Abstract

Blood parasites of the Haemosporida order, such as the Plasmodium spp. responsible for malaria, have become the focus of many studies in evolutionary biology. However, there is a lack of molecular investigation of haemosporidian parasites of wildlife, such as the genus Polychromophilus. Species of this neglected genus exclusively have been described in bats, mainly in Europe, Asia, and Africa, but little is known about its presence and genetic diversity on the American continent. Here, we investigated 406 bats from sites inserted in remnant fragments of the Atlantic Forest and Cerrado biomes and urbanized areas from southern Brazil for the presence of Polychromophilus species by PCR of the mitochondrial cytochrome b encoding gene. A total of 1.2% of bats was positive for Polychromophilus, providing the first molecular information of these parasites in Myotis riparius and Eptesicus diminutus, common vespertilionid bats widely distributed in different Brazilian biomes, and Myotis ruber, an endangered species. A Bayesian analysis was conducted to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships between Polychromophilus recovered from Brazilian bats and those identified elsewhere. Sequences of Brazilian Polychromophilus lineages were placed with P. murinus and in a clade distinct from P. melanipherus, mainly restricted to bats in the family Vespertilionidae. However, the sequences were split into two minor clades, according to the genus of hosts, indicating that P. murinus and a distinct species may be circulating in Brazil. Morphological observations combined with additional molecular studies are needed to conclude and describe these Polychromophilus species.

1. Introduction

The phylum Apicomplexa forms one of the most diverse groups of unicellular protists with a wide environmental distribution. They are classified as mandatory intracellular parasites and they have mobile invasive stages. They are characterized by the presence of an evolutionarily unique structure called the apical complex, used to adhere and invade host cells. Many of the species that are part of this group are considered pathogens in humans and other vertebrates. All animal species are believed to host at least one species of apicomplexan parasites [1,2,3]. Apicomplexa are divided into two orders: Eucoccidiorida (coccidian parasites) and Haemosporida (haemosporidian parasites). Haemosporida are organized into four families: Garniidae, Haemoproteidae, Leucocytozoidae, and Plasmodiidae, which include malaria parasites that infect various vertebrates and invertebrate hosts [4].

The hosts of the order Chiroptera have the greatest diversity of haemosporidian parasites among mammals, including nine genera. In addition to the well-known genera (Plasmodium and Hepatocystis), seven genera exclusively infect chiropterans: Polychromophilus, Nycteria, Bioccala, Biguetiella, Dionisia, Johnsprentia, and Sprattiella [5,6], clearly highlighting this group of mammals as a vital tool in the taxonomic, systematic, and evolutionary study of haemosporidians in mammals. Although Bioccala was elevated to a genus in 1984 [7], many studies, as well as this work, still use it as a subgenus of Polychromophilus, since its species present similar morphological characteristics and its genetics have not been studied [8].

The genus Polychromophilus has been found in insectivorous bats in tropical and temperate regions [9,10,11,12]. Only five species of Polychromophilus are known. Although they can be distinguished by slight differences in ultrastructure, they are classified mainly based on the type of host [13]. Of the five species of Polychromophilus described, Polychromophilus (Polychromophilus) melanipherus and Polychromophilus (Bioccala) murinus are mainly linked to two bat families: Miniopteridae and Vespertilionidae, respectively [14]. However, occasionally, P. melanipherus has been reported in Hipposideridae and Vespertilionidae and P. murinus in Rhinolophidae, Hipposideridae, and Miniopteridae [6]. In addition, the species P. (P.) corradetti and P. (P.) adami have been described in bats from the African region: Miniopterus inflatus in Gabon and Miniopterus minor in the Republic of Congo [13].

Recent studies have demonstrated a greater concentration of molecular studies aimed at African and European bats, e.g., [8,15,16,17]. In contrast, our knowledge about haemosporidian parasites of Brazilian bats is still restricted to morphological investigations, such as the case of Polychromophilus (Bioccala) deanei found in Myotis nigricans (Vespertilionidae). Myotis nigricans is an evening bat from Brazil, and is the first chiropteran host in which this group of parasites was found in the New World [18,19]. Nevertheless, no molecular data is available for this parasite in Brazil, and the only sequence of Polychromophilus sp. of bats from the American continent is from Myotis nigricans, from the Vespertilionidae family, found in Panama [20].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

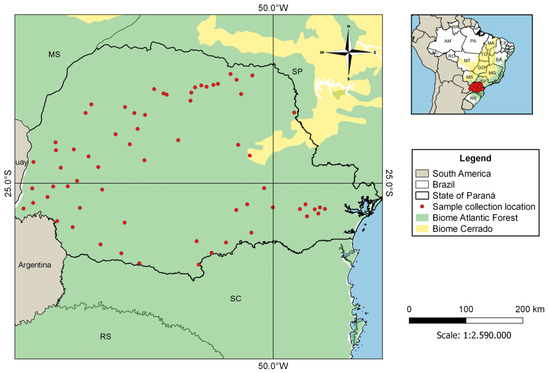

Brain tissue samples of bats with no identified species (n = 406) were acquired from the Parana State Reference Laboratory (LACEN) program for monitoring rabies virus circulation. They were collected between September 2019 and August 2020 in 67 different municipalities in the State of Paraná, most of them inserted in remnant fragments of Atlantic Forest and Cerrado biomes, as well as in urbanized areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of municipalities in the State of Paraná, Brazil, where bat samples were collected.

