Household Rituals and Merchant Caravanners: The Phenomenon of Early Bronze Age Donkey Burials from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cult, Symbols, and Ritual in Archaeology

3. The EB of the Southern Levant

4. The Ritual Landscape of the EB Southern Levant

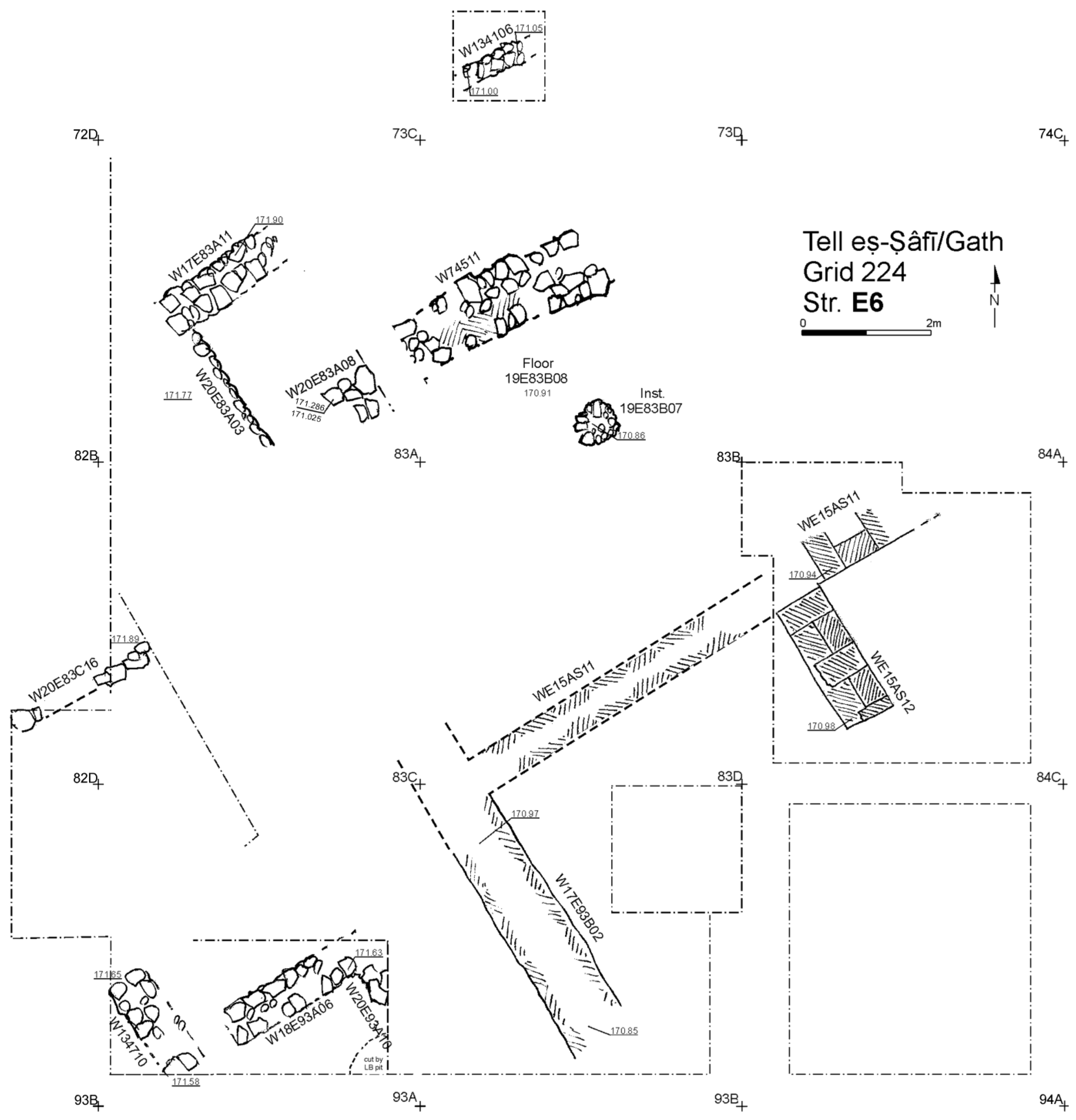

5. Material—The EB at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath

6. Materials and Results—Evidence for Ritual in the EB at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath

6.1. Architecture as Evidence for Ritual

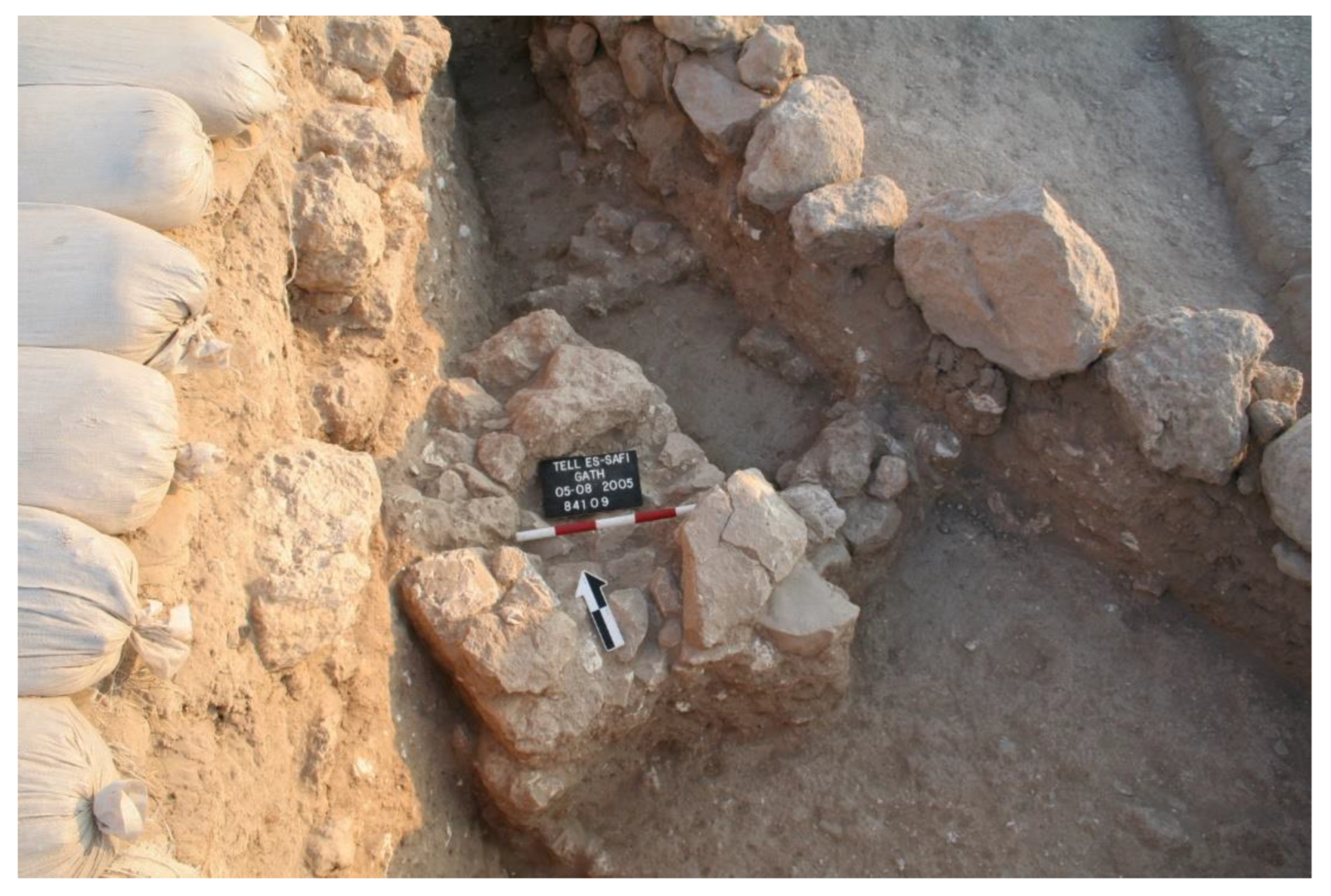

6.2. Installations and Platforms as Evidence for Ritual

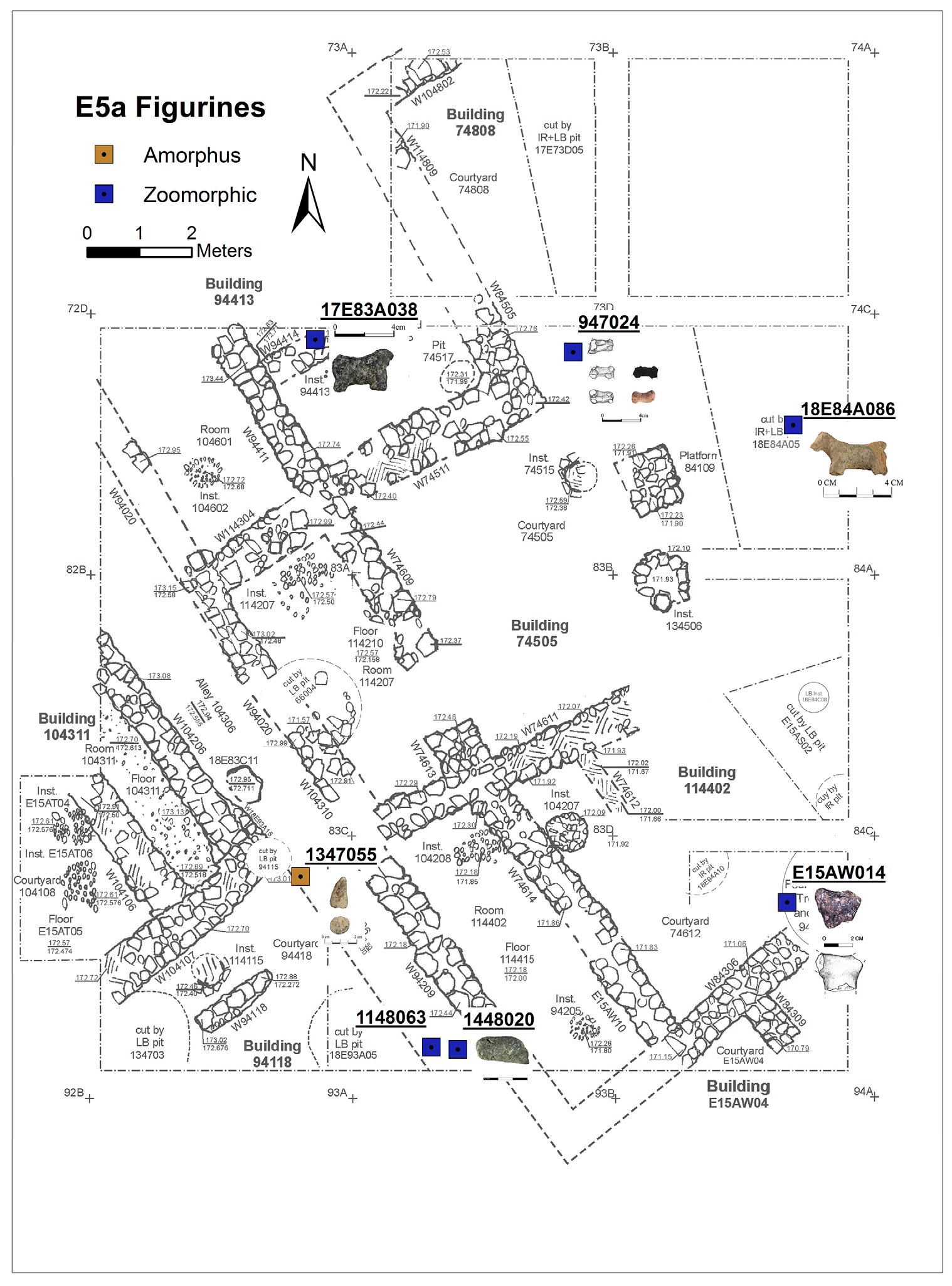

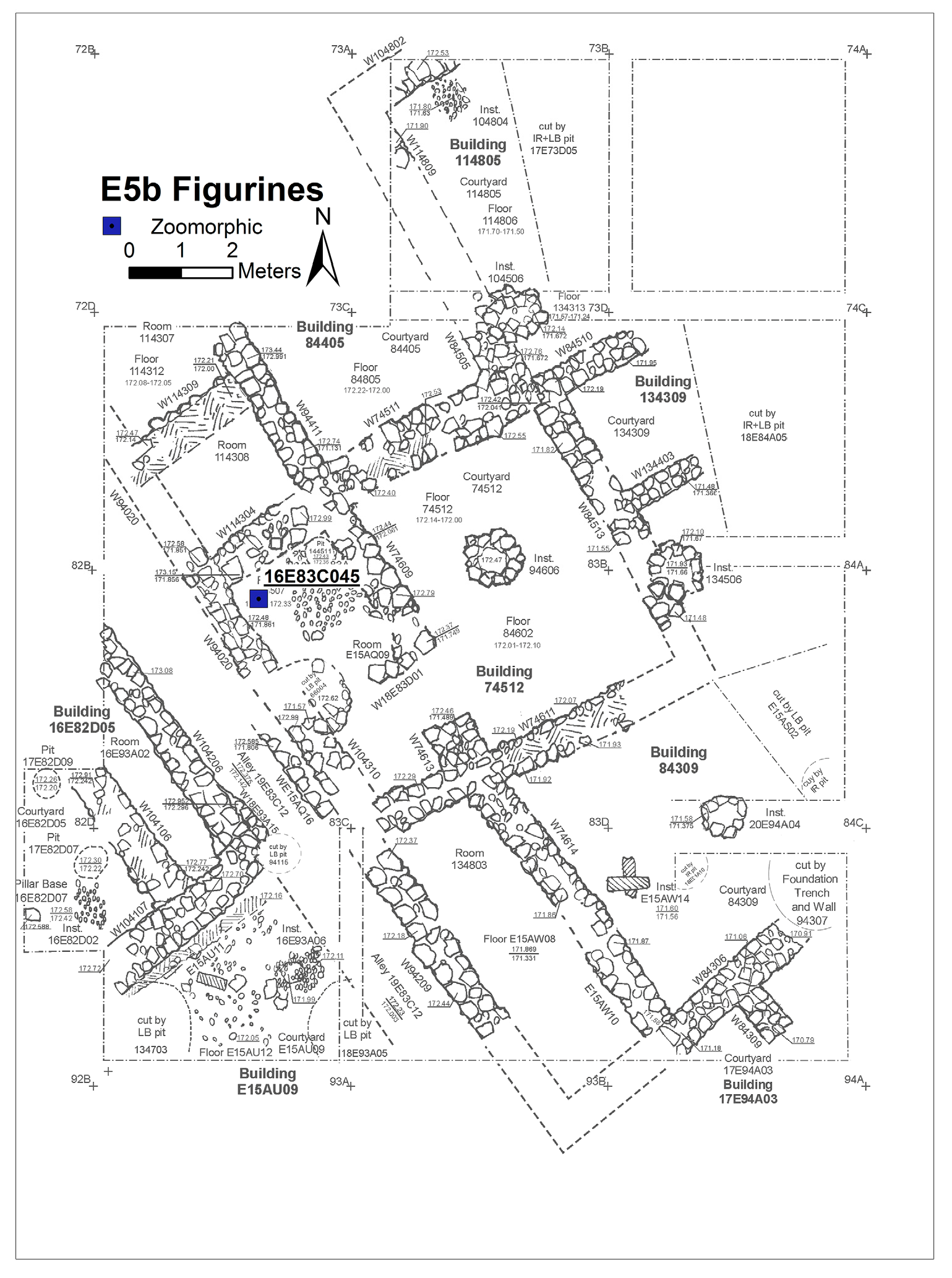

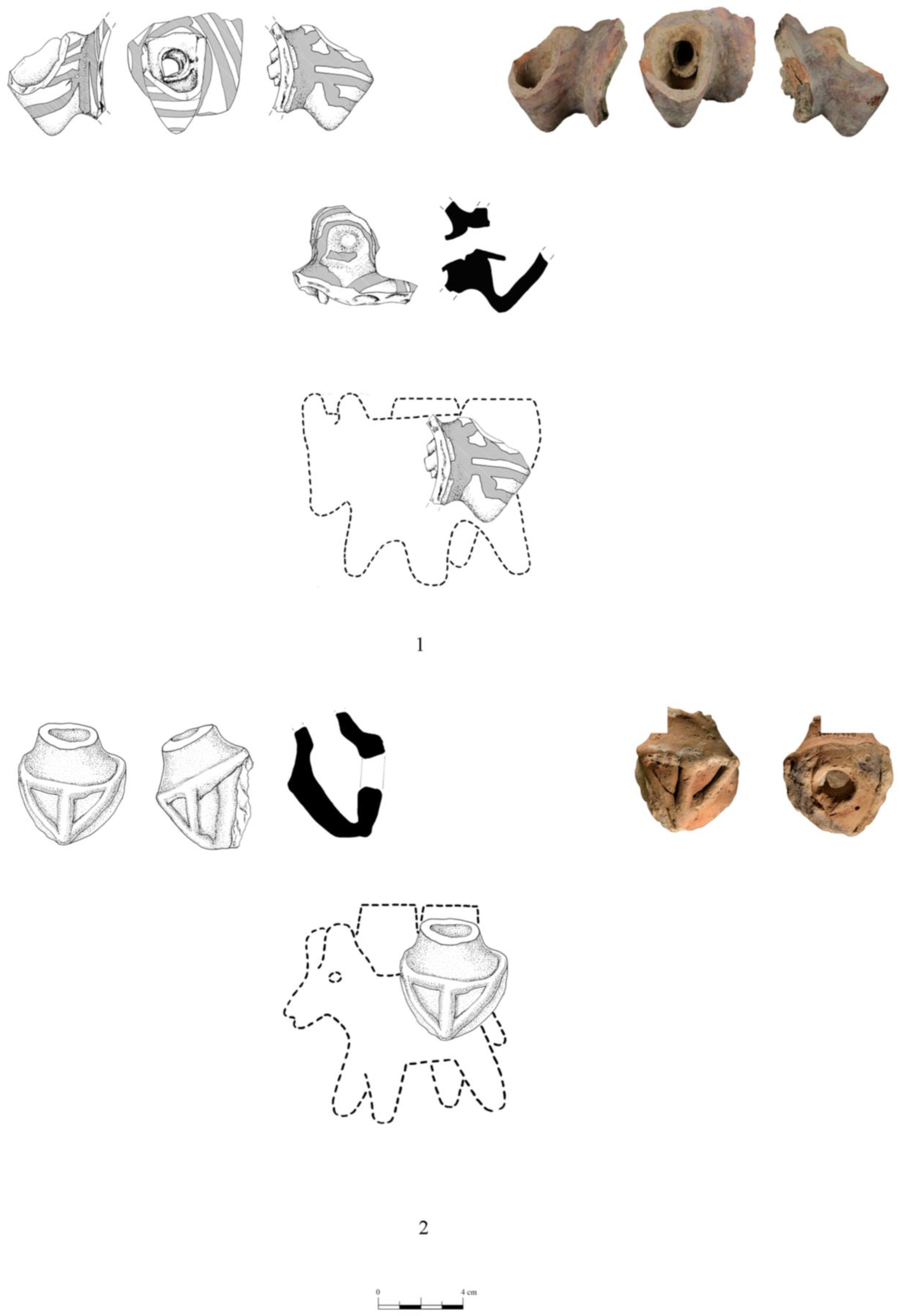

6.3. Figurines as Evidence for Ritual

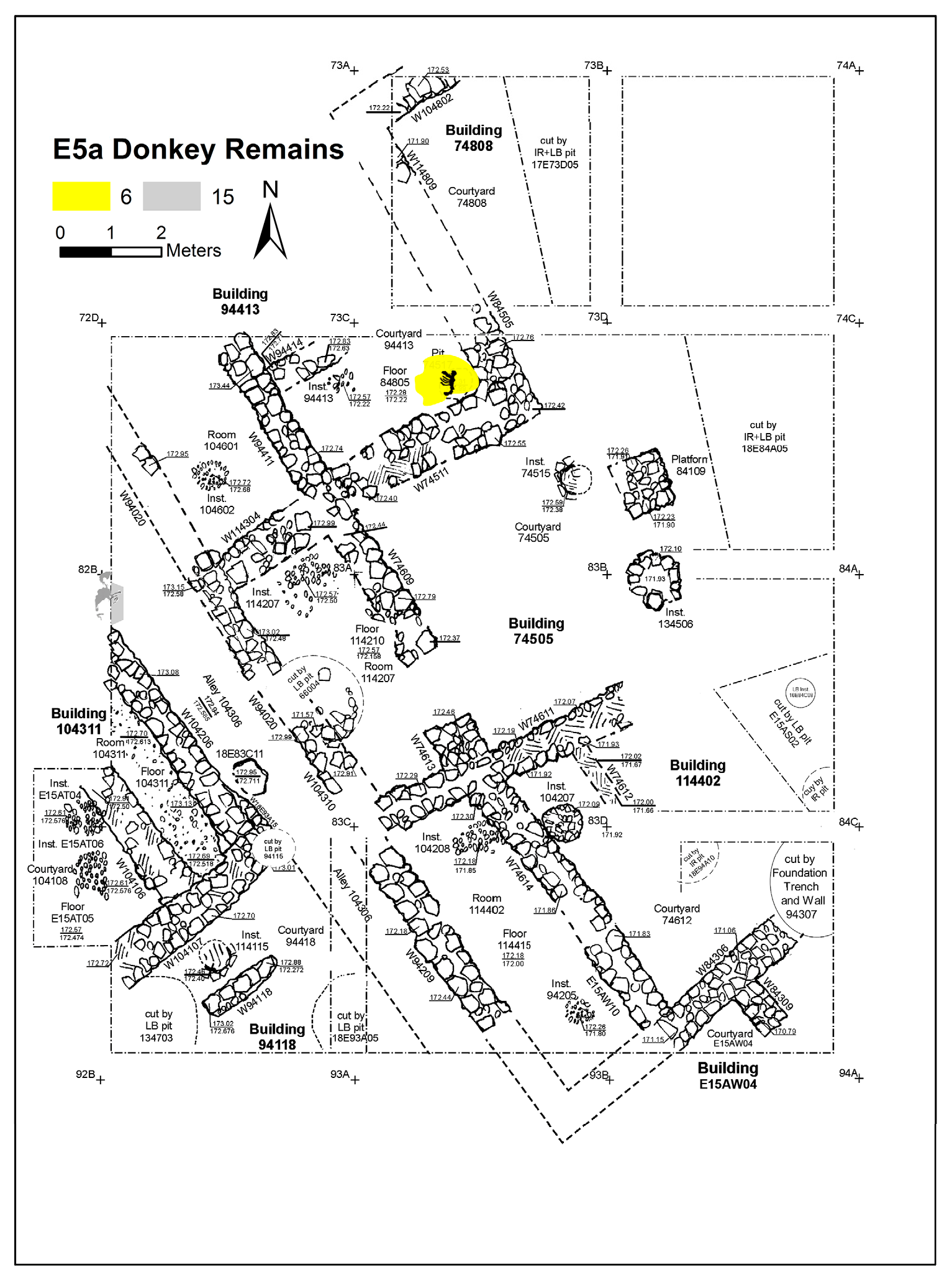

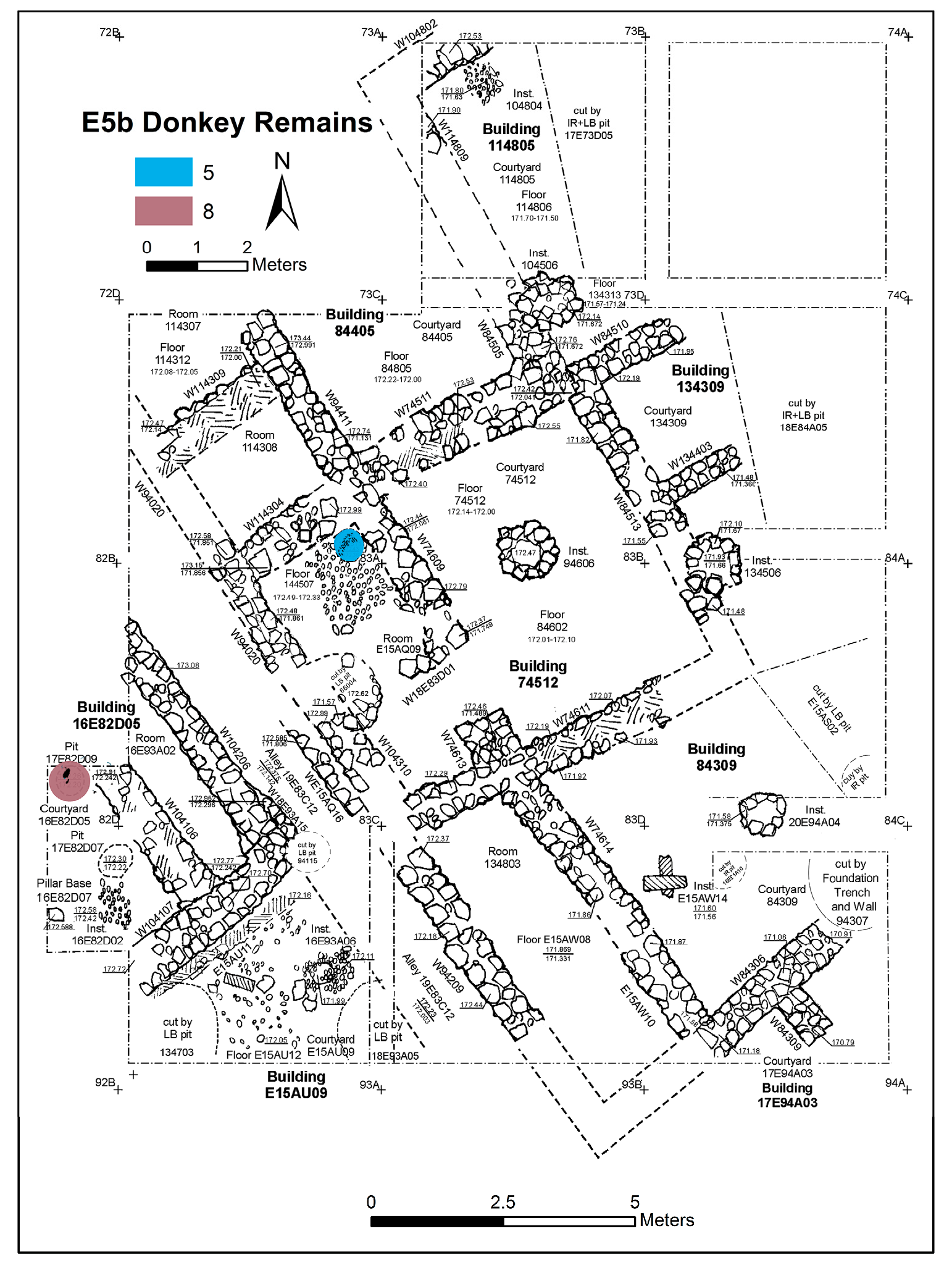

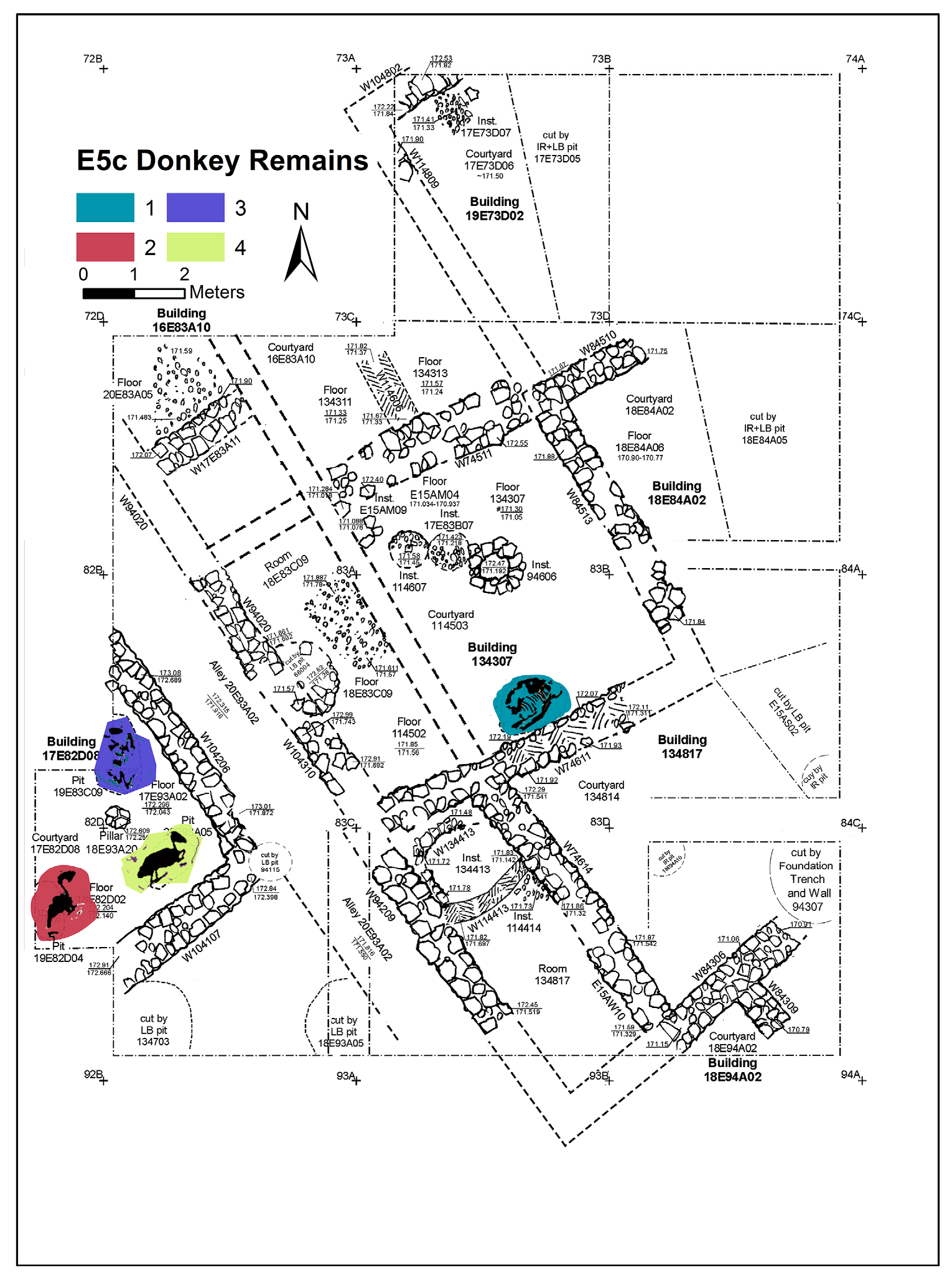

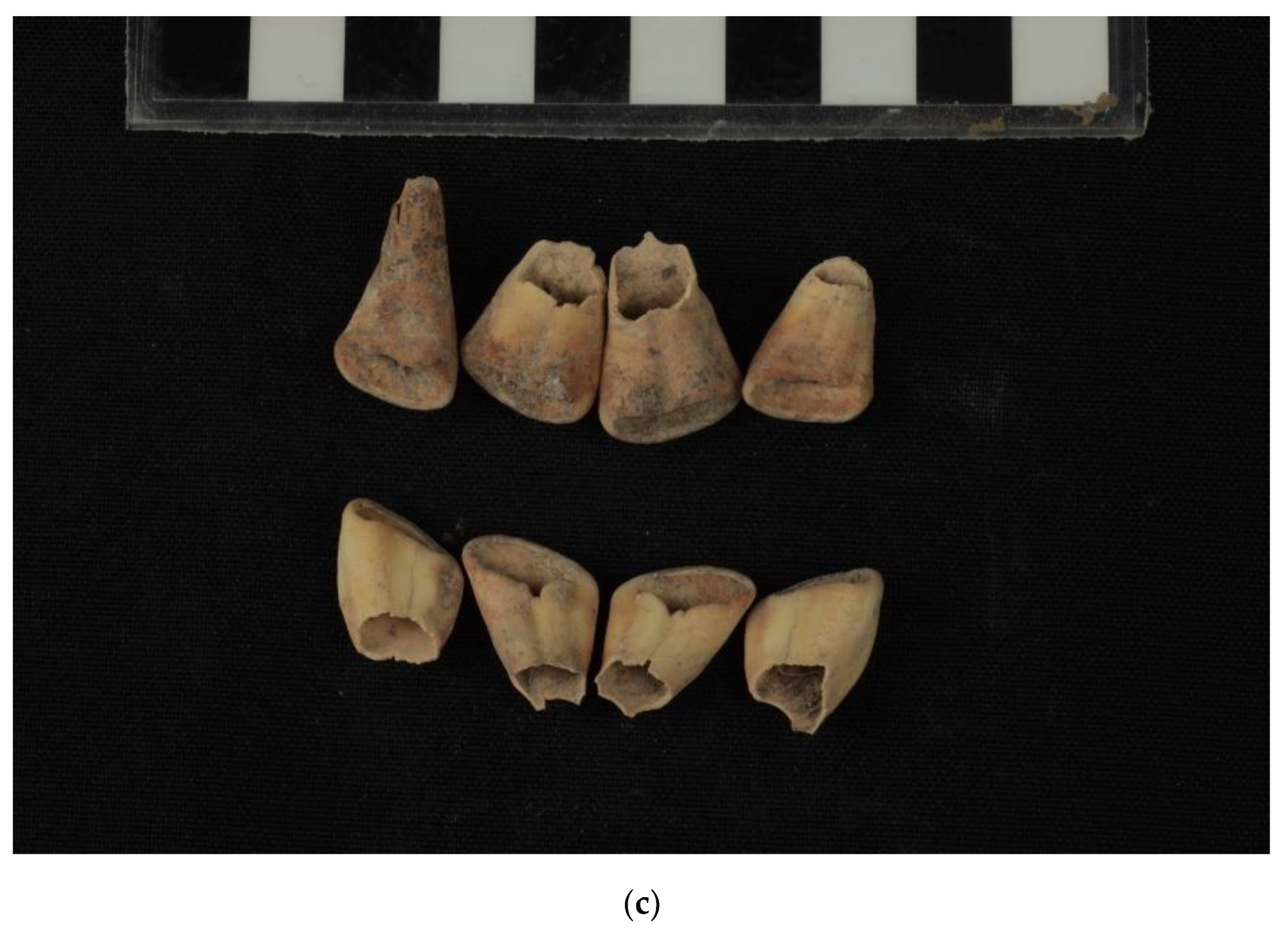

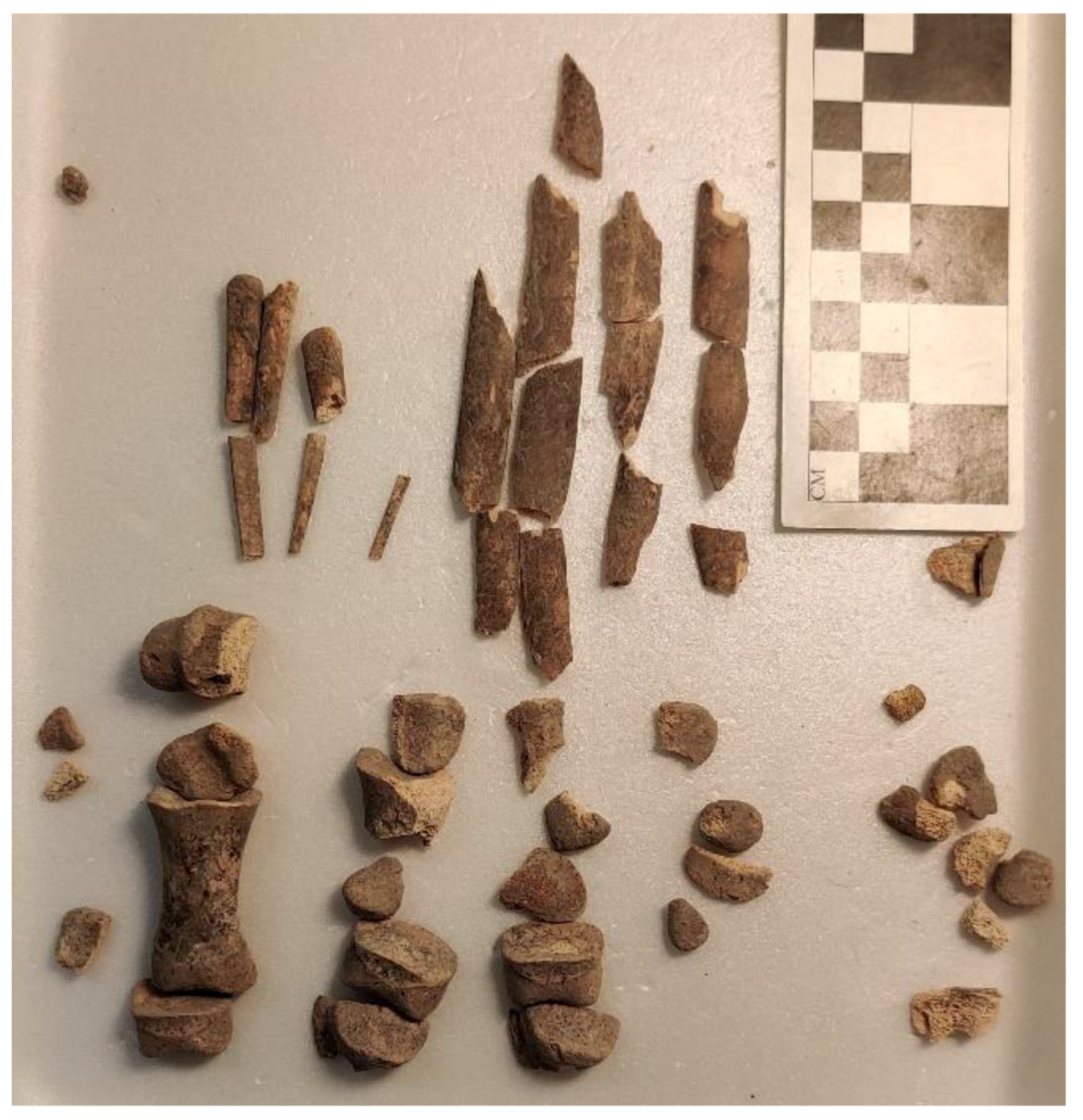

6.4. Donkey Burials as Ritual Foundation Deposits

6.4.1. Votive Vessels

6.4.2. Donkey Burials

7. Textual Analogies for Donkey Ritual Internments

“They brought me a puppy and a hazii-bird to ‘kill’ the donkey foal (i.e., make peace) between the Haneans and Idamaras but I feared my lord and did not give over the puppy and hazu-bird. I had a donkey foal whose mother was a she-donkey killed (and) I established peace between the Haneans and Idamaras”.(ARM 2 37:6-14) [107]

“And every firstling [male in Hebrew] of an ass you shall redeem with a lamb; and if you will not redeem it, then you shall break his neck…”.(Exodus 13:13)

