Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) is an opportunistic pathogen associated with healthcare-related infections and is of particular concern due to its high level of antibiotic resistance and its ability to form biofilms. The global emergence of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii highlights the urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies. This study investigated the antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of two scorpion venom-derived peptides, pantinin-1 and pantinin-2, against a reference strain and a clinical isolate of A. baumannii. We found that both peptides, in the non-cytotoxic concentration range, have strong bactericidal activity, showing a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 6.25 μM and 12.5 μM for pantinin 1 and 2, respectively. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis showed that the peptides cause extensive damage to the bacterial membrane. Furthermore, both peptides showed potent antibiofilm activity, inhibiting adhesion and maturation, arresting biofilm expansion, and reducing the expression of key biofilm-associated genes (bap, pgaA, and smpA). Altogether, these findings indicate that pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 act through a dual mechanism, combining bactericidal and antivirulence activities. Their strong efficacy at low micromolar concentrations, together with low cytotoxicity, underscores their potential as innovative therapeutic candidates against infections caused by carbapenem-resistant, biofilm-forming A. baumannii.

1. Introduction

The emergence of antibiotic resistance poses a major global health threat, undermining the ability to treat both common and complicated infections and compromising advancements in modern medicine [1,2,3]. Within this context, the ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.) have been prioritized by the World Health Organization and other public health agencies due to their capacity to rapidly acquire and disseminate multiple resistance mechanisms, thereby evading most currently available antibiotics [4,5].

Among Gram-negative bacteria, Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) stands out as a particularly challenging pathogen because of its diverse virulence and resistance patterns. These include a double membrane that restricts antibiotic penetration, highly efficient efflux pumps, the production of antibiotic-degrading enzymes, and a remarkable ability to acquire and spread resistance genes via mobile genetic elements [6,7]. In addition, A. baumannii demonstrates exceptional resilience to harsh environmental conditions, enabling survival on hospital surfaces and medical equipment. This persistence underlines its role as a major cause of healthcare-associated infections, including ventilator-associated pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and wound infections [3,8]. Resistance rates of A. baumannii to key antibiotic classes, including carbapenems, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides, now exceed 90% [3,9]. Alarmingly, resistance has also emerged against last-line agents such as colistin, leaving very limited therapeutic options and contributing to elevated morbidity and mortality among affected patients. This problem extends beyond traditional antibiotics: even newly developed macrocyclic and peptide antibiotics, once considered effective and relatively safe, have rapidly encountered the emergence of resistant strains [5,10,11]. The ability of A. baumannii to form biofilms is a key virulence factor that greatly contributes to its persistence and resistance in clinical settings, enabling long-term adhesion to surfaces and medical equipment. Biofilms also impair host immune defenses and reduce the efficacy of antimicrobial agents, leading to infections that are difficult to eradicate and may progress to chronic conditions. Consequently, treating infections caused by biofilm-forming A. baumannii in healthcare environments remains particularly challenging [12].

Therefore, searching for alternative therapeutic strategies has become a global priority, and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have emerged as promising candidates [13]. AMPs are naturally occurring or synthesized molecules, typically short chains of 5–40 amino acid residues. They are generally cationic and amphipathic, properties that enable selective interaction with microbial membranes. This interaction can disrupt membrane integrity through destabilization and pore formation, ultimately leading to cell death [14,15,16]. Beyond their direct membranolytic activity, some AMPs interfere with intracellular processes, such as the recently identified translation initiation factor 1 (IF1)-derived peptide from Clostridium difficile, which inhibits bacterial growth by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit [17]. Additionally, AMPs can also modulate host immune responses and act synergistically with conventional antibiotics, thereby reducing the likelihood of resistance development [18].

Numerous AMPs have been identified across diverse sources, including humans, insects, amphibians, and microorganisms [19]. Among AMPs of animal origin, the pantinin family, derived from the venom of the scorpion Pandinus imperator, has attracted considerable interest. Specifically, pantinin-1 (primary sequence: GILGKLWEGFKSIV-NH2) and pantinin-2 (primary sequence: IFGAIWKGISSLL-NH2) are non-disulfide-bridged peptides with 14- and 13-amino acids, respectively, and α-helical structure, with antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria, fungi, and viruses [20,21,22,23]. Recent studies have also shown that pantinins are effective against multi-resistant strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae), acting rapidly on the bacterial outer membrane, reducing the expression of virulence genes, and exhibiting a low propensity to induce resistance [23]. In addition, these peptides display good stability under physiological conditions and low cytotoxicity toward eukaryotic cells, making them promising candidates for the development of novel antimicrobial therapies [24].

Despite these interesting results, the activity of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 against particularly problematic Gram-negative bacteria such as A. baumannii remains underexplored. Considering the critical role of A. baumannii in nosocomial infections and its remarkable capacity to develop multiple resistance mechanisms, it is essential to assess whether these peptides serve as effective alternatives or adjuncts to conventional antibiotics against this pathogen [25]. In the present study, we investigated the antimicrobial activities of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 against A. baumanni. In detail, we evaluated their effect on biofilm formation and maturation, as well as their potential to interfere with key resistance mechanisms. Through these analyses, we aim to gain a deeper understanding of the therapeutic potential of pantinins as novel treatment options for infections caused by multidrug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens, thereby contributing new insights to the fight against antibiotic resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Peptide Synthesis and Characterization

Peptides were synthesized with an amidation at the C-terminal end using the solid-phase Fmoc (fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl) strategy on the SYRO I automated peptide synthesizer (Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden), following well-established protocols [23]. Briefly, after synthesis, peptides were purified via reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) on a WATERS 2545 preparative system equipped with a UV/Vis detector (Waters 2489, Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The identity and purity of the peptides were confirmed through liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis using a LTQ XL™ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA). Separation was performed on a Waters xBridge C18 column (5 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm) with a linear gradient of acetonitrile (CH3CN) and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water and TFA, ranging from 10% to 80% acetonitrile over 10 min at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The peptide exhibited a purity exceeding 95%. Peptide concentration was determined by UV-Vis spectroscopy at 280 nm using a standard 1-cm path length cuvette. Concentrations were calculated via the Beer-Lambert Law (A = Ɛ × l × C) using a molar extinction coefficient (Ɛ) of 5500 M−1 cm−1. After baseline correction with the appropriate buffer, samples were measured in duplicate and results expressed as the mean value.

