Simple Summary

This study investigated the presence of honeybee-associated viruses in the European hornet, a known bee predator. While certain viruses have been detected in other wasp species, limited data existed regarding their occurrence in European hornets. To address this gap, researchers collected 40 adult hornets from Hungary between August and October 2023 and tested them for viral infections. Molecular analysis identified genetic material from two viruses known to affect honeybees, one associated with wing deformities and another linked to paralysis. Notably, the infected hornets exhibited no visible signs of disease. This study represents the first confirmed detection of these viruses in European hornets in Hungary, contributing to a broader understanding of virus transmission across insect species. These findings highlight the ecological role of V. crabro in the spread of pollinator pathogens, threatening honeybee populations and ecosystem stability, and underscore the need for targeted monitoring and mitigation efforts.

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the presence of known bee viruses in the European hornet (Vespa crabro, Linnaeus, 1758), a species recognized as a bee predator in Hungary. Several viruses affecting honeybees (Apis mellifera, Linnaeus, 1758), such as deformed wing virus (DWV), sacbrood virus (SBV), chronic bee paralysis virus (CBPV), and acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV), have been documented in various wasp species. For instance, DWV has been frequently isolated in Vespa orientalis (Linnaeus, 1761), and ABPV has been detected in V. orientalis. Additionally, viruses like Kashmir bee virus (KBV) and Black queen cell virus (BQCV) have been confirmed in other wasp species such as Vespula germanica and Vespa velutina. Despite this, data on virus presence in V. crabro remain limited. Between August and October 2023, we tested 40 adult V. crabro workers, collected from Kiskunlacháza and Vácduka, for viral infections using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Our results confirmed the presence of genetic material from DWV and ABPV infection in adult workers of the European hornet, which showed no morphological alterations. This study provides the first detection of DWV (in Hungary) and ABPV in V. crabro, contributing to our understanding of virus transmission pathways in wasp species and their potential impact on bee populations.

1. Introduction

The European hornet (Vespa crabro, Linnaeus, 1758), one of the largest representatives of the folding-winged wasps (Vespidae) in Hungary, is a social, colony-forming wasp species widely distributed across Europe, with dense populations in certain regions [1]. These wasps initiate nest-building in the spring, with colony expansion continuing throughout the summer [2]. In autumn, only the fertilized queens hibernate over the winter period. In spring, they start building the nest. The nest, consisting of hexagonal cells, is constructed to house the larval stages of the first generation, which are nurtured for approximately 21–24 days before maturing into adult workers. After that, the pupated and mature workers assume the role of caring for the larvae, allowing the colony to grow further [2]. Essentially, they feed their larvae with other insect species, including honeybees (Apis mellifera). Towards the end of summer, they prefer the carcasses of dead animals and ripe, sweet fruits such as grapes [1].

Globally, several viral infections have been identified in honeybees, including acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV), Israeli acute paralysis virus (IAPV), Kashmir bee virus (KV), chronic bee paralysis virus (CBPV), deformed wing virus (DWV), sacbrood virus (SBV), and black queen cell virus (BQCV) [3]. These viruses, known to affect bees, have also been detected in other arthropods. For example, DWV can be detected not only in honeybees but also in many other arthropod species, including solitary (one species) and eusocial wasp species (seven species), ants (two species), butterflies (three species), and bumblebees (eleven species) [4]. Other studies have also reported the viral infection in several wasp species, which are also known as bee predators [5], with specific attention drawn to invasive wasps as vectors of these bee viruses [6]. Notably, DWV was one of the most frequently detected viruses in Vespa orientalis [7]. An examination was also carried out on the larvae of this wasp species, in which DWV was also the most frequently detected virus [8]. In one report, the clinical appearance of DWV, such as shortened and deformed wings, was also observed in Vespa crabro, and the complete genome sequence of DWV was determined [9,10].

CBPV, which occurs in apiaries worldwide, was also found in two ant species (Camponotus vagus, Scopoli, 1763; Formica rufa, Linnaeus, 1761) in addition to bees [11]. In bees, besides paralysis symptoms, this virus can also cause the loss of the hair covering of the abdomen [3]. The virus could not be detected in adult and larval wasps examined [7,8].

The presence of ABPV [3], which often causes symptomless infection in bees but can also result in wing asymmetry and paralysis, was detected with a frequency of 17.2% in larvae and 63.3% in adults of the species Vespa orientalis [7,8].

IBPV, known to cause the loss of the hair covering the abdomen and paralysis in bees, has also been found in V. velutina, a natural bee predator, with evidence suggesting the virus may replicate in this wasp species [12].

