Simple Summary

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a significant health concern in dogs and cats and have public health implications, as companion animals can serve as reservoirs for pathogenic and multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria. In the study period, the estimated prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats associated with LUTDs or other illnesses was 26.1%, with true values ranging from 8.0% to 58.9%. Prevalence was higher in dogs than cats and higher in females than in male, and all age groups were affected. Escherichia coli was the predominant causative bacterium, and prevalence remained stable over time.

Abstract

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) occur in dogs and cats across diverse populations and regions. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we estimated the pooled prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats with lower urinary tract diseases (LUTDs) or other illnesses and characterized the distribution of bacterial uropathogens. A comprehensive search of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science identified 887 articles, of which 18 were published up to October 2024, met the inclusion criteria. Meta-analyses using a random-effects model estimated a pooled prevalence of 26.1%. Prevalence was greater in dogs (44.6%) than in cats (18.6%), and higher in females (30.1%) than in males (14.6%), affecting all age groups. Single-pathogen infections predominated, with Escherichia coli being the most common uropathogen in both species, followed by Proteus spp. and Staphylococcus spp. in dogs and Staphylococcus spp. in cats. Prevalence remained relatively constant over the study period (1991–2021). These findings underscore the value of pooled prevalence and bacterial distribution data for guiding empirical antimicrobial selection, and they highlight the need for further systematic reviews on antimicrobial susceptibility and multidrug resistance to inform treatment strategies.

1. Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a common clinical issue in dogs and cats and are generally classified as either simple (uncomplicated) or complicated UTIs. The former—also referred to as sporadic bacterial cystitis—are characterized by bacterial infection of the bladder that leads to inflammation and lower urinary tract signs, including pollakiuria, dysuria, hematuria, periuria, and urinary incontinence, in animals with otherwise normal urinary tract anatomy and function. In contrast, a complicated UTI is associated with anatomical or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract that predispose an animal to persistent or recurrent infections [1,2]. Subclinical bacteriuria is characterized by the isolation of bacteria via urine culture in the absence of clinical signs or cytological evidence of inflammation [1,2]. In more advanced cases, pyelonephritis may develop as a consequence of an ascending bacterial infection originating in the lower urinary tract [3].

Similarly to other infectious diseases, UTIs pose a significant public health concern, as dogs and cats can serve as reservoirs for pathogenic and multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial strains. These strains have the potential to be transmitted across species through close contact with household members, thereby increasing the risk of zoonotic infections in humans [4,5,6]. In addition, the overuse and misuse of antimicrobial agents have substantially contributed to the emergence and spread of resistant bacterial populations [7,8]. Consequently, newly emerged pathogenic strains exhibiting multidrug resistance may lead to therapeutic failure. This growing crisis underscores the urgent need for the development and discovery of novel antimicrobial agents to combat life-threatening infections [9].

The selection of antimicrobial therapy in clinical practice relies on clinical manifestations (e.g., sporadic bacterial cystitis and subclinical bacteriuria), bacterial culture, and antimicrobial susceptibility. Antimicrobials are the mainstay of treatment for sporadic bacterial cystitis; however, they are generally not recommended for subclinical bacteriuria [1]. Studies on the prevalence of UTIs contribute to public health awareness; additionally, information on the type and proportion of pathogenic bacteria causing UTIs, as well as patterns of antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance, is essential for developing empirical antimicrobial guidelines prior to the availability of culture and susceptibility results [10,11,12].

UTIs account for a substantial proportion of lower urinary tract diseases (LUTDs) in dogs and cats, and various other illnesses may predispose these animals to UTIs. Comorbidities associated with urinary tract infections include chronic kidney disease, hyperadrenocorticism, diabetes mellitus, and urinary bladder dysfunction secondary to thoracolumbar intervertebral disk disease [13,14,15,16,17]. However, the prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats, their temporal trends, and the spectrum of causative uropathogens have not been comprehensively characterized. To address this gap, in the present study, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the population-based literature to estimate the prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats with LUTDs or other conditions. Furthermore, we evaluated geographic distribution, species, sex, age, diagnostic thresholds, sampling methods, temporal trends, and the types and relative proportions of bacterial uropathogens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Questions

The review questions were developed using the PECO framework [18], in which P denotes the study population, E the exposure of interest, C the comparator group, and O the disease outcome. Specifically, this review addressed the following questions: (1) What is the prevalence of bacterial UTIs in dogs and cats with LUTDs and other illnesses? (2) Which bacterial species are most frequently associated with for UTIs in these animal populations?