All tissue samples and bats were collected and handled under appropriate authorizations by the Brazilian government. The project was approved by the Ethics in Use of Animals Committee, CEUA/SESA, of the Centro de Produção e Pesquisa de Imunobiológicos—CPPI/PR (approval number 01/2019 and date of approval 3 March 2020).

2.2. Polychromophilus Detection

The extraction of total nucleic acid (DNA and RNA) from collected samples was performed using the BioGene Extraction kit (K204-4, Bioclin, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

A fragment of ~1.1 kb (approximately 92% of the gene) from the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb) was amplified using a nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR), taking standard precautions to prevent cross-contamination of samples. The PCR reactions were conducted as previously described [21] using primers DW2 and DW4 and 5 uL of genomic DNA in the first reaction, and 1 uL aliquot of this product was used as a template for a nested reaction with primers DW1 and DW6.

PCR products were sequenced using BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit in ABI PRISM® 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using nested PCR primers. The cytb sequences were obtained and aligned with the sequences available at the GenBank® database.

The phylogenetic relationship among reported parasites was inferred using partial cytb gene sequences (1116 bp). GenBank® accessions of the used sequences are shown in the phylogenetic trees. The phylogenetic reconstruction was performed using the Bayesian inference method implemented in MrBayes v3.2.0 [22]. Bayesian inference was executed with two Markov Chain Monte Carlo searches of 3 million generations, with each sampling 1 of 300 trees. After a burn-in of 25%, the remaining 15,002 trees were used to calculate the 50% majority-rule consensus tree. The phylogeny was visualized using FigTree version 1.4.0 [23].

2.3. Host Species Identification

The positive samples were processed using a PCR protocol that amplifies host DNA with primers L14841 and H15149 that were designed to amplify fragments with ~390 bp of the mitochondrial cytb gene from a wide range of animals, including mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish [24]. Amplified fragments were sequenced directly using the corresponding flanking primers. Obtained sequences were compared to other sequences deposited in the GenBank® database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/Blast.cgi accessed on 19 March 2021). The best close match (BCM) algorithm was used to identify the best barcode matches of a query, and the species name of that barcode was assigned to the query if the barcode was sufficiently similar [25]. Positive identification and host species assignment were made when sequences presented a match of >97%.

Alternatively, for some specimens, a fragment with ~650 bp from the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase (coi) gene was amplified by two methods: (i) using the primers VF1_t1 (5′-TGT AAA ACG ACG GCC AGT TCT CAA CCA ACC ACA AAG ACA TTG G-3′) [26] and VR1_t1 (5′-AGG AAA CAG CTA TGA CTA GAC TTC TGG GTG GCC AAA GAA TCA-3′) [27] with PCR conditions and cycling from Kumar et al. [28], and (ii) using the universal primers LCO 1490 and HCO 2198 [29] and PCR protocol based on Ruiz et al. [30].

3. Results

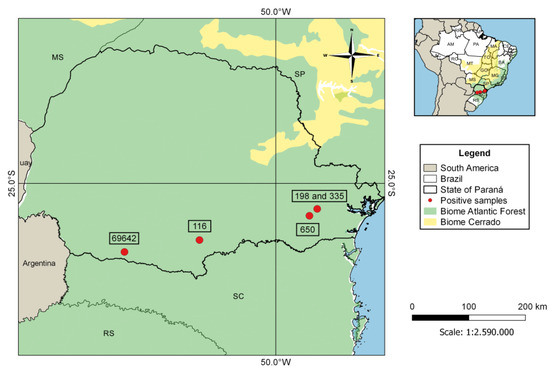

This study detected five samples that were positive for Polychromophilus sp. (sample IDs: 116, 198, 335, 650, and 69642), confirming the presence of parasites of this genus in Brazilian bats. The percentage of positives was 1.2% (5/406) of the number of samples analyzed. Accordingly, the sequences of cytb and coi genes from the positive host samples were from Myotis ruber (116), Myotis riparius (198, 335, and 69642), and Eptesicus diminutus (650), all bats belonging to the Vespertilionidae family, collected in four municipalities in the State of Paraná (Araucaria, Cruz Machado, Curitiba, and Pato Branco) (Figure 2). The two samples obtained in Curitiba city were probably from an urban area since Curitiba is the most populous municipality of Paraná state and the eighth in the country.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the positive samples of Polychromophilus sp. isolates from Paraná state, Brazil.

