Abstract

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is a popular nutritious vegetable crop grown in Malaysia and other parts of the world. However, fungal diseases such as anthracnose pose significant threats to tomato production by reducing the fruit quality and food value of tomato, resulting in lower market prices of the crop globally. In the present study, the etiology of tomato anthracnose was investigated in commercial tomato farms in Sabah, Malaysia. A total of 22 fungal isolates were obtained from anthracnosed tomato fruits and identified as Colletotrichum species, using morphological characteristics. The phylogenetic relationships of multiple gene sequence alignments such as internal transcribed spacer (ITS), β-tubulin (tub2), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh), actin (act), and calmodulin (cal), were adopted to accurately identify the Colletotrichum species as C. truncatum. The results of pathogenicity tests revealed that all C. truncatum isolates caused anthracnose disease symptoms on inoculated tomato fruits. To our knowledge, the present study is the first report of tomato anthracnose caused by C. truncatum in Malaysia. The findings of this study will be helpful in disease monitoring, and the development of strategies for effective control of anthracnose on tomato fruits.

1. Introduction

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) belongs to the Solanaceae family, and is popular for its huge nutritious and economic value. A variety of diseases attack tomato fruits and plants, including major fungal diseases that threaten tomato production globally, such as anthracnose, early blight, late blight, leaf mold, septoria leaf spot, powdery mildew, fusarium wilt, and verticilium wilt [1]. Colletotrichum spp. are important plant pathogens, causing anthracnose diseases in a diverse range of host plants, including vegetables, fruits, legumes, cereals, herbaceous, conifers, woody, and ornamental plants, at both developing and mature stages of plant growth [2,3,4]. Some taxa are restricted to certain host species, or cultivars, while others have extensive host ranges [2,4,5]. Colletotrichum spp. are commonly associated with tomato anthracnose of which C. truncatum has been reported as an emerging pathogen causing huge yield losses of tomato annually.

Differentiation of Colletotrichum spp. on the basis of host associations alone is not a reliable criterion for species identification, because a few taxa such as C. acutatum, C. dematium, and C. gloeosporioides, infect a wide range of plant hosts. Therefore, taxonomic classification of Colletotrichum species has primarily focused on identification and characterization of sub-populations within the species [6,7,8]. The conventional identification and characterisation of Colletotrichum species mainly relied on morphological differences of wide variety of isolates from ample ranges of host crops. However, morphological characteristics alone are also not reliable for identification of Colletotrichum species, due to a variety of variables such as the environment, which influences the stability of the morphological traits and the coexistence of intermediate forms in nature [9].

PCR tests and DNA sequence alignments from multiple genes have been widely utilized to overcome the limitations of morphological characterisation in accurate species delineation [10], and data generated from nucleic acid tests have provided a reliable framework for building the taxonomic classification of Colletotrichum species [11]. A study by Photita et al. [12], showed that sequence analysis based on ITS regions are helpful in determining the phylogenetic relationships within the Colletotrichum species [12]. Apart from the ITS region, partial tub2, gapdh, act and cal genes sequence analyses have also been employed to resolve the phylogenetic relationships within the C. truncatum species [13,14]. The utilisation of morphological studies coupled with sophisticated molecular data has proven to be an efficient method in identifying C. truncatum isolates and has increased the understanding of its taxonomy [2,9]. Thus, in the present study, polyphasic identification involving morphological and molecular characterisation was adopted for the substantive identification of C. truncatum isolates recovered from diseased tomato fruits. Pathogenicity tests were also conducted to assess the pathogenic ability of the C. truncatum isolates on artificially inoculation tomato fruits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Fungal Isolation

Tomato fruit samples showing typical anthracnose symptoms were collected from three commercial tomato gardens in Sabah, Malaysia. The samples were placed in zip-lock plastic bags, and conveyed to the Biotechnology laboratory of Universiti Malaysia Sabah for fungal isolation. Diseased tissues were cut into smaller pieces of about 1 cm2, and surface-sterilised by soaking in 70% ethanol for 3 min, followed by 1% sodium hypochlorite for 3 min, and rinsed for 1 min each in three changes of sterile distilled water. The sterilised samples were then placed on sterile potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium and incubated under room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) for one week, to obtain fungal mycelial growths. The resulting fungal mycelia were sub-cultured on new PDA plates, and pure cultures of fungal isolates were obtained following the single conidium isolation method previously reported by Zhang et al. [15].

