Abstract

Poxviruses are large dsDNA viruses that are regarded as good candidates for vaccine vectors. Because the members of the Poxviridae family encode numerous immunomodulatory proteins in their genomes, it is necessary to carry out certain modifications in poxviral candidates for vaccine vectors to improve the vaccine. Currently, several poxvirus-based vaccines targeted at viral infections are under development. One of the important aspects of the influence of poxviruses on the immune system is that they encode a large array of inhibitors of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), which is the key element of both innate and adaptive immunity. Importantly, the NF-κB transcription factor induces the mechanisms associated with adaptive immunological memory involving the activation of effector and memory T cells upon vaccination. Since poxviruses encode various NF-κB inhibitor proteins, before the use of poxviral vaccine vectors, modifications that influence NF-κB activation and consequently affect the immunogenicity of the vaccine should be carried out. This review focuses on NF-κB as an essential factor in the optimization of poxviral vaccines against viral infections.

1. Introduction

Poxviridae is a family of dsDNA viruses. It is divided into two subfamilies: Chordopoxvirinae, the viruses of vertebrates, and Entomopoxvirinae, the viruses of insects. The Chordopoxvirinae subfamily includes 18 genera: Avipoxvirus, Capripoxvirus, Centapoxvirus, Cervidopoxvirus, Crocodylidopoxvirus, Leporipoxvirus, Macropopoxvirus, Molluscipoxvirus, Mustelpoxvirus, Orthopoxvirus, Oryzopoxvirus, Parapoxvirus, Pteropopoxvirus, Salmonpoxvirus, Sciuripoxvirus, Suipoxvirus, Vespertilionpoxvirus, and Yatapoxvirus [1]. Poxviruses are represented by numerous human and animal pathogens. Among them, variola virus (VARV) orthopoxvirus, a human pathogen, is the causative agent of smallpox, a disease that had caused over 300 million deaths worldwide by the late 1970s before the global smallpox eradication program was completed. In the global smallpox eradication program, vaccinia virus (VACV), a zoonotic pathogen belonging to the Orthopoxvirus genus, was used [2,3]. Other members of the Poxviridae family, such as orf virus (ORFV) and goatpoxvirus (GTPV), which represent the Parapoxvirus and Capripoxvirus genera, respectively, may also serve as vaccines and are described in this review.

With the exception of parapoxviruses, poxvirus virions have a brick shape. The virions of parapoxviruses are cocoon-shaped. The virions of parapoxvirus and other members of the Poxviridae family have dimensions of 260 × 160 nm and 350 × 250 nm, respectively [4,5]. Depending on the number of membranes surrounding the virion, two infectious forms of poxviruses are observed. Mature virus (MV), which contains a tubular nucleocapsid surrounded by a biconcave core wall and proteinaceous lateral bodies, is enclosed by a single proteolipid membrane bilayer. In turn, extracellular virus (EV) is composed of MV surrounded by an additional membrane derived from an early endosome or the trans-Golgi. This membrane is acquired by the virus during exocytosis [6].

The genome of poxviruses ranges from 130 to 300 kbp. The largest genome can be observed among avipoxviruses, whereas the smallest can be observed in parapoxviruses [4,5]. The genes encoding the open reading frames (ORFs) linked to virus replication, such as those essential for the nucleic acid synthesis and structural components of the virion, are located within the conserved central region of the poxvirus genome. These genes encode DNA polymerase, DNA ligase, DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, as well as the enzymes involved in capping and polyadenylation of mRNAs, and thymidine kinase (TK). The genes flanking the central region of the poxvirus genome encode numerous proteins that determine the host range and virulence and are responsible for modulating the immune response of the host. The two DNA strands of poxvirus genome are joined together by covalent linkage at both ends, where inverted terminal repetitions (ITRs), which are long tandem repeated nucleotide sequences flanking the genome, are present [5].

The ORFs present at the terminal poxviral genome mainly target the innate immune response mechanisms of the host via modulation of the antiviral signaling pathways. One of the innate antiviral pathways modulated by poxviruses is the stimulator of interferon (IFN) genes (STING) pathway that senses the viral dsDNA. Cytosolic sensors of viral DNA, namely cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS), DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), and IFN-γ-inducible protein 16 (IFI16), activate the STING adaptor protein, and this protein, in turn, activates tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor (TNFR)-associated factor (TRAF) nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) (TANK)-binding kinase 1 (TBK1)–IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and inhibitor κB (IκB) kinase (IKK)–NF-κB pathways which are crucial for antiviral response. These pathways induce the synthesis of immune defense molecules, such as proinflammatory cytokines and IFNs. It has been demonstrated that VACV encodes C4 and C16 proteins which may antagonize DNA–PK and thus impair cytokine response and IRF3 inhibition. C16, which acts upstream of STING, inhibits its activation. In addition, B2 VACV has been found to target cGMP. C4 may also inhibit NF-κB activation. Importantly, the inhibition of NF-κB by poxviruses may be multidirectional and occur downstream of STING activation [7,8].

Deletion of B2 or the antagonist of VACV DNA-PK could be beneficial for vaccine development. Thus, studies on DNA sensing pathways may shed light on the potential therapeutic strategies. Knowing that certain VACV proteins, such as K1 and A55, prevent the nuclear translocation of NF-κB or NF-κB heterodimer processing, it should be considered that they may also inhibit STING-induced NF-κB activation [7]. Taken together, studying the modification of NF-κB and other related cellular signaling pathways by VACV and other poxviruses may help in finding novel options for the modification of vaccine vectors.

2. Poxviruses as Candidates for Vaccine Vector Design

Poxviruses are transmitted via mucosal, respiratory, and parenteral routes [9]. Although these viruses may enter various cell types, only the cells supporting their full replication cycle can be considered as permissive for the infection. The genomes of many poxviruses share similar sequences; however, during their evolution, the loss or truncation of certain genes, which confer the full replication cycle of the poxviruses, influenced their host range [9,10,11].

