Simple Summary

Sharks and rays are threatened by human activities like fishing and climate change. Many of these species are at risk of extinction. Despite efforts, we still do not know enough about the biology of some species. This lack of information is often correlated to inaccessible habitats, as in the case of the Bramble shark, Echinorhinus brucus, and the Prickly shark, E. cookei, which live in deep oceans. Echinorhinus brucus and E. cookei are the only species of the genus and differ in the shapes and patterns of denticles on their skin. In this study, the data collected demonstrated that E. brucus is present worldwide, except in the Pacific Ocean, where E. cookei lives. Though there are signs of local extinction of the Bramble shark from the North Sea and the western Mediterranean Sea, two areas with a significantly high number of captures of E. brucus are the western Atlantic Ocean and the central Indian Ocean. These areas could be important for conservation plans, especially considering the genetic differences shown between the Bramble shark populations from the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean. The species could include two different taxonomic entities that have not yet been fully detected by scientists.

Abstract

Elasmobranch species show low resilience in relation to anthropogenic stressors such as fishing efforts, loss of habitats, and climate change. In this sense, the elasmobranch populations appear to be at risk of extinction in many cases. Despite conservation researchers making efforts to implement knowledge, the information on the biology, reproduction, distribution, or genetic structure of some species is still scattered, often caused by the occurrence of species in inaccessible habitats. Echinorhinus brucus is a deep benthic shark evaluated as “Endangered” on which little information is available, particularly about its geographical range and genetic structure, while E. cookei is listed as “Data Deficient”. Echinorhinus brucus belongs to the Echinorhinidae family, and its unique congeneric species is E. cookei. The main morphological diagnostic characteristic of both species is the presence of denticles with different shapes and patterns on the derma. In the present paper, mitochondrial COI and NADH2 sequences were retrieved from both E. brucus and E. cookei species, and analyses were conducted by applying different models of phylogenetic inference. Sequences of E. brucus captured in the Indian Ocean (IOS) did not cluster with the Atlantic E. brucus counterparts (AOS) but instead with E. cookei sequences; the different models showed an overlapping tree topology. Concurrently, a review of the historical and recent captures of the two species was carried out. The worldwide distribution of E. brucus excludes the Pacific Ocean area, where E. cookei occurs, and is characterised by presumably current local extinctions in the North Sea and the western Mediterranean Sea. The dataset describes two definite areas of significantly high abundance of E. brucus located in the Atlantic Ocean (Brazil) and the Indian Ocean (India). These areas suggest zones for conservation plans, especially considering the two lineages identified through molecular approaches.

1. Introduction

The IUCN list of endangered and threatened marine species is constantly updated, and new species are being added with increasing fishing pressure and climate change [1]. Despite the efforts of scientists engaged in conservation challenges, knowledge of the status of many species is still lacking [2]. The scarcity of the biology, ethology, reproduction, distribution, or genetics data makes it difficult to assign a correct IUCN risk category and plan interventions for conservation.

Although substantial efforts have been dedicated to the study of elasmobranchs, a notable subset of species within this group remains in need of further investigation: the Bramble shark Echinorhinus brucus (Bonnaterre, 1788) (Echinorhiniformes, Echinorhinidae) is one of these. Regrettably, our understanding of this species is severely constrained, and data about it are not often updated and well arranged; only a few reviews and specimen checklists have been performed during the last decade [3]. Individuals of this species have rarely been fished worldwide in the nineteenth century and captured as bycatch or target species in meat and liver oil fisheries [4]. A source of information on the species is natural history museums or the sighting records collected in different ways [5,6,7].

Echinorhinus brucus is a deep benthic shark (more frequent in the 200–900 m range) [8,9,10] that prefers soft-bottom habitats of the continental slope, but some records also refer to catches in very shallow waters [11,12]. In E. brucus, maturity occurs at 189–231 cm for females and 150–187 for males [11,13,14,15,16]. Its diet consists mainly of crustaceans (69%) and teleosteans (26%), together with cephalopods (1.7%) and elasmobranchs (0.7%) [17]. Its presence is confirmed in a wide geographical area, from the North Atlantic coasts to the South American ones and in the Atlantic coasts of Europe and Africa, extending to the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean [4,10,11,17,18,19,20], though the global distribution seems to be particularly fragmented [21]. A significant reduction in the number of individuals in fisheries bycatch has been recorded in the Mediterranean Sea, and it is assumed that the abundance of this species may suffer a sharp reduction (80–100%) by the end of the century due to depth fishing [21,22]. In particular, the most recent catches (2002–2013) in the Mediterranean Sea were concentrated in the Levantine region [23,24]. As for reproduction, E. brucus is a viviparous species, with 10 and 52 young in a litter [11,25]; the dimensions at birth are between 40 and 55 cm, and no reproductive seasonality has been observed [11].

