Abstract

Thalassogenic diseases are human infections associated with exposure to marine environments. This review explores the occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Blastocystis sp. in seawater and shellfish and their implications for public health. Between 2015 and 2026, multiple studies reported the presence of these parasites in shellfish and seawater. Cryptosporidium spp. was found at average concentrations of 5.5 × 101 oocysts/g in shellfish and up to 3.7 × 101 oocysts/L in seawater. Giardia duodenalis reached 9.1 × 101 cysts/g in shellfish, close to the infectious dose, and 3.5 × 101 cysts/L in seawater. Blastocystis sp. showed prevalence rates of 33.82% in shellfish and 17.3% in seawater. These findings highlight a potential infection risk for bathers and seafood consumers, emphasizing the need to determine the specific species (or subtypes) involved and assess their viability to accurately evaluate public health implications. The persistence of these parasites in the environment needs improved monitoring. Future strategies should integrate next-generation sequencing (NGS) or use of various fecal indicators to enhance environmental surveillance and reduce health risks in coastal regions.

1. Introduction

Climate change is redesigning coastal ecosystems through rising sea temperatures, altered precipitation, and tidal changes, creating favorable conditions for the persistence and transmission of waterborne protozoan parasites [1,2]. These changes compromise seawater quality and increase human exposure risks via recreational activities and shellfish consumption [3,4].

Thalassogenic diseases, illnesses associated with marine environments, are responsible for over 120 million cases of gastroenteritis annually and 4 million cases of hepatitis A and E, with 40,000 deaths and permanent disabilities [5,6,7]. These diseases are strongly linked to microbial contamination of seawater, primarily caused by the discharge of untreated or inadequately treated sewage into marine ecosystems [3,4,8]. Protozoa such as Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Blastocystis sp. are of particular concern due to their capacity to cause gastrointestinal outbreaks. Between 2017 and 2022, 416 parasitic outbreaks were reported, with 75.2% linked to recreational water exposure and Cryptosporidium accounting for 77.4% [3].

These protozoan parasites represent a substantial global health burden, being associated with approximately 1.7 billion episodes of diarrhea and 842,000 deaths annually [9]. Their impact is particularly pronounced among children under five years of age and immunocompromised individuals, such as those living with HIV [10]. Infections can present a wide clinical spectrum, ranging from self-limiting acute diarrhea to persistent or chronic forms [10,11,12]. Furthermore, these organisms have been implicated as etiological agents in other conditions, including malabsorption syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, cutaneous allergic reactions, and, in the case of Cryptosporidium spp., a potential link to colorectal cancer [9,10,11].

Despite growing evidence of protozoan presence in marine environments, their role in thalassogenic diseases remains underexplored, partly due to limitations in detection methods and biological factors that hinder diagnosis. Advancing and developing sensitive detection techniques, while integrating microbial indicators such as Enterococcus spp. with environmental parameters, is strongly recommended to improve surveillance and risk assessment. International guidelines, including those from WHO, emphasize the enumeration of Enterococcus in seawater [13]; however, this indicator has not been consistently adopted in some countries, such as Chile [14].

This article synthesizes current scientific knowledge on waterborne protozoan parasites in marine environments, emphasizing their role in thalassogenic diseases, detection methodologies, and the use of microbial indicators to support public health strategies.

2. Bibliometric Analysis

A comprehensive literature review was conducted using the Web of Science (WoS) database, focusing exclusively on peer-reviewed scientific articles published between 2015 and 2026. The search strategy incorporated the keywords “waterborne parasite”, “Cryptosporidium”, “Giardia”, and “Blastocystis”, in combination with the terms “shellfish”, “bivalve”, “clams”, “mussels”, “oyster”, “seawater”, and “coastal”. These terms were systematically combined across multiple search queries to optimize the retrieval of relevant publications. The search was refined to include only studies reporting the detection of parasites in marine environments, specifically in shellfish intended for human consumption and or seawater. Articles focusing on shellfish from estuarine or freshwater environments were excluded.

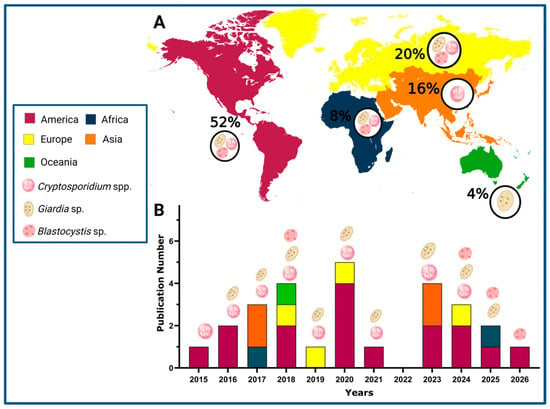

A total of 25 articles were identified between 2015 and 2026 that reported the detection of waterborne parasites in marine environments (shellfish for human consumption and seawater) [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Figure 1 illustrates the geographical (Figure 1A) and annual (Figure 1B) distribution of scientific publications between 2015 and 2026. The Americas accounted for the highest proportion of studies (52%), particularly during 2018, 2020, and 2024. Europe and Asia also demonstrated substantial research activity, contributing 20% and 16% of the total publications, respectively, with notable increases in 2019 and 2023. Africa and Oceania contributed fewer studies, representing 8% and 4% of the total, respectively, although their presence remained consistent throughout the study period. The overall trend in publication volume was variable, with prominent peaks observed in 2018, 2020 and 2023.

Figure 1.