The nucleic acid polymorphism in mitochondrial cytb sequences (1116 bp) of Polychromophilus sp. isolates from Brazil compared to the best match sequence from GenBank® (#LN483038 of Myotis nigricans from Panama with 595 bp) is shown in Table 1. Thirteen sites were polymorphic among Brazilian sequences (Table 1). The Panamanian sequence, the only available one obtained from bats from the American continent, showed two nucleic acid substitutions found only in this isolate (gray columns) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Nucleic acid polymorphism in mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb) sequences of Polychromophilus sp. isolates from Brazil (116, 198, 335, 650, and 69642) and Panama (MYOPA01).

The sequence obtained from bat 650 was the most divergent, with 98–99% of identity with the others (with 11 or 12 nucleic acid substitutions) (Table 2). The Panamanian sequence presented two to eight nucleic acid substitutions compared to Brazilian sequences (98–99% of identity) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Similarity percentage between the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb) sequences of Polychromophilus sp. found in different bats from Brazil and Panama (MYOPA01).

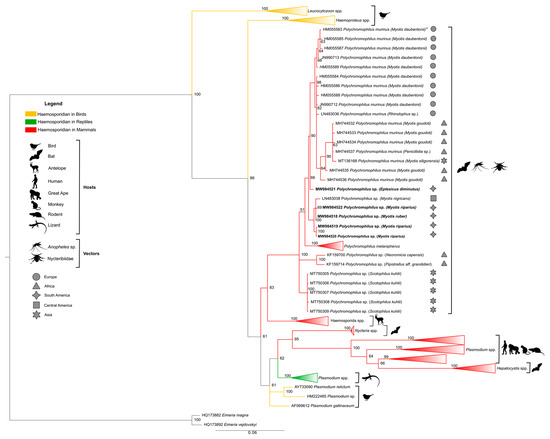

The phylogenetic tree in Figure 3 was generated with reference sequences found in the Genbank® database, covering different haemosporidian genera obtained from different hosts (Table A1, Appendix A). The Polychromophilus sequences found in this study and all sequences of the genus available in the Genbank® database (Table A2, Appendix A) were included. The clade of the genus Polychromophilus is shown in evidence, and the remaining haemosporidian from other genera were collapsed.

Figure 3.

Bayesian phylogeny based on the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb) from Polychromophilus spp. of the sequences identified in the present study (1116 bp) and reference sequences listed in Table A1 and Table A2 in Appendix A. * Sequence HM055583 has also been reported in P. murinus from Eptesicus serotinus, Nyctalus noctule, and Myotis myotis (Table A2, Appendix A). Eimeria spp. were used as an external group. The support values of the nodes (in percentage) indicate posterior probabilities. The red branches highlight the haemosporidian sequences found in mammals. The yellow branches highlight the haemosporidian sequences found in birds. The green branches highlight the haemosporidian sequences found in reptiles. The sequences found in the present study are highlighted in bold. The remaining reference sequences are collapsed to highlight the branch of the Polychromophilus genus.

Phylogenetic analysis based on cytb did not produce conflict in any of the main nodes. All the main genera and subgenera were recovered and represented in the phylogenetic tree by separate monophyletic clades. The results show the existence of four clades within the Haemosporida order analyzed here. Phylogeny also showed Polychromophilus as a sister clade of a group that contains Plasmodium species of ungulates, but with a distant relationship between Plasmodium and Hepatocystis from other mammals, such as primates and rodents.

All Polychromophilus sequences from bats of different parts of the world were grouped into a monophyletic clade (posterior probability of 100) composed of four subclades, with all Polychromophilus found in Brazilian bats segregated in only one of them. The first distinct subclade comprised all sequences of P. melanipherus from Miniopterus bat hosts, and the second subclade exclusively included sequences of Polychromophilus from vespertilionids (including Brazilian ones), confirming a clear separation of parasites from miniopterid and vespertilionid hosts. The other subclade that was separated contained the Polychromophilus sequences from Scotophilus kuhlii from Thailand (MT750305-MT750309). Two samples of parasites of Pipistrellus aff. grandidieri and Laephotis capensis from Guinea (KF159700 and KF159714) formed a separate group.

The subclade of Polychromophilus from vespertilionids was divided into two branches: one contained sequences of P. murinus from bats in Europe (Switzerland, Bulgaria), Madagascar, and Thailand, and a sequence of Eptesicus diminutus (650) from Brazil, and the other clade with M. nigricans from Panama and all the other Brazilian sequences isolated from the Myotis species.

4. Discussion

Based on the results presented herein, although the total number of bat families tested is unknown, Polychromophilus infection in Brazilian bats appears to be limited to just one family (Vespertilionidae). This finding is in accordance with the only previous report of Polychromophilus from Brazil, described as P. deanei, found in Myotis nigricans, also a Vespertilionidae bat [18,19].