8. Discussion—Why Bury a Domestic Ass under Your Floor?

8.1. Donkey Caravaners and a Specialised Merchant Class

8.2. Sacred vs. Profane—Butchered Donkeys

8.3. Neighbouring Parallels and the ‘Cult of the Beast of Burden’

“Within the Ancient Near East, three themes stand out: the donkey’s role as an indispensable vehicle for moving goods over both short and long distances, most conspicuously in the trade of metal and textiles between Assyria and Anatolia in the early second millennium bc; its elite associations as a prized riding animal; and its religious significance as reflected in rituals governing the conclusion of treaties, the celebration of festivals linked to individual gods, and the curing of illness.”.(p. 11 of [129])

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Milevski, I.; Horwitz, L.K. Domestication of the donkey (Equus asinus) in the southern Levant: Archaeozoology, iconography and economy. In Animals and Human Society in Asia: Historical, Cultural and Ethical Perspectives; Kowner, R., Guy, B.-O., Biran, M., Shahar, M., Shelach-Lavi, G., Eds.; The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019; pp. 93–148. [Google Scholar]

- Milevski, I.; Horwitz, L.K. Unpublished conference paper ‘Donkey Figurines and the “Cult of Exchange” in the Early Bronze Age’. In Proceedings of the Cult and Interaction in the Early and Intermediate Bronze Ages, Ramat Gan, Israel, 22 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, I. (Ed.) Religion in the Emergence of Civilization: Çatalhöyük as a Case Study; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, R.A. Pigs