2.2. Bacterial Strains

To assess the antimicrobial activity of pantinins, we used a standard strain of A. baumannii (BAA-747, acquired from the American Type Culture Collection, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and a clinical strain kindly provided by the Complex Operative Unit of Virology and Microbiology of the University Hospital “Luigi Vanvitelli” (Naples, Italy). The A. baumannii clinical strain was isolated on MacConkey agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were performed using the Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time-of-Flight system (MALDI-TOF, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) and the Phoenix BD system (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). After 16 h of incubation, resistance patterns were interpreted according to EUCAST breakpoints. Table S1 (Supplemental Material) reports the antibiogram profile of the same strain.

Before antibacterial testing, both strains were subcultured on Müller-Hinton agar (MHA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and grown in Müller-Hinton broth. For biofilm assays, A. baumannii strains were streaked on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar plates (Sigma-Aldrich) and grown in LB broth supplemented with 1% glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C under aerobic conditions [26].

2.3. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC80) and Minimal Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) Determination

The antibacterial activity of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 was evaluated against both standard and clinical strains of A. baumannii. The minimum concentration required to inhibit 80% bacterial growth (MIC80) and the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), i.e., the lowest peptide concentration that resulted in a 99.9% killing of bacterial cells, were determined using the broth microdilution method [27]. Peptide activity was tested over a concentration range of 50–1.56 μM.

Briefly, a pure colony grown in MHA was inoculated into MH broth and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm until the mid-logarithmic growth phase was reached. A bacterial suspension of 1 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL in fresh MH broth was then prepared and dispensed (50 μL/well) into a microtiter plate preloaded with serial two-fold dilutions of pantinin-1 or pantinin-2, resulting in a final inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU/well. Gentamicin (4 μg/mL) was used as a positive control against the A. baumannii ATCC strain, while colistin (5 μg/mL) was used as a positive control against the clinical isolate strain. Untreated bacterial cells served as a negative control. After 20 h of incubation at 37 °C, bacterial turbidity was measured spectrophotometrically at 600 nm. Growth inhibition was calculated using the following formula:

% Growth inhibition = [1 − (Abs600nm test sample)/Abs600nm CTR negative] × 100

To determine MBC values, 50 μL from wells showing no visible growth were spread onto MHA plates, as described previously [28]. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, and bacteria were counted and enumerated. The MBC was defined as the lowest peptide concentration that resulted in a 99.9% killing of bacterial cells.

Time-Kill Kinetic Assay

Time-kill kinetic assays were performed to monitor the activity of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 over time against the planktonic form of A. baumannii BAA-747, using the same experimental conditions as the MIC assay [29]. At selected time points (0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 18 h), 100 μL aliquots from each treatment group (½× MIC, 1× MIC, and 2× MIC) were serially diluted 10-fold in 1× PBS, plated onto MHA, and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Bacterial colonies were finally counted, and the CFU/mL was calculated. Peptide-free cultures served as negative controls, while gentamicin (4 μg/mL) was included as a positive control.

2.4. Synergism Assay

To evaluate the combined effect of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2, a synergism assay was performed [30,31]. An A. baumannii inoculum of 2 × 105 CFU/mL was prepared for the test. The IC50 of each peptide was selected, and 10 μL of the corresponding peptide solutions were added to the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate, either individually or in combination. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Bacterial growth inhibition was determined spectrophotometrically at 600 nm and calculated using the following formula:

% Growth inhibition = [1 − (Abs600nm test sample)/Abs600nm CTR negative] × 100

2.5. Antibiofilm Activity

2.5.1. Biofilm Adhesion and Maturation

The efficacy of synthetic peptides pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 in counteracting the biofilm adhesion (2 h) and formation (24 h) phases of the A. baumannii ATCC strain was evaluated [32]. An A. baumannii inoculum was prepared at a density of 2 × 108 CFU/mL in LB broth supplemented with 1% glucose and exposed to the peptides at concentrations ranging from 1.56 to 25 μM. Treatments were performed for 2 h and 24 h at 37 °C under static conditions. Untreated bacterial cultures served as negative controls. Following incubation, the biofilms were washed twice with 1× PBS to remove non-adherent cells and stained with 0.05% crystal violet (CV) for 40 min. Excess dye was discarded, and the wells were rinsed with 1× PBS. The bound CV was then solubilized with 100% ethanol for 10 min. In parallel, biofilm metabolic activity was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich) assay under the same experimental conditions. After 2 h and 24 h of peptide exposure, biofilms were washed and incubated with 0.5 mg/mL MTT solution for 3 h at 37 °C. The resulting formazan crystals were dissolved in 100% DMSO for 10 min. For both assays, absorbance was measured at 570 nm. Biofilm inhibition and metabolic activity were calculated according to the following formulas:

% Biofilm inhibition = 1 − (OD570 nm test sample/OD570 nm CTR negative) × 100

% Metabolic activity = 1 − (OD570 nm test sample/OD570 nm CTR negative) × 100

2.5.2. Biofilm Degradation

Biofilm eradication activity was quantified using the CV colorimetric assay [33]. An overnight culture of A. baumannii ATCC was adjusted to a density of 2 × 108 CFU/mL in LB broth supplemented with 1% glucose and added to each well of a 96-well microtiter plate. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h under static conditions to allow mature biofilm formation. After incubation, planktonic cells were removed, and the biofilms were washed twice with 1× PBS. The preformed biofilms were treated with the peptide concentrations described above for 24 h at 37 °C. The supernatant was discarded after treatment, and the biofilms were washed and stained with 0.05% CV. The bound dye was solubilized with DMSO, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm. Biofilm degradation was calculated according to the following formula:

% Biofilm degradation = 1 − (OD570 nm test sample/OD570 nm CTR negative) × 100

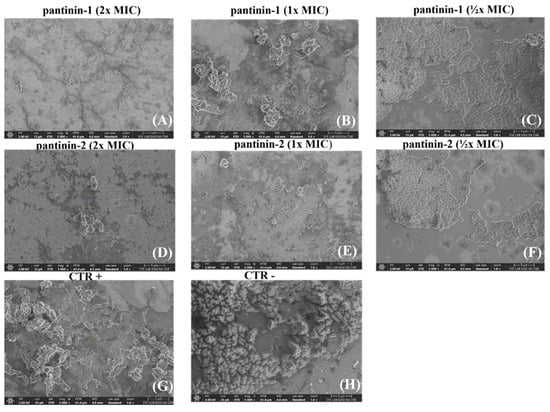

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

The morphological changes induced by pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 were studied using SEM [23,28]. Briefly, bacterial cultures were grown to the exponential phase and harvested by centrifugation at 1000× g for 10 min. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 10 mM PBS to an OD600 of 0.2. The bacterial suspensions were then exposed to peptides at different concentrations (MIC, 1× MIC, and ½× MIC) and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. After treatment, cells were collected by centrifugation, rinsed with PBS, and fixed overnight at 4 °C in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde. Finally, samples were washed with PBS and dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (50, 70, 90, and 100% v/v) for 15 min at each step. Images were acquired using a ThermoFisher Scientific Aquilos 2 double-beam FIB-SEM. The acquisition parameters were current 13 pA, voltage 2 kV, working distance 4.6 mm, field of view 20.7 μm, stage tilt 0°, and magnification 5.000×.

2.7. Molecular Analysis

PCR assays were performed to evaluate the expression of three virulence-associated genes, smpA, bap, and pgaA, using specific primers purchased from Eurofins (Vimodrone, Milan, Italy), as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequence of the primers used for the PCR assays.

Gene expression was evaluated following biofilm formation under different experimental conditions, as described above. Treatments were stopped after 2 h, 24 h, and 72 h during the attachment, inhibition, and degradation assays, respectively. Total RNA was extracted from the collected bacterial pellets using TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For each experimental condition, triplicate samples were pooled before extraction to ensure sufficient RNA yield. The protocol included centrifugation of the lysates, followed by phase separation with chloroform, RNA precipitation with isopropanol, and washing with ethanol. The purified RNA pellet was finally resuspended in nuclease-free water and quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) to assess concentration and purity [34]. Subsequently, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the RT All-in-One MasterMix (Applied Biological Materials, Richmond, BC, Canada). PCR reactions for each target gene were performed in a total volume of 25 µL, containing 1 µL of cDNA, 4 µL of FIREPol Master Mix (Solis Biodyne, Tartu, Estonia), 0.5 µL of each primer, and 13 µL of distilled water. Amplified DNA fragments were resolved by horizontal electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels at 120 V for 35 min. Samples were mixed with DNA Loading Dye (Microtech, Naples, Italy), and molecular sizes were determined using the 1 kb Opti-DNA Marker (Microtech). The biofilm of A. baumannii ATCC BAA-747 served as a positive control.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in three biological and three technical replicates. Data are expressed as the mean ± Standard Deviation (SD). Statistical significance was assessed using One-way ANOVA or Two-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1 for macOS (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity

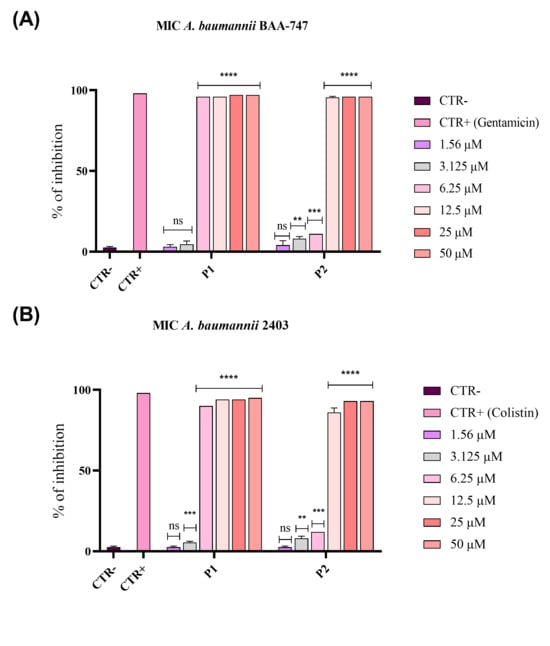

The antibacterial activity of pantinins was evaluated by the broth microdilution method and kinetic time-kill assays (see Section 2 for details) against bacterial cells from an ATCC strain BAA-747(A) and clinical strain 2403. Broth dilution tests showed that both synthetic peptides exhibited antibacterial activity against A. baumannii in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of A. baumannii growth by pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 through the broth microdilution method. Bacterial cells from an ATCC strain BAA-747 (A) and the clinical strain 2403 (B) were pantinin-1 (P1), pantinin-2 (P2), gentamicin, or colistin (CTR+). Untreated cells represented the negative control (CTR−). Data represent the mean ± SD. Dunnett’s multiple comparison test: (A) **** p-value < 0.001; *** p-value = 0.0005; ** p-value = 0.0077 and ns = not significant; (B) **** p-value < 0.0001; *** p-value = 0.0002; ** p-value < 0.0077 and ns = not significant.

