Abstract

Bacillus velezensis strain G2T39 is an endophytic bacterium previously isolated from Crotalaria retusa L., with evidenced biocontrol activity against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Cubense and Fusarium graminearum. In this study, it was shown that this strain also exhibited biocontrol activity against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Vasinfectum, two important crop pathogens in tropical zones. Comprehensive phylogenetic and genomic analyses were performed to further characterize this strain. The genome of B. velezensis G2T39 consists of a single circular chromosome of 4,040,830 base pairs, with an average guanine–cytosine (GC) content of 46.35%. Both whole-genome-based phylogeny and average nucleotide identity (ANI) confirmed its identity as B. velezensis, being closely related to biocontrol and plant growth promotion Gram-positive model strains such as B. velezensis FZB42. Whole-genome annotation revealed 216 carbohydrate-active enzymes and 14 gene clusters responsible for secondary metabolite production, including surfactin, macrolactin, bacillaene, fengycin, bacillibactin, bacilysin, and difficidin. Genes involved in plant defense mechanisms were also identified. Additionally, G2T39 genome harbors multiple plant growth-promoting traits, such as genes associated with nitrogen metabolism (nifU, nifS, nifB, fixB, glnK) and a putative phosphate metabolism system (phyC, pst glpQA, ugpB, ugpC). Additional genes linked to biofilm formation, zinc solubilization, stress tolerance, siderophore production and regulation, nitrate reduction, riboflavin and nicotinamide synthesis, lactate metabolism, and homeostasis of potassium and magnesium were also identified. These findings highlight the genetic basis underlying the biocontrol capacity and plant growth-promoting properties of B. velezensis G2T39 and support its potential application as a sustainable bioinoculant in agriculture.

1. Introduction

Global agricultural productivity plays a pivotal role in ensuring food security for an ever-growing population. However, plant diseases caused by pathogenic microorganisms continue to significantly threaten crop yields worldwide, undermining agricultural sustainability and food systems [1]. To counter these losses, the extensive use of chemical pesticides has become a common practice in modern farming [2]. While effective, the excessive and long-term application of agrochemicals has raised serious environmental concerns, including soil degradation, ecosystem contamination, and the emergence of resistant pathogen strains. Considering these challenges, there is a growing global demand for sustainable and environmentally friendly plant disease management strategies. Many countries are actively promoting alternative biosolutions, such as green pesticides and microbial biocontrol agents [3,4]. Among these, plant growth-promoting microorganisms (PGPMs), notably bacteria belonging to the genera Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Streptomyces, have gained increasing attention due to their multifaceted benefits. These microorganisms not only enhance plant growth and stress tolerance but also contribute to the suppression of phytopathogens [5,6,7]. Within this group, the genus Bacillus stands out owing to its genetic diversity, ease of cultivation, and spore-forming ability, which confers long-term stability and commercial viability. Several Bacillus species have demonstrated significant potential as biofertilizers and biopesticides, supporting their application in sustainable agriculture [8]. In particular, Bacillus velezensis, a reclassified species related to B. amyloliquefaciens [9], has drawn attention as a key PGPM. Strains of B. velezensis are known to produce a diverse array of antimicrobial metabolites, including lipopeptides (surfactin, bacillomycin D, fengycin, bacillibactin) and polyketides (macrolactin, bacillaene, difficidin), many of which contribute directly to the inhibition of plant pathogens [10]. For instance, B. velezensis FZB42 allocates approximately 8.5% of its genome to the biosynthesis of antibiotics and siderophores via nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) and polyketide synthase (PKS) pathways [11]. Specific compounds such as fengycin and bacillomycin D have shown synergistic antifungal activity against Fusarium oxysporum [12], while iturin and fengycin produced by B. amyloliquefaciens strains CECT 8237 and CECT 8238 display broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects [13]. Furthermore, genomic studies have revealed that B. velezensis strains isolated from a variety of hosts exhibit both plant growth-promoting and disease-suppressing traits [14,15,16,17,18]. In this trend, endophytic Bacillus species can be considered as a multifaceted toolbox for agriculture, environment, and medicine. Indeed, endophytic B. velenzensis strains with similar bioactivities have been isolated from medicinal and woody plants, including Cinnamomum camphora [19,20]. The recent isolation of various endophytic bacteria, including strain G2T39 from the medicinal plant C. retusa, followed by small-scale phenotypic analyses, demonstrated notable biocontrol potential against Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Cubense isolated from temperate regions [21]. Despite these advances, genomic and phylogenetic data remain limited for many newly identified B. velezensis strains. Given the observed antagonistic activity of strain G2T39 against Fusarium, we hypothesized that it may possess genomic determinants for antimicrobial production and plant growth promotion. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to (1) perform strain G2T39 whole-genome sequencing and analyses; and (2) predict gene functions that may support its functional characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Evaluation of B. velezensis Strain G2T39 Antagonistic Activity Against Phypathogenic Agents from Côte d’Ivoire

The antagonistic activity of Bacillus velezensis strain G2T39 was assessed in a previous work [21]. Strain G2T39 was obtained from the Laboratoire de Microbiologie, Biotechnologie et Bioinformatique (Institut National Polytechnique Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Côte d’Ivoire) In this study, G2T39 was evaluated against two important phytopathogenic fungi, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (FOV), causing diseases on mango and cotton, respectively, in Côte d’Ivoire, using an in vitro dual culture assay as described by Munakata et al., [22]. C. gloeosporioides and F. oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (FOV) were obtained from the Laboratoire Central de Biotechnologie (LCB), Centre National de Recherche Agronomique (CNRA), Côte d’Ivoire, and the assay was conducted as described by Ahoty et al. (2025) [21]. Briefly, 5 mm mycelial plugs were excised from the edge of actively growing fungal cultures and placed at the center of 9 cm diameter Petri dishes containing 12 mL of Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA). G2T39 bacterial cultures were grown in 2 mL of Nutrient Broth (NB) at 28 °C for either 24 or 72 h. A 50 µL aliquot of the bacterial suspension was then spotted 3 cm from the fungal plug on the same plate. Plates were incubated at 28 °C for five days or nine days according to the fungal pathogen. Each assay was performed in triplicate. Control plates were inoculated with the fungal pathogen only, without bacterial interference. Fungal growth inhibition was quantified by calculating the inhibition rate (%) [21,23].

2.2. Nitrogen Fixation Test

Strain G2T39 nitrogen-fixing capability was assessed using the nitrogen-free medium Burk’s N-Free, prepared with the following composition (per liter): sucrose, 20.0 g; K2HPO4, 0.64 g; KH2PO4, 0.16 g; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.20 g; NaCl, 0.20 g; CaSO4·2H2O, 0.05 g; and agar, 15 g. Supplementary components, including Na2MoO4·2H2O (0.05%, 5.0 mL) and FeSO4·7H2O (0.3%, 5.0 mL), were filter-sterilized before being added to the autoclaved medium. The pH was adjusted to 7.3 prior to sterilization (121 °C for 15 min). Strain G2T39 was cultured on this medium at 28 °C for 48 h, following the protocol described by Park et al. [24].

2.3. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Assembly of G2T39

The genome of B. velezensis strain G2T39 was sequenced using the Pacbio Sequel II and DNBSEQ platforms at the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI, Shenzhen, China). Four SMRT cell zero-mode waveguide arrays of sequencing were used by the PacBio platform to generate the subread set. PacBio subreads (lengths < 1 kb) were removed. The program Canu was used for self-correction. Draft genomic unitigs, which are uncontested groups of fragments, were assembled using Canu (Canu v2.2 [25] (useGrid = 0 and corOvlMemory = 4) from a high-quality corrected circular consensus sequence subread set. To improve genome accuracy, GATK (https://gatk.broadinstitute.org/hc/en-us (accessed on 7 October 2024)) was used to perform single-base corrections.

2.4. Genome Component

Gene prediction was conducted using Glimmer v3.02 [26] based on Hidden Markov Models (-l linear). Functional RNA elements were identified as follows: tRNAs using tRNAscan-SE v1.3.1; rRNAs using RNAmmer; and sRNA using the RFAM database. Tandem repeats were detected using Tandem Repeat Finder (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html (accessed on 7 October 2024)), and microsatellites/minisatellites were selected based on repeat unit length and frequency. Genomic islands were predicted using the Genomic Island Suite of Tools (GISTs) (http://www5.esu.edu/cpsc/bioinfo/software/GIST (accessed on 7 October 2024)), incorporating IslandPath-DIMOB, SIGI-HMM, and IslandPicker algorithms.