for the Ancestors: Ritual in the Ecology of a New Guinea People, 2nd ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, I. (Ed.) Religion, History, and Place in the Origin of Settled Life; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Insoll, T. Archaeology, Ritual, Religion; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Insoll, T. Archaeology of cult and religion. In Archaeology: The Key Concepts; Renfrew, C., Bahn, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Insoll, T. (Ed.) The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stowers, S.K. Theorizing the religion of ancient households and families. In Household and Family Religion in Antiquity; Bodel, J., Olyan, S.M., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, I. Symbols in Action: Ethnoarchaeological Studies of Material Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Binford, L.R. Mortuary Practices: Their Study and Potential. In Approaches to the Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices; Brown, J., Ed.; Society for American Archaeology: Washington, DC, USA, 1971; pp. 6–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, D.; Pearce, D.G. Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos, and the Realm of the Gods; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, C. (Ed.) The Archaeology of Cult: The Sanctuary at Phylakopi; British School of Archaeology at Athens: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shanks, M.; Tilley, C. Ideology, symbolic power and ritual communication: A reinterpretation of Neolithic mortuary practices. In Symbolic and Structural Archaeology; Hodder, I., Ed.; New Directions in Archaeology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982; pp. 129–154. [Google Scholar]

- Insoll, T. Introduction: Ritual and religion in archaeological perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion; Insoll, T., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Laneri, N. (Ed.) Defining the Sacred: Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, C. Production and consumption in a sacred economy: The material correlates of high devotional expression at Chaco Canyon. Am. Antiq. 2001, 66, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, C. Towards a framework for the archaeology of cult practice. In The Archaeology of Cult: The Sanctuary at Phylakopi; Renfrew, C., Ed.; British School of Archaeology at Athens: London, UK, 1985; pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, I. Introduction: Two forms of history making in the Neolithic of the Middle East. In Religion, History, and Place in the Origin of Settled Life; Hodder, I., Ed.; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2018; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, C. Archaeology theory and method: Some suggestions from the Old World. Am. Anthropol. 1954, 56, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, A.L. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, M. Mesopotamia. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion; Insoll, T., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 775–794. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E.T. Beyond Culture; Anchor/Doubleday: Garden City, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, K. Sie Bauten den Ersten Tempel: Das Rätselhafte Heiligtum der Steinzeitjäger; Beck: Munich, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, K. Göbekli Tepe—the Stone Age sanctuaries: New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs. Doc. Praehist. 2010, XXXVII, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K. Göbekli Tepe. In The Neolithic in Turkey: The Euphrates Basin; özdogğan, M., Başgelen, N., Kuniholm, P., Eds.; Archaeology and Art Publications: Istanbul, Turkey, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 41–83. [Google Scholar]

- Childe, V.G. New Light on the Most Ancient East; Routledge and K. Paul: London, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, G.J. Producers, patrons, and prestige: Craft specialists and emergent elites in Mesopotamia from 5500–3100 B.C. In Craft Specialization and Social Evolution: In Memory of V. Gordon Childe; Wailes, B., Ed.; University Museum Symposium Series; The University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996; pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Güneş, D. Sedentism and solitude: Exploring the impact of private space on social cohesion in the Neolithic. In Religion, History, and Place in the Origin of Settled Life; Hodder, I., Ed.; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2018; pp. 162–185. [Google Scholar]

- Shults, F.L.; Wildman, W.J. Simulating religious entanglement and social investment in the Neolithic. In Religion, History, and Place in the Origin of Settled Life; Hodder, I., Ed.; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2018; pp. 33–63. [Google Scholar]