Pantinin-1 exhibited the strongest antibacterial activity against ATCC and clinical strains, effectively inhibiting bacterial growth at an MIC80 of 6.25 μM (indicated as P1 in Figure 1A,B). On the other hand, pantinin-2 achieved complete inhibition at 12.5 μM against both strains (indicated as P2 in Figure 1A,B). Moreover, to distinguish between bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects of pantinins, the MBC was determined for both strains. Both peptides exhibited bactericidal activity at their respective MIC80 values.

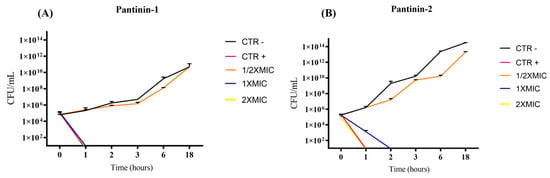

The antibacterial activity was further characterized through time–kill kinetic assays, which analyzed the growth of A. baumannii BAA-747 over time following the treatment with each peptide (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Time-kill kinetic assay of pantinins against A. baumannii ATCC. Temporal killing profiles of pantinin-1 (A) and pantinin-2 (B) are shown. CTR−: untreated bacteria; CTR+: bacteria treated with gentamicin (4 μg/mL).

3.2. Effect of Pantinins on Different Stages of Biofilm Formation

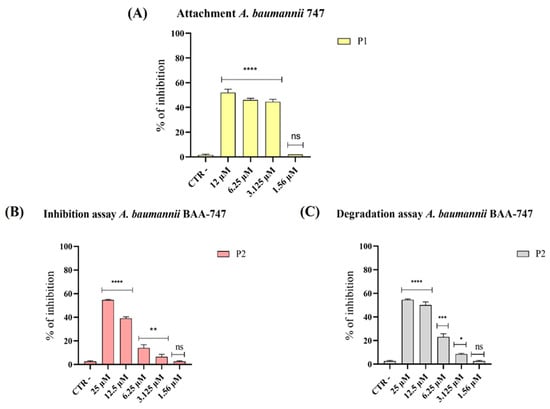

Biofilm formation provides bacteria with protection against the host immune system and increases their resistance to antibiotics by 10- to 1000-fold compared with their planktonic form [35]. In the present study, biofilms were exposed to peptide concentrations ranging from 2× MIC to 1.56 µM. Biomass biofilm was quantified using the CV staining method, while the viability of sessile cells was assessed using the MTT assay (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of anti-biofilm activity of pantinins against A. baumannii. (A) Impact of pantinin-1 (P1) on A. baumannii biofilm in the early adhesion stages; (B) effect of pantinin-2 (P2) during biofilm formation; and (C) activity against preformed biofilms. CTR−: untreated bacteria. Data represent the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Dunnett’s multiple comparison test: (A) **** p-value < 0.0001 and ns: not significant; (B) **** p-value < 0.0001, ** p-value = 0.0015 and ns = not significant; (C) **** p-value < 0.0001, *** p-value = 0.0001, * p-value = 0.457 and ns: not significant.

Our results showed a significant reduction in biofilm biomass following treatment with pantinin-1 during the initial adhesion phase (Figure 3A) and with pantinin-2 during the maturation phase (Figure 3B). Exposure to pantinin-1 impaired the adhesion capacity of A. baumannii by 50% and 45% at concentrations of 12.5 µM and 6.25 µM, respectively (Figure 3A). Conversely, pantinin-2 exhibited notable activity during the biofilm maturation phase, reducing biofilm biomass by 50% and 40% at concentrations of 25 µM and 12.5 µM, respectively (Figure 2B). Furthermore, analysis of mature biofilms revealed that pantinin-2 was effective in disrupting preformed biofilms (Figure 3C). Specifically, treatment with pantinin-2 reduced biofilm biomass by 55% at 25 μM and by 50% at 12.5 μM.

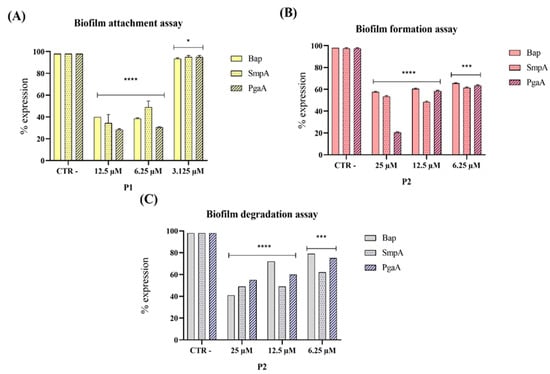

3.3. Evaluation of Virulence Gene Expression

Several key factors contribute to the virulence of A. baumannii, including biofilm production, the synthesis of poly-β-(1-6)-N-acetylglucosamine polysaccharide (PNAG), and cell adhesion. To evaluate the ability of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 to suppress these virulence determinants, we analyzed the expression of three specific genes (Figure 4): bap, involved in biofilm formation [36]; pgaA, which encodes proteins responsible for PNAG synthesis [37], and smpA, an outer membrane assembly protein that contributes to the structural integrity of the bacterium [38].

Figure 4.

Gene expression levels of the three genes bap, smpA, and pgaA by PCR analysis after treatment of pantinin-1 (P1) and pantinin-2 (P2). Different assays were conducted: (A) biofilm attachment assay; (B) biofilm formation assay; and (C) biofilm degradation assay. Data represent the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Dunnett’s multiple comparison test: (A) **** p-value < 0.0001 and * p-value = 0.0299; (B) **** p-value < 0.0001 and *** p-value = 0.0001; (C) **** p-value < 0.0001 and *** p-value = 0.0001.

Our results demonstrated that both pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 significantly downregulated the expression of the virulence genes analyzed. In particular, pantinin-1 reduced gene expression during the initial attachment phase (Figure 4A), whereas pantinin-2 decreased expression in both the biofilm formation inhibition assay (Figure 4B) and mature biofilm degradation assay (Figure 4C). These findings highlight the ability of pantinins to interfere with biofilm development by targeting key virulence factors essential for biofilm formation and stability.