SBV, which induces molting disorders in honeybee brood, has been detected in V. orientalis with a prevalence of 34.4% in larvae and 3.3% in adults [3,7,8]. Interestingly, SBV, previously known in bees, was also detected in the species, the Giant resin bee (Megachile sculpturalis, Smith, 1853), in an Italian study [13]. BQCV, which causes the disease and death of bee broods, is widespread worldwide and was detected in 43.3% of adult V. orientalis, while in the larva stage of this wasp species, it was detected in 24.1% [3,7,8].

Kashmir bee virus (KBV), which is associated with Varroa destructor mites in domestic honeybees and is often the cause of hive depopulation, may also be present in other species [3]. Based on different studies, the virus has been identified in other species, such as the Asian hornet (Vespa velutina) in Italy and the German wasp (Vespula germanica) [14,15]. KBV is listed as a potential wasp pathogen in a New Zealand study [16]. The pathogen was detected in 3.3% of V. orientalis adults, which could not be confirmed in camouflage [7,8].

To date, references to the European hornet (Vespa crabro) being infected with pathogenic bee viruses are notably scarce in international literature. Currently, only the presence of DWV has been identified in the case of Vespra crabro in Italy. Despite growing concern over viral transmission among pollinators, evidence of pathogenic bee viruses in the European hornet remains limited. This knowledge gap limits our understanding of the species’ role in pathogen ecology.

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 40 European hornet (Vespa crabro) samples were collected in 2023 in Hungary (Kiskunlacháza and Vácduka) (Table 1). Solitaire samples were captured during their resting period on fruits at night, as the collection of live hornets during active daylight hours presents substantial safety risks. There were no known beehives or apiaries in the immediate vicinity of the sampling locations.

Table 1.

Collected samples.

The European hornet samples in 500 µL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were homogenized using a mortar and pestle. To enrich viral nucleic acids from the homogenized European hornets, samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. Viral nucleic acid was extracted from the supernatant using MagCore® Plus II instrument and MagCore® Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit (202) (RBC Bioscience, New Taipei City, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For the detection of different viruses, QIAGEN OneStep RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used with specific primer sets, listed in Table 2. The reaction was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions in a final volume of 25 µL. The reaction mixture comprised 1 µL enzyme mix, 4 U RiboLock RNase Inhibitor (Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA), the primer pair at 0.6 µM concentration, and 2 µL template RNA. The PCR cycling conditions were 50 °C for 30 min and 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; the final extension lasted for 5 min at 72 °C. Positive controls for each virus were derived from our previous study [17].

Table 2.

Primers of honeybee viruses were used for the test.

The PCR product was run on a 1.5% agarose gel (Top Vision Agarose, Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA) and stained with Invitrogen SYBR™ Safe DNA Gel Stain (Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA). The PCR product was excised and extracted from the gel using the QIAGEN QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). To confirm the results, Sanger sequencing was performed for selected samples by a third-party service provider (Eurofins Biomi Ltd., Gödöllő, Hungary).

For phylogenetic analysis, we built datasets for Deformed wing virus and Acute bee paralysis virus based on the partial sequence of RdRp. Sequence alignments were created with the MAFFT plugin of Geneious Prime® v.2024.0.5. Maximum-likelihood trees were inferred with MEGA-X, using the TN92+G model for each dataset and applying 100 bootstrap replicates [18]. Sequence identity values were calculated using Geneious Prime software v.2024.0.5.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 3 contains the results of the samples collected in our research between August and October 2023.

Table 3.

Results of PCR tests from the pooled samples in different months.

During the external morphological examination of the hornets captured for this study, no abnormal deviations were observed on the head, thorax, or abdomen, nor on the legs and wings, all of which were intact. The morphological examination ruled out macroscopic signs of DWV. The clinical examination assessed movement coordination and grooming behavior to evaluate potential effects of ABPV.

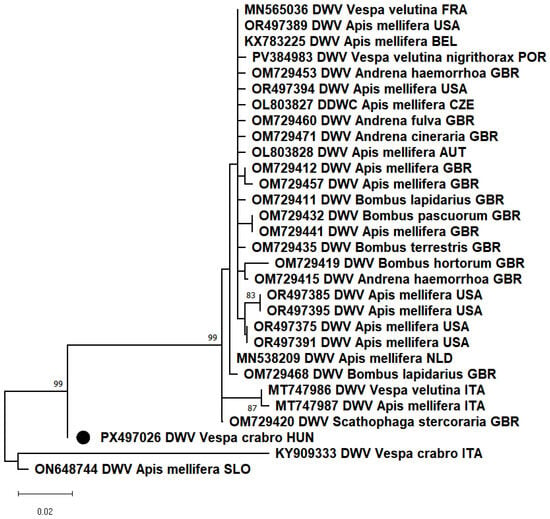

PCR results showed that most of the samples from Kiskunlacháza and Vácduka were positive for the deformed wing virus (DWV). This is the first confirmed detection of DWV in apparently healthy V. crabro workers in Hungary. Previously, such cases had only been reported in Italy [9,10]. In other studies, DWV is described as one of the most frequently isolated viruses in both adults and larvae of Vespa orientalis [7,8]. The partial RdRp segment of our sample showed 97.21% nt identity with the closest reference sequence (ON648744), which was detected in Apis mellifera from Slovenia. Our sample showed only 90.52% nt identity with the other DWV detected in Vespa crabro. In the phylogenetic analysis, the DWV_HUN-1 (PX497026) strain clustered in a separate branch (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Based on the partial nucleotide sequences of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene of deformed wing virus (DWV), a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was created with MEGA-X software, T92+G model, 100 bootstrap repetitions. The strain we have described is indicated by a black circle.

