Simple Summary

Methane emitted by cattle is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions from livestock systems. However, accurately quantifying these emissions under grazing conditions remains a challenge, especially in tropical regions where specialized infrastructure is limited. The present study evaluated an innovative spirometry mask prototype designed to measure enteric methane emissions directly from grazing cattle in field conditions. This mask integrates a low-cost MQ4 methane sensor and data recording system that allows continuous measurements during normal animal activity. Through experimental trials, we demonstrated that the spirometry mask can reliably estimate methane emissions while maintaining animal comfort and normal behavior. This development provides a practical and accessible alternative for researchers and producers to monitor emissions in extensive production systems, contributing to more sustainable livestock management and the development of mitigation strategies adapted to tropical environments.

Abstract

Dual-purpose livestock farming in the Colombian low tropics faces nutritional limitations that affect productivity and increase enteric methane (CH4) emissions. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate supplementation strategies that optimize the use of nutrients and reduce environmental impacts. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of three types of dietary supplementation—mineralized salt (MS), proteinized salt (PS), and concentrated feed (CO)—on milk production, efficiency in the deposition of dairy nutrients, and enteric CH4 emissions in dual-purpose grazing cows in the Colombian Amazon. Twenty-four F1 Holstein × Gyr cows were used in a completely randomized block design. Nutrient intake, digestibility, composition, and efficiency in the milk deposition of Ca, P, K, and N were measured; additionally, CH4 emissions were assessed using a portable electronic spirometry mask. The results indicated that the treatments did not modify the total intake of dry matter or the production and composition of milk. CO and MS supplementation improved the efficiency of Ca and P (p < 0.03) deposition in milk, while no differences were observed for N and K. CH4 emissions (196 ± 17.9 g/cow/day) were not affected by the supplements and were within the ranges reported for dual-purpose tropical systems. However, with the supplementation with CO was a lower losses of gross energy intake as CH4 (Ym) (p < 0.05). In conclusion, supplementation with the evaluated products did not impact milk production or CH4 emissions, although with CO was lower energy losses as CH4 and, CO and MS improved the use of Ca and P, which highlights the importance of adjusting supplementation to optimize nutritional efficiency without increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

1. Introduction

Cattle farming is an important economic activity in tropical countries because of its contribution to food security through meat and milk production. In Colombia, the per capita milk intake is 154 L/person/year, while beef intake is 18.2 kg/person/year [1]. These amounts represent a substantial proportion of the milk and meat intake recommended by the WHO [2]. Colombia currently has a cattle inventory of approximately 29 million head, distributed across a variety of production systems that include breeding, fattening, dual-purpose (DPS) farming, and specialized dairy farming [3]. These systems are present throughout the national territory and take advantage of the diverse geographical and climatic conditions of each region. DPS, in particular, has expanded notably in recent years and now provides the majority of the country’s annual milk production [4], making it highly relevant within the national herd due to its contribution to job and income generation [5]. These production systems are characterized by the use of crossbreeding between Bos indicus and Bos taurus breeds to improve adaptation to tropical conditions, enabling producers to obtain economic benefits from the sale of milk and weaned calves in local, national, and international markets [6,7]. They are also based on grazing tropical grasses with low levels of feed supplementation, and cows are partially milked to allow calves access to residual milk [8].

Grazing on tropical grasses forms the basis of feeding under the DPS, but it faces challenges due to seasonality in the availability and quality of the pastures which, in turn, generates low milk production on a seasonal basis [9].

Tropical grasses use the C4 phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase metabolic path-way for carbon fixation [10,11], which leads to a greater accumulation of structural carbo-hydrates and lignin compared to those that use the C3 pathway [12,13]. It can affect the palatability and digestibility of these forages in ruminants [13,14] and limits the ability of animals to extract essential nutrients efficiently, and frequently cause protein, energy, and mineral deficiencies [15]. As a consequence, the intake of forage by animals is affected and the production of enteric methane (CH4) per unit of dry matter intake is increased, thus reducing productive efficiency [12,16,17]. Grazing on grasses that use the C4 metabolic pathway, compared to grazing on those that use the C3 pathway, is associated with a lower efficiency in milk and meat production in ruminants, partially due to an increase in CH4 emissions [17,18,19].

The generation of gases in the rumen is closely related to the microbial activity that occurs during fermentation. CH4 produced in this process represents about 6.5% of the gross energy consumed [20], although values of 11.4% [21] and up to 13.7% [22] have been reported. This figure can vary significantly depending on the animal’s diet, with lower levels found in diets rich in grains and higher levels found when low-quality forage is consumed [23,24].

Besides the importance of CH4 in the energy efficiency of animals, its role as a greenhouse gas within the scientific landscape over the last 50 years should be considered. The global warming potential of this gas was calculated to be 28 times that of carbon dioxide [25]. Consequently, there has been a sustained increase in research on CH4 production in the gastrointestinal tracts of ruminants, as well as in the development of strategies to reduce these emissions [26].

Dietary supplementation stands out among the strategies suggested to reduce enteric CH4 emissions in ruminants [27]. However, this response depends on the types and amounts of supplements used [26,28,29]. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate different types of dietary supplements in the field and their efficiency in the milk deposition of nutrients, as well as their ability to improve milk production and reduce CH4 emissions. The most commonly used food supplements in the Colombian tropics include mineralized salts, multi-nutritional blocks, and concentrated foods [30,31]. However, there are no reports on the effects of these supplements on CH4 emissions in lactating cows under dual-purpose systems in the Colombian low tropics. This paucity of research may be due to the lack of methods for measuring CH4 emissions from grazing livestock that are easy to implement, economical, and provide detailed information on this process. However, Correa and Jaimes [32] recently proposed a prototype portable electronic spirometry mask that allows one to measure the emissions of CH4 eliminated by exhalations. Therefore, the objective of this experiment was to quantify the effect of three dietary supplements on the milk production, milk deposition of nutrients, and enteric CH4 emissions in lactating cows grazing in a dual-purpose system located in the Colombian low tropics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

The Ethics Committee in Animal Research of Universidad Nacional de Colombia at Medellín (Antioquia) approved this study as part of the research projects under HERMES 57438, “Interfaculty alliance for the reduction in greenhouse gases in cattle farming” (CICUA-18-23).

2.2. Location

This study was carried out from 19 April to 6 May 2024, in a commercial property under a dual-purpose production system in the municipality of San Vicente del Caguán (2°06′55″ N, 74°46′12″ W), located in the Colombian Amazon region, department of Caquetá. This area is located at an altitude of approximately 280 masl and classified as a humid to very humid tropical forest [33]. The region has an average annual temperature of 25.2 °C, with a relative humidity that exceeds 70% and an average annual rainfall of 2518 mm. This area is characterized by abundant rainfall and good quality soil. Moreover, dominant pastures in the area are composed of a variety of pastures, with Mombasa (Panicum maximum cv. Mombasa) being the most abundant, followed by the Humidicola (Brachiaria humidicola) and Star grass (Cynodon nlemfuensis) pastures.

2.3. Animals and Experimental Design

Twenty-four F1 Holstein × Gyr multiparous lactating cows (Bos taurus × Bos indicus) were selected. These cows had an average live weight of 485.95 ± 55.6 kg during the second third of lactation, with an approximate milk production of 10.48 ± 3.22 L of milk per day. The cows had an average age of 81 ± 20.02 months with 192.2 ± 92.3 days in lactation and an average body condition of 3.12 ± 0.45, according to a rating scale from 1 to 5, where 5 indicates obesity and 1, emaciation [34]. The cows continued to graze primarily on Mombasa grass and star grass under a rotational system, with approximately 32 days of rest and two to three days of grazing with strips of ap-proximately 2200 m2/day being offered each morning after milking. The size of grazing strips offered was limited with an electrical fence.

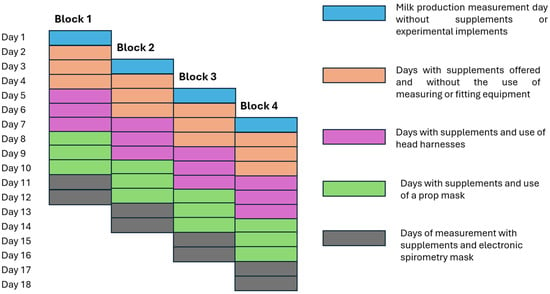

The experiment was structured as a randomized complete block design (Figure 1) with four consecutive 12-day experimental periods (blocks), in which cows were as-signed to one of three treatments (food supplements). Food supplements were prepared at the San Pablo Agricultural Station of Universidad Nacional de Colombia at Medellín, located in Rionegro, Antioquia. These supplements were formulated based on the average chemical composition of predominant pastures in the experimental field. Likewise, the assigned doses of each supplement were determined considering the estimated nutritional needs of cows [34] and the analyses results of the pastures. Experimental treatments consisted of mineralized salt (MS) offered at a rate of 100 g/cow/day; proteinized salt (PS) offered at a rate of 400 g/cow/day; and concentrated feed (CO) offered at a rate of 1 kg per 3 L of milk/cow/day. Each supplement was given in two equal servings/day during each of the two milkings (approximately 6:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m.). Table 1 presents the composition of raw materials and chemical analysis of these supplements.