- Graeber, D.; Wengrow, D. The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, I. (Ed.) Čatalhöyük Perspectives Reports from the 1995–99 Seasons; Monograph of the McDonald Institute and the British Institutes of Archaeology at Ankara: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, I.; Pels, P. History houses: A new interpretation of architectural elaboration at Catalhoyuk. In Religion in the Emergence of Civilization: Çatalhöyük as a Case Study; Hodder, I., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 163–186. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, S. The Early Bronze Age of the southern Levant. In Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader; Richard, S., Ed.; Eisenbrauns: Winona Lake, IN, USA, 2003; pp. 280–296. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, T.P.; Savage, H.H. Settlement heterogeneity and multivariate craft production in the Early Bronze Age southern Levant. J. Mediterr. Archaeol. 2003, 16, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, G. The Early Bronze Age I–III. In Jordan: An Archaeological Reader, 2nd ed.; Adams, R.B., Ed.; Equinox: London, UK, 2008; pp. 161–226. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, R. The Archaeology of the Bronze Age Levant: From Urban Origins to the Demise of City-States, 3700–1000 BCE; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Miroschedji, P.D. Monumental architecture and sociopolitical developments in the southern Levant of the Early Bronze Age. In New Horizons in the Study of the Early Bronze III and Early Bronze IV of the Levant; Richard, S., Ed.; Eisenbrauns: University Park, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Miroschedji, P.D. The urbanization of the southern Levant in its Near Eastern setting. Origini 2018, 42, 109–148. [Google Scholar]

- Miroschedi, P.D. Les villes de Palestine de l’âge du bronze ancien à l’âge du fer dans leur contexte proche-oriental. In De la Maison à la Ville Dans L’Orient Ancien: La Ville et les Débuts de L’urbanisation; Michel, C., Ed.; Cahier des Thèmes transversaux ArScAn; CNRS: Nanterre, France, 2013; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, I. Two notes on Early Bronze Age urbanization and urbanism. J. Inst. Archaeol. Tel Aviv Univ. 1995, 22, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumin, S.; Melamed, Y.; Maeir, A.M.; Greenfield, H.J.; Weiss, E. Agricultural subsistence, land use and long-distance mobility within the Early Bronze Age southern Levant: Archaeobotanical evidence from the urban site of Tell eṣ-Ṣâfī/Gath. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 37, 102873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumin, S.; Melamed, Y.; Weiss, E. Diet and environment at Early Bronze Age Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath: The botanical evidence. In Proceedings of the ASOR’s Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 19–22 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Greenfield, T.L.; Arnold, E.R.; Shai, I.; Albaz, S.; Maeir, A.M. Evidence for movement of goods and animals from Egypt to Canaan during the Early Bronze of the southern Levant: A view from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath. Ägypten und Levante 2020, 30, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milevski, I. Local exchange in the southern Levant during the Early Bronze Age: A political economy viewpoint. Antig. Oriente 2009, 7, 125–160. [Google Scholar]

- Milevski, I. Early Bronze Age Goods Exchange in the Southern Levant: A Marxist Perspective; Equinox Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Milevski, I. Craft specialization and exchange of flint tools in the southern Levant during the Early Bronze Age. Lithic Technol. 2013, 38, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manclossi, F.; Rosen, S. Flint Trade in the Protohistoric Levant: The Complexities and Implications of Tabular Scraper Exchange in the Levantine Protohistoric Periods; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Manclossi, F.; Rosen, S.A. What we can learn from the flint industries from Tell eș-Șâfi/Gath. Near East Archaeol. 2017, 81, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J. What Makes a Pot: Transformations in Ceramic Manufacture and Potting Communities in Early Urban Societies of the 3rd Millennium BCE—A Chaîne Opératoire Perspective from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath (Israel). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2020, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J.; Greenfield, H.J.; Fowler, K.D.; Maeir, A.M. In search of Early Bronze Age potters Tell es-Sâfi/Gath: A new perspective on vessel manufacture for discriminating Chaînes Opératoires. Archaeol. Rev. Camb. 2020, 35, 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, J.R.; Uziel, J.; Welch, E.L.; Maeir, A.M. Walled up to heaven! Early and Middle Bronze Age fortifications at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath. Near East. Archaeol. 2017, 80, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shai, I.; Chadwick, J.R.; Welch, E.; Katz, J.; Greenfield, H.J.; Maeir, A.M. The Early Bronze Age fortifications at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. Palest. Explor. Q. 2016, 148, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, E.; Chadwick, J.R.; Shai, I.; Katz, J.C.; Greenfield, H.J.; Dagan, A.; Maeir, A.M. The limits of the ancient city: The fortifications of Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath 115 Years after Bliss and Macalister. In Exploring the Holy Land: 150 Years of the F’alestine Exploration Fund; Gurevich, D., Kidron, A., Eds.; Equinox Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2019; pp. 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kempinski, A. Fortifications, public buildings, and town planning in the Early Bronze Age. In The Architecture of Ancient Israel from the Prehistoric to the Persian Periods, In Memory of Immanuel (Munya) Dunayevsky; Kempinski, A., Reich, R., Eds.; Israel Exploration Society: Jerusalem, Israel, 1992; pp. 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, A. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000–586 B.C.E.; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, A. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000–586 BCE, 2nd ed.; Yale University Press Impression, Ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miroschedji, P.D. Cult and religion in the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age. In Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Biblical Archaeology, Jerusalem, Israel, June–July 1990; Biran, A., Aviram, J., Eds.; Israel Exploration Society & The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1990; pp. 208–220. [Google Scholar]

- Miroschedji, P.D. The southern Levant (Cisjordan) during the Early Bronze Age. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant c. 8000–332 BCE; Steiner, M.L., Killebrew, A.E., Eds.; Oxford Handbooks in Archaeology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 308–328. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, M. Early Shrines at Byblos and Tell Es-Sultan/Ancient Jericho in the Early Bronze I (3300–3000 BC). In Byblos and Jericho in the Early Bronze I: Social Dynamics and Cultural Interactions; Nigro, L., Ed.; Studies on the Archaeology of Palestine and Transjordan: Expedition to Palestine & Jordan; La Sapienza: Roma, Italy, 2007; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, M. Sanctuaries, temples and cult places in Early Bronze I Southern Levant. Vicino Medio Oriente 2011, XV, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ussishkin, D. Megiddo-Armageddon: The Story of the Canaanite and Israelite City; Israel Exploration Society and Biblical Archaeology Society: Jerusalem, Israel, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M.J.; Finkelstein, I.; Ussishkin, D. The Great Temple of Early Bronze I Megiddo. Am. J. Archaeol. 2014, 118, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg-Degen, D.; Galili, R.; Rosen, S.A. Before God: Reconstructing ritual in the desert in proto-historic times. Entangled Relig. 2021, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesson, M.S. Libraries of the dead: Early Bronze Age charnel houses and social identity at urban Bab edh-Dhra’, Jordan. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 1999, 18, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortner, D.J.; Frohlich, B. The Early Bronze Age I Tombs and Burials of Bâb Edh-Dhrâ, Jordan. Reports of the Expedition to the Dead Sea Plain, Jordan; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2008; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Amiran, R. A cult stele from Arad. Isr. Explor. J. 1972, 22, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Neolithic ritual complex discovered in Jordan: Two stelae are examples of some of the oldest artistic expressions in the Middle East. The Past, 2022. Available online: https://the-past.com/news/ritual-and-hunting-in-neolithic-jordan/(accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Shai, I.; Uziel, J. The why and why nots of writing: Literacy and illiteracy in the southern Levant during the Bronze Ages. Kaskal 2010, 7, 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Shai, I.; Maeir, A.M. Understanding Early Bronze urban patterns from the perspective of an EB III commoner neighbourhood: The excavations at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. In Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Basel, Switzerland, 9–13 June 2014; Stucky, R.A., Kaelin, O., Mathys, H.-P., Eds.; Harrassowitz Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 479–485. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Shai, I.; Maeir, A.M. The Early Bronze Age at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath. Near East. Archaeol. 2017, 80, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Shai, I.; Maeir, A.M. Domestic life during the Early Bronze III: A view from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath. In New Horizons in the Study of the Early Bronze III and Early Bronze IV in the Levant; Richard, S., Ed.; Eisenbrauns: University Park, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Shai, I.; Greenfield, H.J.; Eliyahu-Behar, A.; Regev, J.; Boaretto, E.; Maeir, A.M. The Early Bronze Age remains at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel: An interim report. J. Inst. Archaeol. Tel Aviv Univ. 2014, 41, 20–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Wing, D.; Maeir, A.M. Terrestrial LiDAR survey as a heritage management tool: The example of Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. In Challenges, Strategies and Hi-Tech Applications for Saving Cultural Heritage of Syria, Proceedings of the Workshop Held at the 10th ICAANE in Vienna, 25–26 April 2016; Silver, M.A., Ed.; Oriental and European Archaeology Series; Austrian Academy of Sciences Press: Vienna, Austria, 2022; pp. 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, N.; Nigro, L. Excavations at Jericho, 1998. Preliminary Report on the Second Season of Excavations and Surveys at Tell Es-Sultan, Palestine (Quaderni Di Gerico 2); La Sapienza: Roma, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nigro, L.; Sala, M. Tell Es-Sultan/Jericho in the Early Bronze II (3000–2700 BC): The Rise of an Early Palestinian City—Synthesis of the Results of Four Archaeological Expeditions. Studies on the Archaeology of Palestine & Transjordan; Universita di La Sapienza: Rome, Italy, 2010; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Sebag, D. The Early Bronze Age dwellings in the southern Levant. Bull. Du Cent. De Rech. Français À Jérusalem 2005, 16, 222–235. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, R.; Paz, S.; Wengrow, D.; Iserlis, M. Tell Bet Yerah: Hub of the Early Bronze Age Levant. Near East. Archaeol. 2012, 75, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, R.; Paz, S. Early Bronze Age architecture, function, and planning. In Bet Yerah, The Early Bronze Age Mound Volume II: Urban Structure and Material Culture 1933–1986 Excavations. IAA Reports 54; Greenberg, R., Ed.; Israel Antiquities Authority: Jerusalem, Israel, 2014; pp. 15–52. [Google Scholar]

