Transcriptomic Analysis of the Impact of the tet(X4) Gene on the Growth Characteristics and Antibiotic Resistance Phenotypes of Escherichia coli Isolated from Musk Deer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

2.2. Construction of the ΔtetX Deletion Mutant and the ΔtetX::tetX Complemented Strain

2.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

2.4. Bioassay for Tetracycline Inactivation Mediated by the tet(X4) Gene

2.5. Tigecycline Degradation Assay

2.6. Starvation Survival Assay

2.7. RNA Extraction and Transcriptomic Sequencing

2.8. RT-qPCR Validation of Transcriptomic Sequencing Data

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

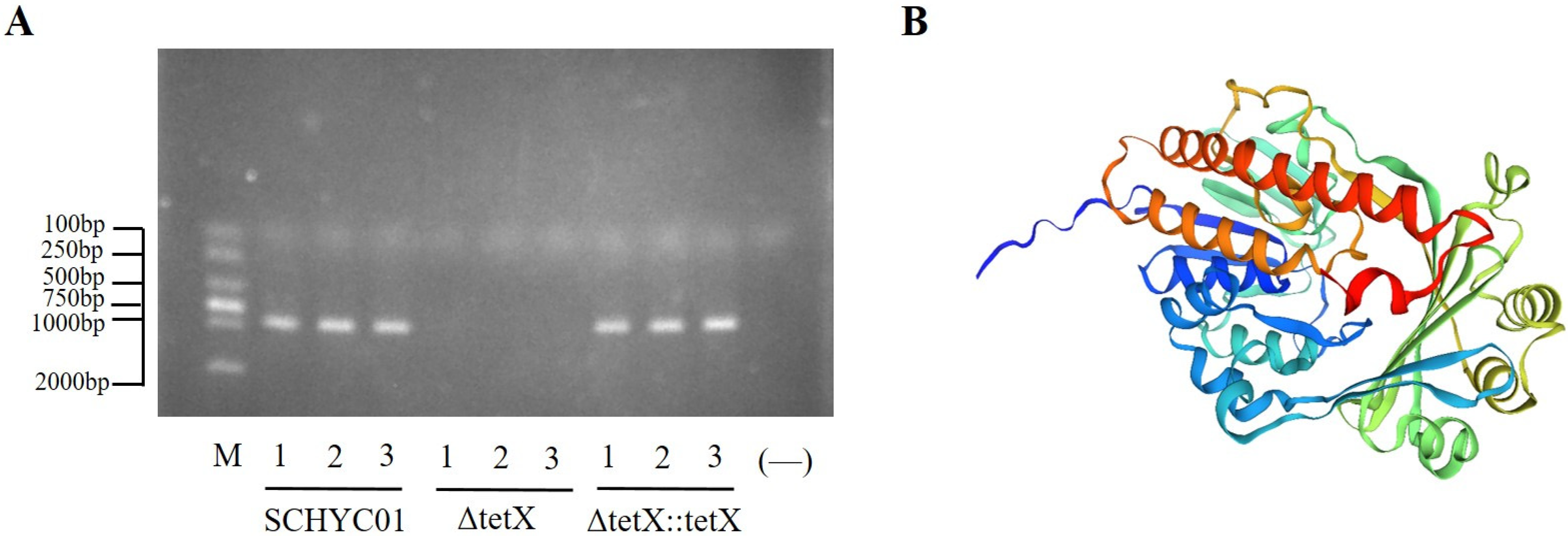

3.1. Construction and Verification of the tet(X4) Gene Deletion and Complemented Strains

3.2. Determination of Antibiotic Susceptibility in Strains SCHYC01, ΔtetX, and ΔtetX::tetX

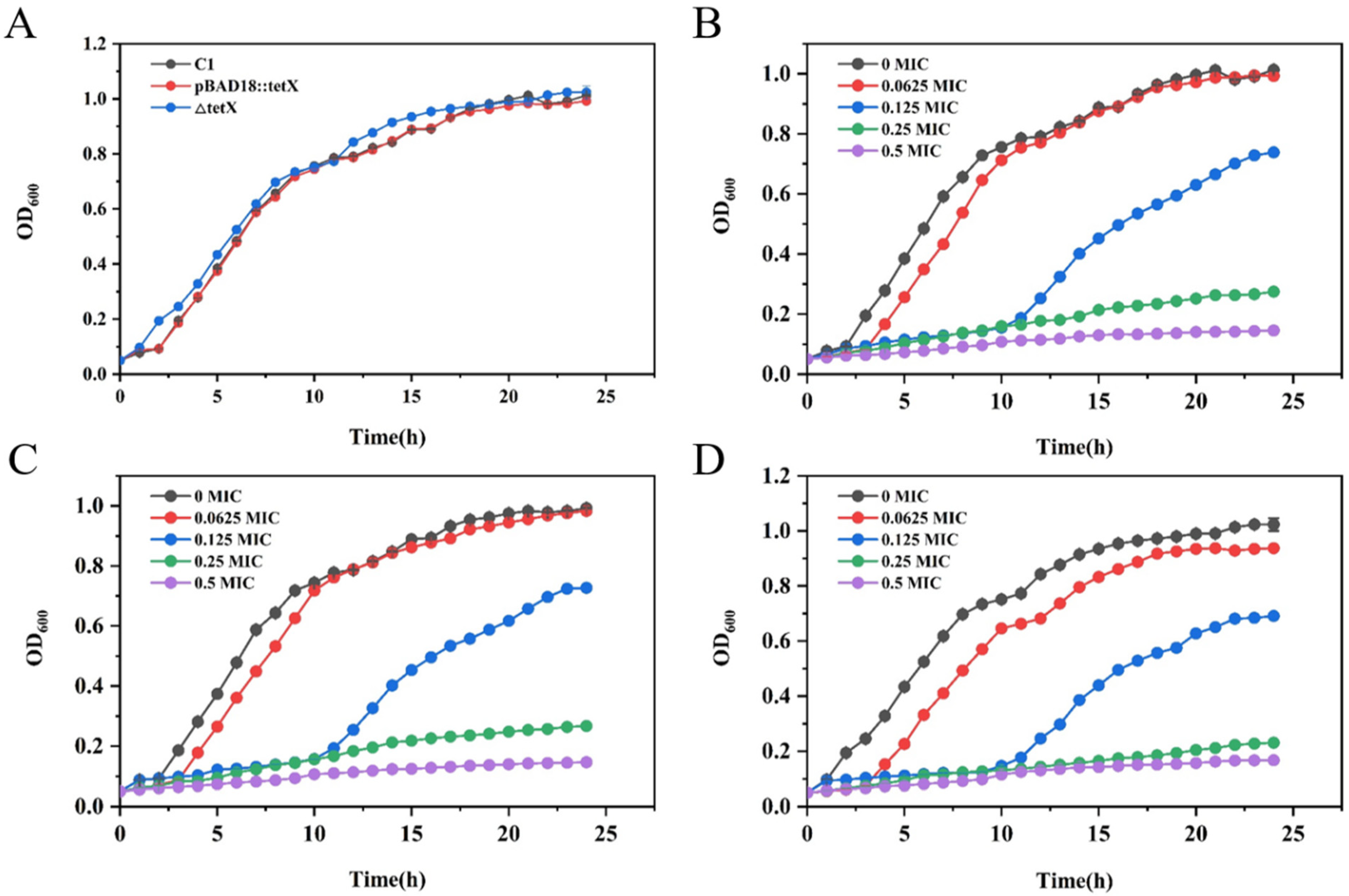

3.3. Determination of Growth Curves of Strains SCHYC01, ΔtetX, and ΔtetX::tetX

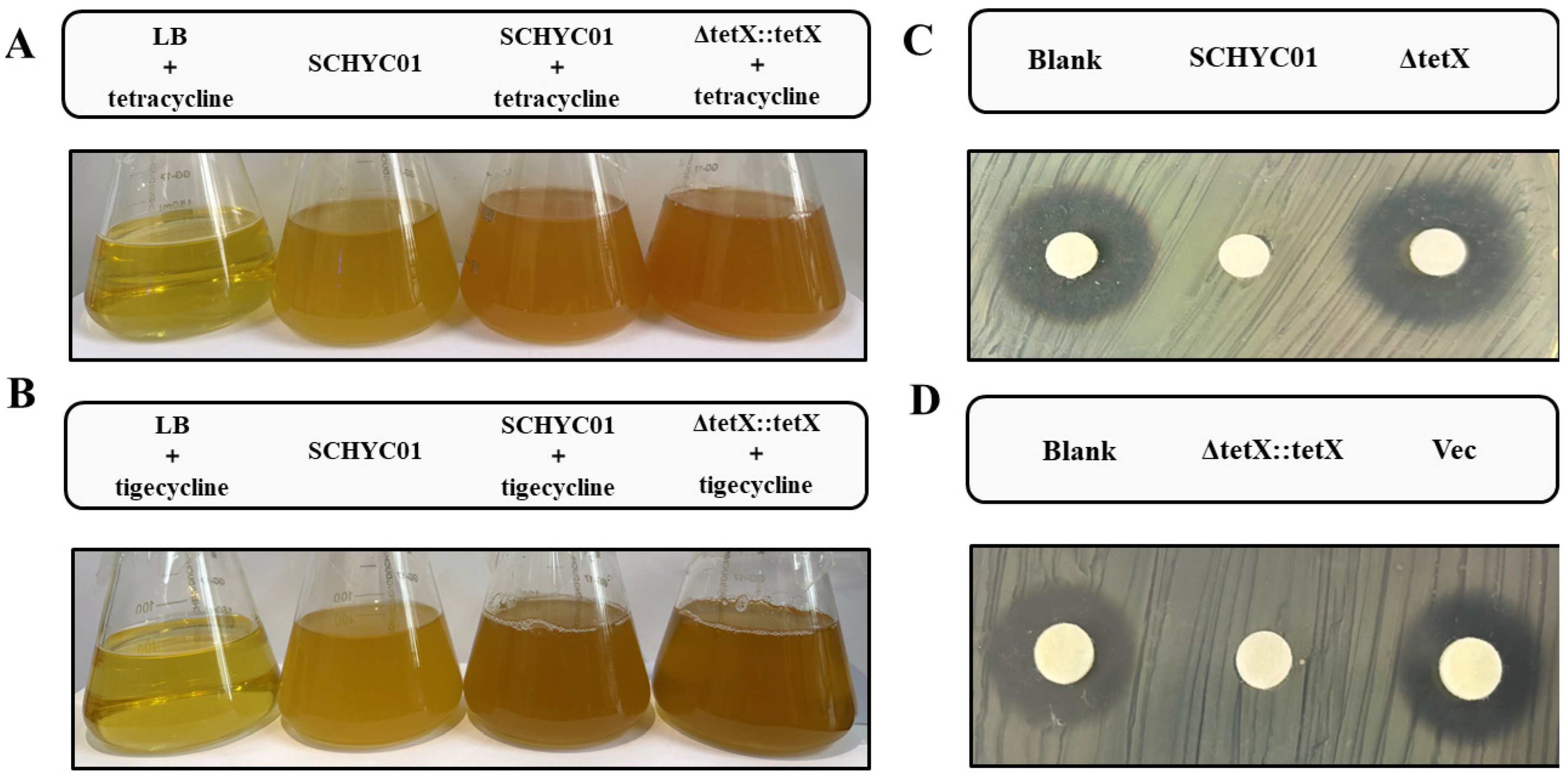

3.4. Inactivation of Tetracycline-Class Antibiotics by Tet(X4)

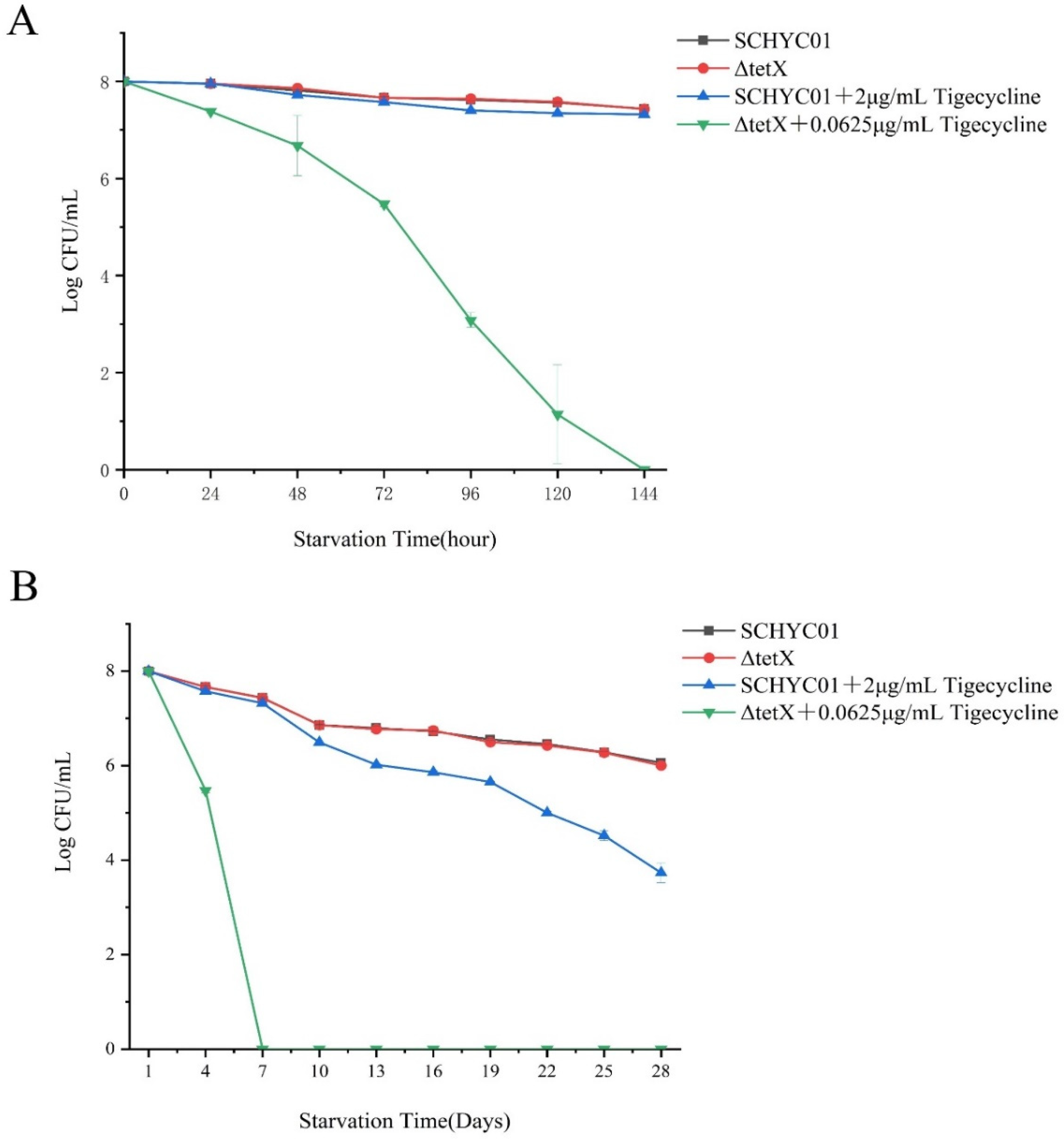

3.5. Starvation Survival Assay

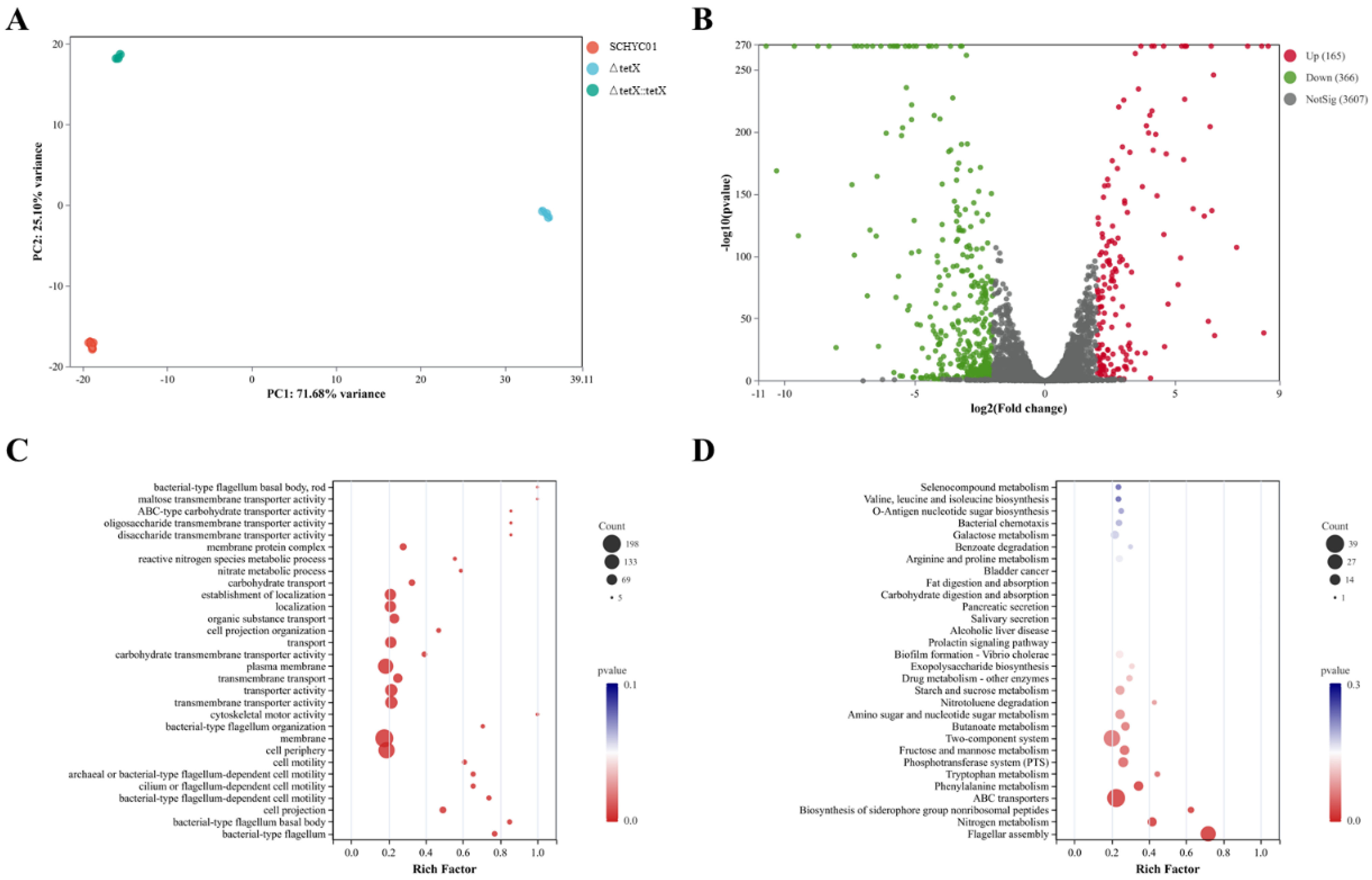

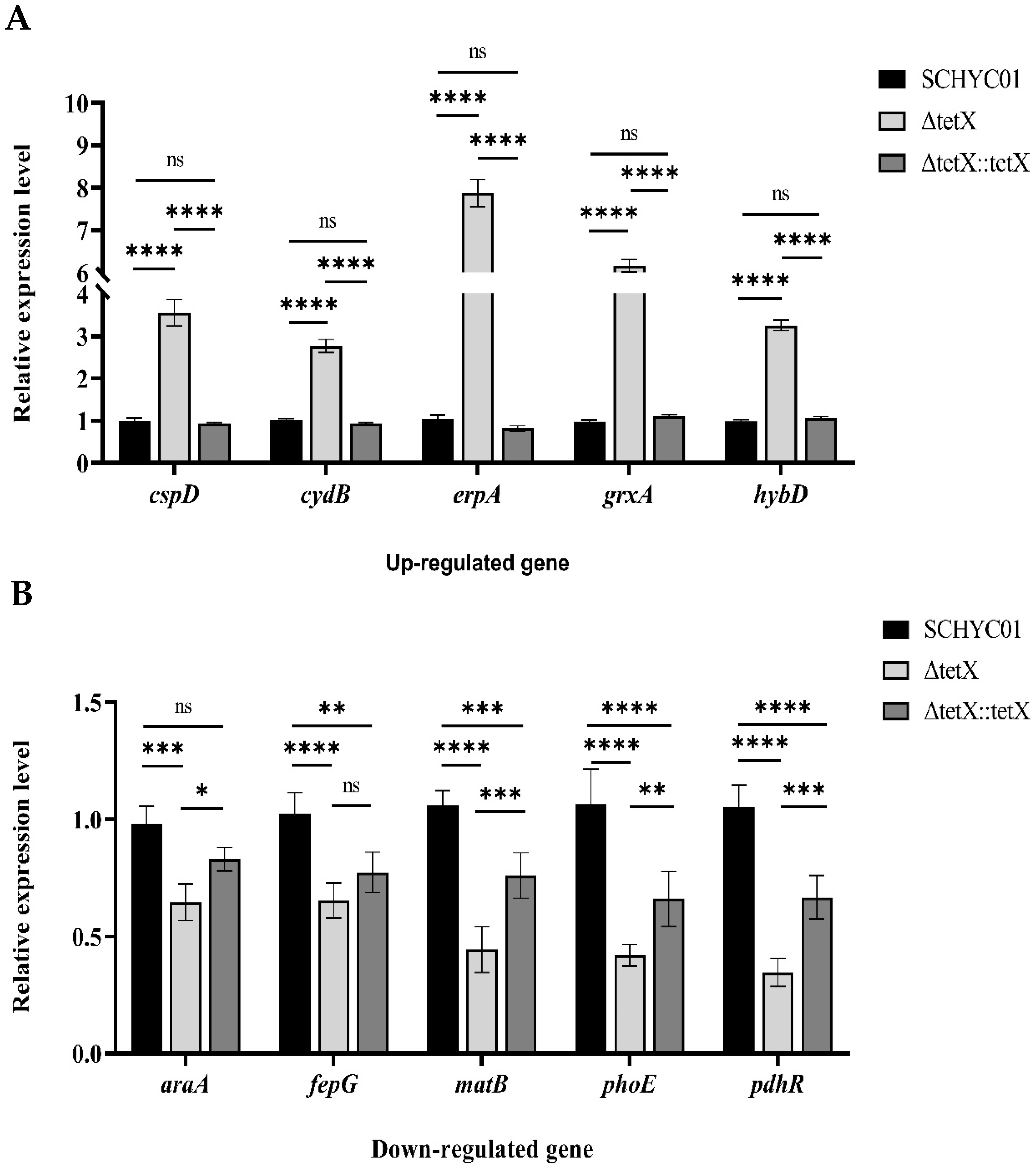

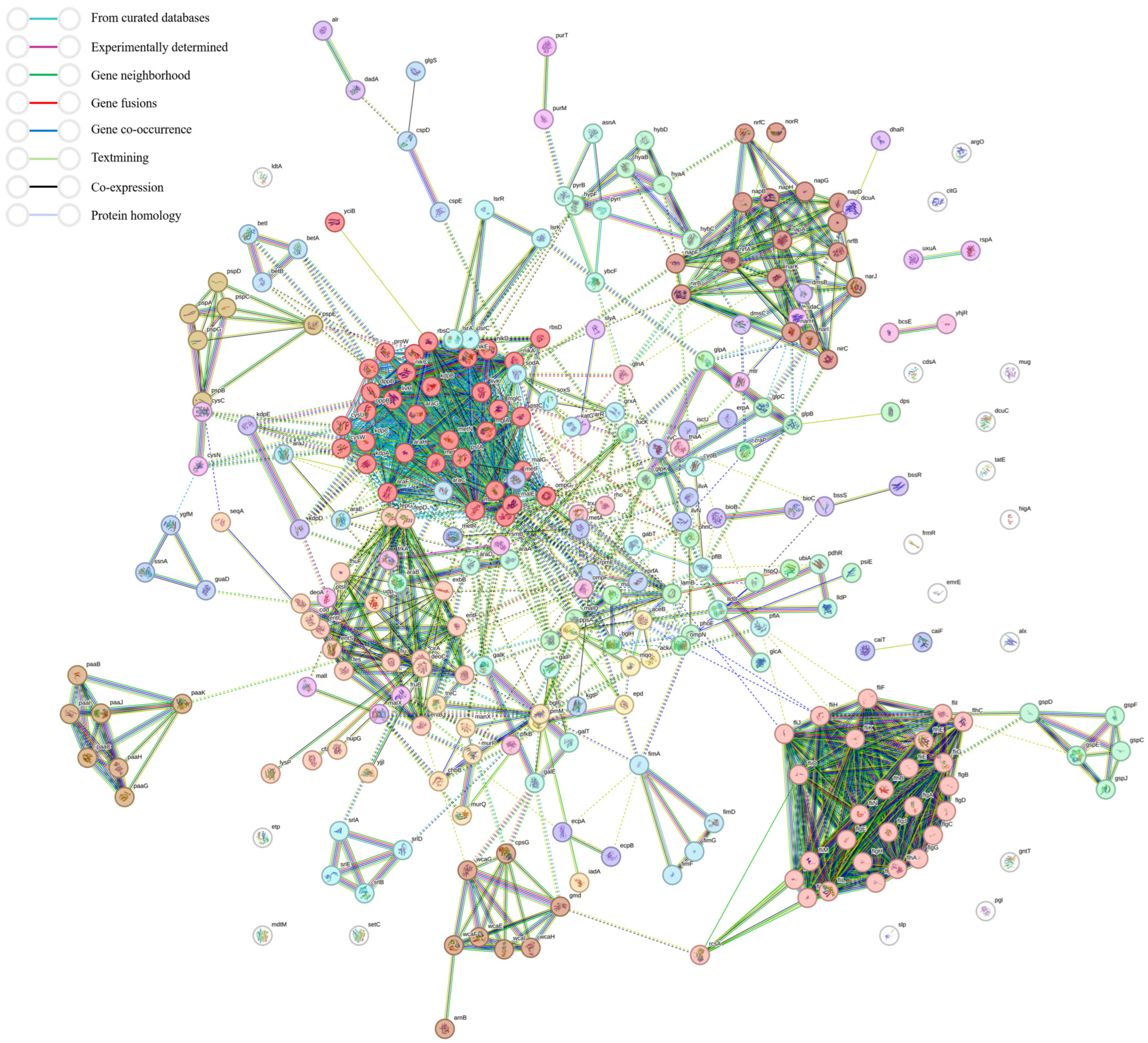

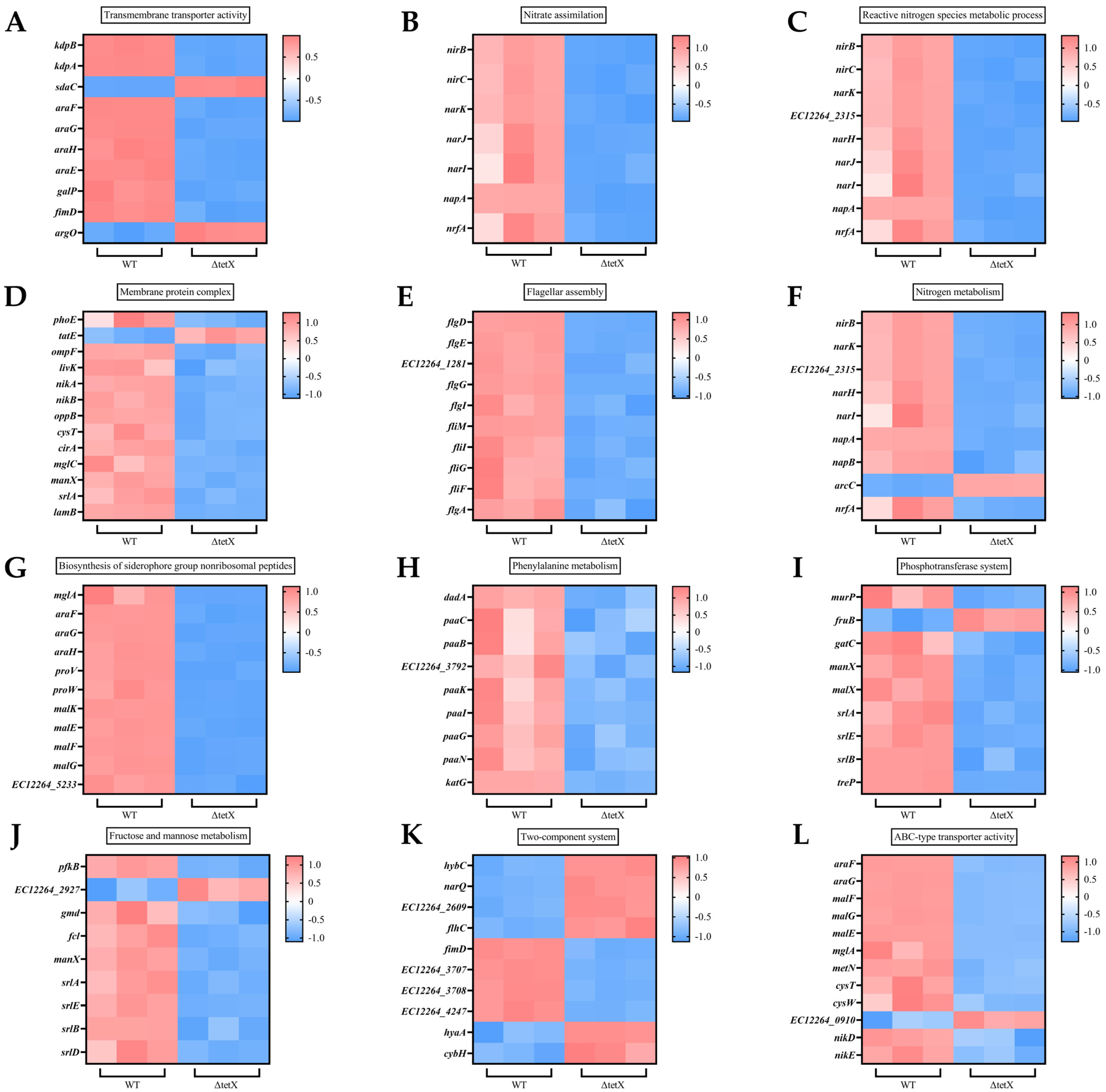

3.6. Effect of tet(X4) Gene Deletion on Global Regulatory Functions in E. coli and RT-qPCR Validation of Transcriptomic Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Hu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Peng, Z.; Sun, M.; Chen, H.; Zheng, J.; et al. Population structure and antibiotic resistance of swine extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli from China. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroithongkham, P.; Nittayasut, N.; Yindee, J.; Nimsamer, P.; Payungporn, S.; Pinpimai, K.; Ponglowhapan, S.; Chanchaithong, P. Multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli causing canine pyometra and urinary tract infections are genetically related but distinct from those causing prostatic abscesses. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, G.S.; Mannino, D.M.; Eaton, S.; Moss, M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, M.; Nie, L.; Zuo, J.; Fan, W.; Lian, L.; Hu, J.; Chen, S.; Jiang, W.; Han, X.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology and Antibiotic Resistance Associated with Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli in Shanxi Province, China, from 2021 to 2023. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Sun, Q.; Shu, L.