Echinorhinus brucus belongs to the Echinorhinidae family in addition to their congeneric species, Echinorhinus cookei Pietschmann, 1928, also known as the prickly shark. In both species, their conservation is concerned with bycatch events in bottom trawls and line gear because they are sometimes caught during fisheries of commercial interest products [17,26]. The main diagnostic characteristic between the two species is the morphological pattern of dermal denticles. In E. brucus, the denticles have various sizes, spaced on the body, and some of them fused in groups; on the contrary, in E. cookei denticles are relatively small (less than 5 mm), stellate bases, close together, and with denticles not expanded into large bucklers or thorns [10,27]. Echinorhinus cookei seems to be present up to greater depths (1100 m) [25] and may reach greater maximum dimensions (400 cm). Its distribution seems to be pan-Pacific and in a bordering area of the eastern Indian Ocean, along Australian coasts [15,27]; in the eastern Pacific Ocean, the distribution seems to be continuous, from Oregon (USA) to Chile [28]. Recently, an Atlantic capture presented questionable identification. In 2012, a female was captured in the Caribbean waters of Venezuela, exhibiting a particular pattern of dermal denticles that did not allow a confident identification at the species level due to the shape intermediate between E. brucus and E. cookei [29]. The definitive identification occurred only after molecular analysis attributing the individual to E. brucus [29].

On the whole, the genetic variability of both species has never been deeply investigated; as such, the phylogenetic relationship of E. brucus vs. E. cookei is poorly known. Only a few studies have outlined the Echinorhinus genus genetic pattern, which seemed to show incongruity with actual valid taxonomy [30,31,32].

In the present paper, we extrapolated phylogenetic tree topology from two molecular markers of existing sequences using much more robust evolutionary models to evaluate the congruence with the taxonomy of the genus and presented the worldwide historical and current distribution of the two species using updated literature.

2. Materials and Methods

A first bibliography analysis was conducted to locate and quantify the molecular markers available. The mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (NADH2) and cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) sequences from Echinorinus specimens were downloaded from Bold System [33] and NCBI [34]. BLAST research [35] was conducted using default parameters to verify the taxonomic accuracy. A total of six sequences attributed to E. brucus and seven attributed to E. cookei were found in databases for the COI marker, while five and one sequences were found, respectively, for E. brucus and E. cookei with regard to the NADH2 marker. Though the NADH2 sequences from Sri Lanka were uploaded on Genbank as Echinorhinus sp., as reported by the authors, we verified through pictures of individuals that the morphological features of the samples were consistent with E. brucus [32]. Similarly, the NADH2 sequence of an individual from Oman was allocated by authors as E. brucus species, according to its morphology [30,31,36]. Three sequences of Pristiophorus cirratus (Latham, 1974) and one sequence of Squalus crassispinus Last, Edmunds & Yearsley, 2007, were used as outgroups, respectively, for COI and NADH2 analysis. Sequences were handled on BioEdit and aligned with ClustalW multiple alignment options using default parameters [37]. A complete genome sequence of E. cookei was used in both NADH2 and COI analysis; it was aligned in both databases and cut with a length of a 670 base pair for COI and 1047 bp for NADH2.

Phylogenetic Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) analyses were conducted to search for coherence among trees for both molecular markers.

The ML analyses were conducted for both markers on IQ3 online portal [38] using default settings. Two ML analyses for each marker were carried out, one for nucleotide sequences and one for amino acid sequences. The amino acids dataset was created by translating the sequences of NADH2 on MEGA version 11 [39] using the alignment session and the Vertebrate Mitochondrial Genetic Code.

All Bayesian Inference analyses were conducted only for COI marker on CIPRES Science Gateway [40] using Beast2 2.6.6; the input files for all analyses were handled using BEAUTi2 2.6.0 [41,42].

Three different Bayesian Inference analyses were performed to see if differences were presented in the tree topologies between three different models. In all analyses, the substitution rate found by Martin et al. [43] and Dudgedon et al. [44] was used for the calibration of the tree. The HKY model was chosen as the best result from ML autodetected output. Settings were as follows: HKY gamma 4 model, normal relaxed clock log, clock rate, 0.07 × 10−8 substitution per year, and 100,000.000 generations, sampled every 10,000 for Birth and Death model, Yule model, and Coalescent model.

The p-distance of COI was calculated in MEGA version 11 [39] using the Gamma Distributed Rates among Site and Gamma parameter 4.00, and results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

COI p-distance of E. brucus and E. cookei sequences; the great difference in the three major groups is notable (IOS E. brucus, AOS E. brucus, and E. cookei).