Functional annotation of predicted proteins was performed using BLAST+2.15.0 against the following seven databases: Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Gene Ontology (GO), Non-Redundant Protein Database databases (NR), UniProtKB (UniProtKB/TrEMBL and UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot), and EggNOG v6.0. Synteny analysis between G2T39 and related strains (Bacillus strains FZB42, SQR9, DSM 7, and XJ5) was conducted using MUMmer and BLAST. Core and pan-genomes were identified using CD-HIT with a 50% pairwise identity threshold and a 0.7 length difference cutoff. Gene family clustering involved a multi-step pipeline: (i) protein sequences were aligned using BLAST; (ii) redundant alignments were filtered using Solar; and (iii) gene family clustering was conducted using hcluster_sg. Moreover, the genome sequence data of G2T39 were uploaded to the Type (Strain) Genome Server (TYGS), a free bioinformatics platform available under https://tygs.dsmz.de (accessed on 7 September 2025), for whole-genome-based taxonomic and phylogenetic analysis [27]. Briefly, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) approach. Branch lengths were scaled in terms of the GBDP distance formula d5, and branch support was inferred from 100 pseudo-bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values > 60% are shown in the tree [27]. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) values between B. velezensis strain G2T39 and Bacillus reference strains were calculated with JspeciesWS [28]. Secondary metabolite biosynthetic clusters were identified using AntiSMASH v8.0.2 [29] with default parameters, referencing the MIBiG r4.0 database for structure and classification [30]. In addition, putative genes encoding carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) were annotated using the dbCAN3 meta server [31], which integrates HMMER (for domain prediction) [32], Hotpep (for short motif detection) [33], and DIAMOND (for similarity search against CAZy) [34]. Identified CAZymes genes were further analyzed using SignalP 5.0 [35] to predict the presence of N-terminal signal peptides indicative of potential secretion pathways.

3. Results

3.1. Biological Control Activity of B. velezensis Strain G2T39

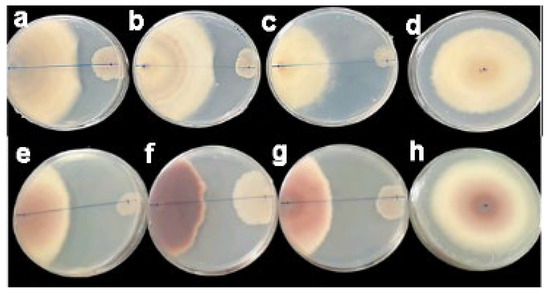

Here, we evaluated B. velenzensis G2T39 antagonistic activity against two fungal phytopathogens, C. gloeosporioides and F. oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (FOV). Indeed, in the presence of G2T39, the growth of C. gloeosporioides and F. oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (FOV) was impaired (Figure 1), with inhibition rates of 30% and 45%, respectively (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1.

Antimicrobial activity of B. velezensis G2T39 against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum. The assay, performed in triplicate, showed that in the presence of G2T39, the growth of C. gloeosporioides (a–c) and F. oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (e–g) was impaired. In contrast, the pathogenic fungi grew well without inhibition on the control plates (d,h).

3.2. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Phylogeny of B. velezensis Strain G2T39

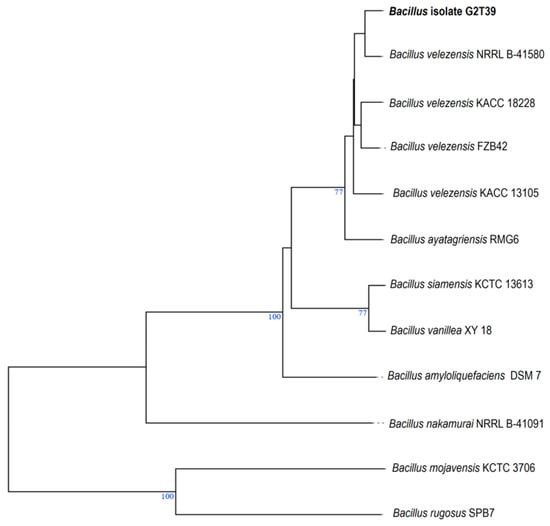

The genome of the endophytic bacteria strain G2T39 was sequenced using Oxford Nanopore technology. Prior to genomic and functional comparisons, we refined the identification and taxonomy of G2T39 using whole-genome-based phylogeny. Refinement of the presumptive affiliation of G2T39 was important to ensure accurate selection of its best reference strains for subsequent analysis, including structural synteny and pairwise average nucleotide identity. In a previous study, BlastN analysis that used only a partial 16S rRNA gene sequence (<1000 bp) was used to identify the strain G2T39 as B. velezensis [21]. Here, a genome-based phylogenetic tree produced with the TYGS platform revealed that G2T39 unambiguously belongs to the B. velezensis species (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Whole-genome phylogenetic tree built with the TYGS platform. About 10 strains closely related to G2T39 were automatically found by TYGS, and the tree was inferred from GBDP distances calculated from their genome sequences. Bacillus isolate G2T39 was shown in bold. Bootstrap data (values > 60%) from 100 replications are shown as a percent for each branch. Branch lengths were scaled in terms of the GBDP distance formula d5. The tree was manually edited and, where necessary, the names of reference strains were updated (e.g., Bacillus velezensis FZB42, was coined as Bacillus amyloliquefaciens subsp. plantarum FZB42 in the TYGS platform; https://tygs.dsmz.de (accessed on 7 September 2025).

Moreover, average nucleotide identity (ANI) calculations showed that G2T39 and several Bacillus velezensis strains shared the highest ANI BLAST (ANIb) and ANI Mummer (ANIm) values of 98.83% and 99.00%, respectively (Table 1). Clearly, both calculated ANIb and ANIm scores were higher than the 95–96% threshold proposed for delineating microbial species [36], confirming that G2T39 belongs to the B. velezensis species. Interestingly, G2T39 is also closely related to key Gram-positive Bacillus model strains for plant growth promotion and biocontrol, such as B. velezensis FZB42 [37] (Table 1; Figure 2).

Table 1.

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) values between Bacillus velezensis strain G2T39 and reference strains of Bacillus with available genome data.

3.3. Genomic Profiling of B. velezensis G2T39

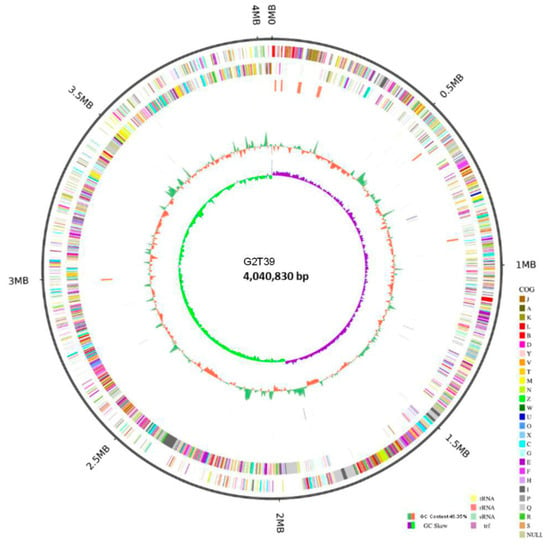

The genome of B. velezensis strain G2T39 (accession CP199939) consisted of a single circular chromosome measuring 4,040,830 base pairs (bp), with an average guanine–cytosine (GC) content of 46.35% (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Circular genome map of Bacillus velezensis G2T39. From the innermost to the outermost: ring 1 shows GC skew positive (light orange) and negative (blue) values; ring 2 for GC content, where green indicates values greater than the average and red indicates values lower than the average; ring 3 (reverse strand) and ring 4 (forward strand) show the distribution of CDSs (gray), tRNAs (light green), rRNAs (light red), ncRNAs (orange), and ncRNA regions (light blue); ring 5 indicates genome size (black line).