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, R. Population genomic analysis reveals the emergence of high-risk carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli among ICU patients in China. J. Infect. 2023, 86, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Shi, C. International Spread of Tet(X4)-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates. Foods 2022, 11, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Hu, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jia, C.; Li, T.; Dai, M.; Tan, C.; Xu, Z.; Wu, B.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance and population genomics of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in pig farms in mainland China. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, K.S.; Xue, Y.P.; Gillespie, V.J.; Fishbein, S.R.S.; Tolia, N.H.; Wencewicz, T.A.; Dantas, G. The tetracycline resistome is shaped by selection for specific resistance mechanisms by each antibiotic generation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despotovic, M.; de Nies, L.; Busi, S.B.; Wilmes, P. Reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance in the context of One Health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2023, 73, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H. The tigecycline resistance mechanisms in Gram-negative bacilli. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1471469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, C.; Cui, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, Z.H.; Ma, X.Y.; Feng, Y.; Fang, L.X.; Lian, X.L.; et al. Plasmid-encoded tet(X) genes that confer high-level tigecycline resistance in Escherichia coli. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, B.; Gao, G.F. Discovery of tigecycline resistance genes tet(X3) and tet(X4) in live poultry market worker gut microbiomes and the surrounded environment. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 340–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Cui, M.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Song, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; et al. Plasmid-mediated tigecycline-resistant gene tet(X4) in Escherichia coli from food-producing animals, China, 2008–2018. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1524–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Xie, Y. A systematic review on antibiotics misuse in livestock and aquaculture and regulation implications in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, R.; Song, S.; Ai, Y.; Wang, S.; Dong, X.; Ren, Z.; Xie, H.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, L. Exploring the growing forest musk deer (Moschus berezovskii) dietary protein requirement based on gut microbiome. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1124163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yang, W.; Cheng, J.G.; Luo, Y.; Fu, W.L.; Zhou, L.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, Z.J.; Yang, Z.X.; et al. Molecular cloning, prokaryotic expression and its application potential evaluation of interferon (IFN)-ω of forest musk deer. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, M.; Xu, H.; Fu, C.; Pang, X.; Wang, M. Mechanisms of tigecycline resistance in Gram-negative bacteria: A narrative review. Eng. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, C.; Yang, S.; Fu, X.; Wang, W.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, W.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Liang, X.; et al. An efficient method for knocking out genes on the virulence plasmid of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. New Microbiol. 2023, 46, 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.S.; Qi, Y.; Xue, J.Z.; Xu, G.Y.; Xu, Y.X.; Li, X.Y.; Muhammad, I.; Kong, L.C.; Ma, H.X. Transcriptomic Changes and satP Gene Function Analysis in Pasteurella multocida with Different Levels of Resistance to Enrofloxacin. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Lucy, I.B. Conventional methods and future trends in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 30, 103582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, V.; Cunha, E.; Nunes, T.; Silva, E.; Tavares, L.; Mateus, L.; Oliveira, M. Antimicrobial Resistance of Clinical and Commensal Escherichia coli Canine Isolates: Profile Characterization and Comparison of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Results According to Different Guidelines. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, J.Q.; Chang, H.Y.; Tan, S.H.; Tang, C.Y.; Ong, R.T.; Ko, K.K.K.; Chung, S.J.; Tan, T.T.; Kwa, A.L. Comparative Activities of Novel Therapeutic Agents against Molecularly Characterized Clinical Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales Isolates. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, Z.; Chen, Q.; Tang, B.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ji, K.; Jia, X.; Feng, Y. The poultry pathogen Riemerella anatipestifer appears as a reservoir for Tet(X) tigecycline resistance. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 7465–7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cui, C.Y.; Yu, J.J.; He, Q.; Wu, X.T.; He, Y.Z.; Cui, Z.H.; Li, C.; Jia, Q.L.; Shen, X.G.; et al. Genetic diversity and characteristics of high-level tigecycline resistance Tet(X) in Acinetobacter species. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Ye, L.; Zheng, J.; Tang, Y.; Chan, E.W.; Chen, S. Starvation-induced mutagenesis in rhsC and ybfD genes extends bacterial tolerance to various stresses by boosting efflux function. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 295, 128106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.Z.; Yassour, M.; Adiconis, X.; Nusbaum, C.; Thompson, D.A.; Friedman, N.; Gnirke, A.; Regev, A. Comprehensive comparative analysis of strand-specific RNA sequencing methods. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Yu, G.; Shi, C.; Liu, L.; Guo, Q.; Han, C.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, B.; Gao, H.; et al. Majorbio Cloud: A one-stop, comprehensive bioinformatic platform for multiomics analyses. iMeta 2022, 1, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.X.; Chen, C.; Cui, C.Y.; Li, X.P.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, X.P.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.H. Emerging High-Level Tigecycline Resistance: Novel Tetracycline Destructases Spread via the Mobile Tet(X). Bioessays 2020, 42, e2000014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seputiene, V.; Povilonis, J.; Armalyte, J.; Suziedelis, K.; Pavilonis, A.; Suziedeliene, E. Tigecycline—How powerful is it in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria? Medicina 2010, 46, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livermore, D.M. Tigecycline: What is it, and where should it be used? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005, 56, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Han, R.; Jiang, B.; Ding, L.; Yang, F.; Zheng, B.; Yang, Y.; Wu, S.; Yin, D.; Zhu, D.; et al. In Vitro Activity of New β-Lactam-β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations and Comparators against Clinical Isolates of Gram-Negative Bacilli: Results from the China Antimicrobial Surveillance Network (CHINET) in 2019. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0185422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Wu, X.; Ding, H.; Ma, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yao, X.; Luo, Y. Isolation, Identification, and Antibiotic Resistance, CRISPR System Analysis of Escherichia coli from Forest Musk Deer in Western China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Ye, L.; Chan, E.W.; Zhang, R.; Chen, S. Characterization of an IncFIB/IncHI1B Plasmid Encoding Efflux Pump TMexCD1-TOprJ1 in a Clinical Tigecycline- and Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Yu, Y.; Hua, X. Resistance mechanisms of tigecycline in Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1141490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, H.; Liu, J.; Gu, Q.