Geographical and temporal distribution of scientific publications on parasite detection in marine environment (2015–2026). (A) Percentage of geographical distribution by continents. (B) Temporal distribution (Created in https://Biorender.com, 10 October 2025).

Figure 1 also highlights the detection of Cryptosporidium spp. in 76%, Giardia sp. in 48%, and Blastocystis sp. in 16%. It is worth noting that the three parasites have been investigated in studies conducted across the Americas, Europe, and Africa. In contrast, research from Oceania and Asia has predominantly reported the presence of Cryptosporidium spp. These results reflect an increasing global focus on monitoring parasitic contamination in marine environments. Notably, Blastocystis sp. has gained particular attention in recent years, emphasizing its emerging relevance in marine parasitology and public health surveillance (Figure 1B).

3. Waterborne Parasite and Thalassogenic Disease

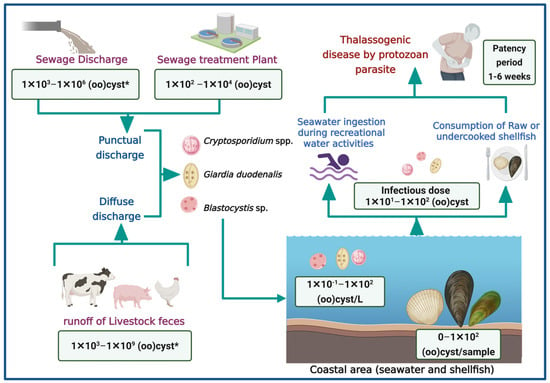

Figure 2 illustrates the main pathways through which Cryptosporidium spp., G. duodenalis, and Blastocystis sp. contaminate coastal waters, contributing to thalassogenic diseases. It highlights two primary sources of contamination: punctual and diffuse discharges of sewage discharges from sewage treatment plants and runoff from livestock feces [18,32,33,38,39,40]. These contaminants reach coastal zones, where they pose health risks through accidental ingestion during recreational water activities or via consumption of raw or undercooked shellfish.

Figure 2.

Pathways of waterborne parasite contamination in marine environment and associated health risk (Created in https://BioRender.com, 10 October 2025). (*): quantification in raw feces.

It has been demonstrated that the concentration of (oo)cysts in human feces varies between 1 × 102 and 1 × 106 (oo)cyst/g [36,37]. Consequently, untreated sewage may reach similar concentrations. Furthermore, these parasites have been reported to exhibit resistance to chlorination and UV radiation disinfection, potentially allowing up to 1 × 104 (oo)cysts to persist in treated effluents [41,42]. These discharges may significantly contribute to the presence of parasites in coastal environments. Given the zoonotic nature of many of these parasites, poor management of animal feces in extensive or subsistence livestock systems also plays a role in environmental contamination [43]. For instance, an animal infected with Cryptosporidium may excrete up to 1 × 109 oocysts/g of feces [41,43]. The concentration of (oo)cysts in seawater and shellfish ranges from 0 to 1 × 102, indicating a potential risk of infection for bathers or consumers [44].

Although there is limited information regarding outbreaks associated with recreational activities in marine waters or the consumption of shellfish, this gap may be attributed to several challenges inherent to waterborne parasitic infections. First, the incubation and patency period of these parasites is often prolonged defined as the interval between ingestion of the infective stage and the onset of symptoms, which can extend over several weeks, complicating the ability to establish a direct link between shellfish consumption and clinical manifestations (Figure 2) [45,46]. Parasites may remain detectable in clinical samples for extended periods, yet diagnostic techniques such as stool examinations require patients to be in the acute phase of infection to visualize parasitic elements effectively [41,45,46,47]. Given the detection threshold of approximately 1 × 104 cysts/g, this leads to underreporting [47]. Finally, the absence of pathognomonic signs further hinders diagnosis, as these parasites typically do not produce specific or distinctive symptoms. Consequently, patients may receive only symptomatic treatment for sporadic diarrhea without etiological identification, potentially resulting in chronic infections or more severe clinical outcomes depending on the host’s immune status, nutritional condition, and age [41,45,46,47].

These factors may interfere with the integration of clinical and environmental data, limiting the ability to trace the origin of infections. Therefore, when reviewing a patient’s clinical history, it is essential to inquire about recent consumption of raw shellfish or exposure to coastal waters, even if such activities occurred up to two weeks prior. In suspected cases, parasitological analysis, particularly direct observation, should be included, as acute diarrheal episodes are associated with higher concentrations of (oo)cysts in feces (often exceeding 1 × 106 (oo)cysts/g), increasing detection.

In this context, monitoring protozoan parasites in marine environments becomes a valuable tool for early warning systems, enabling timely public health interventions and outbreak mitigation strategies.

4. Methodological Approaches for the Detection of Waterborne Protozoan Parasites in Shellfish and Aquatic Environments

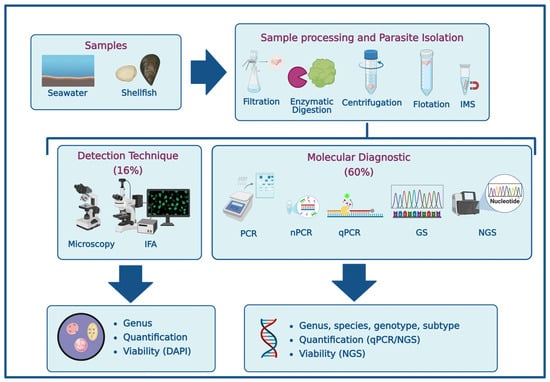

Among the 25 scientific articles reviewed, a wide range of detection methods was reported [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Despite the growing availability of advanced molecular tools, microscopy remains a relevant and widely used screening technique for protozoan parasites in environmental samples. As shown in Figure 3, 16% of the studies relied solely on microscopic methods, such as optical microscopy (20%) and immunofluorescence assays (IFA, 40%), while 60% employed molecular techniques and 24% combined both approaches. Conventional PCR and nested PCR (nPCR) were the most frequently used molecular methods (68%), followed by gene sequencing (64%) and quantitative PCR (qPCR, 32%). Notably, only one study utilized Oxford Nanopore sequencing technology [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38].