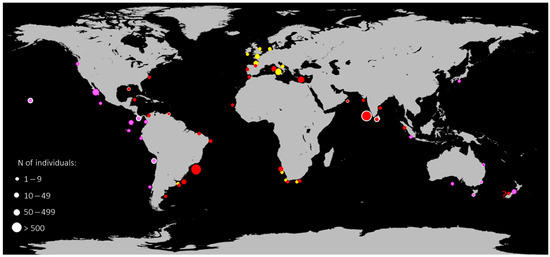

Regarding the distribution dataset, a deep bibliographic review was conducted analysing all bycatches events, museum specimens [6], results of projects [45], and any sighting already published for both E. brucus and E. cookei species [16,17,19,23,26,28,29,30,31,32,36,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]; all data are grouped in old captures (before 1930) and recent captures (after 1930), listed in Table 2, and displayed in a world map (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Echinorhinus brucus and E. cookei specimens captured or sighted, ordered by years from past to present. Marine area, locality, number of individuals, and reference, NCBI Accession Number (A.N.) or Bold System code, are included. The total dataset is shown in Figure 1, except for samples for which geographical information was not available (NA).

Figure 1.

Map of distribution of E. brucus and E. cookei extrapolated from captures and sightings; data are listed in detail in Table 2. Yellow dots indicate E. brucus specimens before 1930; red dots E. brucus specimens from 1930 to present; purple dots specimens of E. cookei. The dot dimension indicates the range of the number of individuals observed in a specific area. Dots circled with white lines indicate the areas from where molecular data have been used in the present study. The dot with “?” indicates dubious sightings of two E. brucus individuals in New Zealand waters [61].

3. Results

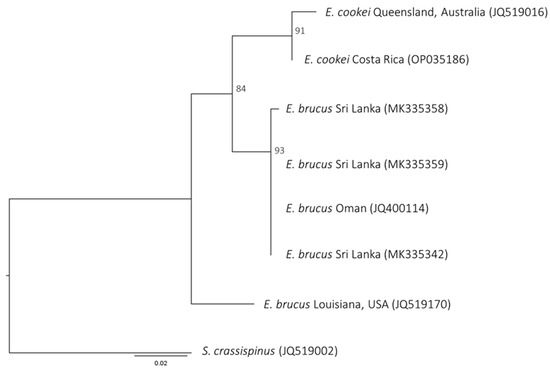

The COI and NADH2 nucleotides and NADH2 amino acid sequences results from Maximum Likelihood (ML) analyses showed the same tree topology. In the phylogenetic trees of both markers, E. brucus sequences show a non-monophyletic topology. The Indian Ocean Sequences (IOS) of E. brucus (i.e., samples from Indian and Oman coasts for COI and Sri Lanka and Oman coasts for NADH2) did not cluster with the Atlantic Ocean Sequences (AOS) (i.e., samples from Venezuelan and USA coasts for COI and USA coasts for NADH2) but discriminated into two different lineages. The Indian (IOS) lineage resulted in being a sister group of E. cookei. Only the amino acid ML tree for NADH2 showed a significative bootstrap value at the node of splitting IOS E. brucus and E. cookei (shown in Figure 2). For this node, the bootstrap value was 60 in the COI nucleotide ML tree (tree not shown). No evolutionary signal was present in the COI amino acid result.

Figure 2.

Maximum Likelihood tree based on NADH2 amino acid sequences; all nodes show significant bootstrap values.

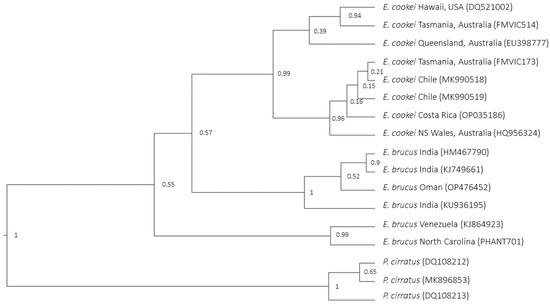

All COI trees built with BI (Bayesian Inference) analysis showed the same topology of ML trees, but in this case, all of them showed weak nodes between IOS E. brucus and E. cookei, ranging in a posterior value of 50–57 (the Bayesian tree using the Yule model is shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Bayesian analysis tree using Yule model for COI marker. The node that delineates the cluster of IOS E. brucus + E. cookei exhibits a low posterior value, as does the innermost node clustering the AOS E. brucus. On the contrary, the nodes at the root of the three separate lineages (respectively, AOS E. brucus, IOS E. brucus, and E. cookei) show a very high posterior value.