Figure 1.

Schematic showing experimental periods, duration of each experimental period, and total duration of the experiment. Source: authors.

Table 1.

Ingredients and chemical composition of experimental pastures and food supplements.

2.4. Sample Size

The sample size of 24 cows (8 cows per treatment) was determined based on herd availability and the operational capacity of the methane-measurement system, with four temporal blocks and two cows per treatment per block. Because enteric methane was the primary response variable of interest, a post hoc power evaluation was calculated using the observed variability of daily methane production. The mean CH4 emission was 195.67 g/day, with a within-treatment standard deviation of 17.03 g/day. Assuming α = 0.05, two-sided tests, three treatments, and 8 cows per treatment, the minimal detectable difference with 80% power was ap-proximately 1.4 × SD (23.8 g CH4/day). The study had sufficient statistical power to detect (12% of the mean emission level) moderate changes in daily methane pro-duction under grazing conditions.

2.5. Data Collection

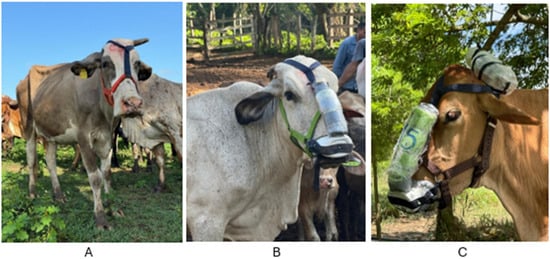

The 24 cows randomly entered the experiment in four blocks of 12-day experimental periods with a two-day interval between blocks and six cows/block in a randomized complete block design. Therefore, the block is one of four groups of six cows that entered the experiment every two days. In each block, two cows were randomly assigned to one of the three experimental treatments (CO, PS and MS). On the first day of each experimental period, the food supplement received by the animals was withdrawn, and the milk production of each cow was determined. Based on the results, cows were assigned in a balanced manner to each of the three treatments in such a way that in each period, there were two cows/treatment. Subsequently, the cows began an adaptation period to the treatments, lasting until day 10. Between day 4 and 7, each cow was fitted with a polypropylene halter as part of the adaptation period to the measurement equipment (see Figure 2A). Between day 8 and 10, each cow was fitted with a halter to which a prop mask that simulated the measurement equipment was assembled. However, this mask featured only a plastic box installed on one side, a mask that covered the nostrils, and a hose covered by foam to avoid damage to the equipment due to possible blows (see Figure 2B). On days 11 and 12, between 7:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m., the cows were fitted with a halter including a portable electronic spirometry mask (ESM) that completely covered the animals’ nostrils (see Figure 2C). This mask featured a CH4 sensor (MQ4, Hanwei Electronics, Zhengzhou, China), an airflow sensor (DN-40, Louchen ZM Shenzhen,, China), and an exhalation counter similar to that described by CorreaCorrea and Jaimes [32] and were calibrated as described by Jaimes et al. [36]. These three components were connected to an ARDUINO board (model ONE R3 MEGA328P, Si Tai&SH Hengtai Store, Hong Kong, China) programmed using ARDUINO IDE 2.0.4 to store the information on a MicroSD card every 500 ms.

Figure 2.

Adaptive and measuring harnesses (spirometry mask): (A) halter, (B) halter with prop mask, and (C) halter with electronic spirometry mask. Source: authors.

Likewise, pasture sampling was conducted during the last three days of each experi-mental period (day 10 to day 18 in Figure 1), before the cows entered the pasture strip. A proportional amount of each type of grass present in the strip was taken at a height of approximately 10 cm. These samples were mixed to obtain a final sample, which was then stored under refrigeration for chemical analysis. Elsewhere, during the last three days of each experimental period samples were taken from the experimental supplements, and from feces during each milking. These samples were mixed to obtain a single sample/animal and kept under refrigeration until they were brought to the laboratory for analysis.

During each of the two milking, cows were handled in individual cubicles with a feeder, and a supplement was fed in the amount corresponding to each treatment. When necessary, the hind legs of the cows were immobilized to avoid damage to the measuring equipment or accidental injury to the animals or operators. Milking was stimulated by the presence of calves and lasted between 7 and 10 min; during this time, supplements were offered.

2.6. Milk Production and Milk Sampling

The milk production of each cow was measured from both milking during the last three days of each period and the mean of this measurements was used to the statistical analysis. Approximately 50 mL of milk samples was taken from each animal every milking. Then, these samples were mixed to obtain a single representative sample per animal. This mixed sample was frozen for subsequent analysis in the laboratory. On days of milk production measurement, calves were present alongside the cows only to stimulate milking. Subsequently, the calves were separated to accurately record the amount of milk produced under each supplement.

2.7. Estimated Dry Matter Intake (DMC)

To estimate the dry matter intake (DMI) of forage, indigestible dry matter (iDM) was used as an internal marker and chromium oxide (Cr2O3) as an external marker [37]. The iDM of the forage, supplements, and feces of each experimental cow was determined using an in vitro test for 144 h with feces taken directly from the recta of three Holstein cows adapted to a diet based on Kikuyu grass (Pennisetum clandestinum) and concentrated feed [38] as an inoculum. To estimate the production of feces, chromium oxide (Cr2O3) was used as an external marker [39]. This marker was prepared in a 1:1 ratio with the concentrated feed and then pelletized to ensure intake and minimize losses. Each animal was given 15 g of these pellets during each milking for the entire experimental period. In the feces samples collected twice per day on the last three days of each experimental period, the concentration of Cr, as well as in the pelletized mixture, was determined via atomic absorption spectrometry. A marker recovery rate of 80% was assumed according to the results obtained by Rueda and Correa [40] in a dual-purpose farm in the department of Cesar. Feces production (F) was estimated following the formula proposed by Lippke [41]:

F, g = (g of Cr in food) × (recovery rate of Cr in feces)

% Fecal Cr

% Fecal Cr

The dry matter intake from pasture (PDMI) was estimated with the formula proposed by Geerken et al. [42] using information on indigestible dry matter in feces (iDMf), food supplements (iDMs), and pastures (iDMp), as well as information on F and dry matter intake from supplements (DMIs):

PDMI(kg/cow/d) = ((iDMf × F) − (iDMs × DMIs))/iDMf

Total DMI (TDMI) was estimated for each cow as the sum of PDMI and supplement dry matter intake (SDMI), which was determined daily as the difference between the quantity offered and the quantity rejected.

2.8. Laboratory Analysis

The contents of fat, crude protein, total solids, and lactose in milk samples were determined via infrared spectroscopy using the standard method ISO 9622, IDF 141:2013 [43]. Calcium (Ca) and potassium (K) were determined with atomic absorption spectrometry, while phosphorus (P) was measured using UV–VIS spectrophotometry. Milk production was adjusted considering the fat content, standardizing it to 4.0% fat (FCM) [44]. In feces, the content of Ca, K, and Cr was determined with atomic absorption spectrometry and P with UV–VIS spectrophotometry. Nitrogen (N) was quantified using the Kjeldahl volumetric method, and the neutral detergent fiber (NDF) was measured with the gravimetric method [45]. The presence of C, P, and K was quantified in the mineral salt, while the quantity of ash (Ash), Ca, P, N, and K was determined in proteinized salt. Finally, in the mixture of grasses from pasture and the concentrated supplement, gross energy was determined using an adiabatic bomb calorimeter (IKA® C5000, Cole Palmer, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) and NDFs were evaluated with the methods described by Van Soest and Robertson [46], as was ethereal extract, N, Ash, Ca, P, and K [45].

2.9. Apparent Digestibility

The apparent digestibility of NDF, N, P, Ca, and K was determined from the amount of each fraction consumed and the amount determined in feces. The efficiency of nutrients in milk deposition was calculated for N, P, K, and Ca as the percentage of each nutrient consumed that was secreted in the milk produced (g/cow/day).