Figure 3.

Methodological approaches for the detection of waterborne protozoan parasites in marine environments (Created in https://BioRender.com, 10 October 2025). [IMS]: Immunomagnetic separation; [IFA]: Immunofluorescence assay; [PCR]: Polymerase chain reaction; [nPCR]: nested PCR; [qPCR]: quantitative PCR; [GS]: Gene sequencing; [NGS]: Next-generation sequencing; [DAPI]: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Detection strategies varied depending on the biological matrix (e.g., shellfish tissue vs. seawater), the target organism, and the analytical resolution required (e.g., presence/absence vs. species or genotype identification). Importantly, shellfish such as clams, mussels, and oysters not only act as potential transmission vectors but also serve as bioindicators of marine water quality, concentrating protozoan (oo)cysts from surrounding waters and thereby facilitating environmental surveillance [48,49,50,51].

4.1. Sample Processing and Parasite Isolation

In shellfish, parasite recovery typically involves mechanical or enzymatic disruption of digestive tissues, followed by concentration and purification steps. Common techniques include:

- •

- Filtration: Membranes with 0.2 µm pore sizes retain protozoan (oo)cysts (0.2–20 µm). Polycarbonate and cellulose nitrate membranes are selected based on charge compatibility with Cryptosporidium oocysts and downstream molecular applications [48,52].

- •

- Enzymatic digestion: Pepsin or proteinase K is used to release (oo)cysts from lipid and glycoprotein-rich tissues, which may interfere with detection. Hemolymph components can also affect immunofluorescence assays due to background fluorescence [48,49,51,53].

- •

- Centrifugation and flotation: Cesium chloride gradients improve (oo)cyst recovery compared to sucrose, though both may coextract similar density particles [48].

- •

- Immunomagnetic separation (IMS): Applied mainly for Cryptosporidium and Giardia, IMS uses monoclonal antibodies to isolate (oo)cysts, with better performance in water samples due to lower matrix complexity [48,49].

Ligda et al. [49] reported recovery rates of 32.1% for Giardia and 61.4% for Cryptosporidium in Mytilus galloprovincialis using pepsin digestion and IMS, with a detection limit of 10 (oo)cysts/g. Bigot-Clivot et al. [50] showed that M. edulis bioaccumulates these parasites for up to 21 days post-depuration, supporting its use as a sentinel species. Shellfish serve both as transmission vectors and bioindicators, concentrating protozoan (oo)cysts from surrounding waters and enabling integrated food safety and environmental monitoring [49,50].

In seawater, isolation methods include membrane filtration for environmental DNA, ultrafiltration and PEG precipitation for parasite concentration, and modified CTAB protocols for nucleic acid extraction with inhibitor removal [54].

The concentration of parasitic protozoa in environmental samples, such as water or shellfish, is low (generally <100 (oo)cysts) [48]. Moreover, the presence of interfering substances in these matrices could be compromise downstream analyses, including PCR [48,49,50]. Sample processing and isolation methods may be applied individually or in combination, depending on matrix characteristics [51]. For instance, Kim et al. [51] reported that, for detecting parasites in shellfish, immunomagnetic separation (IMS) significantly enhances sensitivity, enabling detection of fewer than 10 oocysts per tissue for both C. parvum and G. duodenalis. Additionally, incorporating enzymatic digestion further improves sensitivity, reaching levels as low as 5 oocysts/tissue [48,51,53].

4.2. Detection Techniques

Detection of waterborne protozoa typically begins with:

- •

- Microscopy: Techniques such as Ziehl–Neelsen staining, DAPI fluorescence, and differential interference contrast allow genus-level identification and viability assessment, though sensitivity is limited and influenced by sample quality [47].

- •

- IFA: Monoclonal antibodies conjugated to fluorophores are used for species-level identification and quantification [47,48,50].

While microscopy remains a classical tool for preliminary screening, its limitations are evident in marine matrices [48,49,50,51]. Interfering substances in seawater and shellfish can lead to false positives or negatives, and low parasite concentrations (often ~102 oocysts) fall below the detection threshold of conventional microscopy (~104 oocysts), potentially resulting in underestimation of contamination levels. Its importance of selecting appropriate sample preparation and detection techniques based on the matrix and target parasite [50].

4.3. Molecular Diagnostics and Target Genes

Molecular techniques offer high sensitivity and specificity, detecting as few as 1–5 (oo)cysts/sample [55]. Common methods include:

- •

- Conventional PCR: Genus-level detection.

- •

- nPCR: Enhanced sensitivity for species/subtype identification.

- •

- qPCR: Real-time detection and quantification.

- •

- Target Gene Sequencing: Subtype confirmation.

Frequently targeted genes include gp60 and COWP for Cryptosporidium, β-giardin, gdh, and tpi for G. duodenalis, and SSU rRNA for Blastocystis subtype identification [47,56,57]. Although molecular methods reduce subjectivity, challenges remain due to matrix inhibitors and mixed infections. In this context, molecular technologies offer enhanced sensitivity and improved specificity, given that their performance does not rely on the subjective interpretation of the technician [47,55]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies offer improved resolution for complex samples [58].

