls, and wild birds in eastern China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 2098–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, M.; Gong, D. Ligilactobacillus Salivarius improve body growth and anti-oxidation capacity of broiler chickens via regulation of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asare, P.T.; Greppi, A.; Geirnaert, A.; Pennacchia, A.; Babst, A.; Lacroix, C. Glycerol and reuterin-producing Limosilactobacillus reuteri enhance butyrate production and inhibit Enterobacteriaceae in broiler chicken cecal microbiota PolyFermS model. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaytsoff, S.J.M.; Montina, T.; Boras, V.F.; Brassard, J.; Moote, P.E.; Uwiera, R.R.E.; Inglis, G.D. Microbiota transplantation in day-old broiler chickens ameliorates Necrotic enteritis via modulation of the intestinal microbiota and host immune responses. Pathogens 2022, 11, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).