Effect of Parasitic Infections on Hematological Profile, Reproductive and Productive Performance in Equines

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology for Literature Search

3. Parasitological Classification of Equine Parasites and Their General Effects

3.1. Protozoan

3.2. Helminths (Nematodes, Trematodes, Cestodes)

3.3. Ectoparasites and Vector-Borne Parasites

4. Effects of Parasitism on Equine Hematological Profile

| Parasite | Parasitic Nature | Disease/Condition | Effects on Host Hematological Profile | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypanosoma evansi | Protozoan hemoparasite | Surra (Trypanosomosis) | Reduced RBC, HCT, and Hb (anemia); lymphocytopenia, monocytopenia, eosinopenia; oxidative stress | [25,47] |

| Theileria annulata & Anaplasma marginale | T. annulata: Hemoprotozoan parasite A. marginale: Obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterial pathogen | Theileriosis & Anaplasmosis (tick-borne) | Donkeys: anemia with decrease ↓ Hb and erythrocyte indices, increase ↑ hematocrit & monocytes; Horses: leukocytosis with altered RBC indices (hemolytic anemia); A. marginale specifically → Horses: ↓ RBCs/monocytes, ↑ WBCs/lymphocytes; Donkeys: ↑ monocytes/hematocrit, ↓ Hb/MCHC | [83,85,91,104] |

| Theileria equi/Babesia caballi/Theileria haneyi | Intraerythrocytic protozoan | Equine Piroplasmosis (EP) | Leukocytosis, mild anemia, hyperbilirubinemia; chronic carriers show oxidative stress and hepatorenal dysfunction | [81,82,105,106] |

| Theileria annulata & Anaplasma marginale | Hemoprotozoan parasite (T. annulata); Obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterium (A. marginale) | Theileriosis & Anaplasmosis (tick-borne) | Donkeys: anemia with ↓ Hb and erythrocyte indices, ↑ hematocrit & monocytes; Horses: leukocytosis with altered RBC indices (hemolytic anemia); A. marginale specifically → Horses: ↓ RBCs/monocytes, ↑ WBCs/lymphocytes; Donkeys: ↑ monocytes/hematocrit, ↓ Hb/MCHC | [83,85,91,104] |

| Theileria annulata | Tropical Theileriosis | Protozoan (Apicomplexa) | Horses: increased lymphocytes, MCH; decreased RBCs, MCV Donkeys: increased lymphocytes, monocytes, RBCs; decreased hemoglobin, MCV, MCH (anemia) | [83,104] |

| Besnoitia spp. | Besnoitiosis | Protozoan | Mild anemia; leukocytosis; eosinophilia; lymphocytosis; hypoalbuminemia; increased alkaline phosphatase | [93] |

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum | Obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterium | Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis (EGA) | Thrombocytopenia; leukopenia; anemia; mediated hemolysis | [83,84,85] |

| Strongylus spp. | nematodes; | Equine strongylosis (Strongylosis) | Anemia (reduced hemoglobin, PCV, RBCs); impaired erythropoiesis due to nutrient competition | [99,100,101] |

| Strongyles, Eimeria, Moniezia | Gastrointestinal parasites (nematodes and protozoa) | Parasitic enteritis in goats | Reduced hemoglobin, packed cell volume (PCV), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) | [103] |

| Haemonchus contortus, Strongyloides spp., Moniezia spp., Fasciola hepatica | Gastrointestinal nematodes and trematodes | Parasitic infections in small ruminants | Anemia, metabolic imbalance, and disrupted hematological and biochemical profiles | [102] |

| Fasciola hepatica (Liver Fluke) | Zoonotic trematode | Equine (Fascioliasis) | Anemia: Decreased RBC count and hemoglobin levels. - Immunosuppression: Reduced leukocyte and lymphocyte counts. | [107] |

| Strongyles, Eimeria, Moniezia | Gastrointestinal parasites (nematodes and protozoa) | Parasitic enteritis in goats | Reduced hemoglobin, packed cell volume (PCV), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) | [103] |

5. Consequences of Parasitic Infections on Reproductive Parameters

5.1. Effects of Parasitism on Equine Semen Quality

5.2. Effects of Parasitism on Equine Pregnancy

| Parasite | Parasitic Nature | Disease | Effects of Parasitism on Equine Semen/Fertility | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypanosoma congolense | Hemoparasite (blood protozoan | Trypanosomosis | ↓ Testosterone, ↑ Prolactin, anemia, oxidative stress → impaired spermatogenesis | [111] |

| Neospora hughesi | Protozoan | Equine abortion | Transplacental infection causes fetal death; it can reduce reproductive efficiency and fertility in mares | [135] |

| Trypanosoma equiperdum | Extracellular hemoparasite | (Equine) Dourine | Orchitis Sperm abnormalities Reduced motility | [109,110] |

| Trypanosoma vivax, | Hemoparasite (extracellular) | Trypanosomiasis | Reduced fertility, abortions, agalactia, impaired reproductive activity in males and females | [113,114,115] |

| Habronema spp./ Draschia megastoma | Nematode larval stage | Penile/preputial granulomas | Pain, mating difficulty, penile prolapse infertility risk | [118,119] |

| Toxoplasma gondii | Obligate intracellular protozoan | Donkey/Toxoplasmosis, reproductive dysfunction | abortion, | [140,141] |

| Neospora caninum | Protozoan parasite | Horses/Neosporosis | Abortion, fetal death, reproductive loss | [142] |

| Encephalitozoon spp. | Microsporidian | Placentitis, Abortion | Causes placentitis and subsequent abortion | [122,126,127,143] |

| Encephalitozoon cuniculi | Microsporidian | Necrotising Placentitis, | Reported in a case leading to necrotising placentitis and abortion at the final stage of gestation | [126] |

| Babesia caballi | Protozoan parasite, tick-borne (Rhipicephalus spp., Amblyomma spp., Dermacentor spp.) | Equine Piroplasmosis | Transplacental infection, abortion, or birth of infected foals (may show disease signs) | [129,130] |

| Theileria equi | Equine Piroplasmosis | Major cause of equine abortions in endemic areas; transplacental | [129,130,138] | |

| Neospora hughesi | Protozoan, an intracellular parasite | Neosporosis | Causes equine abortion via transplacental tachyzoite transmission; induces necrotizing pneumonia, myocarditis, hepatitis, and placentitis, resulting in fetal death | [135] |

| Acanthamoeba hatchetti | Free-living amoeba | Placentitis | Can compromise pregnancy | [137] |

6. Parasitic Consequences on Productivity (Milk & Meat)

| Parasite | Parasitic Nature | Disease | Effects of Parasitism on Milk and Meat Quality | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongyles (e.g., Cyathostomum spp., Strongylus spp.) | Gastrointestinal nematodes | Strongylosis causes anemia, weight loss, and poor body condition | Indirectly reduces milk yield and alters composition by impairing nutritional status and metabolic balance. | [148] |

| Sarcocystis bertrami & Sarcocystis fayeri | Protozoan parasites forming sarcocysts in muscle tissue | Sarcocystosis | Cause muscle inflammation and dystrophic changes, reducing meat quality and potentially affecting animal productivity | [24] |

| Cyathostomins spp. | Gastrointestinal nematodes | Larval Cyathostominosis | Causes severe intestinal damage, weight loss, and emaciation, leading to poor body condition and reduced meat quality. | [39,40] |

| Strongylus spp. (Strongyles) | Nematode intestinal roundworm) | Strongylosis | Causes unthriftiness, anemia, colic, diarrhea, poor weight gain, the poor weight gain and body condition imply reduced meat quality and lower overall productivity. | [61] |

| Cyathostomins | Gastrointestinal nematodes (small Strongyles) | Cyathostomiasis | High burdens of eggs per gram (EPG >1000) reduce milk lactose and quantity, increase milk urea and pH, leading to compromised milk production at the farm level | [23,147] |

| Toxoplasma gondii | Protozoan parasite (zoonotic) | Toxoplasmosis | Contamination of milk and meat; zoonotic risk; potential public health hazard | [149,150] |

| Theileria equi | Tick-borne protozoan | Equine piroplasmosis | Causes acute infection leading to abortion in mares; economic losses in equine breeding | [106,129,132,133] |

| Fasciola hepatica | Trematode | Fasciolosis | Reduced milk yield, lower butterfat and protein content; economic losses due to liver condemnation | [151,152,153,157] |

| Trypanosoma vivax | Protozoan | Trypanosomiasis | Reduced milk and meat production, weight loss, mortality; significant herd productivity losses | [159,160] |

| Besnoitia besnoiti | Protozoan | Bovine besnoitiosis | Reduced milk production, prolonged recovery, weight loss; economic losses | [161,162,163] |

| Sarcocystis bertrami, S. fayeri | Protozoan | Sarcocystosis | Muscle cysts cause reduced nutritional value, altered texture, and zoonotic hazard | [24,165] |

| Fasciola spp. (in cattle) | Trematode | Fasciolosis | Liver condemnation, reduced meat yield; economic losses | [167] |

| Taenia saginata | Cestode | Cysticercosis | Visible cysts in muscle; meat condemnation; economic loss | [168] |

| Sarcocystis spp. (in sheep) | Protozoan | Sarcocystosis | Changes in flavor profile: increased bitterness/sourness, reduced desirable aroma; biochemical changes in muscle | [169,170] |