4.4. Next-Generation Sequencing

Detecting protozoan pathogens in aquatic environments is challenging due to their low abundance, genetic diversity, and complex sample matrices. In this context, next-generation sequencing (NGS), particularly 18S rRNA metabarcoding and shotgun metagenomics, has emerged as a powerful tool for environmental and food safety surveillance [58,59,60,61,62].

DeMone et al. [59] developed a metabarcoding assay targeting the V4 region of the 18S rRNA gene for detecting Cryptosporidium parvum, Giardia enterica, and other protozoa in oysters. While the assay enabled multi species detection and showed higher sensitivity than conventional PCR in tissue samples, host DNA interference reduced its performance, especially for Giardia in hemolymph. Mitigation strategies included pepsin-HCl digestion and synthetic gBlocks.

Although NGS has not yet been applied to marine water for protozoan detection, studies in sewage environments demonstrate its utility. Zahedi et al. [60] used 18S rRNA metabarcoding and targeted NGS to analyze samples from sewage treatment plants in Australia. General 18S NGS detected Blastocystis sp., while targeted assays identified nine Cryptosporidium species, including five zoonotic types. A broader survey across 25 treatment plants revealed 17 Cryptosporidium species and six genotypes, with oocyst concentrations ranging from 7.0 × 101 to 1.8 × 104 oocysts/L, highlighting spatial and seasonal diversity [60,61].

In South Africa, Mthethwa et al. [62] applied 18S rRNA amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics to treated and untreated sewage. They identified Cryptosporidium spp. (3.48%), Blastocystis sp. (2.91%), and Giardia intestinalis (0.31%), along with virulent genes and metabolic pathways, suggesting protozoan viability within treatment systems.

In summary, NGS enables sensitive, multi-target detection and functional profiling of protozoan parasites. While its application is limited by cost, technical complexity, and host DNA interference, it complements conventional methods and enhances microbial risk assessment when combined with optimized sample preparation strategies [58,59,60,61,62].

5. Fecal Indicators in Seawater Associated with Waterborne Parasite

Due to the complexity and cost of targeted parasitological diagnostics, microbial indicators offer a practical alternative for preliminary assessment of protozoan contamination in seawater. Table 1 summarizes commonly used indicators, including Escherichia coli, Enterococcus spp., total and thermotolerant coliforms, Clostridium perfrigens, bacteriophages, and Pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV), with the latter used in microbial source tracking [8,31,33,63,64,65,66].

Table 1.

Fecal indicator for assessing microbiological quality of seawater and their association with the presence of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia sp.

While correlations between bacterial indicators and protozoa have been explored in freshwater and sewage systems, results are inconsistent. In marine environments, a two-year study on Brazilian beaches found no significant correlation between bacterial indicators and the presence of Cryptosporidium spp. or Giardia sp. (Pearson’s p ≤ 0.05). Parasite concentrations varied seasonally, with Cryptosporidium ranging from 2.1 to 7 oocysts/L and Giardia from 5.7 to 9.3 cysts/L, while bacterial counts were generally lower during parasite detection periods [33].

In contrast, Graczyk et al. [8] reported strong positive correlations between Enterococcus spp. and both C. parvum (R = 0.95; p < 0.01) and G. duodenalis (R = 0.71; p = 0.018) in recreational marine waters, suggesting its potential as a predictive marker.

González-Fernández et al. [31] linked microbial indicators with environmental parameters such as rainfall, temperature, and salinity. In Costa Rica, Cryptosporidium was detected in 33% and Giardia in 11% of samples during the rainy season, associated with temperatures of 27–28.8 °C and salinities of 27.6–31.4 ppt. Turbidity showed no correlation.

Among all indicators, Enterococcus spp. showed the highest predictive value for protozoan presence, with reported sensitivity of 88%, specificity of 93%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 78%, and negative predictive value (NPV) of 96% [31].

Anaerobic sulphite-reducing Clostridia, particularly Clostridium perfringens spores, have been proposed as useful surrogate indicators for the presence or persistence of Cryptosporidium oocysts in water (Table 1). Their resistance to environmental stressors and disinfection processes parallels that of protozoan (oo)cysts, making them valuable for assessing treatment efficacy and potential contamination risks. Several studies have demonstrated correlations between C. perfringens counts and the occurrence or removal of protozoan pathogens, including Cryptosporidium [63,64,65,66]. However, while C. perfringens spores can indicate the potential for contamination by similarly resistant microorganisms, they should be regarded as surrogate or complementary indicators, not direct markers of Cryptosporidium presence.

The measurement of bacterial indicators, as presented in Table 1, is commonly performed through culture-based methods followed by quantification (by MPN). This approach offers several advantages over routine parasitological detection techniques. Bacterial culturing is relatively simple, cost-effective, and widely standardized, making it more accessible for routine monitoring programs. In contrast, the detection of protozoan parasites such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia typically requires molecular techniques that are more complex, expensive, and technically demanding, often involving specialized equipment and trained personnel.

Given their simplicity and cost-effectiveness, bacterial indicators quantified via culture-based methods are suitable for routine monitoring. While not definitive, they provide a useful screening tool to guide targeted parasitological analyses, especially during high-risk periods such as summer or in shellfish harvesting areas. In such contexts, water monitoring should precede parasite detection, and shellfish intended for consumption should undergo microscopic examination for parasitic stages.

