Simple Summary

The forest musk deer (FMD, Moschus berezovskii) is a small mammal belonging to the genus Moschus within the family Moschidae, renowned for the precious musk secreted by the musk glands of its males. However, research into the expression of gene family members within the musk gland tissue and acinar cells of the FMD remains limited. ABC transporters play a crucial role in substance transport within animal and plant organisms. This study identifies 51 ABC genes for the first time in the FMD. Preliminary validation was conducted using transcriptome sequencing data from FMD musk gland tissue, followed by RT-qPCR validation using cells from in vitro cultured musk gland tissue. These findings lay the groundwork for subsequent functional genomics research.

Abstract

The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family is one of the oldest conserved protein families and is widely present in animal and plant cells. However, few studies have investigated the role of ABC in the forest musk deer (FMD; Moschus berezovskii). In this study, we employed bioinformatics methods to identify and analyze the ABC transporter genes in M. berezovskii to elucidate the potential function of ABC genes in musk secretion. A total of 51 members of the MbABC gene family were identified. The analysis encompassed various aspects including physical and chemical properties, phylogenetic tree, structure prediction, conserved motifs, gene structures, chromosome localization, collinearity analysis, and KEGG and GO enrichment. Collinearity analysis revealed that the ABC transporter gene family is conserved in FMD, Cervidae, and five Bovinae species. MbABCB6, MbABCD4, MbABCF3, and MbABCG5 are key genes in protein–protein interaction networks, which are primarily involved in the transport of vitamins, lipids, and proteins. Tissue expression analysis showed that MbABCs were expressed at different stages. The RT-qPCR analysis revealed that 12 MbABC genes were up-regulated in musk gland cells during the non-secretion phase and stimulation phase, particularly MbABCC4d and MbABCC3. This study provides comprehensive information on the ABC gene family in FMD which can be further used for their functional validation.

1. Introduction

The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family represents one of the most ancient and evolutionarily conserved membrane transporter systems, present in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes [1]. These proteins are located in various cellular membranes, including the plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus [2], where they function as ATP-driven transporters facilitating substrate translocation and modulating diverse cellular processes [3]. Structurally, ABC proteins consist of transmembrane domain (TMD) and nucleotide-binding domain (NBD). The classic ABC transporter comprises two TMDs and two NBDs [4]. The NBDs are highly conserved across the family and are responsible for ATP binding and hydrolysis, whereas the TMDs—which form substrate translocation pathways—exhibit considerable sequence divergence, enabling the transport of a broad spectrum of substrates such as ions, lipids, hormones, xenobiotics, secondary metabolites, and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-related compounds [5]. Based on domain architecture, ABC transporters are categorized into three types: full-size transporters (two TMDs and two NBDs), half-size transporters (one TMD and one NBD, which dimerize to form functional units), and soluble transporters (lacking TMDs and involve in non-transport roles) [6,7]. Phylogenetic analyses based on NBD sequence homology have led to the classification of ABC transporters into eight subfamilies: ABCA-ABCH [8]. Among these, ABCA–ABCG are present in animal genomes, such as human (Homo sapiens) [9], with ABCB, ABCC, and ABCG being the most extensively characterized [10]. In contrast, the ABCH subfamily has been identified only in specific animal lineages, such as fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) [11] and zebrafish (Danio rerio) [12].

In mammals, ABCA subfamily members are primarily involved lipid transport [13], whereas ABCB transporters contribute to detoxification by effluxing endogenous metabolites and xenobiotics [14]. The ABCC subfamily influences pharmacokinetics through ATP-dependent transport of various compounds [15], and ABCD proteins are implicated in fatty acid transport and metabolism via intrinsic thioesterase activity [16]. ABCF proteins participate in translational regulation, ribosome assembly, and protein synthesis [17], while ABCG transporters, expressed in tissues such as the liver and intestine, regulate sterol transport—including cholesterol—and mediate drug efflux [18,19].

The forest musk deer (FMD; Moschus berezovskii) is an artiodactyl mammal primarily distributed in Asia. Musk is a precious Chinese herbal remedy and a premium raw ingredient [20]. FMD have musk glands between their navels and genitals that secrete musk [21], valued for its secretion of musk—a substance widely used in traditional medicine and perfumery due to its distinctive fragrance, anti-inflammatory and antitumor properties, and effects on the central nervous and cardiovascular systems [22]. The principal chemical constituents of musk comprise various proteins and peptides, alongside macrocyclic and steroidal [23,24,25]. However, wild FMD populations have experienced a severe decline in recent decades, driven by overexploitation, habitat destruction, and degradation [26], leading to their classification on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Captive breeding programs initiated in China since the 1950s have not sufficiently mitigated population decline or met the high market demand for musk [27]. Consequently, a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying musk secretion is urgently needed to inform strategies for enhancing musk production [28].

To date, comprehensive genomic surveys of ABC transports have been conducted in various vertebrates, including sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) and Japanese lamprey (Lethenteron camtschaticum) [29], Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) [30], mouse (Mus musculus) [31], and human [32,33]. However, a systematic analysis of the ABC transport gene family in FMD has not yet been reported, and lipids constituted 86–88% of natural musk [23]. Consistent with this, a study by Liu et al. revealed significant enrichment of pathways related to ‘fatty acid metabolism’ and ‘unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis’ in the cells [34]. Since ABC transporters are functionally implicated in the transport of lipids and steroids, it is, therefore, plausible that ABC genes fulfil a vital function in the musk secretion stage. We hypothesize that high expression of these genes facilitates and enhances musk secretion in FMD. Therefore, in this study, we performed a genome-wide identification and characterization of ABC transporter gene family in a chromosome-level genome assembly of FMD. We analyzed their physicochemical properties, gene structure, chromosomal localization, phylogenetic tree, collinearity analysis, KEGG and Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment, and protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks. Furthermore, using RNA-seq analysis and RT-qPCR validation, we investigated the expression profiles of 14 MbABC genes in the musk gland cells under agonist-stimulated and non-stimulated conditions, simulating the secretory phase of musk production. This study provides foundational insights into the molecular mechanisms of musk secretion and supports conservation-oriented applications for sustainable musk production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genome-Wide Identification of MbABC Family Genes

The chromosome-level genome and annotation of FMD was downloaded from MuskDB (http://muskdb.cn/home/, accessed on 11 April 2024). The protein sequence of H. sapiens, M. musculus, domestic cattle (Bos taurus), goat (Capra hircus), sheep (Ovis aries), and zebrafish (Danio rerio) were downloaded from UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/, accessed on 5 May 2025). Subsequently, blastP (E-value < 1 × 10−5) was performed using FMD’s whole-genome proteome to obtain candidate protein sequences. In order to identify TMD and NBD domains, the program Pfam (http://pfam-legacy.xfam.org/, accessed on 8 May 2025) was used to identify the ABC gene family of the FMD [35]. These models were then utilized within the TBtools software (version 2.082) [36] to screen for ABC transporters in FMD. Finally, the conserved domains of all identified protein sequences were confirmed using the CDD database [37] and SMART technology [38] to further screen and identify members of the ABC transporters gene family in FMD.