2.2. Search Strategy

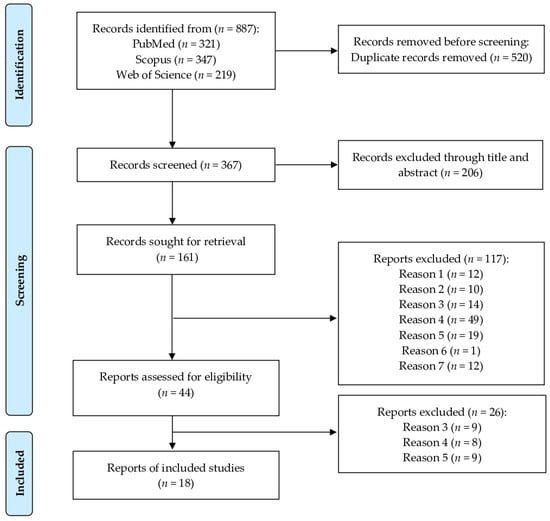

Our protocol was developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across three electronic databases—PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science—to identify relevant studies published up to October 2024, without restrictions on publication date. The search strategy employed Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms used individually or in combination as follows: (urinary tract infections OR cystitis OR pyelonephritis OR bacteriuria) AND (epidemiology OR prevalence OR incidence) AND (dogs OR canine OR cats OR feline). Data were extracted at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Thailand. All retrieved citations were systematically screened to determine their eligibility based on predefined inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the data search, extraction, and selection process. The literature search yielded 887 articles, of which 18 studies were included in the final review. The excluded studies were categorized as follows: Reason 1—studies that did not investigate naturally occurring bacterial UTIs; Reason 2—studies conducted on species other than dogs and cats; Reason 3—studies with no documented clinical signs related to urinary tract disease or studies focused exclusively on cases of subclinical bacteriuria; Reason 4—studies that did not report diagnostic testing for UTIs, lacked urine sample collection, or did not perform urine culture; Reason 5—studies with the following designs: randomized controlled trials, review articles, case reports, case series, case–control studies, editorials, conference abstracts, or short communications; Reason 6—articles not published in English; Reason 7—studies for which the full text was not available for download.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Eligible articles were initially screened by two independent reviewers based on their titles and abstracts. If the eligibility of a study could not be determined from this alone, the full text was retrieved for further assessment. Studies were included or excluded from this review based on whether they met the predefined eligibility criteria outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of this study.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data were extracted from studies that fulfilled the eligibility criteria using standardized Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. The extracted variables encompassed the name of the first author, publication year, year of sample collection, study location (country and continent), journal of publication, study design, species of subjects, population characteristics, sampling method, detection technique and diagnostic criteria, age and gender of the study population, sample size, and number of identified UTIs cases.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The included studies were independently evaluated by two reviewers (R1 and R2) using a standardized critical appraisal tool, consisting of 9 questions and adapted from the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data [19]. The assessment criteria were as follows: Q1: Was the sample frame appropriate to address the target population? Q2: Were study participants sampled in an appropriate way? Q3: Was the sample size adequate? Q4: Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? Q5: Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? Q6: Were valid methods used for the identification of the condition? Q7: Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants? Q8: Was there appropriate statistical analysis? Q9: Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately? To evaluate the methodological quality of each study, a scoring system was applied to each checklist item: Yes (score = 1), No (score = 0), and Unclear (score = 0). To ensure reliability, all studies were independently double assessed by the two reviewers. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus; if agreement could not be achieved, a third reviewer was consulted. Inter-rater agreement was quantified using Cohen’s κ coefficient, which measures the level of agreement beyond chance. The strength of agreement was interpreted according to conventional guidelines: slight (κ = 0.00–0.20), fair (κ = 0.21–0.40), moderate (κ = 0.41–0.60), substantial (κ = 0.61–0.80), and almost perfect (κ = 0.81–1.00).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All data extracted from the prepared Excel spreadsheet were imported into the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software, Biostat version 4 (Englewood, NJ, USA), for further statistical analysis. The logit transformation was applied to stabilize variance before pooling data from individual studies, defined as logit(p) = ln[p/(1 − p)], where p represents the proportion and ln denotes the natural logarithm [19]. The pooled prevalence of UTIs was then reported as a point estimate with a 95% confidence interval (CI), following back-transformation to enhance interpretability. The prediction interval (PI) was also calculated to evaluate the distribution of the true pooled prevalence in the population. A random-effects model was employed for all meta-analyses, based on the assumption of variability in settings among the included studies. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses, unless otherwise specified. Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q statistic (Q test), while the I2 statistic was used to quantify the degree of heterogeneity. I2 values of 25.0%, 50.0%, and 75.0% were interpreted as representing low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [20]. In addition, a descriptive analysis was performed to summarize the prevalence (median and range) of bacterial isolates identified from urine cultures.

2.6.1. Overall Meta-Analysis

To obtain an overall estimate of UTI prevalence, a meta-analysis was conducted combining data from dogs and cats, with individual studies used as the units of analysis to calculate the overall pooled prevalence.

2.6.2. Subgroup Meta-Analysis

Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential sources of heterogeneity based on various study characteristics. For comparisons of cohort characteristics, studies were stratified into those involving UTIs with LUTDs and UTIs and other illnesses. UTI prevalence was also analyzed separately by region (Asia, Europe, and North America), species (dogs and cats), gender (male, female, and unspecified), age group (<10 years, ≥10 years, and unspecified), diagnostic threshold (103 CFU/mL, and unspecified), and sampling method (cystocentesis and unspecified).

2.6.3. Meta-Regression

Subgroup analysis was limited to one categorical variable at a time. Therefore, to explore potential sources of heterogeneity incorporating both categorical and continuous covariates in the prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats, both univariable and multivariable meta-regression analyses were conducted. Although the results of the former were similar to those of the subgroup analysis, the results of the multivariable meta-regression accounted for the other confounding variables in the model. Covariates included in the analyses were the following: study year, cohort type, continent, species, sex, age, diagnostic threshold, and sampling methods. For each covariate, univariable meta-regression was used to estimate regression coefficients and crude odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All covariates were then included in a multivariable meta-regression model to obtain coefficients and adjusted ORs. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.7. Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate the robustness of the pooled prevalence estimates for UTIs in dogs and cats, sensitivity analyses were conducted as follows. First, both fixed-effects and random-effects models were applied to examine their influence on the estimates. Second, a leave-one-out analysis sequentially excluded each study to assess the impact of individual studies on the overall results. Third, the effect of inclusion criteria was examined by comparing analyses including only UTIs and UTIs with illnesses versus those including all available data.

2.8. Publication Bias

Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot, complemented by formal statistical assessments employing Begg’s test [21] and Egger’s test [22]. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was interpreted as indicative of potential publication bias. In instances of funnel plot asymmetry, the trim-and-fill method [23] was applied to estimate potentially missing studies and to provide an adjusted pooled prevalence.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search and Study Characteristics

A total of 887 articles were identified through a systematic search of three electronic databases: PubMed (n = 321), Scopus (n = 347), and Web of Science (n = 219). After the removal of duplicate records, 367 articles were retained for further screening. Titles and abstracts were then reviewed, and studies were excluded if they did not meet the predefined inclusion criteria. As a result, 18 articles were deemed eligible and included in this meta-analysis [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Detailed characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2. Of the 18 included studies, 5 reported data on dogs, 10 on cats, and 3 on both dogs and cats. Additionally, 15 studies provided data on the prevalence of bacterial isolates identified from the urine of dogs and cats with UTIs.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 18 studies included in this meta-analysis.

