Abstract

Since its discovery in 2001, Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV) has been identified globally, exhibiting predictable seasonal outbreaks primarily affecting young children, the elderly, and individuals with preexisting health conditions. The virus is transmitted through airborne droplets and is responsible for a notable percentage of respiratory illnesses, particularly in children under five years of age, with hospitalization rates peaking in the first year of life. The complex immune response elicited by hMPV, characterized by a Th17-like profile and excessive mucus production, contributes to respiratory complications, emphasizing the need for effective management strategies. This review discusses various diagnostic methods, emphasizing the potential of combining serology with RT-PCR to enhance diagnostic accuracy during outbreaks. Furthermore, it addresses the therapeutic approaches, including the promise of recombinant interferons and ongoing research on the use of passive immunity through neutralizing antibodies. A comprehensive overview of hMPV, emphasizing the importance of continued research to improve diagnostic and therapeutic options for this significant respiratory pathogen, offers promising strategies for manipulating responses through targeted interventions.

1. Introduction

Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV) was initially identified by van Den Hoogen et al., 2001, in Dutch children with acute lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) [1]. The pathology and clinical symptoms exhibited by hMPV are similar to those of the previously reported human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [2]. Clinically, hMPV infections are manifested by upper and lower respiratory tract infections, where LRTIs predominate with symptoms like bronchitis, bronchiolitis, cough, and other respiratory complications developed due to the absence of airflow [2,3,4]. Belonging to the Pneumoviridae family and Metapneumovirus genus, hMPV is an enveloped, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus that shares many genomic and clinical features with RSV. However, it lacks the nonstructural genes NS1 and NS2 [5]. hMPV infections span all age groups but pose the highest risk to infants, elderly adults, individuals with underlying cardiopulmonary conditions, and immunocompromised patients, including hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients [6]. Furthermore, hMPV infection in children under 2 years of age could lead to the development of asthma in the later stage of their life, and it also promotes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [2,7,8,9]. hMPV infection has been reported to cause 10–12% of virus-associated respiratory illness and hospitalization in children [4], and this infection is equivalent to influenza virus and parainfluenza virus types 1–3 [10].

hMPV infection results in a Th17-like immune response characterized by interleukin-6 (IL-6) and TNF⍺ secretion in the lungs, followed by an inadequate Th2-like profile resulting in the early secretion of various proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-8 [11,12,13,14]. Mice model studies showed that a cytokine, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), causes a delay in Th1-like immune response, ultimately stimulating cytokines related to a Th2-like profile with increased neutrophil infiltration upon infection [15]. This complex immune response and excessive mucus production collapse the respiratory airways [3,7]. Although hMPV is now globally distributed, its true burden remains underestimated due to limited testing, especially in low-resource settings. Historically, diagnosis relied on viral culture and serology, which lacked sensitivity and timeliness. However, the integration of molecular diagnostics, particularly real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and multiplex respiratory panels, has significantly improved case detection and epidemiological tracking [16].

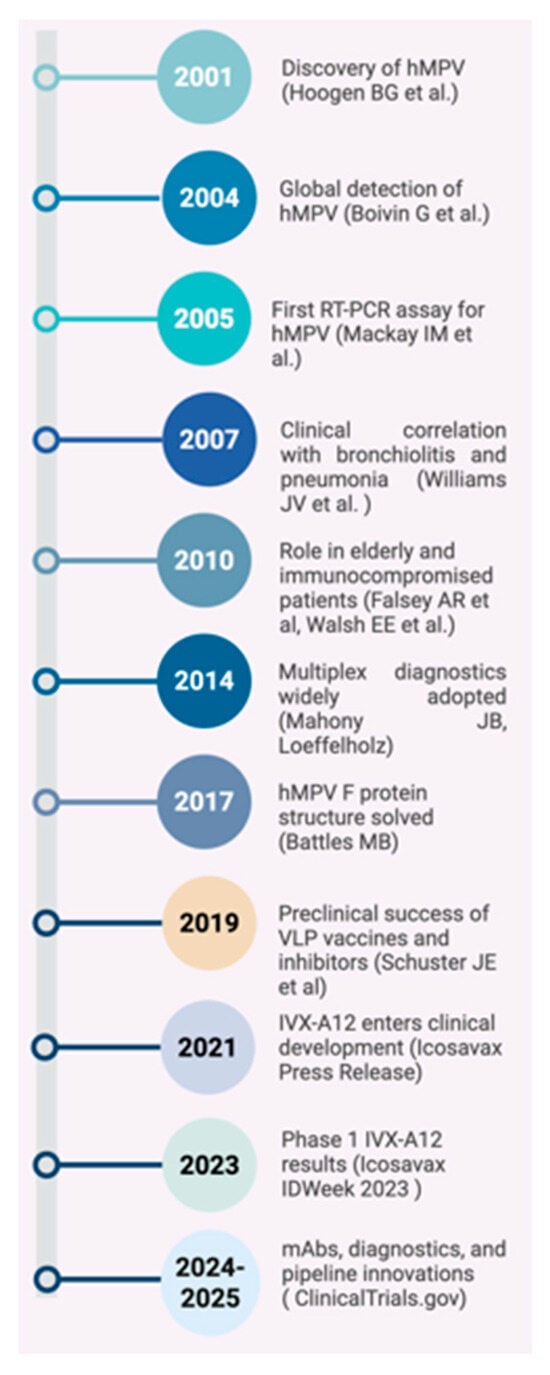

Despite improved diagnostics, no approved antiviral therapies or licensed vaccines for hMPV are currently available [Figure 1]. Supportive care remains the cornerstone of treatment, and most infections are self-limiting. Nevertheless, in severe cases, especially among high-risk populations, complications can lead to hospitalization and increased healthcare utilization [17]. Recent preclinical and clinical advancements show promise, including the development of virus-like particle (VLP)-based vaccines such as IVX-A12, monoclonal antibodies targeting the F protein, and small-molecule fusion inhibitors [18]. Understanding hMPV’s immune evasion mechanisms, host–pathogen interactions, and cross-protective immunity is pivotal for advancing therapeutic and preventive strategies. This review critically examines recent advances in the understanding of hMPV clinical impact across age and risk groups, evaluates current and emerging diagnostic strategies, and analyzes the therapeutic and vaccine development pipeline with emphasis on remaining challenges and priorities.

Figure 1.

Milestones in Human Metapneumovirus Research: From Discovery to Vaccine Development (2001–2025) [1,16,19,20,21,22,23,24].

2. Materials and Methods—Literature Search Strategy

We conducted a narrative search using multiple keywords including “hMPV”, “diagnostics”, “treatment” and “therapeutics” on PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases to look for research papers, review articles, guidelines, and studies to obtain relevant information, limited to studies published in the last 25 years (2001–2025). The analysis only included research articles, studies, guidelines, and review papers that were obtainable in English. Research that (i) was not written in English, (ii) comprised of comments, letters, case reports, abstracts from conferences, or (iii) had multiple entries were not included.

3. Epidemiology

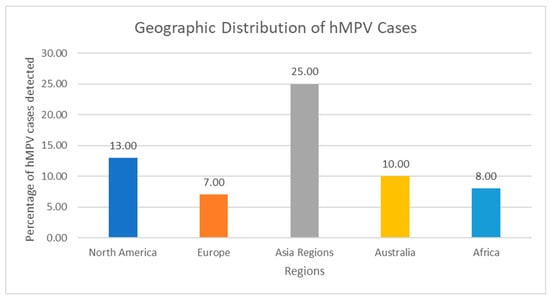

hMPV has been discovered in virtually all regions of the world since its first description in 2001, with documented circulation on every inhabited continent, including extensive reports from Latin America (Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Peru, Colombia, Mexico), the Middle East, and multiple sub-Saharan African countries. Considering observations from North America (the United States and Canada), Europe (the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Finland), Asia (Hong Kong and Japan), and Australia, hMPV has been discovered in the majority of regions of the world [25] [Figure 2]. hMPV has a predictable seasonality and has been detected on every continent. hMPV spreads by infectious airborne droplets like other respiratory viruses. It primarily affects young children and newborns, the elderly, and people with preexisting chronic illnesses, including emphysema, asthma, or compromised immune systems [1,26]. HIV-positive and non-immunocompromised South African children have also been shown to carry the virus [27].