- Herr, L.; Clark, D.R. From the Stone Age to the Middle Ages in Jordan: Digging up Tall Al-‘Umayri. Near East. Archaeol. 2009, 72, 68–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.M. Tell Abu al-Kharaz in the Jordan Valley Volume I: The Early Bronze Age; Verlage der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Vienna, Austria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yamafuji, M. Domestic Dwellings during Early Bronze Age, Southern Levant. In Decades in Deserts: Essays on Near Eastern Archaeology in Honour of Sumio Fujii; Nakamura, S., Adachi, T., Abe, M., Eds.; Rokuichi Syobou: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; pp. 119–152. [Google Scholar]

- Albaz, S. Everyday Life in a Local Neighborhood at an Ancient Urban Settlement: Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath in the Early Bronze Age as a Case Study (In Hebrew). Ph.D. Thesis, Bar-Ilan University, Givat Shmuel, Israel, 2019, unpublished. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Ross, J.; Albaz, S.; Greenfield, T.L.; Beller, J.A.; Frumin, S.; Weiss, E.; Maeir, A.M. Household archaeology during the Early Bronze Age of Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath. In Households in Levantine Archaeology; Steadman, S., Brody, A.J., Battini, L., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, in press.

- Fischer, P.M. Tell Abu Al-Kharaz: A bead in the Jordan Valley. Near East. Archaeol. 2008, 71, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Brown, A.; Shai, I.; Maeir, A.M. Preliminary analysis of the fauna from the Early Bronze Age III neighbourhood at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. In Bones and Identity: Zooarchaeological Approaches to Reconstructing Social and Cultural Landscapes in Southwest Asia. Proceedings of the ICAZ-SW Asia Conference, Haifa, Israel, 23–28 June 2013; Marom, N., Yeshurun, R., Weissbrod, L., Bar-Oz, G., Eds.; Oxbow Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 170–192. [Google Scholar]

- Loud, G. Megiddo II. Seasons of 1935-1939, Volumes 1 (Text) and 2 (Plates). Oriental Institute Publication 62; Oriental Institute of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Yekutieli, Y. The Early Bronze Age Southern Levant: The ideology of an aniconic reformation. In The Cambridge Prehistory of the Bronze and Iron Age Mediterranean; Knapp, A.B., Dommelen, P.V., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 609–618. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ajlouny, F.; Douglas, K.; Khrisat, B.; Mayyas, A. Laden animal and riding figurines from Khirbet ez-Zeraqōn and their implications for trade in the Early Bronze Age. Z. Des Dtsch. Palästina Ver. 2012, 128, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hizmi, H. An Early Bronze Age saddle donkey figurine from Khirbet el-Mahruq and the emerging appearance of Beast of Burden figurines. In Burial Caves and Sites in Judea and Samaria from the Bronze and Iron Ages; Hizmi, H., De-Groot, A., Eds.; IAA Judea and Samaria Publications: Jerusalem, Israel, 2004; pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Shai, I.; Greenfield, H.J.; Brown, A.; Albaz, S.; Maeir, A.M. The importance of the donkey as a pack animal in the Early Bronze Age southern Levant: A view from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath. Z. Des Dtsch. Palästina Ver. 2016, 132, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, S.; Greenberg, R. Conceiving the city: Streets and incipient urbanism at Early Bronze Age Bet Yerah. J. Mediterr. Archaeol. 2016, 29, 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, L.A. Lord of the Desert. Available online: https://www.imj.org.il/en/exhibitions/special-display-lord-desert (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Ambos, C. Mesopotamische Baurituale aus dem 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. (in German)—Cites Source for Text: R. Borger, Symbolae Biblicae et Mesopotamicae F.M.Th. de Liagre Böhl Dedicatae, 1973; Islet Verlag: Glashütte, Germany, 2004; pp. 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, J. Objects and ancient religions. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia: Religion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosiewicz, L. Cattle offering from the temple of Montuhotep, Sankhkara (Thebes, Egypt). In Archaeozoology of the Near East IV B: Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on the Archaeozoology of Southwestern Asia and Adjacent Areas; Mashkour, M., Choyke, A., Buitenhuis, H., Poplin, F., Eds.; ARC: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Way, K.C. Donkeys in the Biblical World: Ceremony and Symbol; Eisenbrauns: Winona Lake, IN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klenck, J.D. The Canaanite Cultic Milieu: The Zooarchaeological Evidence from Tel Haror, Israel; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, J.C. The Archaeology of Cult in Middle Bronze Age Canaan: The Sacred Area at Tel Haror, Israel; Georgias Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 40. [Google Scholar]

- Mensan, R. Tuthmosid foundation deposits at Karnak. Egypt. Archaeol. 2007, 30, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sakr, F.M. New foundation deposits of Kom el-Hisn. Stud. Zur Altägyptischen Kult. 2005, 33, 349–355. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, J.M. Foundation Deposits in Ancient Egypt. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1973. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Shai, I.; Maeir, A.M. Being an “ass”: An Early Bronze Age burial of a donkey from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. Bioarchaeol. Near East 2012, 6, 21–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Greenfield, T.L.; Shai, I.; Albaz, S.; Maeir, A.M. Household rituals and sacrificial donkeys: Why are there so many domestic donkeys buried in an Early Bronze Age neighborhood at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath. Near East. Archaeol. 2018, 81, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Ross, J.; Greenfield, T.L.; Maeir, A.M. Sacred and the profane: Donkey burial and consumption at Early Bronze Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath. In Fierce Lions, Angry Mice and Fat-Tailed Sheep: Animal Encounters in the Ancient Near East; Recht, L., Tsouparopoulou, C., Eds.; McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Shai, I.; Uziel, J.; Maeir, A.M. The architecture and stratigraphy of Area E: Strata E1–E5. In Tell Eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath I: Report on the 1996–2005 Seasons; Maeir, A.M., Ed.; Ägypten und Altes Testament 69; Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Scurlock, J. Animal sacrifice in ancient Mesopotamian religion. In A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East; Collins, B.J., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 389–404. [Google Scholar]

- Borowski, O. Every Living Thing: Daily Use of Animals in Ancient Israel; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Borowski, O. Animals in the religions of Syria-Palestine. In A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East; Collins, B.J., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 405–426. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, B.; Wapnish, P.; Greer, J. Scripts of animal sacrifice in Levantine Culture-History. In Sacred Killing: The Archaeology of Sacrifice in the Ancient Near East; Porter, A., Schwartz, G.M., Eds.; Eisenbrauns: Winona Lake, IN, USA, 2012; pp. 217–235. [Google Scholar]

- Chahoud, J.; Vila, E. Food for the dead, food for the living, food for the gods according to faunal data from the Ancient Near East. In Religion et Alimentation en Égypte et Orient Anciens; Arnette, M.-L., Ed.; Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale: Cairo, Egypt, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 465–521. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, B.J. Animals in the religions of ancient Anatolia. In A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East; Collins, B.J., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 309–334. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, B.J. (Ed.) A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Levinger, I.M. Modern Kosher Food Production from Animal Source. Institute for Agricultural Research According to the Tora; Yad HaHamisha Printing: Kfar Chabad, Israel, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, H.J.; Shai, I.; Greenfield, T.L.; Arnold, E.; Brown, A.; Eliyahu, A.; Maeir, A.M. Earliest evidence for equid bit wear in the ancient Near East: The "ass" from Early Bronze Age Gath (Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi), Israel. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnold, E.R.; Hartman, G.; Greenfield, H.J.; Shai, I.; Babcock, L.E.; Maeir, A.M. Isotopic evidence for early trade in animals between Old Kingdom Egypt and Canaan. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilan, O.; Sebbane, M. Copper metallurgy, trade, and the urbanization of southern Canaan in the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age. In L’Urbanisation de la Palestine à L’Âge du Bronze Ancien; De Miroschedji, P., Ed.; British Archaeological Reports, International Series 527; BAR: Oxford, UK, 1989; pp. 139–162. [Google Scholar]