2.2. Physical and Chemical Properties Analysis of MbABC Proteins

The ExPASy ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 12 May 2025) was used to determine the physicochemical properties. To examine the signal peptides, we used SignalP-4.1 Server (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-4.1/, accessed on 13 May 2025), while subcellular localization was predicted using the WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/, accessed on 13 May 2025).

2.3. Phylogenetic Tree Analysis of MbABC Proteins

All available ABC transporter protein sequences of 40 B. taurus, 42 Ca. hircus, and 48 O. aries were retrieved from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 25 November 2025) and used for the phylogenetic analyses. The protein sequences were used in the phylogenetic tree which was analyzed using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method based on bootstrap sampling in MEGA software (version 12), with a bootstrap method of 1000. The parameters were as follows: Jones–Taylor–Thornton (JTT) model; Gamma Distributed (G); partial deletion 95%; 1000 bootstrap replications. The phylogenetic tree was visualized using the Interactive Tree of Life (iToL) (https://itol.embl.de/, accessed on 30 November 2025).

2.4. Structure Prediction of MbABC Proteins

The secondary structure of MbABC gene protein was predicted using the PRABI-GERLAND (https://npsa.lyon.inserm.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_sopma.html, accessed on 14 May 2025). The tertiary structure of the MbABC genes protein using the SWISS-MODEL to visualize (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/, accessed on 16 May 2025) [39].

2.5. Conserved Motifs and Gene Structures Domain Analysis of MbABC Proteins

The conserved motifs of MbABC proteins were predicted using MEME, setting the maximum modulus value to 8 and the rest of the parameters to default values (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme, accessed on 25 May 2025). The meme prediction results of the sequences, the gene structure and the structure with were integrated and visualized using TBtools software.

2.6. Chromosome Localization and Collinearity Analysis of MbABC Proteins

Based on the whole genome annotation files, chromosomal localization information of ABC gene family was extracted, including gene ID, chromosomal location and corresponding chromosome length. Subsequently, TBtools was used to visualize and present the physical distribution of ABC genes on M. berezovskii chromosomes.

The whole genome sequence of domestic cattle, sheep, goat, water buffalo, yak, and red deer were obtained from the Ensembl Ftp database (https://ftp.ensembl.org/, accessed on 3 June 2025). TBtools was used to obtain the collinearity relationships among FMD, B. taurus, O. aries, Ca. hircus, Bu. bubalis, B. grunniens, and Ce. elaphus. The syntenic and homology relationships between the studied species were analyzed and visualized using TBtools.

2.7. KEGG and GO Enrichment Analysis of MbABC Proteins

The protein sequences of MbABC genes family were annotated on EGGNOG-mapper database (http://eggnog6.embl.de/, accessed on 8 June 2025). The selected MbABC genes family members were enriched in GO and KEGG database. The threshold for significant enrichment is set to p < 0.05.

2.8. Protein–Protein Interaction Network Analysis of MbABC Proteins

To investigate protein–protein interactions, we used the String online database (https://cn.string-db.org/, accessed on 8 June 2025). The protein–protein interaction network was visualized using Cytoscape software (version 3.10.3).

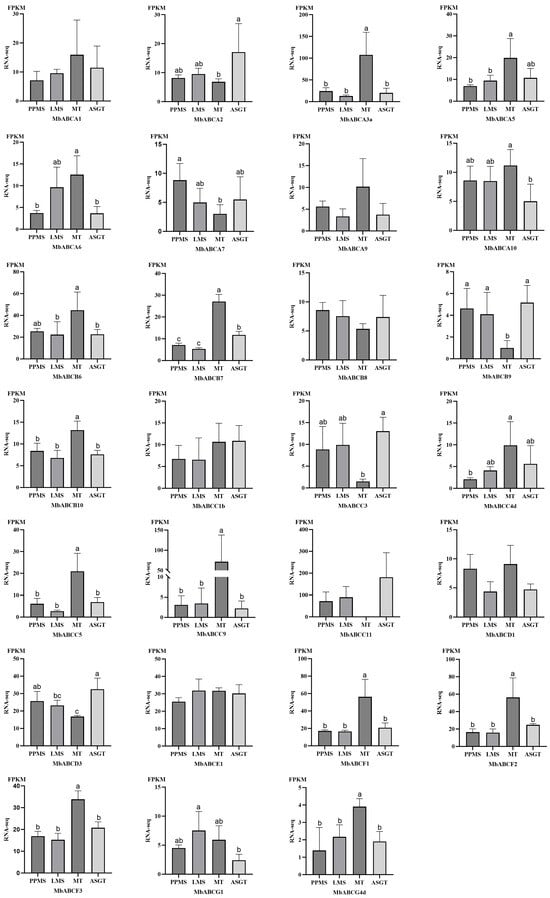

2.9. Analysis of the Expression of ABCs in Different Stages and Tissues of MbABC Proteins

Musk gland tissues from different developmental stages of the forest musk deer were sent for standard transcriptome sequencing (detailed protocol is provided in the Supplementary Materials). We utilized TBtool to extract the expression levels of MbABC genes across four conditions: the peak secretion phase, late secretion phase, muscle tissue, and adult musk gland tissue. The FPKM values were used to analyzed for gene expression level. The data were then analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS (version 26), with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Finally, the results were visualized using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.1.2).

2.10. RT-qPCR Analysis of MbABC Proteins

To evaluate the biological function of the MbABC gene, in vitro-adapted forest musk gland cells were cultured in two phases: non-secretory and stimulated secretion. The musk gland cells and agonist were purchased from Beijing Yanshe Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The company indicated that adding this agonist to the culture medium would advance the musk gland cells from the non-secretory phase to the secretory phase. First, primary forest musk gland cells were cultured at incubator with 37 °C, 5% CO2. Upon achieving stability after two passages, the cells were segregated into two experimental groups: a control group and an agonist-stimulated group, each consisting of six 225 cm2 culture flasks. At a confluence of approximately 80%, corresponding to a cell density of 1 × 106 per flask, the respective treatments were administered. The control group was cultured in unchanged medium for 24 h, whereas the stimulated group received fresh medium containing the agonist for the same duration, after which cells were harvested for RNA extraction.