Eleven (11) databases, including VFDB, ARDB, CAZY, IPR, SWISSPROT, COG, CARD, GO, KEGG, NR, and T3SS, were used for gene function annotation of B. velezensis strain G2T39 (Table 2). The G2T39 genome comprises 4118 coding genes, including 3911 protein-coding sequences (CDSs), 87 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), 27 ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), 33 non-coding RNAs (ncRNs), and 4 small open reading frames (sORFs). Of these coding genes, 4090 (99.32%), 3444 (83.63%), 3323 (80.69%), 3030 (73.57%), 2561 (62.19%), and 2387 (57.96%) matched entries in the NR, IPR, SWISSPROT, COG, KEGG, and GO databases, respectively. Thus, four databases showed the highest match values (>70%), namely COG, IPR, NR, and Swiss-Prot, while a second group of databases included GO and KEGG (>50%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

G2T39 genes as annotated in different databases.

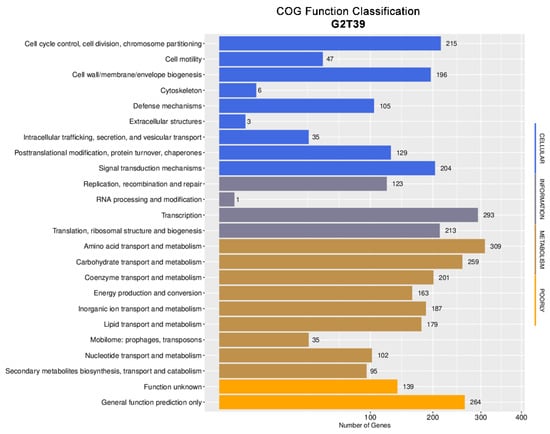

The COG database served as the basis for further analysis in this study. Within the COG database, 3100 genes were assigned to specific functional groups, while 403 were classified as having general function prediction or unknown function (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of genes across COG functional categories in the G2T39 strain genome.

The metabolism functional group was the most abundant, accounting for 1530 genes (49.35%), reflecting the importance of these functions for this bacterium. Within the metabolism class, the amino acid transport and metabolism category was the most abundant (20.19%), followed by the carbohydrate transport and metabolism category (13.13%).

Concerning KEGG annotation (Figure S1), 2571 genes were assigned to 42 KEGG pathways grouped into six classes, including cellular processes, environmental, genetic, human diseases, metabolism, and organismal systems. This high diversity of pathways, compared with B. velezensis bacterium Y89 with biocontrol potential [15], may reflect a possible adaptability of G2T39 to various environments. According to GO annotation, genes were classified into 34 functional groups within three main classes, including biological processes, cellular components, and molecular function (Figure S2). Of these classes, genes involved in biological processes were the most abundant. Within the biological process class, the number of genes related to cellular processes was the highest.

3.4. Genomic Comparison and Structural Synteny of B. velezensis G2T39

Genomic comparisons were performed between Bacillus velezensis G2T39 and four selected reference strains, namely B. velezensis FZB42, B. velezensis SQR9, B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7, and B. amyloliquefaciens XJ5 (Table 3). The reference strains were selected based on phylogenetic relationship and ANI data (Figure 2; Table 1). They included strains closely related to G2T39 and/or key Bacillus model strains for plant growth promotion and biocontrol commonly used in genomic comparative analyses (e.g., FZB42 and DSM 7) [3,38]. The five isolates shared similar genomic features (genome size of ca. 4 Mbp and ca. 4000 CDS), although they were isolated from contrasted environments, including soil and the rhizosphere. Analysis of mobile genetic elements and tandem repeats revealed that Bacillus velezensis G2T39 possesses a moderately dynamic genome relative to closely related strains. G2T39 harbors four prophage regions, including one intact element, indicating the presence of at least one potentially functional prophage alongside remnants of past phage integrations. This prophage load is comparable to that of B. amyloliquefaciens XJ5 but shows higher integrity than that of B. velezensis FZB42 and B. velezensis SQR9, which contain only incomplete or questionable elements. In contrast, B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7 exhibits a markedly more active mobilome, with eight prophage regions, including five intact. The tandem repeat landscape further supports an intermediate genome plasticity in G2T39: although it lacks microsatellites, it contains 36 minisatellites, a number exceeding those of XJ5 and SQR9 and comparable to FZB42, but considerably lower than that of the highly repetitive DSM7. Together, these features suggest that G2T39 maintains moderate genomic flexibility while avoiding the extensive repeat accumulation and prophage activity seen in more dynamic soil-associated strains such as DSM7. The main findings are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Genome characteristics of B. velezensis G2T39 compared to reference strains XJ5 (CP071970.1), FZB42 (NC_009725), SQR9 (CP006890), and DSM7 (NC_014551.1).

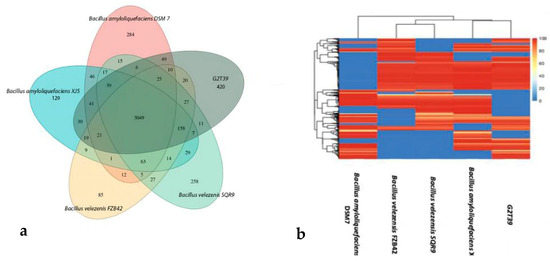

Moreover, a core- and pan-genome analysis including B. velezensis FZB42, B. velezensis SQR9, B. amyloliquefaciens QSM7, B. amyloliquefaciens XJ5, and G2T39 was performed. It was shown that the number of non-redundant pan-genes between G2T39 and the four reference strains was 5916, among which the number of core genes was 3049. The number of non-shared dispensable genes was 1091, of which 420 genes (7.09%), the highest number, were specific to G2T39 (Figure 5a). The heatmap of dispensable genes revealed that G2T39 and B. amyloliquefaciens XJ5 shared higher numbers, while B. velezensis FZB42 and B. velezensis SQR9 formed another branch. Moreover, B. amyloliquefaciens QSM7 formed a unique branch (Figure 5b). The overlaps among strains indicate a broad conservation of gene content, with differences mainly due to accessory genomic regions. The heatmap displays patterns of presence and absence across orthologous gene clusters, highlighting both conserved gene families and clusters that vary among strains. While the genomes share a large common backbone, distinct blocks of gene families are differentially represented, illustrating functional divergence at the accessory genome level.

Figure 5.

(a) Venn diagram showing the number of clusters of orthologous genes shared by G2T39, B. velezensis FZB42, B. velezensis SQR9, B. amyloquefaciens XJ5 and B. amyloquefaciens DSM 7, as well as unique genes. (b) Heatmap of dispensable genes cluster in G2T39, B. velezensis FZB42, B. velezensis SQR9, B. amyloquefaciens XJ5, and B. amyloquefaciens DSM 7. The top panel shows strain clusters, while gene similarity is shown in the middle, with different colors representing different levels of coverage in the heatmap. Color/depth is indicated in the top-right pic.

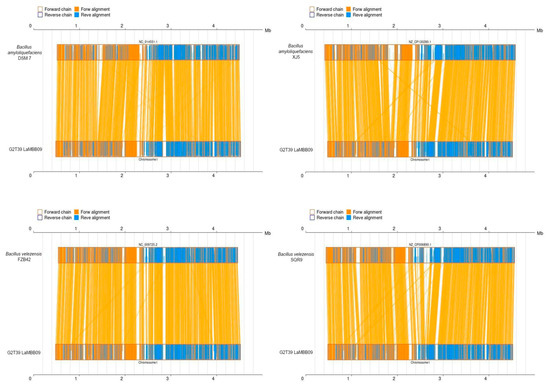

Pairwise synteny analysis revealed that strain G2T39 shares a highly conserved genome architecture with both B. amyloliquefaciens and B. velezensis strains (Figure 6). All four reference genomes exhibited strong macrosynteny with G2T39, with the central portion of the chromosome (≈0.5–3.8 Mb) showing dense forward alignments and highly conserved gene order. Only minor local inversions were detected within this core region. In contrast, the terminal regions of the chromosome displayed structural variability, including fragmented alignments and small-scale inversions, consistent with the presence of accessory genomic elements such as mobile elements and biosynthetic gene clusters. Among the reference strains, B. velezensis FZB42 and SQR9 showed the highest structural similarity to G2T39, whereas B. amyloliquefaciens DSM 7 and XJ5 exhibited slightly more localized rearrangements. No major chromosomal inversions, translocations, or large-scale rearrangements were observed in any comparison.