3.4. The Effects of Pantinin-1 and Pantinin-2 on the Integrity of A. baumannii Surface

We investigated the effects of pantinins on the surface integrity of the A. baumannii surface using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

SEM analysis of A. baumannii cells treated with different concentrations of pantinins. Cells were exposed to 2× MIC (A,D), 1× MIC (B,E), and ½× MIC (C,F) of each peptide. CTR− corresponds to untreated bacteria (H), while CTR+ corresponds to bacteria treated with gentamicin (4 μg/mL) (G). Images were acquired at a magnification of 5000×.

Bacterial cells were treated with different concentrations of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 (½× MIC, 1× MIC, and 2× MIC), and surface morphological alterations were examined. Compared with the negative control (untreated bacterial cells), peptide-treated cells exhibited markedly rougher surfaces, along with visible cell shrinkage and the presence of extracellular debris, likely resulting from leakage of intracellular material due to membrane damage. Samples treated with 2× MICs (Figure 5A,D) displayed more pronounced morphological alterations than those treated with MICs (Figure 5B,E), indicating that higher peptide concentrations cause more extensive damage to A. baumannii cells. In contrast, the negative control (Figure 5H) showed smooth, intact cell surfaces with a typical bacillary morphology.

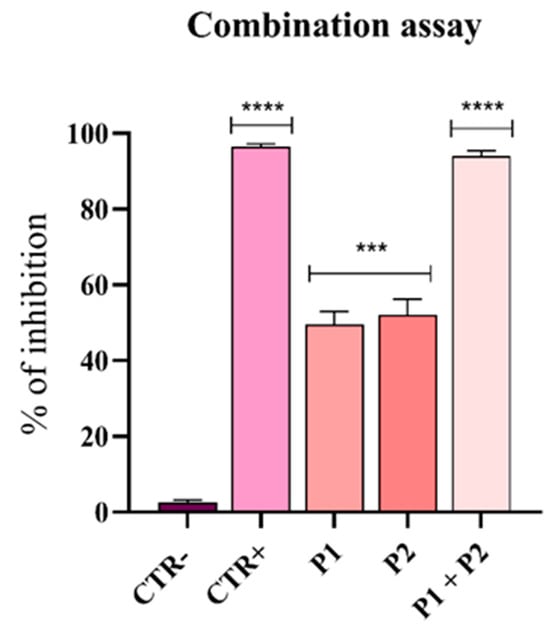

3.5. Synergistic Effect of Pantinins Against A. Baumannii

In severe bacterial infections, combination therapy is often more effective than monotherapy in eradicating pathogens. The combined antibacterial activity of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 was evaluated to assess potential synergy (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Synergistic effect of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2. Data are presented as mean ± SD. CTR−: untreated cells; CTR+: cells treated with gentamicin (4 μg/mL). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance values refer to treated cells. **** p-value < 0.0001; *** p-value = 0.0003.

As previously determined, the MIC80 of pantinin-1 against A. baumannii was 6.25 µM (Figure 1A), while the concentration at which we observed a 50% inhibition (IC50) was 3.2 µM. For pantinin-2, the MIC80 was 12.5 µM (Figure 1B), while its IC50 was 9.7 µM. The combination assay revealed that when both peptides were applied at their IC50 simultaneously, the antibacterial effect was strongly improved with respect to that observed with each peptide applied individually at its MIC (Figure 1).

4. Discussion

A. baumannii remains a major challenge in healthcare settings due to its ability to persist in hospital environments, form resilient biofilms, and acquire multiple resistance determinants. The increasing prevalence of MDR and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains, including those resistant to last-line antibiotics such as colistin, underscores the urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies [27,28,29,30,31]. In this context, AMPs have emerged as promising alternative or adjunct therapies. Cationic α-helical antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), such as those derived from scorpion venom, often exert their antibacterial effects by disrupting bacterial membranes, which reduces the likelihood of bacteria developing classical resistance mechanisms [14].

Our findings demonstrate that pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 can effectively reduce bacterial growth and disrupt biofilms, suggesting that these peptides may offer a promising approach to counteract infections caused by resistant A. baumannii strains.

We observed a strong antibacterial effect of pantinins against the A. baumannii strain and the clinical isolate CRAB. Specifically, pantinin-1 showed the greatest potency, with a MIC of 6.25 μM; while pantinin-2 exhibited a MIC of 12.5 μM, against both microbes (Figure 1). Notably, these values also corresponded to the MBCs, indicating that both peptides exerted a bactericidal rather than bacteriostatic effect. The antibacterial action of both peptides was rapid, as demonstrated by the time-kill kinetic assay (Figure 2). Pantinin-1 completely eradicated bacterial cells within 1 h (Figure 2B), showing an effect comparable to that of gentamicin used as a positive control. In contrast, pantinin-2 exhibited a slower bactericidal activity, with inhibition of bacterial growth observed after 2 h of treatment. These findings are consistent with our previously reported data on the antibacterial potential of pantinins against K. pneumoniae [18]. In that study, pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 exhibited rapid bactericidal activity within 1 h, with MIC80 values ranging from 6 to 25 µM for standard strains and from 25 to 50 µM for carbapenemase-producing clinical isolates. Importantly, while pantinin-1 exhibited greater potency against bacteria, pantinin-2 exerted a stronger efficacy against viruses [21,22], evidencing a different pattern of action. Such differences in efficacy may arise from variations in amino acid sequence or peptide conformation, potentially influencing their binding affinity to the pathogen membrane.