According to one study, Paraná state has poor fauna regarding the number of bat species, with only 53 species from five families recorded [31]. The Phyllostomidae family has the highest species richness (25; 47% of the total), followed by Molossidae (13; 24%), Vespertilionidae (12; 22%), Noctilionidae (2; 4%), and Emballonuridae (1; 2.5%) [31]. Miretzki also showed the occurrence of only 55% of the species of the Atlantic Forest biome and the relative predominance of vespertilionids and molossids over phyllostomids. Herein, we analyzed samples obtained from much of the state’s area, with great sampling opportunities for other families. However, we were unable to find Polychromophilus in bat species that were not vespertilionids, suggesting that this parasite may be restricted to this group of bats in Brazil.

Regarding the frequency, we found the lowest positivity rate reported to date, although the total number of samples analyzed herein is one of the highest among published studies (Table 3). This could be related to the sample type analyzed in this study. This was the first time that Polychromophilus DNA was obtained from brain tissue, probably from parasites in the blood vessels that irrigate the organ. Thus, the direct comparison of the prevalence data with published studies that used blood samples is impaired.

Table 3.

Occurrence of Polychromophilus sp. in this study and previous studies worldwide.

Three different Brazilian bats species were found to be positive for Polychromophilus sp.: two Myotis species (M. ruber and M. riparius) and one species from the Eptesicus genus (E. diminutus). There are reports of Myotis species infections in Africa (M. tricolor in Kenya and M. goudoti in Madagascar) [17,36,37], Europe (M. daubentonii and M. myotis in Switzerland) [38], and Asia (M. siligorensis in Thailand) [40]. However, the only record of Polychromophilus infection in Eptesicus comes from Europe (E. serotinus in Switzerland) [38].

Myotis riparius is present in Honduras, Uruguay, Bolivia, Argentina, Paraguay, Trinidad, and Brazil [41], including the state of Paraná [31,42,43]. Myotis ruber is an endangered species under the category of “vulnerable” according to the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources—IBAMA [44], and under the category of “near threatened” at a global level according to IUCN [45]. It is distributed across Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay [40,46,47,48], and southeastern Brazil, including Paraná [49].

It is important to note that in our molecular identification of the host species using cytb and sequence comparisons, Eptesicus furinalis was the species with the best close match with the sequence obtained from bat 650. However, the percentage of identity was low (89%) compared to sequences available in the GenBank® database, making it impossible to identify the species. Thus, alternatively, we used the coi gene and the BOLD database (https://www.boldsystems.org/ (accessed on 31 March 2021), finding 98% of identity with an Eptesicus diminutus sequence, a reliable value for the species identification using the BCM method. Eptesicus diminutus has a distribution in the north and east regions of Paraná state [31]. It is from the Vespertilionidae family, and it is absent from the GenBank® database, which explains the first finding. Thus, we considered specimen 650 to be Eptesicus diminutus.

Our phylogenetic analysis showed a strongly defined clade represented by Plasmodium infecting rodents and primate hosts, which also included Hepatocystis isolated from bats. Similar data were obtained by other authors [38,50]. Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon species were grouped separately in individual clades, as previously shown [51,52].

Regarding Polychromophilus sequences, a similar topology in the phylogenetic tree was obtained by Chumnandee et al. [39], where they grouped into a monophyletic clade with a clear separation of parasites from miniopterid and vespertilionid hosts. Four Brazilian sequences (GenBank® MW984519, MW984520, MW984522 from Polychromophilus sp. isolated of Myotis riparius, and MW984518 from Polychromophilus sp. isolated of Myotis ruber) were positioned close to the sequence of Polychromophilus sp. of bats of the species Myotis nigricans, Vespertilionidae family, from the Latin American region (Panama) (GenBank® #LN483038) [20]. One Brazilian sequence (GenBank® #MW984521, from Polychromophilus isolated from Eptesicus diminutus) was grouped with all P. murinus sequences in a sister clade. The latter, likely P. murinus, presented 1% divergence in the cytb sequence compared to the other Brazilian or Panamanian sequences, and was obtained from a different genus of bats. Thus, the possibility of most Brazilian sequences being a different Polychromophilus species must be investigated.

The present study provides the first molecular description of Polychromophilus parasites in Myotis ruber, Myotis riparius, and Eptesicus diminutus from Brazil and confirms the presence of this parasite 50 years after its first and only report in Brazilian territory. Moreover, our results suggest the occurrence of two distinct Polychromophilus species infecting two different genera of hosts, improving the current knowledge on blood parasites infecting Brazilian bats. However, it is crucial to add additional molecular markers to the phylogenetic analysis for an in-depth investigation. A three-genome phylogenetic analysis for robust haemosporidian phylogenies has been recommended [53] and must be properly included as part of a follow-up paper. Moreover, additional studies including morphological observations of these parasites combined with molecular data are needed to resolve its taxonomy. Furthermore, due to the great Brazilian extensions and the immense diversity of species and biomes, new bat populations should be investigated to provide a complete portrait of the biology of host–parasite interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W.B. and K.K.; formal analysis, B.d.S.M. and C.C.d.A.; investigation, B.d.S.M., L.d.O.G., C.C.d.A. and E.F.M.; resources, G.A.M., I.N.R. and K.K.; data curation, B.d.S.M. and C.C.d.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.d.S.M., A.P.d.S. and K.K.; writing—review and editing, G.A.M., B.d.S.M., I.N.R., L.d.O.G., C.C.d.A., E.F.M., A.P.d.S., A.W.B. and K.K.; visualization, B.d.S.M. and C.C.d.A.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