Figure 6.

Pairwise synteny of the genome of strain G2T39 with the genomes of other Bacillus (XJ5, DMS7, SQR9, and FZB42) at the amino acid level. Yellow boxes stand for forward chains and blue boxes stand for reverse chains within the upper and following sequence regions. Within the sequence boxes, yellow regions stand for nucleic acid sequences on the forward chain of this genome sequence, while blue regions stand for nucleic acid sequences on the reverse chain of this genome sequence. In the middle region between two sequences, yellow lines stand for forward alignments and blue lines stand for reverse complementary alignments.

3.5. Prediction of G2T39 Genome-Wide Secondary Metabolites and CAZymes

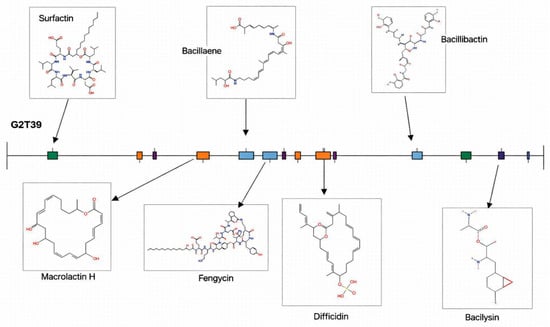

AntiSMASH v8.0.2 analysis identified 14 putative secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters in the G2T39 genome, supporting its potential for antimicrobial compound production (Table 4).

Table 4.

Secondary metabolites gene cluster types identified in the Bacillus velezensis G2T39 genome.

Fourteen biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) were identified, seven of which were annotated with high confidence based on sequence similarity to characterized clusters (Figure 7). The first cluster encodes a nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) highly similar to the surfactin-producing cluster previously reported in Bacillus velezensis FZB42 (BGC0000433.5). The second cluster corresponds to a polyketide synthase (PKS) with homology to the macrolactin H cluster of FZB42 and Jeotgalibacillus marinus (BGC0001383.3), which is also associated with the production of macrolactin B, macrolatin 1C, and macrolactin E. The third cluster is a hybrid NRPS-PKS type, showing high similarity to the bacillaene BGC of FZB42. The fourth is an NRPS-betalactone type cluster related to fengycin biosynthesis, while the fifth is associated with difficidin production and shares similarity with the PKS cluster of FZB42. The sixth cluster encodes an NRPS involved in bacillibactin synthesis (BGC0001185.8), and the seventh corresponds to the bacilysin biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC0001184.4) from FZB42. The remaining seven clusters displayed low similarity to known BGCs and were therefore considered putative. These include an NRPS cluster resembling the choline-type BGC of Aspergillus nidulans (BGC0002276.2), a terpene cluster associated with 4-hydroxy-3-nitrosobenzamide production from Streptomyces murayamaensis (BGC0000885.3), and another terpene cluster potentially involved in the biosynthesis of fumihopaside A and related compounds with anti-stress properties in Aspergillus fumigatus. Moreover, a PKS cluster was identified with similarity to that of Streptomyces griseus subsp. griseus NBRC 13350, which is known to produce 2-methoxy-5-methyl-6-(13-methyltetradecyl)-1,4-benzoquinone and related phenolic compounds. The G2T39 genome displays a notable genetic basis for anti-pathogen activity. Indeed, it encodes active compounds such as bacillaeane and difficidin, which are antibacterial compounds. Moreover, it also encodes antifungal compounds like surfactin and fengycin. Additionally, some dual antibacterial–antifungal compounds, such as macrolactin and bacilysin, were found in the genome. Notably, a gene cluster found in the G2T39 genome encodes a siderophore product (bacillibactin), which impedes the growth of bacterial and fungal competitors of phytopathogens by competing for essential ions and thus plays a significant role in expediting the procurement of ferric ions from minerals and rhizosphere compounds.

Figure 7.

Biosynthetic gene clusters identified in the B. velezensis G2T39 genome. Green (Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthesis Pathways), Orange (Polyketide synthases), Purple (Terpenes), Light blue (Hybrids), Blue (Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides) and Dark blue (others).

Moreover, the B. velezensis G2T39 strain genome contained 216 CAZyme genes grouped into 68 classes (Supplementary Table S2). Three had auxiliary activity, forty-nine were carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs), fifteen carbohydrate esterases, eighty-two glycoside hydrolases (GHs), sixty-four glycosyl transferases (GTs), and three polysaccharide lyase genes. Glycoside hydrolases and glycosyl transferases were shown to be abundant in the G2T39 genome compared to the closely related B. velezensis strains SQR9 and FZB42 (Table 5). Of the 49 CBMs, the most abundant in the G2T39 genome was the CBM50 class that contained 34 members, of which 12 genes were homologous (99% at least) to CBM50 belonging to various Bacillus species (Supplementary Table S3). The 82 were grouped into 32 families of which GH13 was the most abundant with six genes highly homologous (99–100%) to GH13 belonging to diverse Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and B. velezensis. Additionally, GH1, GH43, GH30, GH51, GH73, GH46, GH32, GH18, GH13, GH0, GH1, GH126, GH23, and GH4 were highly homologous (99–100%) to corresponding families in diverse Bacillus species (Supplementary Table S1). Of the 64 glycosyl transferases, GT2 was the most abundant in the G2T39 genome, with 25 genes, of which 13 were highly homologous (99–100%) to GT2 belonging to different Bacillus, including B. velezensis and B. amyloliquefaciens. The G2T39 genome also contains eight GT4 genes, five GT51 genes, two GT1 genes, one GT0 gene, and one GT8 gene, all of which were highly homologous to those belonging to different Bacillus species.

Table 5.

Comparison of CAZymes in the genomes of Bacillus velezensis G2T39 and related Bacillus FZB42 and SQR9.

3.6. Genetic Basis of G2T39 Plant Defense Activity

The G2T39 genome possessed genes involved in pathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) and induced system resistance (ISR) (Table 6). Four genes, including tuf, efp, and tsf, encoding translation elongation factors, and dacA, encoding D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase, are involved in PTI. Moreover, four genes, including ilvB and alsS, associated with acetolactate synthase, metC, encoding cystathionine beta-lyase, and luxS, encoding S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase, are involved in ISR.

Table 6.

Plant defense genes identified in the Bacillus velezensis G2T39 genome.

3.7. Genetic Basis of Genes Associated with Nitrogen Metabolism/Fe–S Cluster Assembly and Nitrogen Regulation in G2T39 Genome

G2T39 could grow on Burk’s medium after 48 h of culture, showing a presumptive nitrogen-fixing capacity (Supplementary Figure S3). Moreover, genome sequencing and analysis showed that the G2T39 genome harbored genes directly involved in the biosynthesis of the nitrogenase, including an nifS gene cluster encoding for a cysteine desulfurase, skfB encoding a putative Fe-S oxydoreductase, sufB encoding a Fe-S cluster assembly scaffold protein, iscU, nifU encoding a Fe-S cluster assembly scaffold protein, and the gene iscA encoding an Fe-S cluster assembly iron-binding protein. Additionally, the G2T39 genome exhibited two nitrogenase regulatory genes, including fixB, which encodes an electron transfer flavoprotein, an enzyme involved in nitrogen fixation, the gene glnK, encoding the nitrogenase regulatory protein PII, and the gene degU, coding for a two-component regulator of nitrogenase (Table 7).

Table 7.

Nitrogen metabolism genes identified in the G2T39 genome.

3.8. Genetic Basis for Plant Growth-Promoting Activity of G2T39

The B. velezensis G2T39 genome exhibited different genes encoding proteins predicted to be associated with multiple plant growth-promoting functions, including nitrogen metabolism, phosphate metabolism, biofilm formation, siderophore production, riboflavin synthesis, zinc solubilization, stress tolerance, nitrate reduction, lactate metabolism, potassium homeostasis, magnesium transport, and cytochrome c biogenesis. Despite the presence of multiple genes encoding growth-promoting functions in the G2T39 genome, only genes 80% homologous to databases were selected. Indeed, the genome of B. velenzensis strain G2T39 harbored different genes involved in phosphate metabolism, including glpQA, encoding a glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase, phyC, encoding a phytase, and the genes ugpE, ugpB, and ugpA (Table 8).

