Abstract

Occult hepatitis B virus infection (OBI), characterized by extremely low viral loads and the persistent intrahepatic presence of cccDNA, poses a profound challenge to global public health security. With a prevalence ranging from 0.06% to over 15% in different donor populations, OBI maintains a risk of transmission and can progress to hepatocellular carcinoma. Its prevention and control have long been limited by the sensitivity constraints of conventional detection methods, highlighting the urgent need for more sensitive diagnostic innovations. Emerging technologies offer distinct breakthroughs: ddPCR facilitates absolute quantification; CRISPR-Cas systems coupled with isothermal amplification enable rapid, point-of-care testing; third-generation sequencing resolves viral integration and mutations; and nanomaterials enhance the signal detection. This review synthesises advancements in OBI diagnostic technologies and provides a comparative overview of their strengths, limitations, and transfusion safety implications, as well as their potential applications in blood transfusion. Recommendations are also proposed to inform the advancement of OBI risk control in blood transfusion and to guide the development of novel diagnostic technologies, particularly relevant to regions with high HBV endemicity, such as China.

1. Introduction

Despite more than three decades of clinical availability of the HBV vaccine, HBV infection remains a major worldwide public health challenge [1]. Epidemiological data show that approximately one quarter of chronic HBV carriers progress to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which together account for up to 820,000 deaths annually, with the burden particularly high in African regions and the Western Pacific [2,3]. Notably, in individuals who are seronegative for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), replication-competent HBV DNA can still be detected in the liver and blood of some carriers, a condition defined as occult hepatitis B virus infection (OBI) [4,5]. OBI is categorized as seropositive (anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs positive) or seronegative (both negative) [6]. Due to the limited sensitivity of conventional serological assays, seronegative occult hepatitis B infection (OBI) cases typically lack overt clinical manifestations and are challenging to detect routinely and timely. It is important to distinguish OBI from window period infections, where HBsAg is negative but HBV DNA is detectable during early acute infection. Unlike window period infections, OBI represents a chronic state with persistent cccDNA, which can reactivate under immunosuppression [7]. Studies demonstrate that HBV DNA in the peripheral blood of patients with occult hepatitis B infection (OBI) typically exhibits intermittent low-level viremia, generally below the detection threshold of 200 IU/mL (i.e., ≈1000 copies/mL) [8]. The core mechanism underlying OBI is the persistent latency of cccDNA in hepatocyte nuclei [9]. cccDNA serves as a transcriptional template for viral replication, but its low-level transcription and immune control lead to intermittent viremia, with viral loads fluctuating below conventional detection limits [7].

Low-level viremia and the limited sensitivity of current detection technologies markedly increase the transmission risk of OBI. The sensitivity threshold of existing nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT) is 0.15 IU/mL [10], whereas the viral load of OBI often falls below this threshold. Moreover, the Poisson distribution characteristics of viral nucleic acids increase the likelihood of false negatives in pooled-sample testing, with the miss-detection rate reaching 29% in six-sample pools [11]. Epidemiological studies have shown that the positive rate of HBV DNA among HBsAg-negative blood donors ranges from 0.094% to 0.5%, with anti-HBc–only positive individuals carrying a higher risk of transmission [12,13,14]. Transfusion transmission can not only result in lifelong infection in recipients but also trigger viral reactivation under immunosuppressive conditions (with reactivation rates reaching 20–50% in patients with hematologic malignancies), and may even lead to fulminant hepatitis [15,16]. Notably, OBI prevalence may vary between first-time and repeat blood donors. Studies suggest that repeat donors have a lower OBI risk due to prior screening, highlighting the need for tailored screening strategies [12,14].

The current prevention and control system faces dual technical bottlenecks: conventional serology combined with NAT lacks sufficient sensitivity for low-load samples, and it is unable to effectively distinguish cccDNA from extracellular hepatitis B virus DNA (relaxed circular DNA, rcDNA) [17]. Meanwhile, pooled testing inevitably results in a high rate of false negatives. Given these limitations, developing ultra-sensitive assays has become a priority. This review summarizes the latest advances in novel pathogen detection strategies related to OBI, aiming to overcome the issue of “low-load missed detection” and to establish a safer safeguard for blood transfusion. Integrating novel technologies like ddPCR or CRISPR-Cas into current NAT workflows (e.g., MP-NAT or ID-NAT) requires consideration of cost, throughput, and infrastructure. For instance, CRISPR-Cas assays could be used as a rapid pre-screening tool before NAT, while ddPCR may serve as a confirmatory test for low-load samples [18,19].