2.2. Morphological Characteristics

Fungal isolates obtained were cultured onto PDA plates and incubated at 25 ± 2 °C for 7 days. The macroscopic characteristics such as colony appearance; pigmentation; and mycelial growth rate were recorded. For microscopic characteristics, the arrangement, shape, and size of acervuli; conidia; conidiogenous cells; appressoria; and setae were examined. Preliminary identification was in accordance with the fungal descriptions of Cabrera et al. [16].

2.3. Extraction of Genomic DNA, PCR Amplification, and DNA Sequencing

All isolates were cultured on potato dextrose broth (PDB) and incubated at 25 ± 2 °C for 5 days. After incubation, the fungal mycelia were harvested from the broth cultures, dried on sterile filter papers, and homogenized into fine powder, using liquid nitrogen. A total of 60 mg of the fine powder was transferred into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube for DNA extraction using Invisorb Spin Plant Mini Kit (Stratec, Birkenfeld, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA samples were preserved at –20 °C for PCR amplifications. The extracted genomic DNA samples were subjected to PCR amplifications in Thermal Cycler (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA) using five primer pairs, ITS (ITS1/ITS4), tub2 (Bt2a/Bt2b), gapdh (GDF1/GDR1), act (ACT-512F/ACT-783R) and cal (CAL-228F/CAL-737R) (The primer sequences are provided in Table 1). The amplification reactions were carried out in a total volume of 50 μL consisting 8 μL Green GoTaq® Flexi Buffer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 8 μL MgCl2 solution (Promega, Wisconsin, USA), 1 μL dNTP mix (Promega, Wisconsin, USA), 8 μL of each primer (Promega, USA), 0.3 μL GoTaq® DNA polymerase (Promega, Wisconsin, USA), 1 μL genomic DNA, and sterile distilled water to make up a total volume of 50 μL.

Table 1.

Primers used for PCR amplifications and DNA sequencing.

PCR reactions were carried out in a MyCyclerTM Thermal Cycler (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA), with initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 32 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 56 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. Final extension was performed at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were detected in agarose gel electrophoresis (1%), and sent to a service provider (First BASE Laboratories Sdn Bhd, Seri Kembangan, Malaysia) for DNA purification and sequencing.

2.4. Sequences Alignment, BLAST, and Phylogenetic Analysis

The forward and reverse DNA sequences obtained were aligned using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software, version 11, to create a consensus sequence for each isolate [22]. The identity of the fungal isolates was determined based on the highest percentage of sequence similarity on GenBank, using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Multiple sequence alignments of ITS region, tub2, gapdh, act and cal genes were performed to determine the fungal species and their phylogenetic relationships. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method on the MEGA11 software. For the ML method, a model test was run to select the best nucleotide substitution model. Kimura 2-parameter + gamma distribution (K2 + G) model was adopted to construct a robust phylogenetic tree, and the robustness of the tree was evaluated using a bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates.

2.5. Pathogenicity Assays

The pathogenicity of all obtained fungal isolates was assessed on healthy fruits of tomato using the wound inoculation method previously described by Cabrera et al. [16].

Fungal isolates were cultured on PDA for 7 days at 25 ± 2 °C, and fungal conidial suspensions were prepared by flooding the culture plates with sterile distilled water. A sterilized glass spreader was used to extricate conidia, and the concentration was adjusted to 1 × 106 conidia/mL using a haemocytometer (Weber, Teddington, UK). Prior to inoculation of wounded fruits, disease-free fruits of tomato were surface-sterilized by swabbing with 70% ethanol, the surface-sterile fruits were wounded by pricking with a sterile toothpick, and inoculated by applying sterile cotton wools immersed in the prepared conidial suspensions (~200 μL) at the wounded sites. Wounded fruits inoculated with sterile distilled water served as control.

All inoculated fruits were placed in a plastic tray and sealed with a transparent plastic wrap. The trays were kept humid by placing petridishes containing water inside the tray to maintain approximately 80% relative humidity. Symptoms that developed on inoculated fruits were observed and recorded. After 7 days of inoculation, the lesion area was measured and recorded. Differences in the lesion area were determined by one-way analysis of variance, and means were compared by the Tukey’s test at 5% level of probability, using the IBM SPSS Statistics software version 26. Fungal isolates were re-isolated from the symptomatic inoculated fruits of tomato and re-identified based on the morphological characteristics of the original cultures to confirm Koch’s postulates.