It is noteworthy to highlight that the nodes at the root of each of the three major lineages (AOS E. brucus–IOS E. brucus–E. cookei) were highly significative (99–100) in all the trees, a sign that these lineages are well differentiated from each other (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

The COI pattern for E. cookei (Figure 3), which included a higher number of sequences than the NADH analysis, showed that haplotypes were divided into two subgroups. This was not consistent with a geographical outline. In fact, the sequences from Australia did not cluster together. The two specimens from Tasmania and Queensland were separated from two sequences from New South Wales and Tasmania.

The p-distance ranges between 0.0368 and 0.0449 when comparing individuals from the three major groups and is around 10 times greater than the internal difference of the groups (0.000–0.0077) (Table 1).

The global geographical distribution of E. brucus and E. cookei, extrapolated from captures and sightings reported in the literature, is presented in Table 2 and Figure 1. The map of distribution discriminates specimens that were found before 1930 and from 1930 to the present, as well as the range of the number of individuals observed in a specific area. The total number of specimens herein listed is 8903 for E. brucus and 301 for E. cookei, respectively, with an average number of 37 (E. brucus) and 5 (E. cookei) specimens per locality in a period comprising 1680 to 2022 (E. brucus) and 1956 to 2022 (E. cookei).

4. Discussion

In the present paper, different models of phylogenetic inference, applied to mitochondrial sequences, described a pattern where E. brucus from the Indian Ocean (IOS) did not cluster with the Atlantic E. brucus lineage (AOS), but instead clustered with E. cookei sequences.

Although the results could be affected by the small number of data, our analyses support the taxonomic criticisms within the genus that have already been noticed by other authors [29,30,31,32,69]. In particular, Fernando et al. [32] and Naylor et al. [31] exhibited the same topology of the present trees using different methodologies. The first authors used the Neighbor-Joining method with the uncorrected p-distance model, and the second used a Bayesian approach using the GTR+I+Γ model, both using NADH2 as a marker.

The COI is usually a good marker for species and subspecies delimitation because of its peculiarity to be a fast mutational rate gene [74,75]; nevertheless, the mutational rate of NADH2 in Echinorhinus sharks seems to be even faster than COI in the first position of the codon. This leads to a higher incidence of mutations in the amino acid sequences compared to COI, where a greater prevalence of silent mutations is generally observed [30,31,76,77].

The great phylogenetic distance (Table 1) shown in the trees between the two E. brucus lineages, confirmed by both molecular markers, may be explained as a probable separation due to distance or barriers to gene flow between the two main clusters (IOS vs. AOS). In fact, E. brucus is widespread; in the Atlantic Ocean, some records occur at high latitudes (Virginian coasts and the North Sea) and along the coast of Chubut in Argentina and South Africa [6,12,46,50], and presumably in almost all of the Indian Ocean (Figure 1, Table 2). Similar patterns are observable for other elasmobranchs widely distributed, where distal populations have been demonstrated to be genetically heterogeneous [78].

The dataset of Table 2 and the distribution map (Figure 1) show two main areas of aggregations, detected by the highest values of captures (thousands of individuals) in Brazilian and Indian waters. The two areas are congruent with the separation of the two lineages and should be carefully investigated. There is no evidence of the presence of E. brucus in the Pacific Ocean, corroborated by the sole presence of E. cookei (Table 2). The highest number of records for E. cookei occurs from northern California to Costa Rica, Chile, and Cocos Island, where, despite the inaccessibility of the species’ habitats, some direct sightings occurred during submersible missions [54,63]. The latter are the only sightings of living animals in their habitat for the Echinorhinus genus. The capture of an E. cookei individual in Indonesia (Figure 1; Table 2) is the westernmost point for this species; this is the unique specimen from the Indian Ocean and the only record of an overlapping area between the two species’ ranges [65].

Molecular results for E. cookei (Figure 3) show that individuals from Australia do not cluster together. The two Australian specimens, from Tasmania and Queensland, are strictly grouped with the one from Hawaii. The other two, from New South Wales and Tasmania, cluster with individuals from Chile and Costa Rica. The actual knowledge of the reproductive strategies of E. cookei is insufficient to assert any consideration, but this could serve as a stimulus for new studies; the possible dispersal behaviour of this species, old biogeographical relations, or presence of independent mutations may have affected the population or the results.

Regarding E. brucus, hotspots of bycatch occurrences can be assumed to be in the presence of upwelling events where aggregation phenomena have occurred in the same localities over the years [51]. A similar pattern is also observed in E. cookei [26,54,63] (Table 2). On the contrary, E. brucus is now rarely fished in some regions. Although the dataset of the distribution (Table 2, Figure 1) shows regions where the captures reach very high abundance for both species, a new report highlights how Indian E. brucus populations suffer from excessive fishing pressure due to the high demand for liver oil, which caused a reduction in landings in the last 10 years [4]. Extensive studies are needed to program and manage any kind of conservation action because, as we have shown, reproductive isolation occurs within the species, and it has not yet been fully researched.

