Reader Responses to Online Reporting of Tagged Bird Behavior

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Organizing the Data

2.3. Analytical Approach

3. Results

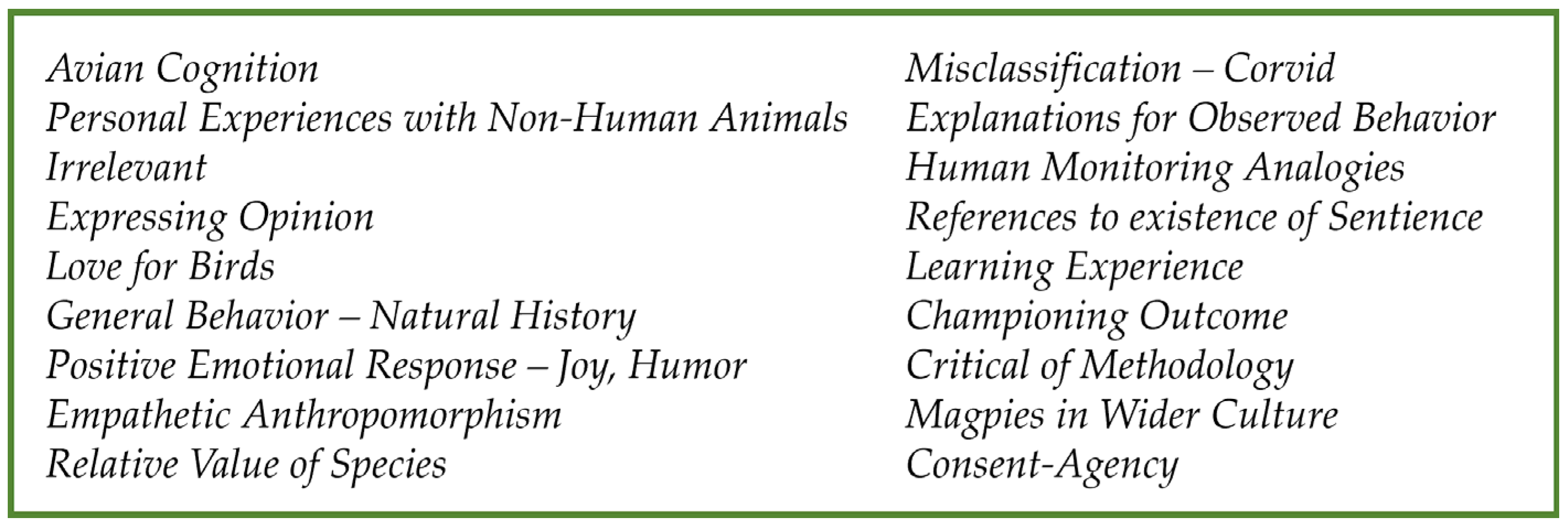

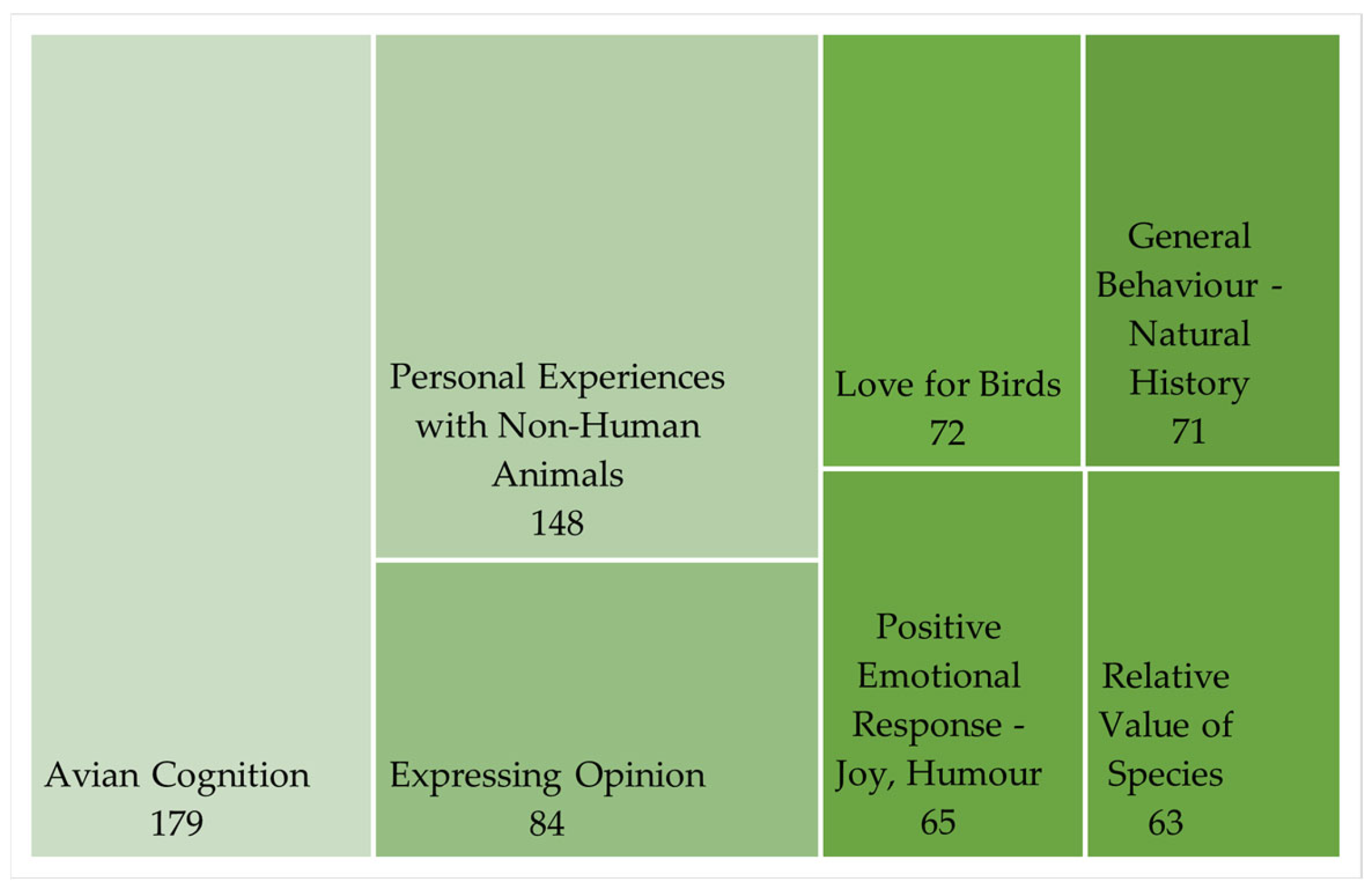

3.1. Thematic Analysis

Main Themes

- 1.

- Sharing personal feelings and experiences

“When a magpie became entangled in a “bird friendly” bird net encasing our favorite fruit tree, we slipped quietly under the net to try and free him/her. A small crowd of magpies gathered on the shed roof nearby and watched, making encouraging warbling noises. When freed there was—and there was no doubt about this—a chorus of approval and finally, a song of praise…”(Respondent 327)

“How would you like a tracker attached to you without consent. I believe I’d fight back.”(Respondent 283)

- 2.

- Comparing the merits of different species

“…They are such an intelligent bird—beats humans every time.”(Respondent 271)

“This article appeared in the Conversation a few days ago, and caused quite a ruckus from an amazing number of people. The ruckus was not because of how amazing Magpies are, but how stupid scientists are…”(Respondent 435)

“For a group of [Australian] magpies, we are “their” humans… we don’t hassle them, they don’t hassle us. Peaceful co-existence.”(Respondent 393)

“Well done. two fingers to the scientists until they design something that will really annoy them.”(Respondent 98)