3. Results

3.1. Disease Survey

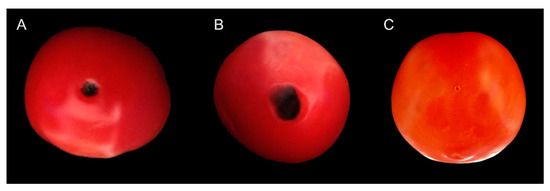

Typical symptoms of anthracnose disease were observed on tomato fruits (Figure 1). Fruit symptoms began as small, dark, sunken lesions that had a water-soaked appearance, which increased in diameter and coalesced, leaving a larger sunken soft area. Lesions on ripe fruits became visible within one week of infection.

Figure 1.

Symptoms of tomato anthracnose observed in the tomato gardens in Sabah, Malaysia.

3.2. Fungal Isolation and Morphological Characterisation

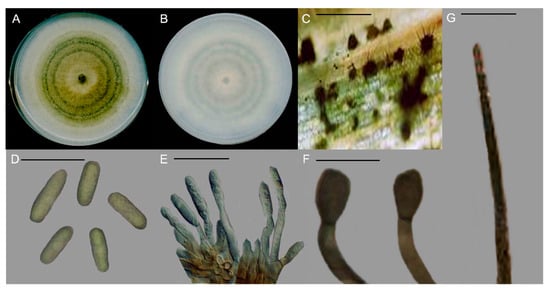

A total of 22 fungal isolates were recovered from tomato fruits showing anthracnose symptoms, and identified as Colletotrichum spp. through examination of macro- and microscopic characteristics. The colony was greenish-white, and pigmentation was greyish-white in color (Figure 2A,B). The average growth rate among the fungal isolates varied from 1.21 ± 0.27 to 1.67 ± 0.34 cm/d. Acervuli were scattered, irregularly shaped, and dark brown to black in color (Figure 2C). Conidia were hyaline, aseptate, and fusiform to rarely cylindrical, with the average size 13.4 to 18.9 × 5.2 to 7.3 µm (Figure 2D). Conidiogenous cells were hyaline, short, aseptate, and cylindrical, with sizes ranging from 11.2 to 16.33 × 4.6 to 5.7 µm (Figure 2E). Appressoria were simple, smooth, clavate to ovate, and dark brown, with sizes ranging from 10.2 to 14.6 × 7.6 to 9.4 µm (Figure 2F). Seta was dark brown, with tip more or less acute and acircular, ranging from 74.6 to 112.4 µm in size (Figure 2G).

Figure 2.

Morphological characteristics of Colletotrichum truncatum. (A) Colony appearance. (B) Pigmentation. (C) Acervuli. (D) Conidia. (E) Conidiogenous cell. (F) Appressoria. (G) Seta. Scale, (C,E,G) = 20 µm & (D,F) = 50 µm.

3.3. Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis

Molecular identification based on the concatenated alignments of the ITS region, tub2, gapdh, act, and cal genes confirmed the identification of 22 fungal isolates collected from anthracnose symptomatic fruits of tomato. Based on the BLAST search, all the fungal isolates showed 99–100% sequence similarity to the isolates GQ485593 (ITS), GQ849429 (tub2), GQ856753 (gapdh), GQ856783 (act), and GQ849453 (cal) of C. truncatum (CBS 120709). The accession numbers of all the DNA sequences of the fungal isolates obtained in the present study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Fungal isolates obtained from the present study and reference species used for sequence comparisons and phylogenetic analysis of Colletotrichum truncatum.

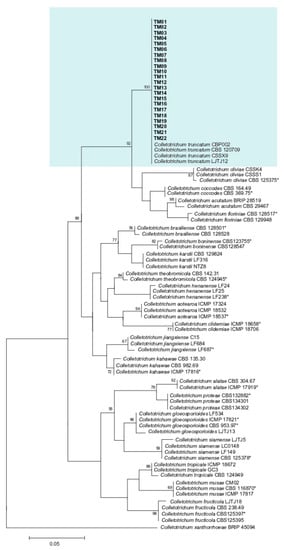

The phylogenetic tree derived from the combined ITS, tub2, gapdh, act, and cal sequences of C. truncatum showed that all 22 fungal isolates were clustered along with the reference strains of C. truncatum (CBP002, CBS 120709, CSSX9, and LJTJ12). The clade was supported by a bootstrap value of 100% (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Maximum likelihood (ML) tree of Colletotrichum truncatum generated from analysis of the concatenated ITS region, tub2, gapdh, act and cal genes, with Colletotrichum xantharrhoeae as outgroup. Asterisks indicate ex-type isolates. The isolates used in the present study are indicated in bold font and highlighted in. Only bootstrap values > 50% are shown.