2. Novel OBI Detection Technologies

Current HBV DNA detection in practice is largely NAT-based [20], including sequencing [21], nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [22], fluorescent quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) [23] and Southern blotting [24], all of which have significantly enhanced blood donation safety. In China, HBV DNA detection is typically performed using qPCR [25]. Due to the high cost and time-consuming nature of individual donor NAT (ID-NAT), most blood centers commonly employ mini pool NAT (MP-NAT) for HBV screening [19]. However, the HBV DNA levels in OBI donors are sometimes below the detection limit (LOD) of MP-NAT, which may result in a small proportion of OBI cases being missed [8]. The working principle of qPCR is based on the detection and quantification of fluorescent reporter molecules; however, amplification efficiency is influenced by multiple factors and cannot remain constant throughout the reaction, which can compromise the accuracy of quantification [26]. Therefore, it is necessary to identify a more sensitive, specific, and reliable method to enhance the detection rate of OBI and maximize the safety of blood transfusion.

2.1. dPCR and ddPCR

Digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR), as a third-generation PCR technology, originates from the combination of conventional PCR amplification techniques and microfluidic technology [27]. This technique relies on limiting dilution, end-point PCR amplification, and Poisson distribution statistics, with its core principle being the absolute quantification of nucleic acid molecules through end-point measurement. In practice, dPCR first partitions the reaction mixture into thousands to millions of individual micro-reaction units, ensuring that each unit contains zero, one, or very few copies of the target nucleic acid. These partitions are then subjected to PCR amplification until the endpoint is reached. Finally, a fluorescence detection system is used to identify positive and negative partitions, and the absolute copy number is computed from the occupancy parameter (λ) of a Poisson model, with the accuracy expressed as statistical uncertainty (e.g., 95% CI). This partitioning approach markedly enhances detection sensitivity and, by concentrating target sequences within isolated micro-reactors, effectively reduces competition between templates, thereby enabling efficient detection of rare mutations against a high-abundance wild-type sequence background [28]. In 2011, Hindson and colleagues further innovated on conventional dPCR by developing droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) [29,30], which allows partitioning the sample into thousands of nanoliter-scale droplets, enabling PCR to run separately in every droplet.

Research on ddPCR technology in the field of HBV DNA detection has been increasingly in-depth. Its potential as an auxiliary diagnostic tool for OBI has been preliminarily validated, yet its widespread clinical adoption still faces challenges. Through quantitative analysis of serum HBV DNA that ddPCR results, Piermatteo et al. [31] demonstrated that ddPCR showed a strong linear concordance with qPCR (R2 > 0.98) and a ≈10-fold lower limit of detection (1.5 vs. 15 IU/mL). Moreover, validation across multiple concentration gradients confirmed that ddPCR provides accurate, reproducible, and highly sensitive quantification ability of serum HBV DNA, supporting the method’s stability and reliability. ddPCR technology exhibits excellent resistance to interference and precise quantification capabilities. The Hayashi team [23] successfully achieved specific quantification of HBV cccDNA using ddPCR, consistently detecting ≥5 copies of cccDNA templates even in the presence of a 103-fold excess of linear HBV DNA interference. Given that serum HBV RNA levels can objectively reflect the transcriptional activity of intrahepatic HBV cccDNA, Limothai et al. [32] demonstrated that ddPCR increased the detection rate of HBV RNA in low-viral-load patients (<500 IU/mL) by more than threefold compared to qPCR, achieving 97% accuracy for detecting 5 copies per reaction and significantly enhancing the analytical performance for extremely low-abundance nucleic acid specimens. Taken together, these findings indicate that ddPCR provides clear technical advantages for detecting low-level pathogens such as OBI.

A comparison of ddPCR with currently widely used detection methods is shown in Table 1. Although ddPCR has been shown to offer significant advantages over qPCR, its high cost and low throughput limit its broader adoption in clinical practice. To address these issues, the Wang team [27] developed a novel modular ddPCR system that, by simplifying the microfluidic chip design and employing an open fluorescence detection module, substantially improves cost-effectiveness while maintaining the key performance of commercial equipment. Prospective studies [33] indicate that next-generation technologies will enable simultaneous multi-target detection within a single tube through the integration of multi-color fluorescence channels, thereby enhancing multi-parameter analytical capability compared to current systems. These breakthrough advances collectively indicate a promising potential for ddPCR in high-sensitivity detection scenarios, such as OBI screening among blood donors. It is important to note that the sensitivity of ddPCR for OBI detection can be influenced by pre-analytical factors, such as sample volume and DNA extraction efficiency. Inadequate extraction may reduce the yield of low-abundance HBV DNA, leading to false negatives. Standardizing these factors is crucial for reliable ddPCR application in clinical settings [31,32].

Table 1.

Comparison of Common HBV Diagnostic Technologies and Their Application Scenarios.