3.2. Assessment of Study Quality

The methodological quality of the 18 included studies was appraised using the JBI critical appraisal checklist for prevalence research (Table 3). Overall, the studies demonstrated moderate to high methodological quality. All (100%) had an appropriate sample frame and adequate sample size and applied appropriate statistical analyses. Moreover, all reported valid and reliable methods for condition identification and measurement, although only 61% (11/18) fully met these criteria. Appropriate sampling methods were employed in 83% (15/18) of studies, while 67% (12/18) adequately described study subjects and settings. Data analyses were considered to sufficiently cover the identified sample in 61% (11/18) of the studies. The item concerning response rate was not applicable. All studies were independently assessed by two reviewers (R1 and R2) with complete data, and the inter-rater agreement was substantial (Cohen’s κ = 0.764; SE = 0.053; t = 12.697; p < 0.001).

Table 3.

The study quality assessment presents the number of included studies within each category of a simplified rating scale, based on a nine-item evaluation checklist.

3.3. Overall Prevalence Estimates

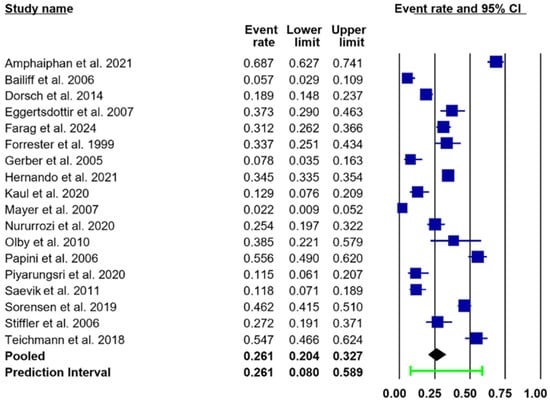

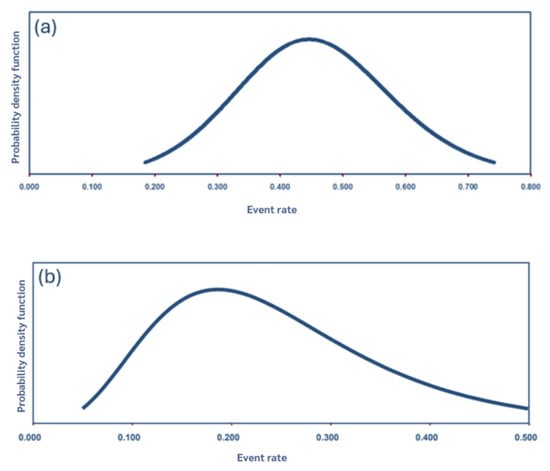

Of the 18 included studies, the pooled prevalence of UTIs in both dogs and cats, estimated using a random-effects model, was 26.1% (95% CI: 20.4–32.7.9%; PI: 8.0–58.9), as illustrated in Figure 2 and Table 4. Distribution and point estimates of this prevalence are illustrated in Figure 3. A substantial level of heterogeneity was observed across the studies (I2 = 95.8%). Subgroup analysis suggested that variations in species and sex were the primary contributors to the observed heterogeneity.

Figure 2.

Forest plots illustrating an estimated pooled prevalence of UTIs (black diamond) of 26.1% (95% CI: 20.4–32.7%; PI: 8.0–58.9) in both dogs and cats [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PI, prediction interval (green line). The event rate and its 95% confidence interval (CI) for each study are represented by a navy-blue square.

Table 4.

Overall and subgroup meta-analyses of the prevalence of urinary tract infections in dogs and cats with lower urinary tract diseases and other illnesses.

Figure 3.

Distribution and point estimates of the pooled prevalence of UTIs in dogs (a) and cats (b).

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

3.4.1. Cohort-Specific Prevalence

The pooled prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats with LUTDs was 29.9% (95% CI: 23.9–36.8%; PI: 10.7–60.5), and that of UTIs with other illnesses was 20.1% (95% CI: 8.5–40.7%; PI: 0.6–90.6). However, this difference was not statistically significant (Table 4).

3.4.2. Continent-Specific Prevalence

The prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats was reported in 17 studies: 3 from Asia, 9 from Europe, and 5 from North America. Asia exhibited the highest pooled prevalence at 36.0% (95% CI: 12.5–68.9%; PI: 0.1–99.8), followed by Europe at 29.5% (95% CI: 22.7–37.2%; PI: 10.3–60.2) and North America at 15.3% (95% CI: 5.9–34.3%; PI: 0.3–91.4). However, these regional differences were not statistically significant (Table 4).

3.4.3. Species-Specific Prevalence

The pooled prevalence of UTIs was 44.6% (95% CI: 36.0–53.6%; PI: 18.5–74.1) in dogs and 18.6% (95% CI: 13.6–25.0%; PI: 5.0–49.9) in cats; it was significantly higher in dogs than it was in cats (p < 0.001), as illustrated in Table 4.

3.4.4. Sex-Specific Prevalence

Of the 18 included studies, 9 reported sex-specific data; females exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of UTIs than males, with pooled prevalence estimates of 30.1% (95% CI: 18.9–44.3%; PI: 5.3–76.8) and 14.6% (95% CI: 9.6–21.1%; PI: 3.3–46.5), respectively (p = 0.001). Gender-specific prevalence estimates are illustrated in Table 4.

3.4.5. Age-Specific Prevalence

Of the 18 included studies, 6 reported age-specific data. The overall prevalence of UTIs was 19.6% (95% CI: 14.2–26.4%; PI: 0.3–95.8) in older animals (those aged ≥ 10 years), compared to 26.7% (95% CI: 17.0–39.2%; PI: 2.4–84.3) in younger and adult animals (aged < 10 years). However, this difference was not statistically significant (Table 4).

