Abstract

Fomites are common vehicles for viral transmission. Most studies on virus disinfection have focused on non-porous, hard surfaces, with few investigating porous materials. This review addresses two research questions: (1) What affects viral viability on reusable porous materials? (2) Which antimicrobials effectively target viruses on these materials? Among existing studies, viral persistence on reusable porous surfaces was influenced by several factors, including viral envelope status, virus subtype, material type and structure, temperature, relative humidity, deposition method, and transmission medium. Disinfectants evaluated included ultraviolet irradiation, steam, chlorine, quaternary ammonium compounds, alcohols, glutaraldehyde, silver, and peroxide-based agents. Chlorine and steam were most effective; glutaraldehyde and peroxides showed limited action against non-enveloped viruses. Viral persistence and disinfection efficacy on reusable porous materials are influenced by multiple factors, highlighting the need for robust environmental management and infection control practices. Lack of standard tests and long-term disinfection effects on material integrity remain key challenges needing further study.

1. Introduction

Viruses are a common source of acute infections worldwide [1,2]. Many are transmitted person-to-person through direct or indirect contact. In direct contact transmission, pathogens are transmitted from an infected individual to a susceptible host, whereas indirect contact transmission occurs via a contaminated intermediary (e.g., hands or environmental surfaces). Indirect contact transmission can persist for days or even weeks, depending on the virus and environmental conditions [3,4,5,6]. Consequently, some viruses are difficult to control because of their ability to remain viable on surfaces and spread efficiently through fomite-to-person transmission [2,7,8].

In public spaces (e.g., restaurants and transportation systems), materials are constructed of both non-porous materials (e.g., stainless steel benches, glass, and plastics) and porous materials (e.g., brick, wood, and textiles) [9]. The diverse characteristics of these materials present efficacy challenges when treated with an antimicrobial [10,11,12]. In contrast to non-porous materials, porous materials tend to retain pathogens because their absorbent structure can trap fluids and small particles, shielding microorganisms from antimicrobial action [12,13,14]. The current understanding regarding the persistence of viruses on porous materials is limited, with only one systematic review focused on enteric viruses on soft materials [7]. Moreover, as some porous materials, including paper, are disposable, disinfection of viruses is typically needed on reusable materials. Hence, a comprehensive review to examine the factors influencing the persistence of animal and human viruses on reusable porous materials is needed.

The risk of spreading viruses can be significantly reduced by proper implementation of infection control practices, such as handwashing, use of personal protective equipment, environmental cleaning, and appropriate handling of textiles and laundry [15,16]. Environmental sanitation—practices aimed at reducing pathogen presence on surfaces—is essential for effective infection control [17]. Implementing these practices requires knowledge of virus persistence and the efficacy of antimicrobial agents [17]. In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) oversees the regulation of chemical sanitizers and disinfectants applied to soft porous materials (Table 1), and enforces a standard efficacy testing requirement, which requires achieving a reduction of ≥3-log and ≥6-log of the target virus and bacteria, respectively [18]. It should be noted that the EPA does not set a specific standard for disinfecting viruses on porous materials; instead, it evaluates such cases individually. Moreover, disinfectant efficacy claims for soft, porous surfaces typically do not guarantee complete virus inactivation. Considering various studies that have explored virus disinfection on porous materials, there is a need for a comprehensive review that aims to summarize information about the effectiveness of various virus disinfection approaches on porous materials.

Table 1.

Major testing standards recommended by the U.S. EPA for registration of sanitizers and disinfectants for use on porous materials [19].

In brief, this review is guided by the following two research questions: (1) What factors affect the persistence of human and animal viruses on reusable porous materials? (2) How effective are current disinfection approaches in reducing viral load on reusable porous surfaces? Particularly, this literature review will identify the gaps that exist in the current literature regarding virus persistence and disinfection on reusable porous materials.

2. Persistence of Viruses on Porous Materials

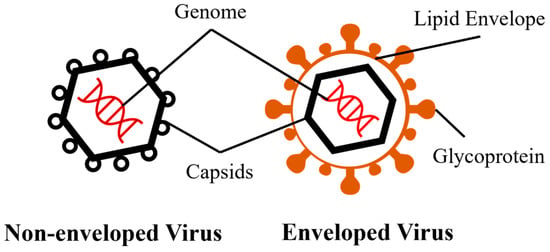

The presence of a viral envelope was significantly associated with virus persistence. Other factors, including material characteristics, temperature, relative humidity (RH), transmission medium, deposition method, and viral strain or subtype, also influence virus viability (Table 2). Generally, non-enveloped viruses persist longer on porous materials than do enveloped viruses due to the structural difference (Figure 1). Specifically, non-enveloped viruses can remain infectious for periods ranging from one day to up to 15 days at room temperature, while most enveloped viruses typically persist less than 1–2 days. This phenomenon could be attributed to the inherent susceptibility of the envelope, which is composed of a monolayer of phospholipids [28]. The viability of the virus can be compromised due to the impact of dehydration, surfactants, heat, and so on, on the phospholipid envelope [29,30,31]. One exception is enveloped influenza A virus H5N1, which has shown remarkable persistence and can remain infectious for up to 17 to 44.7 days on feathers at room temperature [32]. The increased viability was attributed to the presence of preen oil on feathers, which aggregated viruses and provided protective effects. However, the study did not specify the effect of two critical factors: relative humidity (RH) and the transmission medium of the virus. Additionally, the study lacked a comprehensive description of the potential protective mechanism provided by the feathers, hence impeding the ability to compare this finding with other studies on virus persistence.

Table 2.

Persistence of viruses on porous materials.

Figure 1.

Basic structures of non-enveloped and enveloped viruses.

2.1. The Effect of Material Characteristics

Characteristics of inanimate materials, also critical in virus persistence, are typically categorized as: the material and the structural construction [71]. While many studies have investigated the effect of materials on virus persistence [38,45,53,68], the impact of material construction, often recognized as material roughness, topography, or porosity, has remained understudied. Furthermore, materials can also be categorized based on their launderability. However, this classification is linked to disinfection procedures and may not be correlated to the persistence of viruses. Nevertheless, we still presented virus persistence data on launderable materials, because these data can potentially serve as a guide in the development of effective disinfection strategies.