2.2. CRISPR-Cas System

In recent years, the CRISPR-associated (Cas) nuclease system, derived from clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), has received increasing attention. This system originates from the adaptive immune mechanism of prokaryotes and was first discovered by Ishino et al. in Escherichia coli in 1987 [37]. In the field of pathogen diagnostics, a key turning point occurred in 2016 with the discovery of the trans-cleavage activity of Cas12/Cas13, namely, the non-specific degradation of reporter molecules following target recognition. Compared with other rapid detection techniques, such as recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), CRISPR/Cas-based assays exhibit higher sensitivity and specificity [38]. Since the advent of CRISPR-Cas detection technology, scientists have developed multiple detection platforms based on this system, including SHERLOCK (Cas13a), DETECTR (Cas12a), CDetection (Cas12b), and Cas14-DETECTR. These platforms support quick testing with markedly improved sensitivity and precise identification for a wide range of pathogens [39,40].

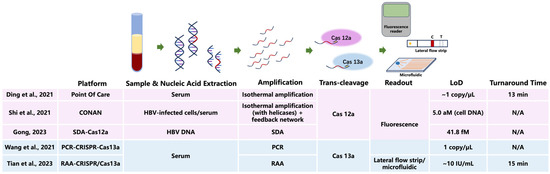

CRISPR-Cas detection technology has been extensively investigated in low-load HBV detection (Figure 1). The Ding team [18] investigated the potential application of rapid on-site detection technology based on CRISPR-Cas12a for HBV. This technology can detect HBV DNA at concentrations as low as 1 copy/μL within 13 min, demonstrating high sensitivity and specificity, while being cost-effective and suitable for on-site testing in resource-limited settings. With a detection limit near 1 copy·μL−1 and results available in 13 min, this technology combines high sensitivity and specificity with favorable cost, allowing on-site testing in settings where resources are limited. The Shi team [41] developed a CRISPR-Cas12a self-catalyzed, feedback-driven nucleic acid circuit system (CRISPR-Cas-only amplification network, CONAN). This system utilizes the collateral cleavage activity of Cas12a, which non-specifically degrades fluorescent reporter molecules (e.g., FAM-labeled ssDNA) upon target recognition, generating a fluorescence signal. Unlike traditional PCR, which relies on thermal cycling and DNA polymerization, CONAN achieves exponential amplification isothermally through a feedback loop, without the need for enzymes like polymerases. Results indicate that the CONAN system can detect genomic DNA in HBV-infected cells at concentrations as low as 5.0 aM and can also be applied to clinical serum samples from both HBV-infected and uninfected individuals, yielding results consistent with those obtained by qRT-PCR. Similarly, a team [42] combined strand displacement amplification (SDA) technology with CRISPR-Cas12a to detect low-load HBV markers. This approach enables highly sensitive detection of HBV DNA, with a detection limit as low as 41.8 fM. For perspective, 5.0 aM corresponds to approximately 3 copies/μL, and 41.8 fM is about 25,000 copies/μL, whereas typical qPCR assays for HBV have a detection limit of 10–100 copies/mL [23,26]. Furthermore, this approach can also discriminate DNA sequences with base mutations, demonstrating excellent detection specificity. The Wang team [43] developed a PCR-CRISPR-HBV DNA detection system based on CRISPR-Cas13a, capable of detecting HBV DNA at 1 copy/μL. In a study of 312 serum samples from HBV patients, the system effectively identified 10 low-copy samples that were negative by qRT-PCR. The Tian team [44] developed a RAA-CRISPR/Cas13a-based lateral flow strip assay that permits the detection of HBV at concentrations down to ~10 IU/mL. Using colloidal gold strips or microfluidic chips enables “sample-in, result-out” detection within 15 min, at a cost of less than $1 per sample, making it suitable for integration into rapid screening scenarios such as blood donation vehicles. Despite remaining challenges such as gRNA off-target effects and interference from complex sample inhibitors, CRISPR-Cas technology, with its ultra-sensitivity, portability, and low cost, holds promise to become the next-generation gold standard for OBI screening in blood donors.

Figure 1.

Workflow diagram of CRISPR-Cas12a/Cas13a assays for low-level HBV DNA detection and comparison of representative platforms. Limit of detection (LoD) values are reported as in the original publications (copy/μL, aM, fM, IU/mL) [18,41,42,43,44]. N/A, not available. CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; Cas, CRISPR-associated protein; HBV, hepatitis B virus; SDA, strand displacement amplification; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RAA, recombinase-aided amplification; IU, international unit; aM, attomolar; fM, femtomolar.