Figure 2.

Geographic Distribution of hMPV Cases. Bar Chart: X-axis: Regions; Y-axis: Percentage of hMPV detection in acute respiratory illness—North America: 6–13%, Europe: 5–12%, Asia: 7–43%, Latin America: 3–15%, Africa: 4–18%, Australia: 7–10%. Note: These are not results of standardized global surveillance. Prevalence varies markedly according to testing practices, case definitions, seasonality, and inclusion of community vs. hospital cases. Most low- and middle-income regions (large parts of Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, South/Southeast Asia) remain under-represented because routine multiplex panels are rarely used. The erroneous assignment of Italian data to “Asia” in the previous version has been corrected.

The majority of children globally acquire infection with hMPV by the time they are 5 years old, according to sero-epidemiology research [28,29,30,31,32]. Nevertheless, reinfection happens, particularly in older and high-risk individuals, as a result of immune reactions that are not fully protective or infection with a novel genotype [30,33]. Cynomolgus macaques have a temporary immune defense to experimental hMPV infection, as shown by Van den Hoogen et al. [34]. Over the cold season of 2000–2001, Boivin et al. discovered hMPV in 2.3% of breath specimens [3]. Among the 26 hospitalized patients infected with hMPV, 35% were younger than 5 years old, and 46% were older than 65. A preexisting medical condition was present in one-third of hospitalized children below five years old, two-thirds of patients between the ages of 15 and 65, and all patients over 65 [35]. Although they happen across infancy, hospitalization rates for hMPV disease are greatest in the initial year of life. Hospitalization for hMPV peaks from 6 to 12 months of age, which is later than the peak for RSV (2–3 months), according to numerous studies [3,10,36,37,38,39,40]. According to the scant seroprevalence assessments conducted in Israel [29], Japan [28], and The Netherlands [1], nearly every child gets the disease by the time they are 5 to 10 years old.

Since its discovery in 2001, hMPV has been retrospectively and prospectively identified in virtually all regions where systematic testing has been performed. However, the reported detection rates vary widely (2–43% of acute respiratory infections) because of differences in study design, population, season, and diagnostic methods [3].

Pre-2015 era (mostly singleplex RT-PCR or culture-based hospital studies): detection rates in hospitalized children were typically 5–15% [3,10,36] and 2–13%in adults and elderly [35]. These figures almost certainly underestimated the true contribution because testing was restricted to RSV/influenza-negative samples.

2015–2025 era (widespread adoption of commercial multiplex panels): now report hMPV in 4–12% of all community-acquired respiratory illnesses across all ages, with peaks of 15–25% in children <5 years during winter–spring months in temperate climates [37,38]. In tropical regions the seasonality is less pronounced or bimodal.

High-risk groups (2018–2025 data): among hematopoietic stem-cell or solid-organ transplant recipients, hMPV accounts for 3–12% of respiratory viral infections, with progression to lower respiratory tract disease in 30–80% of cases [30,33].

Many fewer studies have been conducted on the relative contribution of hMPV to adult respiratory disorders. As much as 13 percent of hospitalized adults in Rochester, New York, have hMPV [33]. hMPV infection causes higher severity of illness and high rates of illness and death in the elderly, although it is usually moderate in normally well younger people. According to a later study, bronchitis or pneumonia struck at least 50% of older people infected with hMPV during an outbreak in a long-term care facility, resulting in a 50% fatality rate [19]. Over the course of four successive winters, Walsh et al. discovered that the percentage of adult hMPV infections ranged from 3% to 7.1% [33]. This is higher compared to the influenza A infection rate of 2.4% in identical groups over the same period of time and comparable to the yearly average infection rate for RSV (5.5%) [20]. A total of 2.2% of patients with community-transmitted acute RTI who saw a general physician and tested negative for influenza virus and RSV had hMPV [21]. According to Widmer et al., hMPV was responsible for 4.5% of acute RTI hospitalizations in persons over 50 during the colder months of three consecutive years [41]. RSV and influenza A had corresponding rates of 6.1% and 6.5%. The average yearly hospitalization rates for hMPV were 22.1/10,000 residents for people over 65 and 1.8/10,000 residents for persons aged 50–65. Relative to those diagnosed with influenza, those with hMPV infections were older, more prone to cardiovascular illness, and more inclined to receive an influenza vaccination [35].

Factors that underlie the severity of the illness and hospitalization are influenced by pre-existing illnesses, especially asthma. Seven percent of adults hospitalized for an acute asthma attack had hMPV isolated from them [22]. Similar to RSV infection, hMPV infection during the first two years of infancy increases the risk of developing asthma later in life [8]. According to one study, 16% of those diagnosed with hMPV had asthma, but not one of the 54 RSV+ individuals had this condition [38]. A total of 41% of hMPV+ children aged 5 to 13 had a prior asthma diagnosis, according to a separate study [23]. Individuals with preexisting medical disorders and those with impaired immune systems may be particularly vulnerable to hMPV. According to a study, a large number of hospitalized hMPV + patients older than five had other serious illnesses, including lymphoma or cystic fibrosis [38]. According to a different retrospective study, four of the 39 immunocompromised children with hMPV died from respiratory failure, and 17 of them developed pneumonia [42]. Sixty-seven percent of a group of patients aged 15 to 65 had underlying illnesses, including lung tumors or lymphoma [17]. Co-infections with additional bacterial or viral pathogens might make symptoms worse. Individuals with hMPV have viral co-infection frequencies ranging from 6 to 23% [23,33,43]; however, the severity of the disease appears to be unaffected by viral co-infections [43]. Recurrent bacterial pneumonia, on the other hand, is possible and linked to a higher death rate [44,45,46].

4. Structure and Function of hMPV

hMPV is a member of the enveloped, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus family Pneumoviridae and is closely linked to the Avian metapneumovirus (AMPV) [25]. hMPV diverged from AMPV, most especially subtype C, approximately 200–300 years ago [47,48,49,50,51]. It encompasses two main genetic lineages, A and B, of which A1, A2 (including A2a and A2b), and B1, B2 sublineages are further differentiated [5]. Lineage A2 is more common worldwide and is linked to severe respiratory illnesses [52].

Similar in structure to other Pneumoviridae, hMPV has a 150–200 nm diameter and a spherical to pleomorphic morphology. Surface glycoproteins necessary for entry and immune evasion are embedded in the virus’s outer lipid envelope, produced from the host cell membrane [53].

Nucleoprotein (N), Phosphoprotein (P), Matrix protein (M), Fusion protein (F), Attachment glycoprotein (G), Small hydrophobic protein (SH), Large polymerase protein (L), and M2 (accessory) protein are the primary proteins encoded by the hMPV genome, which is about 13.3 kilobase (kb). The gene sequence is 3’-N-P-M-F-M2-SH-G-L-5’ [54].

G protein shows redundancy with the F protein by aiding adhesion to host cell receptors, but it is not necessary for replication in vitro [55]. Additionally, there is strong evidence that the G protein helps to suppress the interferon-I (IFN-I) response [56], and it also helps to draw neutrophils to the airways by releasing more of the chemoattractants such as CXCL2, CCL3, CCL4, IL-17, and TNF [57]. In addition, SH protein may also operate as a viroporin and plays many roles in modulating the innate immune response, including inhibiting the IFN response [58]. Although its exact function is unknown, it is thought to influence host immune responses by preventing apoptosis. The G and SH proteins decrease the generation of type I interferon by interfering with pattern recognition receptor (PRR) signaling [59].

F protein mediates membrane fusion to enable viral entry. A fusion peptide is revealed by proteolytic cleavage, which is essential for infectivity [60]. Moreover, L protein, the large polymerase protein, can create new genetic material with cofactors. It has zinc-binding sites and diverse catalytic activity [61]. Matrix (M) protein connects the nucleocapsid to the lipid envelope and is essential for virion formation and budding. It has a Ca2+ binding site with high affinity [62]. This protein can cause the release of inflammatory cytokines in vitro cultures and appears to be secreted by infected cells in a soluble form [63]. The N protein builds the nucleocapsid, which firmly encloses the RNA genome to prevent its destruction. The N protein suppresses the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by blocking the activation of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [64]. To facilitate transcription and replication, the P protein serves as a cofactor for the L protein (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) [65]. The inclusion bodies commonly detected during hMPV infections are formed mainly by these two proteins, N and P [66].