7. Zoonotic Relevance

| Parasite | Host Animal | Disease | Zoonotic Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarcocystis spp. | Equines (Horses) | Sarcocystosis | Consumption of raw or undercooked horse meat can cause food poisoning in humans; it demonstrates zoonotic potential | [177] |

| Toxoplasma gondii | Donkeys | Toxoplasmosis | Detected in the blood and milk of donkeys; consumption of raw milk or meat may transmit infection to humans. | [149,150] |

| Toxoplasma gondii | Equine (Horses) | Toxoplasmosis | Detected in horses; consumption of raw or undercooked horse meat is linked to human infection cases | [145,190,191,192,193,194] |

| Trichinella spp. | Horse | Trichinellosis | Often subclinical in horses, but reduces meat quality due to larval encystment; causes human trichinellosis when raw or undercooked horse meat is consumed; several large outbreaks in Europe confirm strong zoonotic potential | [158] |

| Sarcocystis spp. | Horse | Sarcocystosis | Consumption of raw or undercooked horse meat can cause food poisoning in humans; it demonstrates zoonotic potential | [177] |

| Sarcocystis spp. & Toxoplasma gondii | Equine | Toxoplasmosis, Sarcocystosis | Infectious equid meat with the highest prevalence in donkeys; humans may acquire infection through the consumption of contaminated meat, highlighting zoonotic risk | [195] |

| Fasciola hepatica | Equines (horses, donkeys, mules) | Equine fasciolosis (liver fluke infection) | Recognized zoonosis (humans infected via metacercariae) | [107,196] |

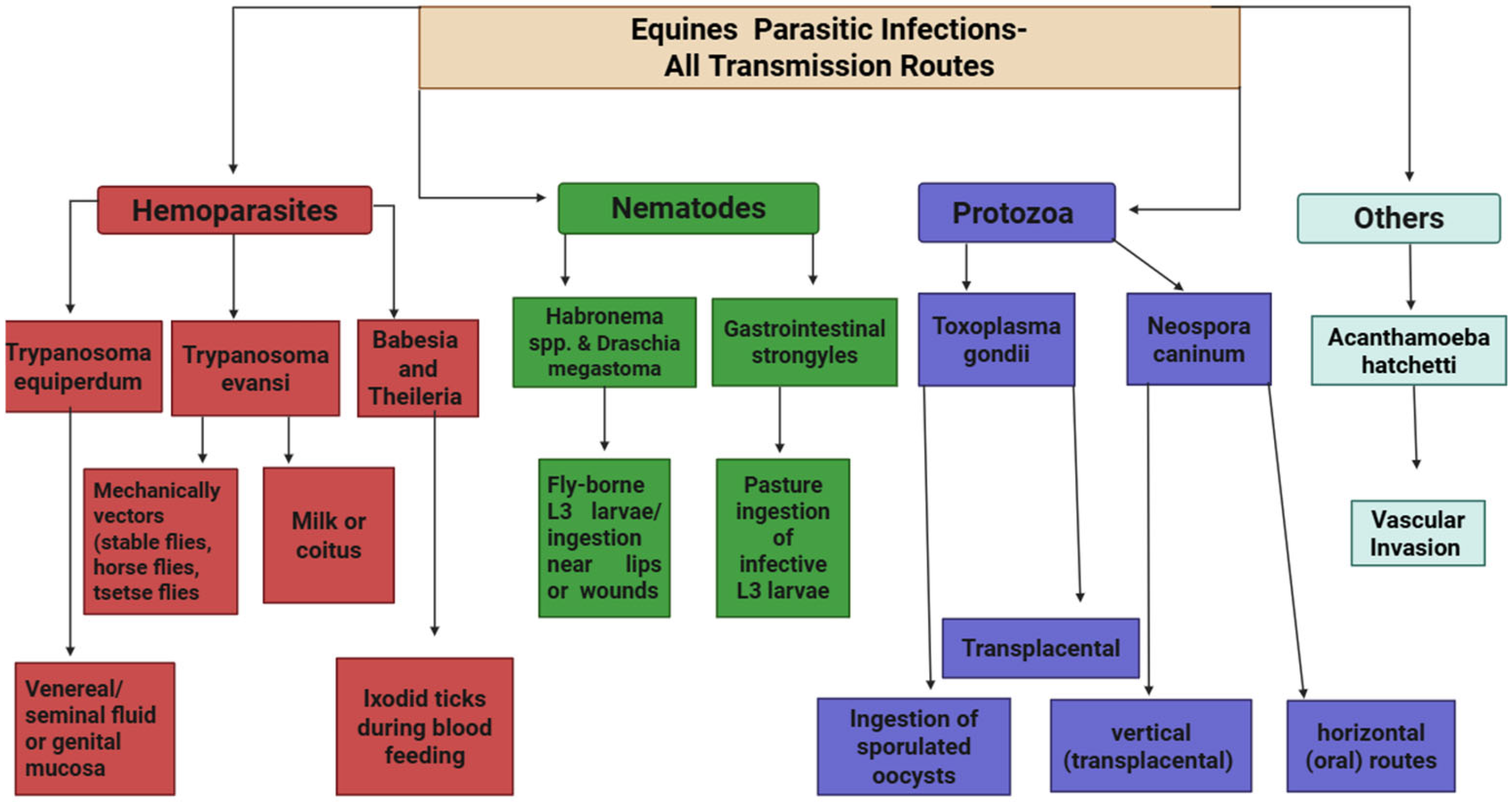

8. Transmission of Parasitic Infections in Equines

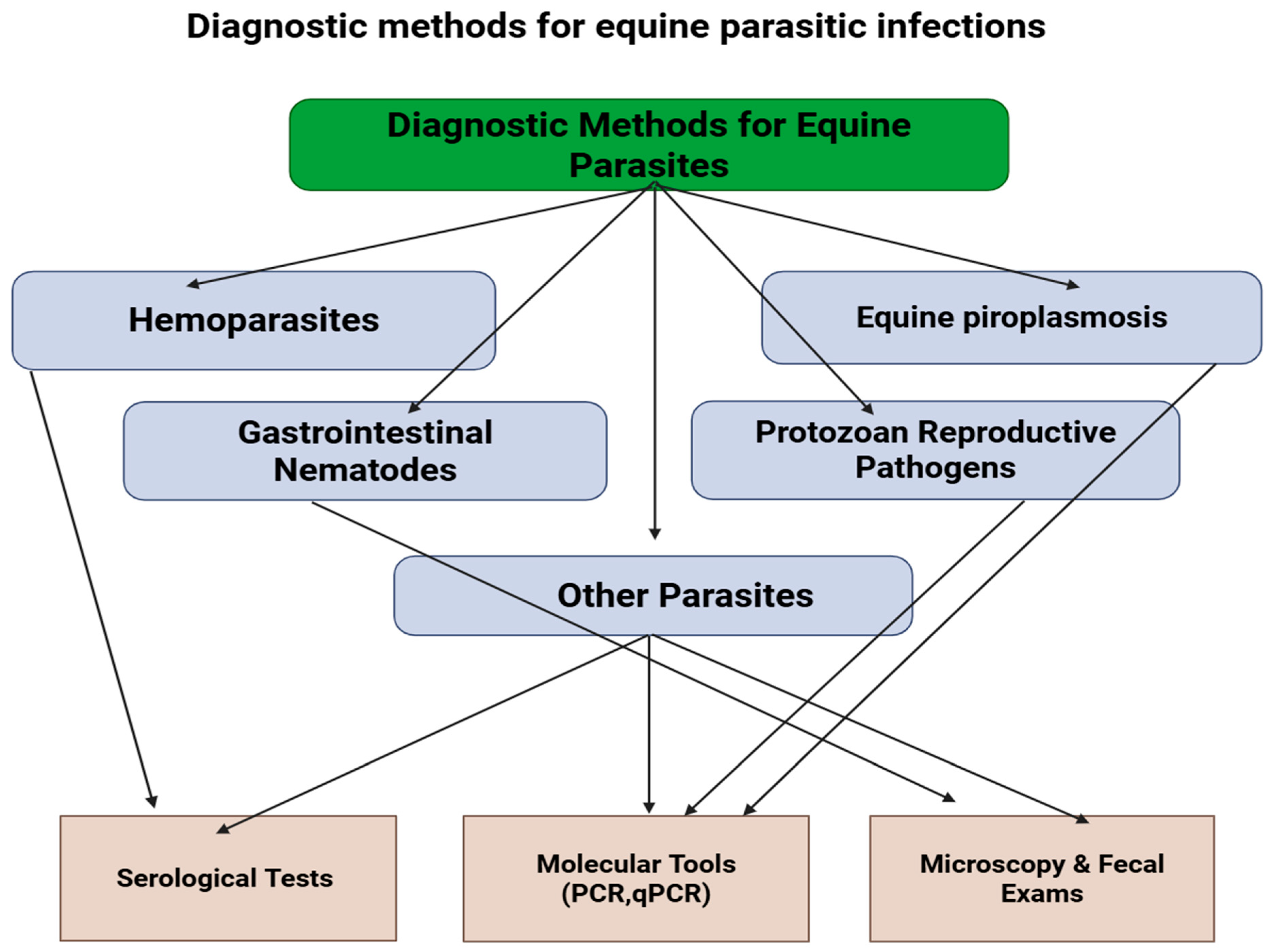

9. Diagnosis of Parasitic Infections in Equines

10. Control and Treatment of Parasitic Infections in Equines

| Parasite/Disease | Drug & Dose | Route | Frequency/Protocol | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypanosoma evansi (Surra) in horses & mules | Diminazene aceturate 3.5 mg/kg body weight | Intramuscular (IM) | On Day 0 and again on Day 41 | [251] |

| Trypanosoma equiperdum (Dourine) in horses, acute & chronic infection | Melarsomine (Cymelarsan) 0.25 mg/kg and 0.5 mg/kg | Intramuscular (IM) | Single dose; also tested in repeated or comparative regimens | [224] |

| Trypanosoma equiperdum (Cymelarsan) in neurologic (CSF-positive) dourine | Melarsomine (Cymelarsan) 0.5 mg/kg daily for 7 days | route IM (used in study) | Repeated daily administration over 7 days | [252] |

| Theileria equi (Equine piroplasmosis) | Imidocarb dipropionate 4 Dose (mg/kg) | Intramuscular (IM), subcutaneous (SC) | Four injections 72 h apart | [253] |

| Babesia caballi (Equine piroplasmosis | Imidocarb dipropionate 2.2 mg/kg | IM/SC | Two injections 48 h apart | [254] |

| Habronema/Draschia spp. larvae | Ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg | Historically IM in study; commonly oral in practice | Single dose; lesions often need local care +/− anti-inflammatories | [255] |

| Strongyles (roundworms) and Tapeworms (Anoplocephala perfoliata) | Ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg) + Praziquantel (1.5 mg/kg) | Oral (paste formulation, Equimax®) | Single treatment suppressed strongyle FECs to zero for 10 weeks | [256] |

| Cyathostomins (small Strongyles, encysted larvae and adults) | Moxidectin 0.4 mg/kg | Oral (PO) | Single dose; reduced FEC by 99.9% at 14 days; | [257] |

| Cyathostomins (small Strongyles, encysted larvae and adults) | Fenbendazole 10 mg/kg | Oral (PO) | Once daily × 5 consecutive days; only 41.9% FEC reduction at 14 days; | [257] |