Poxviruses serve as good vaccine vectors due to the fact that a large sequence of up to 25 kbp encoding viral, bacterial, parasitic, and tumor antigens can be introduced into their genomes. These heterologous antigens are aimed at triggering antibody response and inducing cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) to confer immunity. As mentioned earlier, poxviral vectors can infect different types of cells [12,13,14]. The lifecycle of poxviruses takes place in the cell cytoplasm, within the cytoplasmic compartments called viral factories. Poxviral pathogens encode factors needed for DNA replication, transcription, mRNA processing, and cytoplasmic redox systems. However, like other viruses, poxviruses are fully dependent on host ribosomes, which are required for mRNA translation [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

One of the advantages that make poxviruses good vaccine vectors is that the cytoplasmic replication cycle of these vectors eliminates the risk of integration into the host genome and persistence within the host. Importantly, poxviral vaccines are easy to store, especially when freeze-dried. The thermostability of these vaccines can also be ensured by using sugar-glass technology. Additionally, the cost of poxviral vaccines is low and their administration is needle-free [12,13,14].

Although poxviruses are regarded as promising vaccine tools, certain challenges limit the design of poxviral vaccines. When using VACV and other poxvirus-based vaccines, it is desirable to achieve enhanced immunogenicity and/or virus attenuation. This is particularly important for improving the safety profile of the vaccine. Due to the abundance of immunomodulatory genes and cellular targets of the poxviruses, which remain unrevealed, there are still many opportunities for virus modification in order to improve the vaccine efficacy by inducing stronger immunological memory. In addition, reduction of dosage and administration regimes would be beneficial as well [7]. One of the strategies employing poxvirus vaccines is prime-boost vaccination, in which poxviral vectors that enhance T cell responses as boosters are combined with other vectors. On the other hand, when used as primers with protein and adjuvant, poxviruses improve the B cell responses. Furthermore, the optimization of the antigen expression is based on mosaic immunogen sequences [13].

When modifying poxviral vaccine vectors, the immunomodulatory genes should be removed in order to enhance immunogenicity [13]. Poxviruses, which express a wide range of host response modifiers influencing cellular signaling pathways involved in immunity and inflammation, share multiple mechanisms of host evasion. Since Poxviridae family members encode a number of cellular signaling inhibitors, this review describes the influence of poxvirus-based vaccines on the NF-κB transcription factor [9]. Several data indicate the importance of NF-κB in the development of poxvirus-derived vaccines. These are based on both veterinary and human antiviral vaccines. Therefore, in this review, we focus on the benefits of certain modifications of poxviral vaccine vectors and how these modifications can affect NF-κB signaling in different cells and hosts and the possible mechanisms of immune response modulation that can be shared by individual poxvirus genera. We describe the VACV-, ORFV-, and GTPV-based vaccines, which can be used against viral infections.

4. NF-κB Signaling

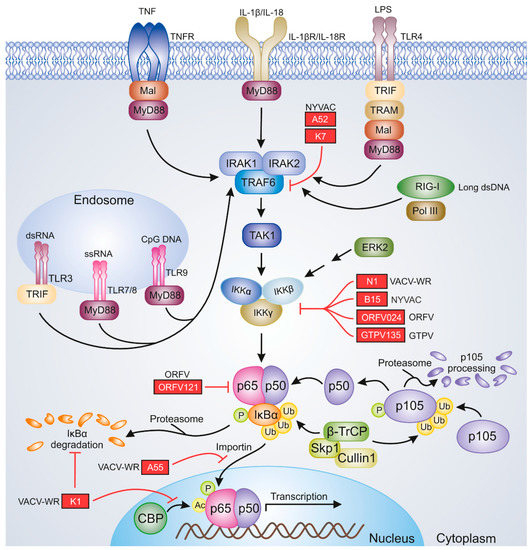

One of the key factors involved in the proper induction of antiviral immunity is NF-κB. It constitutes a family of dimeric transcription factors, which regulate the expression of numerous genes involved in the cell cycle, apoptosis, and immunity. The NF-κB family consists of five proteins: RelA/p65, RelB, c-Rel, NFκB1 p105/p50, and NFκB2 p100/p52. The NF-κB dimer that is most commonly detected in the cytoplasm of unstimulated cells is composed of RelA and p50 subunits [50]. The RelA/p50 heterodimer remains in the cytoplasm due to the activity of IκBα, which masks the nuclear localization sequences (NLSs) of NF-κB [51]. The classical NF-κB signaling pathway is induced by proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-18, and TNF-α and various ligands of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which are represented by retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I) and Toll-like receptors (TLRs). In the NF-κB signaling cascade, the cellular receptors cooperate with adapter molecules and induce the cellular pathways that activate the transcriptionally active dimers [52]. Upon the stimulation of NF-κB signaling, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-activated kinase 1 (ΤAΚ1) activates IKK, the IKKβ subunit of which triggers IκBα phosphorylation at Ser32 and Ser36. This event results in the recognition of IκBα by the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex composed of β-transducin repeat-containing proteins: S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 (Skp1)–Cullin 1–F-box (SCFβ−TrCP). Conjugation of phosphorylated IκBα with K48-linked polyubiquitin chains of Lys 48 of ubiquitin by SCFβ−TrCP results in 26S proteasome-mediated IκBα degradation and the release of RelA/p50 dimers. These dimers translocate to the nucleus, where they bind DNA and initiate the transcription of target genes. E3 ubiquitin ligase complex is also involved in p105 proteasomal processing to p50 [50,53,54] (Figure 1). On the other hand, the noncanonical NF-κB signaling triggered by the members of the TNF superfamily leads to the activation of NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK), which then activates IKKα. IKKα, in turn, phosphorylates the C-terminal portion of p100 precursor protein, which retains RelB in the cytoplasm due to its IκB activity. Following the phosphorylation of p100 at Ser866 and Ser870, IκB-like C-terminal portions of this protein are ubiquitinated, leading to the generation of a p52 active NF-κB subunit. RelB/p52 dimers translocate to the nucleus and initiate the transcription of target genes [55]. In general, the canonical NF-κB signaling is responsible for the regulation of innate immunity [56], whereas the noncanonical NF-κB activation pathway regulates the adaptive immune responses. However, there exist regulatory mechanisms for these two signaling pathways as well as for the crosstalk between them [55,57]. The modulation of NF-κB signaling is attributed to viral pathogens, one excellent example of which is the viruses belonging to the Poxviridae family encoding multiple immunomodulatory proteins; these proteins affect the components of NF-κB signaling and therefore disrupt the antiviral innate response [52,58]. Selected NF-κB inhibitors of VACV, ORFV, and GTPV, which may be relevant to the efficacy of poxviral vaccines, are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Poxviral inhibitors of NF-κB signaling. The image represents selected viral proteins that block NF-κB activation. The proteins shown in the figure are described in the text. Black pointing arrows indicate activation; red blunt arrows indicate inhibition. Ac, acetyl group; CBP, CREB-binding protein; CpG, cytosine–guanine dinucleotide; ERK2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2; GTPV, goatpox virus; IKKα, IκB kinase α; IKKβ, IκB kinase β; IKKγ, IκB kinase γ; IL-1β, interleukin 1β; IL-18, interleukin 18; IL-18R, IL-18 receptor; IL-1βR, IL-1β receptor; IRAK1, IL-1R-associated kinase 1; IRAK2, IL-1R-associated kinase 2; IκBα, inhibitor κBα; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; Mal, MyD88-adapter-like; MyD88, myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88; NYVAC, vaccinia virus New York strain; ORFV, orf virus; P, phosphate group; Pol III, polymerase III; RIG-I, retinoic acid-inducible gene; Skp1, S-phase kinase-associated protein 1; TAK1, transforming growth factor (TGF)β-activated kinase 1; TLR3, Toll-like receptor 3; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; TLR7, Toll-like receptor 7; TLR8, Toll-like receptor 8; TLR9, Toll-like receptor 9; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFR, TNF receptor; TRAF6, TNFR-associated factor 6; TRAM, TRIF-related adapter molecule; TRIF, Toll-IL-1R-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β; Ub, Ub-ubiquitin moieties; VACV-WR, vaccinia virus Western Reserve strain; β-TrCP, β-transducin repeat-containing protein.