5. Receptor Mechanism of hMPV Infection

Human and mouse model studies confirmed that the upper and lower respiratory tract and the lung resident leukocytes were the primary targets of hMPV [67]. Upon infection, hMPV causes a series of histopathological changes in the infected lungs that include loss of ciliation, damage to the respiratory epithelial architecture, exacerbated mucus production, sloughing of epithelial cells, and parenchymal pneumonia (inflammation of the lung interstitium) [7,68]. However, the exact mechanism behind hMPV immune evasion has not been clearly understood. The airway epithelial cell (AEC) infection is the first critical stage of acute hMPV infection [69]. In addition, airway macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) also play a vital role in sensing hMPV infection and its further development into airway inflammation [15,70].

Viral infections commonly trigger innate and adaptive immune responses, primarily attributed to the upregulated expression of IFN, and it is further mediated by the downstream interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) [71]. This, in turn, triggers and activates the interferon receptors (IFNR) expressed on the target cells, leading to antigen-dependent and independent cytotoxicity and ultimately eliminating the pathogen [71,72,73]. The following mechanisms are now considered well established because they have been independently reproduced by several laboratories using primary human airway epithelial cultures, murine models, and non-human primates. Studies revealed two major pathways that involve different PRRs-induced Type 1 INF secretion in response to hMPV infection. The first pathway involves retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-1) (relevant in AEC) and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MAD5) (relevant in DC)—helicases from the RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) family [74], and the second pathway involves Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) and TLR7 [75].

Upon hMPV infection, the recognition of viral double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) and uncapped 5’-triphosphates of the viral genome triggers the coupling of RLRs with the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) [74,75,76]. This activates a cascade of downstream signaling pathways leading to the secretion of Type I IFNs. Mechanistically, MAVS activates IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), which mediates the secretion of Type I IFN. In addition, it also results in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines via IRF-7 and Type III IFNs in an NF-κB-dependent manner [75]. In the second pathway, the viral products are recognized by TLRs, mainly TLR3 (in most cells) and TLR7 (in plasmacytoid DC). This leads to the activation of IRF3 and IRF7 via adaptor proteins TIR domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β (TRIF) and MyD88, respectively, resulting in the secretion of Type I IFNs [75,77]. Moreover, hMPV is self-equipped with glycoprotein (G) and phosphoprotein (P) that impair viral sensing through the inhibition of RIG1 and MAVS signaling [75,76]. Mainly, TLR4 signaling is impaired by viral G protein, even though the exact mechanism behind this phenomenon is not clearly available [57,78]. Direct anti-apoptotic effects of the SH protein in primary human airway cells are suggested by one report but have not been reproduced. The key virulence factors that negatively impact the signaling mediated through PRR have been identified as M2-2 and SH proteins. These proteins interact with the MyD88 and NF-κB-adaptor proteins of TLR [79,80]. Furthermore, reports depicting the impaired upregulation of IFN-β mediated through the M2-2 interaction with MAVS are available [77]. Ren et al. reported a downregulated expression of IFN-⍺ receptors viz Jak-1 and Tyk-2, upon hMPV infection [79]. In short, a strong IFN response to HPMV in AEC is attributed to IRF3, MDA5, RIG-1, or TLR3, while in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), it operates through the TLR7-IRF7 manner.

In addition to IFN response, Lay et al. reported a strong interleukin 33 (IL-33) and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) expression in response to hMPV infection in the AECs using an in vitro model [15]. These cytokines induce the expression of OX40L, leading to the activation of DCs, resulting in the priming of CD4+ T cells and their differentiation to Th2 cells [81,82]. Also, these activated DCs produce a Th2-enhancing chemokine and attractor of natural killer (NK) cells, CCl7 [83,84]. Later, TSLP was identified as a key molecule in hMPV-induced lung inflammation, conducted through the genetic ablation and immunological blocking of the TSLP-TSLR pathway in hMPV-infected mice [15]. Further research conducted by another group reported that the pro-inflammatory long form of TSLP is induced by hMPV infection, while the short form remains unchanged, and this induction is attributed via NF-κB-RIG-I-TLR3 manner facilitated via TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1) [85]. In summary, hMPV hampers or delays the efficient Th1 antiviral response through the activation of the TSLP pathway and favors the Th2 response [15].

6. Clinical Manifestations of hMPV Infection

Human metapneumovirus, a significant cause of respiratory tract infections (RTIs) across every age group, shows broad clinical scenarios ranging from asymptomatic to symptoms such as mild upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) to severe pneumonia [86] (Table 1). First identified in 2001, the clinical features of an hMPV infection are similar to an RSV infection, especially in children, and remain a significant global burden, particularly in the case of infants, the elderly, and individuals with compromised immune systems [1,19,20,87,88,89].

Table 1.

Signs and symptoms of hMPV infection. Abbreviation: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Congestive heart failure (CHF), Lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), Solid organ transplant (SOT), and Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

6.1. Clinical Presentation in Children

hMPV infection represents a significant cause of respiratory tract infections during the first year of life [20,90]. Clinical manifestations of hMPV in children can present as both URTIs and LRTIs [2,20,91]. A study conducted at the Vanderbilt Vaccine Clinic in Nashville, USA, identified the common presentations of hMPV-associated LRTIs in children. The findings indicated that hMPV-associated LRTIs could be presented as bronchiolitis (59%), croup (18%), asthma exacerbations (14%), and pneumonia (8%). The mean age of children affected by hMPV in this study was 11.6 months [20]. Few other studies also support these symptoms of hMPV-associated LRTIs [2,3,16,92,93]. RSV-infected children exhibit more severe symptoms such as dyspnea, feeding difficulties, and hypoxemia [3,16,38]. Although not frequent, hRSV-hMPV coinfections cause more severe symptoms, higher rates of hospitalization, and greater healthcare utilization, particularly in children, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals [94].

6.2. Clinical Presentation in Adults

In adults, hMPV is a common infection, and clinical features often range from asymptomatic to mild to moderate URTIs; however, it can also cause serious LRTIs that require hospital admission [33,35]. Even healthy adults present with mononucleosis-like illness [95]. In adult patients admitted to general hospitals, RSV and hMPV are linked to severe respiratory conditions that necessitate increased ventilation or oxygenation. Infection with these viruses in hospitalized patients can also cause exacerbations of asthma, COPD, and congestive heart failure (CHF) [96].

6.3. Clinical Presentation in Elderly and Immunocompromised

hMPV infection or reinfection contributes significantly to the burden of illness in older adults, especially immunosuppressed nursing home individuals with comorbid conditions such as chronic cardiac disease or frailty [24,97,98]. A study suggests that in recent years, most hospitalized patients with hMPV infections are elderly (mean age 75 years), and 85% have chronic heart or lung disease. Elderly people suffer from dyspnea and wheezing more compared to younger people, who manifest more hoarseness [24,98].

Immunocompromised patients, including solid organ transplant (SOT) and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) patients, hMPV, and other respiratory viruses, create a higher risk of morbidity and mortality when progressing from the upper to the lower respiratory tract [99,100]. hMPV is a recognized cause of both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections in lung transplant recipients. Among hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients, hMPV-related mortality has been reported to reach 39% [99,100,101].

6.4. Evidence Gaps in Clinical Research

Long-term pulmonary sequelae (wheezing, asthma) after hMPV in older children and adults are almost unstudied (virtually all data derive from early life infection). The true contribution of hMPV to COPD exacerbations and congestive heart failure decompensations in the elderly is probably underestimated because of low testing rates outside research settings. Impact of viral load, genotype (A vs. B), and co-infection on clinical severity remains conflicting across studies and requires standardized prospective cohorts [99,100,101].

7. Diagnosis and Surveillance of hMPV Infection

Early diagnosis of hMPV infection is crucial for implementing effective disease control measures, including outbreak prevention and timely patient care. Given the highly conserved amino acid sequences of the F protein in both hMPV and RSV, this similarity may offer valuable insights for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies [102]. Limited serological technologies have been developed to detect hMPV-specific antibodies [35,103,104,105]. Diagnosing hMPV infection can be made using several techniques, including culture, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), antigen detection, and serologic testing [106].