6. Waterborne Protozoan Parasites in Marine Environment

Several studies have confirmed the presence of waterborne parasites in marine environments, particularly in shellfish intended for human consumption and seawater [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. These studies have analyses various species of clams, including Mya arenaria, M. truncata, and Ruditapes decussatus; mussels such as Aulacomya atra, Geukensia demissa, Mytilus spp., M. edulis, M. galloprovincialis, Perna canaliculus, P. perna and P. viridis; and oysters belonging to the genera Crassostrea spp., Crassostrea virginica, C. belcheri, C. lugubris C. iredalei, Pinctada radiata, Argopecten irradians, Saccostrea forskali and Venerupis philippinarum. Table 2 provides a summary of findings related to the detection of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Blastocystis sp. in marine environmental between 2015 and 2026.

Table 2.

Evidence of Waterborne parasites in shellfish and seawater (2015–2026).

Cryptosporidium spp. has been identified in shellfish intended for human consumption, with multiple species and subtypes reported, including C. hominis (IbA10G2R2), C. parvum (IaA15G2R1), C. meleagridis and C. andersoni [15,16,17,18]. Among the identified species, C. hominis subtype IbA10G2R2 (classified based on the gp60 gene) has been exclusively detected in humans [57]. Additionally, C. parvum and C. meleagridis are recognized as zoonotic species [41]. Notably, C. parvum subtype IaA15G2R1 is the most frequently reported subtype associated with outbreaks linked to contaminated water and food, with transmission routes involving both animal and human fecal contamination [57]. As shown in Table 2, the average concentration of oocysts detected in shellfish samples was 5.5 × 101 oocysts/sample. Infective doses for Cryptosporidium spp. have been reported to range between 1 × 101 and 1 × 102 oocysts [41]. This implies a potential health risk for the population, as the number of oocysts found in shellfish falls within the infective dose range for this parasite. Prevalence rates varied significantly depending on the detection technique adopted. Microscopic techniques yielded an average prevalence of 24.5%, meanwhile molecular techniques reported a lower average prevalence of 10.53% (Table 2). In seawater samples, C. parvum was predominant species detected, with concentrations reaching up to 3.7 × 101 oocyst/L. Prevalence in seawater average 19% using microscopic methods and approximately 10% when assessed by molecular techniques [29,30,31,32].

Regarding G. duodenalis, assemblages A, AI, AII, B, C, and D have been identified in shellfish. Assemblages A and B are considered zoonotic, yet they have also been observed in humans at rates of 64% and 72%, respectively [67]. In contrast, assemblages C and D are primarily associated with canine hosts, with detection rates of 87% and 94%, respectively [41]. As shown in Table 2, the prevalence of G. duodenalis in shellfish ranged from 7%. Notably, concentrations in shellfish reached up to 9.1 × 101 cysts/g. Regarding its detection in seawater, assemblage AII has been identified, with mean concentrations of 3.5 × 101 cyst L−1 and prevalence rates 21%. In shellfish, the reported concentration exceeds the infectious dose for this parasite, estimated to range between 1 × 101 and 1 × 102 cyst [41].

Blastocystis sp. has been detected in shellfish with a wide diversity of subtypes, including ST3, ST7, ST14, ST23, ST26, and ST44 [18,34,35,36]. In seawater samples, subtypes ST1, ST2, ST3, and ST10a have been identified [37,38]. Although Blastocystis sp. is considered zoonotic, subtypes ST1–ST9 are frequently found in humans, with ST3, ST1, and ST2 being the most prevalent, accounting for over 90% of cases [68,69]. In contrast, subtypes ST7, ST10, ST14, ST23, and ST26 are more commonly associated with animal hosts such as birds, dogs, cattle, pigs, and sheep, with prevalence rates ranging from 50% to 90% in these animals [68]. These findings may suggest both point-source and diffuse fecal contamination in the areas where the studies were conducted. Although quantitative concentrations were not reported, prevalence rates reached 34% in shellfish and 17% in seawater [18,34,35,36,37,38].

As shown in Table 2, the identification of parasitic species is essential for determining the source of fecal contamination; nevertheless, it is a process that relies on molecular techniques. Additionally, quantifying waterborne parasites in environmental samples is necessary to assess public health risks, typically achieved through microscopy or qPCR. It is also important to include the assessment such as DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), for (oo)cyst viability, as it provides crucial information about the potential infectivity of parasites. Although molecular methods are powerful tools for detection and identification, their applicability in rural areas may be limited due to infrastructure and resource restrictions. These findings highlight the urgent need to strengthen environmental surveillance systems and sanitary controls in coastal areas.

7. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Coastal environments act as reservoirs and transmission routes for waterborne protozoan parasites such as Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Blastocystis sp., posing a public health risk through recreational water exposure and shellfish consumption. Detection variability across methodologies highlights the need for integrated diagnostic approaches.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) enhances sensitivity and specificity, while microbial indicators, combined with physicochemical parameters, offer cost-effective preliminary screening. Strengthening local laboratory capacities through training programs, mobile diagnostic units, and investment in basic infrastructure is crucial to ensure equitable access to parasitological surveillance in rural coastal communities. Seasonal monitoring in high-risk areas should include both water and shellfish matrices to support comprehensive risk assessment and One Health strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and G.V.; methodology, P.S.; software, P.S.; validation, J.L.A. and G.V.; formal analysis, P.S.; investigation, P.S.; resources, P.S.; data curation, P.S. and J.L.A.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S. and G.V.; writing—review and editing, P.S., J.L.A. and G.V.; visualization, P.S., supervision, G.V.; project administration, G.V.; funding acquisition, G.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ANID/FONDAP/1523A0001 and ANID/Scholarship Pro-gram/DOCTORADO BECAS CHILE 2021-21210338.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