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, M.Z.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Liang, H.; Wei, L.; Huang, B.; Kou, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chai, W. A review of genetic resources and trends of omics applications in donkey research: Focus on China. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1366128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggs, H.C.; Ainslie, A.; Bennett, R.M. Donkey ownership provides a range of income benefits to the livelihoods of rural households in Northern Ghana. Animals 2021, 11, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, M.; Gillett, J. Equine athletes and interspecies sport. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2012, 47, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wei, L.; Chen, X.; Zhu, H.; Wei, J.; Zhu, M.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z. Nutritional Composition and Biological Activities of Donkey Milk: A Narrative Review. Foods 2025, 14, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.Z.; Chen, W.; Li, M.; Ren, W.; Huang, B.; Kou, X.; Ullah, Q.; Wei, L.; Wang, T.; Khan, A. Is there sufficient evidence to support the health benefits of including donkey milk in the diet? Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1404998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, L.; Du, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, W.; Man, L.; Zhu, M.; Liu, G.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C. Characterization and discrimination of donkey milk lipids and volatiles across lactation stages. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Q.; Liu, G.; Wang, C. Effects of donkey milk on oxidative stress and inflammatory response. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e13935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Altomonte, I.; Tricò, D.; Lapenta, R.; Salari, F. Current knowledge on functionality and potential therapeutic uses of donkey milk. Animals 2021, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souroullas, K.; Aspri, M.; Papademas, P. Donkey milk as a supplement in infant formula: Benefits and technological challenges. Food Res. Int. 2018, 109, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroua, M.; Fehri, N.E.; Ben Said, S.; Quattrone, A.; Agradi, S.; Brecchia, G.; Balzaretti, C.M.; Mahouachi, M.; Castrica, M. The use of horse and donkey meat to enhance the quality of the traditional meat product (kaddid): Analysis of physico-chemical traits. Foods 2024, 13, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, L.; Du, X.; Ren, W.; Man, L.; Chai, W.; Zhu, M.; Liu, G.; Wang, C. Characterization of lipids and volatile compounds in boiled donkey meat by lipidomics and volatilomics. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 3445–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Qu, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Ma, Q.; Khan, M.Z.; Zhu, M.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Chai, W. Data-independent acquisition method for in-depth proteomic screening of donkey meat. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z.M.; Manyelo, T.G.; Nemukondeni, N.; Sebola, A.N.; Selaledi, L.; Mabelebele, M. The possibility of including donkey meat and Milk in the food chain: A southern African scenario. Animals 2022, 12, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Q. Comparative transcriptome and proteome analyses of the longissimus dorsi muscle for explaining the difference between donkey meat and other meats. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 3085–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Liang, H.; Zahoor Khan, M.; Ren, W.; Huang, B.; Chen, Y.; Xing, S.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, C. Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis unveils the interplay of mRNA and LncRNA expression in shaping collagen organization and skin development in Dezhou donkeys. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1335591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, W.; Peng, Y.; Khan, M.Z.; Liang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Kou, X.; Wang, L. Elucidating the role of transcriptomic networks and DNA methylation in collagen deposition of Dezhou donkey skin. Animals 2024, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, J.; Ullah, A.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C. Morphometric and Histological Characterization of Chestnuts in Dezhou Donkeys and Associations with Phenotypic Traits. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.K. Sustainable equine parasite control: Perspectives and research needs. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 185, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrnenopoulou, P.; Boufis, P.T.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Papadopoulos, E. Interactions between parasitic infections and reproductive efficiency in horses. Parasitologia 2021, 1, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavazza, A.; Delgadillo, A.; Gugliucci, B.; Pasquini, A.; Lubas, G. Haematological alterations observed in equine routine complete blood counts. A retrospective investigation. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2002, 11, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krecek, R.C.; Waller, P.J. Towards the implementation of the “basket of options” approach to helminth parasite control of livestock: Emphasis on the tropics/subtropics. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 139, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, W.J. Improving the welfare of working equine animals in developing countries. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 100, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrucci, S.; Salari, F.; Maestrini, M.; Altomonte, I.; Guardone, L.; Nardoni, S.; Molento, M.B.; Martini, M. Cyathostomin fecal egg count and milk quality in dairy donkeys. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Veterinária 2021, 30, e028220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermukhametov, Z.; Suleimanova, K.; Tomaruk, O.; Baimenov, B.; Shevchenko, P.; Batyrbekov, A.; Mikniene, Z.; Onur Girişgin, A.; Rychshanova, R. Equine sarcocystosis in the northern region of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Animals 2024, 14, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoraba, M.; Shoulah, S.A.; Arnaout, F.; Selim, A. Equine trypanosomiasis: Molecular detection, hematological, and oxidative stress profiling. Vet. Med. Int. 2024, 2024, 6550276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.S.; El-Ezz, N.T.A.; Abdel-Shafy, S.; Nassar, S.A.; El Namaky, A.H.; Khalil, W.K.; Knowles, D.; Kappmeyer, L.; Silva, M.G.; Suarez, C.E. Assessment of Theileria equi and Babesia caballi infections in equine populations in Egypt by molecular, serological and hematological approaches. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, L.; Kappmeyer, L.; Mealey, R.; Knowles, D. Review of equine piroplasmosis. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2013, 27, 1334–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ijaz, M.; Farooqi, S.; Durrani, A.; Rashid, M.; Ghaffar, A.; Ali, A.; Rehman, A.; Aslam, S.; Khan, I. Molecular characterisation of Theileria equi and risk factors associated with the occurrence of theileriosis in horses of Punjab (Pakistan). Equine Vet. Educ. 2021, 33, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, G.; Zanghi, A.; Quartuccio, M.; Cristarella, S.; Giuseppe, M.; Catone, G. Equine testicular lesions related to invasion by nematodes. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2009, 29, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M.; Holzmuller, P.; Lai, D.-H.; Dargantes, A.; Lun, Z.-R.; Jittaplapong, S. Trypanosoma evansi and surra: A review and perspectives on origin, history, distribution, taxonomy, morphology, hosts, and pathogenic effects. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 194176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiei, K.; Ahmadi, M.; Nazifi, S. Equine trypanosomiasis (T. evansi): A case report associated with abortion. Iran Vet. J. 1998, 1, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Perri, A.; Mejía, M.; Licoff, N.; Lazaro, L.; Miglierina, M.; Ornstein, A.; Becu-Villalobos, D.; Lacau-Mengido, I. Gastrointestinal parasites presence during the peripartum decreases total milk production in grazing dairy Holstein cows. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 178, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.M.; Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasmosis: A history of clinical observations. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaapan, R.M. The common zoonotic protozoal diseases causing abortion. J. Parasit. Dis. 2016, 40, 1116–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazmand, A.; Bahari, A.; Papi, S.; Otranto, D. Parasitic diseases of equids in Iran (1931–2020): A literature review. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alali, F.; Jawad, M.; Al-Obaidi, Q.T. A review of endo and ecto parasites of equids in Iraq. J. Adv. VetBio Sci. Tech. 2022, 7, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinemeyer, C.; Nielsen, M. Control of helminth parasites in juvenile horses. Equine Vet. Educ. 2017, 29, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.C.; Biddle, A.S. The use of molecular profiling to track equine reinfection rates of cyathostomin species following anthelmintic administration. Animals 2021, 11, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molento, M.B. Parasite resistance on helminths of equids and management proposal’s. Ciência Rural 2005, 35, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oryan, A.; Farjani Kish, G.; Rajabloo, M. Larval cyathostominosis in a working donkey. J. Parasit. Dis. 2015, 39, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Health, C.f.E. Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis (EPM). University of California, Davis. Available online: https://ceh.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/health-topics/equine-protozoal-myeloencephalitis-epm (accessed on 3 October 2025).[Green Version]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Equine Piroplasmosis (EP). Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/equine/piroplasmosis (accessed on 3 October 2025).[Green Version]

- Aleman, M.; Shapiro, K.; Sisó, S.; Williams, D.C.; Rejmanek, D.; Aguilar, B.; Conrad, P.A. Sarcocystis fayeri in skeletal muscle of horses with neuromuscular disease. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2016, 26, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allsopp, M.; Lewis, B.; Penzhorn, B.L. Molecular evidence for transplacental transmission of Theileria equi from carrier mares to their apparently healthy foals. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 148, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.N.; Carstens, A.; Meintjes, R.; Oosthuizen, M.C.; Van Blerk, C.; Scheepers, F. Faculty Day, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, 6 September 2012: Research Overview. 2012. Available online: https://repository.up.ac.za/items/fd1386de-4431-4d40-9d7e-41def79efc40 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Angwin, C.-J.; de Assis Rocha, I.; Reed, S.M.; Morrow, J.K.; Graves, A.; Howe, D.K. Analysis of IgG responses to Sarcocystis neurona in horses with equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM) suggests a Th1-biased immune response. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2025, 289, 111009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreira, D.R.; Jansen, A.M.; Abreu, U.G.; Macedo, G.C.; Silva, A.R.; Mazur, C.; Andrade, G.B.; Herrera, H.M. Health and epidemiological approaches of Trypanosoma evansi and equine infectious anemia virus in naturally infected horses at southern Pantanal. Acta Trop. 2016, 163, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroplasmosis, E. Equine piroplasmosis (EP) is a tick-borne protozoal disease ofhorses, mules, donkeys, and zebras that is character-ized by acute hemolytic anemia. 1-6 The etiologic agents are two hemoprotozoan parasites, Babesia equi (Laveran, 1901) 7 and Babesia caballi (Nutall and Strickland, 1910), 8. Equine Infect. Dis. 2007, 465. [Google Scholar]