B.d.S.M. and C.C.d.A. are currently funded by a master scholarship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—CAPES (process numbers 88887.463661/2019-00 and 88887.463659./2019-00). K.K. is a CNPq research fellow (process number 308678/2018-4). L.d.O.G. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship (FAPESP 2018/16232-1). This research benefited from the State Research Institutes Modernization Program, funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 2017/50345-5).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics in Use of Animals Committee, CEUA/SESA, of the Centro de Produção e Pesquisa de Imunobiológicos—CPPI/PR (approval number 01/2019 and date of approval 3 March 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Appendix A and also in the GenBank® database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/ (accessed on 19 March 2021)) (accession numbers MW984518-MW984522).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb) sequences of the parasite used as references for phylogenetic analyses and their respective accession numbers in the Genbank® database.

Table A1.

Mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb) sequences of the parasite used as references for phylogenetic analyses and their respective accession numbers in the Genbank® database.

| GenBank® Accession Number | Parasite Species | Host |

|---|---|---|

| HQ173882 | Eimeria magna | Rabbit |

| HQ173892 | Eimeria vejdovskyi | Rabbit |

| AY099045 | Haemoproteus majoris | Bird |

| HM222472 | Haemoproteus sp. | Bird |

| KT367832, KT367833, KT367822, KT367828 | Haemosporida sp. | Antelope |

| KT367830, KT367819, KT367837 | Haemosporida sp. | Antelope |

| FJ168565 | Hepatocystis sp. | Bat |

| JQ070951, JQ070956 | Hepatocystis sp. | Monkey |

| AY099063 | Leucocytozoon dubreuli | Bird |

| NC_012450, FJ168563 | Leucocytozoon majoris | Bird |

| KF159690, KF159720, MK098843-MK098847 | Nycteria sp. | Bat |

| GQ141581, GQ141585, KT367845, KM598212 | Parahaemoproteus sp. | Bird |

| NC_012447, FJ168561 | Parahaemoproteus vireonis | Bird |

| HM235081 | Plasmodium adleri | Gorilla |

| AY099054, HQ712051 | Plasmodium atheruri | Rodent |

| AY099055 | Plasmodium azurophilum | Lizard |

| KP875474 | Plasmodium billcollinsi | Chimpanzee |

| HM235065 | Plasmodium blacklocki | Gorilla |

| KF159674 | Plasmodium cyclopsi | Bat |

| AB444126 | Plasmodium cynomolgi | Monkey |

| FJ895307 | Plasmodium gaboni | Chimpanzee |

| AF069612 | Plasmodium gallinaceum | Bird |

| AY099053 | Plasmodium giganteum | Lizard |

| JF923751 | Plasmodium gonderi | Mandrill |

| JQ345504 | Plasmodium knowlesi | Human |

| HM000110 | Plasmodium malariae | Chimpanzee |

| GU723548 | Plasmodium ovale | Human |

| JF923762 | Plasmodium praefalciparum | Monkey |

| KP875479 | Plasmodium reichenowi | Chimpanzee |

| AY733090 | Plasmodium relictum | Bird |

| HM222485 | Plasmodium sp. | Bird |

| JF923753 | Plasmodium sp. | Mandrill |

| KJ700853, KJ700854 | Plasmodium vinckei | Rodent |

| KF591834 | Plasmodium vivax | Human |

| KF159671 | Plasmodium voltaicum | Bat |

| DQ414658 | Plasmodium yoelii killicki | Rodent |

Table A2.

Genbank® accession numbers of Polychromophilus mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb) sequences used as a reference for phylogenetic analyses and sequences found in this study.

Table A2.

Genbank® accession numbers of Polychromophilus mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb) sequences used as a reference for phylogenetic analyses and sequences found in this study.