2.10. Calculation of CH4 Emissions

The amount of CH4 (CH4) emitted by each animal through the exhaled air was determined by the following formula [32]:

where Ve is the volume of air exhaled (L/min), and CH4c is the concentration of CH4 (ppm).

CH4, L/min = Ve × CH4c/1,000,000

To express enteric CH4 emissions in grams, a conversion factor of 1 L of CH4 = 0.716 g was applied [47]. Based on this information, the yield (L of CH4/kg of DMI), intensity of CH4 emissions (L of CH4/L of milk), and fraction of consumed EB transformed into CH4 (Ym(%)) were calculated. The intensity of CH4 emissions was also calculated in proportion to the level of milk production corrected for fat (MF) and protein (MP) (FPMP) [48]:

FPCM (kg) = raw milk (kg) × (0.337 + 0.116 × MF (%) + 0.06 × MP (%))

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Response variables were analyzed using the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS v 8.0 (SAS Inc. 1999, Release 8.0 SAS Inst., Inc., Cary, NC, USA) by applying the following mixed model:

where Yijk is the dependent variable, µ is the mean of all observations, Bi is the fixed effect of block i, Ck(B)i is the random effect of cow k within block i, Sk is the fixed effect of supplement l (PS, MS, and CO), and εijk is the random residual error. Mean analysis was carried out with LSMEANS test using the SAS statistical package. Differences were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Yijk = µ + Bi + Ck(B)j + Sk + εijk

3. Results

One dairy cow in the MS treatment was removed from the experiment because she stopped producing milk before the trial was completed. The live weight of the animals was not affected by the treatments. The results for dry matter intake, nutrient intake, and apparent digestibility are reported in Table 2. Here, PDMI and TDMI were not affected by the experimental treatments (p > 0.05) but, GEI was higher in CO (p < 0.05). Since PDMI did not differ between treatments and remained the main source of NDF and K, its intake also did not differ between treatments. In turn, Ca intake was higher with CO and PS (p > 0.001), while P intake was higher with PS (p < 0.002). Finally, N intake was higher with CO (p < 0.01). The above results indicate that due to differences in the nutritional composition and supplements evaluated, as well as the amounts supplied, the supplements exerted different effects on the intake of chemical fractions and nutrients evaluated.

Table 2.

Intake of dry matter, calcium, potassium, phosphorus, and nitrogen in dual-purpose cows from San Vicente del Caguán (Caquetá) supplemented with mineralized salt (MS), proteinized salt (PS), and concentrated feed (CO).

Table 3 presents the results for the production, nutritional composition, and efficiency in the deposition of nutrients in the experimental cows’ milk production. Ultimately, there was no effect of the treatments on milk production and nutritional composition. However, the deposition efficiency of Ca and P in milk was significantly higher under the MS and CO treatments (p < 0.04), with no effect of the treatments on the deposition efficiency of N and K in milk.

Table 3.

Production, nutritional composition, and nutritional efficiency in dual-purpose cows’ milk production from San Vicente del Caguán (Caquetá), supplemented with mineralized salt (MS), proteinized salt (PS), and concentrated feed (CO).

To further analyze and discuss our results, a Pearson correlation analysis was carried out between milk production and efficiency in the deposition of nutrients (Table 4). As can be seen, correlations between milk production and efficiency in the deposition of Ca, P, K, and N in this experiment were positive, suggesting that an increase in milk yield significantly improved nutrient efficiency (p < 0.01)

Table 4.

Correlations between the efficiency of Ca, P, K, and N deposition in milk with milk production and the intake of each nutrient.

Data on the CH4 emissions are summarized in Table 5, which indicate that treatments did not affect any of the expressions in which emissions were quantified in this experiment, except to percentage of GEI losses as CH4 (Ym) that was lower in CO (p < 0.05). However, their values agree with those reported in the literature.

Table 5.

Concentration of exhaled CH4, volume of exhaled air, and enteric CH4 emissions in dual-purpose cows supplemented with the three evaluated treatments.

4. Discussion

The chemical composition of the pastures used in this experiment is within the values reported for tropical grasses, where high levels of NDF and low CP are notable [49,50]. Likewise, the GE content of the pastures is within the values reported for tropical grasses, with values ranging between 3.8 [50] and 4.13 Mcal/kg of DM [51]. Meanwhile, the GE content of the concentrated supplement found in this work is similar to that reported by Robles [52] in an experiment carried out in Mexico with dual-purpose grazing cows.

The response of grazing animals to dietary supplementation depends on the amount and availability of nutrients in the supplement, as well as their ability to correct the limitations of the pasture, whose effects can be reflected in the digestibility, intake, and metabolism of nutrients [53]. Carulla et al. [54] also noted that the amount of food an animal consumes is a determining factor in its productive performance. The authors stated that approximately 70% of differences in the productivity of grazing animals are attributable to variations in their food intake, with the availability and quality of forage playing a fundamental role. In this experiment, the evaluated food supplements did not affect the PDMI or the TDMI, although the ADMD was higher with the CO treatment (Table 2). This treatment (CO) had a high starch content (approximately 40%) and true protein (approximately 16.9%) but its intake was relatively low (approximately 0.9 kg DMI/Cow/d) and, by this, it could have an improve the microbial growth and, then, digestible fraction [55,56]. Thus, Palma et al. [55] and Lazzarini et al. [56] reported an increase in digestibility of organic matter when animals are supplemented with starch and protein supplement but no observed an effect on dry matter intake. Although higher ADMD is generally expected to increase PDMI [57] and exert a substitution effect [58], this relationship is highly variable, which may explain the lack of TDMI response observed here. Previous studies report that even marked changes in ADMD do not necessarily translate into changes in TDMI [59,60]. Bargo et al. [58] also highlight the wide variability in dietary responses to concentrate supplements in fibrous diets, which depend on supplement characteristics, forage quality, and animal factors. Similar to our findings, several authors report no effect of nitrogenous salt or concentrate supplementation on TDMI in dual-purpose cows grazing tropical forages [61]. In some cases, ADMD also remained unaffected [61]. Evidence from high-producing cows further supports that salt supplementation does not consistently increase TDMI [62]. Overall, the TDMI values obtained in this study fall within the ranges previously reported for comparable production systems [40,63,64]. GEI (Mcal/cow/d) was higher in CO treatment (Table 2) due to higher gross energy content of this supplement (Table 1) and due to this intake was higher (approximately 0.9 kg/cow/d) than PS (approximately 0.4 kg/cow/d) and MS (approximately 0.1 kg/cow/d).

The digestibility of NDF (NDFD) was not affected by treatments (Table 2) despite differences in the nutritional composition of supplements and amounts consumed. Although supplementation with starchy foods such as that used in this experiment could reduce the NDFD, this reduction occurs only when supplementation levels are high [58]. In this situation, the fermentability of starches increased the volatile fatty acids production reducing pH [65,66], the fibrolytic bacterial population [66] and colonization of fiber [67], but increasing passage rate from rumen resulting in a reduction in retention time and fiber fermentation in rumen [68]. All this explain the substitution rate between supplement and forage when the supplementation is medium to high [69]. Bargo et al. [69] found no effect of supplementation with 4.0 kg/cow/d of a concentrated feed on the NDFD when the supply of forage was limited. Gutierrez et al. [61] also observed no changes in the NDFD in cows supplemented with nitrogenous salt ad libitum or a concentrated supplement (up to approximately 3.0 kg/cow/d). Other authors have likewise reported that supplementation with mineralized salt [70] or multi-nutritional blocks does not affect the DNDF [71]. The NDFD values found in this experiment (Table 2) are among the values reported by Ismartoyo et al. [72] in diets based on Panicum maximum but lower than the value reported by Relling et al. [73] when evaluating the same grass during three seasons of the year, with three ages of regrowth.

Although the quantity of Ca and P in the MS was high (Table 1), the amount of the supplement given to and consumed by the animals was not sufficient, and negative apparent digestibility was observed for these minerals (Table 2). Negative apparent digestibility of Ca and P has been reported in cattle consuming low-quality tropical forages and reflects a mismatch between low dietary mineral intake and substantial endogenous mineral fluxes. In the case of Ca, its availability is limited by strong binding to structural components of the plant cell wall, such as uronic and phenolic acids, and by the formation of insoluble Ca–oxalate complexes common in tropical grasses [74]. These interactions reduce ruminal and post-ruminal release of Ca and also trap endogenously secreted Ca, increasing its fecal output beyond intake [75,76,77,78]. For P, apparent digestibility is even more sensitive to dietary concentration because ruminants recycle large quantities of P through saliva, and 95–98% of endogenous P is excreted in feces [34]. Consequently, when forage P is low, fecal P is dominated by endogenous sources, producing negative digestibility values, as confirmed by radiolabeled studies showing up to ~70% endogenous contribution [79]. Therefore, negative apparent digestibility of Ca and P does not indicate net loss of body reserves but rather reflects low dietary supply, extensive endogenous secretion, and mineral binding to indigestible forage fractions.