7.1. Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests and hMPV Culture

The detection of viral RNA using nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), such as reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), is the most sensitive method for diagnosing hMPV infection [107,108,109]. However, viral culture is challenging since hMPV exhibits slow growth in conventional cell cultures and produces mild cytopathic effects. A rapid culture technique known as shell vial amplification is used to enhance detection efficiency [106].

7.2. Antigen Detection and Serologic Testing

Methods for detecting hMPV antigens, such as enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), are not commonly used. No commercial immunochromatographic assays are available. A direct immunofluorescent-antibody (IFA) test, a rapid test in which labeled antibodies are used to detect specific viral antigens in direct patient materials, could be useful for diagnosing hMPV infections in outbreaks. The test results are known within two hours.

However, the sensitivity of IFA is lower than that of RT-PCR and needs to be validated before use. Detection of the immune response against the virus by serologic testing is only used for epidemiologic studies. One disadvantage of serology is that the interval between virus spreading and detection of hMPV-specific IgM and IgG antibodies is relatively long. However, a combined approach using serology and RT-PCR enhances diagnostic accuracy in hMPV infections, particularly when assessing the scale of an outbreak, such as in long-term care facilities [106,107,108,110].

7.3. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) technology is one of the most widely utilized isothermal methods for pathogen diagnosis [109]. LAMP is conducted in an isothermal environment (~65 °C) with high amplification efficiency, eliminating the need for complex thermal cycling equipment. Additionally, including two or three pairs of primers in the reaction system enhances specificity and amplification efficiency [111,112].

7.4. Recombinase-Aided Amplification and Direct Immunofluorescence Assay

Recombinase-aided amplification (RAA) assay is a recently developed isothermal amplification method characterized by simple operation, minimal equipment requirements, and high amplification efficiency [113]. The reverse transcription recombinase-aided amplification assay (RT-RAA) reaction system is conducted at 39 °C for 15 min, requiring less runtime compared to the RT-qPCR method [114]. The direct immunofluorescence assay (DFA), which employs virus-specific antibodies, is a swift method for detecting respiratory viruses and is widely utilized in diagnostic laboratories. Specific antibodies for hMPV have been commercially produced for use in DFA. However, it is important to note that this method may not achieve the same sensitivity as RT-PCR in detecting hMPV [115].

7.5. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) represents a cutting-edge, high-throughput diagnostic approach that is increasingly utilized for the analysis of genetic material from diverse microorganisms without prior knowledge of specific pathogens [116]. The application of nanopore metagenomic sequencing technology in exploring the nosocomial transmission of hMPV among hematology patients demonstrated notable effectiveness, successfully producing hMPV reads from 80% of the samples (20 out of 25) and retrieving complete hMPV genomes from 15 of those samples. These data indicate that this technology can be used to diagnose hMPV infection, but the sensitivity should be further improved [116]. Inclusion of hMPV in virtually all commercial multiplex panels has increased detection rates 5–10-fold in routine clinical practice. Combined serological + molecular approaches during nosocomial outbreaks achieve >98% case ascertainment [116].

8. Treatment and Prevention of hMPV

Although there is no specific antiviral treatment for hMPV, most current therapeutic approaches are supportive and symptomatic, prioritizing lowering respiratory symptoms and avoiding consequences [61].

8.1. Supportive Care

As of this moment, nearly all hMPV infection methods are supportive. Intravenous hydration and oxygen supplementation, using antipyretics such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen to control fever, and decongestants to reduce nasal symptoms are the main treatments for hospitalized infants and children. Despite extensive empirical use, bronchodilators and corticosteroids lack evidence to support their effectiveness [117]. Saline drops and nasal suctioning are often used in pediatric populations to alleviate nasal blockage. These interventions aim to ensure patient comfort while the immune system resolves the infection.

Oxygen supplementation is essential in hospitalized patients, particularly those with hypoxemia or respiratory distress. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation and high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy are frequently used [118] to treat acute respiratory distress. In severe cases, especially in newborns and elderly individuals with comorbidities, mechanical ventilation may be required [119].

8.2. Antiviral Therapies

Even though hMPV is a widespread issue, there are presently no approved antiviral medications to treat it. However, preclinical research and small-scale clinical trials have investigated several potential antivirals. The broad-spectrum antiviral ribavirin (anecdotal use only) has demonstrated in vitro action against hMPV, with varying degrees of success in animal models [61]. Due to serious side effects such as hemolytic anemia and teratogenicity, its clinical use is restricted. It is usually saved for severe infections in immunocompromised adults, such as lung transplants, cancer, stem cell transplants, or people infected with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [120].

For severely immunocompromised patients with progressive lower-respiratory-tract disease, ribavirin ± IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin) is sometimes used on a compassionate basis, but this practice rests on case reports and small retrospective series only; no controlled evidence of efficacy exists. The most promising near-term specific interventions are anti-F monoclonal antibodies and combined hMPV/RSV vaccines now in clinical development, but none are available for clinical use today. In in vitro and animal models, monoclonal antibodies have demonstrated promising results targeting the hMPV F protein, promoting viral fusion and entry. Passive immunity in the form of neutralizing antibodies is an additional alternative for prophylaxis or treatment in the absence of an approved vaccine. Even though these treatments have not been implemented in clinical settings yet, research is still being conducted to develop them for both preventative and therapeutic purposes [121].

8.3. Immunomodulatory Therapies

Studies comparing vaccinated and experimentally infected mice have shown that the acquired immune response triggered by hMPV is unable to effectively remove the virus from the airways, resulting in lung damage and an exaggerated inflammatory response. Poor T and B cell immunological memory development occurs after disease clearance, which is thought to encourage reinfections and viral dissemination in the population [56,122].

Corticosteroids and other immunomodulatory drugs have been attempted to reduce inflammation, however, their use is still debatable. Although some research indicates that corticosteroids may improve oxygenation and lessen lung inflammation, other trials show no discernible therapeutic effect or perhaps a higher risk of subsequent infections. Systemic corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for hMPV infection. Their use should be restricted to patients with wheezing due to underlying asthma or COPD exacerbation triggered by hMPV.

Corticosteroids are, therefore, not usually advised for hMPV infections unless there are exacerbations of COPD or asthma as concurrent diseases [123].

8.4. Adjunctive Therapies

For hMPV, adjuvant medicines such as immunoglobulin therapy and interferon-based treatments have been researched. Pediatric patients with hMPV infection who are immunocompromised had elevated mortality and LRTI rates. More research is needed to determine the advantages of ribavirin and intravenous immunoglobulin treatment in this patient population [124]. However, when IFN-λ was administered to hMPV-infected mice, the lung inflammatory response, viral titer, and disease severity decreased. The hMPV G protein was also involved in controlling the virus-induced IFN-λ response. These findings demonstrate that type III IFNs, or IFN-λs, are essential for protection against hMPV infection [125].

9. Vaccine Development and Future Prospects

No vaccine development for hMPV has progressed significantly in recent years, and no vaccine is currently licensed for clinical use. Multiple platforms are under investigation, including live-attenuated viruses, recombinant viral vectors, subunit vaccines (primarily based on the pre- or post-fusion F protein), virus-like particles, and mRNA-based approaches [126,127,128,129]. Among these, chimeric live-attenuated candidates and prefusion-stabilized F-protein subunit vaccines have shown the most promising immunogenicity and protection in preclinical animal models and early phase human trials. A bivalent hMPV/RSV prefusion F vaccine candidate (mRNA-136) and a virus-like particle-based candidate (IVX-A12) are currently being evaluated in phase 1/2 clinical studies. Monoclonal antibodies targeting the hMPV F protein have demonstrated prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy in animal models and are also advancing toward clinical evaluation. Although these candidates offer hope for future prevention, particularly in high-risk populations, effective outbreak control through vaccination is not yet possible. Although the most promising vaccine approach for hMPV is a live attenuated vaccine, there is currently no approved vaccine against it. However, finding an attenuated virus strain with the optimal balance of immunogenicity and attenuation is still challenging. Reverse genetics have been used to create a panel of recombinant hMPVs that were specifically defective in ribose 2′-O methyltransferase (Mtase) but not G-N-7 Mtase. Despite their high immunogenicity, these Mtase-defective hMPVs were genetically stable and adequately attenuated [127,128]. Subunit vaccines based on the F protein are also being studied for their potential to induce neutralizing antibodies [129].