3.4.6. Diagnostic Threshold Based on Quantitative Bacterial Cultures of Urine

Of the 18 studies included in this review, 11 defined a positive urine culture using a diagnostic cutoff of ≥103 colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL). Two studies employed higher values of ≥104 CFU/mL and ≥105 CFU/mL, respectively, while 5 studies did not report a specific diagnostic cutoff. The pooled prevalence of UTIs was 33.3% (95% CI: 22.9–45.0%; PI: 5.9–79.5) among studies applying the 103 CFU/mL cutoff. Among research that did not specify a diagnostic criterion, the pooled prevalence was 14.5% (95% CI: 9.3–22.1%; PI: 2.9–49.0). Owing to the limited number of studies within certain subgroups, a comparative analysis of prevalence estimates across diagnostic thresholds was not feasible.

3.4.7. Prevalence According to Sampling Methods

Of the 18 included studies, 16 reported sampling method data. The overall prevalence of UTIs was 29.4% (95% CI: 23.6–35.9%; PI: 10.1–60.5) with cystocentesis, compared to 19.2% (95% CI: 13.6–26.7%; PI: 0.2–96.7) with other/unspecified methods (Table 4).

3.5. Meta-Regression Analysis

Univariable meta-regression identified several study-level characteristics that were associated with the prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats (Table 5). Species, sex, and diagnostic threshold demonstrated significant associations. Specifically, dogs had higher odds of UTIs compared with cats (OR = 1.51; 95% CI: 1.27–2.89; p < 0.001), and females were more likely to be affected than males (OR = 2.66; 95% CI: 1.38–5.16; p = 0.004). Studies that employed a diagnostic threshold of 103 CFU/mL (OR = 2.72; 95% CI: 1.43–5.10; p = 0.002) or 104 CFU/mL (OR = 3.35; 95% CI: 1.28–8.67; p = 0.014) reported significantly higher prevalence compared to those without a specified cutoff. In the multivariable model (Table 5), several factors remained significant after adjusting for potential confounders. Dogs continued to exhibit substantially higher odds of UTIs compared with cats (adjusted OR = 3.94; 95% CI: 2.32–6.69; p < 0.001). Similarly, female dogs and cats had significantly higher prevalence compared with males (adjusted OR = 2.64; 95% CI: 1.55–4.48; p < 0.001). Regarding continent, Europe reported a significantly higher prevalence compared with North America (adjusted OR = 6.82; 95% CI: 1.75–26.58; p = 0.006). In terms of clinical cohorts, the prevalence of UTIs among animals with other concurrent illnesses was significantly higher than those with UTIs with LUTDs (adjusted OR = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.10–0.97; p = 0.044). In the adjusted analysis, the diagnostic cutoff of 103 CFU/mL remained significant (adjusted OR = 2.64; 95% CI: 1.39–4.95; p = 0.003), whereas the cutoff of 104 CFU/mL did not. Overall, these findings suggest that species, sex, diagnostic criteria, clinical condition, and geographic region are important determinants of heterogeneity in the reported prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats.

Table 5.

Univariable and multivariable meta-regression analyses of the prevalence of urinary tract infections in dogs and cats with clinical conditions.

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the pooled prevalence estimates were robust across model specifications and study selections. The fixed-effects model yielded 34.9% (95% CI: 34.1–35.9), and the random-effects model gave 26.1% (95% CI: 20.4–32.7). In the leave-one-out analysis, the pooled prevalence ranged from 24.2% (after removing the lowest prevalence [11]) to 28.7% (after removing the highest prevalence [13]), indicating that no single study unduly influenced the overall estimates. When examining the effect of inclusion criteria, the prevalence estimate was 26.1% (95% CI: 20.4–32.7) for studies including only UTIs associated with LUTDs or other illnesses and 26.1% (95% CI: 21.1–31.9) when all available data were included, further supporting the robustness of the findings (Table 6).

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis of the robustness of the estimates for the prevalence of urinary tract infections in dogs and cats with lower urinary tract diseases and other illnesses.

3.7. Prevalence of Pathogenic Bacteria Isolated from the Urine of Dogs and Cats with UTIs

Escherichia coli (median prevalence: 34.7%; range: 11.0–69.0%; eight studies), Proteus spp. (median: 12.6%; range: 2.4–16.6%; eight studies), and Staphylococcus spp. (median: 11.0%; range: 2.0–30.3%; seven studies) were the three most commonly identified bacterial species in canine UTIs. In feline cases, the two most frequently isolated bacteria were E. coli (median: 46.0%; range: 20.8–67.0%; nine studies) and Staphylococcus spp. (median: 10.7%; range: 4.2–33.3%; eight studies), as shown in Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 7.

Proportion of bacterial isolates identified in dogs with UTIs.

Table 8.

Proportion of bacterial isolates identified in cats with UTIs.

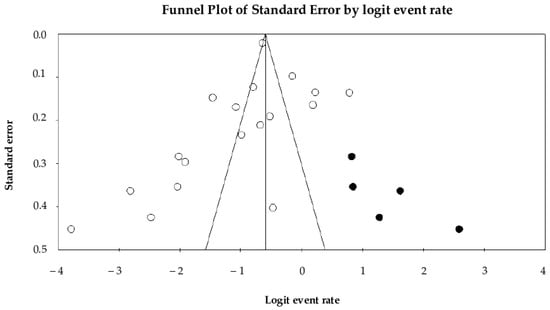

3.8. Evaluation of Publication Bias

Begg’s test (p = 0.01) and Egger’s test (p = 0.35) evaluated potential publication bias. While Begg’s test indicated evidence of bias, Egger’s test did not reach statistical significance. Visual inspection of the funnel plot (Figure 4) reveals slight asymmetry; however, application of Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill method identified five potentially missing studies. After imputing these studies, the estimated pooled prevalence of UTIs changed from 26.1% (95% CI: 20.4–32.7%) to 36.0% (95% CI: 29.0–43.6%).