P. Suarez thanks the ANID/Scholarship Program/DOCTORADO BECAS CHILE 2021-21210338 for her scholarship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mora, C.; McKenzie, T.; Gaw, I.; Dean, J.; von Hammerstein, H.; Knudson, T.; Setter, R.; Smith, C.; Webster, K.; Patz, J.; et al. Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, J.C.; Hess, J.J.; Provenzano, D. Climate change, marine pathogens and human health. JAMA 2025, 334, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourli, P.; Eslahi, A.V.; Tzoraki, O.; Karanis, P. Waterborne transmission of protozoan parasite: A review of worldwide out-breaks—An update 2017–2022. J. Water Health 2023, 23, 1421–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Saldía, R.R.; Pino-Maureira, N.L.; Muñoz, C.; Soto, L.; Durán, E.; Barra, M.J.; Gutiérrez, S.; Díaz, V.; Saavedra, A. Fecal pollution source tracking and thalassogenic diseases: The temporal spatial concordance between maximum concentration of human mitochondrial DNA in seawater and Hepatitis A outbreaks among a coastal population. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 686, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuval, H.I. Thalassogenic Diseases. UNEP Regional Reports and Studies 1986, N° 79. United Nations Environment Programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/thalassogenic-diseases (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Shuval, H.I. Estimating the global burden of thalassogenic diseases: Human infectious diseases caused by wastewater pollution of the marine environment. J. Water Health 2003, 1, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravenscroft, J.; Eftim, S.; Soller, J.; Jones, K.; Ichida, A.; Marion, J.; Lee, J. Appliyng epidemiology and quantitative microbial risk assessment to ambient water quality evaluation: Case study of fecal contaminated water in a US inland lake. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2025, 31, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graczyk, T.K.; Sunderland, D.; Awantang, D.N.; Mashinski, Y.; Lucy, F.E.; Graczyk, Z.; Chomicz, L.; Breysse, P.N. Relationships among bather density, levels of human waterborne pathogens, and fecal coliform counts in marine recreational beach water. Parasitol. Res. 2010, 106, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstratiou, A.; Ongerth, J.E.; Karanis, P. Waterborne transmission of protozoan parasite: Review of worldwide outbreaks—An update 2011–2016. Water Res. 2017, 114, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Bughattas, S.; Mahmoudi, M.R.; Khan, H.; Mamedova, S.; Namboodiri, A.; Masangkay, F.R.; Karanis, P. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis: An update of Asian perspective in humans, water and food, 2015–2025. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector-Borne Dis. 2025, 8, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einarsson, E.; Maayeh, S.; Svard, S.G. An up-date on Giardia and giardiasis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016, 34, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykur, M.; Camyar, A.; Turk, B.G.; Sin, A.Z.; Dagci, H. Evaluation of association with subtypes and alleles of Blastocystis with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Acta Trop. 2022, 231, 106455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First Addendum; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Supreme Decret 90 Laws, Chile N°1475. Diario Oficial, 7 March 2000. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=182637 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- De la Peña, L.B.; Pago, E.J.; Rivera, W. Characterization of Cryptosporidium isolated from Asian Green mussels sold in wet markets of Quezon city, Philippines. Philipp. Agric. Sci. 2017, 100, S45–S54. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez, P.; Yánez, M.J.; Fernández, I.; Madrid, V. Detection of Cryptosporidium parvum (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) oocyst in Aulacomya ater specimen, extracted from to the coast Biobío region, Chile. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2020, 37, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisuphanunt, M.; Wilairatana, P.; Kooltheat, N.; Damrongwatanapokin, T.; Karanis, P. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium oocyst in commercial oysters in southern Thailand. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2023, 32, e00205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, P.; Vallejos-Almirall, A.; Fernández, I.; González Chavarria, I.; Alonso, J.L.; Vidal, G. Identification of Cryptosporidium parvum and Blastocystis hominis subtype ST3 in Cholga mussel and treated sewage: Preliminary evidence of fecal contamination in harvesting area. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2024, 34, e00214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.F.; Carvalho, M.; de Freitas, M.; Begramo, C. Mussels (Perna perna) as bioindicator of environmental contamination by Cryptosporidium species with zoonotic potential. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasite Wildl. 2016, 5, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tei, F.F.; Kowalyk, S.; Reid, J.A.; Presta, M.A.; Yesuda, R.; Mayer, D.C.G. Assessment and molecular characterization of human intestinal parasites in bivalve from Orchard beach, NY, USA. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghozzi, K.; Marangi, M.; Papini, R.; Lahmar, I.; Challouf, R.; Houas, N.; Dhiab, R.B.; Normanno, G.; Badda, H.; Giangaspero, A. First report of Tunisian coastal water contamination by protozoan parasites using mollusk bivalve as biological indicators. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 117, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coupe, A.; Howe, L.; Burrows, E.; Sine, A.; Pita, A.; Velathanthin, N.; Vallée, E.; Hayman, D.; Shapiro, K.; Roe, W.D. First report of Toxoplasma gondii sporulated oocyst and Giardia duodenalis in commercial green-lipped mussels (Perna canaliculus) in New Zealand. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedde, T.; Marangi, M.; Papini, R.; Salza, S.; Normanno, G.; Virgilio, S.; Giangaspero, A. Toxoplasma gondii and other zoonotic protozoan in Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and blue mussel (Mytilus edulis): A food safety concern? J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, S25–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manore, A.J.W.; Harper, S.L.; Sargeant, J.M.; Weese, J.S.; Cunsolo, A.; Bunce, A.; Shirley, J.; Sudlovenick, E.; Shapiro, K. Cryptosporidium and Giardia in locally harvested clams in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Zoonoses Public Health 2020, 67, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligda, P.; Claerebout, E.; Casaert, S.; Robertson, L.; Sotiraki, S. Investigations from Northern Greece on mussels cultivated in areas proximal to wastewaters discharges as a potential source for human infections with Giardia and Cryptosporidium. Exp. Parasitol. 2020, 210, 107848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.M.; Pinto, A.L.; Cardoso, K.F.; Barreira, R.D.; Cutrim, D.; dos Santos, L.S.; Silva, V.C.; Pereira, H.; Chavez, N.P. Cryptosporidium sp. in cultivated oysters and the natural oyster stock of the state of Maranhao, Brazil. Cienc. Rural. 2023, 53, e20210014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merks, H.; Boone, R.; Janecko, N.; Viswanathan, M.; Dixon, B.R. Foodborne protozoan parasites in fresh mussels and oyster purchased at retail in Canada. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 399, 110248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staggs, S.E.; Keely, S.P.; Ware, M.W.; Schable, N.; See, M.J.; Gregorio, D.; Zou, X.; Su, C.; Dubey Villegas, E. The development and implementation of a method using blue mussels (Mytilus spp.) as biosentinels of Cryptosporidium spp. and Toxoplasma gondii contamination in marine aquatic environments. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 4655–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagoso, E.J.; Rivera, W. Cryptosporidium species from common edible bivalves in Manila Bay, Philippines. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, K.C.; de Souza, M.; Navarro, M.I.; Zanoli, M.I.; Cássia, A.; Razzolini, M.T.P. Assessment of health risk from recreational exposure to Giardia and Cryptosporidium in coastal bathing waters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 23129–23140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, A.; Symonds, E.M.; Gallard-Gogora, J.F.; Mull, B.; Lukasic, J.O.; Rivera, P.; Badilla, A.; Peraud, J.; Brown, M.L.; Mora, D.; et al. Among microbial indicators of fecal pollution, microbial source tracking markers and pathogens in Costa Rica coastal waters. Water Res. 2021, 188, 116507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour, S.; Nikaeen, M.; Rabbani, D.; Mohammadi, F.; Mohammadi, R.; Besharatipour, N.; Bina, B. Occurrence of enteric and non-enteric microorganisms in coastal waters impacted by anthropogenic activities: A multi-route QMRA for swimmers. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 188, 114716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiguet-Leal, D.A.; Greinert Goulart, J.A.; Bonatti, T.R.; Araujo, R.S.; Juski, J.A.; Shimada, M.K.; Pereira, G.H.; Roratto, P.A.; Scherer, G.S. A two-year monitoring of Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts and Giardia spp. cysts in freshwater and seawater: A complementary strategy for measuring sanitary patterns of recreational tropical coastal areas from Brazil. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 70, 1033956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, P.; Fernández, I.; Alonso, J.L.; Vidal, G. Evidence of waterborne parasite in mussels for human consumption harvested from a recreational and highly productive bay. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryckman, M.; Gantois, N.; García, R.; Desramaut, J.; Li, L.; Even, G.; Audebert, C.; Devos, D.; Chabé, M.; Certad, G.; et al. Molecular identification and subtype analysis of Blastocystis sp. isolates from wild mussels (Mytilus edulis) in Northern France. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Fernández, V.; Andolf, R.; Palomba, M.; Aco-Albuquerque, R.; Santoro, M.; Protano, C.; Mattiucci, S. First molecular detection of Blastocystis sp. in Mediterranean mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis from the western coast of Italy: Seafood safety and environmental contamination implications. Food Control 2026, 181, 111730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolorean, Z.; Gulabi, B.B.; Karanis, P. Molecular identification of Blastocystis sp. subtypes in water samples collected from black sea, Turkey. Acta Trop. 2018, 180, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Goncalves, S.; Machado, A.; Borlado, A.; Mesquita, J.R. Anthropogenic Blastocystis from drinking well and coastal water in Guinea-Bissau (West Africa). Microorganisms 2025, 13, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, A.M.; Gómez, G.; González-Rocha, G.; Piña, B.; Vidal, G. Performance of full-scale rural wastewater treatment plants in the reduction of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes from small-city effluents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Y.; Salgado, P.; Vidal, G. Disinfection behavior of a UV-treated wastewater system using constructed wetlands and the rate of reactivation of pathogenic microorganisms. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 80, 1870–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, U.M.; Feng, Y.; Fayer, R.; Xiao, L. Taxonomy and molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium and Giardia—A 50 year perspective (1971–2021). Int. J. Parasitol. 2021, 51, 1099–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, P.; Alonso, J.L.; Gómez, G.; Vidal, G. Performance of sewage treatment technologies for the removal of Cryptosporidium sp. and Giardia sp.: Toward water circularity. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 324, 116320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Sun, L.; Sun, Y.; Fu, X.; Ma, S.; Zhang, J.; Yan, B. Molecular identification and genotyping of Blastocystis in farmed cattle, goats and pigs from Zhejiang province, China. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2025, 40, e00280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathan, S.; Suthindhiran, K. Microbial contamination in the marine recreational sites and its impact on public health. Ocean Coast. Manage 2025, 267, 107757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerace, E.; Di Marco, V.; Biondo, C. Cryptosporidium infection: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and differential diagnosis. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 9, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkessa, S.; Ait-Salem, E.; Laatamna, A.; Houali, K.; Wolff, U.; Hakem, A.; Bouchene, Z.; Ghalmi, F.; Stensvold, C.R. Prevalence and clinical manifestation of Giardia intestinalis and other intestinal parasite in children and adults in Algeria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemo, F.E.; Singh, G.; Reddy, P.; Stenstrom, T.A. Methods for the detection of Cryptosporidium and Giardia: From microscopy to nucleic acid based tools in clinical and environmental regimes. Acta Trop. 2018, 184, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohweyer, J.; Dumetre, A.; Aubert, D.; Azas, N.; Villena, I. Tools and methods for detecting and characterizing Giardia, Cryptosporidium and Toxoplasma parasites in marine mollusks. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 1649–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligda, P.; Claerebout, E.; Robertson, L.J.; Sotiraki, S. Protocol standardization for the detection of Giardia cyst and Cryptosporidium oocyst in Mediterranean mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 298, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigot-Clivot, A.; La Carbona, S.; Cazeaun, C.; Durand, L.; Géba, E.; Le Foll, F.; Xuereb, B.; Chalghmi, H.; Dubey, J.P.; Bastien, F.; et al. Blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) a bioindicator of marine water contamination by protozoa: Laboratory and in situ approaches. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 132, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Rueda, L.; Packham, A.; Moore, J.; Wuertz, S.; Shapiro, K. Molecular detection and viability discrimination of zoonotic protozoan pathogens in oysters and seawater. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 407, 110391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Silva, J.; Ribeirinho-Soares, S.; Oliveira-Inocencio, I.; Pedrosa, M.; Silva, A.M.T.; Nunes, O.C.; Manaia, C.M. Performance of polycarbonate, cellulose nitrate and polyethersulfone filtering membrane for culture-independent microbiota analysis of clean waters. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Hawkins, S.J. Mucus from Marine Mollusks. Adv. Mar. Biol. 1998, 34, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, J.J.; Becklund, L.E.; Carey, L.E.; Carey, S.J.; Fabre, P. What is the "modified CTAB protocol"? Characterizing modifications to the CTAB DNA extraction protocol. Appl. Plant Sci. 2023, 11, e11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachimi, O.; Falender, R.; Davis, G.; Waffula, R.V.; Sutton, M.; Bancroft, J.; Cieslak, P.; Kelly, C.; Kaya, D.; Radniecki, T. Evaluation of molecular-based methods for the detection and quantification of Cryptosporidium spp. in wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensvold, C.R.; Kumar, G.; Tan, K.S.W.; Thompson, R.C.A.; Traub, R.J.; Viscogliosi, E.; Yoshikawa, H.; Clark, C.G. Terminology for Blastocystis subtypes—A consensus. Trends Parasitol. 2006, 23, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladele, D.; Swain, M.; Robinson, G.; Clare, A.; Chalmers, R. A review of recent Cryptosporidium hominis and Cryptosporidium parvum gp60 subtypes. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector-Borne Dis. 2025, 8, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Gupta, U.D. Next Generation Sequencing and its applications: Empowering in public health beyond reality. In Microbial Technology for Welfare of Society; Kumar, P., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019; Volume 17, pp. 313–341. [Google Scholar]