Table 8.

Genes involved in phosphate metabolism.

The G2T39 genome harbored various genes involved in different plant growth functions, as shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Putative genes involved in other plant growth-promoting functions in the G2T39 genome. Predicted genes were selected when homology was superior to 80%.

4. Discussion

Since endophytic Bacillus can be considered an important multifaceted toolbox for agriculture [73], better characterization of the strain G2T39 appeared to be urgent. A phylogenomic analysis revealed that B. velezensis strain G2T39 exhibited a high degree of homology with B. velezensis NRRL B-41580, the type strain for B. velezensis bacterium [74]. Moreover, strain G2T39 was also closely related to key Gram-positive Bacillus model strains for plant growth promotion and biocontrol, such as B. velezensis FZB42 [37] and B. velezensis SQR9. These data were further supported by average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis. B. velezensis SQR9 was isolated from the cucumber rhizosphere, while FZB42 was isolated from the beet rhizosphere [75]. The close relatedness between these rhizospheric Bacillus strains and G2T39 isolated from C. retusa stems, has no significant correlation with their origin.

Besides its capacity to control Fusarium from temperate zones, as already evidenced [21], G2T39 could also control phytopatogens such as C. gloeosporioides and F. oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum from tropical zones, showing its broad-spectrum biocontrol potential. Biological control potential has also been reported for B. velenzensis strain BN [18] and its closely related Bacillus strains such as SQR9 [76] and FZB42 [77]. Moreover, various Bacillus isolates close to B. subtilis, B. atrophaeus, B. amyloliquefaciens, B. cereus, B. licheniformis, and B. pumilus have been described as biocontrol agents against different Fusarium species, [20,22,77,78,79,80] sometimes exhibiting broad-spectrum activity, as evidenced with B. velezensis BN (18).

This antagonistic charateristic of G2T39 could be due to the presence in its genome of nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), macrolactin, fengycin, difficidin, bacillibactin, and bacilysin, all of which are antibacterial compounds. Additionally, it also encodes antifungal compounds like surfactin and fengycin. Inhibitory activity of B. velezensis and other Bacillus can be attributed to several key factors related to their biological and biochemical properties, such as production of antimicrobial compounds, siderophore production, and the production of hydrolytic enzymes [77]. Indeed, the Bacillus genus is known to produce a huge diversity of antibacterial compounds [81,82]. Moreover, genome sequencing and analysis have recently revealed that the ability of B. velezensis to function as a biocontrol bacterium is mainly due to the fact that this species produces various secondary metabolites and enzymes [14,18,83]. Indeed, in general, B. velezensis species produces secondary metabolites such as antimicrobial cyclic lipopeptides synthesized by NRPS and polyketides synthesized by polyketide synthases, which are very important for their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity [15,18]. The G2T39 genome harbored an NRPS closely related to the surfactin-producing cluster previously reported in B. velezensis FZB42 [84].

Moreover, antifungal activities from microbes can also be mediated by enzymes able to hydrolyze fungi chitin [85]. The most well-known enzymes associated with such functions are CAZymes, which cleave polysaccharides and other structural compounds and thus allow antifungal activities in plant growth-promoting bacteria such as Bacillus [15]. CAZyme prediction of the endophytic strain B. velezensis G2T39 suggested that this strain might play a significant role in antifungal production and activity. Indeed, the G2T39 strain harbors the CBM50 family, which contains 34 members known to promote antifungal activity by binding to the chitinous component of the fungal cell wall, as already evidenced [86,87]. Of diverse GHs, the G2T39 genome harbored GH18, GH19, GH23, and GH73, which can act as chitinases or peptidoglycanases, conferring antibacterial and antifungal properties simultaneously. CAZymes were shown to play an important role in spatial competition, nutrient acquisition, and suppression of the sugarcane red rot pathogen in YC89, an endophytic B. velezensis [15].

It is also known that the biocontrol effects exerted by antagonistically acting B. velezensis can be due to the stimulation or induction of plant resistance through ISR, PTI, and ETI [15,84]. It was shown that the G2T39 genome harbored genes such as tuf, efp, and tsf, encoding translation elongation factors that are involved in pathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) [41,88]. The G2T39 genome also encoded acetolactate synthase, cystathionine beta-lyase, S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase, and alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase, which are involved in ISR in B. velezensis YC89 [15].

A number of putative genes related to plant growth-promoting functions metabolism were also identified in the G2T39 genome. A preliminary and presumptive nitrogen-fixing capacity was shown using Burk’s medium [24]. Further experiments using acetylene reduction or 15N incorporation should confirm these results. Moreover, putative genes involved in nitrogen metabolism in the G2T39 genome included a system comprising nifS, nifU, and nifB that encodes for nitrogenase. The nifU and nifS system has been characterized as very important for nitrogenase biosynthesis. Indeed, the nifU and nifS genes encode components of a cellular machinery dedicated to the assembly of [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] clusters required for growth under nitrogen-fixing conditions [47]. Moreover, NifB, which is the key protein involved in the synthesis of cofactors of all nitrogenases [46], was also found in the G2T39 genome. The genome also harbors the gene GlnK, which encodes protein PII that plays a key role in regulating nitrogenases [48,49]. Additionally, the gene fixB, which encodes flavoprotein involved in electron transfer for nitrogenase activation, as evidenced in Azotobacter vinelandii [45], was evidenced in G2T39. Moreover, the narL/fixJ system, which is involved in activating the expression of nitrogen fixation genes in response to low oxygen concentrations [89], was also found in the G2T39 genome. Recent studies have shown that B. velezensis strains are able to regulate nitrogen fixation [90,91]. However, characterization of nitrogenase-fixing systems in B. velezensis is still scarce, except that recent works pointed out the presence of guaB and cysK, cysE, and ilvE in B. velezensis strain CH1 [83]. The G2T39 strain is an endophytic bacteria isolated from the stem of a medicinal leguminous plant and, as such, does not possess nodulation genes and should not nodulate.

The G2T39 genome harbors a complex genetic system involved in phosphate metabolism, including a mixture of different pathways. Indeed, the G2T39 genome harbors a phytase homologous to PhyC isolated from Bacillus subtilis [55]. Phytases are enzymes involved in the catalysis of phytic acid hydrolysis by releasing phosphorus and consequently increasing its absorption by plants or animals [92]. Knowledge of Phyc functioning mechanisms is still scarce. However, the gene pstA in the genome of G2T39 may play a crucial role by allowing phosphate transport across the membrane, particularly in low-phosphate environments, which may therefore increase phytase activities. Indeed, the depletion of phyC and a pst gene was shown to increase the production of this phytase in B. subtilis BD170 [93]. Additionally, the G2T39 genome harbors the genes glpQA, ugpE, ugpB, ugpC, which are found in bacteria and encode glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterases (GDPDs) involved in phospholipid hydrolysis. GDPDs have also been identified from archaea and bacteria [9,94,95]. These GDPDs have divergent pathways of functioning. For example, in Escherichia coli, UgpQ functions in the absence of other proteins encoded by the ugp operon and requires Mg2+, Mn2+, or Co2, in contrast to Ca2+-dependent periplasmic glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase GlpQ [95]. Additionally, E. coli uses a complex phosphonate pathway that involves not only the uqp gene clusters but also a pst cluster [56]. This is the first report of a complex phosphate metabolism system in an endophytic bacteria isolated from C. retusa, a medicinal plant. Since lipids constitute an important component of plant cells, GDPDs have been reported to be induced under Pi deficiency in several plant species [54,96,97]. However, the presence of this complex phosphate metabolism system in a plant endophytic bacteria may be very important for plant growth in phosphate-deficient environments.