| GenBank Accession Number | Parasite Species | Host | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| KU318045 | P. melanipherus | Anopheles marshallii | Gabon |

| HM055583 | P. murinus | Myotis daubentonii | Switzerland |

| HM055583 | P. murinus | Eptesicus serotinus | Switzerland |

| HM055583 | P. murinus | Nyctalus noctula | Switzerland |

| HM055583 | P. murinus | Myotis myotis | Switzerland |

| HM055584–HM055589 | P. murinus | Myotis daubentonii | Switzerland |

| MW984521 | Polychromophilus sp. | Eptesicus diminutus | Brazil (this study) |

| KT750375 | Polychromophilus sp. | Miniopterus africanus | Kenya |

| MH744509–MH744511, MH744518, MH744521 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus gleni | Madagascar |

| MH744506, MH744519 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus griffithsi | Madagascar |

| MH744514–MH744516 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus griveaudi | Madagascar |

| MH744508, MH744522–MH744525 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus griveaudi | Madagascar |

| JQ995284–JQ995288 | Polychromophilus sp. | Miniopterus inflatus | Gabon |

| MH744504, MH744505 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus mahafaliensis | Madagascar |

| MH744512, MH744526 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus manavi | Madagascar |

| KT750430 | Polychromophilus sp. | Miniopterus minor | Tanzania |

| MK098848, MK098849 | Polychromophilus sp. | Miniopterus minor | Gabon |

| MW007677 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus natalensis | South Africa |

| KT750376-KT750382, KT750401, KT750402 | Polychromophilus sp. | Miniopterus natalensis | Kenya |

| KT750406, KT750408, KT750409 | Polychromophilus sp. | Miniopterus natalensis | Kenya |

| MK088162–MK088168 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus orianae | Australia |

| KT750383-KT750386, KT750415, KT750418 | Polychromophilus sp. | Miniopterus rufus | Kenya |

| JN990708–JN990711 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus schreibersii | Switzerland |

| KJ131270–KJ131277 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus schreibersii | Southern and Central Europe |

| MW007689 | P. melanipherus | Miniopterus schreibersii | Spain |

| KT750389 | Polychromophilus sp. | Miniopterus sp. | Tanzania |

| KT750387 | Polychromophilus sp. | Miniopterus sp. | Kenya |

| KF159675, KF159681, KF159699 | Polychromophilus sp. | Miniopterus villiersi | Guinea |

| JN990712, JN990713 | P. murinus | Myotis daubentonii | Switzerland |

| MH744532–MH744536 | P. murinus | Myotis goudoti | Madagascar |

| LN483038 | Polychromophilus sp. | Myotis nigricans | Panamá |

| MW984519, MW984520, MW984522 | Polychromophilus sp. | Myotis riparius | Brazil (this study) |

| MW984518 | Polychromophilus sp. | Myotis ruber | Brazil (this study) |

| MT136168 | P. murinus | Myotis siligorensis | Thailand |

| KF159700 | Polychromophilus sp. | Neoromicia capensis | Guinea |

| MW007685 | P. melanipherus | Nycteribia schmidlii | Spain |

| MW007680, MW007681 | P. melanipherus | Nycteribia schmidlii | Hungary |

| MW007682 | P. melanipherus | Nycteribia schmidlii | Italy |

| MW007671–MW007674, MW007676 | P. melanipherus | Nycteribia schmidlii scotti | South Africa |

| KU182361–KU182367 | P. melanipherus | Nycteribia schmidlii scotti | Gabon |

| MH744527 | P. melanipherus | Nycteribia stylidiopsis | Madagascar |

| MH744520 | P. melanipherus | Paratriaenops furculus | Madagascar |

| KU182368 | P. melanipherus | Penicillidia fulvida | Gabon |

| MH744528–MH744531 | P. melanipherus | Penicillidia leptothrinax | Madagascar |

| MH744537 | P. murinus | Penicillidia sp. | Madagascar |

| KF159714 | Polychromophilus sp. | Pipistrellus aff. grandidieri | Guinea |

| LN483036 | P. murinus | Rhinolophus sp. | Bulgaria |

| MT750305–MT750309 | Polychromophilus sp. | Scotophilus kuhlii | Thailand |

| MT136167 | P. melanipherus | Taphozous melanopogon | Thailand |

References

- Morrison, D.A.; Bornstein, S.; Thebo, P.; Wernery, U.; Kinne, J.; Mattsson, J.G. The current status of the small subunit rRNA phylogeny of the coccidia (Sporozoa). Int. J. Parasitol. 2004, 34, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.B.; Tham, W.H.; Cowman, A.F.; Mcfadden, G.I.; Waller, R.F. Alveolins, a new family of cortical proteins that define the protist infrakingdom Alveolata. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008, 25, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.S.; Grant, J.; Tekle, Y.I.; Wu, M.; Chaon, B.C.; Cole, J.C.; Logsdon, J.M., Jr.; Patterson, D.J.; Bhattacharya, D.; Katz, L.A. Broadly sampled multigene trees of eukaryotes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donoghue, P. Haemoprotozoa: Making biological sense of molecular phylogenies. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2017, 6, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, I.; Chavatte, J.M.; Karadjian, G.; Chabaud, A.; Beveridge, I. The Haemosporidian parasites of bats with description of Sprattiella alecto gen. nov., sp. nov. Parasite 2012, 19, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, S.L.; Schaer, J. A modern menagerie of mammalian malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2016, 32, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landau, I.; Baccam, D.; Ratanaworabhan, N.; Yenbutra, S.; Boulard, Y.; Chabaud, A.G. Nouveaux Haemoproteidae parasites de Chiroptères en Thailande [New Haemoproteidae parasites of Chiroptera in Thailand]. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 1984, 59, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witsenburg, F.; Salamin, N.; Christe, P. The evolutionary host switches of Polychromophilus: A multi-gene phylogeny of the bat malaria genus suggests a second invasion of mammals by a haemosporidian parasite. Malar. J. 2012, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisi, A. Les parasites endoglobulaires des chauves-souris. Atti Reale Acad. Lincei 1898, 7, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Dionisi, A. Un parassita del globulo rosso in una specie di pipistrello (Miniopterus Schreibersii Kuhl). Atti Reale Acad. Lincei 1898, 7, 214–215. [Google Scholar]