The lack of treatment effects on PDMI and TDMI (Table 2) was reflected in milk yield (Table 3), consistent with findings from Gutierrez et al. [61] and Robles et al. [52] in dual-purpose and crossbred cows grazing tropical pastures. Because milk production is closely linked to DMI, as widely documented in both tropical [80] and temperate systems [81], the absence of changes in intake likely explains the unchanged milk yield. Moreover, milk production often varies independently of supplementation due to genetic potential, lactation stage, forage availability, and management factors [82]. Although Ca and P intake increased with the PS treatment (Table 2), this did not affect PDMI, TDMI, or milk production (Table 3). Similar lack of response has been reported in studies evaluating dietary P inclusion or mineral supplementation in dairy cows [83,84].

Likewise, no effects of supplementation were observed on milk composition, in agreement with reports from Gutierrez et al. [61], Robles et al. [52], and Aguilar-Pérez et al. [85], among others [86,87]. Even in high-producing cows, increasing concentrate levels does not generally modify milk composition, as shown by Lawrence et al. [88] and Muñoz et al. [89].

For salt supplementation, the results of this study agree with those of Li et al. [90], who also found no effects on the production and composition of milk from Holstein cows in China after supplementation with mineralized salt. Pal et al. [91] also found no differences in the content of fat, lactose, protein, and non-fat solids in the milk of half-breed cows in India supplemented with salt compared to a control group. Wu et al. [92] likewise found no effect of P concentration on the composition of milk in Holstein cows fed with a fully mixed ration. Similar results have been reported with supplementation with multi-nutritional blocks. Valk and Kogut [84] observed no effect of supplementation with five mineralized blocks on the composition of milk, while Verma et al. [93] also reported no effect of supplementation with proteinized salt on the production and composition of milk in buffaloes in India. These results may be due to the fact that the responses to supplementation in the production and composition of milk are variable and depend on multiple factors such as the genetics of the animal, the stage of lactation, the availability and quality of the pastures, and management practices [84,94,95], all of which can be reflected in the digestibility, intake, and metabolic use of nutrients [53] and, therefore, in the production and composition of milk.

In modern dairy farms, achieving greater efficiency in the use of nutrients has become essential to improve profitability, considering that feed represents about 50% of total costs and is key for cows to express their genetic potential in milk production [96]. This efficiency also has a direct impact on the environmental impact of livestock systems, which is especially relevant in the face of growing concerns about climate change [97]. Considering the challenge of feeding a constantly growing world population, it has become necessary to optimize the production per unit of nutrients instead of expanding the use of resources, thereby prioritizing the sustainability of the system [98]. In this project, the efficiency in the use of four nutrients was quantified, three of which have been associated not only with the environmental impacts generated by livestock systems in various parts of the world but also because these nutrients are considered essential for the development of sustainable pasture-based livestock systems, such as N, P, and K [99]. The results obtained show that CO and MS supplementation improved the efficiency of Ca (p < 0.04) and P (p < 0.009) (Table 3) milk deposition. The average values were slightly higher than those reported by Rueda and Correa [40] in a dual-purpose herd of cows from the Department of Cesar, whose values ranged between 10% and 13.9% for Ca and between 17.0% and 19.9% for P. These values, in turn, are lower than those reported by other authors for cows in different latitudes. Thus, Taylor et al. [100] reported that deposition efficiency of Ca in the milk of Holstein cows is higher than 31.6%, while Aarons et al. [101] reported that said efficiency in Australian grazing cows can range between 8 and 76%. For P, this efficiency ranges between 4 and 48%, without explaining the factors that determine said variation. In this work, the correlations between milk production and efficiency in the deposition of Ca (r = 0.836) and P (r = 0.881 in milk (Table 4) were positive and significant (p < 0.001), thereby suggesting that improving milk production has positive effects on the use efficiency of nutrients such as Ca and P, as in the present study.

The efficiency of K deposition in milk in this study was not affected by the treatments, with values ranging between 5.81 and 6.48% (see Table 3). These low efficiencies, however, have been reported by other authors in lactating cows under different production systems. Jaimes et al. [102] found that the efficiency in the use of this mineral in Holstein cows in northern Antioquia was 6.4%, while Rueda and Correa [40] reported efficiencies between 6.4 and 9.6% in a dual-purpose tropical farm in Colombia. Likewise, the efficiency in the deposition of N in milk in this work was not affected by treatments, with averages similar to those reported by Jaimes et al. [102] in northern Antioquia with Holstein cows. The authors observed an average of 20.7%, while Rueda and Correa [40] reported slightly higher values between 26.9 and 32.2%. These results could be due to differences in nutrient content in the diet, food intake, and milk production [99].

Table 4 shows positive correlations between the efficiency of Ca, P, K, and N in milk deposition with milk production. This result suggests that by increasing milk yield in animals, the use of these nutrients for milk production can be improved. This effect represents the basis for improving the efficiency in nutrient use within milk production systems worldwide for more than a century [103], based on the principle that increasing milk production proportionally reduces the animal maintenance requirements [104]. Likewise, Table 4 shows the negative correlations between the intake of each nutrient and the milk deposition efficiency of those same nutrients. This phenomenon occurs because reducing the supply of a mineral increases its efficiency, as mentioned by Arriaga et al. [104], which argued that the best strategy to increase mineral use efficiency is to decrease its proportion in the diet.

The importance of CH4 as a greenhouse gas has led to researching and developing strategies that reduce its emissions in the world’s livestock systems [105]. CH4 emissions have been expressed in various ways with different explanations and implications for production systems management. In ruminants, such emissions can be evaluated using three indicators: CH4 production, expressed as the amount emitted per animal and per day (g/d); CH4 intensity, measured per unit of product obtained (milk or meat, g/kg); and CH4 yield, calculated per kilogram of dry matter intake (DMI) and expressed in g/kg [106]. This performance can also be related to the intake of organic matter, fiber in neutral detergent [107], or digestible organic matter [108]. According to de Haas et al. [106], CH4 production depends mainly on food intake, linked to body size and milk productivity. Intensity, on the other hand, is conditioned by the volume of milk and energy requirements, while performance reflects the methanogenic potential of the diet. The relevance of each indicator varies depending on the production system and economic context.

In this study, the means of enteric CH4 concentrations ranged between 1732 and 1911 ppm (see Table 5), without being affected by treatments. These values are within the ranges reported by Washburn and Brody [109] and Koch et al. [110], who used spirometry masks that completely covered the snouts of lactating cows. In the present study, CH4 production was not affected by treatments and averaged 196 ± 18 g/cow/d, a value consistent with previous reports for lactating cows in tropical systems [111]. The lack of differences in methane production among the CO, PS, and SM treatments can be explained by the similarity in total nutrient supply, fermentation patterns, and forage utilization across treatments. The pastures offered in this study had a chemical composition typical of tropical grasses, characterized by high NDF and low CP, and their gross energy values were within the expected range for C4 forages (Table 1). Under these conditions, the response to supplementation depends largely on whether supplements correct major nutritional limitations of the forage and stimulate changes in digestibility, intake, or rumen metabolism [53]. In this experiment, despite the differences in nutrient composition among supplements, neither PDMI nor TDMI differed among treatments, indicating that supplements did not modify overall feed intake (Table 2). Others authors [112,113] report low to zero correlation between nutritional composition of diet to cattle with CH4 production. Because CH4 output in grazing cattle is strongly driven by total dry matter intake [114,115], the absence of change in PDMI and TDMI largely explains the lack of differences in CH4 emissions.

The Ym values found in this experiment are similar to those reported by Pozo et al. [116] but slightly lower than those found by Rivera et al. [64] in dual-purpose production systems under tropical conditions. In this experiment, Ym was lower with CO (6.30%) and higher with PS (8.23%), primarily because the GEI was higher with CO but lower with PS (p < 0.05) (Table 2), while there were no differences in CH4 production between treatments (p > 0.15) (Table 4). These results reflect differences in the energy efficiency of ruminal fermentation associated with the type of supplement. Now, although with CO there was less loss of energy consumed, this was not reflected in milk production (Table 3), which is difficult to explain due to the complexity of energy transactions in the rumen and in the animal, which do not allow a clear relationship to be established between the energy lost as CH4 and the productive response of the animal [117].