- DeMone, C.; McClure, J.T.; Greenwood, S.J.; Fung, R.; Hwang, M.H.; Feng, Z.; Shapiro, K. A metabarcording approach for detecting protozoan pathogens in wild oyster from Prince Edward Island, Canada. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 360, 109315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, A.; Gray, T.L.; Paparini, A.; Linge, K.L.; Joll, C.A.; Ryan, U.M. Identification of eukarytic microorganism with 18S rRNA next-generation sequencing in wastewater treatment plants, with a more target NGS approach required for Cryptosporidium detection more targeted NGS approach required for Cryptosporidium detection. Water Res. 2019, 158, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, A.; Gofton, A.W.; Greay, T.; Monis, P.; Oskam, C.; Ball, A.; Bath, A.; Watkinson, A.; Robertson, I.; Ryan, U. Profiling the diversity of Cryptosporidium species and genotype in wastewater treatment plants in Australia using next generation sequencing. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthethwa, N.; Amoah, I.D.; Gomez, A.; Davison, S.; Reddy, P.; Bux, F.; Kumari, S. Profiling pathogenic protozoan and their functional pathways in wastewater using 18rRNA and shotgun metagenomics. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payment, P.; Franco, E. Clostridium perfringens and somatic coliphages as indicators of the efficiency of drinking water treatment for viruses and protozoan cysts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 2418–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijnen, W.A.M.; Brouwer-Hanzens, A.J.; Charles, K.J.; Medema, G.J. Spores of sulphite-reducing clostridia: A surrogate parameter for assessing the effects of water treatment processes on protozoan oocysts. Water Sci. Tech. 1997, 35, 285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Agulló-Barceló, M.; Oliva, F.; Lucena, F. Alternative indicators for monitoring Cryptosporidium oocyst in reclaimed water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 4448–4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelma, G. Use of bacterial spores in monitoring water quality and treatment. J. Water Health 2018, 16, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wielinga, C.; Williams, A.; Monis, P.; Thompson, R.C.A. Proposed taxonomic revision of Giardia duodenalis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2023, 111, 105430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, P.; Muñoz, M.; Ramírez, J.D. An update on the distribution of Blastocystis subtype in the Americas. Heliyon 2023, 8, e2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, P.A.; Jaimes, J.E.; Ramírez, J.D. A summary of Blastocystis subtypes in north and south America. Parasite Vec. 2019, 12, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.