- Garnham, P.C.C. Polychromophilus species in insectivorous bats. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1973, 67, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnham, P.C.C. The zoogeography of Polychromophilus and description of a new species of a gregarine (Lankesteria galliardi). Ann. Parasitol. 1973, 48, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Landau, I.; Rosin, G.; Miltgen, F. The genus Polychromophilus (Haemoproteidae, parasite of Microchiroptera). Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 1980, 55, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnham, P.C.C. Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporidia; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Schaer, J.; Perkins, S.L.; Decher, J.; Leendertz, F.H.; Fahr, J.; Weber, N.; Matuschewski, K. High diversity of West African bat malaria parasites and a tight link with rodent Plasmodium taxa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 43, 17415–17419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaer, J.; Perkins, S.L.; Ejotre, I.; Vodzak, M.E.; Matuschewski, K.; Reeder, D.M. Epauletted fruit bats display exceptionally high infections with a Hepatocystis species complex in South Sudan. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, H.L.; Patterson, B.D.; Kerbis Peterhans, J.C.; Stanley, W.T.; Webala, P.W.; Gnoske, T.P.; Hackett, S.J.; Stanhope, M.J. Diverse sampling of East African haemosporidians reveals chiropteran origin of malaria parasites in primates and rodents. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 99, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnham, P.C.C.; Lainson, R.; Shaw, J.J. A malaria-like parasite of a bat from Brazil. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1970, 64, 13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garnham, P.C.C.; Lainson, R.; Shaw, J.J. A contribution to the study of the haematozoon parasites of bats. A new mammalian haemoproteid, Polychromophilus deanei n. sp. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1971, 69, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borner, J.; Pick, C.; Thiede, J.; Kolawole, O.M.; Kingsley, M.T.; Schulze, J.; Cottontail, V.M.; Wellinghausen, N.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Bruchhaus, I.; et al. Phylogeny of haemosporidian blood parasites revealed by a multi-gene approach. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 94, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.L.; Schall, J.J. A molecular phylogeny of malarial parasites recovered from cytochrome b gene sequences. J. Parasitol. 2002, 88, 972–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A. FigTree: Tree Figure Drawing Tool Version 1.4.0; Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kocher, T.D.; Thomas, W.K.; Meyer, A.; Edwards, S.V.; Pääbo, S.; Villablanca, F.X.; Wilson, A.C. Dynamics of mitochondrial DNA evolution in animals: Amplification and sequencing with conserved primers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 6196–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, R.; Shiyang, K.; Vaidya, G.; Ng, P.K.L. DNA barcoding and taxonomy in Diptera: A tale of high intraspecific variability and low identification success. Syst. Biol. 2006, 55, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, N.V.; de Waard, J.R.; Hebert, P.D.N. An inexpensive, automation-friendly protocol for recovering high-quality DNA. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2006, 6, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.D.; Zemlak, T.S.; Innes, B.H.; Last, P.R.; Hebert, P.D.N. DNA barcoding Australia’s fish species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 1847–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, A. DNA barcoding of the Indian blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra) and their correlation with other closely related species. Egypt J. Forensic. Sci. 2017, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, F.; Linton, Y.M.; Ponsonby, D.J.; Conn, J.E.; Herrera, M.; Quiñones, M.L.; Vélez, I.D.; Wilkerson, R.C. Molecular comparison of topotypic specimens confirms Anopheles (Nyssorhynchus) dunhami Causey (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Colombian Amazon. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2010, 105, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miretzki, M. Morcegos do Estado do Paraná, Brasil (Mammalia, Chiroptera): Riqueza de espécies, distribuição e síntese do conhecimento atual. Pap. Avulsos Zool. 2003, 43, 101–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, P.H.; Lumsden, L.F.; Legione, A.R.; Hufschmid, J. Polychromophilus melanipherus and haemoplasma infections not associated with clinical signs in southern bent-winged bats (Miniopterus orianae bassanii) and eastern bent-winged bats (Miniopterus orianae oceanensis). Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2018, 8, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witsenburg, F.; Clément, L.; López-Baucells, A.; Palmeirim, J.; Pavlinić, I.; Scaravelli, D.; Ševčík, M.; Dutoit, L.; Salamin, N.; Goudet, J.; et al. How a haemosporidian parasite of bats gets around: The genetic structure of a parasite, vector and host compared. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 926–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, L.; Mejean, C.; Maganga, G.D.; Makanga, B.K.; Mangama Koumba, L.B.; Peirce, M.A.; Ariey, F.; Bourgarel, M.; Bourgarel, M. The chiropteran haemosporidian Polychromophilus melanipherus: A worldwide species complex restricted to the family Miniopteridae. Infec. Genet. Evol. 2012, 12, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosskopf, S.P.; Held, J.; Gmeiner, M.; Mordmüller, B.; Matsiégui, P.; Eckerle, I.; Weber, N.; Matuschewski, K.; Schaer, J. Nycteria and Polychromophilus parasite infections of bats in Central Gabon. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 68, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramasindrazana, B.; Goodman, S.M.; Dsouli, N.; Gomard, Y.; Lagadec, E.; Randrianarivelojosia, M.; Dellagi, K.; Tortosa, P. Polychromophilus spp. (Haemosporida) in Malagasy bats: Host specificity and insights on invertebrate vectors. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoanoro, M.; Goodman, S.M.; Randrianarivelojosia, M.; Rakotondratsimba, M.; Dellagi, K.; Tortosa, P.; Ramasindrazana, B. Diversity, distribution, and drivers of Polychromophilus infection in Malagasy bats. Malar. J. 2021, 20, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megali, A.; Yannic, G.; Christe, P. Disease in the dark: Molecular characterization of Polychromophilus murinus in temperate zone bats revealed a worldwide distribution of this malaria-like disease. Mol. Ecology 2011, 20, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chumnandee, C.; Pha-obnga, N.; Werb, O.; Matuschewski, K.; Schaer, J. Molecular characterization of Polychromophilus parasites of Scotophilus kuhlii bats in Thailand. Parasitology 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnuphapprasert, A.; Riana, E.; Ngamprasertwong, T.; Wangthongchaicharoen, M.; Soisook, P.; Thanee, S.; Bhodhibundit, P.; Kaewthamasorn, M. First molecular investigation of haemosporidian parasites in Thai bat species. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2020, 13, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, N.R.; Peracchi, A.L.; Pedro, W.A.; Lima, I.P. Morcegos do Brasil; Nélio, R. Reis: Londrina, Brazil, 2007; p. 253. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiama, M.L.; Reis, N.R.; Peracchi, A.L.; Rocha, V.J. Morcegos do Parque Nacional do Iguaçu, Paraná (Chiroptera, Mammalia). Rev. Bras. Zool. 2001, 18, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bianconi, G.V.; Mikich, S.B.; Pedro, W.A. Diversidade de morcegos (Mammalia, Chiroptera) em remanescentes florestais do município de Fênix, noroeste do Paraná, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Zool. 2004, 21, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.B.M.; Martins, C.S.; Drummond, G.M. Lista da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção: Incluindo a Lista de Espécies Quase Ameaçadas e Deficientes em Dados; Fundação Biodiversitas: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2005; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2021.1. 2019. Available online: http://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Barquez, R.M.; Mares, M.A.; Braun, J.K. The bats of Argentina. Spec. Publ. Texas Tech Univ. 1999, 42, 1–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Gonzalez, C.; Presley, S.J.; Owen, R.D.; Willig, M.R. Taxonomic status of Myotis (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in Paraguay. J. Mammal. 2001, 82, 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achaval, F.; Clara, M.; Olmos, A. Mamiferos de la Republica Oriental del Uruguay; Biophoto: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2008; p. 213. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M.M.; Terribile, L.C.; Caceres, N.C. Potential geographic distribution of Myotis ruber (Chiroptera, Vespertilionidae), a threatened Neotropical bat species. Mammalia 2010, 74, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, M.I.; Ghai, R.R.; Hyeroba, D.; Weny, G.; Tumukunde, A.; Chapman, C.A.; Wiseman, R.W.; Dinis, J.; Steeil, J.; Greiner, E.C.; et al. Co-infection and cross-species transmission of divergent Hepatocystis lineages in a wild African primate community. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013, 43, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinsen, E.S.; Paperna, I.; Schall, J.J. Morphological versus molecular identification of avian Haemosporidia: An exploration of three species concepts. Parasitology 2006, 133, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanbakht, H.; Kvičerová, J.; Dvořáková, N.; Mikulíček, P.; Sharifi, M.; Kautman, M.; Maršíková, A.; Široký, P. Phylogeny, Diversity, Distribution, and Host Specificity of Haemoproteus spp. (Apicomplexa: Haemosporida: Haemoproteidae) of Palaearctic Tortoises. J. Eukaryot Microbiol. 2015, 62, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, E.S.; Perkins, S.L.; Schall, J.J. A three-genome phylogeny of malaria parasites (Plasmodium and closely related genera): Evolution of life-history traits and host switches. Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 2008, 47, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).