Total RNA was extracted strictly according to the GOONIE Cell/Tissue RNA Extraction Kit (Cat#400-105, Guangdong, China), with concentration determined via micro-spectrophotometry. Reverse transcription was performed using the GOONIE Fast First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Mix for RT (with dsDNase) kit (Cat#500-101). RT-qPCR was conducted using the GOONIE Fast Tap SYBR Green qPCR Mix kit (Cat#500-100). The RT-qPCR mixture contained 2 μL cDNA, 10 μL SYBR Green Fast Tap Mix, 0.4 μL of each primer, and 7.2 μL nuclease-free water. The reaction was cycled at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Perform one melting curve cycle run at 95 °C. All temperatures and durations were set to instrument defaults. The fragments were amplified using specific primers that were designed using an online toolkit from the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/, accessed on 16 August 2025). The 2−∆∆Ct method [40] was applied to calculate the relative expression levels of MbABCs, with three biological replicates for each treatment. The mean ± SE of three tests was presented in the data. Three biological replicates were used for each experiment, and differences in data between the two groups used for comparison were rated as statistically significant (* p < 0.05) or extremely significant (**** p < 0.0001). The primers for RT-qPCR assays are shown in Table S1.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Chromosomal Localization Analysis of MbABC Proteins

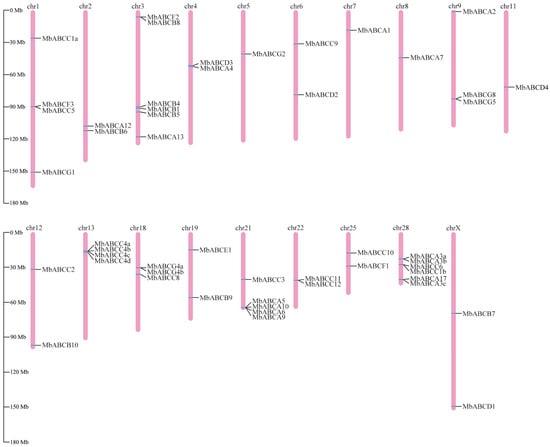

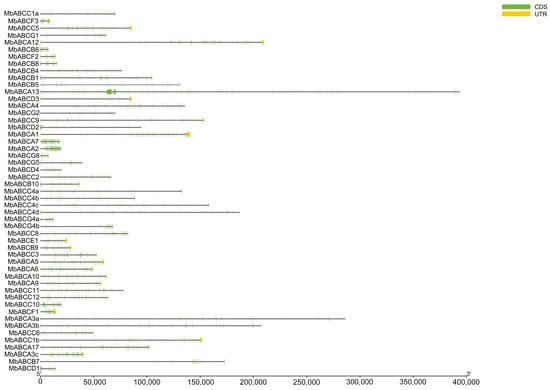

In this study, we conducted a whole-genome analysis to identify members of the ABC transporter family in FMD, combined with the conserved domain information predicted by NCBI CDD and Pfam, sequences lacking annotation information and conserved domains were excluded. At the whole-genome level, 51 ABC genes were identified in FMD. These genes were distributed across seven subfamilies (ABCA-ABCG). Chromosome mapping of these genes revealed an uneven distribution across 19 chromosomes in FMD (Figure 1). Some genes from the ABCA, ABCC, and ABCG subfamilies may have undergone tandem duplication during evolution. The ABC protein-encoding sequences demonstrated significant differences, with CDs lengths ranging from 7296 to 393,457 bp. Based on protein domains, they are classified into 27 full-size transporters, 21 half-size transporters, and three soluble transporters (Table S2).

Figure 1.

Chromosomal location distribution of MbABC proteins.

3.2. Physicochemical Analysis of MbABC Proteins

The physicochemical properties analysis of ABC transporter proteins in FMD is provided (Table S3). There are significant differences in the physicochemical properties among family members. The ABC protein with amino acid lengths ranging from 569 to 5246 residues, with members exceeding 1000aa accounting for 60.1% of the total. The molecular weights range from 63 to 590 kDa. Furthermore, the theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of the ABC proteins ranges from 5.54 to 9.84, with 32 members having a pI greater than 7, representing 62.7% of the total. The stability of a protein is indicated by its instability index, where a value less than 40 suggests that the protein is stable; whereas a value greater than 40 implies that the protein may be unstable. Within the proteins, 56.8% of the members are stable proteins, and 72.5% are hydrophobic proteins. Notably, subcellular localization analysis revealed that the ABC proteins were primarily located in the plasma membrane, nucleus, cytoplasm, and mitochondria.

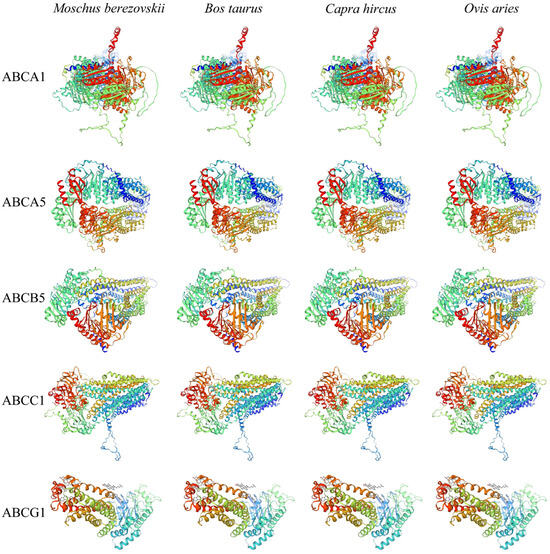

3.3. Secondary Structure and Tertiary Structure Models of MbABC Proteins

The secondary structure prediction (Table S4) indicates that alpha helix structure accounts for the largest proportion, ranging from 62.03% (MbABCA13) to 38.73% (MbABCE1). The second most abundant structure is the random coil, with a proportion ranging from 41.41% (MbABCG4b) to 23.57% (MbABCB9). This indicates that alpha helix and random coils play a major role in the formation of the tertiary structure of FMD. Homology modeling is an important technique in structural biology [39]. To gain insight into the structural characteristics of the MbABC proteins, we selected one protein from each group of FMD, cattle, goat, and sheep. Then, we generated a three-dimensional protein model using SWISS-MODEL. The results showed that ABCA1, ABCA5, ABCB5, ABCC1, and ABCG1 proteins had similar structures in different species (Figure 2). Collectively, the proteins from different species within the same subfamily exhibited considerable differences, whereas those from different subfamilies within the same species exhibited considerable differences. This result revealed the structural diversity of the ABC family in the four species. The study suggests that the ABC transporter family exhibits structural diversity among different species, further speculating that the gene-encoded structures of these proteins may be closely related to their biological functions.

Figure 2.

Predictive structure of ABC proteins in FMD, B. taurus, O. aries, and Ca. hircus.

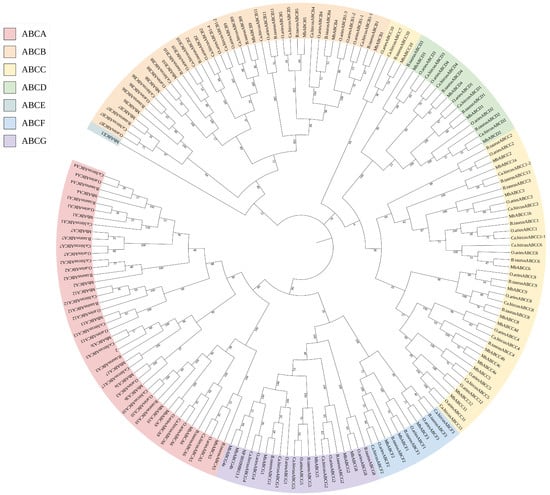

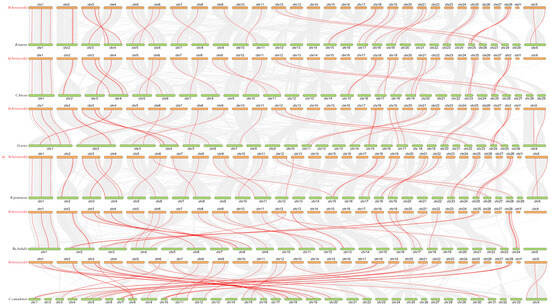

3.4. Phylogenetic Relationship and Collinearity Analysis of ABC Gene Family

It is well known that gene family members are known to originate from a common ancestral gene. Therefore, we selected three mammalian species—B. taurus, O. aries, and Ca. hircus whose ABC gene subfamily classifications are comparable to that of M. berezovskii. We then identified ABC subfamily protein sequences from each species (Table S5, Figure 3) and constructed pairwise collinearity maps between FMD and six other ruminants: B. taurus, O. aries, Ca. hircus, Bu. bubalis, B. grunniens, and Ce. elaphus (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of ABC transporter proteins: A phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA12 software with full-length amino acid sequences of FMD, B. taurus, O. aries, and Ca. hircus.