5. Conclusions

Echinorhinus brucus and E. cookei remain poorly known and enigmatic species.

A great divergence between E. brucus Indian (IOS) lineage and E. brucus Atlantic (AOS) lineage was confirmed by our analyses, conducted with different methodologies (Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference). The two lineages were further shown to be paraphyletic. Thus, a precautional revision of the species and the genus needs, at least, subspecies identification and correct information in support of conservation plans. In order to better reconstruct the unclear taxonomy of E. brucus and E. cookei, a morphological and genetic revision on ancient and modern specimens should be carried out.

Individuals of Echinorhinus genus are now rarely fished in some regions of the world, except in some areas where they contribute significantly to the overall biomass as bycatch product to be handled. E. brucus disappeared from the western Mediterranean Sea and North Sea, while it is very abundant in the Indian Ocean and Southwestern Atlantic Ocean. E. cookei’s distributional ancient data do not exist, and a comparative analysis between present and past abundance is partial or unworkable. In any case, for both species, some regions present a significant number of records. Extensive studies are thus needed to program and manage any kind of conservation action, placing particular attention on the abundance zones for their relevance. From this point of view, the deep genetic divergence within E. brucus and the evolutive relation with the congeneric E. cookei, yet to be clarified, should be used to set a baseline for future actions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.B. and F.S.; methodology, M.B.; formal analysis, M.B.; resources, F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, S.L.B. and F.S.; funding acquisition, S.L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the NBFC to the University of Palermo, funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, PNRR, Missione 4 Componente 2, “Dalla ricerca all’impresa”, Investimento 1.4, Project CN00000033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as the analyses performed did not involve animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Predragovic, M.; Cvitanovic, C.; Karcher, D.B.; Tietbohl, M.D.; Sumaila, U.R.; e Costa, B.H. A Systematic Literature Review of Climate Change Research on Europe’s Threatened Commercial Fish Species. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 242, 106719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serena, F.; Abella, A.J.; Bargnesi, F.; Barone, M.; Colloca, F.; Ferretti, F.; Moro, S. Species Diversity, Taxonomy and Distribution of Chondrichthyes in the Mediterranean and Black Sea. Eur. Zool. J. 2020, 87, 497–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucci, B.; Pacoureau, N.; Rigby, C.L.; Matsushiba, J.H.; Faure-Beaulieu, N.; Sherman, C.S.; VanderWright, W.J.; Jabado, R.W.; Charvet, P.; Mejía-Falla, P.A.; et al. Fishing for Oil and Meat Drives Irreversible Defaunation of Deepwater Sharks and Rays. Science 2024, 383, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, F.; Morey Verd, G.; Seret, B.; Sulić Šprem, J.; Micheli, F. Falling through the Cracks: The Fading History of a Large Iconic Predator. Fish Fish. 2016, 17, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollen, F.H.; Iglésias, S.P. An Inventory of Bramble Sharks Echinorhinus brucus (Bonnaterre, 1788) (Elasmobranchii, Echinorhinidae) in Natural History Collections Worldwide for Conservation Status Assessment. Zoosystema 2023, 45, 653–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiralongo, F.; Badalamenti, R.; Arizza, V.; Prieto, L.; Lo Brutto, S. The Portuguese Man-of-War Has Always Entered the Mediterranean Sea—Strandings, Sightings, and Museum Collections. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 856979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, G.; Carpenter, K.E.; Roux, J.-P.; Molloy, F.J.; Boyer, D.; Boyer, H.J. FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes. Field Guide to the Living Marine Resources of Namibia; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, J.I.; Woodley, C.M.; Brudek, R.L. A Preliminary Evaluation of the Status of Shark Species; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1999; Volume 380. [Google Scholar]

- Serena, F. Field Identification Guide to the Sharks and Rays of the Mediterranean and Black Sea. In FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, D.A.; Wintner, S.P.; Kyne, P.M. An Annotated Checklist of the Chondrichthyans of South Africa. Zootaxa 2021, 4947, 1–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemstra, P.C.; Heemstra, E.; Ebert, D.; Holleman, W. Coastal Fishes of the Western Indian Ocean; Randall, J.E., Ed.; South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2022; Volume 1, ISBN 978-1-998950-41-46. [Google Scholar]