3.4. Pathogenicity Assays

All the tested isolates of Colletotrichum truncatum were pathogenic on the tomato fruits by causing anthracnose lesions varying in size from 1.03 ± 0.13 to 1.46 ± 0.17 cm2 after 7 days of inoculation (Table 3). Symptoms of anthracnose and lesion sizes among the isolates of C. truncatum were significantly different (p ˂ 0.05). Initially, the inoculated tomato fruits showed small, circular to irregular dark chlorotic lesions, but After 7 days, the symptoms appeared as darker, sunken, and circular lesions, with the formation of concentric rings in the middle of the symptomatic areas which were similar to the field conditions (Figure 4A,B). The control experiments were asymptomatic (Figure 4C). The same fungal isolates were re-isolated from the symptomatic inoculated fruits of tomato, thus confirming C. truncatum as the pathogenic agent of anthracnose of tomato in Malaysia.

Table 3.

Lesion areas produced by C. truncatum isolates on inoculated fruits of tomato.

Figure 4.

Pathogenicity of Colletotrichum truncatum on tomato fruits after 7 days of inoculation.

4. Discussion

A total of 22 fungal isolates associated with anthracnose of tomato fruits in the present study were identified as Colletotrichum truncatum through morphological and molecular characterisation. Although morphological characteristics are sufficient to distinguish between Colletotrichum species and fungi of other genera, inter-specific discrimination within the genus is often difficult as a result of overlaps in configuration of morphological features among identical Colletotrichum species [23,24,25]. This implies that the identification of Colletotrichum species only based on morphological distinctions may result in uncertainties in delineation of the genus [9,14].

A more precise approach will be the combination of morphological characteristics and molecular analysis for the accurate identification of Colletotrichum species [12]. A study of phylogenetic relationships could also reveal useful information on the genomic delineation of C. truncatum, which causes anthracnose of tomato. Thus, in the present study, multiple gene sequence alignments of ITS, tub2, gapdh, act and cal were shown to be effective in identifying C. truncatum from anthracnose of tomato. In related studies, Liu et al. [13] and Weir et al. [14] also used those five conserved genes to accurately identify and resolve the phylogenetic status of Colletotrichum species.

The present study highlighted the occurrence of tomato anthracnose in Malaysia. All the isolates of C. truncatum isolated in the present study caused anthracnose of tomato with varying degrees of severity. Although C. boninense was earlier reported to be associated with tomato anthracnose in Pahang, Malaysia [26], this study is the first report of tomato anthracnose caused by C. truncatum in Malaysia. Other reports of tomato anthracnose caused by C. truncatum have been published in China [27], India [28] and Trinidad [29].

Generally, Colletotrichum is a genus of diverse plant pathogenic fungi which causes diseases in a wide variety of plant species worldwide, and several Colletotrichum species have the capacity to infect a single host-plant, and a single Colletotrichum species is also capable of infecting several hosts [2,3,4,5]. A broad range of host species including avocado, chilli, mango, olive, papaya, strawberry, and watermelon, can be infected by different Colletotrichum species worldwide [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Anthracnoses caused by Colletotrichum spp. are important diseases in Malaysia, infecting numerous hosts such as banana, chilli, dragon fruit, eggplant, and watermelon [37,38,39,40,41]. Previous reports also identified Colletotrichum acutatum, C. coccodes, C. dematium, and C. gloeosporioides as the causative agents of tomato anthracnose globally [16,42].