Figure 4.

Visual inspection of the funnel plot reveals slight asymmetry, indicating potential publication bias. X-axis is the effect size (the logit of the event rate). Y-axis is the precision (standard error). Each included study is represented (white circle). Application of the trim-and-fill method suggested the presence of five potentially missing studies, which were imputed and are shown on the right side of the plot (black circles).

4. Discussion

The pooled prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats associated with LUTDs or other illnesses—including postoperative disk extrusion in dogs (two studies), hyperthyroidism in cats (one study), diabetes mellitus in cats (three studies), chronic kidney disease in cats (one study), and hyperadrenocorticism in dogs (one study)—was estimated at 26.1% using a random-effects meta-analysis. Substantial heterogeneity was observed (Q test, I2 = 95.8%; prediction interval: 8.0–58.9%), indicating considerable variability among the included studies [35]. The included studies differed in populations, disease associations, geographic regions, study periods, diagnostic thresholds, and sampling methods, all of which may have contributed to the high heterogeneity in the pooled estimates. Despite this variability, systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide important insights into disease burden, temporal patterns, and geographic distribution, supporting a broader understanding of UTIs in dogs and cats [36]. Heterogeneity in the pooled prevalence was explored using subgroup meta-analysis as well as univariate and multivariate meta-regression analyses. Seven potential sources of heterogeneity were examined, including study cohorts (UTIs associated with LUTDs vs. other illnesses), continents, species, sex, age, diagnostic thresholds, and sampling methods.

In our study, the estimated prevalence of UTIs associated with LUTDs or other illnesses did not differ significantly in the subgroup analyses (29.9% vs. 20.1%), although heterogeneity remained high. In the multivariate model, after adjustment for additional factors, the trend toward higher UTI prevalence in association with LUTDs versus other illnesses remained inconclusive, with a p-value (0.044) close to the conventional significance threshold.

Regarding geographic regions, the estimated prevalence of UTIs associated with LUTDs or other illnesses did not differ significantly among continents (36.0% in Asia, 29.5% in Europe, and 15.3% in North America). Africa was not included in the subgroup analysis because only a single study was available. High heterogeneity was observed within each continent, reflecting variability both between and within countries. For instance, in Asia, the estimated prevalence of UTIs in cats with LUTDs ranged from 40.8% in one study in Thailand [11] to 11.5% in another [25], with an intermediate estimate of 25.4% reported in Indonesia [26]. In Europe, prevalence estimates for cats with LUTDs were 54.7% in one study from Germany [29], 12.9% in another German study [27], and 7.8% in Switzerland [16]. However, according to multivariate meta-regression, after adjusting for other factors, the pooled prevalence of UTIs was significantly higher in Europe (adjusted OR = 6.82; 95% CI: 1.75–26.58; p = 0.006) compared with North America.

Regarding species, the estimated prevalence of UTIs associated with LUTDs or other illnesses was significantly higher in dogs than in cats (44.6% vs. 18.6%). After adjusting for other factors in multivariate meta-regression analyses, the pooled prevalence in dogs remained higher than that in cats (adjusted OR = 3.94; 95% CI: 2.32–6.69; p < 0.001). This finding aligns with previous reports from Thailand, Spain, and Egypt [11,12,24]. UTIs had the highest prevalence among dogs with lower urinary tract diseases, followed by those with micturition disorders, urolithiasis, prostatic diseases, and traumatic injuries [37,38]. In cats, studies have reported idiopathic cystitis as the most prevalent lower urinary tract disease, followed by urolithiasis and UTIs [16,25,27].

Regarding sex, female dogs and cats had a higher estimated prevalence of UTIs associated with LUTDs or other illnesses than males did (30.1% vs. 14.6%). Multivariate meta-regression analyses confirmed that this difference was significant (adjusted OR = 2.64; 95% CI: 1.55–4.48; p < 0.001), indicating that female dogs and cats are at greater risk. This difference is likely attributable to anatomical factors, as the shorter female urethra facilitates the ascending migration and colonization of uropathogenic bacteria in the urinary bladder [38]. Previous studies have also highlighted the role of fecal–perineal–urethral and urethral–urinary colonization, commensal flora, and other host factors in the pathogenesis of UTIs in both humans and dogs [39,40,41]. Infection typically begins when bacteria with virulence factors colonize the urethral epithelium and ascend to the bladder, especially in the presence of compromised host defenses or alterations in the vaginal microbiome, further explaining the higher prevalence in females [41].

Regarding age, the definition of a senior pet varies; for example, cats are generally considered senior at ≥10 years, whereas the threshold for dogs depends on breed, ranging from 6 to 7 years for large breeds to 11 years or older for small breeds. In this study, we used cutoffs of <10 years and ≥10 years. The estimated prevalence of UTIs associated with LUTDs or other illnesses did not differ significantly between these age groups (p = 0.231). Neither univariate nor multivariate meta-regression analyses indicated significant differences between the two groups. Although advancing age may increase susceptibility to infection—potentially due to immunosenescence, reduced mobility, and comorbid conditions [28,37]—our findings suggest that UTIs associated with LUTDs or other illnesses can affect dogs and cats across all age groups.

Regarding diagnostic thresholds, a quantitative urine culture with a cutoff of ≥103 CFU/mL obtained via cystocentesis or catheterization is considered indicative of significant bacterial growth [42,43]. Subgroup meta-analysis showed that the estimated prevalence of UTIs was significantly higher in studies using a cutoff of 103 CFU/mL compared with those with an unspecified diagnostic threshold (p = 0.004). After adjusting for other factors in multivariate analysis, the pooled prevalence remained higher for this value (adjusted OR = 2.64; 95% CI: 1.39–4.95; p = 0.003), whereas a cutoff of 104 CFU/mL did not reach statistical significance (adjusted OR = 1.48; 95% CI: 0.59–3.67; p = 0.402). This pattern reflects the predominance of studies using the 103 CFU/mL threshold for inclusion (11 studies with 103 CFU/mL vs. 5 studies with unspecified thresholds).