2.3. Third-Generation Sequencing Technologies

With the development of third-generation sequencing (TGS) technologies, particularly single-molecule real-time sequencing platforms such as Oxford Nanopore, it is now possible to detect HBV integration sites across the whole genome, as well as structural variations including chromosomal translocations and gene fusions. TGS thus serves as a powerful tool for comprehensively studying HBV integration within the host genome. These technologies provide new perspectives for understanding the genetic complexity of HBV and for detecting viral infections. With single-molecule real-time sequencing (e.g., Nanopore or PacBio platforms), TGS reaches a limit of detection of 1–5 copies per mL, roughly 10–100 times lower than qPCR [45]. McNaughton et al. [46] developed a circular-genome-targeted approach in which isothermal RCA enriches HBV DNA and generates long concatemers containing contiguous copies of the genome. Sequencing these products via TGS increased HBV sequencing accuracy to 99.7% and enabled the resolution of intrahost sequence variants. Integrating isothermal amplification and TGS could enable rapid, real-time detection of HBV. Lee et al. [47] developed a TGS approach based on multiplex PCR to obtain the full genome of HAV, a method that can also be applied to HBV genome analysis. TGS has shown that, for viral nucleic acid loads between 10 and 105 copies per μL, genome coverage can reach 90.4% to 99.5% within 8 h.

With its ultra-sensitivity, integrative resolution, and high-throughput adaptability, TGS is expanding the diagnostic paradigm for HBV and OBI screening. However, TGS faces challenges such as gRNA off-target effects. In gRNA-based enrichment methods, guide RNAs are designed to target specific HBV sequences for amplification or capture before sequencing. Off-target binding can lead to false positives or reduced sensitivity. Optimizing gRNA design and using computational tools can mitigate this issue [46,47]. In the context of OBI screening in blood donation samples, the integration of TGS with high-fidelity CRISPR-Cas12a technology, lyophilized reagent development, and artificial intelligence (AI)-based automated interpretation could bring transformative improvements.

2.4. Nanomaterial-Based Detection Technologies

Nanomaterials, owing to their characteristic mechanical, electronic, and optical traits, enable highly sensitive HBV detection by either amplifying the detection signal or specifically recognizing target molecules. For signal amplification, the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) can lead to a red→blue shift in coloration, allowing visual detection of HBsAg at concentrations as low as 0.1 ng/mL [48]. Nanomaterials like graphene and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) can be applied to modify electrodes, increasing the specific surface area, accelerating electron transfer, and enhancing current or impedance signals. Based on this principle, HBV DNA detection can be achieved at concentrations as low as 111 copies/mL [49]. Quantum dots (QDs) exhibit high-intensity, stable fluorescence upon excitation, and their use in fluorescence immunoassays for HBsAg detection can lower the detection limit to 1.16 pg/mL [50].

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), owing to their unique physicochemical properties, have become a key tool for enhancing diagnostic sensitivity and efficiency in HBV detection. MNPs (with diameters of 1–100 nm) can be functionalized to present HBV-targeting antibodies or aptamers, enabling the capture of HBV antigens (such as HBsAg) or viral particles from blood through antigen–antibody interactions. Upon application of an external magnetic field, MNP–target complexes can be rapidly separated, concentrating low-abundance pathogens and reducing background interference. MNPs conjugated with anti-HBs antibodies can specifically capture HBsAg from serum at concentrations as low as 5 IU/mL [51]. Moreover, due to their abundant active sites and larger catalytic surface area, MNPs can be combined with various nanomaterials to produce synergistic effects. For example, magnetite (Fe3O4) MNPs, serving as efficient biocarriers, can function as probe capture agents, while silica nanoparticles (SiNPs) loaded with rhodamine B act as fluorescent capsules and signal amplifiers, sequestering the MNPs and liberating the encapsulated dye. In this system, fluorescence intensity exhibits a linear correlation with HBsAg concentrations over the range 6.1 ag/mL to 0.012 ng/mL, with the minimum detectable limit of 5.7 ag/mL [52]. Sea urchin-like dual MNPs, gold–platinum hybrid MNPs, and L-cysteine-bridged gold–silver MNPs are currently among the most widely developed signal-generating molecules. Three-dimensional SnO2-loaded graphene sheets (GS-SnO2-BMNPs) can be integrated with these MNPs to build a sandwich immunosensor for the simultaneous detection of HBsAg and HBeAg. Based on these platforms, Dong and colleagues [53] constructed a sandwich-type electrochemical immunosensor based on MoO2 nanosheets (MoO2 NSs) decorated with gold-core, palladium-shell nanodendrites (Au@Pd NDs) for HBsAg detection, reaching a limit of detection of 3.3 fg/mL. For further investigations into the application of nanomaterials in low-load HBV detection, see Table 2. Despite the high sensitivity, nanomaterial-based assays face challenges in clinical translation. For example, whole blood components can cause interference, leading to false signals. Additionally, the stability and batch-to-batch variability of nanomaterials require rigorous standardization. Future efforts should focus on integrating nanomaterials with microfluidic chips to minimize interference and improve robustness [54].

Table 2.

Applications of Nanomaterial-Based Detection for HBV and HCV.