Given that the presence of a viral envelope has a significant impact on virus persistence, the effects of material characteristics were examined separately for enveloped and non-enveloped viruses. Several studies reported persistence of non-enveloped viruses was greater on porous materials than on non-porous materials. For example, feline calicivirus (FCV), murine norovirus (MNV), and poliovirus (PV) persisted longer on porous materials, such as carpet, cotton, and wood, compared to non-porous materials, such as stainless steel [39,41]. However, non-enveloped bacteriophage MS2, a bacteriophage, was less persistent on polyester tablecloths than on plastics at room temperature [35].

Many enveloped viruses are less persistent on porous materials than on non-porous materials. For example, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 persist for shorter periods on cotton cloth and wood, compared to non-porous materials (e.g., stainless steel, glass and plastics) [60,61,63]. In contrast, influenza A virus and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus were more persistent on feathers, wood, and cloth than on stainless steel [45,59]. Material type can also significantly affect the virus persistence on porous materials. For example, avian metapneumovirus, cytomegalovirus, equine herpesvirus, and SARS-CoV were more persistent on cotton cloth than on wood, whereas vaccinia virus persisted longer on cotton than wool [69]. Avian metapneumovirus, Ebola virus, influenza A virus, and SARS-CoV were more persistent on more hydrophobic materials such as feathers, polypropylene gowns, and polyester fabrics [45,50,54]. Zuo et al. [54] investigated the effect of material hydrophobicity on the persistence of influenza A virus H9N9 and concluded that the hydrophobicity of the material significantly influenced virus persistence more than the types of specific materials used. One possible explanation is that the increased hydrophobicity of materials promotes virus aggregation, which provides protection to the enclosed viruses against environmental stressors [72]. In contrast, human coronavirus OC43, influenza A virus, and SARS-CoV-2 showed the opposite pattern in persistence [45,48,51,63,70], which the phenomenon is still under investigation.

The persistence of viruses is also significantly affected by the construction of materials. For example, PV was more persistent on wool blanket than on wool gabardine materials at room temperature in both 35% and 78% RH [42]. Furthermore, bacteriophage Phi6 persisted longer on looped carpet than on cut carpet [36]. These studies suggested that the construction of soft, porous materials could provide protection for viruses from desiccation. This protection might be attributed to mechanisms such as a decreased material area or the potential for viruses being absorbed into the porous texture of soft materials [36,73]. However, the material construction (looped or cut carpet) did not significantly affect the persistence of bacteriophage MS2 at room temperature in relative humidity (RH) between 30 and 40% [36], suggesting that highly hydrophobic bacteriophage MS2 could be less susceptible to desiccation on porous materials [71,74].

2.2. The Effect of Temperature and Relative Humidity

Apart from material characteristics, the persistence of viruses is notably affected by temperature and RH of the environment. The effect of temperature (4 °C vs. room temperature) was evaluated for 11 viruses, and all were found to persist longer at the lower temperature, regardless of whether they were enveloped (Table 2). At lower temperatures, the chemical and biological activities are decreased to maintain the structural integrity of viruses, hence protecting the viability of viruses [7]. This may also explain the seasonal trends in outbreaks associated with airborne, waterborne, and foodborne viruses. Though 4 °C or lower temperatures are typically used for preservation of most microorganisms, 20–25 °C is more commonly found in indoor environments and in public spaces due to indoor environmental standards and regulations [75]. Thus, studying the persistence of viruses at ambient temperatures is important to understand the transmission dynamics and develop preventive strategies.

RH also plays a key role in the occurrence of viral outbreaks [76,77]. In general, higher RH reduced the persistence of both non-enveloped and enveloped viruses, though exceptions were noted (Table 2). For example, poliovirus (PV) persisted longer at 35% RH than at 78% RH on wool, but the opposite trend was observed on cellulose filter membranes [37,42]. In contrast, the persistence of some viruses—including adenovirus, hepatitis A virus, PV, and rotavirus—was not significantly influenced by RH when tested on cotton [33,42]. Overall, our review indicates that most viruses tend to exhibit extended persistence times on porous materials under low RH conditions. At high RH, the increased water activity enhances chemical reactions, such as the Maillard reaction and oxidation, which contribute to the inactivation of viruses exposed to air [30]. The increased reactions are likely due to the increased rate of diffusion of reactants [30]. Additionally, viral envelopes, composed primarily of phospholipids, are more susceptible to oxidation than spike proteins [30]. Consequently, the influence of RH is greater for enveloped viruses than for some non-enveloped viruses, such as PV, rotavirus, hepatitis A virus, and adenovirus.

2.3. The Effect of Transmission Medium, Deposition Method, Strain Subtype and pH

Besides the presence of an envelope, virus persistence can also be affected by the contamination process. Several studies investigated the virus persistence under simulated contamination. For example, in some studies the authors used transmission media with a comparable composition to human body fluids (e.g., organic matter, fecal material, or artificial saliva) to suspend virus particles [46,69]. In addition, several studies used different inoculation techniques to mimic virus deposition process on inanimate materials, such as spiking, spraying, or the controlled release of virus-laden dust particles. The impact of transmission medium, deposition method, strain subtype, and pH has been studied only for a few viruses. The effects of transmission medium were evaluated on the persistence of five non-enveloped viruses, while bacteriophage Phi6 was the only enveloped virus studied in relation to the organic composition in transmission medium (Table 2). Savage et al. [34] revealed the different effects of transmission medium between two subtypes of avian reovirus. Specifically, 20% fecal matter did not affect the viability of avian reovirus R2 on cotton, whereas it provided protection for avian reovirus S1133. It was observed that the presence of fecal material reduced the viability of adenovirus and PV [33]. However, specific soil loads, such as tripart soil load and artificial saliva, decreased the reduction rates of bacteriophage Phi6 on wood from 1.98 to 0.08 and 1.30 log plaque forming unit (PFU)/h, respectively [46]. For bacteriophage Phi6, the protective effect conferred by organic matter may act as antioxidants or enhance viscosity, hence impeding direct interaction between viruses and the atmospheric oxygen [30,78,79]. However, organic matters such as fecal constituents may compete with the virus for adsorption sites, resulting in a shorter persistence period for AV and PV on cotton [33]. Moreover, recovery efficiency from porous material, which was rarely reported in persistence studies, could also be reduced by the presence of organic matter [80]. This phenomenon could underestimate the persistence of viruses on porous materials. Consistent with a previous review, the effect of organic matter on the persistence of viruses among different materials was not conclusive [7].