6. Conclusions

Generation of effective immune response and immunological memory, as well as safety, is the main concern in vaccine development. When employing virus-based vaccines, it is necessary to ensure both the complete replication cycle of the virus and proper induction of immunological memory for determining the vaccine efficiency. The loss of viral immunomodulatory proteins may affect these parameters, thus influencing efficiency. Since poxviruses modulate the activation of immune cells by affecting the NF-κB-mediated apoptosis regulation, inflammation, and immunological memory, discovering new mechanisms of NF-κB inhibition and cellular targets of poxviruses may help modify vaccine candidates to improve the efficacy of poxvirus-based vaccines and the immunological memory generated by them.

Author Contributions

J.S. contributed to conceptualization and writing (original draft preparation, review, and editing). L.S.-D. contributed to conceptualization and writing (figure preparation, review, and editing). All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by National Science Centre, Poland, grant number UMO-2015/19/D/NZ6/02873.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| VARV | variola virus |

| VACV | vaccinia virus |

| ORFV | orf virus |

| GTPV | goatpox virus |

| MV | mature virus |

| EV | extracellular virus |

| ORF | open reading frame |

| TK | thymidine kinase |

| ITR | inverted terminal repetition |

| IFN | interferon |

| STING | stimulator of IFN genes |

| cGAS | cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| DNA-PK | DNA-dependent protein kinase |

| IFI16 | IFN-γ-inducible protein 16 |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| TNFR | TNF receptor |

| TRAF | TNFR-associated factor |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| TANK | TRAF family member-associated NF-κB activator |

| TBK1 | TANK-binding kinase |

| IRF3 | IFN regulatory factor 3 |

| IκB | inhibitor κB |

| IKK | IκB kinase |

| CTL | cytotoxic T lymphocyte |

| NYCBH | New York City Board of Health |

| VACV-COP | VACV Copenhagen strain |

| cESC | chicken embryonic stem cell |

| MVA | modified VACV Ankara |

| MVA-BN | modified VACV Ankara - Bavarian Nordic |

| MPXV | monkeypox virus |

| CPXV | cowpox virus |

| CMLV | camelpox virus |

| BPSV | bovine papular stomatitis virus |

| PCPV | pseudocowpox virus |

| YMTV | Yaba monkey tumor virus |

| TPV | tanapox virus |

| RABV | rabies virus |

| V-RG | RABV glycoprotein gene |

| CHIKV | chikungunya virus |

| SCV | Sementis Copenhagen Vector |

| Ad | adenovirus |

| Ad26 | Ad serotype 26 |

| Ad26.HPV16 | Ad26 HPV16 vaccine |

| Ad26.HPV18 | Ad26 HPV18 vaccine |

| Ad26.Mos.HIV | Ad26-mosaic-HIV vaccine |

| Ad26.Mos4.HIV | Ad26-mosaic 4-HIV vaccine |

| Ad26.ZEBOV | human Ad26 expressing the Ebola virus Mayinga variant gp |

| AIDS | acquired immune deficiency syndrome |

| ATI | analytical treatment interruption |

| bNAbs | broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies |

| ChAd | Chimpanzee adenovirus |

| ChAd155 | ChAd serotype 155 |

| ChAd155-hIi-HBV | ChAd HBV vaccine |

| ChAd3-hliNSmut | ChAd3 encoding NSmut linked to hli |

| ChAdOx1 | replication-deficient ChAd vector derived from isolate Y25 |

| ChAdOx1.HTI | ChAdOx1 expressing HTI |

| ChAdV63 | ChAd serotype 63 |

| ChAdV63.HIVconsv | ChAdV63 expressing HIVconsv |

| CMV | cytomegalovirus |

| DNA.HTI | plasmid DNA expressing HTI |

| gp | glycoprotein |

| gp140 DP | gp140 drug product |

| GS-9620 | vesatolimod |

| HBc | hepatitis B core antigen |

| HBc-HBs/AS01B-4 | HBV vaccine |

| HBs | hepatitis B surface antigen |

| HBV | hepatitis B virus |

| HCT | hematopoietic cell transplantation |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| HIV-1 | HIV type 1 |

| HIVcons | HIV conserved antigenic regions |

| hli | human invariant chain |

| HPV | human papillomavirus |

| HPV16/18 | human papillomavirus type 16/18 |

| HTI | HIVACAT T cell immunogen |

| IL-12 | interleukin-12 |

| M1 | matrix protein |

| MenACWY | meningococcal ACWY-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine |

| MVA.HIVconsv | MVA expressing HIVconsv |

| MVA.HPV16/18 | MVA HPV16/18 vaccine |

| MVA.HTI | MVA expressing HTI |

| MVA.tHIVconsv3 | MVA-based T-cell vaccine expressing novel HIV-1 immunogens |

| MVA.tHIVconsv4 | MVA-based T-cell vaccine expressing novel HIV-1 immunogens |

| MVA62B | MVA component—encoding HIV-1 Gag, protease, reverse transcriptase, and envelope gp160 |

| MVA-BN-Filo | MVA-BN-Filo vector |

| MVA-HBV | MVA HBV vaccine |

| MVA-hliNSmut | MVA encoding NSmut linked to hli |

| MVA-mosaic | MVA mosaic HIV vaccine |

| MVA-NP + M1 | MVA encoding NP and M1 |

| NP | nucleoprotein |

| NSmut | HCV nonstructural immunogen |

| p24CE + p55gag | DNA vaccines expressing p24CE and p55gag immunogens |

| rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP | recombinant VSV–Zaire Ebola virus gp |

| TLR9 | Toll-like receptor 9 |

| VRC07, 10-1074 | anti-HIV-1 bNAbs |

| VSV | vesicular stomatitis virus |

| NLS | nuclear localization sequence |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1β |

| IL-18 | interleukin-18 |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| PRR | pattern recognition receptor |

| RIG-I | retinoic acid-inducible gene-I |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-β |

| TAK1 | TGF-β-activated kinase 1 |

| Skp1 | S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 |

| SCF | Skp1-Cul1-F-box |

| β-TrCP | β-transducin repeat-containing protein |

| NIK | NF-κB-inducing kinase |

| Ac | acetyl group |

| CBP | CREB-binding protein |

| CpG | cytosine–guanine dinucleotide |

| ERK2 | extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 |

| IKKα | IκB kinase α |

| IKKβ | IκB kinase β |

| IKKγ | IκB kinase γ |

| IL-18R | IL-18 receptor |

| IL-1βR | IL-1β receptor |

| IRAK1 | IL-1R-associated kinase 1 |

| IRAK2 | IL-1R-associated kinase 2 |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| Mal | MyD88-adapter-like |

| MyD88 | myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 |

| P | phosphate group |

| Pol III | polymerase III |

| TLR3 | Toll-like receptor 3 |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TLR7 | Toll-like receptor 7 |

| TLR8 | Toll-like receptor 8 |

| TRAM | TRIF-related adapter molecule |

| TRIF | Toll-IL-1R-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β |

| Ub | Ub-ubiquitin moieties |

| VACV-WR | VACV Western Reserve strain |

| β-TrCP | β-transducin repeat-containing protein |

| CVA | chorioallantois VACV Ankara strain |

| IL-1BP | IL-1 binding protein |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| VGF | VACV growth factor |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| HEK 293T | human embryonic kidney 293 cells transformed with large T antigen |