If successful, the availability of effective vaccines will significantly reduce the reliance on supportive care and therapeutic interventions, especially in high-risk populations, and may enable the long-term control of hMPV circulation. To date, no hMPV vaccine has progressed beyond phase 2 clinical trials.

10. Conclusions

Human metapneumovirus remains a major global cause of acute respiratory illness, particularly in young children, older adults, and immunocompromised individuals. Despite two decades of research, important knowledge and clinical gaps persist: (1) the true disease burden in low- and middle-income countries and in adults remains underestimated because of limited systematic testing; (2) no specific antiviral drug or licensed vaccine is available; (3) the immunological basis for frequent reinfection and the link between early life hMPV infection and subsequent wheezing/asthma requires further elucidation; and (4) rapid, affordable point-of-care diagnostics suitable for resource-limited settings are still lacking. Promising directions include prefusion-stabilized F-protein subunit and mRNA vaccines (currently in phase 1/2 trials), long-acting monoclonal antibodies, and novel small-molecule fusion inhibitors. Large-scale phase 3 efficacy trials improved global surveillance, and studies of combination hMPV/RSV vaccines will be critical to reduce the substantial morbidity caused by this pathogen in vulnerable populations worldwide. Key priorities for the coming years include: (i) completion of phase 2/3 trials of the most advanced candidates (notably the bivalent hMPV/RSV prefusion F vaccine IVX-A12 and mRNA-based platforms), (ii) evaluation of monoclonal antibodies targeting the hMPV fusion protein for passive immunization of high-risk infants and immunocompromised individuals, (iii) deeper elucidation of incomplete natural immunity and viral immune-evasion mechanisms to guide next-generation vaccine design, and (iv) establishment of systematic global surveillance, particularly in currently underrepresented regions such as Latin America and Southeast Asia, to better define disease burden and circulating genotypes. Large-scale clinical trials, long-term epidemiological research, and improved worldwide surveillance are crucial for reducing the public health impact of hMPV. To lessen the burden of hMPV on vulnerable populations worldwide, considerable progress can be made in creating efficient preventive and therapeutic techniques by tackling these issues.