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Sun, L.; Jiao, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, J. Distribution and spread of tigecycline resistance gene tet(X4) in Escherichia coli from different sources. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1399732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Cai, W.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Large-Scale Analysis of Fitness Cost of tet(X4)-Positive Plasmids in Escherichia coli. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 798802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lu, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Peng, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, R. Molecular epidemiology and population genomics of tet(X4), blaNDM or mcr-1 positive Escherichia coli from migratory birds in southeast coast of China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 244, 114032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Cui, M.; Zhang, S.; Liu, D.; Fu, B.; Li, Z.; Bai, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Song, L.; et al. Genomic epidemiology of animal-derived tigecycline-resistant Escherichia coli across China reveals recent endemic plasmid-encoded tet(X4) gene. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, T.; Shao, D.; Song, H.; Zhai, W.; Sun, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, R.; et al. Structural diversity of the ISCR2-mediated rolling-cycle transferable unit carrying tet(X4). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, M.; Chan, E.W.C.; Chen, S. Membrane Transporters of the Major Facilitator Superfamily Are Essential for Long-Term Maintenance of Phenotypic Tolerance to Multiple Antibiotics in E. coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0184621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yang, M.; Khan, M.I.; Zhou, X. Sensor histidine kinase is a β-lactam receptor and induces resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1648–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, Y.; Oshima, T.; Mori, H.; Aono, R.; Yamamoto, K.; Ishihama, A.; Utsumi, R. Transcriptional regulation of drug efflux genes by EvgAS, a two-component system in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 2003, 149, 2819–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Huang, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; He, S.; Zhu, J.; Liu, H.; Shi, X. Characterization of the Role of Two-Component Systems in Antibiotic Resistance Formation in Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis. mSphere 2022, 7, e00383-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoullis, L.; Papachristodoulou, E.; Chra, P.; Panos, G. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Important Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Pathogens and Novel Antibiotic Solutions. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhalen, B.; Dastvan, R.; Thangapandian, S.; Peskova, Y.; Koteiche, H.A.; Nakamoto, R.K.; Tajkhorshid, E.; McHaourab, H.S. Energy transduction and alternating access of the mammalian ABC transporter P-glycoprotein. Nature 2017, 543, 738–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, A.W.P.; Llabrés, S.; Neuberger, A.; Blaza, J.N.; Bai, X.C.; Okada, U.; Murakami, S.; van Veen, H.W.; Zachariae, U.; Scheres, S.H.W.; et al. Structure of the MacAB-TolC ABC-type tripartite multidrug efflux pump. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirshikova, T.V.; Sierra-Bakhshi, C.G.; Kamaletdinova, L.K.; Matrosova, L.E.; Khabipova, N.N.; Evtugyn, V.G.; Khilyas, I.V.; Danilova, I.V.; Mardanova, A.M.; Sharipova, M.R.; et al. The ABC-Type Efflux Pump MacAB Is Involved in Protection of Serratia marcescens against Aminoglycoside Antibiotics, Polymyxins, and Oxidative Stress. mSphere 2021, 6, e00033-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Cao, M.; Li, C.; Huang, J.; Zheng, S.; Wang, G. Efflux proteins MacAB confer resistance to arsenite and penicillin/macrolide-type antibiotics in Agrobacterium tumefaciens 5A. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellmich, U.A.; Mönkemeyer, L.; Velamakanni, S.; van Veen, H.W.; Glaubitz, C. Effects of nucleotide binding to LmrA: A combined MAS-NMR and solution NMR study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1848, 3158–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellmich, U.A.; Lyubenova, S.; Kaltenborn, E.; Doshi, R.; van Veen, H.W.; Prisner, T.F.; Glaubitz, C. Probing the ATP hydrolysis cycle of the ABC multidrug transporter LmrA by pulsed EPR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5857–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavilla Lerma, L.; Benomar, N.; Valenzuela, A.S.; Casado Muñoz Mdel, C.; Gálvez, A.; Abriouel, H. Role of EfrAB efflux pump in biocide tolerance and antibiotic resistance of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium isolated from traditional fermented foods and the effect of EDTA as EfrAB inhibitor. Food Microbiol. 2014, 44, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.F.; Lin, Y.Y.; Yeh, H.W.; Lan, C.Y. Role of the BaeSR two-component system in the regulation of Acinetobacter baumannii adeAB genes and its correlation with tigecycline susceptibility. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Li, W.; Xue, M.