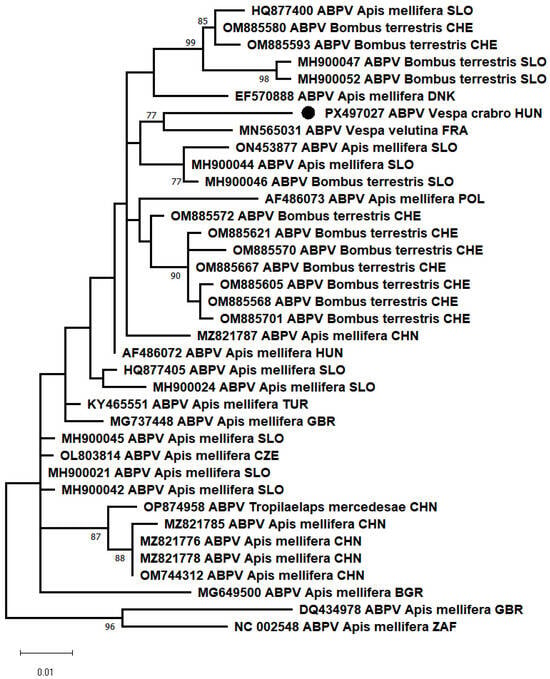

Additionally, PCR results showed that most of the samples from both collection sites were positive for the acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV), marking the first detection of ABPV in healthy V. crabro workers. In other research, the genetic material of ABPV was detected with a frequency of 17.2% in larvae and 63.3% in adults of the species Vespa orientalis [7,8]. The partial RdRp of our sample showed 97.08% nt identity with the closest reference sequence (MN565031), which was detected from the Asian hornet (Vespa velutina nigrithorax, Buysson, 1905). In the phylogenetic analysis, the ABPV_HUN-1 (PX497027) strains clustered together with the closest reference sequences (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the partial nucleotide sequences of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene of acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV), made with the MEGA-X software, T92+G model, 100 bootstrap repetitions. The strain we have described is indicated by a black circle.

DWV and ABPV infection were simultaneously detected in both collection locations (Kiskunlacháza and Vácduka) in the examined hornets. While the Kashmir bee virus (KBV) has previously been confirmed in Vespa velutina, Vespula germanica, and V. orientalis, we did not detect KBV in any of the V. crabro specimens [7,8,14,15,16]. We could not confirm the IBPV infection during the examination of our V. crabro specimens, although the presence of the virus has been reported in V. velutina, where it may even replicate [12]. BQCV has already been detected in V. orientalis imagos (43.3%) and larvae (24.1%), but we could not identify it in V. crabro workers. Furthermore, CBPV has already been detected in imagoes and larvae of two ant species (Camponotus vagus and Formica rufa) and V. orientalis; in contrast, all samples in our tests were negative [7,8,11]. Although SBV has been described in V. orientalis larvae and imagos, as well as in the species Megachile sculpturalis, we could not detect this virus in V. crabro workers [7,8,13].

The surveillance for certain viral infections, such as deformed wing virus (DWV), black queen cell virus (BQCV), acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV), sacbrood virus (SBV), chronic bee paralysis virus (CBPV), and Israeli acute paralysis virus (IAPV), was carried out in Hungarian apiaries in several years. Most recently, in the spring of 2024, screening tests were performed in 26 domestic and 3 foreign apiaries and on free-collected bee samples to identify the aforementioned virus strains [17]. However, bee predator species have not yet been examined to determine whether these species are asymptomatic carriers of the viruses. We are currently conducting a comprehensive series of diagnostic PCR tests to clarify how the European hornet (V. crabro), the most important predator of bees in Hungary, becomes infected with the most important viruses known to affect bees.

4. Conclusions

This study reports the first detection of acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV) in the European hornet (Vespa crabro) and the first record of Deformed wing virus (DWV) in this species in Hungary. Both viruses were found in adult hornets that showed no symptoms at two different locations. This suggests that V. crabro may be a silent carrier (transmitter) of honeybee-related viruses. Phylogenetic analyses showed close relationships between the viral sequences from the hornets and those found in honeybees and other wasp species. This points to possible pathways for transmission between species.