“Clearly these magpies were able to communicate that they didn’t like these sensors. Good on them for figuring a way to get rid of this intrusion. Researchers should take this reaction into consideration for future studies!”(Respondent 198)

- 3.

- Sharing knowledge and opinion

“They are incredibly intelligent and curious, and of course social. I do wonder though whether they were actually rescuing each other, or just being inquisitive about their tracker…”(Respondent 42)

“Altruism can occur for sure! Rescue behavior is quite rarely observed, however.:)”(Respondent 47)

“Surely putting a removable tracker on a social corvid that routinely allogrooms is asking for trouble?”(Respondent 73)

“[…] It seems to also present a case of a somewhat round about negotiation of consent. When we put on trackers/flags/rings we try to make them as unobtrusive as possible but can’t tell exactly how annoying they are. These magpies have provided a great example of agency in removing the trackers. This brings new ethical considerations to the work…”(Respondent 1)

“Who said the GPS trackers were non-invasive? The scientists, of course. Who, I am sure if they were imposed upon to wear trackers of a proportionately equivalent size to what they were sticking on the magpies, would do their damnedest to be rid of. A scientific survey of scientists seems long overdue. A collection of stick on and strap on devices used on birds and animals should be attached to a representative group of scientists and research over a lengthy period conducted…”(Respondent 613)