Compared with traditional methods, nanomaterials have attracted considerable attention in primary blood collection institutions for OBI screening due to their high sensitivity, short detection time, and minimal equipment and personnel requirements. However, the currently developed nanomaterials are generally expensive, cannot fully eliminate interference from whole blood, and have yet to be produced at a large-scale standardized level. The application of nanomaterials in OBI screening still has a long way to go. Future development of integrated microfluidic chips combined with AI-based intelligent analysis could amplify the advantages of nanoplatforms—“specific recognition, signal amplification, and portable output”—providing innovative tools for OBI screening at the primary care level.

2.5. Comparative Analysis and Practical Readiness for Transfusion Screening

To provide a clearer sense of real-world readiness, we qualitatively compared the four major technology families discussed above—ddPCR, CRISPR-Cas-based assays, TGS, and nanomaterial-based platforms—in terms of analytical performance and implementation characteristics (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative overview of emerging HBV/OBI detection technologies.

3. Summary and Outlook

Building on the comparative assessment above, future OBI prevention and control should focus on technological integration and clinical translation. In the field of detection, the high cost and low throughput of ddPCR can be mitigated through modular chip design and the integration of multi-color fluorescence channels, promoting its large-scale application in blood donation screening. CRISPR-Cas systems need to overcome challenges such as gRNA off-target effects and interference from complex samples, while combining with lyophilized reagent development to enhance the stability of on-site testing. TGS technology should be integrated with artificial intelligence to enable automated analysis of large datasets, thereby improving the clinical interpretability of HBV integration sequences. Future directions include the use of AI-driven algorithms to integrate multi-parameter data (e.g., from ddPCR, CRISPR, and antigen markers) for improved OBI detection. Machine learning models can enhance interpretation accuracy and reduce false positives. Research on inactivation technologies must balance pathogen clearance efficacy with the functional preservation of blood components, while exploring novel photochemical or nanomaterial-based strategies targeting cccDNA. For clinical translation, key milestones include regulatory validation (e.g., FDA approval), multi-center clinical trials to establish sensitivity and specificity, and cost-effectiveness analyses. For example, ddPCR requires validation in large donor cohorts to standardize its use in blood screening. Furthermore, harmonization of OBI testing standards globally, especially in high-endemicity regions like China, is essential to ensure transfusion safety. International collaborations should establish guidelines for technology adoption and quality control. Moreover, multi-platform integration is an inevitable trend. For example, CRISPR-based pre-enrichment combined with ddPCR absolute quantification can establish a two-tiered “screening–confirmation” system, while nanomaterial-based microfluidic chips integrated with AI analysis have the potential to achieve an all-in-one “recognition–signal amplification–output” workflow. These breakthroughs will drive OBI detection from a “single-target” approach toward “multi-dimensional markers (DNA/RNA/antigen),” ultimately establishing an ultra-sensitive, low-cost, fully automated blood safety barrier and providing critical technological support for global hepatitis elimination initiatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y. and B.F.; investigation, B.F. and Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y. and Y.H.; writing—review and editing, B.P. and J.W.; final revised manuscript, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences [grant number 2021-I2M-1-060].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| OBI | Occult hepatitis B virus infection |

| HBsAg | Hepatitis B surface antigen |

| anti-HBc | Hepatitis B core antibody |

| anti-HBs | Hepatitis B surface antibody |

| cccDNA | Covalently closed circular DNA |

| rcDNA | Relaxed circular DNA |

| NAT | Nucleic acid testing |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| dPCR | Digital polymerase chain reaction |

| ddPCR | Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction |

| LoD | Limit of detection |

| RPA | Recombinase polymerase amplification |

| LAMP | Loop-mediated isothermal amplification |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| Cas | CRISPR-associated |

| SHERLOCK | Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter unLOCKing |

| DETECTR | DNA Endonuclease-Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter |

| SDA | Strand displacement amplification |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| TGS | Third-generation sequencing |

| RCA | Rolling-circle amplification |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