- Compagno, L.J.V. FAO Species Catalogue; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1984; Volume 4, pp. 1–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sanches, J.G. Catálogo dos Principais Peixes Marinhos da República de Guiné-Bissau; Instituto Nacional de Investigacao das Pescas: Lisbon, Portugal, 1991; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Last, P.R.; Stevens, J.D. Sharks and Rays of Australia; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Akhilesh, K.V.; Chellappan, A.; Bineesh, K.K.; Ganga, U.; Pillai, N.G.K. Demographics of a Heavily Exploited Deep Water Shark Echinorhinus cf. brucus (Bonnaterre, 1788) from the south-eastern Arabian Sea. Indian J. Fish. 2020, 67, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Akhilesh, K.V.; Bineesh, K.K.; White, W.T.; Shanis, C.P.R.; Hashim, M.; Ganga, U.; Pillai, N.G.K. Catch Composition, Reproductive Biology and Diet of the Bramble Shark Echinorhinus brucus (Squaliformes: Echinorhinidae) from the South-eastern Arabian Sea. J. Fish Biol. 2013, 83, 1112–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, A.J.; Compagno, L.J.V. Families Echinorhinidae, Proscylliidae, Scyliorhinidae. In Smiths’ Sea Fishes; Macmillian: Johannesburg, South Africa, 1986; Volume 63. [Google Scholar]

- Soldo, A.; Bakiu, R. Checklist of marine fishes of Albania. Acta Adriat. 2021, 62, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikliras, A.C.; Dimarchopoulou, D. Filling in Knowledge Gaps: Length–Weight Relations of 46 Uncommon Sharks and Rays (Elasmobranchii) in the Mediterranean Sea. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 2021, 51, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucci, B.; Bineesh, K.K.; Cheok, J.; Cotton, C.F.; Kulka, D.W.; Neat, F.C.; Pacoureau, N.; Rigby, C.L.; Tanaka, S.; Walker, T.I. Echinorhinus brucus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T41801A2956075; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldo, A.; Lipej, L. An Annotated Checklist and the Conservation Status of Chondrichthyans in the Adriatic. Fishes 2022, 7, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabasakal, H.; Bilecenoglu, M. Not Disappeared, Just Rare! Status of the Bramble Shark, Echinorhinus brucus (Elasmobranchii: Echinorhinidae) in the Seas of Turkey. Ann. Ser. Hist. Nat. 2014, 24, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Kabasakal, H.; Uzer, U.; Karakulak, F.S. Occurrence of Deep-Sea Squaliform Sharks, Echinorhinus brucus (Echinorhinidae) and Centrophorus uyato (Centrophoridae), in Marmara Shelf Waters. Ann. Ser. Hist. Nat. 2023, 33, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, G.; Francis, M. Sharks and Rays of New Zealand; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, J.A.A.; Wahrlich, R. A Bycatch Assessment of the Gillnet Monkfish Lophius gastrophysus Fishery off Southern Brazil. Fish. Res. 2005, 72, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagno, L.J.V.; Niem, V.H. Echinorhinidae. Bramble Sharks. In FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes. The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. Volume 2. Cephalopods, Crustaceans, Holothurians and Sharks; Carpenter, K.E., Niem, V.H., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998; pp. 1211–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Navia, A.F.; Tobón-López, A.; Segura, C.E.; Córdoba, D.F.; Amariles, D.F.; Caicedo, J.A.; Mejía-Falla, P.A. Confirmación de la presencia y distribución latitudinal de Echinorhinus cookei en la zona costera del Pacífico Oriental Tropical. Boletín Investig. Mar. Costeras 2023, 52, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariña, Á.; Quinteiro, J.; Rey-Méndez, M. First Record for the Caribbean Sea of the Shark Echinorhinus brucus Captured in Venezuelan Waters. JO Mar. Biodivers. Rec. ER 2014, 7, e91. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, G.J.; Caira, J.N.; Jensen, K.; Rosana, K.A.M.; White, W.T.; Last, P.R. A DNA Sequence–Based Approach to the Identification of Shark and Ray Species and Its Implications for Global Elasmobranch Diversity and Parasitology. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2012, 2012, 1–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, G.J.; Caira, J.N.; Jensen, K.; Rosana, K.A.; Straube, N.; Lakner, C. Elasmobranch Phylogeny: A Mitochondrial Estimate Based on 595 Species. Biol. Sharks Their Relat. 2012, 2, 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando, D.; Bown, R.M.; Tanna, A.; Gobiraj, R.; Ralicki, H.; Jockusch, E.L.; Caira, J.N. New Insights into the Identities of the Elasmobranch Fauna of Sri Lanka. Zootaxa 2019, 4585, 201–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System (http://www.Barcodinglife.Org). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, D.A.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Lipman, D.J.; Ostell, J.; Wheeler, D.L. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Schwartz, S.; Wagner, L.; Miller, W. A Greedy Algorithm for Aligning DNA Sequences. J. Comput. Biol. 2000, 7, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straube, N.; Iglésias, S.P.; Sellos, D.Y.; Kriwet, J.; Schliewen, U.K. Molecular phylogeny and node time estimation of bioluminescent lantern sharks (Elasmobranchii: Etmopteridae). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2010, 56, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, T.A. Bioedit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Trifinopoulos, J.; Nguyen, L.T.; Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. W-IQ-TREE: A Fast Online Phylogenetic Tool for Maximum Likelihood Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for Inference of Large Phylogenetic Trees. In Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), New Orleans, LA, USA, 14 November 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchard, M.A.; Rambaut, A. Many-Core Algorithms for Statistical Phylogenetics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.P.; Naylor, G.J.; Palumbi, S.R. Rates of Mitochondrial DNA Evolution in Sharks Are Slow Compared with Mammals. Nature 1992, 357, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, C.L.; Blower, D.C.; Broderick, D.; Giles, J.L.; Holmes, B.J.; Kashiwagi, T.; Ovenden, J.R. A Review of the Application of Molecular Genetics for Fisheries Management and Conservation of Sharks and Rays. J. Fish Biol. 2012, 80, 1789–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancusi, C.; Baino, R.; Fortuna, C.; Sola, L.; Morey, G.; Bradai, M.N.; Kallianotis, A.; Soldo, A.; Hemida, F.; Saad, A.; et al. MEDLEM database, a data collection on large Elasmobranchs in the Mediterranean and Black seas. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2020, 21, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musick, J.A.; McEachran, J.D. The squaloid shark Echinorhinus brucus off Virginia. Copeia 1969, 1, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure-Beaulieu, N.; Lombard, A.T.; Olbers, J.; Goodall, V.; Silva, C.; Daly, R.; Harris, J. A Systematic Conservation Plan Identifying Critical Areas for Improved Chondrichthyan Protection in South Africa. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 284, 110163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, T.S.; Rajapackiam, S.; Mohamad Kasim, H.; Ameer Hamsa, K.M.S. On the Landing of Bramble Shark (Echinorhinus brucus) at Tuticorin. Mar. Fish. Inf. Serv. Tech. Ext. Ser. 1993, 121, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, F.J. A North Carolina Capture of the Bramble Shark, Echinorhinus brucus, Family Echinorhinidae, the Fourth in the Western Atlantic. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 1993, 109, 158–162. [Google Scholar]