3.2. Balance of Opinion

3.2.1. Comparison of Opinions Between Publications

3.2.2. Indirect Support

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lahoz-Monfort, J.J.; Magrath, M.J.L. A Comprehensive Overview of Technologies for Species and Habitat Monitoring and Conservation. Bioscience 2021, 71, 1038–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.M.; Raby, G.D.; Hinch, S.G.; Cooke, S.J. Aboriginal fisher perspectives on use of telemetry technology to study adult Pacific salmon. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2012, 406, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, C.R.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Hays, G.C. Applying the Heat to Research Techniques for Species Conservation. Cons. Biol. 2007, 21, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A.; Greenhough, B. Out of the laboratory, into the field: Perspectives on social, ethical and regulatory challenges in UK wildlife research. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2021, 376, 20200226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbrook, C.; Fisher, J.A.; Holmes, G.; Luque-Lora, R.; Keane, A. The global conservation movement is diverse but not divided. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crampton, J.; Frère, C.H.; Potvin, D.A. Australian Magpies (Gymnorhina tibicen) cooperate to remove tracking devices. Aust. Field Ornithol. 2022, 39, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowbahari, E.; Hollis, K.L. Rescue behavior: Distinguishing between rescue, cooperation and other forms of altruistic behavior. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2010, 3, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, D. Altruism in Birds? Magpies Have Outwitted Scientists by Helping Each Other Remove Tracking Devices. The Conversation, 21 February 2022. Available online: https://theConversation.com/altruism-in-birds-magpies-have-outwitted-scientists-by-helping-each-other-remove-tracking-devices-175246 (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- First Dog on the Moon. Magpies: Courageous Heroes or Little Feathery Bastards. The Guardian, 25 February 2022. Available online: https://www.theGuardian.com/commentisfree/2022/feb/25/magpies-courageous-heroes-or-little-feathery-bastards (accessed on 26 February 2022).

- Springer, N.; Engelmann, I.; Pfaffinger, C. User comments: Motives and inhibitors to write and read. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18, 798–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Atkin, D. Online News Discussions: Exploring the Role of User Personality and Motivations for Posting Comments on News. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 2017, 94, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A. Interactive to me—Interactive to you? A study of use and appreciation of interactivity on Swedish newspaper websites. New Media Soc. 2011, 13, 1180–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, T. Cheeky Magpies Help Each Other Remove Sophisticated GPS Harnesses—Ruining a Year of Scientific Work. Daily Mail/Australian Associated Press, 22 February 2022. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10537623/Cheeky-magpies-help-remove-GPS-harnesses-ruining-year-scientific-work.html (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol. 2. Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. University of Aukland. Available online: https://www.thematicanalysis.net (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Phillips, N.; Hardy, C. Discourse Analysis: Investigating Processes of Social Construction; Sage Publications Inc.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.O.; Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Snyder-Duch, J.; Bracken, C.C. Practical Resources for Assessing and Reporting Intercoder Reliability in Content Analysis Research Projects 2010. Available online: https://matthewlombard.com/reliability/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Root-Bernstein, M.; Douglas, L.; Smith, A.; Veríssimo, D. Anthropomorphized species as tools for conservation: Utility beyond prosocial, intelligent and suffering species. Biodivers. Conserv. 2013, 22, 1577–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okasha, S. Biological Altruism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Summer 2020 Edition; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/altruism-biological/ (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Harrison, M.A.; Hall, A.E. Anthropomorphism, Empathy, and Perceived Communicative Ability vary with Phylogenetic Relatedness to Humans. J. Soc. Evol. Cult. Psychol. 2010, 4, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, D.; Perconti, P.; Plebe, A. Anti-anthropomorphism and Its Limits. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, K. Anthropomorphism or Egomorphism? The Perception of Non-human Persons by Human Ones. In Animals in Person: Cultural Perspectives on Human-Animal Intimacies; Knight, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, R.D. Speciesism Again: The original leaflet. Crit. Soc. 2010, 2, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, H.K.; Speakman, B. Quieting the Commenters: The Spiral of Silence’s Persistent Effect on Online News Forums (Research Blog). Int. Symp. Online J. 2016, 6, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nekmat, E.; Gonzenbach, W.J. Multiple opinion climates in online forums: Role of website source reference and within-forum opinion congruency. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2013, 90, 736–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, N.; Holmes, B. Web news readers’ comments: Towards developing a methodology for using on-line comments in social inquiry. J. Media Commun. Stud. 2013, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kangaspunta, V. Internet Users’ Reasons and Motives for Online News Commenting. Int. J. Commun. 2021, 15, 4480–4502. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Oeldorf-Hirsch, A.; Atkin, D. A Click Is Worth a Thousand Words: Probing the Predictors of Using Click Speech for Online Opinion Expression. Int. J. Commun. 2020, 14, 2687–2706. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, B. Sustainability. A Philosophy of Adaptive Ecosystem Management (Part II: Value Pluralism and Cooperation); The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005; pp. 147–400. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, H.L.; Loring, P.A. Seeing beneath disputes: A transdisciplinary framework for diagnosing complex conservation conflicts. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 248, 108670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keulartz, J. Does Deliberation Promote Ecological Citizenship? The Convergence Hypothesis and the Reality of Polarization. In A Sustainable Philosophy: The Work of Bryan Norton; Sarkar, S., Minteer, B., Eds.; The International Library of Environmental, Agricultural and Food Ethics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 26, pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, F.; McQuinn, B. Conservation’s blind spot: The case for conflict transformation in wildlife conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 178, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppli, C.A.; Fraser, D. Factors influencing the effectiveness of research ethics Committees. J. Med. Ethics 2007, 33, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cognitive Dimension | Satisfaction is derived from engagement in discussion, sharing information, answering questions and educating. |