Although the CO treatment increased apparent digestibility of dry matter (Table 3), the amount of supplement consumed was low (~0.9 kg DMI/cow/d), and therefore insufficient to shift the ruminal fermentation profile in a way that would materially influence CH4 production. Previous studies have shown that small amounts of starch or protein supplements can improve digestibility without altering total intake [55,56], and that changes in digestibility do not always translate into changes in methane [118] if total substrate flow to the rumen remains unchanged. Likewise, NDF digestibility was not affected by supplementation. Thus, reductions in fiber digestibility—and the associated decreases in methane—are expected only when starch supplementation is high enough to depress ruminal pH and inhibit fibrolytic bacteria, which was not the case here. The low supplementation levels also explain the absence of substitution effects on forage intake, maintaining similar total fermentable organic matter across treatments.

Taken together, these results indicate that the supplementation strategies evaluated did not meaningfully alter the quantity or fermentability of the substrate entering the rumen. Since methane production in ruminants is closely associated with fermentable organic matter intake and ruminal fermentation patterns, the similarity in PDMI, TDMI, NDFD, and overall nutrient supply across treatments resulted in comparable methane emissions. This aligns with previous reports showing that, in tropical grazing systems, supplementation at modest levels often improves nutrient balance or specific digestibility components without necessarily modifying the ruminal fermentation intensity or total organic matter intake required to influence methane output.

In the present study, CH4 production was not affected by treatments and averaged 196 ± 18 g/cow/d, a value consistent with previous reports for lactating cows in tropical systems [111]. The lower emissions compared with those reported by Rivera et al. [64] may be due to differences in forage digestibility, as the higher dry matter digestibility (DMD) observed by those authors (55–60%) would increase fermentable substrate availability in the rumen, thereby enhancing methanogenesis. In contrast, the lower DMD in the current work (46 ± 8.2%) would have constrained ruminal fermentation and reduced CH4 yield per unit of intake. Methodological factors may also contribute, since polytunnel systems quantify total CH4 emissions, whereas the equipment used here measures only cranial emissions, potentially underestimating total output. Comparisons with Primavesi et al. [119] and Villanueva et al. [120] similarly highlight that higher CH4 production in other studies is associated with greater intake of highly digestible supplements, which increases ruminal fermentability and microbial activity, ultimately elevating CH4 production alongside milk yield. This is consistent with the observed parallel increases in CH4 output and milk production across studies, reflecting the shared dependence of both processes on the supply of digestible nutrients and the intensity of ruminal fermentation.

Overall, these results indicate that variation in CH4 emissions among tropical dairy systems is primarily driven by differences in diet digestibility, supplement quality and quantity, and methodological approach, and that improvements in nutrient supply can enhance milk production while concurrently altering methanogenic potential.

The average intensity of CH4 emissions found in this experiment was 35.5 ± 12.4 g/L of milk produced, without any effect of the treatments on this variable (p < 0.35). This average is within the values reported by other authors. Primavesi et al. [119] documented an intensity of 25.3 g/L of milk for grazing mongrel cows that consumed 7.6 kg of guinea grass MS (P. maximun), were supplemented with 3.4 kg/cow/d of concentrated feed, and produced 13.3 L of milk/cow/d. On the other hand, Yassegoungbe et al. [121] observed values between 97.4 and 111.5 g of CH4/L of milk in cows belonging to small local breeds of Benin (Africa) such as white Fulani, Boboji, and Yakana, whose milk production ranged from 1.1 to 1.2 kg/cow/d. Villanueva et al. [120], however, recorded values of 16.09 g/L of milk. The above data show an inverse relationship between milk production and CH4 emission intensity, as indicated by Corredu et al. [122] and Boshe et al. [123], who reported a negative correlation of −0.25 and −0.65, respectively, between these two variables.

The intensity of CH4 emission expressed by FPCM has a linear relationship with milk production, so the previous discussion applies to this expression of CH4 emissions. Finally, CH4 emissions (g/kg TDMI), like the other variables, were not affected by the experimental treatments due to the absence of effects on dry matter intake (see Table 2) and CH4 production (see Table 5).

5. Conclusions

The dietary supplements evaluated (CO, PS, MS) in this experiment did not enhance milk yield, milk composition, or reduce enteric CH4 emissions in grazing dual-purpose cows. Therefore, this could be because the effect of supplementation on the dry matter intake on the other variables is multifactorial and affected by elements such as the quality and quantity of supplements, quality and availability of forage, and characteristics of the animal. However, CO and MS improved the efficiency of Ca and P deposition in milk, offering potential benefits for nutrient-use efficiency in tropical grazing systems. Finally, supplementation with concentrate showed less losses of gross energy as methane (Ym) due possibly, to best fermentative efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.B.C., L.J.J.C., D.M.B.V., J.E.C.F., R.B.R., J.A.B.-G., J.J.M.Z., I.D.P.G., J.M.C.A., D.A.T.V., and H.J.C.C.; investigation, B.S.B.C., L.E.R.H., P.A.M.S., A.F.A.N., M.A.M.S., D.M.B.V., J.E.C.F., R.B.R., J.A.B.-G., S.M.B.G., J.J.M.Z., I.D.P.G., J.M.C.A., D.A.T.V., and H.J.C.C.; methodology, B.S.B.C., L.E.R.H., P.A.M.S., A.F.A.N., M.A.M.S., L.J.J.C., D.M.B.V., J.E.C.F., R.B.R., J.A.B.-G., J.J.M.Z., I.D.P.G., M.V.G., D.A.T.V., and H.J.C.C.; resources, L.J.J.C., J.J.M.Z., I.D.P.G., J.M.C.A., D.A.T.V., and H.J.C.C.; supervision, L.J.J.C., I.D.P.G., J.M.C.A., M.V.G., and H.J.C.C.; software, B.S.B.C., L.J.J.C., and H.J.C.C.; formal analysis, L.E.R.H., P.A.M.S., A.F.A.N., M.A.M.S., L.J.J.C., D.M.B.V., J.E.C.F., R.B.R., J.A.B.-G., S.M.B.G., J.J.M.Z., M.V.G., D.A.T.V., and H.J.C.C.; data curation, B.S.B.C., L.E.R.H., P.A.M.S., A.F.A.N., M.A.M.S., L.J.J.C., D.M.B.V., J.J.M.Z., M.V.G., and H.J.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S.B.C., L.J.J.C., and H.J.C.C.; writing—review and editing, L.E.R.H., P.A.M.S., A.F.A.N., M.A.M.S., L.J.J.C., D.M.B.V., J.E.C.F., J.A.B.-G., S.M.B.G., J.J.M.Z., I.D.P.G., J.M.C.A., M.V.G., and D.A.T.V.; project administration, H.J.C.C.; funding acquisition, H.J.C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Universidad Nacional de Colombia throught the research project “Interfaculty alliance for the reduction in greenhouse gases in cattle farming” (HERMES 57438). This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Committee for the Care and Use of Animals of Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Campus Medellín (Antioquia) approved this study as part of the research project HERMES 57438, “Interfaculty alliance for the reduction in greenhouse gases in cattle farming” (CICUA-18-23).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jaime Bernal, owner of the Marboral farm in San Vicente del Caguán, for all his collaboration in the execution of this experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

COLANTA cooperative funded three students who participated in the experiment, in addition to the participation of a researcher who provided technical support in the conceptualization, execution, and review of the final report. The company SOMEX SAS contributed to the setup of the experiment, in addition to the participation of a researcher who provided technical support in the conceptualization, execution, data analysis and review of the final report. All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Federación Colombiana de Ganaderos (FEDEGAN). Balance y Perspectivas del Sector Ganadero Colombiano 2024–2025. 2025. Available online: https://estadisticas.fedegan.org.co/DOC/download.jsp?pRealName=Balance_perspectivas_ganaderia_colombiana_2024_2025_.pdf&iIdFiles=1121 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Healthy Diet; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- FEDEGAN. Inventario Ganadero. Federación Colombiana de Ganaderos. 2023. Available online: https://www.fedegan.org.co/estadisticas/inventario-ganadero (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Bravo Parra, A.M. Cadenas Sostenibles Ante un Clima Cambiante. La Ganadería en Colombia; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ): Bonn/Eschborn, Germany, 2021; 142p. [Google Scholar]