5. Conclusions

In the present study, morphological traits coupled with multigene phylogenetic analysis were effective in identifying C. truncatum as the fungal species associated with diseased tomato fruits showing symptoms of anthracnose in Malaysia. Pathogenicity tests further revealed that C. truncatum was the causative agent of anthracnose of tomato fruits. This confirms that C. truncatum is an emerging pathogen that is capable of causing anthracnose disease which may threaten the yield and profitability of tomato production as well as the other crops in regions where it has already been established. Information on disease symptomatology, etiology, epidemiology and pathogenesis provided by this study could be useful in disease monitoring and formulation of strategies for effective management of anthracnose, thus reducing yield losses of tomatoes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.S., M.A.R., A.N.F.A., J.U. and S.S.; investigation, A.H., T.T.P., M.N.K.E., M.Q. and A.B.S.; formal analysis, A.H., M.N.K.E., M.Q., A.B.S. and A.N.F.A.; writing—original draft, S.A.S.; writing—review and editing, S.A.S., T.T.P., M.A.R., J.U. and S.S.; final submission, S.A.S., M.A.R., J.U. and S.S.; Funding, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was funded by ‘Strengthening Integrated Research Facilities (SIRF)’ project of Bangladesh Sugarcrop Research Institute (BSRI), Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), Bangladesh and project code number (GLA0026-2019).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Panthee, D.R.; Chen, F. Genomics of fungal disease resistance in tomato. Curr. Genomics. 2010, 11, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, P.F.; Damm, U.; Johnton, P.R.; Weir, B.S. Colletotrichum-current status and future directions. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 181–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, C.; Carbu, N.; Fernandez-Acero, F.J.; Vallejo, I.; Cantoral, J.M. Phylogenetic relationships and genome organization of Colletotrichum acutatum causing anthracnose in strawberry. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2009, 125, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.Y.; Chen, M.Y.; Chen, Y.K.; Wang, T.C.; Sheu, Z.M.; Kuo, K.C.; Chang, P.F.L.; Chung, K.R.; Lee, M.H. Characterization of three Colletotrichum acutatum isolates from Capsicum spp. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 133, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, A.; Dolar, F.S. Colletotrichum acutatum, a new pathogen of hazelnut. J. Phytopathol. 2012, 160, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardo, B.; Amby, D.B.; Zapparata, A.; Sarrocco, S.; Vannacci, G.; Le Floch, G.; Harrison, R.J.; Holub, E.; Sukno, S.A.; Sreenivasaprasad, S.; et al. Gene family expansions and contractions are associated with host range in plant pathogens of the genus Colletotrichum. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 555. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T. Studies on the taxonomy and identification of plant pathogenic fungi, based on morphology and phylogenetic analyses, and fungal pathogenicity focused on host specificity. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2016, 82, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner-Hanks, T.; Nelson, R. Multiple disease resistance in plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2016, 54, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Hyde, K.D.; Taylor, P.W.J.; Weir, B.S.; Waller, J.M.; Abang, M.M.; Zhang, J.Z.; Yang, Y.L.; Phoulivong, S.; Liu, Z.Y.; et al. A polyphasic approach for studying Colletotrichum. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.; Pinnaka, A.K.; Shenoy, B.D. Resolving the Colletotrichum siamense species complex using ApMat marker. Fungal Divers. 2015, 71, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, P.F.; Bridge, P.D.; Monte, E. Linking the Past, Present, and Future of Colletotrichum Systematics. In Colletotrichum: Host specificity, Pathology, and Host-Pathogen Interaction; Prusky, D., Freeman, S., Dickman, M., Eds.; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2000; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Photita, W.; Taylor, P.W.J.; Ford, R.; Lumyong, P.; McKenzie, H.C.; Hyde, K.D. Morphological and molecular characterization of Colletotrichum species from herbaceous plants in Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2005, 18, 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Weir, B.S.; Damm, U.; Crous, P.W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, M.; Zhang, M.; Cai, L. Unravelling Colletotrichum species associated with Camellia: Employing ApMat and GS loci to resolve species in the C. gloeosporioides complex. Persoonia 2015, 35, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, B.S.; Johnston, P.R.; Damm, U. The Colletotrichum gloeosporioides species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 115–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Su, Y.-Y.; Cai, L. An optimized protocol of single spore isolation for fungi. Cryptogam. Mycol. 2013, 34, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, L.; Rojas, P.; Rojas, S.; Pardo-De la Hoz, C.J.; Mideros, M.F.; Danies, G.; Lopez-Kleine, L.; Jimenez, P.; Restrepo, S. Most Colletotrichum species associated with tree tomato (Solanum betaceum) and mango (Mangifera indica) crops are not host-specific. Plant Pathol. 