Figure 4.

Collinearity analyses of the ABC gene family in FMD, B. taurus, O. aries, Ca. hircus, Bu. bubalis, B. grunniens, and Ce. elaphus. Each horizontal line represents a chromosome, and the numbers represent chromosome numbers. The red lines indicate collinear gene pairs.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that ABC genes from FMD consistently clustered closely with their orthologs from the other mammals within each subfamily tree. Notably, genes from the same ABC subfamily across different species exhibited closer phylogenetic relationships than genes within the same species, demonstrating subfamily-specific conservation during evolution and indicating higher sequence homology among orthologous subfamily members.

Genome collinearity analysis demonstrated substantial chromosomal correspondence and orthologous conservation between the FMD and B. taurus, O. aries, Ca. hircus, Bu. bubalis, B. grunniens, and Ce. elaphus (Figure 4). FMD had 36 collinearities with B. taurus, 35 collinearities with O. aries, and 35 collinearities with Ca. hircus, 38 collinearities with Bu. bubalis, 38 collinearities with B. grunniens, and 38 collinearities with Ce. elaphus. The level of chromosome homology is relatively low, but the level of genome homology is relatively high among these species. In addition, collinearity modules explained the difference in the position of the ABC transporter gene family in FMD relative to the other five species in bovinae and the one species in Cervidae. Most of the ABC genes are distributed on different chromosomes between FMD and other six species, which may be caused by inter-chromosomal rupture or fusion during the evolution. MbABC12 and MbABCB6 are distributed on Chr2 with other five species. MbABCC1a, MbABCF3, MbABCC5, and MbABCG1 are distributed on Chr1, except for Ce. elaphus. MbABCB7 and MbABCD1 are distributed on ChrX between FMD and B. taurus, O. aries, Ca. hircus, Bu. bubalis, and Ce. elaphus. However, the lack of collinearity between MbABCB7 and MbABCD1 in Ca. hircus and B. grunniens may have resulted from changes occurring during the evolutionary process.

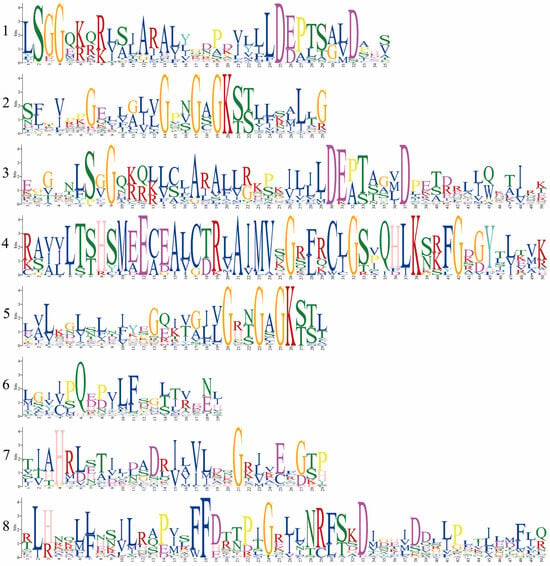

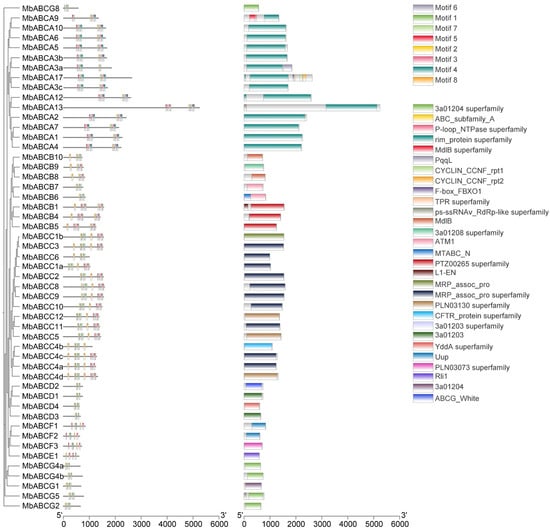

3.5. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis of MbABC Proteins

To characterize the putative motifs in MbABC proteins, we submitted the predicted amino acid sequences of the 51 MbABC proteins to the MEME website. The distribution of these motifs in MbABC is shown in Figure 5. To gain insight into the gene structure and evolutionary relationships among members of MbABC proteins (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The motif distribution patterns of MbABC proteins in the same subfamily were similar, indicating that these proteins may have similar functions. The number of conserved motifs in MbABC gene family varied from 3 to 8. Among them, Motif3, motif4, and motif8 was the longest at 50 amino acids, and Motif6, Motif1, Motif7, Motif5, and Motif2 having the highest frequency occurrence across all genes. Motif 6 and 1 were present in each subfamily, with the ABCA and ABCC subfamilies having high number of motifs. Exon–intron structure analysis revealed that MbABC genes have numerous exons. Overall, the organization of probably conserved motifs revealed a correlation with the distinct grouping of ABCs, which may be the cause of the functional specialization of MbABCs in various subfamilies.

Figure 5.

Eight conserved motifs of MbABC proteins.

Figure 6.

Conserved domain and conserved motifs of MbABC proteins.

Figure 7.

Gene structures analysis of MbABC proteins. Exons and UTR are denoted by green and yellow boxes.

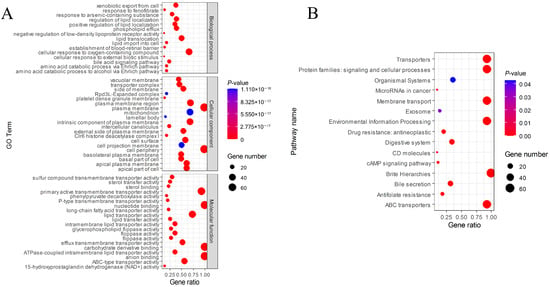

3.6. KEGG and GO Enrichment Analysis of MbABC Proteins

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis predicted was further subdivided into 55 sub-categories (Figure 8A). Under the biological process category, the cellular response to oxygen-containing compound subcategory was the most abundant. Among the assignments made to the cellular component category, a large proportion of the sequences were involved in plasma membrane and cell periphery subcategories. In the molecular function category, the majority of the unigene were grouped into nucleotide binding, carbohydrate derivative binding, and anion binding subcategories. KEGG classification indicated that the largest gene ratio is brite hierarchie subgroup, followed by the transports, protein families: signaling and cellular processes, membrane transport, environmental information processing, and ABC transports (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

KEGG and GO enrichment analysis of MbABC proteins. (A) GO enrichment analysis; (B) KEGG enrichment analysis.