The deposition of virus particles is another factor in determining the persistence of viruses on porous materials. The deposition method had an impact on the persistence of influenza A virus, which showed longer viability when the 20 µL virus was spiked onto materials in one drop compared to being dispersed by aerosol [54]. There is a higher persistence rate when viruses are inoculated in liquid droplets compared to aerosols. This is primarily attributed to the smaller area occupied by liquid droplets on the surface, which makes them less susceptible to desiccation, thereby enhancing viral stability [80,81]. Additionally, due to the hydrophobic nature of the virus envelope or capsid, the larger areas of the air-water interface of aerosols may facilitate the gathering of virus particles on the interface, leading to an increased exposure to air and susceptibility to oxidation-induced damage [82].

RH may interact with the deposition method and result in different virus persistence. In 35% RH, Vaccinia virus exhibited longer persistence through virus-containing dust contact, whereas in 78% RH, the persistence was longer in droplets [69]. The effect of pH was only investigated by one study, which reported increased sensitivity to lower pH levels (<3) on cotton sheet and carpet (material unknown) for FCV [38]. Furthermore, the persistence is also different for different strains, as influenza A virus H9N2 was found to be more persistent than influenza A virus H6N2 on pine wood [55].

3. Disinfection of Viruses on Porous Materials

The disinfection efficacy has been studied for all non-enveloped viruses for which persistence has been reported on porous materials, except for avian reovirus (Table 3). Disinfection can be accomplished by either a laundry procedure or a non-laundry procedure, depending on the type of porous material. Specifically, the disinfection of adenovirus, bacteriophage MS2, hepatitis A virus, MNV, and PV was investigated by laundering cotton fabrics, while bacteriophage MS2, coxsackievirus, echovirus, FCV, foot-and-mouth disease virus and poliovirus were studied on non-launderable materials, including porous unglazed red clay, carpet, wood and cellulose membrane (Table 3). Among enveloped viruses, only bacteriophage Phi6, Ebola virus, and SARS-CoV-2 have been investigated regarding their persistence and disinfection on porous materials, but Vaccinia virus was only investigated for its persistence (Table 3). In addition, African swine fever virus and murine hepatitis virus have primarily been studied in terms of disinfection on concrete and bus seat fabric, respectively, but with limited data on their persistence.

Table 3.

Disinfection of viruses on porous materials.

Disinfection can be achieved by chemical disinfectant agents and physical treatments. EPA primarily focuses on regulating chemical disinfectants and enforces strict requirements for standardized efficacy testing [19]. Additionally, EPA or ASTM provides comprehensive guidelines for standardized testing methods tailored to specific disinfection procedures and the materials they target (Table 1). For porous materials, disinfection procedures can be classified into two major categories: laundry and non-launderable material disinfectants, according to the guidelines. It is important to acknowledge that many porous materials are not suitable for laundering. Additionally, disinfectants used in both laundry and non-laundry processes are subject to different standards and testing methods according to the EPA and ASTM [19]. Consequently, this review presented a clear distinction between disinfectants suitable for launderable materials and those designed for non-launderable materials, with our focus on the latter.

3.1. Launderable Materials

In general, laundry disinfection is composed of two steps: a water rinse cycle and a hot air-drying cycle. EPA stipulated that disinfectants intended for laundry use must successfully undergo a standard suspension test, i.e., AOAC use-dilution methods (Table 1). This is due to the ability of water to remove viruses from the fabric and hold them in suspension during the entire laundry process. Consequently, a significant level of virus inactivation occurs through contact with disinfectants in the suspension rather than on the fabrics [83,102]. The removal of viruses by water and detergents from fabrics is a crucial step in the laundry process. During the water rinse step, the efficacy of virus disinfection can be affected by the water temperature and the addition of disinfectant. Hot water wash (54–60 °C) can more effectively inactivate PV on cotton, wool, and nylon than warm (38–43 °C) and cold (21–27 °C) water [92].

Surfactants in detergents can cause damage to viral envelopes composed of phospholipids [103]. Furthermore, it was also reported that the addition of sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) in the wash cycle reduced the adenovirus, hepatitis A virus, and rotaviruses by >4 logs after the final rinse [102]. SARS-CoV-2 can also be effectively reduced by adding 0.07% NaClO during the laundry water rinse step [98]. However, the reduction in SARS-CoV-2 by 70% alcohol and Lysoform® (unknown product) was less during laundry [98]. NaClO (commonly known as bleach) was the only disinfectant extensively explored for laundry disinfection. While high water temperatures can contribute to virus inactivation during the laundry process, the addition of bleach can significantly enhance the inactivation of viruses [93]. However, sodium hypochlorite is a strong oxidizer that has the potential to damage fabrics and bleach clothing [104]. Therefore, there is a need for the development of alternative disinfectants to bleach to achieve effective virus inactivation and mitigate clothing damage in the laundry process.

Interestingly, the hot air-drying cycle for 28 min after a detergent wash cycle only reduced a maximum of 0.19 log PFU per 58 cm2 area for these three viruses, which is considered ineffective according to the EPA regulations (≥3 logs) [83].

3.2. Non-Launderable Materials

Chemical disinfectants are essential tools for effectively disinfecting non-launderable materials. The EPA oversees the regulation of disinfectants in the US, which includes a variety of active ingredients and formulations specifically designed for non-porous materials. However, only a limited subset of the available products has been tested on porous materials [87,88]. According to the EPA, there is a lack of a standardized testing method for non-launderable soft porous materials [19]. The lack of a standard testing method can be linked to challenges in recovering viruses from non-launderable porous materials [39,91]. Moreover, the efficacy of disinfectants against viruses can be significantly influenced by the characteristics of porous materials [87,88]. This further complicates the establishment of a universal standard testing method that accurately measures the efficacy of disinfectants on specific types of porous materials. In our review, an evaluation was conducted on various active ingredients, including chlorine, quaternary ammonium chemicals (QACs), alcohols, glutaraldehyde, silver, and peroxides, to assess their effectiveness against some viruses on non-launderable porous materials, with each having limitations.