5. Conclusions

This is the first report of the complete genome sequencing and analysis of an endophytic B. velezensis from the medicinal plant C. retusa. Our findings indicate that B. velezensis strain G2T39 could serve as a potential biocontrol agent to promote plant growth. This study demonstrated that G2T39 strain harbors multiple putative genes related to nitrogen metabolism/Fe–S cluster assembly and nitrogen regulation, phosphate metabolism, antifungal activity, plant resistance inducer biosynthesis, and various plant growth-promoting properties such as biofilm formation, siderophore biosynthesis, and zinc solubilization, making G2T39 a potential biocontrol agent and a biofertilizer.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms14010123/s1, Figure S1: Distribution of genes across KEGG functional categories in G2T39 genome; Figure S2: Distribution of genes across GO functional categories in the G2T39 genome; Figure S3: Growth of strain G2T39 on Burk’s medium; Table S1: Inhibition rate of B. velezensis strain G2T39 on pathogenic fungi; Table S2: List of annotated CAZymes in the genome of G2T39; Table S3: relative abundance of different CAZymes classes in the genome of G2T39.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z.; methodology, A.Z., A.T.E.E. and R.K.F.; software, A.Z., A.T.E.E. and R.K.F.; validation, A.Z. and R.K.F.; formal analysis, A.Z. and A.T.E.E.; investigation, E.S.S.A. and E.P.-M.K.B.; resources, Z.G.C.K.-Z.; data curation, A.Z., A.T.E.E. and R.K.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.S.A.; writing—review and editing, A.Z., R.K.F., A.T.E.E. and Z.G.C.K.-Z.; visualization, A.Z., R.K.F. and A.T.E.E.; supervision, A.Z.; project administration, A.Z.; funding acquisition, A.Z. and Z.G.C.K.-Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequence of the isolate G2T39 was deposited at NCBI under the GenBank accession number CP199939.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Laboratoire Central de Biotechnologies (LCB, CNRA) and the Laboratoire de Microbiologie, Biotechnologies et Bio-informatique (LaMBB, UMRI SAPT, INP-HB) for funding sequencing fees.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tatineni, S.; Hein, G.L. Plant Viruses of Agricultural Importance: Current and Future Perspectives of Virus Disease Management Strategies. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Choudhary, D.; Bali, S.; Bandral, S.S.; Singh, V.; Ahmad, M.A.; Rani, N.; Singh, T.G.; Chandrasekaran, B. Pesticides: An Alarming Detrimental to Health and Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykogianni, M.; Bempelou, E.; Karamaouna, F.; Aliferis, K.A. Do Pesticides Promote or Hinder Sustainability in Agriculture? The Challenge of Sustainable Use of Pesticides in Modern Agriculture. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzevari, S.; Hofman, J. A Worldwide Review of Currently Used Pesticides’ Monitoring in Agricultural Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 812, 152344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonthakaew, N.; Panbangred, W.; Songnuan, W.; Intra, B. Plant Growth-Promoting Properties of Streptomyces spp. Isolates and Their Impact on Mung Bean Plantlets’ Rhizosphere Microbiome. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 967415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, M.; Kaddouri, K.; Badaoui, B.; Bouhnik, O.; Chaddad, Z.; Perez-Tapia, V.; Lamin, H.; Alami, S.; Lamrabet, M.; Abdelmoumen, H.; et al. Plant Growth Promoting Activities of Pseudomonas sp. and Enterobacter sp. Isolated from the Rhizosphere of Vachellia gummifera in Morocco. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2023, 99, fiad114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazala, I.; Chiab, N.; Saidi, M.N.; Gargouri-Bouzid, R. The Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria Strain Bacillus mojavensis I4 Enhanced Salt Stress Tolerance in Durum Wheat. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiesewalter, H.T.; Lozano-Andrade, C.N.; Wibowo, M.; Strube, M.L.; Maróti, G.; Snyder, D.; Jørgensen, T.S.; Larsen, T.O.; Cooper, V.S.; Weber, T.; et al. Genomic and Chemical Diversity of Bacillus subtilis Secondary Metabolites against Plant Pathogenic Fungi. mSystems 2021, 6, e00770-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Lai, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y. Expression and Characterization of a Novel Glycerophosphodiester Phosphodiesterase from Pyrococcus furiosus DSM 3638 That Possesses Lysophospholipase D Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Pi, H.; Chandrangsu, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xiong, H.; Helmann, J.D.; Cai, Y. Antagonism of Two Plant-Growth Promoting Bacillus velezensis Isolates Against Ralstonia solanacearum and Fusarium oxysporum. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshmirshekan, A.; de Souza Mesquita, L.M.; Ventura, S.P.M. Biocontrol Manufacturing and Agricultural Applications of Bacillus velezensis. Trends Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 986–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z.; Cai, S.; Wang, S.; Li, Y. Bacillus velezensis BVE7 as a Promising Agent for Biocontrol of Soybean Root Rot Caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1275986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magno-Pérez-Bryan, M.C.; Martínez-García, P.M.; Hierrezuelo, J.; Rodríguez-Palenzuela, P.; Arrebola, E.; Ramos, C.; de Vicente, A.; Pérez-García, A.; Romero, D. Comparative Genomics Within the Bacillus Genus Reveal the Singularities of Two Robust Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Biocontrol Strains. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2015, 28, 1102–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaid, D.S.; Cai, S.; Hu, C.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. Comparative Genome Analysis Reveals Phylogenetic Identity of Bacillus velezensis HNA3 and Genomic Insights into Its Plant Growth Promotion and Biocontrol Effects. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02169-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Liu, L.; Luo, Y.; Rao, X.; Di, Y.; Liu, H.; Qian, Z.; Shen, Q.; He, L.; Li, F. Complete Genome Sequence of Biocontrol Strain Bacillus velezensis YC89 and Its Biocontrol Potential against Sugarcane Red Rot. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1180474, Erratum in Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1235695. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1235695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Jiang, H.; Ma, K.; Wang, X.; Liang, S.; Cai, Y.; Jing, Y.; Tian, B.; Shi, X. Genome Sequencing and Analysis of Bacillus velezensis VJH504 Reveal Biocontrol Mechanism against Cucumber Fusarium Wilt. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1279695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Song, Y.; An, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, G. Soil Microorganisms: Their Role in Enhancing Crop Nutrition and Health. Diversity 2024, 16, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wei, S.; Leng, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Secondary Metabolite Exploration of the Novel Bacillus velezensis BN with Broad-Spectrum Antagonistic Activity against Fungal Plant Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1498653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.-C.; Liu, C.-H.; Wang, B.-T.; Xue, Y.-R. Genomic and Metabolic Traits Endow Bacillus velezensis CC09 with a Potential Biocontrol Agent in Control of Wheat Powdery Mildew Disease. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 196, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Gao, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, F.; Du, Y.; Moe, T.S.; Munir, I.; Xue, J.; Zhang, X. The Endophytic Bacteria Bacillus velezensis Lle-9, Isolated from Lilium Leucanthum, Harbors Antifungal Activity and Plant Growth-Promoting Effects. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahoty, E.S.S.; Fossou, R.K.; Magot, F.; Ebou, A.T.E.; Kouadjo-Zézé, C.G.Z.; Marchesseau, B.; Spina, R.; Grosjean, J.; Laurain-Mattar, D.; Slezack, S.; et al. Fusarium Antagonism Potential and Metabolomics Analysis of Endophytic Bacteria Isolated from Crotalaria retusa L., a Traditional Medicinal Plant in Côte d’Ivoire. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2025, 372, fnaf056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munakata, Y.; Gavira, C.; Genestier, J.; Bourgaud, F.; Hehn, A.; Slezack-Deschaumes, S. Composition and Functional Comparison of Vetiver Root Endophytic Microbiota Originating from Different Geographic Locations That Show Antagonistic Activity towards Fusarium graminearum. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 243, 126650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolivar-Anillo, H.J.; González-Rodríguez, V.E.; Cantoral, J.M.; García-Sánchez, D.; Collado, I.G.; Garrido, C. Endophytic Bacteria Bacillus subtilis, Isolated from Zea mays, as Potential Biocontrol Agent against Botrytis cinerea. Biology 2021, 10, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Kim, C.; Yang, J.; Lee, H.; Shin, W.; Kim, S.; Sa, T. Isolation and Characterization of Diazotrophic Growth Promoting Bacteria from Rhizosphere of Agricultural Crops of Korea. Microbiol. Res. 2005, 160, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, S.; Walenz, B.P.; Berlin, K.; Miller, J.R.; Bergman, N.H.; Phillippy, A.M. Canu: Scalable and Accurate Long-Read Assembly via Adaptive k-Mer Weighting and Repeat Separation. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delcher, A.L.; Bratke, K.A.; Powers, E.C.; Salzberg, S.L. Identifying Bacterial Genes and Endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Carbasse, J.S.; Peinado-Olarte, R.L.; Göker, M. TYGS and LPSN: A Database Tandem for Fast and Reliable Genome-Based Classification and Nomenclature of Prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D801–D807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Oliver Glöckner, F.; Peplies, J. JSpeciesWS: A Web Server for Prokaryotic Species Circumscription Based on Pairwise Genome Comparison. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Vader, L.; Szenei, J.; Reitz, Z.L.; Augustijn, H.E.; Cediel-Becerra, J.D.D.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Koetsier, R.A.; Williams, S.E.; et al. antiSMASH 8.0: Extended gene cluster detection capabilities and analyses of chemistry, enzymology, and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W32–W38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zdouc, M.M.; Blin, K.; Louwen, N.L.L.; Navarro, J.; Loureiro, C.; Bader, C.D.; Bailey, C.B.; Barra, L.; Booth, T.J.; Bozhüyük, K.A.J.; et al. MIBiG 4.0: Advancing Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Curation through Global Collaboration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D678–D690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ge, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Yin, Y. dbCAN3: Automated Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme and Substrate Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W115–W121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S.R. Accelerated Profile HMM Searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busk, P.K. Accurate, Automatic Annotation of Peptidases with Hotpep-Protease. Green. Chem. Eng. 2020, 1, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D.H. Fast and Sensitive Protein Alignment Using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Sønderby, C.K.; Petersen, T.N.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 5.0 Improves Signal Peptide Predictions Using Deep Neural Networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, M.; Rosselló-Móra, R. Shifting the Genomic Gold Standard for the Prokaryotic Species Definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19126–19131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Wang, C.; Song, X.; Ding, X.; Wu, L.; Wu, H.; Gao, X.; Borriss, R. Bacillus velezensis FZB42 in 2018: The Gram-Positive Model Strain for Plant Growth Promotion and Biocontrol. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2491, Erratum in Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, F.; Chen, X.; Fu, Z.; Wang, X.; Guo, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, B. Genome and Transcriptome Analysis to Elucidate the Biocontrol Mechanism of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens XJ5 against Alternaria Solani. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.N.; Chamorro-Veloso, N.; Costa, P.; Cádiz, L.; Del Canto, F.; Venegas, S.A.; López Nitsche, M.; Coloma-Rivero, R.F.; Montero, D.A.; Vidal, R.M. Deciphering Additional Roles for the EF-Tu, l-Asparaginase II and OmpT Proteins of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hummels, K.R.; Kearns, D.B. Suppressor mutations in ribosomal proteins and FliY restore Bacillus subtilis swarming motility in the absence of EF-P. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Borriss, R.; Danchin, A.; Harwood, C.R.; Médigue, C.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Sekowska, A.; Vallenet, D. Bacillus subtilis, the model Gram-positive bacterium: 20 years of annotation refinement. Microb. Biotechnol. 2018, 11, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Belda, E.; Sekowska, A.; Le Fèvre, F.; Morgat, A.; Mornico, D.; Ouzounis, C.; Vallenet, D.; Médigue, C.; Danchin, A. An updated metabolic view of the Bacillus subtilis 168 genome. Microbiology 2013, 159, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.M.; de Jong, A.; Kloosterman, T.G.; Kuipers, O.P.; Saraiva, L.M. The Staphylococcus aureus α-Acetolactate Synthase ALS Confers Resistance to Nitrosative Stress. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Grenier, D.; Yi, L. Regulatory Mechanisms of the LuxS/AI-2 System and Bacterial Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01186-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alleman, A.B.; Garcia Costas, A.; Mus, F.; Peters, J.W. Rnf and Fix Have Specific Roles during Aerobic Nitrogen Fixation in Azotobacter vinelandii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e01049-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S. Functional Analysis of Multiple nifB Genes of Paenibacillus Strains in Synthesis of Mo-, Fe- and V-Nitrogenases. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Curatti, L.; Rubio, L.M. Evidence for nifU and nifS Participation in the Biosynthesis of the Iron-Molybdenum Cofactor of Nitrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 37016–37025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glöer, J.; Thummer, R.; Ullrich, H.; Schmitz, R.A. Towards Understanding the Nitrogen Signal Transduction for Nif Gene Expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae. FEBS J. 2008, 275, 6281–6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chen, M.; Xie, Z.; Yan, Y.; Li, H.; Fan, Y.; Ping, S.; Lin, M.; Elmerich, C. Involvement of GlnK, a PII Protein, in Control of Nitrogen Fixation and Ammonia Assimilation in Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501. Arch. Microbiol. 2008, 190, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Castro, C.; Saini, A.; Outten, F.W. Fe-S Cluster Assembly Pathways in Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2008, 72, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D.R. On the Path to [Fe-S] Protein Maturation: A Personal Perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasumura, A.; Abe, S.; Tanaka, T. Involvement of Nitrogen Regulation in Bacillus subtilis degU Expression. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 5162–5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Rensing, C.; Han, D.; Xiao, K.-Q.; Dai, Y.; Tang, Z.; Liesack, W.; Peng, J.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, F. Genome-Resolved Metagenomics Reveals Distinct Phosphorus Acquisition Strategies between Soil Microbiomes. mSystems 2022, 7, e01107-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, P.; Pandey, B.K.; Verma, L.; Giri, J. A Novel Glycerophosphodiester Phosphodiesterase Improves Phosphate Deficiency Tolerance in Rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerovuo, J.; Lauraeus, M.; Nurminen, P.; Kalkkinen, N.; Apajalahti, J. Isolation, Characterization, Molecular Gene Cloning, and Sequencing of a Novel Phytase from Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2079–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, R.; Neves, H.I.; Spira, B. Phosphate Uptake by the Phosphonate Transport System PhnCDE. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrangsu, P.; Huang, X.; Gaballa, A.; Helmann, J.D. Bacillus subtilis FolE Is Sustained by the ZagA Zinc Metallochaperone and the Alarmone ZTP under Conditions of Zinc Deficiency. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 112, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitreschak, A.G.; Rodionov, D.A.; Mironov, A.A.; Gelfand, M.S. Regulation of Riboflavin Biosynthesis and Transport Genes in Bacteria by Transcriptional and Translational Attenuation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3141–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Ying, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, P. Enhancing the Biosynthesis of Riboflavin in the Recombinant Escherichia coli BL21 Strain by Metabolic Engineering. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1111790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peuckert, F.; Miethke, M.; Albrecht, A.G.; Essen, L.; Marahiel, M.A. Structural Basis and Stereochemistry of Triscatecholate Siderophore Binding by FeuA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7924–7927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peuckert, F.; Ramos-Vega, A.L.; Miethke, M.; Schwörer, C.J.; Albrecht, A.G.; Oberthür, M.; Marahiel, M.A. The Siderophore Binding Protein FeuA Shows Limited Promiscuity toward Exogenous Triscatecholates. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podkowa, K.J.; Briere, L.-A.K.; Heinrichs, D.E.; Shilton, B.H. Crystal and Solution Structure Analysis of FhuD2 from Staphylococcus aureus in Multiple Unliganded Conformations and Bound to Ferrioxamine-B. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 2017–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delepelaire, P. Bacterial ABC Transporters of Iron Containing Compounds. Res. Microbiol. 2019, 170, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariotti, P.; Malito, E.; Biancucci, M.; Lo Surdo, P.; Mishra, R.P.N.; Nardi-Dei, V.; Savino, S.; Nissum, M.; Spraggon, G.; Grandi, G.; et al. Structural and Functional Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus Virulence Factor and Vaccine Candidate FhuD2. Biochem. J. 2013, 449, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusei-Danso, F.; Khaja, F.T.; DeSantis, M.; Jeffrey, P.D.; Dubnau, E.; Demeler, B.; Neiditch, M.B.; Dubnau, D. Structure-Function Studies of the Bacillus subtilis Ric Proteins Identify the Fe-S Cluster-Ligating Residues and Their Roles in Development and RNA Processing. mBio 2019, 10, e01841-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corredor-Rozo, Z.