Author Contributions

Concept: P.S., M.M.R. and R.R.K.K. Wrote and edited the manuscript: P.S., M.M.R., M.T., M.A.M., A.N.P. and R.R.K.K. Prepared figures and tables: M.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used OpenAI’s ChatGPT (version GPT-4) to assist in generating Figure 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van Den Hoogen, B.G.; De Jong, J.C.; Groen, J.; Kuiken, T.; De Groot, R.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E. A Newly Discovered Human Pneumovirus Isolated from Young Children with Respiratory Tract Disease. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildgen, V.; van den Hoogen, B.; Fouchier, R.; Tripp, R.A.; Alvarez, R.; Manoha, C.; Williams, J.; Schildgen, O. Human Metapneumovirus: Lessons Learned over the First Decade. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 734–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, G.; De Serres, G.; Côté, S.; Gilca, R.; Abed, Y.; Rochette, L.; Bergeron, M.G.; Déry, P. Human Metapneumovirus Infections in Hospitalized Children. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003, 9, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuillet, F.; Lina, B.; Rosa-Calatrava, M.; Boivin, G. Ten Years of Human Metapneumovirus Research. J. Clin. Virol. 2012, 53, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biacchesi, S.; Skiadopoulos, M.H.; Boivin, G.; Hanson, C.T.; Murphy, B.R.; Collins, P.L.; Buchholz, U.J. Genetic Diversity between Human Metapneumovirus Subgroups. Virology 2003, 315, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.V.; Wang, C.K.; Yang, C.; Tollefson, S.J.; House, F.S.; Heck, J.M.; Chu, M.; Brown, J.B.; Lintao, L.D.; Quinto, J.D.; et al. The Role of Human Metapneumovirus in Upper Respiratory Tract Infections in Children: A 20-Year Experience. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 193, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamelin, M.-E.; Prince, G.A.; Gomez, A.M.; Kinkead, R.; Boivin, G. Human Metapneumovirus Infection Induces Long-Term Pulmonary Inflammation Associated with Airway Obstruction and Hyperresponsiveness in Mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 193, 1634–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, M.L.; Calvo, C.; Casas, I.; Bracamonte, T.; Rellán, A.; Gozalo, F.; Tenorio, T.; Pérez-Breña, P. Human Metapneumovirus Bronchiolitis in Infancy Is an Important Risk Factor for Asthma at Age 5. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2007, 42, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurs, N.; Aljassim, F.; Kjellman, B.; Robinson, P.D.; Sigurbergsson, F.; Bjarnason, R.; Gustafsson, P.M. Asthma and Allergy Patterns over 18 Years after Severe RSV Bronchiolitis in the First Year of Life. Thorax 2010, 65, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M.; Zhu, Y.; Griffin, M.R.; Weinberg, G.A.; Hall, C.B.; Szilagyi, P.G.; Staat, M.A.; Iwane, M.; Prill, M.M.; Williams, J.V. Burden of Human Metapneumovirus Infection in Young Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, B.; Neumann-Haefelin, D.; Schmitt-Graeff, A.; Weckmann, M.; Mattes, J.; Ehl, S.; Falcone, V. Human Metapneumovirus Induces More Severe Disease and Stronger Innate Immune Response in BALB/c Mice as Compared with Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Respir. Res. 2007, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnani, S. Regulation of the T Cell Response. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2006, 36, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietta, P.; Delsante, G. The Effector T Helper Cell Triade. Riv. Biol. 2009, 102, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, T.; Amakawa, R.; Inaba, M.; Hori, T.; Ota, M.; Nakamura, K.; Takebayashi, M.; Miyaji, M.; Yoshimura, T.; Inaba, K.; et al. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Regulate Th Cell Responses through OX40 Ligand and Type I IFNs. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 4253–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, M.K.; Céspedes, P.F.; Palavecino, C.E.; León, M.A.; Díaz, R.A.; Salazar, F.J.; Méndez, G.P.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. Human Metapneumovirus Infection Activates the TSLP Pathway That Drives Excessive Pulmonary Inflammation and Viral Replication in Mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015, 45, 1680–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahony, J.B. Detection of Respiratory Viruses by Molecular Methods. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 21, 716–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, G.; Abed, Y.; Pelletier, G.; Ruel, L.; Moisan, D.; Côté, S.; Peret, T.C.T.; Erdman, D.D.; Anderson, L.J. Virological Features and Clinical Manifestations Associated with Human Metapneumovirus: A New Paramyxovirus Responsible for Acute Respiratory-Tract Infections in All Age Groups. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 186, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battles, M.B.; Langedijk, J.P.; Furmanova-Hollenstein, P.; Chaiwatpongsakorn, S.; Costello, H.M.; Kwanten, L.; Vranckx, L.; Vink, P.; Jaensch, S.; Jonckers, T.H.M.; et al. Molecular Mechanism of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Inhibitors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boivin, G.; Serres, G.D.; Hamelin, M.-E.; Cote, S.; Argouin, M.; Tremblay, G.; Maranda-Aubut, R.; Sauvageau, C.; Ouakki, M.; Boulianne, N.; et al. An Outbreak of Severe Respiratory Tract Infection Due to Human Metapneumovirus in a Long-Term Care Facility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.V.; Harris, P.A.; Tollefson, S.J.; Halburnt-Rush, L.L.; Pingsterhaus, J.M.; Edwards, K.M.; Wright, P.F.; Crowe, J.E. Human Metapneumovirus and Lower Respiratory Tract Disease in Otherwise Healthy Infants and Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, I.M.; Jacob, K.C.; Woolhouse, D.; Waller, K.; Syrmis, M.W.; Whiley, D.M.; Siebert, D.J.; Nissen, M.; Sloots, T.P. Molecular Assays for Detection of Human Metapneumovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battles, M.B.; Más, V.; Olmedillas, E.; Cano, O.; Vázquez, M.; Rodríguez, L.; Melero, J.A.; McLellan, J.S. Structure and Immunogenicity of Pre-Fusion-Stabilized Human Metapneumovirus F Glycoprotein. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, J.E.; Cox, R.G.; Hastings, A.K.; Boyd, K.L.; Wadia, J.; Chen, Z.; Burton, D.R.; Williamson, R.A.; Williams, J.V. A Broadly Neutralizing Human Monoclonal Antibody Exhibits In Vivo Efficacy Against Both Human Metapneumovirus and Respiratory Syncytial Virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 211, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falsey, A.R.; Erdman, D.; Anderson, L.J.; Walsh, E.E. Human Metapneumovirus Infections in Young and Elderly Adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 187, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamelin, M.; Abed, Y.; Boivin, G. Human Metapneumovirus: A New Player among Respiratory Viruses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.S. Epidemiology of Human Metapneumovirus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhi, S.A.; Ludewick, H.; Abed, Y.; Klugman, K.P.; Boivin, G. Human Metapneumovirus-Associated Lower Respiratory Tract Infections among Hospitalized Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1)-Infected and HIV-1-Uninfected African Infants. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, 1705–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebihara, T.; Endo, R.; Kikuta, H.; Ishiguro, N.; Yoshioka, M.; Ma, X.; Kobayashi, K. Seroprevalence of Human Metapneumovirus in Japan. J. Med. Virol. 2003, 70, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.G.; Zakay-Rones, Z.; Fadeela, A.; Greenberg, D.; Dagan, R. High Seroprevalence of Human Metapneumovirus among Young Children in Israel. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 188, 1865–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlin, J.A.; Hickey, A.C.; Ulbrandt, N.; Chan, Y.; Endy, T.P.; Boukhvalova, M.S.; Chunsuttiwat, S.; Nisalak, A.; Libraty, D.H.; Green, S.; et al. Human Metapneumovirus Reinfection among Children in Thailand Determined by ELISA Using Purified Soluble Fusion Protein. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 198, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüsebrink, J.; Wiese, C.; Thiel, A.; Tillmann, R.-L.; Ditt, V.; Müller, A.; Schildgen, O.; Schildgen, V. High Seroprevalence of Neutralizing Capacity against Human Metapneumovirus in All Age Groups Studied in Bonn, Germany. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010, 17, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, S.R.; Ryder, A.B.; Tollefson, S.J.; Xu, M.; Saville, B.R.; Williams, J.V. Seroepidemiologies of Human Metapneumovirus and Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Young Children, Determined with a New Recombinant Fusion Protein Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2013, 20, 1654–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E.E.; Peterson, D.R.; Falsey, A.R. Human Metapneumovirus Infections in Adults: Another Piece of the Puzzle. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Hoogen, B.G.; Herfst, S.; De Graaf, M.; Sprong, L.; Van Lavieren, R.; Van Amerongen, G.; Yüksel, S.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; De Swart, R.L. Experimental Infection of Macaques with Human Metapneumovirus Induces Transient Protective Immunity. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, L.; Thijsen, S.; Van Elden, L.; Heemstra, K. Human Metapneumovirus in Adults. Viruses 2013, 5, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosis, S.; Esposito, S.; Niesters, H.G.M.; Crovari, P.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Principi, N. Impact of Human Metapneumovirus in Childhood: Comparison with Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Influenza Viruses. J. Med. Virol. 2005, 75, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiris, J.S.M.; Tang, W.-H.; Chan, K.-H.; Khong, P.-L.; Guan, Y.; Lau, Y.-L.; Chiu, S.S. Children with Respiratory Disease Associated with Metapneumovirus in Hong Kong. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003, 9, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hoogen, B.G.; van Doornum, G.J.J.; Fockens, J.C.; Cornelissen, J.J.; Beyer, W.E.P.; de Groot, R.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Prevalence and Clinical Symptoms of Human Metapneumovirus Infection in Hospitalized Patients. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 188, 1571–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, A.J.; Hasenbein, M.E.; Feldman, H.A.; Cole, S.E.; Offermann, J.T.; Riley, A.M.; Lieu, T.A. Human Metapneumovirus in Children Tested at a Tertiary-Care Hospital. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 190, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.J.; Simões, E.A.F.; Buttery, J.P.; Dennehy, P.H.; Domachowske, J.B.; Jensen, K.; Lieberman, J.M.; Losonsky, G.A.; Yogev, R. Prevalence and Characteristics of Human Metapneumovirus Infection Among Hospitalized Children at High Risk for Severe Lower Respiratory Tract Infection. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2012, 1, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffelholz, M.; Chonmaitree, T. Advances in Diagnosis of Respiratory Virus Infections. Int. J. Microbiol. 2010, 2010, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsey, A.R.; Hennessey, P.A.; Formica, M.A.; Cox, C.; Walsh, E.E. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Elderly and High-Risk Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1749–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockton, J.; Stephenson, I.; Fleming, D.; Zambon, M. Human Metapneumovirus as a Cause of Community-Acquired Respiratory Illness1. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmer, K.; Zhu, Y.; Williams, J.V.; Griffin, M.R.; Edwards, K.M.; Talbot, H.K. Rates of Hospitalizations for Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Human Metapneumovirus, and Influenza Virus in Older Adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 206, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.V.; Crowe, J.E., Jr.; Enriquez, R.; Minton, P.; Peebles, R.S., Jr.; Hamilton, R.G.; Higgins, S.; Griffin, M.; Hartert, T.V. Human Metapneumovirus Infection Plays an Etiologic Role in Acute Asthma Exacerbations Requiring Hospitalization in Adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 192, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.M.; Edwards, K.M.; Zhu, Y.; Griffin, M.R.; Weinberg, G.A.; Szilagyi, P.G.; Staat, M.A.; Payne, D.C.; Williams, J.V. Clinical Features of Human Metapneumovirus Infection in Ambulatory Children Aged 5–13 Years. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2018, 7, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuerman, O.; Barkai, G.; Mandelboim, M.; Mishali, H.; Chodick, G.; Levy, I. Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV) Infection in Immunocompromised Children. J. Clin. Virol. 2016, 83, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaeder, M.C.; Custer, J.W.; Bembea, M.M.; Aganga, D.O.; Song, X.; Scafidi, S. A Multicenter Outcomes Analysis of Children With Severe Viral Respiratory Infection Due to Human Metapneumovirus. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 14, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampofo, K.; Bender, J.; Sheng, X.; Korgenski, K.; Daly, J.; Pavia, A.T.; Byington, C.L. Seasonal Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in Children: Role of Preceding Respiratory Viral Infection. Pediatrics 2008, 122, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, M.; Yoshida, H.; Gotoh, K.; Hamada, N.; Motooka, D.; Nakamura, S.; Yamamoto, N.; Hamaguchi, S.; Akeda, Y.; Watanabe, H.; et al. Severe Respiratory Failure Due to Co-Infection with Human Metapneumovirus and Streptococcus Pneumoniae. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2014, 12, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Hoogen, B.G.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Analysis of the Genomic Sequence of a Human Metapneumovirus. Virology 2002, 295, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, G.; Mackay, I.; Sloots, T.P.; Madhi, S.; Freymuth, F.; Wolf, D.; Shemer-Avni, Y.; Ludewick, H.; Gray, G.C.; LeBlanc, E. Global Genetic Diversity of Human Metapneumovirus Fusion Gene. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1154–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parija, S.C. Paramyxoviruses. In Textbook of Microbiology and Immunology; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 811–824. ISBN 978-981-19-3314-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.B. Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Parainfluenza Virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1917–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, H.; Mirza, A.M.; Iorio, R.M.; Peeples, M.E.; Niewiesk, S.; Li, J. Roles of the Putative Integrin-Binding Motif of the Human Metapneumovirus Fusion (F) Protein in Cell-Cell Fusion, Viral Infectivity, and Pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4338–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Céspedes, P.F.; Palavecino, C.E.; Kalergis, A.M.; Bueno, S.M. Modulation of Host Immunity by the Human Metapneumovirus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29, 795–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Liu, T.; Shan, Y.; Li, K.; Garofalo, R.P.; Casola, A. Human Metapneumovirus Glycoprotein G Inhibits Innate Immune Responses. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheemarla, N.; Guerrero-Plata, A. Human Metapneumovirus Attachment Protein Contributes to Neutrophil Recruitment into the Airways of Infected Mice. Viruses 2017, 9, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammawat, S.; Sadlon, T.A.; Hallsworth, P.G.; Gordon, D.L. Role of Cellular Glycosaminoglycans and Charged Regions of Viral G Protein in Human Metapneumovirus Infection. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11767–11774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baturcam, E.; Snape, N.; Yeo, T.H.; Schagen, J.; Thomas, E.; Logan, J.; Galbraith, S.; Collinson, N.; Phipps, S.; Fantino, E.; et al. Human Metapneumovirus Impairs Apoptosis of Nasal Epithelial Cells in Asthma via HSP70. J. Innate Immun. 2017, 9, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafagati, N.; Williams, J. Human Metapneumovirus–What We Know Now. F1000Research 2018, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumat, M.R.; Nguyen Huong, T.; Wong, P.; Loo, L.H.; Tan, B.H.; Fenwick, F.; Toms, G.L.; Sugrue, R.J. Imaging Analysis of Human Metapneumovirus-Infected Cells Provides Evidence for the Involvement of F-Actin and the Raft-Lipid Microdomains in Virus Morphogenesis. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnaud-Baule, A.; Reynard, O.; Perret, M.; Berland, J.-L.; Maache, M.; Peyrefitte, C.; Vernet, G.; Volchkov, V.; Paranhos-Baccalà, G. The Human Metapneumovirus Matrix Protein Stimulates the Inflammatory Immune Response in Vitro. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, M.; Bertinelli, M.; Leyrat, C.; Paesen, G.C.; Saraiva de Oliveira, L.F.; Huiskonen, J.T.; Grimes, J.M. Nucleocapsid Assembly in Pneumoviruses Is Regulated by Conformational Switching of the N Protein. eLife 2016, 5, e12627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R. Characterization of the Function and Regulation of the HMPV Phosphoprotein. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Kentucky Libraries, Lexington, KY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes-Muñoz, N.; Branttie, J.; Slaughter, K.B.; Dutch, R.E. Human Metapneumovirus Induces Formation of Inclusion Bodies for Efficient Genome Replication and Transcription. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01282-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, S.O.; Kozakewich, H.P.W.; Perez-Atayde, A.R.; McAdam, A.J. Pathology of Human Metapneumovirus Infection: Insights into the Pathogenesis of a Newly Identified Respiratory Virus. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2004, 7, 478–486; discussion 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darniot, M.; Petrella, T.; Aho, S.; Pothier, P.; Manoha, C. Immune Response and Alteration of Pulmonary Function after Primary Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV) Infection of BALB/c Mice. Vaccine 2005, 23, 4473–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-F.; Tsao, K.-C.; Liu, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Yu, P.-C.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chou, C. Diagnosis of Human Metapneumovirus in Patients Hospitalized with Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infection Using a Metal-Enhanced Fluorescence Technique. J. Virol. Methods 2015, 213, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, P.K.; Kondziolka, D.; Lunsford, L.D. Stereotactic Diagnosis and Treatment of Pineal Region Tumours and Vascular Malformations. Acta Neurochir. 1992, 116, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivashkiv, L.B.; Donlin, L.T. Regulation of Type I Interferon Responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riboldi, E.; Daniele, R.; Cassatella, M.A.; Sozzani, S.; Bosisio, D. Engagement of BDCA-2 Blocks TRAIL-Mediated Cytotoxic Activity of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Immunobiology 2009, 214, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimori, Y.; Nakamura, R.; Yamada, H.; Shibata, K.; Maeda, N.; Kase, T.; Yoshikai, Y. Type I Interferon Plays Opposing Roles in Cytotoxicity and Interferon-γ Production by Natural Killer and CD8 T Cells after Influenza A Virus Infection in Mice. J. Innate Immun. 2014, 6, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Bao, X.; Liu, T.; Lai, S.; Li, K.; Garofalo, R.P.; Casola, A. Role of Retinoic Acid Inducible Gene-I in Human Metapneumovirus-Induced Cellular Signalling. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 1978–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goutagny, N.; Jiang, Z.; Tian, J.; Parroche, P.; Schickli, J.; Monks, B.G.; Ulbrandt, N.; Ji, H.; Kiener, P.A.; Coyle, A.J.; et al. Cell Type-Specific Recognition of Human Metapneumoviruses (HMPVs) by Retinoic Acid-Inducible Gene I (RIG-I) and TLR7 and Viral Interference of RIG-I Ligand Recognition by HMPV-B1 Phosphoprotein. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Kolli, D.; Ren, J.; Liu, T.; Garofalo, R.P.; Casola, A. Human Metapneumovirus Glycoprotein G Disrupts Mitochondrial Signaling in Airway Epithelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Wang, Q.; Kolli, D.; Prusak, D.J.; Tseng, C.-T.K.; Chen, Z.J.; Li, K.; Wood, T.G.; Bao, X. Human Metapneumovirus M2-2 Protein Inhibits Innate Cellular Signaling by Targeting MAVS. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 13049–13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolli, D.; Bao, X.; Liu, T.; Hong, C.; Wang, T.; Garofalo, R.P.; Casola, A. Human Metapneumovirus Glycoprotein G Inhibits TLR4-Dependent Signaling in Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Kolli, D.; Liu, T.; Xu, R.; Garofalo, R.P.; Casola, A.; Bao, X. Human Metapneumovirus Inhibits IFN-β Signaling by Downregulating Jak1 and Tyk2 Cellular Levels. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Kolli, D.; Liu, T.; Shan, Y.; Garofalo, R.P.; Casola, A. Human Metapneumovirus Small Hydrophobic Protein Inhibits NF-kappaB Transcriptional Activity. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 8224–8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, G.; Déry, P.; Abed, Y.; Boivin, G. Respiratory Tract Reinfections by the New Human Metapneumovirus in an Immunocompromised Child. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 976–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-F.; Wang, C.K.; Tollefson, S.J.; Piyaratna, R.; Lintao, L.D.; Chu, M.; Liem, A.; Mark, M.; Spaete, R.R.; Crowe, J.E.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Evolution of Human Metapneumovirus Fusion Protein over Twenty Years. Virol. J. 2009, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inngjerdingen, M.; Damaj, B.; Maghazachi, A.A. Human NK Cells Express CC Chemokine Receptors 4 and 8 and Respond to Thymus and Activation-Regulated Chemokine, Macrophage-Derived Chemokine, and I-309. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 4048–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-J. Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin: Master Switch for Allergic Inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lund, C.; Nervik, I.; Loevenich, S.; Døllner, H.; Anthonsen, M.W.; Johnsen, I.B. Characterization of Signaling Pathways Regulating the Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Long Form Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin upon Human Metapneumovirus Infection. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsey, A.R. Human Metapneumovirus Infection in Adults. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2008, 27, S80–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkesmann, A.; Schildgen, O.; Eis-Hübinger, A.M.; Geikowski, T.; Glatzel, T.; Lentze, M.J.; Bode, U.; Simon, A. Human Metapneumovirus Infections Cause Similar Symptoms and Clinical Severity as Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2006, 165, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.; Mohakud, N.K.; Pena, L.; Kumar, S. Human Metapneumovirus: Review of an Important Respiratory Pathogen. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 25, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.J.; Mousa, J.J. Structural Basis for Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Human Metapneumovirus Neutralization. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2023, 61, 101337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, J.E. Human Metapneumovirus as a Major Cause of Human Respiratory Tract Disease. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004, 23, S215–S221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papenburg, J.; Boivin, G. The Distinguishing Features of Human Metapneumovirus and Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Rev. Med. Virol. 2010, 20, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulongne, V.; Guyon, G.; Rodi??re, M.; Segondy, M. Human Metapneumovirus Infection in Young Children Hospitalized With Respiratory Tract Disease. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2006, 25, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, M.G.; Cowell, A.; Dove, W.; Greensill, J.; McNamara, P.S.; Halfhide, C.; Shears, P.; Smyth, R.L.; Hart, C.A. Dual Infection of Infants by Human Metapneumovirus and Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus Is Strongly Associated with Severe Bronchiolitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 191, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, G.A.; Gálvez, N.M.S.; Soto, J.A.; Andrade, C.A.; Kalergis, A.M. Bacterial and Viral Coinfections with the Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, I.W.S.; To, K.K.W.; Tang, B.S.F.; Chan, K.-H.; Hui, C.-K.; Cheng, V.C.C.; Yuen, K.-Y. Human Metapneumovirus Infection in an Immunocompetent Adult Presenting as Mononucleosis-like Illness. J. Infect. 2008, 56, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, A.; Nguyen, D.C.; Briggs, B.J.; Nam, H.H. The Burden of RSV, hMPV, and PIV amongst Hospitalized Adults in the United States from 2016 to 2019. J. Hosp. Med. 2024, 19, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Wilkinson, T.M.A. Respiratory Viral Infections in the Elderly. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2021, 15, 1753466621995050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Hoogen, B.G.; Osterhaus, D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Clinical Impact and Diagnosis of Human Metapneumovirus Infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004, 23, S25–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, G.C.; Danziger-Isakov, L. Respiratory Viral Infections in Solid Organ and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Clin. Chest Med. 2017, 38, 707–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.-Y.; Lee, H.-J.; Lee, D.-G. Infectious Complications after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Current Status and Future Perspectives in Korea. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.; Liu, Q. Diagnosis and Treatment of Viral Diseases in Recipients of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Park, S.; Lee, I.; Park, K.S.; Kwak, E.J.; Moon, K.M.; Lee, C.K.; Bae, J.-Y.; Park, M.-S.; Song, K.-J. Genome-Wide Analysis of Human Metapneumovirus Evolution. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percivalle, E.; Sarasini, A.; Visai, L.; Revello, M.G.; Gerna, G. Rapid Detection of Human Metapneumovirus Strains in Nasopharyngeal Aspirates and Shell Vial Cultures by Monoclonal Antibodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 3443–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, M.; Sugawara, K.; Takashita, E.; Muraki, Y.; Hongo, S.; Mizuta, K.; Itagaki, T.; Nishimura, H.; Matsuzaki, Y. Development and Evaluation of a Whole Virus-Based Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for the Detection of Human Metapneumovirus Antibodies in Human Sera. J. Virol. Methods 2010, 164, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Bastien, N.; Sidaway, F.; Chan, E.; Li, Y. Seroprevalence of Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV) in the Canadian Province of Saskatchewan Analyzed by a Recombinant Nucleocapsid Protein-based Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay. J. Med. Virol. 2007, 79, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gorman, C.; McHenry, E.; Coyle, P.V. Human Metapneumovirus in Adults: A Short Case Series. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2006, 25, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-F.; Chen, B.-C.; Kao, C.-L.; Kao, C.-H.; Hsieh, K.-S.; Liu, Y.-C. Human Metapneumovirus as a Causative Agent of Lower Respiratory Tract Infection in Four Patients: The First Report of Human Metapneumovirus Infection Confirmed by RNA Sequences in Taiwan. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 38, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Alizadeh, A.A.; Rouskin, S.; Merker, J.D.; Yeh, E.; Yagi, S.; Schnurr, D.; Patterson, B.K.; Ganem, D.; DeRisi, J.L. Diagnosis of a Critical Respiratory Illness Caused by Human Metapneumovirus by Use of a Pan-Virus Microarray. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2340–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Contreras, E.A.; Carrasco-González, J.A.; Linhares, D.C.L.; Corzo, C.A.; Campos-Villalobos, J.I.; Henao-Díaz, A.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; González-González, R.B.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; et al. Emergent Molecular Techniques Applied to the Detection of Porcine Viruses. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Ma, F.; Zheng, W.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, Y.; Zheng, L. Visual Detection of the Human Metapneumovirus Using Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification with Hydroxynaphthol Blue Dye. Virol. J. 2012, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Shi, L.; Zhang, M.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y. Detection of Cassava Component in Sweet Potato Noodles by Real-Time Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (Real-Time LAMP) Method. Molecules 2019, 24, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zeng, M.; Zhao, M.; Huang, L. Research Progress on the Detection Methods of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1097905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; He, T.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, Y. Epidemiology and Diagnosis Technologies of Human Metapneumovirus in China: A Mini Review. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebihara, T.; Endo, R.; Ma, X.; Ishiguro, N.; Kikuta, H. Detection of Human Metapneumovirus Antigens in Nasopharyngeal Secretions by an Immunofluorescent-Antibody Test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 1138–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhong, J.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y.; Mao, X.; Fan, H.; Zhong, Y.; Imani, S.; Zheng, S.; Li, J. Advances in the Application of CRISPR-Cas Technology in Rapid Detection of Pathogen Nucleic Acid. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1260883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lewandowski, K.; Jeffery, K.; Downs, L.O.; Foster, D.; Sanderson, N.D.; Kavanagh, J.; Vaughan, A.; Salvagno, C.; Vipond, R.; et al. Nanopore Metagenomic Sequencing to Investigate Nosocomial Transmission of Human Metapneumovirus from a Unique Genetic Group among Haematology Patients in the United Kingdom. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Mastrolia, M. Metapneumovirus Infections and Respiratory Complications. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 37, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabi, Y.M.; Fowler, R.; Hayden, F.G. Critical Care Management of Adults with Community-Acquired Severe Respiratory Viral Infection. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, A.; Wang, W.; Jaggi, P.; Dvorchik, I.; Ramilo, O.; Koranyi, K.; Mejias, A. Human Metapneumovirus Infections Are Associated with Severe Morbidity in Hospitalized Children of All Ages. Epidemiol. Infect. 2013, 141, 2213–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.E.; Bryson, M.L. Oral Ribavirin for the Treatment of Noninfluenza Respiratory Viral Infections: A Systematic Review. Ann. Pharmacother. 2015, 49, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.V.; Chen, Z.; Cseke, G.; Wright, D.W.; Keefer, C.J.; Tollefson, S.J.; Hessell, A.; Podsiad, A.; Shepherd, B.E.; Sanna, P.P.; et al. A Recombinant Human Monoclonal Antibody to Human Metapneumovirus Fusion Protein That Neutralizes Virus In Vitro and Is Effective Therapeutically In Vivo. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 8315–8324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballegeer, M.; Saelens, X. Cell-Mediated Responses to Human Metapneumovirus Infection. Viruses 2020, 12, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basta, M.N. Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in an Adult Patient with Human Metapneumovirus Infection Successfully Managed with Veno-Venous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Semin. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2024, 29, 10892532241301195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.Y.; Renaud, C.; Ficken, E.; Thomson, B.; Kuypers, J.; Englund, J.A. Respiratory Tract Infections Due to Human Metapneumovirus in Immunocompromised Children. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2014, 3, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños-Lara, M.D.R.; Harvey, L.; Mendoza, A.; Simms, D.; Chouljenko, V.N.; Wakamatsu, N.; Kousoulas, K.G.; Guerrero-Plata, A. Impact and Regulation of Lambda Interferon Response in Human Metapneumovirus Infection. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, M.; Schickli, J.H.; Tang, R.S.; Kaur, J.; Robinson, C.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Spaete, R.R.; Haller, A.A. Identification of Small-Animal and Primate Models for Evaluation of Vaccine Candidates for Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV) and Implications for hMPV Vaccine Design. J. General. Virol. 2004, 85, 1655–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cai, H.; Niewiesk, S.; Li, J. Rational Design of Human Metapneumovirus Live Attenuated Vaccine Candidates by Inhibiting Viral mRNA Cap Methyltransferase. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 11411–11429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carp, T.-N. Recent Human Metapneumovirus Outbreak in East Asia: The Time to Shift Immunological Gears Is Now. Preprints 2025, 2025010759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, L.; Rhéaume, C.; Carbonneau, J.; Lavigne, S.; Couture, C.; Hamelin, M.-È.; Boivin, G. Adjuvant Effect of the Human Metapneumovirus (HMPV) Matrix Protein in HMPV Subunit Vaccines. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).