- Tolera, T. Study on Tick-Borne Pathogens and Tick-Borne Diseases Using Molecular Tools with Emphasis on Anaplasma spp. and Ehrlichia spp. In Ticks and Domestic Ruminants in Ethiopia. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ola-Fadunsin, S.; Daodu, O.; Hussain, K.; Ganiyu, I.; Rabiu, M.; Sanda, I.; Adah, A.; Adah, A.; Aiyedun, J. Gastrointestinal parasites of horses (Equus caballus Linnaeus, 1758) and risk factors associated with equine coccidiosis in Kwara and Niger States, Nigeria. Sokoto J. Vet. Sci. 2019, 17, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dubey, J.P.; Bauer, C. A review of Eimeria infections in horses and other equids. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 256, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangoura, B.; Daugschies, A. Eimeria. In Parasitic Protozoa of Farm Animals and Pets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 55–101. [Google Scholar]

- Khamesipour, F.; Taktaz-Hafshejani, T.; Tebit, K.E.; Razavi, S.M.; Hosseini, S.R. Prevalence of endo-and ecto-parasites of equines in Iran: A systematic review. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 7, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, K.; Bashtar, A.R.; Al Quraishy, S.; Adel, S. Description of two equine nematodes, Parascaris equorum Goeze 1782 and Habronema microstoma Schneider 1866 from the domestic horse Equus ferus caballus (Famisly: Equidae) in Egypt. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 4299–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soykan, E.; Öge, H. The prevalence of liver trematodes in equines in different cities of Turkey. Türkiye Parazitolojii Derg. 2012, 36, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocombe, J. Prevalence and treatment of tapeworms in horses. Can. Vet. J. 1979, 20, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Almatar, R. Equine Fasciolosis: A Literature Review. Diploma Thesis, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, A.; Sekiya, M.; Garcia-Campos, A.; Paz-Silva, A.; Howell, A.; Williams, D.; Mulcahy, G. Horses are susceptible to natural, but resistant to experimental, infection with the liver fluke, Fasciola hepatica. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 281, 109094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornok, S.; Genchi, C.; Bazzocchi, C.; Fok, E.; Farkas, R. Prevalence of Setaria equine microfilaraemia in horses in Hungary. Vet. Rec. 2007, 161, 814–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Hwang, H.; Ro, Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, K.; Choi, E.; Bae, Y.; So, B.; Lee, I. Setaria digitata was the main cause of equine neurological ataxia in Korea: 50 cases (2015–2016). J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disassa, H.; Alebachew, A.; Kebede, G. Prevalence of strongyle infection in horses and donkeys in and around Dangila town, northwest Ethiopia. Acta Parasitol. Glob. 2015, 6, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.K.; Facison, C.; Scare, J.A.; Martin, A.N.; Gravatte, H.S.; Steuer, A.E. Diagnosing Strongylus vulgaris in pooled fecal samples. Vet. Parasitol. 2021, 296, 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, W.; Teshome, D.; Abiye, A. Study on the Prevalance of Gastrointestinal Helminthes Infection in Equines in and around Kombolcha. J. Vet. Sci. Technol. 2016, 7, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribb, N.; Cote, N.; Boure, L.; Peregrine, A. Acute small intestinal obstruction associated with Parascaris equorum infection in young horses: 25 cases (1985–2004). N. Z. Vet. J. 2006, 54, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatz, A.; Segev, G.; Steinman, A.; Berlin, D.; Milgram, J.; Kelmer, G. Surgical treatment for acute small intestinal obstruction caused by Parascaris equorum infection in 15 horses (2002–2011). Equine Vet. J. 2012, 44, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. Equine tapeworm infections: Disease, diagnosis and control. Equine Vet. Educ. 2016, 28, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, K.; Ali, A.; Villagra, C.; Siddiqui, S.; Alouffi, A.S.; Iqbal, A. A cross-sectional study of hard ticks (acari: Ixodidae) on horse farms to assess the risk factors associated with tick-borne diseases. Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onmaz, A.; Beutel, R.; Schneeberg, K.; Pavaloiu, A.; Komarek, A.; Van Den Hoven, R. Vectors and vector-borne diseases of horses. Vet. Res. Commun. 2013, 37, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, G.E.; Sherlock, K.; Hesson, J.C.; Blagrove, M.S.; Lycett, G.J.; Archer, D.; Solomon, T.; Baylis, M. Laboratory transmission potential of British mosquitoes for equine arboviruses. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siriyasatien, P.; Intayot, P.; Sawaswong, V.; Preativatanyou, K.; Wacharapluesadee, S.; Boonserm, R.; Sor-Suwan, S.; Ayuyoe, P.; Cantos-Barreda, A.; Phumee, A. Description of potential vectors of zoonotic filarial nematodes, Brugia pahangi, Setaria digitata, and Setaria labiatopapillosa in Thai mosquitoes. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.; Ro, Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.; Choi, E.-J.; Bae, Y.-C.; So, B.; Kwon, D.; Kim, H. Epidemiological investigation of equine hindlimb ataxia with Setaria digitata in South Korea. J. Vet. Sci. 2022, 23, e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldacchino, F.; Desquesnes, M.; Mihok, S.; Foil, L.D.; Duvallet, G.; Jittapalapong, S. Tabanids: Neglected subjects of research, but important vectors of disease agents! Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 28, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetkarl, T.; Fungwithaya, P.; Udompornprasith, S.; Amendt, J.; Sontigun, N. Preliminary study on prevalence of hemoprotozoan parasites harbored by Stomoxys (Diptera: Muscidae) and tabanid flies (Diptera: Tabanidae) in horse farms in Nakhon Si Thammarat province, Southern Thailand. Vet. World 2023, 16, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khang, L.H.; Peng, T.L.; Mohamad, M.A.; Rajdi, N.Z.I.M.; Goni, M.D. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding ticks and tick borne diseases among horse keepers in Malaysia. Discov. Public Health 2025, 22, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otranto, D.; Milillo, P.; Capelli, G.; Colwell, D.D. Species composition of Gasterophilus spp. (Diptera, Oestridae) causing equine gastric myiasis in southern Italy: Parasite biodiversity and risks for extinction. Vet. Parasitol. 2005, 133, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studzińska, M.B.; Wojcieszak, K. Gasterophilus sp. botfly larvae in horses from the south-eastern part of Poland. Bull. Vet. Inst. Pulawy 2009, 53, 651–655. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, P.E. External Parasites of Horses; University of Florida, IFAS Extension: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2010; Available online: http://extadmin.ifas.ufl.edu/media/extadminifasufledu/cflag/image/docs/fl-equine-institute/2010/Kaufman.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Basit, A.; Ali, M.; Hussain, G.; Irfan, S.; Saqib, M.; Iftikhar, A.; Mustafa, I.; Mukhtar, I.; Anwar, H. Effect of equine piroplasmosis on hematological and oxidative stress biomarkers in relation to different seasons in District Sargodha, Pakistan. Pak. Vet. J. 2020, 40, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Duaso, J.; Perez-Ecija, A.; Martínez, E.; Navarro, A.; De Las Heras, A.; Mendoza, F.J. Assessment of common hematologic parameters and novel hematologic ratios for predicting piroplasmosis infection in horses. Animals 2025, 15, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, M.A.; Beveridge, I.; Abbas, G.; Beasley, A.; Bauquier, J.; Wilkes, E.; Jacobson, C.; Hughes, K.J.; El-Hage, C.; O’Handley, R. Systematic review of gastrointestinal nematodes of horses from Australia. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camino, E.; Dorrego, A.; Carvajal, K.A.; Buendia-Andres, A.; de Juan, L.; Dominguez, L.; Cruz-Lopez, F. Serological, molecular and hematological diagnosis in horses with clinical suspicion of equine piroplasmosis: Pooling strengths. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 275, 108928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, D.P.; Kappmeyer, L.S.; Haney, D.; Herndon, D.R.; Fry, L.M.; Munro, J.B.; Sears, K.; Ueti, M.W.; Wise, L.N.; Silva, M. Discovery of a novel species, Theileria haneyi n. sp., infective to equids, highlights exceptional genomic diversity within the genus Theileria: Implications for apicomplexan parasite surveillance. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018, 48, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Parveen, A.; Ashraf, S.; Hussain, M.; Aktas, M.; Ozubek, S.; Shaikh, R.S.; Iqbal, F. First report regarding the simultaneous molecular detection of Anaplasma marginale and Theileria annulata in equine blood samples collected from Southern Punjab in Pakistan. Acta Parasitol. 2020, 65, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, A.M.; Mitrea, I.L.; Ionita, M. Equine granulocytic anaplasmosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis on clinico-pathological findings, diagnosis, and therapeutic management. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeet, M.; Adeleye, A.; Adebayo, O.; Akande, F. Haematology and serum biochemical alteration in stress induced equine theileriosis. A case report. Sci. World J. 2009, 4, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulino, P.G.; Almosny, N.; Oliveira, R.; Viscardi, V.; Müller, A.; Guimarães, A.; Baldani, C.; da Silva, C.; Peckle, M.; Massard, C. Detection of Neorickettsia risticii, the agent of Potomac horse fever, in horses from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7208. [Google Scholar]