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Ni, J.; Shang, F.; Xue, T. Regulatory Role of the Two-Component System BasSR in the Expression of the EmrD Multidrug Efflux in Escherichia coli. Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Xie, M.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Ye, L.; Chen, K.; Chan, E.W.; Chen, S. Conjugative transmission of virulence plasmid in Klebsiella pneumoniae mediated by a novel IncN-like plasmid. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 289, 127896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Xie, N.; Gao, Y.; Fu, J.; Tan, C.E.; Yang, Q.E.; Wang, S.; Shen, Z.; Ji, Q.; Parkhill, J.; et al. VirBR, a transcription regulator, promotes IncX3 plasmid transmission, and persistence of blaNDM-5 in zoonotic bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macé, K.; Waksman, G. Cryo-EM structure of a conjugative type IV secretion system suggests a molecular switch regulating pilus biogenesis. EMBO J. 2024, 43, 3287–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xie, N.; Ma, T.; Tan, C.E.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Ma, S.; Deng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J. VirBR counter-silences HppX3 to promote conjugation of blaNDM-IncX3 plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffert, Y.; Fraikin, N.; Makhloufi, Y.; Baltenneck, J.; Val, M.E.; Dedieu-Berne, A.; Degosserie, J.; Iorga, B.I.; Bogaerts, P.; Gueguen, E.; et al. Genetic determinants of pOXA-48 plasmid maintenance and propagation in Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X.; Jiao, M.; Qin, Q.; He, X.; Kang, L.; Hwang, P.M.; Zheng, F.; et al. Structural and mechanistic insights into the transcriptional regulation of chromosomal T6SS by large conjugative plasmid-encoded TetRs in Acinetobacter baumannii. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, B.S.; Ly, P.M.; Irwin, J.N.; Pukatzki, S.; Feldman, M.F. A multidrug resistance plasmid contains the molecular switch for type VI secretion in Acinetobacter baumannii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 9442–9447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Venanzio, G.; Moon, K.H.; Weber, B.S.; Lopez, J.; Ly, P.M.; Potter, R.F.; Dantas, G.; Feldman, M.F. Multidrug-resistant plasmids repress chromosomally encoded T6SS to enable their dissemination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1378–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category of Antimicrobial | Antibiotic | Strain SCHYC01 | Strain ΔtetX | Strain ΔtetX::tetX |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactams | piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP) | 16/4 μg/mL (I) | 16/4 μg/mL (I) | 16/4 μg/mL (I) |