- Galina, C.; Turnbull, F.; Noguez-Ortiz, A. Factors affecting technology adoption in small community farmers in relation to reproductive events in tropical cattle raised under dual purpose systems. Open J. Vet. Med. 2016, 6, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orantes, M.A.; Vilaboa, A.J.; Ortega, J.E.; Córdova, A.V. Comportamiento de los comercializadores de ganado bovino en la región centro del estado de Chiapas. Rev. Quehacer Científico 2010, 1, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, H.; Aguilar, C.; Vera, R. Sistemas bovinos doble propósito en el trópico bajo de Colombia, modelo de simulación. Arch. Zootec. 2003, 52, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Guevara, C.; García Hernández, L.A.; Ávila Bello, C.H.; Brunett Pérez, L. Sustentabilidad financiera: El caso de una empresa ganadera de bovino de doble propósito. Rev. Mex. Agronegocios 2008, 22, 503–515. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Pérez, C.F.; Ku-Vera, J.C.; Magaña-Monforte, J.G. Energetic efficiency of milk synthesis in dual-purpose cows grazing tropical pastures. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2011, 43, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archimède, H.; Eugène, M.; Marie-Magdeleine, C.; Boval, M.; Martin, C.; Morgavi, D.P.; Lecomte, P.; Doreau, M. Comparison of methane production between C3 and C4 grasses and legumes. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.; Gomes, C.; Saibo, N.J.M. C4 phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase: Evolution and transcriptional regulation. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2024, 46 (Suppl. 1), e20230190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzcátegui-Varela, J.P.; Chompre, K.; Castillo, D.; Rangel, S.; Briceño-Rangel, A.; Piña, A. Nutritional assessment of tropical pastures as a sustainability strategy in dual-purpose cattle ranching in the South of Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2022, 21, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archimède, H.; Rira, M.; Eugène, M.; Fleury, J.; Lastel, M.L.; Periacarpin, F.; Silou-Etienne, T.; Morgavi, D.P.; Doreau, M. Intake, total-tract digestibility and methane emissions of Texel and Blackbelly sheep fed C4 and C3 grasses tested simultaneously in a temperate and a tropical area. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.R. Cell wall characteristics in relation to forage digestion by ruminants. J. Agric. Sci. 1994, 122, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, F.; Galina, C.; Lamothe, C.; Castañeda, O. Effect of a feed supplementation during the mid-lactating period on body condition, milk yield, metabolic profile and pregnancy rate of grazing dual-purpose cows in the Mexican humid tropic. Arch. Med. Vet. 2007, 39, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, T.A.; Mathison, E.; Cheng, K.J. Dietary, environmental and microbiological aspects of methane production in ruminants. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 76, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghorn, G.C.; Hegarty, R.S. Lowering ruminant methane emissions through improved feed conversion efficiency. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166–167, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S. Towards sustainable animal diets. Optimization of feed use efficiency in ruminant production systems. In FAO Animal Production and Health Proceedings, No. 16, Proceedings of the FAO Symposium, Bangkok, Thailand, 27 November 2012; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gaviria-Uribe, X.; Bolivar, D.M.; Rosenstock, T.S.; Molina-Botero, I.C.; Chirinda, N.; Barahona, R.; Arango, J. Nutritional quality, voluntary intake and enteric methane emissions of diets based on novel Cayman grass and its associations with two Leucaena shrub legumes. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 579189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Eggleston, H.S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., Tanabe, K., Eds.; IPCC National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme: Hayama, Japan, 2006; Volume 4, Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara, M.; Magner, T.; Hunter, R.A.; McCrabb, G.J. Methane production and energy partition of cattle in the tropics. Br. J. Nutr. 1999, 81, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommart, K.; Kaewpila, C.; Kongphitee, K.; Subepang, S.; Phonbumrung, T.; Ogino, A.; Suzuki, T. Methane emissions and energy utilization of zebu cattle in the tropics. In IRCAS-NARO International Symposium on Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Mitigation; Tsukuba International Congress Center: Ibaraki, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.A.; Johnson, D.E. Methane emissions from cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M.F.; Franzluebbers, A.J.; Lachnicht, S.; Reicosky, D.C. Agricultural opportunities to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 150, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GHG Protocol Initiative. IPCC Global Warming Potential Values (Version 2.0); GHG Protocol: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Beauchemin, K.A.; Ungerfeld, E.M.; Eckard, R.J.; Wang, M. Fifty years of research on rumen methanogenesis: Lessons learned and future challenges for mitigation. Animal 2020, 14, s2–s16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Kenny, D.; Roskam, E.; O’Rourke, M.; Kelly, A.; Hayes, M.; Kirwan, S.; Waters, S. Strategies to Reduce Methane Emissions from Irish Beef Production; Teagasc: Carlow, Ireland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.I.M.; Wassie, S.E.; Korir, D.; Merbold, L.; Goopy, J.P.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Dickhoefer, U.; Schlecht, E. Supplementing tropical cattle for improved nutrient utilization and reduced enteric methane emissions. Animals 2019, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorga Mogollón, O.L. Cuantificación de emisiones de gas metano entérico en ganado bovino de carne y leche. In Conversatorios Sobre Ganadería Sostenible; AGROSAVIA: Carlow, Ireland, 2020; 28p, Available online: https://sociedadsostenible.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/0521-Olga-Mayorga.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Díaz, T. Alimentación de vacas en explotaciones doble propósito. In Alimentación de Vacas; Díaz, E.T., Ed.; Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario: Bogotá, Colombia, 1988; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, H.; Rubiano, J. Suplementación de vacas doble propósito en pastoreo, con núcleos energético-proteínicos en fase de lactancia en el departamento del Tolima. In Monografía; CORPOICA: Bogotá, Colombia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, H.J.; Jaimes, L.J. Design and operation of a spirometry mask to quantify exhaled methane emission by grazing cattle. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2023, 35, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Basto, M.B. Zonas de vida en el departamento del Caquetá, Colombia, basadas en los escenarios de emisión de cambio climático para el período 2011–2100 y estrategias educativas de adaptación para el manejo de las plantaciones de Hevea brasiliensis. Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Surcolombiana, Huila, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. The Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 7th ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Committee on Agriculture (SCA). Feeding Standards for Australian Livestock. Ruminants; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 1990; 226p. [Google Scholar]