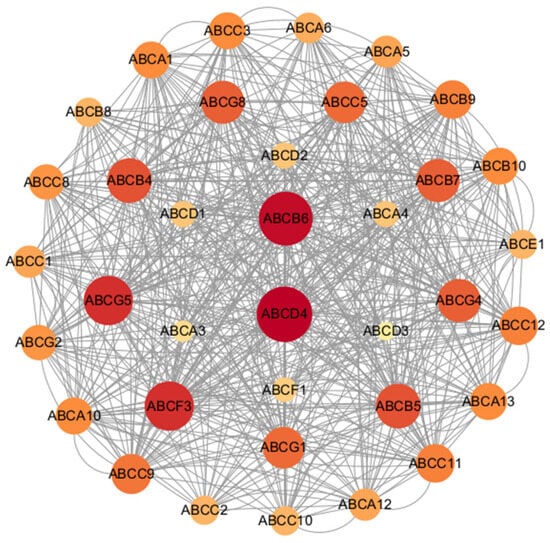

3.7. Protein–Protein Interaction Network Analysis of MbABC Proteins

We constructed protein–protein interaction (PPI) network for MbABC proteins (Figure 9). Leveraging evidence from text mining, co-expression, homology, and experiments, we constructed a protein interaction network comprised of 36 nodes (proteins) and 598 edges (interactions). Furthermore, protein–protein interactions were also observed between different members of the MbABC family, such as MbABCD4, MbABCB6, MbABCF3, and MbABCG5, suggesting potential functional collaborations among MbABC proteins. The highly significant PPI enrichment p-value (p < 0.05) indicates that the network is not random and exhibits strong biological relevance, suggesting the involved proteins collectively participate in a spectrum of related physiological pathways.

Figure 9.

Protein interactions network diagram of MbABC proteins. The protein–protein interaction network of MbABCs: The online webserver STRING was used to annotate the potential MbABCs network, with M. berezovskii as input.

3.8. Expressive Analysis of the of ABCs in Different Stages and Tissues of FMD

To investigate the tissue-specific expression of gene members within the ABC transporter family in FMD, we studied the relative expression patterns specifically including incense gland tissue at the peak period of musk secretion (PPMS), the late stage of musk secretion (LMS), muscular tissue (MT), and adolescent gland tissue (MSGT) (Figure 10). They were analyzed and fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) expression values were used to construct a digital expression level. Results indicate that MbABCA3a, MbABCA5, MbABCB6, MbABCB7, MbABCC9, MbABCC11, MbABCF1, and MbABCF2 exhibit significant differences, whereas MbABCA1, MbABCA9, MbABCB8, MbABCC1a, and MbABCE1 show no significant differences. During the peak period of musk secretion, MbABCC11 exhibited the highest relative expression level (71), followed by MbABCA3a, MbABCE1, MbABCD3, and MbABCB6, indicating these genes may play crucial roles during musk secretion. During the late musk secretion phase, MbABCC11, MbABCE1, and MbABCD3 maintained high relative expression levels. MbABCA3a exhibited the highest relative expression in muscle tissue (107), followed by MbABCC9, MbABCF2, MbABCB6, and MbABCB7. In conclusion, significant differences exist in the expression of ABC transporter genes across different tissues, suggesting that distinct members may perform unique functions during various stages of musk deer growth and development and in different tissues.

Figure 10.

Tissue-specific differential expression of MbABC proteins. Data represent the means ± SE. “a, b, c”, p < 0.05.

3.9. Expression Analysis of MbABC Genes by RT-qPCR

For the non-secreted period (Control) and stimulated (Treated) period of musk gland cells, we conducted RT-qPCR to examine the expression levels of 14 ABC genes (Figure 11). The results revealed that MbABCA1, MbABCA5, MbABCB8, MbABCB6, MbABCB7, MbABCB10, MbABCC3, MbABCC5, MbABCF1, MbABCF2, MbABCF3, and MbABCC4d had expression levels greater in the stimulated period of musk gland cells than that in the non-secreted period of musk gland cells. MbABCC4d (~twelve-fold) had the highest expression level in the stimulated period of musk gland cells, followed by MbABCC3 (~six-fold), MbABCB7 (~five-fold), MbABCB6(~three-fold), and MbABCC5(~three-fold). In summary, ABC family members were involved in the stimulated period of musk gland cells and exhibited significant differential expression across different stages, with MbABCC4d, MbABCC3, MbABCB7, MbABCB6, and MbABCC5 potentially playing crucial roles in regulating lipid droplet formation and enhancing muscone content.

Figure 11.

Expression analysis of ABC family genes under abiotic treatment via RT-qPCR in musk gland cells. *, p < 0.05; ****, p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

4. Discussion

The ABC transporter superfamily represents one of the most ancient and evolutionarily conserved protein families, facilitating the ATP-dependent translocation of a diverse array of substrates across biological membranes [41]. With the advent and refinement of high-throughput sequencing technologies, genomic data for an increasing number of species have become available, significantly expanding our capacity to identify and characterize gene families, including ABC transporters, across the tree of life. Their remarkable conservation underscores fundamental cellular roles. To date, comprehensive identification of ABC gene family has been accomplished in various model and non-model organisms, revealing notable variation in family size: H. sapiens has 49 ABC genes [32,33], M. musculus has 53 ABC genes [42], Arabidopsis thaliana has 130 ABC genes [43], Caenorhabditis elegans has 55 ABC genes [42]. In the study, we systematical identified 51 ABC transporter genes from the chromosome-level genome of FMD. Phylogenetic classification based on sequence homology and structural architecture has consistently grouped ABC transporters into eight subfamilies (ABCA-ABCH) [11,44]. Subfamilies ABCA through ABCG are ubiquitous in both vertebrates and invertebrates. In contrast, the ABCH subfamily exhibits a more restricted phylogenetic distribution, having been confirmed at the genomic level in teleost fish (e.g., zebrafish, pufferfish), insects (e.g., Drosophila melanogaster, Bombyx mori) [44,45,46], and the amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum [47]. Generally, the ABC transporter complement is relatively conserved among vertebrates but demonstrates considerable diversity within arthropods. For instance, arthropods and mollusks often possess a larger number of ABCG subfamily members compared to vertebrates. While some fish and mollusks contain harbor only a single ABCH, arthropods typically contain multiple. Intriguingly, the citrus mealybug possesses four ABCF genes, whereas three is the typical number in most other animals. Analysis of ABCD, ABCE, and ABCF subfamily numbers in M. berezovskii, Ca. hircus, O. aries, and B. taurus (Table S5) revealed a high degree of conservation. Notably, the numbers of ABCG subfamily members in FMD is similar to that in I. punctatus, D. rerio, and Oreochromis aureus, and is higher than in bovid species.