The antimicrobial activity of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 is primarily mediated through a membranolytic mechanism, which involves direct interactions with bacterial outer membrane lipopolysaccharides (LPS). Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy revealed that both pantinins adopt an α-helical conformation upon contact with LPS, supporting their membrane-targeting activity [18]. However, pantinin-2 exhibited greater hydrophobicity and a more pronounced amphipathic character, with a higher intrinsic propensity to adopt a helical conformation, as demonstrated through nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [22], which may underlie its enhanced antiviral activity. In contrast, pantinin-1 appears to be more effective against bacteria, possibly reflecting differences in how these peptides interact with distinct membrane architectures. Indeed, viral and bacterial membranes differ markedly in lipid composition and curvature, which may preferentially favor the membrane insertion and activity of pantinin-2 or pantinin-1, respectively.

SEM analysis suggested a membranolytic effect, as bacterial cell membranes appeared with surface roughness and morphological changes (Figure 5). At MIC80 values, only a small fraction of intact cells remained, whereas most bacteria displayed pronounced morphological alterations, including membrane roughness, deformation, and loss of structural integrity. At 2× MIC, SEM images revealed extensive cellular disruption and debris, consistent with severe membrane destabilization, cytoplasmic leakage, and eventual cell lysis. The cationic nature of pantinins facilitates strong electrostatic interactions with negatively charged phospholipids in bacterial membranes, promoting peptide insertion and rapid membrane disruption, which explains their rapid bactericidal activity [33]. In contrast, eukaryotic cell membranes, enriched in neutral or zwitterionic lipids and cholesterol, are less susceptible to peptide incorporation, explaining the higher concentrations required to affect host cells [35]. These findings align with recent reports; for example, Kumar et al. reviewed natural AMPs and synthetic analogs targeting A. baumannii membranes and cell walls, highlighting membrane disruption as an effective mechanism that is less prone to resistance development [39]. Overall, these results underscore that electrostatic targeting of bacterial membranes is central to the antimicrobial activity of cationic peptides and demonstrate their potent ability to compromise the cell membrane integrity of MDR pathogens such as A. baumannii.

Biofilm formation is a major determinant of antimicrobial resistance, as bacteria within biofilms can exhibit resistance levels hundreds to thousands of times higher than their planktonic counterparts [36]. In this study, pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 effectively interfered with multiple stages of biofilm development (Figure 3). Pantinin-1 inhibited the initial adhesion phase by 45% at 6.25 µM (Figure 3A), while pantinin-2 reduced biofilm formation by 55% at 25 µM and decreased mature biofilm biomass by 50% at 12.5 µM (Figure 3B,C). Both peptides also downregulated the expression of key virulence-associated genes (Figure 4), including bap, pgaA, and smpA, indicating that their activity extends beyond direct bactericidal effects to the suppression of biofilm formation, extracellular polysaccharide production, and membrane integrity. This suggests a multifaceted mechanism combining bactericidal and anti-virulence effects, which may help reduce bacterial pathogenicity and limit the development of resistance. This secondary mechanism, involving biofilm targeting and downregulation of virulence genes, is shared by other AMPs, such as human β-defensin 3 [40,41]. This peptide inhibits biofilm formation by reducing the expression of biofilm-associated genes icaA and icaD, while increasing the expression of icaR. Similarly, α-mangostin downregulated genes related to persister cell and biofilm formation, including norA, norB, dnaK, groE, and mepR [42].

The antibiofilm properties of scorpion venom–derived peptides remain largely underexplored; for instance, Hp1404, isolated from Heterometrus petersii venom, showed potent antibiofilm activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, significantly reducing biofilm formation and effectively eradicating mature biofilms at low micromolar concentrations [37]. These findings collectively highlight the considerable potential of scorpion peptides as innovative therapeutics to combat biofilm-associated infections caused by Gram-negative pathogens, and specifically by A. baumannii, paving the way for future preclinical and clinical investigations of these compounds. We have previously demonstrated that pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 exhibit high stability in human serum and low cytotoxicity toward mammalian cells [21,22,23]. Indeed, the stability of pantinins was previously assessed by incubation in serum for up to 16 h [23]. Pantinin-1 remained largely stable throughout this period, whereas pantinin-2 started to degrade after 4 h. Additionally, the cytotoxicity of both pantinins was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay in human keratinocytes (HaCaT) [23] and glioma (U-87 MG) cells [21], with significant toxicity observed only for pantinin-2 at 100 μM. In the present study, we further show that the two peptides can be combined, resulting in an enhanced antibacterial effect (Figure 6). Combining the peptides is particularly relevant because it may allow for synergistic interactions that reduce the effective concentrations needed for bacterial eradication, limit the likelihood of resistance development, and broaden the spectrum of activity against MDR strains. This strategy could thus improve therapeutic efficacy while minimizing potential toxicity, highlighting the potential of pantinin combinations as a novel approach to treat infections caused by highly resistant pathogens such as A. baumannii.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the potent antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of pantinin-1 and pantinin-2, two α-helical peptides derived from Pandinus imperator venom, against CRAB pathogens. Both peptides exhibited strong bactericidal activity, causing membrane disruption, and effectively interfered with biofilm development, including inhibition of initial attachment, biofilm maturation, and reduction in established biomass. Additionally, they suppressed the expression of key virulence genes associated with biofilm formation, while maintaining low cytotoxicity toward human keratinocytes.