- Jaimes, L.J.; Castrillón, S.; Bustamante, B.S.; Correa, H.J. Through the Mouth or Nostrils: The methane Excretion Route in Belching Dairy Cows. Animals 2025, 15, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaimes, L.J.; Cerón, J.M.; Correa, H.J. Season and stage of lactation affects feed intake of Holstein cows grazing Kikuyo (Cenchrus clandestinus) in Colombia. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2015, 27. Available online: https://www.lrrd.org/lrrd27/12/jaim27244.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Jaimes-Cruz, L.J.; Escobar-Riomalo, J.E.; Muñoz, S.; Correa-Cardona, H.J. Measurement of fermentation gas production with ruminant feed using a demonstrative continuous flow biodigester. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2024, 77, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, L.E.; Cook, C.W.; Butcher, J.E. Symposium on forage evaluation: 5. Intake and digestibility techniques and supplemental feeding in range forage evaluation. Agron. J. 1959, 51, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, S.; Mastranyero Heffer, J.; Correa, H.J. Consumo y respuesta animal de vacas de doble propósito suplementadas con torta de palmiste y paja de arroz sometidas a tratamientos de deslignificación. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2021, 33, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Lippke, H. Estimation of forage intake by ruminants on pasture. Crop Sci. 2002, 42, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerken, C.M.; Calzadilla, D.; González, R. Aplicación de la técnica de dos marcadores para medir el consumo de pasto y la digestibilidad de la ración de vacas en pastoreo suplementadas con concentrado. Pastos Y Forrajes 1987, 10, 266–273. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 9622/IDF 141:2013; Milk and Milk Products—Guide to the Preparation of Samples and Dilutions for Microbiological Examination. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle: Eighth Revised Edition; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 21st ed.; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B. Analysis of Forages and Fibrous Foods: A Laboratory Manual for Animal Science; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Marumo, J.L.; LaPierre, P.A.; Van Amburgh, M.E. Enteric methane emissions prediction in dairy cattle and effects of monensin on methane emissions: A meta-analysis. Animals 2023, 13, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Dairy Sector: A Life Cycle Assessment; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2010; Available online: https://www.uncclearn.org/wp-content/uploads/library/fao149.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Juárez, F.; Contreras, J.; Montero, M. Tasa de Cambios Con Relación a Edad en Rendimiento, Composición Química y Digestibilidad de Cinco Pastos Tropicales; Universidad de Veracruz, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia: Heroica Veracruz, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Korir, D.; Marquardt, S.; Eckard, R.; Sánchez, A.; Dickhoefer, U.; Merbold, L.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Jones, C.; Robertson-Dean, M.; Goopy, J. Weight gain and enteric methane production of cattle fed on tropical grasses. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2023, 63, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Anzueta, S.; Molina-Botero, I.C.; Ramírez-Navas, J.S.; Rao, I.; Chirinda, N.; Barahona-Rosales, R.; Arango, J. Nutritional evaluation of tropical forage grass alone and grass-legume diets to reduce in vitro methane production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, J.L.E.; Xochitemol, H.A.; Benaouda, M.; Osorio, A.J.; Corona, L.; Castillo, G.E.; Castelan, O.O.A.; Gonzalez-Ronquillo, M. Concentrate supplementation on milk yield, methane and CO2 production in crossbred dairy cows grazing in tropical climate regions. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2021, 9, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Berça, A.S.; Silva, M.L.C.; Leite, R.G.; Dallantonia, E.E.; Romanzini, E.P.; Barbero, R.P.; da Silva Cardoso, A.; Lage, J.F.; Tedeschi, L.O. Effects of supplement type during the pre-finishing growth phase on subsequent performance of Nellore bulls finished in confinement or on tropical pasture. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2022, 38, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carulla, J.; Cárdenas, E.; Sánchez, N.; Riveros, C. Valor nutricional de los forrajes más usados en los sistemas de producción lechera especializados de la zona andina colombiana. In Seminario Nacional de Lechería Especializada: Bases Nutricionales y su Impacto en la Productividad; Eventos y Asesorías Agropecuarias UE: Plaza Mayor, Medellín, 2004; pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, M.N.N.; Estrada-Aniello, M.; Zadoks, R.N. Strategies of energy supplementation for cattle fed tropical forages. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2023, 306, 115371. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarini, I.; Detmann, E.; Paulino, M.F.; Valadares Filho, S.C.; Valadares, R.F.D.; Oliveira, F.A.; Silva, P.T.; Reis, W.L.S. Nutritional performance of cattle grazing on low-quality tropical forage supplemented with nitrogenous compounds and/or starch. Rev Bras Zootecn 2013, 42, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, W.P. Optimizing and evaluating dry matter intake of dairy cows. In Advances in Dairy Technology; WCDS: Huntly, VA, USA, 2015; Volume 27, pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bargo, F.; Muller, L.; Kolver, E.; Delahoy, J. Production and digestion of supplemented dairy cows on pasture. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.W.; Gunter, S.A.; Sprinkle, J.E.; Neel, J.P.S. Beef Species Symposium: Difficulties associated with predicting forage intake by grazing beef cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 2775–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, S. Suplementos múltiplos de baixo consumo para recria de bovinos em capim Aruana. Tesis de Maestría, Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná, Campus Dois Vizinhos, Dois Vizinhos, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, G.S.; Lana, R.P.; Rivelli, L.R.; de Carvalho, A.U.; de Moraes, É.H.B.K. Performance of crossbred lactating cows at grazing in response to nitrogen supplementation and different levels of concentrate feed. Arq. Bras. Med. Veterinária E Zootec. 2019, 71, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, X.H.; Chen, Y.X.; Cheng, Z.H.; Duan, Q.H.; Meng, Q.H.; Tao, X.P.; Shang, B.; Dong, H.M. Age-related response of rumen microbiota to mineral salt and effects of their interactions on enteric methane emissions in cattle. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 73, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Coello, G.; Hernández-Medrano, J.H.; Ku-Vera, J.; Diaz, D.; Solorio-Sánchez, F.J.; Sarabia-Salgado, L.; Galindo, F. Intensive silvopastoral systems mitigate enteric methane emissions from cattle. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.E.; Villegas, G.; Chará, J.; Durango, S.G.; Romero, M.A.; Verchot, L. Effect of Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) A. Gray intake on in vivo methane emission and milk production in dual-purpose cows in the Colombian Amazonian piedmont. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2022, 6, txac139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, J.; Ellis, J.L.; Kebreab, E.; Strathe, A.B.; Lopez, S.; France, J.; Bannink, A. Ruminal pH regulation and nutritional consequences of low pH. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 172, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Wang, Z.; Guo, L.; Li, F.; Li, F.; Liang, Y.; Tang, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Effects of supplementation of nonforage fiber source in diets with different starch levels on growth performance, rumen fermentation, nutrient digestion, and microbial flora of Hu lambs. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2021, 5, txab065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B.; Wilson, D.B. Why are ruminal cellulolytic bacteria unable to digest cellulose at low pH? J. Dairy Sci. 1996, 79, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Rosa, M.M.; Bosher, T.J.; Khan, M.A.; Sandoval, E.; Dobson-Hill, B.; Duranovich, F.N.; Jonker, A. Effect of supplementing high-fiber or high-starch concentrates or a 50:50 mix of both to late-lactation dairy cows fed cut herbage on methane production, milk yield, and ruminal fermentation. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 7036–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargo, F.; Müller, L.D.; Kolver, E.S.; Delahoy, J.E. Milk response to concentrate supplementation of high-producing dairy cows grazing at two pasture allowances. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 1777–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis, I.U.; Agus, A.; Astuti, A.; Yusiati, L.M.; Anas, M.A. Effect of mineral premix supplementation on intake and digestibility of repeat breeder cows. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1183, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, V.; Singh, P.; Patil, A.K.; Verma, A.K.; Das, A. Influence of urea molasses mineral blocks having bentonite as binder on the feed intake, nutrient utilization and economics of feeding of crossbred calves. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 91, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismartoyo, I.; Suryani, N.N.; Koten, B.B.; Ingratubun, J. The feed ADF and NDF digestibility of goat fed four different diets. Hasanuddin J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 4, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Relling, E.A.; Van Niekerk, W.A.; Coertze, R.J.; Rethman, N.F.G. An evaluation of Panicum maximum cv. Gatton: 2. The influence of stage of maturity on diet selection, intake and rumen fermentation in sheep. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 31, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuele, S.M.; Staples, C.R. Ruminal release of minerals from six forage species. J. Anim. Sci. 1990, 68, 2052–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Rivera, J.; Morris, M.P. Oxalate content of tropical forage grasses. Science 1955, 122, 1089–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaney, B.J.; Gartner, R.J.W.; Head, T.A. Effects of oxalate in tropical grasses on calcium, phosphorus and magnesium availability to cattle. J. Agric. Sci. 1982, 99, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, F.; Correa, H.J. Digestibilidad posruminal aparente de la materia seca, la proteína cruda y cuatro macrominerales en el pasto kikuyo (Pennisetum clandestinum) cosechado a dos edades de rebrote. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2006, 18, 143. Available online: http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd18/10/caro18143.htm (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Owen, E.C. The effect of thyroxine on the metabolism of lactating cows. 2. Calcium and phosphorus metabolism. Biochem. J. 1948, 43, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, M.; Smith, A.H.; Ralston, N.P.; Black, A.L. Radiophosphorus (P32) as tracer for measuring endogenous phosphorus in cow’s feces. J. Nutr. 1951, 45, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgel, A.L.C.; dos Santos, G.T.; Ítavo, L.C.V.; Ítavo, C.C.B.F.; Difante, G.d.S.; Dias, A.M.; Longhini, V.Z.; Dias-Silva, T.P.; de Araújo, M.J.; Neto, J.V.E.; et al. Mathematical models to predict dry matter intake and milk production by dairy cows managed under tropical conditions. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N.; Price, W.J.; Shafii, B. A meta-analysis examining the relationship among dietary factors, dry matter intake, and milk and milk protein yield in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 2184–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudracco, J.; Lopez-Villalobos, N.; Holmes, C.W.; Macdonald, K.A. Effects of stocking rate, supplementation, genotype and their interactions on grazing dairy systems: A review. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 53, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, H.; Kanitz, F.D.; Moreira, V.R.; Satter, L.D.; Wiltbank, M.C. Effect of dietary phosphorus on performance of lactating dairy cows: Milk production and cow health. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valk, H.; Kogut, J. Salt block intake by high-yielding dairy cows fed rations with different amounts of NaCl. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1998, 56, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Pérez, C.; Ku-Vera, J.; Centurión-Castro, F.; Garnsworthy, P.C. Energy balance, milk production and reproduction in grazing crossbred cows in the tropics with and without cereal supplementation. Livest. Sci. 2009, 122, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Islam, M.Z.; Barman, K.K.; Bari, M.S.; Habib, M.R.; Rashid, M.H.; Islam, M.A. Impact of concentrate supplementation on extended transitional crossbred Zebu cow’s performances. J. Bangladesh Agric. Univ. 2020, 18, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faría Mármol, J.; Chirinos, Z.; Morillo, D.E. Efecto de la sustitución parcial del alimento concentrado por pastoreo con Leucaena leucocephala sobre la producción y características de la leche y variación de peso de vacas mestizas. Zootec. Trop. 2007, 25, 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, D.C.; O’Donovan, M.; Boland, T.M.; Lewis, E.; Kennedy, E. The effect of concentrate feeding amount and feeding strategy on milk production, dry matter intake, and energy partitioning of autumn-calving Holstein-Friesian cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, C.; Herrera, D.; Hube, S.; Morales, J.; Ungerfeld, E.M. Effects of dietary concentrate supplementation on enteric methane emissions and performance of late lactation dairy cows. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 78, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Shi, R.; Cheng, Z.; Dong, H. Effects of mineral salt supplement on enteric methane emissions, ruminal fermentation and methanogen community of lactating cows. Anim. Sci. J. 2017, 88, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, K.; Maji, C.; Kumar Das, M.; Banerjee, S.; Saren, S.; Tudu, B. Effects of Area Specific Mineral Mixture (ASMM) supplementation on production and reproductive parameters of crossbred and desi cows: A field study. Res. Biot. 2020, 2, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Satter, L.D.; Sojo, R. Milk production, reproductive performance, and fecal excretion of phosphorus by dairy cows fed three amounts of phosphorus. J. Dairy Sci. 2000, 83, 1028–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.K.; Kumar, P.; Adil, A.; Arya, G.K. Effect of feed supplement on milk production, fat %, total serum protein and minerals in lactating buffalo. Vet. World 2009, 2, 193–194. [Google Scholar]