The effectiveness of NaClO or other chlorine-based disinfectants was extensively reported against both non-enveloped and enveloped viruses on non-launderable materials. For example, 1.4–1.5% NaClO was able to effectively reduce >3 logs of Ebola virus in 10 min when applied to pilot seat-belt strapping [95]. A NaClO solution at 0.5% or 5000 ppm, a commonly used concentration, effectively reduced 3.92 logs of bacteriophage MS2 on wood and >3 logs of FCV and MNV on cotton fabrics in 5 min [89]. Furthermore, the chlorine solution with 0.1–0.5% NaClO inactivated >4 logs of SARS-CoV-2 in 0.5 min on wood [84]. Similarly, a solution containing 0.5% NaClO resulted in a reduction in bacteriophage Phi6 by 2.98 and 6.83 logs on wood and concrete materials, respectively, within 1 min at a temperature of 25 °C and RH of 23% [94]. At increased RH (85%), the reduction in bacteriophage Phi6 was similar on wood but decreased to 4.32 logs on concrete materials within 1 min [94]. A lower concentration of NaClO solution at 1076 ppm was also effective against bacteriophage MS2 on the polyester carpet [36]. At 500 ppm, NaClO was effective against Echovirus 25 on cellulose membrane, but not effective against Echovirus 6 [37]. For murine hepatitis virus, applying detergent or chlorine-based disinfectants on contaminated seat fabric followed by immediate wiping was found ineffective [96]. Other than NaClO, PurTabs®, which can also produce hypochlorous acid as the active ingredient, resulted in a reduction of over 3 logs of bacteriophage Phi6 within 1 min when applied to polyester carpet [36]. In summary, chlorine-based disinfectants are highly effective against Echovirus, FCV, MNV, PV, bacteriophage Phi6 and murine hepatitis virus, but they can damage materials when used at high concentrations (e.g., 5500 ppm) or after prolonged use due to the strong oxidizing properties [104,105].

Besides chlorine-based disinfectants, 2.6% glutaraldehyde has been proven effective (>3 log reduction) in 1 min against FCV on carpets made from olefin, polyester, and nylon, as well as fabrics made from cotton, polyester, and cotton mix [87]. Additionally, silver dihydrogen citrate (0.003% silver ion) was also effective against FCV with a 3.62 log-reduction on nylon carpets in 60 min [88]. However, it demonstrated limited efficacy (<3 log reduction) on blended carpet made from unspecified materials after 10 min of contact time [87]. Moreover, 0.05% glutaraldehyde with a 60 min contact time did not exhibit strong efficacy against coxsackievirus, echoviruses, and PV on cellulose membranes [37]. The efficacy of glutaraldehyde and silver in virus disinfection on specific materials such as cellulose membrane, nylon carpet, and olefin carpet has been demonstrated [37,87,88]. Nonetheless, exposure to glutaraldehyde can potentially pose human health risks [106]. Additionally, the use of silver dihydrogen citrate has been found to cause the formation of a sticky film on carpets [88].

Peroxide-based disinfectants have shown effectiveness against both non-enveloped and enveloped viruses, demonstrating their potential as broad-spectrum antiviral agents. Specifically, disinfectants utilizing H2O2 as the active ingredient were effective against FCV on cotton fabric in 5 min and murine hepatitis virus on seat fabric in 30 s [89,97]. The effectiveness of ozone at concentrations of 20–25 ppm for 20 min was shown against FCV on fabric, cotton, and carpet in office environments [95,97]. Peroxides, including peracetic acid and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), can denature viral capsid proteins, but only limited data on porous materials are available [89,90,97,107].

QACs and alcohols are less likely to cause material damage; however, they demonstrated weak activity against non-enveloped viruses [87,108]. For example, chlorophenol/phenylphenol-based, quaternary ammonium compound (QAC)-based, and alcohol-based disinfectants were not effective against FCV on either fabric or carpets [87]. Despite the limited efficacy against non-enveloped viruses, two QAC-based disinfectants, Ardrox 6092 and Desintex, achieved >3-log reduction in efficacy against Ebola virus in 10 min on pilot seat-belt strapping, while another QAC-based disinfectant presented efficacy against murine hepatitis virus [95,97]. Interestingly, the efficacy of disinfection may also be affected by the method used to dispense the disinfectant, as one study reported that the use of an electrostatic sprayer decreased the disinfection efficacy of Vital Oxide (0.2% chlorine dioxide) against murine hepatitis virus compared to a trigger-pull sprayer [97]. The observed reduction in efficacy in electrostatic spray was likely attributed to gaps among evenly distributed disinfectant droplets and a reduced amount of free radicals produced by active ingredients between the charged droplets [97]. Other than the aforementioned chemical disinfectants, the disinfectant Virkon, which contains potassium peroxymonosulfate as an active ingredient, was found to be effective against African swine fever virus when used at concentrations greater than 2%, resulting in a reduction of over 2.2 logs on concrete materials after a 5 min contact time [91].

In addition to chemical disinfectants, the CDC also recommends using steam cleaning to address carpet contamination after a human norovirus outbreak [109]. However, the CDC has not published any specific protocols in compliance with this guidance. One report has provided evidence that steam cleaning was able to reduce bacteriophage MS2 by 6 logs on unglazed clay in 5 s and polyester carpet with a 60 s treatment, and the sensitivity to heat and humidity of bacteriophage MS2 can be further increased by using cell culture medium as the transmission medium, likely due to medium-induced alterations of its surface hydrophobicity [74,85]. Additionally, it has been found to be effective against FCV on nylon and wool carpets in 90 s, and bacteriophage Phi6 on polyester carpet in 60 s [36,88]. These results are probably attributed to the rapid denaturation of viral proteins in the outer structures due to heat [36,85,88]. However, the potential effect of various external factors, such as material construction, steam temperature, and heat distribution on materials, on the effectiveness of steam vapor has not been comprehensively examined.