2018, 67, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Snisky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G. Development of primer sets designed for use with PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous Ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1997, 7, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, M.D.; Rikkerink, E.H.; Solon, S.L.; Crowhurst, R.N. Cloning and molecular characterization of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-encoding gene and cDNA from the plant pathogenic fungus Glomerella cingulata. Gene 1992, 122, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroncelli, R.; Sarrocco, S.; Zapparata, A.; Tavarini, S.; Angelini, L.G.; Vannacci, G. Characterization and epidemiology of Colletotrichum acutatum sensu lato (C. chrysanthemi) causing Carthamus tinctorius anthracnose. Plant Pathol. 2015, 64, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Cai, L.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Yang, Y.L.; Zhang, J.Z.; Prihastuti, H. Colletotrichum: A catalogue of confusion. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schena, L.; Mosca, S.; Cacciola, S.O.; Faedda, R.; Sanzani, S.M.; Agosteo, G.E.; Sergeeva, V.; Magnano di San Lio, G. Species of the Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and C. boninense complexes associated with olive anthracnose. Plant Pathol. 2014, 63, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T.S.; Sijam, K.; Kadir, J.; Saud, H.M.; Awla, H.K.; Hata, E.M. First report of tomato anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum boninense in Malaysia. J. Plant Pathol. 2015, 97, 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, Y.Z.; Zhang, C.; Lin, D.; Liu, X.L. First report of Colletotrichum truncatum causing anthracnose of tomato in China. Dis. Notes 2014, 98, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, T.J.; Gupta, S.G.; Anandalakshmi, R. Detection of tomato anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum truncatum in India. Australas. Plant Dis. Notes 2017, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafana, R.T.; Ramdass, A.C.; Rampersad, S.N. First Report of Colletotrichum truncatum causing anthracnose in tomato fruit in Trinidad. Dis. Notes 2018, 102, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bincader, S.; Pongpisutta, R.; Rattanakreetakul, C. Diversity of Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose disease from Mango cv. Nam Dork Mai See Tong based on ISSR-PCR. Indian J. Agric. Res. 2022, 56, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva, D.D.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W.; Ades, P.K.; Nasruddin, A.; Mongkolporn, O.; Taylor, P.W. Identification, prevalence and pathogenicity of Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose of Capsicum annuum in Asia. IMA Fungus 2019, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Luo, C.-X.; Wu, H.-J.; Peng, B.; Kang, B.-S.; Liu, L.-M.; Zhang, M.; Gu, Q.-S. Colletotrichum species associated with anthracnose disease of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) in China. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhou, J.; Hu, M.; Liu, A.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C. Colletotrichum Spp. Diversity between leaf anthracnose and crown rot from the same strawberry plant. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 860694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Feng, W.; Yang, J.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Gong, D.; Hu, M. First report of anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum siamense on avocado fruits in China. Crop Prot. 2022, 155, 105922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardello, G.; Moral, J.; Strano, M.C.; Caruso, P.; Sciara, M.; Bella, P.; Sorrentino, G.; Di Silvestro, S. Characterization of Colletotrichum strains associated with olive anthracnose in Sicily. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2022, 61, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Esteva, M.C.; Soto-Castro, D.; Vásquez-López, A.; Tovar-Pedraza, J.M. First report of Colletotrichum siamense causing papaya anthracnose in Mexico. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 104, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.S.; Balasubramaniam, J.; Sani, S.F.; Alam, M.W.; Ismail, N.A.; Gleason, M.L.; Rosli, H. First report of Colletotrichum scovillei causing anthracnose on watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) in Malaysia. Dis. Notes 2022, 106, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, Y.W.; Tan, H.T.; Khaw, Y.S.; Li, S.-F.; Chong, K.P. First report of anthracnose on ‘Purple Dream’ Solanum melongenain Malaysia caused by Colletotrichum siamense. Plant Dis. 2022, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmodi, F.; Kadir, J.; Puteh, A. Genetic diversity and pathogenic variability of Colletotrichum truncatum causing anthracnose of pepper in Malaysia. J. Phytopathol. 2014, 162, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya, S.I.; Anuar, I.S.M.; Zakaria, L. Characterization and pathogenicity of Colletotrichum truncatum causing stem anthracnose of red-fleshed dragon fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus) in Malaysia. J. Phytopathol. 2015, 163, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, L.; Sahak, S.; Zakaria, M.; Salleh, B. Characterisation of Colletotrichum species associated with anthracnose of banana. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2009, 20, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zĭvković, S.; Stojanović, S.; Ivanović, Z.; Trkulja, N.; Dolovac, N.; Aleksić, G.; Jelica Balaž, J. Morphological and molecular identification of Colletotrichum acutatum from tomato fruit. Pestic. Phytomed. 2010, 25, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).