Regarding urine sampling methods, studies using cystocentesis reported a significantly higher estimated prevalence of UTIs compared with those using other methods in subgroup analysis (p = 0.036). However, multivariate analysis showed no significant difference after adjusting for other factors (adjusted OR = 1.55; 95% CI: 0.73–3.29; p = 0.249).

The estimated prevalence of UTIs associated with LUTDs or other illnesses did not change significantly over time, according to both univariate and multivariate meta-regression analyses. These findings suggest a relatively constant prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats with LUTDs and comorbid conditions over the study period. This stability is of public health concern, as dogs and cats can serve as reservoirs for pathogenic and multidrug-resistant bacterial strains.

Single bacterial infections were identified as a primary cause of UTIs in both dogs and cats. E. coli was the most frequently isolated pathogen, exhibiting the highest prevalence among UTI cases, a finding consistent with patterns observed in human clinical studies [44,45]. Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) refers to pathogenic strains of E. coli isolated from the urinary tract. UPEC has undergone adaptive evolution by producing a range of structural (fimbriae, pili, curli, and flagella) and secreted virulence factors, including toxins and iron-acquisition systems. These factors facilitate the bacterium’s ability to colonize, adhere to, and invade the urothelium, as well as to replicate intracellularly within host epithelial cells of the urinary tract [46,47]. The International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases (ISCAID) recommended in 2019 that optimal empirical antimicrobial choices should be guided by pathogens and regional antimicrobial resistance patterns. Amoxicillin (AML) and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (SXT) are recommended by ISCAID as first-tier options for the treatment of sporadic bacterial cystitis. Nitrofurantoin (NIT), fluoroquinolones, and third-generation cephalosporins may be effective when first-tier agents are deemed inappropriate based on culture and susceptibility testing results. Due to concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance and broader public health implications, fluoroquinolones are not recommended as first-line agents, particularly because they are excreted in active form in the urine, which may contribute to the development of resistant bacterial strains [1].

UPEC isolates from dogs exhibited susceptibility to amoxicillin–clavulanate (AMC) in 7.7–59.4% of cases, amoxicillin (AML) in 5–12.5%, cephalexin (CL) in 0–30.8%, enrofloxacin (ENR) in 25–44.4%, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (SXT) in 15–53.8%, and nitrofurantoin (NIT) in 69.2%. Those from cats were susceptible to AMC in 25–80%, AML in 0%, CL in 14.3–34%, ENR in 0–44%, SXT in 20–71.4%, and NIT in 89.3% of cases [11,24,34,48]. Staphylococcus spp. isolates from dogs showed susceptibility to AMC in 20–87.9% of cases, AML in 33.3%, CL in 7–68.6%, ENR in 50–56.4%, and SXT in 20–30.2%. Meanwhile, those from cats were reported to be 100% susceptible to both AMC and ENR [11,16,48]. Proteus spp. isolates from dogs demonstrated susceptibility to AMC in 32–60% of cases, AML in 3%, CL in 15.4%, ENR in 11–36.7%, SXT in 33.3–63%, and NIT in 33.3%. Isolates from cats were susceptible to AMC in 75%, AML and CL in 0%, ENR in 50%, SXT in 50%, and NIT in 25% of cases [11,24]. Across these studies, UPEC, Proteus spp., and Staphylococcus spp. isolates from both dogs and cats exhibited greater susceptibility to AMC than to AML [11,48]. Moreover, in human medicine, a systematic review and meta-analysis reported a high resistance rate of 74.6% to AML among UPEC isolates [49]. In veterinary studies, the three major uropathogens demonstrated greater susceptibility to AMC compared to CL, ENR, and SXT. Similarly, a previous study found that the most frequently isolated uropathogenic species in dogs and cats exhibited susceptibility rates of 93.4% to AMC, 87.6% to SXT, and 76.1% to AML [50]. However, these findings were derived from a small-scale investigation. Overall, UPEC isolates obtained from canine and feline urine samples have demonstrated MDR rates ranging from 11.9% to 55.2% [50,51]. The high resistance rates observed among uropathogens are an increasing concern, particularly given the potential for bidirectional transmission of MDR bacterial strains between companion animals and humans. A large-scale systematic review and meta-analysis examining antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance patterns would provide more robust and generalizable evidence to guide the development of effective, evidence-based antimicrobial stewardship strategies for the management of UTIs in dogs and cats. Data on the patterns of uropathogens causing UTIs in dogs and cats, together with their drug susceptibility profiles, provide valuable insights with potential relevance to the human population. Many bacterial species implicated in veterinary UTIs overlap with those causing infections in humans, and similarities in resistance mechanisms underscore the interconnectedness of antimicrobial resistance across species. Such information is particularly important in the context of rising bacterial resistance and the documented misuse of antibiotics, in both human and veterinary medicine. By identifying resistance trends and highlighting the consequences of inappropriate antibiotic use, these findings reinforce the need for responsible prescribing practices, coordinated surveillance, and the adoption of a One Health approach to mitigate the global threat of antimicrobial resistance.