Ultraviolet (UV) light is another physical disinfection method that can be performed without direct contact with fomites. UV radiation at 100 mJ/cm2 for 70 s reduced bacteriophage MS2 by 1.27–1.58 logs on the front sections and −0.07 to 1.36 logs on the side sections of a cotton T-shirt [85]. Furthermore, UV-C treatment (396 mJ/cm2) showed efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 only on fabrics of bus seats and clothing in 28 min and 22 s, respectively [99]. UV-C has been found effective in eliminating bacteria on hard porous materials [110], though one study reported its failure to disinfect bacteriophage MS2 on T-shirts [86]. This may be attributed to the inherent resistance of viruses to UV-C and the challenges associated with the effective penetration of UV-C into fabric materials [86].

The combination of physical and chemical disinfectants was only investigated in one study, which demonstrated that heat treatment combined with ozone (800 ppm) for a duration of 10 min was effective against SARS-CoV-2 on cotton fabric [100].

4. Conclusions

Our review indicates that virus persistence on porous materials is strongly influenced by virus type, material composition and construction, temperature, relative humidity, and deposition method. Enveloped viruses generally exhibit lower persistence than non-enveloped viruses, though exceptions exist. Lower temperatures, lower relative humidity, and liquid droplet deposition tend to promote longer persistence. The complex interplay among these factors underscores the need for careful monitoring of environmental and material parameters, as well as standardized testing when evaluating virus persistence. Among the various disinfection methods reviewed, chlorine-based agents and steam were identified as the most effective against a wide range of viruses on porous materials. In contrast, alternatives such as glutaraldehyde and peroxide-based disinfectants showed limited or inconsistent efficacy, particularly against non-enveloped viruses. However, standardized protocols for assessing disinfectant performance on non-launderable porous materials are lacking, and data on the long-term effects of repeated disinfection on material integrity remain scarce. Further research is needed to validate virus recovery methods and to confirm the effectiveness of disinfectants across different porous materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.J.; Methodology, J.H. and B.K.; Data Curation, J.H., B.K. and X.J.; Formal Analysis, J.H., B.K. and X.J.; Investigation, J.H. and B.K.; Resources, A.M.F. and X.J.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.H.; Writing—Review & Editing, B.K., R.Y., A.M.F. and X.J.; Visualization, X.J.; Supervision, X.J.; Project Administration, X.J.; Funding Acquisition, A.M.F. and X.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by grants from the USDA-NIFA grant number 2020-67017-32427 and the AHRQ, grant number 1R01HS025987-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciated Geun Woo Park and Jan Vinjé (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, GA, USA) for their expert guidance and constructive comments in preparation of this manuscript. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the United States Department of Agriculture-National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA) and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| T | Temperature |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| MC | Material characteristics |

| TM | Transmission media |

| FCV | Feline calicivirus |

| MNV | Murine norovirus |

| PV | Poliovirus |

| SARS-CoV | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus |

| NaClO | Sodium hypochlorite |

| QAC | Quaternary ammonium compound |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Li, X.C.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Liu, J.S.; Ran, J.J.; Han, L.F.; Zhang, X.X. Global burden of viral infectious diseases of poverty based on Global Burden of Diseases Study 2021. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2024, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.T.; Ren, J.J.; Li, R.H.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H.Y.; Li, J.M.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, X.C.; Wang, G. Global burden of upper respiratory infections in 204 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2019. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 37, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheesbrough, J.S.; Green, J.; Gallimore, C.I.; Wright, P.A.; Brown, D.W. Widespread environmental contamination with Norwalk-like viruses (NLV) detected in a prolonged hotel outbreak of gastroenteritis. Epidemiol. Infect. 2000, 125, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, N.H.L. Transmissibility and transmission of respiratory viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 528–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morter, S.; Bennet, G.; Fish, J.; Richards, J.; Allen, D.J.; Nawaz, S.; Iturriza-Gomara, M.; Brolly, S.; Gray, J. Norovirus in the hospital setting: Virus introduction and spread within the hospital environment. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 77, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.M.; Fornek, M.; Schwab, K.J.; Chapin, A.R.; Gibson, K.; Schwab, E.; Spencer, C.; Henning, K. A norovirus outbreak at a long-term-care facility: The role of environmental surface contamination. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2005, 26, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeargin, T.; Buckley, D.; Fraser, A.; Jiang, X.P. The survival and inactivation of enteric viruses on soft surfaces: A systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, E.M.; Minter, A.; Edmunds, W.J.; Lau, C.L.; Kucharski, A.J.; Lowe, R. Transmission modelling of environmentally persistent zoonotic diseases: A systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, E466–E478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernon-Kenny, L.A.; Behringer, D.L.; Crenshaw, M.D. Comparison of latex body paint with wetted gauze wipes for sampling the chemical warfare agents VX and sulfur mustard from common indoor surfaces. Forensic Sci. Int. 2016, 262, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszewska, E.; Czupryna, P.; Pancewicz, S.; Martonik, D.; Buklaha, A.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A. Is peracetic acid fumigation effective in public transportation? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, J.D.; Wilson, A.M.; Sassi, H.P.; Reynolds, K.A. Tracking and controlling soft surface contamination in health care settings. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdier, T.; Coutand, M.; Bertron, A.; Rogues, C. A review of indoor microbial growth across building materials and sampling and analysis methods. Build. Environ. 2014, 80, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fraser, A.; Jiang, X. Efficacy of three EPA-registered antimicrobials and steam against two human norovirus surrogates on nylon carpets with two backing types. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0038424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Fraser, A.; Jiang, X. Efficacy of three chemical disinfectants and steam against Clostridioides difficile endospores on nylon carpet with two different backing systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e0086125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittet, D. Improving adherence to hand hygiene practice: A multidisciplinary approach. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001, 7, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.A.; Verhougstraete, M.P.; Mena, K.D.; Sattar, S.A.; Scott, E.A.; Gerba, C.P. Quantifying pathogen infection risks from household laundry practices. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, M.R.; Johnson, B.E.E.; Leong, B.M.E.; Fraser, A.M. Review of state regulations related to environmental sanitation in long-term care facilities. Am. J. Infect. Control 2025, 53, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency. OCSPP 810.2200 Disinfectants for Use on Environmental Surfaces, Guidance for Efficacy Testing; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency. OCSPP 810.2400—Disinfectants and Sanitizers for Use on Fabrics and Textiles; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC 955.14 Testing disinfectants against Salmonella enterica. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL, 22nd ed.; AOAC Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023.