- Caille, G.; Olsen, E.K. A bramble shark, Echinorhinus brucus, caught near the Patagonian coast. Argent. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2000, 35, 117–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ehemann, N.R.; Zambrano-Vizquel, L.A. Echinorhinus brucus (Bonnaterre, 1788) in the Caribbean Sea: A Recurrent Visitor, or Are the Artisanal Fisheries Exploiting Deeper Waters? J. Fish Biol. 2023, 104, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santander-Neto, J.; Rincon, G.; Jucá-Queiroz, B.; Cruz, V.; Lessa, R. Distribution and New Records of the Bluntnose Sixgill Shark, Hexanchus griseus (Hexanchiformes: Hexanchidae), from the Tropical Southwestern Atlantic. Animals 2022, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemida, F.; Capapé, C. Observations on a Female Bramble Shark, Echinorhinus brucus (Bonnaterre, 1788) (Chondrichthyes: Echinorhinidae), caught off the Algerian coast (southern Mediterranean). Acta Adriat. 2002, 43, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Long, D.J.; McCosker, J.E.; Blum, S.; Klapfer, A. Tropical Eastern Pacific Records of the Prickly Shark, Echinorhinus cookei (Chondrichthyes: Echinorhinidae). Pac. Sci. 2011, 65, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chavez-Ramos, H.; Castro Aguirre, J.L. Notas y observaciones sobre la presencia de Echinorhinus cookei Pietschmann, 1928, en el Golfo de California, Mexico [tiburon]. In Anales de la Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biologicas; Secretaria de Educación Publica, Instituto Politecnico Nacional: Mexico City, Mexico, 1975; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Alvares-León, R.; Castro-Aguirre, J.L. Notas sobre la captura incidental de dos especies de tiburón en las costas de Mazatlán (Sinaloa) México. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna Environ. 1983, 18, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Campos, G.; Castro-Aguirre, J.L.; Balart, E.F.; Campos-Dávila, L.; Vélez-Marín, R. New Specimens and Records of Chondrichthyan Fishes (Vertebrata: Chondrichthyes) off the Mexican Pacific Coast. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2010, 81, 363–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, G.; Powers, D.A. Molecular Phylogeny of the Prickly Shark, Echinorhinus cookei, Based on a Nuclear (18S rRna) and a Mitochondrial (Cytochrome b) Gene. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 1992, 1, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galván-Magaña, F.; Abitia-Cárdenas, L.A.; Rodríguez-Romero, J.; Perez-España, H.; Chávez-Ramos, H. Systematic List of the Fishes from Cerralvo Island, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Cienc. Mar. 1996, 22, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, H.; Madrid, V.J.; Virgen, J.A. Presence of Echinorhinus cookei off Central Pacific Mexico. J. Fish Biol. 2002, 61, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, M. Geographic Distribution of Commercial Catches of Cartilaginous Fishes in New Zealand Waters, 2008–2013; Ministry for Primary Industries: Wellington, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bertozzi, T.; Lee, M.S.; Donnellan, S.C. Stingray diversification across the end-Cretaceous extinctions. Mem. Mus. Vic. 2016, 74, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessudo, S.; Ladino, F.; Becerril-García, E.E.; Shepard, C.M.; Salinas-De-León, P.; Hoyos-Padilla, E.M. The Elasmobranchs of Malpelo Flora and Fauna Sanctuary, Colombia. J. Fish Biol. 2021, 99, 1769–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Vásquez, J.I.; Anislado-Tolentino, V.; Escárcega-Miranda, B. New Record of the Prickly Shark Echinorhinus cookei (Pietschmann, 1928) and Evidence of Scavenging by the Coyote Canis latrans (Say, 1823) in Bahia de Los Angeles. Aquat. Res. 2023, 6, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmi. Additional Records of Genus Echinorhinus (Echinorhiniformes: Echinorhinidae) from Indonesia with Notes on the Species Distribution in the Indian Ocean. J. Ichthyol. 2022, 62, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral Flores, L.F.; Morrone, J.; Alcocer, J.; Espinosa, H.; Pérez-Ponce de León, G. Lista patrón de los tiburones, rayas y quimeras (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii, Holocephali) de México. Arx. Miscel-Lània Zoològica 2015, 13, 47–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez, E.M.; Garayzar, C.J.V. Four Sharks and a Ray from the Northwest Coast of Mexico. Rev. Biol. Trop. 1998, 46, 465–467. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, R.D.; Holmes, B.H.; White, W.T.; Last, P.R. DNA Barcoding Australasian Chondrichthyans: Results and Potential Uses in Conservation. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2008, 59, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ávila, J.R.; Al-Jufaili, S.; Álvarez-Pliego, N.; Saldierna-Martínez, R.J. Encountering the Morphological and Molecular Complexity in the Bramble Shark Echinorhinus cf. E. brucus (Bonnaterre 1788) from the Oman Sea. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. 2023, 103, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shajibi, S.R.; Chesalin, M.; Al-Shagaa, G.A. New Records of Sharks from Southern Coastal Waters of Oman in the Arabian Sea. Pak. J. Zool. 2014, 46, 281–284. [Google Scholar]