| CHO | Chinese hamster ovary cells |

| RK13 | rabbit kidney 13 cells |

| CPXV-BR | CPXV Brighton Red strain |

| ANK | ankyrin repeat |

| MYXV | myxoma virus |

| MEFs | mouse embryonic fibroblasts |

| PKR | protein kinase R |

| MEK | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase |

| APC | antigen presenting cell |

| ATF3 | activating transcription factor 3 |

| MDDC | monocyte-derived dendritic cell |

| gp120 | glycoprotein 120 |

| GPN | Gag-Pol-Nef |

| MHCII | major histocompatibility complex class II |

| NK | natural killer cell |

| BBK | BTB-BACK-Kelch |

| PRV | pseudorabies virus |

| RHDV | rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus |

| D1701-V-RabG | recombinant D1701 ORFV strain expressing RABV glycoprotein |

| D1701-V-HAh5n | recombinant D1701 ORFV strain expressing H5 hemagglutinin |

| VIR | viral IFN resistance |

| PEDV | porcine epidemic diarrhea virus |

| S | spike protein |

| ORFV-PEDV-S | |

| ORFVΔ024RABV-G | ORFV Δ024 mutant expressing RABV glycoprotein |

| ORFVΔ121RABV-G | ORFV Δ121 mutant expressing RABV glycoprotein |

| PPRV | peste des petis ruminants virus |

References

- Virus Taxonomy: 2019 Release. Available online: https://talk.ictvonline.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Babkin, I.V.; Babkina, I.N. The origin of the variola virus. Viruses 2015, 7, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shchelkunova, G.A.; Shchelkunov, S.N. 40 Years without Smallpox. Acta Naturae 2017, 9, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buller, R.M.L. Poxviruses. In Infectious Diseases, 4th ed.; Cohen, J., Powderly, W.G., Opal, S.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1452–1457.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, C.J.; Howard, C.R.; Murphy, F.A. (Eds.) Poxviruses. In Fenner and White’s Medical Virology, 5th ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condit, R.C.; Moussatche, N. The vaccinia virus E6 protein influences virion protein localization during virus assembly. Virology 2015, 482, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Jesr, M.; Teir, M.; Maluquer de Motes, C. Vaccinia virus activation and antagonism of cytosolic DNA sensing. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 568412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, L. DNA-sensing antiviral innate immunity in poxvirus infection. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, M.G.; Guagliardo, S.A.J.; Nakazawa, Y.J.; Doty, J.B.; Mauldin, M.R. Understanding orthopoxvirus host range and evolution: From the enigmatic to the usual suspects. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2018, 28, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, G. Poxvirus tropism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, S.L.; Peng, C.; McFadden, G.; Rothenburg, S. Poxviruses and the evolution of host range and virulence. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 21, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, M.I.; Okoli, A.S.; Diaz, D.; Offor, C.; Oludotun, T.G.; Tryland, M.; Bøhn, T.; Moens, U. Hazard characterization of modified vaccinia virus Ankara vector: What are the knowledge gaps? Viruses 2017, 9, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arriaza, J.; Esteban, M. Enhancing poxvirus vectors vaccine immunogenicity. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014, 10, 2235–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prow, N.A.; Jimenez Martinez, R.; Hayball, J.D.; Howley, P.M.; Suhrbier, A. Poxvirus-based vector systems and the potential for multi-valent and multi-pathogen vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2018, 17, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, S.R.; Wilck, M.B.; Dominguez, D.J.; Zablowsky, E.; Bajimaya, S.; Gagne, L.S.; Verrill, K.A.; Kleinjan, J.A.; Patel, A.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia Ankara in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, B. Poxviridae: The viruses and their replication. In Fields Virology, 5th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Griffin, D.E., Lamb, R.A., Martin, M.A., Roizman, B., Straus, S.E., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 2905–2946. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, K.; Mohamed, M.R.; Zhang, L.; Villa, N.Y.; Werden, S.J.; Liu, J.; McFadden, G. Poxvirus proteomics and virus-host protein interactions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009, 73, 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.L.; Talbot-Cooper, C.; Lu, Y. How does vaccinia virus interfere with interferon? Adv. Virus Res. 2018, 100, 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, N.; DiGiuseppe, S.; Walsh, D. Translational control during poxvirus infection. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2019, 10, e1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.; Knébel, S.; Schmidt, F.I.; Crouse, J.; Burkard, C.; Helenius, A. Vaccinia virus strains use distinct forms of macropinocytosis for host-cell entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9346–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, M.R.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Lefkowitz, E.J. Poxvirus protein evolution: Family wide assessment of possible horizontal gene transfer events. Virus Res. 2009, 144, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberte, J.P.; Moss, B. Lipid membranes in poxvirus replication. Viruses 2010, 2, 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.I.; Bleck, C.K.; Mercer, J. Poxvirus host cell entry. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, B. Poxvirus DNA replication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a010199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cooper, T.; Howley, P.M.; Hayball, J.D. From crescent to mature virion: Vaccinia virus assembly and maturation. Viruses 2014, 6, 3787–3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giotis, E.S.; Montillet, G.; Pain, B.; Skinner, M.A. Chicken embryonic-stem cells are permissive to poxvirus recombinant vaccine vectors. Genes 2019, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.L.; Irausquin, S.; Friedman, R. The evolutionary biology of poxviruses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2010, 10, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittman, P.R.; Hahn, M.; Lee, H.S.; Koca, C.; Samy, N.; Schmidt, D.; Hornung, J.; Weidenthaler, H.; Heery, C.R.; Meyer, T.P.H.; et al. Phase 3 efficacy trial of modified vaccinia Ankara as a vaccine against smallpox. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, E.A.; Kennedy, R.B.; Poland, G.A. Defending against smallpox: A focus on vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2016, 15, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, L.P.; Irwin, C.R.; Hu, W.G.; Evans, D.H. Vaccinia-based vaccines to biothreat and emerging viruses. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2018, 34, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchelkunov, S.N. An increasing danger of zoonotic orthopoxvirus infections. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarnaz, J.D.; Torres, A.A.; Smith, G.L. Modulating vaccinia virus immunomodulators to improve immunological memory. Viruses 2018, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, E.M.; Rao, V.B. A systematic review of the epidemiology of human monkeypox outbreaks and implications for outbreak strategy. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinka-Ogunleye, A.; Aruna, O.; Dalhat, M.; Ogoina, D.; McCollum, A.; Disu, Y.; Mamadu, I.; Akinpelu, A.; Ahmad, A.; Burga, J.; et al. Outbreak of human monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017–18: A clinical and epidemiological report. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis, F.L.; Vinhote, W.M.; Barbosa, J.D.; de Oliveira, C.H.; de Oliveira, C.M.; Campos, K.F.; Silva, N.S.; Trindade Gde, S.; Abrahão, J.S.; Kroon, E.G. Reemergence of vaccinia virus during zoonotic outbreak, Pará State, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 2017–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahão, J.S.; Campos, R.K.; Trindade Gde, S.; Guimarães da Fonseca, F.; Ferreira, P.C.; Kroon, E.G. Outbreak of severe zoonotic vaccinia virus infection, Southeastern Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, M.G.; Bacchiega, T.S.; Appolinário, C.M.; Vicente, A.F.; Mioni, M.S.R.; Ribeiro, B.L.D.; Fonseca, C.R.S.; Pelícia, V.C.; Ferreira, F.; Oliveira, G.P.; et al. Vaccinia virus in blood samples of humans, domestic and wild mammals in Brazil. Viruses 2018, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antwerpen, M.H.; Georgi, E.; Nikolic, A.; Zoeller, G.; Wohlsein, P.; Baumgärtner, W.; Peyrefitte, C.; Charrel, R.; Meyer, H. Use of Next Generation Sequencing to study two cowpox virus outbreaks. PeerJ. 2019, 7, e6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalafalla, A.I.; Abdelazim, F. Human and dromedary camel infection with camelpox virus in Eastern Sudan. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017, 17, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, G.P.; Rodrigues, R.A.L.; Lima, M.T.; Drumond, B.P.; Abrahão, J.S. Poxvirus host range genes and virus-host spectrum: A critical review. Viruses 2017, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prow, N.A.; Liu, L.; McCarthy, M.K.; Walters, K.; Kalkeri, R.; Geiger, J.; Koide, F.; Cooper, T.H.; Eldi, P.; Nakayama, E.; et al. The vaccinia virus based Sementis Copenhagen Vector vaccine against Zika and chikungunya is immunogenic in non-human primates. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, J.C.; Jing, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.H.; Jin, N.Y.; Lu, H.J. Construction and immunogenicity of recombinant vaccinia virus vaccine against Japanese encephalitis and chikungunya viruses infection in mice. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2020, 20, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julander, J.G.; Testori, M.; Cheminay, C.; Volkmann, A. Immunogenicity and protection after vaccination with a modified vaccinia virus Ankara-vectored yellow fever vaccine in the hamster model. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanzini, D.; Del Médico-Zajac, M.P.; Calamante, G. Development of recombinant canarypox viruses expressing immunogens. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1581, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, D.G.; Trivedi, S.; Jackson, R.J.; Ranasinghe, C. Recombinant fowlpox virus vector-based vaccines: Expression kinetics, dissemination and safety profile following intranasal delivery. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W. Construction of recombinant capripoxviruses as vaccine vectors for delivering foreign antigens: Methodology and application. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 65, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reemers, S.; Peeters, L.; van Schijndel, J.; Bruton, B.; Sutton, D.; van der Waart, L.; van de Zande, S. Novel trivalent vectored vaccine for control of myxomatosis and disease caused by classical and a new genotype of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus. Vaccines 2020, 8, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reguzova, A.; Ghosh, M.; Müller, M.; Rziha, H.J.; Amann, R. Orf virus-based vaccine vector D1701-V induces strong CD8+ T cell response against the transgene but not against ORFV-derived epitopes. Vaccines 2020, 8, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.J.; Lin, H.X. Recombinant swinepox virus for veterinary vaccine development. In Vaccine Technologies for Veterinary Viral Diseases. Methods in Molecular Biology; Brun, A., Ed.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1349, pp. 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lenardo, M.J.; Baltimore, D. 30 Years of NF-κB: A blossoming of relevance to human pathobiology. Cell 2017, 168, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, A.A.; Ruben, S.M.; Scheinman, R.I.; Haskill, S.; Rosen, C.A.; Baldwin, A.S., Jr. IκB interacts with the nuclear localization sequences of the subunits of NF-κB: A mechanism for cytoplasmic retention. Genes Dev. 1992, 6, 1899–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, G.; Bowie, A.G. Innate immune activation of NFκB and its antagonism by poxviruses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014, 25, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traenckner, E.B.; Pahl, H.L.; Henkel, T.; Schmidt, K.N.; Wilk, S.; Baeuerle, P.A. Phosphorylation of human IκB-α on serines 32 and 36 controls IκB-α proteolysis and NF-κB activation in response to diverse stimuli. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 2876–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.E.; Mitxitorena, I.; Carmody, R.J. The ubiquitination of NF-κB subunits in the control of transcription. Cells 2016, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.C. The non-canonical NF-κB pathway in immunity and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.M.; Remouchamps, C.; McCorkell, K.A.; Solt, L.A.; Dejardin, E.; Orange, J.S.; May, M.J. Noncanonical NF-κB signaling is limited by classical NF-κB activity. Sci. Signal. 2014, 7, ra13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mohamed, M.R.; McFadden, G. NFκB inhibitors: Strategies from poxviruses. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 3125–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, M.T.; Oliveira, G.P.; Afonso, J.; Souto, R.; de Mendonça, C.L.; Dantas, A.; Abrahao, J.S.; Kroon, E.G. An update on the known host range of the Brazilian vaccinia virus: An outbreak in buffalo calves. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.C.; Moreira-Silva, E.A.; Gomes, J.D.A.S.; Fonseca, F.G.; Correa-Oliveira, R. Clinical signs, diagnosis, and case reports of Vaccinia virus infections. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 14, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisinger-Henschel, C.; Schmidt, M.; Lukassen, S.; Linke, B.; Krause, L.; Konietzny, S.; Goesmann, A.; Howley, P.; Chaplin, P.; Suter, M.; et al. Genomic sequence of chorioallantois vaccinia virus Ankara, the ancestor of modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 3249–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Sonnenburg, F.; Perona, P.; Darsow, U.; Ring, J.; von Krempelhuber, A.; Vollmar, J.; Roesch, S.; Baedeker, N.; Kollaritsch, H.; Chaplin, P. Safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia Ankara as a smallpox vaccine in people with atopic dermatitis. Vaccine 2014, 32, 5696–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitzmann-Roth, E.M.; von Sonnenburg, F.; de la Motte, S.; Arndtz-Wiedemann, N.; von Krempelhuber, A.; Uebler, N.; Vollmar, J.; Virgin, G.; Chaplin, P. Cardiac safety of Modified Vaccinia Ankara for vaccination against smallpox in a young, healthy study population. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, E.T.; Stapleton, J.; Frank, I.; Hassler, S.; Goepfert, P.A.; Barker, D.; Wagner, E.; von Krempelhuber, A.; Virgin, G.; Meyer, T.P.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic smallpox vaccine in vaccinia-naive and experienced human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals: An open-label, controlled clinical phase II trial. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2015, 2, ofv040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothe, B.; Climent, N.; Plana, M.; Rosàs, M.; Jiménez, J.L.; Muñoz-Fernández, M.Á.; Puertas, M.C.; Carrillo, J.; Gonzalez, N.; León, A.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a modified vaccinia Ankara-based HIV-1 vaccine (MVA-B) in HIV-1-infected patients alone or in combination with a drug to reactivate latent HIV-1. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1833–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.A.; Frey, S.E.; El Sahly, H.M.; Mulligan, M.J.; Winokur, P.L.; Kotloff, K.L.; Campbell, J.D.; Atmar, R.L.; Graham, I.; Anderson, E.J.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine using three immunization schedules and two modes of delivery: A randomized clinical non-inferiority trial. Vaccine 2017, 35, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryerson, M.R.; Shisler, J.L. Characterizing the effects of insertion of a 5.2 kb region of a VACV genome, which contains known immune evasion genes, on MVA immunogenicity. Virus Res. 2018, 246, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volz, A.; Sutter, G. Modified vaccinia virus Ankara: History, value in basic research, and current perspectives for vaccine development. Adv. Virus Res. 2017, 97, 187–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, L.E.; Fahy, A.S.; Chen, R.A.; Smith, G.L. Mutations in modified virus Ankara protein 183 render it a non-functional counterpart of B14, an inhibitor of nuclear factor κB activation. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 2216–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.; Shisler, J.L. Early viral protein synthesis is necessary for NF-κB activation in modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA)-infected 293 T fibroblast cells. Virology 2009, 390, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martin, S.; Harris, D.T.; Shisler, J. The C11R gene, which encodes the vaccinia virus growth factor, is partially responsible for MVA-induced NF-κB and ERK2 activation. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 9629–9639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, H.E.; Ray, C.A.; Oie, K.L.; Pollara, J.J.; Petty, I.T.; Sadler, A.J.; Williams, B.R.; Pickup, D.J. Modified vaccinia virus Ankara can activate NF-κB transcription factors through a double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR)-dependent pathway during the early phase of virus replication. Virology 2009, 391, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.J.; Hsiao, J.C.; Sonnberg, S.; Chiang, C.T.; Yang, M.H.; Tzou, D.L.; Mercer, A.A.; Chang, W. Poxvirus host range protein CP77 contains an F-box-like domain that is necessary to suppress NF-κB activation by tumor necrosis factor α but is independent of its host range function. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 4140–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Z.; Nagampalli, R.S.K.; Fatima, M.T.; Ashraf, G.M. New paradigm in ankyrin repeats: Beyond protein-protein interaction module. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M.H.; Squire, C.J.; Mercer, A.A. Poxviral ankyrin proteins. Viruses 2015, 7, 709–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo Cruz, A.G.; Shisler, J.L. Vaccinia virus K1 ankyrin repeat protein inhibits NF-κB activation by preventing RelA acetylation. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camus-Bouclainville, C.; Fiette, L.; Bouchiha, S.; Pignolet, B.; Counor, D.; Filipe, C.; Gelfi, J.; Messud-Petit, F. A virulence factor of myxoma virus colocalizes with NF-κB in the nucleus and interferes with inflammation. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 2510–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Meng, X.; Xiang, Y.; Deng, J. Structure function studies of vaccinia virus host range protein K1 reveal a novel functional surface for ankyrin repeat proteins. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3331–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shisler, J.L.; Jin, X.L. The vaccinia virus K1L gene product inhibits host NF-κB activation by preventing IκBα degradation. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 3553–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryerson, M.R.; Richards, M.M.; Kvansakul, M.; Hawkins, C.J.; Shisler, J.L. Vaccinia virus encodes a novel inhibitor of apoptosis that associates with the apoptosome. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01385-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, S.; López-Fernández, L.A.; Pascual-Montano, A.; Nájera, J.L.; Zaballos, A.; Esteban, M. Host response to the attenuated poxvirus vector NYVAC: Upregulation of apoptotic genes and NF-κB-responsive genes in infected HeLa cells. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, S.; Nájera, J.L.; González, J.M.; López-Fernández, L.A.; Climent, N.; Gatell, J.M.; Gallart, T.; Esteban, M. Distinct gene expression profiling after infection of immature human monocyte-derived dendritic cells by the attenuated poxvirus vectors MVA and NYVAC. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 8707–8721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pilato, M.; Mejías-Pérez, E.; Zonca, M.; Perdiguero, B.; Gómez, C.E.; Trakala, M.; Nieto, J.; Nájera, J.L.; Sorzano, C.O.; Combadière, C.; et al. NFκB activation by modified vaccinia virus as a novel strategy to enhance neutrophil migration and HIV-specific T-cell responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E1333–E1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pilato, M.; Mejías-Pérez, E.; Sorzano, C.O.S.; Esteban, M. Distinct roles of vaccinia virus NF-κB inhibitor proteins A52, B15, and K7 in the immune response. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00575-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, R.P.; Ren, H.; Ferguson, B.J.; Smith, G.L. Increased attenuation but decreased immunogenicity by deletion of multiple vaccinia virus immunomodulators. Vaccine 2016, 34, 4827–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluquer de Motes, C.; Cooray, S.; Ren, H.; Almeida, G.M.; McGourty, K.; Bahar, M.W.; Stuart, D.I.; Grimes, J.M.; Graham, S.C.; Smith, G.L. Inhibition of apoptosis and NF-κB activation by vaccinia protein N1 occur via distinct binding surfaces and make different contributions to virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Ferguson, B.J.; Maluquer de Motes, C.; Sumner, R.P.; Harman, L.E.; Smith, G.L. Enhancement of CD8(+) T-cell memory by removal of a vaccinia virus nuclear factor-κB inhibitor. Immunology 2015, 145, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo Cruz, A.G.; Han, A.; Roy, E.J.; Guzmán, A.B.; Miller, R.J.; Driskell, E.A.; O’Brien, W.D., Jr.; Shisler, J.L. Deletion of the K1L gene results in a vaccinia virus that is less pathogenic due to muted innate immune responses, yet still elicits protective immunity. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00542-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallett, M.A.; Ren, H.; Zhang, R.Y.; Scutts, S.R.; Gonzalez, L.; Zhu, Z.; Maluquer de Motes, C.; Smith, G.L. Vaccinia Virus BBK E3 ligase adaptor A55 targets importin-dependent NF-κB activation and inhibits CD8+ T-cell memory. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00051-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, R.A.; Cargnelutti, J.F.; Schild, C.O.; Flores, E.F.; Riet-Correa, F.; Giannitti, F. Outbreak of contagious ecthyma caused by Orf virus (Parapoxvirus ovis) in a vaccinated sheep flock in Uruguay. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2019, 50, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Luo, S. Orf virus: A promising new therapeutic agent. Rev. Med. Virol. 2019, 29, e2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergqvist, C.; Kurban, M.; Abbas, O. Orf virus infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2017, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, J.A.; Balakrishnan, K.N.; Abdullah, A.A.; Mohamed, R.; Haron, A.W.; Jesse, F.F.A.; Noordin, M.M.; Mohd-Azmi, M.L. The re-emerging of orf virus infection: A call for surveillance, vaccination and effective control measures. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 120, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, S.; Cresswell, L.; Lovatt, F.; Gummery, E.; Onyango, J.; McQuilkin, C.; Wapenaar, W. Do UK sheep farmers use orf vaccine correctly and could their vaccination strategy affect vaccine efficacy? Vet. Rec. 2019, 185, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rziha, H.J.; Rohde, J.; Amann, R. Generation and Selection of Orf Virus (ORFV) Recombinants. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1349, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottone, R.; Büttner, M.; Bauer, B.; Henkel, M.; Hettich, E.; Rziha, H.J. Analysis of genomic rearrangement and subsequent gene deletion of the attenuated Orf virus strain D1701. Virus Res. 1998, 56, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, R.; Rohde, J.; Wulle, U.; Conlee, D.; Raue, R.; Martinon, O.; Rziha, H.J. A new rabies vaccine based on a recombinant ORF virus (parapoxvirus) expressing the rabies virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 1618–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rziha, H.J.; Büttner, M.; Müller, M.; Salomon, F.; Reguzova, A.; Liable, D.; Amann, R. Genomic characterization of orf virus strain D1701-V (Parapoxvirus) and development of novel sites for multiple transgene expression. Viruses 2019, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, T.; Planz, O.; Stitz, L.; Rziha, H.J. Novel recombinant parapoxvirus vectors induce protective humoral and cellular immunity against lethal herpesvirus challenge infection in mice. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 9312–9323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, E.M.; Rijsewijk, F.A.; Moonen-Leusen, H.W.; Bianchi, A.T.; Rziha, H.J. Comparison of different prime-boost regimes with DNA and recombinant Orf virus based vaccines expressing glycoprotein D of pseudorabies virus in pigs. Vaccine 2010, 28, 1808–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, J.; Schirrmeier, H.; Granzow, H.; Rziha, H.J. A new recombinant Orf virus (ORFV, Parapoxvirus) protects rabbits against lethal infection with rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV). Vaccine 2011, 29, 9256–9264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, J.; Amann, R.; Rziha, H.J. New Orf virus (Parapoxvirus) recombinant expressing H5 hemagglutinin protects mice against H5N1 and H1N1 influenza a virus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; He, W.; Gao, W.; Lu, H.; Han, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; Su, G.; et al. Orf virus DNA vaccines expressing ORFV 011 and ORFV 059 chimeric protein enhances immunogenicity. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diel, D.G.; Delhon, G.; Luo, S.; Flores, E.F.; Rock, D.L. A novel inhibitor of the NF-κB signaling pathway encoded by the parapoxvirus orf virus. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 3962–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diel, D.G.; Luo, S.; Delhon, G.; Peng, Y.; Flores, E.F.; Rock, D.L. A nuclear inhibitor of NF-κB encoded by a poxvirus. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Hao, W.; Duan, C.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Luo, S. The N terminus of orf virus-encoded protein 002 inhibits acetylation of NF-κB p65 by preventing Ser(276) phosphorylation. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e58854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diel, D.G.; Luo, S.; Delhon, G.; Peng, Y.; Flores, E.F.; Rock, D.L. Orf virus ORFV121 encodes a novel inhibitor of NF-κB that contributes to virus virulence. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatiwada, S.; Delhon, G.; Nagendraprabhu, P.; Chaulagain, S.; Luo, S.; Diel, D.G.; Flores, E.F.; Rock, D.L. A parapoxviral virion protein inhibits NF-κB signaling early in infection. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagendraprabhu, P.; Khatiwada, S.; Chaulagain, S.; Delhon, G.; Rock, D.L. A parapoxviral virion protein targets the retinoblastoma protein to inhibit NF-κB signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karki, M.; Kumar, A.; Arya, S.; Ramakrishnan, M.A.; Venkatesan, G. Poxviral E3L ortholog (Viral Interferon resistance gene) of orf viruses of sheep and goats indicates species-specific clustering with heterogeneity among parapoxviruses. Cytokine 2019, 120, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hain, K.S.; Joshi, L.R.; Okda, F.; Nelson, J.; Singrey, A.; Lawson, S.; Martins, M.; Pillatzki, A.; Kutish, G.F.; Nelson, E.A.; et al. Immunogenicity of a recombinant parapoxvirus expressing the spike protein of Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 2719–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, L.R.; Okda, F.A.; Singrey, A.; Maggioli, M.F.; Faccin, T.C.; Fernandes, M.H.V.; Hain, K.S.; Dee, S.; Bauermann, F.V.; Nelson, E.A.; et al. Passive immunity to porcine epidemic diarrhea virus following immunization of pregnant gilts with a recombinant orf virus vector expressing the spike protein. Arch. Virol. 2018, 163, 2327–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Joshi, L.R.; Rodrigues, F.S.; Anziliero, D.; Frandoloso, R.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L.; Weiblen, R.; Flores, E.F.; Diel, D.G. Immunogenicity of ORFV-based vectors expressing the rabies virus glycoprotein in livestock species. Virology 2017, 511, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulman, E.R.; Afonso, C.L.; Lu, Z.; Zsak, L.; Sur, J.H.; Sandybaev, N.T.; Kerembekova, U.Z.; Zaitsev, V.L.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. The genomes of sheeppox and goatpox viruses. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 6054–6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, T.R.; Babiuk, S.L.; Parkyn, G.R.; Copps, J.S.; Boyle, D.B. Capripoxvirus tissue tropism and shedding: A quantitative study in experimentally infected sheep and goats. Virology 2008, 371, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuppurainen, E.S.M.; Venter, E.H.; Shisler, J.L.; Gari, G.; Mekonnen, G.A.; Juleff, N.; Lyons, N.A.; De Clercq, K.; Upton, C.; Bowden, T.R.; et al. Review: Capripoxvirus diseases: Current status and opportunities for control. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.; Noyce, R.S.; Babiuk, L.A.; Lung, O.; Bulach, D.M.; Bowden, T.R.; Boyle, D.B.; Babiuk, S.; Evans, D.H. Extended sequencing of vaccine and wild-type capripoxvirus isolates provides insights into genes modulating virulence and host range. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gari, G.; Abie, G.; Gizaw, D.; Wubete, A.; Kidane, M.; Asgedom, H.; Bayissa, B.; Ayelet, G.; Oura, C.A.; Roger, F.; et al. Evaluation of the safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of three capripoxvirus vaccine strains against lumpy skin disease virus. Vaccine 2015, 33, 3256–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Jin, N.; Liu, Q.; Huo, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, B.; Ma, H.; Zhu, Z.; Cong, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of Semliki forest virus replicon-based DNA vaccines encoding goatpox virus structural proteins. Virology 2009, 391, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burles, K.; Irwin, C.R.; Burton, R.L.; Schriewer, J.; Evans, D.H.; Buller, R.M.; Barry, M. Initial characterization of vaccinia virus B4 suggests a role in virus spread. Virology 2014, 456–457, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burles, K.; van Buuren, N.; Barry, M. Ectromelia virus encodes a family of Ankyrin/F-box proteins that regulate NFκB. Virology 2014, 468–470, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, Y.; Chen, W.; Bu, Z. The 135 Gene of goatpox virus encodes an inhibitor of NF-κB and apoptosis and may serve as an improved insertion site to generate vectored live vaccine. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e00190-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Bai, B.; Fang, J.; Zhang, K.; Yin, X.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Ma, Y.; Cui, Y. Construction of an attenuated goatpox virus AV41 strain by deleting the TK gene and ORF8-18. Antivir. Res. 2018, 157, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).