- AOAC 955.15 Testing disinfectants against Staphylococcus aureus. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL, 22nd ed.; AOAC Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023.

- AOAC 964.02 Testing disinfectants against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL, 22nd ed.; AOAC Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023.

- ASTM E1153-22; Standard Test Method for Efficacy of Sanitizers Recommended for Inanimate, Hard, Nonporous Non-Food Contact Surfaces. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- ASTM E2274-24; Standard Test Method for Evaluation of Laundry Sanitizers and Disinfectants. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM E2406-24; Standard Test Method for Evaluation of Laundry Sanitizers and Disinfectants for Use in High Efficiency Washing Operations. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA.

- AATCC TM100-2004; Antibacterial Finishes on Textile Materials. AATCC: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2004.

- ASTM E2149-25; Standard Test Method for Determining the Antimicrobial Activity of Antimicrobial Agents Under Dynamic Contact Conditions. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- Ivanova, P.T.; Myers, D.S.; Milne, S.B.; McClaren, J.L.; Thomas, P.G.; Brown, H.A. Lipid composition of the viral envelope of three strains of influenza virus-Not all viruses are created equal. Acs Infect. Dis. 2015, 1, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfiky, A.A.; Ibrahim, I.M. Zika virus envelope—Heat shock protein A5 (GRP78) binding site prediction. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 5248–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.S. Roles of water-molecules in bacteria and viruses. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 1993, 23, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Veit, M.; Osterrieder, K.; Gradzielski, M. Surfactants—Compounds for inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 and other enveloped viruses. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 55, 101479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunakaran, A.C.; Murugkar, H.V.; Kumar, M.; Nagarajan, S.; Tosh, C.; Pathak, A.; Rajendrakumar, A.M.; Agarwal, R.K. Survivability of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1) in naturally preened duck feathers at different temperatures. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abad, F.X.; Pinto, R.M.; Bosch, A. Survival of enteric viruses on environmental fomites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 3704–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, C.E.; Jones, R.C. The survival of avian reoviruses on materials associated with the poultry house environment. Avian Pathol. 2003, 32, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beiza, A.A.; Mohammad, Z.H.; Sirsat, S.A. Persistence of foodborne pathogens on farmers’ market fomites. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, N.; Renninger, N.; Bope, A.; Cochran, S.J.; Greaves, J.; Haines, S.R.; Balasubrahmaniam, N.; Stuart, K.; Panescu, J.; Bibby, K.; et al. Persistence of viable MS2 and Phi6 bacteriophages on carpet and dust. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e12969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moce-Llivina, L.; Papageorgiou, G.T.; Jofre, J. A membrane-based quantitative carrier test to assess the virucidal activity of disinfectants and persistence of viruses on porous fomites. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 135, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makison Booth, C.; Frost, G. Survival of a norovirus surrogate on surfaces in synthetic gastric fluid. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 86, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, D.; Fraser, A.; Huang, G.; Jiang, X. Recovery optimization and survival of the human norovirus surrogates feline calicivirus and murine norovirus on carpet. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01336-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.N.; Park, S.Y.; Bae, S.C.; Oh, M.H.; Ha, S.D. Survival of norovirus surrogate on various food-contact surfaces. Food and Environ. Virol. 2014, 6, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrakar, S.B.; Henley, J.; Gurian, P.L.; Gerba, C.P.; Mitchell, J.; Enger, K.; Rose, J.B. Persistence analysis of poliovirus on three different types of fomites. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 122, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, G.J.; Sidwell, R.W.; Mcneil, E. Quantitative studies on fabrics as disseminators of viruses. II. Persistence of poliomyelitis virus on cotton and wool fabrics. Appl. Microbiol. 1966, 14, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattar, S.A.; Lloyd-Evans, N.; Springthorpe, V.S.; Nair, R.C. Institutional outbreaks of rotavirus diarrhoea: Potential role of fomites and environmental surfaces as vehicles for virus transmission. Epidemiol. Infect. 1986, 96, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijan, S.; Steyer, A.; Poljsak-Prijatelj, M.; Cencic, A.; Ostar-Turk, S.; Koren, S. Rotaviral RNA found on various surfaces in a hospital laundry. J. Virol. Methods 2008, 148, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Patnayak, D.P.; Chander, Y.; Parsad, M.; Goyal, S.M. Survival of two avian respiratory viruses on porous and nonporous surfaces. Avian Dis. 2006, 50, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.A.; Gutierrez, A.; Gibson, K.E. Factors impacting persistence of Phi6 bacteriophage, an enveloped virus surrogate, on fomite surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e02552-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, C.; Mu, Y.; Houston, H.; Martinez-Smith, M.; Noble-Wang, J.; Coulliette-Salmond, A.; Rosea, L. Persistence of bacteriophage Phi 6 on porous and nonporous surfaces and the potential for its use as an Ebola virus or coronavirus surrogate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e01482-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowell, J.D.; Forlin-Passoni, D.; Din, E.; Radford, K.; Brown, D.; White, A.; Bate, S.L.; Dollard, S.C.; Bialek, S.R.; Cannon, M.J.; et al. Cytomegalovirus survival on common environmental surfaces: Opportunities for viral transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 205, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faix, R. Survival of cytomegalovirus (CMV) on environmental surfaces. Pediatr. Res. 1984, 18, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.W.; Cutts, T.A.; Nikiforuk, A.M.; Poliquin, P.G.; Court, D.A.; Strong, J.E.; Theriault, S.S. Evaluating environmental persistence and disinfection of the Ebola virus Makona variant. Viruses 2015, 7, 1975–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saklou, N.T.; Burgess, B.A.; Ashton, L.V.; Morley, P.S.; Goehring, L.S. Environmental persistence of equid herpesvirus type-1. Equine Vet. J. 2021, 53, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.; Derby, C.; Virjee, N.; Hardwick, M. Virus inactivation on common indoor contact fabrics. Indoor Built Environ. 