Publication bias is a well-documented concern in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Several factors contribute to this bias, including the exclusion of studies published in different languages, the inclusion of studies with small sample sizes, and the preferential publication of studies reporting either extremely high or very low prevalence estimates. In particular, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the scope of this meta-analysis was restricted to English-language publications and three electronic databases, which may have resulted in the omission of relevant studies and introduced language and selection bias. Second, considerable heterogeneity and evidence of publication bias were observed. Heterogeneity refers to the variability among studies included in a systematic review and meta-analysis, which may arise from differences in study populations, outcome measures, and methodological designs [52]. In this study, the high level of heterogeneity is likely attributable to such variations. The presence of substantial heterogeneity can limit the interpretability and generalizability of the pooled results, potentially reducing their applicability to a broader population. This limitation justifies the implementation of subgroup analyses to explore sources of variation. Third, certain data could not be included in subgroup analyses due to an insufficient number of studies in some categories, resulting in limited comparative power. Given these limitations, the prevalence estimates presented in this study should be interpreted as relative.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis used a random-effects model to estimate the pooled prevalence of UTIs in dogs and cats associated with LUTDs or other illnesses, which was 26.1%, with high heterogeneity. The distribution of true prevalence ranged from 8.0% to 58.9%. The pooled prevalence was higher in Europe than in North America. UTIs were more prevalent in dogs and in females, although they affected animals across all age groups. The estimated prevalence did not change significantly over time. Single-species bacterial infections, particularly those caused by E. coli, accounted for the majority of cases in both species. These observed patterns in uropathogen type may inform more targeted empirical antimicrobial selection in clinical veterinary practice. Future large-scale systematic reviews and meta-analyses focusing on antimicrobial susceptibility and MDR patterns among uropathogens are warranted. Trends in such pathogens and their drug resistance profiles highlight shared antimicrobial risks across species, emphasizing the urgent need for responsible antibiotic use and a One Health approach to combat rising resistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T., P.S., P.P. and N.F.; methodology, P.T. and P.S.; software, P.S.; validation, P.T. and P.S.; formal analysis, P.T. and P.S.; investigation, P.T.; resources, P.T.; data curation, P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T.; writing—review and editing, N.F.; visualization, P.S., P.P. and N.F.; supervision, N.F.; project administration, P.S., P.P. and N.F.; funding acquisition, P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Weese, J.S.; Blondeau, J.; Boothe, D.; Guardabassi, L.G.; Gumley, N.; Papich, M.; Jessen, L.R.; Lappin, M.; Rankin, S.; Westropp, J.L.; et al. International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases (ISCAID) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of bacterial urinary tract infections in dogs and cats. Vet. J. 2019, 247, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weese, J.S.; Blondeau, J.M.; Boothe, D.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Guardabassi, L.; Hillier, A.; Lloyd, D.H.; Papich, M.G.; Rankin, S.C.; Turnidge, J.D.; et al. Antimicrobial use guidelines for treatment of urinary tract disease in dogs and cats: Antimicrobial guidelines working group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases. Vet. Med. Int. 2011, 2011, 263768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, J.; Snead, E.; Caswell, J.; Feng, C.; Hélie, P.; Lemetayer, J. Pyelonephritis in dogs: Retrospective study of 47 histologically diagnosed cases (2005–2015). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damborg, P.; Pirolo, M.; Schøn Poulsen, L.; Frimodt-Møller, N.; Guardabassi, L. Dogs can be reservoirs of Escherichia coli strains causing urinary tract infection in human household contacts. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faires, M.C.; Tater, K.C.; Weese, S.J. An investigation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in people and pets in the same household with an infected person or infected pet. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2009, 235, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, C.; Belas, A.; Menezes, J.; da Silva, J.M.; Cavaco-Silva, P.; Trigueiro, G.; Gama, L.T.; Pomba, C. Human and companion animal Proteus mirabilis sharing. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 13, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Wintersdorff, C.J.H.; Penders, J.; Van Niekerk, J.M.; Mills, N.D.; Majumder, S.; Van Alphen, L.B.; Savelkoul, P.H.M.; Wolffs, P.F.G. Dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in microbial ecosystems through horizontal gene transfer. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, M.F.; Stephen, J.; Lekshmi, M.; Ojha, M.; Wenzel, N.; Sanford, L.M.; Hernandez, A.J.; Parvathi, A.; Kumar, S.H. Bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terreni, M.; Taccani, M.; Pregnolato, M. New antibiotics for multidrug-resistant bacterial strains: Latest research developments and future perspectives. Molecules 2021, 26, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, P.; Burkhardt, W.A.; Boretti, F.S.; Riond, B.; Reusch, C.E.; Willi, B.; Sieber-Ruckstuhl, N.S. Urinary tract infections in dogs with spontaneous hypercortisolism—Frequency, symptoms and involved pathogens. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd 2020, 162, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amphaiphan, C.; Yano, T.; Som-in, M.; Kungwong, P.; Wongsawan, K.; Pusoonthornthum, R.; Salman, M.D.; Tangtrongsup, S. Antimicrobial drug resistance profile of isolated bacteria in dogs and cats with urologic problems at Chiang Mai University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Thailand (2012–2016). Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernando, E.; Vila, A.; D’Ippolito, P.; Rico, A.J.; Rodon, J.; Roura, X. Prevalence and characterization of urinary tract infection in owned dogs and cats from Spain. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2021, 43, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Roenne, B.; Goldstein, R.E.; Erb, H.N. Urinary tract infections in cats with hyperthyroidism, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2007, 9, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailiff, N.L.; Nelson, R.W.; Feldman, E.C.; Westropp, J.L.; Ling, G.V.; Jang, S.S.; Kass, P.H. Frequency and risk factors for urinary tract infection in cats with diabetes mellitus. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2006, 20, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiffler, K.S.; Stevenson, M.A.M.C.; Sanchez, S.; Barsanti, J.A.; Hofmeister, E.; Budsberg, S.C. Prevalence and characterization of urinary tract infections in dogs with surgically treated type 1 thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion. Vet. Surg. 2006, 35, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, B.; Boretti, F.S.; Kley, S.; Laluha, P.; Muller, C.; Sieber, N.; Unterer, S.; Wenger, M.; Fluckiger, M.; Glaus, T.; et al. Evaluation of clinical signs and causes of lower urinary tract disease in European cats. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2005, 46, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.D.; Troy, G.C.; Dalton, M.N.; Huffman, J.W.; Holtzman, G. Retrospective evaluation of urinary tract infection in 42 dogs with hyperadrenocorticism or diabetes mellitus or both. J. Vet. Int. Med. 1999, 13, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzker, Y.; Blum, D.; Adler, L. Replacing PICO in non-interventional studies. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2023, 28, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukon, P.; Nam, N.H.; Kittipreeya, P.; Sara-in, A.; Wawilai, P.; Inchuai, R.; Weerakhun, S. Global prevalence of Chlamydial infections in birds: A systematic review and meta-Analysis. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 192, 105370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying Heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method. Biometrics 2000, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, H.S.; Ali, M.E.; Abdel Masseih, E.S.; Bakry, N.M. Diagnostic ultrasonography and antimicrobial resistance of different pathogens associated with canine and feline lower urinary tract disorders. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 112, 102216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyarungsri, K.; Tangtrongsup, S.; Thitaram, N.; Lekklar, P.; Kittinuntasilp, A. Prevalence and risk factors of feline lower urinary tract disease in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nururrozi, A.; Yanuartono, Y.; Sivananthan, P.; Indarjulianto, S. Evaluation of lower urinary tract disease in the Yogyakarta cat population, Indonesia. Vet. World 2020, 13, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, E.; Hartmann, K.; Reese, S.; Dorsch, R. Recurrence rate and long-term course of cats with feline lower urinary tract disease. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2020, 22, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, T.M.; Holmslykke, M.; Nordlund, M.; Siersma, V.; Jessen, L.R. Pre-test probability of urinary tract infection in dogs with clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease. Vet. J. 2019, 247, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teichmann-Knorrn, S.; Dorsch, R. Significant bacteriuria in cats: Urinary tract infection and subclinical bacteriuria—A current review. Tierarztl. Prax. Ausg. K Kleintiere Heimtiere 2018, 46, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dorsch, R.; Remer, C.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Hartmann, K. Feline lower urinary tract disease in a German cat population: A retrospective analysis of demographic data, causes and clinical signs. Tierarztl. Prax. Ausg. K Kleintiere Heimtiere 2014, 42, 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Sævik, B.K.; Trangerud, C.; Ottesen, N.; Sørum, H.; Eggertsdóttir, A.V. Causes of lower urinary tract disease in Norwegian cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2011, 13, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olby, N.J.; Mackillop, E.; Moore, S.; Mun, K.R.; Grafinger, M.; Osborne, J.A.; Vaden, S.L. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in dogs after surgery for thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2010, 24, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggertsdóttir, A.V.; Lund, H.S.; Krontveit, R.; Sørum, H. Bacteriuria in cats with feline lower urinary tract disease: A clinical study of 134 cases in Norway. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2007, 9, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, R.; Ebani, V.V.; Cerri, D.; Guidi, G. Survey on bacterial isolates from dogs with urinary tract infections and their in vitro sensitivity. Rev. Med. Vet. 2006, 157, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, T.H.; Migliavaca, C.B.; Stein, C.; Colpani, V.; Falavigna, M.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. Conducting proportional meta-analysis in different types of systematic reviews: A guide for synthesisers of evidence. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; MClinSc, S.M.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendóza-lópez, C.I.; Del-angel-caraza, J.; Quijano-Hernández, I.A.; Barbosa-Mireles, M.A. Analysis of lower urinary tract disease of dogs. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2017, 37, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin, M.A.; Vaden, S.L.; Altier, C.; Stone, E.; Levine, J.F. Persistent urinary tract infections and reinfections in 100 dogs (1989–1999). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2003, 17, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.R.; Kaster, N.; Kuskowski, M.A.; Ling, G.V. Identification of urovirulence traits in Escherichia coli by comparison of urinary and rectal E. coli isolates from dogs with urinary tract infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.N.; Cohn, L.A.; Reinero, C.N.; Rindt, H.; Moore, S.G.; Ericsson, A.C. Characterization of the urinary microbiome in healthy dogs. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, S.; Tsukamoto, T.; Terai, A.; Kurazono, H.; Takeda, Y.; Yoshida, O. Genetic evidence supporting the fecal-perineal-urethral hypothesis in cystitis caused be Escherichia coli. J. Urol. 1997, 157, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartges, J. Urine culture. In Nephrology and Urology of Small Animals; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, T.M.; Jensen, A.B.; Damborg, P.; Bjørnvad, C.R.; Guardabassi, L.; Jessen, L.R. Evaluation of different sampling methods and criteria for diagnosing canine urinary tract infection by quantitative bacterial culture. Vet. J. 2016, 216, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Córdoba, G.; Holm, A.; Hansen, F.; Hammerum, A.M.; Bjerrum, L. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli from patients with suspected urinary tract infection in primary care, Denmark. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlugu, E.M.; Mohamedi, J.A.; Sangeda, R.Z.; Mwambete, K.D. Prevalence of urinary tract infection and antimicrobial resistance patterns of uropathogens with biofilm forming capacity among outpatients in Morogoro, Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlizzi, M.E.; Gribaudo, G.; Maffei, M.E. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) infections: Virulence factors, bladder responses, antibiotic, and non-antibiotic antimicrobial strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zheng, L.; Gong, Z.; Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chi, M. Urinary tract infections caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli: Mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, M.; Kumar, A.; Charaya, G.; Kumar, T. Pathogens isolated from clinical cases of urinary tract infection in dogs and their antibiogram. Vet. World 2018, 11, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Yang, H.; Bi, D.; Khaledi, A.; Qiao, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of antibiotic resistance patterns, and the correlation between biofilm formation with virulence factors in uropathogenic E. coli isolated from urinary tract infections. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 144, 104196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurich, S.; Prenger-Berninghoff, E.; Ewers, C. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of bacterial uropathogens isolated from dogs and cats. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.Y.; Park, H.M. Molecular Characterization of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) strains isolated from companion dogs and cats in Korea. J. Vet. Sci. 2025, 26, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroll, J.B.; Moustgaard, R.; Gøtzsche, P.C. Dealing with substantial heterogeneity in Cochrane reviews. Cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).