- Moazzam, M.; Osmany, H.B. Species composition, commercial landings, distribution and some aspects of biology of shark (class Pisces: Subclass: Elasmobranchii: Infraclass: Selachii) from Pakistan: Taxonomic analysis. Int. J. Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 18, 567–632. [Google Scholar]

- Sreedhar, U.; Sudhakar, G.V.S.; Kumari, M. Deep sea fish catch from 16 stations off southeast coast of India. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. India 2007, 49, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Anguila, R.; Nieto-Alvarado, L.E.; Hernández-Beracasa, L. Nuevos registros de peces de esqueleto cartilaginoso para el Caribe colombiano y uno como ampliación de su distribución geográfica en el Caribe colombiano para Bocas de Ceniza, departamento de Atlántico, Colombia. Boletín Investig. Mar. Costeras-INVEMAR 2016, 45, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Lemey, P. Assessing Substitution Saturation with DAMBE. In The Phylogenetic Handbook: A Practical Approach to DNA and Protein Phylogeny; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 615–630. [Google Scholar]

- Cariani, A.; Messinetti, S.; Ferrari, A.; Arculeo, M.; Bonello, J.J.; Bonnici, L.; Cannas, R.; Carbonara, P.; Cau, A.; Chari-laou, C.; et al. Improving the Conservation of Mediterranean Chondrichthyans: The ELASMOMED DNA Barcode Reference Library. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton, R.E.; Reneau, P.C. Spatial Covariation of Mutation and Nonsynonymous Substitution Rates in Vertebrate Mitochondrial Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006, 23, 1516–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.B.; White, W.T.; Ward, R.D.; Naylor, G.J.; Peirce, R. Rediscovery and Redescription of the Smoothtooth Blacktip Shark, Carcharhinus Leiodon (Carcharhinidae), from Kuwait, with Notes on Its Possible Conservation Status. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2011, 62, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, R.; Vacca, L.; Cariani, A.; Carugati, L.; Cau, A.; Charilaou, C.; Crescenzo, S.; Ferrari, A.; Follesa, M.C.; Hemida, F.; et al. Commercial Sharks under Scrutiny: Baseline Genetic Distinctiveness Supports Structured Populations of Small-Spotted Catsharks in the Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1050055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).