| ampicillin/sulbactam (SAM) | 32/16 μg/mL (R) | 32/16 μg/mL (R) | 32/16 μg/mL (R) | |

| amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC) | 32/16 μg/mL (R) | 32/16 μg/mL (R) | 32/16 μg/mL (R) | |

| ceftazidime (CAZ) | 32 μg/mL (R) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 32 μg/mL (R) | |

| cefuroxime sodium (CXM) | 32 μg/mL (R) | 32 μg/mL (R) | 32 μg/mL (R) | |

| ceftriaxone (CRO) | 8 μg/mL (R) | 4 μg/mL (R) | 8 μg/mL (R) | |

| cephazolin (KZ) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 16 μg/mL (R) | |

| cefoxitin (FOX) | 32 μg/mL (R) | 32 μg/mL (R) | 32 μg/mL (R) | |

| aztreonam (ATM) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 16 μg/mL (R) | |

| imipenem (IPM) | 2 μg/mL (I) | 1 μg/mL (S) | 2 μg/mL (I) | |

| meropenem (MEM) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 8 μg/mL (R) | 16 μg/mL (R) | |

| aminoglycosides | gentamicin (CN) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 16 μg/mL (R) |

| tobramycin (TOB) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 8 μg/mL (I) | 16 μg/mL (R) | |

| amikacin (AK) | 64 μg/mL (R) | 32 μg/mL (I) | 64 μg/mL (R) | |

| sulfonamides | trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) | 1024 μg/mL (R) | 1024 μg/mL (R) | 1024 μg/mL (R) |

| polypeptides | polymyxin b (PB) | 0.5 μg/mL (S) | 0.25 μg/mL (S) | 0.5 μg/mL (S) |

| furans | nitrofurantoin (NFT) | 256 μg/mL (R) | 128 μg/mL (R) | 256 μg/mL (R) |

| quinolones | levofloxacin (LEV) | 0.5 μg/mL (S) | 0.5 μg/mL (S) | 0.5 μg/mL (S) |

| ciprofloxacin (CIP) | 1 μg/mL (R) | 1 μg/mL (R) | 1 μg/mL (R) | |

| amide alcohols | florfenicol (FFC) | 32 μg/mL (R) | 32 μg/mL (R) | 32 μg/mL (R) |

| chloramphenicol (CHL) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 8 μg/mL (I) | 8 μg/mL (I) | |

| tetracyclines | tetracycline (TE) | 64 μg/mL (R) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 32 μg/mL (R) |

| doxycycline (DO) | 32 μg/mL (R) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 32 μg/mL (R) | |

| Tigecycline (TGC) | 16 μg/mL (R) | 0.25 μg/mL (S) | 16 μg/mL (R) |

| Days | Antibiotic (μg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetracycline | Doxycycline | Tigecycline | |

| 0 | 64 | 32 | 16 |

| 7 | 64 | 32 | 16 |

| 14 | 64 | 32 | 16 |

| 21 | 32 | 32 | 16 |

| 28 | 32 | 32 | 16 |

| Days | Antibiotic (μg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetracycline | Doxycycline | Tigecycline | |

| 0 | 64 | 32 | 16 |

| 7 | 64 | 32 | 16 |

| 14 | 32 | 32 | 16 |

| 21 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| 28 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, K.; Wu, X.; Ma, B.; Cheng, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yao, X.; Luo, Y. Transcriptomic Analysis of the Impact of the tet(X4) Gene on the Growth Characteristics and Antibiotic Resistance Phenotypes of Escherichia coli Isolated from Musk Deer. Animals 2025, 15, 3564. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243564

Yang K, Wu X, Ma B, Cheng J, Li Z, Wang Y, Yang Z, Yao X, Luo Y. Transcriptomic Analysis of the Impact of the tet(X4) Gene on the Growth Characteristics and Antibiotic Resistance Phenotypes of Escherichia coli Isolated from Musk Deer. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3564. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243564

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Kaiwei, Xi Wu, Bingcun Ma, Jianguo Cheng, Zengting Li, Yin Wang, Zexiao Yang, Xueping Yao, and Yan Luo. 2025. "Transcriptomic Analysis of the Impact of the tet(X4) Gene on the Growth Characteristics and Antibiotic Resistance Phenotypes of Escherichia coli Isolated from Musk Deer" Animals 15, no. 24: 3564. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243564

APA StyleYang, K., Wu, X., Ma, B., Cheng, J., Li, Z., Wang, Y., Yang, Z., Yao, X., & Luo, Y. (2025). Transcriptomic Analysis of the Impact of the tet(X4) Gene on the Growth Characteristics and Antibiotic Resistance Phenotypes of Escherichia coli Isolated from Musk Deer. Animals, 15(24), 3564. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243564