These findings increase our understanding of the range of hosts or transmitters, as well as the geographic spread of bee viruses. They highlight the ecological role of V. crabro in the potential spread of pollinator pathogens. Further research should examine whether they are acquired through eating contaminated prey or environmental exposure, and whether these viruses can reproduce in hornet hosts. Such studies will be important for understanding how viruses spread among pollinators and predators and what this means for honeybee health and the stability of ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G. and Á.J.; Methodology, K.B., E.F., L.D. and E.K.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.G. and E.K.; Writing—Review and Editing, J.G., M.H. and E.K.; Supervision, M.M., G.H. and Á.Z. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was financed from the clinical framework of the Department of Exotic Animal, Wildlife, Fish, and Honeybee Medicine, University of Veterinary Medicine, Budapest. The preparation of the publication was carried out by the tender project RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00001 entitled “National Laboratory of Infectious Animal Diseases, Antimicrobial Resistance, Veterinary Public Health and Food Chain Safety”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The partial RdRp sequences of ABPV and DWV were deposited in GenBank with the following accession numbers: PX497026 and PX497027.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kitti Szigeti-Schönhardt for her help in performing PCR tests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABPV | Acute bee paralysis virus |

| BQCV | Black queen cell virus |

| CBPV | Chronic bee paralysis virus |

| DWV | Deformed wing virus |

| IAPV | Israeli acute paralysis virus |

| KV | Kashmir virus |

| SBV | Sacbrood virus |

References

- Vas, Z. Darazsak; Magyar Természettudományi Múzeum: Budapest, Hungary, 2019; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M.E. The life history and colonial characteristics of the hornet, Vespa crabro L. (Hym., Vespinae). Entomol. Mon. Mag. 1993, 129, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Naquet, N.; Vallat, B.; Lewbart, G.A. Honeybee Veterinary Medicine: Apis mellifera L.; 5m Publishing: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S.J.; Brettell, L.E. Deformed Wing Virus in Honeybees and Other Insects. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Gayral, P.; Zhao, H.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Bigot, D.; Wang, X.; Yang, D.; Herniou, E.A.; Deng, S.; et al. Occurrence and Molecular Phylogeny of Honey Bee Viruses in Vespids. Viruses 2019, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Flores, M.S.; Mazzei, M.; Felicioli, A.; Dieguez-Anton, A.; Seijo, M.C. Emerging Risk of Cross-Species Transmission of Honey Bee Viruses in the Presence of Invasive Vespid Species. Insects 2022, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, K.; Altamura, G.; Martano, M.; Maiolino, P. Detection of Honeybee Viruses in Vespa orientalis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 896932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, K.; Martano, M.; Ragusa, E.; Altamura, G.; Maiolino, P. Detection of honey bee viruses in larvae of Vespa orientalis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1207319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forzan, M.; Sagona, S.; Mazzei, M.; Felicioli, A. Detection of deformed wing virus in Vespa crabro. Bull. Insectol. 2017, 70, 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Forzan, M.; Felicioli, A.; Sagona, S.; Bandecchi, P.; Mazzei, M. Complete Genome Sequence of Deformed Wing Virus Isolated from Vespa crabro in Italy. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e00961-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celle, O.; Blanchard, P.; Olivier, V.; Schurr, F.; Cougoule, N.; Faucon, J.P.; Ribiere, M. Detection of Chronic bee paralysis virus (CBPV) genome and its replicative RNA form in various hosts and possible ways of spread. Virus Res. 2008, 133, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yañez, O.; Zheng, H.-Q.; Hu, F.-L.; Neumann, P.; Dietemann, V. A scientific note on Israeli acute paralysis virus infection of Eastern honeybee Apis cerana and vespine predator Vespa velutina. Apidologie 2012, 43, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanni, C. First identification of sac brood virus (SBV) in the not native species Megachile sculpturalis. Bull. Insectol. 2022, 75, 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzei, M.; Cilia, G.; Forzan, M.; Lavazza, A.; Mutinelli, F.; Felicioli, A. Detection of replicative Kashmir Bee Virus and Black Queen Cell Virus in Asian hornet Vespa velutina (Lepelieter 1836) in Italy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eroglu, G.B. Detection of honey bee viruses in Vespula germanica: Black queen cell virus and Kashmir bee virus. Biologia 2023, 78, 2643–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, E.A.F.; Harris, R.J.; Glare, T.R. Possible pathogens of social wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) and their potential as biological control agents. New Zealand J. Zool. 1999, 26, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gál, J.; Sós, E.; Ziszisz, Á.; Hoitsy, M.; Schönhardt, K.; Mándoki, M.; Halász, G. Investigation of certain viral infections of honeybees (Apis mellifera Linnaeus, 1758) in Hungarian apiaries in spring period. Magy. Állatorvosok Lapja 2024, 146, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).