| Entertainment Dimension | Commenting is a relaxing, diverting activity. It provides an opportunity to use humor and cope with emotions (which can lead to offensive comments). |

| Social Integrative Dimension | Commenting allows for social interaction via follow-up communication (though interactivity is usually low). |

| Personal Identity Dimension | Individuals are motivated to present their opinions. They enjoy recognition and validation from others. |

| Publication | Leaning (From AllSides.com, as of 2022) | Data Source | Date Published | Total Reader Comments | Total Individual Commenters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Conversation | Ranked ‘Lean Left’ but with low confidence | Altruism in birds? Magpies have outwitted scientists by helping each other remove tracking devices. [8] | 21 February 2022 | 59 | 37 |

| Daily Mail Online | Lean Right | Cheeky magpies help each other remove sophisticated GPS harnesses–ruining a year of scientific work [13] | 22 February 2022 | 121 | 109 |

| Guardian Online | Lean Left | Magpies-courageous-heroes-or-little-feathery-bastards First Dog on the Moon [9] | 25 February 2022 | 500 * | 249 * |

| Opinion | Description |

|---|---|

| Positive | Supportive of use of tags in wildlife research, or in this specific case |

| Not Wholly For or Against | Comment includes points in favor and against |

| Negative | Against tag use, or does not support use of tags in this specific case |

| Irrelevant | Comment does not make a judgment about the use of tags |

| Opinion | Example from the Online Comments |

|---|---|

| Positive | “To be fair, it’s only trying to understand them a bit better and further our knowledge about this fascinating bird. The trackers would have been removed anyway after the experiment.” (Respondent 101) |

| Not wholly for or against | “Thank you…a really interesting article illustrating researcher ethical responses to evidence. You raise important questions for philosophers, scientists and A(nimal) E(xperiment) C(ommittees) about emotion, empathy, altruism and consent in humans and non-humans—bring on the nanotech-trackers!” (Respondent 64) |

| Negative | “It shows that they definitely didn’t like the equipment, which goes against any assurances that such experiments do not harm or cause discomfort to the subjects.” (Respondent 82) |

| Conversation | Daily Mail | Guardian | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total individuals making ‘judgment’ comments | 18 | 30 | 36 |

| Users making ‘judgements’ as % of total users | 49% | 28% | 14% |

| Positive judgment comments | 4 | 3 | 8 |

| Negative judgment comments | 6 | 22 ** | 23 * |

| Judgment comments not wholly for or against | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| Upticks for positive judgment comments | - | 33 | 178 |

| Upticks for negative judgment comments | - | 955 ** | 251 ** |

| Upticks for judgements not wholly for or against | - | 268 | 43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hayward, L. Reader Responses to Online Reporting of Tagged Bird Behavior. Animals 2025, 15, 2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142053

Hayward L. Reader Responses to Online Reporting of Tagged Bird Behavior. Animals. 2025; 15(14):2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142053

Chicago/Turabian StyleHayward, Louise. 2025. "Reader Responses to Online Reporting of Tagged Bird Behavior" Animals 15, no. 14: 2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142053

APA StyleHayward, L. (2025). Reader Responses to Online Reporting of Tagged Bird Behavior. Animals, 15(14), 2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142053