- Milevski, I. Local Exchange in Early Bronze Age Canaan. Ph.D. Thesis, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel, 2005. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, C. Laden animal figurines from the Chalcolithic period in Palestine. Bull. Am. Sch. Orient. Res. 1985, 258, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiran, R. More about the Chalcolithic culture of the Palestine and Tepe Yahya. Isr. Explor. J. 1976, 26, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, C.M. Money and traders. In A Companion to the Ancient Near East, 2nd ed.; Snell, D.C., Ed.; Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Atici, L.; Kulakoğlu, F.; Barjamovic, G.; Fairbairn, A. (Eds.) Current Research at Kültepe-Kanesh: An Interdisciplinary and Integrative Approach to Trade Networks, Internationalism, and Identity; Lockwood Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhof, K.R. Kanesh: An Assyrian colony in Anatolia. In Civilization of the Ancient Near East; Sasson, J.M., Baines, J., Beckman, G., Rubinson, K.S., Eds.; Simon & Schuster and Prentice Hall International: New York, NY, USA, 1995; Volume 2, pp. 859–871. [Google Scholar]

- Sieber, N. The economic impact of pack donkeys in Makete, Tanzania. In Donkeys, People and Development. A Resource book of the Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa; Starkey, P., Fielding, D., Eds.; ATNESA: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 118–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kidanmariam, G. The use of donkeys for transport in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. In Donkeys, People and Development: A Resource Book of the Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa; Starkey, P., Fielding, D., Eds.; ATNESA: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, A.G.; Tegegne, A.; Yami, A. Research needs of donkey utilization in Ethiopia. In Donkeys, People and Development. A Resource Book of the Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa; Starkey, P., Fielding, D., Eds.; ATNESA: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sapir-Hen, L.; Gadot, Y.; Lipschits, O. Ceremonial donkey burial, social status, and settlement hierarchy in the Early Bronze III: The case of Tel Azekah. In The Wide Lens in Archaeology: Honoring Brian Hesse’s Contributions to Anthropological Archaeology; Lev-Tov, J., Wapnish, P., Gilbert, A., Eds.; Lockwood Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017; pp. 259–270. [Google Scholar]

- Manclossi, F.; Rosen, S.A.; Milevski, I. Canaanean Blade Technology: New insights from Horvat Ptora (North), an Early Bronze Age I site in Israel. JIPS 2019, 49, 284–315. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, P.J. The Donkey in Human History: An Archaeological Perspective; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MacGinnis, J. A Neo-Assyrian text describing a royal funeral. State Arch. Assyria Bull. 1987, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, A.M.; Schwartz, G.M. (Eds.) Sacred Killing: The Archaeology of Sacrifice in the Ancient Near East; Eisenbrauns: Winona Lake, IN, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, E. Des inhumations d’équidés retrouvées à Tell Chuera (Bronze Ancien, Syrie du Nord-Est). In Les Équidés dans le Monde Méditerranéen Antique: Actes du Colloque Organisé par L’École Française D’Athènes, le Centre Camille Jullian, et l’UMR 5140 du CNRS; Gardeisen, A., Ed.; Monographies d’Archéologie Méditerranéenne; Publication de l’UMR 5140 du CNRS “Archéologie des Sociétés Méditerranéennes: Milieux, Territoires, Civilisations” Édition de l’Association pour le Développement de l’Archéologie en Languedoc-Roussillon Lattes: Athens, Greece, 2005; pp. 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock, J. Ritual burials of a dog and six domestic donkeys. In The Excavations at Tell Brak 2: Nagar in the Third Millennium B.C.; Oates, D., Oates, J., McDonald, H., Eds.; The McDonald Institute of Archaeology, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- De Miroschedji, P.; Sadek, M.; Faltings, D.; Boulez, V.; Naggiar-Moliner, L.; Sykes, N.; Tengberg, M. Les fouilles de Tell es-Sakan (Gaza): Nouvelles données sur les contacts Égypto-cananéens aux IVe–IIIe millénaires. Paléorient 2001, 27, 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver (Lönnqvist), M. Equid burials in archaeological contexts in the Amorite, Hurrian and Hyksos cultural intercourse. Aram Zoroastrianism Levant Amorites 2014, 26, 335–355. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, G.M. Memory and its demolition: Ancestors, animals, and sacrifice at Umm el-Marra, Syria. Camb. Archaeol. J. 2013, 23, 495–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Olmo Lete, G. Incantations and Anti-Witchcraft Texts from Ugarit; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wyat, N. Religious Texts from Ugarit, 2nd ed.; Sheffield Academic Press: Sheffield, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, E.A.; Weber, J.; Bendhafer, W.; Champlot, S.; Peters, J.; Schwartz, G.M.; Grange, T.; Geigl, E.-M. The genetic identity of the earliest human-made hybrid animals, the Kungas of Syro-Mesopotamia. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm0218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Way, K.C. Assessing sacred asses: Bronze Age donkey burials in the Near East. Levant 2010, 42, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulder, J. Working Donkeys in 4th–3rd Millennium BC Mesopotamia; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, D.T. Equus asinus in highland Iran: Evidence old and new. In Between Sand and Sea. The Archaeology and Human Ecology of Southwestern Asia: Festschrift in honor of Hans-Peter Uerpmann; Conard, N.J., Drechsler, P., Morales, A., Eds.; Kerns Verlag: Tübingen, Germany, 2011; pp. 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Maeir, A.M.; Shai, I.; Horwitz, L.K. ‘Like a Lion in Cover’: A cylinder seal from Early Bronze Age III Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. Isr. Explor. J. 2011, 61, 12–31. [Google Scholar]

- Eliyahu-Behar, A.; Albaz, S.; Shai, I.; Maeir, A.M.; Greenfield, H.J. Faience beads from Early Bronze Age contexts at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2016, 7, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beller, J.A. Early Bronze Age basalt vessel remains from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath. Near East. Archaeol. 2017, 80, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beller, J.A.; Greenfield, H.J.; Fayek, M.; Shai, I.; Maeir, A.M. Raw material variety and acquisition of the EB III ground stone assemblages at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. In Stone Tools in the Ancient Near East and Egypt: Ground Stone Tools, Rock-Cut Installations and Stone Vessels from the Prehistory to Late Antiquity; Squitieri, A., Eitam, D., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 121–152. [Google Scholar]

- Beller, J.A.; Greenfield, H.J.; Fayek, M.; Shai, I.; Maeir, A.M. Provenance and exchange of basalt ground stone artefacts of EB III Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2016, 9, 226–237. [Google Scholar]

- Beller, J.A.; Greenfield, H.J.; Shai, I.; Maeir, A.M. The life-history of basalt ground stone artefacts of EB III Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. J. Lithic Stud. 2016, 3, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Algaze, G.; Greenfield, H.J.; Hald, M.M.; Hartenberger, B.; Irvine, B.; Matney, T.C.; Nishimura, Y.; Pournelle, J.; Rosen, S.A. Early Bronze Age urbanism in southeastern Anatolia and Upper Mesopotamia: Recent analyses from Titriş Höyük. Antatolica 2021, XLVII, 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Tresguerrez Velasco, J.A. The “Temple of the Serpents”: A sanctuary in the Early Bronze Age I in the village of Jabal Mutawwaq (Jordan). Annu. Dep. Antiq. Jordan 2008, 52, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yekutieli, Y. Symbols in action—the Megiddo Graffiti re-assessed. In Egypt at Its Origins 2, Proceedings of an International Conference “Origins of the State: Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt” Toulousse, France, 5–8 September 2005; Midant-Reynes, B., Tristant, Y., Eds.; Peeters: Leuven, Belgium, 2008; pp. 807–837. [Google Scholar]

- Sebag, D. Architecture and building methods as an illustration of social differentiation in the Early Bronze Age city-states of the southern Levant. In Near Eastern Archaeology in the Past, Present and Future, Heritage and Identity, Ethnoarchaeological and Interdisciplinary Approach, Results and Perspectives, Visual Expression and Craft Production in the Definition of Social Relations and Status, Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Sapienza, Italy, 5–10 May 2009; Matthiae, P., Pinnock, F., Nigro, L., Marchetti, N., Eds.; Harrassowitz Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 973–982. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Greenfield, H.J.; Ross, J.; Greenfield, T.L.; Albaz, S.; Richardson, S.J.; Maeir, A.M. Household Rituals and Merchant Caravanners: The Phenomenon of Early Bronze Age Donkey Burials from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. Animals 2022, 12, 1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12151931

Greenfield HJ, Ross J, Greenfield TL, Albaz S, Richardson SJ, Maeir AM. Household Rituals and Merchant Caravanners: The Phenomenon of Early Bronze Age Donkey Burials from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. Animals. 2022; 12(15):1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12151931

Chicago/Turabian StyleGreenfield, Haskel J., Jon Ross, Tina L. Greenfield, Shira Albaz, Sarah J. Richardson, and Aren M. Maeir. 2022. "Household Rituals and Merchant Caravanners: The Phenomenon of Early Bronze Age Donkey Burials from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel" Animals 12, no. 15: 1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12151931

APA StyleGreenfield, H. J., Ross, J., Greenfield, T. L., Albaz, S., Richardson, S. J., & Maeir, A. M. (2022). Household Rituals and Merchant Caravanners: The Phenomenon of Early Bronze Age Donkey Burials from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Israel. Animals, 12(15), 1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12151931