Structurally, ABCA and ABCC subfamilies consist predominantly of full transporters, while ABCD, ABCG, and ABCH are composed of half transporters that must dimerize to form functional units. The ABCB subfamily uniquely contains both half and full transporters. In contrast, ABCE and ABCF subfamilies members contain paired NBDs but lack TMDs, thus lacking transmembrane translocation capacity and are not considered bona fide transporters [48]. However, their NBDs phylogenetically cluster with those of other ABC genes, indicating a conserved evolutionary relationship [17]. Phylogenetic analyses further suggest a close evolutionary relationship between the ABCH and ABCG subfamilies.

Gene duplication events have been pivotal in the expansion and functional diversification of ABC genes. It has been reported that ABCB1 gene undergone duplication to give rise to the ABCB4 and ABCB1 genes in rodents and opossums [9]. The presence of ABCB1 and ABCB4 in amphibians and reptiles indicates that these genes likely originated prior to the mammalian-reptilian divergence, a finding that refines previous evolutionary models [9,49]. Subcellular localization predictions for the MbABC proteins indicated that over half are localized to the plasma membrane. Based on sequence characteristics, we classified the MbABC proteins into seven subfamilies: ABCA-ABCG. The PPIs are crucial for understanding complex traits [50]. Our prediction the PPIs network for MbABC proteins, comprising 36 MbABC proteins with 80 nodes in total. Identified ABCB6 and ABCD4 as potential hub genes, offering valuable insights for future studies.

The ABC transport genes are often unevenly distributed across chromosomes, a pattern observed in M. berezovskii, C. hanglu yarkandensis, I. punctatus, D. rerio, O. aureus, and various bovids. This non-uniform distribution is likely a consequence of lineage-specific gene duplication events, such as tandem duplications [51,52]. In M. berezovskii, MbABCC genes were predominantly located on chromosomes 1, 13, and 22, while the MbABCG genes were clustered on chromosomes 9 and 18, suggesting subfamily expansion via gene duplication. We identified several tandemly arrayed gene clusters, including MbABCG5/MbABCG8 on chromosome 9, MbABCC4a, MbABCC4b, and MbABCC4c on chromosome 13, MbABCG4a/MbABCG4b on chromosome 18, and MBABCA clusters on chromosome 21 and 28. MbABCC1b/MbABCC6 on chromosome 28. These tandem repeats appear to be a major mechanism for ABC gene family expansion in the forest musk deer. Furthermore, comparative genomic analysis revealed numerous syntenic blocks of ABC genes between forest musk deer and related artiodactyls (B. taurus, Ca. hircus, O. aries, Bu. bubalis, B. grunniens, and Ce. elaphus), with collinear genes pairs ranging from 35 to 38, highlighting the conservation of genomic context.

ABC transporters facilitate the transport of an exceptionally wide spectrum of substrates, including ions, organic molecules, peptides, complex lipids, and small proteins [53]. In mammals, ABCA subfamily members are critical involved in lipid homeostasis. ABCA1, ABCA2, ABCA3, and ABCA7 mediate the efflux of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids [54]. Cytochrome transport precursors also depend mainly on the ABCG subfamily [55]. The ABCA1 proteins are involved in the transport of cholesterol [56,57,58]. The ABCA4 protein, specific to the photoreceptor cells, transport retinoid–lipid complexes [59,60]. Orthologs of ABCA1 and ABCA4 genes were identified in the FMD and three bovine (B. taurus, O. aries, Ca. hircus) genomes. ABCB1 exhibits broad substrate specificity, effluxing xenobiotics and toxic metabolites [44]. The ABCB2 (TAP1) and ABCB3 (TAP2) are transporters associated with antigen processing. ABCB4 proteins phosphatidylcholine into bile [9], and its absence in bony fish leads to a phospholipid-deficient bile [44]. ABCB5 gene is highly expressed in melanocytes [9], and ABCB6 functions as a mitochondrial porphyrin transporter essential for heme biosynthesis [61,62], suggesting a potential detoxification role this gene in moschidae, cervidae, and bovid species. Most ABCC proteins export conjugated compounds and toxins. ABCF members are involved in ribosome assembly and protein translation control [17]. ABCG1 and ABCG4 contribute to cellular cholesterol and phospholipids efflux [63], while ABCG5 and ABCG8 dimerize to mediate sterols excretion in the intestinal and biliary [18]. The known functions of these subfamilies, particularly in lipid and sterol transport, provide a compelling mechanistic framework for hypothesizing their role in the secretion of musk components, which include numerous lipid-derived and sterol-like compounds.

Tissue-specific expression analysis revealed that during the peak period of musk secretion, the FMD, multiple ABC subfamilies exhibited highly expressed genes, such as MbABCA3a, MbABCB6, MbABCC11, MbABCD3, MbABCE1, MbABCF1, MbABCF2, and MbABCF3. However, different ABC subfamilies perform distinct functions within cells. We hypothesize that secondary metabolites or other precursor substances generated during the complex biochemical reactions occurring in the FMD during the musk secretion period undergo continuous biochemical transformations within the animal’s body before being ultimately transported to the musk gland to produce musk.