Taken together, pantinin-1 and pantinin-2 are promising candidates for the development of novel anti-infective strategies against MDR A. baumannii. Further studies are needed to evaluate their activity against a broader panel of clinical isolates, in vivo efficacy, optimal formulation and delivery, and long-term stability. These findings provide a strong foundation for preclinical development and support ongoing efforts to identify innovative therapeutics targeting WHO-priority pathogens.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms14010068/s1, Table S1. Antibiogram A. baumannii 2403 isolated from peripheral vein blood culture. The strain producing class D carbapenemase (oxa-48) resulted positive after 6 h. Figure S1. Evaluation of anti-biofilm activity of pantinins against A. baumannii. (A) Impact of pantinin-1 (P1) in inhibiting A. baumannii biofilm and (B) degradation. (C) Effect of pantinin-2 (P2) during attachment phase. CTR−: untreated bacteria. Data represent the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Dunnett’s multiple comparison test: ns = not significant. Figure S2. SEM analysis of A. baumannii cells treated with different concentrations of pantinins. Cells were exposed to 2× MIC (A,D), 1× MIC (B,E), and ½× MIC (C,F) of each peptide. CTR− corresponds to untreated bacteria (H), while CTR+ corresponds to bacteria treated with gentamicin (4 μg/mL) (G). Images were acquired at a magnification of 10,000×.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.F. and M.G.; methodology, C.C., A.M. and F.D.; software, C.C.; validation, C.Z., N.D. and A.D.F.; investigation, C.C., R.G., A.C. and G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C. and C.Z.; writing—review and editing, N.D., E.E. and M.G.; supervision, A.D.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

N.D. acknowledges the financial support under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 2.1, funded by the NHS and the European Union NextGenerationEU Project PRR.AP015.060—Title: Molecular mimicry to improve liver cancer immunotherapy; CUP B63C22002050006—Grant Assignment PNRR-POC-2022-12375769; and SEE LIFE—StrEngthEning the ItaLIan InFrastructure of Euro-bioimaging, area ESFRI “Health and Food”—IR0000023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A. baumannii | Acinetobacter baumannii |

| AMPs | Antimicrobial Peptides |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MBC | Minimal Bactericidal Concentration |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| CV | Crystal Violet |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| HaCaT | Human Keratinocyte Cell Line |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulphoxide |

| CTR+ | Positive Control |

| CTR− | Negative Control |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| FBS | Bovine Fetal Serum |

| MH | Müller–Hinton |

| LB | Luria–Bertani |

| MALDI-TOF | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization–Time of Flight |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Unit |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| O/N | Overnight |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| RT | Reverse Transcription |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CRAB | Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii |

| MDR | Multidrug-Resistant |

| XDR | Extensively Drug-Resistant |

| PDR | Pan-Drug-Resistant |

| VAP | Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia |

| PNAG | Poly-β-(1-6)-N-acetylglucosamine |

| ST | Sequence Type |

References

- Pipito, L.; Rubino, R.; D’Agati, G.; Bono, E.; Mazzola, C.V.; Urso, S.; Zinna, G.; Distefano, S.A.; Firenze, A.; Bonura, C.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens: A Retrospective Epidemiological Study at the University Hospital of Palermo, Italy. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daruka, L.; Czikkely, M.S.; Szili, P.; Farkas, Z.; Balogh, D.; Grezal, G.; Maharramov, E.; Vu, T.H.; Sipos, L.; Juhasz, S.; et al. ESKAPE pathogens rapidly develop resistance against antibiotics in development in vitro. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukhalil, A.D.; Barakat, S.A.; Mansour, A.; Al-Shami, N.; Naseef, H. ESKAPE Pathogens: Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns, Risk Factors, and Outcomes a Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study of Hospitalized Patients in Palestine. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 3813–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.W.K.; Millar, B.C.; Moore, J.E. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 80, 11387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Arias, C.A. ESKAPE pathogens: Antimicrobial resistance, epidemiology, clinical impact and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, H. Virulence Factors and Pathogenicity Mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii in Respiratory Infectious Diseases. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampatakis, T.; Tsergouli, K.; Behzadi, P. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: Virulence Factors, Molecular Epidemiology and Latest Updates in Treatment Options. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalauskiene, G.V.; Malciene, L.; Stankevicius, E.; Radzeviciene, A. Unseen Enemy: Mechanisms of Multidrug Antimicrobial Resistance in Gram-Negative ESKAPE Pathogens. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Jiang, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhong, L.; Zhou, M.; Xie, S.; et al. Emergence and global spread of a dominant multidrug-resistant clade within Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyenuga, N.; Cobo-Díaz, J.F.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Alexa, E.-A. Overview of Antimicrobial Resistant ESKAPEE Pathogens in Food Sources and Their Implications from a One Health Perspective. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, J.; Reyneke, B.; Waso-Reyneke, M.; Havenga, B.; Barnard, T.; Khan, S.; Khan, W. Prevalence of ESKAPE pathogens in the environment: Antibiotic resistance status, community-acquired infection and risk to human health. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 244, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, K.; Ahmadi, M.H.; Rajabnia, M.; Halaji, M. Effects of Curcumin on Biofilm Production and Associated Gene in Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolated from Hospitalized Patients. Int. J. Mol. Cell Med. 2025, 14, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yi, X.; Du, R.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Q. Scorpion venom peptides enhance immunity and survival in Litopenaeus vannamei through antibacterial action against Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1551816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. APD3: The antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D1087–D1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, R.E.; Sahl, H.G. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlapuu, M.; Hakansson, J.; Ringstad, L.; Bjorn, C. Antimicrobial Peptides: An Emerging Category of Therapeutic Agents. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanis, E.; Aguilar, F.; Banaei, N.; Dean, F.B.; Villarreal, A.; Alanis, M.; Lozano, K.; Bullard, J.M.; Zhang, Y. A rationally designed antimicrobial peptide from structural and functional insights of Clostridioides difficile translation initiation factor 1. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0277323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, C.; Tammaro, L.; Duilio, A.; Di Somma, A. Investigation of the Mechanism of Action of AMPs from Amphibians to Identify Bacterial Protein Targets for Therapeutic Applications. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.H.; Kim, K.H.; Ki, M.R.; Pack, S.P. Antimicrobial Peptides and Their Biomedical Applications: A Review. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.C.; Zhou, L.; Shi, W.; Luo, X.; Zhang, L.; Nie, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; Cao, B.; Cao, H. Three new antimicrobial peptides from the scorpion Pandinus imperator. Peptides 2013, 45, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giugliano, R.; Zannella, C.; Della Marca, R.; Chianese, A.; Di Clemente, L.; Monti, A.; Doti, N.; Cacioppo, F.; Iovane, V.; Montagnaro, S.; et al. Expanding the Antiviral Spectrum of Scorpion-Derived Peptides Against Toscana Virus and Schmallenberg Virus. Pathogens 2025, 14, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.; Zannella, C.; Chianese, A.; Acconcia, C.; Monti, A.; Della Marca, R.; Pagnini, U.; Montagnaro, S.; Doti, N.; Isernia, C.; et al. Pantinin-Derived Peptides against Veterinary Herpesviruses: Activity and Structural Characterization. ChemMedChem 2025, 20, e202500333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.; Della Marca, R.; Chianese, A.; Monti, A.; Donadio, F.; Esposito, E.; Doti, N.; Zannella, C.; Galdiero, M.; De Filippis, A. The inhibitory potential of three scorpion venom peptides against multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pnemoniae. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1569719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrayess, R.A.; Mohallal, M.E.; Mobarak, Y.M.; Ebaid, H.M.; Haywood-Small, S.; Miller, K.; Strong, P.N.; Abdel-Rahman, M.A. Scorpion Venom Antimicrobial Peptides Induce Caspase-1 Dependant Pyroptotic Cell Death. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 788874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Cheng, J.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, M. Acinetobacter baumannii: An evolving and cunning opponent. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1332108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.; Dell’Annunziata, F.; Folliero, V.; Foglia, F.; Marca, R.D.; Zannella, C.; De Filippis, A.; Franci, G.; Galdiero, M. Cupferron impairs the growth and virulence of Escherichia coli clinical isolates. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chianese, A.; Ambrosino, A.; Giugliano, R.; Palma, F.; Parimal, P.; Acunzo, M.; Monti, A.; Doti, N.; Zannella, C.; Galdiero, M.; et al. Frog Skin Peptides Hylin-a1, AR-23, and RV-23: Promising Tools Against Carbapenem-Resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chianese, A.; Zannella, C.; Foglia, F.; Nastri, B.M.; Monti, A.; Doti, N.; Franci, G.; De Filippis, A.; Galdiero, M. Hylin-a1: A Host Defense Peptide with Antibacterial Potential against Staphylococcus aureus Multi-Resistant Strains. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.; Acunzo, M.; Della Marca, R.; Dell’Annunziata, F.; Folliero, V.; Chianese, A.; Zannella, C.; Franci, G.; De Filippis, A.; Galdiero, M. Evaluation of antifungal spectrum of Cupferron against Candida albicans. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 194, 106835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsari, C.; Luciani, R.; Pozzi, C.; Poehner, I.; Henrich, S.; Trande, M.; Cordeiro-da-Silva, A.; Santarem, N.; Baptista, C.; Tait, A.; et al. Profiling of Flavonol Derivatives for the Development of Antitrypanosomatidic Drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 7598–7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, F.; Heidrich, G.; Nordholt, N.; Schreiber, F. Prevalent Synergy and Antagonism Among Antibiotics and Biocides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 615618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, C.; Giugliano, R.; Della Sala, G.; Palma Esposito, F.; Tedesco, P.; Folliero, V.; Galdiero, M.; Franci, G.; de Pascale, D. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Properties and Potential Applications of Pseudomonas gessardii M15 Rhamnolipids towards Multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.; Della Sala, G.; Buonocore, C.; Zannella, C.; Tedesco, P.; Palma Esposito, F.; Ragozzino, C.; Chianese, A.; Morone, M.V.; Mazzella, V.; et al. New Imidazolium Alkaloids with Broad Spectrum of Action from the Marine Bacterium Shewanella aquimarina. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarachi-Olivera, R.; Teresa Mata, M.; Ardiles-Candia, A.; Escobar-Mendez, V.; Gatica-Cortes, C.; Ahumada, M.; Orrego, J.; Vidal-Veuthey, B.; Cardenas, J.P.; Gonzalez, L.; et al. Modification of the Trizol Method for the Extraction of RNA from Prorocentrum triestinum ACIZ_LEM2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surekha, S.; Lamiyan, A.K.; Gupta, V. Antibiotic Resistant Biofilms and the Quest for Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Indian. J. Microbiol. 2024, 64, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakavan, M.; Gholami, M.; Ahanjan, M.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.A.; Salehian, M.; Roozbahani, F.; Goli, H.R. Expression of bap gene in multidrug-resistant and biofilm-producing Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.J.; Tu, I.F.; Tseng, T.S.; Tsai, Y.H.; Wu, S.H. The deficiency of poly-beta-1,6-N-acetyl-glucosamine deacetylase trigger A. baumannii to convert to biofilm-independent colistin-tolerant cells. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, H.; Doosti, A.; Kargar, M.; Bijanzadeh, M.; Jafarinya, M.J.J.J.o.M. Antimicrobial resistant determination and prokaryotic expression of smpA gene of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from admitted patients. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2017, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G. Natural peptides and their synthetic congeners acting against Acinetobacter baumannii through the membrane and cell wall: Latest progress. RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 561–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, N.; Mishra, B.; Felix, L.; Mylonakis, E. Antimicrobial Peptides and Small Molecules Targeting the Cell Membrane of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2023, 87, e0003722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Tan, H.; Cheng, T.; Shen, H.; Shao, J.; Guo, Y.; Shi, S.; Zhang, X. Human beta-defensin 3 inhibits antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus biofilm formation. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 183, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felix, L.; Mishra, B.; Khader, R.; Ganesan, N.; Mylonakis, E. In Vitro and In Vivo Bactericidal and Antibiofilm Efficacy of Alpha Mangostin Against Staphylococcus aureus Persister Cells. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 898794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.