- Siska, W.D.; Tuttle, R.E.; Messick, J.B.; Bisby, T.M.; Toth, B.; Kritchevsky, J.E. Clinicopathologic characterization of six cases of Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis in a nonendemic area (2008–2011). J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2013, 33, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munderloh, U.G.; Lynch, M.J.; Herron, M.J.; Palmer, A.T.; Kurtti, T.J.; Nelson, R.D.; Goodman, J.L. Infection of endothelial cells with Anaplasma marginale and A. phagocytophilum. Vet. Microbiol. 2004, 101, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.R.; Zimmerman, K.; Dascanio, J.J.; Pleasant, R.S.; Witonsky, S.G. Equine granulocytic anaplasmosis: A case report and review. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2009, 29, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, L.A. Ehrlichiosis and related infections. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2003, 33, 863–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyiche, T.E.; Igwenagu, E.; Malgwi, S.A.; Omeh, I.J.; Biu, A.A.; Thekisoe, O. Hematology and biochemical values in equines naturally infected with Theileria equi in Nigeria. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagh, P.R. Effect of Tropical Theileriosis on Erythrocytes in Cattle of Coastal Odisha. Master’s Thesis, Orissa University of Agriculture and Technology, College of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, Bhubaneswar, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, L.; Gazzonis, A.L.; Diezma-Diaz, C.; Perlotti, C.; Zanzani, S.A.; Ferrucci, F.; Álvarez-García, G.; Manfredi, M.T. Besnoitiosis in donkeys: An emerging parasitic disease of equids in Italy. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 1811–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, J.; Sreekumar, C.; Donovan, T.; Rozmanec, M.; Rosenthal, B.; Vianna, M.; Davis, W.; Belden, J. Redescription of Besnoitia bennetti (Protozoa: Apicomplexa) from the donkey (Equus asinus). Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liénard, E.; Nabuco, A.; Vandenabeele, S.; Losson, B.; Tosi, I.; Bouhsira, É.; Prévot, F.; Sharif, S.; Franc, M.; Vanvinckenroye, C. First evidence of Besnoitia bennetti infection (Protozoa: Apicomplexa) in donkeys (Equus asinus) in Belgium. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenmayer, M.C.; Scharr, J.C.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Schares, G.; Gollnick, N.S. Natural Besnoitia besnoiti infections in cattle: Hematological alterations and changes in serum chemistry and enzyme activities. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, I.C.; Goddard, A.; Bronsvoort, B.M.d.C.; Coetzer, J.A.; Booth, C.; Hanotte, O.; Jennings, A.; Kiara, H.; Mashego, P.; Muller, C. Hematological profile of East African short-horn zebu calves from birth to 51 weeks of age. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2013, 22, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, B.; Sori, T.; Kumssa, B. Review on current status of vaccines against parasitic diseases of animals. J. Vet. Sci. Technol. 2016, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboashia, F.A.; Alatrag, F.; Elmarimi, A. Internal parasites (nematode) infestation in pure Arabian horses: Field study. Open Vet. J. 2023, 13, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L. Pathology and Parasitology for Veterinary Technicians; Cengage Learning: Independence, KY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deplazes, P.; Eckert, J.; Mathis, A.; von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G.; Zahner, H. Parasitology in veterinary medicine. In Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Jakhar, K.; Singh, S.; Potliya, S.; Kumar, K.; Pal, M. Clinicopathological studies of gastrointestinal tract disorders in sheep with parasitic infection. Vet. World 2015, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mpofu, T.J.; Nephawe, K.A.; Mtileni, B. Gastrointestinal parasite infection intensity and hematological parameters in South African communal indigenous goats in relation to anemia. Vet. World 2020, 13, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, K.; Ijaz, M.; Ali, M.M.; Khan, I.; Mehmood, K.; Ali, S. Prevalence and hematology of tick borne hemoparasitic diseases in equines in and around Lahore. Pak. J. Zool. 2014, 46, 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Dorrego, A.; Camino, E.; Gago, P.; Buendia-Andres, A.; Acurio, K.; Gonzalez, S.; de Juan, L.; Cruz-Lopez, F. Haemato-biochemical characterization of equine piroplasmosis asymptomatic carriers and seropositive, real-time PCR negative horses. Vet. Parasitol. 2023, 323, 110046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, C.M. Equine piroplasmosis. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2013, 33, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, R.M.Y.; Neira, G.; Bargues, M.D.; Cuervo, P.; Artigas, P.; Logarzo, L.; Cortiñas, G.; Ibaceta, D.E.; Garrido, A.L.; Bisutti, E. Equines as reservoirs of human fascioliasis: Transmission capacity, epidemiology and pathogenicity in Fasciola hepatica-infected mules. J. Helminthol. 2020, 94, e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmeligy, E.; Abdelbaset, A.; Elsayed, H.K.; Bayomi, S.A.; Hafez, A.; Abu-Seida, A.M.; El-Khabaz, K.A.; Hassan, D.; Ghandour, R.A.; Khalphallah, A. Oxidative stress in Strongylus spp. infected donkeys treated with piperazine citrate versus doramectin. Open Vet. J. 2021, 11, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ereqat, S.; Nasereddin, A.; Al-Jawabreh, A.; Al-Jawabreh, H.; Al-Laham, N.; Abdeen, Z. Prevalence of Trypanosoma evansi in livestock in Palestine. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, I.H.R.; Sahito, H.A.; Sanjrani, M.I.; Abbasi, F.; Memon, M.A.; Menghwar, D.R.; Kaka, N.A.; Shah, M.N.; Memon, M. A disease complex pathogen “trypanosoma congolense” transmitted by tsetse fly in donkeys. Her. J. Agric. Food Sci. Res. 2014, 2, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, S.U.; Hyacinth, K.N.; Shinkut, M.; Wilson, E.O.; Sheriff, I.Y.; Bamidele J, K.; Paulin, C.N.; Peter, R.I. Modification of erythrogram, testosterone and prolactin profiles in jacks following experimental infection with Trypanosoma congolense. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 30, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornaś, S.; Pozor, M.; Okólski, A.; Nowosad, B. The case of the nematode Setaria equina found in the vaginal sac of the stallion’s scrotum. Wiad. Parazytol. 2010, 56, 319–321. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.A.M.S.; Rivera Dávila, A.M.; Seidl, A.; Ramirez, L. Trypanosoma evansi and Trypanosoma vivax: Biology, Diagnosis and Control; EMBRAPA: Brasília, Brazil, 2002; Available online: http://www.alice.cnptia.embrapa.br/alice/handle/doc/810940 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Batista, J.; Oliveira, A.; Rodrigues, C.; Damasceno, C.; Oliveira, I.; Alves, H.; Paiva, E.; Brito, P.; Medeiros, J.; Rodrigues, A. Infection by Trypanosoma vivax in goats and sheep in the Brazilian semiarid region: From acute disease outbreak to chronic cryptic infection. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 165, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittar, J.F.; Bassi, P.B.; Moura, D.M.; Garcia, G.C.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Vasconcelos, A.B.; Costa-Silva, M.F.; Barbosa, C.P.; Araújo, M.S.; Bittar, E.R. Evaluation of parameters related to libido and semen quality in Zebu bulls naturally infected with Trypanosoma vivax. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, Y.A.; Noseer, E.A.; Fouad, S.S.; Ali, R.A.; Mahmoud, H.Y. Changes of reproductive indices of the testis due to Trypanosoma evansi infection in dromedary bulls (Camelus dromedarius): Semen picture, hormonal profile, histopathology, oxidative parameters, and hematobiochemical profile. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2020, 7, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hakeem, S.S.; Megahed, G.; Al-Hakami, A.M.; Tolba, M.E.; Karar, Y.F. Impact of trypanosomiasis on male camel infertility. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 11, 1506532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.F. Pathologic conditions of the stallion reproductive tract. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2008, 107, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrnenopoulou, P.; Diakakis, N.; Psalla, D.; Traversa, D.; Papadopoulos, E.; Antonakakis, M. Successful surgical management of eosinophilic granuloma on the urethral process of a gelding associated with Habronema spp. infection. Equine Vet. Educ. 2019, 31, e1–e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Khairullah, A.R.; Khan, A.Y.; Rehman, A.U.; Mustofa, I. Strategic approaches to improve equine breeding and stud farm outcomes. Vet. World 2025, 18, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubcová, J. Reproduction of Domestic Horses (Equus caballus): The Effects of Inbreeding, Social Environment and Breeding Management. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Bohemia České Budějovice, České Budějovice, Czech Republic, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Didier, E.; Stovall, M.; Green, L.; Brindley, P.; Sestak, K.; Didier, P. Epidemiology of microsporidiosis: Sources and modes of transmission. Vet. Parasitol. 2004, 126, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satué, K.; Gardon, J. Pregnancy loss in mares. In Genital Infections and Infertility; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, L.D.R.; Sato, A.P.; de Sousa, R.S.; Rossa, A.P.; Sanches, A.W.D.; Bortoleto, C.T.; Dittrich, R.L. Detection of Neospora spp. and Sarcocystis neurona in amniotic fluid and placentas from mares. Vet. Parasitol. 2022, 303, 109678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimoun, L.; Steinman, A.; Kliachko, Y.; Tirosh-Levy, S.; Schvartz, G.; Blinder, E.; Baneth, G.; Mazuz, M.L. Neospora spp. seroprevalence and risk factors for seropositivity in apparently healthy horses and pregnant mares. Animals 2022, 12, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson-Kane, J.; Caplazi, P.; Rurangirwa, F.; Tramontin, R.; Wolfsdorf, K. Encephalitozoon cuniculi placentitis and abortion in a quarterhorse mare. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2003, 15, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeredi, L.; Pospischil, A.; Dencső, L.; Mathis, A.; Dobos-Kovács, M. A case of equine abortion caused by Encephalitozoon sp. Acta Vet. Hung. 2007, 55, 525–532. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdy, O.A.; Nassar, A.M.; Mohamed, B.S.; Mahmoud, M.S. Comparative diagnosis utilizing molecular and serological techniques of Theileria equi infection in distinct equine populations in Egypt. Int. J. Chem Tech Res. 2016, 9, 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa, S.H.; Paludo, G.R.; Freschi, C.R.; Machado, R.Z.; de Castro, M.B. Theileria equi infection causing abortion in a mare in Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2017, 8, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirosh-Levy, S.; Gottlieb, Y.; Mimoun, L.; Mazuz, M.L.; Steinman, A. Transplacental transmission of Theileria equi is not a common cause of abortions and infection of foals in Israel. Animals 2020, 10, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirosh-Levy, S.; Gottlieb, Y.; Mazuz, M.L.; Savitsky, I.; Steinman, A. Infection dynamics of Theileria equi in carrier horses is associated with management and tick exposure. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouam, M.K.; Kantzoura, V.; Gajadhar, A.A.; Theis, J.H.; Papadopoulos, E.; Theodoropoulos, G. Seroprevalence of equine piroplasms and host-related factors associated with infection in Greece. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 169, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.; Toledo, C.; Teixeira, M.; André, M.; Freschi, C.; Sampaio, P. Molecular and serological detection of Theileria equi and Babesia caballi in donkeys (Equus asinus) in Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 186, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, L.N.; Pelzel-McCluskey, A.M.; Mealey, R.H.; Knowles, D.P. Equine piroplasmosis. Vet. Clin. Equine Pract. 2014, 30, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.A.; Alves, D.A.; Cerqueira-Cézar, C.K.; da Silva, A.F.; Murata, F.H.; Norris, J.K.; Howe, D.K.; Dubey, J.P. Histologically, immunohistochemically, ultrastructurally, and molecularly confirmed neosporosis abortion in an aborted equine fetus. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 270, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, A.; Krüger, C.; Strube, C.; Steinhauer, D. Worms and reproductive failure: First evidence of transplacental Halicephalobus transmission leading to repeated equine abortion. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector-Borne Dis. 2025, 8, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begg, A.P.; Todhunter, K.; Donahoe, S.L.; Krockenberger, M.; Šlapeta, J. Severe amoebic placentitis in a horse caused by an Acanthamoeba hatchetti isolate identified using next-generation sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 3101–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.; Vianna, S. Gastrointestinal parasitic worms in equines in the Paraíba Valley, State of São Paulo, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 140, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getahun, T.K.; Kassa, T.Z. Prevalence and species of major gastrointestinal parasites of donkeys in Tenta Woreda, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. J. Vet. Med. Anim. Health 2017, 9, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, P.-H.; Chuluun, S.; Sodnomdarjaa, R.; Greiner, M.; Noeckler, K.; Staak, C.; Zessin, K.-H.; Schein, E. A field study to estimate the prevalence of Trypanosoma equiperdum in Mongolian horses. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 115, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Wang, X.; She, L.-N.; Fan, Y.-T.; Yuan, F.-Z.; Yang, J.-F.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Zou, F.-C. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in horses and donkeys in Yunnan Province, Southwestern China. Parasites Vectors 2013, 6, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, C.; Melchert, M.; Aurich, J.; Aurich, C. Road transport of late-pregnant mares advances the onset of foaling. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2020, 86, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnerová, P.; Sak, B.; Květoňová, D.; Xiao, L.; Rost, M.; McEvoy, J.; Saadi, A.R.; Aissi, M.; Kváč, M. Microsporidia and Cryptosporidium in horses and donkeys in Algeria: Detection of a novel Cryptosporidium hominis subtype family (Ik) in a horse. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 208, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Klun, I.; Uzelac, A.; Villena, I.; Mercier, A.; Bobić, B.; Nikolić, A.; Rajnpreht, I.; Opsteegh, M.; Aubert, D.; Blaga, R. The first isolation and molecular characterization of Toxoplasma gondii from horses in Serbia. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomares, C.; Ajzenberg, D.; Bornard, L.; Bernardin, G.; Hasseine, L.; Darde, M.-L.; Marty, P. Toxoplasmosis and horse meat, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boughattas, S. Toxoplasma infection and milk consumption: Meta-analysis of assumptions and evidences. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2924–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfaldoni, C.; Barlozzari, G.; Mancini, S.; ELISABETTA, D.D.; Maestrini, M.; Perrucci, S. Parasitological investigation in an organic dairy donkey farm. LARGE Anim. Rev. 2020, 26, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ragona, G.; Corrias, F.; Benedetti, M.; Paladini, M.; Salari, F.; Martini, M. Amiata donkey milk chain: Animal health evaluation and milk quality. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2016, 5, 5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancianti, F.; Nardoni, S.; Papini, R.; Mugnaini, L.; Martini, M.; Altomonte, I.; Salari, F.; D’Ascenzi, C.; Dubey, J.P. Detection and genotyping of Toxoplasma gondii DNA in the blood and milk of naturally infected donkeys (Equus asinus). Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P.; Ness, S.L.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Choudhary, S.; Mittel, L.; Divers, T. Seropositivity of Toxoplasma gondii in domestic donkeys (Equus asinus) and isolation of T. gondii from farm cats. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 199, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlier, J.; Duchateau, L.; Claerebout, E.; Williams, D.; Vercruysse, J. Associations between anti-Fasciola hepatica antibody levels in bulk-tank milk samples and production parameters in dairy herds. Prev. Vet. Med. 2007, 78, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.; Sajid, M.S.; Khan, M.N.; Iqbal, Z.; Iqbal, M.U. Bovine fasciolosis: Prevalence, effects of treatment on productivity and cost benefit analysis in five districts of Punjab, Pakistan. Res. Vet. Sci. 2009, 87, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köstenberger, K.; Tichy, A.; Bauer, K.; Pless, P.; Wittek, T. Associations between fasciolosis and milk production, and the impact of anthelmintic treatment in dairy herds. Parasitol. Res. 2017, 116, 1981–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byford, R.; Craig, M.; Crosby, B. A review of ectoparasites and their effect on cattle production. J. Anim. Sci. 1992, 70, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahaotu, E.; Simeon-Ahaotu, V.; Alsharifi, S.; Herasymenko, N.; Hagos, H.; Iheanacho, R. Effects of ectoparasites on cattle in agro-ecological zones in Nigeria—A review. J. Vet. Res. Adv. 2024, 6, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bah, M. Effects of Arthropod Ectoparasite Infestations on Livestock Productivity in Three Districts in Southern Ghana. Master’s Thesis, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mezo, M.; González-Warleta, M.; Castro-Hermida, J.A.; Muino, L.; Ubeira, F.M. Association between anti-F. hepatica antibody levels in milk and production losses in dairy cows. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 180, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touratier, L. A challenge of veterinary public health in the European Union: Human trichinellosis due to horse meat consumption. Parasite 2001, 8, S252–S256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bezerra, F.S.B.; Batista, J.S. Efeitos da infecção por Trypanosoma vivax sobre a reprodução: Uma revisão. Acta Vet. Bras. 2008, 2, 61–66. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Almeida, K.S.; da Costa Freitas, F.L.; Jorge, R.L.N.; da Silva Nogueira, C.A.; Machado, R.Z.; do Nascimento, A.A. Aspectos hematológicos da infecção experimental por Trypanosoma vivax em ovinos. Ciência Anim. Bras./Braz. Anim. Sci. 2008, 9, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Álvarez-García, G.; Frey, C.F.; Mora, L.M.O.; Schares, G. A century of bovine besnoitiosis: An unknown disease re-emerging in Europe. Trends Parasitol. 2013, 29, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, H.; Leitao, A.; Gottstein, B.; Hemphill, A. A review on bovine besnoitiosis: A disease with economic impact in herd health management, caused by Besnoitia besnoiti (Franco and Borges, 1916). Parasitology 2014, 141, 1406–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzonis, A.L.; Alvarez Garcia, G.; Maggioni, A.; Zanzani, S.A.; Olivieri, E.; Compiani, R.; Sironi, G.; Ortega Mora, L.M.; Manfredi, M.T. Serological dynamics and risk factors of Besnoitia besnoiti infection in breeding bulls from an endemically infected purebred beef herd. Parasitol. Res. 2017, 116, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabbott, N.A. The influence of parasite infections on host immunity to co-infection with other pathogens. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, M.; Li, M.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, W.; Ma, Q.; Wang, C. Advances in Donkey Disease Surveillance and Microbiome Characterization in China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khedri, J.; Radfar, M.H.; Nikbakht, B.; Zahedi, R.; Hosseini, M.; Azizzadeh, M.; Borji, H. Parasitic causes of meat and organs in cattle at four slaughterhouses in Sistan-Baluchestan Province, Southeastern Iran between 2008 and 2016. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 7, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, O.; Shakerian, A. Investigation of parasitic contamination of protein products produced in Isfahan industrial slaughterhouse. Rev. Investig. Univ. Del Quindío 2023, 35, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, H.M.; Zohaib, H.M.; Sajid, M.S.; Abbas, H.; Younus, M.; Farid, M.U.; Iftakhar, T.; Muzaffar, H.A.; Hassan, S.S.; Kamran, M. Inflicting significant losses in slaughtered animals: Exposing the hidden effects of parasitic infections. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, H.; Zhao, X.; Fang, Y.; Wang, F.; Liang, R.; Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Zhong, R. Feeding fungal-pretreated corn straw improves health and meat quality of lambs infected with gastrointestinal nematodes. Animals 2020, 10, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Teng, H.; Zhu, L.; Ni, B.; Jiewei, L.; Shanshan, L.; Yunong, Z.; Guo, X.; Lamu, D. The impact of Sarcocystis infection on lamb flavor metabolites and its underlying molecular mechanisms. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1543081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, A.; Oladunni, F.S.; Gonchigoo, B.; Chambers, T.M.; Gray, G.C. Zoonotic diseases from horses: A systematic review. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2020, 20, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, I. New and emerging parasitic zoonoses. In Emerging Zoonoses: A Worldwide Perspective; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 211–239. [Google Scholar]