Our expression analysis provides crucial functional insights linking specific MbABC genes to musk secretion physiology. The RT-qPCR revealed that 12 MbABC genes were significantly up-regulated during musk secretion, suggesting potential roles beyond classic transport, possibly in local nutrient or signaling molecule flux. ABC transporters are responsible for transport functions within cells, facilitating the movement of steroids, lipids, secondary metabolites, and other substances. Beijing Yanshe Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) posits that under agonist stimulation, musk gland cells prematurely enter the secretion phase, producing lipid droplets that are further converted and synthesized into musk. Through RT-qPCR analysis, MbABCC3 and MbABCC4d have up-regulated expression. This suggests that ABC genes may promote the synthesis and transport of lipids or other substances in musk gland cells under these conditions. During musk secretion, genes involved in steroid hormone synthesis play a crucial role and are associated with signal transduction [34,64], and ABCA and ABCC subfamilies participate in this process. Additionally, other ABC subfamily genes may contribute to varying degrees in the musk secretion process of the FMD. These results can provide a reference for researching the response mechanisms of ABC genes to the secretion process of FMD. However, the specific molecular mechanisms need to be further studied.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study presents the first genome-wide identification and characterization of the ABC transporter gene family in the FMD. We identified 51 ABC transporter genes, classified them into seven subfamilies (ABCA-ABCG), and mapped their locations across 19 chromosomes. Sequence analysis revealed considerable variation in mRNA length, with the ABCA subfamily being particularly distinct. Physicochemical property analysis indicated that MbABC proteins are generally large, with diverse isoelectric points, lower stability, higher hydrophilicity. These proteins are primarily localized to the plasma membrane and are predominantly composed of α-helices. Tertiary structure models revealed notable similarities between FMD and cattle. Collinearity analysis indicates relatively low levels of chromosomal homology among these species, but relatively high levels of genomic homology. KEGG and GO enrichment analyses confirmed the central role of MbABC genes in transport activities. Subsequent the RT-qPCR validation confirmed that several MbABC genes are up-regulated during the period of active musk secretion. These findings strongly suggest that ABC transporters play a critical role in the musk secretion process, potentially facilitating the maturation and final excretion of musk components. This study provides a valuable foundation for further elucidating the molecular mechanisms of musk secretion and contributes significantly to the scientific basis for the conservation and sustainable utilization of this endangered species.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ani15243630/s1, File S1: RNA-Seq SOP. Table S1: The primer sequences of MbABC. Table S2: Gene-wide identification of ABC transporter proteins in M. berezovskii. Table S3: Protein haracteristics analysis of ABC transporter proteins in M. berezovskii. Table S4: Secondary structure and percentage of ABC transporter proteins in M. berezovskii. Table S5: The distribution of ABC numbers in FMD, Bos taurus, Capra hircus, Ovis aries, Bos mutus, Bubalus bubalis, and Cervus elaphus. Table S6: Sequence list of the ABC genes identified from H. sapiens, M. musculus, B. taurus, Ca. hircus, O. aries and D. rerio genomes. Refs. [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80] are cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing—original draft, Y.-Y.R.; data curation and visualization, X.-Z.Z.; formal analysis and data curation, J.-F.M.; validation, writing—review and editing, F.D.; formal analysis and investigation, X.-M.J.; supervision and resources, D.-D.L.; project administration and resources, C.-X.Y.; project administration and formal analysis, C.-L.Z.; resources, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing, and funding, W.-H.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (No. KJZD-K202401203), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (No. CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0123), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. NSFC32370560).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Three Gorges University and Beijing Yanshe Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. (CTGU2025-06). Ethical approval date: 5 June 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Mendeley Data at https://data.mendeley.com/preview/dvcybyfztv?a=e4a930f8-6adf-4616-873e-c1bae4fa8aff, accessed on 12 December 2025.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xian An at Beijing Yanshe Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. for assisting with the study. The authors thank Shanghai Origingene at Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. for providing the sequencing and bioinformatics service for the sequencing and technical support for the project.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Dan-Dan Liao and Cong-Xue Yao were employed by the company Beijing Yanshe Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Caetano-Anollés, D.; Kim, K.M.; Mittenthal, J.E.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Proteome evolution and the metabolic origins of translation and cellular life. J. Mol. Evol. 2011, 72, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. ABC Family Transporters. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1141, 13–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenstein, K.; Frei, D.C.; Locher, K.P. Structure of an ABC transporter in complex with its binding protein. Nature 2007, 446, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, G.F.; Mimura, C.S.; Holbrook, S.R.; Shyamala, V. Traffic ATPases: A superfamily of transport proteins operating from Escherichia coli to humans. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1992, 65, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.H.T.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y.; Hwang, J.U. 2021 update on ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters: How they meet the needs of plants. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1876–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenstein, K.; Dawson, R.J.; Locher, K.P. Structure and mechanism of ABC transporter proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007, 17, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, D.C.; Johnson, E.; Lewinson, O. ABC transporters: The power to change. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzendorfer, H. Chapter One—ABC Transporters and Their Role in Protecting Insects from Pesticides and Their Metabolites. In Advances in Insect Physiology; Cohen, E., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Volume 46, pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Annilo, T.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Shulenin, S.; Costantino, J.; Thomas, L.; Lou, H.; Stefanov, S.; Dean, M. Evolution of the vertebrate ABC gene family: Analysis of gene birth and death. Genomics 2006, 88, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, T.S.; Rempe, C.S.; Davitt, J.; Staton, M.E.; Peng, Y.; Soltis, D.E.; Melkonian, M.; Deyholos, M.; Leebens-Mack, J.H.; Chase, M.; et al. Diversity of ABC transporter genes across the plant kingdom and their potential utility in biotechnology. BMC Biotechnol. 2016, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Rzhetsky, A.; Allikmets, R. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Genome Res. 2001, 11, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovic, M.; Zaja, R.; Loncar, J.; Smital, T. A novel ABC transporter: The first insight into zebrafish (Danio rerio) ABCH1. Mar. Environ. Res. 2010, 69, S11–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, C.; Viturro, E. The ABCA subfamily—Gene and protein structures, functions and associated hereditary diseases. Pflügers Arch.-Eur. J. Physiol. 2007, 453, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhuri, S.; Klaassen, C.D. Structure, function, expression, genomic organization, and single nucleotide polymorphisms of human ABCB1 (MDR1), ABCC (MRP), and ABCG2 (BCRP) efflux transporters. Int. J. Toxicol. 2006, 25, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, D. Multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs, ABCCs): Importance for pathophysiology and drug therapy. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marcos Lousa, C.; van Roermund, C.W.T.; Postis, V.L.G.; Dietrich, D.; Kerr, I.D.; Wanders, R.J.A.; Baldwin, S.A.; Baker, A.; Theodoulou, F.L. Intrinsic acyl-CoA thioesterase activity of a peroxisomal ATP binding cassette transporter is required for transport and metabolism of fatty acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyzack, J.K.; Wang, X.; Belsham, G.J.; Proud, C.G. ABC50 Interacts with Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 and Associates with the Ribosome in an ATP-dependent Manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 34131–34139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusuhara, H.; Sugiyama, Y. ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G (ABCG family). Pflugers Arch. 2007, 453, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berge, K.E.; Tian, H.; Graf, G.A.; Yu, L.; Grishin, N.V.; Schultz, J.; Kwiterovich, P.; Shan, B.; Barnes, R.; Hobbs, H.H. Accumulation of Dietary Cholesterol in Sitosterolemia Caused by Mutations in Adjacent ABC Transporters. Science 2000, 290, 1771–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, P.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; An, X.; Yao, C.; Xu, L.; Xu, Y.; Liu, S. Analysis and comparison of blood metabolome of forest musk deer in musk secretion and non-secretion periods. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, W.-X.; Li, L.-H.; Liu, B.-Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, S.-Q.; Qi, L.; Hu, D.-F. Effects of crowding and sex on fecal cortisol levels of captive forest musk deer. Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xie, L.; Deng, M.; Zhang, X.; Luo, J.; Li, X. Zoology, chemical composition, pharmacology, quality control and future perspective of Musk (Moschus): A review. Chin. Med. 2021, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, B.; Zhang, L.; Gaur, U.; Ma, T.; Jie, H.; Zhao, G.; Wu, N.; Xu, Z.; Xu, H.; et al. The musk chemical composition and microbiota of Chinese forest musk deer males. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, V.E.; Kagan, M.Z.; Vasilieva, V.S.; Prihodko, V.I.; Zinkevich, E.P. Musk deer (Moschus moschiferus): Reinvestigation of main lipid components from preputial gland secretion. J. Chem. Ecol. 1987, 13, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzicka, L. Zur Kenntnis des Kohlenstoffringes VII. Über die Konstitution des Muscons. Helv. Chim. Acta 1926, 9, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Meng, X.; Xia, L.; Feng, Z. Conservation status and causes of decline of musk deer (Moschus spp.) in China. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 109, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, M.N. Animal welfare in the musk deer. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 59, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Ha, C.-Y. Research progress on musk and artificial propagation technique of forest musk deer. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2018, 43, 3806–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Chung-Davidson, Y.W.; Yeh, C.Y.; Scott, C.; Brown, T.; Li, W. Genome-wide analysis of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter gene family in sea lamprey and Japanese lamprey. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z. Genome-wide identification, characterization and phylogenetic analysis of 50 catfish ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter genes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schriml, L.M.; Dean, M. Identification of 18 mouse ABC genes and characterization of the ABC superfamily in Mus musculus. Genomics 2000, 64, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almén, M.S.; Nordström, K.J.V.; Fredriksson, R.; Schiöth, H.B. Mapping the human membrane proteome: A majority of the human membrane proteins can be classified according to function and evolutionary origin. BMC Biol. 2009, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, A.Y.; Liu, Q.-R.; Li, C.-Y.; Zhao, M.; Qu, H. Human Transporter Database: Comprehensive Knowledge and Discovery Tools in the Human Transporter Genes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hong, T.; Yu, L.; Chen, Y.; Dong, X.; Ren, Z. Single-nucleus multiomics unravels the genetic mechanisms underlying musk secretion in Chinese forest musk deer (Moschus berezovskii). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; et al. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.; Milpetz, F.; Bork, P.; Ponting, C.P. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: Identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 5857–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chakrabarty, S.; Jin, M.; Liu, K.; Xiao, Y. Insect ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporters: Roles in Xenobiotic Detoxification and Bt Insecticidal Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheps, J.A.; Ralph, S.; Zhao, Z.; Baillie, D.L.; Ling, V. The ABC transporter gene family of Caenorhabditis elegans has implications for the evolutionary dynamics of multidrug resistance in eukaryotes. Genome Biol. 2004, 5, R15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrier, P.J.; Bird, D.; Buria, B.; Dassa, E.; Forestier, C.; Geisler, M.; Klein, M.; Kolukisaoglu, Ü.; Lee, Y.; Martinoia, E.; et al. Plant ABC proteins—A unified nomenclature and updated inventory. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Annilo, T. Evolution of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily in vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2005, 6, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C.W.; Holm, I.; Graille, M.; Dehoux, P.; Rzhetsky, A.; Wincker, P.; Weissenbach, J.; Brey, P.T. Identification of the Anopheles gambiae ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily genes. Mol. Cells 2003, 15, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, A.; Cunningham, P.; Dean, M. The ABC transporter gene family of Daphnia pulex. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjard, C.; Loomis, W.F. Evolutionary analyses of ABC transporters of Dictyostelium discoideum. Eukaryot. Cell 2002, 1, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, I.D. Sequence analysis of twin ATP binding cassette proteins involved in translational control, antibiotic resistance, and ribonuclease L inhibition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 315, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moitra, K.; Scally, M.; McGee, K.; Lancaster, G.; Gold, B.; Dean, M. Molecular evolutionary analysis of ABCB5: The ancestral gene is a full transporter with potentially deleterious single nucleotide polymorphisms. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Zhou, Q.; He, J.; Jiang, Z.; Peng, C.; Tong, R.; Shi, J. Recent advances in the development of protein-protein interactions modulators: Mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, G.; Wu, T.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Han, Z.; Wang, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of ABC Transporters in Nine Rosaceae Species Identifying MdABCG28 as a Possible Cytokinin Transporter linked to Dwarfing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvia, C.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ntini, C.; Ogutu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Han, Y. Genome-Wide Analysis of ATP Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporters in Peach (Prunus persica) and Identification of a Gene PpABCC1 Involved in Anthocyanin Accumulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoulou, F.L.; Kerr, I.D. ABC transporter research: Going strong 40 years on. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasello, M.; Giudice, A.M.; Scotlandi, K. The ABC subfamily A transporters: Multifaceted players with incipient potentialities in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 60, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, A.S.; Wang, D.; Stock, M.; Gretscher, R.R.; Groth, M.; Boland, W.; Burse, A. Tissue-specific transcript profiling for ABC transporters in the sequestering larvae of the phytophagous leaf beetle Chrysomela populi. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oram, J.F.; Lawn, R.M. ABCA1. The gatekeeper for eliminating excess tissue cholesterol. J. Lipid Res. 2001, 42, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Liu, Y.; Kessler, P.S.; Vaughan, A.M.; Oram, J.F. The macrophage cholesterol exporter ABCA1 functions as an anti-inflammatory receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 32336–32343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvan-Charvet, L.; Wang, N.; Tall, A.R. Role of HDL, ABCA1, and ABCG1 transporters in cholesterol efflux and immune responses. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Smallwood, P.M.; Nathans, J. Biochemical defects in ABCR protein variants associated with human retinopathies. Nat. Genet. 2000, 26, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsybovsky, Y.; Molday, R.S.; Palczewski, K. The ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA4: Structural and functional properties and role in retinal disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 703, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helias, V.; Saison, C.; Ballif, B.A.; Peyrard, T.; Takahashi, J.; Takahashi, H.; Tanaka, M.; Deybach, J.C.; Puy, H.; Le Gall, M.; et al. ABCB6 is dispensable for erythropoiesis and specifies the new blood group system Langereis. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.C.; Du, G.; Fukuda, Y.; Sun, D.; Sampath, J.; Mercer, K.E.; Wang, J.; Sosa-Pineda, B.; Murti, K.G.; Schuetz, J.D. Identification of a mammalian mitochondrial porphyrin transporter. Nature 2006, 443, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarr, P.T.; Edwards, P.A. ABCG1 and ABCG4 are coexpressed in neurons and astrocytes of the CNS and regulate cholesterol homeostasis through SREBP-2. J. Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Peng, G.; Shu, F.; Dong, D.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Pan, C.; Yang, F.; et al. Characteristics of steroidogenesis-related factors in the musk gland of Chinese forest musk deer (Moschus berezovskii). J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 212, 105916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholes, A.; Lewis, J.A. Comparison of RNA isolation methods on RNA-Seq: Implications for differential expression and meta-analyses. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darzi, Y.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Yamada, T. iPath3.0: Interactive pathways explorer v3. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W510–W513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ura, H.; Togi, S.; Niida, Y. A comparison of mRNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) library preparation methods for transcriptome analysis. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.-C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, A.; Vai, S.; Caramelli, D.; Lari, M. The Illumina Sequencing Protocol and the NovaSeq 6000 System. In Bacterial Pangenomics; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2242, pp. 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mering, C.; Huynen, M.; Jaeggi, D.; Schmidt, S.; Bork, P.; Snel, B. STRING: A database of predicted functional associations between proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soneson, C.; Love, M.I.; Robinson, M.D. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: Transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Research 2016, 4, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, J.; Xue, L.; Zhao, T.; Ding, W.; Han, Y.; Ye, H. A Comparison of Transcriptome Analysis Methods with Reference Genome. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, A.; Madrigal, P.; Tarazona, S.; Gomez-Cabrero, D.; Cervera, A.; McPherson, A.; Szcześniak, M.W.; Gaffney, D.J.; Elo, L.L.; Zhang, X.; et al. A survey of best practices for RNA-seq data analysis. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Bruno, V.M.; Rasko, D.A.; Cuomo, C.A.; Muñoz, J.F.; Livny, J.; Shetty, A.C.; Mahurkar, A.; Hotopp, J.C.D. Best practices on the differential expression analysis of multi-species RNA-seq. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).