2022, 31, 1381–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, J.; Berezin, E.N.; Courvalin, P.; Dwyer, D.E.; Exner, M.; Jana, L.A.; Kaku, M.; Lee, C.; Letlape, K.; Low, D.E.; et al. The survival of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus on 4 household surfaces. Am. J. Infect. Control 2014, 42, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.L.; de Abin, M.; Chander, Y.; Kuehn, T.H.; Goyal, S.M.; Pui, D.Y.H. Comparison of spike and aerosol challenge tests for the recovery of viable influenza virus from non-woven fabrics. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2013, 7, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Chan, M.; VanderZaag, A. Inactivation of avian influenza viruses on porous and non-porous surfaces is enhanced by elevating absolute humidity. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greatorex, J.S.; Digard, P.; Curran, M.D.; Moynihan, R.; Wensley, H.; Wreghitt, T.; Varsani, H.; Garcia, F.; Enstone, J.; Nguyen-Van-Tam, J.S. Survival of influenza A(H1N1) on materials found in households: Implications for infection control. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.V.; Cohen, B.; Bovino, M.E.; Desai, S.; Whittier, S.; Larson, E.L. Survival of influenza virus on hands and fomites in community and laboratory settings. Am. J. Infect. Control 2012, 40, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.A.; Bennett, A.M. Persistence of influenza on surfaces. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017, 95, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Krishna, V.D.; Torremorell, M.; Goyal, S.M.; Cheeran, M.C.J. Stability of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus on fomite materials at different temperatures. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.B.; Douglas, R.G.; Geiman, J.M. Possible transmission by fomites of respiratory syncytial virus. J. Infect. Dis. 1980, 141, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.M.; Zhao, X.S.; Wen, R.F.; Huang, J.J.; Pi, G.H.; Zhang, S.X.; Han, J.; Bi, S.L.; Ruan, L.; Dong, X.P.; et al. Stability of SARS coronavirus in human specimens and environment and its sensitivity to heating and UV irradiation. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2003, 16, 246–255. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, M.Y.Y.; Cheng, P.K.C.; Lim, W.W.L. Survival of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, e67–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, A.W.H.; Chu, J.T.S.; Perera, M.R.A.; Hui, K.P.Y.; Yen, H.L.; Chan, M.C.W.; Peiris, M.; Poon, L.L.M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. Lancet Microbe 2020, 1, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, S.; Goldie, S.; Hill, A.; Eagles, D.; Drew, T.W. The effect of temperature on persistence of SARS-CoV-2 on common surfaces. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, T.; Kay, G.A.; Aljayyoussi, G.; Owen, S.I.; Harland, A.R.; Pierce, N.S.; Calder, J.D.F.; Fletcher, T.E.; Adams, E.R. SARS-CoV-2 viability on sports equipment is limited, and dependent on material composition. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasloff, S.B.; Leung, A.; Strong, J.E.; Funk, D.; Cutts, T. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 on critical personal protective equipment. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronca, S.E.; Sturdivant, R.X.; Barr, K.L.; Harris, D. SARS-CoV-2 viability on 16 common indoor surface finish materials. HERD 2021, 14, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidwell, R.W.; Dixon, G.J.; Mcneil, E. Quantitative studies on fabrics as disseminators of viruses: III. Persistence of vaccinia virus on fabrics impregnated with a virucidal agent. Appl. Microbiol. 1967, 15, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidwell, R.W.; Dixon, G.J.; Mcneil, E. Quantitative studies on fabrics as disseminators: I. Persistence of vaccinia virus on cotton and wool fabrics. Appl. Microbiol. 1966, 14, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.P.; Choi, Y.W.; Wendling, M.Q.; Rogers, J.V.; Chappie, D.J. Environmental persistence of vaccinia virus on materials. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 57, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, S.R.; Adams, R.I.; Boor, B.E.; Bruton, T.A.; Downey, J.; Ferro, A.R.; Gall, E.; Green, B.J.; Hegarty, B.; Horner, E.; et al. Ten questions concerning the implications of carpet on indoor chemistry and microbiology. Build. Environ. 2019, 170, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, S.; Spencer, A.; Garratt, I.; Thompson, K.A.; Dinesh, I.; Aranega-Bou, P.; Stevenson, D.; Clark, S.; Dunning, J.; Bennett, A.; et al. Persistence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus and viral RNA in relation to surface type and contamination concentration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e0052621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, K.E.; Crandall, P.G.; Ricke, S.C. Removal and Transfer of Viruses on Food Contact Surfaces by Cleaning Cloths. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 3037–3044, Erratum in Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e03373-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, P.A.; Farrah, S.R. Characterization of virus adsorption by using DEAE-sepharose and octyl-sepharose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 3965–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Indoor air quality in buildings: A comprehensive review on the factors influencing air pollution in residential and commercial structure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowen, A.C.; Steel, J. Roles of humidity and temperature in shaping influenza seasonality. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 7692–7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Goggins, W.B.; Chan, E.Y.Y. A time-series study of the association of rainfall, relative humidity and ambient temperature with hospitalizations for rotavirus and norovirus infection among children in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, D.L.; Smith, A.M. Antioxidants in soil organic matter and in associated plant materials. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 60, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidar, M.; Rozman, P.; Belko-Parkel, K.; Ravnik, M. Control of viscosity in biopharmaceutical protein formulations. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 2020, 580, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.; Shivkumar, M.; Cross, R.B.M.; Laird, K. Porous surfaces: Stability and recovery of coronaviruses. Interface Focus 2021, 12, 20210039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Marr, L.C. Mechanisms by which ambient humidity may affect viruses in aerosols. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 6781–6788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, L.M.; Jeon, S.; Rutala, W.A.; Weber, D.J.; Sobsey, M.D. Effects of air temperature and relative humidity on coronavirus survival on surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 2712–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerba, C.P.; Kennedy, D. Enteric virus survival during household laundering and impact of disinfection with sodium hypochlorite. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 4425–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- String, G.M.; White, M.R.; Gute, D.M.; Muhlberger, E.; Lantagne, D.S. Selection of a SARS-CoV-2 surrogate for use in surface disinfection efficacy studies with chlorine and antimicrobial surfaces. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, B.D. Reduction in infection risk through treatment of microbially contaminated surfaces with a novel, portable, saturated steam vapor disinfection system. Am. J. Infect. Control 2009, 37, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIsaac, S.A.; Mullin, T.J.; Munoz, S.; Ontiveros, C.C.; Gagnon, G.A. Immersive ultraviolet disinfection of E. coli and MS2 phage on woven cotton textiles. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, Y.S.; Allwood, P.B.; Hedberg, C.W.; Goyal, S.M. Disinfection of fabrics and carpets artificially contaminated with calicivirus: Relevance in institutional and healthcare centres. J. Hosp. Infect. 2006, 63, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, D.; Dharmasena, M.; Fraser, A.; Pettigrew, C.; Anderson, J.; Jiang, X. Efficacy of silver dihydrogen citrate and steam vapor against a human norovirus surrogate, feline calicivirus, in suspension, on glass, and on carpet. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00233-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeargin, T.; Fraser, A.; Huang, G.; Jiang, X. Recovery and disinfection of two human norovirus surrogates, feline calicivirus and murine norovirus, from hard nonporous and soft porous surfaces. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 1842–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.B.; Sharma, M.; Petric, M. Inactivation of norovirus by ozone gas in conditions relevant to healthcare. J. Hosp. Infect. 2007, 66, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbert, L.R.; Neilan, J.G.; Rasmussen, M. Recovery and chemical disinfection of foot-and-mouth disease and African swine fever viruses from porous concrete surfaces. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidwell, R.W.; Dixon, G.J.; Westbrook, L.; Forziati, F.H. Quantitative studies on fabrics as disseminators of viruses. V. Effect of laundering on poliovirus-contaminated fabrics. Appl. Microbiol. 1971, 21, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, M.; Kyas, A.; Weide, M.; Breves, R.; Bockmuhl, D.P. Evaluation of the virucidal performance of domestic laundry procedures. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2010, 213, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- String, G.M.; Kamal, Y.; Gute, D.M.; Lantagne, D.S. Chlorine efficacy against bacteriophage Phi6, a surrogate for enveloped human viruses, on porous and non-porous surfaces at varying temperatures and humidity. J. Environ. Health 2022, 57, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smither, S.; Phelps, A.; Eastaugh, L.; Ngugi, S.; O’Brien, L.; Dutch, A.; Lever, M.S. Effectiveness of Four Disinfectants against Ebola Virus on Different Materials. Viruses 2016, 8, 185, Erratum in Viruses 2016, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardison, R.L.; Nelson, S.W.; Barriga, D.; Ghere, J.M.; Fenton, G.A.; James, R.R.; Stewart, M.J.; Lee, S.D.; Calfee, M.W.; Ryan, S.P.; et al. Efficacy of detergent-based cleaning methods against coronavirus MHV-A59 on porous and non-porous surfaces. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2022, 19, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardison, R.L.; Nelson, S.W.; Barriga, D.; Ruiz, N.F.; Ghere, J.M.; Fenton, G.A.; Lindstrom, D.J.; James, R.R.; Stewart, M.J.; Lee, S.D.; et al. Evaluation of surface disinfection methods to inactivate the beta coronavirus murine hepatitis virus. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2022, 19, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello Mares-Guia, M.A.M.; Pereira Paiva, A.A.; Mello, V.M.; Eller, C.M.; Salvio, A.L.; Nascimento, F.F.; Silva, E.S.R.F.; Martins Guerra Campos, V.T.; Mendes, Y.d.S.; Sampaio Lemos, E.R.; et al. Effectiveness of household disinfection techniques to remove SARS-CoV-2 from cloth masks. Pathogens 2022, 11, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, A.L.; Reichel, A.; Silva, P.M.; Silva, P.G.; Pinto, J.; Calado, I.; Campos, J.; Silva, I.; Machado, V.; Laranjeira, R.; et al. UV-C irradiation-based inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 in contaminated porous and non-porous surfaces. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2022, 234, 112531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfgruber, S.; Loibner, M.; Puff, M.; Melischnig, A.; Zatloukal, K. SARS-CoV2 neutralizing activity of ozone on porous and non-porous materials. New Biotechnol. 2022, 66, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metolina, P.; de Oliveira, L.G.; Ramos, B.; Angelo, Y.d.S.; Minoprio, P.; Silva Costa Teixeira, A.C. Evaluation of the effectiveness of UV-C dose for photoinactivation of SARS-CoV-2 in contaminated N95 respirator, surgical and cotton fabric masks. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2022, 21, 1915–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardts, A.; Bockmühl, D.; Kyas, A.; Hofmann, A.; Weide, M.; Rapp, I.; Höfer, D. Testing of the adhesion of herpes simplex virus on textile substrates and its inactivation by household laundry processes. J. Biosci. Med. 2016, 4, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.K.; Nims, R.W.; McKinney, J.; Gerba, C.P. Virucidal efficacy of laundry sanitizers against SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses and influenza viruses. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijkx, G.; Hild, R.; Krijnen, E.; Lodewick, R.; Rechenbach, T.; Reinhardt, G. Testing of the fabric damage properties of bleach containing detergents. Tenside Surfactants Deterg. 2004, 41, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyan, K.; Jin, K.; Kang, J. Novel colour additive for bleach disinfectant wipes reduces corrosive damage on stainless steel. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 103, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, K.; Teschke, K.; Dimich-Ward, H.; Kennedy, S.M. Considering risks to healthcare workers from glutaraldehyde alternatives in high-level disinfection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2005, 59, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, B.W.; Wang, H.W.; Schwab, K.; Jacangelo, J. Selected mechanistic aspects of viral inactivation by peracetic acid. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 16120–16129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; West, A.M.; Teska, P.J.; Oliver, H.F.; Howarter, J.A. Assessment of early onset surface damage from accelerated disinfection protocol. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCannell, T.; Umscheid, C.A.; Agarwal, R.K.; Lee, I.; Kuntz, G.; Stevenson, K.B.; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, H. Guideline for the prevention and control of norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks in healthcare settings. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011, 32, 939–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, E.A.; Sharma, S.; Casto, B.; Needham, G.; Buckley, T.J. Effectiveness of UV-C equipped vacuum at reducing culturable surface-bound microorganisms on carpets. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 9451–9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).