- Dupouy-Camet, J. History of trichinellosis in the history of the catalog of the French National Library. Hist. Des Sci. Medicales 2015, 49, 411–420. [Google Scholar]

- Murrell, K.; Djordjevic, M.; Cuperlovic, K.; Sofronic, L.; Savic, M.; Damjanovic, S. Epidemiology of Trichinella infection in the horse: The risk from animal product feeding practices. Vet. Parasitol. 2004, 123, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agholi, M.; Taghadosi, Z.; Mehrabani, D.; Zahabiun, F.; Sharafi, Z.; Motazedian, M.H.; Hatam, G.R.; Naderi Shahabadi, S. Human intestinal sarcocystosis in Iran: There but not seen. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 4527–4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, B.M. Zoonotic sarcocystis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2021, 136, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, Y.; Saito, M.; Irikura, D.; Yahata, Y.; Ohnishi, T.; Bessho, T.; Inui, T.; Watanabe, M.; Sugita-Konishi, Y. A toxin isolated from Sarcocystis fayeri in raw horsemeat may be responsible for food poisoning. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rommel, M.; Geisel, O. Studies on the incidence and life cycle of a sarcosporidian species of the horse (Sarcocystis equicanis n. spec). Berl. Und Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 1975, 88, 468–471. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, J.; Streitel, R.; Stromberg, P.; Toussant, M. Sarcocystis fayeri sp. n. from the horse. J. Parasitol. 1977, 63, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinaidy, H.; Loupal, G. Sarcocystis bertrami Doflein, 1901, ein Sarkosporid des Pferdes, Equus caballus. Zentralblatt Für Veterinärmedizin Reihe B 1982, 29, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnieder, T.; Zimmermann, U.; Matuschka, F.; Bürger, H.J.; Rommel, M. Zur Klinik, Enzymaktivität und Antikörperbildung bei experimentell mit Sarkosporidien infizierten Pferden 1. Zentralblatt Für Veterinärmedizin Reihe B 1985, 32, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyo, M.; Battsetseg, G.; Byambaa, B. Prevalence of Sarcocystis infection in horses in Mongolia. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2002, 33, 718–719. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, G. Prevalence of equine sarcocystis in British horses and a comparison of two detection methods. Vet. Rec. 1984, 115, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erber, M.; Geisel, O. Vorkommen und entwicklung von 2 sarkosporidienarten des pferdes. Z. Für Parasitenkd. 1981, 65, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmse, P. Sarcosporidiosis in equines of Morocco. Br. Vet. J. 1986, 142, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthorn, R.J.; Clark, M.; Hudson, R.; Friesen, D. Histological and ultrastructural appearance of severe Sarcocystis fayeri infection in a malnourished horse. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 1990, 2, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Sarriés, M.V.; Tateo, A.; Polidori, P.; Franco, D.; Lanza, M. Carcass characteristics, meat quality and nutritional value of horsemeat: A review. Meat Sci. 2014, 96, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, C.; da Silva, B.; Nogueira, Y.; Bezerra, T.; Tavares, A.; Borges-Silva, W.; Gondim, L. Brazilian horses from Bahia state are highly infected with Sarcocystis bertrami. Animals 2022, 12, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobanski, V.; Ajzenberg, D.; Delhaes, L.; Bautin, N.; Just, N. Severe toxoplasmosis in immunocompetent hosts: Be aware of atypical strains. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 1143–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbez-Rubinstein, A.; Ajzenberg, D.; Dardé, M.-L.; Cohen, R.; Dumètre, A.; Yera, H.; Gondon, E.; Janaud, J.-C.; Thulliez, P. Congenital toxoplasmosis and reinfection during pregnancy: Case report, strain characterization, experimental model of reinfection, and review. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalidi, N.W.; Dubey, J. Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in horses. J. Parasitol. 1979, 65, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaapan, R.; Ghazy, A. Isolation of Toxoplasma gondii from horse meat in Egypt. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. PJBS 2007, 10, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, F.; Garcia, J.L.; Navarro, I.T.; Zulpo, D.L.; Nino, B.d.S.L.; Ewald, M.P.d.C.; Pagliari, S.; Almeida, J.C.d.; Freire, R.L. Diagnosis and isolation of Toxoplasma gondii in horses from Brazilian slaughterhouses. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Veterinária 2013, 22, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paştiu, A.I.; Györke, A.; Kalmár, Z.; Bolfă, P.; Rosenthal, B.M.; Oltean, M.; Villena, I.; Spînu, M.; Cozma, V. Toxoplasma gondii in horse meat intended for human consumption in Romania. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 212, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amairia, S.; Jbeli, M.; Mrabet, S.; Jebabli, L.M.; Gharbi, M. Molecular prevalence of Sarcocystis spp. and toxoplasma gondii in slaughtered equids in northern Tunisia. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2023, 129, 104894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.; Malalana, F.; Beesley, N.; Hodgkinson, J.; Rhodes, H.; Sekiya, M.; Archer, D.; Clough, H.; Gilmore, P.; Williams, D. Fasciola hepatica in UK horses. Equine Vet. J. 2020, 52, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelli, R.; Calistri, P.; Giovannini, A.; Caporale, V. Evidence of T. equiperdum infection in the Italian Dourine outbreaks. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2012, 32, S70–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzouzi, C.; Rabah-Sidhoum, N.; Boucheikhchoukh, M.; Mechouk, N.; Sedraoui, S.; Benakhla, A. Checklist of Medico-Veterinary Important Biting Flies (Ceratopogonidae, Hippoboscidae, Phlebotominae, Simuliidae, Stomoxyini, and Tabanidae) and Their Associated Pathogens and Hosts in Maghreb. Parasitologia 2024, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizaw, Y.; Megersa, M.; Fayera, T. Dourine: A neglected disease of equids. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2017, 49, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, M.A.; El-Gameel, S.M.; Kamel, M.S.; Elsamman, E.M.; Ramadan, R.M. Innovative diagnostic strategies for equine habronemiasis: Exploring molecular identification, gene expression, and oxidative stress markers. Parasites Vectors 2025, 18, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.C. Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their Development and Transmission, 2nd ed.; Cabi: Oxfordshire, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Traversa, D.; Otranto, D.; Iorio, R.; Carluccio, A.; Contri, A.; Paoletti, B.; Bartolini, R.; Giangaspero, A. Identification of the intermediate hosts of Habronema microstoma and Habronema muscae under field conditions. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2008, 22, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, J. Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, D.; Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasma gondii: Transmission, diagnosis and prevention. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2002, 8, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueti, M.W.; Palmer, G.H.; Scoles, G.A.; Kappmeyer, L.S.; Knowles, D.P. Persistently infected horses are reservoirs for intrastadial tick-borne transmission of the apicomplexan parasite Babesia equi. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 3525–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.; Schares, G.; Ortega-Mora, L. Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 323–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano-Cabral, F.; Cabral, G. Acanthamoeba spp. as agents of disease in humans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16, 273–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todhunter, K.; Cawdell-Smith, A.; Bryden, W.; Perkins, N.; Begg, A. Processionary caterpillar setae and equine fetal loss: 1. Histopathology of experimentally exposed pregnant mares. Vet. Pathol. 2014, 51, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, E.O. Prevalence and Control of Strongyle Nematode Infections of Horses in Sweden; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Uppsala, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmina, T.; Kuzmin, Y.; Kharchenko, V.A. Field study on the survival, migration and overwintering of infective larvae of horse strongyles on pasture in central Ukraine. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 141, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birhanu, H.; Gebrehiwot, T.; Goddeeris, B.M.; Büscher, P.; Van Reet, N. New Trypanosoma evansi type B isolates from Ethiopian dromedary camels. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuypers, B.; Van den Broeck, F.; Van Reet, N.; Meehan, C.J.; Cauchard, J.; Wilkes, J.M.; Claes, F.; Goddeeris, B.; Birhanu, H.; Dujardin, J.-C. Genome-wide SNP analysis reveals distinct origins of Trypanosoma evansi and Trypanosoma equiperdum. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017, 9, 1990–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.-L.; Liu, G.-Y.; Xie, J.-R.; Chai, H.-P.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Li, Z.-X.; Tian, Z.-C.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.-G. An indirect ELISA for the detection of Babesia caballi in equine animals. Chin. J. Parasitol. Parasit. Dis. 2010, 28, 200–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ahedor, B.; Sivakumar, T.; Valinotti, M.F.R.; Otgonsuren, D.; Yokoyama, N.; Acosta, T.J. PCR detection of Theileria equi and Babesia caballi in apparently healthy horses in Paraguay. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2023, 39, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Nielsen, M.K. An evidence-based approach to equine parasite control: It ain’t the 60s anymore. Equine Vet. Educ. 2010, 22, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L. Shining a Light on Molecular Detection of Agriculturally Important Livestock Parasites and Their Vectors: Development of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Methods for Small Ruminant Farming. Ph.D. Thesis, La Trobe University, Victoria, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Elghryani, N.; McAloon, C.; Mincher, C.; McOwan, T.; Waal, T.d. Comparison of the automated OvaCyte telenostic faecal analyser versus the McMaster and Mini-FLOTAC techniques in the estimation of helminth faecal egg counts in equine. Animals 2023, 13, 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.K.; Anderson, U.; Howe, D.K. Diagnosis of Strongylus vulgaris. U.S. Patent US 8,951,741 B1, 10 February 2015. Available online: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gluck_patents/3 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Hodgkinson, J.E. Molecular diagnosis and equine parasitology. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 136, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giangaspero, A.; Traversa, D.; Otranto, D. A new tool for the diagnosis in vivo of habronemosis in horses. Equine Vet J. 2005, 37, 263–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonello, A.M.; Pivoto, F.L.; Camillo, G.; Braunig, P.; Sangioni, L.A.; Pompermayer, E.; Vogel, F.S.F. The importance of vertical transmission of Neospora sp. in naturally infected horses. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 187, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sáez, L.; Pala, S.; Marín-García, P.J.; Llobat, L. Serological and molecular detection of Toxoplasma gondii infection in apparently healthy horses in eastern of Spain. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2024, 54, 101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, T.R.; Pinto, F.F.; Queiroga, F.L. A multidisciplinary review about Encephalitozoon cuniculi in a One Health perspective. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 121, 2463–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagos, A.; Goddeeris, B.; Yilkal, K.; Alemu, T.; Fikru, R.; Yacob, H.; Feseha, G.; Claes, F. Efficacy of Cymelarsan® and Diminasan® against Trypanosoma equiperdum infections in mice and horses. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 171, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendle, D.; Hughes, K.; Bowen, M.; Bull, K.; Cameron, I.; Furtado, T.; Peachey, L.; Sharpe, L.; Hodgkinson, J. BEVA primary care clinical guidelines: Equine parasite control. Equine Vet. J. 2024, 56, 392–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felippelli, G.; Cruz, B.C.; Gomes, L.V.C.; Lopes, W.D.Z.; Teixeira, W.F.P.; Maciel, W.G.; Buzzulini, C.; Bichuette, M.A.; Campos, G.P.; Soares, V.E. Susceptibility of helminth species from horses against different chemical compounds in Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 212, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, J.P. Review of Neospora caninum and neosporosis in animals. Korean J. Parasitol. 2003, 41, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pino, L.E.B.; Roberto, N.; Vincenzo, V.; Francesca, I.; Antonella, C.; Luca, A.G.; Francesco, B.; Teresa, S.M. Babesia caballi and Theileria equi infections in horses in Central-Southern Italy: Sero-molecular survey and associated risk factors. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2016, 7, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salib, F.A.; Youssef, R.R.; Rizk, L.G.; Said, S.F. Epidemiology, diagnosis and therapy of Theileria equi infection in Giza, Egypt. Vet. World 2013, 6, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyiche, T.E.; Suganuma, K.; Igarashi, I.; Yokoyama, N.; Xuan, X.; Thekisoe, O. A review on equine piroplasmosis: Epidemiology, vector ecology, risk factors, host immunity, diagnosis and control. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauparaitė, E.; Kupčinskas, T.; Hoglund, J.; Petkevičius, S. A survey of control strategies for equine small strongyles in Lithuania. Helminthologia 2021, 58, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.B. Anthelmintic resistance in equine nematodes. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2014, 4, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikha, H.M.; Schares, G.; Paraschou, G.; Sullivan, R.; Fox, R. First record of besnoitiosis caused by Besnoitia bennetti in donkeys from the UK. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leathwick, D.M.; Sauermann, C.W.; Nielsen, M.K. Managing anthelmintic resistance in cyathostomin parasites: Investigating the benefits of refugia-based strategies. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2019, 10, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M. Parasite faecal egg counts in equine veterinary practice. Equine Vet. Educ. 2022, 34, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peregrine, A.S.; Molento, M.B.; Kaplan, R.M.; Nielsen, M.K. Anthelmintic resistance in important parasites of horses: Does it really matter? Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 201, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, G.T.; Corrêa, D.C.; Chitolina, M.B.; da Rosa, G.; da Fontoura Pereira, R.C.; Cargnelutti, J.F.; Vogel, F.S.F. Efficacy evaluation of a commercial formulation with Duddingtonia flagrans in equine gastrointestinal nematodes. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2023, 131, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzatti, A.; de Paula Santos, C.; Fernandes, M.A.M.; Yoshitani, U.Y.; Sprenger, L.K.; dos Santos, C.D.; Molento, M.B. Duddingtonia flagrans in the control of gastrointestinal nematodes of horses. Exp. Parasitol. 2015, 159, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudena, M.; Chapman, M.; Larsen, M.; Klei, T. Efficacy of the nematophagous fungus Duddingtonia flagrans in reducing equine cyathostome larvae on pasture in south Louisiana. Vet. Parasitol. 2000, 89, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausto, G.C.; Fausto, M.C.; Vieira, Í.S.; de Freitas, S.G.; de Carvalho, L.M.; de Castro Oliveira, I.; Silva, E.N.; Campos, A.K.; de Araújo, J.V. Formulation of the nematophagous fungus Duddingtonia flagrans in the control of equine gastrointestinal parasitic nematodes. Vet. Parasitol. 2021, 295, 109458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Additives, E.P.o.; Feed, P.o.S.u.i.A.; Bampidis, V.; Azimonti, G.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; Christensen, H.; Dusemund, B.; Kos Durjava, M.; Kouba, M.; López-Alonso, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of BioWorma®(Duddingtonia flagrans NCIMB 30336) as a feed additive for all grazing animals. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06208. [Google Scholar]