-L.; Marquez-Ortiz, R.; Velandia-Romero, M.L.; Abril, D.; Madroñero, J.; Prada, L.F.; Vanegas-Gomez, N.; García, B.; Echeverz, M.; Calderón-Peláez, M.-A.; et al. Deciphering the Function of Com_YlbF Domain-Containing Proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2025, 207, e0006125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomjan, R.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, D. YshB Promotes Intracellular Replication and Is Required for Salmonella Virulence. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00314-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Vivián, C.; Cabello, P.; Martínez-Luque, M.; Blasco, R.; Castillo, F. Prokaryotic Nitrate Reduction: Molecular Properties and Functional Distinction among Bacterial Nitrate Reductases. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 6573–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Kolter, R.; Losick, R. A Widely Conserved Gene Cluster Required for Lactate Utilization in Bacillus subtilis and Its Involvement in Biofilm Formation. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 2423–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, K.U.; Josts, I.; Mosbahi, K.; Kelly, S.M.; Byron, O.; Smith, B.O.; Walker, D. The Potassium Binding Protein Kbp Is a Cytoplasmic Potassium Sensor. Structure 2016, 24, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Hederstedt, L. Composition and Function of Cytochrome c Biogenesis System II. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 4179–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, T.A.D.N.D.; Vendruscolo, E.P.; Binotti, F.F.D.S.; Costa, E.; Lima, S.F.D.; Sant’Ana, G.R.; Bortolheiro, F.P.D.A.P. Nicotinamide Increases the Physiological Performance and Initial Growth of Maize Plant. Int. J. Agron. 2024, 2024, 5567314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Shukla, A.K.; Singh, A.K. Endophytic Bacillus Species as Multifaceted Toolbox for Agriculture, Environment, and Medicine. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, E.G.; Campos, G.M.; Viana, M.V.C.; Gomes, G.C.; Rodrigues, D.L.N.; Aburjaile, F.F.; Fonseca, B.B.; De Araújo, M.R.B.; Da Costa, M.M.; Guedon, E.; et al. The Research on the Identification, Taxonomy, and Comparative Genomics Analysis of Nine Bacillus velezensis Strains Significantly Contributes to Microbiology, Genetics, Bioinformatics, and Biotechnology. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1544934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, B.; Höding, B.; Kübart, S.; Workie, M.; Junge, H.; Schmiedeknecht, G.; Grosch, R.; Bochow, H.; Hevesi, M. Use of Bacillus Subtilis as Biocontrol Agent. I. Activities and Characterization of Bacillus subtilis Strains/Anwendung von Bacillus subtilis Als Mittel Für Den Biologischen Pflanzenschutz. I. Aktivitäten Und Charakterisierung von Bacillus sibtills-Stämmen. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 1998, 105, 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wang, D.; Qiu, M.; Feng, H.; Zhang, N.; Shen, Q. Enhanced Control of Cucumber Wilt Disease by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 by Altering the Regulation of Its DegU Phosphorylation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2941–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwaremwe, C.; Yue, L.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R. An Endophytic Strain of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Suppresses Fusarium oxysporum Infection of Chinese Wolfberry by Altering Its Rhizosphere Bacterial Community. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 782523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schisler, D.A.; Khan, N.I.; Boehm, M.J.; Slininger, P.J. Greenhouse and Field Evaluation of Biological Control of Fusarium Head Blight on Durum Wheat. Plant Dis. 2002, 86, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, S.; Siddiqui, Z.A.; Ahmad, I. Evaluation of Fluorescent Pseudomonads and Bacillus Isolates for the Biocontrol of a Wilt Disease Complex of Pigeonpea. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 21, 729–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitullo, D.; Di Pietro, A.; Romano, A.; Lanzotti, V.; Lima, G. Role of New Bacterial Surfactins in the Antifungal Interaction between Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Fusarium oxysporum. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, R.; Khushhal, S.; Asif, T.; Mubeen, S.; Saranraj, P.; Sayyed, R.Z. Inhibition of Bacterial and Fungal Phytopathogens Through Volatile Organic Compounds Produced by Pseudomonas sp. In Secondary Metabolites and Volatiles of PGPR in Plant-Growth Promotion; Sayyed, R.Z., Uarrota, V.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 95–118. ISBN 978-3-031-07558-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ongena, M.; Jacques, P. Bacillus Lipopeptides: Versatile Weapons for Plant Disease Biocontrol. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Su, S.; Bo, S.; Zheng, C.; Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Xu, S.; Wang, X.; Gao, P.; Fan, K.; et al. A Bacillus velezensis Strain Isolated from Oats with Disease-Preventing and Growth-Promoting Properties. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.P.; Dietel, K.; Rändler, M.; Schmid, M.; Junge, H.; Borriss, R.; Hartmann, A.; Grosch, R. Effects of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 on Lettuce Growth and Health under Pathogen Pressure and Its Impact on the Rhizosphere Bacterial Community. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edreva, A. Pathogenesis-related proteins: Research progress in the last 15 years. Gen. Appl. Plant Physiol. 2005, 31, 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, R.; Kombrink, A.; Motteram, J.; Loza-Reyes, E.; Lucas, J.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Thomma, B.P.H.J.; Rudd, J.J. Analysis of Two in Planta Expressed LysM Effector Homologs from the Fungus Mycosphaerella graminicola Reveals Novel Functional Properties and Varying Contributions to Virulence on Wheat. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentlak, T.A.; Kombrink, A.; Shinya, T.; Ryder, L.S.; Otomo, I.; Saitoh, H.; Terauchi, R.; Nishizawa, Y.; Shibuya, N.; Thomma, B.P.H.J.; et al. Effector-Mediated Suppression of Chitin-Triggered Immunity by Magnaporthe Oryzae Is Necessary for Rice Blast Disease. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, G.; Zipfel, C.; Robatzek, S.; Niehaus, K.; Boller, T.; Felix, G. The N Terminus of Bacterial Elongation Factor Tu Elicits Innate Immunity in Arabidopsis Plants. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 3496–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xu, F.; Ren, X.; Chen, S. Functional Analysis of the fixL/fixJ and fixK Genes in Azospirillum Brasilense Sp7. Ann. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Jiang, X.; He, X.; Wu, Z.; Lv, Q.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; He, H.; Liu, J. Bacillus velezensis 20507 Promotes Symbiosis between Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110 and Soybean by Secreting Flavonoids. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1572568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Fu, Y.; Jia, L.; Li, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Xuan, W.; et al. The Beneficial Rhizobacterium Bacillus velezensis SQR9 Regulates Plant Nitrogen Uptake via an Endogenous Signaling Pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 3388–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vats, P.; Banerjee, U.C. Production Studies and Catalytic Properties of Phytases (Myo-Inositolhexakisphosphate Phosphohydrolases): An Overview. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2004, 35, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolanto, A.; Von Weymarn, N.; Kerovuo, J.; Ojamo, H.; Leisola, M. Phytase Production by High Cell Density Culture of Recombinant Bacillus subtilis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2001, 23, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Zhai, L.; Tian, Q.; Meng, D.; Guan, Z.; Cai, Y.; Liao, X. Identification of a Novel Glycerophosphodiester Phosphodiesterase from Bacillus altitudinis W3 and Its Application in Degradation of Diphenyl Phosphate. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohshima, N.; Yamashita, S.; Takahashi, N.; Kuroishi, C.; Shiro, Y.; Takio, K. Escherichia coli Cytosolic Glycerophosphodiester Phosphodiesterase (UgpQ) Requires Mg2+, Co2+, or Mn2+ for Its Enzyme Activity. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, P.; Giri, J. Rice and Chickpea GDPDs Are Preferentially Influenced by Low Phosphate and CaGDPD1 Encodes an Active Glycerophosphodiester Phosphodiesterase Enzyme. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 1699–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.T.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Tran, A.-T.; Tran, T.T.T.; Tran, T.-A.; Vo, K.T.X.; Jeon, J.-S.; Van Vu, T.; Kim, J.-Y.; Nguyen, N.P.; et al. A Novel Glycerophosphodiester Phosphodiesterase 13 Is Involved in the Phosphate Starvation-Induced Phospholipid Degradation in Rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. PPB 2025, 228, 110230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.