References

- Jeng, W.J.; Papatheodoridis, G.V.; Lok, A.S.F. Hepatitis B. Lancet 2023, 401, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.-C.; Huang, D.Q.; Nguyen, M.H. Global burden of hepatitis B virus: Current status, missed opportunities and a call for action. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.C.; Nguyen, M.H. Curing chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 392–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitta, C.; Pollicino, T.; Raimondo, G. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection: An Update. Viruses 2022, 14, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, N.A.A.; de Paula, V.S. Occult Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and challenges for hepatitis elimination: A literature review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 1616–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Kwok, R.M.; Tran, T.T. Isolated anti-HBc: The Relevance of Hepatitis B Core Antibody-A Review of New Issues. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 1780–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucio-Ortiz, L.; Enriquez-Navarro, K.; Maldonado-Rodríguez, A.; Torres-Flores, J.M.; Cevallos, A.M.; Salcedo, M.; Lira, R. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Hepatic Diseases and Its Significance for the WHO’s Elimination Plan of Viral Hepatitis. Pathogens 2024, 13, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.X.; Simmonds, P.; Andersson, M.; Harvala, H. Biomarkers of transfusion transmitted occult hepatitis B virus infection: Where are we and what next? Rev. Med. Virol. 2024, 34, e2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Zhang, P.; Fang, Y.; Han, N.; Yang, W.; Xia, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J. The role of HBV cccDNA in occult hepatitis B virus infection. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2023, 478, 2297–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candotti, D.; Assennato, S.M.; Laperche, S.; Allain, J.-P.; Levicnik-Stezinar, S. Multiple HBV transfusion transmissions from undetected occult infections: Revising the minimal infectious dose. Gut 2019, 68, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D. Quantification using real-time PCR technology: Applications and limitations. Trends Mol. Med. 2002, 8, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, Y.R.; Jagdish, R.; Leith, D.; Kim, J.U.; Yoshida, K.; Majid, A.; Ge, Y.; Ndow, G.; Shimakawa, Y.; Lemoine, M. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Xue, R.; Wang, X.; Xiao, L.; Xian, J. High-sensitivity HBV DNA test for the diagnosis of occult HBV infection: Commonly used but not reliable. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1186877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Wu, W.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Hu, M. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of hepatitis B surface antigen-negative/hepatitis B core antibody-positive patients with detectable serum hepatitis B virus DNA. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morozov, S.; Batskikh, S. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection—An important aspect of multifaceted problem. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 3193–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, B.; Valdes, J.D.; Sun, J.; Guo, H. Serum Hepatitis B Virus RNA: A New Potential Biomarker for Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1816–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, E.; Mirshahabi, H.; Motamed, N.; Sadeghi, H. Prevalence of Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Hemodialysis Patients Using Nested PCR. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 9, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Long, J.; Yuan, M.; Zheng, X.; Shen, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Duan, G. CRISPR/Cas12-Based Ultra-Sensitive and Specific Point-of-Care Detection of HBV. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, L.; Nie, X.; Huang, L.; Ye, D.; Zeng, J.; Li, T.; Li, B.; Xu, M.; et al. High-Frequency Notable HBV Mutations Identified in Blood Donors With Occult Hepatitis B Infection From Heyuan City of Southern China. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 754383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Guo, X.; Li, T.; Laperche, S.; Zang, L.; Candotti, D. Alternative hepatitis B virus DNA confirmatory algorithm identified occult hepatitis B virus infection in Chinese blood donors with non-discriminatory nucleic acid testing. Blood Transfus. 2022, 20, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gionda, P.O.; Gomes-Gouvea, M.; Malta, F.d.M.; Sebe, P.; Salles, A.P.M.; Francisco, R.d.S.; José-Abrego, A.; Roman, S.; Panduro, A.; Pinho, J.R.R. Analysis of the complete genome of HBV genotypes F and H found in Brazil and Mexico using the next generation sequencing method. Ann. Hepatol. 2022, 27, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Sun, K.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X. Application of nested PCR in the detection of occult hepatitis B virus infection in blood donors. Chin. J. Exp. Clin. Virol. 2023, 37, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, S.; Isogawa, M.; Kawashima, K.; Ito, K.; Chuaypen, N.; Morine, Y.; Shimada, M.; Higashi-Kuwata, N.; Watanabe, T.; Tangkijvanich, P.; et al. Droplet digital PCR assay provides intrahepatic HBV cccDNA quantification tool for clinical application. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allweiss, L.; Testoni, B.; Yu, M.; Lucifora, J.; Ko, C.; Qu, B.; Lütgehetmann, M.; Guo, H.; Urban, S.; Fletcher, S.P.; et al. Quantification of the hepatitis B virus cccDNA: Evidence-based guidelines for monitoring the key obstacle of HBV cure. Gut 2023, 72, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.K. History and Future of Nucleic Acid Amplification Technology Blood Donor Testing. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2019, 46, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Cai, Q.; Li, H.; Hu, P. Comparison of droplet digital PCR to real-time PCR for quantification of hepatitis B virus DNA. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 80, 2159–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, B.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, W. An integrated digital PCR system with high universality and low cost for nucleic acid detection. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 947895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Parvin, R.; Fan, Q.; Ye, F. Emerging digital PCR technology in precision medicine. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 211, 114344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, D.; Zhang, L.; Suo, T.; Hu, W.; Guo, M.; Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; et al. Analytical comparisons of SARS-COV-2 detection by qRT-PCR and ddPCR with multiple primer/probe sets. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sang, B.; He, L.; Guo, Y.; Geng, M.; Zheng, D.; Xu, X.; Wu, W. Construction of dPCR and qPCR integrated system based on commercially available low-cost hardware. Analyst 2022, 147, 3494–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piermatteo, L.; Scutari, R.; Chirichiello, R.; Alkhatib, M.; Malagnino, V.; Bertoli, A.; Iapadre, N.; Ciotti, M.; Sarmati, L.; Andreoni, M.; et al. Droplet digital PCR assay as an innovative and promising highly sensitive assay to unveil residual and cryptic HBV replication in peripheral compartment. Methods 2022, 201, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limothai, U.; Chuaypen, N.; Poovorawan, K.; Chotiyaputta, W.; Tanwandee, T.; Poovorawan, Y.; Tangkijvanich, P. Reverse transcriptase droplet digital PCR vs reverse transcriptase quantitative real-time PCR for serum HBV RNA quantification. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 3365–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.C.; Nadeau, K.; Abbasi, M.; Lachance, C.; Nguyen, M.; Fenrich, J. The Ultimate qPCR Experiment: Producing Publication Quality, Reproducible Data the First Time. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Q. Comparison of the application effect of nucleic acid test and ELISA test in the screening of hepatitis B virus (HBV)in blood samples of unpaid blood donations. China Contemp. Med. 2021, 27, 151–152. [Google Scholar]