- Peachey, L.; Pinchbeck, G.; Matthews, J.; Burden, F.; Mulugeta, G.; Scantlebury, C.; Hodgkinson, J. An evidence-based approach to the evaluation of ethnoveterinary medicines against strongyle nematodes of equids. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 210, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, F.; Luoga, W.; Buttle, D.; Duce, I.; Lowe, A.; Behnke, J. The anthelmintic efficacy of natural plant cysteine proteinases against the equine tapeworm, Anoplocephala perfoliatain vitro. J. Helminthol. 2016, 90, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Yan, X.; Su, Y.; Gao, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, W. Progress in serology and molecular biology of equine parasite diagnosis: Sustainable control strategies. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1663577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, A.; Qamar, A.G.; Hayat, K.; Ashraf, S.; Williams, A.R. Anthelmintic resistance and novel control options in equine gastrointestinal nematodes. Parasitology 2019, 146, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, H. Anthelmintic Resistance in Equine Parasites: An Epidemiological Approach to Build a Framework for Sustainable Parasite Control. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liverpool, England, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, E.R.; Lanusse, C.; Rinaldi, L.; Charlier, J.; Vercruysse, J. Confounding factors affecting faecal egg count reduction as a measure of anthelmintic efficacy. Parasite 2022, 29, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khusro, A.; Aarti, C.; Buendía-Rodriguez, G.; Arasu, M.V.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Barbabosa-Pliego, A. Adverse effect of antibiotics administration on horse health: An overview. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2021, 97, 103339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, B.L.M.; Elghandour, M.M.; Adegbeye, M.J.; González, D.N.T.; Estrada, G.T.; Salem, A.Z.; Pacheco, E.B.F.; Pliego, A.B. Use of antibiotics in equines and their effect on metabolic health and cecal microflora activities. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2021, 105, 103717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, R.E.; Whitt, B.; Bladon, B.M. Antibiotic usage in 14 equine practices over a 10-year period (2012–2021). Equine Vet. J. 2024, 56, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuntasuvan, D.; Jarabrum, W.; Viseshakul, N.; Mohkaew, K.; Borisutsuwan, S.; Theeraphan, A.; Kongkanjana, N. Chemotherapy of surra in horses and mules with diminazene aceturate. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 110, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, L.; Guitton, E.; Madeline, A.; Géraud, T.; Zientara, S.; Laugier, C.; Hans, A.; Büscher, P.; Cauchard, J.; Petry, S. Melarsomine hydrochloride (Cymelarsan®) fails to cure horses with Trypanosoma equiperdum OVI parasites in their cerebrospinal fluid. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 264, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grause, J.F.; Ueti, M.W.; Nelson, J.T.; Knowles, D.P.; Kappmeyer, L.S.; Bunn, T.O. Efficacy of imidocarb dipropionate in eliminating Theileria equi from experimentally infected horses. Vet. J. 2013, 196, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionita, M.; Nicorescu, I.M.; Pfister, K.; Mitrea, I.L. Parasitological and molecular diagnostic of a clinical Babesia caballi outbreak in Southern Romania. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 2333–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herd, R.; Donham, J. Efficacy of ivermectin against cutaneous Draschia and Habronema infection (summer sores) in horses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1981, 42, 1953–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.; Farlam, J.; Proudman, C.J. Field trial of the efficacy of a combination of ivermectin and praziquantel in horses infected with roundworms and tapeworms. Vet. Rec. 2004, 154, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.E.; Voris, N.D.; Ortis, H.A.; Geeding, A.A.; Kaplan, R.M. Comparison of a single dose of moxidectin and a five-day course of fenbendazole to reduce and suppress cyathostomin fecal egg counts in a herd of embryo transfer–recipient mares. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2014, 245, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ullah, A.; Geng, M.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Q.; Shi, L.; Zhang, X.; Akhtar, M.F.; Wang, C.; Khan, M.Z. Effect of Parasitic Infections on Hematological Profile, Reproductive and Productive Performance in Equines. Animals 2025, 15, 3294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223294

Ullah A, Geng M, Chen W, Zhu Q, Shi L, Zhang X, Akhtar MF, Wang C, Khan MZ. Effect of Parasitic Infections on Hematological Profile, Reproductive and Productive Performance in Equines. Animals. 2025; 15(22):3294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223294

Chicago/Turabian StyleUllah, Abd, Mingyang Geng, Wenting Chen, Qifei Zhu, Limeng Shi, Xuemin Zhang, Muhammad Faheem Akhtar, Changfa Wang, and Muhammad Zahoor Khan. 2025. "Effect of Parasitic Infections on Hematological Profile, Reproductive and Productive Performance in Equines" Animals 15, no. 22: 3294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223294

APA StyleUllah, A., Geng, M., Chen, W., Zhu, Q., Shi, L., Zhang, X., Akhtar, M. F., Wang, C., & Khan, M. Z. (2025). Effect of Parasitic Infections on Hematological Profile, Reproductive and Productive Performance in Equines. Animals, 15(22), 3294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223294