- Boukrouh, S.; Noutfia, A.; Moula, N.; Avril, C.; Hornick, J.-L.; Chentouf, M.; Cabaraux, J.-F. Effects of Sulla Flexuosa Hay as Alternative Feed Resource on Goat’s Milk Production and Quality. Animals 2023, 13, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukrouh, S.; Mnaouer, I.; Mendes de Souza, P.; Hornick, J.-L.; Nilahyane, A.; El Amiri, B.; Hirich, A. Microalgae supplementation improves goat milk composition and fatty acid profile: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2025, 68, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandeHaar, M.J. Efficiency of nutrient use and relationship to profitability on dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 1998, 81, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; de Haan, C. Livestock’s Long Shadow; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza, J.; Batistel, F.; Santos, F.A.P. Enhancing the recovery of human-edible nutrients in milk and nitrogen efficiency throughout the lactation cycle by feeding fatty acid supplements. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1186454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, D.B.D.; Lopes, M.L.S.; Izidro, J.L.P.S.; Bezerra, R.C.A.; Gois, G.C.; de Amaral, T.N.E.; da Silva Dias, W.; de Barros, M.M.L.; da Silva Oliveira, A.R.; De Farias Sobrinho, J.L.; et al. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium cycling in pasture ecosystems. Ciência Anim. Bras./Braz. Anim. Sci. 2024, 25, e-76743E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.S.; Knowlton, K.F.; McGilliard, M.L.; Swecker, W.S.; Ferguson, J.D.; Wu, Z.; Hanigan, M.D. Dietary calcium has little effect on mineral balance and bone mineral metabolism through twenty weeks of lactation in Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarons, S.R.; Gourley, C.J.P.; Powell, J.M. Nutrient intake, excretion and use efficiency of grazing lactating herds on commercial dairy farms. Animals 2020, 10, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaimes Cruz, L.J.; Correa Cardona, H.J. Balance de nitrógeno, fósforo y potasio en vacas Holstein pastando praderas de kikuyo (Cenchrus clandestinus) en el norte de Antioquia. CES Med. Vet. Y Zootec. 2016, 11, 18–41. Available online: https://revistas.ces.edu.co/index.php/mvz/article/view/3959 (accessed on 18 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- VandeHaar, M.J.; St-Pierre, N. Major advances in nutrition: Relevance to the sustainability of the dairy industry. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, H.; Pinto, M.; Calsamiglia, S.; Merino, P. Nutritional and management strategies on nitrogen and phosphorus use efficiency of lactating dairy cattle on commercial farms: An environmental perspective. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseten, T.; Sanjorjo, R.A.; Kwon, M.; Kim, S.W. Strategies to mitigate enteric methane emissions from ruminant animals. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, Y.; Pszczola, M.; Soyeurt, H.; Wall, E.; Lassen, J. Invited review: Phenotypes to genetically reduce greenhouse gas emissions in dairying. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGeough, E.J.; Passetti, L.C.G.; Chung, Y.H.; Beauchemin, K.A.; McGinn, S.M.; Harstad, O.M.; Crow, G.; McAllister, T.A. CH4 emissions, feed intake, and total tract digestibility in lambs fed diets differing in fat content and fibre digestibility. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 99, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medjadbi, M.; García Rodríguez, A.; Atxaerandio, R.; Charef, S.E.; Picault, C.; Ibarruri, J.; Iñarra, B.; San Martín, D.; Serrano Pérez, B.; Martín Alonso, M.J.; et al. Response of rumen methane production and microbial community to different abatement strategies in yaks. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, L.E.; Brody, S. Growth and development with special reference to domestic animals. XLII. In CH4, Hydrogen, and Carbon Dioxide Production in the Digestive Tract of Ruminants in Relation to the Respiratory Exchange; Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station, Research Bulletin: Columbia, MO, USA, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, A.-K.S.; Nørgaard, P.; Hilden, K. A new method for simultaneous recording of methane eructation, reticulo-rumen motility and jaw movements in rumen fistulated cattle. In Ruminant Physiology: Digestion, Metabolism, and Effects of Nutrition on Reproduction and Welfare; Chilliard, Y., Glasser, F., Faulconnier, Y., Bocquier, F., Veissier, I., Doreau, M., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 360–361. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, R.S.; Rodrigues, J.P.P.; Maurício, R.M.; Borges, A.L.C.C.; Reis e Silva, R.; Berchielli, T.T.; Valadares Filho, S.C.; Machado, F.S.; Campos, M.M.; Ferreira, A.L.; et al. Predicting enteric methane production from cattle in the tropics. Animal 2020, 14, s438–s452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.A.; Kebreab, E.; Yates, C.M.; Crompton, L.A.; Cammell, S.B.; Dhanoa, M.S.; Agnew, R.E.; France, J. Alternative approaches to predicting methane emissions from dairy cows. J Anim Sci 2003, 81, 3141–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muetzel, S.; Hannaford, R.; Jonker, A. Effect of animal and diet parameters on methane emissions for pasture-fed cattle. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2024, 64, AN23049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, L.S.; Souza, L.L.; Gianvecchio, S.B.; de Oliveira, M.H.V.; Silva, J.A.I.V.; Canesin, R.C.; Branco, R.H.; Baccan, M.; Berndt, A.; de Albuquerque, L.G.; et al. Phenotypic association among performance, feed efficiency and methane emission traits in Nellore cattle. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.-R.; Lee, S.; Jung, H.; Miller, D.N.; Chen, R. Enteric methane emissions and animal performance in dairy and beef cattle production: Strategies, opportunities, and impact of reducing emissions. Animals 2022, 12, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Leyva, D.; Casanova-Lugo, F.; López-González, F.; Celis-Álvarez, M.D.; Cruz-Tamayo, A.A.; Canúl-Solís, J.R.; Chay-Canúl, A.J. Impact of diversified grazing systems on milk production, nutrient use and enteric methane emissions in dual-purpose cows. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2024, 56, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgavi, D.P.; Cantalapiedra-Hijar, G.; Eugène, M.; Martin, C.; Noziere, P.; Popova, M.; Ortigues-Marty, I.; Muñoz-Tamayo, R.; Ungerfeld, E.M. Review: Reducing enteric methane emissions improves energy metabolism in livestock: Is the tenet right? Animal 2023, 17 (Suppl. 3), 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulyatt, M.J.; Lassey, K.R. Methane emissions from pastoral systems: The situation in New Zealand. Arch. Latinoam. Prod. Anim. 2001, 9, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Primavesi, O.; Shiraishi Frighetto, R.T.; Pedreira, M.d.S.; de Lima, M.A.; Berchelli, T.T.; Barbosa, P.F. Dairy cattle enteric methane measured in Brazilian tropical conditions. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2004, 39, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, C.; Ibrahim, M.; Castillo, C. Enteric methane emissions in dairy cows with different genetic groups in the humid tropics of Costa Rica. Animals 2023, 13, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassegoungbe, F.P.; Vihowanou, G.S.; Onanyemi, T.; Assouma, M.H.; Schlecht, E.; Dossa, L.H. Enteric methane production, yield, and intensity in smallholder dairy farming systems in peri-urban areas of coastal West African countries: Case study of Benin. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2024, 3, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]