- Olmedillas-López, S.; Olivera-Salazar, R.; García-Arranz, M.; García-Olmo, D. Current and Emerging Applications of Droplet Digital PCR in Oncology: An Updated Review. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2022, 26, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bio-Red. Automated Droplet Generator #1864101. June 2024. Available online: https://www.bio-rad.com/webroot/web/pdf/lsr/literature/10043138.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Wei, L.; Wang, Z.; She, Y.; Fu, H. CRISPR/Cas Multiplexed Biosensing: Advances, Challenges, and Perspectives. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 11943–11958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchsung, M.; Jantarug, K.; Pattama, A.; Aphicho, K.; Suraritdechachai, S.; Meesawat, P.; Sappakhaw, K.; Leelahakorn, N.; Ruenkam, T.; Wongsatit, T.; et al. Clinical validation of a Cas13-based assay for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gootenberg, J.S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Lee, J.W.; Essletzbichler, P.; Dy, A.J.; Joung, J.; Verdine, V.; Donghia, N.; Daringer, N.M.; Freije, C.A.; et al. Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science 2017, 356, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetsche, B.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Slaymaker, I.M.; Makarova, K.S.; Essletzbichler, P.; Volz, S.E.; Joung, J.; van der Oost, J.; Regev, A.; et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell 2015, 163, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Xie, S.; Tian, R.; Wang, S.; Lu, Q.; Gao, D.; Lei, C.; Zhu, H.; Nie, Z. A CRISPR-Cas autocatalysis-driven feedback amplification network for supersensitive DNA diagnostics. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S. Research on Enzyme-Catalyzed Real-Time Nucleic Acid Detection Methods Based on CRISPR-Cas12a. Ph.D. Thesis, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, H.; Kou, Z.; Ren, F.; Jin, Y.; Yang, L.; Dong, X.; Yang, M.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Highly sensitive and specific detection of hepatitis B virus DNA and drug resistance mutations utilizing the PCR-based CRISPR-Cas13a system. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Fan, Z.; Xu, L.; Cao, Y.; Chen, S.; Pan, Z.; Gao, Y.; Li, H.; Zheng, S.; Ma, Y.; et al. CRISPR/Cas13a-assisted rapid and portable HBV DNA detection for low-level viremia patients. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, e2177088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Garcia, S.; Cortese, M.F.; Rodríguez-Algarra, F.; Tabernero, D.; Rando-Segura, A.; Quer, J.; Buti, M.; Rodríguez-Frías, F. Next-generation sequencing for the diagnosis of hepatitis B: Current status and future prospects. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 21, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton, A.L.; Roberts, H.E.; Bonsall, D.; de Cesare, M.; Mokaya, J.; Lumley, S.F.; Golubchik, T.; Piazza, P.; Martin, J.B.; de Lara, C.; et al. Illumina and Nanopore methods for whole genome sequencing of hepatitis B virus (HBV). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.-Y.; Park, K.; Lee, Y.-S.; Kim, J.H.; Byun, K.S.; Kim, J.; Kim, W.-K.; Song, J.-W. Molecular diagnosis of patients with hepatitis A virus infection using amplicon-based nanopore sequencing. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, W.; Peng, W.; Zhao, Q.; Piao, J.; Zhang, B.; Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Gong, X.; Chang, J. Enhanced Fluorescence ELISA Based on HAT Triggering Fluorescence “Turn-on” with Enzyme-Antibody Dual Labeled AuNP Probes for Ultrasensitive Detection of AFP and HBsAg. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 9369–9377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Lai, Z.-L.; Wang, G.-J.; Wu, C.-Y. Polymerase chain reaction-free detection of hepatitis B virus DNA using a nanostructured impedance biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 77, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zeng, L.; Xiong, Y.; Leng, Y.; Wang, H.; Xiong, Y. Fluorescence ELISA based on glucose oxidase-mediated fluorescence quenching of quantum dots for highly sensitive detection of Hepatitis B. Talanta 2018, 181, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delshadi, S.; Fratzl, M.; Ramel, O.; Bigotte, P.; Kauffmann, P.; Kirk, D.; Masse, V.; Brenier-Pinchart, M.P.; Fricker-Hidalgo, H.; Pelloux, H.; et al. Magnetically localized and wash-free fluorescence immunoassay (MLFIA): Proof of concept and clinical applications. Lab A Chip 2023, 23, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, P.; Dong, Y. Simultaneous electrochemical determination of two hepatitis B antigens using graphene-SnO2 hybridized with sea urchin-like bimetallic nanoparticles. Mikrochim. Acta 2021, 188, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, P.; Ma, E.; Yu, H.; Zhou, K.; Tang, C.; Ren, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Dong, Y. A sandwich-type electrochemical immunosensor based on Au@Pd nanodendrite functionalized MoO2 nanosheet for highly sensitive detection of HBsAg. Bioelectrochemistry 2021, 138, 107713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevtsov, M.; Zhao, L.; Protzer, U.; van de Klundert, M.A.A. Applicability of Metal Nanoparticles in the Detection and Monitoring of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Viruses 2017, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Hu, Y.; Chen, M.; An, J.; Lyu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, D. Naked-Eye Detection of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Using Gold Nanoparticles Aggregation and Catalase-Functionalized Polystyrene Nanospheres. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 9828–9833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; He, X.; Ju, L.; Liu, X.; Li, F.; Cui, H. A label-free method for the detection of specific DNA sequences using gold nanoparticles bifunctionalized with a chemiluminescent reagent and a catalyst as signal reporters. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 8747–8754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z.; Gong, Q.; Wang, C.; Zheng, B. Highly sensitive chemiluminescent aptasensor for detecting HBV infection based on rapid magnetic separation and double-functionalized gold nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Yang, H.; Gong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Wen, T.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Mei, Q.; Xu, F. Improved Analytical Sensitivity of Lateral Flow Assay using Sponge for HBV Nucleic Acid Detection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Fu, Q.; Peng, J.; Wang, Y.; Du, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhan, L. Gold nanorod-based localized surface plasmon resonance biosensor for sensitive detection of hepatitis B virus in buffer, blood serum and plasma. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Dong, X.; Zhang, K.; Han, X.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y. A gold nanorods-based fluorescent biosensor for the detection of hepatitis B virus DNA based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Analyst 2013, 138, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, B.H.; Lee, S.-M.; Park, J.C.; Hwang, K.S.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, Y.-S.; Ju, B.-K.; Kim, T.S. Detection of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) DNA at femtomolar concentrations using a silica nanoparticle-enhanced microcantilever sensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 25, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, H.; Chen, J.; Han, H.; Ma, W. Simple and sensitive detection of HBsAg by using a quantum dots nanobeads based dot-blot immunoassay. Theranostics 2014, 4, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Qiu, H.; Xiao, Q.; Huang, C.; Su, W.; Hu, B. A simple QD-FRET bioprobe for sensitive and specific detection of hepatitis B virus DNA. J. Fluoresc. 2013, 23, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Q.; Huang, J.; Huang, H.; Mao, W.; Ye, Z. A label-free electrochemical platform for the highly sensitive detection of hepatitis B virus DNA using graphene quantum dots. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 1820–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, S.K.; Shen, S.-K.; Chiang, C.-W.; Weng, Y.-Y.; Lu, M.-P.; Yang, Y.-S. Silicon Nanowire Field-Effect Transistor as Label-Free Detection of Hepatitis B Virus Proteins with Opposite Net Charges. Biosensors 2021, 11, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, A.A.; Lo Faro, M.J.; Petralia, S.; Fazio, B.; Musumeci, P.; Conoci, S.; Irrera, A.; Priolo, F. Ultrasensitive Label- and PCR-Free Genome Detection Based on Cooperative Hybridization of Silicon Nanowires Optical Biosensors. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 1690–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, D.G.; Lima, E.C.; Moura, P.; Dutra, R.F. A label-free electrochemical immunosensor for hepatitis B based on hyaluronic acid-carbon nanotube hybrid film. Talanta 2016, 148, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaralı, E.; Erdem, A. Cobalt Phthalocyanine-Ionic Liquid Composite Modified Electrodes for the Voltammetric Detection of DNA Hybridization Related to Hepatitis B Virus. Micromachines 2021, 12, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, N.; Hallaj, R.; Salimi, A. A highly sensitive electrochemical immunosensor for hepatitis B virus surface antigen detection based on Hemin/G-quadruplex horseradish peroxidase-mimicking DNAzyme-signal amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 94, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zheng, C.; Cui, M.; Zhang, X.; Yang, D.-P.; Wang, X.; Cui, D. Graphene oxide wrapped with gold nanorods as a tag in a SERS based immunoassay for the hepatitis B surface antigen. Mikrochim. Acta 2018, 185, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).